Introduction

With the perceived rise of global dangers such as transnational terrorism, nuclear proliferation, organised crime networks and global warming, Ulrich Beck's notion of the world risk society has received increasing attention in International Relations.Footnote 1 Numerous studies have analysed how the changing nature of contemporary risks, the growing concern with the future and the shift from the elimination to the management of risks are changing the ways in which governments deal with security issues.Footnote 2 One area which has so far been under examined is the role of private businesses in the emergence, management and perpetuation of the world risk society. Beck acknowledges that the risk society has reached a new level with the self-referential exploitation of industrial risks. He argues: ‘Modernization risks from the winner's point of view are big business. They are the insatiable demands long sought by economists.’Footnote 3 Yet, focussed primarily on the known risks resulting from modern industrial production, such as nuclear radiation and environmental pollution, Beck neglects the big business of unknown and unknown-unknown risks and risk management in today's hyper-sensitised societies.

This article seeks to address this gap through an analysis of the growing market for private risk management services. It argues that the world risk society is not only the outcome of unintended modernisation dangers, but also a creation of private companies which have commodified risks in Europe and North America since the 1970s. Initially, these businesses focussed on the provision of security as related to physical dangers such as robbery and burglary. In recent years, however, the search for new sales opportunities has encouraged firms across a widening range of economic sectors, from healthcare and food to consumer goods, to indentify a wide variety of risks to the safety and wellbeing of peoples. This expansion of the private market in risks contributes to the perpetuation of the world risk society through its discourse of unknown and unknown-unknown risks. Moreover, it suggests that the economy of the world risk society has become reflexive in a second sense. The first reflexivity concerns the management of the unintended side effects of economic industrialisation. The second, new reflexivity regards the imaginary creation and management of unknown and unknown-unknown risks by a specialised risk industry. Finally, contrary to Beck who believes that the global nature of dangers such as ecological problems, global financial crises and transnational terrorist networks will lead to increasing popular demand for cosmopolitan political solutions, this article suggests that the risk discourses and practices of private businesses offer an alternative vision of the future in which industrialised societies manage their risk through individual consumer choices.Footnote 4 The private risk industry, thus, holds the potential for undermining the political elimination of risks and the end to the reflexive generation of the world risk society.

To support this argument, this article investigates the operation of the risk industry in an area which has figured prominently in the analysis of the world risk society: the terrorism-crime nexus. In this area, the perception of interconnected transnational dangers linking disparate issues such as state failure, terrorism, crime and immigration has replaced the seemingly clear distinctions between internal and external security, and military and non-military threats. Moreover, increasing concern about these issues has facilitated the rise of a huge private security sector in Europe and North America. In the UK alone, security firms had a turnover of over £4 billion in 2006 and some have estimated that the global market for commercial security services would reach $200 billion by 2010.Footnote 5 Notably, private clients buy 70–90 per cent of these services. Focusing on security guarding firms in the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US), the following sections explore how this industry contributes to the emergence, management and continuation of the world risk society through its own autonomous logic and risk management strategies.

Risk society and the market

Building on Beck's Risk Society and World Risk Society as well as Michel Foucault's governmentality framework, the roles and strategies of governments in generating, sustaining and managing risk perceptions and the risk society have received much attention in the analysis of risk in International Relations. On the one hand, such studies have included the investigation of the risk management mechanisms of governmental agencies and international organisations in the ‘war on terror’ and other political issues.Footnote 6 Mike Raco, for example, argues that ‘the concept of risk-environments based on the selective generation of fear has been a central part of government strategies to develop, promote and implement new agendas of economic development.’Footnote 7 On the other hand, research on risk has examined the governmental use of risk discourses and practices to ‘discipline’ populations.Footnote 8 In this sense, Deborah Lupton contends that ‘risk may be understood as a governmental strategy of regulatory power by which populations and individuals are monitored and managed through the goals of neo-liberalism.’Footnote 9

The contribution of businesses to the emergence of risk discourses and the management of risk has so far been under-researched.Footnote 10 Although many authors acknowledge the participation of private firms in the management of risks, the specific mechanisms of the risk industry have not yet been investigated in detail beyond the contexts of insurance and, recently, aviation security.Footnote 11 This gap is particularly surprising since both Beck and Foucault suggest that the modern market economy not only plays a crucial role in the emergence of the risk society, but also operates according to its distinct objectives and autonomous logic.Footnote 12

Beck himself fails to analyse the growing market in risk management in greater detail, despite his argument that the world risk society has its origins in the industrial development from classical to reflexive modernity. In fact, he devotes only two pages in his book Risk Society to the question of how private firms are profiting from the identification, assessment and mitigation of risk.Footnote 13 In his narrative, contemporary risks are real and they have changed:

The risks and hazards of today thus differ in an essential way from the superficially similar ones of the Middle Ages through the global nature of their threat (people, animals and plants) and through their modern causes. They are risks of modernization. They are a wholesale produce of industrialization, and are systematically intensified as it becomes global.'Footnote 14

Businesses have contributed to the creation of these dangers through unconstrained, reckless and globally expanding industrialisation.Footnote 15 In addition to being the result of globalising industrial production, these new dangers are also more dangerous and less predictable than the dangers of the past. According to Beck, the potentially devastating nature of these dangers, their global reach and their incalculability require a new term: risks. Reflexive modernisation, the defining feature of the risk society, is the result of the changing nature of these modernisation hazards. Modernisation becomes reflexive in the sense that it has to deal with the risks that industrial modernisation has produced.Footnote 16

Beck views industrialisation risks primarily as unintended side effects, but his analysis contains the seeds for a broader understanding of the role of businesses in the risk society. In particular, he notes that industrial capitalism is becoming reflexive because ‘risks are no longer the dark side of opportunities, they are also market opportunities.’Footnote 17 Firms can make a profit from managing the risks that they or others have created. Moreover, businesses cannot only manufacture risks in a material sense, but also discursively. Thus, Beck writes: ‘Demands, and thus markets, of a completely new type can be created by varying the definition of risk, especially demand for the avoidance of risk – open to interpretation, causally designable and infinitely reproducible.’Footnote 18 Finally, Beck notes that risk management can take two forms: the first seeks to eliminate the causes of risk in industrial modernisation; the second turns the management of the consequences of risk into a new industry sector.Footnote 19

For the following analysis, these contentions suggest three core hypotheses. Firstly, the private risk industry operates according to its own distinct logic which is concerned with the expansion of consumer demand and profit. Secondly, the concept of risk is particularly suited to this aim because it permits the identification of unknown and unknown-unknown risks through interpretation and imagination. Thirdly, the risk industry can perpetuate the demand for its services by dealing with the consequences rather than the causes of global risks.

Despite these observations, Beck believes that the destructiveness, the global scope and the incalculability of the new risks hold the potential for mobilising public demand for cosmopolitan political solutions rather than a growth of the private risk industry. While he accepts that the world risk society may become differentiated between those who profit from the production and management of risks and those who suffer the consequences, this appears to be merely an intermediary stage.Footnote 20 Beck seems confident that, eventually, societies across the globe will accept that ‘objectively’ the new risks ‘display an equalizing effect within their scope and among those affected by them.’Footnote 21

There are several problems with and limitations to Beck's argument.Footnote 22 The first problem is Beck's usage of the term risk to denote a distinct set of man-made global modernisation dangers. This definition prevents Beck from investigating the particular utility and increasing use of the concept of risk in public, academic and economic discourses. The second regards Beck's argument concerning the origins and future of the world risk society which appears to be shaped largely by recent German history and disregards other societies where a greater emphasis seems to be put on non-political mass responses to the new risks, such as voluntarism, private market solutions and changes in consumer behaviour. Finally, Beck fails to examine in greater detail the mechanisms which contribute to the management and perpetuation of the world risk society. Concentrating on a meta-narrative of historical transformation and change, his research does not answer the question of how the world risk society is sustained. As a result, Beck cannot explain why so far little progress has been made towards the transformation of the world risk society through global cosmopolitan movements.Footnote 23

This article seeks to address these limitations and expand on Beck's limited analysis of the role of businesses in the creation, management and continuation of the world risk society. To do so, it examines in detail the underlying logic, discursive strategies and risk management mechanisms of the private security industry with regard to terrorism and crime.Footnote 24 It is beyond the scope of this article to examine in how far these mechanisms are distinct from or similar to those of other economic sectors such as insurance, healthcare or the environmental industry which have been analysed elsewhere.Footnote 25 However, it hopefully contributes to expanding our understanding of the growing business of risk and presents another step towards a general typology of commercial risk management.

The concept of risk

Especially in his later work, Beck accepts that risks are not merely defined by the physical environment, but also by social construction. Responding to his critics, Beck writes: ‘it is cultural perception and definition that constitute risk.’Footnote 26 However, Beck is sceptical of a purely constructivist framework because it does not allow him to distinguish between real and perceived dangers. His analyses of risk and the world risk society rely ultimately on the contention that material dangers have objectively taken on a new form. This section seeks to illustrate that Beck's focus on the material transformations of global dangers has led him to neglect the question of how the discourse and practices of risk are changing the public perception of these and other dangers. Moreover, the following illustrates that the concept of risk and its particular logic shape how contemporary dangers are addressed.

The investigation of risk as a discursive concept also suggests a modification to the understanding of the risk society. If it is not (only) the nature of the danger which has changed, but (also) their analysis through the concept of risk, the relationship between the emergence of global modernisation risks and the risk society changes. Instead of being (exclusively) the result of the material transformation of ‘real’ dangers, the defining feature of the risk society becomes its obsession with risk. In this interpretation, the risk society is characterised by a growing concern with future risks and the proliferation of institutional and private practices of risk management.Footnote 27

Known, unknown and unknown-unknown risks

Risk has been described as ‘a multidimensional concept whose definition and articulation are critically dependent upon the objectives and rationales of those using it to promote their own agendas.’Footnote 28 This raises the question of who benefits from the emergence of risk as a central concept in the discourse on security. In order to understand the particular characteristics and utility of the concept of risk, it is first necessary to note its definition. Against Beck, predominant political, economic and academic parlance defines risk not as a distinct type of modernisation danger, but as a measure of the level of insecurity calculated by the probability of a hazard multiplied by its impact.Footnote 29 Since past experience provides the best basis for the inference of both the potential impact and the probability of a danger, the less frequent a danger, the more difficult it becomes to assess the associated risk. For the purposes of this article, it is useful to distinguish between three levels of risk on a continuum of frequency, calculability and familiarity with certain dangers: known, unknown, and unknown-unknown risks.Footnote 30

Known risks denote dangers affecting peoples' lives on a permanent or regular basis. They are ‘known’ if a significant number of people has personally observed or experienced these dangers or if there is a large amount of public and verifiable information about them. Before the rise of the concept of risk in the jargon of security experts and the general public, known risks used to be referred to as ‘threats’. Threats denote dangers which have been clearly identified.Footnote 31 Threats exist in the present rather than the future.Footnote 32 A known set of triggers will lead to instantaneous harm. During the Cold War, for example, the nuclear weapons of each superpower were conceived of as a threat. Each side had verifiable information about the number, direction and lethality of the other's nuclear weapons and declared policies of mutual destruction or first use confirmed their deployment under specified circumstances. In sum, the notion of ‘known’ risk or threat emphasises simultaneously the certainty of a danger and its imminence.

In the second category are ‘unknown’ risks. These risks are related to dangers which can be calculated in terms of their probability and impact on the basis of past records. However, it is unknown where exactly and with what consequences they will occur next. Unknown risks are within the individual experience of some people, but not of entire populations, and are exemplified by dangers such as terrorism, robbery or traffic accidents. Unknown risks refer to the principal definition of risks as calculable, but unknown future dangers. While threats will lead to harm under certain conditions, unknown risks can lead to harm at any time.

The third category is ‘unknown-unknown’ risks. They concern dangers with a very low probability or where the probability is unknown because there are no previous experiences of such hazards. Unknown-unknown risks are incalculable future dangers. Unknown-unknown risks are also outside the individual or collective experience of anybody. Instead, unknown-unknown risks are identified through speculation. Rather than being based on the statistical analysis of past incidents, they are efforts to explore the future through imagination.Footnote 33 Despite a low probability, unknown-unknown risks can be high on public and political agendas because of their equally speculative, devastating consequences. These imagined consequences gain credibility through ‘worst-case narratives and disaster rehearsals.’Footnote 34 Examples of unknown-unknown risks include the danger of new chemical or biological weapons or the development of new strategies of destruction by transnational terrorists.

Due to these characteristics, the transition from the concept of security to risk in contemporary discourses and practices has several important consequences. Firstly, the emergence of risk as a central concept has made possible the shift from the known threats of the Cold War era to today's concern with unknown and unknown-unknown risks with serious implications for the provision of security. While the realist concept of security implies that dangers can be eliminated, the probabilistic concept of risk suggests that insecurity can only be managed. A notion of security building on risk means that security can never be attained. Zero risk does not exist. Therefore, the concept of risk guarantees constant demand. Risks require permanent surveillance, analysis, assessment and mitigation.

Secondly, the concept of risk makes possible the discourse of unknown-unknown risk. It allows demand for security management to expand from personally known threats and calculable unknown risks to risks that exist only in the imagination. The potential range of imaginable risks is infinite. Whereas threats can be personally observed and experienced, and unknown risks can be statistically assessed, unknown-unknown risks are beyond knowledge and evaluation. The concept of risk, thus, allows and even legitimises the inflation of risk perception beyond the apparent to the inconceivable in the name of precaution.

Thirdly, since unknown and unknown-unknown risks are outside personal experience, the concept of risk leads to a growing dependence on experts for the identification, analysis and assessment of risks. The world risk society needs experts to tell it what it should fear. Moreover, there is no way of challenging the risk assessments of experts who inform the public of unknown and unknown-unknown risks. Due to the futurity of unknown risks and the incalculability of unknown-unknown risks, it is impossible to prove experts wrong. In a reversal of Beck it can be argued that expert prognoses of risk and insecurity cannot be refuted even by the absence of actual accidents because the risk discourse is based on a set of speculative assumptions and moves exclusively within a framework of probability statements.Footnote 35

Finally, the latter makes it difficult to evaluate of the utility of professional risk management. Since risks happen in the future, their non-occurrence can be due equally to faulty risk assessment or successful risk mitigation. Effective risk management is, by definition, a non-event.Footnote 36 The concept of risk, therefore, permits the inflation of demand by focussing on the input of risk management and not on its results. In the logic of risk, the more unknown and unknown-unknown risks are identified, analysed and mitigated against, the less likely they are to happen.

Returning to the question who benefits from the discourse of risk, a multitude of studies have illustrated that governments have used the notion of risk to control and gain the support of their populations.Footnote 37 However, it has been little noted that for democratic governments the concept and discourse of risk can be a double-edged sword. While it can increase executive control over policies and populations, the discourse of risk and fear can also undermine electoral trust in governments if the risks prove unfounded or if governments fail to appear to restore order and security. Governments who use the concept of risk to justify their policies walk a fine line. Although they can exploit public fear for political purposes, these governments have to convince their populations that the risks are ‘real’ and addressed effectively if they want to be re-elected. Moreover, governments have limited resources. Increased risk perception leads to demands for improved public security measures such as additional police patrols, but tax increases to fund such measures are often unpopular.

The intervention in Iraq illustrates this dilemma. Tony Blair's popularity suffered permanently from public scepticism regarding the level of risk posed by Iraq and the subsequent failure of the allied forces to find evidence of weapons of mass destruction (WMD).Footnote 38 In the US, George W. Bush's assertion of the risk of global terrorism in Iraq and Afghanistan helped him to remain in power after the 2004 presidential elections. However, Bush's subsequent inability to establish peace in Iraq and the rising cost of the occupation contributed to undermining popular support for his party resulting in the election of a Democrat majority in both Houses of Congress in 2006 and Barack Obama for president in 2009.

The private risk industry has no such problems. For businesses, the fact that risks can never fully be eliminated promises insatiable demand. In fact, private security firms exacerbate risk perception in order to sell their services.Footnote 39 The fact that risks cannot be eradicated is not a problem because public expectations regarding the capabilities of businesses and states differ markedly. While the public hires firms to micromanage their personal risks, it expects their governments to address and eliminate risks at a macro-level. The ‘consumer’ accepts that private business solutions to risks are only temporary and individual, while the ‘citizen’ demands that the government develops permanent and collective responses to the new risks. Consumers would also never expect that private firms provide for their security unless they pay them. Conversely, many citizens seem to believe that tax cuts and increased national and international security measures are compatible. While citizens are likely to vote a government which fails to address perceived risks out of office, consumers who have become targets of terrorist attacks or burglaries are advised to upgrade their private security by buying more advanced technologies and more extensive services.Footnote 40 Most importantly, businesses sell security, while governments have to pay for it. Firms do not have to balance manufactured increases in risk perception against existing or potentially available budgets. On the contrary, rising private risk perception increases business profits.

Risk perception and the culture of fear

The industry's ability to profit from risk management provides it with a vested interest in the creation, expansion and continuation of the demand for its services. Fear is one of its strongest marketing tools.Footnote 41 The emergence of a ‘culture of fear’ in risk societies directly benefits the private risk industry. This culture of fear is created through the continuous discursive rehearsal of alleged dangers in all aspects of life.Footnote 42 In the UK and the US, the terms ‘risk’ and ‘at risk’ are thus ‘used in association with just about any routine event.’Footnote 43 Due to the lack of personal experience of unknown and unknown-unknown risk, mass mediated and expert interpretations of potential dangers play a critical role in the manufacture of private risk perception. Unfortunately, the old adage ‘bad news is good news’ applies to the mass media as well as the risk industry. The practices of the media and the risk industry, thus, support each other in creating a spiral of perceived risk escalation. Industry experts lend credibility to bad news in the media, and bad news in the media generates rising private demand for commercial risk management.

The impact of media and industry advertisements on fear is well researched.Footnote 44 Although individual risk perception varies considerably depending on age, gender, class, living area or culture, extensive press coverage of specific dangers or risks increases fear independently of other factors. A study of crime reporting and fear of violence in Finland observed that already the indirect exposure to crime news in the form of ever present tabloid front pages and billboard advertisements in urban landscapes contributes to growing fear among citizens.Footnote 45 Personal risk perception increases in direct proportion to the exposure to media reporting of crime, and the reading of front page news in tabloid papers is directly related to attempts to avoid risks. In fact, empirical research has demonstrated that all forms of threat reporting, including about traffic accidents or environmental degradation, contribute to people's perception of ‘life as “scary”, dangerous and fearful.’Footnote 46

It is little surprising that in most industrialised nations the media and marketing discourse on risks, public anxiety and private security industry turnover have increased simultaneously since the 1970s. The statistic risks of terrorist and criminal attacks have decreased for much of the past three decades, but Western societies are more fearful than ever. In the US, key newspapers' association of fear with violence and crime increased six-fold between 1984 and 1999, that is, before 9/11.Footnote 47 The discourse of fear ‘resonates through public information and is becoming a part of what a mass society holds in common: We increasingly share understandings about what to fear and how to avoid it.’Footnote 48 Similarly, Furedi finds that the use of the term ‘at risk’ in UK newspapers increased nine-fold between 1994 and 2000.Footnote 49

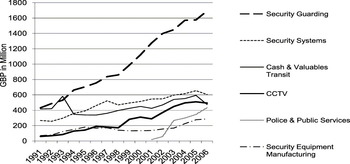

Risks appear all pervasive. A content analysis of the websites of British security guarding firms, which have seen the highest increases in turnover over the past decades (see Figure 1), reveals a range of discursive strategies supporting this impression.Footnote 50 Foremost are statements highlighting the multiplicity of unknown and unknown-unknown risks everybody faces today. As one company puts it ominously, ‘Your business operation faces a growing number of risks from an array of sources.’Footnote 51 Terrorism, crime and other unnamed dangers merge into a seamless web of a complex and interconnected security risks. Thus, another private security firm suggests, ‘the risk of terrorism and organised crime sits alongside the exposure to internal breaches of security’,Footnote 52 while a third observes ‘the ever-present risks of fire, flood, theft, vandalism, terrorism and occasionally, industrial espionage.’Footnote 53 A second marketing strategy highlights the actuality and changing nature of these security risks. References to ‘recent world events’, ‘the current climate’ and ‘the modern world’ suggest that contemporary dangers are new, pressing and requiring immediate action.Footnote 54 Finally, against statistical evidence, many private security firms assert the ‘increasing number of crime related incidents’Footnote 55 and a growing terrorist threat ‘which may involve introducing measures that have never been considered before.’Footnote 56

Figure 1. British security industry turnover.

The combination of media and industry claims regarding the heightened risk of terrorism and crime has amplified public fear and demand for private security services. An Ipsos MORI poll conducted in 1999 found that 25 per cent of Britons worried permanently about a potential burglary, and 15 per cent had acquired professional home security advice.Footnote 57 A survey in 2006 showed that Britons were more concerned about crime and violence than citizens in the US and other major European countries. In the UK, 43 per cent mentioned crime and violence as the most pressing concern of their country, compared to 40 per cent in France and Italy, 31 per cent in Spain, 27 per cent in the US, and 21 per cent in Germany. Britons were also the least confident in their government's ability to deal with these problems with 29 per cent, compared to 57 per cent in Germany, 48 per cent in Italy, 44 per cent in France and the US, and 35 per cent in Spain.Footnote 58

The same time period that has seen the rise in public fear and risk perception has witnessed a massive expansion of the private security industry. Between 1991 and 2005, the turnover of private security companies in the UK rose by no less than 330 per cent, that is, an average of 23 per cent annually. In the US, the average growth of the private security industry lay by 8–10 per cent per year.Footnote 59 By comparison, the UK manufacturing sector only expanded on average by 0.5 per cent and even the IT sector grew only by 6–8 per cent annually during the same period.

While Beck believes that the inherent incalculability of global modernisation risks allows people to challenge the risk assessments of experts, he also sees the danger that an inability to agree on the ‘real’ risks ‘throws the door open to a feudalization of scientific knowledge through economic and political interests and “new dogmas”.’Footnote 60 People might be able to resist the discourse of fear by pointing out the unverified and complex assumptions of expert calculations regarding unknown and unknown-unknown risks; but to do so is in itself a risk which people might not want to take. A precautionary response becomes even more likely if, as the media and business advertisements do, risks are not related to peoples themselves, but to those for whom they care or are responsible.Footnote 61 People might be willing to take risks for themselves, but they are disinclined to accept risks for those they love or are accountable for. References to one's children, family or employees permeate the discourse on risk. The next section investigates how the specific logics and mechanisms of private security management build on the concept of risk and the culture of fear to further expand the demand for its services.

Commercial risk management

Private businesses not only contribute to the emergence of the world risk society through discursive strategies, they also offer to manage the risks that they identify. However, as the concept of risk employed by the private security industry magnifies and sustains demand, so does commercial risk management. The demand inflating logic and mechanisms of private risk management can be observed in three areas: risk identification, risk assessment and risk mitigation.Footnote 62 Risk identification concerns the detection of potential dangers and their targets. Risk assessment calculates the relative probability and impact of different types of dangers and seeks to establish priorities for risk mitigation. Finally, risk mitigation aims to prevent or limit the damage of a hazard. The following sections examine each in turn.

Risk identification

Beck believes in the collectivising capacity of global risks such as transnational terrorism and environmental degradation. According to him, fear will create solidarity and lead to the formation of new cosmopolitan political communities to collectively address common dangers.Footnote 63 Yet, in the UK and the US, a frequent response to the rise in risk perception and the emergence of cultures of fear appears to have been the alienation of individuals from their social environments. Rather than finding a new sense of solidarity, many people seem to shut themselves off, both physically and psychologically, from suspect or simply unknown ‘others’ within gated communities, purportedly safe housing districts, private schools and locked cars.Footnote 64 Beyond the general individualisation of modern society, one of the origins of this behaviour appears to be the differences in personal risks and individual responsibility emphasised in private industry discourses and practices.Footnote 65 Notably, the private industry portrays risks as personal characteristics and pro-active risk management as the responsibility of everybody.Footnote 66

The individualising logic of commercial risk identification plays a crucial part in increasing private consumption of security services by attributing risks to persons rather than collectives. Although probabilistic risk statistics concern collectives ‘this information is conveyed as exact, certain and tailored to the individual.’Footnote 67 The media and industry abound with statistics, tests and services offering personal risk profiles depending on age, sex, occupation and other factors. These risk profiles generate the impression that everybody's risks are distinct and that, therefore, they require individualised solutions. Private security and other risk management firms present even inherently collective dangers as personal and selective. Their risk identification strategies transform Beck's ‘de-bounded’ modernisation risks, such as nuclear waste, genetic modification and terrorism, into bounded personal risks, depending on whether a person lives near a nuclear waste disposal site, eats genetically modified food or flies with American airlines.Footnote 68

The advertisements of private security firms in the UK illustrate the individualising logic of commercial risk identification. As one company proclaims, ‘no two businesses security needs are identical.’Footnote 69 Implying that governments and the public police cannot take these differences into account, private security companies promise to analyse each individual clients' particular risks and provide ‘bespoke’ services, which can be ‘tailored to clients' requirements and can be delivered whenever and wherever they are needed.’Footnote 70 In fact, the assertion that the security risks of every customer are distinct is one of the most widely-found statements on security firms' websites in the UK.Footnote 71 The American Security Industry Association agrees that the ability of private security firms to cater to the divergent needs of individual consumers is one of the key reasons for the expansion of the private security sector.Footnote 72

Conjoined with the individualisation of risk is the logic of individual responsibility for containing them. Where risks are ascribed to persons rather than societies and states, the individual is seen not only as able to, but also as responsible for managing their risks.Footnote 73 The rise of neo-liberalism since the 1980s has facilitated this responsibilisation of citizens at the same time as it has favoured private market over public service solutions to social needs and risks such as healthcare, transport and energy. Individualised responsibility detracts attention from collective and political responses to risks and focuses on how people can improve their personal risk profiles through consumer choices. As Raco notes, ‘insecurity becomes associated with individual deficiencies, rather than broader structures.’Footnote 74 Health risks such as cancer become the responsibility of individuals who are encouraged to lower their body weight, eat food rich in anti-oxidants, take vitamin supplements and exercise instead of the concern of governments which could be encouraged to investigate and regulate the radiation emitted by mobile phone masts, pesticides in drinking water and hormone additives in meat.Footnote 75

Also with regard to terrorism and crime, government discourses suggest the responsibility of potential victims to protect themselves and, thus, promote commercial security solutions.Footnote 76 The British police, for example, seek to contain the risk of crime by advising people to lock their doors, sling handbags across their bodies and not to walk home alone at night.Footnote 77 Even the globalising danger of transnational terrorism becomes a personal responsibility. Thus, UK government recommendations regarding a WMD attack by terrorists have been ‘skewed towards the individual – “what can you do to protect yourself and your community against risk”’.Footnote 78 In the same manner, Metropolitan police told local businesses after the London attacks to take action to step up the safeguards for their premises.Footnote 79 Some years earlier, the US government's recommendation that citizens could protect themselves against a biological weapons attack by sealing their windows with tape and plastic sheets let to panic buys and stockpiling of these items.Footnote 80

In addition to personal risk profiling, individual responsibility for risk management arises from a number of factors in private security industry risk identification discourses. Foremost is the alleged failure of government agencies to provide efficient, effective and accountable risk management. As Intacept Security Ltd. writes, ‘we know Police resources are being stretched daily and their attendance at a premises [sic] depends greatly on operational commitments.’Footnote 81 Moreover, private security companies assert that individual responsibility to protect against risks is an issue of corporate governance and duty of care, increasingly acknowledged as ‘legal and moral obligations’.Footnote 82 Lastly, there is the private risk industry itself which, in the guise of insurance companies, requires specific security measures or offers lower premiums in return for precautionary action.Footnote 83

The demand expansion underlying the individualising and responsibilising logic of the private security industry also characterises the mechanisms used for risk identification such as profiling and risk surveys. Typically employed at the first stage of a risk management consultation and offered by some companies as a free service, profiling and risk surveys promise to pinpoint the particular risks faced by individual customers and encourage them to take precautionary measures.Footnote 84 Both mechanisms, thereby, increase the influence of industry experts on risk identification. At the centre of their analyses stands the ‘expertise’ and ‘specialised knowledge’ of risk professionals regarding ‘realistic’ unknown and unknown-unknown risks rather than the customer's personal experience of known dangers.Footnote 85 In fact, the explicit aim of risk surveys is to inform clients about potential and future risks they have been unaware of.Footnote 86

Private security firms also perpetuate the demand for commercial risk identification by emphasising the constantly shifting nature of risks: ‘continuous evaluation enables us to anticipate and respond to the rapid changes to security risks that characterise clients' operating environments.’Footnote 87 In addition, they highlight the changing needs of the customer. As Group 4 Securior (G4S), the largest private security company in the world asserts, ‘As your business changes, so does your security risk profile.’Footnote 88 Risk identification is never complete. Instead, the websites of private security firms stress the need for a regular review of a client's risks. ‘The assessment of risk is not a one-off event; it is an ongoing process of evaluation and review, and Pilgrims will work with you as your operations develop.’Footnote 89 Many firms recommend security ‘health checks’ on an annual basis.Footnote 90 Ironically, research has shown that risk analyses tend to increase fear rather than reduce it and lead to increased demand for assurance through regular check-ups.Footnote 91

Risk assessment

Risk identification frequently merges with the subsequent assessment of risks in terms their relative probability and impact in order to establish priorities for intervention. Nevertheless, this stage of commercial risk management has a number of distinct logics and strategies. While governmental risk assessment has been linked to ‘zero risk, worst case scenario, shifting burden of proof and serious and irreversible damage’, the primary risk assessment logics of the private security industry revolve around the concepts of vulnerability and risk minimisation.Footnote 92 Security surveys and penetration testing serve to implement these logics, while a discourse of risk management as an ‘investment’ justifies the additional expenses.

The logic of vulnerability deserves particular attention because it expands private demand for security services by reinforcing the individualisation and responsibilisation of commercial risk identification. The concept of vulnerability does so by shifting the central focus of risk assessment from the danger to the potential target. Conventionally risks are calculated and compared in terms of the statistical frequency and magnitude of a particular danger for a given collective and time period. The US State Department, for example, measures the national and global risk of terrorism as the number of attacks and casualties per country each year.Footnote 93 These statistics show that the risk of becoming a casualty in a terrorist attack is extremely low in most North American and European countries.

The focus on vulnerability changes this calculation. Instead of the statistical analysis of the danger, it focuses on the characteristics of the potential target to estimate the likelihood and probable impact of a danger. Specifically, it measures the level of risk in terms of the exposure and weaknesses of the client defined by his or her behaviour and ability to repel or survive an attack. In the case of terrorism, the logic of vulnerability suggests that, although the collective risk of terrorism is negligible, the industry can still present it as a high personal risk because of the lifestyle and lack of protection of the individual.

In some cases, the logic of vulnerability even suggests that the probability and magnitude of a risk increases because of the weaknesses of the potential target. According to this argument, a client who is seen to be vulnerable encourages a perpetrator to attack. Individuals who do not reduce their vulnerabilities are responsible for their own harm. In the literature on crime and policing, this transfer of responsibility for crime victimisation to the individual has characterised the concept of situational crime prevention. The situational crime prevention approach contends that individuals can reduce their vulnerability to crime by increasing the cost and decreasing the rewards for the potential perpetrator.Footnote 94 The political and industry discourses on crime prevention, therefore, emphasise the responsibility of the victim for collective crime levels.Footnote 95 As a result, some, like the former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, ‘[blame] a large proportion of crime on the victims' carelessness.’Footnote 96 Situational crime prevention implies that it is not external factors such as poverty or the childhood experiences of the perpetrator which lead to crime, but the failure of the individual victim to take precautionary measures. In effect, the target is portrayed as causing crime by its vulnerability.

A second logic of commercial risk assessment is the concern with minimising risk. This logic explicitly recognises that zero risk does not exist. Nevertheless, it increases demand for private security equipment and services by directing the evaluation of risk away from the questions of the probability and impact of known dangers toward the aim of minimising even unknown and unknown-unknown risks. Although the objective of risk assessment is to establish priorities for risk mitigation and the risk industry does indeed make such recommendations, the logic of risk minimisation encourages the elimination of any possible exposure or weaknesses. Intacept Security Ltd., for example, offers to carry out an analysis of ‘any vulnerable points’.Footnote 97

The preoccupation of commercial risk assessment with vulnerability and risk minimisation features widely in the advertisements of private security companies in the UK. One company website brings both together: ‘Our focus is on assessing your premises; reviewing current security provision and identifying the weak areas criminals are likely to target. By minimising pre-existing security risks we can develop an appropriate method of dealing with criminal activity […]’.Footnote 98 These advertisements also highlight the utility of commercial security surveys or audits and penetration testing as means for the assessment of vulnerabilities. The Pilgrims Group claims that through a ‘thorough survey or audit we will present a realistic and holistic analysis of your current security strengths and weaknesses.’Footnote 99

Interestingly, the private security industry justifies its logics of vulnerability and risk minimisation through a discourse of risk management as an ‘investment’ rather than an expense.Footnote 100 It suggests that the more a customer spends on risk management, the more he or she is likely to save. According to the websites of numerous private security firms, such an investment can ‘pay for itself’ either through lower insurance premiums, avoided losses and harm, or greater efficiency because clients are freed from ‘the time-consuming and costly day-to-day responsibility’ of their own risk management.Footnote 101

Risk mitigation

The third stage of private risk management is risk mitigation, that is, efforts to prevent or reduce damage caused by risks. In the practices of the private security industry, it is shaped by three logics. The first is the management of consequences rather than causes. The second logic is risk mitigation as assurance. The third is risk mitigation as a continuous process. All three use the language of unknown and unknown-unknown risks to perpetuate the demand for commercial risk mitigation by asserting that risks can never be fully eliminated, because their causes are beyond comprehension and intervention. Instead, these logics promote perpetual risk mitigation which offers reassurance by claiming to minimise their clients' alleged weaknesses and vulnerabilities. Moreover, they are implemented through demand-expanding strategies which present and provide security as an individualised, excludable service rather than a collective good.

The concern with consequences rather than causes is, according to Beck, one of the key features of commercial risk management. Thus, Beck observes that the private industry only

‘copes’ with the symptoms and symbols of risks. As they are dealt with in this way, the risks must grow, they must not actually be eliminated as causes or sources. Everything must take place in the context of a cosmetics of risk, packaging, reducing the symptoms of pollutants, installing filters while retaining the source of the filth. Hence, we have not a preventive but a symbolic industry and policy of eliminating the increase in risks.Footnote 102

The concern with consequences highlights that risk mitigation is not always or necessarily preventative.Footnote 103 While many businesses claim to prevent risks, their assertions are usually misleading. One example is the alleged prevention of breast cancer through commercial genetic testing. As Press et al. point out, this promise is disingenuous because, ‘science has not “cured” or “prevented” breast cancer.’Footnote 104 What firms really offer is the detection of purportedly ‘risky’ genes and the pre-emption of their potential consequences through mastectomies. Not only are the claims of private businesses deceptive, they also shift the focus from addressing the collective causes that can trigger those genes to develop into breast cancer such as the spread of pesticides and hormones in food and water to the individual susceptibility to and management of these risks.

To clarify such misunderstandings, it is necessary to distinguish between precaution and prevention. Due to the concern about the future inherent in the concept of risk, all risk mitigation can be said to be precautionary by definition. They all involve ‘measures taken in advance to avert a possible evil’.Footnote 105 However, precaution is not synonymous with prevention. According to both Beck and Press et al., the term prevention implies an action that eliminates the causes of a risk and, thus, the risk itself. In this sense, most commercial risk mitigation might be precautionary, but it is rarely preventative because it attempts merely to minimise the potential consequences of a danger for an individual client.

In the discourse of the private security industry, the preoccupation with consequences rather than causes is justified by the complexity of contemporary security risks, such as global warming and the development of chemical and biological weapons. While the origins of threats are clearly identifiable, those of unknown and unknown-unknown risks are either obscured by multiple and complex causalities or the lack of data and experience. In the absence of any definitive understanding of the root causes of contemporary risks, the industry can only offer to mitigate their potential impact. Another factor, however, is the public goods nature of preventative risk mitigation.Footnote 106 Firms find it difficult to make potential customers pay for such services because of a free-rider problem. The problem is that the elimination of risks such as terrorism or global warming is non-excludable, that is, it is not possible to exclude people from its benefits. Since people can ‘free-ride’ on such services, they have no interest in paying for them and firms will fail to cover even their own cost. The mitigation of consequences on the other hand is excludable since it regards the reduction of the vulnerabilities of potential targets. It can be made to benefit only paying customers and, thus, can be sold for profit.

Since private risk management firms do not eliminate risks, the second logic underlying commercial risk mitigation is assurance. The risks remain, but the discourse and services of the industry assure clients that they have done all that is possible to protect themselves. Thus, many measures against crime aim to reduce fear rather than crime itself.Footnote 107 This includes technologies such as panic buttons, burglar alarms and CCTV cameras. The phrase ‘peace of mind’ is the single most frequent statement on private security industry websites after references to the ‘bespoke’, that is, individualised, nature of commercial risk management.Footnote 108 Few of these risk mitigation mechanisms have a measurable effect on crime rates.Footnote 109 CCTV cameras, for example, have lost their utility as a deterrence mechanism in many areas because the poor quality of the videos, the complexity of the visual data which so far resists computerised analysis and the huge amount of the material prevent their effective use in the prosecution of terrorists and criminals.Footnote 110 Nevertheless, the turnover of the British CCTV monitoring industry increased nearly tenfold from £59 million in 1991 to £509 million in 2005. Ironically, measures designed to reassure people can amplify their fear. Extensive security arrangements such as pervasive monitoring and increased patrols can create the image of a dangerous environment making people feel unsafe in the first place.Footnote 111 The demand for assurance, thus, becomes self-perpetuating.

The third logic of risk mitigation follows directly from the focus on consequences and assurance: the logic of permanent precaution. Since risks always exist and it is impossible to predict when they strike, clients require continuous assurance and risk mitigation 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Redguard Security, for example, writes, ‘With your peace of mind our focus […] our procedures provide you with a service that is continuous, monitored and recorded to ensure true 24 hour security […]’.Footnote 112 In short, as another company promises, ‘We will be there, whenever and wherever you need us.’Footnote 113

The logic of permanent precaution also derives from the argument that risk mitigation strategies and equipment need regular updating. Man-made risks such as terrorism and crime are presented as ‘moving targets’ which adapt to and actively seek to overcome established risk mitigation products and services. According to Hart Security ‘criminal activity is usually only one step behind’ the latest technological advances,Footnote 114 and Allander Security warns that ‘As tagging and surveillance systems develop, so to do the methods used by criminals to outwit supposedly foolproof systems.’Footnote 115 This means that not only do security services have to be supplied on a continuous basis, but also that technological equipment such as burglar alarms and security barriers have to be replaced frequently with new models.

The strategies employed by the private industry directly reflect the above. Analytically, one can differentiate between at least six possible risk mitigation strategies: prevention, pre-emption, avoidance, deterrence, protection and resilience. Due to the specific logics of the risk market, however, private security firms tend to prefer some over others. The most widely offered commercial risk mitigation mechanisms are deterrence and protection. Both are excludable, focus on consequences, provide assurance and require permanent services. Less frequent are avoidance and resilience. They meet the first three criteria, but do not usually lead to long-term dependencies on private risk mitigation. Finally, preventative and pre-emptive strategies are virtually absent from commercial risk mitigation because they match none of the logics described above.

Preventative risk management may be understood as goods and services which target the underlying root causes of a risk. In the case of terrorism, this might include addressing the grievances of terrorist groups and their perceived exclusion from legitimate political processes. With regard to crime, it can involve the reduction of poverty or drug dependency. As has been argued above, private firms are unlikely to offer truly preventative services to private customers because the benefits of eliminating a risk are non-excludable and, therefore, impossible to sell for profit. The American Security Industry Association, for example, lists 26 market sectors, including burglar alarms, CCTV, computer security, mobile security, personal security devices and outdoor protection, but none refers to services which address the origins of dangers.Footnote 116 In most cases, preventative measures are left to governments which can fund them through general taxation.Footnote 117

Pre-emptive strategies can be defined as those which destroy the danger before it takes effect. This can be achieved either by eliminating the potential perpetrator or source, such as a terrorist or WMD, or by erasing the potential target, as in the case of pre-emptive mastectomies mentioned above. Since both measures assume a danger (and guilt) before it materialises and can be very destructive, neither states nor businesses like to turn to pre-emption. In fact, most societies prohibit private individuals and businesses from taking pre-emptive measures against security threats emanating from other human beings. Private security firms often emphasise that their services are purely defensive, that is, that their personnel only shoot in self-defence or in defence of their clients.Footnote 118 Even less radical pre-emptive actions such as the identification of ‘risky’ employees or prohibitions against the carrying of weapons in shopping malls, are problematic because they infringe upon peoples' rights and freedoms.

While pre-emption primarily targets potential perpetrators, avoidance strategies encourage clients to modify their own behaviour in order to reduce their risks. Avoidance strategies follow from the logic of risk minimisation and the management of consequences. They can be an important mechanism where deterrence and protection are likely to fail, such as regarding terrorists who are unlikely to respond to threats of imprisonment or death. Nevertheless, only a small number of private security firms promote avoidance as a suitable risk mitigation strategy and offer related services such as risk consulting and training. ArmorGroup, is one of the few firms to teach its clients ‘to recognise and avoid potential threats and equip them, if necessary, to respond to terrorist actions, kidnappings and violent crimes.’Footnote 119 Admittedly, clients frequently hire private security firms because they cannot avoid a risk.

The two primary commercial risk mitigation strategies are deterrence and protection. Both show the greatest convergence with the logics of commercial risk mitigation. Deterrence mechanisms seek to increase the cost or decrease the benefit of carrying out an action that entails the risk of harm to their clients. Since deterrence relies on the perception of the potential perpetrator, it is only suitable for risks of human origin. In the case of terrorism and crime, private industry deterrence typically operates in conjunction with the judiciary. Specifically, private firms attempt to increase the likelihood that a perpetrator will be detected, apprehended and successfully prosecuted. There are a whole range of services and equipment aiming to deter potential attackers or criminals, including static guards, mobile patrols, CCTV surveillance, security checks at buildings and airports, intruder alarms, cash and property marking, access control technologies and IT security solutions. The largest increases in turnover since 1991, however, have been seen in two services: manned security guarding and remote CCTV monitoring (see Figure 1). As 4 Forces Security advertises, mobile patrols are a ‘high visibility security service that acts as a powerful deterrent’Footnote 120 and Abal Security promises that contract security guards can ‘deter high risk situations, where you may be under threat of terrorist attack or armed robbery.’Footnote 121 Notably, these two services are the most demanding in terms of 24/7 provision, yet do the least to address the root causes of security risks.

Some deterrence mechanisms such as security guards also have a protective function, that is, they seek to minimise the potential harm done to clients or their property. Protection usually works by reducing vulnerabilities or increasing defensive capabilities of a customer. Since protection only applies to the specific client who is safeguarded, it is the most excludable security mechanisms of all. While deterrence strategies such as security patrols can have positive effects for those in its vicinity, protection can be restricted to single individuals such as in the use of bodyguards or body armour, to properties such as perimeter fencing and patrols for gated communities, shopping malls or business estates, or to virtual defences such as electronic ‘firewalls’ for computer systems. The popularity of protective mechanisms with private businesses appears to lie in its close match with the underlying logics of commercial risk management, including the individualisation of risk and the responsibilisation of potential targets, the concern with vulnerabilities and risk minimisation, and the emphasis on assurance and the perpetual mitigation of consequences. The extent to which the UK and the US have become dependent upon commercial protection is staggering. The 2004 Report for Congress ‘Guarding America’ pointed out the increasing reliance of the US on private protection, observing that 87 per cent of security guards employed to safeguard infrastructure against terrorist attacks worked in the private sector.Footnote 122

The last risk mitigation strategy regards the resilience of potential targets. Resilience denotes the ability to carry on or recover after harm has been done. Since resilience limits rather than expands demand, private security firms typically promote resilience as an additional service in case deterrence or protection fails. To enhance resilience, private security firms suggest a number of strategies. One strategy relies on educating clients how to respond to attacks by setting up ‘incident management and crisis response’ procedures and executing ‘security exercises and drills’.Footnote 123 Another expands clients' backup or redundant networking capacities in order to enable them to continue communicating and quickly access alternative resources if their primary capabilities are compromised. As ECA Resilience and Security Consultancy argues: ‘Only diversity ensures the resilience essential to your communications’,Footnote 124 while Red Cell Security emphasises improvements to ‘supply and distribution chains.’Footnote 125 Finally, firms offer to help their clients to recover from an attack with ‘psychological trauma support’ and other services.Footnote 126

Together these strategies illustrate that commercial risk mitigation works through a distinctive set of logics and mechanisms which serve to expand the demand for private security services. It is thus not only the concept of risk and the emergence of a culture of fear which has contributed to the rise and perpetuation of the world risk society, but also the reflexive management of risk through a growing industry. In the area of terrorism and crime, this industry has involved the creation of a global private security sector which offers to minimise the risk to private clients who increasingly doubt the capabilities of governments to protect them against national and transnational dangers. However, at the same time as they assure their clients, the logics and mechanisms of private security management further undermine the belief in political responses as the discourses and practices of private security firms suggest that contemporary security risks are individual and diverse and can only be effectively contained by ‘bespoke’ commercial services.

Conclusion

The concept of the world risk society has gained increasing popularity in recent years. However, the features and origins of the world risk society remain the subject of controversial debate. While Beck envisages the rise of global political movements which will challenge the nation-state and promote the emergence of a cosmopolitan security community, his critics contend that the emergence of ‘new’ risks has led to the strengthening of the central authority and powers of the state. This article has sought to present another perspective. Building on the work of Beck and others, it has examined the role of private businesses in the creation, management and perpetuation of the world risk society. Focussing on the private management of security risk with regard to terrorism and crime in the UK and the US, it has observed that the replacement of the concept of security with risk has permitted private firms to identify a growing range of unknown and unknown-unknown dangers which cannot be eliminated, but require continuous risk management. Using the discourse of risk and its strategies of commercialised, individualised and reactive risk management, private security companies have thus contributed to the rise of a culture of fear in which the demand for security can never be satisfied and guarantees continuous profits. The analysis concludes by suggesting that the individualisation and responsibilisation of citizens combined with the impression that risks can be ‘managed’ challenge Beck's contention that the world risk society will become increasingly politicised and develop cosmopolitan solutions to contemporary hazards. At least within the UK and the US, Beck's utopian vision appears to be hampered by private industry solutions which offer personal rather than collective risk management. Framed within neo-liberal discourses of the small state and the superiority of the market, the private management of risk promises to provide security not only more effectively, but also more cost-efficiently than political and cosmopolitan bargaining.