Introduction

Case conceptualization is described as the “the heart of evidence-based practice” (Bieling and Kuyken, Reference Bieling and Kuyken2003; p. 53). Most CBT therapists agree that case conceptualization is a core competency, but there are different views about how to use case conceptualization in practice (Flitcroft, James, Freeston and Wood-Mitchell, Reference Flitcroft, James, Freeston and Wood-Mitchell2007).

Consider the case of Beth (age 20), admitted to a residential unit following an escalating pattern of self-injury. Her presenting issues included self-injury, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression. Beth's assessment data suggested that her mother had longstanding and severe substance abuse problems. Her father and then a step-father sexually abused Beth starting when she was 6 years old and continuing until she ran away from home at aged 16. Throughout childhood, Beth saw school as a refuge and she formed an important relationship with a female English teacher who supported Beth's love of poetry. During secondary school she formed positive relationships with some female peers, most of whom worked on the school's in-house student magazine. When Beth left home she moved in with a man in his 20s who was substance dependent; while intoxicated he could become violent. Beth confided that she had witnessed frequent domestic violence between her parents and was now entrenched in a pattern of violence in her own relationship.

Beth's therapist faces a range of issues commonly faced by CBT therapists.

• Given Beth's presenting issues, what should be the primary therapy focus?

• In what order should the presenting issues be tackled?

• How do Beth's presenting issues relate to one another, if at all?

• What CBT protocols are relevant here? What treatment course do I follow if no particular protocol seems appropriate?

• Should I work with Beth's history, which seems at face value to be immediately relevant to her presenting issues? How do I work with her history without exacerbating her post-traumatic stress disorder?

• What is the goal of the therapy? Beth is apparently a survivor of sustained and chronic abuse and disadvantage. Is alleviation of her symptomatic distress sufficient or is it important to include a goal to help rebuild and promote more successful functioning in the future?

In short, Beth's therapist faces the primary question each CBT therapist asks at the beginning of therapy: “How do I use my training and experience along with evidence-based therapy approaches to help this person with these particular issues presented at this time?” For many clinicians the answer is, “It depends upon the case conceptualization.” And yet research suggests that different therapists are likely to construct different case conceptualizations to understand Beth's presenting issues (Kuyken, Fothergill, Musa and Chadwick, Reference Kuyken, Fothergill, Musa and Chadwick2005).

This paper describes a new model for case conceptualization that helps answer the questions above and addresses many of the challenges posed by poor inter-therapist reliability regarding case conceptualization. First, we offer a definition of case conceptualizationFootnote 1 along with a summary of the available research. Then we describe a new approach to case conceptualization that uses the metaphor of a case conceptualization crucible in which a client's particular history and presentation is synthesized with theory and research to produce a description and understanding of clients' presenting issues that can be used to inform therapy. We draw out implications for training and recommendations for future research.

What is case conceptualization?

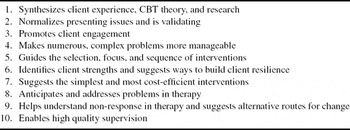

“Case conceptualization is a process whereby therapist and client work collaboratively to first describe and then explain the issues a client presents in therapy using cognitive-behavioural theory. Its primary function is to guide therapy in order to relieve client distress and build client resilience” (Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley, Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2008). There is a good deal of consensus in the literature about the functions of case conceptualization (see Eells, Reference Eells2007). We summarize these in Table 1. In short, conceptualization is a tool for improving CBT practice by helping describe and explain clients' presentations in ways that are theoretically informed, coherent, meaningful and lead to effective interventions.

Table 1. Ten functions of case conceptualization in CBT

There are two primary approaches to CBT case conceptualization: disorder specific models and generic models. The development of CBT has included carefully observed accounts of specific disorders, including depression (Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery, Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979), anxiety disorders (Beck, Emery and Greenberg, Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985), personality disorders (Beck, Freeman, Davis and Associates, Reference Beck, Freeman and Davis2003), and substance misuse disorders (Beck, Wright, Newman and Liese, Reference Beck, Wright, Newman and Liese1993) that have varying degrees of empirical support (see Bieling and Kuyken, Reference Bieling and Kuyken2003). Other papers in this special issue provide exemplars of disorder specific approaches within CBT. CBT therapists use conceptualization to adapt these disorder-specific models to incorporate client specific information (for examples, see chapters in Tarrier, Reference Tarrier2006).

Generic approaches to case conceptualization are based on a higher level cognitive theory of emotional disorders and are typically suggested when clients present with complex or co-morbid presentations (Beck, Reference Beck2005; Padesky and Greenberger, Reference Padesky and Greenberger1995; Persons, Reference Persons1989). Typically, these approaches provide a framework for identifying the core beliefs, underlying assumptions and behavioural strategies that contribute to a client's presenting issues. These elements are often linked to the client's relevant developmental history.

We suggest a new framework for case conceptualization. The model of case conceptualization we propose evolved from (a) our clinical experience as therapists, supervisors, and trainers, and (b) our struggle to respond to challenges presented by the empirical research on CBT case conceptualization. The following sections recap the relevant research that forms the basis for our approach.

What is the evidence base for case conceptualization?

The CBT case conceptualization research literature has been reviewed comprehensively elsewhere (Bieling and Kuyken, Reference Bieling and Kuyken2003; Kuyken, Reference Kuyken and Tarrier2006). Bieling and Kuyken (Reference Bieling and Kuyken2003) articulate some key questions to consider when evaluating the evidence base. We recap these questions along with a synopsis that highlights important issues for CBT therapists and clinical researchers to consider.

Is CBT case conceptualization reliable? That is to say, can therapists agree with each other when asked to conceptualize the same case using the same conceptualization format?

While CBT therapists tend to agree on more descriptive levels of conceptualization (e.g. the presenting issues), reliability becomes poor at levels requiring greater inference (e.g. central beliefs, maintenance factors) (e.g. Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Fothergill, Musa and Chadwick2005; Mumma and Smith, Reference Mumma and Smith2001; Persons, Mooney and Padesky, Reference Persons, Mooney and Padesky1995). There is some emerging evidence that training, therapist experience, competence and use of more structured conceptualization schematics improve reliability (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Fothergill, Musa and Chadwick2005; Persons and Bertagnolli, Reference Persons and Bertagnolli1999). This emergent consensus has important implications delineated in our approach to case conceptualization below.

Are CBT case conceptualizations valid? That is, do conceptualizations relate meaningfully to clients' experience, are they internally consistent/coherent and can they be cross-validated with other measures of clients' experiences?

Research in this area has only emerged recently (e.g. Mumma and Mooney, Reference Mumma and Mooney2007). Several studies converge on the finding that CBT therapists with greater expertise are more likely to produce conceptualizations that are higher quality in terms of being more coherent, elaborated, and concise (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Fothergill, Musa and Chadwick2005; Mumma and Mooney, Reference Mumma and Mooney2007). Similarly, focused training in case conceptualization improves the coherence and quality of case conceptualization across therapy modalities (Kendjelic and Eells, Reference Kendjelic and Eells2007). There is no research to date bearing on the question of whether CBT conceptualizations can be cross-validated with other measures of clients' experiences. Additionally, of course, if CBT conceptualizations are not reliable in content, they cannot achieve standards of validity.

Do case conceptualizations improve therapy processes and outcomes?

There is now a growing literature related to this question. Studies with high external validity demonstrate that, when CBT therapists use case conceptualization approaches in real world settings, outcomes are comparable in effect size to outcomes observed in randomized controlled trials (Kuyken, Kurzer, DeRubeis, Beck and Brown, Reference Kuyken, Kurzer, DeRubeis, Beck and Brown2001; Persons, Roberts, Zalecki and Brechwald, Reference Persons, Roberts, Zalecki and Brechwald2006). However, a more compelling research design is a head-to-head comparison of individualized approaches that use CBT case conceptualization with standardized approaches that use treatment manuals. Taken together, the key studies in this area do not support the position that treatment approaches based on individualized conceptualizations unambiguously enhance outcomes (Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie, Reference Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie2003; Nelson-Gray, Herbert, Herbert, Sigmon and Brannon, Reference Nelson-Gray, Herbert, Herbert, Sigmon and Brannon1989; Schulte, Kunzel, Pepping and Schulte-Bahrenberg, Reference Schulte, Kunzel, Pepping and Shulte-Bahrenberg1992). However, some studies that individualize treatment have provided modest support for the benefits of a CBT case conceptualization approach (Ghaderi, Reference Ghaderi2006; Schneider and Byrne, Reference Schneider and Byrne1987; Strauman et al., Reference Strauman, Vieth, Merrill, Kolden, Woods, Klein, Papadakis, Schneider and Kwapil2006). Resolving this disparity in the research literature is important to forming a conceptual basis for case conceptualization; we return to this issue when we describe our approach to case conceptualization.

Is conceptualization acceptable and useful to clients and therapists?

A small number of studies address this question and suggest that clients have mixed reactions to conceptualization. Some clients describe the benefits of case conceptualization (similar to those listed in Table 1), and some clients report being upset and overwhelmed by CBT and cognitive-analytic therapy case conceptualizations (Evans and Parry, Reference Evans and Parry1996; Pain, Chadwick and Abba, Reference Pain, Chadwick and Abba2008). CBT therapists, on the other hand, generally regard conceptualization more unambiguously as an integral and vital part of CBT (Flitcroft et al., Reference Flitcroft, James, Freeston and Wood-Mitchell2007).

In sum, on the one hand case conceptualization is described by leading commentators as a first principle of CBT that serves multiple functions (Table 1). On the other hand, theoretically-driven, high quality case conceptualization that is experienced as unambiguously helpful by clients seems to be the exception rather than the rule. Moreover, strong evidence that conceptualization enhances CBT outcomes is strikingly absent. How can we make sense of this discrepancy?

A new approach to case conceptualization

A schematic that helps therapists combine their knowledge of CBT theory and research with the particularities of their clients' presentations improves the quality of case conceptualizations (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Fothergill, Musa and Chadwick2005; Mumma and Smith, Reference Mumma and Smith2001). We offer a new approach to case conceptualization that we believe addresses many of the challenges posed by research and which resonates with our experience as CBT therapists, supervisors and trainers. We use the metaphor of a crucible to describe case conceptualization because a crucible is a strong container in which different elements go through a process of substantive and lasting change (see Figure 1). The case conceptualization crucible mixes relevant CBT theory and research with the person's particular history and experience to produce a description and explanation of the person's presenting issues in therapy that is original and unique to the client. The crucible facilitates the challenging process of combining the nomothetic (theory and research about populations of people) and the idiographic (a person's particular experience).

Figure 1. Case conceptualization crucible

Our crucible metaphor incorporates three key principles to guide therapists during case conceptualization: levels of conceptualization, collaborative empiricism, and incorporation of client strengths.

Principle 1. Levels of conceptualization

Like chemical reactions in a crucible, conceptualization changes over time. Much of the case conceptualization research examining reliability and validity does not acknowledge this principle. Instead, research studies present therapists with a large amount of information all at once and expect them to produce a coherent fully formed conceptualization (e.g. Chadwick et al., Reference Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie2003; Persons et al., Reference Persons, Mooney and Padesky1995). We argue that conceptualizations would be more reliable and valid if therapists were presented with information in a more naturalistic way and asked to develop conceptualizations that evolve over time in the context of new information and client responses to therapy interventions.

Initial conceptualizations are typically quite descriptive; therapists assess clients' presenting issues and help the client describe these issues in cognitive and behavioural terms. Beth (the client described at the beginning of this chapter) and her therapist agreed to focus on three goals: learn alternatives to self-injury when she felt distressed; reduce her PTSD symptoms; and return to college. As Beth was able to describe her presenting issues in the context of her current situation and past history of abuse, these experiences became less frightening to her and her self-destructive behaviours became more understandable. Beth's highest distress was associated with the severity and frequency of her PTSD symptoms and she currently managed these emotions by cutting herself. Thus, Beth and her therapist chose PTSD and self-harm as the initial foci of therapy.

Following initial descriptions of presenting issues, case conceptualizations become more explanatory, identifying triggers and maintenance factors. Here disorder-specific models or generic approaches like functional analysis (e.g. Kohlenberg and Tsai, Reference Kohlenberg and Tsai1991) are typically used. Beth's therapist used CBT models of PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000), depression (Clark, Beck and Alford, Reference Clark, Beck and Alford1999) and anger (Beck, Reference Beck2002) to inform Beth's conceptualization.

For example, Figure 2 shows the first explanatory conceptualization Beth and her therapist sketched out. It synthesizes a contemporary approach to PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Ehlers, Clark, Hackmann, McManus and Fennell, Reference Ehlers, Clark, Hackmann, McManus and Fennell2005) with Beth's experiences to provide an understanding of how her intrusive images and memories are triggered and how the cutting and PTSD are maintained (Weierich and Nock, Reference Weierich and Nock2008). By sketching this schematic diagram with Beth in the early phases of therapy she was able to see the links between seemingly disparate experiences (her memories, PTSD symptoms, self-blaming thoughts and cutting behaviour). This conceptualization normalized her experiences (“I thought I was going mad”), engaged her in therapy by providing hope, and provided the rationale for early therapy interventions focused on exposure and reframing beliefs associated with her trauma memories.

Figure 2. Conceptualization of triggers and maintenance for Beth's PTSD symptoms and cutting behaviour to inform treatment plan

In middle and later stages of CBT, conceptualization uses higher levels of inference to explain how predisposing and protective factors contribute to clients' presenting issues. Predisposing factors help explain why a client is vulnerable to their presenting issues. Protective factors highlight strengths that can be used to build resilience as described in our third principle below. Figure 3 shows the type of conceptualization that might be derived throughout therapy as Beth and her therapist build a shared understanding of Beth's beliefs and strategies in the context of her developmental history.

Figure 3. Conceptualization of Beth's vulnerability and resilience to inform treatment plan

Principle 2. Collaborative empiricism

Chemical reactions in a crucible are facilitated by heat. Collaborative empiricism provides the heat for the process of case conceptualization. Collaboration refers to both therapist and client bringing their respective expertise together in the joint endeavour of describing, explaining and helping resolve the client's presenting issues. The therapist brings his/her relevant knowledge and skills of CBT theory, research and practice. The client brings his/her in-depth knowledge of the presenting issues, relevant background and the factors that contribute to vulnerability and resilience.

We maintain that one of the reasons research regarding the reliability and acceptability of CBT conceptualization is not more positive is that typically these studies are based on relatively unilateral therapist-derived conceptualizations presented to the client in a given therapy session (e.g. Evans and Parry, Reference Evans and Parry1996). We propose that when conceptualization is collaborative, clients are more likely to provide checks and balances to therapist reasoning errors, feel ownership of the emerging conceptualization, and perceive a compelling rationale for treatment.

Empiricism refers to: (i) making use of relevant CBT theory and research in conceptualizations; and (ii) using an empirical approach in therapy that is based on observation, evaluation of experience, and learning. At the heart of empiricism is a commitment to using the best available theory and research within case conceptualizations. Given the substantial evidence base for many disorder-specific CBT approaches, often there will be a close match between client experience and theory. For example, a person presenting with panic attacks can normally benefit greatly from jointly mapping his or her panic experiences onto contemporary CBT models of panic disorder (Clark, Reference Clark1986; Craske and Barlow, Reference Craske, Barlow and Barlow2001).

Nonetheless, even when a CBT model is closely matched to a client's presenting issues it is important to collaboratively derive the case conceptualization so the client understands the applicability of the model to his or her issues. Also, throughout therapy, conceptualizations inform choice points regarding treatment options and resolution of therapy challenges. An individualized conceptualization will more helpfully inform these choice points. When clients experience multiple or more complex presenting issues it is often not possible to map directly to one particular theory and still provide a coherent and comprehensive conceptualization that is acceptable to the client. Nonetheless, as shown in the case of Beth, the cognitive theory of PTSD was able to significantly inform work on two of her three goals, reduction of self-harm and PTSD symptoms (Figure 2). A more generic longitudinal conceptualization helped her work towards her third goal, returning to her studies (Figure 3).

Another aspect of empiricism is the use of empirical approaches to clinical decision making. Therapists and clients develop hypotheses, devise adequate tests for these hypotheses, and then adapt the hypotheses based on feedback from therapy interventions. This makes CBT an active and dynamic process, in which the conceptualization guides and is corrected by feedback from the results of active observations, experimentation and change. An early focus on Beth's PTSD symptoms led to rapid therapy gains; these improvements provided support for the validity and utility of her initial conceptualization (Figure 2).

Case conceptualization requires integration of complex information within the case conceptualization crucible. Moreover, as therapy progresses, therapists and clients typically make greater inferences as they develop explanatory conceptualizations using data from the client's developmental history. We contend that one of the reasons research has failed to demonstrate that individualization improves therapy outcomes is that the principle of collaborative empiricism is not practised effectively to manage this complexity. Dietmar Schulte and his colleagues conducted a series of studies to examine the reasons why deviations from treatment manuals tend to compromise outcomes (Schulte and Eifert, Reference Schulte and Eifert2002). They found that therapists tend to move away from therapy methods (e.g. exposure) to therapy process (e.g. addressing patients' motivation) too soon, too often and sometimes for the wrong reasons. Therapists' decisions about when to deviate from therapy manuals should be made (a) empirically and (b) collaboratively because these two types of processes allow corrective feedback.

Principle 3. Include client strengths and conceptualize resilience

Most current CBT approaches are concerned either exclusively or largely with a client's problems, vulnerabilities and history of adversity. We advocate that therapists identify and work with client strengths at every stage of conceptualization. According to our case conceptualization model, a strengths-focused approach helps achieve the two primary purposes of CBT: alleviation of client distress, and building client resilience (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2008). A strengths focus is often more engaging for clients and offers the advantages of harnessing client resilience in the change process to pave a way toward lasting recovery.

Identifying and working with clients' strengths and resiliency begins at assessment and continues at each level of conceptualization. The initial assessment with Beth sought to draw out strengths and use constructive language to describe her difficulties. In addition to listening to Beth's difficulties, her therapist enquired about times when Beth was able to cope successfully. Throughout therapy, the identification and use of client values, longer-term goals and positive qualities fosters long-term recovery and full participation in life.

Beginning in the first assessment session it was clear to Beth's therapist that, despite the significant adversity in her life, Beth had what she called “attitude” and what the therapist described as a willingness to take on challenges, question authority and “fight her corner”. These qualities helped Beth cope when she faced abusive people. Moreover, when channelled correctly, they enabled her to succeed in a number of areas of her life, notably at school and in her peer relationships.

Resilience is a broad concept referring to how people negotiate adversity. It describes the processes of psychological adaptation through which people draw on their strengths to adapt to challenges and maintain their well-being (Rutter, Reference Rutter1999). The crucible is also an apt metaphor for understanding how to conceptualize an individual's resilience (Figure 1). Appropriate theory can be integrated with the particularities of an individual case using the heat of collaborative empiricism. Because resilience is a broad multi-dimensional concept, therapists can either adapt existing theories of psychological disorders or draw from a large array of theoretical ideas in positive psychology (e.g. Snyder and Lopez, Reference Snyder and Lopez2005).

Beth and her therapist developed a conceptualization of her resilience that recognized her success in navigating the adversity she experienced: “I did survive the worst of it, sort of” she acknowledge early in therapy. In middle and later stages of CBT, the conceptualization of Beth's resilience informed her decision to set a goal of completing college. Building on her constructive beliefs (“If I show attitude, I can succeed; others like me”) and strategies (reading and writing poetry; cultivating “attitude”) she was able to articulate the steps involved in returning to college (see the left side of Figure 3). Once she succeeded in her admission to college, Beth was able to use her skills to surmount various obstacles. Subsequent success experiences reinforced her beliefs and strategies, strengthening her resilience.

It is possible that the research examining the impact of conceptualization on therapy process and outcome might be more compelling if conceptualizations included client strengths and resilience. For example, we propose that clients are less likely to find conceptualization overwhelming and distressing when conceptualization is as much about what is right with them as about the problematic issues that lead them to seek help. Moreover, as Beth's case illustrates, conceptualizations of resilience offer natural pathways toward client goals.

Conclusion

We concur with commentators (Beck, Reference Beck1995; Butler, Reference Butler, Bellack and Hersen1998) who assert that case conceptualization is a foundation of CBT. However, we argue that we need a new approach to case conceptualization that has the potential to address some of the clinical and empirical challenges therapists face. Specifically, we advocate therapists navigate clinical and conceptualization challenges using three guiding principles: collaborative empiricism, evolving levels of conceptualization and incorporation of client strengths. This approach, briefly outlined here, is developed fully in Kuyken et al. (Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2008).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.