Introduction

A number of writers have pointed out that Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) path-breaking ‘The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism’ (TWWC) neglected East Asia (e.g. Kim, Reference Kim2014; Ku & Jones Finer, Reference Ku and Jones Finer2007), with much of this debate focusing on extension (i.e. classifying nations that were not in Esping-Andersen’s original 18 nations, such as South Korea). However, Japan was the only non-Western case included in his 18 nations, and so the focus here is on ‘mis-classification’ (e.g. Ferragina & Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser2011). Kasza (Reference Kasza2006, p. 2) claimed that all research on Japanese welfare policy is at least implicitly comparative, but most scholars of Japanese welfare policy, both Japanese and foreign, have neglected comparative research.

Japan was given very little attention in the original ‘three worlds’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990), but has been given much more attention subsequently by Esping-Andersen (see below) and others (e.g. Estevez-Abe, Reference Estevez-Abe2008; Kasza, Reference Kasza2006; Krämer, Reference Krämer2013; Peng, Reference Peng2000). For example, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1997) termed Japan a ‘potentially deviant case’ that posed a particularly intriguing challenge to his welfare regime typology. According to Kasza (Reference Kasza2006), the mainstream view of Japan’s welfare involved terms such as late, laggard, weak, or distinctive, and reflects a welfare society rather than a welfare state. He continues that most divergence theorists have interpreted Japan as either a unique melange of contradictory traits or as part of an East Asian Welfare Regime (EAWR) (p. 7). Estevez-Abe (Reference Estevez-Abe2008) pointed to ‘the puzzle of Japan’s Welfare Capitalism’, terming it ‘an outlier in comparative studies of advanced industrial societies.’ She wrote that the Japanese welfare state calls to mind Kurosawa’s movie, ‘Rashomon’, because every scholar disagrees about what it looks like.

Ebbinghaus (Reference Ebbinghaus2012) reported that 10 of 13 typologies classified Japan, with a consistency of 55% (classified as Liberal 5.5 times out of 10), one of the lowest of his 30 countries. Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser (Reference Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser2011) stated that in their 23 studies Japan was classified 14 times: 0 SD; 3 CD; 9 Liberal; 2 Hybrid. They classified Japan as a ‘medium-high internal consistency countries’. Kim (Reference Kim2014) found 23 studies that classified Japan’s welfare regime along with other welfare states. Japan was classified as the Liberal regime 13 times, as the Conservative three times, and as ‘other’ models seven times.

This confusion over classification obscures two important questions. First, can Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990, Reference Esping-Andersen1999) approach capture the essence of East Asian nations in general and Japan in particular? Put another way, can Japan best be regarded as one of the three worlds, a fourth world, or a hybrid or unique case? More fundamentally, can the three worlds approach, essentially based on Europe, capture a very different nation? Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1997) reflected that in the ‘Three Worlds’, the Japanese ‘welfare state’ was analysed as a basically unproblematic case within a typology of political economies that was quite Eurocentric.

Ku with Jones Finer (Reference Ku and Jones Finer2007) discussed the issue of how far ‘East Asian Welfare Studies’ can or should break free from Western notions of regime classification, which have been termed ‘Eurocentric’ (Ku with Jones Finer Reference Ku and Jones Finer2007), ‘Swedocentric’ (Takegawa, Reference Takegawa2005a), with a ‘strong European bias’ (Hudson & Hwang, Reference Hudson, Hwang and Izuhara2013), associated with ‘ethnocentric western social research’ (Walker & Wong, Reference Walker and Wong1996), a ‘Western lens’ (Hudson & Kühner, Reference Hudson and Kühner2012) and a ‘social democratic bias’ (Estevez-Abe, Reference Estevez-Abe2008).

There are a number of arguments that suggest that the worlds of welfare may be a historically and geographically bound typology (e.g. Ferragina & Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser2011; Powell & Kim, Reference Powell and Kim2014; Rice, Reference Rice2013; Vrooman, Reference Vrooman2012). It has been argued that East Asian welfare deviates fundamentally from Western experience and needs to be examined in its own particular context (e.g. Goodman & Peng, Reference Goodman, Peng and Esping- Andersen1996; Kwon, Reference Kwon1997; Lee & Ku, Reference Lee and Ku2007; Takegawa, Reference Takegawa2005a). In other words, East Asian welfare should be seen in terms of ‘genetic indigenous analyses’ (Goodman & Peng, Reference Goodman, Peng and Esping- Andersen1996) or in ‘intrinsic’ rather than ‘extrinsic’ terms. Estevez-Abe (Reference Estevez-Abe2008) suggested that, rather than viewing Japan as an outlier that does not fit any institutional category, there is a need for a new way of thinking about welfare states and the politics that produces and sustains such states that broadens the traditional analysis of the welfare state by introducing the concept of functional equivalent programmes. ‘More than any other advanced industrial society, Japan illuminates the limitations of existing notions of the welfare state’. Her ‘structural logic approach’ took advantage of the Japanese case to develop an alternative institutional argument of welfare politics in advanced industrial societies. In short, she aimed to solve the mystery of the Japanese welfare state by reconceptualising the very concept of the welfare state.

Second, and related, much of the above discussion draws on Western scholars, writing in the English language. However, Takegawa (Reference Takegawa2005a, p. 169) criticised ‘the uncritical adoption of regime theory to non-European countries’ as ‘welfare orientalism’ which has three trends including Swedocentrism, Eurocentrism and ethnocentrism, and the debate over which welfare regime Japan belongs to is a ‘false question’. Skinkawa and Tsuji (Reference Skinkawa, Tsuji, Beland and Petersen2014, p. 209) pointed out that social citizenship is central to Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990), but ‘has remained marginal to Japan’s social policy discourse’. While there has been some limited recognition of these voices, virtually nothing is known about the views of Japanese scholars writing in their own language. Given the inconsistent and often conflicting accounts on Japan’s welfare model between researchers, this article attempts to review the literature classifying the Japanese welfare regime, including for the first time accounts in the Japanese language (cf Powell & Kim, Reference Powell and Kim2014 for Korea). This allows scholars who do not read Japanese to compare Western and Japanese accounts of Japan’s place within the welfare regime approach.

Search strategy

The article selection was based on the four broad inclusion criteria. The studies should (1) categorise Japan in terms of welfare or social policy; (2) be a ‘mainstream’ analysis (i.e. based on decommodification rather than defamilization (see below)); (3) be published in English or Japanese since 1990; and (4) categorise the whole welfare system rather than one service such as health care or housing.

The term ‘mainstream’ follows Orloff (Reference Orloff1993, Reference Orloff1996, Reference Orloff2009) in focusing on research such as Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) that does not thematize gender. In other words, it focuses on ‘decommodification’ rather than ‘defamilization’. The gendered analysis of welfare states focuses on ‘defamilization’, but this term has produced different spellings, definitions, and operationalizations, as well as a number of cognate terms such as ‘dedomestication’ and ‘degenderization’ (e.g. Kröger, Reference Kröger2011; Kurowska, Reference Kurowska2016 Lohmann & Zagel, Reference Lohmann and Zagel2016; Saxonberg, Reference Saxonberg2013;).

Moreover, while Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1999) discussed defamilization, he defined it in a very different way to feminist scholarship in terms of the freedom of the family rather than women’s freedom from the family (Bambra, Reference Bambra2007). As Orloff (Reference Orloff2009) notes, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1999) blunted the radical edge of the concept. This review examines the ‘decommodifaction’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990) rather than ‘mainstream’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1999) or feminist concepts of ‘defamilization’. This is not because defamilization is unimportant, but because it is important, and requires separate and more extended analysis (e.g. Kröger, Reference Kröger2011; Kurowska, Reference Kurowska2016 Lohmann & Zagel, Reference Lohmann and Zagel2016; Saxonberg, Reference Saxonberg2013;).

As the classification of Japan may be found in large N quantitative studies, studies of the East Asian Welfare Model, or solely focused on Japan, we conducted a broad search for English language articles. First, we updated the findings of Kim (Reference Kim2014), resulting in 16 articles. Second, we searched with three groups of key words in the Web of Science (‘Asia’, ‘East Asia’ and ‘Japan’; ‘productivist’, ‘developmental’ and ‘Confucious’; and ‘welfare regime’, ‘welfare capitalism’, ‘welfare state’ and ‘welfare typology’) in the Web of Science. We found 640 articles containing at least one key word from all of each three group (e.g. ‘Asia’‘productivist’‘welfare regime’). Applying to inclusion criteria to Abstracts and then full text resulted in 11 further articles. Excluding six duplicate articles from the first search resulted in 21 English language articles (16 11 6 21).

The Japanese language search followed the same process, with two changes. First, it added another key word of ‘welfare system’, because the words are often used in the discussion on welfare regime in Japanese academia. Second, Japanese researchers often publish a journal article and republish the article in another journal or as a book chapter after modifying the original article’s content or conclusion, or adding more materials. We counted those similar studies by a same author as a single study. Given the academic practice particular in Japan, we included some book chapters or books, unlike the English language search which is based on journals articles. A search of two Japanese-language search engines (CiNii and bookplus) resulted in 1059 and 1753 studies respectively, which were narrowed down by the same process of applying inclusion criteria to abstracts and full-text sources to 19 studies. We found a total of 40 sources (21 in the English language, with 15 by West-based commentators and 6 by Asia-based authors; and 19 in the Japanese language; coded as W1, A1, J1 etc in the Appendix).

Results

Esping-Andersen’s classification of Japan

Before turning to the search results, we discuss Esping-Andersen’s classification of Japan (largely found in his books, and so excluded from our search of articles). Japan was given very little attention in the original ‘three worlds’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). For example, although appearing in the Tables, it was not an index entry (along with further 6 of the 18 nations). However, Esping-Andersen has commented on the classification of East Asia and/or Japan on five occasions, with some problems of interpretation both between and within attempts.

First, on the basis of de-commodification, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) placed Japan in the Conservative cluster, with the second lowest score (i.e. close to Liberal nations) (p. 52; Table 2.2). For stratification, Japan was seen as medium on Conservatism; high on Liberalism and low on Socialism (p. 74; Table 3.3). Japan appeared in only two of the five tables in the chapter on state and market in the formation of pension regimes (Ch. 4). In terms of the public-private pension mix, Japan was 18th (lowest) in social security pensions with 54.4%; 7th for public-employee pensions; 5th for occupational pensions; and 2nd for individual annuities (p. 85; Table 4.3). It was classified as a ‘corporative state-dominated insurance system’ ‘pension regime’ in which status is a key element in the pension programme structure, along with ‘conservative’ nations. According to subsequent scholars, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) classified Japan as ‘medium (Conservative) for de-commodification and liberal for stratification’ (Castles & Mitchell, Reference Castles and Mitchell1992), ‘Christian Democratic’ (Ferragina & Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser2011), and ‘Conservative/Liberal’ (Ebbinghaus, Reference Ebbinghaus2012).

Second, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1997) pointed to Japan’s low levels of social expenditure, the comparatively modest social benefits, and the rather rudimentary social safety net, which has all the manifestations of a very residual model. He argued that social-welfare guarantees outside the public sector were so strong and comprehensive that the state welfare needed only be modest and residual. In other words, Japanese society was so infused with welfare that it does not need a welfare state. This thesis identified three core components in the Japanese welfare mix: tradition (Buddhist teachings and ‘Confucian’ familial and communal solidarities and obligations); corporate occupational welfare; and the ‘invisible’ component of the absence of many of the heavy social problems that other welfare states must address.

He stated that his original answer to the question of whether Japan qualifies as a distinct regime was basically a ‘no’, but added that the subsequent debate suggested otherwise, and reconsidered if the original ‘no’ was actually warranted (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1997). He wrote that ‘Japan seems to combine elements of all three regimes’: a formidable commitment to maximum and full employment (social democratic); a legacy of status-segmented insurance and familialism (conservative) and residualism and heavy reliance on private welfare (liberal). He asked if the Japanese model is unique by being a hybrid, in that the different elements of state, market and family combine in such a way as to make the Japanese welfare- state regime a qualitatively different variant. He concluded that it is ‘virtually impossible to identify the Japanese welfare state in the typology of regimes’, as it appears to combine – in fairly equal measure – key elements of both the liberal- residual and the conservative-corporatist model. However, the family element (a core element of the ‘Confucian’ thesis) was the least convincing part of the ‘Japan is unique’ thesis, as there was hardly anything uniquely Japanese in the way that familialism remains a vibrant and key component in the welfare mix, forming part and parcel of the conservative regime’s main attributes. However, he hesitated to draw any conclusions at all, as it is ‘arguably the case that the Japanese welfare system is still in the process of evolution’ and has ‘not yet arrived at the point of crystallization’ (p. 187). As a recent ad hoc construct, the Japanese welfare-state model may not yet have sunk its roots. Perhaps, then, the only viable conclusion is that a final adjudication on how to define the Japanese welfare state must await the passage of time. According to later scholars, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1997) regarded Japan as a hybrid (Ferragina & Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser2011; Ku & Jones Finer, Reference Ku and Jones Finer2007).

Third, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1999, p. 82) stated that there were several reasons why Japan may be included in the conservative model; it blended vital regime attributes in a way which made it either unique or hybrid; appeared a hybrid case with a mix of liberal and conservative traits; with a strong case for assigning Japan squarely to the conservative regime (pp. 90–92). The powerful presence of Confucian teachings throughout Japanese social policy was a functional equivalent of Catholic familialism; Japanese social security is highly corporatist. Japanese occupational welfare was mainly the privilege of core workers. He appeared to dismiss the ‘unique’ label (although Japan appears to be treated as separate in tables in chapters 6–8), arguing that it appeared to be a hybrid case, but then stated that there was ‘a strong case for assigning Japan squarely to the conservative regime.’ Ebbinghaus (Reference Ebbinghaus2012) concluded that Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1999) classified Japan as ‘Conservative’.

Fourth, Ku with Jones Finer (Reference Ku and Jones Finer2007) pointed out that in the preface to the Chinese edition of TWWC, Esping-Andersen observed that East Asian welfare states can be interpreted in one of two ways: either as a hybrid of his own liberal and conservative models or as an emerging fourth welfare regime (cf Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1997 on Japan).

Fifth, according to Hayashi (Reference Hayashi2006, pp. 248–249), in his Introduction to the Japanese translation of TWWC, Esping-Andersen asked ‘if there exists a Japanese-style welfare state’. According to Hayashi (Reference Hayashi2006, p. 249) Esping-Andersen ‘provided several suggestions but not a clear answer, seemingly having trouble grasping the characteristics of Japan’s welfare state’. Moreover, according to Takegawa (Reference Takegawa2005a), Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) classified Japan as ‘Conservative’, but more recently as a hybrid of the liberal and conservative regimes, but Vrooman (Reference Vrooman2012, p. 471) stated that Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990, Reference Esping-Andersen1999) regards the Mediterranean and Eastern Asiatic systems as variants of the corporatist model.

Search results

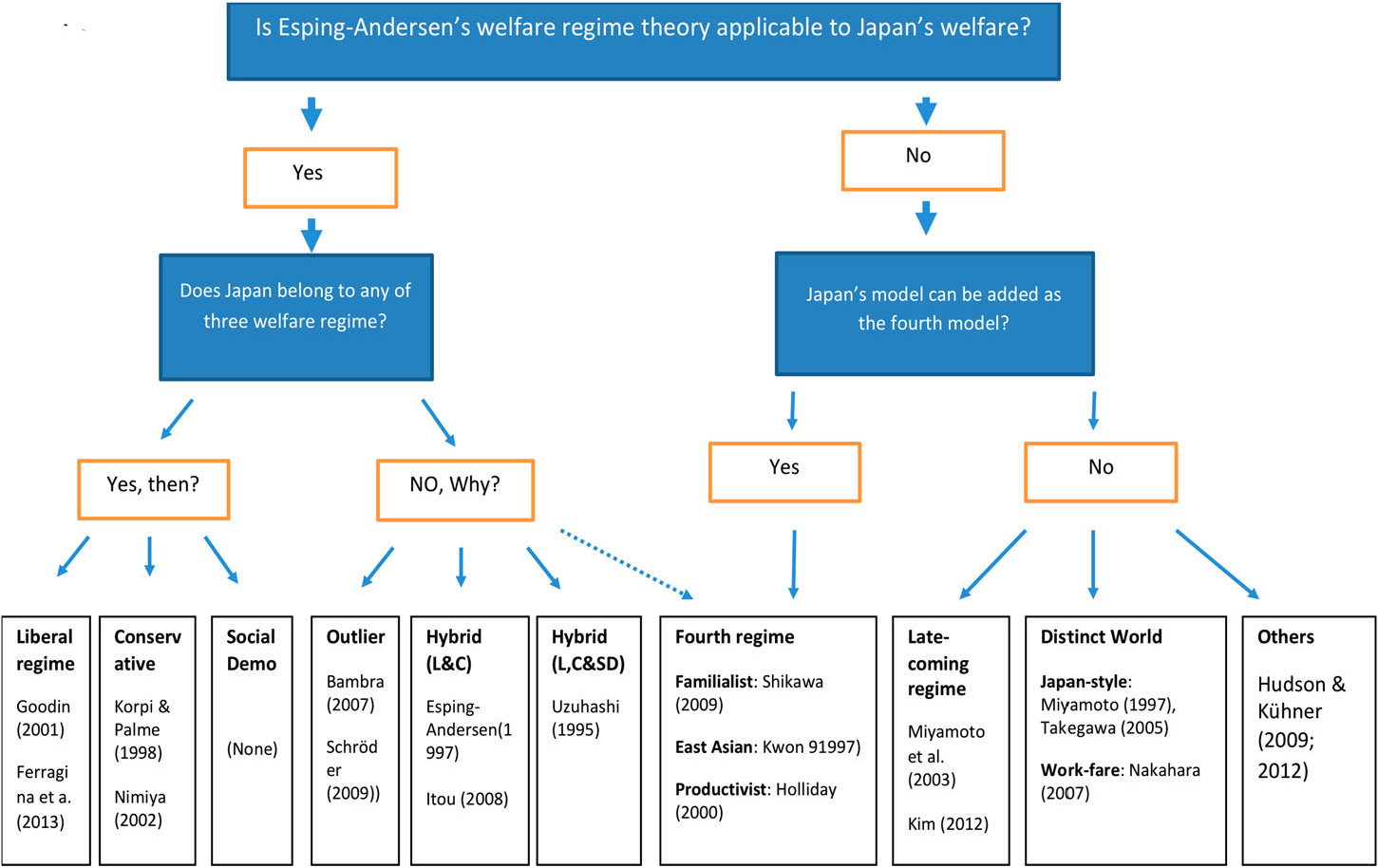

Like Korea (Powell & Kim, Reference Powell and Kim2014), Japan’s welfare regime seems to be a ‘chameleon’ changing its appearances to different viewers, with some support for almost every possible classification. We find eight possible types: liberal; conservative; hybrid; outlier; fourth regime; distinct world, late-coming model, and other or unclear models (but no social-democratic classification). However, these are not simply eight categories, but reflect fundamental difference about whether the ‘three worlds’ approach is appropriate as a starting point for exploring the welfare system of a nation such as Japan (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Decision rules for regime types. Correction on diagram- fourth regime Kwon (Reference Kwon1997).

Liberal

It is noticeable that no researchers based in Japan or other Asian nations regarded Japan as liberal, in contrast to the majority (9 out of 15) of Western studies (see Appendices 1 and 2). For example, based on a different 2 2 matrix (see Appendix 3 for details), Castles and Mitchell (Reference Castles and Mitchell1992) and Goodin (Reference Goodin2001) classified Japan as a Liberal nation. Obinger and Wagschal (Reference Obinger and Wagschal2001) used cluster analysis for time periods from 1960 to the early 1990s with a wide range of socio-economic, political-institutional and outcome variables. Japan was seen as a ‘stepchild’ which starts out in the cluster of the economic laggards (peripheral cluster), but later joined the Anglo-Saxon family. Powell and Barrientos (Reference Powell and Barrientos2004) examined the welfare mix in terms of social security, education and active labour market policies over time using cluster analysis, concluding that Japan was a Liberal nation.

Scruggs and Allan (Reference Scruggs and Allan2006) replicated Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) decommodification index using a new dataset. They pointed to an error regarding Japan, which on their figures became one of the least generous and most commodifying welfare states, making it a clear case of welfare-state liberalism. Bambra (Reference Bambra2006) similarly pointed to an overlooked error in Esping-Andersen’s original calculations that led to the incorrect positioning of Japan, which she firmly placed within the Liberal decommodification group, between Canada and Ireland. Moreover, she updated data from 1980 to 1998/9, which also placed Japan in the Liberal group. Shalev (Reference Shalev, Mjset and Clausen2007) used factor analysis on 13 policy indicators drawn from Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) to classify Japan as a Liberal regime.

Castles and Obinger (Reference Castles and Obinger2008) used cluster analysis techniques to establish the existence of coherent policy profiles using a combination of some 16 social policy, labour market and tax policy indicators as outcome variables for the 1960–73, 1974–95 and 1960–95 periods. In terms of patterns of public policy in 1960–75, Japan (and Switzerland) were clear outliers that did not belong to any of the particular families, but their closest resemblance was to the policy profile of the countries of Southern Europe. By the early 2000s, they remained outliers, but now show greater similarities with the policy profile of the English-speaking than the continental countries. Turning to the origins of public policy patterns (1945–75), Japan belonged to a cluster of a ‘territorially heterogeneous group of nations’ (also including Italy, Finland and Ireland), which have all been laggards in economic development terms, but became ‘late modernisers’, with the ‘stepchild’ Japan later adopted by the English-speaking family.

Ferragina, Seeleib-Kaiser, and Tomlinson (Reference Ferragina, Seeleib-Kaiser and Tomlinson2013) took a dynamic temporal approach to welfare regime analysis, focusing on unemployment protection and family policy. They employed the concepts of decommodification and defamilialization to construct four models using Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA). The first empirical model employed a temporal approach to analyse the concept of decommodification over three decades. This found Japan as a Liberal welfare state with a low degree of universalism and ‘lean’ cash transfers.

Conservative/corporatist

Only three studies (Western, Asian and Japanese respectively) regarded Japan as Conservative. Korpi and Palme (Reference Korpi and Palme1998) classifed Japan as corporatist. Lee and Ku (Reference Lee and Ku2007) examined the developmental characteristics of Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, analysing a set of 15 indicators of 20 countries, based on data from the 1980s and 1990s by factor and cluster analysis. They found five distinct groups which can be described as three major and two minor clusters. They stated that the second group clearly represented corporatist welfare regimes, including Austria, France, Italy, Germany, and especially Japan. However, there was a large distance between Japan and the other members of this group, which suggests that Japan may better be described as having more ‘pro-corporatist’ characteristics than typical corporatist ones. Ninomiya (Reference Ninomiya2002) argued that Japan can be located between the Conservative and the Liberal models but it was closer to the former type. However, Japan’s model was undergoing a transition from the Conservative type to the Liberal welfare regime in the longer term.

Social democratic

Although no writers classified Japan as a Social Democratic regime, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1997) noted that Japan contained an element of the Social Democratic regime in ‘a formidable commitment to maximum and full employment’, pointing out that superficially Japan’s insistence on education and employment appeared very similar to Sweden’s celebrated ‘productivistic’ social policy; i.e. a pre-emptive policy to ensure that the labour market produced welfare and equality rather than social risks and poverty (cf Estevez-Abe, Reference Estevez-Abe2008). Some Japanese researchers also stressed that the nation had some elements of the Social Democratic welfare regime for its characteristic ‘government’s involvement for full employment’ (Uzuhashi, Reference Uzuhashi1995) or ‘low unemployment rate and political stability’ (Appendix).

Hybrid

While six of the 19 Japanese-language studies concluded that Japan was a hybrid between Liberal and Conservative regimes, the only Western study to suggest this was Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1997), who appeared to conclude that Japan had the appearance of a hybrid system rather than a distinct model. Shinkawa (Reference Shinkawa2000) stated that Japan’s model was unlike the Liberal model in that the Japan’s liberal element is intertwined with its strong familialistic value. For example, Japan had the liberal features for its occupational welfare and small government (i.e. weak redistribution). On the other hand, its welfare was definitely Conservative, considering its income system based on the male-bread winner model, its discriminative tax benefits system designed against female workers’ participation in labour market, and its public social insurance system fragmented industry-by-industry. Hiraoka (Reference Hiraoka and Fujimura2006) also pointed out that stratification was relatively weaker due to the nation’s equality in social insurance benefits supported by public finance. However, it also had famialistic elements but lacked such liberal elements as means test or selectivism. Ito (Reference Ito2008) classified Japan as a hybrid between Liberal and Conservative models. The nation’s liberal elements were residual state welfare and strong occupational welfare, while its conservative ones included strong familialism and industry-based fragmented social insurance system. Since the 1990s, Japan’s welfare regime approached the Liberal welfare regime mainly due to the retreat of familialism and rising maketisation while maintaining its ‘hybrid’ characteristics. Uzuhashi (Reference Uzuhashi1995) also concluded that Japan is a mixture of Liberal and Conservative regimes with some components of Social Democratic welfare regime.

Outlier

This categorisation appeared in one Western study. Schröder (Reference Schröder2009) utilised principal component and cluster analysis to combine existing typologies on production and welfare regimes, using indicators that reect the welfare and production system including the structure of labour markets, the financial system, income distributions, industrial relations and the form of the welfare state. He placed Japan and Switzerland out of the three groups of Anglo-American, Scandinavian and continental European ones. In fact, Japan was placed in a completely different category apart from other Western welfare states in the dendogram of hierarchical cluster analysis (p. 23).

The fourth regime, East Asian welfare regime or familialistic welfare regime

Some Japanese reserachers pointed to the limitation of the concept of welfare to Japan. For example, Uzuhashi (Reference Uzuhashi1995, p. 13), even though he defined Japan as a mixture of the two welfare regmes, also stated in the conclusion that ‘it is difficult to precisely analyse the nature of the Japan’s welfare regime with Esping-Andersen’s framework, and it is also difficult to clarify its characteristics’. He stressed that it would be inappropriate to apply the typology to Japan without revision (Uzuhashi, Reference Uzuhashi1995). It was also found that few studies in Japan placed the nation neatly in any of the original types and the terms of ‘mixture’ or ‘hybrid’ appeared in description of its welfare. The welfare regime concept, based on historical and contemporary analysis of Western welfare states, revealed its limitations when applied without revision to non-Western societies (Takegawa, Reference Takegawa2007, p. 122). Facing the difficulty in defining Japan’s welfare through the lens of the welfare regime concept, they understood that either the framework has fundamental weakness or the typology can be applied only to Western welfare states, not to Japan (Miyamoto, Reference Miyamoto2008). In turn, Japanese commentators have recognised Japan’s welfare as the fourth model in addition to the original troika and they began to suggest Japan as the ‘familialistic model’ (e.g. Shinkawa, Reference Shinkawa, Miyajima, Nishimura and Kyogoku2009a, Reference Shinkawa2009b; Shizume & Kondo, Reference Shizume and Kondo2013; Tsuji, Reference Tsuji2012). For example, Shinkawa (Reference Shinkawa, Miyajima, Nishimura and Kyogoku2009a) stressed the family’s powerful role by stating that Japan has controlled the public social spending since the middle 1970s by increasing the roles of family and private company. Japan’s liberal trend becomes significant since the 1990s, but the nation also maintains its familialistic element. An, Lin, and Shinkawa (Reference An, Lin, Shinkawa and Shinkawa2015), focussing on the East Asian states of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan also conclude that Japan maintains family-oriented welfare regime as the fourth type.

On the other hand, researchers based in other Asian nations have experimented with another fourth concept of ‘the East Asian welfare model’. There are a number of different approaches to the EAWM, with some differences on the main characteristics of the EAWM and its constituent nations (e.g. Aspalter, Reference Aspalter2006; Kwon, Reference Kwon1997). Kwon (Reference Kwon1997) examined three comparative perspectives of an expenditure approach, standard analysis of cross-sectional redistribution, and welfare regimes on East Asian welfare systems with special reference to Japan and Korea. He stated that despite some similarities between the conservative welfare regimes on the one hand and the welfare systems in Japan and Korea on the other, the type of conservative welfare regimes did not successfully capture the distinctive characteristics of the welfare systems in these two countries. First, there was a subtle but important difference in the emphasis on the role of the family. Second, the level of welfare provision in Japan and South Korea in particular was considerably lower than in Germany and Austria, typical conservative welfare states. Third, there was a difference in the nature of class politics underlying the development of the welfare state. He concluded that there is a case for an ‘East Asian welfare model’, at least regarding Japan and Korea.

It seems that Holliday (Reference Holliday2000) may have arrived at a ‘fourth regime’ via a different route, in that he accepted Esping-Andersen’s approach as a starting point, but added a new criterion – ‘the relationship between social and economic policy’ – to Esping-Andersen’s list. He proposed a productivist welfare capitalism regime that ‘stands alongside’ Esping-Andersen’s three worlds. He found that although some common features of ‘productivist welfare capitalism’ existed between his four countries, there are three different clusters: ‘facilitative’ (e.g. Hong Kong), ‘development-universalist’ (e.g. Japan in particular, and Taiwan and Korea, though limited), and ‘developmental-particularist’ (e.g. Singapore).

Aspalter (Reference Aspalter2006) examined the EAWM in terms of five countries of Japan, Korea, China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, and suggested the EAWM as the fourth ‘ideal-typical welfare regime’. He presented an overview of ideal-typical welfare regimes of Social Democratic, Corporatist/Christian Democratic, Liberal, and (East Asian) Conservative Welfare Regimes. He characterised the latter in terms of the focus of social policy on the role of: the Individual (weak), the Family (strong), the Market (strong), and the State (weak)

Aspalter (Reference Aspalter2011) later termed it the ‘The Pro-Welfare Conservative welfare regime’ in East Asia. He argued that the main elements of a welfare regime are: (a) the type of social rights guaranteed, (b) the welfare mix applied; (c) the specific emphasis of the role of the state, the market, the family, and the individual; (d) the degree of decommodification; (e) the degree of stratification; and (f) the degree of individualisation. He compared five ideal-type welfare regimes in a table. The East-Asian Pro-Welfare Conservative welfare regime is seen as ‘pro-welfare conservative’ (main ideology), with ‘productive social rights’, low levels of guaranteed minimum income for wages, state pensions, and social assistance, Bismarckian social insurance and/or provident funds; universal and means-tested social assistance, health care services (welfare mix), and emphases that are increasing on the state, decreasing on the market, strong on family, and weak on the individual. It has medium-low decommodification, medium stratification, and medium individualisation.

Drawing on the ‘productivist welfare capitalism’ thesis of Holliday (Reference Holliday2000), Choi (Reference Choi2012) claimed that Japan was the most advanced welfare state, and the earliest productivist regime in East Asia. He plotted changes over time on two dimensions- productivist or not, and welfare state or not- forming four quadrants. Japan was a Productivist/Informal Security Regime until the 1970s, when it became a productivist/welfare-state regime, it was the 1980–2000s period. Since 2010, Japan moved toward Post-productivist/welfare state regime.

Late-coming welfare state

A number of scholars recognised the time gap between the East Asian nation and Western welfare states in the historical development of welfare states (e.g. Kim, Reference Kim2012; Miyamoto, Peng, & Uzuhashi, Reference Miyamoto, Peng, Uzuhashi and Esping-Andersen2003). One of ways to compare differences between welfare states would be ‘to analyze effect of time on socioeconomic changes, which Esping-Andersen’s three typology did not discuss in detail.’ (Miyamoto et al., Reference Miyamoto, Peng, Uzuhashi and Esping-Andersen2003, p. 296). Kim (Reference Kim2012) also emphasised that researchers ignored the time axis which involved the issue of ‘late-coming’ in the development of welfare states. Miyamoto et al. (Reference Miyamoto, Peng, Uzuhashi and Esping-Andersen2003) regard Japan as a ‘late-coming welfare state’. They cautioned against a contemporaneous comparison between Western welfare states and Japan, given the relatively late development of Japan’s welfare state. Japan, as a late-coming welfare state, formed and developed family welfare and corporate welfare instead of a welfare state. Kim (Reference Kim2012) also categorised Japan as a ‘late-coming’ welfare model. According to him, Japan’s strong job security, corporate welfare and family welfare served as a de-facto social insurance system and they were the main characteristics of Japan’s welfare when compared with the Western welfare states. The reason of such characteristics was the late development of Japan’s welfare state.

Distinct world

This approach seems to suggest that Japan tended to have special or unique characteristics, rather than being one of three worlds or a broader EAWM. Put another way, this category appears to examine an alternative framework based on the intrinsic elements of Japan’s welfare. For example, Miyamoto (Reference Miyamoto, Okazawa and Miyamoto1997) introduced a new theoretical model combining employment regime and welfare regime and suggests ‘Japan-style welfare regime’. Japan developed a ‘small regime’ because job security for male breadwinner employees in each private companies and familialism traditionally replace the role of the state social security. On the other hand, Sweden developed a ‘big regime’ in connection by securing job security through its flexible labour market. Takegawa (Reference Takegawa, Takegawa and Kim2005b) also formulated a new theoretical frame based on Japan’s characteristic welfare politics, welfare benefit systems and regulations. He stressed that Japan weak social democracy and strong state bureaucracy, low social spending and high spending on public projects and strong regulation on the economy and weak regulation on society. Nakahara’s (Reference Nakahara2007) noted that Japan has developed a ‘workfare’ welfare regime where state formed a relatively limited level of the welfare system with family and corporate taking relatively more complementary roles.

Others or unclear

This is a more problematic or residual category, and a case can be made for classifying these studies elsewhere (e.g. Hybrid). However, we have classified two studies of Hudson and Kühner (Reference Hudson and Kühner2009, Reference Hudson and Kühner2012), focusing on the mix between productive and protective elements, here. Hudson and Kühner (Reference Hudson and Kühner2009) noted that typologies of welfare are still largely drawn on the basis of measures of social protection rather than social investment. They used fuzzy set ideal type analysis (FSITA) to explore data for 23 OECD countries in three-time points: 1994, 1998 and 2003 that incorporates both productive and protective elements of social policy. They placed Japan in their ‘weak protective’ group with Spain, France, Czech Republic, Portugal, and the UK. This presented a challenge to Holliday (Reference Holliday2000) as neither of the two included East Asian countries (Korea, Japan) qualified as a purely productive ideal type. They concluded that Japan was a ‘weak-protective hybrid’. Hudson and Kühner (Reference Hudson and Kühner2012) updated their earlier analysis, and extended it beyond the OECD to 55 high and higher-middle income countries. Japan now joined the group of ‘weak’ countries, with Australia, Bulgaria, and the UK. They said little about Japan, but noted that the classification of Australia and the UK hinted that these two nations steer a mid-course between the American and European traditions – offering a cut down version of each model – rather than sharing the same features as the U.S.A as suggested by most typologies. In other words, this group may represent a ‘hybrid’, but a different type of hybrid to that of a hybrid based on (say) Esping-Andersen’s Liberal and Conservative worlds. Similarly, using FSITA, Yang (Reference Yang2017) regarded Japan as a ‘Residual balanced model’ being ‘balanced’ because Japan has both relatively weak productivist elements and realtively weak protective elements.

Discussion/conclusion

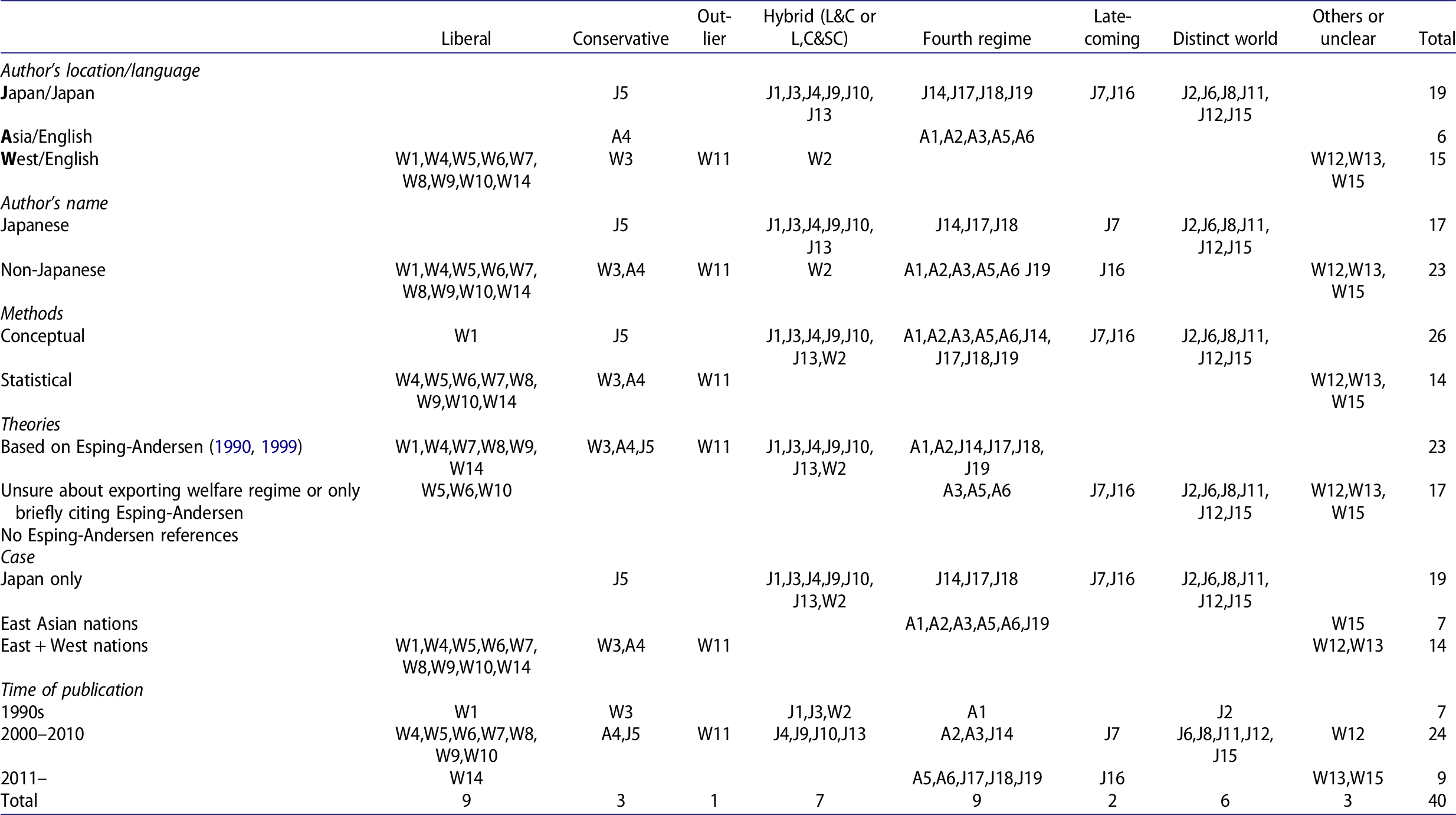

As suggested above, a number of scholars have suggested that Japan is a ‘poor fit’ in typologies of welfare regimes (e.g. Ebbinghaus, Reference Ebbinghaus2012; Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1997; Estevez-Abe, Reference Estevez-Abe2008; Ferragina & Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser2011; Kasza, Reference Kasza2006; Kim, Reference Kim2014; Krämer, Reference Krämer2013; Peng, Reference Peng2000). This review article adds to this debate with three original features. First, it is the first structured review on Japan’s welfare regime. Second, it is the first attempt to combine all the articles on Japan’s welfare regime written in either English or Japanese. Almost half of the sources were published in the Japanese language, and so remain inaccessible to most Western researchers. Third, it presents a wider range of classifications compared to previous studies. This means that it is able to come to a number of original conclusions (see Tables 1 and 2, and Appendix), which – by definition- would only have been evident to a small number of bilingual social policy scholars interested in Japan’s welfare regime, rather than a much wider group of scholars interested in welfare regimes and comparative social policy.

Table 1. Classification of studies.

Table 2. Total of classification studies.

First, we have presented a wider range of classifications than previous reviews, which were generally based on two of Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) three types of ‘Liberal’ and ‘Conservative’, and ‘Hybrid’. Second, and most important, there are some major differences between the conclusions of scholars based on location and/or language. For example, no researchers based in Japan or other Asian nations regarded Japan as liberal, in contrast to the majority (10 out of 18) of Western studies. In other words, there is a major difference between how Western and Asian-based (and particularly Japan-based) scholars regard Japan’s welfare regime.

This brings us to the difficult question of explaining these stark differences. The first possibility is a temporal explanation. Put another way, it is important to look beyond static classifications towards dynamic analyses. The original data of Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) was based around the year of 1980. Japan has seen major changes since then (below). While Western studies have maintained their conclusion on Japan as liberal over time, Japanese studies have not regarded Japan as ‘hybrid’ since 2011. Before 2011, 6 out of 15 studies regarded Japan as hybrid between the regimes, but there has been more of a recognition of a fourth regime or a distinct world since then. Moreover, some longitudional analyses suggested a change of regime over time (e.g. Castles & Obinger, Reference Castles and Obinger2008; Choi, Reference Choi2012; Obinger & Wagschal, Reference Obinger and Wagschal2001).

Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1997) argued that Japan had all the manifestations of a very residual model, such as low levels of social expenditure, comparatively modest social benefits, and a rather rudimentary social safety net. However, he stated that ‘arguably the case that the Japanese welfare system is still in the process of evolution’ and has ‘not yet arrived at the point of crystallization’ (p. 187). He continued that ‘as a recent ad hoc construct, the Japanese welfare-state model may not yet have sunk its roots. Perhaps, then, the only viable conclusion is that a final adjudication on how to define the Japanese welfare state must await the passage of time’ (p. 187).

With ‘the passage of time’, there have been major increases in social expenditure in Japan. Hong (Reference Hong2014) compared total public social expenditure as a percentage of GDP in liberal, social democratic, conservative, Southern European and East Asian countries’ groupings over the period 1990–2009 (which cover the period of many of the reviewed studies). In 1990, Japan had the lowest expenditure compared to other groupings at 11.1%, but this had risen to 21.2% by 2009. This increase was faster than any of Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) other nations, and by 2009 Japan’s expenditure remained low, but was higher than a few ‘Liberal’ nations such as Australia, Canada and the U.S.A. By 2018, Japan was above the OECD average for public social spending (21.9% versus 20.1%) and total net social spending (which also takes into account taxes breaks as well as private spending for social purposes) (23.5% versus 20.9%) (OECD, 2019). However, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) rejected expenditure as the ‘gold standard’ of welfare regimes (see below).

The second possibility is methodological. There were some major methodological differences between Western and Japanese studies: the former (13 out of 15) mostly used statistical methods, while studies by Japanese authors mainly adopted conceptual approaches to their nation’s welfare. Other Asian studies were conceptual, with only one exception. Similarly, Western studies analysed Japan not as a single case but one of several welfare states (14 out of 15). Japan was not regarded as a qualitatively different welfare state by the Westerners, which encouraged them to run statistical models after mixing the East Asian nations with other Western states. On the other hand, Japanese researchers concentrated on their own state as a single case (18 out 19) and Asian studies tended to analyse Japan together with other Asian nations (5 out of 6). These approaches tend to fit within Amenta’s (Reference Amenta, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003) 2 2 historical/ comparative classification of ‘Comparative only’ (large N statistical) and ‘Non comparative historical or present orientated case study’ (N 1). There are few instances of combining both approaches to produce ‘Comparative and Historical Research Proper’.

The third (linked) possibility relates to differences in different concepts underlying the methods. As noted above, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) argued that welfare regimes were based on decommodification, stratification and the welfare mix rather than social expenditure. Similar to previous reviews (e.g. Ebbinghaus, Reference Ebbinghaus2012; Ferragina & Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser2011), the large N comparative studies have rarely used all three concepts, and some studies have not even used the most dominant concept of decommodification. The Japanese language studies have drawn upon a wide variety of concepts (including social expenditure), but have rarely discussed decommodification.

In short, the temporal explanation is probably the least convincing for the difference in classification between English and Japanese language studies. However, it is unclear whether the greatest variance is explained by methodological (large N statistical versus single N case studies) or the underlying conceptual reasons.

In conclusion, a review of English and Japanese language studies has shown eight possible classifications for Japan: liberal; conservative; hybrid; outlier; fourth regime; distinct world, late-coming model, and other or unclear models (but no social-democratic classification). Moreover, there is significant disagreement between English and Japanese language scholars over placing Japan in these categories. However, these are not simply eight categories, but reflect fundamental difference about whether the ‘three worlds’ approach is appropriate as a starting point for exploring the welfare system of a nation such as Japan.

Put another way, it raises significant case selection issues (Kim, Reference Kim2014) over the inclusion of Japan as the only non-Western case in Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) original 18 nations. It is far from clear that being an OECD nation is a sufficient inclusion factor (cf Powell & Kim, Reference Powell and Kim2014; Powell & Yoruk, Reference Powell and Yoruk2017). In short, is it appropriate to use a Western lens of analysis (cf Estevez-Abe, Reference Estevez-Abe2008; Miyamoto, Reference Miyamoto and Uzuhashi2003; Takegawa, Reference Takegawa2005a, Reference Takegawa2007; Walker & Wong, Reference Walker and Wong1996)?

There seems to be four responses to this problem. First, nations such as Japan could be excluded from ‘regime analysis’ because they are too different. Second, this lack of fit may lead to considering a new way of thinking about welfare states such as introducing the concept of functional equivalent programmes through a ‘structural logic approach’ (Estevez-Abe, Reference Estevez-Abe2008). Third, regimes analysis could be abandoned as an ‘illusion’. Kasza (Reference Kasza2002) explained how his highly cited article originated in an effort to place Japanese welfare policy in a comparative perspective, but Japan’s poor fit in existing welfare typologies suggested reasons to be sceptical of the regime concept altogether as a tool for comparative analysis. However, our preference is – at least initially- to increase the synergy between the difference approaches as comparative and historical work in social policy has helped to generate theoretical arguments to be tested on larger data sets, just as cross-national quantitative work has provided hypotheses for comparative and historical appraisal (Amenta, Reference Amenta, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003, p. 110).

It is possible that the two very different approaches may have something to learn from each other, as in thesis antithesis synthesis. On the one hand, Western studies may need to justify the inclusion of Japan, the only non-Western welfare state in their future analysis of welfare regimes. They tend to run statistical models with social policy indicators, largely based on Western history, and attempted to place Japan, rather awkwardly, among qualitatively different Western welfare states. On the other hand, Japanese researchers focused mainly on their own nation as a single case, and they may consider widening their horizon to see Japan together with other East Asian nations or welfare states. If the western studies were biased toward statistics without conceptual understanding of Japan, Japanese studies were arguably biased toward a conceptual approach without statistics. This article is the first that has reviewed both English and Japanese articles on Japan’s welfare and the first to introduce studies written in Japanese to English language readers. Now that we are aware of very different approaches to and conclusions about Japan’s welfare regime, the topic appears ripe for greater co-operation between scholars to produce greater synergy from different languages and approaches.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed https://doi.org/10.1080/21699763.2019.1641135.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Martin Powell is Professor of Health and Social Policy at the Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham. He has published over 100 peer reviewed articles, and has research interests in welfare regimes. He has published recent articles on the theoretical foundations of welfare regimes, and welfare regimes beyond the original ‘welfare capitalism’ nations such as Korea and Turkey.

Ki-tae Kim is associate research fellow at Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA). He received his Ph.D. in Social Policy at University of Birmingham under the supervision of Professor Martin Powell. The title of his doctoral thesis is ‘The relationship between income inequality, welfare regimes and aggregate health’. He used to work as a staff reporter at The Korea Times (2000–2006) and The Hankyoreh (2006–2012). After getting the Ph.D. in 2016, He worked a postdoctoral researcher at Ewha Womans University and Soongsil University (2017–2018). His research interest is inequality, income policy, health policy, health inequality and welfare state. He published books such as ‘Report on Korea’s health inequality’ (Sharing House, 2012, in Korean) and ‘Hospital business’(Cine21 Books, 2013, in Korean) and journal articles including ‘The relationship between income inequality, welfare regimes and aggregate health: A systematic review’ (European Journal of Public Health, 2017, 27(3), 397–404) and ‘Revisiting the income inequality hypothesis with 292 OECD regional units. International Journal of Health Services’ (International Journal of Health Services, 2019, 49(2), 360–370).

Sung-won Kim is an Assistant Professor of Faculty of Letters and Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology at the University of Tokyo. Japan. He received his Master’s degree (2002) and Ph.D. degree (2007) in Sociology from the University of Tokyo. He worked for the Institute of Social Science of the University of Tokyo (Assistant Researcher, 2007–2009), Faculty of Economics of Tokyo Keizai University (2010–2015), and Faculty of Sociology and Social Work of Meijigakuin University (2016–2017). From 2018, he has joined the University of Tokyo. His research interests are in East Asian welfare state, social policy and employment policy, and comparative methods. His main publications include Late-coming welfare state: Korean and East Asia in comparative perspective (University of Tokyo Press, 2008), Modern theories of welfare states (Minervashobo, 2010) and Welfare state in Japan and Korea (Akashishoten, 2014).