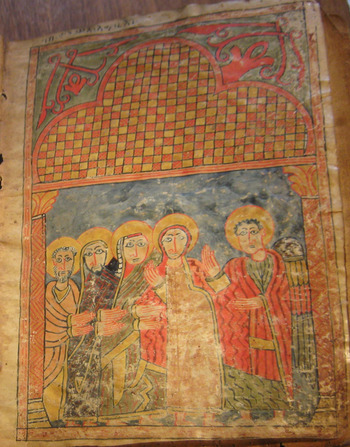

Christian Ethiopian iconography shows us several representations of the Resurrection of Christ. In accordance with the scriptures, in which the event is not described, the iconography of the Resurrection in fourteenth-century Ethiopian art does not present the moment when Christ was raised from the dead. Instead, Christ's triumph over death is evoked by two episodes that took place after the Resurrection: the encounter of the Holy Women with the Angel at the Tomb;Footnote 2 and the appearance of Christ, accompanied by an angel, to Mary Magdalene, John and Peter (see Figure 1).Footnote 3 Both scenes are attested in fourteenth-century Ethiopian manuscripts and, to judge by the surviving evidence, the theme of the Appearance of Christ to Mary Magdalene and the two Apostles was used almost as frequently as that of the Holy Women at the Tomb.Footnote 4

Figure 1. Christ Appears to Mary Magdalene, John, and Peter, late fourteenth century, ink and pigments on parchment. London, private collection, fol. 17r.

(Photo: the author)

By the end of the fourteenth century the descent of Christ into Hell, or Siʾol as it is called in Ge'ez, was also used by Ethiopian artists to symbolize the Resurrection.Footnote 5 In this respect, it is worth noting that a wall painting from the late twelfth- or thirteenth-century church of Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos (Figure 2), near Lalibäla, has been interpreted as an earlier example of this theme (Chojnacki Reference Chojnacki2009: 24; Balicka-Witakowska and Gervers Reference Balicka-Witakowska and Gervers2001: 34). The painting in question, however, is more likely to be a representation of Doubting Thomas (John 20: 24–9).Footnote 6 Such a conclusion is supported by two observations. First, because the three scenes that precede the painting in question, starting from the left, are the Crucifixion, the Holy Women at the Tomb, and the Noli Me Tangere, it is evident that the narrative of this cycle of paintings unfolds from left to right. Thus, it would be more logical to interpret the last scene of the cycle as a depiction of an episode that took place after these three events, such as the Doubting Thomas, rather than before them, as the Descent into Hell. Second, the figure whose arm Christ holds, a gesture that has been interpreted by some as the Pulling of Adam from Hell, lifts one finger to Christ's side. This seems a clear depiction of the narrative found in the Gospel of John, in which an unbelieving Thomas places his finger in Christ's wound.Footnote 7

If we accept that the last scene in the cycle of paintings in Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos represents the Doubting Thomas rather than the Descent into Hell, then the representation of the Holy Women at the Tomb that precedes it (Figure 2) is not only the oldest known example of this particular theme in Ethiopian painting, but also the earliest known representation of the Resurrection. In fact, although it is asserted that painting was practised in Ethiopia prior to the twelfth century (Mercier Reference Mercier2000a: 35–45; Lepage Reference Lepage1977), there is little evidence to reconstruct the genesis of this theme in Ethiopian art. Unfortunately, because of a lack of examples, it is equally difficult to track the evolution of this motif during the thirteenth century, and it is only between the end of the thirteenth and the beginning of the fourteenth centuries that it is possible to offer a more detailed picture.

Figure 2. Crucifixion without Christ, Holy Women at the Tomb, Noli Me Tangere, and the Doubting Thomas, late twelfth or early thirteenth century, fresco. Lasta, Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos Church (Photo: Michael Gervers and Ewa Balicka-Witakowska)

In fourteenth-century Ethiopian manuscript illumination the theme of the Holy Women at the Tomb appears in two forms. In the first (Type I), two or three Holy Women proceed from the left towards the empty Tomb in the centre, one angel is seated to the right of the structure, and two or three guards lie below it (Figures 3–5). In the second form (Type II), two Holy Women, one placed to the left of the scene and the other to the right, converge towards Christ's Tomb in the centre; the angel sits in front of it, and two guards are depicted below it (Figures 6–10, 13). These two forms have several points in common. In both, the empty tomb is the primary visible sign of the Resurrection, and there is only one angel, in accordance with the Gospels of Matthew (28: 2) and Mark (16: 5), rather than two as in Luke (24: 4) and John (20: 12). Likewise, in both types the diminished size of the guards – who may be represented in profile to emphasize the fact that they are not Christian (Staude Reference Staude1934; Chojnacki Reference Chojnacki1985: 584) – indicates their lesser importance. Other similarities could be noted, but the point here is that, at first, the two forms appear to be differentiated chiefly by the position of the Holy Women in relation to the tomb: in Type I they proceed from the same direction, whereas in Type II they converge from opposite directions towards the centre. However, a closer examination reveals that there are other important differences between these two forms. In Type I the visit of the Holy Women at the Tomb takes place outdoors. In Type II the presence of a domed structure above the tomb of Christ sets the scene indoors. Thus, as discussed below, Type I remains more faithful to the gospel account of the Resurrection, while Type II presents a more complex image with several layers of meaning. In order to define these differences further, it is necessary to discuss Types I and II separately and in greater detail.

Figure 3. Holy Women at the Tomb, second half of the fourteenth century, ink and pigments on parchment. Lake Tana, Kəbran Church, fol. 19 v. (Photo: Emmanuel Fritsch)

Figure 4. Holy Women at the Tomb, late fourteenth or early fifteenth century, ink and pigments on parchment. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, fol. 6r. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Figure 5. Holy Women at the Tomb, turn of the fifteenth century, ink and pigments on parchment. Wällo, Gəšän Amba, Maryam Church, fol. ? (Photo: © Diana Spencer, courtesy of the deeds project)

Type I is attested in several Ethiopian illuminated Gospel books. It is found, for instance, in the Kəbran Gospels (Figure 3), which have been dated to the second half of the fourteenth century (Bosc-Tiessé Reference Bosc-Tiessé2008: 35–7; Heldman Reference Heldman and Hess1979a);Footnote 8 in the Gospels of the Metropolitan Museum (Figure 4), which probably belong to the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century (Gnisci Reference Gnisci2014: 205–7; Lepage and Mercier Reference Lepage and Mercier2012b);Footnote 9 and in the Gəšän Maryam Gospels (Figure 5), which have been associated by Heldman (Reference Heldman1994: 104) with the scriptorium of the Ethiopian Nəgus Dawit (r. 1380–1412).Footnote 10 These three examples have all been dated to a period between the end of the fourteenth and the early fifteenth century. However, considering that the interpretation of the theme of the Holy Women at the Sepulchre in these works corresponds, roughly, to that found in the late twelfth- or early thirteenth-century fresco from Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos mentioned above, it is possible to date the evolution of Type I in Ethiopia at least to this period.

In Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos (Figure 2) the two Holy Women proceed towards an angel seated in front of a small domed structure that represents Christ's Tomb. The angel points upwards, witnessing to Christ's rising, whereas the women are depicted with their hands raised in prayer, in a manner that recalls the seventh-century Chairete icon discovered by Weitzmann (Reference Weitzmann1976: no. B.27) on Mt Sinai, or the mosaic of the Women at the Tomb from S. Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna.Footnote 11 As for its composition, the scene is reminiscent of that found, for instance, in the Rabbula Gospels, in which an angel is placed between the women and the Tomb, instead of behind it, as in most sixth-century versions of the theme.Footnote 12 As is often the case with representations of the Holy Women at the Tomb in Christian art, the domed structure in the painting is evidently an anachronistic depiction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, built by Constantine I (r. 306–337) and modified across the centuries, rather than of the tomb of Christ as it would have been seen by the Holy Women.Footnote 13

Although the interpretation of the theme of the Holy Women at the Tomb in fourteenth-century Ethiopian illumination echoes that of Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos, there are some discrepancies which need to be examined. First, in the manuscripts, the angel is placed behind the tomb (Figures 3–5). Second, in Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos the angel points upwards with his right hand and holds a cross-staff in his left, whereas in the manuscripts he points towards the empty tomb with his right hand and, in some of the examples, holds one of the pieces of the cloth that covered Christ's body (Luke 24: 12; John 20: 6–7) in his left hand (Figures 4–5). Third, while the guards (Matthew 28: 4) are not depicted in the wall painting, they appear in the manuscripts, though their number, as well as that of the Holy Women, varies from two to three. Lastly, in Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos the Tomb appears to be a reproduction of the outer structure of the Anastasis Rotunda – it recalls, for instance, the architecture seen in an eleventh-century Ottonian ivory carving now in the collections of The British Museum.Footnote 14 In the manuscripts, instead, the structure reproduces a section of the aedicule placed within the Anastasis Rotunda, which can be identified as the entrance to Christ's tomb.

In the Metropolitan Museum and in the Gəšän Maryam Gospels a rectangular shaped element cuts diagonally across the arched entrance to Christ's tomb (Figures 4–5). This is a representation of the so-called Angel's Stone, that is to say the stone that was rolled away from the entrance of Christ's tomb in the morning of the Resurrection, and that was placed as a relic in the porch of the Tomb during the fourth century (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2002: 83, 118). According to the sixth-century account of the Piacenza pilgrim, the stone “which closed the Tomb is in front of the tomb door and is made of the same coloured rock as the rock hewn from Golgotha”.Footnote 15 A similar rendition of the Stone can be seen in the aforementioned mosaic of the Holy Women at the Tomb in the basilica of S. Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna. In the Kəbran Gospels the Tomb is represented as a sarcophagus (Figure 3). Above it is a representation of the baldachin which was placed over the structure of the Tomb. A similar structure can already be seen on some of the ampullae from Monza and Bobbio, as well as on the sixth-century Sancta Sanctorum panel from the Vatican.Footnote 16 However, stylistically the rendition of the baldachin in the Kəbran Gospels finds closer parallels in later Byzantine art.Footnote 17 For instance, the baldachin in the eleventh-century fresco of the Holy Women at the Sepulchre in S. Angelo in Formis has many points in common with the Ethiopian version of the same subject.Footnote 18 In fact, it is quite possible that the illuminator who depicted the Holy Women in the Kəbran Gospels had a Byzantine model in mind, as it has been observed that other illuminations of this manuscript betray Byzantine influences (Heldman Reference Heldman and Hess1979a).

The Metropolitan Museum and Gəšän Maryam Gospels have other points in common. In both examples one lamp hangs from the entrance to Christ's tomb. This is the lamp that hung at the entrance to Christ's tomb in Jerusalem (Bertoniere Reference Bertoniere1972: 31–2), and which was described by the Piacenza pilgrim in the sixth century as a “bronze lamp” placed “where the Lord's body was laid”.Footnote 19 In this context the lamp symbolizes the Resurrection as well as the presence of God (1 John 1: 5).Footnote 20 In the Kəbran Gospels three lamps instead of one hang from the Tomb. These lamps may reproduce those that hung from the outer structure of the Tomb in the Holy Sepulchre, but the number three also has symbolic value as it represents the number of days Christ spent in the Tomb.Footnote 21 More generally, the presence of lamps in Type I is particularly appropriate as the lighting of candles and lamps, as part of the Lucernarium, marked the beginning of the Paschal Vigil at the Holy Sepulchre as early as the fourth or fifth century (Bertoniere Reference Bertoniere1972: 22–58). In this respect, it is worth noting that, for Sergew Hable Sellassie (Reference Sellassie1972: 143), the Ethiopians were “entrusted with the custody of the light which burns continuously on the tomb of the Lord” as early as the fifth century, and that there is evidence that by the fourteenth century Ethiopians attached considerable importance to the ceremony of the Holy Fire in Jerusalem (Fiaccadori Reference Fiaccadori and Böll2004; Cerulli Reference Cerulli1943b: 131–5). Furthermore, the Ethiopian Church is among those that still employ the ancient hymn Phos Hilaron for the evening services (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson, Eastmond and James2003: 112).

The presence of architectural elements inspired by the Anastasis in Jerusalem in Type I is not surprising. Jerusalem has remained throughout the centuries the most sacred place of pilgrimage for Ethiopians, and the ties between Jerusalem and Ethiopia are ancient (Pedersen Reference Pedersen and Uhlig2007: 27–7; Grierson Reference Grierson and Grierson1993: 5–17; Sergew Hable Sellassie Reference Sellassie1972: 34–44, 110, 112). There is the Old Testament episode of the Queen of Sheba and Solomon (1 Kings 10: 1–13), reworked into the text known as Kәbrä Nägäst (The Glory of Kings).Footnote 22 This work was used by members of the Solomonic dynasty, who had seized power in 1270, as a means to claim direct descent from Solomon (Henze Reference Henze2000: 56–60; Taddesse Tamrat Reference Tamrat1972: 50).Footnote 23 Moreover, according to Acts (8: 26–40) the Ethiopian eunuch converted by Philip had gone to Jerusalem to worship. Then, during Late Antiquity, Christian Ethiopian rulers took an interest in Jerusalem. For instance, according to tradition, the Aksumite ruler Kaleb (r. 514–543) sent his crown there to be placed above the Holy Sepulchre (Henze Reference Henze2000: 41; Sergew Hable Sellassie Reference Sellassie1972: 143). Ethiopian pilgrims also risked their lives to reach Jerusalem, and when Saladin (r. 1174–93) captured it in 1189 he is said to have shown favour to the Ethiopians present there (Taddesse Tamrat Reference Tamrat1972: 129; Cerulli Reference Cerulli1943a: 33–7). It may not be a coincidence that the first known depiction of the Holy Sepulchre in Ethiopian art is found in Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos, a church traditionally considered a foundation of the Ethiopian king and saint Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos (r. 1132–72) who, according to local traditions,Footnote 24 lived for some time in Jerusalem, married a Levite woman, and acquired precious building materials for the church from Saladin (Marrassini Reference Marrassini, Uhlig, Bausi and Uhlig2014: 53–4). Lastly, according to Taddesse Tamrat (Reference Tamrat1972: 58–9), the number of Ethiopian pilgrims going to Jerusalem increased significantly during the twelfth century, though the earliest Ethiopian documents attesting the presence of Ethiopians in the city date to the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries (Cerulli Reference Cerulli1943a: 88–90, 130).

Of even greater relevance to this study is the foundation of churches in Ethiopia that imitated the loca sancta in Jerusalem. Heldman (Reference Heldman1992: 225–9), for instance, has convincingly argued that the Church of Maryam Ṣəyon, possibly founded in the sixth century by Kaleb in Aksum, was conceived as a copy of the Church of Sion in Jerusalem. These constructions were not necessarily faithful replicas of the originals, but (as noted by Krautheimer Reference Krautheimer1942) in the medieval conception of architecture fidelity to the original model was not a requirement, and one church could copy another, for instance, merely by imitating its dedication: what mattered was transferring the symbolic dimension of the structure. In this respect, scholars believe that Lalibäla, a site which includes eleven rock-hewn churches, built roughly between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, was intended as a recreation of Jerusalem (Lepage and Mercier Reference Lepage and Mercier2012a; Heldman Reference Heldman1995; Reference Heldman1992: 229–32; Gerster Reference Gerster1970: 88–91). It is noteworthy that one of Lalibäla's churches, which is named after Golgotha, contains a tomb which, as Alvares reported in the sixteenth century, was made “like the sepulchre of Christ in Jerusalem”.Footnote 25 According to Gervers (Reference Gervers2003: 45): “the dedication of the Church of Golgotha in Lalibäla to the memory of Christ's Crucifixion and burial in a rock-cut tomb on the Golgotha hill in Jerusalem makes this site a symbolic representation of the aedicule of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem”. Therefore in Lalibäla, just as in Jerusalem, Golgotha and the Holy Sepulchre are part of the same complex and, in this respect, it may be possible to draw an additional parallel with Ethiopian manuscript illumination of the fourteenth century, in which the theme of the Holy Women at the Sepulchre is usually juxtaposed with that of the Crucifixion (Figure 6) (Balicka-Witakowska Reference Balicka-Witakowska and Uhlig2005: 859; Heldman Reference Heldman1979b).

Figure 6. Crucifixion, Holy Women at the Tomb, first half of the fourteenth century, ink and pigments on parchment. Däbrä Ma‛ar, fol. 11 r. (Photo: Michael Gervers)

From the above, it is evident that Ethiopian artists were, at least to some extent, familiar with the sacred geography of Jerusalem. And, in this respect, it should be pointed out that more than one author has suggested that the theme of the Crucifixion without the body of the Crucified, a motif encountered in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Ethiopian art, incorporates elements inspired by Golgotha (Gnisci Reference Gnisci2014: 195; Mercier Reference Mercier2000b: 44–5; Balicka-Witakowska Reference Balicka-Witakowska1997: 115–8; Heldman Reference Heldman1979b). As for why sections of the Holy Sepulchre are reproduced in Ethiopian illumination of this period, alongside the influence of foreign models, it is possible that Ethiopian artists wanted to reproduce what Wilkinson (Reference Wilkinson, Eastmond and James2003: 112) calls the “iconic values” of the Tomb of Christ in Jerusalem. For Wilkinson, the Tomb of Christ was valued, on the one hand, as “the literal place of the Resurrection” and, on the other, as the “holy of holies”, that is, as the new sanctuary of the now Christianized Jerusalem (2003: 112). The Ethiopian Church currently celebrates the consecration of the Holy Sepulchre on Mäskäräm 16 (September 26). (See Fritsch Reference Fritsch1999: 106).

Type II is attested in a greater number of Gospel books than Type I. The examples examined here are found in: the Gospels of Däbrä Ma‛ar (Figure 6), which have been dated to 1340–41 on the basis of a colophon and a donation note (Heldman and Devens Reference Heldman and Devens2005);Footnote 26 the Gospels from the monastery of Däbrä Maryam Qʷäḥayn, dated, on the basis of a colophon, to 1360–61 (Balicka-Witakowska Reference Balicka-Witakowska1997: 127–8; Bausi Reference Bausi1994: 24–44);Footnote 27 the Gospels of The Walters Art Museum (Figure 7), which present some affinities with Däbrä Ma‛ar and can be dated approximately to the mid-fourteenth century (Mann Reference Mann and Horowitz2001: Cat. 10);Footnote 28 a Gospel fragment in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm (Figure 8), dated by Heldman (Reference Heldman1979b: 108), on the basis of its style, to the first half of the fourteenth century;Footnote 29 the Gospels of Däbrä Ṣärabi (Figure 9), dated by Gervers (Reference Gervers and Nosnitsin2013: 56) to the fourteenth century;Footnote 30 the recently discovered Gospels of Däbrä Sahəl (Figure 13);Footnote 31 a manuscript from a private collection dated by Mercier (Reference Mercier2000b: 44–5) to the first half of the fourteenth century;Footnote 32 and the Gospels now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Figure 10) dated to the second half of the fourteenth century (Balicka-Witakowska 1997: 125; Lepage 1987: 159; Heldman 1979b: 110).Footnote 33

Figure 7. Holy Women at the Tomb, fourteenth century, ink and pigments on parchment. Baltimore, The Walters Art Museum, W.836, fol. 7r. (Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore)

Figure 8. Holy Women at the Tomb, fourteenth century, ink and pigments on parchment. Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, B 2034, fol. ? (Photo: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm)

Figure 9. Holy Women at the Tomb, Däbrä Ṣärabi, fourteenth century (?), fol. 11r. (Photo: Michael Gervers)

Figure 10. Holy Women at the Tomb, fourteenth century, ink and pigments on parchment. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, éth. 32, fol. 8 r.

Unlike Type I, in Type II the number of both the Guards and the Holy Women is fixed at two. The Holy Women advance towards the tomb, placed in the centre, from opposite sides, holding a censer in their right hand and raising their left hand to their chest.Footnote 34 Their gestures recall those seen in interpretations of the theme in early Christian art, as shown, for instance, by a seventh-century ampulla in the Dumbarton Oaks collection,Footnote 35 and by a sixth-century pyxis now in the Metropolitan Museum (Figure 11).Footnote 36 Indeed, Type II has a number of points in common with the interpretation of the Holy Women at the Tomb found in many early Christian examples, and, in light of these similarities, Heldman (Reference Heldman1979b), Lepage (Reference Lepage1987; Reference Lepage1990), and Fiaccadori (Reference Fiaccadori2003), among others, have suggested that the iconography of Type II derives from a now lost Christian prototype, possibly Palestinian, of the sixth or seventh century.

Figure 11. Holy Women at the Tomb, sixth century, ivory. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.190.57a, b. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In Type II the angel is always placed in the centre of the composition, but his gestures vary and may be divided into two categories: in the first (Figures 6–9), he blesses or points upwards with his right hand whilst resting a staff-cross on his left shoulder (Type II-A);Footnote 37 whereas in the second (Figure 10), he points downwards with his right hand and raises a circular object in his left (Type II-B).Footnote 38 The architectural framework also varies: in Type II-A, the angel is seated under a dome supported by two columns; whereas in Type II-B there is a smaller structure placed under the dome. It is evident that the iconography of Type II has been influenced, like that of Type I, by the architecture of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. For instance, the large dome under which the scene takes place, as Heldman (Reference Heldman1979b: 114) and Lepage (Reference Lepage1987: 170–1) have observed, replicates the one built over the Anastasis Rotunda. However, in Type II there is an additional conflation of elements, because the Visit of the Holy Women takes place within a space that can also be interpreted as a sanctuary of an Ethiopian church.

Traditionally in Ethiopian churches the area of the sanctuary – the Holy of Holies generally referred to as mäqdäs – can be accessed only by priests and deacons (Appleyard Reference Appleyard and Parry2007: 134; Fritsch Reference Fritsch and Uhlig2007b: 765–7; Archbishop Yesehaq Reference Yesehaq1997: 150), and is shielded from public view by a curtain known as mägaräǧa (Fritsch Reference Fritsch and Uhlig2007a: 629–31). The mäqdäs houses the tabot, more appropriately referred to as mänbärä tabot, a replica of the Ark of the Covenant, which, according to the tradition of the Ethiopian Church, is kept in the church of Mary at Aksum (Fritsch Reference Fritsch, Uhlig and Bausi2010: 804–7; Appleyard Reference Appleyard and Parry2007: 134). Within the tabot, is the ṣəllat, also referred to as tabot,Footnote 39 which replicates the tablets that Moses received on Mt Sinai (Getatchew Haile Reference Haile and Horowitz2001: 38). Without the ṣəllat a church cannot be consecrated (Heldman Reference Heldman, Uhlig and Bausi2010: 802). Interestingly, in Type II-A, just as in Ethiopian churches, the area of the Sepulchre – that is to say the burial chamber where Christ's body had rested, rather than the small aedicule surrounding it – is concealed by a curtain that hangs from a rod suspended between two columns (Figures 6, 8).Footnote 40 Because of this Christ's burial chamber is not visible. The parallel is clear: just as the mäqdäs of Ethiopian churches is shielded from view by the mägaräǧa because of its sanctity, so is the Sepulchre of Christ concealed by a curtain in Type II-A.Footnote 41

In this respect, it must be noted that the rock on which the angel is seated in Type II-A is not Christ's Sepulchre, as suggested by Ernst (Reference Ernst2009: 162), but the stone on which the angel sat. A similar rendition of the stone, represented as a quadrangular block, is attested in Byzantine and medieval iconography, as can be seen in the aforementioned fresco in S. Angelo in Formis, or in the twelfth-century Mellisende Psalter.Footnote 42 Leaning against the large stone is a second, smaller square-shaped slab (Figures 6–7), which Ernst (Reference Ernst2009: 163) and others (Lepage Reference Lepage1987: 171; Heldman Reference Heldman1979b: 114–5) correctly identify as the Stone of the Tomb. At first, therefore, Type II-A appears to follow the account of the Resurrection given in Mark (16: 1–8), in which the angel rolls away the stone and sits inside the Tomb, rather than that of Matthew (28: 1–10), in which the angel sits outside of the Tomb on the stone he just rolled away.

However, it is also possible that the large and the small stones depicted in Type II-A both represent the rock that sealed the entrance to Christ's Tomb. In fact, from the seventh century onwards a number of pilgrims’ descriptions of the Anastasis report that the Stone had been split into two pieces. For instance, Adomnan, the seventh-century Abbot of Iona, wrote that the stone had been “divided into two pieces” and that “the smaller piece has been shaped and squared up into an altar […] in front of the door of the Lord's Tomb”, while “the larger part of this stone has also been cut to shape, and forms a second square altar”.Footnote 43 This description of a larger and a smaller stone, which is confirmed by other sources (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2002: 218, 258), matches the depiction of two stones found in Type II-A. This iconography also finds parallels in non-Ethiopian Christian art, as seen in a tenth-century ivory panel from the Victoria & Albert Museum.Footnote 44 An even closer parallel to the Ethiopian interpretation of the subject is found in the representation of the Holy Women at the Tomb in the Rabbula Gospels, in which a smaller square slab rests on the right side of the rock on which the angel is seated.Footnote 45 Although seen from different angles, the two stones in the Rabbula Gospels and in Type II-A are treated in an almost identical fashion.

According to Wilkinson (Reference Wilkinson2002: 60–1; Reference Wilkinson, Eastmond and James2003: 109) and Ousterhout (Reference Ousterhout1990), the Holy Sepulchre replaced the sanctuary of the Jewish Temple and functioned as the new Holy of Holies for Christians. Returning to the parallel drawn between the mäqdäs and Christ's Sepulchre in Jerusalem in Type II-A, it is worth noting that, according to Gervers, the origins of the many rock-cut medieval Churches built in Ethiopia, to which one should also add the numerous cave churches such as Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos, “lies in a tradition of cave dwelling which arose from […] a strong attachment to the ascetic example of the early Christian Fathers”, who “in turn could associate their grotto dwellings with the grottos of the Nativity in Bethlehem and of Christ's burial in Jerusalem” (Reference Gervers and Beyene1988: 177). His suggestion adds further weight to the claim that in Type II-A there is evidence of an underlying desire to parallel the Holy Sepulchre with the mäqdäs. This desire resonates with the belief that the mänbärä tabot, found in all Ethiopian churches, replicated the Ark of the Covenant, and that the original Ark was kept in Ethiopia.Footnote 46 The parallel between Ethiopia and Jerusalem offered in Type II is also in line with the Ethiopian emperors’ efforts to reinforce their Solomonic identity. The desire to claim Israelite descent also extended to the Ethiopian clergy which owned, and probably produced, these illuminated manuscript, in fact, as Munro-Hay has suggested (Reference Munro-Hay2005: 86), members of the Ethiopian clergy may have backed the claims of the Solomonics in the hopes of improving their own standing, and, as Kaplan puts it, the desire to claim “Istraelite” descent became a major trope for legitimacy and prestige throughout the Ethiopian highlands’ (Reference Kaplan and Romeny2009: 296).

If the mäqdäs can be paralleled with the Holy Sepulchre, then the altar can be paralleled with Christ's tomb.Footnote 47 Such a belief is found elsewhere in Christendom, and in the early church the altar soon came to be understood as a symbol of Christ's Tomb, as can be seen in the representation of the Holy Women at the Tomb from a twelfth- or thirteenth-century Syriac manuscript now in the British Library,Footnote 48 or in a sixth-century pyxis, now in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Figure 11).Footnote 49 In the pyxis, as St. Clair (Reference St. Clair and Weitzmann1979: 581) has pointed out, Christ's tomb has been replaced by an altar. The iconography of these examples can no doubt be related to that of Type II-A, as already noted by Fiaccadori (Reference Fiaccadori2003). However, it must be emphasized that in the non-Ethiopian examples the curtains are drawn back in order to leave the altar visible, whereas in Type II-A the curtain is closed and screens the altar (Figures 6, 8), that is to say Christ's tomb. This aspect of the iconography of Type II-A, which may be unique to Ethiopian art, can be associated to the reverence with which the Ethiopians regarded the mäqdäs,Footnote 50 an area which even nowadays remains carefully concealed from public view. According to Fritsch, the concealment of the mäqdäs “emphasizes the transcendence of God, who lives ‘behind curtains’” (Reference Fritsch and Uhlig2007a: 630).Footnote 51

In Type II-B (Figure 10) the angel is seated within an arched structure reminiscent of the one seen in the Metropolitan Museum and Gəšän Maryam Gospels (Figures 4–5), and which has been identified above as the entrance to Christ's tomb as it appeared after the construction of the Anastasis. Generally speaking, the arch plays an important role in Ethiopian art, in which it is used as a means to emphasize the holiness of who, or what, is placed under it (Gnisci Reference Gnisci2014: 197; Lepage and Mercier Reference Lepage and Mercier2012a: 130–1). A “triumphal arch” is often used to mark the entrance to the mäqdäs in medieval Ethiopian churches (Fritsch Reference Fritsch and Uhlig2007b: 766), and, as Fritsch and Gervers (Reference Fritsch and Gervers2007: 39–40) have observed, sanctuary arches appear in some of Ethiopia's most ancient churches, such as Dəgum. The use of an arch to delimit the entrance to Christ's Tomb (i.e. to the sanctuary of the Anastasis) in Type II-B echoes the function of arches in medieval Ethiopian churches, and offers another example of how the iconography of Ethiopian illumination and the symbolism of Ethiopian churches are inextricably linked. Its presence also reinforces the impression – gained on the basis of the observations of Type II-A – that Type II presents the viewer with a parallel between the Holy Sepulchre and the mäqdäs.

With regard to the use of arches in medieval Ethiopian Churches, it has been determined that – following developments of the Coptic Church – until approximately the twelfth century the area of the mäqdäs was closed off by a wooden chancel barrier located between the sanctuary and the nave (Fritsch Reference Fritsch and Uhlig2007b: 766). Interestingly, in some cases the arched structures placed at the centre of these barriers – through which access to the sanctuary was gained – recall the arched structures depicted in Type II-B and in Type I. For instance, the chancel barrier preserved in Däbrä Sälam Mikaʾel has, at its centre, an arch structure topped by a cross (Figure 12) that closely resembles the structure depicted in the Gəšän Maryam Gospels (Figure 5). This observation extends the parallel between mäqdäs and Anastasis found in Type II to Type I. However, the depiction of the entrance to the Sepulchre as an arch is the only identifiable anachronism in Type I because the visit of the Holy Women takes place outdoors. On the other hand, because the event takes place indoors in Type II-B – beneath the dome of the Anastasis – the boundaries between different historical contexts become more blurred. Is this a representation of the visit of the Holy Women to the Sepulchre as described in the Gospels, of a service held in Jerusalem to celebrate this event, or of an Ethiopian ceremony? To an extent, the answer to these questions can be found in the circular object held by the angel in Type II-B, which can be identified as the bread of the Eucharist (Figure 10).Footnote 52

Figure 12. Chancel Screen, 13th century (?), wood. Däbrä Sälam Mikael. (Photo: Michael Gervers)

In Jerusalem, after the construction of the Anastasis, a series of liturgical and extra-liturgical services commemorated the death, burial and resurrection of Christ.Footnote 53 As early as the fourth century, the Adoratio Crucis was followed by the Paschal Vigil that lasted until Easter (Janeras Reference Janeras and Kollamparampil1997: 38–49). By examining Egeria's account and the Armenian Lectionary, Bertoniere (Reference Bertoniere1972: 22) has shown that the Vigil service had “two poles”: the church of the Anastasis and the great Constantinian Basilica, and that a first Divine Liturgy in the basilica, was followed by a second one in the Anastasis. For Bertoniere “the purpose of this second Eucharist seems to have been a celebration of the mystery of the Resurrection in the place in which it occurred” (Reference Bertoniere1972: 71). Hence, the second eucharistic liturgy functioned as an in situ “celebration of the mystery of the Resurrection” (Bertoniere Reference Bertoniere1972: 74), which emphasized the close relationship between the eucharist and the Resurrection (Janeras Reference Janeras and Kollamparampil1997: 49).

The depiction of a eucharistic loaf in Type II-B adds a liturgical dimension to the representation of the Visit of the Holy Women at the Tomb. Thus, considering the presence of references to the Anastasis in these illuminations, and in light of the ties between Ethiopia and Jerusalem mentioned above, it seems reasonable to ask whether there is any evidence of a link between the practice of celebrating the Resurrection through a eucharistic service at the Anastasis in Jerusalem, and the presence of a Host in Type II-B. Unfortunately, our knowledge of the Ethiopian liturgy for Holy Week (Ḥəmamat) prior to the late fourteenth century is rather limited (Habtemichael Kidane Reference Kidane and Kollamparampil1997: 93), because the liturgical text currently used by the Ethiopian Church for Holy Week, the Book of the Acts of the Passion (Mäṣḥafä Gəbrä Ḥəmamat), which survives only in manuscripts of the fifteenth century onwards, was probably translated from Copto-Arabic into Ge'ez between the second half of the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth century (Zanetti Reference Zanetti, Zewde, Pankhurst and Beyene1994: 774; Habtemichael Kidane Reference Kidane and Kollamparampil1997: 95). In this respect, according to Zanetti, “like its Coptic model – and far from the antique liturgy of Jerusalem, with its many processions – the Ethiopian Holy Week liturgy is very sober” (Reference Zanetti and Uhlig2005: 725–6). Zanetti's observations exclude strong ties between the Ethiopian liturgy for Holy Week and the liturgy of Jerusalem, although his conclusion refers to the developments of the Ethiopian liturgy for Holy Week after the translation of the Mäṣḥafä Gəbrä Ḥəmamat, that is to say at least a century after the diffusion of the iconography of Type II-B in Ethiopian art. Evidently, as Habtemichael Kidane (Reference Kidane and Kollamparampil1997: 96) and Zanetti (Reference Zanetti and Uhlig2005: 727) have pointed out, an Ethiopian liturgy of Holy Week must have existed prior to the translation of the Mäṣḥafä Gəbrä Ḥəmamat, but “today we can only reconstruct it through different hypotheses” (Zanetti Reference Zanetti and Uhlig2005: 727). Thus, there is no ground to suggest an influence of the liturgy of Jerusalem on the iconography of Type II-B other than the presence of references to the Anastasis, and even these may have been inserted simply because they appeared in the prototype that influenced this type.

Regardless of whether the iconography of Type II-B was not influenced by the Jerusalemite liturgy for Holy Week, because the Eucharist (qʷərban) is consumed in memory of the Lord's Death (1 Corinthians 11: 26), the presence of a eucharistic loaf in the context of the Resurrection is perfectly appropriate. Furthermore, as the visit to the Sepulchre in Type II-B is set within a space that evokes a church, the elevation of a Host becomes more than just a symbol of the Sacrifice and Resurrection of Christ. Indeed, it is likely that, to the learned members of the Ethiopian clergy that consulted, and possibly produced, these manuscripts (Heldman Reference Heldman1998), the angel's gesture would have been immediately understood as a reference to the Divine Liturgy.Footnote 54

The Divine Liturgy, or Qəddase, is the principal liturgy of the Ethiopian Church. The first part of the Qəddase includes the reciting of Psalms, the chanting of prayers, and readings from the New Testament. The second part of the service – during which the eucharistic bread becomes the Body of Christ and the wine becomes his Blood – is centred on one of the fourteen anaphoras in use in the Ethiopian Church.Footnote 55 This latter part of the service is sometimes referred to as akkʷätetä qʷərban, which can be translated as “the sacrifice of the Eucharist” (Appleyard Reference Appleyard and Parry2007: 132). Hence, the liturgy also represents the sacrifice of Christ and his Resurrection. In this respect, if the host symbolizes the body of Christ, then the altar, as noted above, symbolizes the Sepulchre. This correlation is clearly illustrated by a passage taken from the liturgy of the Ethiopian Church – recited during the preparatory service while the bread is covered and the chalice placed on the altar – in which the officiating priest declares: “let my hands be like the hands of Joseph and Nicodemus who wrapped thy body” (Daoud Reference Daoud1991: 23). Just as Joseph and Nicodemus covered the body of Christ and placed it within the tomb, the priest covers the Host and places it on the altar. Thus, it seems that in Type II-B the parallel between the Holy Sepulchre and the mäqdäs is taken a step further by offering an allusion to the Qəddase.

The above conclusions are supported by a number of considerations. First, symbolic representations of the mäqdäs are not uncommon in Ethiopian illumination of the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. This can be seen in a scene from the Gospels of Iyäsus Mo'a in which the Virgin Mary is placed under the same domed structure found in Type II.Footnote 56 As the Mother of God, the Virgin can be paralleled with the mänbärä tabot (Heldman Reference Heldman1979b: 116–7). Just as a curtain emphasizes the sanctity of the Holy of Holies in Type II-A, the Virgin's holiness is signalled by the wings of the angels, which are outstretched over her and function as a canopy in order to create a parallel with the way in which the Ark of the Covenant was placed in the temple (1 Kings 8: 6–7; II Chronicles 5: 7–8; Hebrews 9: 5). More significantly, in the Gospels of Iyäsus Mo'a the angels at her side are depicted holding respectively the cup and paten of the Communion. Hence, also in this context a symbolic depiction of the mäqdäs is associated with the Qəddase.

Second, as first noticed by Fritsch and Gervers (Reference Fritsch and Gervers2007: 42), in the scene of the Entry in Jerusalem from the Däbrä Maryam Qʷäḥayn Gospels the “Temple is represented by a Christian sanctuary, through the arch of which can be seen a small, apparently wooden, portable altar with feet”. Therefore, the Däbrä Maryam Qʷäḥayn Gospels present the same parallel between the mäqdäs and the Temple of Jerusalem that is found in Type II. What has not been noticed is that the substitution between Temple and Christian sanctuary which occurs in the Däbrä Maryam Qʷäḥayn Gospels is not an exception, but the norm in Ethiopian art of this period. Indeed, what is exceptional in the Däbrä Maryam Qʷäḥayn Gospels is that the mägaräǧa is drawn back, allowing us to see the mäqdäs and the altar. Usually, the mägaräǧa is closed, as can be seen in Type II-A and other representations of the mäqdäs in Ethiopian manuscript illumination of the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. For instance, in the Entry into Jerusalem that decorates a manuscript in the National Library in Addis Ababa,Footnote 57 the area of the Holy of Holies is shielded from view by a curtain.

The third consideration concerns the two lamps that are represented above the mäqdäs in Type II-A. These can clearly be seen in the Walters Art Museum and in the Däbrä Sahəl Gospels, but are also represented, in a more symbolic manner, as two red dots in the Däbrä Ma‛ar Gospels. As discussed above for Type I, these lamps may be taken as a reference to the ones which hung from the Holy Sepulchre, as well as to the Paschal Vigil. Nevertheless, in Type II-A, they may also represent the two lights that are lit at the side of the altar in Ethiopian churches to glorify the bread and wine of the Eucharist (Daoud Reference Daoud1991: 7). In the Gospels the Holy Women go to the tomb bearing spices and perfumes to anoint the body of Christ (Mark 16: 1; Luke 24: 1). However, in Type II the Holy Women are depicted in the act of swinging censers. The same iconography is encountered in numerous early Christian examples (Fiaccadori Reference Fiaccadori2003), which were probably influenced by the developments of the liturgy of the Great Week in Jerusalem (Vikan Reference Vikan2010: 37–8).Footnote 58 If it is accepted that Type II derives from a Christian prototype of the sixth or seventh century (Heldman Reference Heldman1979b; Lepage Reference Lepage1990), then the presence of incense burners in Type II may simply be the result of the influence of this prototype. However, it is worth noticing that the burning of incense also plays an important part in the Qəddase, in which it is used as a means to enhance the prayers of the faithful and as a sacrifice offered to God (Rev 5: 8; 8: 3–4). As Fritsch remarks, the incense evokes “the bloodless sacrifice” (Reference Fritsch and Uhlig2007c: 134) and expresses “the expiatory character” (Reference Fritsch and Uhlig2007c: 135) of the Eucharist.

Another possible reference to the Qəddase is found in the Däbrä Sahəl Gospels (Figure 13), in which the two Holy Women carry a censer in one hand and a spoon in the other. This iconography does not find parallels in early Christian art. Spoons, on the other hand, are among the liturgical vessels used in Ethiopia to distribute the Eucharist (Hammerschmidt Reference Hammerschmidt and Gerster1970: 45–6).Footnote 59 The spoons that appear in the Däbrä Sahəl Gospels should not be confused with the handkerchiefs that are held by the Holy Women in the Däbrä Ma‛ar and in the Walters Art Museum Gospels (Figures 6–7). For Mercier and Lepage (2011: 111–3) – who point out that handkerchiefs were used in the Roman world as a consular attribute and, subsequently, as a symbol of imperial authority – the presence of ceremonial handkerchiefs in some examples of Type II offers evidence that the iconography of this type was influenced by a now lost Greek or Palestinian model of the sixth century. While this may well be true, it is also interesting to note that, as first witnessed by Alvares during the sixteenth century, Ethiopians used napkins whilst receiving communion (Beckingham and Huntingford Reference Beckingham, Huntingford and Stanley1961: 328). Thus, the handkerchiefs in the Däbrä Ma‛ar and Walters Art Museum Gospels can also be seen – like the eucharistic spoons in the Däbrä Sahəl Gospels – as another allusion to the Qəddase.

Figure 13. Holy Women at the Tomb, fourteenth century, ink and pigments on parchment. Däbrä Sahǝl, fol. 7 r. (Photo: Michael Gervers and Ewa Balicka-Witakowska)

This interpretation finds further confirmation in the positioning of the angel. In Type II the angel is placed in front of the Holy of Holies, that is to say in front of the entrance to the Tomb, thus acting as a mediator between the worldly and the divine.Footnote 60 In this respect, Type II is closer to the Yəmrəḥannä Krəstos fresco associated above to Type I. However, by now it should be evident that the position of the angel in Type I and Type II affects the meaning of the entire scene. In Type II-B the angel is placed at the centre of the scene holding the Host. The centre is of key importance in this composition because it is the position of the officiating priest (Strauss Reference Strauss and Tzadua1968: 82–3). In this respect, one can draw a parallel between the figure of the angel, which embodies an ideal state of priesthood and holiness, and that of the officiating priest. As Kaplan (Reference Kaplan1985) emphasizes in his article “The Ethiopian Holy Man as Outsider and Angel”, in Ethiopia, as in other Christian traditions, saintly figures – generally monks or ascetics – were believed to have reached a status similar to that of angels, and there are numerous parallels between angels and holy men in Ethiopian literature.Footnote 61 For instance, the word qəddus (holy) can be used to designate both holy men and angels that are known by their name (Kaplan Reference Kaplan1985: 245), and, as aptly put in the Law of Kings (Fətḥa Nägäst),Footnote 62 “monks are earthly angels or heavenly men” (Strauss Reference Strauss and Tzadua1968: 65). To reach such a status the holy man has to practise strict self-denial, and to administer and receive the Eucharist one has to undertake rigorous fasting and preparation in order to purify oneself (Strauss Reference Strauss and Tzadua1968: 85–7). If it is accepted that Type II-B offers an allusion to the Qəddase, then, in this context, the angel functions as the celebrant and represents an ideal model of purity towards which to strive.

All these considerations suggest that the representation of the Holy Women at the Tomb in Type II-B has several layers of meaning. On one level, it fuses the arrival of the Holy Women at Sepulchre, as it is described in the Gospels, with the ritual re-enactment of the event under the dome of the Anastasis in Jerusalem. On a second level, it draws a parallel between the Tomb of Christ and the mäqdäs. Moreover, by depicting the angel with the bread of the Eucharist in front of the tomb/altar, Type II-B functions on a third level by offering an allusion to the Qəddase. In Type II-B, therefore, the historical dimension of the visit of the Holy Women at the Tomb is partially suppressed in favour of an idealized representation of the liturgy. Of course, although the two events belong to different historical contexts, they are not antithetical, but complement each other, as the Eucharist finds its roots in the Crucifixion and in the Resurrection of Christ. On the other hand, the absence of the Host in Type II-A appears to preclude the possibility of seeing an allusion to the Qəddase or to the liturgy for Holy Week in this latter type. Yet, it should not be forgotten that throughout the Christian world not just the Host, but also a cross or a gospel book, were used to confer a mimetic character to the liturgy for Holy Week. For instance, in the Byzantine Rite, by the fourteenth century the priest carried the gospel book on his shoulder in “imitation of Joseph of Arimathea” (Taft 1990: 32); and in the Latin West, by the tenth century, a cross or a Host was placed in a symbolization of the sepulchre of Christ during Good Friday to represent his burial (depositio) and raised early on Easter morning to represent the Resurrection (elevatio): this latter ceremony would be followed by a re-enactment of the visit of the Holy Women to the tomb (Brooks Reference Brooks1921: 30–1).Footnote 63

We must also mention the three crosses depicted above the dome in Type II. Having established that the dome represents the outer structure of the Anastasis Rotunda, it could be suggested that the crosses were included to imitate the architecture of the Holy Sepulchre (Mercier Reference Mercier2000b: 45). However, as Heldman (Reference Heldman1979b: 114) observes, this interpretation is not in agreement with representations or reconstructions of the Holy Sepulchre – in which there is only one cross at the pinnacle of the outer structure and one above the inner baldachin of the church – or with pilgrim descriptions of the Anastasis (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2002: 171). According to Heldman “the dome with three crosses was derived from Palestinian iconography”, and it “symbolizes or stands for martyrium” (Reference Heldman1979b: 114). For Lepage (Reference Lepage1987: 172), on the other hand, the three crosses may represent elements placed on one of the monuments of Golgotha.

Neither Lepage nor Heldman have pointed out that a similar structure, with an arch surmounted by three crosses, is found in a number of seventh-century Aksumite coins of king Armaḥ (Figure 14).Footnote 64 Under the arch is a symbol in the shape of an inverted keyhole. A similar symbol is inscribed within the entrance to Christ's Tomb in the depiction of the Holy Women at the Tomb that decorates an early seventh-century medallion from the Cabinet des Médailles,Footnote 65 which in turn may present a simplification of the elements seen in the pilgrim flask from the Dumbarton Oaks collection.Footnote 66 It is possible that the structure on the Aksumite coins also represents the Holy Sepulchre – a view supported by Finneran (Reference Finneran2007: 212) and Munro-Hay (Reference Munro-Hay1991: 91). Yet the Sepulchre on the medallion from the Cabinet des Médailles, like other non-Ethiopian examples of the Anastasis examined so far, is surmounted by one cross rather than three. On the other hand, in the medallion the scene of the Holy Women at the Tomb is paired with a representation of the Crucifixion. This is quite common in pilgrim art from this period, in which, it has been suggested, the paring of these two scenes summarizes the decorations of both Golgotha and the Anastasis (St. Clair Reference St. Clair and Weitzmann1979: 585–6). It is tempting to suggest that the structure represented on the Aksumite coins of king Armaḥ is evidence of a further stage of synthesis between these two structures: a conclusion supported also by Fiaccadori (Reference Fiaccadori2003: 201), who sees the structure on the Armaḥ coins as an assimilation of Golgotha and the Anastasis Tomb.

Figure 14. Aksumite Coin of King Armah, c. 600–30, silver inlaid with gold. London, British Museum, museum no. 1989,0518.430. (Photo: © Trustees of the British Museum)

Not all of the elements in Type II are equally intelligible to the modern viewer. The presence of the Sun and Moon in Type II-A (Figures 6–9), for instance, cannot be so readily understood. Although the Sun occasionally appears in non-Ethiopian versions of the Holy Women at the TombFootnote 67 – as an indication of the fact that the event took place just after dawn – the Moon does not. Far more canonical is the insertion of the Sun and Moon in most Crucifixion scenes that decorate Ethiopian manuscripts of the fourteenth century (Figure 6), as it is possible to find countless examples of this iconography in early Christian and Byzantine art. In Ethiopian interpretations of the Crucifixion dating from this period, as Balicka-Witakowska (Reference Balicka-Witakowska1997: 67–72) has illustrated, the Sun and Moon offer a reference to the cosmic events described in the Gospels, and to the Apocalypse of John and the Prophecy of Joel.Footnote 68 Hence, for Balicka-Witakowska, the two celestial bodies confer an eschatological character on the scene, and express the supernatural circumstances of Christ's death (Reference Balicka-Witakowska1997: 71).

It is reasonable to suggest that the Sun and Moon that appear in Type II share some of these eschatological meanings. In fact, the two captions accompanying the Sun and Moon in the representation of the Holy Women at the Sepulchre found in the Däbrä Ma‛ar Gospels – which respectively read “the sun hiding its light” and “the moon turned to blood” – are identical to the captions that usually accompany the Sun and Moon in Ethiopian illuminations of the Crucifixion of the same period. Moreover, in the Ethiopian Synaxarium the passage from the Book of Joel that talks about the darkening of the sun and the reddening of the moon is associated to the day of the Resurrection, rather than to the Crucifixion (Budge Reference Budge1928: 179–80). This is not surprising, because the Old Testament passage in which Joel speaks about the Sun and the Moon is followed by a section that talks about the nearing of the Day of the Lord (Joel 2: 28–32). Indeed, as the Day of the Lord, promised in the Old Testament, is associated in the New Testament (Acts 2: 20; 1 Corinthians 5: 5; 1 Thessalonians 5: 2; 1 Thessalonians 5: 2) to the second coming of Jesus Christ (Acts 1: 11), it is evident that the Sun and Moon in Type II have an eschatological significance. They also indicate the fulfilment of the prophecies of the Old Testament, Joel's in this case, through Christ's death and Resurrection; and, in the context of Type II-B, their eschatological character is reinforced by the presence of the Host, which alludes to the liturgy and anticipates the messianic banquet (Luke 22: 30; 1 Corinthians 11: 26). Lastly, it should not be overlooked that a reference to Joel's prophecy is particularly appropriate in this context as Christians have always associated Easter with the Second Coming (Monti Reference Monti1993: 270).

The Ethiopian Church commemorates Joel on Ṭəmqät 21, the same day as Lazarus – whose raising from the dead prefigures the Resurrection (John 11: 25) – is remembered (Budge Reference Budge1928: 177). This reference to the figure of Lazarus leads to another aspect of Type II that requires further attention: the presence of Lazarus’ sibling, Martha, as one of the two Holy Women. In all those examples of Type II in which captions are present and legible, Martha is indicated as one of the two Holy Women and Mary Magdalene as the other. Mary Magdalene's presence in Type II is easily understood in the light of the Gospels (Matthew 28: 1; Mark 16: 1; Luke 24: 10; John 20: 1). However, there is no mention of Martha being among those that went to the Tomb in the Gospels. For Lepage (Reference Lepage1990: 818), Martha's presence in Type II is not only exceptional, but also an indication of the fact that its iconography was inspired by a now lost fifth- or sixth-century Palestinian prototype.Footnote 69

This consideration leads to the more general question of the origin of Type II. As noted above, Lepage is not the only scholar to believe that the interpretation of the theme of the Holy Women at the Sepulchre in Type II was influenced by an early Christian prototype of the fifth or sixth century. For instance, according to Fiaccadori (Reference Fiaccadori2003: 199–200), the iconography of Type II and, more generally, that of the so-called Ethiopian “short cycle”,Footnote 70 which also includes the themes of the Crucifixion and the Ascension, derive from pre-iconoclastic Palestinian models of the fifth and sixth centuries. Fiaccadori has the merit of supporting this argument by emphasizing the similarities between the interpretation of the Holy Sepulchre attested in sixth-century Aksumite coins and that found in several non-Ethiopian examples of the fifth to ninth centuries (Reference Fiaccadori2003: 197–203). Similarly, for Heldman the short cycle which decorates Ethiopian gospels of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, “reflects Late Antique and Early Byzantine iconography” (Reference Heldman and Grierson1993: 131). Though she then cautiously asserts that “the source of this sixth-century iconography is unknown”, adding that “it is possible that the miniaturist had access to a Gospel book from the Aksumite period which was illustrated with similar miniatures” (Heldman Reference Heldman and Grierson1993: 132).

There seems to be little doubt that certain aspects of the short cycle and, more specifically, of Type II, reflect early Christian models. Nevertheless, a more attentive study of this group of images reveals there are other aspects of its iconography that do not find parallels outside of the Ethiopian context, in early Christian art, and that still puzzle scholars.Footnote 71 According to Lepage, even these apparently unique iconographic elements derive from a fifth- or sixth-century prototype, and they only appear as unique because this prototype has been lost. Lepage is so convinced of this that, in an article entitled Contribution de l'ancien art d’Éthiopie à la connaissance des autres arts chrétiens (Reference Lepage1990), he argues that it is possible to improve our knowledge of pre-Iconoclastic art by looking at medieval Ethiopian art. In his view, the “extraordinarily conservative character” of medieval Ethiopian iconography offers “a new basis to reconstruct the themes and cycles of protobyzantine imagery” (Lepage Reference Lepage1990: 800).

Lepage's conclusions are questionable. It is one thing to recognize that there are features in “medieval” Ethiopian Gospel illustration that evoke early Christian art. It is another to suggest, as Lepage does, that by looking at these illustrations it is possible to reconstruct, out of nothing, certain aspects of early Christian art (Reference Lepage1990: 799), as this would imply that for centuries little or no development took place in Ethiopian art. On the one hand, the many centuries that separate the period on which Lepage focuses from that in which these Ethiopian manuscripts were illuminated, should prompt considerable caution in drawing any definite conclusions. On the other, it is simply not possible to suggest that thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Ethiopian iconography has a “conservative character” (Lepage Reference Lepage1990: 800) when we know virtually nothing of its development prior to this period. For instance, as suggested above, it is possible that during the fourteenth century members of the newly established Solomonic dynasty used art to promote their political goals.Footnote 72 More specifically, with regard to the iconography of Type II, it is easy to see how a theme so embedded with references to Jerusalem was in line with the political aspirations of the Solomonics, and of the Ethiopian clergy, who wished to emphasize their ties with Jerusalem.

At the same time, it is likely that the Solomonics wished to reinforce their ties to the Aksumite past. This is not unprecedented. For instance, according to Finneran, it is possible that the Zagʷe – the previous ruling dynasty of Ethiopia – also “sought to reconnect to an Aksumite identity through reference to ‘neo-Aksumite’ architectural schemes” (Reference Finneran2007: 235). Indeed, if it is accepted that the Solomonics used art for political purposes between the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, then it may well be that a Solomonic ruler encouraged the reproduction of an old Aksumite prototype to make an even stronger political statement. Were this to be the case, then the use of the iconography of Type II should not be interpreted as an indication of “conservatism” (Lepage Reference Lepage1990: 800) of Ethiopian iconography, but as the beginning of an artistic renaissance. This conclusion may also explain why an archaic formula, such as that of the Crucifixion without the Crucified, appears in Ethiopian art of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, despite evidence that suggests that other iconographic types were known to Ethiopian artists of the time (Gnisci Reference Gnisci2014: 190–95).

In light of these considerations, it is necessary to look not only towards the fifth and sixth centuries to improve our understanding of Type II, but also at the context in which this theme was used. In fact, by overemphasizing the influence of early Christian art on Type II, as some authors have done, there is a risk of overlooking what differentiates the interpretation of the Holy Women at the Sepulchre in Type II from that in early Christian art. It seems evident that there are some aspects of the iconography of Type II – such as the closed mägaräǧa that conceals the mäqdäs and the presence of the Sun and Moon – that do not find parallels in early Christian art, and which appear to be unique to Ethiopian art. Of course, unless new evidence emerges, it will be difficult to establish if these apparently unique aspects were copied from a now-lost prototype, or if they are the result of adaptation of a foreign model to the local religious customs at a point in time which has yet to be determined. Nevertheless, what matters most is that there are elements in Type I and Type II that appear to reflect beliefs and practices that are characteristic of the Ethiopian Church. For instance, it is possible to point to parallels between the concealment of the mäqdäs in Type II-A, or the manner in which the entrance to Christ's tomb is depicted in Type I and Type II-B, and the architecture of Ethiopian churches. Moreover, it cannot be ignored that, as noted above, the liturgical references present in Type II are in line with the liturgical practices of the Ethiopian Church. Thus, Type II functioned in concert with sacrament and church architecture, evoking them through a depiction of the Resurrection.

Because of this, it may be possible to enhance our understanding of the development of Type II by looking at other fields of research and, in particular, at the evolution of the liturgy and architecture of the Ethiopian Church during and prior to the fourteenth century. A recent study by a liturgist and a historian (Fritsch and Gervers Reference Fritsch and Gervers2007), which examines the development of Ethiopian altars in relation to changes in the liturgy of the Ethiopian Church, offers a first step in this direction, and shows how fruitful the integration of different fields of study can be. Clearly, just as iconography may benefit from further developments in other areas of research, it too may in turn help to improve our knowledge of other facets of Ethiopian history and culture, in an approach that should aim to be as comprehensive as possible.