Insurance providers have traditionally relied on global networks not only to expand the insurer's sphere of influence but also to support domestic business. British and European insurers have a long history of cross-border trade dating back to the birth of modern insurance markets in the 1800s. Mira Wilkins traces the development of international insurance markets, pointing to how strategic insurance firms were in developing international relationships and the value of these overseas markets to the firm's bottom line.Footnote 1 The British were among the first to develop the insurance business as a multinational enterprise (MNE).Footnote 2 The expansion of these firms abroad occurred first in America but by the 1850s and 1860s had extended to a global network of agencies and branches.Footnote 3 The Liverpool, London and Globe Insurance Company, for example, opened an agency in New York in 1848. Twelve years later it had agencies and branches in every major city in the world. As this company expanded, others followed in its footsteps. The Royal, the Queen, and the London and Lancashire all trod a similar path.Footnote 4 The Australian colonies were not the first ports of call in this internationalization process; British insurers were already active in the Americas, Europe, and Asia. Their distance from Britain and the immature state of colonial economies did not encourage early ventures.Footnote 5 By the late 1860s, however, this was changing and the colonies were viewed with more interest. The extension of international business allowed British companies such as the Liverpool, London and Globe to grow in size at a rapid rate. It provided another avenue of competition for firms constrained by the rate controls imposed by the Fire Offices Committee in the domestic market.Footnote 6

In Australia, the expansion of the fire insurance markets was linked to the emergence of a service economy from the 1860s.Footnote 7 This occurred as part of a sustained period of economic growth from the 1860s to 1890.Footnote 8 Key drivers of this trend were expansion in the agricultural sector, the development of manufacturing, and the growth of urban centers.Footnote 9 As colonial economies matured they became more attractive to foreign direct investment. In response, British multinational companies established a presence in the nineteenth century in key sectors, including mining, commodity trading, banking, wool-broking, and transport.Footnote 10 Simon Ville and David Merrett argue that it was Australia's ties with Britain that had a significant bearing on this trend.Footnote 11 British fire insurers followed this movement. As providers of risk mitigation products, they filled a gap in the emerging market for financial services that was driven by booming post–gold rush economies.

Many of the British businesses that came to Australia at this time were freestanding companies established for the purpose of international operations. They were not extensions of existing enterprises.Footnote 12 Fire insurers, on the other hand, were well-established companies within their home environment. As such they had clearly established branch and agency structures that formed the basis of their sales networks. Their entry into the Australian colonies was an extension of this and they brought with them their organizational cultures and business methods.

The significance of the establishment of British fire insurers in the colonies lies in how they were able to capture this market and mold it to reflect that of their home base. The effective cartelization of colonial markets led to the dominance of British firms over an extended period of time and left a legacy that had long-lasting implications for the history of the industry.Footnote 13 It was not until the 1970s that their market position was challenged.Footnote 14 By comparison, although British banks were early movers they did not hold on to gains made. In the 1850s they accounted for two-thirds of assets held in trading banks. They were instrumental in transforming the local market and introducing the branch system, which they used to effectively build their market position.Footnote 15 Yet this position declined progressively over time and by 1900 had fallen to 30 percent.Footnote 16 As Merrett suggests, Australian banks learned to beat the British at their own game. Local banks grew to be more competitive and profitable during the nineteenth century, relegating British banks to a successively smaller market share over time.Footnote 17 Unlike fire insurers, British banks were unable to capture the local market or perpetuate a cartel that restricted competition and protected the interests of market leaders. In terms of the broader experience of MNE expansion in the Australian colonies in the nineteenth century, fire insurance was a relatively unique market. British firms were able to consolidate their position by colluding to use private regulatory structures, such as controls over tariffs and entry conditions. In doing so they secured their place as market leaders. The story of the Australian fire insurance market highlights the diverse nature of multinational expansion. While other MNEs in the finance sector struggled to sustain market position, fire insurers were able to leverage network relationships in both home and host countries to become major players in their new location.

Interest in insurance history has increased in recent years. A volume edited by Peter Borscheid and Niels Haueter is testimony to this, as are a number of other publications highlighting the international experience of insurance firms.Footnote 18 Despite the insights that such publications provide, our understanding of the impact of insurance MNEs is limited in comparison to our understanding of the role of other financial institutions, such as banks. The aim of this article is to make a contribution to broadening our knowledge of the processes of establishing a presence in a foreign market. In doing so it draws on the literature relating to the liability of foreignness and internationalization process theory.Footnote 19

Explaining the Internationalization Experience

The ongoing debate surrounding the internationalization experiences of firms has taken researchers along a number of paths. Firms venture overseas if they are able to exploit specific advantages they may have. These may take the form of ownership advantages, such as those John Dunning identifies in his “eclectic paradigm.”Footnote 20 Alternatively, resource-based explanations suggest it is the possession of a unique set of capabilities that determines the ability of firms to successfully mount offshore operations.Footnote 21 Christopher Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal argue that the firm's ability to respond to the international environment is constrained by its internal capabilities, which are shaped by its administrative heritage.Footnote 22 The outcome of internationalization strategies is influenced by the environment in which the firm is operating, its structure, and management as determined by its administrative heritage.Footnote 23 Alternative theories, such as that put forward by Pankaj Ghemawat, highlight the role of distance. Distance has a number of dimensions but can be categorized into four main areas: cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic (CAGE).Footnote 24 This CAGE model offers a way of understanding the impediments to internationalization. Identification of the various elements of CAGE can assist in the development of strategies to overcome obstacles to global expansion.

Other models, such as those put forward by the Uppsala School, focus on the process of rather than the motivation for internationalization. Such an approach incorporates the role of organizational learning and considers the way in which offshore firms integrate into the host economy. Early explanations of the pattern of internationalization centered on the modes of entry and highlighted the state and change aspects of the process. Complicating this process was the “psychic distance” between the foreign market and the domestic market. Psychic distance relates to problems associated with understanding the business environment of the new location. The larger the psychic distance the greater the liability of foreignness that a firm had to address to successfully establish in the new market.Footnote 25

The Uppsala model has evolved in response to changing economic and regulatory foundations and the developing body of knowledge in regard to the behavior of firms. More recently, Jan Johanson and Jan-Erik Vahlne have argued for a reorientation of their original hypothesis to incorporate the role of networks in influencing internationalization. This represents a shift of focus away from the firm to the relationships between the players involved. Johanson and Vahlne state that “foreign market entry should not be studied as a decision about modes of entry, but . . . be studied as a position building process in a foreign market network.”Footnote 26

In contrast to emphasis on the decision to enter a market, a network approach considers the process involved in establishing in that market. Networks in this context are defined as business networks comprising two or more interconnected relationships.Footnote 27 These relationships allow participants to deal with the issue of uncertainty or the unknown elements of foreign markets in a more effective way.Footnote 28 Networks may comprise a number of multifaceted groups.Footnote 29 In manufacturing, this may include supply chain relationships and those involved in other activities associated with the production and sale of physical goods. In a service industry, such as insurance, the groups involved in the network would have a different focus reflecting the nature of the product and how it is distributed. The players in this context would be the managers and agents appointed by the firm to build business and customer relationships.

Successful internationalization is determined by the ability of the firm to leverage existing networks and become embedded in new networks, that is, to become “insiders” within the business networks of the host country. They can do this in several ways: by creating new networks (extension), by expanding networks (penetration), or by leveraging existing networks in other countries (integration). Those firms that cannot link into relevant networks experience the liability of outsidership.Footnote 30 This problem revolves around the inability to build the necessary business networks to fit into the new environment. In this sense, networks are a way of hedging against risk, expanding knowledge of host markets, and reducing the impacts of moral hazard.

The Uppsala model suggests that the process of internationalization occurs in stages. The first stage is characterized by irregular activity in an international market, the second occurs through the use of agents, the third with the introduction of a subsidiary arrangement, and the fourth with a full commitment to the new market. This incremental explanation has been criticized because of its deterministic nature.Footnote 31 The pattern of internationalization may not necessarily follow this straight line; it can vary. An explanation posited for this is that variation exists in the level of risk as levels of uncertainty and commitment change.Footnote 32 This may account for the fact that the internationalization strategies pursued by British insurers did not establish or go beyond that of subsidiary arrangements in the period under consideration.

Networks are important, particularly in service industries such as insurance, which depend on business relationships to mitigate risk. A number of publications point to the role of networks in the international expansion, particularly of British insurers. Borscheid and Haueter trace the development of a “global risk network.”Footnote 33 Wilkins alludes to the importance of networks in international insurance markets, as does Robin Pearson in referring to British fire insurers.Footnote 34 Other authors, such as Clive Trebilcock and Barry Supple, highlight the influence of networks in promoting the internationalization of specific companies.Footnote 35

The experience of British fire insurers in gaining a foothold in the Australian markets suggests that elements of the internationalization process model, as they relate to the role of networks, could be helpful in understanding the early struggle these firms faced. However, the market was not operating within a constant set of parameters. Broader financial-sector disturbances were influential in the mix, indicating that markets may be idiosyncratic and may unexpectedly provide a twist that leads to path divergence. The issue for British insurers was in establishing and building networks. The argument in this article is that this was influenced both by the business acumen of these companies and by the changing nature of the market in which they operated.

The entry of British fire insurers into the Australian market was ultimately successful. These firms had a prominent and enduring presence there for many decades in the twentieth century. The manner in which this was achieved suggests that these firms were able to overcome the issues associated with the liability of outsidership to become “insiders” in the host market. Establishment was not a simple process or matter of moving from agency to branch network, as suggested by early iterations of the Uppsala model.Footnote 36 Although this model was commonly followed, it was not sufficient to create the market share required for successful multinational expansion. Instead, British fire insurers had to build their firm's connectedness and integrate into market networks in order to use this as a stepping stone to gain influence within this environment. In achieving this, they were ultimately able to become market leaders. Networks in this context can be defined as interconnected relationships with business players within the sphere of the firm, within the local market, and within the industry. The key players in this respect are the British fire insurers and the managers they employed to oversee their interests in international markets. In terms of the Johanson and Lars-Gunnar Mattsson model, they used a combination of integration and penetration to establish their market position in the host country.Footnote 37 In the first instance, fire insurance firms coordinated a wider global network of branches and agencies. They also formed a collusive association (the Fire Offices Committee) that set the parameters in which the market operated (integration). At the level below this, managers appointed to the colonies and other parts of the globe had the remit of building the local networks that would assist in establishing a presence in the host country and foster the replication of market controls that governed the home market (penetration).

Building these networks in an operational sense was an important step on the path of successful integration. The experience of British insurers in the Australian colonies highlighted the initial difficulties in doing so—difficulties that were resolved through a combination of enterprise, luck, and resilience that encouraged the experiential learning necessary to foster the long-term commitment. Enterprise was evident on the part of both the home office and the managers appointed to run the Australian business in securing firm and local networks. Luck played a role in providing market conditions that favored overseas firms at a time when they were well placed to take advantage of them. Resilience was manifest in the ability of these firms to introduce and enforce an enduring collusive agreement that restricted competition and protected an increasing market share. This article will proceed with an account of the early development of fire insurance in the Australian colonies. It then investigates the way in which British fire insurers established in the market. The process of consolidation is discussed in the following section. The discussion and conclusion consider what light this case study can shed on the process of MNE colonization.

Setting the Scene: The Early Development of the Fire Insurance Industry

The first fire insurance companies appeared in Australia in the 1830s. At that time, the immaturity of the economy did not provide strong prospects for industry growth and expansion. Demand was comparatively low as the degree of urbanization was limited. Private infrastructure, and therefore risk, was not great enough to warrant substantial levels of insurance. The emergence of local firms in the population centers of Sydney and Hobart was accompanied by the establishment of agencies of British firms. However, overseas offices were not aggressive competitors for business at this point in time.Footnote 38

The pattern of development, evident in Table 1, indicates that it was not until the late 1860s that overseas companies started to enter the Australian market in a serious way. The number of overseas companies with a presence in the colonies doubled during the 1860s and had more than doubled again by the end of the century. This trend reflected the global push by British fire insurers from the mid-nineteenth century. The British were pioneers in promoting an international fire insurance network. Pearson suggests this occurred in three stages. Initially, fire insurance firms were linked to the business of British merchants trading in the West Indies. These companies exploited the established mercantile trade networks to build their presence overseas. The second stage, from the 1820s, was built on the emergence of bilateral reinsurance treaties contracted with European insurers. This avenue allowed British insurers to develop overseas connections and networks through the use of agents and brokers. The third (and most significant for the Australian colonies) phase was marked by the growing importance of fire insurers from the North of England.Footnote 39 They included the Royal; Commercial Union; Liverpool, London and Globe; London and Lancashire; and North British and Mercantile. From the 1850s, they took the lead in offshore expansion, particularly in the Pacific, Far East, and Antipodes, using it to boost their domestic returns.Footnote 40

Table 1 Number of Fire Insurance Companies in the Australian Colonies

Sources: Derived from Garry Pursell, “Development of Non-Life Insurance in Australia” (PhD diss. Australian National University, 1964), 159; and Dr. Garry Pursell, card index, G. Pursell private papers in possession of the author.

Several factors combined to make the Australian market more attractive to British insurers after the 1860s. On the demand side, the colonial gold rushes of the 1850s initiated a prolonged period of economic expansion, which was associated with increased immigration, industrialization, and urbanization. This was of particular significance for insurance markets. It was associated with a sustained increase in population, particularly in urban centers, and an expanding manufacturing sector.Footnote 41 Demand for insurance products increased as colonial economies became more sophisticated.

On the supply side, conditions in domestic British fire markets were approaching saturation. The proliferation of fire offices in the early and mid-nineteenth century was associated with growing competitive pressures and market instability.Footnote 42 The unstable nature of British markets, which were characterized by periods of intense rate cutting, resulted in the formation of the Fire Offices Committee. This cartel imposed a collusive agreement that regulated rates but stimulated other forms of nonmarket competition.Footnote 43 This together with the saturation of the domestic market encouraged firms to look offshore. The Australian colonies were just one area that attracted their attention; others included South America, South Africa, the United States, and the Far East.

Table 1 suggests that multinationals became more committed to the Australian market in the 1860s. This was a trend that was also apparent in other countries around the same time.Footnote 44 In that decade, twelve new entrants established a presence; however, this was offset with the exit of five. In the following decade a further twenty-six companies set up some form of business and there were nine exits.Footnote 45 The number of exits highlights the difficulties associated with establishing business in a foreign country. Early letterbooks of companies like the Sun Fire Office draw attention to a number of problems. Five key issues posed significant constraints on the ability of firms to build the connections that would allow them to grow market share: the unstable nature of the market, distance, communication channels, market knowledge, and moral hazard. They characterized the commercial and operational risk associated with international expansion. Four of these five problems relate to building and maintaining business networks.

The expansion of the market in the 1850s and 1860s was accompanied by the introduction of fire tariffs or pricing agreements. Price-fixing arrangements were common among British companies and accompanied their overseas ventures.Footnote 46 Such agreements were notoriously unstable and frequently broken. The informal nature of early tariffs and lack of substantive penalties meant that they were powerless to stop cheating, which occurred on a regular basis.Footnote 47 The Victorian tariff of 1867 provides an example of the conundrum overseas companies experienced. This tariff was agreed in late 1867 by all companies and their agents operating in Victoria, but competitive pressures led to its abandonment in 1868. The managers of the Sun lamented its demise, indicating that the subsequent lowering of rates would mean business would not be worth having on such terms. They wrote, “such are the results attendant on a business left to the uncontrolled conduct of agents who in the course pursued have not shown that they had the interest of their employers at heart.”Footnote 48

Competition from local firms was also very strong. The Sun representative sent to investigate the insurance business of the colonies reported that local companies were gradually cutting out the English ones. Melbourne companies were said to have “a great hold on private business owing to their character and the manner in which they employ their funds by mortgage.”Footnote 49 The provision of finance was seen as one way of locking in clients, and the networks of local insurers were used to promote this practice.

The letterbooks of the Sun reveal the unstable nature of insurance markets in colonial Australia at this time. Undercutting, the practice of paying brokerage, and the less than scrupulous activities of local agents contributed to the uncertainty foreign companies experienced.Footnote 50 Companies such as the Sun refused to accept lower rates, leading the Melbourne agent to report to company managers that progress there “has of necessity been checked.”Footnote 51 This together with the nature of the fire risk they were underwriting made colonial ventures perilous. Large fire losses were common as the capacity to fight fires was limited by the disorganized state of fire brigade facilities. In 1862, for example, a fire in Sandridge, a suburb of Melbourne, wiped out a block of twenty-five buildings.Footnote 52 Such losses were not uncommon.

Distance was a further issue that hampered market expansion activities. The distance between major population centers like Sydney and Melbourne meant that markets were localized and focused on one particular urban center. There were in fact a series of urban markets operating in isolation from one another. Local providers tended to operate in either Sydney or Melbourne. Overseas companies tended to use Melbourne as a base but to establish agencies in other colonies. Managers of the Sun saw the distance between head office and the antipodes as a serious weakness of the agency system. They worried about their inability to respond and give instructions in the event of the breakdown of any tariff. They were concerned that agents may act against the interests of the company and anxious about the distance of agents from head office and their ability to make unsupervised decisions, feeling that this placed them at a “great disadvantage.”Footnote 53 They were confirmed in their opinion by other insurers such as the North British and Mercantile and the Royal.Footnote 54

Communication issues went hand in hand with the problems associated with distance. Lack of effective communication channels between managers of overseas companies and their agents presented a barrier to expansion. British offices attempted to centralize their operations as much as possible, to ensure regular communications between managers and agents. As the Melbourne representative of the Sun stated, “to those accustom to the insurance business it must be apparent that constant supervision within 7 days’ post must protect the company's interests.”Footnote 55 Australian markets were more remote; before the advent of the global telegraph network in the 1870s it could take weeks for letters to reach their destination. The opening of the telegraph link between Australia and Europe did not necessarily increase the competitiveness of British firms in the colonies, but it did allow for the faster transfer of information and reduced the isolation of British agents and managers in the colonies.Footnote 56

Market knowledge was a further impediment for early MNEs. They constantly struggled to gain a picture of local markets. Local firms were often secretive and reluctant to share information.Footnote 57 Agents were frequently asked to provide maps of towns and suburbs, along with detailed descriptions of buildings and businesses. An example of their poor acquaintance with colonial markets was the refusal of companies like the Sun to insure the properties of squatters, despite being informed that they were the “wealthiest and most reliable class of businessmen.”Footnote 58

The reason given by the Sun managers for their caution in the colonies was their fear of fraud. They argued that on remote pastoral estates “fraud could be perpetrated without fear of detection.”Footnote 59 This alludes to an even greater concern, that of moral hazard. Colonials, the managers of the Sun felt, were not to be trusted. Acutely aware of the convict past of the colonies, it was felt that the morality of the colonialist was “lower than in England.”Footnote 60 In this respect it was argued that while they might not be prone to lighting fires, they always tried to benefit from them. Even the conduct of local insurance companies was thought to reflect the “inferior morality” of the population, particularly in the way they conducted their business and undermined market stability.Footnote 61

Details of British companies operating in the Australian colonies in 1870 are given in Table 2. Accurate statistics on the total number of British firms in existence are not available; however, Supple estimates that around fifty fire insurers were operating in the United Kingdom at that time.Footnote 62 From Table 2 it is evident that nearly half of those companies had some sort of exposure in Australian colonial markets. Many were also active in other parts of the globe. Thirteen of the twenty-one companies listed in Table 2 were present in the United States at this time.Footnote 63 These companies also pursued an international agenda in other countries and regions around the world.Footnote 64

Table 2 The Entry and Exit of British Insurance Companies to 1870

Source: Dr. Garry Pursell, card index, G. Pursell private papers in possession of the author.

a Liquidated in 1902.

b Business transferred to Royal Insurance in 1891.

There are a several aspects evident in Table 2 that provide insight into the progress of expansion into this market. Nine of the twenty-one companies listed exited within five years, four of those within one year. Seven companies reentered the market, usually within a decade of exit. Some companies exited and reentered multiple times. The decade up to the end of the 1860s was a period of growing interest in the colonial market but not sufficient to sustain a long-term commitment for over 40 percent of entrants. Between the 1850s and 1860s the Australian colonies had begun to industrialize and urbanize. However, high per real GDP (an average of 12.8 percent in that decade) masked relatively unsophisticated infrastructures.Footnote 65 Urban populations were centered in two major cities (Melbourne and Sydney), and transport and communication systems were underdeveloped, building structures and codes unregulated, and water supplies unreliable.Footnote 66 From a distance the market prospects may have looked good, but in reality the risks were high and the rewards unpredictable.

Significantly, it was several of the major players that exited at this time. Companies such as the Commercial Union, Phoenix, Sun, and North British adopted exit/entry strategies that saw them reenter once insurance markets were deemed large enough to spread risks and stable enough to warrant a presence. In respect to other insurers, Garry Pursell suggests that companies like the Royal and Norwich Union, although they had agencies in the colonies, did not actively pursue business at that time.Footnote 67 Exposure was limited principally to the Sydney and Melbourne markets. Within those markets insurance companies further attempted to limit risk by restricting areas in which policies could be sold.Footnote 68 In these markets, the use of agents was the principal means used to build business. These agents were often the large business houses that operated in the commercial arena. Such agents could be representatives for multiple companies. They did not necessarily have expertise in the insurance arena or the incentive to progress the sale of insurance policies.Footnote 69

In the decades prior to the 1870s, British insurers struggled to break into colonial markets because of problems associated with building and maintaining the interconnected relationships that would allow their networks to flourish. Distance and associated communication problems led to isolation from home offices and hindered the advancement of agency arrangements in the host country. In addition, the parochial and competitive nature of local companies that jealously guarded their territory impeded the development of local networks.Footnote 70 As a consequence, the ability to reap the benefits of existing and new networks was limited, making it hard for British firms to integrate into colonial markets.

Sustained Market Entry and Expansion

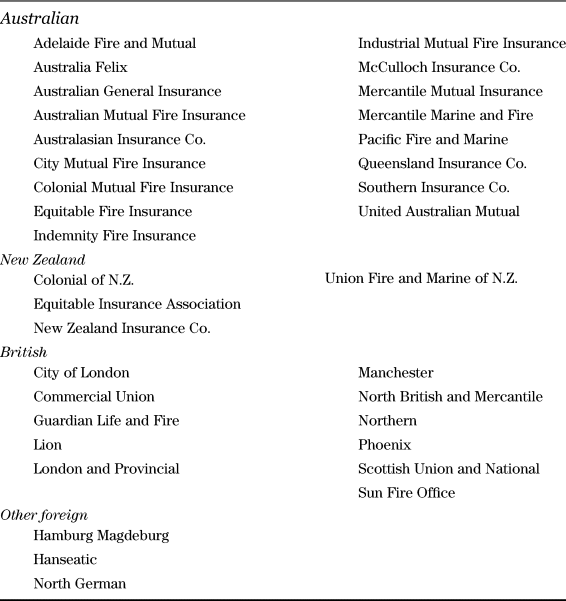

In the period up to the 1870s, British insurers were basically testing the waters in the Australian colonies. The level of commitment from most firms was low. For the most part it was constrained to the employment of an independent agent hired to sell insurance. Only two companies, the Queen and the London and Lancashire, had any form of branch representation. This began to change in the 1870s, when a threshold commitment, a more concrete step in the integration process, was made. The expansion of British firms overseas at this time was as much a response to market pressure in Britain as to a perceived profit in the Australian market. International expansion allowed British companies formed in the 1830s and 1840s to grow and rival their competitors in the home economy.Footnote 71 This together with the maturation of colonial economies and the expanding urban landscape made Australia a more attractive option than it had been previously. The after effects of the gold rushes and the associated increase in economic growth encouraged the expansion of cities such as Melbourne and Sydney in the 1870s. These centers became commercial and financial hubs. This in turn attracted British capital and stimulated the growth of financial and other business services. Simultaneously, industrial activity increased, spurred on by the demand for building materials as urban construction increased.Footnote 72 While this type of expansion brought with it new risks and uncertainties, the emergence of colonial cities that bore some resemblance to their British counterparts created an environment British insurers were more familiar with. However, the entry of British firms at this time was more than matched by an influx of local suppliers. Table 3 indicates the extent of the influx, not only of British and New Zealand companies but of locals. Of the thirty-five new firms listed, seventeen were Australian and eleven British.

Table 3 Fire Insurance Companies Established between c.1877 and 1880

Source: Australasian Insurance and Banking Record, 1879–1885 (Melbourne); Dr. Garry Pursell, card index, G. Pursell private papers in possession of the author.

In 1867, the Sun recorded nine colonial and nine British companies operating in insurance markets in Melbourne and Sydney.Footnote 73 Table 2 highlights the pattern of entry and exit of British companies. There was also limited interest from other overseas jurisdictions; there was one New Zealand company (New Zealand Insurance), and two Dutch companies also traded. They purported to sell fire insurance, but up to the 1880s their business was purely marine.Footnote 74 In terms of the local market, a sharp economic contraction in the 1840s had all but wiped out the early starters.Footnote 75 It was not until the mid-1850s that indigenous firms began to appear in any numbers. Most, however, were reported to be “bubbles” with insufficient capital to survive.Footnote 76 The nine companies that did survive were the Victoria, Cornwall, Derwent and Tamar, Australian Alliance, Colonial Fire, Pacific, United, Sydney Fire, and Adelaide Fire.

As colonial economies expanded and matured in the 1870s and 1880s, British fire insurers looked to increasing their commitment in Australian markets. Articulation from agency to branch provided an avenue to further increase their market presence. In the decade from 1870, eight British fire insurers entered the market in a more significant way, six of them in the two years from 1877. Pursell identifies dates of “significant” entry of British firms, defined by either growth in market share or establishment of a branch or local board of directors.Footnote 77 While it is difficult to pinpoint a precise reason for this pattern, two factors were likely to have influenced the decision to increase stakeholdings in the Australian colonies at this time. On the supply side, increased competition not only in home markets but also in European markets provided an incentive to look further afield.Footnote 78 On the demand side, the beginnings of a land boom in the colony of Victoria as well as the growth of urban centers in other colonies created opportunities for business expansion.Footnote 79

It was during this time that the firms that were to become major players in the Australian market established in the colonies. The Royal and Norwich Union had preceded this push, opening local branches in the early 1870s. Total fire premiums of British companies that operated in Australia suggest that these firms were significant players within the industry both in the colonies and in their home country.Footnote 80 This aligns with the experience in the British market, which was dominated by several large and well-established companies—those Supple identified as the “young and thrusting companies” that were among the leading insurance companies in Britain.Footnote 81 They included the Commercial Union, Royal, North British, Liverpool, London and Globe, the London and Lancashire, and the Queen. The influence of these companies placed a constraint on the competitive fringe, making it easier to establish a more robust tariff agreement in Britain.Footnote 82

The establishment of branches in the commercial centers of Melbourne and Sydney not only represented a level of permanency and commitment by the parent company but also brought with it a more sophisticated approach to building and strengthening networks. The home/host network was extended by the selection of managers to run newly opened branches or central agencies. Managers selected to run branches were chosen carefully. The Royal, for example, felt “compelled to send out to Melbourne from here a gentleman on whose practical knowledge and judgement we could place the utmost reliance.”Footnote 83 Charles Salter was appointed manager for the Royal; W. H. Jarrett was recruited to manage the Commercial Union, and Clement Jarrett the Sun. All were experienced and well known in insurance circles. Once appointed they went on to build local networks integrating into the local insurance and business community. They became leading influences in insurance circles in the colonies and were instrumental in the formation in 1880 of Insurance Institutes, holding early presidential positions.Footnote 84 The three managers published frequently and were reported in the insurance press.Footnote 85 They were also influential in both the destruction of early tariffs and the formation of those in the late 1890s that were more enduring. In this respect, the personalities of colonial managers were an important element of the strategic push by British companies into the colonies. Through actions such as these, British companies were at last able to start building local networks. However, their effectiveness was not immediately apparent in the highly charged, competitive environment that existed in the 1880s. Networks were not cohesive or stable at this time. Both British and local firms often acted aggressively toward each other, undercutting or cheating on tariffs when the opportunity arose.Footnote 86

The entrance of nearly forty insurance companies into the relatively small Australian market in a four-to-five-year period in the late 1870s led to a scramble for market share. This pursuit was marked by high levels of distrust among insurers and periods of severe rate cutting interspersed with short-lived collusive agreements. British firms initially struggled to gain a foothold. The proliferation of local firms and their links to the broader commercial circle impeded progress. Newly established local firms had little to lose in pursuing business. Rate cutting was rife.Footnote 87 The existence of a relatively large number of mutual fire insurers was a particular thorn in the side of foreign companies. These companies used bonuses earned to discount premium rates to members. The agent appointed by the Sun reported to head office that the determination of mutual offices to get business at any price made it impossible to quote rates.Footnote 88

A further way in which competitive pressures were manifest was through the agency system. As the market expanded, the demand for reputable agents increased, outstripping supply. Commission rates were pushed up and other inducements given to attract agents. Firms competed not only by attempting to attract good agents but also by employing as many agents as feasible in localized areas. Other practices, such as giving agency discounts that could be passed on to the buyer in the form of lower premiums, generated further competitive pressures.Footnote 89 The agency system created another element of instability. Insurance companies could enter the market by setting up an agency at relatively little cost and then, through a variety of methods, undercut market rates.Footnote 90

British companies retaliated by undercutting and disrupting local markets on a regular basis, highlighting the fragility of the cartel arrangements. The weak oligopolistic nature of colonial insurance markets encouraged the incentive to collude. This type of market conduct was also evident in many other insurance arenas.Footnote 91 Tariff agreements, however, were generally short lived; in Victoria, for example, in the fifteen years prior to 1881 twelve were made and broken.Footnote 92 Many of these were at the instigation of overseas players. Several foreign companies were particularly aggressive in breaking tariff agreements on a regular basis, with the main culprits being the Royal, Commercial Union, and Liverpool, London and Globe. The tactics of the Commercial Union were said to be a deliberate attempt to push out local firms.Footnote 93 The Commercial Union was particularly assertive when it came to breaking tariffs and remained unapologetic about its approach.Footnote 94 Other firms, including the Liverpool, London and Globe, simply refused to cooperate. Without the support of such firms it was not possible to gain agreement on rates.Footnote 95

Despite the transition from agency to branch, the market expansion of British companies in the 1880s was slow. The progress of the Commercial Union, for example, was said to be “not spectacular.”Footnote 96 One reason was the strength of local businesses whose positions had been reinforced by the booming economy in which they operated. The economy of Victoria, and in particular Melbourne, was fueled by an escalating land boom. This expansion increased the demand for fire insurance. In such a climate, rate cutting could be supported by the increase in policies sold. In addition, the land boom provided investment income that could also be used to offset the impact of rate cuts.Footnote 97 Like other members of the financial sector, local fire insurers capitalized on the land boom by investing heavily in mortgages and property. In 1890, over 50 percent of the total investment by fire insurance companies was in these two categories.Footnote 98 While this left firms overexposed, it provided a very profitable return in good times.Footnote 99

With rising levels of demand and increasing nonpremium income, local firms could afford to act more competitively. While British firms may have at times encouraged the breakdown of tariffs, local firms were often quick to take advantage of the situation to build new business. The principle applied, according to the vice president of the New South Wales Insurance Institute, was to “get business, no matter how it was done.” The boom time made these companies more resilient than British competitors expected. However, this situation could not last indefinitely. Many local firms operated on very small margins for loss. The ratio of total losses to premium income was on average between 60 and 70 percent in the early 1880s.Footnote 100 In this case, underwriting profits were quite low, a trend influenced by two factors: the first was the variability in premium income sparked by disruptions associated with the breakdown of tariffs in that period, and the second was associated with the rapid expansion of urban centers and the industrial growth within these centers. Risks increased as timber became a more common building product and the spread of factories and warehouses amplified the danger of larger fires occurring more frequently.Footnote 101 One way of tackling the issue was for fire insurers to pool risk by utilizing their networks to provide cover for larger businesses. This had the twofold benefit of cementing network associations and reducing exposure to loss. The Australasian Insurance and Banking Record provides details of major fires and insurance company payouts in this period. What is evident is that major risks were frequently shared among a group of insurers. For example, a fire in a wholesale druggist in Melbourne in 1882 resulted in eleven insurance companies paying out £10,000 each.Footnote 102 The stock of a hardware store in Melbourne in 1888 was insured by twenty-six insurers, each liable for between £500 and £2,000.Footnote 103 These firms could not cooperate to stabilize rates but were prepared to work together to reduce loss due to fire risk. This highlights the often contradictory behavior of the weak oligopoly that characterized fire markets in the colonies.

During the period from the late 1870s to the mid-1890s British firms solidified their home/host networks by moving away from a reliance on agents to the establishment branches. The judicious appointment of managers to these branches enabled them to enhance their local influence. The more aggressive firms used this growing influence to disrupt the market and destabilize tariff agreements. However, to this point they were not successful in capturing control in the market. Local firms, operating in localized markets, remained competitive and in many cases were the beneficiaries of these actions. The nature of their own business networks allowed them to undercut rates by offering commissions and bonuses to agents and policyholders.Footnote 104

Consolidation and Establishment of Market Power

The inevitable collapse of the land boom in the late 1880s heralded a period of financial chaos that had as profound an impact on local insurance firms as it did on other parts of the financial sector.Footnote 105 In the fire insurance industry between 1891 and 1900, twenty-three of the thirty-four local companies exited the market or were absorbed by other firms.Footnote 106 The results were more startling in the two major centers. In Sydney, ten of the fourteen companies in the market in 1890 were not in existence in 1900. In Melbourne, six out of seventeen survived.Footnote 107 The major problem that these firms encountered was the structure of their investment portfolio, which made them very vulnerable to the fall in land values and the bankruptcies of other businesses. Unlike banks, fire insurers were not able to access overseas bond markets. At home the immaturity of financial markets meant options were limited for the investment of capital. By default, investment was geared to the mortgage market. Rodney Benjamin's analysis of the firms that failed reveals that most of them held more than 75 percent of assets in loans on mortgage, which were susceptible to variations in land values.Footnote 108 Ron Silberberg calculates that the average rate of return on urban land investment in Melbourne was 78.3 percent in 1887. By 1891 this had fallen to 8.4 percent.Footnote 109 Falling rates of return were associated with falling property values and, with that, a decline in the value of those assets. Lack of specific colonial data makes it difficult to determine the exposure of British companies. Pursell suggests that while they did hold a proportion of mortgages the bulk of their investments appears to have been in government bonds.Footnote 110 This together with the size of their total asset base relative to local companies made them better able to weather the financial storm that enveloped the colonies in the early 1890s.

The fall in the value of assets was also compounded by a series of large fires that resulted in severe underwriting losses and forced local insurers into the realization of assets at a time when values had not recovered.Footnote 111 This course of events was serendipitous for British insurers. Luck was on their side.Footnote 112 With the decimation of local competition, the stage was set for them to capture the market. Having gained the upper hand, the key players were anxious to bring a measure of price stability into play. Having previously undermined tariff agreements, they were now keen to see the implementation of a universal tariff that was binding across the industry. British companies, with their experience of the Fire Offices Committee, pushed for a similar arrangement in the colonies. It is no coincidence that five of the six people responsible for drafting the new tariff were managers of British firms: Charles Salter of the Royal, William Jarrett of the Commercial Union, John Sinclair of the Northern, George Russell of the North British, and Clement Jarrett of the Sun.Footnote 113 In this case, British companies were able to leverage their connections at home and locally formalize their network power. They enlisted the assistance of the British Fire Offices Committee, which issued a circular in June 1894 noting that British offices were unanimous in wanting a local tariff and tariff association and requiring the colonies to toe the line.Footnote 114

In 1895, at the instigation of the foreign branch of the British Fire Offices Committee, a meeting was held in Melbourne with a view to reaching a tariff agreement for New Zealand.Footnote 115 The consensus reached was the stepping stone for later agreements in the Australian colonies, and the process culminated in the Victorian fire tariff agreement of 1897. Within three years, all colonies had adopted similar arrangements: New South Wales and South Australia in 1898, Western Australia in 1899, and Tasmania in 1900. The 1897 tariff formed the basis of a long-standing agreement among firms. A complex document, it aimed to set rates for every fire risk in the colonies as well as to establish codes of behavior and practice.Footnote 116 Whereas previous tariffs had been more informal, with codes of behavior largely implied, this agreement set out in detail regulations governing the conduct of business. Premium rates were laid out according to a complex set of tariffs that sought to quantify every risk. Similarly, terms and conditions of policies were specified and a uniform fire policy adopted. In addition, firms were restricted to using brokers and agents who were likewise registered under the agreement. The number of agents employed by each firm was restricted, as was their commission.Footnote 117 In attaching restrictions on agents and brokers the agreement effectively controlled one of the pivotal channels of competition between firms. Previous tariffs had broken down when agents and brokers were offered higher commissions and were induced to give rate discounts.

Restrictions on both price and nonprice competition through the tariff system created a degree of market stability that contributed to the system's resilience. Although the number of local firms gradually increased over time, for the most part they joined the tariff. Those that did not operated in the emerging markets of motor vehicle and third-party insurance. This process effectively segmented the insurance market in the twentieth century. The mainstream insurance market was controlled by the tariff firms that provided fire, accident, and general insurance. In this market, the British firms dominated and were market leaders. While data on market share does not exist, it is possible to glean some information on the position of leading British insurers in the fire insurance market. Table 4 provides a comparison between the underwriting surplus of the Commercial Union's Australian business and that of Australian fire insurers.Footnote 118 It should be noted that the Commercial Union was one of the larger British insurers in Australia. Notwithstanding, the differentials in underwriting ratios are highlighted, especially after 1897.

Table 4 Underwriting Surplus as a Percentage of Premium Income in Australia

Sources: Constructed from the records of the Commercial Union, Foreign Letterbooks, Australia 1895–1907, Dr. Garry Pursell, card index, G. Pursell private papers in possession of the author; the Australasian Insurance and Banking Record, 1895–1907 (Melbourne); Garry Pursell, “Development of Non-Life Insurance in Australia” (PhD diss. Australian National University, 1964), tables A.6 and A.10.

In Australia, the structure of the tariff and the way in which competition was constrained through the number of agents a firm could employ, initially encouraged amalgamation. Foreign companies in particular acquired local firms (see Appendix 1). Mergers and acquisitions were seen as a means of increasing market share and overcoming some of the restrictions of the Discount Brokerage and Agency agreement.Footnote 119 This loophole was closed in 1909 after it was agreed that the total number of agents allocated per company in a specific area could not be increased through mergers with other companies. However, takeovers continued to be a feature of the market throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

Supple makes the point that the pattern of expansion of British fire offices led to the emergence of large-scale amalgamated companies.Footnote 120 This trend resulted in the emergence of large composite offices marked by the joining of accident, fire, and life insurance business, allowing the acquiring companies to reap economies of scale, acquire agency networks, and reduce competition.Footnote 121 The extent of this trend is evident in Appendix 1, which illustrates the degree to which British fire offices acquired both local and overseas competitors. Sixteen British offices actively engaged in merger and acquisition strategies, which had a direct impact on the structure of the Australian fire insurance market. Only three Australian firms acquired other companies at this time. Two of these, the Commonwealth Traders and Union Insurance, later merged with British companies.

In the aftermath of the ravages of the 1890s, only eleven local fire offices were in operation in 1900.Footnote 122 Many of these companies were acquired by British firms over the next two decades. For example, the London and Lancashire bought out eight local insurance companies between 1910 and 1931, the Commercial Union acquired two, the Sun three, and the Phoenix two. This trend slowed the regeneration of the local presence, although the number of indigenous fire offices began to gradually increase, to an estimated fifteen in 1910 and twenty in 1920.Footnote 123 More broadly, the amalgamation trend among British insurers themselves also influenced the makeup of the Australian market. The Atlas, Commercial Union, Royal, and Royal Exchange were aggressive in acquiring multiple competitors. These companies came to dominate the industry in the 1920s and 1930s.

Appendix 1 also provides details of the assets acquired through merger activity. British firms were able to build and extend their network of branches and offices through mergers and acquisitions. Acquiring firms were able to gain significant numbers of agents. Although the Discount Brokerage and Agency agreement prohibited an increase in the number of agents held by a firm in a specific area, it did not restrict the acquisition of agencies in areas where the insurer did not have a presence. Merger activity allowed British insurers to broaden their distribution networks by taking over agencies in suburban and country areas where they had not previously been present. The London and Lancashire, for example, gained 131 agents in Melbourne, 971 agents in various Melbourne suburbs, and 2,503 agents in country regions. Chief agencies and local directorships gave these companies state and regional bases upon which to further extend their influence. It also allowed firms to add new forms of insurance covers to their portfolios. By acquiring general, accident, or even specialist firms (such as plate glass), new knowledge opened opportunities in new markets. By the end of the 1920s, the structure of the Australian fire insurance market was clearly established with British firms as acknowledged leaders.

The imposition of a long-lasting tariff agreement from 1897 allowed British insurers to consolidate their position in the Australian market.Footnote 124 In doing so they were able to resolve many of the issues that had plagued earlier attempts at assimilation. They were able to overcome initial problems in building networks and to leverage their network connections to extend their influence and ultimately dominate the market. The pooling of information associated with the tariff and the acquisition of a number of Australian companies provided access to the market knowledge and local networks that had previously impeded expansion.

The Role of Enterprise, Luck, and Resilience

With the 1897 tariff agreement, British fire insurers cemented their influence within the Australian fire market. The way in which they were able to capture the market provides insights into the processes of MNE integration. Johanson and Vahlne argue that networks are fundamental to the achievement of a firm's internationalization strategy. In this respect, three categories of activities can assist in successful market integration: activities that promote knowledge and learning, those that encourage trust and commitment, and those that develop opportunity. Knowledge is a driver of internationalization; however, more than institutional market knowledge is required. Johanson and Vahlne emphasize the role of experiential learning. Firms need to acquire market-specific business knowledge and can only do so by entering the market.Footnote 125 Experiential knowledge is also important in identifying and developing opportunity. The recognition and development of opportunities is an interactive process involving learning and commitment. The flip side of the coin is that it is also important in identifying risk and developing strategies to overcome uncertainty.Footnote 126 The suggestion is that firms need to experience the market to be able to develop strategies to grow in that market. In the case of British fire insurers, it was a combination of enterprise, luck, and resilience that eventually allowed insurers to solidify their networks and build market power.

The key problems that firms had to address in advancing their quest were those associated with market instability and an inability to build effective networks because of issues associated with market knowledge, distance, communication, and moral hazard. Enterprising activities to address these problems were evident in a number of spheres. In the first instance, the mode of entry of many firms was cautious; agents were appointed not only to promote the company's product but also to gather information and provide regular updates on the state of the colonial markets. The home office also provided strict instructions to agents as to how to conduct their insurance business, which population cohorts and areas to avoid, and how to interact with the local industry. Cautious entry was also followed by judicious exit on occasion. Some firms entered and exited multiple times. Their ability to do so reflected the low barriers to entry associated with the market as well as their understanding of the market, which was not yet mature enough to generate a sustainable presence. Difficulties in establishing networks and overcoming the resistance of local suppliers impeded progress. Local firms were found to be “unwilling to give information” and on some occasions “they manifested extreme jealousy” against representatives of British firms.Footnote 127 Barriers to network expansion limited progress at this point.

British MNEs brought with them their knowledge of the British tariff system and its strengths and weaknesses.Footnote 128 In the first instance, companies such as the Royal and Commercial Union were aggressive tariff breakers and deliberately attempted to disrupt market agreements to force local competitors out of business. They were largely unsuccessful in this venture, though; local firms adopted similar strategies resulting in chaotic market conditions for most of the 1880s. In the boom period of that time the results were not as critical as they could have been. The growing economy ensured a sellers’ market. However, this changed with the collapse of the Victorian land boom and the onset of depression in the early 1890s. The contraction of the market in that decade—together with major fire losses, such as the 1890 Sydney Block fire—reinforced in the minds of British insurers the benefits of a collusive agreement. The establishment of the 1897 tariff agreement at the instigation of the major British companies represented a reversal in approach. The success of this agreement was achieved largely with the enterprise of the local managers of British insurers. In this respect, personalities played a key role in promoting MNE interests. The managers appointed by home office directors were chosen carefully. Once established, these men became leading influences in the local insurance community. They became well known in local insurance circles. When the time came to adopt leadership roles within newly formed tariff associations they were well placed to do so.

The final example of enterprising behavior was the use of merger and acquisition strategies to consolidate their market position and extend their selling network. Few Australian firms were in a position to take advantage of this type of tactic. Amalgamation was a trend evident in the home market; British insurers were able to extend this to great advantage in the Australian market. In this case, acquisitions were not necessarily predatory but part of a broader strategy to build sales networks.

The success of enterprising activities could have had a very different outcome if not for the crash of the 1890s, which all but wiped out the local opposition. In this respect, the element of luck played a key role. The collapse of local firms and the small number of new entrants in the following decade allowed British fire offices to step in and fill the void. While it is likely that they would have eventually been able to gain the upper hand in the Australian market, it was a fortunate event from their perspective that hastened this outcome.

Resilience is another feature in the story of British fire insurers in Australia. It was manifest in the ability of these firms to address the problems associated with this distant and underdeveloped market. It was demonstrated in their survival of the disruptions resulting from excessive rate cutting and then market collapse in the 1890s. It was also apparent in their commitment to the establishment and management of an enduring tariff agreement.

The roles played by enterprise, luck, and resilience were not manifest in equal measure. Enterprise was more important in the early stages of establishment, when innovativeness was important in building business and capitalizing on network connections. Resilience was an undercurrent that enabled British insurers to stay the distance and was a constant theme as they endeavored to build market share and influence. The element of luck was a random event that allowed overseas fire insurers to capitalize on the misfortune of locals. In the 1890s they were particularly fortunate in that the vagaries of the economic climate all but wiped out local competitors.

The case of British fire insurers points to the intricacies of MNE expansion. Integration depended heavily on the development of strong networks in the host country. A lack of networks was a hindrance to early ventures. Once established, though, they allowed British MNEs to influence market outcomes, take advantage of market disruption, and exert oligopolistic rule. In this context, the ability of British companies to leverage home country networks and import the regulatory practices employed to control market conduct defined the way in which the industry developed in subsequent decades.

Conclusion

The story of British fire offices in Australia highlights the complex nature of MNE engagement. In this case, these firms were able to successfully capture market share and thereby leave a lasting legacy in the market. Capacity to do so was based on a number of elements promoting market expansion. Some of these related to the organizational strength and enterprising activities of the firm. Others stemmed from an alignment of external factors that favored overseas as opposed to domestic players. Success was not guaranteed or rapidly attained. More than two decades passed before British firms were truly established as market leaders, suggesting that a further element in the mix may be patience. Being prepared to play the long game ultimately paid dividends for MNE insurers. There is still much more to uncover regarding the expansion of companies into overseas markets. This study alerts us to the complexities of individual country experiences. Further research is needed to determine whether this case was unique or if common threads run through the story of MNE insurance.

Appendix 1 Mergers and Acquisitions in the Australian Fire Insurance Market, 1906–1932