Michel Ragon (Reference Ragon and Ragon1981, 38) wrote: ‘Mais en réalité une tombe, même la plus modeste, est toujours une architecture’ [But in reality, a tomb, even the most modest, is still architecture]. Indeed, all graves are a form of architecture. The very fact of digging them implies an intention to arrange a space to receive the remains of the deceased. This involves thinking about the shape and dimensions of the sepulchral pit and the methods and materials used for its internal and external architecture.

This paper considers the architecture of formal graves from the La Tène period in north-western Gaul (c. 450–25 bc) and the Early to latest Iron Age in southern Britain (c. 450 bc–ad 43/50). The shapes of burial pits are considered in relation to the treatments of bodies that they contain, and the different types of internal and external funerary architecture are categorised by the materials used for their construction. Burials without any perennial structures are also mentioned. The features highlighted in this paper enable the identification of geographical groups by their recurrent choices in grave architecture.

A previous study of formal burials allowed for the identification of regional groups and local funerary traditions within the study area (Vannier Reference Vannier2019). This research contributed to the definition of funerary practices of communities on both sides of the English Channel within the ‘mid-Atlantic province’ (Milcent Reference Milcent2012, 11). It also helped distinguish them from the groups located in the eastern margins of the zone considered, which are well-documented and belong to a transitional area between the cross-Channel and Continental cultural complexes (Verger Reference Verger and Buchsenschutz2015, 173). The research presented here compares the study of funerary architectural elements over time and space to the regional groups previously identified through the wider analyses of funerary data. This study also makes it possible to test whether or not certain areas that are differentiated by a predominant body treatment had common burial architecture.

‘The West’ is somewhat devalued in the archaeological research of continental European prehistory (Milcent Reference Milcent2012, 17). Research on the Mediterranean and north Alpine regions has been, and still is, more extensive. This devaluation of north-west Europe is the result of ‘invasionist’ and ‘diffusionist’ theories (Chapman & Hamerow Reference Chapman and Hamerow1977). These hypotheses suggest a succession of population movements and diffusion of objects, materials, and technological knowledge mainly along east–west and south–north axes, from the continent to the British Isles and from the Mediterranean northward. Therefore, research has focused on the eastern and southern regions that are considered the original sources of ideas and objects. Another factor contributing to this depreciation is a discrepancy between relative chronological systems established for the western continental regions and the British Isles based on these ‘diffusionist’ ideas, which includes a time gap between them. Thus, the different continental and insular methodologies and chronologies often hinder large-scale research on the north-west European Iron Age. In this paper, the English Channel will not be treated as a strict border; north-western Gaul and southern Britain will be studied together over five centuries. The continental study area includes the alluvial plains and valleys of the main rivers from the Gironde Estuary in the south to Flanders in the north. The study area in southern Britain is delimited by the Bristol Channel in the west and the Wash in the east (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Map illustrating the main body treatment within the different regions of the study area

BURIAL SITES

The graves included in this study were sometimes placed on former funerary sites or domestic places (Baray Reference Baray2003, 70–1). Although there is a practicality to installing a burial in a space already defined and arranged, the re-appropriation of an ancient site may also translate a desire to signify the legitimacy of territorial occupation by belonging to a lineage, group, or land (Milcent Reference Milcent1993, 21). The reuse or association with previous funerary places also ensured the visibility of their signage in the landscape, in the more or less long term, and their strategic location (isolation in the landscape, proximity to a dwelling, etc). The reuse of some enclosures may have led to the destruction of internal elements and possibly to a reorganisation of the initial structure.

A funerary site can be a collective place for commemorating the dead, where ritual gestures are practised and a banquet is shared with the deceased (Baray Reference Baray2003, 130, 270). This idea of a commemorative banquet refers to the importance of marking the burial and its individualisation, if the rites were performed in honour of a single person, but it can be assumed that they could have been held for several deceased people or even for all the deceased in a cemetery. Some structures lacking funerary remains, which seem empty at the time of their discovery, could have been places for assembly, rituals, and/or commemoration of the dead. These empty architectural elements have been discovered nearby burials pits containing human remains, for example as a pair of semi-circular ditches excavated at Brisley Farm, Kent (Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2018, 76). They may have lost their deposits for several reasons, such as erosion, ploughing, burrowing animals, etc. Some deposits on the ground may have disappeared over time, or these structures may never have had any burial or material remains. Sometimes the burials seem to be installed around an empty circular space, such as at Westhampnett, Sussex (Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2010, 24) or at Cizancourt-Licourt, La Sole des Galets, Somme (Lefèvre Reference Lefèvre1998, 111). One may wonder about the function of such a space and whether structures, which have now disappeared, were present during the activity phase of the site.

Without claiming to be exhaustive, the inventory of data used in this paper is the result of a literature search. The information was collected by consulting several hundred publications, such as books dedicated to the archaeology of death and funerary practices, as well as monographs, theses, journal articles, excavation reports, and rare inventories. The quantity and quality of the information are uneven both geographically and chronologically and sometimes depend on incomplete documentation. The database includes 1114 known funerary sites from five centuries: 450 bc–ad 43/50. The ‘sites’ can be either isolated graves or groups of burials (containing from one to hundreds of burials, their quantity not always indicated in the publications consulted) outside dwellings or places of worship, and sometimes they contain several occupancies on the same site, either successively or discontinuously after a period of abandonment. The body treatments observed in the burial sites studied include both inhumations and cremations, which may be exclusive or used simultaneously within the same place or the same grave.

TREATMENTS OF BODIES AND BURIAL PITS

The spatial distribution of body treatments (inhumation or cremation) reveals geographical distinctions within the study area (Fig. 1; see Table 3). The regions characterised by a preference for inhumation are located in the eastern part of the continental study area, the Caen Plain around the Orne river in Gaul, and in the western part of southern Britain: Aisne–Marne–Ardennes (5th–3rd centuries BC); northern central Gaul (5th–1st centuries bc); Caen Plain–Orne (5th–2nd centuries bc); Ⓘle-de-France (3rd century bc); Cornwall (2nd century bc–mid-1st century ad); the Cotswolds (1st century bc–mid-1st century ad); and Dorset (1st century bc–1st century ad). Three regions are characterised by cremations: Armorica (5th century bc); Belgic Gaul (3rd–1st centuries bc); and south-east England (1st century bc–mid-1st century ad). The central areas of central southern England (2nd century bc–mid-1st century ad) and western Gaul (5th–1st centuries bc), although less well documented, seem to show a preference for both inhumations and cremations.

Inhumation graves

A sample of 135 burials from the database of 1114 sites (12%) was selected based on the accuracy of the information known about the shapes and dimensions of their pits. The results show that four main shapes of inhumation pits are known: quadrangular, rectangular, or square (90; 67%); trapezoidal (30; 22%); circular or oval (14; 10%); and irregular or bean-shaped (1; 1%).

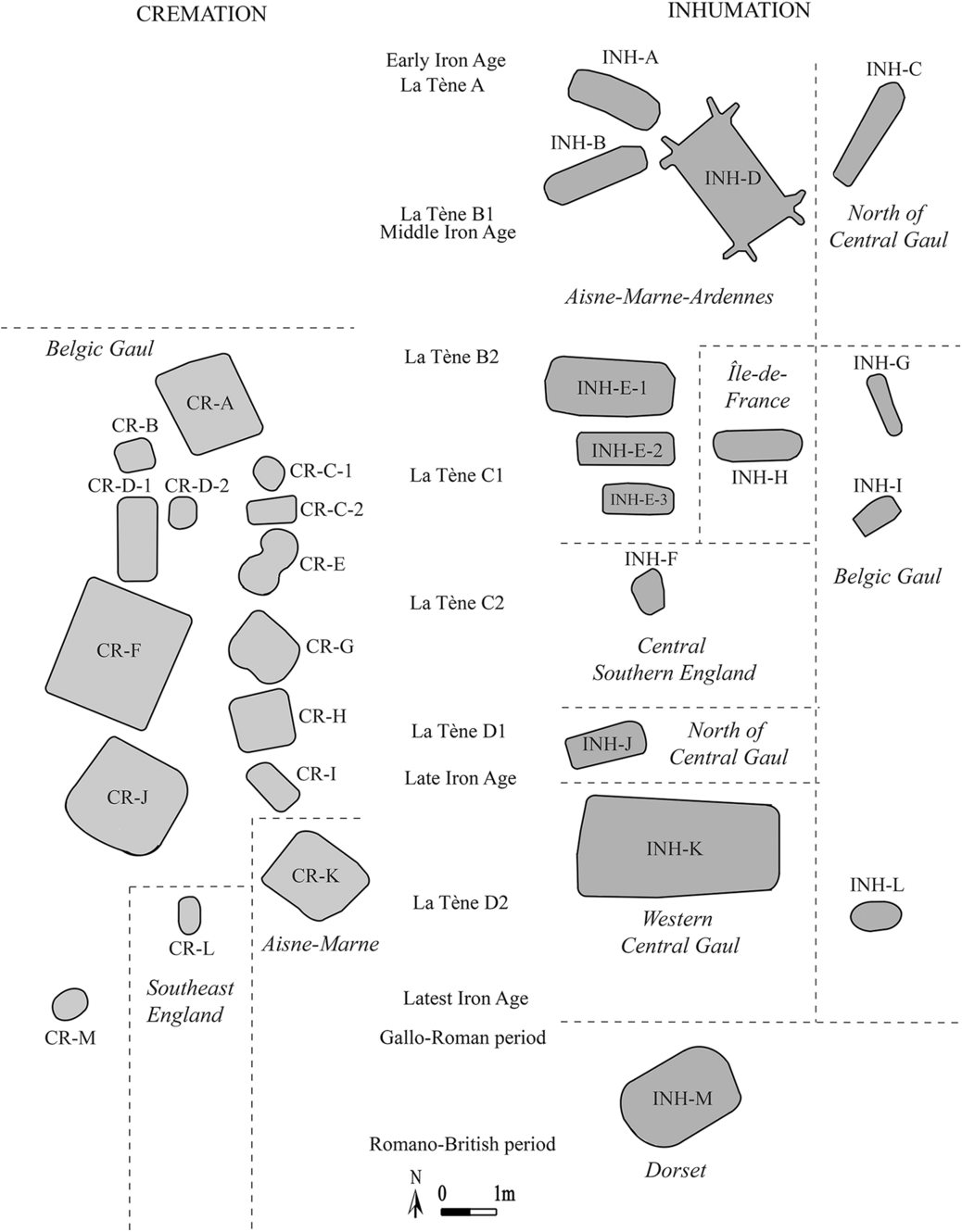

Quadrangular-shaped burial pits have a clear majority in all territories through the five centuries considered (Table 1; Fig. 2). The graves containing bodies in a folded position (contracted, crouched, or flexed) required a shorter length and are generally smaller than those containing extended bodies (supine, lateral, or prone). The shapes and dimensions of the graves were also designed to fit the internal architecture of the grave and the objects deposited with the dead (Baray Reference Baray2003, 218). Chariot burials with hollows for the two wheels are characteristic of the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes region at the beginning of the La Tène period. The presence of a wooden chamber is often indicated by notches that were dug into the corners of these burials. For example, the La Tène A isolated grave from Moncetz-Longevas, La Commune, Marne, had L-shaped notches in its corners for the installation of a ‘Blockbau’-type wooden formwork of four walls nested one inside the other (Fig. 2, INH-D; Issenmann et al. Reference Issenmann, Le Clézio, Brenot, Dubreucq and Lambot2013, 63). Trapezoidal-shaped pits are also mostly visible in the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes region and usually contain several bodies, as at Évergnicourt, Le Tournant du Chêne, Aisne (Lambot & Méniel Reference Lambot and Méniel2005, 328). This type of pit is known mostly from between the 5th and mid-3rd centuries bc. Circular or oval inhumation graves are found on both sides of the Channel but seem to be particularly characteristic of the insular sites. This is because inhumations in a folded position are more common in Britain, thus the graves were made according to the position of the bodies (Table 1; Fig. 2, INH-L). Irregular-contoured or bean-shaped inhumation pits are also documented, but they are few and mainly located in north-west Gaul and southern Britain from the 2nd century bc onwards (Fig. 2, INH-F; Lepaumier & Delrieu Reference Lepaumier and Delrieu2010, 156).

TABLE 1: MAIN SHAPES OF INHUMATION GRAVES

Fig. 2. Typologies of diverse shapes of burial pits. Redrawn and adapted by the author. CR-A: Gavrelle, Au Chemin de Bailleul, Pas-de-Calais (from Debiak et al. Reference Debiak, Gaillard, Jacques and Rossignol1998, fig. 14). CR-B: Saint-Laurent-Blangy, Les Chemins Croisés, Pas-de-Calais (from Debiak et al. Reference Debiak, Gaillard, Jacques and Rossignol1998, fig. 11). CR-C: Mory-Montcrux, Sous-Les-Vignes-d’en-Haut, Oise (from Blanchet Reference Blanchet1983, figs 5 & 7). CR-D: Saint-Riquier-en-Rivière, Au-dessus du Val d’Aulnoy, Seine-Maritime (from Mantel et al. Reference Mantel, Devillers and Dubois2002, figs 3 & 9). CR-E: La Calotterie, La Fontaine aux Linottes, Pas-de-Calais (from Blancquaert & Desfossés Reference Blancquaert and Desfossés1998, fig. 5). CR-F: Allonville, Le Coquingnard, Somme (from Ferdière et al. Reference Ferdière, Gaudefroy, Massy, Marmoz, Mohen and Poplin1973, fig. 2). CR-G: Saleux, La Vallée du Bois de Guignemicourt, Somme (from Malrain et al. Reference Malrain, Gaudefroy and Gransar2005, fig. 16). CR-H: Bois-Guillaume, Les Bocquets, Seine-Maritime (from Baray Reference Baray, Baray, Honneger and Dias-Meirinho2011, fig. 11). CR-I: Vismes-au-Val, Le Bois de Dix-Sept, Somme (from Barbet & Bayard Reference Barbet and Bayard1996, fig. 6). CR-J: Marcelcave, Le Chemin d’Ignaucourt, Somme (from Ginoux Reference Ginoux, Kruta and Leman-Delerive2007, fig. 4). CR-K: Chivy-les-Etouvelles, Aisne (from Gransar & Naze Reference Gransar and Naze1996, 25). CR-L: Westhampnett, Sussex (from Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2010, fig. 8). CR-M: Verberie, La Plaine de Saint-Germain (from Fémolant Reference Fémolant1997, fig. 4). INH-A: Sarry, Les Auges, Marne (from Bonnabel Reference Bonnabel2013, fig. 234). INH-B: Saint-Etienne-au-Temple, Champ Henry, Ardennes (from Bonnabel Reference Bonnabel2013, fig. 209). INH-C: Bromeilles, Mainville, Loiret (from Duval Reference Duval1976, fig. 16.1). INH-D: Moncetz-Longevas, La Commune, Marne (from Issenmann et al. Reference Issenmann, Le Clézio, Brenot, Dubreucq and Lambot2013, fig. 7). INH-E: Orainville, La Croyère, Aisne (from Desenne et al. Reference Desenne, Collart, Auxiette, Martin, Rapin and Duvette2005, figs 38 & 39). INH-F: Suddern Farm Hampshire (from Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2010, fig. 3). INH-G: Gavrelle, Au Chemin de Bailleul, Pas-de-Calais (from Debiak et al. Reference Debiak, Gaillard, Jacques and Rossignol1998, fig. 13). INH-H: Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, Les Varennes, Val-de-Marne (from Duval Reference Duval1976, fig. 16.3). INH-I: Attichy-Bitry, L’avenue – Proche de la Maladrerie (from Friboulet Reference Friboulet2009, 61). INH-J: Esvres-sur-Indre, Vaugrignon, Indre-et-Loire (from Riquier Reference Riquier2004, fig. 4). INH-K: Saint-Georges-lès-Baillargeaux, Varennes, Vienne (from Le Ray Reference Le Ray and Simon-Hiernard2012, fig. 2). INH-L: Fampoux, Entre les Deux Chemins, Pas-de-Calais (from Debiak et al. Reference Debiak, Gaillard, Jacques and Rossignol1998, fig. 20.A). INH-M: Manor Farm, Portesham, Dorset (from Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick1996, fig. 2)

Regardless of the shape of the inhumation grave, in most of the sites where the age of individuals is known (74; 55% of the sample of 135 burials), the graves of children are generally shorter than those of adults. In one example, among the 13 burials of East Kent Access Road 2, Zone 12, the pits containing children are on average 0.63 × 0.31 m, those of adolescents are 1.35 × 0.61 m, those of adult females are 1.8 × 0.7 m, and those of adult males are 1.9 × 0.65 m (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Booth, Fitzpatrick and Welsh2015a). In the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes area, some graves appear to be either too small or too long for the body they house (Baray Reference Baray2003, 216). There are only a few examples from large cemeteries, but the heterogeneity of the pit sizes within the same site suggests that these graves were originally intended for different bodies. Regardless of the overall dimensions of the inhumation pits, they seem to have been designed according to the number of individuals, in the case of simultaneous plural deposits; to the size of the deceased, if a single burial; and to the position of the body.

Cremation graves

The cremation of bodies increased from the mid-3rd century bc and became the treatment mainly used in Belgic Gaul and then in south-east Britain from the 2nd century bc onwards. A sample of 100 cremation pits whose pit shapes and sizes were precisely known was selected from the 1114 funerary sites (9%). Four main shapes similar to the shapes of inhumation pits were identified (Table 2; Fig. 2), but they occur at different rates: quadrangular, rectangular, or square (49; 49%); circular, sub-circular, or oval (44; 44%); irregular-contoured, potato-shaped, or bean-shaped (5; 5%); and trapezoidal (2; 2%).

TABLE 2: MAIN SHAPES OF CREMATION GRAVES

Within the regions where cremation was the predominant body treatment (Fig. 1), the shapes of pits vary from one site to another and from one grave to another within the same cemetery. For example, at La Calotterie, La Fontaine aux Linottes, Pas-de-Calais, among the 40 cremation graves dated between the end of the 3rd century bc and the mid-1st century bc, the majority are oval or circular and some have irregular contours; others are rectangular, 8-shaped, or bean-shaped (Fig. 2, CR-E; Blancquaert & Desfossés Reference Blancquaert and Desfossés1998, 141–2). Trapezoidal pits are rarer for cremated remains but seem to be wider in size than the other shape categories (Mantel et al. Reference Mantel, Devillers and Dubois2002, 22–3).

From the 3rd–1st centuries bc, Belgic Gaul shows the greatest diversity of cremation pits. They can be distinguished both by their shapes and dimensions within the same funerary site (Fig. 2, CR-C1, CR-C2, CR-D1 & CR-D2). This distinction of certain graves suggests a personalisation of the sepulchral pit for each deceased person. It is in this same region that square pits often appear larger than rectangular ones (Fig. 2, CR-F). Although the vast majority of cremation graves are circular or quadrangular over the entire period studied, it is not possible to identify a dominance of one form over another according to the different phases of the period studied, due to the small sample of 100 cremation graves.

INTERNAL ARCHITECTURE

The archaeological evidence testifies to different internal arrangements or constructions in stone, wood, and other perishable materials, or they could have been dug directly into the sepulchral pits. The diverse types of installations can be interpreted from the material used for their construction, the traces left in the pits, or the movement or destruction of the human remains and objects during the disintegration of the architectural elements over time. A sample of 191 graves from the 1114 funerary sites (17%) was selected according to the accuracy of the information collected for the entire La Tène period and spread over the entire study area. Three main types of internal architecture material were identified: lithic (80; 42%); perishable material (62; 32%) and earth dug structures (49; 26%).

Lithic architecture

Of the 80 examples of lithic internal architecture identified within the study of 191 graves, five main types can be distinguished: slabs or blocks; cists or coffers; beds or floors; covers; and cephalic pillows. Most of the installations in stone are located in the western part of the study area, particularly in Armorica and Cornwall.

Slabs or blocks along the walls of a sepulchral pit served as wedging stones to structure the mortuary space (Fig. 3, A & B). Coffers or stone-lined chambers forming cists are characteristic of the granitic region of Cornwall. Other British areas, such as Wessex, also have stone cists, but fewer. They generally follow the shape of the pits in which they are built and are therefore principally rectangular or elongated, hexagonal, or, more rarely, circular. Different forms are sometimes found, such as at St Mary’s, Porthcressa, Isles of Scilly, where one of the 11 slab cists, dated to the mid-1st century bc, was boat-shaped (Johns Reference Johns2003, 64). The isolated burial of Bryher, Isles of Scilly, dated between the 2nd and mid-1st centuries bc, revealed the installation of an asymmetric quadrangular cist, measuring 1.5 × 0.93 m, made of stones and rubble with a cover of four granite slabs held by grey clay (Fig. 3, C; Johns Reference Johns2003, 11). An example of a cremation urn within a stone coffer is known at Plovan, Kergoglé, Finistère (Fig. 3, D; Le Roux Reference Le Roux1973, 73–4). The ceramic urn, dated between Hallstatt D3 and La Tène A, was in a coffer made of four vertical slabs with a cover in amphibolite positioned between granite blocks.

Fig. 3. Examples of cists or stone coffers. Redrawn and adapted by the author. A: Cist, single inhumation, Late Iron Age, King’s Road, Guernsey (from De Jersey Reference De Jersey2010, fig. 4). B: Stone coffer US 05, La Tène A, Quimper, Kerjaouen, Finistère (from Villard et al. Reference Villard, Le Bihan, Pluton and Gaumé2006, fig. 8). C: Granite slabs cist maintained with grey clay, possible double inhumation, Middle/Late Iron Age, Bryher, Isles of Scilly, Cornwall (from Johns Reference Johns2003, fig. 9). D: Square coffer in amphibolite slabs on granite blocks containing a ceramic urn, Hallstatt D3–La Tène A, Plovan Kergoglé, Finistère (from Le Roux Reference Le Roux1973, fig. 2)

Rocks or pebbles are sometimes found on the bottom of burial pits. This is regularly encountered in both inhumation and cremation graves in all the regions and periods studied, particularly on the continent. At Pétosse, Le Lelleton, Vendée, a man was buried during La Tène D1 in a prone position on a stone bed (Gomez de Soto et al. Reference Gomez de Soto, Villard-le-Tiec and Bouvet2010, 95).

Some mortuary practices testify to a desire to punish the dead until the burial or to prevent their possible return after death (Ragon Reference Ragon and Ragon1981, 43), as with individuals who were buried with their hands and/or feet bound or covered by heavy stones (Sharples Reference Sharples2010, 291). Studies of social anthropology and ethnology show that certain conditions of death are condemned according to the codes and standards agreed upon by members of the same sociocultural group (Albert Reference Albert1999, 144), which may explain this treatment.

In some Gallic and British burials, the head of the dead is held in an elevated position by a stone placed under the skull, which is known as a ‘cephalic pillow’ (Pinard et al. Reference Pinard, Delatrre and Thouvenot2009, 106). At Nonant-le-Pin, La Garenne, Calvados, blocks of flint were positioned under the heads of corpses in La Tène A burials (Edeine & Jigan Reference Edeine and Jigan1985, 112). A stone pillow was also discovered under the skull of the skeleton of Freshwater, Sheepwash, Isle of Wight (Whimster Reference Whimster1981, 323).

Perishable materials

Of the 62 constructions or installations made of perishable materials, there are five main categories: wooden formworks; platforms; floors or beddings; cob, wattle, and daub installations; and libation tubes.

The majority of the constructions made of perishable materials within burial pits are wooden formworks. This internal architecture can be discerned by post-holes, traces of planks along the side walls, or metal nails on the bottom of the burials (Merleau Reference Merleau2002, 203). Those containing a primary inhumation of an entire body, without prior treatment, offered an open decomposition space. Like some stone slabs or blocks, wooden formworks could have been used to maintain the walls of sepulchral pits (Gaudefroy & Pinard Reference Gaudefroy and Pinard1997, 103) and were often supported by stones or other materials (Cahen-Delhaye Reference Cahen-Delhaye1998, 68). Quadrangular wooden coffins or chambers are known in all the study areas at different periods. They were sometimes closed by flat or sloping roofs (Ginoux Reference Ginoux, Kruta and Leman-Delerive2007, 69). Some coffins or caskets have been conserved in wetlands, as in the La Tène D1 burial No. 30 at Urville-Nacqueville, Les Dunes, Manche (Rottier et al. Reference Rottier, Loyer and Herpoël2012, 142). Two conserved wooden caskets were also discovered within the warriors’ burials at Ashford, Brisley Farm, Kent, dated between ad 10 and 30 (Johnson Reference Johnson2002, fig. 5).

Post-holes in the corners and centre of burial pits can be interpreted as traces of a wooden platform (Table 2). For example, the La Tène D1b grave no. 222 at Bonneuil-en-France, Val-d’Oise contained evidence of a complex construction consisting of a floor supported by two oak planks, on which was placed a platform on stakes also made of oak (Lecomte-Schmitt & Le Forestier Reference Lecomte-Schmitt, Le Forestier, Carré and Henrion2012, 102). Traces of posts within the burials could also be evidence of a system of covering the pit. At Soliers, Parc d’Activités Eole–Le Bon Sauveur, Calvados, La Tène A burials contained four post-holes, which were interpreted as supporting a type of closing (Issenmann Reference Issenmann2011).

Some burials testify to the installation of wooden floors or straw beddings. They are relatively exceptional and appear more frequently in the cross-Channel regions than in the eastern margins of the study area. Among the 49 cremations dated between the 2nd and 1st centuries bc discovered at Bois-Guillaume, Les Bocquets, Seine-Maritime, only one revealed traces of a straw bedding and six others showed wooded floors (Merleau Reference Merleau2002, 45–242). At Hordain, ZAC La Fosse à Loup, Nord, a burial presented evidence of a wooden floor and roof, indicating the presence of coffers without supporting posts or sole plates (Séverin & Laloux Reference Séverin and Laloux2013, 59).

Some evidence of wattle and daub installations has been collected. At La Calotterie, La Fontaine aux Linottes, a site occupied between La Tène C1 and La Tène D1, structure no. 237 contained burnt bones covered by fragments of cob (Blancquaert & Desfossés Reference Blancquaert and Desfossés1998, 139). At Urville-Nacqueville, Les Dunes, grave no. 26, dated La Tène D1, contained the body of a child deposited between a wooden plank and a cover in wattle (Rottier et al. Reference Rottier, Loyer and Herpoël2012, 129).

An exceptional example of a libation tube has been recognised on a site occupied between La Tène C2 and the Gallo-Roman period at Estrées-Déniécourt, Derrière le Jardin du Berger, Somme. Here, hollow pieces of wood were placed at an angle to the grave (Prilaux Reference Prilaux, Kruta and Leman-Delerive2007).

It is difficult to determine a preference for a type of installation made in perishable material according to the biological sex or age of the dead based on these 62 examples. In a few cases, clear distinctions have been noted. For example, Le Forestier (Reference Le Forestier2009, 132) observed that 75% of timber formworks were built for children in the cemetery of Bobigny, Hôpital Avicenne, Seine-Saint-Denis.

Earth dug structures

Not all installations within graves were built. Some were dug directly into the bottom or walls of a burial pit. Of the 49 earth dug structures identified, three principle categories of these structures are known: notches or recesses; cells; and benches. These arrangements were mainly intended to accommodate architectural elements, the storage of grave goods, or the deposit of human remains. The earthen structures presented here were dug within continental graves, particularly those of the La Tène A–B Aisne–Marne–Ardennes burials.

As discussed above, notches in the corners of pits enabled the installation of nested planks of a formwork, and the overcutting of hollows in the bottom of burial pits were made for the deposit of a two-wheeled chariot (Table 1; Fig. 2, INH-D).

Hollow cells or compartments containing objects are less well known. Only a few examples are noted, mainly in the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes zone, such as in several La Tène A inhumation graves at Acy-Romance, La Croizette, Ardennes, where pottery was discovered in hollow compartments excavated within the sepulchral pit (Baray Reference Baray2003, 130). Some excavated cells are arranged to hold the head of the dead, as in burial 25 of Beine-Nauroy, L’argentelle, Marne, dated to the beginning of La Tène B1 (Baray Reference Baray2003, 130).

Earthen benches dug along burial pit walls were used for the deposit of grave goods (weapons, animal remains, etc) or human remains (cremated bones, secondary inhumation, etc). For example, burnt bones were discovered on a bench in a La Tène C1 grave at Vignacourt, Le Collège, Somme (Buchez Reference Buchez2011, 301), and a sword was found on a bench in the La Tène D1 grave 3 at Vismes-au-Val, Le Bois de Dix-Sept, Somme (Barbet & Bayard Reference Barbet and Bayard1996, 183).

Other materials

Rare floors or covers made of seashells are documented in graves from the end of the La Tène period on Armorican coasts and isles, as at Quiberon, Kerné, Morbihan, Saint-Jacut-de-la-Mer, Les Haches, and on the Isle of Ebihens, Côtes-d’Armor (Gomez de Soto et al. Reference Gomez de Soto, Villard-le-Tiec and Bouvet2010, 90).

Internal architecture: summary

Except for stone coffers, most internal architecture (mainly wooden constructions) is recorded in the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes funerary group during the first two centuries of the period studied. It is difficult, according to the data inventoried, to expose the characteristics of the internal architecture of the cross-Channel regions mainly known from the 3rd century bc onwards, except in Armorica and the Caen Plain–Orne area documented from the 5th and 4th centuries bc.

EXTERNAL ARCHITECTURE

Wooden, stone, or earthen architecture above and around graves both structure the funerary territory and locate the mortuary deposit. When burials are organised around a central and/or founder grave, it suggests the presence of a marker element that would have highlighted that grave for a possible secondary funerary deposit without risk of disturbing the initial burial. It also suggests the marker element was individualised and visible over a lengthy period of time. When burials within a funerary site have not been disturbed, even after several generations, this could indicate the presence of a perennial signalling element for each grave. On the contrary, when burials cross each other, contemporaneously or over a short period of time, this can indicate they did not have any signposting element or that the disturbance was voluntary. However, burials that disturb other funerary structures are rare within the surveyed sites of this study, which suggests a frequent and more or less permanent marking of grave locations.

The materials used in, and the forms and dimensions of, external architecture vary in time and space. Of the 1114 funerary sites in this study, a sample of 271 sites (24%) across the whole study period was selected on the basis on the degree of accuracy of known information regarding the types, shapes, and dimensions of the external construction. Of these 271, four main types of external architecture are distinguished: enclosures (176; 65%); barrows (52; 19%); buildings on posts (24; 9%); and standing stones (19; 7%).

Enclosures

Enclosures can delimit the funerary space on the scale of a single burial and/or a cemetery. They are the principal type of external architecture used throughout the period and geographical areas considered. Among the 176 sites with enclosures, the shapes are precisely known for 143 of them (81%). The other enclosures are irregular or not-well defined (33; 19%). Five main forms can be identified: quadrangular, rectangular, or square (90; 64% of 143); circular or oval (45; 32% of 143); trapezoidal (4; 3% of 143); horseshoe-shaped or U-shaped (open enclosures; 2; 1% of 143); and keyhole-shaped or champagne cork-shaped (2; 1% of 143).

Quadrangular enclosures are the most common in both Gaul and Britain during the period considered (Fig. 4). The vast majority are located to the north of the Seine, with a concentration of quadrangular enclosures around the Somme river and various types of ditched enclosures in the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes zone. They are also visible in fewer numbers scattered to the south of the Seine and the eastern half of southern Britain. The study of 90 quadrangular ditched enclosures reveals that they are more frequent in the sites containing only cremation graves (48%) than in funerary places with exclusively inhumations (32%) or those with both cremations and inhumations (20%). They can be rectangular but are more often square, and their dimensions are very varied from one funerary place to another and from one grave to another within the same site. Brittany shows the earliest preference for cremation, Hallstatt D/La Tène A, and here quadrangular ditched enclosures had an average dimension of 15–17 m on either side (Fig. 4, CR-A; Jahier et al. Reference Jahier, Le Maire, Gomez de Soto, Villard-le-Tiec, Lorho, Gautier and Naas2018). Taller quadrangular enclosures are also found, as at La Forêt Fouesnant, Poulgigou, Finistère, where a cremation grave enclosure measured 27 × 30 m (Daire et al. Reference Daire, Villard, Le Goff and Hingant1996, 136). From the 3rd century bc onwards, they are generally around 17 m2 in Belgic Gaul, with some local adaptations and differences. At Orval, Les Pleines, Manche, a La Tène C1 cremation and inhumation were located within the same 200 m2 ditched enclosure (Lepaumier et al. Reference Lepaumier, Giazzon and Chanson2010, 316). From the Middle La Tène period, some quadrangular enclosures around cremation burials joined together or to a settlement enclosure, forming groups or clusters of enclosures (Fig. 5). Rectangular-shaped enclosures can also surround wooden buildings on posts housing burials, as at Tartigny, Le Chemin du Moulin, Oise, where two cremations of the second half of the 3rd century BC were housed within wooden buildings surrounded by joined enclosures (Fig. 4, CR-E; Buchez Reference Buchez2011, 293).

Fig. 4. Typologies of diverse shapes of ditched enclosures. Redrawn and adapted by the author. CR-A: Melgven, Kerviguérou, Finistère (from Bouvet et al. Reference Bouvet, Daire, Le Bihan, Nillesse and Villard-le-Tiec2003, fig. 60). CR-B: Knesselare, East Flanders (from Leman-Delerive Reference Leman-Delerive2000, fig. 4). CR-C: Aalter, East Flanders (from Leman-Delerive Reference Leman-Delerive2000, fig. 4). CR-D: Sauchy-Lestrée, Le Prunier, Pas-de-Calais (from Lefèvre Reference Lefèvre2012, 182). CR-E: Tartigny, Le Chemin du Moulin, Oise (from Massy et al. Reference Massy, Mantel, Méniel and Rapin1986, fig. 2). CR-F: La Calotterie, La Fontaine aux Linottes, Pas-de-Calais (from Blancquaert & Desfossés Reference Blancquaert and Desfossés1998, fig. 8). CR-G: Allonville, Le Coquingnard, Somme (from Duval Reference Duval1976, fig. 12). CR-H: Saint-Gatien-des-Bois, Le Vert Buisson, Calvados (Lepaumier et al. Reference Lepaumier, San Juan, Verney, Hincker and Druon2006, 61). CR-I: Westhampnett, Sussex (from Sharples Reference Sharples2010, fig. 5.14). INH-A: Moncetz-Longevas, La Commune, Marne (Le Forestier Reference Le Forestier2009, fig. 2). INH-B: Évergnicourt Le Tournant du Chêne, Aisne (from Lambot & Méniel Reference Lambot and Méniel2005, fig. 3). INH-C: Reims, La Neuvillette, Marne (from Bonnabel Reference Bonnabel2013, fig. 61). INH-D: Orainville, La Croyère, Aisne (from Desenne et al. Reference Desenne, Collart, Auxiette, Martin, Rapin and Duvette2005, fig. 4). INH-E: Bucy-le-Long, Le Fond-du-Petit-Marais, Aisne (from Gransar Reference Gransar2009, fig. 1). INH-F: Adanac Park, Southampton, Hampshire (from Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2010, fig. 5). INH-G: Brisley Farm, Ashford, Kent (from Johnson Reference Johnson2002, fig. 2)

Fig. 5. Examples of clusters or pairs of quadrangular ditched enclosures. Redrawn and adapted by author. A: Colchester Stanway, Essex, AD 40-60, several cremations in ceramic urns (from Crummy Reference Crummy1997, 2). B: Kemzeke, East Flanders, Early La Tène, 12 cremations (from Leman-Delerive Reference Leman-Delerive2000, fig. 4). C: Ville-sur-Retourne, Budant à la Route de Pauvres, Ardennes, La Tène C2–La Tène D1b, 19 cremations (from Stead et al. Reference Stead, Flouest and Rigby2006, fig. 5.11). D: Tartigny, Le Chemin du Moulin, Oise, La Tène C1, 5 cremations (from Massy et al. Reference Massy, Mantel, Méniel and Rapin1986, fig. 2)

According to the study of 45 circular ditched enclosures, most are found in exclusively inhumation sites (69%). They are also found in places with only cremation graves (18%) and with both cremations and inhumations (13%). The inhumations within circular-shaped enclosures are mainly excavated in the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes zone and dated between Hallstatt D and La Tène B2 (Fig. 4, INH-A, INH-B, & INH-C). Post-holes in the bottom of enclosure ditches can be interpreted as the remains of a palisade. They are mainly seen to the north-east of the Seine, such as the palisaded enclosure of the grave OLC 004 dated between 300 and 250 bc at Orainville, La Croyère, Aisne (Fig. 4, INH-D; Desenne et al. Reference Desenne, Collart, Auxiette, Martin, Rapin and Duvette2005, 235–6). The ditches surrounding barrows form a type of enclosure. Most are circular, but some quadrangular-shaped ditches are also known. In Adanac Park, Southampton, Hampshire, of the seven barrows which each covered a central burial, dated between the Late and latest Iron Age, six were surrounded by a circular-shaped enclosure about 5–9 m in diameter, and one was framed by a square-shaped enclosure (Fig. 4, INH-F; Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2018, 75). There is also rare evidence of barrows surrounded by circular walls in Morbihan from the 5th century bc, as at Sérent, Carnac, and Le Bono (Gomez de Soto et al. Reference Gomez de Soto, Villard-le-Tiec and Bouvet2010, 85). The small number and peculiarity of the known trapezoidal, open, keyhole-shaped or champagne cork-shaped enclosures makes it impossible to present their general characteristics.

The spatio-temporal evolution of funerary enclosures shows diverse phases in different regions. During the 5th century bc, enclosures were fewer in the cross-Channel zone than the eastern margins of the study area, in particular the north of Central Gaul and the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes area, in which many enclosures were installed in large cemeteries where circular-shaped enclosures were more prevalent than quadrangular-shaped enclosures. From the 4th century bc onwards, there was a progressive increase in the construction of all types of ditched enclosures, with quadrangular-shaped enclosures becoming more prevalent than circular-shaped enclosures, especially in north-western Gaul. At the beginning of the 3rd century bc, the number of circular enclosures decreased, and quadrangular-shaped enclosures also appeared to decline. In the second half of the 3rd century bc, funerary practices stabilised after a period of change (which saw large cemeteries and new chariot burials) in Ⓘle-de-France (Marion Reference Marion2004), and after a period of decline (fewer burial sites) in the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes region. New cremations in Belgic Gaul were surrounded by quadrangular-shaped enclosures, particularly around the Somme river. Around 200 bc, there was an increase in quadrangular enclosures and a stagnation in circular enclosures, in part due to these new Belgic cremations and fewer ‘Aisne-Marne culture’ inhumations (Bonnabel Reference Bonnabel2013). From the mid-1st century bc, there was an expansion of cremation in south-east Britain and to the north of the Seine, but the total number of new enclosures declined very slightly. Indeed, there was a decline in all types of enclosures after the Gallic War, although British funerary sites with ditched enclosures were newly installed, particularly around cremation graves in the south-east. This decline can be explained by the progressive disappearance of indigenous Gallic funerary sites, and the increase in internal funerary architecture in southern Britain, such as stone cists in Dorset and Cornwall.

Barrows

Mounds of earth represent the second category of external funerary architecture and are few in comparison to enclosures (52; 19% of the sample of 271 sites). The majority of the barrows are dated to the beginning of the period considered. They are mainly located in the eastern regions of the study area, in the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes area, and the north of central Gaul. Barrows are also found near the southern coast of Brittany above graves mostly dated to the transition phase between the two continental Iron Ages in the mid-5th century bc (Milcent Reference Milcent1993; Jahier et al. Reference Jahier, Le Maire, Gomez de Soto, Villard-le-Tiec, Lorho, Gautier and Naas2018). The occasional barrow is also known from Belgic Gaul and southern Britain. For example, at Colchester-Lexden, Essex, a 31 m diameter and 2 m high circular mound is dated between the 1st century bc and the 1st century ad (Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2018, 76). The earthen mounds well known from the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age gradually disappeared from the 4th century bc onwards within the regions studied, becoming a clear minority to enclosures from the 3rd century bc.

Buildings on posts

Buildings on posts are infrequent on the sites included in this study (24; 9% of 271) and are almost exclusively located to the north of the Seine. They are generally erected on four or eight wooden posts and have various plans and dimensions. These buildings house inhumations in the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes group from La Tène A to La Tène B2 or cremations in Belgic Gaul from the second half of the 3rd century bc (Gransar & Malrain Reference Gransar and Malrain2009). For example, at Raillencourt-Sainte-Olle, Nord, a complex of four buildings, aligned within a rectangular enclosure, housed cremation graves dated between 140 and 60 bc (Bouche Reference Bouche2003). Some of these wooden buildings were built for several graves and others were installed on the funerary territory close to the burials, but they appear to be empty of human remains.

Standing stones

Standing stones mark the location of the grave or serve as an architectural element around which burials are organised (19; 7% of the sample of 271 sites). They are mainly attested in Armorica. The location of the graves could have been marked by wooden steles (Gomez de Soto et al. Reference Gomez de Soto, Villard-le-Tiec and Bouvet2010, 96). The Armorican standing stones are characteristic of the graves from the transition period of the two continental Iron Ages in the mid-5th century bc.

Carefully carved, generally from local granite, they are very variable in shape and size (about 0.40–3.0 m in height). They may be quadrangular, cylindrical, hemispherical, or truncated-cone shaped, and some are decorated with linear or curvilinear engraved patterns, such as: a frieze of ‘X’s, horizontal grooves, zigzag lines, St Andrew’s crosses, chevrons, or a Greek frieze. The rare Norman standing stones seem on average smaller than the Armorican stones. A 0.5 m high granite stele fragment was discovered in the La Tène C1 chariot burial of Orval, Les Pleines (Lepaumier et al. Reference Lepaumier, Giazzon and Chanson2010, 325), and a small standing stone in dolerite was found near three La Tène D1 cremations arranged in a triangle at Urville-Nacqueville, La Basse Batterie (Lefort Reference Lefort2015, 232).

Flat burials

Some burials lack outer architecture, other than the small mounds of earth formed by the backfilling of the grave pits at the time of their closures. They are mentioned in the literature consulted on both sides of the Channel and are often brought to light after the discovery of one or several graves with visible architecture installed in their immediate vicinity. The presence of these sober burials near others marked by external structures shows a hierarchy of the graves by their architecture within the same funerary site. In some cases, the simplicity of the flat burials is also observable in the treatment of the body and the deposit of the human remains, because they mainly house a primary inhumation without any form of internal construction in hard or perishable materials. Nevertheless, it is not excluded that another non-perennial type of installation or construction could have marked the location of these graves for a short period of time, such as elements made from perishable material laid on the ground.

External architecture: summary

Enclosures (mostly quadrangular) are the most widespread external elements from the 3rd century bc, especially in north-west Gaul and south-east England, areas which favoured cremation graves. Barrows well known in the Early Iron Age, on the other hand, seem to gradually disappear from the 4th century bc onwards. The Atlantic regions of the study area show particular choices in the external elements of the sepulchral places: Armorican standing stones are mainly known in the western part of the Peninsula during the beginning of the La Tène period, and in south-west Britain, Cornish stone cist burials had a peculiar lack of perennial external elements.

FUNERARY ARCHITECTURE AND REGIONAL GROUPS

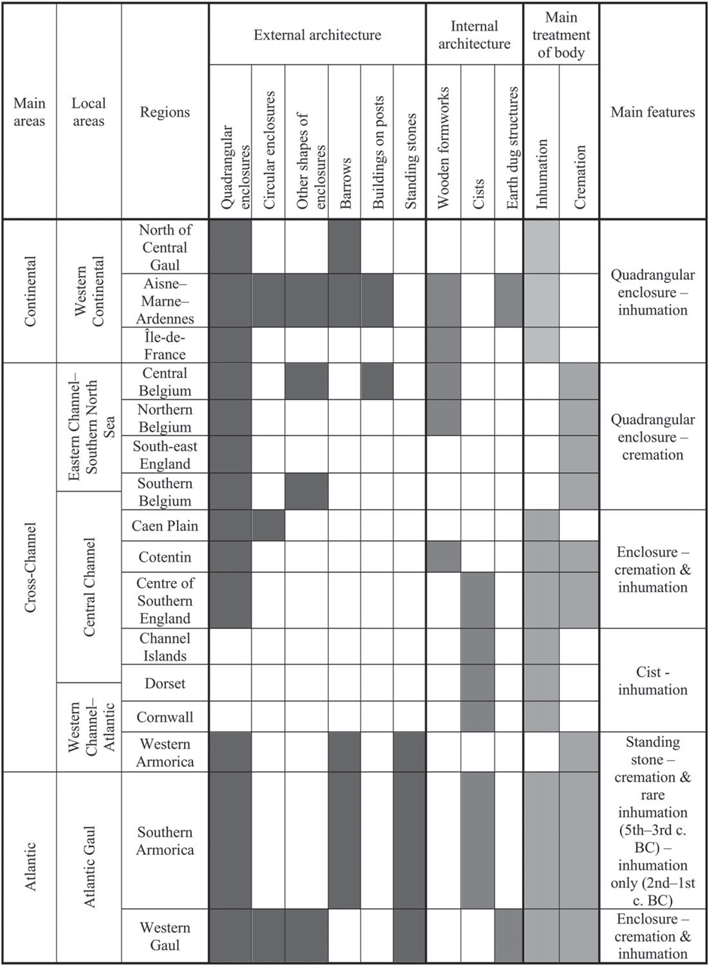

This study of the main internal and external grave architecture highlights regional differences in burial architecture between the mid-5th century and the mid-1st centuries ad (Fig. 6; Table 3). The regions identified can be understood as three large cross-Channel zones (Western Channel–Atlantic; Eastern Channel–Southern North Sea; Central Channel) and two subsequent zones (Atlantic Gaul, Western Continental). Although they are distinguished by their own local traditions, some of them show common general features.

TABLE 3: MAIN FUNERARY ARCHITECTURE OF THE DIFFERENT REGIONS WITHIN THE CROSS-CHANNEL, ATLANTIC, AND CONTINENTAL ZONES CONSIDERED

Fig. 6. Map of the different regions and geographical zones identified within the study area according to their main funerary architecture and treatment of body

The cross-Channel regions differ from those of the eastern and southern parts of the study area in regard to external architecture. Although enclosures are clearly present throughout the period concerned in the vast majority of the study area, a distinction is noted between the west and east of northern Gaul. Circular-shaped enclosures are found mainly in the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes group from La Tène A to La Tène C1. They are not well known in Belgic Gaul, where from the 3rd century bc onwards, quadrangular-shaped enclosures are the earliest type of external architecture. Barrows are also a distinguishing element, mostly installed in the eastern groups of the zone studied: Aisne–Marne–Ardennes and the north of central Gaul. The vast majority of La Tène period communities in the cross-Channel zone did not choose to mark the location of their burials with earthen mounds.

The granitic regions of the ‘Western Channel–Atlantic’ zone used local stones for the structuration of their burials, therefore stone coffers and standing stones are mainly visible in these areas. If we look at the body treatments and burial architecture studied here, it is obvious that Cornwall and Armorica, albeit very different from each other, are distinguished from the other cross-Channel regions. At the beginning of the period considered, the burial practices of north-western Gaul and southern Britain are not well documented, except in Brittany. Some graves of the southern Armorican peninsula were surmounted by a tumulus during the transition phase between Hallstatt D3 and La Tène A in the mid-5th century bc, showing a continuity of ancient practices. Western Armorica is distinguished in the same period by the predominance of cremations, standing stones, and the frequent delimitation of cemeteries with quadrangular ditched enclosures or palisades. Cornwall has the particularity of showing no perennial external architecture marking the location of burials, but the internal construction of a stone cist in the burial pit is characteristic of this region from the 2nd century bc onwards.

The ‘Eastern Channel–Southern North Sea’ zone is characterised by the predominance of cremation graves surrounded by quadrangular ditched enclosures. Northern Belgium is the oldest known area with isolated cremations and quadrangular enclosures, dated from the end of the 4th and the 3rd centuries bc (Leman-Delerive Reference Leman-Delerive2000; Oudry-Braillon Reference Oudry-Braillon2009; Leroy-Langelin et al. Reference Leroy-Langelin, Sergent, Séverin and Leman-Delerive2012; Rorive Reference Rorive2012). Central Belgium is distinguished by a high concentration of funerary sites around the Somme River, a diversity of pit shapes, and burial architecture with wooden buildings on posts and wooden formworks more common than in other groups of the cross-Channel zone. Southern Belgium shows similarities with the region of the Caen Plain–Orne River, with more diverse shapes of ditched enclosures around cremations or inhumations during the 2nd and the 1st centuries bc. In northern Gaul, the burials around the Oise River do not illustrate the diversity in the funerary architecture seen in both neighbouring areas. Why is this region, located between the concentration of cremations and quadrangular enclosures of central Belgium and the monumental burials of the Aisne–Marne–Ardennes group, soberer in its grave architecture? According to the dataset studied, the Oise seems to be a natural border between Belgic Gaul and the western Continental zone. It is possible that the Gallic communities of the plains and valleys of the Oise Rivers chose to differentiate themselves from their two great neighbours. However, this region shows practices similar to those of the ‘Aisne–Marne culture’ during the first half of the La Tène period and seems closer to the Belgic practices during the second half of the La Tène period (Malrain et al. Reference Malrain, Pinard and Gaudefroy1996; Gransar & Malrain Reference Gransar and Malrain2009). This illustrates the influence of each of the two groups during their respective period of predominance. The Oise area thus testifies to its role as a transitional or meeting territory between the Eastern Channel–Southern North Sea and Western Continental zones. In south-east England, the architecture of burials is less documented than in northern Gaul. However, according to known data, quadrangular-shaped enclosures around cremations are a majority, although there are fewer than in Belgic Gaul (Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2018, 77).

The regions in the ‘Central Channel’ zone can be seen as transitional areas, as they display practices influenced by the two neighbouring zones on either side, notably through the use of both cremation and inhumation, but also through the funerary architecture: diverse shapes of enclosures are present, even if in fewer number than the quadrangular-shaped enclosures in the ‘Eastern Channel–Southern North Sea’ zone. Nevertheless, they have their own particularities. Dorset appears similar to Cornwall in terms of the treatment of bodies (inhumation) and internal funerary architecture (cist). However, taking into account other data, the grave goods found in burials attributed to the ‘Durotriges’ reveal affinities with Gaul (Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick1996, 55). The discoveries of black shale bracelets from Kimmeridge in Guernsey and the Cotentin Peninsula attest to the trade of raw materials from the west to the east of the Channel, which also testifies to the cross-Channel position of Dorset (De Jersey Reference De Jersey2010, 291; Lefort Reference Lefort2015, 242). The Channel Islands and the Cotentin Peninsula show links with southern Britain and north-western Gaul, as seen in the burials of Urville-Nacqueville, Manche, which expose similarities to both Gallic and British funerary practices: cremation for the adults, inhumations in a folded position within wooden coffins for the children. A recent study of mitochondrial DNA haplotypes of individuals from Urville-Nacqueville cemetery exposed a wide diversity in the origins of women (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Lefort, Pemonge, Couture-Veschambre, Rottier and Deguilloux2018). These analyses revealed genetic sharing between the sample of individuals from this Iron Age site and ancient populations of the Bell Beaker period and the Bronze Age, and also those contemporary from the north of France, Spain, Great Britain, and regions of the Baltic and Central Europe. The archaeological evidence and genetic analyses confirm the central position of the Cotentin Peninsula in the trade route across the Channel and the long-distance mobility of prehistoric populations. Similarly, the studies of human bone isotopes from Kentish burials at Cliffs End Farm and the East Kent Access Road 2 have shown that some individuals were from the Continent, Scandinavia, and western Mediterranean, attesting to the mobility of Iron Age populations by sea (McKinley et al. Reference McKinley, Leivers, Schuster, Marshall and Barclay2014, 133–44; Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Booth, Fitzpatrick and Welsh2015b, 429–32).

The ‘Atlantic Gaul’ zone is not well documented, but it seems to show a greater heterogeneity of practices, both for the treatment of the body and the architecture of the burial. The La Tène period burials in this region are isolated and scattered between the Loire River and the Gironde Estuary. The known funerary sites contain both cremations and inhumations, and the rare architectural elements reveal some ditched enclosures and earth dug structures. The ‘Western Continental’ zone illustrates ancient monumental funerary architecture inherited from the first continental Iron Age, demonstrating the continuity of certain practices (such as chariot burials, circular enclosures, and barrows) during the transition phase between the Hallstatt and La Tène periods.

The cross-Channel regions have a privileged geographical position in contact with the continental and Atlantic cultural complexes, and the regionalisation of their funerary practices create a tripartition of maritime space (Fig. 6). This bears witness to cross-Channel contact and inter-influences between their different local regions throughout later prehistory.

CONCLUSION

A few general patterns can be noted. Grave shapes and the materials used in grave architecture do not seem to have been influenced by the treatment of the body: both cremations and inhumations were deposited in graves presenting complex structures in wood, stone, or earth. The internal and/or external elements of funerary architecture show a certain degree of personalisation of the burials, and the limited number of graves with monumental architecture illustrate a hierarchy of contemporary graves within the same site. Some structures, built or dug, were likely not made for burial architecture, but were intended for organising the site or possible collective rites (religious rituals, funerals, or commemorations). The funerary architecture characterising the five identified zones may allude to common gestures justified by similar beliefs, or they demonstrate the will of a community to distinguish itself from neighbouring areas through local particularities in grave layout that was sometimes related to ancient heritage.

The internal and external elements of funerary architecture point to a tripartition of the cross-Channel regions, especially from the 2nd to the end of the 1st century bc: Eastern Channel–Southern North Sea, Central Channel, and Western Channel–Atlantic. The funerary architecture also shows a regionalisation of practices on each side of the Channel, with local groups identified in Belgium, Caen Plain–Orne, the Cotentin Peninsula, Channel Islands, Western and Southern Armorica, Cornwall, Dorset, East Wessex, and southern England. The regions within each zone often show closer affinities with those groups on either side of the Channel, than with their direct neighbours in other zones. By defining these cross-Channel funerary zones, it is also possible to differentiate them from the Western Continental and Atlantic Gaul zones. The study of the bodies, funerary architecture, and grave goods together is necessary for an overall understanding of the funerary practices of the populations in the cross-Channel area, which will lead to a better understanding of Iron Age Gallic and British communities and the nature of their relationship.