Introduction: From Anatolia, 19th Century bc, to Babylonia, 17th Century bc

In a recent study, Gojko Barjamovic and Andrew Fairbairn discuss “a specific type of container called an aluārum” appearing in Old Assyrian texts from Kültepe dating to the early 19th century bc (ca. 1895–1865 bc). The aluārum was used for the storage and transport of fine wine (geštin ṭābum)Footnote 1 imported from the region of Mamma, located by Barjamovic near Kahramanmaraş (itself circa 70 km northwest of Gaziantep) in southeastern Turkey.Footnote 2 The authors go so far as to publish an image of a flask excavated at Kültepe which they believe could be an aluārum-vessel.Footnote 3 The published flask is one of at least nine of the same type found at the site, generally in cist-graves associated with Lower Town levels Ib and Ia; it is globular in shape with a short neck and a single handle, decorated with painted red and black concentric circles.Footnote 4 This decoration together with its fabric indicate that the vessel itself was non-local in origin. Along with others, the authors understand that the shape and decoration of the vessels point to their manufacture in North Syria and their use for the transportation of wine and other liquids.Footnote 5

This paper presents additional information in support of this identification, based on two complementary streams of evidence, the first archaeological, the second textual. The first point is that we can more securely identify a center of production of these vessels in north Syria, specifically in the area of Zincirli, ancient Samal, in the Karasu valley, at least within the 17th century bc (i.e. contemporary with Kültepe Lower Town level Ia). The second position is that textual references to pots called dugalluḫarum restricted to northern Babylonia in the same time (i.e., the Late Old Babylonian period) refer to those same aluārum-vessels, rather than to pots containing alluḫarum-dye, as has been previously understood. This coincidence is supported by the presence of similar globular flasks at Sippar and Ḫarādum in contexts datable to that same century.

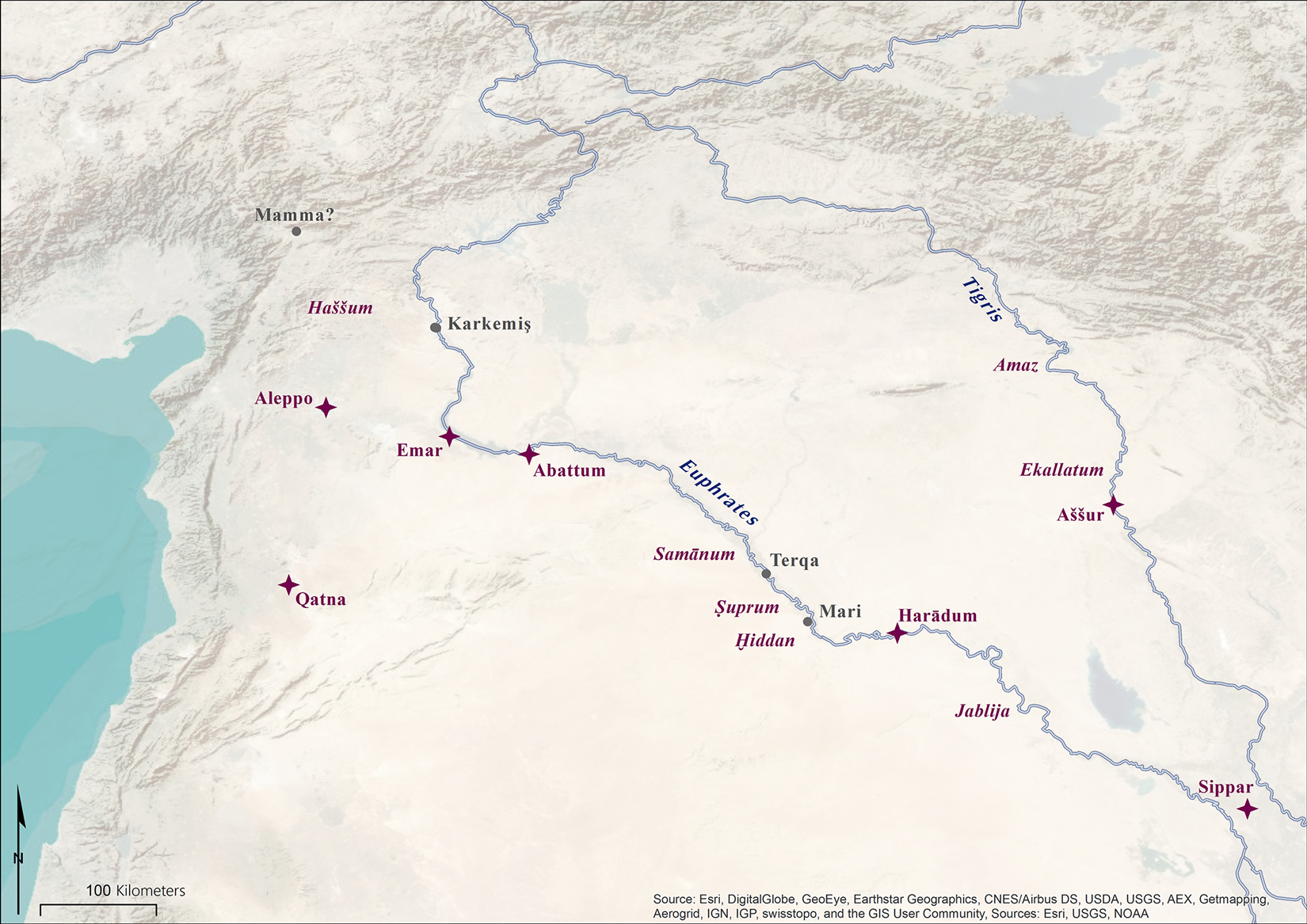

The geographic breadth of these attestations, on the one hand—as far north as central Anatolia and as far south as northern Babylonia—and the chronological restriction of the term to the 19th and 17th centuries bc, respectively—leads us to several interlocking conclusions. First, these attestations and allied evidence (see Appendix) point to trade between Babylonia and north Syria continuing down towards the end of the 17th century, despite the absence of direct textual references, perhaps reviving a Syro-Babylonian trade which is already in evidence for the 19th-century.Footnote 6 Second, a dramatic increase in references to Mamma in Kültepe texts of the Lower Town Level Ib period (for which textual evidence is generally sparse), combined with the appearance of the painted flasks in Level Ib and their increased frequency in Level Ia, indicates that the north Syrian trade was likewise of growing importance at Kaneš at this time.Footnote 7 We concur with previous suggestions that the product in question was almost certainly wine, for which the region was reputed already in the days of Zimri-Lim's palace at Mari, at which point (the 18th century) its large-scale trade was managed by middlemen.Footnote 8 We can now, however, tentatively reconstruct a regional trade centered on Mamma in the 17th century bc, one in which the globular flasks, or their contents, continued to play a major role. Furthermore, the textual and archaeological appearances of these vessels point to their being unusual objects even when empty of goods. These were containers specially designed for export, which designated their contents and users as participants in a recognized system of long-distance exchange. We propose that this system flourished until the Syrian raids of Hattušili I ca. 1650 bc, when the patterns of trade and communication changed in significant ways.

In what follows, we will examine first the archaeological and then the textual evidence for aluārum-vessels, and then conclude with a synthetic discussion. An Appendix of allied evidence for Late Old Babylonian trade appears at the end.

North Syrian wine in the Middle Bronze Age: the archaeological evidence

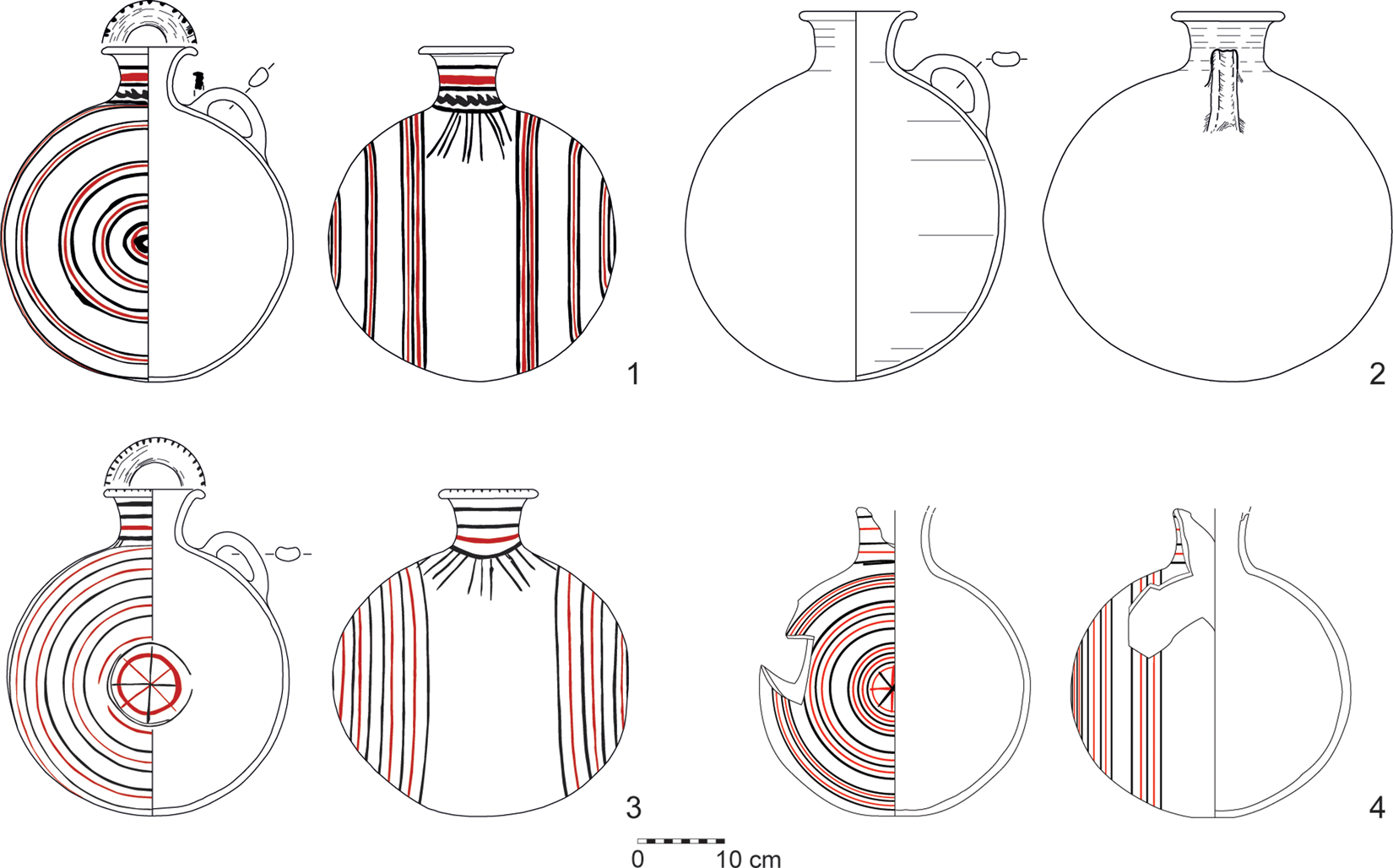

Recent excavations at the site of Zincirli in the Karasu valley of southeastern Turkey have yielded multiple examples of bichrome-painted globular flasks bearing close similarity to those found at Kültepe.Footnote 9 The vessels were discovered in situ within several buildings of a monumental architectural complex that was destroyed in a conflagration dated by radiocarbon to 1661–1631 cal. bc.Footnote 10 The globular or ‘pilgrim’ flask is a well-established type with a wide distribution, both geographical and chronological: it appears from Kültepe-Kaneš in the north and Tarsus in the west to Tell ed-Der/Sippar-Amnānum in the southeast, beginning at the end of the Early Bronze Age and extending into the Late Bronze Age, at least (see Fig. 1). Unpainted flasks appear first at Kurban Höyük on the upper Euphrates in layers dating to the EB–MB transition; they are found soon afterwards up and down the Euphrates, as well as at Kültepe, in the houses of Lower Town Level II (i.e., contemporary with textual attestations of aluārum-containers).Footnote 11 Bichrome-painted examples like those from the Zincirli destruction level are significantly more rare, however: aside from Kültepe, where all published examples come from cist graves dated to Lower Town Level I or, where more specificity is possible, Level Ia, only one other published globular flask, from a pottery storeroom at Tarsus dated to the local LB I level (which begins ca. 1650 bc, according to excavators), bears painted decoration.Footnote 12

Fig. 1 Distribution Map. Attestations of globular flasks in Middle Bronze Age contexts. Credit: Lucas Stephens

The Zincirli flasks are noteworthy in several respects. First, their decoration, consisting primarily of a series of alternating red and black concentric circles on the belly, sometimes with a cross or star pattern inside the innermost circle, is identical in several cases to that of Kültepe examples (see Figs. 2 and 3; compare details at rim and in innermost circle to Emre Reference Emre1995, Type A1a, cat. 7–9). Second, based on their fabric and the presence in the local assemblage of numerous other vessels decorated in the same tradition, excavators are confident that the painted flasks are a product local to Zincirli or its region in the late Middle Bronze II period (ca. 1800–1600 bc).Footnote 13 Their appearance in Kültepe Level Ia graves is thus the result of trade, direct or indirect, between the Karasu valley and Central Anatolia at that time. Third, their specific contexts of discovery at Zincirli, where they are found alongside special-purpose items such as funnels, as well as numerous drinking-cups, generally support earlier arguments for the shape's function as a container for wine; furthermore, grape, including grape pips and skins, is present in many archaeobotanical samples from these contexts.Footnote 14

Fig. 2 Aluārum-containers from Zincirli, ca. 1650 BC: Two examples of a globular flask, found side by side in Zincirli's destroyed Middle Bronze Age monumental complex (Room DD6, Building DD/II, Local Phase 4; C17-46.0B#6–7). Credit: Roberto Ceccacci. Courtesy of the Chicago-Tübingen Expedition to Zincirli.

Fig. 3 Aluārum-containers from Zincirli, ca. 1650 BC. Multiple examples of painted and unpainted flasks found in two buildings of Zincirli's destroyed Middle Bronze Age monumental complex (Room DD2, Building DD/I, Local Phase 4; Room DD6, Building DD/II, Local Phase 4). Credit: Cem Küncü, Karen Reczuch; prepared by Sebastiano Soldi; courtesy of the Chicago-Tübingen Expedition to Zincirli.

The globular flask type stands out in archaeological assemblages due to its unusual method of manufacture: the round belly of the vessel was formed by attaching two separate wheel-made bowls at the rim with a band of clay, a technique most closely associated with the typically Syro-Palestinian ‘pilgrim flasks’ found at coastal sites of the Late Bronze and Iron Age. Along with the presence of the handle — an unusual feature for inner Syria and Mesopotamia, but standard in MBA assemblages of western Syria and the Levantine coast — this marks it as an import in Mesopotamian contexts, as well as in Anatolia. At Hadidi, for example, Franken notes that the technique was “hardly ever used;” at Terqa, Kelly-Buccellati and Shelby conclude that the type “must have had a specific function as indicated by its very different manufacturing process and by the pattern of its distribution.”Footnote 15 The pattern referred to is the flasks’ appearance in significant concentrations at major Middle Bronze sites along the Euphrates, including Terqa and Tell Bi'a/Tuttul, but most notably in the Zimri-Lim palace at Mari, where they occur in groups ranging from 25–30 to as many as 98 vessels, usually in storage contexts near reception suites.Footnote 16 In these cases, the flasks in question are undecorated, and date primarily to the mid-18th century bc.

The palatial consumption of wine is well-documented in the Mari archives, as are its sources, which include the regions of Aleppo and Karkemiš, whence its shipment down the Euphrates by boat.Footnote 17 The wine-producing zone extended for some 300 km along the well-watered Taurus foothills of southeastern Anatolia and northern Syria, from the Mediterranean coast in the west as far as the Tur-Abdin in the east; evidence for wine production in this region appears as early as the mid-third millennium bc.Footnote 18 Wine remained a luxury import to Mesopotamia in the early second millennium, at which point, according to a recent study by Laneri, “wine produced in southeastern Anatolia and northern Syria was considered a precious and expensive commodity for kings and gods,” though rather less desirable vintages were also produced in the Middle Euphrates region, e.g. near Emar.Footnote 19 In particular, the highest-quality wine served at the Mari palace, designated sâmum, came from assorted vineyards in a relatively restricted (and probably slightly higher-altitude) zone, stretching from the Karasu valley in the west to Zalmaqum, just east of the Euphrates. Sâmum wine is documented regularly in shipments to the palace from both Karkemiš and Aleppo; Chambon places one sâmum-producing terroir, Zizkibum, specifically in the Amanus mountains.Footnote 20

Taken together, the north-Syrian affinities of the globular flask type, the vessel's distribution along the Euphrates, and the specific contexts of their discovery in the Mari palace made their identification as “wine jars from western Syro-Palestine” already probable when first proposed by Gates in Reference Gates1988.Footnote 21 The particular affordances, too, of the shape — its narrow neck, easy to stop up; its manageable, roughly standardized size, no more than 30 cm in diameter (yielding a volume of ca. 10–12 liters); its tendency to have one flatter side, the better to hang on a donkey's back — lend themselves to filling, to carrying, to pouring out, making their attributed function for wine a satisfying one, if still subject to chemical verification.Footnote 22

The presence of the flasks at Zincirli in MB II levels is therefore unsurprising. Zincirli is located south of the Taurus, in the narrow valley of the Karasu river, the ancient Saluara, at the foot of the Amanus mountain range (see Fig. 4). It is firmly within the wine-producing zone of north Syria, even that of sâmum wine. The site's name in the Middle Bronze Age is not known, and archaeological evidence suggests the settlement was no more than a few hectares in size in this period, making the most obvious interpretation that it was a satellite of a larger center.Footnote 23 The fertile river valleys east of the Amanus supported several contemporary palatial centers: Tilmen Hoyük, very likely ancient Zalwar, is only 9 km to the south, also in the Saluara/Karasu valley, itself a tributary of the Orontes;Footnote 24 Tell Aççana/Alalakh, seat of the powerful Bronze Age kingdom of Mukiš, vassal of Yamhad, lies 100 km to the south of Zincirli, in the Amuq plain. Zalwar was part of the kingdom of Anum-ḫirbi, a known contemporary of both Zimri-Lim, king of Mari, and Waršama, king of Kaneš, whose reign can thus be dated to the first half of the 18th century bc.Footnote 25 Anum-ḫirbi's dominion also extended over the region of Mamma. Barjamovic's proposed location of the latter at modern Kahramanmaraş, where the Amanus meets the Taurus, 55 km north of Zincirli, places the site within the greater Mamma region.Footnote 26

Fig. 4 Aerial View of Zincirli Höyük, Middle Bronze Age Complex DD (Area 2). The mountains in the background are the Amanus foothills. Credit: Lucas Stephens. Courtesy of the Chicago-Tübingen Expedition to Zincirli.

Archaeological evidence for MBA Mamma has thus far been scant; its identification with modern Kahramanmaraş rests on the discovery of two bronze spearheads inscribed with the name of Anum-ḫirbi in Old Assyrian dialect at the village of Hasancık(lı), 14 km northwest of the city (Donbaz Reference Donbaz1998). Survey of the Kahramanmaraş plain by Carter et al. in 1994 identified two mounds in the vicinity of Hasancık(lı) with early-second-millennium material, KM 173 and KM 174, that Carter proposes as candidates for the center of the kingdom of Mamma, along with a third, KM 178, 4 km to the south. She notes the valley's advantageous location at the intersection of routes from Syro-Mesopotamia leading north to Anatolia and west to Cilicia, as well as the presence of grapes in the surrounding hills.Footnote 27 The collections of the Kahramanmaraş Museum include numerous figurines found near Hasancık(lı) village and stylistically datable to the MBA (several votive pegs in bronze and as many as 50 clay bulls), lending further support to the proposed localization there of an important MBA settlement.Footnote 28 Textual evidence attests to the existence of an Assyrian wabartum at Mamma well into the later (kārum Ib) period of the Old Assyrian trade network. Along with Uršum (likely modern Gaziantep region, 120 km due east of Zincirli), with which it is very frequently associated in Assyrian texts, Mamma apparently represented the southern frontier of the Assyrian commercial circuit.Footnote 29

The region's association with locally bottled wine is steadfast.Footnote 30 Eight texts from Kültepe refer to shipments of wine relevant to our study.Footnote 31 Seven of these texts use some form of the term aluārum to describe the containers in which the wine was shipped.Footnote 32 Five of the texts specify this wine to be ‘(fine) sweet wine’ from Mamma; a sixth mentions Mamma as the destination of a traveller.Footnote 33 Of the OA attestations of aluārum-vessels adduced by Barjamovic and Fairbairn which specified the origin of the wine those vessels held, all identified Mamma for their appellation d'origine contrôlée.Footnote 34 When filled with wine, these vessels were expensive: one trader “gave 1 mina of good, native copper for another aluārum-container of sweet wine from Mamma,” a price comparable to that of a sheep;Footnote 35 as Barjamovic and Fairbairn conclude, “imported wine was clearly a luxury commodity.”Footnote 36 That the flasks appear with such frequency at Zincirli is both in line with the picture of the regional economy gleaned from the texts, and suggestive of the benefits savvy local actors may have accrued during this short period.

Mamma, with its Assyrian wabartum, was the most — if not the only — accessible north-Syrian market, at least from the point of view of Assyrians traversing Anatolia. Wine and globular flasks alike were certainly produced in a broader area, most of which was not accessible to Assyrian merchants due to exclusionary trade agreements.Footnote 37 Still, the impression left by this handful of texts is that the aluārum was a distinctive type of vessel, to the point of retaining its local name even in foreign contexts. Much like wine, an imported commodity that had recently become indispensable to both social and ritual life at Kaneš, the aluārum-container itself may likewise have held a unique cachet beyond its functional value, in that it signaled its user's access to broader networks.

OB dugalluḫarum = OA aluārum: the Babylonian connection

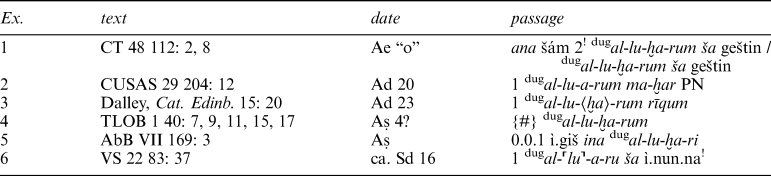

The word aluārum rings a Babylonian bell, because a small number of writings for vessels called alluḫarum (e.g., as dugal-lu-ḫa-rum) can be found in Late Old Babylonian texts. As Barjamovic and Fairbairn note, the term aluārum does not appear in the CAD, but the writing is unambiguous as a-lu-a-ra-tim ša karānim or similar: “aluārum-vessels (of wine).” This parallels the names for other containers for wine in Kültepe texts, including kūtu/kukkubu/karpat kerānim.Footnote 38 The understanding of these attestations in a Babylonian context has been somewhat strained, for the principal reason that alluḫarum is attested since Old Akkadian times as a “mineral dye” (per CAD A/1, 359–360). This substance — unlike vessels counted by number — was parcelled out sometimes by weight, more typically by volume, and occasionally unmeasured in recipes (“You grind [some] a.-mineral…,” etc.). The substance was associated in Old Akkadian, Ur III,Footnote 39 Old Babylonian, and Middle Babylonian writings with dyeing, tanning, and staining (esp. with liqtum/niqtum, another sort of dye or fixer),Footnote 40 whereas in Standard Babylonian medical and ritual texts alluḫarum was used primarily as materia medica/magica.

But six Late Old Babylonian writings mention alluḫarum as discrete objects, enumerated specifically as vessels, all restricted to texts from northern Babylonia of the 17th-century bc (see Table 1).Footnote 41 A brief description of these examples is in order. Example 1 is a loan of silver from Iltani, dumu.munus lugal, made for the purchase of wine in two alluḫarum-vessels. The purchase was to be made through a trading expedition, since the loan was to be repaid after the completion of a journey (ll. 7–8: ina erēb girri). Example 2 is a receipt text, documenting two 50-sila deliveries of oil for the purchase of male sheep. At the end of these lines describing these transactions (ll. 1–11) comes a single line before the date, apparently unrelated to the previous ones, reading simply: 1 dugal-lu-a-rum ma-ḫar PN.Footnote 42 Example 3 is an inventory of a dowry of household goods (numātu) — including copper and bronze vessels, stone rings, furniture, a seal, etc. — returned to a bride-to-be after her betrothed died.Footnote 43 Here, the alluḫarum-vessel is specified to have been “empty,” rīqum.Footnote 44 Example 4 is likewise an inventory text, this time of vessels distributed to various cult places and households. Here, a total of seven alluḫarum-vessels appear in five different consignments, alongside (but distinguished from) ca. 18 other “storage vessels” (dug.ì.dub, našpakum). Three of the consignments go to private households, including two to the household of Iddin-Ea (almost certainly the well-known judge by that name), and once to an oil-pressing workshop (é ì.šur); the other two listings are in broken contexts. The našpakum-vessels, by contrast, were sent to building spaces: to courtyards (kisallum), shrines (papāḫum),Footnote 45 and two temples (Babylon's Emaḫ and Esagil temples).Footnote 46 In no instance are the two vessel types sent to the same (type of) destination; the lexical and functional distinctions between našpakum- and alluḫarum-vessels in this text suggest that they were used in different ways.Footnote 47 Example 5 is a letter informing the unnamed recipient that a ten-liter alluḫarum-vessel filled with sesame-oil was being sent.Footnote 48 The letter notes that the vessel has been sealed (aknukam). The sixth and final text, Example 6,Footnote 49 is also a letter, likewise noting that an alluḫarum-vessel has been sent for sesame-oil; the provenance may be traced to the city of Babylon.Footnote 50

Table 1: Late Old Babylonian attestations of alluḫarum-pots.

Notwithstanding Walther Sallaberger's Reference Sallaberger1996 passing recognition that a vessel called “alluḫarum” must have existed,Footnote 51 what has generally and awkwardly been understood of these writings has otherwise been that the vessels contained alluḫarum-dye—despite the fact that they were clearly used to hold wine and oil in three of the examples, and empty in a fourth. Rivkah Harris in her review of CT 48 understood Example 1 to mean that “the man must here be commissioned to purchase two vessels containing alluḫarum dye ša x.”Footnote 52 Marten Stol later identified “x” in this text as geštin — rather clearly indicating that the vessels held or were meant to hold wine — but nevertheless reiterated that these were “special vessels” for the storage of alluḫarum which could simply otherwise be used also for other purposes,Footnote 53 and that “this fact suggests that alluḫaru was a liquid substance.”Footnote 54 Seth Richardson made the same error in 2010 when he published TLOB 1 40: despite the fact that the five entries of this inventory were directly parallel to (as he wrote) consignments of dug.ì.dub (našpakū), “storage vessels,” he understood dug alluḫarum as “pot(s) of alluḫarum” rather than “alluḫarum-pots.”

The error is now clear from more than one direction. First, most of the attestations indicate that the vessels held substances other than alluḫarum (wine, oil, and ghee); conversely, none of them are actually said to contain dye. Second, it runs against the general nomenclature of Mesopotamian vessels to name them after the thing they hold. There are dug.geštin, “vessels of wine,” but no vessel called a “karānum-vessel”; dug.ì.giš, but no “šamnum-vessel;” and so forth. Likewise, CT 48 112 and VS 22 83 do not mention “wine-vessels” or “oil-vessels,” but “alluḫarum-vessels” holding wine and oil. In keeping with typical constructions with karpatum (“vessel”) as part of a compound noun (i.e., as karpatum [ša] {x}), it is clear that phrases like dugalluḫarum ša geštin/ì.nun should mean “alluḫarum-vessel containing wine/oil,” and not “alluḫarum-vessel called ‘wine/oil(-jar)’.”Footnote 55 Third, all five examples are discrete objects, enumerated and not measured by capacity or weight, only by the quantities of other material they hold; it would be impossible to read any of the entries in Table 1 as indicating any quantity of alluḫarum-dye.Footnote 56 Fourth and finally, the orthographies include examples which cleave more closely to OA aluārum than to Babylonian alluḫarum, including dugal-lu-<ḫa>-rum (with -ḫa- restored), dugal-lu-a-rum, and dugal-˹lu˺-a-ru in exs. 2, 3, and 6, respectively. Conversely, none uses either of the ideographic writings used to write the name of the mineral dye (i.e., al.la.ḫu.ru or an.nu.ḫa.ra), though these writings may not yet have existed. It is not possible to maintain, then, that dugalluḫarum meant “vessel (full) of alluḫarum.” Rather, it was rather the name of a special kind of storage jar called an alluḫarum, which (as we argue below), probably had nothing to do with the mineral dye.

We face one of two possibilities for these two lemmata: either the references to the dye and to the vessels are the same words in different usage, perhaps only differently spelled or vocalized;Footnote 57 or these are two different words, near-homophones with different meanings and perhaps distinct etymologies. To the first possibility, the context of use does not clarify the issue much. What could “alluḫarum-pot” mean if it was named for the dye but not filled with it? It is possible, we suppose, that the name could describe the appearance of the vessel, e.g., to indicate that it was painted with alluḫarum, or at least was decorated bright white (as alluḫarum-dye is understood to have been colored), giving it an alluḫarum-like appearance. It could even be guessed that the name indicated that alluḫarum was mixed into the clay, temper, or other material in the matrix of the pot itself. Such explanations cannot be excluded, but they are unlikely: We are unaware of any context in which alluḫarum was painted onto ceramics or mixed into clay. Rather, it was used on leather, wood, and cloth.

It is more likely, then, that the second option is the right one, and that aluāru and alluḫaru are two different words: homophones overlapping for only one brief century in the Babylonian dialect of Akkadian. Whereas alluḫarum, then, was indeed a kind of mineral dye (used in substantially different ways before and after ca. 1500 bc), aluārum (as we will hereafter distinguish itFootnote 58) was a type of pot principally known from North Syrian and Old Assyrian contexts which made its way to Babylonia in the 17th-century. With the latter word, we are looking at a homophone assimilated into Babylonian Akkadian from Old Assyrian, aluārum→alluḫarum, perhaps on the simple basis of Late OB scribes misunderstanding the word they were hearing on the docks of the Sippar kārum as another they already knew how to write.

The unsteady range of orthographies for Akkadian alluḫarum, “dye,” already suggests its labile morphology: the word was written also allaḫaru,Footnote 59 annuḫarum, and (at Mari)Footnote 60 innuḫarum, alongside Sumerian al.la.ḫu.ruFootnote 61 and an.nu.ḫa.ra.Footnote 62 Given that the name of the mineral was already so protean, it is not hard to understand how a similar-sounding word might have been assimilated to a known Akkadian one. The inexact writings also point towards the word as having a specifically foreign as well as non-Akkadian origin: Markus Hilgert suggests it as a loanword into Akkadian based on its consistent lack of mimation in Ur III writings.Footnote 63 To this observation, one could add that the word does not present any readily apparent Semitic root,Footnote 64 and is absent not only from vernacular use, but from the list of ca. 510 vessel names given in ḫar-ra=ḫubullu.Footnote 65

What that other word aluārum was and meant, however, is difficult to determine. With no clear etymology, we offer one possible (but hardly conclusive) explanation for the origin and meaning of the word, that it may be related to a town in the Karasu valley called Alawari.Footnote 66 This town was the subject of a border dispute between Niqmepa of Mukiš and Šunaššura of Kizzuwatna, known from texts from LBA Alalakh IV, probably of the late 15th-century. It has been suggested that the place-name Alawari also persisted in later periods: an “Alawari/a” is attested in the 8th century bc assur letter, where it is the source of “good, big drinking horns” desired by the sender, who may have been in Karkemiš;Footnote 67 the classical city of Aliaria has also traditionally been located in the Karasu valley.Footnote 68 It is possible, then, that the town of Alawari and the word aluārum are etymologically related — the pot named for the place, or less likely the place for the pot. As noted earlier, the Karasu valley is well known as a region producing the highest-quality wines already in the Middle Bronze Age.Footnote 69 We propose, then, that it is at least possible that, much like modern wine-producing regions like C/champagne, the name of Alawari over time became interchangeable with that of its most famous product.

However, it is also the case that nomenclature for vessels in Akkadian generally does not derive from toponyms. Among about 700 Sumerian and Akkadian terms for vessels analyzed by Miguel Civil in a 1996 study, for instance, there is one “Amorite bowl” (Hh X 54, dugutul2 mar-tu) — but more likely an ethnonym than a toponym — and one possible “Malgium jar” (Hh X 294′), but Civil acknowledged the writing more likely to be sāgû (sa-a-gu-ú). If a toponymic root is to be sought for aluārum, then it almost certainly would have to be outside of the Akkadian language and lexical tradition.Footnote 70

It may not be possible, in the end, to understand the relationship between the word, the vessel, the product, and the place. Notwithstanding, if we accept the foregoing identity of Late OB alluḫarum-vessels with Old Assyrian aluārum-vessels, it seems necessary to think about how they (and the word) came to Sippar in the 17th-century bc specifically. The plain sense of it would be that trade goods from north Syria were reaching northern Babylonia during this century. A trade context would further help to explain the assimilation of aluārum → alluḫarum, given that it is more probable as an aural than a strictly orthographic error according to the suggestion made above.

Is it possible that despite the paucity of information about trade contacts in this Late OB time that people in Sippar and Babylon were drinking wine from Mamma, or at least receiving the region's signature storage vessels as trade goods, down through the whole of the 17th-century bc?Footnote 71 Certainly the range of places to which Late OB traders were journeying already suggests that this is perfectly likely (see Fig. 5). One pair of letters from Sippar — unfortunately undatable — between two merchants further demonstrates that shipments of “fine wine” (geštin ṭābum) coming to Sippar, along with other products associated with north Syria, were regular at some point in the period:Footnote 72

AbB VI 52: Speak to Aḫuni: thus says Bēlānum. May Šamaš and Marduk grant you good health. I told you before you left to come back, but you did not come back. Buy for me 60 pine-logs (of such-and-such a size) and 60 more of the Euphrates poplars for door-posts. Pay even a high price to have them shipped within five days to Babylon. (Meanwhile), the ships from the trading trip arrived here; why did you not buy fine wine (geštin ṭābam) and have it sent to me? Bring me my fine wine, and furthermore come and appear before me within ten days.

AbB XIV 187: Speak to Aḫuni: thus says Bēlānum. May Šamaš grant you good health. Buy for me the myrtle and the sweet-smelling reeds, of which I spoke to you, and also — now that a boat of wine has arrived in Sippar — wine for ten shekels of silver. Take it along and come sometime tomorrow to Babylon and meet me there.

What is particularly nice about these examples is that they speak about a trade in Syrian wine at Sippar in terms that suggest its regularity. What is problematic, however, is that overt evidence for direct trade between Babylonia and north Syria has been lacking for the 17th century, in contrast to the preceding 18th and 19th centuries.

Fig. 5 Map of Trade Destinations attested for Late Old Babylonian merchants from Sippar. Credit: Lucas Stephens.

The distribution of globular flasks certainly supports the idea of a 17th-century trade system. At Sippar itself, only one flask has been published, from a tomb associated with the final phase of occupation of the house of Ur-Utu in Sippar-Amnānum.Footnote 73 This phase corresponds to years 5–17 of the reign of Ammiṣaduqa, in roughly the third quarter of the 17th century bc. Unlike other flasks found in mortuary contexts, this one was incomplete, with only the upper half (the neck, shoulder, and part of the belly) preserved, bearing a decoration of incised concentric circles on the belly. The flask was apparently not intended as a funerary offering; rather, the large fragment was used to cover the body of the deceased, housed in a different vessel. This context of use suggests that the vessel could have been an heirloom, but it would be surprising if it had survived more than a few generations, thus making a seventeenth-century date for the flask's arrival in Sippar more than likely.

Upriver from Sippar, the evidence from Khirbet ed-Diniye, ancient Harādum, is more robust. The flasks appear in all Bronze Age levels at Harādum, from its foundation at the time of Zimri-Lim (Level 3D) until its abandonment in Ammiṣaduqa 18 (Level 3A). The excavators observe that the flasks appear in increasing numbers throughout Levels 3C and 3B2, and peak in Level 3B1, which is dated by documentary evidence to “between the reigns of Abi-eshuh and Ammiditana,” or ca. 1675–1650 bc. The flasks then sharply decline in Level 3A, wherein the only documents found date to Ammiṣduqa, i.e., to the third quarter of the seventeenth century.Footnote 74

That the flasks occur at Harādum in increasing quantity throughout the first half of the seventeenth century — corresponding precisely to the period when they are found at both Zincirli Höyük, as a local product, and Kültepe-Kaneš, as conspicuous imports — suggests not only that the trade relations between north Syria and northern Babylonia hinted at in texts existed, but that they were flourishing. Moreover, the conspicuous decline in attestations of the flasks at Harādum after ca. 1650 bc indicates a disruption of the supply chain that may well be connected to contemporary destructions at sites such as Zincirli Höyük and Tilmen Höyük in the wine- and flask-producing region.Footnote 75 Taken together, the textual and archaeological data clearly point towards the persistence into the 17th century of a trade in wine based in north Syria that extended at least as far as central Anatolia and northern Babylonia, though perhaps via several commercial circuits;Footnote 76 one in which, in both cases, north Syrian actors were sufficiently directly engaged as to preserve and export their own vessel-name, aluārum, along with the product it contained (as perhaps they had not been in earlier times).

As we argue in the Appendix below, some evidence can be marshalled for a continued Euphrates trade between north Syria and Sippar as late as the end of Samsuditana's reign. This comes through archives of traders in the 1720s; the existence of distance trader's property still extant in Sippar in the 1690s; the continuation of trade via Ḫaradum closer to 1650 bc; and a collection of references to northern trade as late as 1602 bc. Altogether, this evidence shows that a segmented trade connecting Babylonia to the Zincirli/Tilmen-Zalwar/Mamma region, if even indirectly, prevailed in the 17th-century, perhaps reviving a direct trade that had connected the Karasu valley with Babylonia even earlier in the 19th-century.Footnote 77

Discussion

The appearance of the terms aluārum and dugalluharum in texts from central Anatolia and northern Babylonia in the early 19th and 17th centuries bc, respectively, hints at a previously unsuspected connection between these two far-flung regions that, though intriguing, is difficult to parse. At the least, and notwithstanding the uncertain etymology of aluārum/alluḫarum, the texts provide us not only with a rare before-and-after instance of a loanword in reception, but one in which an aural context for transmission is most probable. It is clear in all contexts that the word refers to a specific, recognizable, and specialized container for the transportation and storage of liquids: most often of wine, and most often explicitly from north Syria, and/or in association with other products from the north Syrian region. That both Old Assyrian and Old Babylonian used a loan-word to describe the container in question presents two possibilities: either the word was separately but contemporaneously acquired by Assyrians and Babylonians from the same source, presumably the vessel's place of origin; or one took the term from the other, more probably the Babylonians (where it appears later, and in a range of contexts) from the Assyrians (where it appears earlier, and consistently in the context of north Syrian trade). Either scenario points toward the existence of a thriving trade centered on north Syria in the first half of the 17th century bc, whose reach extended far to the north and south.

The few historical details we can glean concerning the kingdom of Mamma allow us to go one step further. In Kültepe texts, Mamma most often appears alongside Uršum as a stop on a less-frequented southern route from Assyria to Anatolia, an alternative to the well-known road through Hahhum.Footnote 78 But the increase in references to Mamma in Level Ib texts, noted above, and the continued discovery of likely aluārum-vessels in Level Ia, implies that the Mamma trade took on greater importance in the mid-18th and 17th centuries—that is, in the years following the reign of Anum-ḫirbi, its most visible political actor. It is worth noting here that Anum-ḫirbi is referred to as king of Mamma in the Waršama letter, but king of Zalwar to in texts from Mari, apparently confirming the restriction of Mamma and Zalwar to separate commercial circuits; he was perhaps only briefly able to maintain control of both. Mamma and Zalwar were neighboring cities that only under Anum-ḫirbi are known to have been part of the same political unit. Mamma evidently continued, after Anum-ḫirbi, to have access to the central Anatolian trade, and (we now have reason to believe) Zalwar to the north Babylonian trade. Whatever their subsequent political makeup, it is clear that Mesopotamians and Anatolians alike continued to have a healthy appetite for wine for both social and ritual purposes, which, according to the analysis of Barjamovic and Fairbairn, was not limited to the elite.Footnote 79 It would seem that the wine-producers of the Karasu valley continued to capitalize on their interstitial position, simultaneously peripheral to and at the intersection of major exchange networks, well into the 17th century bc, on the strength of the desirable (and distinctively packaged) luxury commodity to which they controlled access.

This does not provide an entirely satisfying explanation for the transmission of the term dugalluharum to northern Babylonia, not least because only one of the attested jars is specified as containing wine. Both the archaeological and the textual evidence point toward the Babylonian aluārum being (re)used for other purposes, e.g., for sesame oil in Examples 5 and 6 (Table 1). This type of reuse speaks to the utility, as well as the relative rarity, of the globular flask form: as noted above, one would only keep records of an empty vessel if it had some value unto itself. It may be salient here to draw a parallel to the workings of the wine trade at Mari, where there was a clear standardization of wine and wine jars in bulk. Dozens of texts from Mari document the shipment of jars of wine and wine jars (i.e., not infrequently shipped “empty” [rīqātu]Footnote 80 by boat, in the hundreds at a time (see above).Footnote 81 As much as the scale of the trade are the occasional descriptions of the wine jars as šūbultum (“gift, shipment, consignment”) or rēš makkūrim (“available assets”).Footnote 82 A similar standardized exchange of wine-jars is implied by the system analyzed by Grégory Chambon, studying, among other similar phrases, “Y dug geštin (ana) tamlīt X dug geštin:” “Y wine-jars (as) replacements for X wine-jars.” Chambon notes that the parity of numbers between empty and full jars deserve special attention; and that both the quality of the wine and the type of container required general compatability. A system of jar-exchange would also make sense of the documentation of broken jars (see above), and the standard practice of accounting for full jars alongside empty ones within single texts.Footnote 83 It may further be said that a system of transfer such as this would have required the standardization of both the quality of wine and the vessels which contained it. It seems possible that the distinctive shape and decoration of the aluārum-vessel served to indicate and facilitate this re-use/exchange function: a distinct, standard vessel type which could be traded back as a deposit-container in exchange for new jars of wine.Footnote 84 On that understanding, the jars were used within a regional system of standardized bottling, where refillable or reuseable jars were worth tracking and exchanging between producers, traders, and consumers. We may thus consider, by context and comparison, that an implicit meaning of aluārum was to designate a vessel with such a function.

The significance of the chronological concordance among the terms and the flasks at Kültepe, Zincirli, and in northern Babylonia should not be overlooked. That the vessels occur in their greatest numbers in Harādum Level 3B1, datable by associated texts to the reigns of Abi-ešuḫ and Ammiditana, and in the final destruction of MBA Zincirli (Local Phase 4, Area 2), radiometrically dated to 1661–1631 cal. bc, bolsters arguments for the duration of Kültepe Level Ia, where they also appear, into the mid-17th century.Footnote 85 It also lends further support to the Middle Chronology, which places the accession of Ammisaduqa, and thus the terminus ante quem of Harādum 3B1, at 1646 (High Middle) or 1638 (Low Middle) bc.Footnote 86 Zincirli's destruction at this time may well have been at the hands of Hattušili I, who, in his Annals, claims responsibility for the destruction of the nearby palatial centers of Tilmen Höyük, MBA Zalwar, and Tell Atçana, MBA Alalakh (Level VII).Footnote 87 If Hattušili's rise to power was concomitant with the destruction of Zincirli in the mid-17th century, this makes one more argument in favor of the Middle Chronology. This explanation would reassemble several isolated storylines — the end of Assyrian trade, the rise of the Hittite kingdom in Anatolia, and the Fall of Babylon — and bring them together to illuminate an otherwise invisible century.

The rationale behind Hattušili I's campaigns in north Syria remains poorly understood: provoking the anger of the regional power of Yamhad seemingly posed an unnecessary risk to the still-nascent Hittite kingdom.Footnote 88 If, however, a burgeoning trade in wine from Mamma was providing economic support for a potential rival — one practically on Hattušili's doorstep: the letter of Anum-ḫirbi to Waršama suggests that Kaneš and Mamma shared a border, located somewhere near the Göksün pass — we could imagine that Hattušili sought to eliminate competition in supplying wine to Anatolia, access to which he could then leverage as political capital.Footnote 89 A truism often attributed to Napoleon goes that an army marches on its stomach; given the evidence marshaled here for the pivotal role played by the wine trade in strengthening cross-cultural interaction and ushering in sociopolitical change in the ancient Near East, it seems more apt to consider that the Hittite army was driven by drink.Footnote 90

Appendix: Babylonian evidence for trade with north Syria after 1749 bc

A proposal for a Late OB wine trade with north Syria in the 17th century faces at least two historical problems. First, it is curious that the term “alluḫarum-vessel” should be absent from Babylonian texts of the preceding 18th-century, when interregional trade (including trade in wine) is so much better attested.Footnote 91 The word as a name for a vessel was not even used at Mari,Footnote 92 which, given its intermediary position, one might have expected to reflect North Syrian words more than Babylonia did. As mentioned above, almost 200 Mari texts document the shipments of both jars of wine and wine jars, in the hundreds (see above, ad loc. fn. 81). These shipments included “good wine” (geštin du10-ga)Footnote 93 and wine from Karkemiš, Aleppo, Eluḫut, Apišal, and Uršum; and the texts note the distribution of wine to envoys from Terqa, Aleppo, Qatna, Ugarit, Uršum, Ašlakka, and other northern lands, as well as for “Babylonians.”Footnote 94 But despite the volume and frequency of this trade, the terms aluārum/alluḫarum never appear in Mari texts, either as names for vessels or for dye;Footnote 95 it is highly unlikely that the Mariote term ulluwuru is relevant in this context.Footnote 96 Neither is the vessel name known from texts of Shemshara, Karana, Leilan, or Terqa. We cannot explain this absence.

Second and more broadly, a Babylonian/North Syrian connection in the 17th century seems unlikely, given that the kingdom of Babylon was largely cut off from the outside world during this time, with little direct evidence for interregional trade. Evidence for diplomatic contact with the north is utterly absent, and no Babylonian campaign stretched any farther north than Saggaratum after 1716 bc, the date of Samsuiluna's restoration work there in his 33rd year.Footnote 97 This furthest northern reach was still more than 250 km short of places like Ḫalab, Zalwar, Ḫaššum, Karkemiš, and Emar; no information allows us to believe that Babylonian power ever extended anywhere near that far north either before or after this date.

But at this point, we can go a few steps farther. To begin with, it helps to state what we know of the Late OB trade. Present evidence already shows that Assyrian trade continued with Babylonia up to the very first years of Samsuiluna's reign.Footnote 98 Assyrian trade manifests from Sippar published by Christopher Walker and Klaas Veenhof as texts A, B, and C demonstrate this contact.Footnote 99 The manifests documented, among other products, goods most likely originating in north Syria or Anatolia brought into the Sippar kārum, including emery (šammu), crocus (andaḫšum), and juniper (burāšum).Footnote 100 The texts named merchants with clearly Assyrian names, and made reference to several Assyrian commercial terms and institutions. Both Walker and Veenhof connected Texts A, B, and C to other documents of the same era, especially a number of undated letters, to flesh out the business of these merchants in the Sippar harbor district in this time, with mention of contacts as far as Aleppo, Ekallatum, Emar, and Aššur.Footnote 101 In a separate article, Veenhof showed that the manifests (improbably dated by an Assyrian limmu-date) were probably drafted in the first year or two of Samsuiluna's reign, perhaps 1749 or 1748 bc.Footnote 102 This seems to conform to what prosopographic evidence there was, i.e., a few related documents clustering in the decade of the 1740s.

Following this time, however, we have no direct indication of Babylonian trade with the north, and such evidence as there was dries up, such as the presence of Old Syrian seals on Sippar texts known as late as the early years of Samsuiluna.Footnote 103 The apparent recession of trade data is likely related to the increasing isolation of Babylon after the southern revolts ending around 1740 bc, the period of disorder in Aššur following the end of Išme-Dagan's reign (ca. 1735 bc), and the breakup of Assyrian trade into smaller networks following the end of kārum Kaneš Ib (ca. 1700 bc).Footnote 104

We gather here, however, some disparate evidence which points to a gradual recession of this trade rather than any decisive termination, with a continued existence down into the 17th century. We may first note, as background context, circumstantial evidence for northern/Euphratean trade in the Late OB period, already long known, all the way down to the reign of Samsuditana, in six categories:

1. the continued Late OB drafting of commercial loans for journeys (e.g., ana erēb girri) as late as 1602 bc (Sd 24),Footnote 105 including one loan specifically identified for a journey up the Euphrates in 1613 bc (Sd 13);Footnote 106

2. temple loans for trade issued by Šamaš, at least as late as Sd 12;Footnote 107

3. the continued corporate existence of the Sippar kārum, at least as late as Sd 14;Footnote 108

4. the related Late OB incidence of ipṭerū-ransoms in payment of mercantile debts, at least as late as Sd 10? (BM 97138);Footnote 109

5. continued Babylonian access to slaves from northern lands,Footnote 110 as far to the northwest as ḪaḫḫumFootnote 111 and Uršum,Footnote 112 perhaps via Aššur,Footnote 113 as late as Sd 12;Footnote 114 and

6. the presence of other northerners in Babylonia, from Hana, Halab, Emar, Kaneš, and elsewhere, as mercenaries and workers, as late as Sd 14.Footnote 115

These phenomena are too broad to analyze to any certain conclusion, but suggest on a general level that travel to and trade with the north was still possible throughout the Late OB, even if not as easy or institutionalized as in former times. Below, we discuss three pieces of evidence which push the date of trade down towards the 17th-century in new and more specific ways.

Babylonian Trade with Syria/Aššur datable to ca. 1727 bc

We can now date two archives of OB trading letters to about 20 years after the trading manifests, to about 1727 bc. These are the contemporaneousFootnote 116 dossiers of the traders Nanna-intuḫ (AbB XII 32–50)Footnote 117 and Sîn-erībam/Awīl-ilim (AbB XII 51–58).Footnote 118 These were texts which Veenhof (Reference Veenhof, Charpin and Joannès1991: 302 n. 33) noted only in passing, probably for the good reason that they are unrelated to the group of traders he discusses. The letters of the former trader mention dealings in Amaz (no. 38),Footnote 119 Abattum (no. 39), Jablija (no. 40), as well as caravans (no. 40), the import of Subarian slaves (no. 32), and “merchandise” (no. 50). The latter letters discuss trade with Emar (no. 51), Ḫaššum (no. 51), Aššur (nos. 54, 56, 57, 58), Jablija (no. 55), Samānum (no. 56),Footnote 120 Suḫûm (nos. 56, 57), textiles (nos. 51, 54), and again caravans (nos. 53, 55), Subarian slaves (no. 56Footnote 121), and “merchandise” (nos. 52–53).

The date of the activities cannot easily be identified from these ca. two dozen texts alone, for the typical reason that the absence of patronyms and titles in letters do not easily permit prosopographic analysis;Footnote 122 indeed none of the names can with certainty be linked to that of any person known from a dated text. But a coincidence of personal names in the land-sale text MHET II 6 871 (Si 22, = 1727 bc) allows us to make the probable conclusion that the trade discussed in these letters dates to about twenty years after the manifests published by Walker and Veenhof. The sale document names an empty house plot (é kislaḫ) being sold as the property of the “city-house” (bīt ālim, an Assyrian termFootnote 123) and the rabiānum (l. 7); the co-sellers of the plot are identified as Awīl-ilim rabiānu and the elders of the city (šībūt ālim, l. 8).Footnote 124 Awīl-ilim's close associate Sîn-erībam is both the owner of a neighboring plot (ll. 3–4) and the purchaser of this one (l. 9);Footnote 125 the witnesses include two names matching Awīl-ilim's known associates, Ilī-u-ŠamašFootnote 126 and Rīš-Šamaš (ll. 17, 20). The land sale, moreover, comes from the same 1902-10-11 collection in the British Museum from which all the AbB XII letters derive. Altogether, the terms of the land sale suggest that the trade discussed in these letters was carried out ca. 1727 bc (Si 22),Footnote 127 about a generation after the Walker-Veenhof manifests.

The house of Mannašu dam.gàr ca. 1692 bc

A second piece of evidence tells us something about the existence of the Sippar trading community in the next generation, down into the 17th century. The life of this group is difficult to reconstruct, because the people mentioned in the Walker-Veenhof texts and their descendants are almost textually invisible outside of the manifests themselves: as informative as the three 1749 bc trading manifests are, they present almost no external connections to other Sippar texts. Other than the well-known Overseers of the Merchants, only five people named in the Walker-Veenhof manifests even possibly appear in other texts.Footnote 128 Otherwise, the persons named in those texts are virtually invisible to us prosopographically.

But we may now identify at least one certain exception: Mannašu, son of Kalumu, a merchant who acts in the 1749 bc manifests A and C (A: 13–14 and C: IV 21), reappears ca. 1690 bc as the owner of property in a much later list of fields (MHET II 5 656). This transaction is a seizure of Mannašu's property for back taxes, included as the second record in a summary of fields (the other three are all sales). This summary document dates to the latter half of Abi-ešuḫ's reign (post-Ae 19? / post-1692 bc), almost 60 years after the manifests were written. To be sure, it is explicitly noted that Mannašu by this date was “dead and without heirs” (mīt kinūnšu belīma).

But the text provides several important pieces of information, and it is worth reproducing the relevant passage of MHET II 5 656. Column 2 of the text gives:Footnote 129

1.´ ˹0.0.2˺ (+ x) iku ˹a.šà˺ a.gàr ˹bu-ra˺-a ki

i-˹ta˺ a.šà. bu-ut-ta-tum kù.dím dumu ˹d˺en.zu- ˹i-mi˺-[ti]

ù i-ta a.šà ka ka an * x x *

sag.bi.1.kam íd den.zu sag.bi.2.kam íd da-a-ḫé.˹gál˺

5.´ a.šà ma-an-na-šu dam.gàr dumu ka-lu-mu

a-na guškin ne-me-et-tim ša kar zimbirki-am-na-nu-˹um˺

ša i-na mu a-bi-e-šu-uḫ lugal.e íd idigna giš bí.in.˹kešda˺

šar-rum i-mi-du-šu-nu-ti

mma-an-na-šu dam.gàr mi-it ki-nu-un-šu bi-li/-ma

10.´ a-na ki-iš-da-at mma-an-na-šu dam.gàr

1 mu-ša-ad-di-in guškin

kar zimbirki-am-na-ni-im i-si-ir-ma

a-na a-pa-al é.gal

ù ˹den˺.zu-i-di-nam di.ku5 dumu dšeš.ki-a.maḫ

1.´ 2+ iku of field in the watering district of Burâ,

bordering the field of Buttatum the goldsmith, son of Sîn-imitti,

and bordering the field of …

its first main side against the Sîn-canal, and its second against the Aja-ḫegal canal:

5.´ the field of Mannašu the merchant, son of Kalumu,

for the gold-tax of the kārum of Sippar-Amnānum

of the year Abi-ešuḫ “o,”

levied by the king,

Mannašu the merchant, dead and without heirs,

10.´ for the share of Mannašu the merchant,Footnote 130

the tax-collector of gold

exacted payment upon the kārum of Sippar-Amnānum,

to satisfy (the demand) of the palace

and of Sîn-iddinam the judge, son of Nanna-amaḫ.Footnote 131

This document gives us information on trade and traders at both the individual and collective level. At the individual level, the text reveals a thread of local property ownership descending from the traders of 1749 bc down to some point soon after 1692 bc, and may exemplify a wider phenomenon. We learn that Mannašu was indeed a “merchant” (dam.gàr); that he owned productive land in the territory of Sippar-Amnānum;Footnote 132 that he died without heirs, implying that his property would otherwise have been heritable; and that this property was (by default?) under the authority of the kārum of Sippar-Amnānum.

The late date of the text, however, must give us pause. Although it is impossible to know when Mannašu of MHET II 656 died, the strong presumption is that it would not have been long before Ae “o.” We may assume this because tax delinquencies, when noted, were never long outstanding. From available attestations, whenever a taxable year is mentioned as it is here, nēmettum was levied only for the same year or the year previous to the document's date. From what we know, nēmettum was never collected for long-lapsed payments.Footnote 133 To believe that the Mannašu of the 1749 bc manifests only died shortly before 1692 bc, however, would require us to understand that the earlier Mannašu would have been old enough at the beginning of Samsuiluna's reign to be entrusted with goods for the bīt napṭarim, and yet still an active merchant almost sixty years later, well into the reign of Abi-ešuḫ. This seems unlikely, but cannot be proved or disproved on present evidence. This leaves us with three options: either the recently-deceased Mannašu of MHET II 656 was the same (but much older) man appearing in the manifests; or the Mannašu of MHET II 656 was the grandson of the man appearing in the manifests, named for him according to papponymic practices;Footnote 134 or the conjecture that the nēmettum due was recent is not correct, and was instead indeed long outstanding and the original Mannašu had died any number of years before 1692 bc. Regardless of which interpretation is correct, we still come to the conclusion that taxable family property of Assyrian traders still existed at Sippar in the early 17th century.

At the corporate level, we learn that the Assyrian commercial activities were situated in the kārum of Sippar-Amnānum specifically, a fact the Walker-Veenhof manifests A, B, and C do not make clear.Footnote 135 The “city-house,” the bīt napṭarim, and any other owned property of the merchants were therefore attached to this particular merchants’ guild. We may further be able to infer, if cautiously, that the kārum, at least as a taxable body, included Assyrians among its members, since they were individually liable for nēmettum to the kārum. The kārum was thus not only a corporation of local north-Babylonian traders trading locally and outward from Sippar, but included resident aliens from the north who could buy and sell real property, and be taxed for it. Finally, we learn that the Crown depended on the kārum not only for (import) taxes generally, but for gold in particular, which comports with the delivery of gold, as well as silver, to the governor of Sippar in manifest C I:22. While silver passed hands relatively freely in the Babylonian economy, it was likely that the import of gold was controlled by the state and its merchants.

From this text and its contexts, we may learn little about trade per se, other than that the kārum had ongoing obligations to deliver gold to the Crown as the tax on its commercial activities. But if we cannot see anything of the trading activities of the “Assyrian” merchants in this later time, we can see at least that their property and corporate identity survived in Sippar at least down into the early 17th-century.

The trading reach of Ḫaradum, mid- to late-17th c. bc

Third and finally, we can take note of the northern trade contacts maintained by the Babylonian fortress of Ḫaradum in the next two generations, as a forward trading post for Babylon. This activity is attested as late as Ammiditana's reign, and perhaps into Ammiṣaduqa's, as revealed by documents from excavated contexts. One letter (KD 65, Ad/Aṣ) quotes a merchant (šaman2-la2) who says that he delivered a large quantity of silver (1 talent, 20 minas) in Aššur to an Aḫlamu soldier called a “guard of the kārum of Ḫaradum” (lú maṣṣar karri uruḪaradiki).Footnote 136 A second letter (KD 97, Ad) concerns a legal dispute over silver which had been brought from Ḫaradum to the city of Emar.Footnote 137 Other letters mentioning Ṣuprum, Ḫiddan, and Yaḫurru also refer to Ḫaradum's connections to northerly places.Footnote 138 Among products mentioned, KD 81 (Ad/Aṣ) documents the import of cypress and cedar; KD 99 (Aṣ 18), a slave from the birīt nārim region, presumably above Terqa, where the Euphrates and Ḫabur part;Footnote 139 and several other trading expeditions are also mentioned.Footnote 140 One letter mentioning a “river toll” (miksu) leads the editor to conclude that Ḫaradum “was an official point of control on traffic on the Euphrates.”Footnote 141

Texts from the site also reflect documentary conventions of more northerly regimes. One Ḫaradum text is dated by a year-name of a king of Terqa (Iṣi-Sumu-abi), contemporaneous to the time Abi-ešuḫ or Ammiditana.Footnote 142 Two other texts use Assyrian limmu-dates, both of which must at least post-date 1719 bc, but very likely belong to the early 17th century. The first is KD 29, the limmu of Abi-Sîn (li-mu a-bi-xxx). The name is not found in the late date-list KEL G published by Cahit Günbatti, and must at least post-date its list (i.e. post-1719 bc),Footnote 143 but the Ḫabbasanu appearing in this text appears in others dated to the late reign of Abi-ešuḫ, so a date after 1700 bc is more likely. The second text, KD 41, is broken, and preserves only [li-m]u wa-ar-k[i…]), but prosopography again connects the text to an Abi-ešuḫ or Ammiditana date, closer to 1675 bc. Finally, at least one Ḫaradum text (KD 113, Ad/Aṣ), dating nearer to 1650 bc, features an Old Assyrian sealing, with a fragmentary chariot scene; Gudrun Colbow compares this to sealings known from Kültepe of earlier vintage (~level II).Footnote 144 Such clues, along with the many wine jars mentioned above, show us that Ḫaradum remained in touch with the north Syrian trade ecumene after 1650 bc.

Ḫaradum was at the same time, of course, in close contact with Sippar and Babylon. Almost all the documents found there used the date formulae of the Babylonian kings from Samsuiluna to Ammiṣaduqa. A legal settlement from Sippar (TLOB 1 95) connects people known from Ḫaradum to the judicial venue of Babylon, and one Ḫaradum document (KD 18) funds a journey to the southerly Babylonian fort of Dūr-Abi-ešuḫ.Footnote 145 What seems more probable, however, than direct and regular connections between Sippar and Ḫaradum is that the town of Jablija acted as a halfway trading post between the two.Footnote 146 In sum, Ḫaradum is perhaps better understood as one of a number of way-stations for a point-to-point trade which eventually came to replace what had, a century before, been an interregional trade in which merchants traveled over distances in the hundreds of kilometers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gojko Barjamovic, Virginia Herrmann, Gianni Marchesi, and Mark Weeden for reading drafts of this manuscript; all errors, of course, are our own. We would also like to thank the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Cultural Heritage and Museums General Directorate for permission to excavate at Zincirli, Chicago-Tübingen Expedition to Zincirli directors David Schloen and Virginia Herrmann for permission to work on the excavated materials, and all the members of the Zincirli excavation team, especially archaeobotanist Doğa Karakaya and ceramicist Sebastiano Soldi, without whose contributions the present work would have been impossible. Lucas Stephens also has our thanks for producing the maps appearing here.