Canada's federal political parties are understood to be stratarchical organizations, in which authority is shared between the national and local levels (Carty, Reference Carty2004). National and local party organizations collaborate during federal elections, but they are not coequals, as the central party imposes strict discipline on local actors (Marland, Reference Marland2020). Nonetheless, for each major party, local campaigns are ultimately run by 338 individual candidates and campaign managers. Even when local political conditions are favourable to central party dictums and the national message, local campaigns may have distinct preferences about how to conduct their affairs. This article examines when and why local campaigns engage in undisciplined behaviour. More specifically, I ask, what are the major federal parties’ expectations for campaign discipline and to what extent do local candidates adhere to them? Based on interviews with local candidates and party strategists, as well as observational data collected during the 2019 federal election, I find a relatively high level of undisciplined behaviour, with minor differences based on riding density, competitiveness, province and gender. The article further suggests that undisciplined behaviour stems from three sources within local campaigns: insubordination, innovation and incompetence.

Party discipline is a prominent topic of study in Canadian politics (see, for example, Godbout Reference Godbout2020). Scholars contend that the marked centralization of decision-making authority within federal parties extends to the campaign context (Flanagan, Reference Flanagan2014; Marland et al., Reference Marland, Esselment, Giasson, Marland, Giasson and Esselment2017; Savoie, Reference Savoie2019), yet there is limited firsthand data on campaign discipline. Research also shows that local actors can personalize their campaigns by downplaying party affiliation and focusing on local issues and candidates (see, for example, Cross et al., Reference Cross, Currie-Wood and Pruysers2020). This campaign personalization is not necessarily a question of campaign discipline, particularly if it is condoned by the central party. Nonetheless, it highlights the potential for an array of local campaign responses to party constraints. Given that local campaigns are neither instruments of a central party apparatus nor fully autonomous actors, it bears examining to what extent they engage in behaviours that contravene party preferences. This article offers new evidence to understand local campaign compliance and address the characteristics and sources of undisciplined behaviour.

The article begins by emphasizing the tension faced by constituency campaigns, which are simultaneously pressured to conform to message discipline and party directives, while also considering local imperatives and their own preferences. A gap remains in understanding the ways in which local campaigns actually behave in accordance with party expectations. The article subsequently presents its methods and data sources. It draws primarily from interview and observational data that help to articulate central party preferences and evaluate their execution by constituency campaigns. The article proceeds to establish what undisciplined behaviour is, identify what indicators can be used to detect it and construct a typology of campaigns based on degree of discipline. Local candidates are classified as conscientious, conflicted or maverick in their adherence to party preferences. Following this, the article contends that undisciplined behaviour results from insubordination, innovation and incompetence within local campaigns and offers a theoretical account of each dimension. The article concludes by summarizing the implications for our understanding of Canadian party organizations.

Prospects for Undisciplined Campaign Behaviour

Existing research implies conflicting expectations for local campaign discipline. While some scholars emphasize the centralized nature of campaigns (Marland, Reference Marland2020: 38), others note the potential for local diversity and divergence from the central party (Kam, Reference Kam2009: 154; Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Lawlor, Cross and Blais2019: 71). To be sure, the central party is known to intervene in candidate nominations (Pruysers and Cross, Reference Pruysers and Cross2016), dictate preferred campaign activities (Munroe and Munroe, Reference Munroe and Munroe2018), manipulate local finances (Coletto et al., Reference Coletto, Jansen and Young2011) and implore constituency campaigns to repeat national talking points (Marland, Reference Marland2016: 10). Campaign centralization is linked to centrally managed electronic data collection (Bennett, Reference Bennett2019; Patten, Reference Patten, Marland, Giasson and Esselment2017) and accelerated pressures toward message discipline, as communications errors are seized upon by the media and rival parties (Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Lawlor, Cross and Blais2019: 171). Through candidate recruitment, training and the campaign itself, local actors are made aware of these disciplinary imperatives (Marland and Wagner, Reference Marland and Wagner2020). Parties anticipate local deference and display heightened vigilance toward deviation from their expectations.

There is evidence that these trends have affected Canada's three largest parties: the Conservative Party (Farney and Koop, Reference Farney, Koop, Lewis and Everitt2017; Flanagan, Reference Flanagan, Farney and Rayside2013: 90), the Liberal Party (Carty, Reference Carty2015; Jeffrey, Reference Jeffrey, Gagnon and Tanguay2017) and the New Democratic Party (NDP) (McLean, Reference McLean2012; McGrane, Reference McGrane2019).Footnote 1 Under such conditions, constituency campaigns may be viewed as high-risk, low-rewardFootnote 2 sources of potential distraction rather than complementary or component parts of federal parties. As Flanagan (Reference Flanagan2014: 107) summarizes, “Canadian campaigns remain highly disciplined and controlled from the centre.” Given this reality, “local candidates mostly repeat talking points furnished by the national campaign” (31). These trends are important because they indicate the limited prospects for undisciplined local campaigns. Nonetheless, despite the centralization of party authority, we should not assume that local campaigns will uncritically follow central party guidance.

Indeed, related scholarship notes the potential for local campaigns to behave independently. Carty's (Reference Carty2002) franchise model contends that local actors hold autonomy over the ground campaign in their districts, in exchange for discipline on matters of national strategy and policy. Although central party forces have encroached on aspects of this stratarchical bargain (Carty, Reference Carty2015; Pruysers and Cross, Reference Pruysers and Cross2016), local organizational input and decision making have endured. Cross (Reference Cross2018: 205) contends that multitiered parties are characterized by mutual interdependence, since national and local actors share authority in the spheres of candidate selection, party leadership selection and policy development. In addition, single-member-plurality electoral rules steer candidate attention toward local political conditions (Fox, Reference Fox2018). Accordingly, Canada's electoral system may militate against party discipline as constituency campaigns reconcile local realities with party demands. Additionally, regional divisions are highly salient influences on vote choice, more so than other social cleavages (Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Lawlor, Cross and Blais2019). This raises the potential for tensions between constituency campaigns and the central party, since party policies are likely to vary in popularity by region.

Centrifugal campaign pressures are evidenced in the phenomenon of decentralized campaign personalism (Balmas et al. Reference Balmas, Rahat, Sheafer and Shenhav2014), which highlights candidates’ abilities to emphasize their personal characteristics in place of their parties.Footnote 3 These candidates rely on personal reputations and locally tailored messages, and they even distance themselves from the central campaign and party leader. Scholars have examined the prevalence of decentralized personalism for elections in Israel (Balmas et al. Reference Balmas, Rahat, Sheafer and Shenhav2014), in Romania (Chiru, Reference Chiru, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2018) and in the European Parliament (Bøggild and Pedersen, Reference Bøggild and Pedersen2018). Unlike these cases, Canada employs a single-member-plurality electoral system, with substantial incentive for candidates to personalize their campaigns (Zittel, Reference Zittel2015). Indeed, Cross and Young (Reference Cross and Young2015) find a high overall level of decentralized personalism among candidates in the 2008 Canadian election. In this respect, the decentralized reality of Canadian elections is clearly evidenced in the behaviour of local actors.

Crucially, decentralized campaign personalism is conceptually distinct from undisciplined behaviour because the former is reconcilable with party imperatives and is even encouraged by central party actors. Existing research has often drawn from Zittel and Gschwend's (Reference Zittel and Gschwend2008: 989) conception of personalization in terms of campaign means, agendas and organization. Cross and Young (Reference Cross and Young2015) classify personalism as locally produced campaign messages (means of communication), distinct campaign issues (agendas) and campaign volunteers drawn from the personal networks of the candidate and core campaign staff (organization). Pruysers and Cross (Reference Cross2018: 73) operationalize decentralized personalism as covering issues not raised by the central campaign and creating personalized radio or television advertisements. Similarly, Cross et al. (2020: 5) rely on survey responses where former candidates are asked to assess the extent to which they emphasized their party affiliations versus themselves as candidates and the extent to which their campaign communications were produced independently from their parties.

Understood in this manner, as focusing on local concerns and candidate attributes, as well as producing campaign content using local resources, decentralized personalism can be largely compatible with central party imperatives. It is a potential asset if the party can downplay an unpopular leader, policy position, or party brand while benefiting from locally conscious strategy and perceived strengths of the local candidate. As Cross and Young (Reference Cross and Young2015: 308) explain, “We do not find ‘disloyal’ local candidates in the Canadian context; rather, personalization is expressed through subtle emphases on local issues, an implicit downplaying of the national platform and organizational reliance on the resources and skills of the individual candidate.” For its part, undisciplined behaviour differs from personalization because it consists of prohibited behaviours that have been identified by party strategists. Prior analyses do not generally consider whether constituency campaigns disobey or experience conflict with the central party. Beyond campaign personalization, there is a gap in our understanding of whether local actors contravene party preferences. As such, a closer examination of the behavioural and disciplinary tendencies of constituency campaigns is warranted.

Data and Methods

The first major data source consists of in-person interviews conducted with 87 federal politicians and eight party strategists. The target population for this study was comprised of former federal candidates in Alberta, Ontario and Quebec, for the three largest federal parties, who stood for election in 2015. It also includes party strategists employed in senior positions during the 2015 and/or 2019 campaign periods. All participants were recruited by email, with a 32 per cent response rate for candidates and 22 per cent rate for party strategists. For the eight party strategist interviews, contact information was obtained through publicly listed details or personal referrals. Recruitment emails were sent to every senior strategist for whom contact information was readily available.

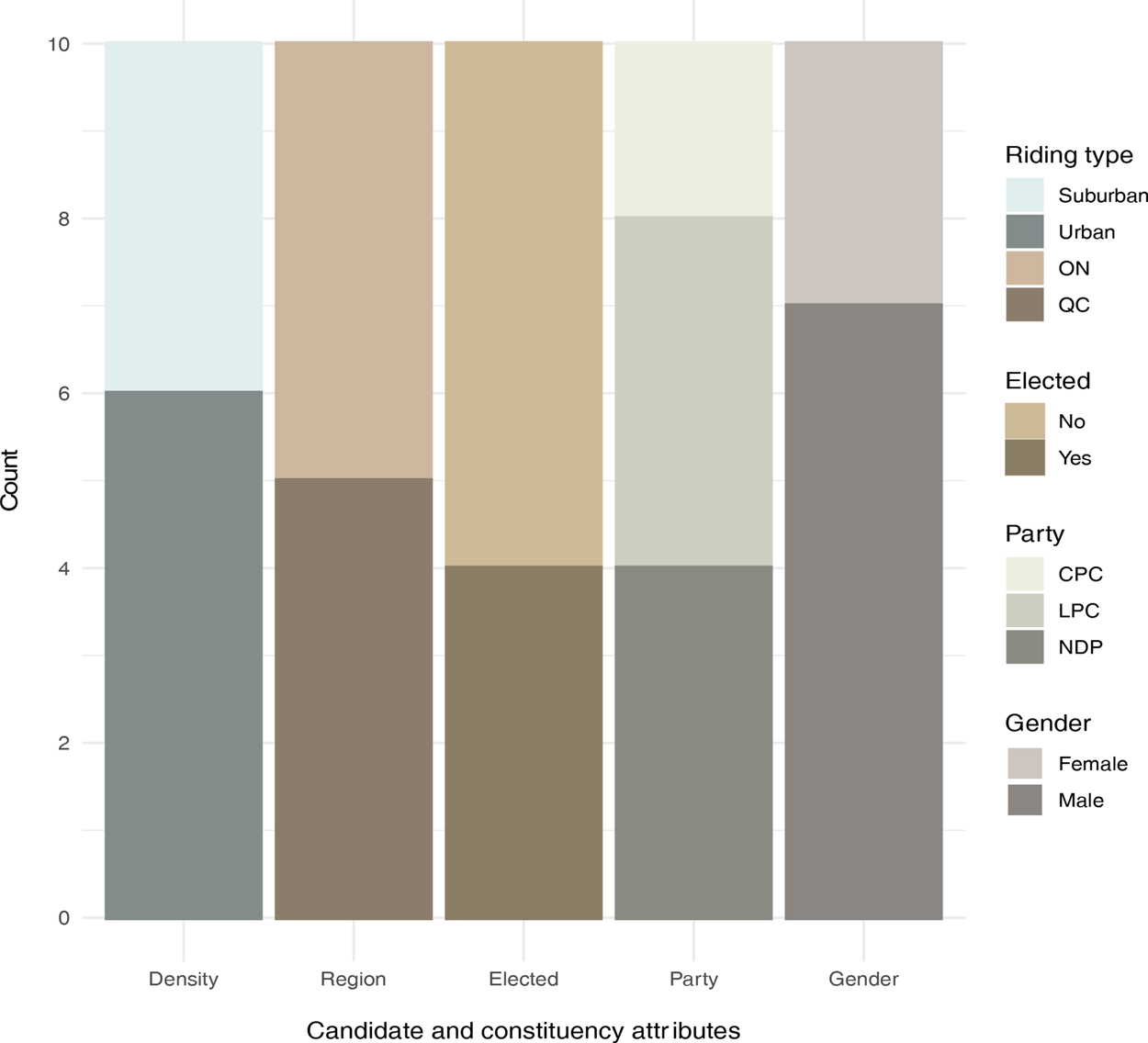

For candidates, the sampling procedure began with a randomly generated list of candidates in the aforementioned three provinces but also featured purposive selection based on relevant political criteria and practical considerations. The sample population was continually rebalanced to include sufficient variation based on party affiliation, gender, candidate viability, province, riding density and riding competitiveness.Footnote 4 Sample characteristics are displayed in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Sample Attributes: Candidate

Figure 2. Sample Attributes: Constituency

A further limitation is that the sample does not examine other provinces, elections or smaller parties. For these reasons, the sample cannot be representative of all candidates. This approach sacrifices a measure of external validity or generalizability in favour of internal validity and greater depth. Relative to other data collection methods such as online surveys, the in-person approach permits greater nuance and exploration of unforeseen lines of inquiry. In-person interviews can also instil a high degree of confidence in the expressed meanings of respondents and facilitate access to controversial political information that respondents may otherwise be reluctant to disclose (Pridemore et al., Reference Pridemore, Damphousse and Moore2005). Relative to telephone interviews, they permit greater nuance in tone and body language and nonverbal cues, and they facilitate a stronger rapport with the interviewee, which is particularly important when discussing sensitive topics such as campaign discipline. In-person meetings also allowed subjects to provide tangible examples of campaign documents, which enhanced these discussions and provided access to valuable primary source materials and additional local context.

Semi-structured interviews with candidates and party strategists contained 12 questions broadly concerned with local-national party relations. Additionally, interviews featured shorter, closed-ended questions, including those intended to provide indicators of undisciplined campaign behaviour. This approach was generally designed to avoid leading questions and invite flexibility in interview content. Interview subjects were offered confidentiality in order to mitigate professional or social risks associated with the disclosure of politically sensitive information. Most participants chose to be identified only by their party and province.

The second major data source is derived from participant observation of local campaigns during the 2019 federal election. Participant observation allows researchers to make inferences about the activities of people and groups under study by participating in these activities and observing them in their natural setting (Kawulich, Reference Kawulich2005). Three major studies (Munroe and Munroe, Reference Munroe and Munroe2018; Koop, Reference Koop2011; Sayers, Reference Sayers1999) have employed participant observation in the context of Canadian constituency campaigns. These studies are enthusiastic about the ability of participant observation to generate rich original data.Footnote 5 Citing Fenno (Reference Fenno1990), Blidook and Koop contend (2019: 2) that watching and closely following politicians in their natural setting is the best way to learn about them. Since data are collected in real time and in a real-world setting, we can be relatively confident that they actually reflect research subjects’ behaviours and attitudes (Musante, Reference Musante, Russell Bernard and Gravlee2015). Compared to surveys or interviews, there is reduced risk of distortions through subjects’ post hoc rationalizations, memory lapses or social desirability biases. This view is echoed by others (Kawulich, Reference Kawulich2005; Uldum and McCurdy, Reference Uldam and McCurdy2013) who highlight the need to study how research subjects make sense of their environments and ascribe meaning to their actions.

Participant observation also carries important limitations. Local campaigns willing to host an outside observer may be systematically different from other campaigns. In this case, the reasons given for participating in the research were idiosyncratic and unrelated to the purpose or topic of study. Despite this potential trade-off where a measure of representativeness is sacrificed for greater analytical depth (Munroe and Munroe, Reference Munroe and Munroe2018: 140; Sayers, Reference Sayers1999: 14), this method provides a compelling window into local campaign behaviour.

The target population for campaign observation was significantly constrained by logistical realities, namely the time required to visit multiple campaigns during a relatively short election period. Based on a list of 94 feasible Quebec and Ontario ridings, I randomly selected local campaigns from the three largest federal parties and sent requests to their publicly listed email addresses. Out of 100 emails sent, 21 local campaigns agreed in principle to participate and 10 of these were ultimately chosen based on purposive criteria, to achieve a balance of party affiliation, riding density and campaign competitiveness.Footnote 6 The sample characteristics are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Participant Observation Sample

Observation of these 10 local campaigns began when writs of election were issued on September 11, 2019, and continued until the election on October 21. During this 41-day period, 30 full days were spent observing constituency campaigns, with some days split between two nearby campaigns. Most observation took place in campaign offices but also included excursions for voter canvassing, meetings with community groups, fundraisers and various local events. Detailed notes were gathered throughout the day and organized thematically at the end of each day. In order to provide greater context, semi-structured interviews were also conducted whenever feasible.Footnote 7

Identifying Undisciplined Constituency Campaign Behaviour

Before considering the substance of undisciplined behaviour, it is important to understand why constituency campaigns might engage in it. Table 1 sheds light on this question by addressing constituency campaigns’ perceived alignment of their interests with central party interests. According to these findings, only 28 per cent of constituency campaigns in the sample feel that their interests are always aligned with their party's interests. Thirty-eight per cent of constituency campaigns report that their interests are aligned with the central party either some of the time or none of the time.

Table 1. Perceived Alignment of Local and National Campaign Interests

Note: N = 87

* Percentages do not add to 100 due to rounding

A 2015 NDP candidate in Quebec mentions why they struggle to perceive an alignment of interests: “I think we look after ourselves. . . . That's what the party is doing [for themselves] . . . and [they] would probably throw us under the bus if it got [the leader] a two-point bump [in the polls]” (interview with NDP candidate).Footnote 8 In this view, the consequentialist logic of the national campaign may lead them to sacrifice certain constituencies for the overall good of the party. In a more extreme illustration, a 2019 local campaign manager in Quebec expressed a desire for the manager's own party to lose the 2019 election and for the leader to be replaced.Footnote 9

Others argue that the central party's focus on the median constituency clashes with local realities. As 2015 NDP candidate Daniel Beals (Kingston and the Islands) declares, “My belief is Kingston is a different kind of riding than anywhere else in the country. So why not do what we think will work best in Kingston? . . . We know Kingston, [the party doesn't].” A 2019 Liberal campaign manager argues similarly that “we are not the median riding. . . . These [generic party instructions] aren't going to help. . . . We need to do some critical thinking about . . . which instructions actually make sense.” Consistent with these sentiments, many constituency campaigns in this sample express that their fortunes are intertwined with the national party but not interchangeable. Indeed, national campaign themes and messaging intended to generate broad popular appeal do not necessarily translate effectively to the constituency level. Liberal MP Rob Oliphant (Don Valley West) notes that the Liberal Party's 2015 messages appealing to “the middle class and those working hard to join it” were inappropriate for his riding, because “I just didn't have enough middle class. I had wealthy and I had poor.”

For its part, the central party oversees all constituency campaigns, in addition to their national advertising strategy, media management and leader's tour. An NDP strategist describes these tasks as “juggling flaming swords on a tightrope.” These challenges are not always respected by constituency campaigns, who according to 2019 Conservative national campaign director Hamish Marshall, often possess an exaggerated view of their own uniqueness. NDP strategist Karl Bélanger agrees with this viewpoint: “[Constituency campaigns] all say their riding is unique and they're all wrong.” As Bélanger recounts, local activity can be a source of stress for the central party: “The party is fixated on avoiding blunders, which are often caused by actors within the party who stray from the game plan. When you're off track defending yourself against something, instead of what was planned to talk about, you're wasting tens of thousands of dollars a day or more.”

The perceived misalignment of national and local interests is an important finding in foretelling the importance of undisciplined campaign behaviour. If most constituency campaigns felt that their interests were interchangeable with their parties’ interests, it may not even occur to them to disturb party cohesion or act in defiance of the central party. Since this is not the case, these results anticipate the existence of undisciplined constituency campaign behaviour, as well as parties’ preoccupations with maintaining discipline.

Indicators of undisciplined campaign behaviour

In order to uncover party expectations for constituency campaign activity and use these to create indicators of undisciplined behaviour, I draw from three major sources. First, there is limited scholarship (Richler, Reference Richler2016; Small and Philpott, Reference Small, Philpott, Marland and Giasson2020; Thompson, Reference Thompson, Pammett and Dornan2016) from the perspective of local candidates that illustrates key campaign responsibilities and expectations. For example, Noah Richler's firsthand account of his experience as an NDP candidate in 2015 highlights clashes with the central party over social media content and includes when and why certain actions were deemed to be prohibited by the centre (2016: 237–44). The second source consists of local campaign manuals or written instructions from the central party. Confidentiality prohibits sharing direct quotations from these sources; however, guidelines for all three parties feature common directives for acceptable and unacceptableFootnote 10 constituency campaign behaviours. Many of these items are significant enough to be mentioned for all three major federal parties.

Last, in order to better understand these party expectations, I interviewed eight party strategists—two Conservatives, three Liberals and three New Democrats—who held central campaign positions during the 2015 and/or 2019 elections. Each strategist declined to publicly share written versions of their internal party guidelines but referred directly or indirectly to these texts. They also noted that some expectations are outlined explicitly in candidate contracts and campaign manuals while others are presented more informally during candidate training or in campaign communications regularly sent from the central party to constituency campaigns. These guidelines are important in establishing the parameters of undisciplined constituency campaign behaviour. To this end, party strategists were asked the following questions: “Is there anything that local campaigns can do that would cause concern for the central party? Based on past experience, what activities or behaviour do you want local campaigns to avoid?” Party strategists offered a variety of responses; these closed-ended responses are supplemented with strategists’ responses to open-ended interview questions, which help to illustrate their views on undisciplined campaign behaviour. Based on these interviews, as well as secondary analysis and campaign manuals, I develop six indicators that are used to identify undisciplined behaviour. They are intended to be general enough to cover a range of constituency activities.

Table 2 displays the percentage of local campaigns that identified their participation in each aspect or indicator of undisciplined behaviour. At the lower end, 5 per cent of campaigns (4 candidates) publicly criticized their leader or party and 8 per cent (7 candidates) co-operated with an opposing campaign. The most frequent form of undisciplined behaviour is ignoring a directive from party headquarters (42 per cent).

Table 2. UCCB Indicators

Note: N= 87

Typology of undisciplined constituency campaign behaviour (UCCB)

What conclusions can be drawn from these data? It is clear that local candidates and their campaigns vary in the propensity to engage in undisciplined behaviour: some abstain entirely, others indulge intermittently, and certain candidates are persistently undisciplined. Moreover, the indicators of undisciplined behaviour vary in their severity: publicly criticizing a party leader is more severe than privately criticizing the leader. Based on these findings, I classify local candidates and their campaigns as conscientious, conflicted or maverick, based on frequency and type of undisciplined behaviour. These labels are preferred to the more straightforward terms disciplined and undisciplined because of the connotation of carelessness or laziness that the latter entails. The term maverick helps to convey a conscious defiance of central party preferences.

As shown in Table 3, local campaigns that display zero indicators are classified as conscientious. Campaigns are labelled as conflicted that exhibit one or more of the following four indicators: ignore party instructions, distribute unvetted materials, privately critique party leadership, or contradict a party position. Last, candidates that co-operate with an opposing party and/or publicly criticize party leadership are assigned the maverick campaign label. In this manner, we see that 45 per cent of candidates in this sample can be classified as conflicted, 42 per cent as conscientious and 13 per cent as maverick.

Table 3. Constituency Campaign Typology by Degree of Discipline

Note: N = 87

These broad categories mask fundamental differences in local campaign attitudes toward their roles within the party organization and toward the central campaign. Conscientious candidates, and by extension, their constituency campaigns, broadly suggest that undisciplined behaviour is unacceptable and party discipline must always be maintained. They represent 42 per cent of respondents. In cases of uncertainty, these candidates feel they must do what the party would prefer. As a conscientious Conservative candidate (2015, Quebec) explains, “There is no room for conflict with your own party. You sign the candidate agreement . . . so you know exactly what you're getting into. . . . [The party has] enough to worry about.” Similarly, when asked if they ever openly disagreed with their party, a Liberal candidate (2015, Ontario) adds, “Absolutely not. Never speak up like that during a campaign. What is that accomplishing? If you are a real team player, you can nod and go along until the campaign is over and then you might have some other channel.”

Conscientious candidates tend to view their campaigns as an extension of the central party, rather than distinct entities. As an NDP candidate (2019, Quebec) explains, “When you think about it, we're actually one and the same.” A Liberal Party campaign manager (2019, Ontario) agrees with this view: “I don't usually think of ‘the party’ [as separate]. . . . We're the party as much as they're the party.” These candidates are also preoccupied with unintended consequences of their actions and potential repercussions for other candidates. Former NDP MP Matthew Dubé (Beloeil–Chambly) emphasizes that “solidarity is really important. You're part of a team. . . . You don't want to damage someone else's chances . . . particularly in the era of social media where an off-the-cuff comment can easily find its way out.”

Conversely, conflicted candidates are more tolerant of undisciplined behaviour and exhibit a moderate commitment to party cohesion. These candidates indicate they have ignored party instructions, contradicted a party position, distributed unvetted campaign materials, and/or privately criticized their party leadership. Conflicted candidates represent 45 per cent of respondents. Despite openness to undisciplined behaviour, conflicted candidates are reluctant to distract from the national campaign or to face repercussions from central party officials. In other words, they articulate conflicting sentiments regarding their party obligations. As NDP candidate Marlene Rivier (2015, Ottawa West–Nepean) explains, “I have strong philosophical beliefs . . . but I was always a New Democrat. . . . I saw our shared success requiring a level of continuity between us.” Former Conservative MP Brad Butt (Mississauga–Streetsville) is similarly conflicted on the acceptability of undisciplined behaviour. Butt feels that deviation from the central party is acceptable if it concerns issues of substantial importance to the candidate. He further underlines that any divergence must be done tactfully and without attracting unwanted media attention: “It's up to you to communicate it properly. If you're a lousy communicator then God help you.”

Unlike conscientious candidates, conflicted candidates do not necessarily perceive an obligation to seek party guidance in the face of uncertainty. A 2015 Liberal candidate in Quebec explains that they sought to use their “best judgment. . . . If you're a candidate and you've gone through that process, I'd like to think you can make the right decision on your own, at least 99 per cent of the time.” Nor do conflicted candidates view their campaigns as extensions of the central party. As a 2015 Alberta Liberal candidate explains, “I sometimes did what I wanted even if it wasn't what the party wanted because I felt like: (a) They didn't know what I was doing and were far away, and; (b) They didn't really care anyways.”

Last, there are two indicators for maverick candidates: co-operation with an opposing campaign and publicly criticizing party leadership. Either indicator is sufficient to receive this maverick label. Every maverick candidate also indicated that they had engaged in more than one other less severe form of undisciplined behaviour, such as ignoring party instructions. Maverick candidates represent roughly 13 per cent of respondents, or 11 people in a sample of 87.

When discussing their feelings toward the central party, maverick candidates claim that their stated devotion to the constituency or their personal convictions can take precedence over party obligations. They offer concrete examples of a locally sensitive mindset. For example, NDP candidate Daniel Beals (2015, Kingston and the Islands) explains how he opposed his party's official positions on energy and climate change: “I decided I was going to make it very clear that I believe that the oil sands in Alberta should, in fact, be called the tar sands and we should leave the oil in the ground. That was not a talking point that the party wanted anyone to use. . . . It wasn't done expecting nothing to happen. I thought that I'd hear about it later. . . . I did it on purpose.” Beals further explains how this approach stemmed from an allegiance to local party members: “NDP members in Kingston chose me. . . . They're the ones that I owed my first allegiance to. . . . And I might not have been elected by the riding, but I was elected by those people to be their voice.” In another case, a maverick candidate in Ontario recalls critiquing one of their party's policy commitments and related communications. The candidate indicated their refusal to repeat these messages, recounted heated discussions with the central party, and claimed they ultimately faced no discernible party repercussions.

Variation in campaign discipline by candidate and riding-level attributes

This section offers additional data on undisciplined behaviour and politically relevant variables such as party affiliation and riding density. These data serve an illustrative purpose more so than an analytical one. Caution and nuance are required in drawing conclusions regarding these variables, due to small sample sizes, for example, of rural candidates. This diminishes our ability to illustrate general tendencies across the sample population. Moreover, this sample of 87 candidates cannot be truly representative of all candidates, since it was not obtained purely through randomized probability sampling.Footnote 11

Previously, studies of personalized campaigning (for example, Pruysers and Cross, Reference Pruysers, Cross, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2018) have benefited from several hundred survey responses in order to determine which factors lead to more personalized campaigns. In this case, the ambition is to maximize internal validity while obtaining a considerable amount of sensitive political information, an approach consistent with other studies of local campaign behaviour (Sayers, Reference Sayers1999; Koop, Reference Koop2011; Munroe and Munroe, Reference Munroe and Munroe2018) that have achieved greater depth at the expense of breadth. Despite limited generalizability, the findings outlined below help to reveal how local campaign behaviour may differ based on key candidate and riding characteristics. Notably, there is minimal apparent variation in disciplinary tendencies across the variables of interest.

Sample characteristics for 87 interviewees are displayed in Figure 1 and Figure 2, which feature breakdowns by candidate and riding attributes relevant to the propensity for undisciplined behaviour. First, political parties may have different disciplinary norms, and the NDP in particular has fewer resources that can be dedicated to campaign cohesion. Second, existing research shows us that female candidates are treated differently than male candidates by parties and the media (see, for example, Goodyear-Grant, Reference Goodyear-Grant2013), and this may be reflected in candidates’ behaviours. Figure 1 also illustrates how many candidates in the sample were successful in their elections. Elected candidates may be more prone to undisciplined behaviour due to their campaign viability and likelihood of possessing substantial campaign resources.

Figure 2 displays riding-level characteristics relevant to the analysis. Candidates are differentiated by province, as regional differences may generate different attitudes toward campaign discipline and party cohesion. In addition, research on campaign personalism (Cross and Young, Reference Cross and Young2015; Pruysers and Cross, Reference Pruysers, Cross, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2018) shows that rural candidates are more likely to personalize their campaigns. It is possible that the greater stature enjoyed by candidates in non-urban areas is equally relevant in the case of campaign discipline, so I also consider whether the riding is located in a primarily rural, suburban or urban environment. Last, the central party may be more tolerant of undisciplined behaviour in constituencies where they are unlikely to win. Parties also pay greater attention to target seats where they face tight competition. Therefore, I consider the competitiveness of the local race, using a simplified distinction between battleground and stronghold ridings (Bodet, Reference Bodet2013) based on margin of victory, as per Blais and Lago (Reference Blais and Lago2009: 95). In battleground ridings, the candidate of interest won or lost their race by 10 percentage points or less. In strongholds, the candidate of interest won or lost by more than 10 percentage points.

Table 4 displays the results for undisciplined behaviour based on candidate and riding-level attributes. For greater readability, findings are reported as proportions that total to 1, as seen in the far right-hand column. Despite the expected relevance of these attributes, we see limited variation in this sample, once again limited by the small size. Recalling Table 3, 13 per cent of candidates in the sample are mavericks, who display the most strident undisciplined behaviour. Table 4 shows that only 7 per cent of Liberals in the sample are maverick candidates, compared with 16 per cent of NDP candidates. However, the sample size is such that if just one additional Liberal candidate qualified as maverick, the percentage would increase to 11 per cent. Therefore, apparent variation in proportion or percentage terms must be viewed alongside the modest variation in raw counts.

Table 4. Constituency Campaign Discipline by Candidate and Riding Characteristics: Proportions (raw counts)

Note: N = 87; due to the low number of observations, assumptions required for chi-square tests are not met and tests cannot be performed. Fisher's exact test found no significant associations.

Female candidates are the most disproportionately conscientious in this sample, with 55 per cent, compared to a sample average of 42 per cent. Female candidates are also slightly less likely than male candidates to display maverick behaviour (9 per cent versus 14 per cent). There is no apparent difference in discipline based on whether candidates were successfully elected. Aside from a disproportionate concentration of conflicted candidates in Ontario, there is minimal variation by province. Somewhat surprisingly, Ontario candidates did not express a more harmonious relationship with the central party than those in Quebec or Alberta. A 2015 Liberal candidate in Southwestern Ontario recalls “I sometimes felt hung out to dry because it was all about the GTA [Greater Toronto Area].” However, an NDP candidate in the GTA suggests that “the party was completely tone deaf to Toronto, they were convinced that they [needed] Quebec and Southwestern Ontario. . . . [But] I ran as a champion of Toronto.” Former Conservative MP Brad Butt also suggests that his party's 2015 campaign messaging neglected the GTA and that this affected his re-election chances.

The clearest disproportionate concentration of maverick candidates is found among rural candidates and those in stronghold ridings, with proportions of 0.19 and 0.17, compared to the all-candidate average of 0.13. This is consistent with findings that rural candidates are better known in their ridings than non-rural candidates (Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2005) and are more likely to personalize their campaigns (Cross and Young, Reference Cross and Young2015). It also suggests that central party attention, which is focused on battleground ridings (Flanagan, Reference Flanagan2014), may serve as a check on undisciplined behaviour. Still, these differences are fairly modest when considering the overall number of rural and battleground candidates. Altogether, while we do not have sufficient data to draw definitive conclusions, candidates in this sample from different parties, provinces and electoral circumstances share similar tendencies toward undisciplined behaviour.

Three Avenues to Undisciplined Constituency Campaign Behaviour

Given the lack of variation found in this sample based on candidate and riding characteristics, are there other explanations or common features of undisciplined behaviour? In the following section, I identify three broad features of undisciplined behaviour that shed light on why candidates sometimes refuse or fail to follow party directives. In reviewing interview transcripts and data derived from observational research, individual instances of undisciplined behaviour appear to be driven by insubordination, innovation and incompetence within local campaigns. These concepts are not mutually exclusive, as certain instances of innovation also constitute insubordination.

Insubordination

Insubordinate campaign behaviour is defiant toward the central party. This behaviour entails knowledge of central party expectations and a decision to discount them. It is visible within several key domains of constituency campaign activity such as voter canvassing. Importantly, the central party is often unaware of insubordinate behaviour. For example, a 2019 candidate in Ontario recounts how their campaign was instructed not to accept volunteers affiliated with a particular advocacy organization. However, they proceeded to accept several volunteers without the party's knowledge. Maverick and conflicted candidates with local-centric views are undoubtedly more prone to insubordination. Some express frustration with supposedly out-of-touch directions imposed by the central party. Conservative candidate Andy Brooke (Kingston and the Islands) recalls that “I was told early in the [2015] campaign to not even address or speak on local issues.” In the end, Brooke “only tried [this approach] for about a week.” Liberal MP John McKay (Scarborough–Guildwood) suggests that parties should grant candidates much greater leeway to address local issues, although he personally felt free to do so. In terms of contradicting the party message, McKay contends, “You do try to minimize your inconsistencies, but the Lord himself was not entirely consistent on all matters. . . . We're all inconsistent. Parties, frankly, more so.”

Why would parties discourage a localized campaign focus? A Conservative strategist suggests that “once you're deep into [local issues] there's a heightened risk of making a mistake . . . something with an implication you haven't considered.” Similarly, NDP strategist Karl Bélanger notes that “the messages chosen by the party were tested and selected in order to maximize the ability to gain votes. . . . Once you depart from them, you're in uncharted territory and you're going on local instinct. . . . I'm concerned about [these instincts] if we were to loosen this.” Bélanger perceives a necessity for candidates to repeat party messages, rather than their own, because parties work hard to achieve brand penetration, which is undermined by conflicting local messages. He equally downplays the need to address local issues, since “it's a federal election, not a local referendum.” Nonetheless, these contentions sit poorly with some local candidates.

Innovation

Conversely, some candidates and campaign managers contravene party directives through their innovative campaign practices, which demonstrate local resourcefulness and ambition. As a 2019 NDP campaign manager suggests, “Some of [our activity] . . . is more creative [and] falls outside the bounds of what's typically expected.” Innovative behaviour may or may not overlap with insubordinate behaviour. For example, Liberal MP Adam Vaughan demonstrated insubordinate innovation in adopting novel canvassing techniques in 2015: “If you went knocking on doors, you wouldn't find anybody home, if you went to the park, you'd find two thousand voters there . . . [and] everyone drinks illegally in the park . . . [so] we took small brown paper bags, we got a small rubber stamp that said ‘hide your beer, don't hide your vote,’ and gave them [information] for where the advance polls were.” Vaughan's campaign also disregarded party instructions not to attempt this tactic. The candidate recalls, “When we first proposed to do this, the party went nuts. . . . This looked like we were encouraging law breaking and public disorderly conduct. . . . If this gets back to the churches in the suburbs that we're doing this and we'll be just as lax with illegal drugs. . . . But we did it anyways because we knew it was going to stay in the park. . . . And it was very successful, and it didn't blow up beyond the park.” In Vaughan's view, this experience reinforced the idea that the central party is not always in touch with local realities. He explains that “the central party, if you ask them, they'll shut it down because they want a regimented military message-of-the-day campaign but locally that's not breaking through, and you've got to find ways to communicate to people where they live and how they live.”

Conversely, local campaign innovation may accidentally disregard party procedures. For example, a 2015 candidate recalls how their creative campaign videos unintentionally attracted media attention that was strongly frowned upon by the central party. Along these lines, constituency campaign resources are a strong predictor of innovation, as they facilitate experimentation with atypically bold, sophisticated or novel tactics. Nonetheless, innovation can also occur among resource-poor constituency campaigns, when scarcity promotes improvisation that results in deviation from party expectations.

While local actors are hardly forbidden from pursuing innovative campaign practices, these must be cleared with field organizers and other party officials. When pressed for why they did not seek official party approval, constituency actors typically pointed to impracticality, delays and the possibility of having the request refused. As a 2019 Conservative campaign manager explains, “I'm moving ahead with this because I'm very confident that what they don't know won't hurt them.” They added a familiar idea that was heard from several local campaign actors in different parties: “Beg for forgiveness, not permission.” A 2015 NDP candidate in Ontario echoes this sentiment: “I think there's a randomness to getting the green light [for this campaign practice]. . . . If I show it to [a certain person], they'll be fine with it, someone else might be quite skeptical. . . . I'm not in a place to navigate that right now so better to just go ahead and tinker later if [someone objects].”

A frequent medium for constituency campaign innovation in 2015 and 2019 was the creation of digital advertisements and online promotional videos. These channels allow microtargeting based on postal code, cultural-linguistic group, or other categories (Bennett, Reference Bennett2019). In 2019, the Liberals and Conservatives provided centrally regulated digital advertising packages, through party-aligned suppliers, which local campaigns could purchase. However, some campaigns opted out of this service in order to exercise greater creative control. In contrast to the central party's digital advertisements, they often speak to local or niche political issues. Some include non-official language messaging. Most constituency campaigns in this sample that created their own advertisements suggested that the central party was not privy to this process, and some did not seek party approval for these products.

In certain cases, digital advertisements reinforce the central party's core messages. In other cases, wherein specific content cannot be identified for confidentiality purposes, they varied significantly from national party messages. For example, some Conservative candidates in Quebec announced support for the Quebec government's proposed secularism law, which contradicted official party policy (Vastel, Reference Vastel2019). The policy positions implied in such advertisements risk contradicting official party policy and drawing embarrassment to the party if such tensions are reported in the media. That said, it is equally possible that the central party is aware of dissonant local messages and exhibits a degree of wilful blindness toward them.

Incompetence

A final source of undisciplined behaviour stems from incompetence within local campaigns. This classification signifies not only poor judgment and human error but also an inability to follow party directives due to insufficient capacity in terms of resources, training and other restrictions. Unlike insubordination and innovation, which entail more purposive departures from party directives, incompetence is always non-instrumental. Nonetheless, the result is the same: central party preferences are obstructed or distorted in their application by constituency campaigns.

Several constituency campaigns reported they were unable to handle the demands placed on them by their parties. A 2015 NDP candidate in Alberta explains their gradual exhaustion, since, “at the start [a volunteer] and I were driving 300 plus kilometres a day to keep up. . . . [But] we've pretty much stopped now.” In the case of another 2015 candidate in Alberta, the accumulation of unmet campaign obligations was a highly stressful experience. The candidate explains, “I knew what they wanted and why we couldn't [achieve this]. . . . I didn't like the constant reminders. I felt that I'd tried. . . . At one point . . . [I] stopped returning calls.”

Local incompetence frequently entails errors in judgment or accidental omissions. In other words, candidates and campaign managers may simply make mistakes that contravene party preferences. A 2015 Liberal candidate in Ontario explains the challenges they experienced: “There were problems left and right. . . . We didn't commit our data, we sent the wrong data, we had one person who had done [party training] but he wasn't available . . . and there were all sorts of mistakes. . . . [Sometimes] you can fix it afterwards but . . . I don't think we had time.” Similarly, a 2015 Conservative candidate in Quebec concedes that “a few times I realized afterwards that I had [contradicted a party position]. . . . It was because I wasn't aware of the [party position] in the first place.” In 2019, one candidate realized they were not technically nominated after dozens of signatures from people outside the constituency were uncovered on their nomination form, as the result of a miscommunication. Such cases illustrate the difficulty of implementing central party directives with volunteer personnel who are often overworked and underappreciated. Given substantial inequalities in local financial capacity, vertical or horizontal transfers to under-resourced constituencies (Currie-Wood, Reference Currie-Wood2020) could help to mitigate this type of undisciplined behaviour and its attendant challenges.

Discussion and Conclusion

During an interview, a 2019 Liberal campaign manager jokingly asked, “If a local campaign ignores the [central party], but they don't find out, did it even happen?” This question indicates the importance of considering potential implications of undisciplined campaign behaviour. These include challenges for campaign operations, organizational cohesion and our broader understanding of intraparty relations. First, undisciplined behaviour may cause disruptions or inconveniences to the central campaign, even if party officials are unaware of their source. This is especially clear when campaign planning requires local participation or collaboration. Indeed, through the course of the campaign, the central party deploys the leader, campaign surrogates and other resources to target regions and ridings. Yet several constituency campaigns viewed these exercises as poorly executed or unwelcome burdens. As a result, they effectively undermined central party efforts.

In one case, the central party had planned an announcement targeting members of a particular ethnocultural community. The party requested that a constituency campaign send members of this community to attend the announcement event. However, members of the local campaign refused this request by exaggerating the hardship they would endure and misrepresenting their ability to meet it. Similarly, a 2019 campaign manager that was asked to provide advance team services for a leaders’ visit recounts that “they asked me to drive the route that the [leaders’ entourage] was going to take . . . except I couldn't [do this] . . . and they wouldn't listen. . . . I didn't do it and they never knew.” Others including Liberal MP John McKay (Scarborough-Guildwood) explain that leaders’ tour visits command an extraordinary amount of their resources and distract them from local objectives, with minimal political benefit. They seek to release a minimal amount of volunteers, even when the party imploringly searches for crowds of supporters to surround the leader. Similarly, a Conservative campaign manager “tell[s] [the party] we have a volunteer shortage . . . and [sends] the minimum volunteers possible.” While seemingly minor disruptions, these examples serve to illustrate potential risks for the central party when local campaign support is needed to benefit from earned media and build a sense of campaign momentum.

The prevalence and nature of undisciplined behaviour indicates broader difficulties in the relationship between the central party and local actors. During initial discussions held with national and local campaign actors, most claimed they were appreciative of their counterparts. However, these sentiments changed as more details emerged, during both interviews and campaign observation. The frustrations and disappointments expressed revealed the potentially fractious nature of local-national party relations. Generally speaking, the central party may feel that constituency campaigns have an unwarranted sense of their uniqueness. Central party officials deal with large-scale trends and sophisticated polling data. In managing a multitude of dynamic campaign challenges, they may have little patience for local intransigence. Conversely, local campaigns often feel that the central party is unavailable to help when needed, distant and detached from local realities, and guided by optics and efficiency, with little regard for local actors.

There is often a lack of discernible consequences for undisciplined campaign behaviour. This reality stems from the central party's limited capacity to monitor and sanction local actors. In many ridings, the central party has limited knowledge of what local actors are actually doing. With finite resources, parties concentrate their efforts in target constituencies. According to 2015 Conservative candidate Andy Brooke (Kingston and the Islands), “They weren't over our shoulders because they couldn't be . . . but [they would] like to be.” Even if the central party is aware of undesirable local campaign activity, the party frequently lacks the ability to punish or coerce local actors. NDP strategist Brad Lavigne emphasizes that the party must rely on the goodwill of local campaigns. Conversely, Conservative strategist Hamish Marshall notes that the central party unsuccessfully tried to instil local discipline during the 2015 election by “screaming at people” (see, Braid, Reference Braid2015). In extreme cases, the central party may seek to remove a local candidate. However, as a Liberal Party strategist explains, this is an outcome the party seeks to avoid because it will produce an “automatic negative news story” and reflects poorly on the central campaign. In many cases, it appears that local compliance is driven by self-discipline, which is instilled by candidate training and party socialization (Marland, Reference Marland2020: 38). Marshall contends that most local campaigns will follow party procedures in order to stay in their party's good graces. Yet this does not apply when undisciplined behaviour goes undetected or when local actors are undaunted by potential reputational costs. Despite impressive organizational capabilities, the scope and magnitude of central party authority is limited in these respects.

To date, most scholarship on party discipline focuses on the behaviour of elected officials and minimally considers the particularities of the campaign context. Further research in this area is needed to investigate possible benefits and concerns surrounding undisciplined constituency campaign behaviour. In some respects, undisciplined behaviour may inject local flavour into federal campaigns and even promote voter engagement. For example, several local candidates noted their disdain for party instructions to only canvass at the homes of likely supporters and to spend less than one minute at each door. Instead, they visited a diverse array of residents, including non-voters, and displayed a community-centric mindset rather than a data-gathering focus. At the same time, potential concerns with undisciplined behaviour include the accountability implications of locally dissonant campaign messaging when voters remain unaware of the claims underpinning local campaigns across the country. Along these lines, future research may include other venues where constituency campaigns navigate party obligations against local and personal preferences, such as voter canvassing and social media. Further study is also required to determine whether undisciplined behaviour has discernible electoral benefits for local candidates that engage in it.

In sum, local campaigns are subject to relatively strict central party oversight, enabled by digital campaign technologies, but they are sometimes compelled to diverge from their parties and follow their own preferences. Using newly collected data, this article has examined whether and why local campaigns engage in behaviour that defies central party preferences. The article establishes definitional parameters and indicators for the concept of undisciplined behaviour, presents its findings on the frequency of undisciplined behaviour and contends that local campaigns can be considered conscientious, conflicted or maverick in their adherence to party norms and procedures. The extent of undisciplined behaviour revealed in this sample is relatively high. Moreover, candidates in rural ridings and in noncompetitive ridings in the sample are disproportionately undisciplined. The article's analysis identifies patterns of undisciplined behaviour by constituency campaigns, which are then categorized according to their primary causes: innovation, insubordination and incompetence. These findings demonstrate the circumscribed and uneven nature of central party authority during a campaign period.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for this research. The author wishes to thank the journal's anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback. The author would also like to thank the interview subjects and other participants who generously took part in this research.