‘Virtuosic singers like Christine Nilsson [and] Jenny Lind’, lamented the Norwegian music periodical Nordisk musik-tidende in 1888, ‘have long secured for Sweden the richest laurels in the great world arena.’ It went on to acknowledge that while Norwegian composers were widely admired in Europe, the country had produced just ‘a single singer who has captured a place among the so-called “stars.” This is Miss Gina Oselio, who, after seven years of staying abroad, has returned home for a short summer visit and in a few days shall give a concert here in Christiania [Oslo].’Footnote 1

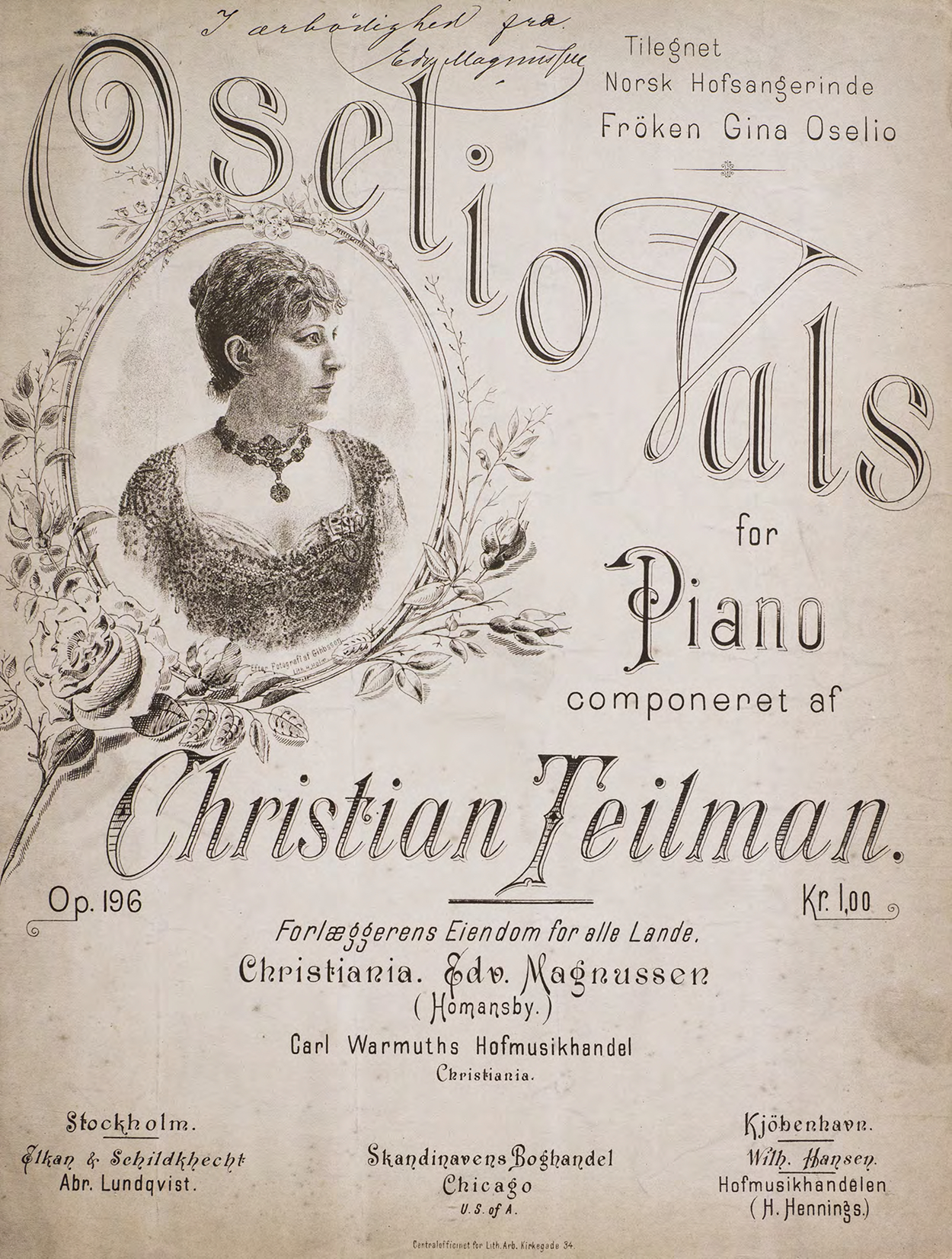

Gina Oselio was the stage name of the Norwegian opera singer Ingeborg Aas (1858–1937) and the much-anticipated concert took place on 3 October 1888 at the Gamle Logen concert hall. There the mezzo-soprano, accompanied by pianist Erika Nissen, performed selections from Bizet's Carmen to art songs by Norwegian composers.Footnote 2 This triumphant re-appearance led to a series of engagements and Oselio soon became wildly popular with both the public and fellow artists. Her pseudonym was adopted as a first name for babies, local musicians composed works in her honour (Figure 1) and the actor-director Bjørn Bjørnson (1859–1942) was so smitten with her that he divorced his wife in order to marry the singer.

Figure 1. ‘Oselio Vals’, op. 196 by Christian Teilman (courtesy of Furman University Libraries). (colour online)

As Nordisk musik-tidende made clear, Norwegians were eager to demonstrate their equality with Sweden – and with western Europe more broadly. Oselio would never be as famous as Nilsson or Lind, but she had enjoyed widespread success in Italy, as well as performances in England, Spain and Hungary. Such accomplishments made her a legitimately cosmopolitan singer (if not quite an international ‘star’) and her Italianate pseudonym underscored this aspect of her operatic identity. Ironically, it also minimised the very ‘Norwegianness’ that her compatriots were now so eager to emphasise. That national identity had been largely incidental during her career and rarely invoked in discussions of how and what she sang. Foreign critics occasionally remarked on it in passing, but she was sometimes misidentified as Swedish and usually not identified according to nationality at all. Unlike other Norwegian musicians who often found themselves treated only in terms of their national origin, Oselio appeared to have little connection to her county's cultural presentation.Footnote 3

Upon her return in 1888, however, Oselio's ‘Norwegianness’ suddenly became the focus of how her operatic achievements were understood. It also drew attention to the place that opera occupied, or to be more accurate, did not occupy within Norway. Despite efforts to create authentic Norwegian works (including the ill-fated collaboration between Edvard Grieg and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Oselio's future father-in-law), there was no national repertoire in which the star could distinguish herself. There was no national company to engage her and no recognised national venue in which she could appear. While the singer's success was much admired, it was not clear how Oselio's ‘Norwegianness’ would subsequently be expressed in Norway itself. Such artistic and practical difficulties reflected the ongoing struggles that had defined the country's musical activity for most of the century. How did this nation, long dominated by its more powerful Scandinavian neighbours, establish its own cultural independence? And what form would this cultural independence take?

As this context would suggest, discussions of Oselio have tended to summarise her international career or to treat her as a minor episode in Bjørnson's biography.Footnote 4 She is acknowledged as important to the history of Norwegian opera, but primarily as an example of the ways in which singers sought success beyond the country's borders. However, Oselio's private papers (including diaries, unpublished essays, musical manuscripts and printed scores) offer new insights into the complex relationship between the singer and the nation. Together with her reception history, as documented by the contemporary press, these materials invite a fresh examination of Oselio's position in fin-de-siècle Norwegian musical life. They show how she cultivated her career and her identity outside Norway, as well as her deliberate decision to assert her ‘Norwegianness’ – but on her own terms and according to her own priorities. They demonstrate the roles, both musical and symbolic, that Oselio wished to occupy on the country's stages and how Norwegians responded to these roles. Ultimately, they document a period of transition, as artists, critics and audiences alike sought to determine the place that opera should occupy within the nation.

Cultivating a career

In 1925, Oselio published part of her memoirs in the newspaper Aftenposten. By this date, she was long retired from the opera stage and was now engaged (at least according to the newspaper) in writing a fuller story of her life.Footnote 5 This published account focused on her early years in Norway, introducing readers to her two most formative musical experiences. The first took place in 1872, when a family friend allowed Oselio backstage at the Møllergaten Theatre.Footnote 6 From this vantage point, she observed a performance of Jacques Offenbach's La belle Hélène with great delight. Her backstage observation had little to do with avoiding having to pay for a ticket (Oselio was brought up in a comfortable bourgeois household) and much more to do with the general attitude towards this opéra bouffe, which had provoked considerable scandal when first staged in Norway in 1866. The second experience was a recital by Christine Nilsson. In contrast to the Offenbach episode, this performance left the young Norwegian unimpressed. She found the Swedish singer ‘uneasy’ and ‘nervous’ on the concert stage, behaviour that would affirm the aspiring Oselio's confidence in her own talents.Footnote 7

It was telling – if entirely typical – that neither event had any national significance. Indeed, Oselio's account stresses the lack of Norwegian repertoire and Norwegian singers (before her own return, of course). Operas, operettas and concert recitals in Norway had always relied heavily, if not exclusively, on foreign works and foreign singers. This reliance did not necessarily mean fewer performances. In 1862, for instance, Christiania's Norske Theatre engaged an itinerant German company to stage ten operas: Flotow's Alessandro Stradella, Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia, Boieldieu's La dame blanche, Mozart's Don Giovanni and Die Zauberflöte, Weber's Der Freischütz, Rudolph Bay's Lazarilla, Conradin Kreutzer's Das Nachtlager in Granada, Bellini's Norma and Verdi's Il trovatore.Footnote 8 Similar repertoire, as Børre Qvamme has shown, was regularly produced in Christiania and in some regional theatres as well.Footnote 9 Norwegians were thus conversant with many of the same works that enjoyed popularity elsewhere in Scandinavia and in Europe. This variety was satisfying in some respects but dissatisfying insofar as it underscored Norway's own musical deficiencies. In their 1874 application to the Storting (Norwegian parliament) for travel funds, Grieg and Johan Svendsen decried the absence of a national opera with orchestra and chorus, an absence which forced composers and performers to study abroad in order to meet ‘the demands of art and our time’.Footnote 10

The relationship between music and nationalism in nineteenth-century Norway was obviously a vexed issue, further complicated by the nation's changing political status in Scandinavia. Although Demark had ceded Norway to Sweden in 1814, allowing for the creation of the new dual-monarchy, it was not easy for Norwegians to separate themselves from several hundred years of Danish dominance.Footnote 11 In his discussions of Grieg, Daniel Grimley has noted the difficulty of isolating the specific qualities of emerging Norwegian nationalism; while it was ‘emancipatory, creative, and ritualistic’, these were ‘features common to other forms of nationalism in nineteenth-century Europe’ and shared ‘their preoccupation with images of landscape and nature’.Footnote 12 Works such as Waldemar Thrane's 1825 light opera Fjeldeventyret and the Christiania Theatre's 1849 tableaux vivants employed traditional melodies, peasant characters and folk dances to evoke Norway, although always with reference to the European context, in which such local colour had been absorbed.Footnote 13

The 1849 tableaux, for instance, concluded with a realisation of Adolph Tidemand and Hans Gude's famous 1848 painting Brudeferd i Hardanger. This painting depicts a bridal procession afloat on the Hardangerfjord, the human figures dwarfed on all sides by towering cliffs that descend steeply into the water. The bride, seated in the boat, is dressed in a traditional bunad while a musician plays the Hardanger fiddle. The painting conveyed an image of Norway that was at once geographically and culturally distinct, an evocative symbol of national Romanticism. In the tableau, amateurs from the Christiania elite portrayed the bridal party and the violinist Ole Bull himself appeared as the fiddler. Ann Schmiesing describes this whole event (and indeed the painting) as a series of falsifications – ‘idealized imaginings of peasant life’.Footnote 14 At the same time, these proved to be highly productive as for Schmiesing they established ‘an overarching Norwegian identity in which the urban actors and their urban spectators were … still connected to a Norwegianness rooted in rural life’.Footnote 15

Language was another critical and disputed marker, especially at the Christiania Theatre, which remained the domain of Danish repertoire and Danish actors. During the 1830s, the writers Henrik Wergeland (1808–45) and Johan Welhaven (1807–73) had suggested two very different ways of understanding this problem. Both acknowledged that Norway lacked dramatic repertoire of its own and that changes in practice depended on producing new works. In the meantime, if foreign works were still to appear – as they inevitably must – would they enhance (Welhaven) or diminish (Wergeland) the country's own cultural endeavours? Could they provide useful models for Norwegians or only reinforce an artistic and linguistic subservience? The two writers could not agree about the effects; their acrimonious and much-publicised conflict continued to shape discourse about the stage well into the second half of the century.Footnote 16 Henrik Ibsen (who served as director of the Christiania Theatre from 1857 to 1864) and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (who occupied the role between 1865 and 1867) were still contending with these same issues more than two decades later. They wanted to show that Norway's stage was neither provincial nor dominated by outside forces – all the while working with limited resources and an extremely conservative audience.Footnote 17 Ibsen was so embittered by the difficulties he encountered that he would refuse to have anything to do with the Theatre in later years: ‘My experiences and memories of the theatre in Norway are not such that I feel any inclination to repeat them.’Footnote 18

It was inevitable that the musical stage should also be scrutinised in terms of its ‘Norwegianness’. When the Swedish director Ludvig Josephson arrived at the Theatre in 1873, he acknowledged the desire for operas ‘sung in Norwegian by Norwegian singers’, but there were simply not enough available musicians to stage such productions.Footnote 19 There was a large number of trained Norwegian singers but almost all of them were living and working abroad since there were few regular opportunities in the country. Under the circumstances, Josephson had to rely on foreign talent, such as his fellow Swede, the tenor Fritz Arlberg, who sang the leading male roles. Yet, as Josephson assured the Theatre's Board of Directors, Alberg was teaching young Norwegian singers who would soon be able to appear on stage.Footnote 20 Oselio was one such promising singer.

Like most middle-class girls, Oselio had been taught to play the piano and to sing. Her unusual vocal abilities were first remarked on by two artists who lodged across the street from the Aas family: the opera singer Camilla Wiese (1835–1938) and the actress Johanne Juell (1847–82). Wiese, who had been a student of Pauline Viardot, and Juell, soon to play Nora in the first Norwegian production of Henrik Ibsen's At dukkehjem, understood the importance of professional training. They arranged for Oselio to take lessons with Arlberg and later secured her debut performance at the Klingenberg Festal in Christiania. This venue was part of the city's Tivoli Gardens and invariably drew large audiences. The occasion would be an important one for Oselio, although Juell was undoubtedly the central attraction.Footnote 21 On New Year's Day in 1877, the actress recited works by Wergeland, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and Erik Bøgh; Oselio sang three short art songs – ‘O bitt’ euch liebe Vogelein’ (Ferdinand Gumbert), ‘Skjuts-gossen på hemvägen’ (Adolf Fredrik Lindblad) and ‘Romance’ (Albert Rubenson).Footnote 22 While her part was small, it brought her name before both the public and the critics, who complimented the unusual power of the young singer's ‘pleasant voice’.Footnote 23

To further her education, Arlberg sent Oselio to study in Stockholm with the soprano Frederika Stenhammar (1836–80). Oselio arrived in autumn 1877 and the Norwegian press made a point of documenting her progress. Dagbladet reported her success in 1879 at a church concert in Visby, where she was ‘brilliant’ and ‘particularly promising’.Footnote 24 That same year, Oselio was among the recipients of a stipend from the Storting to fund her education, and on 10 December 1879, she made her operatic debut as Leonora in Donizetti's La favorite at the Royal Opera. This was not an unequivocal triumph; critics praised the colour of her voice but noted that she had ‘much immaturity’ and needed more ‘proper training’ as her voice ‘lacked what is called equality’ – presumably meaning that she struggled to balance her upper and lower registers.Footnote 25 Further lessons with Stenhammar and more experience at the Royal Opera would help Oselio to address these issues. During the next two years, her roles included Ortrud in Wagner's Lohengrin, Simone in Delibes's Jean de Nivelle, Amneris in Verdi's Aida and Zinka in Siegfried Saloman's Karpathernas ros. This was ambitious repertoire for such a young singer and must have suggested that she could enjoy a very successful career in Sweden. Yet Oselio did not seem satisfied with this prospect. In 1881, she left Stockholm for Paris, where she became a pupil of Mathilde Marchesi.

Marchesi, considered one of the most effective pedagogues of the period, promised to prepare singers for careers on the most important opera stages in Europe and the United States. Oselio would be among the first students at the École Marchesi and she would receive lessons in singing, languages, stage deportment and mime. The ballet dancer Lucien Petipa led the deportment class while Édouard Plaque, the régisseur de la danse at the Paris Opéra, taught mime.Footnote 26 Oselio first demonstrated the effectiveness of this combined instruction in the spring of 1882, when she sang in a benefit concert at the Salle Érard.Footnote 27 On this occasion, she featured in duets from Mozart's Così fan tutte and Rossini's La regata veneziana with Marchesi's Swedish pupil Georgina Sommelius. The periodical Le ménestrel praised the ‘beauty of their voices’ and their ‘method’; the Marchesi training had resolved Oselio's troubles with registration and helped her voice to reach full maturity.Footnote 28 Yet while they commended her abilities, French critics could not make any sense of the surname Aas, spelling it phonetically as ‘Osz’.

Marchesi was a shrewd businesswoman who understood that a voice was not enough in itself.Footnote 29 Her own memoirs presented herself as a devoted daughter, wife and mother, ‘inspired with enthusiasm for the art to which I have consecrated my whole life’.Footnote 30 Such spiritual language masked the ruthless tactics with which she managed her work, her finances, her rivals and her students. She insisted that young singers must be attentive not only to their vocal abilities but also to their physical appearance and to the name under which they performed. Nellie Melba, who also studied with Marchesi in Paris, recalled:

That reminds me of something which, perhaps, I should have mentioned before – how I came to take the name of Melba … the reason I adopted it was just because Madame Marchesi told me that if I were to appear under the name of Mrs. Armstrong, I should have an eternal handicap all my life. ‘But why?’ I asked her. ‘Surely if I am called Armstrong, or Mary, or Jane, I shall sing just the same?’ She shook her head and told me I must think of a name.Footnote 31

Such details were essential in the creation of the diva. A name that was evocative but still intelligible gave the singer an advantage. ‘Armstrong’ seems to have been too ordinary for Marchesi; ‘Aas’, on the other hand, was likely too unusual and difficult to pronounce.Footnote 32 Yet a singer's name, and a female singer's name in particular, was not merely a matter of what would be amenable for the stage and attractive to the audience. Marchesi herself referred to such names as the ‘nom de guerre’, a metaphor that acknowledged the difficult battle within the profession.Footnote 33 Yet it also acknowledged the conflict between the private woman and the public artist. For Susan Rutherford, a female singer was both: ‘two separate identities – and of the two, the “artist” was by far the most important’.Footnote 34 The stage name could create a clear distinction, allowing the private woman to adhere to the conventions of nineteenth-century femininity while the public artist pursued her career. As a result, these names did not necessarily erase a singer's identity but extended, refined and even protected it. Whether Marchesi herself invented the name ‘Oselio’ or only recommended that the young Norwegian adopt a different name, the French spelling probably provided the inspiration for this ‘nom de guerre’.

Oselio did not appear concerned about preserving the separation between her public and private lives. The Swedish artist Elizabeth Keyser, then a student at the Académie Julien in Paris, painted the young singer that same year and titled her work ‘Gina Oselio, souvenir amical’, implying that the Norwegian used the name not only on the stage but also off.Footnote 35 Oselio scribbled it across the top of her own scores and it was this name that would later be stamped on the covers of bound volumes of print and manuscript music in her private collection.Footnote 36 She was about to make her Italian debut at the Teatro dei Concordi in Padua, so her new ‘nom de guerre’ had an immediate practical purpose. At the same time, she continued to exchange letters with a range of correspondents as ‘Ingeborg Aas’ and her diary entries from this period suggest that Italians and Scandinavians knew her by both names.Footnote 37 Oselio never sought to conceal her national origins, as some of Marchesi's students did. She was Norwegian but she did not seem interested in cultivating this feature as a professional advantage.

Cultivating an identity

During the nineteenth century, Scandinavia came to represent a mysterious, ancient or Romantic ‘North’ for many Europeans.Footnote 38 Such northern exoticisms rarely distinguished between the three nations beyond superficial observations. Travelogues, literature and art tended to both idealise and conflate the three national identities. At the same time, Norway was considered to be the most ‘Northern’ of these northern nations. As historian H. Arnold Barton has explained, ‘There lay Scandinavia's most sublime scenery and most archaic ways of life in remote mountain valleys and along distant fjords. …[there] the past seemed closest to the present.’Footnote 39 The Norwegians, in other words, were the most authentic Scandinavians.

These beliefs about Norway appealed to many Norwegians, as Toril Moi has illustrated in her study of Ibsen's self-image. The writer positioned himself as ‘a natural genius emerging from the wild mountains of his homeland, uninfluenced by European cultural and intellectual life’.Footnote 40 Within this paradigm, Ibsen (and other Norwegians abroad) exploited their own provincialism, highlighting the contrast between their rural origins and the cosmopolitan contexts in which they now found themselves. ‘How interesting they are, these people who have come so late to artistic life, these alleged “barbarians”, who seem to have so much to teach us, and with whom contact should rejuvenate us!’ declared one French author.Footnote 41 By calling attention to their nation's ‘archaic ways of life’, Norwegians could transmute barbarism into an attractive exoticism. Ibsen, despite spending most of his career outside Scandinavia, knew that he was no ‘well-educated intellectual from the European urban bourgeoisie’, in the words of Toril Moi, and he could not become one.Footnote 42 Rather, as a contemporary critic put it, his talent was to look inwards, ‘for the prejudices at home, for everything that is old and obsolete in Norway’.Footnote 43

Oselio was looking outwards. While still in Stockholm, she was very much aware of the accomplishments of the foreign singers who appeared as guest artists at the Royal Opera and she judged herself in comparison with those performers, rather than her Scandinavian peers. When Frederika Stenhammar was dying, Oselio asked whether she could be as great as Zelia Trebelli.Footnote 44 Naturally, Stenhammar assured her that she could and Oselio was eager to show that this was true. She did not view herself as inevitably provincial, either professionally or personally, even if she did come from Europe's cultural periphery. The brief diary entries from her early years in Italy mostly document the quotidian elements of a singer's life: rehearsals, performances, cast changes, encores (or lack thereof). Yet they also document her contact with a wide variety of figures including Frans Lindstrand, the Swedish envoy in Rome, and his wife Hedvig Thyselius; the pianist and composer Giovanni Sgambati; the Norwegian author Elisabeth Schøyen; and Sir John Saville, the British ambassador to Italy. She describes visits to the Papal Basilica (‘to hear the music’), to the Italian parliament (‘It was extremely interesting’) and to the Palazzo Doria (‘a lot of paintings by Poussin, Rubens, Titian, Raphael’).Footnote 45 She is thrilled to discover that she has been engaged for an entire year in Budapest: ‘The great step forward! God, what a time of … emotion!’Footnote 46 She visits Lago Maggiore where she is delighted to be reunited with her ‘dear old friend’ Georgina Sommelius, who had come with her from Sweden to study with Marchesi and was now married to the Italian opera singer Osvaldo Bottero.Footnote 47 The diary communicates no sense of herself as an ‘alleged barbarian’. She is an active participant in the musical and social milieus in which she found herself.

Oselio had at least one opportunity to return to Scandinavia during this period, which she declined: ‘When one thinks of making a name for oneself in the world, it is as little use to celebrate triumphs in Scandinavia as it is in the Sahara desert.’Footnote 48 The Sahara metaphor might seem to evoke the image of the remote and barren landscape from which the Norwegian artist emerged, but Oselio probably had something much more practical in mind. If she returned to Scandinavia, there were comparatively few venues in which she might sing. She was much more likely to advance her career by remaining abroad, where she could see and be seen by impresarios, conductors and journalists.

In 1885, the Italian periodical Scena illustrata devoted a full page to Oselio's life and career.Footnote 49 This survey more than any other highlighted her Norwegian identity – and even introduced her with her real name. It placed Oselio within a Swedish framework, comparing her with Swedish singers and discussing her training in Stockholm at length. Of course, Sweden was the context in which Oselio had received her first formal musical experiences. When Scena illustrata noted that Norway had produced few famous singers in comparison with Sweden, this observation was not intended to demonstrate how a Norwegian singer might differ from a Swedish one. Rather, it underscored Oselio's Nordic rarity, her ‘Northernness’, not her ‘Norwegianness’. This ‘blonde daughter of the North’, as one critic called her, did not symbolise a nation but an idea.Footnote 50 That idea, however, had little practical relevance to her growing career. Italian reviews rarely mentioned her nationality and focused from the beginning on her excellent voice:

a warm tone, good timbre and above all a talent for interpretation, a liveliness of feeling, they promise the Italian Theatre a true artist. If on debut she showed herself so much mistress of the stage and so well educated in singing, what will be next? My most sincere congratulations to Miss Oselio.Footnote 51

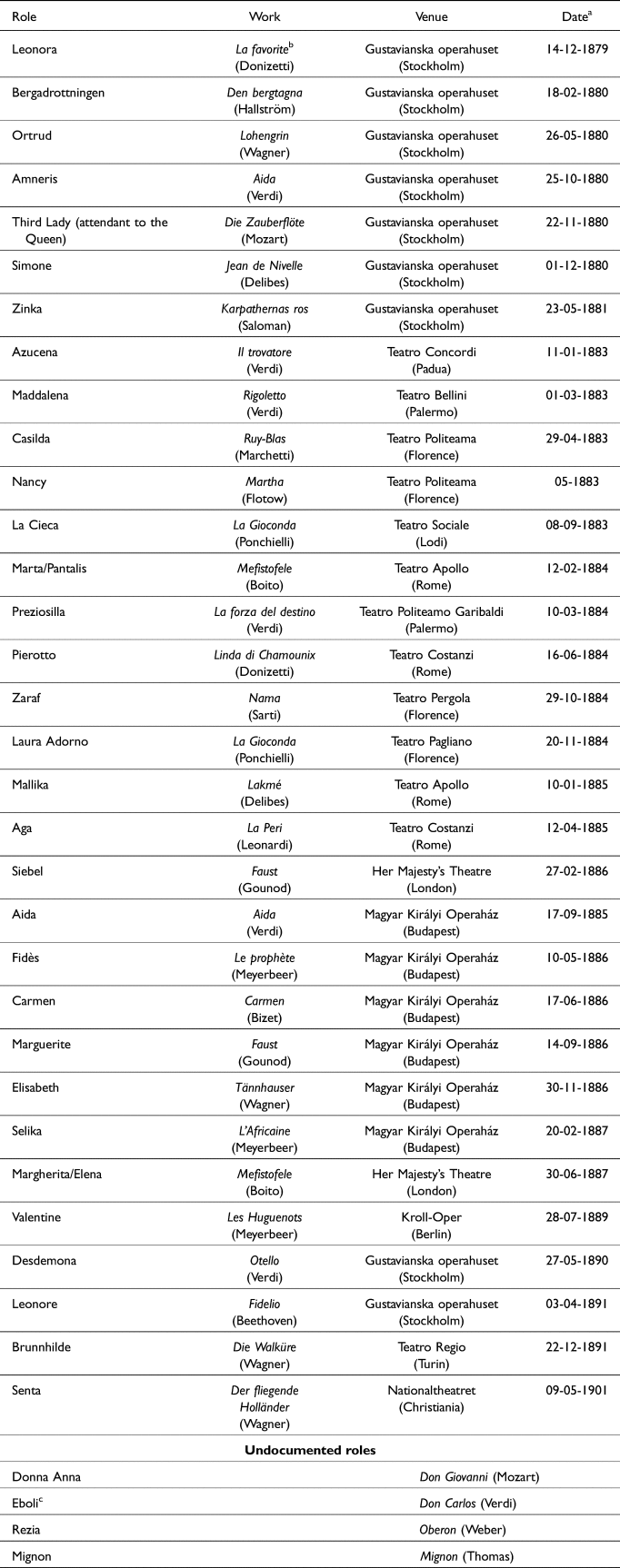

Oselio's Italian debut had been arranged by the impresario Pietro Galletti, who had a personal penchant for Scandinavian art and artists (he would later complete the first Italian translation of Et dukkehjem).Footnote 52 He advertised the singer as both ‘contralto and mezzo soprano’ and her repertoire (Table 1) reflected her ability to handle roles in either voice type.Footnote 53

Table 1. Gina Oselio's operatic repertoire, 1879–1901

a The date of her first documented performance of the role is given here but it is possible that Oselio may have sung each role at an earlier time or in another theatre.

b This opera was performed under the title ‘Leonora’ in Stockholm.

c Images of Oselio costumed for the role of Eboli exist, which implies that she did sing this role. There is no further documentation for this performance. See ‘Gina Oselio som Eboli’, OB.F15541c, Oslo Museum.

It also provides some sense of her vocal range. In 1883, for instance, she sang the contralto role of La Cieca in Ponchielli's Gioconda, whose central aria, ‘Voce di donna’, spans a♯ to g1. The following year, she appeared as Laura Adorno in the same opera, a mezzo-soprano part that reaches to a2. Then, in 1885, she sang Aida, and probably produced the exposed c3 in ‘O patria mia’. However, she sang that role only once, perhaps because its tessitura truly exceeded the comfortable limits of her voice. One London critic, hearing her in Boito's Mefistofele in 1887, felt that her focus on higher repertoire had come at the cost of her lower range:

Mdlle. Oselio made a considerable success … two years ago. At that time she was a contralto. Now she reappears before the public a mezzo-soprano, and, what is more wonderful still, her low notes have lost the sonorous and sympathetic quality which her middle and upper registers have acquired. From [middle] C to the upper F, or perhaps G, her voice is of singular beauty. Below that it is colourless, not to say harsh, assuming frequently the quality of what the French call voix blanche.Footnote 54

This critic drew a parallel between Oselio and the Polish singer Jean de Reske, who began his career as a baritone and ended as the star tenor of the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Oselio had not actually changed her fach. She was a mezzo-soprano but a versatile one and perceptions of her voice varied according to the roles she sang. While she was still in Sweden, she had been variously classified as ‘dramatic soprano’, ‘mezzo-soprano’ and ‘high soprano’.Footnote 55 Her repertoire revealed her willingness to exploit this flexibility, in terms of both range and style. The unusually dark timbre of her voice, which Marchesi later remembered as ‘about the most beautiful [yet] the strangest she had had to work with’, made these experimentations memorable if not always successful.Footnote 56 By 1888, according to Nordisk musik-tidende, she had sung twenty-two roles in eighteen theatres.Footnote 57 The actual number was much higher.

During this period, Oselio was engaged all over Italy, at venues in Rome, Venice, Florence, Milan and Padua, as well as numerous smaller cities. As noted earlier, she had made her London debut in 1886 (under the impresario James Henry Mapleson) and her Spanish debut later that summer at the Teatro Principal in Valencia. She was contracted for two consecutive years in Budapest (1885–6 and 1886–7) and she sang Carmen there for the first time on 6 June 1886. Oselio performed her part in Italian, which meant that some of the other principals had to sing in the same language while the remaining cast sang in Hungarian.Footnote 58 This practice was a familiar solution for opera houses at Europe's borders that wished to engage guest stars. Such stars, often booked for limited engagements, could not be expected to learn their part in the local language. Oselio herself had participated in several dual-language productions while she was still in Sweden. In this specific case, Hungarian audiences were already conversant with the work (two earlier stagings had been performed in Hungarian) and they seemed to have no difficulties understanding the juxtaposition of languages. Critics recognized that Oselio sang ‘tastefully’ and ‘with good musical sense’, although they were less certain about her interpretations.Footnote 59

The Times critic characterised Oselio's dramatic approach as ‘above all, unconventional. Her movements, her gestures are absolutely free of the routine of the stage.’ This did not mean that they were always appropriately applied: ‘The classical dignity of Helen of Troy was less in accord with the naturalism of the lady's style.’Footnote 60 Italian critics perceived her more favourably, describing her acting as ‘artistically faultless … severe but without vulgarity’.Footnote 61 The comparison with de Reske, whose ‘internationalism of technique and approach’ made him appealing to many different audiences, was a good indication of what Oselio had achieved.Footnote 62 She had formed herself into a truly cosmopolitan singer. She was still Norwegian, of course, but ‘Norwegianness’ remained a feature of her biography. It was not a distinguishing feature of her artistry.

Asserting ‘Norwegianness’

If Oselio had not paid much attention to Norway, the country had certainly not forgotten the singer. All of her triumphs were detailed in the local press, often with very specific information about the amount that she was to be paid and the number of encores that she had received.Footnote 63 Yet it was Denmark and Sweden, rather than Norway, who finally persuaded the mezzo-soprano back to Scandinavia in 1888. Oselio was engaged to sing Carmen first in Copenhagen, then in Stockholm; the concerts in Norway would take place during the interim. For these, the singer chose highlights from her operatic repertoire: the seguidilla from Carmen, ‘Ocean, thou mighty monster’ from Weber's Oberon, ‘O don fatal’ from Verdi's Don Carlos and ‘Stella del marinar’ from Ponchielli's Gioconda. To balance this demonstration of virtuosity, Oselio prepared several Norwegian songs, including Johan Selmer's ‘Modersorg’ (op. 22, no. 8), Johan Svendsen's ‘Schlag die Tschadra zurück’ (op. 23, no. 5), Halfdan Kjerulf's ‘Synnøves sang’ (op. 6, no. 3) and Grieg's ‘Jeg elsker dig’ (op. 5, no. 3). Art song was, of course, one of the ways in which a singer might stress their own national character and both Christine Nilsson and Jenny Lind frequently programmed Swedish folksongs to highlight their ‘exoticised Northern cachet’.Footnote 64 While Oselio had not exoticised herself for foreign audiences, she clearly expected that this repertoire would appeal to the Norwegian public. In this context, a cosmopolitan repertoire and a national repertoire could complement one another.

The public adored these performances; the critics were wary. They praised her voice, but they had no intention of allowing Oselio to reassert her identity as a truly Norwegian musician: ‘She is a dramatic and – though Norwegian-born – foreign – Italian singer. … In Grieg's “Jeg elsker dig” … the performance was hardly in accordance with the composition's character. … No, Oselio was after all Norwegian born, so she felt obliged to be a little patriotic in her programme.’Footnote 65 It was not enough, at least for this author, for Oselio to have been born in Norway. These songs belonged to true Norwegian artists, not ‘divas who had been practicing their art before the footlights on the great foreign stages’ and who could not capture the ‘sæterduft’ (literally ‘mountain pasture scent’) of their native country.Footnote 66 Oselio, as a foreign dramatic singer, had no right to sing this music. The critic wondered why the mezzo-soprano had not been included in the Christiania Theatre's operatic season, where she would have been more properly presented with other foreign artists. Another critic acknowledged that after so many years abroad, it was not to be expected that Oselio would still sing fluently in Norwegian. As a result, ‘songs such as Grieg's “Jeg elsker dig”, Kjerulf's “Synnoves sang” and the folk tune “Ola, ola min ejen onge” therefore give the impression of being sung by a foreigner, who has learned our language’.Footnote 67

Oselio's response to this censure was swift and decisive. The first signal that she intended to assert her Norwegian identity occurred just a few weeks later in Stockholm. On 11 November 1888, the playbill announced that the role of Carmen would be ‘performed in the Norwegian language by Miss Gina Oselio’.Footnote 68 During her subsequent appearances, Oselio would alternate between Norwegian and Italian. Given the significant degree of mutual intelligibility between Norwegian and Swedish, Oselio's use of the former probably made little difference. The press instead focused on her characterisation of Carmen, finding it repulsive. Despite a voice of great beauty and power, she had ‘done violence to the illusion’ of the stage, appearing as a ‘small, almost red-haired, middle-aged … demi-monde lady, a “Daughter of the Regiment” in the worse sense’.Footnote 69 Swedish perceptions of Carmen had been formed by a different Norwegian singer: Olefine Moe (1850–1933), who premiered the role in Stockholm in 1878. Moe accentuated the coquettish, charming nature of Bizet's gypsy, which she portrayed with ‘intelligence and taste’.Footnote 70 Critics were not prepared for the unrelenting candour of Oselio's performance, an interpretation that demonstrated why ‘not even our most advanced contemporary composers [have] dared to advocate any stronger realism in their operas’.Footnote 71

Oselio's Carmen was probably not more shocking than other contemporary realisations.Footnote 72 However, the Swedish response illuminates the style in which she sang opera and the dramatic effect she achieved. Oselio had never been conventionally beautiful; she was short, red-haired and now past her thirtieth birthday. If these physical attributes made her less appealing to some, they foregrounded both her tremendous vocal abilities and her determination to employ them for specific artistic ends. The public, as the singer later said, imagined that Carmen should be ‘sweet and graceful. This is not true, not right!’Footnote 73 To be true to the character and to life, Oselio's Carmen must disgust, frighten and even repulse the audience. Images of Oselio in the role suggest some of the ways in which she accomplished this goal. In contrast with Moe, who is pictured reclining at a distance (Figure 2), Oselio's poses employ a specific physical vocabulary (Figures 3 and 4) with deliberate meaning:

Her undulating hips and swelling bosom are explicit signifiers of the sexual body; less obvious to the modern spectator, perhaps, is the significance of Carmen's elbow. In the vast majority of portraits, Carmen stands with one arm akimbo, a pose that has complex connotations. … By the seventeenth century, it was a common marker of male authority. In female portraiture until the twentieth century it was used – and then only rarely – in pictures of women transgressing codes of femininity through either low social status or the assumption of power.Footnote 74

Figure 2. Olefine Moe as Carmen (courtesy of Oslo Museum). (colour online)

Figure 3. Oselio as Carmen (courtesy of Oslo Museum). (colour online)

Figure 4. Oselio as Carmen (courtesy of Oslo Museum). (colour online)

Oselio knew that her Carmen would be different from that of Moe because she had seen Moe create the role in 1878. Oselio judged the other singer to be ‘very beautiful, dark, exceptionally graceful’, with a ‘pretty voice’.Footnote 75 Given Oselio's own stated comments about sweetness and grace, this was not necessarily praise. Swedish audiences had experienced several different Carmens in the intervening decade, including Dina Niehoff (1879), Pauline Lucca (1886) and Adèle Almati (1887). Those interpretations were not uniform, but they were in one way or another more restrained. Like the American Minnie Hauk, who wrote that ‘Carmen is wicked, and my Carmen revelled in wickedness’, Oselio's Carmen embraced her low social status (hence the reference to her as a member of the demi-monde) and her power (the violation of dramatic norms on stage).Footnote 76 She seduced Don José with her ‘catlike caresses’ and then tossed him away ‘like a squeezed lemon’.Footnote 77

Swedish audiences found this Carmen deeply uncomfortable and totally compelling. Norwegian newspapers were quick to report that she had received ten curtain calls and several ‘expensive bouquets’ on the first night and to emphasise that this had happened after she sang the opera in her native language.Footnote 78 At the end of 1888, King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway appointed Oselio as the first kongelige norsk hofsangerinde (royal Norwegian court singer), an honour that acknowledged her importance to the dynastic union as a whole and to Norway in particular.

The decision to sing Carmen in Norwegian was also a deliberate statement about how Oselio now wished to be perceived. What prompted this sudden volte-face towards Norway? Her critical reception must have been a motivating factor; it seems to have been a surprise for her to discover that she was a legitimately cosmopolitan singer but not a legitimately Norwegian singer. At the same time, her appeal to the Norwegian public could not rest solely on her national origin or on ‘little patriotic’ signals such as her Christiania concerts. Her dramatic persona, as the Swedish reviews demonstrate, revealed an affinity with ‘the strong currents of realism and naturalism’ in the country's literature and visual arts, which, as Nils Grinde observed, still exerted ‘little influence on Norwegian composers’.Footnote 79 The effects of ‘the modern breakthrough’, to employ Georg Brandes's famous phrase, were easy to trace in literature, drama and painting but harder to identify in musical works.Footnote 80 This dissonance between music and the other arts became increasingly marked in the final decades of the century, with opera often dismissed as mere entertainment, a vehicle for elaborate sets and costumes but without any artistic substance or national merit. The prevalence of light opera, always easier to cast and to stage, enhanced this perception.

When Ibsen had reflected on his experiences of the Norwegian theatre in 1884, he concluded that ‘opera requires less culture from its public than the drama’, telling Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson:

Therefore it flourishes in the large garrison cities, in the mercantile cities, and wherever a numerous aristocracy is gathered. But from an opera public may be gradually developed a dramatic public. And for the theatre's staff, also, the opera has a disciplinary power; under the baton the individual has to place himself in perfect submission.Footnote 81

Ibsen's notions about the utility of opera were understandably informed by his personal experiences with the Christiania Theatre. Yet his comments echoed a broader belief that the opera stage would always remain subservient to the dramatic stage, an attitude that Børre Qvamme attributes to the influence of Danish critic Edvard Brandes, the younger brother of Georg Brandes.Footnote 82 Edvard Brandes's commitment to naturalism (‘there is nothing that is immoral except that which is untrue’) encompassed the entire theatrical enterprise, including the mise en scène.Footnote 83 Operas that disregarded the demands of verisimilitude, as most did, could not fit within Brandes's conception of modern drama.

Oselio's interpretive style, however, suggested that an artist might sing in a ‘realist’ manner.Footnote 84 Opera as a genre might never achieve Brandes's ideal but operatic interpretation could still seek ‘realist’ expressions. Carmen was uniquely useful in this regard since it had been associated with literary and artistic realism ever since its Parisian premiere. This association was strengthened by those singers who insisted that they had studied ‘real’ cigarette girls to create ‘real’ representations of these characters, ‘shirking nothing, toning down nothing’.Footnote 85 Such ‘realist’ treatments of Carmen took many forms but the degree to which they were understood as authentic was always linked to the local context in which they were received. In 1888, a Norwegian singer performing the role in Scandinavia would inevitably invoke associations with ‘Progressive Norway’, the Norway of Ibsen's Et dukkehjem, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson's Det flager i byen og på havnen and Amalie Skram's Constance Ring, the Norway of the liberated woman.Footnote 86 While for Sally Ledger this literature tended to ‘diagnose women's ills rather than propose cures … with few feminist victories’, Oselio's Carmen moved beyond diagnosis to reveal a character entirely unfettered by moral or social constraints.Footnote 87 A Norwegian Carmen was therefore not only a statement of national identity but also assumed a very specific position within ‘Norwegianness’. The Swedish audience was too focused on Carmen's scandalous elements to observe these fine distinctions. Yet Norwegians would recognise that Oselio belonged with those artists and musicians who decisively rejected a romanticised idealism. Her focus on what was ‘true’ and ‘right’, regardless of how palatable it might prove to be, suggested that she would be eager to participate in the changes that were beginning to take place on Norway's stages.

Oselio's Norwegian operatic debut, which she made in 1890, and her unfolding romance with Bjørn Bjørnson (then employed at the Christiania Theatre), enhanced this image of the mezzo-soprano. Music critic Otto Winter-Hjelm praised her ‘natural’ performance as Marguerite in Gounod's Faust, in which she captured both the innocence and the eroticism of the character.Footnote 88 The only flaw was the language, since the opera had to be presented in Swedish to accommodate the ensemble. Although the other principals were Norwegian by birth – Wilhelm Kloed (Faust), Bjarne Lund (Méphistophélès) and Hans Brun (Valentin) – they lacked the confidence to attempt a Norwegian or even a dual-language production, having very little time to rehearse.Footnote 89 This was particularly distressing after Oselio's appearance in Sweden. ‘That she sings the part in a foreign language … is humiliating … but it absolutely cannot be blamed on her’, concluded one critic.Footnote 90 Still, if Norwegian musicians did not insist on singing in their native language at home, how could they expect to be allowed to sing in it elsewhere? ‘For the sake of their own dignity’, observed another, ‘Norwegian artists visiting Sweden should demand to sing in their own language. … Norwegian artists should not contribute to the Norwegian being considered somewhat inferior’.Footnote 91 The solution to these difficulties had to be a ‘permanent national opera’.Footnote 92

Edvard Grieg heard Oselio's operatic debut and was much impressed by her voice. Afterwards, he went backstage with Bjørnson to express his admiration. The singer received him so warmly that Bjørnson, observing their interaction with increasing displeasure, finally interrupted: ‘you must remember that it is ME she is in love with’.Footnote 93 Grieg found this very funny in retrospect. Did Bjørnson really imagine him as a potential rival? The young actor-director had nothing to fear; Oselio was most certainly in love with him (although they would not be able to marry until 1893) and this must have enhanced Norway's appeal for the singer. Yet the attraction between the two artists was more than personal. Bjørnson had intended to pursue a musical career and he had enrolled at the Vienna Conservatory to study composition and conducting.Footnote 94 His musical ambitions soon disappeared under the influence of Maximilian Streben, who taught acting, and the Norwegian left the Conservatory to become Streben's private pupil. Streben's approach reinforced Bjørnson's commitment to the naturalistic stage and expanded his understanding of how such naturalism might be pursued.Footnote 95 Professional engagements in Germany and Switzerland cultivated his skills as actor and director. When Bjørnson returned to Norway in 1884 to take a position at the Christiania Theatre, he was eager to put both his dramatic and his musical training to good use.

In spring 1888, he produced the first opera performed entirely by Norwegian singers: Gounod's Faust with Lona Gulowsen in the title role. The next step, declared the newspaper Dagbladet, should be a Norwegian-language opera composed by a Norwegian.Footnote 96 Bjørnson did not have such an opera to stage, but he did have Oselio. They agreed that their first collaboration together would be a production of Carmen. It would be performed at the Christiania Theatre with an all-Norwegian cast and sung – of course – in Norwegian. The nation had heard Carmen before: a single performance in 1883 starring Olefine Moe – the very same production that Oselio had seen in Stockholm. It made little impression on critics or audiences. The Oselio–Bjørnson Carmen was to be entirely different.

While Oselio sang in Switzerland, preparations took place under Bjørnson's careful supervision. Jens Waldemar Wang, the head scenographer at the Theatre, designed all new sets and costumes based on original models from the Opéra-Comique in Paris.Footnote 97 The ballerina Augusta Johannesén choreographed the gypsy dances in the second act (with a solo for herself) and the conductor Johan Hennum presided over a full orchestra including, as newspapers reported, ‘harp and English Horn’, a detail which suggests that the earlier performance had been undertaken with reduced forces.Footnote 98 Some of the singers from the Faust production were booked again, with Wilhelm Kloed as Don José and Bjarne Lund as Escamillo. The young soprano Thora Nielsen-Trost would make her debut as Micaëla.

In her recent survey of Carmen in the Nordic countries, Ulla-Britta Broman-Kananen suggests that Bjørnson may have employed the Danish translation to prepare the Norwegian libretto.Footnote 99 Unfortunately, no libretto has survived from the production. If Bjørnson did use it, then the Norwegian audience would have heard, in Broman-Kananen's view, a Carmen set ‘firmly within the frames of a conservative idealism’ with love as a ‘simple competition’.Footnote 100 Such idealism would have been complicated both by Bjørnson's preferences for theatrical naturalism and by Oselio's realist approach. There was no libretto offered for sale at the Theatre ticket counter (located inside Ole Olsen's music shop), although Olsen's rival, Carl Warmuth, did advertise one in an unspecified language as well as musical scores with original French texts. Prosper Merimeé's novel was also published as a cheap paperback in the Bibliothek for de tusen hjem (library for a thousand homes) series that same year, giving Norwegians the opportunity to compare the opera with its original source materials.Footnote 101

Carmen was an enormous success. On 15 May 1891, Oselio was ‘splendid’, with an ‘inexhaustible’ and ‘extraordinary’ voice.Footnote 102 It was clear that Norwegians would receive this differently from other Scandinavian audiences:

The Swedes and the Danes have criticised the manner in which she plays the role. Namely, she emphasises the wild, the brutal nature of this half-civilised Spanish Gypsy coquette, and … she brings her countrymen, at least most of them, to this conception [of the role]. … Carmen is no society lady, but simply a suggestive, overconfident woman boldly playing with love.Footnote 103

Even if not all the countrymen (and women) were convinced, there was no question now of her foreign nature. Oselio had finally accomplished what Ludvig Josephson had promised the Theatre so long ago: opera sung in Norwegian by Norwegian artists. ‘The box office was mad with joy’, recalled Bjørnson, and the conductor Hennum told the director: ‘Oh my God, to be allowed to stand at the desk and conduct these evenings. I do not sleep all night. I do not have time. I hear only the delicious voice. I lie [awake] and am happy.’Footnote 104

Engaging roles

Carmen re-established Oselio's ‘Norwegianness’. It also established the particular way in which she intended to deploy that ‘Norwegianness’ on the country's stages. After Bjørnson and Oselio married in December 1893, the new couple undertook a series of tours throughout the country. During these ‘soirées’, as they were advertised, Bjørnson gave dramatic readings and lectures while Oselio sang selections from her stage and concert repertoire. She programmed a few new Norwegian songs (such as Catharinus Elling's ‘Aabne vande’, which she performed from the manuscript), but she always sang her best-known arias from Mefistofele and Carmen.Footnote 105 The tours took the couple well beyond Christiania; in 1894, for instance, they visited more than thirty small towns along the coast. These first-hand encounters with Oselio's voice, combined with reports of her operatic triumphs, solidified the singer's image outside the capital and through the nation at large. Rural Norwegian audiences did not only hear about her, but also about her voice. In this respect, the tours were as important as her opera performances in confirming her as national ‘star’, a role in which the entire country could affirm and appreciate her.

Norwegian musicians responded eagerly to her presence. Magdalena Bugge (1846–1923), Michael Krohn (1867–1918), and Mon Schjelderup (1870–1934) were some of the artists who sent Oselio their scores with personal inscriptions – ‘in gratitude from the one whom no one knows’, ‘to my dearest Mrs. Bjørnson’ and ‘from your devoted Michael’.Footnote 106 Bugge, sending Oselio one of her earliest works, scrawled at the bottom of the cover: ‘The three songs in manuscript and the very last “The Dying Child” will be sent as soon as I have transcribed it’, alluding to what would later be published as her Opus 10.Footnote 107 Nearly all of these pieces were typical nineteenth-century art songs, focused on themes of nature, romantic love or motherhood. Their diatonic melodies occasionally incorporate modal elements, providing the expected national ‘colour’. They are short and uncomplicated, tributes rather than vehicles for a professional singer.

Grieg was the most obvious potential collaborator, but even Oselio could not overcome his well-documented difficulties in writing for the opera stage. He dedicated the orchestrated setting of his ‘Våren’ (op. 33, no.2) to the singer and she performed this on at least one occasion. Grieg's admiration for her voice was not always matched by his evaluation of her interpretive decisions.Footnote 108 ‘If it is to be O.’, wrote Grieg to the conductor Iver Holter while planning a performance of Olav Trygvason, ‘then for heaven's sake get her to stand still and dignified, as befits an old prophetess. There dare not be talk of her wiggling her hips, etc.!’Footnote 109 Clearly, Oselio could be too realistic, at least for Grieg's taste.

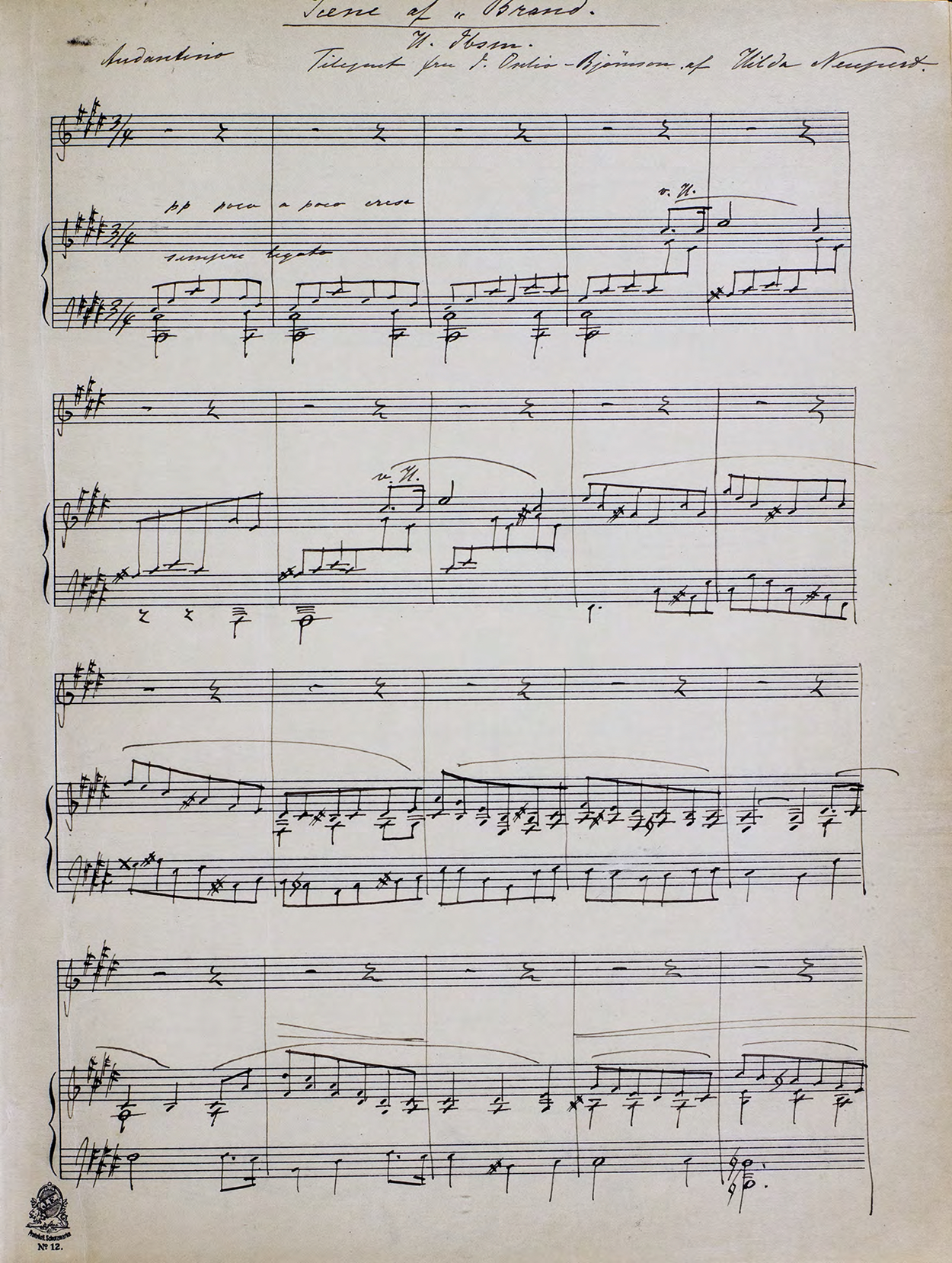

Hilda Bergh Neupert (1848–1934) attended one of the Oselio–Bjørnson soirées on Grieg's recommendation: ‘I heard Oselio and also thought very well of her lecture’, she wrote to him afterwards in 1895.Footnote 110 She sent the mezzo-soprano a few songs and then began to work on a larger project that would be composed for, and dedicated to, Oselio. Neupert entitled this new composition ‘Scene af Brand’ and based it on Ibsen's eponymous work from 1865 (Figure 5). Unlike the short compositions that Oselio received, this ‘Scene af Brand’ was a much more ambitious work. The piece has ten distinct sections for mezzo-soprano and tenor, each marked by tempo and metre changes, as well as certain passages designated ‘recitative’, suggesting that Neupert may have conceived this for staged or semi-staged performance. The ‘Scene’ draws on the text from the fourth act of Ibsen's poem, a dramatically compelling portion in which Agnes, Brand's wife, accepts her own inevitable death. Oselio must have valued this music to some degree – she preserved it, together with other print and manuscript music that she received, in privately bound volumes. Yet she never performed it. Instead, she continued to programme mostly well-known Norwegian composers (Grieg, Kjerulf, Svendsen and Elling) and her operatic repertoire.

Figure 5. ‘Scene af Brand’ by Hilda Neupert (courtesy Furman University Libraries). (colour online)

Composers such as Neupert may have hoped that Oselio would champion their work and she certainly had the opportunity to do so. Yet she seems to have been constrained by two factors. The first was her health. She had begun to experience recurring bouts of bronchitis in the 1890s, which temporarily yet seriously affected her voice. She was unable to sing at all during the winter season of 1896–7. These problems were probably exacerbated by the relentless pace she had maintained since her Italian debut. In 1889, for instance, she had begun the year with an appearance in Helsinki and then travelled on to St Petersburg, where she sang with the Imperial Music Society.Footnote 111 In February, she was on stage at the Mariinsky Theatre (singing Mefistofele opposite Fyodor Stravinsky) and then she spent March in Moscow, performing at the Hall of the Assembly of the Nobles. During June and July, she was engaged at the Kroll-Oper in Berlin, at the Stadttheater in Leipzig and with the Berlin Philharmonic.Footnote 112 In August, she was in the Netherlands to sing at the Kurhaus Scheveningen.Footnote 113 By October, she was back in Scandinavia to present concerts in Norway and Sweden. During November and December, she was engaged for Carmen, Faust and Tannhäuser at the Royal Opera in Stockholm. Detailed notes in her diary reveal the extent of her preparations for each trip abroad, with carefully recorded names and addresses of agents, impresarios, hotels, performance venues, journalists, accompanists, music shops and the local consulate.Footnote 114 Such a schedule (and its concomitant demands) was fairly typical for singers in the period. Nevertheless, Oselio could not sustain these efforts indefinitely.

In 1898, she wrote to Grieg that she was uncertain about whether she would be able to participate in the Bergen Music Festival as he had asked, not having performed publicly since May the previous year.Footnote 115 This was rather disingenuous, since she had sung at a concert in Paris arranged by the violinist Paul Viardot in July 1897. As it turned out, she was back on stage in September 1898, singing Faust at the Christiania Theatre. Yet Oselio was now obliged to be more careful of her voice and she seems to have become increasingly sensitive to criticisms during the 1890s – perhaps because she feared they might be true.Footnote 116

The second constraint was that having established her status in Norway, she now had to maintain her position. Concert tours, such as the ones she undertook with Bjørnson, were useful in this regard but they did not always show her to her best advantage. Grieg stated frankly that ‘singing art songs has never been her strength and it never could be, despite all her determination’.Footnote 117 The opera stage was Oselio's true habitat. From this perspective, Norwegian art songs constituted a flattering gesture with little practical utility. Neupert's Brand might have provided Oselio with better scope for her talents but the inherent difficulties in staging opera in Norway had not been resolved after the 1891 Carmen. In fact, Bjørnson had become so frustrated with the situation at the Christiania Theatre that he requested that the current director, Hans Schrøder, resign so that he, Bjørnson, could apply for the place.Footnote 118 When Schrøder declined to accept this proposal, Bjørnson promptly resigned his post.

This complicated the situation for the mezzo-soprano. Regardless of her health or her husband's attitudes, the Christiania Theatre remained the venue that she judged most suitable for her stage appearances, and she did not intend to be superseded there. Bjørnson's response to this and to Schrøder's other discontents was to pursue the creation of a new national theatre. It would be fully funded by the state and, pace Ibsen, no longer at the mercy of an indiscriminate public.Footnote 119 Thanks to his efforts, the Christiania Theatre and Schrøder were replaced by the National Theatre in 1899. During this interim period, however, Oselio still managed to exert influence over operatic performance at the Christiania. In the mid-1890s, the mezzo-soprano Sigrid Wolf tried to arrange a debut as Carmen at that theatre, having already sung the part in Stockholm. Her parents, Lucie and Jacob Wolf, had been employed there for decades and were well known in Norway as accomplished actors. Naturally, the Wolfs expected that Sigrid would be allowed to sing ‘on the stage where her parents had worked for so many years’.Footnote 120 The theatre management rejected all Sigrid's proposals, which Lucie Wolf bitterly resented: ‘there was always the answer that Oselio had … the right to it’.Footnote 121

Once the new National Theatre was founded, Oselio had the right to that too. On the last of the three opening nights in 1899, she appeared before the curtain rose, singing a new cantata by Elling in homage to the elder Bjørnson.Footnote 122 These gala events had been arranged specifically to signal what the National Theatre intended to be:

Nationaltheatret would foreground its literary roots; it would show work in Bokmål and not shy away from the Danish influence; and its repertoire would represent the best of both the old and the new. In short, it would represent an image of Norwegianness that leaned towards the cosmopolitan and the European and away from the rural, the regional and the local.Footnote 123

Oselio's operatic appearances at the new theatre expressed these ideals. They also expressed her pre-eminence. A satirical caricature by Gustav Lærum from 1900 depicts Oselio, Ibsen and the Bjørnsons on a sæter (Figure 6).Footnote 124 Oselio, in costume, is milking the cow (‘Nationaltheatret’) into a bucket (‘Carmen’), while Bjørn Bjørnson peeps timidly from the other side of the animal. Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson carries the milk away as Ibsen the cat laps up what has spilled. Other iconographic implications aside, it is obvious that Oselio, rather than Bjørn Bjørnson, is the one in charge of production. If the caricature was unflattering in one sense, it must have been satisfying in another: Oselio had established her right to be regarded alongside the Bjørnsons and Ibsen as a national artist. At the same time, she must have been aware that this position could not be permanent. As she approached her fiftieth birthday, she was also nearing the final stage of her operatic career. She had not sung abroad since January 1900 and those performances – although she could not have known this at the time – would be her last outside Scandinavia.

Figure 6. Caricature by Gustav Lærum, 1900 (courtesy Oslo Museum).

Her first roles at the National Theatre were in Faust and Carmen (1900), followed by new productions of Der fliegende Holländer (1901) and Il trovatore (1903). Holländer was a national premiere, and Senta was the final role that Oselio learned. Critics named her the best of the soloists, stating that she sang Senta with ‘brilliance and force’, calling forth the ‘greatest enthusiasm’ among the audience.Footnote 125 Yet her time at the National Theatre proved to be short-lived. At the end of 1903, Oselio's health worsened once again. The singer was obliged to have an operation on her throat, and this left her incapacitated for a considerable time. Attempts to sing again showed that she would not be able to resume her place on the opera stage. ‘The resonance is gone’, lamented Grieg in 1907, ‘the former lushness and drive have been replaced by cautious calculation.’Footnote 126

It was her marriage to Bjørnson, rather than her work or her health, that presented the greatest difficulties during this period. Oselio had never found it easy to assimilate within the larger Bjørnson family. Despite the mutual affection evinced in their letters, she did not possess the quick wit or the easy manners that would allow her to feel comfortable in the environment at Aulestad, the Bjørnson family home.Footnote 127 In his memoir, B.A. Bjørnson-Langen (the son of Bjørn's youngest sister Dagny) describes Oselio as humourless and conscious of her dignity, unable to understand the lively Bjørnson family. At the same time, Bjørnson-Langen acknowledges the difficulty of her position; his uncle was not ‘immoral but amoral’, and engaged in regular love affairs, causing the Bjørnson family to agree that he treated Oselio very badly. The ongoing infidelities coupled with Bjørnson's domineering personality placed an increasing strain on their relationship. Oselio wondered later if she would have been happier with a simpler, less demanding figure: ‘I should have been married to a little lieutenant’, she concluded.Footnote 128 Their partnership, both personal and artistic, had reached its apex and was now drawing to its conclusion.

Establishing opera

In May 1905, Oselio sang in her ‘last’ Faust at the National Theatre. She would appear again, including at a jubilee that honoured her forty-year career in 1917. Yet 1905 marked the final time that Oselio performed on stage as the reigning mezzo-soprano of the National Theatre. She could no longer prevent younger singers from taking on ‘her’ roles and Cally Monrad (1879–1950) was one of the first to do so, sharing Carmen with Oselio in 1904. Critics refrained from drawing direct comparisons between the two, although it must have been evident to the older singer that she could not compete with this newer, fresher voice.Footnote 129 Another blow occurred in 1907, when Bjørnson left both the National Theatre and Oselio to work in Germany. This separation would not be final until 1909, when Bjørnson asked for a divorce in order to marry his third wife, but their collaborations were at a definite end. Despite the challenges within their marriage, Oselio was deeply distraught by his departure, perhaps because she knew that she would not find another such creative equal.

After Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson produced Offenbach's La belle Hélène in 1866 at the Christiania Theatre, he had been accused by his opponents of doing precisely what he himself had often criticised: staging light entertainment to cater to the tastes and the wallets of his audience.Footnote 130 The genre compounded the offence. Opera (especially such opéra bouffe) could make no contributions to the cultural life of the nation. Yet it was tremendously popular in Norway, hence Ibsen's hope that an ‘opera public’ might one day be transformed into a true ‘dramatic public’. Oselio's return proved that it was possible for a Norwegian artist to appeal to this ‘opera public’ and attract the broad audiences that enjoyed such productions. At the same time, her success abroad marked her as the equal of other European musicians, actors and writers. Oselio's work in Norway thus effected a dual transition. She established conclusively that opera would continue to appear on the country's most important stages but not simply to complement dramatic works or to augment a theatre's failing finances. Instead, opera could be staged to feature the talents of Norwegian musicians and, in the process, reveal the importance of the genre itself. Opera in Norway no longer need depend on foreign resources, even if the country continued to perform foreign repertoire.

More significantly, Oselio demonstrated that there might be a distinctly Norwegian vision for staging and interpreting opera. That vision would expect the same things from the musical stage that it expected from the dramatic stage. Operas would be sung in the Norwegian language and by Norwegian singers. Performers would be well rehearsed and the productions would be designed with careful attention to their individual features. They would not be modified to accommodate conservative tastes but would seek to interpret the original work with artistic integrity, to be ‘true’ to the characters and to life, as Oselio had insisted. Through these means, opera would offer its own corollary to developments in drama, literature and art. It could become a legitimate national enterprise with legitimate artistic merit.

If Oselio had not come back to Norway, opera would have continued to appear on the country's stages. Yet her enormous popularity forced critics, audiences and artists to reckon with the genre in ways they had not done previously. Gradually, that popularity and the advantages that it provided to Oselio became increasingly grudging. ‘One cannot speak a word about singing’, complained Edle Hartmann in 1911, ‘without having Oselio thrown in your face! … others can be allowed to exist, right? It's not just her, right?’Footnote 131 Of course, it was not just her. Oselio alone could not sustain opera production in Norway, although once she retired from the stage, the genre quickly declined and then largely vanished.Footnote 132 What Norway wanted and needed, as Nordisk musik-tidende had suggested in 1888, was to be regarded as equal to their neighbours in Scandinavia and, ultimately, to the rest of Europe. Oselio had offered them that equality, showing that it was possible for an opera singer to be both fully cosmopolitan and fully Norwegian.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Musical Women in the Long Nineteenth Century conference, convened in February 2020 at the Royal Northern College of Music. I am grateful to participants in that conference for their thoughtful insights and comments on Oselio and her context. I also extend my appreciation to the Furman University Research and Professional Growth committee and the Furman University Libraries for funding components of this project.