Introduction

Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) accounts for 10–15 per cent of all head and neck cancers.Reference Jemal, Siegel, Ward, Hao, Xu and Murray1 The current treatment for oral cavity SCC is wide local excision of the primary tumour and simultaneous neck dissection, which entails clearance of the first echelon lymph nodes and the submandibular gland, for prophylactic and therapeutic management of the neck.Reference Byers, Wolf and Ballantyne2

The most significant prognostic factor in oral cavity SCC is the status of the cervical lymph nodes.Reference Shingaki, Takada, Sasai, Bibi, Kobayashi and Nomura3 Even a single lymph node metastasis may diminish survival by approximately 50 per cent.Reference Shah4 Consequently, neck dissection forms an integral aspect of the surgical treatment of oral cavity SCC. With improved understanding of the distribution of regional metastasis, neck dissection has evolved from radical clearance to more selective and functional procedures.

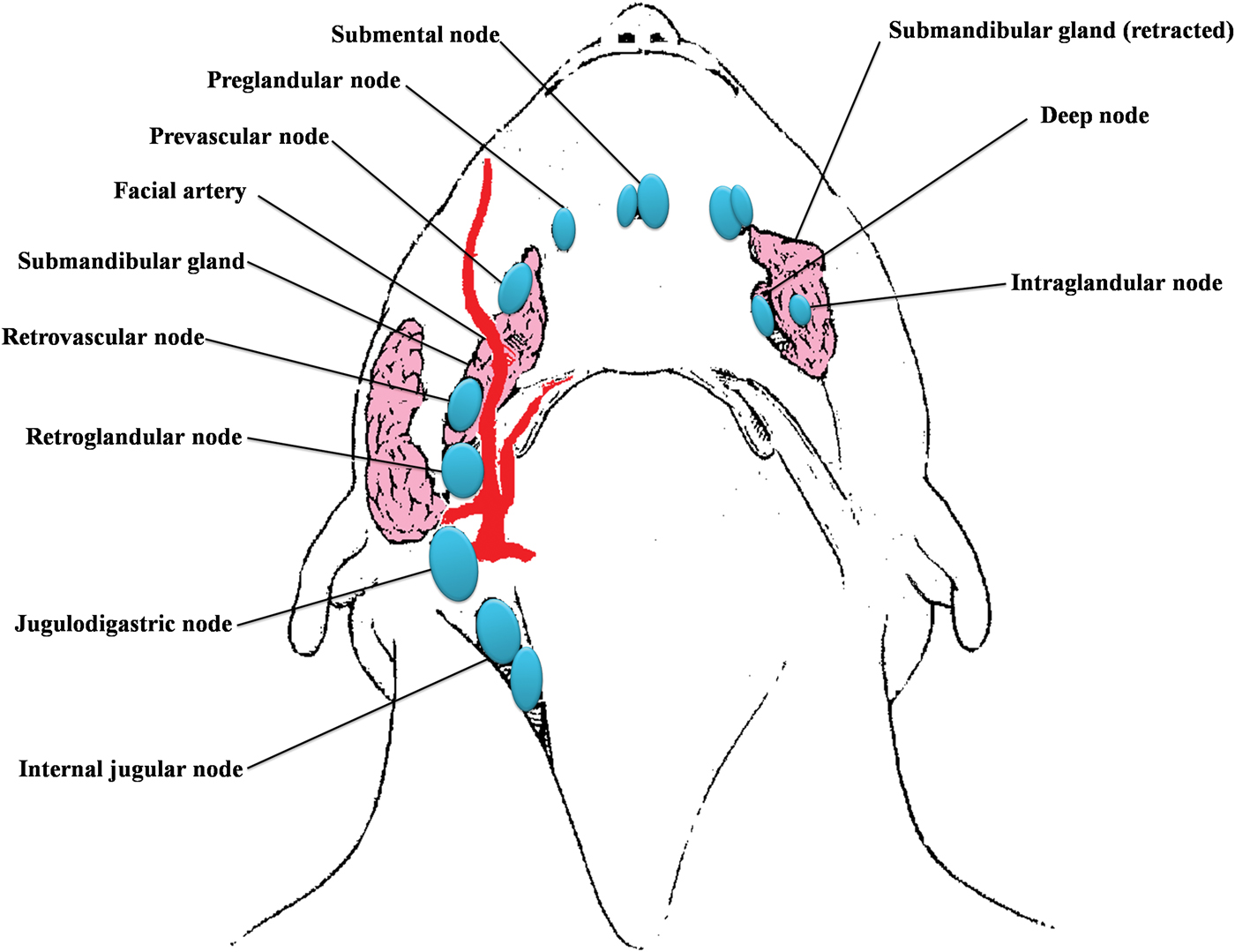

The submandibular gland is located in level Ib, and has six subgroups of lymph nodes around and within it (Figure 1). Therefore, it is usually removed regardless of the type of neck dissection performed.Reference DiNardo5 To date, submandibular involvement in oral cavity SCC has been rarely reported (Table I), being due mainly to contiguous spread from floor of mouth carcinomas, or direct extension from involved adjacent lymph nodes. Reference Byeon, Lim, Koo and Choi6–Reference Spiegel, Brys, Bhakti and Singer10

Fig. 1 Diagram of the six subgroups of submandibular lymph nodes.5

Table I Reported submandibular gland involvement in oral cavity SCC

SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; pts = patients; SG inv = submandibular gland involvement

The submandibular glands are responsible for approximately 70 to 90 per cent of unstimulated salivary volume, especially at night.Reference Jacob, Weber and King11 Saliva is not only important for lubrication of the oral cavity but is also vital for antimicrobial activity in the mouth, re-mineralisation of teeth, maintenance of oral mucosal immunity, and preparation of the bolus of food during mastication.Reference Byeon, Lim, Koo and Choi6 Removal of the gland causes variable xerostomia even in patients who do not receive post-operative radiotherapy.Reference Jacob, Weber and King11 Dysfunction of salivation may lead to oral discomfort, mucositis, periodontal disease, dental caries, fissures of the tongue, impaired sense of taste, discomfort with previously well fitting dentures, and impaired mastication and swallowing.Reference Byeon, Lim, Koo and Choi6 Jacob et al. found that a third of patients with early-stage oral cavity SCC who underwent neck dissection with concomitant removal of the submandibular gland experienced xerostomia and an increased incidence of dental caries, compared with control groups.Reference Jacob, Weber and King11

Although there have now been five reports, by five different groups of researchers, indicating that submandibular gland resection can be avoided without compromising oncological safety, especially in early-stage oral cavity SCC, a consensus decision on submandibular gland preservation has not yet been reached.Reference Byeon, Lim, Koo and Choi6–Reference Spiegel, Brys, Bhakti and Singer10

Thus, submandibular gland involvement in oral cavity SCC appears to be rare, and the morbidity associated with submandibular gland excision is substantial. Against this background, we undertook the present study to assess the incidence of submandibular gland involvement in oral cavity SCC, and also to add a South African experience and perspective to the intercontinental discussion on potential submandibular gland preservation in this clinical setting.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study reviewed the charts and histopathological records of all patients with oral cavity SCC managed at the Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital, a tertiary referral hospital in Durban, South Africa. The study period was from 1 January 2004 to 30 June 2009. Patients were treated with wide local excision of the primary tumour, plus simultaneous neck dissection and reconstruction if required.

The inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) histopathologically confirmed SCC; (2) a primary site located in the oral cavity; and (3) no previous treatment for head and neck tumours. The exclusion criteria were: (1) a prior history of other head and neck tumours; (2) irradiation of the head and neck regions; (3) proven distant metastasis at presentation; and (4) non-SCC tumour.

All surgical specimens were submitted for histopathological evaluation, including those from the primary tumour and neck dissections. Submandibular gland specimens were processed routinely but were reviewed retrospectively by a single anatomical pathologist. The wax blocks containing submandibular gland tissue were sectioned completely, without tissue reserve. The age, sex, primary site, and tumour and node classification were evaluated for each patient. The tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) status of each tumour was classified according to the 2005 criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer.Reference Patel and Shah12 The incidence of pathological involvement of the submandibular gland by oral cavity SCC was calculated.

Results

A total of 109 charts, pathology reports and slides were reviewed. Forty patients were excluded from the study as their submandibular glands were not sampled during pathology processing. The study cohort thus comprised 69 patients (46 men and 23 women). The male to female ratio was 2:1. Patients' mean age at presentation was 58 years (range, 38–99 years).

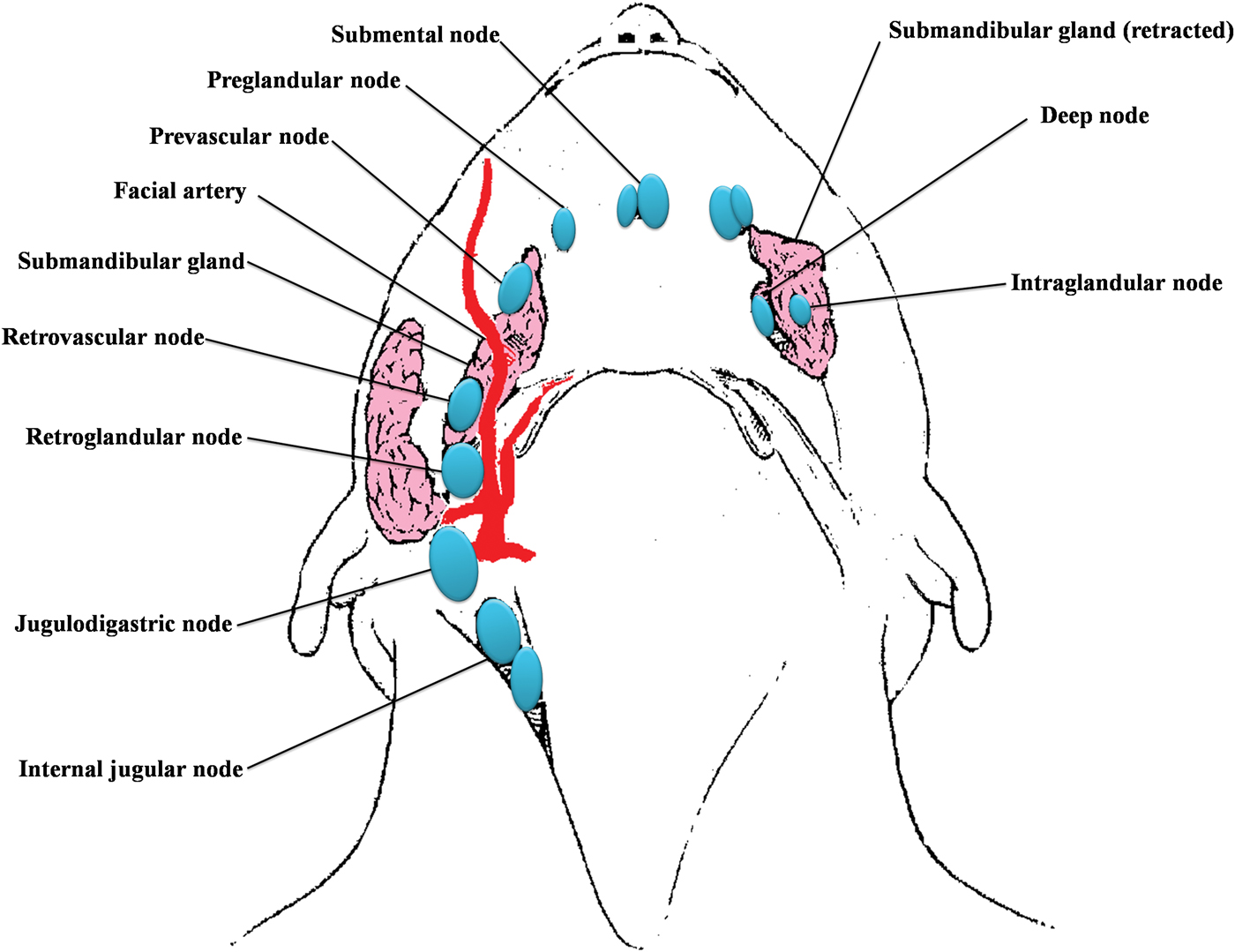

The distribution of the primary tumour subsites within the oral cavity is summarised in Table II. Most tumours involved the tongue or the floor of the mouth (49 cases; 71 per cent) (Table II). All tumours were characterised by an ulcerative, fungating appearance (Figure 2a). The majority (62.3 per cent) of tumours were classified as T3 or T4 lesions (Table III).

Fig. 2 (a) Macroscopic view of an ulcerative, fungating squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. (b) Photomicrograph showing squamous cell carcinoma (arrow) within the submandibular gland. (H&E; ×240)

Table II Primary sites of oral cavity SCC*

* n = 69. SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; pts = patients; sup = superior; inf = inferior

Table III Clinical tumour staging

Data represent patient numbers (percentages, where calculated). N = node stage; T = tumour stage

A total of 106 neck dissections were performed. Thirty-two patients had a unilateral neck dissection and 37 had a bilateral neck dissection. Only three patients (4.3 per cent) had positive contralateral nodes. A total of 56 patients had positive neck disease. The size of the lymph nodes in level I ranged from 2 to 30 mm. However, only 12 of the 56 patients (21.4 per cent) had nodes positive for tumour; the size of these nodes ranged from 10 to 30 mm (Table IV). Most patients (62.3 per cent) fell within the N2 lymph node category. Forty-seven patients (68.1 per cent) had stage four disease.

Table IV Level I lymph nodes: number, size and positivity

*Submandibular glands with metastases. Pt no = patient number; +ve = positive; NA = not applicable (as no metastases in lymph nodes)

A total of 69 submandibular glands were analysed histologically. There were no identifiable lymphovascular or perineural metastatic deposits in any of the submandibular glands examined. Only two (2/69 (2.9 per cent)), ipsilateral submandibular glands showed direct extension of the primary tumour (Figure 2b); one of these patients had SCC of the floor of the mouth and the other had an advanced tongue lesion. In both cases, the primary tumour was categorised as T4 N2c Mx, compatible with a diagnosis of advanced disease.

Discussion

The submandibular gland is usually removed as part of the traditional radical neck dissection first described by Crile in 1906.Reference Rinaldo, Ferlito and Silver13

In contrast to other organs, the submandibular gland has a poorly developed lymphatic and vascular network. Rouviere was the first to describe and divide lymph nodes surrounding the submandibular gland.Reference Rouviere14 DiNardo further subdivided these lymph nodes into six subgroups: preglandular, prevascular, retrovascular, retroglandular, intraglandular and deep.Reference DiNardo5 Of these, the intraglandular and deep groups are of little clinical significance, as some cases have few nodes, or none, in these positions.Reference DiNardo5 Sinha and Ng demonstrated an absence of intraglandular lymph nodes in the submandibular gland.Reference Sinha and Ng15

Metastasis to the submandibular gland occurs more commonly through haematogenous spread of cancers occurring outside the head and neck.Reference Rosti, Callea, Merendi, Beccati, Tienghi and Turci16 Vessecchia et al. performed a literature review which identified more than 100 cases of metastasis to the submandibular gland.Reference Vessecchia, Di Palma and Giardini17 Most of these metastases arose from primary tumours at distant sites, including the breast, lungs and genitourinary system.

In patients with oral cavity SCC, the incidence of occult nodal metastasis ranges from 20 to 44 per cent.Reference Pentenero, Gondolfo and Carrozzo18 However, when Junquera et al. evaluated histological submandibular gland involvement in 31 patients with SCC of the floor of the mouth, they found no such involvement in any patient.Reference Junquera, Albertos, Ascani, Baladron and Vicente8 Razfar et al. studied regional metastasis from early oral SCC in 226 patients, and found level I lymph node metastasis in only 11.5 per cent, and no submandibular metastasis.Reference Razfar, Walvekar, Melkane, Johnson and Myers9 Similar to the present study, Byeon et al. reported two cases of submandibular gland involvement by direct extension of the primary tumour to the submandibular gland, in a group of 201 patients with oral cavity SCC.Reference Byeon, Lim, Koo and Choi6 Although lymph node metastasis surrounding the submandibular gland is relatively common, it is extremely unusual to find submandibular gland metastasis. To date, metastasis of head and neck SCC to the contralateral submandibular gland has not been reported.

Resection of the submandibular gland may result in reduced salivary outflow and xerostomia.Reference Jacob, Weber and King11, Reference Hughes, Scott, Kew, Cheung, Leung and Ahuja19 Jacob et al. found that a third of patients with early-stage oral cavity SCC who underwent neck dissection and concomitant removal of the submandibular gland experienced xerostomia, and had an increased incidence of dental caries compared with control groups.Reference Jacob, Weber and King11 Cunning et al. showed that unilateral submandibular gland excision resulted in significantly decreased unstimulated salivary flow and an increased incidence of subjective xerostomia.Reference Cunning, Lipke and Wax20

• Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) constitutes 10–15 per cent of all head and neck cancers

• The submandibular gland is routinely removed during neck dissection

• Some now advocate preservation of the gland, especially in early-stage oral SCC

• This study found no oral SCC metastasis in removed submandibular glands

• Gland preservation may be appropriate in early-stage oral SCC with pre-operative node 0 neck

Of the 69 submandibular glands excised in the present study, none demonstrated metastasis. This low incidence of submandibular gland involvement is supported by other studies reporting incidences of 0–4.5 per cent.Reference Byeon, Lim, Koo and Choi6, Reference Chen, Lo, Ko, Lou, Yang and Wang7, Reference Razfar, Walvekar, Melkane, Johnson and Myers9, Reference Spiegel, Brys, Bhakti and Singer10

There is currently an increasing trend towards organ preservation surgery. If the lymph nodes around the submandibular gland can be removed, with preservation of gland function, then xerostomia and complications associated with saliva deficiency will be avoided. This is especially relevant to patients with early-stage oral cavity SCC.

The present study found submandibular gland invasion in only two patients with advanced stage (T4) oral cavity SCC. Therefore, we propose that patients with early stage lesions (i.e. T1 or T2) may be candidates for preservation of the submandibular gland during neck dissection, provided that the margins of primary tumour excision are adequate. However, if the surgeon performing neck dissection observes any suspicious lymph node metastasis or close contact between the tumour and the gland, then the gland must be removed.

To date, there are no reported studies comparing tumour recurrence rates following submandibular gland preservation in patients with periglandular lymph node metastasis.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that the incidence of submandibular gland involvement by oral cavity SCC is extremely low. The only cases of malignant infiltration occurred by contiguous invasion of the primary oral cavity carcinoma. In agreement with previous studies by five different groups of investigators, we too propose that patients with early-stage oral cavity SCC and with a pre-operative N0 neck may be candidates for submandibular gland preservation during neck dissection.Reference Byeon, Lim, Koo and Choi6–Reference Spiegel, Brys, Bhakti and Singer10

Patients with oral cavity SCC have an overall five-year survival of 59 per cent.Reference Pugliano, Piccirillo, Zequeira, Fredrickson, Perez and Simpson21 To date, no study has assessed outcomes in oral cavity SCC patients in whom the submandibular gland has been preserved. We plan to undertake a five-year, prospective study to determine the oncological safety of preserving the submandibular glands in selected early-stage (i.e. T1 or T2) patients with oral cavity SCC, in order to fill this gap in the literature.

Acknowledgements

We thank: Dr J Deonarain for graphic representation of Figure 1 and for assistance with gross and microscopic images; Drs S Srikewal and S Basanth for assistance with data collection; and Mrs M Moodley for assistance with manuscript formatting.