Introduction

Some debate exists about the value of pursuing high self-esteem in general. While many take it for granted that self-esteem is a pervasive motivator for adaptive and desirable behaviour (Pyszczynski, Greenberg, Solomon, Arndt and Schimel, Reference Pyszczynski, Greenberg, Solomon, Arndt and Schimel2004), some researchers found dissociations between high levels of self-esteem and good performance in several domains of functioning (Crocker and Park, Reference Crocker and Park2004). Ellis takes this argument even further, stating that self-esteem is a myth, driving people to chase unremittingly the approval of others. He suggests that it could better be replaced by “self-acceptance” (Ellis, Reference Ellis2005). Notwithstanding these critics, high self-esteem seems to contribute to overall health and well-being (DuBois and Flay, Reference DuBois and Flay2004), the more so when self-esteem is derived from self-determined standards (Pyszczynski and Cox, Reference Pyszczynski and Cox2004). While most research on self-esteem concerns the level of (explicit) self-esteem, self-esteem encompasses many different aspects and types, such as contingent vs. non contingent, stable vs. unstable, global vs. domain specific, and explicit vs. implicit. It is not unlikely that part of the debate on the significance of self-esteem is due to different definitions used for different aspects of the concept.

Apart from those general considerations, self-esteem is an issue in clinical psychology and psychiatry. Although low self-esteem is not an emotional disorder in itself, for many patients it is the main reason for seeking therapeutic help. In several emotional disorders low self-esteem is one of the defining symptoms for fulfilling the formal criteria of the disorder. As far as axis-I diagnoses are concerned, low self-esteem is part of the clinical picture of some of the eating disorders and depression. Apart from being a formal criterion for these diagnoses, low self-esteem is considered an aetiological factor for the development of different psychiatric problems, its maintenance, and a predictor of relapse following treatment (Stice, Reference Stice2002; Wilson and Rapee, Reference Wilson and Rapee2005; Schmitz, Kugler and Rollnik, Reference Schmitz, Kugler and Rollnik2003).

While disturbances in “self” and “identity” are often seen as core issues in all personality disorders, only in three of the DSM personality disorders is reference to self-esteem an explicit part of the criteria, i.e. avoidant, borderline and narcissistic personality disorders. A diagnosis of avoidant or borderline personality disorder contributed to having low self-esteem beyond the level of self-esteem that would have been accounted for by co-morbid depression (Lynum, Wilberg and Karterud, Reference Lynum, Wilberg and Karterud2008). In borderline personality disorder low self-esteem appears to be strongly associated with shame, which is considered to be one of the core characteristics in this disorder and as being a major determinant for suicidal behaviour, self-injurious behaviour, anger and impulsivity (Rüsch et al., Reference Rüsch, Lieb, Göttler, Hermann, Schramm, Richter, Jacob, Corrigan and Bohus2007). Moreover, in a group of 542 psychiatric and non-psychiatric adolescents, low self-esteem was closely related to depression, hopelessness and suicidal tendencies (Overholser, Adams, Lehnert and Brinkman, Reference Overholser, Adams, Lehnert and Brinkman1995). In summary: low self-esteem seems to be a major concern in the aetiology, manifestation, persistence in and vulnerability for diverse axis-I and axis-II pathologies.

It is often assumed that successful treatment of the primary disorder of the patient will automatically lead to amelioration of feelings of low self-esteem. However, this is not always the case as many patients continue to report low self-esteem after successful treatment of their main disorder. In these circumstances, some clinicians suggest that low self-esteem must be tackled in its own right (Fennell and Jenkins, Reference Fennell, Jenkins, Bennett-Levy, Butler, Fennell, Hackmann, Mueller and Westbrook2004).

Possibly due to its status of not being a specific disorder in itself, only a few methods specifically aimed at treating low self-esteem in adult psychiatric patients have been described. While many consider low self-esteem to be the manifestation of fundamental difficulties in self-representation and identity that, if exaggerated and inflexible, can move a person from “a personality type” to “someone with a personality disorder” (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Freeman and Davis2004), these methods are time limited and straightforward. Fennell has developed a treatment procedure that is mainly based on well-known standard cognitive-behavioural principles (Fennell, Reference Fennell1997; McManus, Waite and Shafran, Reference McManus, Waite and Shafran2008). According to her model, experiences in life make people formulate a “bottom line” opinion about their own self-worth. When this bottom line is negative, this leads to low self-esteem. The bottom line has the status of a basic belief in cognitive theory. Based on this basic belief people develop behavioural and cognitive strategies to find their way in daily life, without being bothered too much by their perceived inadequacies. Most of these strategies have an avoidant or compensating character, which tends to make things worse in the long run by confirming the maladaptive self-evaluations. Fennell's therapy consists of four phases: 1) assessment, goal setting and psycho-education; 2) application of cognitive techniques and behavioural experiments to break into maintenance cycles; 3) re-evaluation of the conditional assumptions and “rules for living”; 4) re-evaluation of the bottom line and promoting self-acceptance. While Fennell's approach seems to have found its way into clinical practice, no trials have been performed to put the efficacy of Fennell's method to the test (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Waite and Shafran2008).

On the other hand, Tarrier's intervention for influencing low self-esteem (Tarrier, Reference Tarrier and Morrison2001) has been tested in a trial. A convenience sample of 25 psychotic patients was randomized between therapy as usual (TAU) and a combination of TAU and a specifically developed intervention to enhance self-esteem. At termination of the intervention and 3 months later at follow-up, the specific intervention had increased self-esteem, decreased psychotic functioning, and improved social functioning (Hall and Tarrier, Reference Hall and Tarrier2003). The method is aimed at increasing the patient's awareness of positive characteristics. In Tarrier's intervention, first, positive qualities of the patient are sampled and specific instances of these qualities are indicated. The patient then needs to rehearse these instances by verbal descriptions or mental imagery. Next, the patient monitors positive behaviours in daily life that are indicative for the identified qualities. This monitoring stimulates an increase in the actual performance of these activities. During treatment, patients repeatedly re-rate their belief that they really possess these positive attributes (Tarrier, Reference Tarrier and Morrison2001).

Independent from and unaware of Tarrier's method, another (albeit in several aspects rather similar) intervention for enhancing self-esteem has been developed and put to the test (Korrelboom, Reference Korrelboom2000). In this approach, named Competitive Memory Training (COMET) for low self-esteem, patients are trained to make memories of actual occurrences of positive and worthwhile characteristics better retrievable from long-term memory. The method is a practical elaboration of Brewin's suggestion that each concept has several meaning representations attached to it in long-term memory and that a competition exists between these different meaning representations to be retrieved. In psychopathology, dysfunctional representations too often win this retrieval competition. Psychological interventions should influence this competition in such a way that functional representations more often win (Brewin, Reference Brewin2006).

COMET is considered to be one such intervention. It is set-up as a training program and consists of four phases encompassing 6–10 treatment sessions. First, the dysfunctional self-opinion is identified. Second, actual instances (behaviours, characteristics, experiences) that contradict this negative self-opinion are sampled. Third, these counter-examples are made better retrievable from long-term memory by making them more emotionally salient and by retrieving them frequently. Emotional salience is enhanced by focusing attention on the positive characteristics by writing them down in short, self-referent stories, by imagining them, and by supporting these images with a congruent body posture, facial expression, positive self-verbalization and music that is identified by the patient with positive mood and feelings of personal strength. The last phase of COMET is concerned with association. Based on the principles of counter-conditioning, patients have to imagine difficult situations that function in daily life as cues that trigger self-deprecating feelings and cognitions. While imaging these triggers, patients have to activate their positive feeling-state with posture, facial expression, positive self-verbalization, and music. These phases, as well as the other phases in COMET, are repeated regularly during sessions and in homework assignments, while their progress is monitored on a daily basis. The COMET method for treating low self-esteem appeared to be effective in a baseline-controlled study with hospitalized eating-disordered and personality-disordered patients (Korrelboom, van der Weele, Gjaltema and Hoogstraten, Reference Korrelboom, van der Weele, Gjaltema and Hoogstraten2009) and in a randomized clinical trial (RCT) with eating-disordered patients (Korrelboom, de Jong, Huijbrechts and Daansen, Reference Korrelboom, de Jong, Huijbrechts and Daansen2009). The same COMET protocol is applied in either a group or an individual setting.

Being cognitive-behavioural interventions, the three methods described above have much in common. Looking at differences, Fennell's method seems to be the most traditionally cognitive, featuring Socratic dialogue and behavioural experiments as its main therapeutic tools. Tarrier's method, while focusing on cognitions about self-worth, seems to have a more behavioural approach by stimulating patients to practise those behaviours from which they extract positive self-esteem. COMET seems to place most emphasis on experiencing positive self-feelings. Both COMET and Tarrier's interventions are mainly practised as additions to ongoing regular treatment for the main disorder for which the patient seeks help, whereas Fennell's is also practised as a stand-alone treatment. By emphasizing positive personal experiences and characteristics, all three methods share similarities with therapeutic approaches such as Gilbert's Compassionate Mind Training (Gilbert, Baldwin, Irons, Baccus and Palmer, Reference Gilbert, Baldwin, Irons, Baccus and Palmer2006) and Padesky's Building Resilience (Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley, Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009, chapter 4).

Below, first the practical application of COMET for low self-esteem is illustrated by an individual case example. Then we describe an RCT of this procedure applied in groups of personality-disordered patients.

Case example

ConnyFootnote 1 was a 40-year-old professional dog trainer referred for anxiety problems. Conny met the criteria for avoidant personality disorder. She was extremely discontented about herself and experienced low self-esteem almost continuously. Being dissatisfied with her social behaviour (“boring and clumsy”) and her intelligence (“dumb”) she was primarily ashamed of her body. She had conspicuous scars on her face and her legs due to a car accident as a child, and she thought her breasts were too small and too flabby. In her youth Conny was shy and withdrawn; later, she turned to alcohol abuse to cope with her insecurities. Still later she fled into a more socially active style of coping by constantly making unpleasant jokes about herself. However, she always avoided (in a more passive fashion) situations in which it would be impossible for her to completely conceal her appearance, such as sports and going to the beach or the swimming pool. Apart from a short period in her early twenties, Conny has never had an intimate relationship. Asked to describe the way she felt about herself, Conny stated that she found herself “unacceptable”. When the therapist asked her whether she was really totally convinced that she was “a 100 percent unacceptable person”, she replied that she “knew with her brains” that she wasn't, but that she “felt in her heart” that she was. Then the therapist asked how she “knew by her brains” that she was not totally unacceptable. Conny related that she knew from television and newspapers that some people in the world were “really bad and unacceptable”. Moreover, she could mention several positive characteristics of herself as a person. She was good with animals, accurate in her work, and helpful and loyal to her family and the few friends she had. The rationale of the treatment was explained to her: i.e. “People with low self-esteem are inclined to focus on those characteristics they consider negative, whilst ignoring the positive aspects of themselves that really do exist. COMET is aimed at restoring a more fair balance between accessing positive and negative self-opinions, by making the accessibility of positive opinions more competitive”.

Taking “being unacceptable” as a starting point of the COMET treatment, Conny and the therapist identified characteristics that contradicted this opinion. As a homework assignment, Conny was asked to monitor and write down as many actual examples of these positive characteristics she could think of. In the next session Conny was to elaborate on these examples by writing short self-referent stories about them. The most convincing of these stories were used in the next few sessions and homework assignments to make these instances more vivid and better (emotionally) recognizable. Imagery, facial expression and self-verbalization were put into action to “make the patient feel what she already knew” i.e. that she is “an acceptable person”. Among Conny's most convincing examples of being “acceptable” and “worthwhile” was an instance where she successfully completed the training of a very difficult dog that would have been slaughtered because of bad behaviour had the dog training failed. Conny wrote this story down, focusing on the gratitude of the dog owner, the radical behaviour change of the dog and, most of all, on her own feelings of pride in her achievement. Later, she had to imagine these scenes repeatedly, taking a self-assured posture and assuming a confident facial expression, meanwhile saying to herself that “taking everything together” she is an “acceptable and worthwhile person” and that “it's not only appearance that counts”. During imaging she played Aretha Franklin's I will survive. Meanwhile other examples of being an acceptable and worthwhile person were identified and practised in the same fashion. Finally, as a last step in COMET, she activated her feelings of positive self-esteem again by imaging, posture, facial expression, self-verbalization and music. Thereafter she replaced the positive “dog training” and other images by problematic images of situations in which she normally felt insecure, while keeping her positive feelings active with the remainder of the positive ingredients: posture, facial expression, self-verbalization and music. She repeated this again and again until she was able to imagine herself in these difficult scenes feeling self-confident and acceptable as a person. After COMET (which lasted 9 sessions) Conny reported that she accepted herself as she was and that her feelings of social anxiety and depression had diminished.

A randomized effectiveness study of COMET for low self-esteem for a convenience sample of patients with personality disorders

After some isolated positive experiences (e.g. as with Conny) in regular clinical practice, COMET for low self-esteem was put to the test in more sophisticated ways. Until now COMET for low self-esteem has proven successful in a baseline-controlled study with hospitalized eating and personality-disordered patients (Korrelboom, van der Weele et al., Reference Korrelboom, van der Weele, Gjaltema and Hoogstraten2009) and in an RCT with eating-disordered outpatients (Korrelboom, de Jong, et al., Reference Korrelboom, de Jong, Huijbrechts and Daansen2009). At the same time, COMET's possible effectiveness was put to the test in an RCT with a convenience sample of personality-disordered patients in a routine treatment setting. This latter study is described in more detail below.

Method

Overview of the study

The study was performed at the Program for Personality Disorders (PPD) of PsyQ, Haaglanden. The PPD is part of the Parnassia-Bavo Psychiatric Centre (PBPC), one of the largest mental health organizations in the Netherlands. The PPD specializes in the treatment of personality-disordered patients with cluster C pathologies and borderline personality disorder (BPD). The PPD distinguishes three lines in which its treatments are organized: the “Cluster C line”, the “BPD line” and the “miscellaneous line”, in which most patients with mixed personality disorders and personality disorders not otherwise specified (PDNOS), as well as some incidental patients with other cluster B of cluster A personality disorders, are treated. Most cluster A and anti-social patients of the PBPC are treated in other departments than the PPD. However, these three lines of treatment are not rigidly separated and patients of different lines often share common treatment modules during some periods of their treatment. As part of their total treatment program, the PPD organizes specific treatment modules aimed at different aspects of personality problems in which patients from the department itself (as well as from other departments of the PBPC) can participate.

The COMET group treatment for patients with personality problems and low self-esteem is among these specific treatment modules. Patients who are considered by their regular therapists to have such personality problems (as manifested by “enduring, pervasive, stable and inflexible patterns of inner experiences and behaviour that deviate markedly from expectations of the individual's culture and that lead to distress and impairment”) in combination with low self-esteem (as manifested by enduring feelings of being “inferior”, “worthless”, “ugly”, or “stupid”, or by considering themselves to be “failures”) can be referred to these COMET groups. In addition to these criteria, patients should be able to identify at least one positive personal characteristic. Exclusion criteria are suicidal risk and not being able or willing to participate in group treatment, as judged by the COMET assessors. Being an effectiveness study, the current study was conducted in the midst of a “working outpatient psychiatric department”. Between October 2005 and October 2007 all regular referrals for COMET were more thoroughly screened by the COMET team to assess whether they complied with the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the current study.

All patients who fulfilled these criteria and gave informed consent were randomized into one of two treatment conditions. The experimental group received 7 weekly sessions of COMET in groups during their (ongoing) regular therapy as usual (COMET + TAU), while the control group received 7 weeks of (ongoing) regular therapy as usual (TAU) only. After 7 weeks of TAU the control group then received 7 weeks of COMET. All patients who completed COMET (whether in the experimental group or later in the control group) were approached 7–10 weeks after completion of their COMET to assess the stability of the COMET effects over time.

Patients

To be eligible, referred patients had to: 1) fulfil the criteria of the DSM-IV-TR (4th ed., text rev.; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) for having a personality disorder as the main diagnosis; 2) low self-esteem had to be manifested in a score ≤28 on the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1965); 3) patients had to fulfil the customary COMET criteria of being able to indicate at least one positive personal characteristic (e.g. “being honest”, or “being a faithful friend”); and 4) be able and willing to participate in a group treatment. Contra-indications for participation were suicidal risk and not being able to complete the measurements. A DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of a personality disorder was established by comparing (in a non-standardized clinical interview) the presenting problems of the patients and the information given by the referring therapists with the formal DSM criteria for personality disorders. The cut-off score of 28 on the RSES as an inclusion criterion to objectify reported low self-esteem was based on a large survey where this score was found to be 1 standard deviation (SD) below the mean of a functional Dutch population (Schmitt and Allik, Reference Schmitt and Allik2005). All other inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on the clinical judgement of the COMET assessor. Patients who were eligible had to give informed consent.

In previous studies on COMET for low self-esteem, large within-effects sizes (Olij et al., Reference Olij, Korrelboom, Huijbrechts, Jong, Cloin, Maarsingh and Paumen2006, Korrelboom, van der Weele et al., Reference Korrelboom, van der Weele, Gjaltema and Hoogstraten2009) and intermediate to large between-effects sizes on several measures of self-esteem were found (Korrelboom, de Jong et al., Reference Korrelboom, de Jong, Huijbrechts and Daansen2009). Therefore, allowing for dropout, a minimum of 90 patients was considered sufficient to demonstrate differences between groups, as long as similar differences also existed in this group of personality-disordered patients.

A total of 119 patients were screened. Of these patients, 28 did not fulfil the criteria for participation (24 did not have a formal personality disorder, and 4 scored above the cut-off score of 28 on the RSES). Thus, of the 91 patients enrolled in the study, 48 were randomized to COMET + TAU (experimental group) and 43 to TAU alone (control group). In the COMET group 45 patients started treatment while only 31 did so in the control group. After randomization, a total of 15 patients (3 in the experimental group and 12 in the control group) ended their participation, whether or not with formal withdrawal of informed consent, implying that they did not submit their pre-treatment measurements or did not participate at all in the treatments under study. Finally, 76 patients entered the study (45 in the experimental group and 31 in the control group). All further calculations and analyses pertain to these 76 patients.

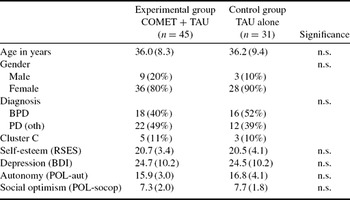

Of those 76 patients, 12 (16%) were male and 64 (84%) female. Mean age was 36.1 (SD = 8.7) years, 34 patients (45%) were diagnosed with a borderline personality disorder and another 34 patients (45%) with “another” personality disorder (“mixed” or “personality disorder NOS”). Finally, 8 patients (10%) were considered to have a cluster C personality disorder. Figure 1 and Table 1 present the results of the inclusion and randomization procedures.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study

Table 1. Pre-treatment status for the two treatment groups

COMET = Competitive Memory Training (experimental group),

TAU = Therapy as usual (control group),

n.s. = not significant,

BPD = Borderline Personality Disorder,

PD (oth) = Other personality disorder,

Cluster C = Cluster C personality disorder,

RSES = Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale,

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory,

POL-aut = Positive Outcome List, autonomy,

POL-socop = Positive Outcome List, social optimism.

Instruments

During the study, all patients were assessed several times. The first measurements were taken within 2 weeks prior to the start of COMET + TAU for the experimental group and within 2 weeks prior to the start of the “waiting for COMET period” for the control group (pre-treatment measurements). The second measurements were taken 7 weeks later at the end of COMET + TAU (experimental group), which was at the same time as the end of the “waiting for COMET period” for the control group (post-treatment measurement). Since COMET for the control group started immediately after their waiting period, this second measurement was at the same time the pre-COMET measurement for the control group. The control group was then assessed after they had finished their COMET (post-COMET measurement for the control group). Finally, all patients who had completed COMET (whether in the experimental group or later in the control group) were approached 7–10 weeks after the completion of COMET to fill in measurements again to assess the stability of COMET effects over a longer time period (follow-up). Thus, the experimental group was assessed three times (start of COMET, end of COMET, and follow-up), while the control group was assessed four times (start of waiting period, end of waiting period/start of COMET, end of COMET, and follow-up). The following measures were assessed at all specified moments:

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1965). On a Dutch version of this 10-item scale, items have to be answered on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (4). Half of the items are positively formulated, the other half negatively. After recoding, a high total score (range 10–40) means higher self-esteem. The RSES assesses “global self-esteem” and is sufficiently reliable and valid (Blascovich and Tomaka, Reference Blascovich, Tomaka, Robinson, Shaver and Wrightsman1991). The RSES was considered the primary outcome measure.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI: Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh, Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh1961). A Dutch translation of this 21-item self-referent 4-point Likert scale has proven to be reliable (Bouman, Luteijn, Albersnagel and van der Ploeg Reference Bouman, Luteijn, Albersnagel and Ploeg1985) and valid (Bouman, Reference Bouman, Albersnagel, Emmelkamp and van den Hoofdakker1989). Low scores are favourable. The BDI (range 0–63) was considered a secondary outcome measure.

Positive Outcome Scale (POS; Positieve Uitkomsten Lijst or PUL: Appelo, Reference Appelo2005). This 10-item Dutch self-report instrument assesses resilience. Seven items pertain to autonomy (range 7–28) and three to social optimism (range 3–12). Scores on the POS are strongly associated with self-efficacy. There are Dutch norms for a normal population and a psychiatric population. Reliability and validity are sufficient (Appelo, Reference Appelo2005). High scores are favourable. The POS was considered another secondary outcome measure.

Therapists

A total of 9 therapists participated in the study: 5 clinical psychologists and 4 nurses. All had ample experience in treating patients with personality disorders in groups. In addition, all were trained and supervised in COMET by the first author (KK). Each COMET group was led by two therapists. In all instances, at least one of these therapists was a clinical psychologist and at least one had more than 2 years experience in treating patients with personality disorders.

Procedure

COMET was carried out in small groups (5–9 patients) as an additional treatment to the ongoing regular treatment program (TAU). After referral to COMET by their therapists, patients were interviewed by one of the COMET therapists. After inclusion and informed consent, patients were randomized over the two research conditions. Randomization was performed in separate blocks of 10–18 patients, by opening blinded envelopes in which both treatment conditions were concealed in advance. Pre-treatment measurements were made at most 2 weeks prior to the start of the treatments (COMET + TAU or TAU alone). When intake took place later, patients filled in their pre-treatment measurements during intake. When the period between intake and start of treatments was longer than 2 weeks, they took the measurements home and filled them in later. Second measurements of all patients were taken immediately after the experimental group had finished COMET, which was 7 weeks later. Patients in the control group received COMET as soon as the experimental groups had finished. Around the same time as these control patients were assessed for their post-treatment results, patients from the experimental groups who had completed COMET were assessed for the third time for their follow-up results. Another 7–10 weeks later, COMET completers from the control group were approached to fill in their fourth and last measurements, i.e. the follow-up.

Treatments

COMET was performed according to a manual that all patients received at the start of the training. COMET lasted 7 sessions of 2 hours each and consisted of the following steps:

Identifying the negative self-image. The patient describes what she thinks is negative about herself (session 1).

Identifying a credible positive self-image that is incompatible with the negative self-image. The patient is asked whether she really believes this negative image of herself is totally true and, if not, which personal characteristics and experiences contradict the negative self-image (session 1).

Strengthening the positive self-image. Then, the competitiveness in the retrieval competition of the contradictory positive self-image is enhanced by repeatedly strengthening its emotional load. This is realized by: a) writing small self-referent stories of instances in which the positive qualities were manifest, and distilling positive self-statements of these instances (session 2 and 3); b) imagining oneself in these positive personalized scenes (session 3); c) the purposeful manipulation of body posture and facial expression (session 4); and d) listening to music chosen by each patient because it is felt to be congruent with a positive self-image (session 5). These exercises are to be practised during sessions 2–5 as well as during daily homework assignments.

Forming new associations between “risk cues” and positive self-image by counter-conditioning. In the last sessions of COMET, patients are trained to associate their new positive self-image with cues that normally provoke uncertainty. Positive self-esteem has to be activated with the aid of imagination, posture, facial expression, music and positive self-statements. Then, the positive image is replaced by the image of a situation in which she normally feels negative about herself. Now, however, by keeping her positive feeling state activated she tries to feel self-confident while “being in the imagined difficult scene”. Again, this has to be repeated several times and also practised in daily homework assignments. Once a difficult scene can be tolerated while retaining positive self-esteem, other scenes are practised (session 6 and 7).

TAU (treatment as usual) cannot be specified in a detailed manner since included patients had different psychopathologies, while some of them had their regular treatment in different teams of the PPD or in different departments of the PBPC. In general, patients in the PPD and the PBPC are treated on an outpatient basis, with treatment methods that can be considered evidence-based or, at least, consensus-based.

Statistical analyses

First, possible pre-treatment differences between completers and dropouts, between both groups in general, as well as between completers in both groups were tested with regression analyses, taking age, gender, diagnosis and pre-treatment scores on all outcome variables as predictors. Then, when no pre-treatment differences between completers and dropouts or randomization status could be identified, missing data were imputed with the Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm of SPSS 17. This imputation procedure was checked by comparing both groups again, this time with inclusion of the imputed data.

Thereafter, differences at post-treatment between the two groups were tested for the main outcome variable (self-esteem) with an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with the post-treatment score as dependent variable, the pre-treatment score as the covariate, and the treatment allocation as a fixed factor. Then, to control for inflated type 1 error, possible differences at both POS subscales and the BDI were tested in a MANOVA, with the baseline data as covariates. When this MANCOVA yielded a significant result, a step-down was made using separate ANCOVAs of the post-treatment data with the pre-treatment data as covariates and treatment allocation as the fixed factor. Except for the regression analyses where a p-value of 0.1 was applied, a p-value of 0.05 was considered significant in all other tests.

To give an impression of the meaning and sizes of these differences, Cohen's d based on the mean squared error and the sizes of both the experimental and the control group (Thalheimer and Cook, Reference Thalheimer and Cook2002), as well as 95% confidence intervals, and estimates of clinical significance change (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) of those patients who completed COMET were calculated.

Finally, to assess the stability of the effects of COMET, the results of all COMET completers who also filled in follow-up measurements were analyzed with ANOVA repeated measures on the main outcome measure and with MANOVA repeated measures on the three other outcome measures, defining three moments for time (pre-COMET, post-COMET, and follow-up).

Results

Of the 76 patients included in the study, 19 (25%) dropped out during the first study period (COMET + TAU versus TAU): 11 in the experimental group (24%) and 8 (26%) in the control group. No predictors for dropout in general could be identified. Also, no differences in pre-treatment status were detected concerning allocation to treatment condition or between the completers in both treatment conditions. Thus, missing values could be considered as a random collection of the research data. To be able to report the results on an intention-to-treat basis, all missing scores at post-treatment were imputed by use of the SPSS 17 EM algorithm by taking all available pre- and post-treatment outcome measures as well as age, diagnosis, gender and treatment condition as predictors. After imputation, still no predictors were found for allocation to one of the treatment conditions, indicating that randomization was still successful.

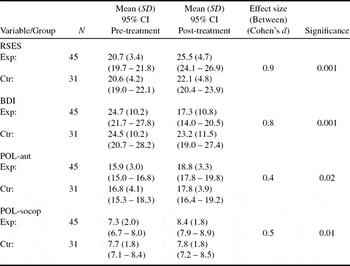

On an intention-to-treat basis, patients in the COMET+TAU condition performed better on all outcome measures post-treatment. Table 2 gives an overview of the main results. There was a significant interaction effect (treatment x time) on the ANCOVA for self-esteem (RSES: F (2, 73) = 12.54, p = .001). On the combined scores of depression (BDI), autonomy (POL-aut), and social optimism (POL-socop), MANCOVA showed better effects for COMET + TAU than for TAU alone: F (3, 69) = 6.15, p < .000. A step-down showed that COMET + TAU was better than TAU alone on all three separate variables (BDI: F (1, 71) = 11.29, p = .001; POL-aut: F (1, 71) = 6.15, p = .02; POL-socop: F (1,71) = 6.75, p = .01). The size of these differences between COMET and control were large on self-esteem and depression, intermediate on social optimism, and small on autonomy.

Table 2. Interaction effects between pre- and post-treatment: intention-to-treat

95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval,

RSES = Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale,

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory,

POL-aut = Positive Outcome List, autonomy,

POL-socop = Positive Outcome List, social optimism,

Exp = experimental group (COMET + TAU),

Ctr = control group (TAU alone).

Within-effect sizes from pre- to post-test for the COMET group were large on two variables [1.2 (RSES) and 0.9 (POL-aut)] and intermediate on the other two [0.7 (BDI) and 0.6 (POL-socop)]. For the control group there were two small within-effect sizes [0.4 (RSES) and 0.3 on the POL-aut].

To assess the clinical significance of the changes on the RSES (the primary outcome variable) that completers realized during COMET + TAU and TAU alone, the procedure described by Jacobson and Truax (Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) was adopted. According to this procedure a patient has to fulfil two criteria to make a clinically significant change: a) he/she should progress from the problematic population to a normally functioning population, and b) he/she should realize a “reliable change score”, i.e. the difference between his/her pre-treatment and post-treatment score should surpass the standard error of difference between these two scores. As a cut-off point between problematic and normal functioning, a score of 28 on the RSES was chosen, which was one of the inclusion criteria in the present study. A post-treatment score of 28 or above on this scale would bring the patient within the range of 1 SD under the mean of a functional Dutch group (Schmitt and Allik, Reference Schmitt and Allik2005) and thus was considered indicative of normal functioning on self-esteem. Based on the reliability index of the RSES of 0.87, found in that same study, an increase of at least 6 points between pre- and post-measurement on this scale was considered necessary to fulfil Jacobson and Truax' second requirement. According to these criteria 12 patients that completed COMET + TAU (35% of the COMET + TAU completers) progressed from the problematic to the functional population, while 2 patients did so in TAU alone (9% of the TAU alone completers). In COMET + TAU 13 patients (38% of the completers) realized a reliable change by progressing 6 points or more between pre- and post-treatment measures on the RSES, while 3 patients in TAU alone did so (13% of the completers). Finally, 8 patients in COMET + TAU fulfilled both Jacobson and Truax criteria and made a clinically significant change during treatment (24%), while only 1 patient in the TAU alone condition reached this point (4%).

To get an impression of the possible influence of the imputation procedure on outcome, we finally calculated tests of significance for those patients that completed both treatments. In these analyses separate ANCOVAs on all outcome measures also yielded significant differences in favour of COMET, with roughly the same p- values: RSES: F (2, 54) = 11.87, p = .001; BDI: F (2, 54) = 12.74, p = .001; POL-aut: F (2, 54) = 6.25, p = .015; POL-socop: F (2, 54) = 10.28, p = .002. These outcomes seem to justify the application of our imputation method.

Stability of COMET effects over time

After their waiting period, patients in the control condition also received COMET. Of these patients 23 started COMET, and 20 of them completed the treatment. In general, these patients improved during COMET on three of the outcome measures as was shown by paired t-tests; RSES: t (18) = −2.4, p = .03; BDI: t (19) = 3.30, p = .004; POL-aut: t (19) = −1.54, p = .14 (n.s.); POL-socop: t (19) = 0.009. Cohen's d for the three significant changes were intermediate: 0.6 on all three variables.

All patients who had completed COMET (from both the experimental and control condition) were then approached 7–10 weeks after the completion of COMET to assess the stability of the COMET effects over a longer time period. Of the 76 patients who started treatment and were analyzed in the current study, 54 completed COMET. Of these, 30 returned follow-up measurements; they were not markedly different from the 76 patients who started the study, i.e. 17% male, 83% female; mean age 37.2 (SD = 8.4) years; 53% BPS, 43% other PD and 3% cluster C; pre-COMET measures on the RSES: 20.8 (SD = 4.2), on the BDI: 24.9 (SD = 11.6), on the POL-aut: 16.6 (SD = 3.6) and on the POL-socop: 7.3 (SD = 1.6). In 4 separate ANOVAs for repeated measures (with three moments for time: start of COMET, end of COMET and follow-up) effects remained stable on 3 of the 4 outcome measures; RSES: F (2, 56) = 14.10, p < .000Footnote 2; BDI: F (2, 58) = 24.53, p < .000; POL-aut: F (2, 58), p = .003. As indicated by contrasts, in all instances these significant changes were realized during pre-COMET to post-COMET, while there were no significant changes between post-COMET and follow-up of COMET. These findings suggest that patients changed on the specified measurements during COMET and that these changes remained stable, at least during the following few months. This was different for POL-socop. On this measure the ANOVA for repeated measures was also significant (F (2, 56) = 45.93, p = .003), but this time contrasts showed that changes were significant in both time periods: from pre-COMET to post-COMET and between post-COMET and follow-up. While the change at POL-socop during COMET was positive (patients got better), the change at follow-up was negative, indicating that patients had deteriorated again on this outcome measure. Figures 2–5 give an impression of the follow-up results.

Figure 2. RSES follow-up

Figure 3. BDI follow-up

Figure 4. POL-aut follow-up

Figure 5. POL-socop follow-up

Discussion

Since low self-esteem is a major problem in the manifestation of different emotional disorders (including personality disorders), as well as a risk factor for the development of and relapse into some of these disorders, and since low self-esteem is not always automatically enhanced by the successful treatment of the main presenting disorder, it is important to have adequate specific treatment methods for this condition. COMET for low self-esteem might be such a treatment. As the first randomized study into COMET for low self-esteem as a treatment procedure for patients with personality disorders and low self-esteem, the current study confirms earlier findings on its efficacy as an add-on to regular therapy (Korrelboom, van der Weele et al., Reference Korrelboom, van der Weele, Gjaltema and Hoogstraten2009; Korrelboom, de Jong et al., Reference Korrelboom, de Jong, Huijbrechts and Daansen2009). Also in this specific group of personality-disordered patients, COMET seems to enhance self-esteem (at least in combination with regular therapy) and reduce depression, both with large effect sizes. Different from the COMET study on eating-disordered patients (Korrelboom, de Jong et al., Reference Korrelboom, de Jong, Huijbrechts and Daansen2009), in the current study a differential effect with small and intermediate effect sizes on autonomy and social optimism, both related to self-efficacy, in favour of COMET was also found. All these changes were realized in a short period of time with patients generally considered difficult to treat and many of whom had been in therapy for extended periods of time. Moreover, most effects seem to be stable over a certain period of time. Only on social optimism, patients relapsed after termination of COMET within 7–10 weeks.

Notwithstanding these positive results, it should be noted that the mean post-treatment score on the RSES was still below 1 SD of the functional population. The impact of COMET might be enhanced by prolonging the treatment period. Another way to further promote effectiveness might be the explicit addition of more behavioural elements (as in Tarrier's approach to low self-esteem) to the core experiential aspects of COMET.

Apart from the large advantage of a high ecological validity, research such as the present study (performed amidst the daily hassles of routine psychiatric practice) has several limitations. Diagnoses of personality disorder and low self-esteem were based on informal clinical interviews and self-report, respectively. Moreover, there was no check on the amount and content of the regular treatment that patients in both conditions received, and treatment integrity was not formally checked. While the randomization procedure was successful in creating two groups of patients who were statistically similar, a large proportion of patients in the control condition (28%) did not show up and/or withdrew consent and had to be excluded from all calculations/analyses, and during the study the dropout percentages were relatively high. However, in our opinion, no show and dropout percentages should be attributed to the clinical setting and not to the treatment procedure under study. Moreover, dropout of 20–30% does not seem to be uncommon in studies in regular psychiatric settings (Westbrook and Kirk, Reference Westbrook and Kirk2005; Kampman, Keijsers, Hoogduin and Hendriks, Reference Kampman, Keijsers, Hoogduin and Hendriks2008; Bados, Balaguer and Saldana, Reference Bados, Balaguer and Saldana2007). Another limitation pertains to the durability and stability of the changes in self-esteem, depression and autonomy. In the current study treatment results of a sub-sample (39%) of COMET completers who returned the follow-up measurements appeared to remain stable on the primary outcome measure and on 2 of the 3 secondary outcome measures during a period of 7–10 weeks. This is more or less similar to results found in another COMET study for low self-esteem with personality-disordered and eating-disordered patients (Korrelboom, van der Weele et al., Reference Korrelboom, van der Weele, Gjaltema and Hoogstraten2009). However, assessment of longer follow-up periods is necessary to evaluate COMET as a worthwhile treatment method for low self-esteem. Moreover, while the sub-sample of follow-up patients seems to be representative for the whole sample, it would of course been preferable to have assessed a larger proportion of the sample at follow-up.

Apart from these limitations, self-esteem is a comprehensive and relatively ill-defined concept involving several aspects and types of self-esteem, a situation that can complicate the interpretation of findings. For instance, during treatment, the formal distinction between self-esteem and self-acceptance might easily have disappeared. Since self-acceptance was not measured whereas self-esteem was, it is not possible to ascertain whether self-acceptance also changed during treatment. In light of the critical comments made by Ellis (Reference Ellis2005) and Crocker and Park (Reference Crocker and Park2004) concerning the value of the concept of self-esteem, it is recommended that future studies formally assess self-acceptance. Finally, some discrepancy exists between explicit and implicit self-esteem. Some believe that implicit self-esteem might be more important to psychopathology than explicit self-esteem (De Raedt, Schacht, Franck and De Houwer, Reference De Raedt, Schacht, Franck and De Houwer2006). Although in the current study implicit self-esteem was not assessed, it seems worthwhile to do so in future trials that aim to enhance low self-esteem.

Thus, while the results of the current study suggest that the level of explicit self-esteem can be influenced by a short and relatively straightforward intervention, the significance of these findings for the stability and generality of self-esteem, the quality of life and the prevention of relapse need to be further demonstrated.

Conclusion

COMET for low self-esteem seems to be an efficacious trans-diagnostic approach that is relatively easy to implement in the treatment of several psychopathological disorders. However, its potential value should be further assessed under more rigidly controlled conditions, in comparison with other specific treatment procedures for low self-esteem, and with longer follow-up periods. Moreover, apart from explicit measures of self-esteem, the inclusion of measurements of implicit self-esteem, stability of self-esteem, domain-specificity of self-esteem and a measure of self-acceptance should be a part of future studies. Finally, it should be investigated whether the explicit addition of behavioural elements and/or extending the length of COMET can further enhance its efficacy.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.