Kraftwerk are a special case indeed. Founded in 1970 by Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, the Düsseldorf-based group were the most artistically significant German music group of the 1970s. They exerted a formative influence on global pop music with their innovative approach to transpose academic, or ‘new’ electronic music into the realm of pop music. The defining characteristic of Kraftwerk’s work is the prominent incorporation of artistic concepts to which Hütter and Schneider had been exposed at the Düsseldorf Art Academy and within the local art scene. Accordingly, they saw themselves as performance artists rather than musicians.

Both musicians, and in particular Schneider, came from wealthy backgrounds. They had the financial means to purchase expensive synthesisers and other technical equipment for their Kling-Klang studio. Also, ownership of their label released Kraftwerk from the commercial restraints of a record company. Their strategic use of artistic autonomy was inspired by Andy Warhol and, like Warhol’s operation, Kraftwerk constituted a ‘myth machine’.

According to Dirk Matejovski, from Autobahn (1974) onwards, Kraftwerk formulated ‘an aesthetic concept that became ever more perfectly developed’. Initially Hütter and Schneider issued enigmatic interview statements of their artistic intentions to steer reception, but then ‘ceased all self-commentary in the 1980s’. The resulting ‘mystification through communication breakdown’ enabled the Kraftwerk myth to emerge.Footnote 1 Johannes Ullmaier proposes an alternative to the self-created mythologies and tendencies towards monumentalisation that originate especially from the Anglosphere: he proposes a more sober view of the band that undermines hero-worshipping narratives. In his view, the development of Kraftwerk’s oeuvre is perceived ‘as a gradual, … situational niche creation via clever, international, trial-and-error market analysis and adaptation’.Footnote 2

This chapter opens an overview of key Krautrock bands. Yet the extent to which Kraftwerk can be strictly classified as Krautrock requires critical evaluation. Such a subsumption is certainly unproblematic regarding their first three albums alone, Kraftwerk (1970), Kraftwerk 2 (1972), and Ralf & Florian (1973). But it was precisely this trio of albums that Kraftwerk – in a move no other band discussed in this volume ever did – disavowed and exorcised from their œuvre. Instead, they made their next album, Autobahn (1974), the official starting point of their discography. Whereas its B-side is still strongly influenced by the Krautrock sound of the first three albums, the title track, which takes up the entire A-side, heralded no less than a paradigm shift in the history of German popular music: the advent of electronic pop music.

Kraftwerk’s claim to autonomy in the field of pop music is based on their definition of their artistic production as a pop-cultural Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) and a ‘work in progress’. Not only can their output be divided into phases but also into two opposing modes of production: a conventional mode characterised by their ground-breaking concept albums (from 1974 to 1981) and then, from the 1990s onwards, a mode of curation. In the latter, they subjected their work to a permanent process of technical revision, stylistic adaptation, and intermedial expansion, which turned it into a transmedial, ‘open work of art’ (in Umberto Eco’s sense).

Finally, the most remarkable feature of Kraftwerk may well be that, more than fifty years after first emerging, they continue to give live performances, now under the sole artistic leadership of founding member Ralf Hütter. In addition to regular tours and festival appearances, Kraftwerk play concerts at prestigious venues such as symphony halls, world-class museums, and prestigious theatres. Their Gesamtkunstwerk approach, which unites sound and vision, has led to an immersive stage show with continuous 3D video projection and a multi-channel sound system based on wave field synthesis technology that creates sculptural sound effects.Footnote 3

Formative Influences

Hütter and Schneider were inspired to develop the concept of electronic pop music in the 1970s by local Rhineland musicians such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Mauricio Kagel, Pierre Boulez, Pierre Schaeffer, and György Ligeti. These avant-garde composers worked at the famous Studio for Electronic Music, which was founded in 1951 at the WDR public radio station. Equally significant for Kraftwerk were the technical experiments in electronic sound synthesis by the physicist Werner Meyer-Eppler, who was the first person to use the term electronic music in German in 1949.Footnote 4 Hütter and Schneider paid their homage with ‘Die Stimme der Energie’ (The Voice of Energy, 1975), a variant on a speech synthesis experiment conducted by Meyer-Eppler in 1949.

Via the Düsseldorf Art Academy and the local gallery and museum scene, Kraftwerk were influenced by the modernist avant-garde and contemporary Pop Art. Hütter and Schneider also adopted the strategy to subordinate their artistic project to conceptual principles. The latter encompasses far more than the mere fact that their œuvre consists of concept albums only. The band name itself, which translates as ‘power station’, has a conceptual function, since the electricity electronic music requires is generated in a power station. The conceptual approach is also evident in the artistic tactic of disappearing as private individuals behind the uniform group identity. This allowed Hütter and Schneider to reject the myth of authenticity surrounding rock musicians and style themselves as an artistic collective of ‘sound researchers’Footnote 5 and ‘music workers’.Footnote 6

Warhol’s influence, as already explained, looms large over the early work of Kraftwerk. The recurring use of pylons on the minimalist sleeves of the first two, untitled albums was evidently a nod to his serial art. Another important model was local Düsseldorf artist Joseph Beuys, whose conceptual art strategies were adapted by Kraftwerk in various ways. An important link to Beuys’s conceptual approach was provided by his student Emil Schult, who assumed the role of an unofficial band member. Schult guided Hütter and Schneider on how to align their artistic output to overarching conceptual ideas. Furthermore, he not only wrote most of the lyrics but also designed many record covers. Similarly, many ideas for Kraftwerk’s stage presentation stemmed from Schult. For instance, he devised the neon signs featuring the first names of the musicians that can be seen on the back sleeve of Ralf & Florian.

Industrielle Volksmusik from Germany (1970–1974)

Music journalists have made various attempts to label Kraftwerk’s electronic style of pop music. In addition to ‘synth pop’, Kraftwerk themselves suggested labels such as ‘electro pop’, ‘robo pop’, and ‘techno pop’ – the latter being one of the tracks on the album Electric Cafe (1986). Asked about the original artistic idea behind Kraftwerk’s music, Hütter told an interviewer: ‘To create music that reflects the moods and sentiments of modern Germany. That’s why we named our studio Kling-Klang [literally ding-dong], because those are typical German onomatopoetic words. We call our music industrielle Volksmusik from Germany.’Footnote 7

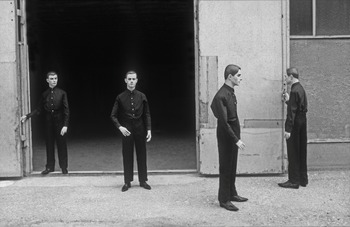

Illustration 6.1 Kraftwerk dolls.

This odd concept name, which literally means ‘industrial folk music’, requires critical analysis since it neither regards industrial music nor folk music in the received sense. The emphatic qualification ‘German’ is easier to comprehend: it reflects Krautrock’s impetus to create an alternative to the dominant, cultural imperialist model of Anglo-American rock/pop music. Kraftwerk, however, did not search for inspiration in cosmic expanses (like ‘Berlin School’ bands such as Tangerine Dream or Ash Ra Tempel), in the music of foreign cultures (like Can, Agitation Free, Popol Vuh etc.), in modernist aesthetics like the cut-up technique (like Faust), or in jazz (like Embryo). Rather, Hütter and Schneider decided to focus on forgotten German cultural traditions (such as the Gesamtkunstwerk, Bauhaus, or Expressionism) and often emphasised their Germanness, especially to anglophone interviewers. Thus, according to Melanie Schiller, ‘not least because of their German band name, they were an exception’Footnote 8 among the important Krautrock bands.

Kraftwerk also gave their songs exclusively German titles. The tracks on the first four albums can be categorised as follows: firstly, terms from electrical engineering, such as ‘Strom’ (Current), ‘Wellenlänge’ (Wavelength), or ‘Spule 4’ (Coil 4); secondly, German onomatopoetic or compound words such as ‘Kling-Klang’ (ding-dong), ‘Ruckzuck’ (in a jiffy), or ‘Tongebirge’ (Mountains of Sound); thirdly, programmatic terms from the field of music: ‘Tanzmusik’ (Dance Music) or ‘Heimatklänge’ (Sounds of Home). Therefore, the ‘industrial’ in industrielle Volksmusik does not primarily refer to factories – although the modernist redefinition of noise as music played a role in Kraftwerk’s work, along with their self-designation as ‘music workers’ – but rather to modern technology, in particular electronic machines that allow a new type of music to be made.

Kraftwerk understand this electronic music – against the background of the industrialisation and modernisation of post-war Germany – as constituting ‘Heimatmusik’ (ethnic/homeland music). As the band once proudly stated in a press release: ‘We make Heimatmusik from the Rhine-Ruhr area.’Footnote 9 Kraftwerk’s key work ‘Autobahn’, a homage to the extensive network of motorways in their home federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia, is a case in point. This piece of music is ‘industrial’ not only by virtue of its electronic nature but also in view of sound effects such as a car door slamming, engine noises, and vehicle horns. These noises, which Kraftwerk simply took from a library record, evoke the sonic presence of the Volkswagen engine that, as it were, drives the very motorikFootnote 10 of the track.

The meaning of the polyvalent concept of ‘Volksmusik’ becomes more apparent if we consider instrumental pieces like ‘Heimatklänge’ or ‘Tanzmusik’. The romantic simplicity of their melodies is striking. They are clearly alluding to the German folk song tradition but, at the same time, they highlight the electronic instrumentation that makes them modern versions of traditional folk songs. Autobahn, as an album, unites both properties in the contrast between the monotony of the ‘industrial’ title track and a ‘folk’ composition like ‘Morgenspaziergang’ (Morning Walk), which features electronic birdsong and gentle flute sounds. Kraftwerk’s Volksmusik, though harking back to folk tradition, must hence be understood as the ‘music of the people (Volk)’, that is, the populus; ultimately, it is a literal translation of the English term ‘pop music’ into German. The seemingly opaque expression industrielle Volksmusik could thus be simply rendered as ‘electronic pop music’ in English.

Although Autobahn was not completely electronically recorded, the album steered pop music into hitherto unexplored realms. This quantum leap, however, went largely unnoticed at first. As of the release, there was only one review in the German music press. It rated the title track as a ‘a car ride with whimsical music and a lot of drive’ but found that ‘the vocals, which are used for the first time, as yet lacked their own style’.Footnote 11

The initial reception in Britain – inevitably riddled with Germanophobic clichés – was similarly disparaging. ‘Odd noises, from percussion and synthesiser drift out from the speakers without any comprehensible order while a few words are muttered from time to time in a strange tongue. … Miss,’Footnote 12 rated one reviewer, while another opined, ‘Synthesizer-tweakers Hutter and Schneider try for a concept – a drive down the motorway – and convincingly blow the few avant-garde credentials fans of their earlier work awarded them. … Simple minds only.’Footnote 13

In the United States, however, Autobahn became a surprise success; the magazine Cash Box, for example, had only praise: ‘Ethereal, inspired and well-conceived, Kraftwerk relates through electronic wizardry and soaring synthesizer tracks the moody feeling of motoring along the road. … Lovely and interesting.’Footnote 14 A heavily cut single version of the title track soared to number twenty-five on the Billboard charts, subsequently catapulting the album to number five on the album charts, where it remained for more than four months. Kraftwerk were now a force to be reckoned with.

Retro-Futurism (1975–1977)

Autobahn indeed marks the inauguration of Kraftwerk’s core œuvre in that – at least as far as the title track is concerned – it represents their first attempt to achieve a pop-cultural Gesamtkunstwerk aesthetic: musical style, car noises, lyrics, cover image, and stage presentation merge seamlessly to form a coherent concept. Radio-Aktivität (Radio-Activity, 1975), then became Kraftwerk’s first complete concept album. The record was also fully self-produced in the band’s own Kling-Klang studio and recorded entirely electronically. With a playing time of thirty-eight minutes, the album resembles an experimental radio play as it emulates a radio broadcast, forming a continuous collage of sound effects, instrumentals, spoken word sections, and pop songs.

The play on words in the title is a fundamental aspect of the album: Radio-Aktivität refers both to nuclear energy, a controversial topic in Germany at the time, and the radio as a medium for transmitting political propaganda as well as musical entertainment. This ambivalent neutrality was implied by the album sleeve, which replicated the front and back of a National Socialist Volksempfänger radio. What emerged out of this ‘radio set’, however, was avant-garde electronic pop music. Radio-Aktivität thus undertook a merger of opposites that proved to be one Kraftwerk’s core artistic strategies. This constitutive ambivalence was reflected in the hyphen of the title and the bright yellow Trefoil radioactivity warning sticker that adorned each cover.

This unprejudiced treatment of the topic of nuclear energy caused disgruntlement in left-wing ecological circles, especially since Kraftwerk had themselves been photographed in white protective suits in a Dutch nuclear power plant. The Chernobyl nuclear disaster in April 1986 led Hütter and Schneider, however, to abandon their ambivalent stance on nuclear energy: the demand ‘Stop radioactivity!’ was added to the new recording of ‘Radioactivity’ for the compilation The Mix (1991); also, the line ‘Wenn’s um uns’re Zukunft geht’ (When our future is at stake) was replaced by the unequivocal ‘Weil’s um uns’re Zukunft geht’ (Because our future is at stake). For their June 1992 performance at the Greenpeace-organised anti-Sellafield benefit in Manchester, Kraftwerk also presented a new robot voice intro with a warning about radiation exposure from the Sellafield nuclear facility, which was later supplemented by other places associated with radiation accidents (Chernobyl, Harrisburg, and Hiroshima).

This modification demonstrates paradigmatically Kraftwerk’s understanding of their œuvre as an open work of art subject to a constant process of adaptation and updating. Their sensitivity to political considerations, however, resulted in a loss of ambivalence since it was precisely the tension between diverse thematic interpretations and a neutral presentation that had comprised Radio-Aktivität’s aesthetic value. The musician John Foxx (Ultravox) had described the original version of the title song to be ‘as neutral a Warhol statement as all their songs tend to be’.Footnote 15

This quality of neutrality, in turn, can be linked to Warhol’s artistic ideal of acting as a machine,Footnote 16 and forms a bridge to the man-machine concept because in ‘Kraftwerk there is no individual, experiential emotional language. They reject all emotionality and sensibility. The band members try to present themselves as emotionless musicians.’Footnote 17 Marcus Kleiner therefore considers Radio-Aktivität to embody Kraftwerk’s trademark ‘coldness’ that stands in direct contrast to the Anglo-American tradition. The latter can be described as a ‘narrative of heat and sweat and a history of excitement and sensuality’, which Kraftwerk countered with an ‘electronic coolness that has influenced the history of pop music history to the present’.Footnote 18

Today, the Radio-Aktivität sequence – performed in a mix of German, English, and Japanese and consisting of the tracks ‘Nachrichten’ (News), ‘Geigerzähler’ (Geiger Counter), and ‘Radioaktivität’ (Radioactivity) – is a highlight of every live concert. Visually, the performance is accompanied by video projections of animated warning symbols, excerpts from the original 1975 Expressionist video, and graphics showing nuclear reaction processes, while, musically, there is the shrill beeping of a Geiger counter, earth-shaking bass beats, and a beautifully simple melody – the whole, in total, constituting a magnificent pop-musical work of art.

Trans Europa Express (1977), released at the height of the punk explosion, most strikingly embodies Kraftwerk’s important stylistic principle of retro-futurism. Thus, the band’s nostalgic black-and-white cover photo marks a striking contrast to the zeitgeist of the time: the conservatively dressed musicians look like a group portrait from the 1930s or 1940s. While resembling a string quartet, on Trans Europa Express Kraftwerk defined a futuristic sound that made the album an electronic music blueprint that ‘inspire[ed] a new generation of electronic music producers to make sense of a developing post-industrial techno-world based on acceleration and electronics’.Footnote 19

Contrary to the gloomy urban realism of British punk, Kraftwerk evoked nostalgic images of the ‘elegance and decadence’ of the European continent on ‘Europa endlos’ (Europe Endless) and referred to the romantic tradition with the instrumental ‘Franz Schubert’.Footnote 20 Pertti Grönholm argues that such references to the past in combination with innovative electronic music aim to merge utopian ideas with melancholy images to create an aesthetic tension that confronts the present with unfulfilled promises of a better future:

Kraftwerk constructed a cultural and historical space that worked as an imaginary utopian/nostalgic refuge in the cultural situation of 1970s West Germany. … It excludes sentimentality and rejects the idea of a Golden Age but, instead, re-imagines the past as a continuum of progressive development and as a source of inspiration and ideas.Footnote 21

Trans Europa Express also exposes, as already implied in Autobahn, the ambivalent connotation of a means of transportation – in this case rail – in the historical context of Nazi Germany. While the project to build a national network of highways – the Reichsautobahn – was a propaganda tool of Hitler’s regime, the European rail network was used for the deportation of Jews to the extermination camps in the East. After the war, a transnational railway system was introduced to foster the idea of European integration: the Trans Europ Express (TEE) network was in operation from the late 1950s to the early 1990s. In its heyday, it connected 130 cities across Western Europe with regular services every two hours.

Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans Europa Express’, often considered one of their masterpieces, proved crucial to the development of electronic music. David Buckley considers it ‘the most influential possibly in their entire career’.Footnote 22 It consists of a sequence of three tracks that merge seamlessly into one another: the song ‘Trans Europa Express’ is followed by the instrumental ‘Metall auf Metall’ (Metal on Metal), which was originally followed by the short outro ‘Abzug’ (the sound of a train departing) as a separate track.

The thirteen-minute suite is based on relentlessly propulsive repetitions that imitate the velocity of a train. In this musical simulation of a train journey, the hammering sound of the railway wheels on the rails is transferred into music instead of translating the movement of the car journey into a motorik beat, as on ‘Autobahn’. Kraftwerk thus succeeded in converting industrial sounds into machine-generated music. Following in the footsteps of similar efforts by Dadaists and Futurists in the 1920s and 1930s to bring industrial modernism into art, Kraftwerk’s machine music allowed electronic pop music to become a perfect, danceable synthesis of avant-garde and pop.

This is especially true of ‘Metall auf Metall’, the central piece of the ‘Trans Europa Express’ suite. According to David Stubbs, it is ‘one of a handful of the most influential tracks in the entire canon of popular music’, while Simon Reynolds described it as ‘a funky iron foundry that sounded like a Luigi Russolo Art of Noises megamix for a futurist discotheque’.Footnote 23 The repercussions of the furious, dissonant metal machine sound was used throughout British pop music in the 1980s: by Peter Gabriel (‘I Have the Touch’), Depeche Mode (‘Master and Servant’), Visage (‘The Anvil’), as well as by the left-wing industrial collective Test Dept, but also the Düsseldorf industrial pioneers Die Krupps (‘Stahlwerksynfonie’, i.e. Steelworks Symphony) or Einstürzende Neubauten in Berlin, who took the title of the Kraftwerk piece literally.

However, the futuristic sounds from Germany with which Kraftwerk sought to express their ‘cultural identity as Europeans’Footnote 24 had a most decisive influence on African American minorities in urban centres such as New York and Detroit. There, they were adapted into new music styles such as electro or techno and re-contextualised as a means of expressing minority identity concepts. In the early 1980s, the New York DJ Afrika Bambaataa used the ‘Trans Europa Express’ suite for its uplifting hypnotic effect as a musical background to inflammatory speeches by activist Malcolm X.Footnote 25 According to Bambaataa, Kraftwerk never knew ‘how big they were among the black masses in ‘77 when they came out with Trans-Europe Express. When that came out, I thought that was one of the weirdest records I ever heard in my life.’Footnote 26

On the epoch-making track ‘Planet Rock’ (1982), Bambaataa fed the sonic exoticism of industrielle Volksmusik into the energy stream of the Afro-futurist tradition. By doing so, he unwittingly set in motion transatlantic electronic music feedback loops that have been operating ever since: ‘European art music’, according to Robert Fink, ‘is cast, consciously or not, in the role of an ancient, alien power source’.Footnote 27 Martyn Ware (Human League/Heaven 17) summed up the artistic merit of the album as follows: ‘Trans-Europe Express had everything: it was retro yet futuristic, melancholic yet timeless, technical, modern and forward-looking yet also traditional. You name it, it had it all.’Footnote 28

Post-humanism in the Computer Age (1978–1981)

Mensch-Maschine (Man-Machine, 1978) is Kraftwerk’s key work, since the concept of the man-machine lies at the core of their Gesamtkunstwerk aesthetics. ‘Strictly speaking, rather than the LP being a concept, the group themselves were now the concept, and the LP was merely a vehicle to further it’,Footnote 29 Pascal Bussy concludes. The term ‘man-machine’ has appeared in Kraftwerk’s promo statements since 1975 and remains an integral part of live performances today, with a robot voice explicitly announcing the band as ‘the man-machine Kraftwerk’ at each concert.

In addition to ‘Das Modell’ (The Model), Kraftwerk’s biggest pop hit, Mensch-Maschine contains the conceptually significant song ‘Die Roboter’ (The Robots). This signature tune is linked to the doppelgänger mannequins of the four musicians that have replaced the real group members on album covers and promotional photos since 1981. Even more conceptually significant, these puppets appear on stage as substitutes for the ‘music workers’ at every live performance. Their proud statement ‘Wir sind die Roboter’ (We are the robots) can hence be related to the dummy lookalikes as well as the band members. In this respect, the mechanical doubles embody a concretisation or personification of the abstract concept of the man-machine.

The highly influential cover, devised by the Düsseldorf graphic designer Karl Klefisch, shows the real, heavily made-up musicians appearing as artificial robot beings with pale faces. The distinct colour scheme of red, white, and black refers to the colours of the German imperial war flag as well as the National Socialist swastika flag while the (typo)graphic design of the cover directly refers to Bauhaus and Soviet constructivism. Accordingly, Mensch-Maschine can be linked to the attempt made in constructivism to establish a connection between revolutionary art and revolutionary politics; in Kraftwerk’s case, the band presents the pop-revolutionary concept of electronic future music. That is to say, the politically encoded hope for a better future is artistically imagined as a futuristic vision of a post-human synthesis of man and machine.

This technological eschatology is clearly celebrated by Kraftwerk. Yet, the Nazi experience does undermine the optimism of an invariably better future. Kraftwerk, as it were, remain mindful of the danger that the next paradigm shift in the evolution of humanity might easily lead to a relapse into totalitarian rule. The title of the instrumental ‘Metropolis’, which refers to the Fritz Lang’s Expressionist film of the same name – featuring the first robot in film history – also invites such a dystopian reading. After all, Lang’s prophetic vision was of a society that was deeply divided, both socially and politically; the critic Siegfried Kracauer famously condemned the film as proto-fascist in his influential book Von Caligari zu Hitler (From Caligari to Hitler, 1947). As ever so often, Kraftwerk’s retro-futuristic recourse to the German cultural tradition reveals a profound ambivalence.

The album mirrors the pronounced futurism of Mensch-Maschine and, at the same time, refers to a time before modernity. The fact that the cover gives ‘L’Homme Machine’ as the French translation of the album title creates a link to the 1748 treatise of the same name by the early Enlightenment philosopher Julien Offray de La Mettrie. His polemical book offered a radically materialistic view of the unity of body and soul and had a large influence on philosophers from ‘Hobbes and Pascal to Spinoza, Malebranche and Leibniz’. Subsequently, in Enlightenment discourse, ‘the ‘automaton’ became a contemporary cipher for the most diverse aspects in the anthropological and socio-political discussions’Footnote 30 of the true nature of man.Footnote 31

Mensch-Maschine thus positions itself in a broad, cultural-historical net of references and allusions. Despite its clearly futuristic orientation, the album simultaneously incorporates retro elements; one need only look critically at the doppelgänger dummies on stage during their performance of ‘Die Roboter’. As David Pattie soberly observes: ‘The robots do not look like the incarnations of a cyborgian future – if anything, they seem to hark back to a mechanical past.’Footnote 32 Once again, we encounter a deep-rooted ambivalence.

And it is such complexity that keeps Kraftwerk’s album relevant to today’s discussions about post-humanism. Leading experts in the field define objective post-humanist thought as follows: ‘The predominant concept of the “human being” is questioned by thinking through the human being’s engagement and interaction with technology.’Footnote 33 As hardly need be highlighted, this sounds like a summary of Kraftwerk’s artistic project.

With Computerwelt (Computer World, 1981), Kraftwerk released another decidedly futuristic album, which in retrospect proved quite prophetic. A key musical merit of Computerwelt is that Kraftwerk recorded the album almost entirely in analogue, which only underlines its visionary character. This time, Kraftwerk ‘do not predict a robotised, sci-fi future. However, they do predict, with complete accuracy, that our modern-day lives will be revolutionised’Footnote 34 by computer technology: console games, pocket calculators, and online dating, on the one hand, and computer-assisted surveillance, digital finance, and the total digitalisation of society, on the other, are the topics of the album.

Hard to miss on Computerwelt is its warning against social alienation and the political misuse of technology. The original German lyrics of the title track contain lines missing from its English-language version: ‘Interpol und Deutsche Bank / FBI und Scotland Yard / Finanzamt und das BKA / haben unsre Daten da’ (Interpol and Deutsche Bank / FBI and Scotland Yard / tax office and the BKA / have our data at their disposal). In an interview with Melody Maker, Ralf Hütter explained the aim of the album as ‘making transparent certain structures and bringing them to the forefront … so you can change them. I think we make things transparent, and with this transparency reactionary structures must fall.’Footnote 35

This explicitly political statement must be understood against the contemporary historical background. The BKA (Bundeskriminalamt – federal criminal police agency) conducted computer-assisted ‘dragnet searches’ to apprehend terrorists of the Red Army Faction, also known as the Baader–Meinhof Gang. ‘Computerwelt’s’ lyrics state that the BKA is part of an international network of financial organisations and law enforcement agencies, correctly predicting that such institutions would be conducting their daily business digitally today. Similarly, it is hardly an exaggeration to claim that Kraftwerk anticipated the surveillance of digital privacy by state agencies such as the NSA or the British GCHQ.

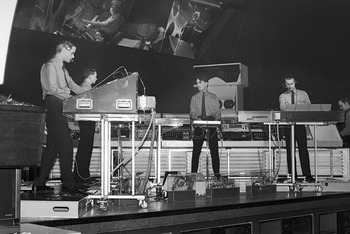

Illustration 6.2 Kraftwerk live, 1981.

With its obsessively repeated sequences of numerals in various languages, Computerwelt’s key track ‘Nummern’ (Numbers) fits perfectly into this context, simulating, as it were, the automated stock exchange deals and transnational financial transactions that characterise today’s digital economy. The track foresaw the proliferating flow of numerical data that has replaced traditional language-based communication and cultural exchange.

In ‘Nummern’, even more importantly, Kraftwerk also found a new musical form, a radically minimalist aesthetic that combined a modernist approach with strict functionality inspired by the Bauhaus: a hypnotic piece of music that was almost brutal in its reduction to a mercilessly hammering beat, audibly anticipating techno. ‘Numbers’, according to Joseph Toltz, ‘is a striking work, not only in the general context of Kraftwerk’s output, but also because it seems so different and more experimental than their other tracks’.Footnote 36 ‘Nummern’ encapsulates the radically new sound aesthetic of Computerwelt, which Kraftwerk had worked on for three years – longer than any previous album. It was true Zukunftsmusik (future music), considering its clinically pure sound and perfect musical realisation of an electronic aesthetic that proved eminently influential transnationally.

Computerwelt concludes and artistically crowns the sequence of five pioneering albums Kraftwerk had released in the seven years since Autobahn. In the 1980s, their electronic music inspired both British synth-pop musicians and African American producers who developed synth pop, disco, new wave, and funk into techno and house. Likewise, Kraftwerk’s use of speech synthesis and electronic processing of vocals, for which Florian Schneider was primarily responsible, became a staple of music production today. With Computerwelt, Kraftwerk’s mission as the avant-garde of electronic pop music had come to an end; from now on, they were competing with the multitude of musicians who pushed their industrielle Volksmusik in new directions.

Digitisation (1983–2003)

After Computerwelt, a paradigm shift set in. With the acquisition of a New England Digital Synclavier, Kraftwerk ushered in the era of digital music production. This, in turn, heralded a new modus operandi: a shift from the production of new tracks to the curation of existing work. Under the aegis of sound engineer Fritz Hilpert, all analogue tapes were painstakingly digitised. This groundwork not only laid the foundation for the 1991 compilation The Mix, on which new versions of Kraftwerk’s most important songs were digitally reconstructed, but also for the transition to digital sound production at live performances.

The follow-up to Computerwelt was announced in 1983 under the title Techno Pop but then withdrawn, only to finally appear in 1986 as Electric Cafe. As the change of title indicates, the conceptual nature of the album was not particularly pronounced: Electric Cafe can be understood as a record about communication or as a self-reflective album about electronic pop music.Footnote 37 The use of several, mostly European languages, explored for the first time in ‘Numbers’, also characterises the erstwhile title track ‘Techno Pop’, which celebrates the transnational omnipresence of ‘synthetic electronic sounds / industrial rhythms all around’ – in large part due to Kraftwerk – in German, French, English, and Spanish lyrics.

‘Tour de France’, which mirrored Hütter and Schneider’s obsession with cyclingFootnote 38 and was to have appeared on the withdrawn Techno Pop, was released as a single in 1983. Some twenty years later, this celebration of cycling turned out to be the basis for Tour de France Soundtracks (2003), Kraftwerk’s final studio album. This often-underrated record features a clear concept and various thematic links to prior albums: it shares not only the motifs of movement und propulsion with Autobahn and Trans Europa Express but also the principle to musicalise sounds produced by modes of transportation, this time cycling. Furthermore, the pairing of cyclist and bicycle, in Hütter’s view, also represents a configuration of a man-machine.Footnote 39 While the concept album Autobahn, which praised an ambivalent national symbol and featured German lyrics for the first time, served as their official debut, Kraftwerk’s remarkable run of studio albums is concluded by a concept album sung (almost) entirely in French that celebrates the most sustainable way to travel.

This reflects a notion that already characterised Trans Europa Express and became increasingly manifest using multilingual lyrics on their albums during the 1980s. Given the country’s fascist history, German identity in the post-war period involved a commitment to the idea of a European community of countries sharing the same culture and common values. Or to put it another way: Kraftwerk were always advocating a political utopia still unfulfilled today, namely, to move from a violent Nazi past into a European future characterised by peace, freedom of movement, and cooperation. On the occasion of seeing Kraftwerk in June 2017 at the Royal Albert Hall, Luke Turner succinctly remarked that ‘an idealised sense of the European is distilled in every vibration of every note and tonight feels like another world’; and considering Brexit, Turner added the valid question: ‘Do we Brits no longer deserve their European futurism?’Footnote 40

A Pop-Cultural Gesamtkunstwerk?

During the band’s fifty-year existence, Kraftwerk’s orientation towards a concept-based aesthetic led to a process in which image, sound, and text were increasingly synthesised to form a unified body of artistic work. This process, however, took place as a successive reaction to external circumstances along conceptual lines, some of which emerged only during the development process. It is further noteworthy that Kraftwerk’s overall multimedia aesthetic not only concerns the audio-visual core of the œuvre (i.e. the officially released music and stage performances) but also such related marketing paraphernalia such as concert posters, tickets, the Kraftwerk website, and merchandise.

Following the release of Tour de France Soundtracks, the artistic activities of the project, now solely led by Hütter, shifted more and more towards the curation of the core work as well as the musealisation of Kraftwerk. With the help of the renowned Sprüth Magers gallery, Hütter moved Kraftwerk successfully from the context of pop music into the field of art. An important prerequisite for this undertaking was the remastered edition of the eight albums from Autobahn to Tour de France in the box set called Der Katalog (The Catalogue), released in 2009.

The now officially sanctioned corpus of albums formed the basis for the concert series Retrospective 12345678 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in April 2012. Further performances of musical retrospectives, each spanning eight evenings, took place at other symbolic venues such as the Sydney Opera House, Vienna’s Burgtheater, the Tate Modern in London, the Arena in Verona, and Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie. In autumn 2011, the stage visuals, which have been presented in 3D technology since 2009 and are billed by Kraftwerk as ‘musical paintings’,Footnote 41 were exhibited at Munich’s renowned Lenbachhaus museum. Increasing recognition of Kraftwerk by the art scene as a performance art collective (rather than a mundane pop band) closed a circle insofar as many of the band’s first public appearances had taken place in Düsseldorf galleries due to a lack of music venues in the early 1970s.

Hütter’s curation activities in the twenty-first century have focused on updating and extending the visual component of the core works. In addition to the introduction of continuous 3D live projections, this involved the revision of all cover designs and a radical revision of the œuvre in the 3-D Der Katalog boxset released in 2017. The first version of Der Katalog already featured some noticeable changes in the album artwork. For example, the Nazi Volksempfänger on the sleeve of Radio-Aktivität was replaced by an intense yellow cover with the nuclear Trefoil symbol in bright red, and the photographs of the real musicians disappeared from the artwork of Trans Europa Express and Mensch-Maschine.

In the radical design overhaul of the 2017 version of Der Katalog, however, all cover designs have been replaced by monochrome record sleeves. This move towards abstraction was accentuated by substituting the numbers one to eight for the album titles, which made the records appear as segments of a coherent, eight-part work. Finally, all the tracks were re-recorded with current equipment – ostensibly during live performances from 2012 to 2016, but possibly in the Kling-Klang studio – and in several cases the original track sequence was altered.

Given the decidedly inter- as well as transmedial nature of the œuvre, one can argue that Kraftwerk firmly belong in the tradition of the modernist Gesamtkunstwerk. Many of their formative stylistic influences, especially Bauhaus and the theatre reform movement, point to modernist updates of Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk model. For example, Erwin Piscator’s vision of a ‘total theatre’ – in which he sought to unite the stage with the cinema – bears an evident resemblance to Kraftwerk’s conceptual notion of moving, three-dimensional ‘musical paintings’; similarly, Piscator’s goal of an ‘ecstatic overcoming of the “only-individual” in a communal experience’Footnote 42 in the theatre audience finds its counterpart in the immersive, audio-visual experience of a Kraftwerk concert. Anke Finger sees ‘teleology as the central tenet’ of the Gesamtkunstwerk aesthetics of modernism, which is why every Gesamtkunstwerk ‘represents something which is in the process of emerging, something which may be perfectly conceived but is not perfectly executed and perhaps never can be’.Footnote 43

Kraftwerk’s astounding fifty-year body of work is a pop-cultural Gesamtkunstwerk that confirms Finger’s theoretical assessment and, in accordance with the pop musical core strategy of ‘re-make, re-model’,Footnote 44 Kraftwerk’s œuvre remains in flux. Their live performances deliver an unprecedentedly immersive experience that fuses art, technology, and music and are a true ‘Kunstwerk der Zukunft‘ (future work of art), to borrow a term from Wagner, which one should experience while it is still possible.

Essential Listening

Kraftwerk, Ralf & Florian (Philips, 1973)

Kraftwerk, Expo Remix (EMI, 2001)

Kraftwerk, Minimum–Maximum (EMI, 2005)

Kraftwerk, Der Katalog (EMI, 2009)

Kraftwerk, 3–D Der Katalog (EMI, 2017)