Introduction

On 28 October 2018, after a bitter and highly polarised election campaign, far-right congressman Jair Bolsonaro of the Partido Social Liberal (Social Liberal Party, PSL) defeated his opponent, Fernando Haddad of the leftist Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, PT), to become President of Brazil. Bolsonaro's run-off victory, winning 55 per cent of valid votes, completed a dramatic rightward turn in Brazilian electoral politics since 2014, when former president Dilma Rousseff had achieved re-election to begin a fourth successive term of PT-led government.

The period between the two elections was widely regarded as one of unrelenting economic and political crisis. In 2016, against the backdrop of a severe recession, corruption investigations and mass street protests, Rousseff was controversially impeached on charges of manipulating public accounts. She was replaced by her Vice-President Michel Temer of the conservative Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, PMDB), whose already low approval ratings plummeted further as the economy failed to recover and allegations of corruption against him emerged. In April 2018, former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was convicted on dubious corruption charges, preventing him from running as the PT's candidate in the upcoming election, despite him being the clear favourite. This cleared the way for Bolsonaro, then a distant second in the opinion polls, who surged into a formidable lead during a short and unusual election campaign in which he survived an assassination attempt, eventually defeating Lula's replacement, Haddad.

Given the volatility of this period, the contingency of events and a general weakness of party identification in Brazil, it is difficult to gauge how far the electoral shift from the PT to Bolsonaro between 2014 and 2018 reflects a deep and durable swing to the Right in public opinion and voting alignments. The challenge is even greater when we look at the diverse social groups who eventually came to vote for Bolsonaro. Election-eve polling indicated that while he led heavily among higher-income voters, he had also attracted significant numbers of those on lower incomes.Footnote 1 In regional terms the divide was clearer, with the wealthy south-east region voting overwhelmingly for Bolsonaro, while the poorer north-east heavily backed the PT. However, within this broad landscape, the low-income peripheries of wealthier metropolises like São Paulo stand out as distinctive.Footnote 2 Unlike middle-class voters in these same regions, who had long voted against the PT, and low-income voters in the north-east, who mostly still voted for the party in 2018, the election confirmed the peripheries as key swing areas in Brazil. They had been an important part of the winning electoral coalitions of Presidents Lula (2003–10) and Dilma (2011–16), but had now swung heavily behind Bolsonaro.

Despite their importance and distinctiveness within Brazil's electoral landscape, little research has examined changing political attitudes in the peripheries of wealthier Brazilian cities. This article contributes to this task. Based on qualitative research conducted in a neighbourhood in the periphery of São Paulo over the course of 2016 and 2017, it explores how respondents experienced the crisis and interpreted it politically. Contrary to claims that the rightward electoral turn in peripheries reflects an ideological shift towards more individualistic and/or socially conservative attitudes,Footnote 3 the empirical data paints a far more nuanced picture.

The argument focuses on two aspects in particular. Firstly, there was relative consensus among respondents in their emphasis on issues such as squeezed incomes, poor public services and urban insecurity, and complaints about the inability and unwillingness of the political class to address them. Secondly, however, there was significant diversity in the way these concerns translated into electoral preferences. To dig into these differences, I identify three groups of respondents – labelled ‘angry workers’, ‘disgruntled citizens’ and ‘nostalgic strugglers’ – each of which mobilised a distinct narrative framework for interpreting the crisis. I argue that respondents’ adhesion to one or other of these frameworks can be traced to individuals’ life experiences and networks of sociability, both heavily linked to place, and that these frameworks also articulate with mainstream political debates in uneven and unpredictable ways. As such, I propose that the rightward turn in peripheries should be understood as resulting from a particular constellation of social and institutional conditions and their contingent interaction with developments in the sphere of official politics.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. The next section provides an overview of recent debates on social structure and political attitudes in Brazil. The following section discusses the ways in which long-term transformations have altered social and institutional arrangements in peripheries, placing these in the context of arguments about the importance of place and of political articulation for electoral outcomes. In the subsequent sections I present my empirical analysis. First I offer a brief explanation of the research methods, followed by an overview of the research site, its social characteristics and recent electoral trends. I then present interview material, analysing the three sub-groups already identified. This is followed by a discussion section that draws out the key implications for how we understand the formation of political attitudes in urban peripheries today, and a conclusion outlining the article's contribution to debates about what has driven Brazil's rightward turn.

Social Structure and Political Subjectivity in Brazil

In recent years, there have been wide-ranging debates about social transformations in Brazil and their implications for political attitudes and alignments.Footnote 4 These have tended to focus on the impacts that economic growth and the PT's redistributive policies during the 2000s had on Brazil's social structure. Income-based measures suggested that large numbers of poor Brazilians had risen into the ‘Classe c’ (located between the 50th and 90th percentiles of the income ladder), interpreted by some as the emergence of a ‘new middle class’ (NMC) in Brazil.Footnote 5 Liberal commentators adopting such arguments in Brazil and other ‘emerging’ economies have claimed that the NMC represents a quasi-revolutionary force that uses its growing influence to demand an end to corruption, the deepening of democracy and/or liberalising economic reforms.Footnote 6 A similar argument was made in a study of disillusioned former PT voters in the peripheries of São Paulo, in which it was argued that a new ideology of ‘popular liberalism’ had taken hold, characterised by a declining working-class solidarity and increasingly meritocratic and pro-market values.Footnote 7

However, the NMC thesis has been heavily criticised on a number of fronts. Income-based measures neglect other key aspects of class, such as educational qualifications and occupation. Once these are included, changes to the social structure during this period appear far less significant.Footnote 8 Rather than a NMC, ‘new working class’ seemed to more effectively capture the shift, in which workers had seen their incomes and consumption rise without significant changes to their life trajectories. Meanwhile, the labour conditions experienced by this new working class had become increasingly precarious, continuing a trend since the 1990s.Footnote 9 Critiques along such lines could produce quite different patterns of political behaviour within the Classe c. Jessé Souza, for example, argued that the precariously employed new working class retained a value system that prized solidarity, predicting that this would lead them to continue backing the PT and its redistributive programme.Footnote 10 For Ruy Braga, by contrast, the ‘precariat’ was becoming increasingly frustrated with the social settlement of the Lula era, leading to a rise in industrial unrest even during the boom years.

Others have addressed similar questions from the perspective of political parties and shifting electoral alignments. For example, André Singer's influential thesis proposed that an important shift occurred in the PT's voter base between Lula's first victory in 2002 and his re-election in 2006, moving away from the traditional middle classes based in the south-east and south of the country, and towards a ‘sub-proletariat’ disproportionately located in the north-east region.Footnote 11 For Singer, this reflected a shift in the PT's electoral strategy towards a ‘conservative pact’ that combined redistributive social and economic policies for the poor with the preservation of traditional elite economic and institutional power. However, this pact would fall apart under Dilma Rousseff's presidency as the economic situation deteriorated from 2014 onwards and both elites and, eventually, many lower-income voters abandoned the PT.Footnote 12

In accounting for these electoral realignments it is also important to consider the growth of ideological forces ranged against PT. According to Ronaldo de Almeida, recent years have seen a ‘conservative wave’ in Brazil, consisting of diverse elements that ultimately converged in Bolsonaro's winning candidacy.Footnote 13 He identifies four distinct but interrelated tendencies: (1) an economic one, aimed at reducing state social spending and ideologically framed around values of individual effort and private initiative; (2) a moral one, seeking the defence of the traditional family and opposed to the liberalisation of cultural norms and the expansion of the rights of women and sexual minorities; (3) a security one, demanding more repressive measures in response to widespread concerns about crime and insecurity; (4) and a social one, expressed in a growing intolerance of political differences in interpersonal relationships. The clearest expression of the latter is the rise in ‘antipetismo’, referring to individual animosity towards the PT that overrides positive support for another party or programme.Footnote 14 Although these different strands have distinct dynamics and are visible to greater or lesser degrees within different parts of the population, there are elements that cut across them. These include a unifying ‘anti-corruption’ discourse, encompassing diverse grievances and a general sense that things are getting worse. Almeida also notes the significant overlap between these themes and issues prioritised by Brazil's growing Evangelical movement, such as the so-called ‘gospel of prosperity’, which prizes individual material enrichment through entrepreneurial activity, and opposition to cultural liberalism. This seeming affinity appears to be reflected in the fact that Evangelicals favoured Bolsonaro over Haddad by a rate of more than two to one.Footnote 15

Urban Peripheries, Place and Political Articulation

While offering important insights, such analyses at the national level do not fully capture the specificities of social and political dynamics in urban peripheries. Instead, it is necessary to understand these as places that possess particular histories and contemporary conditions which mean that they relate to broader trends in particular ways. Peripheries were primarily settled through processes of ‘peripheral urbanisation’, whereby residents built their own homes and neighbourhoods.Footnote 16 The expansion of these areas between the 1950s and 1980s rested on a particular social formation, described by Gabriel Feltran as the ‘projects’ of labourers’ families.Footnote 17 These families, characterised by a sharply gendered division of labour and headed by low-paid but stably employed manual workers, were able to gradually save up to buy plots of land, build homes and raise children who would eventually be better off than their parents.

As explained by Teresa Caldeira, the politics of peripheral urbanisation were ‘transversal’ to the state.Footnote 18 In order to gain access to essential public infrastructure and services, residents had to either mobilise in social movements or work through clientelistic networks, creating incentives for collective organisation and meaning that citizenship was at stake in the very process of urbanisation. During the 1980s, these processes flowered as neighbourhood movements, trade unions and radical grassroots Catholic organisations rooted in the peripheries, along with emergent left-wing political parties, played a decisive role in driving forward Brazil's long process of redemocratisation.

However, as recounted by Feltran, since the 1990s conditions in peripheries have been dramatically transformed by a range of ‘dislocations’.Footnote 19 First, there has been a dislocation in the world of work, with the decline of Fordist production and concomitant rise in unemployment and precarity. This has destabilised the ‘project’ of intergenerational social mobility in peripheries, even if after 2003 the PT's social programmes significantly reduced poverty and created new opportunities for individual social mobility. Second, popular Catholic religiosity has been challenged by the dramatic growth of Evangelicalism, characterised by different institutional arrangements and forms of worship that appear less compatible with progressive agendas. While such churches have expanded hugely in peripheries, it is nonetheless important to note that their worshippers appear to be highly fluid in their religious practices and to circulate between different denominations, challenging the common perception of Evangelicals as religiously dogmatic.Footnote 20 A third dislocation is that social movements have been weakened in terms of their ability to represent the peripheral population, even if they remain active and gained significant influence under PT governments. This is partly due to processes of institutionalisation and partly due to shifting needs in peripheries, away from basic urban infrastructure and services and towards more complex challenges like improving education and security. The fourth significant change in peripheries, meanwhile, is the dramatic growth of illegal markets and violence.Footnote 21 In the case of São Paulo, following a huge increase in violence during the 1990s, the Primeiro Comando da Capital (First Command of the Capital, PCC) criminal faction consolidated its power in the peripheries during the 2000s, leading to a substantial fall in homicides. However, although the PCC regulates the world of organised crime with relative efficiency, the persistence of low-level criminality and of conflict between criminals and police continues to feed widespread feelings of insecurity among residents of São Paulo's peripheries.

While these socio-spatial transformations in peripheries have been well documented, few studies have directly examined their implications for residents’ political attitudes. One exception is the aforementioned study by the Fundação Perseu Abramo, which argued that a rise in consumerism and individualism during the PT years led many peripheral voters to adopt increasingly pro-market attitudes and thus to eventually abandon the PT's redistributionist agenda. A couple of recent ethnographic studies, however, suggest that the reality is more complex. Camila Rocha, for example, found that that support for the PT among many residents in the neighbourhood of Brasilândia in São Paulo's North Zone remained strong. However, it largely rested on ‘symbolic’ dimensions, of past associations and a personal identification with the figure of Lula, rather than an active presence of the party in the area or of people attributing material improvements in their lives to PT policies.Footnote 22 Rocha questions the sustainability of this support, especially given that older residents are far more likely than young people to retain such symbolic identifications. Based on research in the periphery of Porto Alegre, meanwhile, Rosana Pinheiro-Machado and Lucia Scalco argue that many young men who participated in Brazil's consumer economy during the boom years became increasingly frustrated as opportunities were foreclosed by the economic crisis.Footnote 23 At the same time, feeling their status threatened by the growing empowerment of young women and directly experiencing the effects of crime and insecurity in their everyday lives, many embraced the candidacy of Bolsonaro as representing the restoration of a threatened (masculine) order.

The small number of studies on this issue to date means there is only limited evidence of how broad trends interacted with local and contingent factors to reshape political attitudes in peripheries during Brazil's rightward turn. However, analyses of electoral ruptures elsewhere can offer further tools for analysis. Michael McQuarrie, for example, argues that in order to understand Donald Trump's victory in the 2016 US election we must look to transformations that produced a localised ‘revolt of the Rust Belt’.Footnote 24 McQuarrie argues that long-term deindustrialisation not only produced rising unemployment and poverty, but also served to weaken embedded relationships between rustbelt voters and the Democratic Party, which had been mediated by declining trade unions. Trump was able to take advantage of the erosion of Democratic support by politicising economic decline through a campaign that combined attacks on migrants with gestures towards economic nationalism. Thus, while objective and subjective transformations of place had created new political opportunities, it was only the articulation of this by a political actor that ultimately produced an electoral impact.

This is reminiscent of long-standing analyses, broadly within the Gramscian tradition, about how changing social conditions can be exploited by political actors to produce ideological ruptures, particularly at moments of crisis. Stuart Hall famously offered such an account of the rise of Thatcherism in Britain, explaining how economic crisis was increasingly experienced by many ‘through the themes and representations […] of a virulent, emergent “petty-bourgeois” ideology’.Footnote 25 Rather than a natural consequence of the crisis, Hall argued this process was the product of active political and ideological work to ‘disarticulate old formations, and to rework their elements into new configurations’.Footnote 26 Echoing such a view, Cedric de Leon et al. argue that:

ethnoreligious, economic, and gender differences, among others, have no natural political valence of their own and thus do not, on their own steam, predispose mass electorates to do anything. Nor do certain kinds of crisis (such as economic) have an elective affinity for certain parties (for example, socialist, fascist, or religious). Whether variation in religious affiliation becomes politically salient in times of war or recession, for instance, depends in part on whether parties articulate it as a matter of contention.Footnote 27

That is to say that changing social and material conditions experienced in particular places can become politicised in different ways depending on how they are framed and understood. The analysis that follows identifies both the constraining effects of current social conditions in peripheries, which tend to produce significant consensus among residents on a range of issues, and also major variations in how these are politicised and thus how they translate into electoral outcomes.

Research Methods

My fieldwork was carried out in Fazenda da Juta, a neighbourhood of around 38,000 residents in the district of SapopembaFootnote 28 in São Paulo's East Zone (see Figure 1). In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 39 residents, alongside further interviews with key informants from local schools, churches, community organisations, health centres and the police.Footnote 29 All respondents were identified via snowballing and although I did not use formal sampling, I sought balance and representativeness in terms of key demographic variables like age, gender, religion, race, income and housing type. Interviews typically lasted between 45 and 90 minutes and covered a range of themes, including individual biographies, daily routines, attitudes towards the neighbourhood and broader discussions on diverse social and political issues. The research also involved participant observation via more informal forms of engagement with residents and regular participation in activities run by local community organisations.

Figure 1. Location of Fazenda da Juta within the Municipality and Metropolitan Region of São Paulo.

The research was conducted between March 2016 and November 2017, a period that saw a series of major political events which were widely discussed in the national media and in everyday conversations. These diverse, often confusing, developments provided an extremely dynamic backdrop to the fieldwork. However, the ways in which respondents discussed these issues and events provided insights into how they assimilated such new information into more stable worldviews. In what follows, I first provide some general information about the research site and present quantitative data of its social characteristics and recent electoral trends. I then present interview material, through the prism of the three broad groups of respondents identified. Although focused on a small number of individual cases, these provide insights into recurring themes and discourses in the research and are reflective of broader findings.

The Neighbourhood of Fazenda da Juta: An Overview

History and Social Characteristics

Fazenda da Juta (henceforth ‘Juta’) was settled via a complex and often conflictual process of urbanisation during the 1980s and 1990s, which involved numerous land occupations and mutirão projects backed by social movements.Footnote 30 While the construction of the neighbourhood occurred under precarious social conditions, today it is relatively well served by public infrastructure, and also benefits from a strong network of local community organisations with origins in the housing movements. Nonetheless, Juta, and the wider district of Sapopemba more generally, still face many of the challenges common across São Paulo's peripheries, such as high levels of poverty, poor-quality schools, patchy healthcare provision, and insecurity generated by both criminal actors and police.

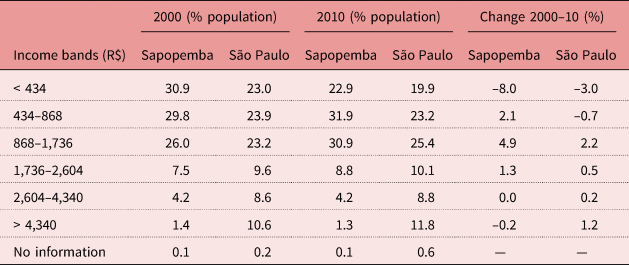

Although taken ten years ago, the 2010 National Census offers important insights into the socio-economic profile of Sapopemba's population and the ways in which it changed during the Lula era. Table 1 shows that in both 2000 and 2010 Sapopemba was considerably poorer than São Paulo, with the vast majority of the population falling into the lowest three income bands, earning less than R$1,736 (in 2019 prices) or about US$415. While the majority of São Paulo's population also fell within these income bands, the city had a significantly larger proportion – close to 30 per cent in both 2000 and 2010 – who earned more than this amount. However, between 2000 and 2010, the lowest income band shrank by an impressive 8 per cent in Sapopemba, compared to just 3 per cent in São Paulo. By contrast, the two income bands above this both grew more quickly in Sapopemba than in São Paulo. This indicates a more dramatic decline in extreme poverty in the district than in the wider city, even if most of Sapopemba's population continued to receive relatively low incomes.

Table 1. Monthly income in Sapopemba and São Paulo by income bands, 2000 and 2010 (percentage of population).

Notes: Income data in the census is collected at the level of the household and averaged for all household members aged ten or over, in this way encompassing the entire population. The income bands reflect the value of Brazil's official monthly minimum wage at the time of the 2010 census (July 2010), but have been adjusted to prices in December 2019. The nominal value of the minimum wage in 2010 was R$510, which is equivalent to R$868 (about US$210) today. For example, the second row in Table 1, of R$434 to R$868, shows those who were earning between half and one minimum wage in 2010. Values were recalculated for 2019 according to the Índice Nacional de Preços ao Consumidor (National Consumer Price Index, INPC), using the Brazilian Central Bank's Calculadora do Cidadão (Citizen's Calculator) platform: https://bit.ly/2ufMfpC (last accessed 23 Jan. 2020).

Source: Elaborated by the author from IBGE, Censo Demográfico 2000 and IBGE, Censo Demográfico 2010.

As shown in Table 2, rising incomes and the falling cost of many consumer goods also permitted a significant rise in consumption during this period. Notably, the proportion of households in Sapopemba with a washing machine or laptop increased considerably (and, again, more quickly than for São Paulo). By contrast, the increase in ownership of more expensive goods like cars was far smaller.

Table 2. Possession of consumer goods in Sapopemba and São Paulo, 2000 and 2010 (percentage of households)

Source: Elaborated by the author from IBGE, Censo Demográfico 2000 and IBGE, Censo Demográfico 2010.

It is more difficult to assess whether and to what extent Sapopemba's class structure shifted over the period. However, data on economic activity give some indication.Footnote 31 Notably, the proportion of employed workers working in ‘manufacturing industries' fell from 27.3 per cent in 2000 to 22.9 per cent in 2010. As a result, manufacturing was narrowly overtaken as Sapopemba's largest employing sector by ‘commerce and repair', which rose slightly from 21.8 to 23.0 per cent. The third largest sector, which showed the largest growth of any, was ‘services and real estate', which rose from 8.3 in 2000 to 12.7 per cent in 2010. The fourth largest in 2010, meanwhile, employing 7.9 per cent of Sapopemba's workforce, was ‘domestic services’, having risen from 6.3 per cent in 2000. Broadly, these shifts point to the continuation of a gradual and long-term decline in industrial employment and concomitant growth of the service sector, with much of the latter in low paid and weakly regulated occupations.

Electoral Trends

Table 3 shows that in presidential elections Sapopemba's voters gradually shifted away from the PT during the party's 13 years in power, while support for the mainstream right-wing Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (Party of Brazilian Social Democracy, PSDB) steadily grew between 2002 and 2014. Surprisingly, the key shift away from the PT appears to have occurred not between the elections of 2010 and 2014 as the economy stalled, but between 2006 and 2010 when growth for the most part remained strong. In 2018, the vote share for the PT in Sapopemba fell to an all-time low of under 24 per cent, less than half the level achieved in 2002, even if Bolsonaro's vote percentage is also slightly lower than that achieved by Aécio Neves of the PSDB in 2014. The difference is made up by a large number of abstentions and spoiled ballots, which account for almost a third of total votes.

Table 3. Presidential results (second rounds) for Brazil, São Paulo and Sapopemba, 2002–18

Notes: For the years 2002 and 2006, the data for Sapopemba refers to the electoral zone of Sapopemba. From 2010 onwards, it refers to two zones, Sapopemba and Teotônio Vilela, which, after rezoning, occupied the same territory. For these years, the results for the two zones were aggregated and averaged. It should be noted that this territory covers most of the district of Sapopemba, but is not identical to it. However, it does include Juta, which has fallen within the Teotônio Vilela electoral zone since 2010.

Shaded cells identify the winning candidates.

A/S = Abstentions and spoiled ballots.

Source: Elaborated by the author from Portal de Estatísticas do Estado de São Paulo, Fundação Sistema Estadual de Análise de Dados (SEADE), Governo do Estado de São Paulo, available at http://produtos.seade.gov.br/produtos/eleicoes/candidatos/index.php?page=ele_sel&back=1 (last accessed 22 Dec. 2019); Election Resources on the Internet: Federal Elections in Brazil – Results Lookup, available at http://electionresources.org/br/president.php?election=2018&state=BR (last accessed 22 Dec. 2019).

It is also worth noting that in November 2016, during my fieldwork, the PT were heavily defeated in São Paulo's mayoral election, with the incumbent Fernando Haddad (who would go on to be the PT's presidential candidate in 2018) losing in the first round to João Doria (PSDB). In Sapopemba, the results were similar to those of the city as a whole, with around 35 per cent voting for Doria, just 10 per cent for Haddad, and slightly less than 20 per cent voting for other candidates.Footnote 32 Given the high number of abstentions and spoiled ballots (which were slightly higher than the winning vote share), Doria was able to pass the threshold of 50 per cent of votes cast to avoid a run-off. This would thus fit with a general trend of declining support for the PT in Sapopemba. Overall, we can say that Sapopemba began, in 2002, being considerably more pro-PT than Brazil, but ended up in 2018 being even less so than São Paulo – typically regarded as a major centre of opposition to the PT.

While this seems to imply a widespread rejection of the PT, interview data painted a somewhat different picture. On the whole, participants tended not to single out the PT, but rather to express disapproval of the political class as a whole. They typically described politicians as corrupt and self-interested, dismissing differences between political parties and holding them collectively responsible for Brazil's crisis. The word ‘crisis’ was invariably volunteered by respondents unprompted, and used flexibly to encompass unemployment and other economic difficulties, corruption scandals, failing public services and insecurity. As such, the notion of ‘crisis’ and the figure of the corrupt politician appeared to be key pillars around which respondents organised their understandings of contemporary Brazilian society and what they believed was wrong with it. The following quote from Joice,Footnote 33 a 22-year-old web developer, was typical:

I think they're all the same. I don't know. I might be talking nonsense, but for me they're all the same. It's like one comes in and things get worse, then another comes in and it gets even worse. So we're kind of going through … it doesn't stop being a crisis whether it's Dilma or Temer … they just walk off together hand in hand, it's the same thing. I think they're there just to show that they're in power, and that's it. But stop taking what's ours by right. They're not going to stop doing that. I think we have the right to something, and they're not going to stop blocking that. Why? For their own benefit, to fill their own pockets. So I don't think that will ever change.

These kinds of negative attitudes towards politicians were reflected in low levels of political engagement. Most respondents claimed to still vote in presidential elections, and almost all who were old enough had voted for Lula at least once (in 2002 and/or 2006). However, in recent elections, few had voted with any enthusiasm. With the exception of a few activists who were involved with local social movements and community organisations broadly aligned to the PT and wider Left, none of the respondents was a member of a political party or had recently attended protests. This included the few respondents who identified as Bolsonaro supporters, suggesting that even those who had decisively embraced the rightward turn had not been actively mobilised.

Three Narratives of the Crisis

Angry Workers

The group I label as ‘angry workers’ was the largest and most diverse in terms of age, gender, race, occupation and religious practice. These respondents had little direct engagement with politics and their understandings seemed heavily shaped by television coverage. They expressed a strong aversion to politicians, were angered by corruption, and complained about high taxes. However, they also identified strongly as ‘workers’, framing this as their primary imagined community. As such, they tended to understand political corruption primarily through the lens of inequality, seeing it as a mechanism for the transfer of wealth from workers to politicians, whom they understood as part of a broader elite. While often critical of the PT they tended to express residual support for Lula and showed equal if not greater antipathy towards the other main parties.

Within this group, it was common for aversion to politics to be expressed in terms of general bewilderment. Many framed politics as something that made little sense, but was clearly a dirty business practised by immoral people. Dona Maíra,Footnote 34 a retired secretary, aged 61, summed up such a view:

I don't understand anything about politics. I'd like to understand, you know. When it starts, on the television, one starts talking, and then another, talking, talking, and I say ‘my God, now I don't understand anything’. Did you see it the other day, one of them insulting another one? What language! […] For me, politics is basically them stealing. I'd like to understand, but it's very complicated, you know.

Dona Maíra understood the outcome of politics as being large-scale theft, but felt ill-equipped to understand the mechanisms through which this occurred. She had trouble distinguishing between different politicians and parties and was unfamiliar with the formal processes of political decision-making. However, as she continued to speak, Dona Maíra's critique soon moved onto the terrain of class inequality:

There's nothing good about them, nothing. Did you see there's going to be a raise? For who? For them! […] And the poor pensioners, when they get a raise it's 5 per cent! If you earn a thousand, or a minimum salary, what does that get you? What's 10 per cent on top of one thousand? It's nothing, just one hundred reais! […] I'd like to understand why they only do things to benefit themselves. Why don't they think of the worker class … the working class? I hate it, I don't like politics. That why I don't go to protests, all that business, because it's all politics.

Dona Maíra may have struggled to understand the procedural aspects of politics, but she was in no doubt as to its consequences. These she understood via a simple comparison of the salaries of deputies, which had just been increased, to workers’ pensions, which were being maintained at a level she felt was undignified. Based on her embedded knowledge of the costs of everyday life in the periphery, Dona Maíra felt able to assert not only the immorality, but also the social injustice of the actions of the political class as a whole. Although not accustomed to using the language of class, she was able to invoke the ‘working class’ as the group to which she belonged and which she believed was the primary victim of the way politics operated in the country.

Rejane,Footnote 35 a 53-year-old seamstress, offered a similar diagnosis, describing politics as a kind of machine producing the enrichment of a few individuals at the expense of the wider population. This system provided both effective impunity for the political class, and the guarantee that resulting economic costs would be borne by the taxpayer:

Let me tell you something, I'd like to have, like, fifteen minutes on the television. Because it's not fair … for people who work, who haven't stolen anything … I say stealing, because that's what it is … to pay someone else's bill. Because if I steal […] you have to come to me. To me, because I did it. Isn't that right? It's like the government. The politicians stole, and then they tell the citizen, the worker, to pay more for their electricity bills, to pay more tax, while they evade it. And of those who stole, who goes to prison? They're punished, but they get to stay at home. If a poor person steals a hat, are they punished? Yes, they go to prison. So there's a difference between the politician and the poor worker, there's a difference.

The narrative of political corruption pursued by anti-government protest movements around 2015–16 has been understood by many as suppressing a discourse of social inequality and class conflict, replacing it with a neoliberal framing that contrasts honest tax-payers with a corrupt and wasteful state.Footnote 36 As the discourses of Dona Maíra and Rejane indicate, the reality among voters in the peripheries appears more complex. There is clearly a view of a corrupt political class exploiting the tax-and-spend functions of the state for its own ends. However, residents of Juta also, frequently and unprompted, deployed the language of class and social justice when discussing these themes. For Rejane, increased taxes were the mechanism by which wealth was transferred to the political class, but she saw the worker, rather than an undifferentiated aggregation of taxpayers, as the primary victim. The inherent inequality of the criminal justice system, in which the poor are punished while the rich are let off lightly for stealing on a far greater scale, is the clearest manifestation of the double standards that she believes run through Brazilian society. She also offers a solution that is framed in terms of radical redistribution:

Let's take what they bought, with stolen money, and let's sell it. Because there are a lot of people who want to buy it. Let's take the mansion, the second home and everything and let's sell what he stole to pay the state. For us, the workers, because no one has done anything for us, for our pocket, in fact they only take from us. So let's take from them, and sell it to pay the debt.

While Rejane's analysis of corruption echoes some of the themes central to Almeida's ‘conservative wave’, she frequently returned to questions of social inequality and justice and these seemed to provide the moral foundation of her arguments. For example, she proved quite immune to the arguments being promoted by the Temer government and much of the media about the economic necessity of raising the retirement age. Instead, she clearly interpreted the reform as a deliberate attack on the working class:

They thought Dilma was bad, it's worse now! She left the retirement at 45 working years, Temer raised it to 49. What's that, do we have to go out and work in nappies?! While politicians have a good pension with few years of service. It's such an injustice!

As this suggests, complaints about high taxes should not in themselves be taken as evidence of pro-market attitudes. Rather, tax liabilities were just one part of a kind of mental accounting that respondents performed to determine whether politics was working for them. In these accounts, a dignified salary, a pension, other forms of social security, access to decent services, and everyday living costs were also factored in. What unites these is the question of the quality of everyday life in the peripheries and the perception of whether or not it was improving. This was to be contrasted with perceptions of the lifestyles of corrupt politicians.

Vanderlei,Footnote 37 a 56-year-old administrative worker at a car company, offered a view similar to Rejane's, understanding corruption as money stolen from taxpayers by politicians:

Vanderlei: I follow the news you know, Mateus, and I get so angry with the news we've been hearing recently. I myself didn't know how much robbery there's been in our country, from our deputies, the president, all this misbehaviour. You see, our country is in such a crisis, in such a situation, and really it's them who created it. Taking our own money, our taxes, it's absurd. This can't happen in our country, it can't, you understand?

Matthew: Do you think that all politicians are the same? Or are some worse than others?

Vanderlei: No, at this point, almost all of them [are bad]. It could be anyone. Though I'm not sure. After I heard from people, after I heard, I don't know how much … people say the theft was all Lula. I earned well in the era of Lula's presidency, I earned money. I earned OK. He reduced the IPI,Footnote 38 he reduced it, especially in my area. I can't say anything, I earned money, I had at least four good years.

Even if he was unsure about possible differences between politicians, Vanderlei attributed his ‘four good years’ to Lula, and was sceptical about claims that Lula and the PT were more corrupt than other politicians and parties. Like other angry workers he was highly cynical about the motivations for Dilma Rousseff's impeachment and believed that the situation had only worsened under Temer. He also appeared to identify with Lula, singling out his status as a fellow worker, who, like Vanderlei, had moved from the north-eastern state of Pernambuco to São Paulo at a young age. He also recognised Lula's efforts to expand opportunities for the poor, which did clearly distinguish him from other politicians:

I'll tell you, he opened up university for everyone who didn't have it before. They don't like that, those politicians from the PMDB, the PDS [sic] and everything, they only want to help who? Their own kids. And he gave it to the poor, black, white, dark-skinned. And that was one of Lula's great virtues, ’cos he was a north-easterner from the countryside and he came to work, and he overcame everything and made it. So they get angry as hell about that. Because the majority of people … the billionaires are a minority and they want to eat everything. And the workers … That's it, that's why they get so angry.

Although angry workers like Vanderlei felt deeply disaffected, they refused to accept the narrative that the PT was solely responsible for the ‘crisis’. Indeed, many acknowledged the party as the only one that had meaningfully improved their lives, and some continued to see Lula as a fellow worker, even if he had become tainted by politics. However, it was very much an open question whom these respondents would vote for by the time of the next election.

At one point during our conversation, Vanderlei took me by surprise. He told me that if Lula was cleared of corruption charges and was able to run he would consider voting for him again. However, if Lula was found guilty he was not sure who he would vote for (he had not heard of Bolsonaro at the time of the interview). If this were to happen, he thought that the best option for the country might be military intervention. In seconds, Vanderlei had gone from defending a central figure of Brazil's redemocratisation, to advocating the return of authoritarian rule. From the perspective of partisan debates this may seem highly contradictory, but in terms of what Vanderlei wanted from politics there was no contradiction at all. Aside from his anger at political corruption, he was also concerned about security, which he discussed in very localised terms. He was particularly exercised about the behaviour of young men who sold drugs at the entrance of a small favela opposite his house. Having served in the military as a young man, Vanderlei felt that young people no longer had the kind of discipline necessary to maintain order in society. During our interview he tended to speak in the language of an angry worker, but at times he drifted into the kind of discourse typical of those I call ‘disgruntled citizens’.

Disgruntled Citizens

These respondents were far fewer in number than angry workers, almost all were male and most attended Evangelical churches;Footnote 39 however, they were diverse in terms of age, race and occupation. They tended to be fairly well informed about, or at least interested in, politics, often getting news and information via social media as well as television. However, none was a member of a political party or had recently attended a protest. These respondents tended to consistently produce conservative discourse, especially when discussing issues such as corruption and security, and were explicitly antipetista, tending to blame the PT more than other parties for the crisis. However, they were almost equally disapproving of the other mainstream parties. They tended to frame their political views in ways that emphasised the nation, and law and order, rather than class conflict, typically referring to an imagined community of ‘citizens’, rather than workers. Nevertheless, when discussing the social policy agenda implemented by the PT they often shifted towards a more inequality-based discourse.

Like Vanderlei, Anderson,Footnote 40 a 44-year-old Uber driver and volunteer with a drug rehabilitation programme run by his Evangelical church, seemed to shift between different ideological frames during our interview, though with the difference that he adopted a firm and explicit antipetista stance. Anderson had previously voted for Lula, but became increasingly exasperated with the party and had voted for Aécio Neves in 2014, ‘to get rid of Dilma’. He had also been in favour of Rousseff's impeachment; however, he had hoped it would lead to fresh elections rather than the accession of Temer, whom he believed to be as bad as his predecessor. When discussing politics, Anderson repeated several far-right tropes. This included a revisionist account of Brazil's dictatorship, arguing that it had saved Brazil from ‘turning into Cuba’ and had been misrepresented by ‘opinion formers and artists’ who falsely claimed they'd been persecuted.

On the other hand, when he started to speak about questions closer to home, his language notably softened. Anderson had voted for Doria in the 2016 mayoral election (‘to get rid of Haddad, who only cared about installing speed cameras so he could fine us’). However, he was unconvinced by Doria's first year in office, saying that he had not delivered on campaign promises like improving access to healthcare. He complained that like a previous PSDB Mayor, Gilberto Kassab, Doria favoured big business over ordinary people. Similarly, when asked for his view on the PT's legacy in office, he offered a surprisingly nuanced, and, if anything, left-leaning critique:

I think we can say the PT were 50 per cent. They got lots of people into university, which you couldn't do [before]. You have to say that. […] But other things [too] that I always say … they did good things, they reduced the IPI for people to be able to buy a television, right, a car. But on the other hand, they didn't think about other things. For me, healthcare wasn't very good, during their administration, it wasn't very good. Where they could have done other things, they only reduced the price of a television.

We can see that despite his explicit anti-PT positioning, Anderson performs a similar kind of accounting to that of the angry workers. The PT had enabled people like him to access higher education and consumer markets that were previously beyond their reach. However, they had not made sufficient progress in improving vital public services. These critiques, along with generalised anger against all the major parties on grounds of corruption, were leading him to take an interest in Bolsonaro. Anderson claimed not to know enough about Bolsonaro yet to make a final decision, but at least considered him to be something new:

Look, I want a new government, so the new option there is Bolsonaro. [I'm] thinking seriously about him, because PMDB, PSDB, PT, right, PMDB, all of them, they're all together, you know? If we want change, what do we have to do? Put new people there! Not to put in a new deputy, a councillor, because he's going to pave my street, or install street lamps on my street, for the neighbourhood … [but] for the country, you know.

Although concerned about educational opportunities and public services for lower-income groups, Anderson's reference to the good of the ‘country’ seemed to override these questions. That is to say, the considerations that informed his political outlook were not radically different to those of the angry workers. The difference was that he was willing to subordinate these concerns to his desire for a ‘new’ political actor, and his identification of the ‘country’, rather than the working class, as his primary imagined community.

This distinction was even clearer in my interview with Fernando,Footnote 41 a 49-year-old security guard and regular attendee at an Evangelical church. Whereas Anderson was not yet sure whom he would support against the PT, Fernando was clear about his preferred alternative. He had previously voted for both Lula and Dilma, but had become increasingly disillusioned with the PT due to what he saw as its special treatment of particular groups, including convicts, non-whites and sexual minorities:

For example, the Bolsa presídio [prisoner's grant], the age of criminal responsibility, racial quotas, prejudice. Because the law is for individuals, not for groups. It's individuals, men, in the general sense, who have to submit to the law, not a created group. The gay group, the lesbian group, religious groups. No, the law is the law. We're all equal before the law. So that's enough. You don't need to have laws for groups if we're all equal. […] The PT divided the country in groups. It turned the country against itself. It was the PT itself that created this whole issue of prejudice, of all these fights over what people think.

Based on his belief that the PT had undermined the unity of the country, Fernando openly declared his preference for military intervention so that order and unity could be re-established. Failing this, he would vote for the candidate whom he believed to embody these values: Bolsonaro.

Like Anderson, though, Fernando had far more nuanced views when it came to questions of economic and social policy. Indeed, much of his own life history revolved around struggling and eventually managing to access crucial public services. Fernando lived with his wife and two teenage daughters in a small but comfortable apartment in which they had been rehoused a few years earlier from their previous home in a precarious land occupation. He had suffered for years from a debilitating disease though was treated within the public health system and eventually cured. Today, one of his daughters benefits from a higher education ProUni grant, a programme introduced by the PT. Indeed, Fernando expressed support for ProUni and also, with reservations, the Bolsa família conditional cash transfer programme:

ProUni is excellent, because it helps people on low incomes enter university, you understand? So any kind of grant that helps people to learn, I'm in favour. Because it's benefitting the people, the financially less well-off. So if there's a grant to incentivise an individual to study, to facilitate the training of that person, I'm in favour. Now [Bolsa] família I'm in favour too, but as long as there's better supervision of who receives it […] because lots of people don't need it.

Fernando propounded values of equality and meritocracy, combining elements traditionally associated with both Left and Right. He agreed with the mainstream left-wing diagnosis that in a highly unequal society poverty reduction and social mobility require significant state-led redistribution. However, he rejected non-economic criteria such as race and sexuality as legitimate grounds for government support, viewing this as anti-meritocratic. Perhaps most emphatically, he argued the state was ineffective and permissive in responding to crime, citing his family's forced daily coexistence with drug dealers in their previous home in the land occupation. For Fernando, reasserting the rule of law, as he put it, overrode every other consideration.

As this suggests, the views of disgruntled citizens like Anderson and Fernando may seem contradictory from the perspective of ideological debates, but they make a lot of sense in the context of everyday life in a place like Juta. For example, Fernando's combination of left- and right-wing policy preferences is firmly rooted in his own experiences of having benefitted from the PT's health, education and housing policies, but also of having worked hard to survive and raise two daughters in a context of limited opportunities and everyday risks. Similar patterns can be observed among many other Juta residents, including those who occupy a polar opposite position on the political spectrum.

Nostalgic Strugglers

It is instructive to compare the views of disgruntled citizens to those of another group with which, on face value, they should have little in common: a group I refer to as nostalgic strugglers. These respondents were more likely to be older, female and to identify as Catholic (although there were also Evangelicals fitting this profile). Many had settled in Juta in the 1980s and 1990s when they had participated in radical housing movements and some continued to be involved with the influential local network of community organisations that had evolved out of these movements. Nostalgic strugglers were more politicised than average, some regularly attended demonstrations, and they invariably voted for the PT (or other leftist parties). However, they were often also critical of the PT, usually not on grounds of corruption, but rather for having distanced itself from the grassroots and cosied up to elites. Perhaps more surprisingly, despite their strong political identifications, they found themselves at odds with important aspects of the discourse and policy agenda of the contemporary Left.

For example, Denise,Footnote 42 aged 57, was a retired cleaner who had participated in the original occupation of Juta and still lived in the home she had built herself, along with her son who was now studying at university. She proudly recounted marching down the Avenida Sapopemba with the other occupiers in the late-1980s, to defend themselves from eviction. Ever since, Denise had been a PT voter, identifying the party as having supported her struggle to overcome poverty and eventually achieve stability and intergenerational social mobility. She believed that the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff had been a ‘coup’ and condemned Brazil's political and economic elites who had instigated it. Nonetheless, when the question of the PT's policy legacy arose, she began to express some reservations, particularly with regard to the Bolsa família programme:

In the countryside, what happens? They receive Bolsa família, and they take that little bit of money, they build a little house, and the family grows. And it's one child a year, the family grows, the family grows, because the money keeps coming. Work? Nothing! You understand? They don't work, and just live on that bit of money, and go on having kids. […] I don't think that's right too, I don't think it's fair.

Denise was troubled by the idea that another of the PT's landmark policies, Bolsa família, should allow poor people the option to live – comfortably, she believed – on state benefits. Her account, of a non-specific ‘countryside’ (‘interior’ in Portuguese) appears to be influenced by stigmatising media representations of poor rural areas. Nonetheless, what seems to make such narratives chime with Denise is her own life experience of working hard for little financial reward. It seemed incongruous to her that a poor person should not have to work to survive.

This was further reinforced by Denise's discussion of Brazil's economic ‘crisis’, a claim that impressed her little:

On that subject I can speak very well. Twenty-five years ago when I arrived here in São Paulo all we had to eat was chicken carcass, you know the bones of the chicken? […] We made oil out of chicken carcass. As we had to do that, we used to ask at the butchers [saying it was] for the dogs, that it was to make food for the dogs. Because we were ashamed, ’cos it was dog food. So today, when people say to me ‘ah, crisis’. […] Crisis! This isn't a crisis! Because crisis … you see parents today who go to the shopping centre and pay one thousand for a pair of trainers, a thousand reais for a cell phone, one thousand five hundred … just for their kid to be mugged on a street corner. Yeah, I see a parent who's clueless […], that's never been through a crisis. Today I don't see crisis, I see bad education, bad parenting. Because I know what it's like to work and not have money to buy bread. So crisis … it's over!

Denise's understanding of what constituted a ‘crisis’ was learned during Brazil's period of hyper-inflation, when extreme poverty of the kind she experienced was widespread. That is to say, it pre-dates the more recent fall in absolute poverty and increased access to cheap consumer goods, but also shifts towards more precarious employment and rising costs in other areas. Despite her expressed commitment to social justice, the notion of poor people having access to consumer goods sat uneasily with her notion of what it means to ‘struggle’.

Such a disconnect can also be detected in attitudes towards political engagement. Elena,Footnote 43 a social assistant at an community organisation in Juta who had been a militant in Juta's mutirão movement during the 1990s, spoke wistfully of a time when politics seemed to make more sense. Like other nostalgic strugglers, she frequently used the word ‘struggle’, which for her had a powerful political meaning:

It was a beautiful struggle. In those days, that kind of beautiful struggle existed. There was unity, the people were united. So if you had money to travel you'd go to the protests or whatever, or if you didn't your colleagues would help you out. […] If you didn't have money for food, the others got together. It was a beautiful struggle.

‘Struggle’ seemed to represent something central to Elena's political identity and values, combining solidarity, a clear political project, and a spirit of perseverance. By contrast she believed these qualities to be lacking in current forms of housing action, in particular in the various new informal occupations that had sprung up around Juta over previous years. She recounted a criticism she had just made of a colleague who was at risk of being evicted from her home in a land occupation:

I'm going to struggle for housing, but in what way are you going to struggle for housing? These days they want everything easy. In our day we knew things took time, it's something that takes years, it doesn't happen overnight. These days they want it for today. That's why there are lots of occupations. I was just having a go at the girl in the kitchen there. […] She came and said to me that she can't sleep at night because she's so worried about being evicted, she has five children. I said this, but also ‘Sheila, you don't want to struggle.’ […] Today people want everything they desire, don't they? They desire lots of things, in the days when we struggled, it wasn't like that. Today people want everything in their hands. No one wants to struggle any more.

Elena continued to participate in social movements and regularly attended protests. However, like Denise, she felt estranged from some political causes that others on the Left had taken up – such as Bolsa família and the legitimacy of disorganised land occupations – and was unimpressed by those who she believed were not struggling. Lessons she had learned over the life course about what constituted valid political objectives and legitimate means of pursuing them seemed to no longer apply. For those like Denise and Elena, political identification with the Left and embeddedness within activist networks seemed to act as a buffer against developing deeper sympathy for explicitly right-wing discourse. However, on some issues – in particular the question of welfare for the poor – their views were often further to the Right than of those who were gravitating towards Bolsonaro.

Discussion: Place, Political Articulation and Opinion Formation in the Peripheries

The three broad groups identified do not exhaust the diversity encountered in Juta during the research. Further groups and subgroups could be identified, for example through closer analysis of the influence of important demographic variables like age, gender and race on political subjectivity. Furthermore, as the discussion has highlighted, the boundaries between the three groups are highly porous, with some attitudes and discourses spanning across them while others do not. In fact, it is probably more helpful to think of them not as groups of discrete individuals at all, but rather as narrative frameworks available to individual subjects to adopt and, to some extent, combine. Notwithstanding these qualifications, these frameworks highlight several points that I believe are crucial for understanding contemporary processes of political subjectivity formation in Brazil's urban peripheries.

A first important observation is that many of the concerns highlighted by respondents, and the broad terms in which they are understood, were relatively consistent and based on widely shared experiences, many of them rooted in place. In particular, these revolved around squeezed incomes, poor public services and insecurity. This strong convergence suggests that concrete conditions and recent transformations in peripheries override abstract ideological motivations in determining attitudes on a wide range of social issues. When invited to discuss politics, respondents rarely spoke in abstract terms – for example, about meritocracy, the ‘free market’ or sexual morality – themes which some have interpreted as key drivers of the rightward turn in the peripheries.Footnote 44 Rather they tended to speak about the concrete, everyday challenges they faced, drawing a contrast between these and a realm of official politics perceived as remote and unresponsive.

Within these broadly shared parameters, many of the variations that did exist could at times appear almost arbitrary. Dyed-in-the-wool antipetistas could express support for large parts of the PT's policy legacy, while proud petistas could be deeply hostile to flagship PT policies. Those with no overriding partisan identification, positive or negative, combined heterogeneous elements in ways that best made sense to them. In other ways, however, clear patterns could be observed. The broad terms in which respondents framed their answers seemed to signal that a particular interpretive framework was being called into action. The framework deployed allowed for subjects to construct arguments around the issues or principles they ranked as most important, though without obliging them to completely abandon views on other issues that might not neatly fit. Such discursive strategies seem to offer citizens in the peripheries a way of dealing with the problem of a poor alignment between their needs and what mainstream politics has to offer them. Given that most politicians and parties fall badly short, it is difficult for peripheral subjects to maintain a high degree of partisan loyalty or ideological consistency. Interpretive frameworks make it possible to harness diverse experiences and opinions into more coherent lines of argument, thus allowing at least the possibility of taking a position in relation to official politics that can go beyond blanket rejection.

This raises the question of how individuals come to arrive at a particular framework. Based on the examples presented, this process appears to be the product of diverse influences operating over different scales and temporal horizons. Firstly, they clearly related to individual experiences and lessons learned over the life course, many of which were also associated with place. When justifying their views, respondents could emphasise experiences of winning improvements to their neighbourhood through social mobilisation, or the persistence of inadequate services. As this implies, while perceptions of place are heavily circumscribed by concrete conditions, individual experiences of them may still vary significantly, leading to more positive or negative perceptions and, ultimately, different political interpretations.

A second factor that appears to heavily influence the adoption of narrative frameworks, and which is also strongly tied to place, is the individual's network of sociability. The political identities of nostalgic strugglers seemed heavily linked to their involvement with left-aligned social movements and community organisations. Meanwhile, disgruntled citizens were disproportionately likely to regularly attend Evangelical churches. In this case, there is clearly a strong amount of overlap between religious doctrine and core tenets of ultra-conservative ideology, most notably in the values associated with the ‘gospel of prosperity’ and shared opposition to cultural liberalism.Footnote 45 However, in the heterogeneous and fluid institutional landscape of urban peripheries,Footnote 46 such relationships should not be viewed deterministically. Residents may frequent left-leaning community organisations or conservative churches without significantly absorbing their ideological tenets and political assumptions. Rather than comprehensively moulding subjects then, they might better be understood as anchoring individuals to broad partisan identifications.Footnote 47 It is interesting to note that explicitly religious issues were rarely mentioned by disgruntled citizens, while nostalgic strugglers’ identification with the Left seemed to be based more on concrete personal experiences and relationships than commitment to abstract principles. For most angry workers, personal experience, the influence of family, friends and mainstream media, and identification with the category of ‘worker’, seemed to substitute for exposure to more structured organisational influences.

However, even if shared socio-spatial conditions, individual life experiences and networks of sociability – all strongly tied to place – are crucial to the formation of political opinion in peripheries, these must still ultimately interact in some way with the realm of formal politics, even if only at election time. It is here that the question of ‘political articulation’ becomes central. While most residents of peripheries may perceive politics as distant from their everyday lives, political actors can articulate certain matters of concern in ways that resonate. Where politicians can engage with and build upon existing framings and linguistic tropes – of ‘workers’ or ‘citizens’, ‘struggle’ or ‘order’ – they may improve their chances of attracting support. At particular moments this may take a cathartic form, when everyday lived experience and attitudes that usually fail to be meaningfully represented publicly are suddenly articulated in mainstream debate. The victories of Lula, and, at least for some peripheral voters, Bolsonaro's victory in 2018, may have been experienced in this way. However, for most residents, elections are experienced as momentary choices between generally unappealing options, after which things largely remain the same.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Rightward Turn

The evidence from Fazenda da Juta suggests that ideological factors – understood as a consistent commitment to right-wing principles, whether articulated explicitly or implicitly – have played only a minor role in the rightward electoral turn in peripheries during the crisis. Even respondents who identified politically with Bolsonaro did not consistently echo his agenda, and certainly not with regard to themes such as meritocracy and marketisation. The consistency of concerns expressed by diverse respondents, in particular emphasising squeezed incomes, poor public services and insecurity, suggests that the experience of living under particular socio-spatial conditions overrides ideological commitments. On many substantive issues a resident of the periphery would be more likely to agree with a neighbour who votes for a different party than with a middle-class Paulistano who happens to vote for the same one. As such, we should primarily look to factors associated with place and political articulation, rather than ideology, to understand the rightward turn.

If place provides the basis on which substantive issues are prioritised by respondents, how did a candidate who seemed to promote a largely elitist agenda manage to capture so many votes in the peripheries? It is true that Bolsonaro did not meaningfully articulate issues like the poor quality of public services and squeezed incomes. Indeed, he made almost no concrete economic or social policy offer to lower-income voters at all. On the other hand, his focus on the issue of corruption would have found fertile terrain. While largely viewed as a moral issue by the middle classes, corruption was commonly understood by respondents from Juta through the lens of inequality: as a means by which wealth was transferred from workers to the elite. Such conceptual flexibility allowed Bolsonaro to articulate different, even contradictory, messages to these different constituencies, a crucial skill when trying to construct a diverse electoral coalition. Through his hardline discourse on security issues and, to a lesser extent, Bolsa família,Footnote 48 he also fed into narratives that were already strongly present in peripheries. As compared to Bolsonaro's core upper-middle-class constituency, these issues take on very different meanings in a place like Juta, where anxieties about insecurity and the value attached to hard work are experienced as everyday personal struggles and form a core part of many people's identities. All of this is to say that Bolsonaro, whether intentionally or not, was able to articulate matters of concern in ways that would have resonated with significant numbers of peripheral voters, tapping into their changing experiences of place.

However, while such an understanding of political articulation revolves around the mediated discourse of distant political actors, the local institutional context through which such discourse flows and takes on practical meaning seems at least as important. Local institutions play a crucial role in either reinforcing or countering narratives and proposals articulated by politicians. As others have pointed out,Footnote 49 social movements, grassroots Catholic organisations and trade unions that played such a role in connecting the PT to peripheral populations have all lost space in peripheries over recent decades. Although Juta may have survived this process in better shape than most given its strong network of left-aligned community organisations, even there it is clear that many perceive the party as being just as distant from their lives as all the others. While Bolsonaro's ability to articulate some pertinent issues in peripheries in 2018 was highly contingent, such shifts in the social and institutional structure of life in peripheries seem more durable and indicate that it will be difficult for the PT to recover the ground it occupied at the height of its influence. Nonetheless, there is clearly still a large appetite in places like Juta for a politics of redistribution and improved public services. If there were not already a mass, left-wing party competing for votes in the peripheries, it would certainly be necessary to invent one.