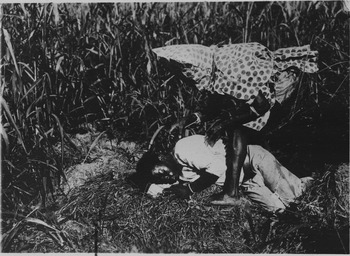

In 1911, the governor of Orientale Province of Belgian Congo, Charles Delhaise, sent a complete ‘anioto’ costume to the Congo Museum, now the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA), in Tervuren, Belgium (Fig. 1). Delhaise reported that anioto dressed up as leopards and killed their victims at night, cutting the carotid artery with their iron claws and leaving leopard paw prints next to the bodies.Footnote 1 Delhaise's mise-en-scène photographs inspired the making of a sculpture, dressed with the objects. It has occupied a central place in the museum since 1915 (Fig. 2).Footnote 2 At that time, administrators in the colony dismissed the reported killings as leopard attacks and local superstitions.Footnote 3

Fig. 1. Anioto ready to attack, mise-en-scène, Bali population, Congo. Photo by Charles Delhaise, 1909 © Royal Museum for Central Africa (RCMA), AP.0.1.6554.

Fig. 2. The leopard-man of Stanley Falls by Paul Wissaert, 1915. Plaster figure, decorated with ethnographic objects. RMCA A.371, photographer unknown; all rights reserved.

In the late 1920s, a more coordinated and sustained administrative and legal attention culminated in several high-profile trials. The discourse developing in the 1920s and 1930s in colonial journals and fiction upheld a stereotype of leopard-men as evil, animal-like creatures threatening the colonial order, in line with the sculpture's iconography.Footnote 4 In reality, leopard-men never wore such costumes for killing, and often committed murders with knives instead of claws.Footnote 5 Yet, the image helped to legitimize the way the colonial administration dealt with leopard-men as a criminal ‘secret society’ or ‘sect’. Although the trials revealed the complex nature and purposes of the killings, these data did not affect published reports. In the 1990s, critiques of demeaning leopard-men representations targeted colonial literature and the museum display, but did not question their historical foundations.Footnote 6 The leopard-men's reputation as being elusive continued, possibly facilitated by a postcolonial taboo on researching violence committed by the colonized, or by the widespread assumption that first-hand reports of the killings could not be retraced.

The main focus of this article is the Bali leopard-men, known as anioto, from whom the sculpture's costume originated, and who also appeared among neighbouring Ndaka and Budu. The Bali and their neighbours belonged to a population of Bantu speakers who had migrated from the north, pushed southward by the expanding Azande and Mangbetu populations. For comparative purposes, I look at a related leopard-man variety, named vihokohoko, occurring among the Bapakombe and Nande to the southeast. The Bapakombe were a small population located to the northwest of Beni on the verge of the rainforest. While the colonial administration considered them as the vanguards of the Nande in the latter's migration from the eastern Great Lakes region, the Bapakombe were culturally more related to western Bantu-speaking forest populations to their north, like the Bali and Ndaka.Footnote 7 Except for the Nande, these populations were organized as segmentary societies; their sociopolitical cohesion consisted in boys’ initiation networks – called mambela among the Bali and Ndaka – and lusomba among the Bapakombe and Nande, which promoted collaboration between villages.Footnote 8

Going against the dominant tendency to treat leopard-men killings as an outcome of the colonial context, I argue that leopard-men were ritually-empowered armed groups, rooted in precolonial traditions, which adapted to diverse political and socioeconomic circumstances throughout time. The article proceeds as follows. After discussing the study's main conceptual and methodological approach, a discussion of adjudicated cases from the colonial era will reveal leopard-men as a fluid phenomenon driven by human adaptability. Subsequently, different regional and temporal manifestations of leopard-men will be discussed, thereby looking at processes of institutional adaptation in a wider historical framework. Finally, similarities between leopard-men cases and contemporary armed groups will be assessed to demonstrate the importance of historical conflict research for the investigation of recent conflicts (and vice versa).

APPROACHES TO LEOPARD-MEN

This article diverges from the usual method of comparison between regional varieties of leopard-men, which considers their activities as a function of the colonial context. Instead, a more profound regional contextualization is favoured, embedding leopard-men from Congo in local institutional networks. Since the colonial period, and predominantly in the 1950s, the tendency to adopt insights between studies of leopard-men varieties across Africa helped leopard-men to become a cross-colonial epistemological category, guiding colonial actions.Footnote 9 Present-day researchers are still tempted to compare between and adopt insights from regional leopard-men varieties, based on similarities in the modus operandi, motives, and the colonial backgrounds of the killings. In this way, similarities are favoured to the detriment of complex differences, due to the unequal knowledge of the killings, contexts, and timeframes. Additionally, the characterizations of leopard-men as a ‘secret society’ further determined the perception of the phenomenon in moral terms.

Across colonies the term ‘secret societies’ lumped together diverse institutions ranging from boys’ initiations to African revivalist churches, which colonial governments often distrusted, since their secret or esoteric aspects escaped colonial control.Footnote 10 As a consequence, among the Bali and their neighbours, institutions such as boys’ initiation networks suffered from criminalization despite being an essential basis of the sociopolitical organization of these segmentary societies.Footnote 11 The incorporation of these societies into the centripetal system of indirect rule was challenging, provoking social tensions and a higher incidence of leopard-men killings. The latter came to symbolize the rebellious and uncivilized nature of the populations, who thereby attracted less research compared to surrounding kingdoms.Footnote 12 This poor reputation of the region persisted as it brought forth repeated colonial and postcolonial insurgencies entailing ritually-inspired armed mobilization (for example, in kitawala, Simba, Mai-Mai). Instead of engaging with the comparative trend, I focus on the local embeddedness of leopard-men in segmentary societies, to remedy blind spots in the region's political history, and to better contextualize leopard-men conflicts, historically and culturally. The similarities with ritually-empowered militias in more recent history are a motivating factor for considering Congo leopard-men in this way, since they make one wonder to what extent past institutional dynamics set the scene for later political developments.Footnote 13

In contemporary leopard-men studies, focusing on different geographical areas and timeframes, the dominant perception is that the killings arise from social tensions under colonialism due to changes in intergenerational, gender, and master-slave relations.Footnote 14 This is the case in David Pratten's study of human-leopard killings among the Annang in southern Nigeria in the 1940s. Pratten treats the killings as an outcome of multi-layered social cleavages revealing the ‘fault-lines’ of colonialism.Footnote 15 Characteristic of his approach is a reluctance to formulate clear hypotheses on the role of the killings in society, providing instead lengthy descriptions of the colonial context and of diverging hypotheses in the colonial investigations. Pratten leaves finding the link between the social cleavages and the murders up to the reader, an approach reviewers find both refreshing and disturbing.Footnote 16 The author's reluctance to discuss the motives of the murders more closely renders them incidental to the social history described. The underlying problem may be a limited access to documents revealing the point of view of victims and perpetrators, which might have enabled the author to assess the role of the killings in society more concretely. The evidence from Belgian Congo shows first that judicial documents are crucial for retrieving the purposes of the killings and second that these purposes shifted between timeframes and transcended the colonial context.

Early Congolese records display a specific though indirect anticolonial character in the choice of victims, who were often cooks, interpreters, and soldiers accompanying European expeditions.Footnote 17 The political relevance of leopard-men in both anticolonial opposition and internecine wars was first highlighted by Allen Roberts, who dismisses colonial perceptions of the killings as irrational.Footnote 18 Jan Vansina briefly mentions the practice of anioto as one development in a spiral of institutional innovations, predating colonialism; he defines anioto as a kind of ‘terrorist murder’ commanded by village chiefs and as an efficient strategy to maintain control over land, people, and resources.Footnote 19 In sum, diverse occurrences of leopard-men killings invite one to consider them in a broader perspective, not necessarily as related to colonialism, but as entangled in local institutional networks and responsive to various situations.

The approach I take builds further on Vansina's consideration of leopard-men as part of a cascade of institutional innovations by introducing the concept of ‘institutional dynamism’. This concept captures the process underpinning the appearance, spread, and adaptation of leopard-men to various circumstances. ‘Institutional dynamism’ involves borrowing titles, rites, beliefs, and medicines from neighbours and merging them with pre-existing ones. Past studies of sociopolitical institutions in this region often illustrated the result of ‘institutional dynamism’ implicitly.Footnote 20 If Vansina describes such processes from a macro-historical perspective, I want to illustrate this process in a bottom-up manner, starting with a micro-historical focus on leopard-men conflicts. In the over-arching theoretical approach, the concept of ‘institutional dynamism’ helps one to see institutions as temporary results of co-structuration in situations of culture contact: micro-historical events bring about macro-historical changes, giving rise to institutional networks stretching across space and time. Inherited scholarly categorizations that consider institutions as either political or religious, or as confined within ethnicities, can hence be disregarded. Additionally, the focus is on emic cultural logic of leopard-men, considering them as more than an outcome of the colonial context.

The cultural logic reflected in leopard-men activities resides on the common ground between leadership notions, on the one hand, and social therapeutics, on the other. Leadership requires an exceptional supernatural talent that can be used to the benefit or detriment of people. Like a leopard, a chief will viciously strike in hidden ways those challenging his authority. Leopard skin and teeth, given as tributes, figure prominently in chiefly dress as visual expressions of authority. Leopard spots refer to the ability to move between two worlds, of spirits and men, of the living and the dead, and evoke the occult and violent aspects of leadership. Powerful men are widely believed to transform into leopards or to control leopards to attack people.Footnote 21 Leopard-men killings need to be understood in connection with these leadership notions. This relates to social therapeutics. A leader's power is reflected in his ability to protect his people and to use violence to restore social ills, as entangled with a broader cultural ‘quest for therapy’.Footnote 22 In the colonial context, the occurrence of waves of leopard-men killings can be interpreted as a manifestation of ‘therapeutic insurgency’ as recently discussed by Nancy Hunt.Footnote 23 In my view, such ‘insurgencies’ are variations of what John Janzen called ‘collective therapies’, which were important vectors of change in the political history of Central, East, and South Africa. Rooted in precolonial times, such therapies evolved around natural or ancestral charms called upon for protection and healing to safeguard community wellbeing, and to attack those who threatened it. The ritual authority emanating from collective therapies influenced politics, helping to consolidate or contest the authority of chiefs or colonial authorities and to exercise state functions in times of chaos. The quest for healing was innate to these collective therapies and an important booster for institutional dynamism, particularly in times of social crisis. Starting as volatile movements, institutionalization of collective therapies occurred differently in different social settings. The leaders were, for instance, absorbed in dualities of power with political leaders, as guardians of ritual power, but collective therapies also manifested themselves as counter-hegemonic, framed as subversive ‘secret societies’.Footnote 24 Furthermore, violence could have a cleansing, therapeutic role in these movements as a means for the recovery and regeneration of society, as pointed out by Hunt and Eggers.Footnote 25 I will demonstrate that such therapeutics were at play in leopard-men killings.

With regards to methodology, my approach to the sources derives from historians such as Stoler and Hunt highlighting the importance of documents reflecting how individuals attempt to shape their world on a micro-historical level, through a process of trial and error.Footnote 26 Secondary colonial journals and fiction demonstrating advanced stereotyping of leopard-men as anonymous, animal-like beings inform this article less directly, as a historical negative, or how not to understand leopard-men.Footnote 27 Instead the focus is on primary records in colonial archives usually produced by colonial personnel. At first it was unclear whether judicial documents providing emic perspectives were available at all, and if so, whether I could gain access, given the protection of judicial records by Belgian privacy law for 100 years. I first studied more accessible administrative and ethnographic reports in the General Government archives of Belgian Congo. Such documents only distantly reflect local voices, but they provided insights into how colonial agents used stereotypes, rumours, and thick description and balanced different hypotheses, which helped to better understand the colonial background.Footnote 28 Such records demonstrate, for instance, disagreements among colonial administrators in their implementation of intermediary rule trying to disentangle institutions that were historically entwined through processes of institutional dynamism. While often speculative these documents also contain firm bits of information such as names, dates, and locations that enabled me to outline several conflict clusters, identify the major chiefs and population groups, and situate them in space and time. These insights helped to retrace the corresponding judicial files.

Access to judicial files was gained by obtaining a special clearance.Footnote 29 The interrogations noted in question-and-answer format come close to primary statements, even if interpreters translated statements from Kibali into Swahili (Kingwana), which were then transcribed in French. The official logs reveal, for instance, how the accused attempt to deny their involvement until, under pressure from their interrogators or fellow-accused, they confess. The accused describe their motives and actions in quite a factual manner, not mentioning costumes or shapeshifting beliefs, which differs from how their modus operandi is presented in local rumours and in secondary reports. The testimonies of accused and witnesses stimulate a nuanced understanding of leopard-men killings in which violence is purposeful rather than random, even if victims are arbitrarily chosen. If the study of such idiosyncratic documents entails the risk of approaching history in an arbitrary and patchy manner, these sources do reflect proximity, human adaptability, and cultural logic, providing a glimpse into the arenas in which individuals and their support groups vied for power.Footnote 30 Contextualizing the conflict cases from these documents in a broader, diachronic perspective helps to demonstrate how leopard-men responded to diverse existential preoccupations over time. Such a contextualization also helps to hypothesize on leopard-men precedents in the precolonial era and to further explore the dialectic and amalgamating nature of institutional dynamism on a macro-historical level. Additional sources are the ethnographic objects supposedly used for the killings, and recent interviews with people from the region, which demonstrate that leopard-men are remembered differently and in some ways better than among academics and the Congolese diaspora.

MICRO-HISTORIES OF CONFLICTS UNDER COLONIAL RULE

Records from leopard-men investigations and trials in the 1920s and 1930s give insight into what leopard-men were, how they were connected to other institutions, and how they adapted to colonial circumstances. After the first trial in 1920, the investigating officers still experienced difficulties in resolving the cases due to the secrecy and silence by those affected, which led to changes in approach and more trials around 1930.Footnote 31 Older cases were reopened and combined with new interrogations of witnesses and suspects, enabling investigators to establish links between old and recent conflicts.Footnote 32 Each of the conflict clusters elicited from these documents is very complex and different, and neither provides a straightforward illustration of the role of leopard-men. While the adjudicated cases represent only the tip of the iceberg, they provide unique documents for the study of leopard-men killings under colonialism. For pragmatic reasons, I will focus on one conflict cluster among the eastern Bali around 1930, referring to other cases for discussing general conflict patterns and dynamics. Bali and Ndaka chiefs lent out leopard-men gangs to their Budu neighbours. I will use court hearings of two specific conflicts in this cluster, initiated by chief Mbako and the notable Bangombe, to illustrate the role of leopard-men killings under colonialism.

THE INSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT UNDER PRESSURE

Intermediary chieftaincy under colonial rule was commonly based on lineage leadership and granted to the eldest lineage of the first occupants of the land. However, in the segmentary societies discussed here hierarchies of lineage chiefs (metundji) never exceeded the village level and had become over-arched by the mambela initiation network. Each village had at least one mambela leader (tata ka mambela) who acknowledged a loose hierarchy based on the original pathways of spreading of mambela along villages. Within the village, the tata ka mambela entertained a duality of power with one or more ishumu, with the latter representing the lineages at the heart of the mambela organization. The ishumu’s position, based on ancestry, provided him with ritual authority.Footnote 33 The multi-layered authorities caused confusion among administrators about who represented supreme authority. Candidacies for indirect rule were complicated further by powerbrokers who had emerged from contacts with slave traders and colonizers, like the strawmen put to the fore by chiefs reluctant to deal with the colonizers themselves. Their descendants claimed leadership in later decades. Others descended from local slave-trading leaders preferred as intermediaries in the Congo Free State era.Footnote 34 The court cases discussed have to be seen against this light.

Mbako had been a chef médaillé, or chief appointed by the colonial government, but was deposed based on his suspected involvement in earlier killings. He was eventually convicted for sending leopard-men to the Budu chiefdom of Karume on request of his daughter's in-laws. Mbako's trial, culminating in a public hanging in 1935, garnered the most attention in colonial and missionary publications.Footnote 35 The court hearings shed light on the role of mambela leaders in the killings, but also show the erosion of their authority under colonial rule. Mbako declared the following in court:

Q: We learn, Mbako, that anioto crimes are always the result of a decision taken by the ishumu united in council at the closure of the mambela initiation. Is this true?

A: Yes, that is perfectly correct.

Q: How were the crimes in the territory of Karume decided upon?

A: Sengi, the father of Basibane, my daughter's husband, sent emissaries to me to state his resentment of the Babasane [Budu lineage] of Karume, who were behind the condemnation and imprisonment of my son-in-law. I, who am not ishumu and in fact only chief of the Bafwambanzo [Bali lineage] in the eyes of the whites, exposed the case to Bakeboi, one of the little ishumu of a fraction of the Bafwamagaü [Bali lineage]. I asked him to bring the matter before the council of the mambela, to request the intervention of the anioto of all the clans of the group obeying Dungba [Dungbele, tata ka mambela], our great chief who lives in the village … named ‘Bomili’. Bakeboi, having obtained the agreement in principle from the other little ishumu, took action, and thus the ceremonies of the Maduali [the final phase of mambela] took place, followed by the reunion of ishumu, medio 1932. At this meeting the expedition culminating in the killings of the Budu of Karume was decided upon.

Q: Did all the ishumu present agree?

A: Yes, the agreement to avenge the harm done to Basibane by the people of Karume was unanimous.

…

Q: If, however, you had undertaken the avenging expedition on your own initiative, overruling the decision of the mambela council, what would have happened?

A: At the next meeting of the mambela I would have had a big palaver. As I am a nobleman, I would have got off with a big fine to pay in kind.

Q: And if one who disregards the decisions of the mambela is a mere mortal?

A: Ah, then the mambela decides he has to die and the ishumu of his clan has to take care of it … He will search for him, wait for the right moment and kill him without any other trial.Footnote 36

The aforementioned paramount mambela leader Dungbele sheds another light on the matter:

Q: Before the arrival of the Europeans, who were the leaders among the Bali?

A: We, the tata ka mambela, and the ishumu were the top men.

Q: And nowadays in the eyes of the natives, are you the true chiefs, while those known as chiefs are in reality only the intermediaries of the tata ka mambela in the interactions with Europeans.

A: Certainly.

Q: So it's obvious that an important decision to introduce war to the Budu could not be taken without Mbako having received the prior agreement of the ishumu, the true customary leaders?

A: What you say of ishumu’s being the true customary rulers is absolutely right, but in this case, I do not think Mbako consulted anyone.

Q: Before the arrival of the Europeans, Mbako could have introduced war without consulting the ishumu and the tata ka mambela?

A: No, before, it required the consent of the ishumu and the tata ka mambela.

Q: But then, did Mbako do right by not consulting with the ishumu for this last expedition?

A: No, and customarily it is highly blameworthy.Footnote 37

Confronted with Dungbele, Mbako admitted he did not consult the mambela council, but only with a few notables. As Dungbele noted, the authority of the tata ka mambela and ishumu was eroding under colonial administration. Mbako challenged these authorities by pretending they were responsible for approving the killings, downplaying his own responsibility. In discussions about who was to be held responsible for the leopard-men killings, fingers were easily pointed in the direction of mambela. The colonial administration distrusted mambela for holding a strong moral grip over the population and evading colonial control, which made some administrators argue for the ‘restoration’ of metundji lineage chiefs for indirect rule.Footnote 38 Indirect rule had put customary chiefs in an awkward position in which they were civil servants forced to fulfil tasks contrary to the interest of their subjects, while their contenders capitalized on their challenges. This pushed them to equally use means such as leopard-men killings to hold on to their position and keep their rivals at bay.Footnote 39 Such dynamics appear in another trial, in a case in which the Budu nobleman Bangombe requested anioto from the Bali chief Mbako. Mbako referred him to another man named Mabiama, an ishumu of another Bali family. Bangombe declared the following in court:

Q: In 1928 you went to Mabiama [ishumu] to ask for anioto, because your subjects did not want you as a leader.

A: Chief Wangata being dead, I was summoned by a white state official together with the two children of Wangata. This European told me that, as the two sons of Wangata were too young, I had to exercise the tutelage and replace Wangata. Returning home, I reported this situation, but nobody in the village wanted me as chief, although my father Apanzaku had been such in the time of the ‘Arabisés’.

Q: Why? Was your father a bad man or were the natives afraid of you?

A: The natives did not want me. At the time a white man named Bwana Ndeke [Josué Henry de la Lindi, who led military operations under the Congo Free State], had given my father a note stating that he was to be chief. When my father returned to the village, Wangata had him put in prison and took this note. When other Europeans came, they asked for the note given to him by Bwana Ndeke. My father had lost it. Since then my father was no longer a chief. Wangata wanted his son Naganea to be his successor, and the notables made this inscription in Wangata's libretto [record book] in order not to admit me as their leader.

Q: Who was the real chief of the region before the arrival of the Arabs?

A: It was Bala … the brother of Wangata.Footnote 40

Bangombe's reference to Josué Henry de la Lindi identifies him as a descendant of the first middlemen engaged in military expeditions and rubber tax collection in the Congo Free State. In the region discussed, Henry de la Lindi won battles by convincing local leaders of slave-trading communities to fight on his side. They continued to be favoured as intermediaries during the first decades of colonization as they spoke Swahili and were considered easier to work with.Footnote 41 The administration's changing preferences for intermediaries, combined with the investiture and destitution of chiefs on ill-informed, subjective grounds, upset historically-rooted power relations, fuelling pre-existing tensions. Men like Bangombe saw their descent as a pretext to make claims once again, but were disliked due to their family's collaborations with slave traders and colonizers. Bangombe himself, displeased with the unsupportive behaviour of the people from his village, sent in the leopard-men.

From the court hearings we can infer that leopard-men violence proliferated under colonialism and tended to escape the control of the mambela council. We learn it was not strictly used to oppose colonial rule, but more pragmatically, to put pressure on rivals, to circumvent control by keeping the killings secret, and to sow confusion among those investigating the killings. Anioto’s usefulness to remain in charge as best as possible under the given circumstances inspired its adoption by different powerbrokers. While such a process characterized institutional dynamism, it also caused cyclical retaliations manifesting themselves in a higher incidence of killings in the colonial era. This kind of proliferation of armed groups and violence in situations of social crisis, in which systems of governance are dysfunctional, reminds one of the proliferations of community militias in recent warfare.Footnote 42

THE GROWING NETWORK

Leopard-men killings were a strategy in armed conflict that could be used whenever a commotion occurred. Among the Bali, every important man had his own gang, but the approval of the mambela council was required to carry out killings. The reasons for conflicts are in line with notions of leadership. From oral tradition we learn that senior Bali clans first used anioto to monopolize access to land and resources, to control people and exact tribute from them.Footnote 43 Leopard-men killings were committed whenever a leader's authority and his privileges were under pressure, bringing about internecine conflicts and waves of leopard-men killings in the colonial era. Conflicts evolved around succession struggles and contests over land or revenue among those claiming to be the legitimate possessors of such rights whether as first-born representatives of a senior lineage or as first occupants of the land. Killings were used to discredit potential rivals and to discourage people from collaborating with colonial authorities and report the killings. Another important factor in conflicts was wealth in people, or the ability to amass dependants for labour or for marriage exchanges to create social ties with other groups. Therefore, conflicts often arose over people lost in warfare, whose deaths were not appropriately compensated, but also over forced relocations for labour duties, unpaid bride prices, runaway wives, and control over their children. The fact that vengeance was taken for the imprisonment of Mbako's son-in-law is another example. The principle of wealth in people also accounts for the fact that leopard-men randomly targeted easy victims within a collectivity, such as children, and not specific individuals. Conflicts were usually of a collective nature, connected to leaders’ responsibilities and privileges, even though the collective aspect tied in with individual ambitions or grudges. Attacks mostly targeted outsiders, but chiefs also used the terror of leopard-men against their own people to imprint their authority and punish them for not paying due respect, as in Bangombe's case.

Among the Bali, anioto skills were passed on from father to son, from maternal uncle to nephew. Marital relations through wife exchanges created a network via which anioto were requested from neighbours. Another basis for passing on anioto skills was an alliance created through the exchange of mambela initiates, a practice known as samba.Footnote 44 In Bali society the spreading of anioto had been going on for several generations and in the colonial era this society had become saturated with leopard-men-owning families. The cases discussed here demonstrate that Budu neighbours came to request leopard-men among the Bali based on pre-existing marital ties between families. Bangombe was, for instance, introduced to chief Mbako by his nephew, who married a relative of Mbako. Mbako referred him to Mabiama:Footnote 45

Q: How did you explain your visit to Mabiama [ishumu]?

A: I brought him oil and fabrics and said I wanted him to ‘introduce a war’ in my home village. Mabiama replied: ‘Fine, return, I will send my anioto later on, because if I do it upon your return, everybody will know that you ordered them.’

Q: Initially, did you not ask Mabiama for a medicine [dawa] to kill people in your home village?

A: Yes, I asked for a drug first, but Mabiama replied that he did not have any. That he had only anioto.

Q: What did you do during your stay in the village of Mabiama?

A: We stayed four days doing nothing. On the fifth day, the circumcisions were made, and the seventh we returned.

Q: Who was circumcised? …

A: Three children, two Bali and one Budu.

…

Q: Why did you use circumcision for this alliance, when the Bali do not know circumcision and their customary way of making an alliance is the exchange of blood?

A: I never asked him [Mabiama]. The way of us Budu to conclude an alliance is to perform the circumcision of our children.

…

Q: … Why was your wife killed in the first place?

A: I agreed with Mabiama that the anioto coming to my home had to kill one of my people first, to make people believe I was not responsible for summoning them.Footnote 46

Rules were possibly stricter when Bali men lent leopard-men to outsiders. Budu neighbours, for instance, had to sacrifice a relative first.Footnote 47 Additionally, an alliance was formed through the joint circumcision of two Bali and one Budu boy at Mabiama's residence in analogy to the exchange of mambela initiates among the Bali. The social networks created in this way promoted collaboration between leopard-men owners over long distances. Leopard-men owners would send their gang, or act as intermediaries to request gangs from associates further away. Mbako played such an intermediary role in Bangombe's case. These gangs coming from another region committed the killings themselves, or trained subjects of the requesting person, who would from thereafter possess his own gang. The fact that gangs came from elsewhere and travelled discreetly, for example via forest trails instead of the principal roads, prevented them from being recognized, which complicated the investigations.Footnote 48 Among the eastern Bali, the intricate network of leopard-men owners inspired them to express mutual accusations whenever they were suspected, even among allies. This strategy worked quite well initially, but became obsolete as the colonial administration became better organized in investigating the killings.

To clarify how such networks operated, a sustained comparison with contemporary armed groups in the region may prove enlightening. In recent history, Mai-Mai groups and local defence forces are still predominantly village-based and engaged by local leaders to secure personal and communal interests within regional and national networks. Like in the past, many conflicts arise from succession struggles and claims on land and resources, which are interwoven with personal issues on the village level like love affairs, family disputes, and thefts. Within these conflicts, the ambiguous nature of customary chieftaincy characterized by a tension between chiefs’ patrimonial privileges and their duties as civil servants, still plays a role. Nowadays customary authorities adopt similar strategies of harnessing armed forces to settle disputes and ward off threats to their authority.Footnote 49 Leopard-men killings were commonly used to discredit one's rival, for example by attacking his enemies and cast suspicion on him, or by attacking his subjects to demonstrate he was unable to keep his territory in check.Footnote 50 Despite the differences in governance contexts, traces of these rationalities can still be detected in contemporary northeastern DRC in the ‘firefighter-pyromaniac strategies’ used by political actors.Footnote 51

THE RITUAL CONTEXT

The ritual embeddedness of armed groups is another continuity throughout history. Among the Bali, the mambela ceremony revealed the most courageous and compliant candidates to become anioto, a position that required an additional initiation.Footnote 52 The anioto initiation described by Mbako, which involves candidates having to attack a dummy made of wood or a bunch of leaves, resembles the final phase of mambela during which candidates have to conquer the spirit maduali, represented by a tree trunk covered in leaves.Footnote 53 The vow of secrecy was common to both ceremonies, instilling fear for those breaching the vow would be killed. The nature of this ritual context is clarified further in the testimony of Malamba, the capita or assistant village-chief of the village of Mabiama, the ishumu in Bangombe's case.

Q: Who in fact has authority over the natives? You [chiefs appointed by the government] or the tata ka mambela [the leader of the mambela]?

A: That is the tata ka mambela.

Q: And the men whom Mabiama designated to participate in the expedition, could they refuse?

A: No, they could not.

Q: Are these designations made at random among the entire population?

A: No, these designations are made in well-defined families in which aniotism is hereditary, just as the profession of sorcerer or blacksmith is hereditary.

Q: Have you ever experienced cases where people designated to kill have refused and what happened?

A: It has already happened a few times but then they are poisoned mysteriously on the instructions of the ishumu who are the subordinates of the tata ka mambela.

Q: Can anyone become anioto?

A: No, one must have the bolosi, the mysterious disposition to become one, which is hereditary.

Q: Are these people known by everyone?

A: No, the ishumu know them.Footnote 54

The witness specifically points out Mabiama's role as an ishumu. While anioto basically was a hereditary function, all strong and courageous men could be identified by the ishumu to possess the bolosi or ritual predisposition and coerced into becoming leopard-men. Gang members stated that not possessing this bolosi was a reason for getting injured during an expedition. In Bantu languages the word bolosi (bulogi) refers to retaliatory magic or witchcraft that is socially approved if used by a leader.Footnote 55 The use of these spiritual techniques is in line with local notions of leadership evoked by leopard symbolism in which the supernatural power of a leader can be used to harm people in an occult, secretive way, for example, by means of poison or leopard-men killing. The leopard-men gangs consisted of family members and dependants of the ordering person. The ritual nature of the killings appears from the liminal character of the leopard-men group dwelling in the forest. On their expeditions, which were carried out under strict secrecy, they lived in the forest for weeks on end, in the vicinity of the villages they were supposed to strike. Mbako's gang members bore their initiation names while in the forest.Footnote 56 Imitated leopard paw marks and wounds in the neck were tokens of a ritual approach and were not intended simply to mimic leopard attacks and misguide the locals, as colonial administrators assumed. Threats were usually voiced before the killings, giving people a reasonable idea of who was behind them. The marks left on the crime scene symbolized the power of those behind the killings. Nowadays people still remember leopard-men as leopard-like people who took huge leaps from rooftops or trees to attack their victims.Footnote 57

The liminal state of leopard-men residing in the forest, like later Simba and Mai-Mai militias, is perhaps best signified by the use of dawa, or magic charms or substances, consisting of diverse ingredients among which human remains were exceptionally potent. In Mbako's gang, the eyes of the victims were used to prepare dawa, which the gang members then rubbed into incisions in their skin to make them strong and invisible, or onto their weapons to render them more efficient.Footnote 58 Occasionally ritual consumption of the flesh occurred.Footnote 59 The word dawa more generally means ‘cure’ in Swahili. The distribution of dawa to heal, harm, and protect people also was the core business of collective therapies in the region, in which violence could have a therapeutic dimension in countering social ills. This healing dimension is equally instilled in the title of ishumu. The word ishumu derives from the Bantu-word – kumu designating an important person. The word underwent a semantic shift to ‘healer, diviner, or medicine man’ in eastern Bantu languages, the influence of which also appears in other mambela terms.Footnote 60 The ishumu’s role in recognizing and appropriating the bolosi of young men with the purpose of addressing wrongs reflects his judicial authority in the mambela council, deciding over life and death. Today, Mai-Mai combatants still state that bolosi is bad, but that they use it for good purposes.Footnote 61 The higher incidence of leopard-men killings under colonial rule can be perceived as a means to deal with the tensions caused by colonialism, more particularly the loss of control over ancestral lands, resources, and people, the disturbance of generational hierarchies and gender relations, and the colonial judicial system's failure to resolve conflicts.Footnote 62 Besides comparing leopard-men with later forms of armed mobilization such as Simba and Mai-Mai, who also used dawa, leopard-men killings are comparable to other, related phenomena aimed at curing social ills, such as witchcraft accusations and ordeals elsewhere in Africa.Footnote 63

Having discussed leopard-men conflicts in the colonial context, these will now be used to assess different spatio-temporal manifestations in view of institutional dynamism. First the colonial cases will be used to hypothesize on precedents of leopard-men in the precolonial era, assessing their relation to Vansina's spiral of innovation theory. Subsequently, the occurrence of leopard-men killings at the heart of a therapeutic insurgency will be treated. In the final section, relations between anioto and the vihokohoko variety of leopard-men of the Bapakombe in Beni are assessed in view of cultural borrowing across related boys’ initiation complexes.

PRECOLONIAL ROOTS OF MAMBELA AND ANIOTO

Tensions between neighbours in what was to become the historical centre of the Mangbetu kingdom (between the Middle Bomokandi and Nepoko Rivers; Fig. 3) forced populations to adapt to their competitive environment or disappear, causing a sequence of institutional innovations in northeast Congo from 1600 to 1800. One of the outcomes was the expansion of mambela from a village level to lines of villages, promoting collaboration and social cohesion on a larger scale. Mambela was one of the ‘brotherhoods’ characterizing the sociopolitical organization of segmentary societies in northeast Congo, developed out of initiation societies.Footnote 64 They differed from any kind of central government, as found in the emergent chiefdoms of their northern neighbours, the Azande and Mangbetu. A large number of the populations involved in this process migrated from the Middle Bomokandi-Nepoko region into the rainforest, including the Budu and the Ndaka, with whom the Bali claimed to have migrated southwards.

Fig. 3. The dispersal of anioto and vihokohoko in northeast Congo.

In oral traditions, the use of anioto in precolonial times is mentioned in relation to two events. One tradition states that the Bali, Budu, and Ndaka fled southwards along the Nepoko River and reunited in the Mbari mountains near Bomili to get away from the southern Mangbetu (Meje) who developed larger, centralised chiefdoms and a superior military force (see Fig. 3).Footnote 65 According to the second tradition, leopard-men attacks were first used much later by a few Bali clans to claim their monopoly over iron ore mines in the Mbari mountains, preceding their migration southward into the forest where they still lived in the 1930s.Footnote 66 Both traditions entail motives for leopard-men killings that still prevailed in colonial times: to defeat one's rivals and to claim and safeguard control over land and resources. The passing on of leopard-men skills is also linked to mambela initiations and marital alliances. Anioto thus likely originated when the Bali had settlements along the Nepoko River, and developed in symbiosis with mambela.

Additional evidence comes in the form of a series of monkey-hunting costumes identical to the leopard-men costumes collected in northeast Congo.Footnote 67 Most of these costumes are from Buan Bantu-speaking populations, from which the Bali split off during migrations (Bua, Lika, Ngelima, Benge, Komo), but also from other populations whom they encountered, such as the Azande. One of the costumes was collected together with a bow and arrows, as seen in the mise-en-scène photograph by its collector (Fig. 4), though the costumes were equally unpractical for hunting as for killing people. The combined occurrence of these costumes with iron claws among the Bali presents an additional clue regarding the origins of leopard-men as an institution. The Bali obtained the technology of working iron after separating from their Buan Bantu relatives. The vocabulary related to this skill hints at a different origin (southwest Sudan, presumably).Footnote 68

Fig. 4. Mise-en-scène of an archer dressed for monkey hunting, Benge population, Congo. Photo by A. Hutereau, 1911–13 © Royal Museum for Central Africa AP.0.0.11078.

The production of iron claws must have occurred on the Middle Nepoko when ties with the nearest Buan Bantu relatives had loosened; there, the Bali had good access to iron ore. This is supported by the tradition that a dominant Bali clan controlled the iron ore mines at Mbari and used anioto to maintain its hegemony and safeguard access to the mines.Footnote 69 Many years later, numerous Bali still recounted having left Mbari because of anioto attacks.Footnote 70 Various cultural elements merged when the Bali resided at the Nepoko River, most likely in the Mbari mountains near Bomili, which remained an important centre of iron production in the following decades. This merging of cultural elements to constitute new institutions is a central feature of institutional dynamism, and common in this region. The symbiotic relationship between anioto and mambela was forged in such processes, as well as ties with other institutions.

Colonial functionaries’ attempts to disentangle mambela, anioto, and ishumu demonstrate their failure to understand that they were historically interwoven. The link between mambela and anioto was much discussed to find out who should be held accountable for leopard-men killings. In the 1930s mambela initiations were made public in an attempt to stop the leopard-men killings.Footnote 71 It allowed Mbako to try to shift responsibility for the murders to the mambela leaders. According to one of the police investigators, the mambela leaders had usurped a pre-existing lineage-based hierarchy of family chiefs (metundji), leading him to the conclusion that mambela officials were not the legitimate leaders.Footnote 72 Confusion also arose over who was the true leader of mambela, the tata ka mambela or the ishumu. The public hearings reflect that the mambela leaders were assisted by the ishumu, possibly as a result of titled functions of disparate origins merging within mambela. The ishumu represented a hereditary lineage-based ritual authority with judicial power.Footnote 73 He underwent the mambela ordeals twice, and received an additional series of mambela scarifications on his shoulders and arms.Footnote 74 The mambela hierarchy was interwoven with authority based on lineage seniority represented by the ishumu.

Authorities are thus layered, and the merging of several institutional elements and titles was common practice in the maintenance of fields of power. Mbako, who circumvented the power of the mambela council, demonstrates that such relations could be challenged and realigned with new situations. These micro-historical instances of agility are the drivers of institutional dynamism. As reflected in oral traditions and in material and linguistic evidence, such processes joined together costumes and claws, and anioto and mambela, in the competition with neighbours at the Nepoko River.

AMBODIMA: LEOPARD-MEN IN A THERAPEUTIC INSURGENCY

In 1916/17 a large wave of leopard-men killings sparked awareness among colonial administrators. This wave of killings occurred alongside the growth of a ritual dance known as ambodima or (m)basa, which provides us with an additional example of institutional dynamism. The spread of the dance was part of a new therapeutic movement adopted by the Bali from their northern neighbours in response to an existential crisis caused by forced rubber tax collection in 1907. The spread was characterized by the distribution of dawa and ritual drums, combined with the diffusion of anioto skills and the display of mambela objects, yet outside the context of the boys’ initiation.Footnote 75

People believed the dawa would protect them against the bullets of the Europeans by turning them into water. This gave them the courage to resist the forced collection of rubber, which caused their grim living conditions, and to take up arms.Footnote 76 The dance, which reappeared under different names, remained responsible for the spread of leopard-men killings in the following decades. Around 1930, delegations consisting of ambodima leaders, mambela officials, and dancers travelled from village to village, using the sale of palm oil as a cover. They carried ritual drums, mambela instruments, and an anioto claw hidden in a pot of palm oil. The performance of the dance consisted of a public part, but only mambela members could attend the secluded second part, consisting of a nocturnal dance and a meal. The ishumu told women and children to return to their houses and then the mambela objects were displayed. According to Mbako, improvised chanting occurred, during which the names of future victims were cited. The tata ka mambela designated men to go on a killing expedition by tying lianas around their necks. In most villages, mambela leaders were also the leaders of the dance. But apparently ambodima created new ties among villages, independent of those of mambela, and gang borrowing also occurred along these new networks. As the administration relocated villages alongside new roads, the gangs travelled discreetly via abandoned village trails. Denunciators were reportedly killed.Footnote 77

Ambodima was derived from the widely spread collective therapy nebeli, which was held responsible for rubber tax strikes and rebellions in the whole of northeast Congo around 1907.Footnote 78 In the 1930s, northern Bali chiefs involved in leopard-men killings, like Mbako, were still nebeli members.Footnote 79 Nebeli demonstrates how widely such a collective therapy could reach, adapting to various sociopolitical contexts in northeast Congo and South Sudan. In the 1850s, Mangbetu kings adopted it as a war charm from the people they subjected. Nebeli’s success in winning battles made it spread to neighbouring populations, and the use of dawa expanded to protecting initiates from harm and guaranteeing success.Footnote 80 Among the Azande in Congo and South Sudan, nebeli was one of many collective therapies by which people sought protection against the arbitrariness of Azande rulers, and the threats of the slave trade and colonization.Footnote 81 Nebeli medicine also occurred as a therapeutic influence at the heart of the boys’ initiation libeli among the Lokele.Footnote 82 The example of nebeli shows that collective therapies spread across centralized and segmentary political systems alike, incorporating them in larger networks of cultural borrowing, even if centralized courts like those of Mangbetu and Azande tried to control such processes. While the Mangbetu rulers willingly adopted nebeli as a war charm, the Azande rulers more reluctantly accepted it after vigorous attempts to repress it proved unsuccessful.Footnote 83 Evans-Pritchard wrote that among the Azande of South Sudan new ‘extra-kin’ associations such as nebeli were responses to an existential crisis connected to the breakdown of traditions under the slave trade and European rule.Footnote 84

Nebeli can clearly be perceived as a collective therapy that grew in response to the quest for healing, equally provoking insurgencies, in line with Janzen's characterization. Institutional dynamism is reflected in the spread of nebeli in both segmentary and centralized societies, and in its regional manifestation as ambodima incorporating pre-existing and new institutional features. In the context of ambodima, leopard-men violence remedied social disruption, analogous to the violence used in the context of the kitawala movement among the Komo to restore social imbalance.Footnote 85 If therapeutic insurgencies like ambodima – incorporating anioto killings – clearly vented anticolonial sentiments, they cannot be treated simply as a function of the colonial context since they are a manifestation of collective therapies with deeper cultural foundations. While these phenomena were important to deal with the difficulties induced by colonialism, they transcend the colonial context as their reason for existing.

VIHOKOHOKO: LEOPARD-MEN CASES IN BENI

The comparison of leopard-men killings among the Bali with those among the Bapakombe and Nande of Beni, known as vihokohoko, can help to reveal further institutional networks and dynamism, fleshing out a political history as yet only known from a bird's eye perspective. The anioto trials of the Bali helped to finally attract the authorities’ attention to a wave of killings in the Beni region in 1933–4, where earlier killings had been ignored. This led to the military occupation of the area. The Bapakombe minority inhabiting the forest northwest of Beni was accused of terrorizing their Nande neighbours, who were favoured by the colonial administration and held privileged positions. Ethnic favouring, which is not at play in the Bali cases, was an important catalyst to vihokohoko conflicts. In previous decades, ethnic opposition between the Bapakombe and Nande had grown, climaxing in the early 1930s. The Bapakombe homeland had been progressively incorporated into territorial units with the Nande, with leadership handed over to chiefs from principal Nande clan factions (or their clients). Furthermore, the Nande chiefs of Beni had been involved as intermediaries in slave trading and subsequently the Belgian colonization, more particularly the aforementioned Henry de la Lindi. Over several generations, these developments inspired what the colonial administration called a ‘conspiracy’ of the Bapakombe against the Nande. The latter were perceived as victims of Bapakombe leopard-men terror, but this was a one-sided perception. For decades, several Nande chiefs had sent their men to be initiated as leopard-men among the Bapakombe and similarly used them in conflicts, but the colonial administration developed a selective amnesia for the Nande involvement in the killings.Footnote 86

While no police or court records were found of the vihokohoko killings in Beni, the data collected suffices to make a broad comparison. Beni leopard-men were a very similar, if not the same, institution as leopard-men among the Bali. The Bapakombe supposedly adopted leopard-men from the Bali via their common neighbours (the Ndaka and a subgroup of the Budu-Mbo).Footnote 87 The original use of vihokohoko as a strategy is highlighted in the founding traditions of Bapakombe clans who first settled in the forest northwest of Beni. Leopard-men killings served to expand Bapakombe influence over populations who settled with them and to extort wives and food tributes.Footnote 88 Leaders of these founding clans passed on their vihokohoko skills to others, and in the colonial era one of these clans still was the dominant provider (Batangi Bapakombe). The spread of vihokohoko was also connected to the regular boys’ initiation ceremony named lusumba, similar to anioto’s link with mambela.Footnote 89 Like the Bali, the Bapakombe were a segmentary population whose boys’ initiation network was the basis for their sociopolitical organization and who used leopard-men killing against neighbours in a similar way.

The Bapakombe's boys’ initiation lusumba belonged to the same institutional network as mambela.Footnote 90 In both mambela and lusumba, the blindfolded initiates learnt that a bird spirit performed the scarification (mambela) or circumcision (lusumba) on their body. The aural qualities of these spirit birds were represented by horns or whistles blown during the cutting. Some very rare and artistically interesting horns from this region are kept in museum collections.Footnote 91 Interestingly, most Bali ascribed the origin of mambela to their southeastern neighbours, the Ndaka and Budu (Mbo) who had obtained it from the Komo.Footnote 92 The ‘bird initiation complex’ entails traces of an innovative impulse coming from Eastern Bantu speaking populations originally from the Great Lakes region, via the Komo and stretching as far as the Bali. This influence is apparent in lusumba and mambela rituals, terminology, and objects.Footnote 93 This is the exact opposite of the itinerary that must have taken the leopard-men institution to the Bapakombe in Beni. Since the ‘bird initiation complex’ comprised both the Bali and Bapakombe boys’ initiation networks, and leopard-men activities existed in symbiosis with both networks, the spread of leopard-men killings southwards appears as a part of the cultural exchanges across these networks. If several boys’ initiation complexes succeeded one another in the nineteenth century, such processes were ongoing in the colonial period, as exemplified by the replacement of mambela with lusumba due to the repression of the former among the Bali in the 1930s.Footnote 94

CONCLUSION

This article demonstrates the importance of studying leopard-men in northeast Congo as a form of armed mobilization rooted in local traditions that adapted to diverse contexts. The concept of institutional dynamism helps to overcome previous categorizations of leopard-men that impaired our understanding of them. This concept fits into a processual-network approach in which leopard-men straddle different cultural complexes, timeframes, and governance contexts, and act according to emic principles on the intersection between power and healing. After assessing leopard-men in view of institutional dynamism, it makes more sense that Mai-Mai groups from Beni claimed to continue the legacy of leopard-men during the First Congo Wars, while also counting former Simbas among their leaders.Footnote 95 The larger question asked at the beginning of this article returns: to what extent did institutional networks and processes of institutional dynamism set the scene for later political developments? Throughout the article, I have pointed out similarities between leopard-men cases and present-day armed groups. These appear in the causes for conflicts, the strategies used, and the village-based networks within which they operated. The strongest parallels can be perceived in the reoccurrence of ritually-empowered militias, and in their use of dawa, but also in the institutional dynamism that shapes them by merging traditional and new – foreign – elements. This principle of merging also occurs in the influence of Watch Tower on kitawala and of communist ideology on the Simba.Footnote 96 In the present the same cultural foundations continue to matter in the constitution of power, in the mobilization of people, and in the legitimation of their actions, including violence. The study of larger-scale therapeutic insurgencies such as kitawala and Simba is already gaining momentum, but many earlier phenomena such as leopard-men, ambodima, and nebeli remain buried in colonial records. A sustained diachronic comparison requires better historical knowledge of these diverse institutions, the dynamics that produced them, and the networks such processes brought about. As in the past, contemporary community-based militias continue to be framed as ‘rebellious’. Considering them as the reinventions of local political traditions, however, may provide a more appropriate analytical pathway.