1. Introduction

Mixed convection, driven by both shear and buoyancy forces, occurs ubiquitously in nature and has widespread applications in industry (Caulfield Reference Caulfield2021). For example, this complex interaction is essential for understanding the behaviour of atmospheric currents, where stratification can be stable (warmer air above cooler layers), unstable (lower layers are heated and rising) or neutral (temperature gradient minimal affecting air movements) (Zhang, Tan & Zheng Reference Zhang, Tan and Zheng2023; Zhang Reference Zhang2024). During the day, unstable stratification can form large longitudinally aligned rollers (Brown Reference Brown1980; Young et al. Reference Young, Kristovich, Hjelmfelt and Foster2002; Dror et al. Reference Dror, Koren, Liu and Altaratz2023). These structures generate rows of cumulus clouds and create striped patterns on sand dunes (Hanna Reference Hanna1969; Andreotti et al. Reference Andreotti, Fourriere, Ould-Kaddour, Murray and Claudin2009; Kok et al. Reference Kok, Parteli, Michaels and Karam2012). At night, the atmospheric boundary layer is usually stably stratified, with temperature increasing with height, inhibiting vertical mixing and resulting in a more layered, less turbulent atmosphere (Nieuwstadt Reference Nieuwstadt1984). Another example is in nuclear engineering, where mixed convection is crucial for designing and operating Generation IV nuclear reactors, such as sodium-cooled and lead-cooled fast reactors. A key component of these reactors is the primary circuit, where heat generated from nuclear fission is transferred to a coolant before being converted to steam for electricity generation (Komen et al. Reference Komen, Mathur, Roelofs, Merzari and Tiselj2023). Paradigms for studying mixed convection include the Poiseuille–Rayleigh–Bénard (PRB) and the Couette–Rayleigh–Bénard (CRB) systems, which combine Poiseuille (or Couette) flow with Rayleigh–Bénard (RB) convective flow. Although extensive efforts have been devoted to studying shear-driven wall turbulence in Poiseuille flow (or Couette flow) systems (Marusic et al. Reference Marusic, McKeon, Monkewitz, Nagib, Smits and Sreenivasan2010; Smits, McKeon & Marusic Reference Smits, McKeon and Marusic2011; Jiménez Reference Jiménez2012; Graham & Floryan Reference Graham and Floryan2021; Marusic et al. Reference Marusic, Chandran, Rouhi, Fu, Wine, Holloway, Chung and Smits2021; Yao, Chen & Hussain Reference Yao, Chen and Hussain2022; Yao et al. Reference Yao, Chen and Hussain2022; Chen & Sreenivasan Reference Chen and Sreenivasan2023), and buoyancy-driven thermal turbulence in RB systems (Ahlers, Grossmann & Lohse Reference Ahlers, Grossmann and Lohse2009; Lohse & Xia Reference Lohse and Xia2010; Chilla, Evrard & Schulz Reference Chilla, Evrard and Schulz2012; Wang, Zhou & Sun Reference Wang, Zhou and Sun2020; Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Zhu, Wang, Huisman and Sun2020; Xia et al. Reference Xia, Huang, Xie and Zhang2023; Lohse & Shishkina Reference Lohse and Shishkina2024; Lohse Reference Lohse2024), the interplay between horizontal shear and vertical buoyancy in mixed convection remains relatively less understood.

In turbulent channel flows with stable temperature stratification, fluid density increases with depth, and buoyancy forces act to return displaced fluid parcels to their original position, causing oscillations around the equilibrium point and forming internal gravity waves (Zonta, Sichani & Soldati Reference Zonta, Sichani and Soldati2022). In contrast, in turbulent channel flows with unstable temperature stratification, thermal plumes significantly influence momentum and heat transport from the wall (Komori et al. Reference Komori, Ueda, Ogino and Mizushina1982; Iida & Kasagi Reference Iida and Kasagi1997). When heat conduction in the bottom wall is coupled with fluid flow in the channel, the thermal properties and thickness of the conducting solid wall strongly affect the solid–fluid interfacial temperatures (Garai, Kleissl & Sarkar Reference Garai, Kleissl and Sarkar2014). Pirozzoli et al. (Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017) and Blass et al. (Reference Blass, Zhu, Verzicco, Lohse and Stevens2020, Reference Blass, Tabak, Verzicco, Stevens and Lohse2021) found that at high friction Reynolds number (

![]() $Re_{\tau }$

, describing the shear strength) and high Rayleigh number (

$Re_{\tau }$

, describing the shear strength) and high Rayleigh number (

![]() $Ra$

, describing the buoyancy strength) in both PRB and CRB systems, large-scale quasistreamwise roll structures form, occupying the entire channel height, a behaviour not observed in pure turbulent channel flow or pure turbulent RB convection. Using the direct numerical simulation (DNS) data of Pirozzoli et al. (Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017), Madhusudanan et al. (Reference Madhusudanan, Illingworth, Marusic and Chung2022) developed a linearized Navier–Stokes-based model that accurately captures the trends of these quasistreamwise rolls, emphasizing the significant impact of the relative effect of shear and buoyancy (characterized by the Richardson number

$Ra$

, describing the buoyancy strength) in both PRB and CRB systems, large-scale quasistreamwise roll structures form, occupying the entire channel height, a behaviour not observed in pure turbulent channel flow or pure turbulent RB convection. Using the direct numerical simulation (DNS) data of Pirozzoli et al. (Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017), Madhusudanan et al. (Reference Madhusudanan, Illingworth, Marusic and Chung2022) developed a linearized Navier–Stokes-based model that accurately captures the trends of these quasistreamwise rolls, emphasizing the significant impact of the relative effect of shear and buoyancy (characterized by the Richardson number

![]() $Ri_b$

) on the predicted coherent structures. Meanwhile, Cossu (Reference Cossu2022) showed that the linear instability of turbulent mean flow to coherent perturbations is linked to the onset of large-scale rolls and predicted the critical Rayleigh number for their formation. Recently, Howland et al. (Reference Howland, Yerragolam, Verzicco and Lohse2024) studied a differentially heated vertical channel subject to a Poiseuille-like horizontal pressure gradient, which is relevant to industrial heat exchangers in applied thermal engineering.

$Ri_b$

) on the predicted coherent structures. Meanwhile, Cossu (Reference Cossu2022) showed that the linear instability of turbulent mean flow to coherent perturbations is linked to the onset of large-scale rolls and predicted the critical Rayleigh number for their formation. Recently, Howland et al. (Reference Howland, Yerragolam, Verzicco and Lohse2024) studied a differentially heated vertical channel subject to a Poiseuille-like horizontal pressure gradient, which is relevant to industrial heat exchangers in applied thermal engineering.

In the exploration of turbulent flows driven by time-dependent forcing, such as atmospheric circulation driven by the Sun’s radiation causing daily warming and cooling cycles, efforts have been made to investigate temporally modulated turbulent RB convection. For example, Jin & Xia (Reference Jin and Xia2008) experimentally imposed periodic pulses of energy to drive the convective flow, achieving a 7 % increase in heat transfer efficiency as measured by the Nusselt number (

![]() $Nu$

). Niemela & Sreenivasan (Reference Niemela and Sreenivasan2008) experimentally assessed the flow structure under sinusoidal heating modulation at the lower boundary and discovered a core region with near-superconducting behaviour, where thermal waves propagate without attenuation. Due to experimental challenges in achieving a broad range of modulation frequencies, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Chong, Wang, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2020) performed DNS over four orders of magnitude of modulation frequencies and reported an appreciable enhancement of

$Nu$

). Niemela & Sreenivasan (Reference Niemela and Sreenivasan2008) experimentally assessed the flow structure under sinusoidal heating modulation at the lower boundary and discovered a core region with near-superconducting behaviour, where thermal waves propagate without attenuation. Due to experimental challenges in achieving a broad range of modulation frequencies, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Chong, Wang, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2020) performed DNS over four orders of magnitude of modulation frequencies and reported an appreciable enhancement of

![]() $Nu$

by up to 25 %. Using the concept of the Stokes thermal boundary layer, they explained the onset frequency of the

$Nu$

by up to 25 %. Using the concept of the Stokes thermal boundary layer, they explained the onset frequency of the

![]() $Nu$

enhancement and the optimal frequency at which

$Nu$

enhancement and the optimal frequency at which

![]() $Nu$

is maximal. Later, Urban et al. (Reference Urban, Hanzelka, Králik, Musilová and Skrbek2022) used helium gas in cryogenic conditions to create convection cells that respond quickly to temperature changes, allowing them to achieve high modulation amplitudes and a wide range of frequencies. Their results confirmed the numerical predictions of Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Chong, Wang, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2020) regarding the significant enhancement of

$Nu$

is maximal. Later, Urban et al. (Reference Urban, Hanzelka, Králik, Musilová and Skrbek2022) used helium gas in cryogenic conditions to create convection cells that respond quickly to temperature changes, allowing them to achieve high modulation amplitudes and a wide range of frequencies. Their results confirmed the numerical predictions of Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Chong, Wang, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2020) regarding the significant enhancement of

![]() $Nu$

. These advances in understanding temporally modulated buoyancy-driven natural convection lead to the question of how temporal modulation affects flow organization and heat transfer efficiency in mixed convection.

$Nu$

. These advances in understanding temporally modulated buoyancy-driven natural convection lead to the question of how temporal modulation affects flow organization and heat transfer efficiency in mixed convection.

In this work, we aim to investigate the effects of temporal modulation on mixed convection in turbulent channels. Motivated by the studies of atmospheric currents in desert regions, we consider stable, unstable or neutral stratification conditions, achieved by temporally modulating the bottom wall temperature. Based on data from moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer observations (Sharifnezhadazizi et al. Reference Sharifnezhadazizi, Norouzi, Prakash, Beale and Khanbilvardi2019), we applied sinusoidal modulation to the bottom wall to mimic diurnal variations in land surface temperature. By analysing turbulent quantities over time within the modulation period, we can unravel the transient mechanisms and phase dynamics of the flow structure (Manna, Vacca & Verzicco Reference Manna, Vacca and Verzicco2015; Ebadi et al. Reference Ebadi, White, Pond and Dubief2019). The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In

![]() $\S$

2, we present numerical details for the DNS of mixed convection. In

$\S$

2, we present numerical details for the DNS of mixed convection. In

![]() $\S$

3, we first describe the instantaneous flow and heat transfer features in the temporally modulated mixed convection channel, followed by an analysis of long-time-averaged statistics and phase-averaged statistics. The long-time-averaged quantity is calculated as

$\S$

3, we first describe the instantaneous flow and heat transfer features in the temporally modulated mixed convection channel, followed by an analysis of long-time-averaged statistics and phase-averaged statistics. The long-time-averaged quantity is calculated as

![]() $\overline {\mathbb {F}}(\mathbf {x})=\lim _{N_{{total}}\to \infty }[\sum \mathbb {F}(\mathbf {x},t)]/N_{{total}}$

, where

$\overline {\mathbb {F}}(\mathbf {x})=\lim _{N_{{total}}\to \infty }[\sum \mathbb {F}(\mathbf {x},t)]/N_{{total}}$

, where

![]() $\mathbb {F}(\mathbf {x},t)$

is the instantaneous field and

$\mathbb {F}(\mathbf {x},t)$

is the instantaneous field and

![]() $N_{{total}}$

is the total snapshot number of the instantaneous field. The phase-averaged quantity

$N_{{total}}$

is the total snapshot number of the instantaneous field. The phase-averaged quantity

![]() $\langle \mathbb {F} (\mathbf {x} ) \rangle _{\phi }$

is calculated as

$\langle \mathbb {F} (\mathbf {x} ) \rangle _{\phi }$

is calculated as

![]() $\langle \mathbb {F}(\mathbf {x})\rangle _{\phi }=\lim _{N_{{cycles}}\to \infty }[\sum \mathbb {F}(\mathbf {x},t_k)]/N_{{cycles}}$

, where

$\langle \mathbb {F}(\mathbf {x})\rangle _{\phi }=\lim _{N_{{cycles}}\to \infty }[\sum \mathbb {F}(\mathbf {x},t_k)]/N_{{cycles}}$

, where

![]() $N_{{cycles}}$

is the number of cycles and

$N_{{cycles}}$

is the number of cycles and

![]() $t_k$

are the times corresponding to the phase

$t_k$

are the times corresponding to the phase

![]() $\phi$

. In

$\phi$

. In

![]() $\S$

4, the main findings of the present work are summarized.

$\S$

4, the main findings of the present work are summarized.

2. Numerical method

2.1. Direct numerical simulation of thermal turbulence

In incompressible thermal convection, we employ the Boussinesq approximation to account for temperature as an active scalar that influences the velocity field through buoyancy effects in the vertical direction, assuming constant transport coefficients. The flow is also driven by a body force (or equivalently a mean pressure gradient) that accounts for shear effects in the horizontal direction. The equations governing fluid flow and heat transfer can be written as

Here,

![]() ${\boldsymbol {u}}$

is the fluid velocity and

${\boldsymbol {u}}$

is the fluid velocity and

![]() $P$

and

$P$

and

![]() $T$

are the pressure and temperature of the fluid, respectively. The coefficients

$T$

are the pressure and temperature of the fluid, respectively. The coefficients

![]() $\beta$

,

$\beta$

,

![]() $\nu$

and

$\nu$

and

![]() $\alpha$

denote the thermal expansion coefficient, kinematic viscosity and thermal diffusivity, respectively. Reference state variables are indicated by subscript zeros. The vectors

$\alpha$

denote the thermal expansion coefficient, kinematic viscosity and thermal diffusivity, respectively. Reference state variables are indicated by subscript zeros. The vectors

![]() $\hat {\mathbf {x}}$

and

$\hat {\mathbf {x}}$

and

![]() $\hat {\mathbf {y}}$

are unit vectors in the streamwise and wall-normal directions, respectively. The term

$\hat {\mathbf {y}}$

are unit vectors in the streamwise and wall-normal directions, respectively. The term

![]() $g$

represents the gravitational acceleration in the wall-normal direction. The term

$g$

represents the gravitational acceleration in the wall-normal direction. The term

![]() $f_b$

represents a body force used to maintain a constant bulk flow rate in the streamwise direction. This forcing is spatially uniform but time-dependent, allowing precise control over the flow rate at each time step (Pirozzoli et al. Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017). While a constant pressure gradient is commonly used to drive flow in channel simulations, in the presence of buoyancy forces, a constant pressure gradient can lead to variations in the bulk flow rate, as buoyancy may either enhance or oppose the mean flow depending on the temperature distribution. By maintaining a constant flow rate in mixed convection, we can use the mean flow strength as a control parameter, allowing us to effectively attribute changes in flow behaviour to specific factors such as thermal stratification or flow strength.

$f_b$

represents a body force used to maintain a constant bulk flow rate in the streamwise direction. This forcing is spatially uniform but time-dependent, allowing precise control over the flow rate at each time step (Pirozzoli et al. Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017). While a constant pressure gradient is commonly used to drive flow in channel simulations, in the presence of buoyancy forces, a constant pressure gradient can lead to variations in the bulk flow rate, as buoyancy may either enhance or oppose the mean flow depending on the temperature distribution. By maintaining a constant flow rate in mixed convection, we can use the mean flow strength as a control parameter, allowing us to effectively attribute changes in flow behaviour to specific factors such as thermal stratification or flow strength.

We introduce the non-dimensional variables

where

![]() $u_b$

is the bulk velocity,

$u_b$

is the bulk velocity,

![]() $H$

denotes the channel height and

$H$

denotes the channel height and

![]() $\Delta _T = T_{{hot}}-T_{{cold}}$

is the temperature difference between the heating and cooling walls. We can rewrite (2.1)–(2.3) in dimensionless form:

$\Delta _T = T_{{hot}}-T_{{cold}}$

is the temperature difference between the heating and cooling walls. We can rewrite (2.1)–(2.3) in dimensionless form:

Here, the control dimensionless parameters include the bulk Reynolds number (

![]() $Re_{b}$

), Rayleigh number (

$Re_{b}$

), Rayleigh number (

![]() $Ra$

) and Prandtl number (

$Ra$

) and Prandtl number (

![]() $Pr$

), which are defined as

$Pr$

), which are defined as

The global competition between shear and buoyancy effects can be quantified by the bulk Richardson number (

![]() $Ri_b$

) as

$Ri_b$

) as

![]() $Ri_b=Ra/(Re_b^2 Pr)$

. The extreme cases of

$Ri_b=Ra/(Re_b^2 Pr)$

. The extreme cases of

![]() $Ri_b = 0$

represent purely shear driving and

$Ri_b = 0$

represent purely shear driving and

![]() $Ri_b=\infty$

represents purely buoyancy driving. We adopt the finite volume method (FVM) implemented in the open-source OpenFOAM solver (Version 8) for DNS. Specifically, we use the transient buoyantPimpleFoam solver with the turbulence model turned off. Convective terms and viscous terms are discretized using a second-order central differencing scheme, while temporal terms are discretized using a second-order implicit backward differencing scheme based on three time levels. Pressure–velocity coupling is achieved with the pressure-implicit splitting of operators (PISO) algorithm, with PISO corrections set to four, following the settings by Komen et al. (Reference Komen, Shams, Camilo and Koren2014). For the momentum equation, we use a preconditioned biconjugate gradient method designed for asymmetric matrices, along with diagonal-based incomplete LU preconditioning. The pressure equation is solved using the geometric agglomerated algebraic multigrid method. Time advancement is controlled by adaptive time stepping, with the adaptive time step regulated by the cell-face Courant number, keeping the maximum cell-face Courant numbers below 0.5. More numerical details and validation of the OpenFOAM solver can be found in Komen et al. (Reference Komen, Shams, Camilo and Koren2014, Reference Komen, Camilo, Shams, Geurts and Koren2017) and Kooij et al. (Reference Kooij, Botchev, Frederix, Geurts, Horn, Lohse, van der Poel, Shishkina, Stevens and Verzicco2018). To verify our OpenFOAM results, we also conducted simulations at

$Ri_b=\infty$

represents purely buoyancy driving. We adopt the finite volume method (FVM) implemented in the open-source OpenFOAM solver (Version 8) for DNS. Specifically, we use the transient buoyantPimpleFoam solver with the turbulence model turned off. Convective terms and viscous terms are discretized using a second-order central differencing scheme, while temporal terms are discretized using a second-order implicit backward differencing scheme based on three time levels. Pressure–velocity coupling is achieved with the pressure-implicit splitting of operators (PISO) algorithm, with PISO corrections set to four, following the settings by Komen et al. (Reference Komen, Shams, Camilo and Koren2014). For the momentum equation, we use a preconditioned biconjugate gradient method designed for asymmetric matrices, along with diagonal-based incomplete LU preconditioning. The pressure equation is solved using the geometric agglomerated algebraic multigrid method. Time advancement is controlled by adaptive time stepping, with the adaptive time step regulated by the cell-face Courant number, keeping the maximum cell-face Courant numbers below 0.5. More numerical details and validation of the OpenFOAM solver can be found in Komen et al. (Reference Komen, Shams, Camilo and Koren2014, Reference Komen, Camilo, Shams, Geurts and Koren2017) and Kooij et al. (Reference Kooij, Botchev, Frederix, Geurts, Horn, Lohse, van der Poel, Shishkina, Stevens and Verzicco2018). To verify our OpenFOAM results, we also conducted simulations at

![]() $Re_b \approx 3162$

,

$Re_b \approx 3162$

,

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

and

$Ra = 10^7$

and

![]() $Pr = 1$

using an in-house solver based on the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) (Xu, Shi & Zhao Reference Xu, Shi and Zhao2017; Xu & Li Reference Xu and Li2023; Xu & Li Reference Xu and Li2023). The results from both the open-source OpenFOAM solver and the in-house lattice Boltzmann solver were consistent, as discussed in appendix A.

$Pr = 1$

using an in-house solver based on the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) (Xu, Shi & Zhao Reference Xu, Shi and Zhao2017; Xu & Li Reference Xu and Li2023; Xu & Li Reference Xu and Li2023). The results from both the open-source OpenFOAM solver and the in-house lattice Boltzmann solver were consistent, as discussed in appendix A.

2.2. Simulation settings

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the temporally modulated mixed convection channel.

We explore the dynamics of mixed convection within a three-dimensional (3-D) channel of dimensions

![]() $L \times H \times W$

, as illustrated in figure 1. Here,

$L \times H \times W$

, as illustrated in figure 1. Here,

![]() $L$

is the length,

$L$

is the length,

![]() $H$

is the height and

$H$

is the height and

![]() $W$

is the width of the simulation domain,

$W$

is the width of the simulation domain,

![]() $x$

denotes the streamwise direction,

$x$

denotes the streamwise direction,

![]() $y$

denotes the wall-normal direction and

$y$

denotes the wall-normal direction and

![]() $z$

denotes the spanwise direction. The computational domain size is chosen as

$z$

denotes the spanwise direction. The computational domain size is chosen as

![]() $2\pi h \times 2h \times \pi h$

to ensure the spanwise domain size is close to the minimal spanwise size required to achieve developed turbulence in mixed convection simulations (Pirozzoli et al. Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017). Here,

$2\pi h \times 2h \times \pi h$

to ensure the spanwise domain size is close to the minimal spanwise size required to achieve developed turbulence in mixed convection simulations (Pirozzoli et al. Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017). Here,

![]() $h=H/2$

is the half-height of the channel. Periodic boundary conditions for velocity and temperature are applied in the streamwise and spanwise directions to exploit statistical homogeneity. In the wall-normal direction, no-slip velocity boundary conditions are imposed on the top and bottom walls of the channel. The grid size distribution is symmetric about the midplane, with cell sizes increasing geometrically from the wall to the bulk using a geometric progression. Specifically, the cell size for the

$h=H/2$

is the half-height of the channel. Periodic boundary conditions for velocity and temperature are applied in the streamwise and spanwise directions to exploit statistical homogeneity. In the wall-normal direction, no-slip velocity boundary conditions are imposed on the top and bottom walls of the channel. The grid size distribution is symmetric about the midplane, with cell sizes increasing geometrically from the wall to the bulk using a geometric progression. Specifically, the cell size for the

![]() $i$

th grid

$i$

th grid

![]() $\Delta y_{i}$

can be defined as

$\Delta y_{i}$

can be defined as

![]() $\Delta y_{i} = \Delta y_{{wall}} q^{i-1}$

(for

$\Delta y_{i} = \Delta y_{{wall}} q^{i-1}$

(for

![]() $i=1,2,\ldots ,M$

), where

$i=1,2,\ldots ,M$

), where

![]() $\Delta y_{{wall}}$

is the starting cell size,

$\Delta y_{{wall}}$

is the starting cell size,

![]() $q$

is the common ratio of the geometric progression and

$q$

is the common ratio of the geometric progression and

![]() $M$

is the number of cells in the half-channel. The expansion ratio

$M$

is the number of cells in the half-channel. The expansion ratio

![]() $r$

of the cell size, defined as the ratio of the end cell size

$r$

of the cell size, defined as the ratio of the end cell size

![]() $\Delta y_{{bulk}}$

to the starting cell size

$\Delta y_{{bulk}}$

to the starting cell size

![]() $\Delta y_{{wall}}$

, is expressed as

$\Delta y_{{wall}}$

, is expressed as

![]() $r=\Delta y_{{bulk}} / \Delta y_{{wall}}$

. This gives

$r=\Delta y_{{bulk}} / \Delta y_{{wall}}$

. This gives

![]() $q=r^{1/(M-1)}$

and

$q=r^{1/(M-1)}$

and

![]() $\Delta y_{{wall}}=h(1-q)/(1-q^M)$

. We set

$\Delta y_{{wall}}=h(1-q)/(1-q^M)$

. We set

![]() $r=8$

for

$r=8$

for

![]() $Ra = 10^6$

and

$Ra = 10^6$

and

![]() $r=5$

for

$r=5$

for

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

and

$Ra = 10^7$

and

![]() $10^8$

in the simulations. We referenced the grid set-up used by Pirozzoli et al. (Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017), which is based on the resolution requirements for pure buoyant flow (Shishkina et al. Reference Shishkina, Stevens, Grossmann and Lohse2010) and pure channel flow (Bernardini, Pirozzoli & Orlandi Reference Bernardini, Pirozzoli and Orlandi2014). We performed an a posteriori validation for all simulation cases, ensuring that the grid size in each coordinate direction is less than three Kolmogorov units in all cases.

$10^8$

in the simulations. We referenced the grid set-up used by Pirozzoli et al. (Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017), which is based on the resolution requirements for pure buoyant flow (Shishkina et al. Reference Shishkina, Stevens, Grossmann and Lohse2010) and pure channel flow (Bernardini, Pirozzoli & Orlandi Reference Bernardini, Pirozzoli and Orlandi2014). We performed an a posteriori validation for all simulation cases, ensuring that the grid size in each coordinate direction is less than three Kolmogorov units in all cases.

For the temperature boundary condition, the top wall is maintained at a constant low temperature of

![]() $T_{{top}}=T_{{cold}}$

, while the bottom wall is subjected to a sinusoidal modulation

$T_{{top}}=T_{{cold}}$

, while the bottom wall is subjected to a sinusoidal modulation

![]() $T_{{bottom}}=T_{{hot}}+A(T_{{hot}}-T_{{cold}})\sin (2\pi ft)$

. Here,

$T_{{bottom}}=T_{{hot}}+A(T_{{hot}}-T_{{cold}})\sin (2\pi ft)$

. Here,

![]() $A$

is the modulation amplitude,

$A$

is the modulation amplitude,

![]() $f$

is the modulation frequency and

$f$

is the modulation frequency and

![]() $t$

is time. We define the phase angle of the modulation as

$t$

is time. We define the phase angle of the modulation as

![]() $\phi =2\pi ft$

, and this phase angle

$\phi =2\pi ft$

, and this phase angle

![]() $\phi$

will be used to describe the temporal progression of the modulation. The modulation amplitude is fixed as

$\phi$

will be used to describe the temporal progression of the modulation. The modulation amplitude is fixed as

![]() $A = 2$

, resulting in a temperature difference

$A = 2$

, resulting in a temperature difference

![]() $\Delta _T^*= (T_{{bottom}}-T_{{top}} )/ (T_{{hot}}-T_{{cold}} )=1+2\sin (2\pi ft )$

, covering the regimes of unstable stratification (

$\Delta _T^*= (T_{{bottom}}-T_{{top}} )/ (T_{{hot}}-T_{{cold}} )=1+2\sin (2\pi ft )$

, covering the regimes of unstable stratification (

![]() $\Delta _{T} \gt 0$

), neutral stratification (

$\Delta _{T} \gt 0$

), neutral stratification (

![]() $\Delta _{T}=0$

) and stable stratification (

$\Delta _{T}=0$

) and stable stratification (

![]() $\Delta _{T}\lt 0$

). Previously, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Chong, Wang, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2020) fixed the modulation amplitude as

$\Delta _{T}\lt 0$

). Previously, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Chong, Wang, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2020) fixed the modulation amplitude as

![]() $A = 1$

in RB convection, which did not explore the stable stratification cases because

$A = 1$

in RB convection, which did not explore the stable stratification cases because

![]() $A = 1$

leads to

$A = 1$

leads to

![]() $\Delta _{T}\geqslant 0$

. We adopt the buoyancy time scale

$\Delta _{T}\geqslant 0$

. We adopt the buoyancy time scale

![]() $t_{f}=\sqrt {H/(g\beta \Delta _{T})}$

to non-dimensionalize the modulation period

$t_{f}=\sqrt {H/(g\beta \Delta _{T})}$

to non-dimensionalize the modulation period

![]() $T_{{period}}$

as

$T_{{period}}$

as

![]() $T_{{period}}^{*}=T_{{period}}/t_{f}$

(Yang et al. Reference Yang, Chong, Wang, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2020). We set the dimensionless modulation frequency

$T_{{period}}^{*}=T_{{period}}/t_{f}$

(Yang et al. Reference Yang, Chong, Wang, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2020). We set the dimensionless modulation frequency

![]() $f^{*}$

in the range

$f^{*}$

in the range

![]() $0.01\leqslant f^{*}=1/T_{{period}}^{*}=t_{f}/T_{{period}} \leqslant 1$

. Another approach is to adopt the bulk convective time scale

$0.01\leqslant f^{*}=1/T_{{period}}^{*}=t_{f}/T_{{period}} \leqslant 1$

. Another approach is to adopt the bulk convective time scale

![]() $t_{b}=H/u_{b}$

to non-dimensionalize the modulation period as

$t_{b}=H/u_{b}$

to non-dimensionalize the modulation period as

![]() $T_{{period}}^{*}=T_{{period}}/t_{b}$

. In this case, the modulation frequency is given by

$T_{{period}}^{*}=T_{{period}}/t_{b}$

. In this case, the modulation frequency is given by

![]() $f^{*}_{b}=t_{b}/T_{{period}}=f^{*}t_{b}/t_{f}$

, leading to

$f^{*}_{b}=t_{b}/T_{{period}}=f^{*}t_{b}/t_{f}$

, leading to

![]() $f^{*}_{b}=\sqrt {Ri_{b}}f^{*}$

. Because the wall temperature modulation changes the buoyancy within the flow system, we will focus on discussing

$f^{*}_{b}=\sqrt {Ri_{b}}f^{*}$

. Because the wall temperature modulation changes the buoyancy within the flow system, we will focus on discussing

![]() $f^{*}$

in the following analysis.

$f^{*}$

in the following analysis.

To determine the Rayleigh number, the time-averaged temperature difference

![]() $\langle {\Delta _T} \rangle _{t}=T_{{hot}}-T_{{cold}}$

is adopted as

$\langle {\Delta _T} \rangle _{t}=T_{{hot}}-T_{{cold}}$

is adopted as

![]() $Ra=g\beta \langle {\Delta _T} \rangle _{t} H^3/(\nu \alpha )$

, and the Rayleigh number is in the range of

$Ra=g\beta \langle {\Delta _T} \rangle _{t} H^3/(\nu \alpha )$

, and the Rayleigh number is in the range of

![]() $10^6 \leqslant Ra \leqslant 10^8$

. We fix the Prandtl number as

$10^6 \leqslant Ra \leqslant 10^8$

. We fix the Prandtl number as

![]() $Pr = 0.71$

for the working fluid of air. The bulk Reynolds number is

$Pr = 0.71$

for the working fluid of air. The bulk Reynolds number is

![]() $Re_b =10^{3.75} \approx 5623$

, and the corresponding friction Reynolds number

$Re_b =10^{3.75} \approx 5623$

, and the corresponding friction Reynolds number

![]() $Re_{\tau }=u_{\tau }h/\nu$

is also provided in table 1, where

$Re_{\tau }=u_{\tau }h/\nu$

is also provided in table 1, where

![]() $u_{\tau }=\sqrt {\langle {\tau _{w}}\rangle /\rho }$

is the friction velocity associated with the mean wall shear stress

$u_{\tau }=\sqrt {\langle {\tau _{w}}\rangle /\rho }$

is the friction velocity associated with the mean wall shear stress

![]() $\langle {\tau _{w}}\rangle$

. We are particularly interested in the mixed convection regime, such that the Richardson number is in the range of

$\langle {\tau _{w}}\rangle$

. We are particularly interested in the mixed convection regime, such that the Richardson number is in the range of

![]() $0.0445 \leqslant Ri_b \leqslant 4.45$

. A list of the bulk flow parameters obtained from all the simulations conducted in this study is provided in table 1, and their relevance to atmospheric currents in desert regions is discussed in appendix B.

$0.0445 \leqslant Ri_b \leqslant 4.45$

. A list of the bulk flow parameters obtained from all the simulations conducted in this study is provided in table 1, and their relevance to atmospheric currents in desert regions is discussed in appendix B.

Table 1. Numerical details of flow quantities. The columns from left to right indicate the following: Rayleigh number

![]() $Ra$

; bulk Richardson number

$Ra$

; bulk Richardson number

![]() $Ri_b$

; wall temperature modulation frequency

$Ri_b$

; wall temperature modulation frequency

![]() $f^{*}$

; friction Reynolds number

$f^{*}$

; friction Reynolds number

![]() $Re_{\tau }$

at the bottom and top wall, respectively, and their relative differences due to asymmetric boundary conditions; grid number

$Re_{\tau }$

at the bottom and top wall, respectively, and their relative differences due to asymmetric boundary conditions; grid number

![]() $N_x \times N_y \times N_z$

.

$N_x \times N_y \times N_z$

.

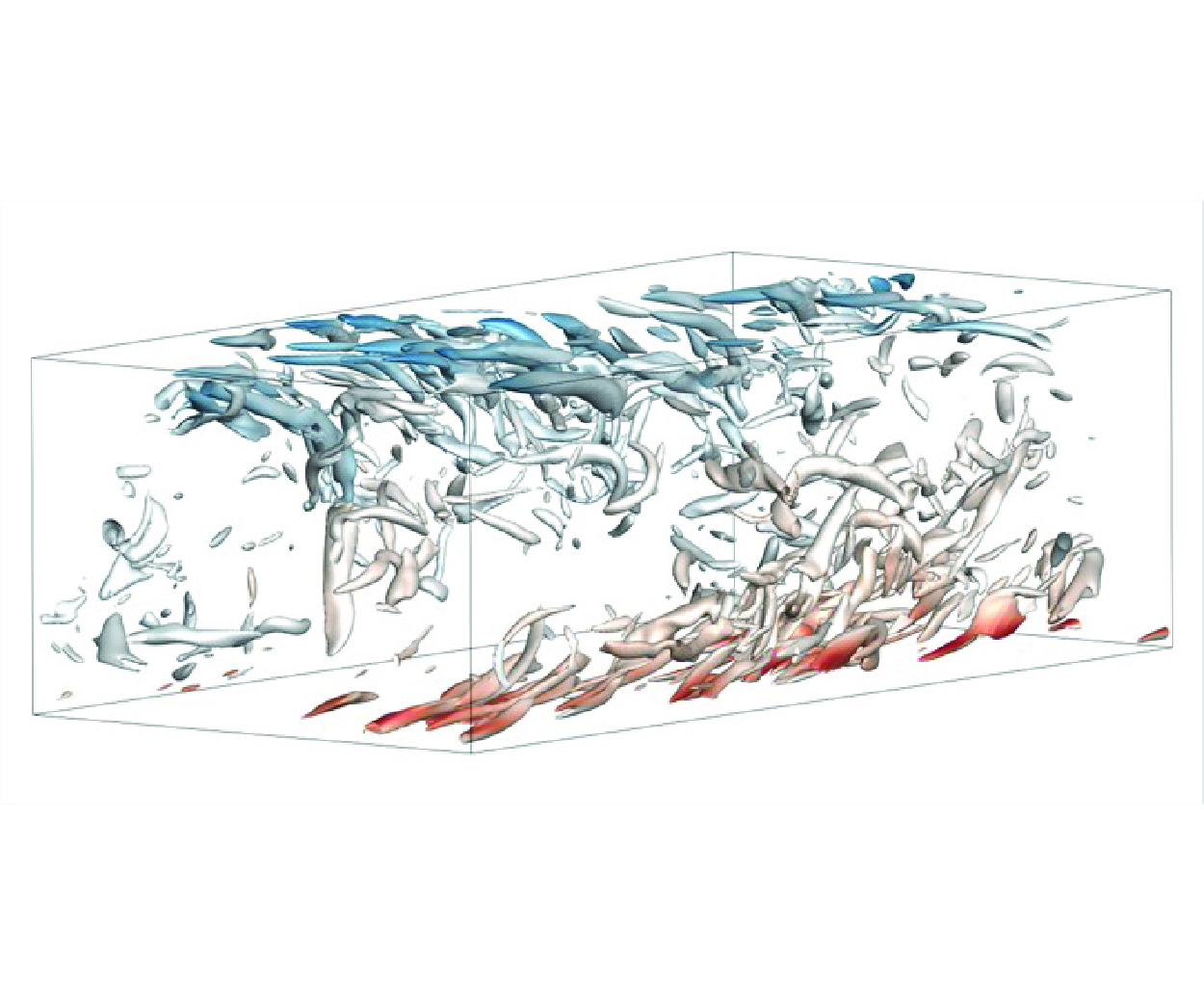

Figure 2. Typical instantaneous isosurfaces of the

![]() $Q$

-criterion,

$Q$

-criterion,

![]() $Q^* = (\|{\boldsymbol{\Omega} }^*\|^2-\|\mathbf {S}^*\|^2 )/2 = 15$

coloured by the local temperature

$Q^* = (\|{\boldsymbol{\Omega} }^*\|^2-\|\mathbf {S}^*\|^2 )/2 = 15$

coloured by the local temperature

![]() $T^*$

, at phase angle (a,b)

$T^*$

, at phase angle (a,b)

![]() $\phi = 0$

, (c,d)

$\phi = 0$

, (c,d)

![]() $\phi = \pi /2$

, (e,f)

$\phi = \pi /2$

, (e,f)

![]() $\phi = \pi$

, (g,h)

$\phi = \pi$

, (g,h)

![]() $\phi = 3\pi /2$

, with frequency (a,c,e,g)

$\phi = 3\pi /2$

, with frequency (a,c,e,g)

![]() $f^* = 1$

, (b,d,f,h)

$f^* = 1$

, (b,d,f,h)

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

, for

$f^* = 0.01$

, for

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

and

$Ra = 10^7$

and

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

.

$Re_b \approx 5623$

.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Instantaneous flow and heat transfer features

In figure 2, we show snapshots of isosurfaces of the

![]() $Q$

-criterion, coloured by the local temperature

$Q$

-criterion, coloured by the local temperature

![]() $T^*$

, and the corresponding video can be viewed in supplementary movie 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2025.22. The

$T^*$

, and the corresponding video can be viewed in supplementary movie 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2025.22. The

![]() $Q$

-criterion visualizes vortices where the magnitude of vorticity

$Q$

-criterion visualizes vortices where the magnitude of vorticity

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\Omega} }=[\nabla \mathbf {u}-(\nabla \mathbf {u})^T]/2$

exceeds the magnitude of the strain rate

${\boldsymbol{\Omega} }=[\nabla \mathbf {u}-(\nabla \mathbf {u})^T]/2$

exceeds the magnitude of the strain rate

![]() $\mathbf {S}=[\nabla \mathbf {u}+(\nabla \mathbf {u})^T]/2$

, making it an effective tool for illustrating vortical structures (Hunt, Wray & Moin Reference Hunt, Wray and Moin1988). At a higher modulation frequency of

$\mathbf {S}=[\nabla \mathbf {u}+(\nabla \mathbf {u})^T]/2$

, making it an effective tool for illustrating vortical structures (Hunt, Wray & Moin Reference Hunt, Wray and Moin1988). At a higher modulation frequency of

![]() $f^* = 1$

(see figure 2

a,c,e,g), the vortex structures are concentrated near the wall and appear relatively unchanged across different phase angles. At a lower modulation frequency of

$f^* = 1$

(see figure 2

a,c,e,g), the vortex structures are concentrated near the wall and appear relatively unchanged across different phase angles. At a lower modulation frequency of

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

(see figure 2

b,d,f,h), the effect of temporal modulation on wall temperature is evident, and the vortex structure exhibits a pronounced temporal evolution. Specifically, an increased number of structures are identified at

$f^* = 0.01$

(see figure 2

b,d,f,h), the effect of temporal modulation on wall temperature is evident, and the vortex structure exhibits a pronounced temporal evolution. Specifically, an increased number of structures are identified at

![]() $\phi = \pi /2$

and

$\phi = \pi /2$

and

![]() $\phi = \pi$

, carried by hot fluids. An interesting observation is that when the wall temperature modulation leads to a stable condition (see figure 2

h), the vortices near the bottom wall almost disappear. The absence of vortex interaction implies that the turbulent flow near the bottom wall is significantly weakened, although vortices still emerge and turbulent flow remains active on the top wall. The slower modulation frequency allows for the development of diverse flow structures and temperature distributions at each phase, indicating the fluid’s ability to adapt to each state of the heating and cooling cycles. In contrast, rapid modulation does not give the fluid enough time to significantly rearrange its structure within one modulation cycle, resulting in a consistent pattern regardless of the phase angle.

$\phi = \pi$

, carried by hot fluids. An interesting observation is that when the wall temperature modulation leads to a stable condition (see figure 2

h), the vortices near the bottom wall almost disappear. The absence of vortex interaction implies that the turbulent flow near the bottom wall is significantly weakened, although vortices still emerge and turbulent flow remains active on the top wall. The slower modulation frequency allows for the development of diverse flow structures and temperature distributions at each phase, indicating the fluid’s ability to adapt to each state of the heating and cooling cycles. In contrast, rapid modulation does not give the fluid enough time to significantly rearrange its structure within one modulation cycle, resulting in a consistent pattern regardless of the phase angle.

Figure 3. Typical instantaneous velocity component

![]() $v^*$

at channel centre plane (

$v^*$

at channel centre plane (

![]() $y = h$

) at phase angle (a,b)

$y = h$

) at phase angle (a,b)

![]() $\phi = 0$

, (c,d)

$\phi = 0$

, (c,d)

![]() $\phi = \pi /2$

, (e,f)

$\phi = \pi /2$

, (e,f)

![]() $\phi = \pi$

, (g,h)

$\phi = \pi$

, (g,h)

![]() $\phi = 3\pi /2$

, with frequency (a,c,e,g)

$\phi = 3\pi /2$

, with frequency (a,c,e,g)

![]() $f^* = 1$

, (b,d,f,h)

$f^* = 1$

, (b,d,f,h)

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

, for

$f^* = 0.01$

, for

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

and

$Ra = 10^7$

and

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

.

$Re_b \approx 5623$

.

Figure 4. Typical instantaneous temperature

![]() $T^*$

in cross-stream plane at phase angle (a,b)

$T^*$

in cross-stream plane at phase angle (a,b)

![]() $\phi = 0$

, (c,d)

$\phi = 0$

, (c,d)

![]() $\phi = \pi /2$

, (e,f)

$\phi = \pi /2$

, (e,f)

![]() $\phi = \pi$

, (g,h)

$\phi = \pi$

, (g,h)

![]() $\phi = 3\pi /2$

, with frequency (a,c,e,g)

$\phi = 3\pi /2$

, with frequency (a,c,e,g)

![]() $f^* = 1$

, (b,d,f,h)

$f^* = 1$

, (b,d,f,h)

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

, for

$f^* = 0.01$

, for

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

and

$Ra = 10^7$

and

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

.

$Re_b \approx 5623$

.

We show the instantaneous velocity component

![]() $v^{*}$

at the channel centre plane (

$v^{*}$

at the channel centre plane (

![]() $y = h$

) in figure 3, corresponding to the instantaneous state presented in figure 2. In convective flow, rising fluids are warmer, and falling fluids are colder; thus, we do not show the corresponding temperature field

$y = h$

) in figure 3, corresponding to the instantaneous state presented in figure 2. In convective flow, rising fluids are warmer, and falling fluids are colder; thus, we do not show the corresponding temperature field

![]() $T^*$

at this plane. However, we have verified that the correlation coefficient between

$T^*$

at this plane. However, we have verified that the correlation coefficient between

![]() $v^*$

and

$v^*$

and

![]() $T^*$

is larger than 0.47. At a Rayleigh number of

$T^*$

is larger than 0.47. At a Rayleigh number of

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

and a bulk Reynolds number of

$Ra = 10^7$

and a bulk Reynolds number of

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

, with a fixed Prandtl number of

$Re_b \approx 5623$

, with a fixed Prandtl number of

![]() $Pr = 0.71$

, the corresponding Richardson number is

$Pr = 0.71$

, the corresponding Richardson number is

![]() $Ri_{b} = 0.45$

. At this intermediate Richardson number, the shear-driven and buoyancy-driven turbulence production rates are nearly balanced. The flow exhibits rolls pointing in the streamwise direction, with a strong meandering behaviour due to the wavy instability of the rolls. This overall trend is similar to that reported by Pirozzoli et al. (Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017). In addition, we found that at a higher modulation frequency of

$Ri_{b} = 0.45$

. At this intermediate Richardson number, the shear-driven and buoyancy-driven turbulence production rates are nearly balanced. The flow exhibits rolls pointing in the streamwise direction, with a strong meandering behaviour due to the wavy instability of the rolls. This overall trend is similar to that reported by Pirozzoli et al. (Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017). In addition, we found that at a higher modulation frequency of

![]() $f^* = 1$

(see figure 3

a,c,e,g), the pair of counter-rotating rolls within the flow domain remains relatively stable in strength. The stability of these rolls demonstrates the flow’s resilience against high-frequency thermal perturbations, suggesting an inherent inertia in the thermal field that resists rapid changes. However, at a lower modulation frequency of

$f^* = 1$

(see figure 3

a,c,e,g), the pair of counter-rotating rolls within the flow domain remains relatively stable in strength. The stability of these rolls demonstrates the flow’s resilience against high-frequency thermal perturbations, suggesting an inherent inertia in the thermal field that resists rapid changes. However, at a lower modulation frequency of

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

(see figure 3

b,d,f,h), the strength of the roll varies with the phase angle. Specifically, the rolls are stronger during the heating phase (

$f^* = 0.01$

(see figure 3

b,d,f,h), the strength of the roll varies with the phase angle. Specifically, the rolls are stronger during the heating phase (

![]() $T_{{bottom}}\gt T_{{hot}}$

); they are much weaker, or even disappear, during the cooling phase (

$T_{{bottom}}\gt T_{{hot}}$

); they are much weaker, or even disappear, during the cooling phase (

![]() $T_{{bottom}}\lt T_{{hot}}$

).

$T_{{bottom}}\lt T_{{hot}}$

).

We show the temperature field

![]() $T^*$

in the cross-stream plane, which complements the velocity contours at the channel centre plane shown in figure 3, and the corresponding video can be viewed in supplementary movie 2. During the heating phase, we observe frequent hot plume emissions near the bottom wall, becoming more pronounced after the wall temperature cycle reaches its peak (see figure 4

e,f). In contrast, during the cooling phase (see figure 4

g,h), plume emissions from the bottom wall are absent due to stable stratification, resulting in the weakening of buoyancy forces. In this stable stratification, internal gravity waves separate the bottom cold part and the top hot part (Zonta et al. Reference Zonta, Sichani and Soldati2022). We also observe the effect of modulation frequency on temperature evolution. At a higher frequency of

$T^*$

in the cross-stream plane, which complements the velocity contours at the channel centre plane shown in figure 3, and the corresponding video can be viewed in supplementary movie 2. During the heating phase, we observe frequent hot plume emissions near the bottom wall, becoming more pronounced after the wall temperature cycle reaches its peak (see figure 4

e,f). In contrast, during the cooling phase (see figure 4

g,h), plume emissions from the bottom wall are absent due to stable stratification, resulting in the weakening of buoyancy forces. In this stable stratification, internal gravity waves separate the bottom cold part and the top hot part (Zonta et al. Reference Zonta, Sichani and Soldati2022). We also observe the effect of modulation frequency on temperature evolution. At a higher frequency of

![]() $f^* = 1$

, the upward- and downward-travelling plumes detaching from the boundary layers are almost unaffected by the phase angle, explaining the relatively stable pair of counter-rotating rolls found in figure 3(a,c,e,g). At a lower frequency of

$f^* = 1$

, the upward- and downward-travelling plumes detaching from the boundary layers are almost unaffected by the phase angle, explaining the relatively stable pair of counter-rotating rolls found in figure 3(a,c,e,g). At a lower frequency of

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

, the slower frequency allows the temperature to respond to changes in the thermal boundaries and adapt to each state of the modulation cycle (see figure 4

b,d,f,h). During the heating phase, hot rising plumes deeply penetrate into the bulk region of the channel. During the cooling phase, a stably stratified layer forms near the bottom wall, acting as a thermal blanket. The overall behaviour mirrors the dynamics observed in atmospheric flow (Dupont & Patton Reference Dupont and Patton2022). After sunrise, the ground heats up, destabilizing atmospheric conditions and forming a mixed layer with a relatively uniform temperature profile due to turbulent mixing. After sunset, the ground cools down more rapidly than the air above it, forming a stable boundary layer close to the surface. This layer sits beneath the remnants of the daytime mixed layer, where turbulence gradually decays in the absence of additional production mechanisms.

$f^* = 0.01$

, the slower frequency allows the temperature to respond to changes in the thermal boundaries and adapt to each state of the modulation cycle (see figure 4

b,d,f,h). During the heating phase, hot rising plumes deeply penetrate into the bulk region of the channel. During the cooling phase, a stably stratified layer forms near the bottom wall, acting as a thermal blanket. The overall behaviour mirrors the dynamics observed in atmospheric flow (Dupont & Patton Reference Dupont and Patton2022). After sunrise, the ground heats up, destabilizing atmospheric conditions and forming a mixed layer with a relatively uniform temperature profile due to turbulent mixing. After sunset, the ground cools down more rapidly than the air above it, forming a stable boundary layer close to the surface. This layer sits beneath the remnants of the daytime mixed layer, where turbulence gradually decays in the absence of additional production mechanisms.

Figure 5. Typical instantaneous vertical convective heat flux

![]() $v^* \delta T^*$

at phase angle (a,b)

$v^* \delta T^*$

at phase angle (a,b)

![]() $\phi$

= 0, (c,d)

$\phi$

= 0, (c,d)

![]() $\phi$

=

$\phi$

=

![]() $\pi$

/2, (e,f)

$\pi$

/2, (e,f)

![]() $\phi$

=

$\phi$

=

![]() $\pi$

, (g,h)

$\pi$

, (g,h)

![]() $\phi$

= 3

$\phi$

= 3

![]() $\pi$

/2, with frequency (a,c,e,g)

$\pi$

/2, with frequency (a,c,e,g)

![]() $f^* = 1$

, (b,d,f,h)

$f^* = 1$

, (b,d,f,h)

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

, for

$f^* = 0.01$

, for

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

and

$Ra = 10^7$

and

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

.

$Re_b \approx 5623$

.

To examine the influence of wall temperature modulation on local heat transfer properties, we show slices of vertical convective heat flux

![]() $v^*\delta T^*$

in figure 5, corresponding to the instantaneous state presented in figure 2. Here, the temperature fluctuation is defined as

$v^*\delta T^*$

in figure 5, corresponding to the instantaneous state presented in figure 2. Here, the temperature fluctuation is defined as

![]() $\delta T^* = T^* - \langle T \rangle _{V,t}$

, and

$\delta T^* = T^* - \langle T \rangle _{V,t}$

, and

![]() $\langle \cdots \rangle _{V,t}$

denotes the average over the whole channel and over the time. At a higher frequency of

$\langle \cdots \rangle _{V,t}$

denotes the average over the whole channel and over the time. At a higher frequency of

![]() $f^* = 1$

(see figure 5

a,c,e,g), positive values of vertical heat flux predominantly appear within the channel, while negative values occur near both the top and bottom walls. This counter-gradient heat transfer is attributed to sweeps of hotter fluid towards the bottom wall and colder fluid towards the top wall. In contrast, at a lower frequency of

$f^* = 1$

(see figure 5

a,c,e,g), positive values of vertical heat flux predominantly appear within the channel, while negative values occur near both the top and bottom walls. This counter-gradient heat transfer is attributed to sweeps of hotter fluid towards the bottom wall and colder fluid towards the top wall. In contrast, at a lower frequency of

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

(see figure 5

b,d,f,h), there is a strong counter-gradient heat flux in the bulk region of the channel, driven by the bulk dynamics of rolls, similar to the mechanism in RB convection (Gasteuil et al. Reference Gasteuil, Shew, Gibert, Chillà, Castaing and Pinton2007; Huang & Zhou Reference Huang and Zhou2013). Detached plumes move with the streamwise-oriented roll, and after reaching the opposite wall, some plumes retain thermal energy and remain hotter or colder than their surroundings. They continue moving with the rolls, resulting in the falling of hot fluid or the rising of cold fluid, thus generating negative vertical heat flux.

$f^* = 0.01$

(see figure 5

b,d,f,h), there is a strong counter-gradient heat flux in the bulk region of the channel, driven by the bulk dynamics of rolls, similar to the mechanism in RB convection (Gasteuil et al. Reference Gasteuil, Shew, Gibert, Chillà, Castaing and Pinton2007; Huang & Zhou Reference Huang and Zhou2013). Detached plumes move with the streamwise-oriented roll, and after reaching the opposite wall, some plumes retain thermal energy and remain hotter or colder than their surroundings. They continue moving with the rolls, resulting in the falling of hot fluid or the rising of cold fluid, thus generating negative vertical heat flux.

We further show the instantaneous streamwise velocity component

![]() $u^*$

at a near-wall station of

$u^*$

at a near-wall station of

![]() $y = 0.05 h$

in figure 6. At a higher modulation frequency of

$y = 0.05 h$

in figure 6. At a higher modulation frequency of

![]() $f^* = 1$

(see figure 6

a,c,e,g), near-wall streaks are observed even in the presence of strong buoyancy. These streaks are often associated with vigorous momentum transfer and robust turbulence production. However, at a lower modulation frequency of

$f^* = 1$

(see figure 6

a,c,e,g), near-wall streaks are observed even in the presence of strong buoyancy. These streaks are often associated with vigorous momentum transfer and robust turbulence production. However, at a lower modulation frequency of

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

(see figure 6

b,d,f,h), during the cooling phase, which leads to stable stratification of the fluid, the near-wall burst-sweep process is completely disrupted (see figure 6

h). This disruption ceases turbulence production and shows tendencies of relaminarization near the bottom wall. During the heating phase, which leads to unstable stratification, the near-wall streaks appear again.

$f^* = 0.01$

(see figure 6

b,d,f,h), during the cooling phase, which leads to stable stratification of the fluid, the near-wall burst-sweep process is completely disrupted (see figure 6

h). This disruption ceases turbulence production and shows tendencies of relaminarization near the bottom wall. During the heating phase, which leads to unstable stratification, the near-wall streaks appear again.

Figure 6. Typical instantaneous velocity component

![]() $u^*$

at near-wall station (

$u^*$

at near-wall station (

![]() $y = 0.05 h$

) at phase angle (a,b)

$y = 0.05 h$

) at phase angle (a,b)

![]() $\phi = 0$

, (c,d)

$\phi = 0$

, (c,d)

![]() $\phi = \pi /2$

, (e,f)

$\phi = \pi /2$

, (e,f)

![]() $\phi = \pi$

, (g,h)

$\phi = \pi$

, (g,h)

![]() $\phi = 3\pi /2$

, with frequency (a,c,e,g)

$\phi = 3\pi /2$

, with frequency (a,c,e,g)

![]() $f^* = 1$

, (b,d,f,h)

$f^* = 1$

, (b,d,f,h)

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

, for

$f^* = 0.01$

, for

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

and

$Ra = 10^7$

and

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

.

$Re_b \approx 5623$

.

Figure 7. (a–c) The second most energetic POD modes, visualizations of isosurfaces of vertical velocity

![]() $v$

(red colour represents

$v$

(red colour represents

![]() $v\gt 0$

and blue colour represents

$v\gt 0$

and blue colour represents

![]() $v\lt 0$

), and (d–f) the cross-correlation functions between bottom wall temperature

$v\lt 0$

), and (d–f) the cross-correlation functions between bottom wall temperature

![]() $T_{{bottom}}(t)$

and POD mode amplitudes

$T_{{bottom}}(t)$

and POD mode amplitudes

![]() $a_2(t)$

as a function of dimensionless lag time

$a_2(t)$

as a function of dimensionless lag time

![]() $\tau /T_{{period}}$

, at modulation frequency of (a,d)

$\tau /T_{{period}}$

, at modulation frequency of (a,d)

![]() $f^* = 1$

, (b,e)

$f^* = 1$

, (b,e)

![]() $f^* = 0.1$

, (c,f)

$f^* = 0.1$

, (c,f)

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

, for

$f^* = 0.01$

, for

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

and

$Ra = 10^7$

and

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

.

$Re_b \approx 5623$

.

To extract the large-scale coherent flow structures, we perform proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) on the turbulent dataset (Berkooz, Holmes & Lumley Reference Berkooz, Holmes and Lumley1993). The POD has been widely employed to study the dynamics of large-scale circulation in convection cells (Podvin & Sergent Reference Podvin and Sergent2015; Castillo-Castellanos et al. Reference Castillo-Castellanos, Sergent, Podvin and Rossi2019; Soucasse et al. Reference Soucasse, Podvin, Rivière and Soufiani2019; Xu, Chen & Xi Reference Xu, Chen and Xi2021). Specifically, the spatiotemporal flow velocity field

![]() $\mathbf {u}(\textbf {x}, t)$

is decomposed into a superposition of empirical orthogonal eigenfunctions

$\mathbf {u}(\textbf {x}, t)$

is decomposed into a superposition of empirical orthogonal eigenfunctions

![]() $\mathbf {\phi }_i(\mathbf {x})$

and their scalar amplitudes

$\mathbf {\phi }_i(\mathbf {x})$

and their scalar amplitudes

![]() $a_i(t)$

as

$a_i(t)$

as

\begin{equation} \mathbf {u}(\mathbf {x},t)=\sum _{i=1}^\infty a_i(t) \mathbf {\phi }_i(\mathbf {x}). \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \mathbf {u}(\mathbf {x},t)=\sum _{i=1}^\infty a_i(t) \mathbf {\phi }_i(\mathbf {x}). \end{equation}

Here,

![]() $\mathbf {u}(\mathbf {x},t)=[u(\mathbf {x},t), v(\mathbf {x},t), w(\mathbf {x},t)]^T$

represents the vector field with components

$\mathbf {u}(\mathbf {x},t)=[u(\mathbf {x},t), v(\mathbf {x},t), w(\mathbf {x},t)]^T$

represents the vector field with components

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $w$

,

$w$

,

![]() $\mathbf {\phi }_{i}(\mathbf {x})=[\phi _{i}^{u}(\mathbf {x}), \phi _{i}^{v}(\mathbf {x}), \phi _{i}^{w}(\mathbf {x})]^T$

represents the spatial eigenfunctions (i.e. the POD modes) and

$\mathbf {\phi }_{i}(\mathbf {x})=[\phi _{i}^{u}(\mathbf {x}), \phi _{i}^{v}(\mathbf {x}), \phi _{i}^{w}(\mathbf {x})]^T$

represents the spatial eigenfunctions (i.e. the POD modes) and

![]() $a_{i}(t)$

are the temporal coefficients representing the time-dependent amplitudes of the corresponding modes. We used at least 900 snapshots to adequately capture the flow structure, ensuring the dominant modes are representative. At parameters of

$a_{i}(t)$

are the temporal coefficients representing the time-dependent amplitudes of the corresponding modes. We used at least 900 snapshots to adequately capture the flow structure, ensuring the dominant modes are representative. At parameters of

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

and

$Ra = 10^7$

and

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

(i.e. the corresponding

$Re_b \approx 5623$

(i.e. the corresponding

![]() $Ri_{b}=0.445$

), we have that the most energetic POD mode corresponds to the streamwise unidirectional shear flow with parallel streamlines pointing along the

$Ri_{b}=0.445$

), we have that the most energetic POD mode corresponds to the streamwise unidirectional shear flow with parallel streamlines pointing along the

![]() $x$

direction. Then, in figure 7(a–c), we present the second most energetic POD modes, which are essentially the dominant mode for the fluctuation velocity field. Regardless of the temporal modulation frequency of the bottom wall temperature, streamwise-oriented rolls that fill the whole channel height are observed. We also examined the time series of mode amplitudes

$x$

direction. Then, in figure 7(a–c), we present the second most energetic POD modes, which are essentially the dominant mode for the fluctuation velocity field. Regardless of the temporal modulation frequency of the bottom wall temperature, streamwise-oriented rolls that fill the whole channel height are observed. We also examined the time series of mode amplitudes

![]() $a_i(t)$

and studied the relationship between wall temperature

$a_i(t)$

and studied the relationship between wall temperature

![]() $T_{{bottom}} (t )=T_{{hot}}+2(T_{{hot}}-T_{{cold}})\sin (2\pi ft)$

and the second POD mode amplitude

$T_{{bottom}} (t )=T_{{hot}}+2(T_{{hot}}-T_{{cold}})\sin (2\pi ft)$

and the second POD mode amplitude

![]() $a_2(t)$

by calculating their cross-correlation functions as

$a_2(t)$

by calculating their cross-correlation functions as

where

![]() $\sigma _{T_{{bottom}}}$

and

$\sigma _{T_{{bottom}}}$

and

![]() $\sigma _{a_2}$

are the standard deviation of

$\sigma _{a_2}$

are the standard deviation of

![]() $T_{{bottom}}$

and

$T_{{bottom}}$

and

![]() $a_2$

, respectively. As shown in figure 7(d–f), at higher modulation frequency of

$a_2$

, respectively. As shown in figure 7(d–f), at higher modulation frequency of

![]() $f^* = 1$

and

$f^* = 1$

and

![]() $f^* = 0.1$

,

$f^* = 0.1$

,

![]() $T_{{bottom}}$

are uncorrelated with

$T_{{bottom}}$

are uncorrelated with

![]() $a_2$

, indicating that the large-scale rolls are not influenced by changes in wall temperature. However, at a lower modulation frequency of

$a_2$

, indicating that the large-scale rolls are not influenced by changes in wall temperature. However, at a lower modulation frequency of

![]() $f^* = 0.01$

, we observe a strong correlation between

$f^* = 0.01$

, we observe a strong correlation between

![]() $T_{{bottom}}$

and

$T_{{bottom}}$

and

![]() $a_2$

, implying that the strength of the large-scale rolls is significantly affected by temperature modulation on the wall. These large-scale rolls are a recognized structural characteristic of atmospheric boundary layers, present in scenarios with mean streamwise flow and exhibiting overall streamwise helical patterns. These patterns are responsible for transporting warmer air towards the capping inversion and cooler air towards the ground (Jayaraman & Brasseur Reference Jayaraman and Brasseur2021).

$a_2$

, implying that the strength of the large-scale rolls is significantly affected by temperature modulation on the wall. These large-scale rolls are a recognized structural characteristic of atmospheric boundary layers, present in scenarios with mean streamwise flow and exhibiting overall streamwise helical patterns. These patterns are responsible for transporting warmer air towards the capping inversion and cooler air towards the ground (Jayaraman & Brasseur Reference Jayaraman and Brasseur2021).

We then computed the energy content of the

![]() $i$

th POD mode

$i$

th POD mode

![]() $\lambda _i$

. In figure 8, we show the spectra of

$\lambda _i$

. In figure 8, we show the spectra of

![]() $\lambda _i$

, where each value of

$\lambda _i$

, where each value of

![]() $\lambda _i$

is normalized by the total energy

$\lambda _i$

is normalized by the total energy

![]() $\sum \lambda _{i}$

. At

$\sum \lambda _{i}$

. At

![]() $Ra = 10^{7}$

, the energy content of the first POD mode

$Ra = 10^{7}$

, the energy content of the first POD mode

![]() $\lambda _1$

dominates, accounting for over 95 % of the total energy and representing the mean flow (streamwise unidirectional shear flow). The energy content of the second and third POD modes

$\lambda _1$

dominates, accounting for over 95 % of the total energy and representing the mean flow (streamwise unidirectional shear flow). The energy content of the second and third POD modes

![]() $\lambda _2$

and

$\lambda _2$

and

![]() $\lambda _3$

each contributes approximately 0.1 %–0.6 % of the total energy. At a higher Rayleigh number of

$\lambda _3$

each contributes approximately 0.1 %–0.6 % of the total energy. At a higher Rayleigh number of

![]() $Ra=10^8$

, with the same bulk Reynolds number of

$Ra=10^8$

, with the same bulk Reynolds number of

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

, the energy contained in the first mode reduces to approximately 80 % due to the enhanced effect of buoyancy, while the second and third modes each contribute around 2 % of the total energy. These results indicate that both the second and third modes play a role in capturing the flow dynamics.

$Re_b \approx 5623$

, the energy contained in the first mode reduces to approximately 80 % due to the enhanced effect of buoyancy, while the second and third modes each contribute around 2 % of the total energy. These results indicate that both the second and third modes play a role in capturing the flow dynamics.

Figure 8. The energy contained in each mode, for (a)

![]() $Ra = 10^{7}$

and (b)

$Ra = 10^{7}$

and (b)

![]() $Ra = 10^{8}$

.

$Ra = 10^{8}$

.

Due to the periodicity in the wall boundary conditions, the streamwise-oriented rolls are non-stationary and continually move along the spanwise direction. To illustrate this, we quantitatively describe the movement of the rolls by tracking their centre. Because the axes of these rolls align with the streamwise direction and do not exhibit the complex motion seen in RB convection (Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Horn, Grannan and Aurnou2018; Li et al. Reference Li, Chen, Xu and Xi2022; Teimurazov et al. Reference Teimurazov, Singh, Su, Eckert, Shishkina and Vogt2023), we can track their edges by identifying locations where the vertical velocity component is minimal or maximal. The centre of each roll is then determined by calculating the arithmetic mean of these points. The POD analysis reveals that not only the second most energetic POD modes but also higher POD modes can represent these rolls. For example, at

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

,

$Ra = 10^7$

,

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

and

$Re_b \approx 5623$

and

![]() $f^* = 0.1$

, both the second and third POD modes correspond to streamwise-oriented rolls, albeit offset along the spanwise direction. Thus, we use both the second and third POD modes to recover the streamwise-oriented roll at

$f^* = 0.1$

, both the second and third POD modes correspond to streamwise-oriented rolls, albeit offset along the spanwise direction. Thus, we use both the second and third POD modes to recover the streamwise-oriented roll at

![]() $f^* = 0.1$

. Figure 9(a) shows the instantaneous recovered flow field at

$f^* = 0.1$

. Figure 9(a) shows the instantaneous recovered flow field at

![]() $x = L/2$

, representing a pair of counter-rotating streamwise-oriented rolls. Here, we mark the edges and centre of one roll to demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach in tracking the roll motion. When the roll centre exits one side of the domain, we account for the domain’s periodicity by wrapping its position to the opposite side, resulting in a continuous trajectory. In figure 9(b), we plot the time series of the centre of this roll along the spanwise direction. The results suggest that the streamwise-oriented roll moves along the spanwise direction, occasionally appearing to exit from one side of the domain and re-enter from the other.

$x = L/2$

, representing a pair of counter-rotating streamwise-oriented rolls. Here, we mark the edges and centre of one roll to demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach in tracking the roll motion. When the roll centre exits one side of the domain, we account for the domain’s periodicity by wrapping its position to the opposite side, resulting in a continuous trajectory. In figure 9(b), we plot the time series of the centre of this roll along the spanwise direction. The results suggest that the streamwise-oriented roll moves along the spanwise direction, occasionally appearing to exit from one side of the domain and re-enter from the other.

Figure 9. (a) Typical instantaneous flow field recovered using the second and third POD modes at

![]() $Ra=10^{7}$

,

$Ra=10^{7}$

,

![]() $Re_{b} \approx 5623$

and

$Re_{b} \approx 5623$

and

![]() $f^*=0.1$

. The contour represents the vertical velocity component, and the arrow represents the velocity field of recovered velocity components. The magenta diamonds mark the edges of the rolls and the blue circles mark the roll centre. (b) The time series of the position of the roll centre.

$f^*=0.1$

. The contour represents the vertical velocity component, and the arrow represents the velocity field of recovered velocity components. The magenta diamonds mark the edges of the rolls and the blue circles mark the roll centre. (b) The time series of the position of the roll centre.

A smaller domain may restrict the formation of large structures due to the imposed periodic boundary conditions and limited spatial extent (Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Hartmann, Verzicco and Lohse2024); thus we conducted additional simulations in a larger domain (

![]() $4\pi h \times 2h \times 2 \pi h$

). In this expanded domain, at

$4\pi h \times 2h \times 2 \pi h$

). In this expanded domain, at

![]() $Ra=10^7$

and

$Ra=10^7$

and

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

(i.e. the corresponding

$Re_b \approx 5623$

(i.e. the corresponding

![]() $Ri_b=0.445$

), we observed two pairs of counter-rotating straight rolls (see figure 10

a), which align with expectations based on domain scaling. In other words, doubling the horizontal extent resulted in two roll pairs, compared with one pair in the smaller domain. We then examined the second POD modes in this large domain at

$Ri_b=0.445$

), we observed two pairs of counter-rotating straight rolls (see figure 10

a), which align with expectations based on domain scaling. In other words, doubling the horizontal extent resulted in two roll pairs, compared with one pair in the smaller domain. We then examined the second POD modes in this large domain at

![]() $Ra=10^8$

and

$Ra=10^8$

and

![]() $Re_b \approx 5623$

(i.e. the corresponding

$Re_b \approx 5623$

(i.e. the corresponding

![]() $Ri_b=4.45$

). As shown in figure 10(b), the isosurfaces reveal variations in the vertical velocity, with alternating regions of upward (positive) and downward (negative) flow. The higher Rayleigh number induces stronger buoyancy forces and increased thermal driving, which leads to the breakdown of coherent rolls into smaller, more chaotic structures. While these structures remain somewhat aligned in the streamwise direction, they appear increasingly fragmented, indicating a transition towards a more convection-dominated state. Accordingly, we refer to these structures at

$Ri_b=4.45$

). As shown in figure 10(b), the isosurfaces reveal variations in the vertical velocity, with alternating regions of upward (positive) and downward (negative) flow. The higher Rayleigh number induces stronger buoyancy forces and increased thermal driving, which leads to the breakdown of coherent rolls into smaller, more chaotic structures. While these structures remain somewhat aligned in the streamwise direction, they appear increasingly fragmented, indicating a transition towards a more convection-dominated state. Accordingly, we refer to these structures at

![]() $Ra = 10^8$

as fragmented streamwise-oriented rolls.

$Ra = 10^8$

as fragmented streamwise-oriented rolls.

Figure 10. The second POD mode in a domain size of

![]() $4\pi h \times 2 h \times 2 \pi h$

, visualizations of isosurfaces of vertical velocity (red colour represents

$4\pi h \times 2 h \times 2 \pi h$

, visualizations of isosurfaces of vertical velocity (red colour represents

![]() $v\gt 0$

and blue colour represents

$v\gt 0$

and blue colour represents

![]() $v\lt 0$

) at (a)

$v\lt 0$

) at (a)

![]() $Ra = 10^{7}$

, (b)

$Ra = 10^{7}$

, (b)

![]() $Ra = 10^{8}$

, with

$Ra = 10^{8}$

, with

![]() $f^* = 0.1$

.

$f^* = 0.1$

.

3.2. Long-time-averaged statistics

Figure 11. (a) Friction coefficient, (b) values of

![]() $C_f/C_{f0}-1$

, (c) Nusselt number and (d) values of

$C_f/C_{f0}-1$

, (c) Nusselt number and (d) values of

![]() $Nu/Nu_0-1$

, as functions of

$Nu/Nu_0-1$

, as functions of

![]() $f^*$

for various

$f^*$

for various

![]() $Ra$

. Here,

$Ra$

. Here,

![]() $C_{f0}$

and

$C_{f0}$

and

![]() $Nu_0$

are the friction coefficient and Nusselt numbers without wall temperature modulation, respectively.

$Nu_0$

are the friction coefficient and Nusselt numbers without wall temperature modulation, respectively.

To study changes induced on the mean flow and temperature by the wall temperature modulation, we now focus on the long-time-averaged statistics. In figure 11, we present statistics of aerodynamic drag and heat transfer as a function of modulation frequency for various Rayleigh numbers, which is a topic of interest in meteorology and engineering (Yerragolam et al. Reference Yerragolam, Verzicco, Lohse and Stevens2022, Reference Yerragolam, Howland, Stevens, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2024). In figure 11(a), we examine the aerodynamic drag in terms of friction coefficients (

![]() $C_f$

) at the bottom wall, which is calculated as

$C_f$

) at the bottom wall, which is calculated as

![]() $C_f=2\langle \tau _w \rangle /(\rho u_b^2)$

. The increased drag due to the emission of plumes in thermal field is consistent with that reported by Scagliarini et al. (Reference Scagliarini, Einarsson, Gylfason and Toschi2015), Pirozzoli et al. (Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017) and Howland et al. (Reference Howland, Yerragolam, Verzicco and Lohse2024). With wall temperature modulation, we observe that aerodynamic drag is not very sensitive to the wall temperature modulation frequency. Figure 11(b) further visualizes the relative changes of

$C_f=2\langle \tau _w \rangle /(\rho u_b^2)$

. The increased drag due to the emission of plumes in thermal field is consistent with that reported by Scagliarini et al. (Reference Scagliarini, Einarsson, Gylfason and Toschi2015), Pirozzoli et al. (Reference Pirozzoli, Bernardini, Verzicco and Orlandi2017) and Howland et al. (Reference Howland, Yerragolam, Verzicco and Lohse2024). With wall temperature modulation, we observe that aerodynamic drag is not very sensitive to the wall temperature modulation frequency. Figure 11(b) further visualizes the relative changes of

![]() $C_f$

with wall temperature modulation, showing that the variation in

$C_f$

with wall temperature modulation, showing that the variation in

![]() $C_f$

is less than 15 %. In figure 11(c), we examine the heat transfer efficiency in terms of the Nusselt number (

$C_f$

is less than 15 %. In figure 11(c), we examine the heat transfer efficiency in terms of the Nusselt number (

![]() $Nu$

), which is calculated as

$Nu$

), which is calculated as

![]() $Nu=\sqrt {RaPr/Ri_{b}} \langle v^* T^* \rangle _{V,t}+1$

. The

$Nu=\sqrt {RaPr/Ri_{b}} \langle v^* T^* \rangle _{V,t}+1$

. The

![]() $Nu$

at the highest modulation frequency is the same as that without wall temperature modulation. With the decrease in modulation frequency, we observe enhanced heat transfer efficiency for all Rayleigh numbers. Previously, in pure RB convection, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Chong, Wang, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2020) reported a regime where the modulation is too fast to affect

$Nu$

at the highest modulation frequency is the same as that without wall temperature modulation. With the decrease in modulation frequency, we observe enhanced heat transfer efficiency for all Rayleigh numbers. Previously, in pure RB convection, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Chong, Wang, Verzicco, Shishkina and Lohse2020) reported a regime where the modulation is too fast to affect

![]() $Nu$

, a regime where

$Nu$

, a regime where

![]() $Nu$

increases with decreasing

$Nu$

increases with decreasing

![]() $f^*$

and a regime where

$f^*$

and a regime where

![]() $Nu$

decreases with further decreasing

$Nu$

decreases with further decreasing

![]() $f^*$

. Our results in mixed PRB convection cover the first two regimes reported in pure RB convection, yet we did not further explore slower frequency due to the high computational cost in the 3-D simulation. Figure 11(d) further visualizes that among the three Rayleigh numbers,

$f^*$