Michael Loewe's still essential Records of Han Administration (1967) raised the question, intentionally or not: what, exactly, do we mean when we speak of “administration” in the early Chinese empires? Certainly, the manuscripts from Juyan 居延 surveyed in Records show the broad array of activities that Han officials and soldiers carried out, from tax collection to signal observations to criminal arrests and investigations. Since the Han military installations along the Hexi 河西 corridor were staffed by soldiers and officials on government salaries,Footnote 1 it makes perfect sense to see most of the documents they produced as administrative. In the decades after the publication of Records, archaeologists began to discover and excavate an increasing number of pre-Qin 秦 and early imperial tombs, many of which yielded new manuscripts, from versions of the Laozi 老子 to fu 賦 verses. Scholars have regularly described these texts as “philosophical” or “literary,” contrasting them with administrative texts (including those recovered from the arid northwest). This division can hold great heuristic value,Footnote 2 even when we recognize that excavation site and medium are equally important for differentiating types of manuscripts.Footnote 3 Accordingly, this essay makes no attempt to reject the distinction.

Nevertheless, the distinction is porous, insofar as texts used in government administration could use complex rhetorical patterns and specialized references to authoritative knowledge. Nor did conventionalized patterns of administrative language prevent the expression of emotions.Footnote 4 In received texts, the most obvious examples of heavily embellished administrative writings include imperial edicts, as well as memorials and kindred documents officials submitted to the throne. Such texts essential to administrative operations represent some of the most sophisticated and influential writings available to students of early China.Footnote 5 The rhetoric of persuasion, in which the most educated had been well schooled, circulated from the capital to outlying regions in the empire through this sort of writing. Drawing upon literary and philosophical refinements was thus a routine part of some administrative work.Footnote 6 Rather than a set boundary between the “literary” and the “administrative” categories, then, we might imagine a continuum for texts produced as part of governmental operations, extending from the most basic records entirely bereft of rhetorical flourishes (e.g., population registries) to the most refined documents circulating at the highest levels (edicts, records of court debates, remonstrations, petitions, and so forth).Footnote 7

This essay explores that continuum by examining texts called ji 記, through both the received corpus and manuscripts recovered from the northwest desert that date to Western Han 西漢 (202 b.c.e.–9 c.e.), Xin 新 (9–23 c.e.), and Eastern Han 東漢 (25–220 c.e.). One key point to recall in this discussion: it would be a serious mistake to reduce ji to a specific written form, not least because one of the word's fundamental meanings is simply “to write down” or “to record.” Depending on context, when used as a noun, ji can be translated in a variety of ways: “annals,” “record,” “note,” and “list” are all good choices. As the excavated evidence confirms the great diversity of uses for the word ji during the four centuries under review, we would be ill-advised to try to establish clear categories of usage for ji, let alone generic distinctions. Indeed, with the exception of shu 書 (“writings”), there is probably no other single word referring to written texts in classical Chinese with a similarly broad range of meanings. Unlike shu, however, texts called ji are distinctly uncommon in transmitted pre-imperial sources, even when we factor in the usual difficulties of dating pre-imperial texts.Footnote 8 When the word does appear in these pre-imperial sources, it typically refers to “annals” or “records,” typically those stored by royal courts. By contrast, ji appears in numerous Han texts, often to indicate much less formal “notes” and “letters.” This essay, then, grapples with tracking what appears to be a dual change: ever more texts over time come to be labeled as ji, while some ji become increasingly informal in tone.

Why and how did these shifts happen? How did a word that referred primarily to relatively rarified textual forms, maintained by politically powerful institutions, come to be associated with a much less formal kind of writing that in some cases required exchange or knowledge of other texts in order to establish its meaning? Given the paucity of relevant sources, this essay cannot explain the multiple factors that likely drove such complex changes, but, notably, the evidence from both excavated and received administrative texts suggests that the division between formal and informal documents predates the proliferation of ji.Footnote 9 At this point, what is clear is that received and excavated Han administrative texts exhibit a broad array of ji. As the examples cited below suggest, we can confidently characterize many of these ji as “notes” or “letters,”Footnote 10 and they fulfilled a broad range of functions. By my hypothesis, governance required different registers of formality, and ji became an important yet less formal means for ensuring that certain tasks were carried out. As we will see, to the extent that such neat divisions can be postulated, these ji were very often not just top-down orders, but rather texts that invited or required exchanges of items or information between people. Over time, this incorporation of ji into a broad range of administrative work, whether in official government pronouncements or in epistolary exchanges, apparently gave the word a much wider and subtler palette of meanings than it enjoyed in the pre-imperial period. “Records of Han administration” can therefore help us understand not only facts about governmental operations during the early empires, but also shifts in manuscript practices. Sometimes these records even open windows onto the emotional intimacies possible in administrative work.

Annals and Records: Received Texts and Ji in Pre-Imperial Times

When we look at the sources that can be plausibly, if not definitively, dated to pre-imperial times, the word ji appears but rarely. This is especially true of ji as a noun, though even verbal uses of ji (“to write down,” “to record”) are uncommon.Footnote 11 Writing a history of ji based on evidence from pre-imperial texts thus becomes impossible. For instance, in the mammoth Zuo zhuan 左傳 of today (successor to the Han-era Zuoshi chunqiu 左氏春秋) the word appears just three times, all in a single statement supposedly made by Guan Zhong 管仲 to the prince Qi 齊.Footnote 12 After learning that his liege planned to interfere in the domestic politics of the small kingdom of Zheng 鄭, Guan Zhong warned him not to pursue a nefarious scheme hatched at a covenant meeting of the realms. As Guan Zhong explained, “no realm failed to record” (無國不記) what happened at such meetings, so treacherous schemes would soon become common knowledge, with the inevitable result the speedy collapse of the entire covenant.Footnote 13 The anecdote is part of a larger theme in the Zuo zhuan emphasizing the role recordkeeping played to circumscribe the choices available to important political actors.Footnote 14 As Guan Zhong's statement suggests, ruling houses maintained records of major events and agreements in their archives; a range of pre-imperial and early imperial texts, not to mention bronze inscriptions, also attests to the existence of such records (in chronicle form or not).Footnote 15

Plausibly, this association of ji with recordkeeping by the royal courts continued through the end of the Zhanguo 戰國 period (475–221 b.c.e.). In the Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋 (Annals of Lü Buwei; comp. 239 b.c.e.), the word ji appears in four anecdotes, three of which refer to a record of some kind. Close reading of two of these vignettes show the need to deliberate carefully on translation. The first comes in a story of Zixia 子夏, who while traveling to Jin 晉 encounters a man “reciting” (du 讀) a passage from a shi ji 史記 (archival record), which states that “Jin troops and three pigs forded the Yellow River” (晉師三豕涉河). Zixia argues that the graphs san shi 三豕 (“three pigs”) should actually read as the date ji hai 己亥 (i.e., number 38 in the sexagenary cycle), a proposition proven correct after Zixia arrives in Jin and makes inquiries about the phrase in question.Footnote 16 The oft-cited story, if somewhat ambiguous,Footnote 17 plainly presumes that Zixia or someone else could consult an archival document to ascertain what was recorded in writing. The fact that the word in question is a date (ji hai) suggests that understanding ji as a chronological “annals,” here, could be justified, though by no means with absolute confidence, since the story does not clarify the precise format of the text.

Our second story is quite another matter. It describes a hunt in which King Zhuang of Chu 楚莊王 (r. 613–591) shoots a rhinoceros. Before the king can finish the job, an attendant pushes the king aside to take the final, killing shot. Incensed at the unwarranted interference, the king orders his underling to be executed but soon he relents, after some officials protest that the rhinoceros-killer's exemplary service record suggests he must have had good reason to so act. Three months later, the man sickens and dies. Around the same time, Chu successfully attacked Jin, and when the victorious army returns to claim its rewards, the younger brother of the rhinoceros-killer, to King Zhuang's astonishment, steps forward to ask for his award. The king demands an explanation, and the man insists on the loyalty of his deceased brother:

臣之兄嘗讀故記曰殺隨兕者。不出三月。是以臣之兄驚懼而爭之。故伏其罪而死。

My brother once recited an old record (gu ji) that said, “The one who kills a rhinoceros will not live longer than three months.” This is why my brother was terrified and fought to kill it. He was ready to accept the blame for his crime, and so died.Footnote 18

The king ordered open the “Ping Storeroom” (ping fu 平府), at which point his officials discovered “there was indeed such an old record” (gu ji guo you 故記果有), and so the king rewarded the younger brother generously. This story is not about a court annal or chronicle, so “record” is plainly the appropriate translation for ji here.Footnote 19 For the compilers of the Lüshi chunqiu, then, ji referred to a physical text, stored somewhere at a royal court, that contained necessary information about “past events and their outcomes” that could help to guide action in the present or future.Footnote 20

Whether understood as “annals” or “records,” the above stories characterize ji as texts providing information about historical events and precedents. This same understanding of ji, separate from any real or imagined relationship with royal courts and archives, is found in the few Zhanguo, Qin, and Western Han texts that mention “old records.” Elsewhere the Lüshi chunqiu, for instance, refers to a “record of high antiquity” (shang gu ji 上古記),Footnote 21 while the Xin shu 新書 advises us, “teach the old records to understand what leads to failure or success and so be on guard with dread (教之故記,使知廢興者而戒懼焉).Footnote 22 Meanwhile, the Zhuangzi 莊子 (late third or early second century b.c.e.?) quotes simply a “record” (ji) that has no clear relationship to historical knowledge, since it predicts that the myriad things will be completed after “penetrating the One” (tong yu yi 通於一).Footnote 23 Evidently, ji could thus refer to any other text that offered authoritative knowledge, not necessarily knowledge imputed to the distant past. Of course, many other texts called by different terms were cited for the same purpose, with resort to old wisdom books common enough to be parodied in the Zhuangzi.Footnote 24 While many questions remain unanswered and probably unanswerable, barring a major archaeological discovery, for now we can say that most pre-imperial texts rarely use the word ji and it almost never means “letter” or “note.”

Quite the opposite is true when we turn to received Han texts, which teem with references to a myriad ji.Footnote 25 Some of the best-known examples come in the catalogue of texts recorded in the Han shu “Yi wen zhi” 藝文志 (Treatise on Arts and Letters), where we find numerous titles, most of them now lost, employing ji under different headings. We wonder, for instance, about the contents of Tu shu mi ji 圖書祕記 (Palace Records on Charts and Texts).Footnote 26 Based on their titles, some of these ji, if not all, provided explanations of, or were at least associated with, an original or larger text. Thus we read of a Qi za ji 齊雜記 (Miscellaneous Records on the Qi [Odes]),Footnote 27 the Gongyang za ji 公羊雜記 (Miscellaneous Records on the Gongyang [Tradition for the Chun qiu]),Footnote 28 and the lengthy ritual text in 131 pian 篇 entitled simply Ji (Records).Footnote 29 Two texts on the wu xing under the Shang shu (Documents) category contain the term “traditions and records” (zhuan ji 傳記).Footnote 30 Meanwhile, the “Yi wen zhi” seems to distinguish “records” (ji) texts from other texts called nian ji 年紀 (chronicles).Footnote 31

While bibliographic categories are at best only tangentially related to the social practices of texts,Footnote 32 it is tempting to ascribe this broadening connotation of ji to a developing practice of writing commentaries or proto-commentaries for authoritative texts. The category of ji was never entirely stable, however, and cannot be reduced to merely an explanatory commentary on a text.Footnote 33 The discovery at Wuwei 武威 of a Western Han manuscript version of the Yili 儀禮 undermines neat narratives. While the received Yili contains sections at the end of several chapters marked ji that provide supplementary explanations for information supplied in the chapters, its excavated counterpart includes those sections in their respective chapters without labeling them as ji.Footnote 34 This evidence shows there was no hard and fast distinction between, on the one hand, explanatory “notes” to older authoritative texts, and the texts themselves. Returning to the earlier examples drawn from the “Yi wen zhi,” where the word ji appears in the text titles, it seems best to use “record” to render the word, since that translation does not necessarily imply a subservient relationship between the ji and other texts. If this impulse is correct, we must broaden our search if we wish to explore the trajectory by which ji assumed broader connotations during the Han, becoming “letter” or “note.”

Notes and Letters: Excavated Manuscripts and Ji in Administrative Practice

However scant the evidence from the received texts, it seems undeniable that, over time, ji began to encompass more kinds of writing in different registers. An enormous corpus of excavated administrative documents, spanning the entire early imperial period from Qin to Eastern Han, affords new perspectives and evidence for such a shift.Footnote 35 We can begin with the Qin manuscripts recovered from a well near Liye 里耶, in Hunan 湖南 province, less for the information they provide than for what is absent from the material published thus far.Footnote 36 While the Liye corpus attests all sorts of texts circulating at the edges of an expanding Qin empire, from central government orders to reports and requests of various kinds, so far not one published Liye document refers to itself or to other texts as ji.Footnote 37 Of course, that does not mean that the Liye cache contains nothing that we can call “notes” or “letters,” as is evident from the following example:

Document 1

(☐ = character missing or unreadable due to damage; / = blank space separating text on strip)

尉敬敢再拜謁丞公: 校長寬以遣遷陵船徙卒史酉陽=,☐☐船☐元陵, 寬以 船屬酉陽校長徐。

今司空願丞公令吏徒往取之,及以書告酉陽令。事急。敬已遣寬與校長囚吾追求盜者。敢再拜謁之。

I, Commandant Jing, daring to salute repeatedly, deliver the following to Assistant County Magistrate Gong: Constable Kuan used a boat of Qianling County to transport a minor official (zushi) to Youyang County. The Youyang County … boat … Yuanling County, and Kuan entrusted the boat to Constable Xu of Youyang County.

Now, the Director of Works desires Assistant County Magistrate Gong to order an official and convict laborers to get it, and then inform in writing the Magistrate of Youyang County. The matter is pressing. I, Jing, have dispatched Kuan and Constable QiuwuFootnote 38 to pursue the thieves. Daring to salute repeatedly, I deliver this.Footnote 39

As this document is in fragments, some aspects of the exchange remain elusive.Footnote 40 For our purposes, details are less important than two points about the nature of Jing's correspondence with Gong. First, the document clearly addresses a matter of official business (retrieving the missing boat). At the same time, it opens and closes with a phrase gan zai bai 敢再拜 (“daring to salute repeatedly”) that commonly figures in epistolary documents from Qin and Han.Footnote 41 The document thus crosses boundaries between the administrative document and letters of a more private nature.Footnote 42 Second, Jing urges Gong “to inform in writing” (yi shu gao) the magistrate of Youyang, noting that the matter is urgent (shi ji 事急).Footnote 43 Perhaps this explains why Jing seems to have personally delivered the letter. In any case, compared to a formal official document, the Liye letter was written with a hastier hand and focused on a pressing administrative need.Footnote 44

It was the “note” (ji) that often filled this role in daily administration during Western and Eastern Han. Had Jing lived in a later period he might have asked Gong to write a ji instead of a shu.Footnote 45 The following Han examples are not meant to be directly comparable to the Liye letter. The first group, after all, is made up of notes sent by higher-level officials “informing” (gao 告) subordinates,Footnote 46 and generally my discussion aims to highlight the distinct characteristics of each manuscript, without ever implying the creation of typologies or of administrative genres. The examples have been chosen to showcase the complex roles fulfilled by ji in the administration of the two Han dynasties. Note, meanwhile, that only if the published Liye corpus continues not to yield texts entitled ji might we begin to posit a historical change within the textual practices of imperial administration.

Group 1: Ji Sent by Superior Officials to “Inform” (gao) Subordinates

All of the following documents share two characteristics: 1) they are sent by superior officials to “inform” (gao 告) subordinates about an action they are to carry out or, in one case, that has been carried out; and 2) they all self-identify as ji.

Document 2

九月辛巳官告士吏許卿記到持千秋閣單席詣府無以它為解 988A (Recto)

Ninth month, xinsi day. A notification from the company to the officer Xuqing. When this note arrives, take the single-layer mat from the building at Qianqiu squad and go to the bureau of the Yumen commandant.Footnote 47 No other matter can excuse delay.

士吏許卿亭走行 988B (Verso)

The official Xuqing shall travel by the relay stations.Footnote 48

The text on verso would presumably have served as a pass, allowing Xuqing to travel between watchtowers on his way to making the delivery of the mat to the Yumen commandant. Perhaps he also used it as a pass on his return trip, hence the discovery of the document in the Maquanwan cache (and not at the site of the Yumen commandant bureau).Footnote 49

Document 3

四月戊子官告倉亭隧長通成記到馳詣府會夕毋以它為解急☐☐

教 1065A (Recto)

Fourth month, wuzi day. A notification from the company to Tongcheng, leader of Cangting squad: when this note arrives, ride to the bureau of the commandant to meet. Arrive by sunset. No other matter can excuse delay. Urgent …

Instructed.

倉亭隧長周通成在所候長候史馬馳行 / ☐署☐☐令☐

/ 記☐日一☐ 1065B (Verso)

Zhou Tongcheng, head of Cangting squad, is at post. He shall go using a horse of the company head or company shi. [Lower text too fragmented to translate, but note ji 記]Footnote 50

The translation of the text on verso must remain tentative, as the rationale for mentioning both the company head and shi is unclear. If more of the lower text were legible, the translated text would be more comprehensible. Perhaps that lower text, rendered in much smaller graphs, was written by a different party, after Tongcheng arrived at the commandant bureau. The size of the characters on recto and verso are different, but they do not betray obvious differences in handwriting, suggesting that both sides were composed at the same time by the same person. Confusingly, the note somehow ended up back at company headquarters, even though it asks Tongcheng to go to the commandant bureau. Perhaps Tongcheng brought the document back with him as a travel pass of sorts when returning from the bureau.

The sequence by which different portions of the text were written is even more complicated in the document 4. The different underline styles, explained below, indicate my tentative reconstruction of that sequence:

Document 4

☐☐癸卯官告第四候 / 長記到馳詣官會

無以它為解急☐ / [董]雲叩頭唯卿幸為持具簿奉賦[急] 113:12A (Recto)

… guimao day. A notification from the company to the senior officer of the fourth company: when this note arrives then ride to the company to meet. No other matter can excuse a delay. Urgent. [Dong] Yun bows to the floor: to your honor happily I present a complete list of salaries disbursed. [Urgent.]

☐ / ☐☐☐哀憐罰鐵者頃蒙恩叩=頭=

第四候長行者致走 113:12B (Verso)

… sadness, fined in iron. Now receiving your favor, I bow to the floor, bow to the floor.

A runner for the senior officer of the fourth company will deliver it by foot.Footnote 51

In all likelihood, the dashed underline on recto indicates the portion of the text that was written first. It includes the phrase “notification from the company” (guan gao 官告),Footnote 52 followed by orders for the recipient to travel immediately to the company for a meeting. Next came the single underlined text on verso, written by somebody in the fourth company (di si hou 第四候), who ordered the runner to deliver the requested document on foot.Footnote 53 The third stage is seen in the double-underlined text on recto, in which Dong Yun presents the salary list. The fourth and final stage comes in lower verso, marked above with an undulating line. Here I follow Fujita Takao's speculation that this final line was written later, either as a draft for this document or as practice for a different document; certainly it does not sit easily with the rest of the text.Footnote 54 Significant questions remain, and the order of writing given here can only be provisional.Footnote 55 Notably, too, the document seems to show one company “notifying” the head of another company, when typically a superior company office (hou guan 候官) would “notify” subordinates, such as squad heads (sui zhang 隧長). I am not sure why this document does not conform to this pattern.

Document 5

三月辛未府告騂北亭長廣

與俱車十六兩馬三匹⋅人廿八☐ 73EJT23:349A (Recto)

Third month, xinwei day. The bureau of the commandant notifies Guang, head of Xinbei station.

Bestowed equipment: Chariots: 16. Horses (for each?): 3.Footnote 56 ⋅ People: 28.

府記予騂北亭長 73EJT23:349B (Verso)

A note from the bureau of the commandant: give to the head of Xinbei station.Footnote 57

Unlike the notifications discussed above, the intended recipient here is neither a company nor squad (sui), but a station (ting), in this case probably a postal relay station.

In addition to being notifications (gao) that self-identify as ji, the previous four examples share other features. First, all of the documents appear to be comprised of one single strip,Footnote 58 as does document 5, a broken strip whose bottom half is missing. A second common feature supports this determination: all of the documents contain writing on both sides of the strip. Only on the strip in document 4 is it possible to observe definitive differences in handwriting between verso and recto. These shared features, along with the fact that the recto text on documents 2–4 served as a kind of travel pass, all point toward the quick, temporary nature of the note, with the text serving as a mobile possession of the recipient used for a short period of time, allowing for travel along a designated route. Conspicuously, document 5 departs from this pattern, as it seems to have only a delivery address.

Third, the notes all evince larger exchanges or administrative processes. They provide no explanations or justifications: document 2 does not describe why a mat is needed from Qianqiu station, for instance, nor does document 3 tell us why Zhou Tongcheng had to report so quickly to the company. Such information was either already known or best communicated orally. Document 5, meanwhile, offers no rationale for the items it enumerates. It seems to be a kind of list or inventory, drawn up for reasons that the document does not supply. Other strips utilize this same format, including another Juyan document whose title, rendered in larger characters at the top, is “inventory of items for the general” (jiangjun qi ji 將軍器記),Footnote 59 below which appears a list of items in smaller characters. The fact that document 5 may be more of a list than a note might explain why the calligraphy seems more careful than in the previous three examples, if we assume that the items on the list had to be checked off upon receipt.Footnote 60

Group 2: Notes Requesting More Information

The examples in Group 2 show that sometimes the external referent of a note, the object that it requested or described, was not just a person or thing but additional information. The large font ju ye 俱謁 (“deliver in full”) in the transcription of document 6 reflects the comparatively larger size of the two characters on the document itself (see Figure 1):

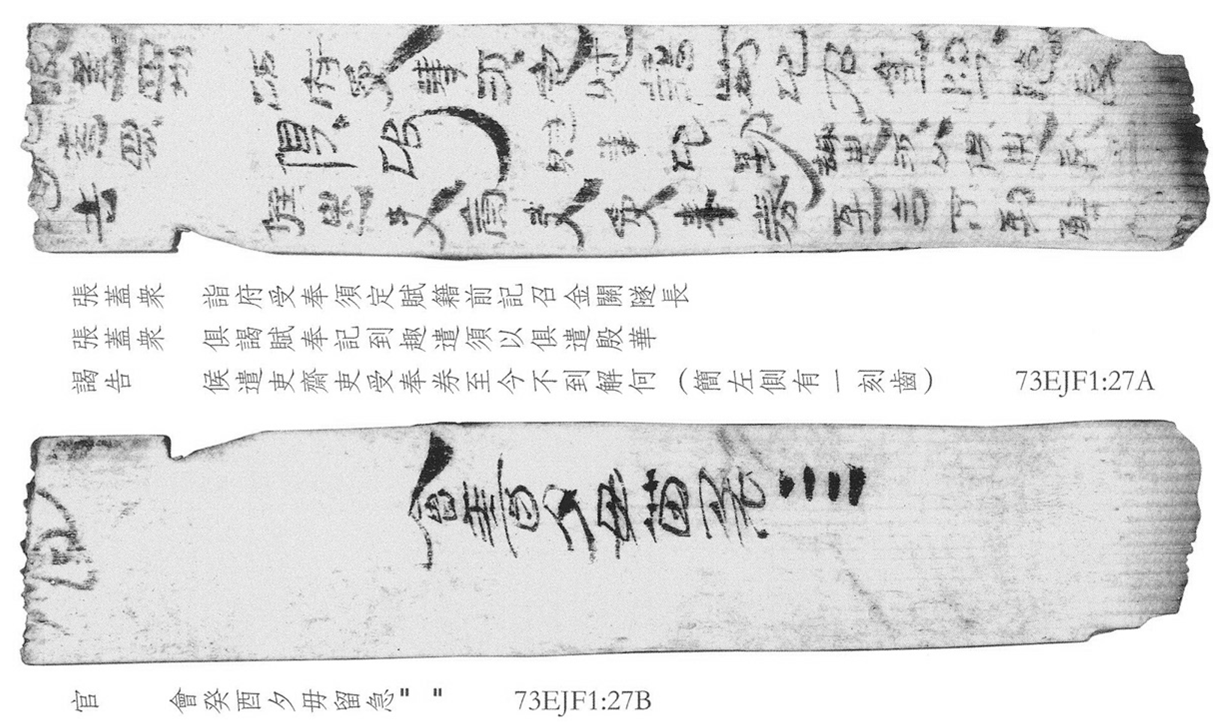

Document 6 (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Jianshui Jinguan, vol. 4, book 2, 280.

張蓋眾 / 詣府受奉須定賦籍前記召金關隧長

張蓋眾 / 俱謁 賦奉記到趣遣須以俱遣殷華

謁告 / 候遣吏齋吏受奉券至今不到解何 73EJF1:27A (Recto)

When opened, hide from crowd Report to the bureau of the commandant and

When opened, hide from crowd present the salary [list]. We must fix the record of

Delivered notification disbursements. Previously a note summoned the Jinguan squad head to DELIVER IN FULL the disbursed salaries. Upon arrival of the note, they were to be gathered up and sent, as required to make [the list] complete. We sent Yinhua and the company sent the officials Zhai and Shou. The salary registers today have still not arrived. What Is the explanation?

官 / 會癸酉夕毋留急 = = 73EJF1:27B (Verso)

To the company. Meet on guiyou day by sunset. Do not tarry. Urgent. Urgent. Urgent.Footnote 61

The translation here can only be tentative. Particularly unclear is the opening statement, zhang gai zhong 張蓋眾, as the phrase is separated by a gap from the text below. Note that there is a notch next to the gap, but on only one side of the strip. Possibly, this notch provided a place for binding the strip with a cord and affixing a seal,Footnote 62 or perhaps the notch allowed the strip to sit in a bag, hiding the sensitive information from view while keeping the top part visible for the convenience of the messenger, who was sent specially by the commandant, apparently. The delay in obtaining the salary registers has caused consternation with the commandant, if the larger font ju ye (“deliver in full”), perhaps the ancient analogue to all caps in an email, is any indication. The role of the Jinguan squadron head remains unclear: is the commandant upset with him, or the company head, or both?

Document 7

六月辛未府告金關嗇 / 夫久前移檄逐辟橐他令史 解事所行蒲封一至今 / 不到解何記到久逐辟詣 183.15A (Recto)

Sixth month, xinwei day. Notification from the bureau of the commandant to Bailiff Jiu. Previously we sent a sealed document stating that you were to pursue and capture the magistrate's official from Tuota named Jie. When the matter was carried out, [you were to report back] in a single sealed envelope. Even today such a document still has not arrived. What is the explanation for this? When this note arrives, you are to pursue and capture him and then go to …

會壬申旦府對狀無以它為解各 / 署記到起時間令可課

告肩水候=官=所移卒責不與都吏趙卿 / 所舉籍不想應解何記到遣吏抵校及將軍未知不將白之 183.15B (Verso)

for a meeting by sunset on the renshen day at the bureau of the commandant, to report back. No other matter can excuse a delay. Each bureau that receives this note is to record the time so that it can be checked. A notification to the Jianshui company: the conscripts transported by Jianshui company do not correspond with the list submitted by the duli Zhaoqing. What is the explanation? When this note arrives send the officer Di to check them. The general does not yet know this. I will not let it be known to him.Footnote 63

In document 7, the precise relationship between the second line on verso (beginning with “A notification to the Jianshui company” [告肩水候官] and continuing to the end) and three other lines (the two lines on recto and the first line on verso) is unclear. The fact that the final four characters of the second verso line are crammed in at the end to allow for an ending flourish on zhi 之 (similar to the ke at the end of the adjacent line) shows a conscious effort made to make sure the entire line fits onto the board.Footnote 64 Perhaps after the initial notification to Jinguan made it back to the commandant, the board was subsequently reused for a second notification to Jianshui.

Documents 6 and 7 differ in form and content from the first group of notes examined above (documents 2–5): not only are documents 6 and 7 longer, but they also do far more than convey simple orders to someone to report to an office. In soliciting additional information, they provide some background to justify their request and to convey its urgency, even if documents 2–5 stipulate some urgency as well. Their formulaic nature notwithstanding, two phrases—“no other matter can excuse a delay” (wu yi ta wei jie 無以它為解) and “How are you to explain [this]?” (he jie 何解)—nearly leap off the strips, as do the triple exhortations of “urgent” (ji 急). The large character ju ye 俱謁 in document 6 highlight the demands of the writer. The closing statement in document 7, meanwhile, suggests some worry connected with the general, perhaps because he might discover discrepancies between the numbers of conscripts listed in the previous submission and the number actually provided.

Group 3: Notes Between Officials and Friends Employing bai 白

While document 7 implies some nervousness on the part of the writer, documents 8–10, in Group 3, show nothing of the sort. Use of the word bai 白 (“to let it be known”) is common in letters from the later Eastern Han and post-Han periodFootnote 65 and, when paired as a compound with ji, bai accompanies documents of a more formal nature, often in official communications.Footnote 66 Document 8 is just such an example, but the later examples become successively more unrelated to professional responsibilities, without ever entirely abandoning the world of work:

Document 8

肩水臨田隧長歸方恢叩頭白記

橐他候長楊卿閤下 73EJD:308 (Recto)

Gui Fanghui, leader of Lintian squad, Jianshui company, bows his head: a note to let it be known:

To the office of Honorable (qing) Yang, head of Tuota companyFootnote 67

As this strip appears to record a location for delivery, presumably Gui Fanghui would have also been carrying the actual note with him for delivery to Yang. The word qing 卿 (literally, “minister,” and so “honorable sir”) is probably a polite form of address, with qing often employed in letters between friends. Whether the note was related to official business or an affair more private in nature remains unclear. If it was official business, then Gui Fanghui was not following the usual chain of command, for he served under Jianshui company, as the address indicates, not Yang's Tuota company.

Document 9

頭良孟今旦聞子侯來也失不以時詣前死=罪=屬自馳詣門下道蓬楊卿舍文君言子侯

73EJD:187A (Recto)

From Touliang Meng: Just this morning I heard that you, Zihou, had arrived. It was my fault that I did not get to visit you in time. Deep apologies, deep apologies. I took my own [horse?] and galloped to your residence, but on the road I passed by Honorable Yang's house and Wenjun said that you, Zihou …

☐☐南☐☐不為☐☐☐下☐得令長☐☐☐叩=頭=謹請文君☐記再拜白 73EJD:187B (Verso)

… south … did not … received, ordering company heads … Bowing my head, bowing my head, with great care I begged Wenjun [to deliver?] this note. Repeatedly bowing, I let it be known.Footnote 68

Many of the characters, especially on the verso side, are indecipherable, so the specific content of this note cannot be understood. What is clear is that Meng proceeds in great haste, as he is dismayed that he just missed seeing Zihou. He thus probably wrote the note immediately after encountering Wenjun, whom he likely has asked to deliver the note on his behalf. Note that this strip was found in the same group as document 9, so the Honorable Yang mentioned in both documents is likely the same person, which would locate this incident in Tuota company.

Document 10

陳惲白少房凡此等事安足已窮子春也叩頭不宜遣使

到子春送焉記告尹長厚叩=頭=君知惲有疾不足少 73EJT4H:5A (Recto)

Chen Hui explaining to Shaofang. How could such trivial matters suffice for me to trouble you, Zichun? I bow my head to the floor. It was not right to dispatch an envoy to Zichun to deliver it to you, so I had my note reported to Yinzhang. I deeply bow my head to the floor, bow my head to the floor. You should know that my sickness is not sufficient to trouble … .

子長子春也前子春來桼人出自己小疾耳立偷也今

客居☐時![]() 也子春又舍金關使幸欲為之官入故敢取 73EJT4H:5B (Verso)

也子春又舍金關使幸欲為之官入故敢取 73EJT4H:5B (Verso)

Zizhang and you, Zichun. Previously when you came to visit me and then left, I was just slightly sick and then got better quickly. Now, with a guest in residence … in time I will get better. Furthermore, Zichun, the fact that you are in Jinguan makes me happy. I hope that when I have reason to go to the company office, I may venture to take [the opportunity to visit?].Footnote 69

My translation is tentative, not only because the language is difficult but also because the hastily written cursive means that the editor's transcription must suffice. Note that this document appears to be following up on a previous “note” that Chen Hui had Yinzhang (the same person as Zizhang?) deliver to Zichun. That the note opens with the phrase “Chen Hui lets it be known” (陳惲白) suggests that it was written just on this one single strip. Nonetheless, as the ending proves somewhat confusing, we cannot discount the possibility that more text once continued onto a second strip (now missing). That said, the final line on the verso seems to head toward a conclusion, since Chen Hui has finished assuring Zichun that his sickness is no problem, and he changes the topic to discuss a future visit to Zichun in Jinguan.

Document 10 is the closest we have come so far to a genuine letter between friends, and it makes perfect sense to refer to it as such, even as a “private letter.” Short and probably quickly written, it aimed to assuage the concerns of a friend worried about the writer's health. The previous document 9 appears to be even more rushed than document 10, as document 9 was written quickly to communicate with a friend he has just missed. In this sense, documents 9 and 10 impress us with the urgency of the notes, even as they clearly display the intimacy of friendship.

Returning to the Capital: A Distressing Letter and Using Notes at Court

Notwithstanding the complexities of interpretation, the foregoing discussion provides some sense of the diverse uses to which ji was put in the militarized frontier regions of the northwest. While questions remain, the previous examples display common features: these notes tend to be brief and sometimes hastily composed and transcribed; often they convey urgent or important information; and, in some cases at least, the notes relay emotions that can range from anxiety to friendliness. It behooves us to keep the foregoing in mind when we encounter ji in other texts, whether excavated or received. Note, for instance, the ji solicited in the following letter (document 11), one of the mid-Western Han manuscripts recovered from Tomb 19 (M19) near Tianchang 天長 in Anhui 安徽 Province. Written on a wooden board, the letter is addressed to an official named Meng 孟 (probably Xie Meng 孟) by a friend or associate named Ben Qie 賁且. The sometimes cryptic nature of the letter renders any translation tentative.Footnote 70

Document 11

賁且伏地再拜請

孺子孟馬足下,賁且賴厚德到東郡,幸毋恙。賁且行守丞,上計以十二月壬戌到洛陽,以甲子發。與廣陵長史卿俱囗,以賁且家室事羞辱左右。賁且諸家死有餘罪,毋可者,各自謹而已,家毋可鼓者,且完而已。賁且西,故自亟為所以請謝者,即事復大急,幸遺賁且記,孺子孟通亡桃事,願以遠謹 [M19: 40–10A] 爲故。書不能盡意,幸少留意。志歸至未留東陽,毋使歸大事,寒時幸進酒食。囗囗囗賁且過孟故縣毋綬急,以吏亡劾,毋它事,伏地再拜。孺子孟馬足下 [M19: 40–10B]

I, Ben Qie, convey my best regards and a request

My very dear lad Meng,

Relying on good fortune, I have arrived in Dong commandery, thankfully without incident. Carrying out the duties of assistant to the Governor, I was on my way to deliver accounts to the capital. I reached Luoyang on the Renxu day in the twelfth month. On the [auspicious] Jiazi day, I left.Footnote 71 WithFootnote 72 the senior official from Guangling, we together .… He brought up matters related to my household, in an attempt to humiliate the members of my group.Footnote 73 Members of my own family have committed crimes whose punishment merits death or worse. With respect to forbidden matters, each behaved with perfect circumspection. Because my family could not be implicated,Footnote 74 the matter was momentarily dropped and that was the end of it.

I am traveling west. The reason I quickly make this request is because the matter has become increasingly urgent. Please send me a note (ji 記).

My dear lad, you have fled the scene, as you prudently wanted to distance yourself. I know that writing cannot fully express intent, but please impart some small sense of it. I plan to return home directly without stopping by Dongyang, lest I bring [news of] this grave matter home with me.

During this cold season, take care to eat and drink … I passed through your old county and there was no pressing business. An official had fled and was under investigation, but nothing else. Conveying best regards, I salute you, my very dear lad Meng.Footnote 75

For the moment, we can set aside the dramatic and evidently stressful incident that prompted Ben Qie to send this letter to Meng. We do not understand what happened to Meng nor the precise nature of his relationship with Ben Qie, but plainly the men were intimate acquaintances, so Ben desperately sought to understand Meng's plans during a tense and perhaps dangerous time. As a result, we can safely assume that the “note” Ben Qie requested would have been private correspondence meant for his eyes only. More important for our purposes, the evident urgency of the situation recalls the quick notes dashed off by commanding officials and, especially, the friends and acquaintances discussed above (e.g., documents 9 and 10). While the difference between “note” and “letter” are subtle, the former does seem more appropriate in this case, especially if Xie Meng had fled, was in straightened circumstances, and could not write a full-fledged explanation of his whereabouts. In this sense, Ben Qie's use of the stock phrase “writing cannot fully convey intent” (shu bu neng jin yi 書不能盡意) seems particularly apt, since it would perhaps have been impossible, even dangerous for Xie Meng to go into great detail.Footnote 76

When we turn to practices evident at the imperial court, the specific meanings attached to ji become even clearer. The Han shu regularly uses various compound terms that match ji with other words in order to refer to different types of documents exchanged between friends or associates, without ever straying too far from administrative matters. The case of zou ji 奏記 (“presented note”) is perhaps the most enlightening, since it contrasts rather clearly with zou shu 奏書 (“presented document”).Footnote 77 Neither of the terms appears very frequently, but compared to the former, the latter is more formal, for, with one exception, it is always submitted to the ruler (or empress).Footnote 78 Moreover, the phrase zou shu is usually paired with an additional graph characterizing the purpose of the document: jian 諫 (“to remonstrate”), xie 謝 (“to demur”), or jie (“to warn”).Footnote 79

By contrast, there is no instance of a “presented note” (zou ji) submitted to the ruler. Rather, all of the notes are exchanged between officials, and the writer almost always holds a relatively low office. This pattern would seem to contradict the evidence in the administrative documents from the desert northwest analyzed above, since they suggest a pattern of “notes” sent as brief orders to subordinate officials. Orders, however, could open up opportunities for more intimate exchanges between superior and subordinate. In the Han shu, the recipient of a “presented note” (zou ji) is inevitably a patron, potential patron, or friend of the less powerful person who wrote the note. The case of Zheng Peng's 鄭朋 note to Xiao Wangzhi 蕭望之 (d. 46) is a case in point, since Zheng Peng “secretly desired to attach” (陰欲附) himself to the powerful Chancellor, as the Han shu makes quite clear. After denouncing Xiao's enemies and gaining an appointment at court, Zheng delivered to Xiao a note of praise, embarrassingly fawning, that prompted Xiao to “admit” (na 納) Zheng into his inner circle of advisors.Footnote 80

The compound “writings and notes” (shu ji 書記) is also instructive, even if appears but once in the Shi ji 史記, when describing writing practices in Anxi 安息 (Persia), where the people wrote horizontally on pieces of leather in order to make “writings and notes” (shu ji).Footnote 81 The Han shu includes this same story, but elsewhere uses the term to refer specifically to private correspondence, as when Chunyu Zhang 淳于長 (d. 8 b.c.e.) “exchanged writings and notes” (交通書記) with a somewhat desperate former Empress Xu 許后 (d. 8 b.c.e.), who was bribing Chunyu to speak on her behalf with Chengdi 成帝 (r. 33–7 b.c.e.) after he had demoted her as empress in favor of a beloved consort more likely to bear a child. When their exchanges came to light, Chunyu's “writings” (shu 書) were deemed “perverse and depraved” (bei man 誖謾), and he was dismissed from his post, while the former Empress Xu was forced to commit suicide.Footnote 82

As we can see, the “note” circulated outside of official channels, and was often used in the most intimate contexts, but neither was it completely divorced from the work of government. A final contrast between the zhao shu 詔書 (“edict”) and zhao ji 詔記 (“edict in note form”) makes this distinction clearer still. The former is ubiquitous throughout the Shi ji and Han shu, in all cases indicating an official order or proclamation from the emperor or empress dowager.Footnote 83 The latter, however, appears but once, in a well-known memorial submitted by Xie Guang 解光, at the outset of Aidi's 哀帝 reign (r. 7 b.c.e.–1 c.e.), in which Xie summarized his investigation into the mysterious deaths of two children Chengdi allegedly fathered with a consort and former empress. Xie's investigation implicated Zhao Zhaoyi 趙昭儀, one of Chengdi's most favored consorts and the sister of Zhao Feiyan 趙飛燕, whom Chengdi had installed as empress to replace his Empress Xu.Footnote 84 For our purposes, the politics and intrigue that prompted the investigation are less important than what this one instance reveals about communications within the imperial court. Immediately after the birth of one of the children, for instance, the emperor reportedly sent several “edicts in note form” sealed in silk envelopes, one of which ordered the baby and its mother to be imprisoned. One follow-up order asked the jailkeeper whether the baby had died, and to “handwrite the response on the back of this board” (手書對牘背).Footnote 85

There is some slippage between shu and ji in Xie Guang's report, but nonetheless the story indicates that the term ji, when appended to zhao, implies a quicker, less formal direct communication by the emperor, unmediated by the document drafters who produced the elegant edicts intended for public circulation.Footnote 86 The conflict within the palace and between the emperor's various consorts was not mediated through or driven by an “edict,” but rather through a veritable stream of ji issued from the emperor's chambers by personal messengers. Nonetheless, as Xie Guang took pains to point out, these ji were sealed by officials and resulted in a series of actions executed on the emperor's behalf. On the one hand, this interplay between private, intimate exchanges and official documents is not particularly surprising in the case of the emperor, since it is hard to imagine any piece ascribed to him that was not examined or at least delivered by an attendant of one kind or another. At the same time, we already saw a somewhat analogous (if not “the same”) dynamic play out at the lowest administrative levels. The request to write on the back of the board is fully in keeping with the excavated ji described above, all with writing on both sides, in some cases in multiple hands. Moreover, many of the ji were part of larger exchanges of documents and information, one link in a complicated web of urgent requests. Administrative practice, whether at court or in the frontiers, required a certain number of affective, casual, and rushed communications, and the “note” emerged to fill that need.

Final Notes to Remember

In highlighting the ubiquity of notes in Han administrative and literary practice, this essay makes no argument that “notes” and “letters” did not exist during Qin or pre-Qin times. Such an absurd claim is demonstrably false, since the Qin document from commandant Jing (Document 1) is a “letter,” by any definition, albeit one addressing official business. This essay makes more modest claims, calling attention to two facts that emerge from sifting through the available evidence. First, on the whole, pre-imperial sources simply do not refer to ji often. On those rare occasions when the word appears, it tends to invoke annals or records associated with royal courts or, more broadly, any kind of old record that contains authoritative knowledge, often about the distant past. By contrast, received Han sources teem with all sorts of ji, and not just “annals” or “records.” Thus, judging by the evidence at hand, the word by Western Han became more common and broadened by usage; if the published Liye material continues do not yield any manuscripts that self-identify as ji, the case for dating this change to the Western Han itself will be stronger, though not beyond a reasonable doubt, for we cannot assume that the Liye material is “representative” of Qin practices throughout the Qin kingdom and Qin empire.

Second, close examination of excavated sources from the northwest illustrates the implications of choosing “note” or “letter” as translation for ji. Translation decisions can only be made on an individual, case-by-case basis. Still, as the examples above suggest, “note” seems preferable when the document is hastily written, or in a perceived crisis (ji 急). Brevity and swift delivery were then primary concerns, with the ji helping to facilitate the quick exchange of information or resolve misunderstandings. Such patterns in the manuscript evidence also figure in the anecdotes alleging ji exchanged at the imperial court. Particularly striking in this regard is the parallel between the translated ji manuscripts cited here, which have multiple hands writing on both sides of the document, and the Han shu story about the jailkeeper asking the recipient of the “edict in note form” (zhao ji) to write a response on the back of the board.

This spontaneous and occasional nature of so many excavated ji thus places today's readers at the heart of the Han administration. Study of the history of institutional structure and official positions (zhidu shi 制度史 in Chinese scholarship) is critically important. This essay could not have been written without the assistance of studies such as Records of Han Administration, along with numerous other books and essays by Michael Loewe. At the same time, the evidence cited above shows us that close study of manuscript sources, always somewhat fraught, also helps us understand Loewe's “operations of government” better. So many of the excavated “notes” are manifestly not manuscripts that existed on more or less independent terms—unlike an imperial edict, say, or a summary report of an investigation. Rather, they reflect individual moments in complicated webs of exchange, where small bits of information needed to be communicated efficiently.

Given the number of newly published excavated manuscripts, significant research remains to be done on the precise dynamics and rhetorical patterns found in such texts, including the striking similarities between the roles played by ji in efficiently recording and conveying information, often of an urgent nature, and the “memorandum” favored in modern bureaucracies. The memo, like the Han “note,” is often marked up with handwritten reactions and follow-up requests,Footnote 87 and the word's obvious connection to “memorize” cannot but evoke the fact that in Chinese ji also came to mean “to remember.” Perhaps this slippage between the “note” and “remembering” began to emerge during the Han, though this supposition is pure speculation. The connection between the two is nonetheless beautifully evoked in an anecdote from the Liezi 列子 (c. third century c.e.?) which explicitly puns on the double meaning of ji as “to remember” and “to note down.” The story describes one Huazi 華子, a man who “in his middle age fell sick with forgetfulness” (中年病忘). For years, this man suffered from a dementia so severe that he forgot to walk and sit down. Through an unnamed, mysterious means, a classical master (ru sheng 儒生) from Lu 魯 managed to cure him, so at dawn one day Huazi's dementia lifted and he became fully “conscious” (wu 悟). Furious, he lashed out at his wife and son and chased away the classical master with a dagger-axe. His neighbors asked about the strange behavior:

華子曰:「曩吾忘也,蕩蕩然不覺天地之有无。今頓識既往,數十年來存亡、得失、哀樂、好惡,擾擾萬緒起矣。吾恐將來之存亡、得失、哀樂、好惡之亂吾心如此也,須臾之忘,可復得乎?」

子貢聞而怪之,以告孔子。孔子曰:「此非汝所及乎!」顧謂顏回記之。

Huazi said: “In the past, I forgot. Just bobbing along, I did not know whether or not heaven and earth even existed. Now suddenly I have realized what has happened over the last few decades. In jumbled disorder, there rose up the countless strands of what has been preserved and lost, succeeded and failed, the sorrows and pleasures, and likes and dislikes. I am now terrified by the future havoc that may be wrought by instances of preservation and loss, success and failure, sorrow and pleasure, and likes and dislikes. Just one instant of forgetting: how can I ever get that back again?”

Zigong heard about the incident and found it strange, so he related the story to Kongzi, who then said, “How could you be up to understanding it?” He then turned and told Yan Hui to note (ji) the story down.Footnote 88

The anecdote memorably juxtaposes the forgetfulness of the man, and the relief such forgetfulness brings, with the need to “remember” or “note” in written form (ji) his story. Presumably, a record of the story would allow Kongzi, Yan Hui, and others to refer to and learn from it in the future, but underlying is the unstated question: do such acts of noting and remembering contribute to the kind of pain and anxiety Huazi experienced? The Liezi invites us to ponder the potential contradictions, even dangers, of a world filled with the early equivalent of Post-Its, in which we always have a brush (or pen or phone) at the ready when something noteworthy comes up.