Essays on popular music of the rock ‘n’ roll era, as a prominent pop scholar once remarked to me in passing, can all too easily devolve into love letters to the author's own record collection. We all know how important record collections are to the study of popular music of the past half-century, of course; if popular music didn't exist in recorded form, it would hardly exist at all, except for whatever happened to be going on in the present moment. (Try to imagine the study of rock ‘n’ roll based entirely on sheet music.) However, the fact that popular music does not have a canon, at least not yet, and perhaps never will in the sense that art music does, has meant that what is held to be sufficiently worthy of serious discussion, in print or anywhere else, often ends up being largely a matter of personal taste.

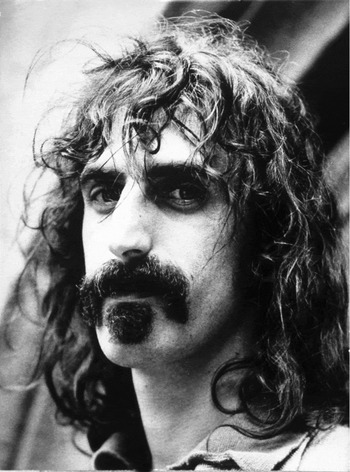

In the case of Frank Zappa (see Fig. 1), the recorded legacy is sufficiently enormous and diverse—nearly a hundred CDs’ worth, not counting material released by others or the posthumous productions of the Zappa Family Trust—to keep people arguing for a long time about the relative merits of their favorite albums: a debate to which a great variety of interested parties, ranging from pop scholars to journalists to a still fervent and active fan base, enthusiastically contribute. The two albums named in the title of this essay might simply seem like eccentric choices for special scrutiny, since for all but the most avid Zappaphiles they are rather on the obscure side. Certainly, they are not among his most popular, or even most notorious; yet, as will be argued at length in this essay, a comparison of the two—one from quite early in Zappa's career, the other very late—yields insights into his oeuvre and the shape it took over time that are unlikely to be gleaned from any other approach. I propose that Lumpy Gravy (1968) and Civilization Phaze III (1994) are of interest in three ways: first, as individual works; second, for the unique connection between them; third, for the perspective they afford on their creator and his unusual development, from the freakish figure he cut in the late 1960s, marginalized in the pop world, barely acknowledged in jazz, and unknown in art-music circles, to the possessor of a name with instant recognition value in all three by the end of his life in 1993—yet still largely (and largely by choice) an outsider, a stranger to any established classification in Western musical culture.

Figure 1. Frank Zappa. Copyright London Features International; used by permission.

I

Zappa, in short, was a maverick, as Michael Broyles has aptly characterized him: one in a long line of such figures in the musical history of the United States, neither the first nor, most likely, the last.Footnote 1 Among Broyles's gallery of mavericks, though, probably no one devoted more of his time and energy than did Zappa to negotiating the boundary between pop and art music. This negotiation, in fact, is really the principal defining theme of his career, and it was sounded early on. In the first couple of albums with his first band, the Mothers of Invention, Zappa was already laying claim to basically uncharted territory, in which he and his retooled R&B ensemble set down original pop songs in various styles (some of them parodistically intended) side by side with material of a decidedly different cast, strongly inflected by the modernist music of the early and mid-twentieth century that had so engrossed him by this time. Sometimes, in fact, actual twentieth-century compositions (the early Stravinsky ballets were particular favorites) were quoted briefly. Also already at this point, though, Zappa was looking ahead to a time when (he hoped) he could work independently of the Mothers of Invention, with musicians who, unlike most of his bandmates, could read music and could be hired to play what he wrote for them—as they would for any “real composer.”Footnote 2

Zappa's first opportunity to do just that came shortly after the release of the Mothers’ first, double-LP album Freak Out! (July 1966) and during the planning stages for their second album, Absolutely Free. Nick Venet, a producer working for Capitol Records, approached Zappa and managed to persuade him that his contract with MGM did not prohibit him from accepting employment with a different label as composer and conductor of his own music for a studio ensemble. MGM, as it turned out, had a different take on the matter, and the ensuing legal squabble ultimately served to restrain Capitol from releasing any album bearing Zappa's name.Footnote 3 More about this episode later. For the moment, what might be of interest is that someone like Zappa, with only one very modestly selling album to his credit to that point, was considered worth fighting over by two major record companies. In this respect, Zappa clearly benefited from the tenor of the times, which by early 1967, when the studio-orchestra sessions for Lumpy Gravy were done, had begun to suggest that any intriguingly innovative (or simply weird) music had a shot at making serious money in the youth-oriented market, as long as that music had some sort of connection, however tenuous, to rock ‘n’ roll.

In any case, what Zappa eventually came up with was no “solo album” of the sort that would become familiar later in pop history, featuring as performer (and perhaps also as songwriter) someone previously known principally as one among several members of a group. On Lumpy Gravy, released in early 1968,Footnote 4 Zappa the guitarist or singer was nowhere in evidence, and there were no “songs”—no singing, in fact, of any kind. (For that matter, there weren't even any separate tracks, apart from the two sides of the LP, each of which played without pause.) What the half-hour or so of Lumpy Gravy's duration did contain fell into five basic categories: (1) instrumental passages, played by a small studio orchestra, that deliberately emulated the styles of twentieth-century modernist composers (principally Varèse, Stravinsky, and Webern); (2) instrumental passages, either for studio-orchestra instrumentation (the same as or similar to that of (1)) or for pop combo, in a style closer to pop, sometimes reminiscent of commercially oriented music for films or television; (3) real sounds manipulated by tape-speed alteration, mixing, filtering, and other distortion—musique concrète, in other words—sometimes mixed with percussion; (4) spoken material, consisting of monologues about cars or conversations about inscrutably bizarre topics; and (5) snippets of music taken from miscellaneous other, unidentified sources. Although all the performers were credited, no program as such was announced; nothing in the liner notes was provided to orient the listener. The self-deprecating title of the album seemed appropriate, and it went well, too, with the description on the front of the record sleeve: “A curiously inconsistent piece that started out to be a BALLET but probably didn't make it.”

By all accounts, Lumpy Gravy did not sell well—even less well than the two or three Mothers of Invention albums that were out by that time,Footnote 5 although there is some question as to whether MGM marketed Zappa's solo effort as vigorously as it did his work with his band, since anecdotal evidence from the time suggests that copies of Lumpy Gravy were hard to find.Footnote 6 Naturally, even if this album had flopped musically as well as commercially, it would be of interest to us now, given Zappa's subsequent trajectory. In fact, there is far more to Lumpy Gravy than could have been apparent to any first-time or casual listener in 1968. Extending across the often disorienting juxtapositions of mutually incompatible materials are long-range progressions and continuities that eventually turn out to be promoted by the surface discontinuity. One example among a great many that could be discussed is the voice and text (the two are inextricable) of what can be conveniently labeled “Motorhead's Monologue,” from Part One of the work. Concurrently with the following discussion, the reader is referred to Table 1, which tracks the “continuity” of Part One of Lumpy Gravy by marking the sequence of events with the timing in minutes and seconds.Footnote 7

TABLE 1. Descriptive Continuity of Lumpy Gravy, Part One

James Euclid (“Motorhead”) Sherwood, a friend of Zappa's from high school days, was a somewhat peripheral member of the Mothers of Invention, whose association with the band had begun in the capacity of roadie. He was also a sax player of limited ability and was therefore allowed to play once in a while, mostly in a backup role. As his nickname implies, he was crazy about cars and lived to work on them. Zappa recorded his reminiscences of jobs he'd held and of cars he'd owned or gained access to through women he was dating, and used the tape as raw material.

Motorhead's voice makes its first entrance approximately one-third of the way through Part One, shortly after the first interlude featuring conversation inside a piano (to be discussed later). Motorhead does not participate in this conversation, so his voice at 5:48 is new. (This and his subsequent appearances are listed in bold face in Table 1, for ease of reference.) At this point, he is in the middle of an account of the technical attributes of a car's engine—or so one would gather; out of context it's almost impossible to decipher. (What he says sounds something like “Bored-out 90-over with three Stromberg 97s”—it lasts just a few seconds.) This first appearance of Motorhead is made even more ephemeral by its placement as an interjection into the percussion/concrète treatments that Zappa uses as segue/transitional music at many junctures in Lumpy Gravy. This ephemerality can be readily appreciated by hearing the voice snippet in a larger context: say, 5:45–6:16.

Motorhead's second appearance is also an interruption, within a kind of faux-Chinese music (rather ironically clichéd in its employment of a repeating fragment of pentatonic melody harmonized in parallel fifths) that appears only here in this piece (6:17–6:30). At this point, what Motorhead is saying is readily comprehensible: “good bread, ‘cause I was makin’, uh, $2.71 an hour”—even though the line is subjected to tape-speed distortion (“wowed”); so in that sense our monologuist has acquired more of a presence. Although the highly artificial chinoiserie surrounding him has no larger significance, the voices commenting on it do: They're the piano voices we've heard previously.

Meanwhile, another element has been cut into Motorhead's voice and added to the segue music: pig-like snorting noises, treated in reverb or sped up. These rude but funny sounds are featured on several albums Zappa made around this time (in the liner notes for We're Only in It for the Money, they are called “snorks”), and the connection to the later Uncle Meat becomes especially clear in the segue following the chinoiserie (6:17–6:41), which features these snorks again, combined with coughing and celesta-like sounds, all sped up, apparently, via tape-playback manipulation. Material of this sort will show up again later in Lumpy Gravy.

Motorhead's next appearance, his third, is the first extended, coherent segment of monologue. It comes at 6:42–6:53, almost a minute after his voice was first heard, and functions to start zeroing in on his main subject (cars). The listener still lacks context, however; just what the speaker is getting at is still unclear. This revelation will have to wait for the monologue full-blown—and before it arrives, some new business will be initiated, and some old business completed.

The new business, a foretaste of the music that will eventually conclude Part One, is a vaguely Varèsian passage featuring bass flute.Footnote 8 This reference lasts only four seconds, while the old business, a reprise of a previous number, takes appreciably longer: a good 2′30″ or so. This previous number is an instrumental version of a song, known from several recordings of it that Zappa issued later, titled “Oh No” (see Example 1).Footnote 9 The reprise here in Part One is somewhat old fashioned in effect, evoking as it does the type of recycled material typically heard in a Broadway musical or movie soundtrack—but it is given a decidedly “modern” spin with the lead-in, in which the brass play a harmonization “à la Stravinsky” of the first seven notes of the melody, in a different rhythm and tempo, followed by a studio-manipulated speedup of the coda music, after which the more conventional full reprise proceeds, complete with greatly extended “big climax” treatment of the coda.

Example 1. Zappa, “Oh No.” Copyright 1968 and 1973 Frank Zappa Music/Munchkin Music; all rights reserved; used by kind permission of the Zappa Family Trust.

It's hard to be sure just how this passage is intended to come across, laden as it is with the sort of clichés one might have heard in music for movies or television at that time. One possibility is that Zappa intended this treatment, the last we will hear of “Oh No” in Lumpy Gravy, quite straightforwardly, devoid of any ironic pose, simply because he was still feeling his way in this new medium, writing for the mostly acoustic instruments of a studio orchestra and providing notated parts for musicians who were not his own band members. On the other hand, it's also perfectly possible that Zappa was well aware of the clichés and derived some amusement from milking them for immediate “structural” purposes. This interpretation, in a way, is more plausible, since Zappa was well known throughout his life for refusing to make qualitative distinctions between “high” and “low” forms of musical art.

The next two minutes of Lumpy Gravy (9:18–11:05) are devoted to the full-blown monologue. Motorhead speaks continuously throughout, although his voice has to compete with a few added attractions and distractions. This part of Lumpy Gravy was what Zappa referred to when he mentioned doing “a thing with voices, with talking, that is very like one of [John Cage's] pieces” (perhaps alluding to the Folkways recording of Indeterminacy?), and the incongruous subject matter of the monologue, even though prepared by those fragmentary previous entrances, does strengthen the resemblance to Cage.Footnote 10 Other elements of interest include the brief, “Potzrebbie”-like quotation, a cappella, of “Louie Louie” (9:23–24)—drifting in, seemingly, from nowhere, although of course it is funny—and the recontextualization of the earlier, second appearance of Motorhead's voice (the “$2.71 an hour” fragment) at 10:15–19. Meanwhile, at 9:50 a jumble of other voices has entered, sounding like an overheard conversation but just out of range of comprehensibility; these other voices become more and more of an intrusion, especially after 10:20 when the R&B drumset enters, until with the words “And then I got another pickup” the monologue is abruptly cut off (11:05) by music at a much faster tempo than the R&B drumbeat, a hard-driving urban-blues-band number, Paul Butterfield style, with harmonica in the lead.

By following the successive appearances of Motorhead's monologue material, one understands that they form a discernible progression, in which Motorhead first (1) speaks only briefly and in car-talk jargon, simultaneously with other sounds; then (2) becomes understandable but still brief and distorted; then (3) is heard at greater length, in words that are clear but have no context (like the second appearance); and finally, (4) is featured in a much longer passage that at last provides some context, only to make us realize that what we're hearing is still an excerpt from some larger account of a rather aimless existence. Then, as it begins to be submerged by increasing competition on the soundtrack, Motorhead's voice suddenly vanishes, supplanted by the larger demands of the structure that Zappa is creating, as new lines of development arise. During this segment of Part One—about 5′20″ in duration—one major thread of continuity is wound essentially to conclusion (“Oh No”), another begins to be spun (pseudo-Varèse), some sounds make unique appearances, and other sounds appear that have been heard before and will be heard again.

The voices in the piano, mentioned earlier in passing, represent another thread of continuity, handled rather differently by comparison to Motorhead's monologue. Zappa's own account of how the raw material for this part of Lumpy Gravy was generated is worth quoting:

In 1967, we spent about four months recording various projects (Uncle Meat, We're Only in It for the Money, Ruben and the Jets, and Lumpy Gravy) at Apostolic Studios, 53 E. 10th St., NYC. One day I decided to stuff a pair of U-87s [microphones] in the piano, cover it with a heavy drape, put a sandbag on the sustain pedal, and invite anybody in the vicinity to stick their head inside and ramble incoherently about the various topics I would suggest to them via the studio talk-back system.

This set-up remained in place for several days. During that time, many hours of recordings were made, most of it useless. . . . Some of this dialog—after extensive editing—found its way into the Lumpy Gravy album.Footnote 11

At first, the cast of characters, consisting of four or five men and three or four women (some of the voices are difficult to tell apart, and no script is provided), seems to range about aimlessly, discussing topics at random (3:58–5:18). The outlines of their situation, in very general terms, begin to emerge in Part Two: They have found themselves living, for some reason, inside a giant piano with the dampers raised from the strings. They show a distinct disinclination to venture outside, owing, as eventually becomes clear, to the grotesque creatures that lurk there: ponies with fearsome teeth and claws, and flying pigs. These “piano people,” as they may conveniently be called, seem quite passively resigned to their fate, possibly stoned and/or not very intelligent—in other words, something like the self-victimizing hippies portrayed in Lumpy Gravy's sister album, We're Only in It for the Money. The plot outlines are conveyed fairly elliptically, by way of about 1′20″ of dialogue in Part One and slightly less than five minutes’ total in Part Two, broken into segments of varying length, ranging from as long as 2′30″ to fragmentary interjections. Thus the piano people's situation is definitely not the principal focus of the work; there's just too much else going on, and the flow of Lumpy Gravy as a whole does not seem particularly “narrative,” partly for that reason and partly also because of the jump-cut shifts between mutually incongruous materials.

II

The foregoing discussion should serve to drive home the point that if Zappa has succeeded, in Lumpy Gravy, in presenting credentials adequate to admit him to the camp of musical modernism, he hasn't done so simply by imitating, however skillfully, Varèse or Stravinsky or Webern. The real modernist orientation of Zappa's work here resides in what he has done that is new: that is, in the juxtaposition of stretches of music synthetically derived, as it were, from the sound-worlds of twentieth-century modernism with the four other types of material mentioned earlier—all strikingly, even jarringly, incommensurable with those emulative passages, and with one another as well. Types 3 and 4, in particular (manipulated real sounds and spoken material), might readily bring to mind the variety of musical modernism often referred to as avant-garde.Footnote 12 Zappa himself encouraged such associations: As noted above, he had drawn attention to “a thing with voices” that was “very like” a piece by Cage, “except that of course in our piece the guys are talking about working in an airplane factory, or on their cars”—a clear allusion to Motorhead's monologue.Footnote 13 Beyond such specific resemblances of content, however, lies the more general one of compositional technique. During the question period after a lecture he gave in 1969, Zappa noted that the aleatory aspect of the Happening, as Cage conceived of it, had had an influence on Lumpy Gravy, adding: “The way Lumpy Gravy was put together was sort of like that; I had a certain number of building blocks to work with, all committed to tape, and at one point I just cut these lengths of tape and just shuffled them around, and stuck them together; and there are sections that were assembled that way.”Footnote 14 In an interview given a year earlier, Zappa confided that if he still had the master tapes for some of his early recordings, he could take a razor blade to them and put them together again in twenty other, different ways that would all make equally good sense.Footnote 15

Cage's example, then, clearly served Zappa as some sort of model. Yet there can be no question here of slavish imitation—for no one before Zappa had juxtaposed and combined musical materials of the pop and art variety to such an extent, creating a compositional environment in which imitation Stravinsky, Varèse, and Webern butted up against fragments of surf music, deliberately cheesy pop arrangements, concrète/noise treatments à la Stockhausen or Cage (the most likely influences here), people talking into a piano that is being used as a resonator, and even—once in a while—some straightforward Zappanian instrumental music, not much like any rock ‘n’ roll of that era but not in any studiedly modernist, dissonant vein either. The visual presentation of the album, always an important aspect of any Zappa project, fits right in with an avant-garde sensibility too: The inside cover, or gatefold, looks deliberately provisional and unfinished—as if it might just as easily, and suddenly, assume some completely different form.Footnote 16

One other possible source for the avant-garde sensibility suffusing Lumpy Gravy is the circumstances of its genesis—circumstances that we now know something about, thanks to audio-documentary evidence that has only very recently been made public. Zappa's seemingly offhand comment, cited earlier, about the malleability of all his early albums can now be seen in a new, possibly even more informative light. Among the contents of the three-disc set entitled The Lumpy Money Project/Object, released by the Zappa Family Trust in early 2009, are two recordings antedating Lumpy Gravy that might now plausibly be called sketches for it: one, a master bearing the date of 19 May 1967, recently found in the archives of Capitol Records; the other, an even earlier assemblage made by Zappa from studio recordings in February of the same year, entitled “How Did That Get in Here?” which has surfaced among the contents of the vast vault of tapes amassed by Zappa during his lifetime of touring and studio work. Their exhumation has made it possible to offer conjectures as to some of the stages, at least, through which Zappa's creative process took this music on the way to its final version.Footnote 17

Although the February 1967 material was unknown before its release in 2009, the “original” (May 1967) version of Lumpy Gravy done for Capitol has been mentioned at least twice by Zappa in interviews. In December 1989, he gave a detailed recollection of the hurried circumstances under which he finished the score and parts to meet a deadline for a recording session, noting also that “MGM refused to allow this album to be released, and there was an argument over it for a year, finally resulting in MGM buying the master tape from Capitol, and then, I added the vocal parts in there, and it came out.”Footnote 18 Ten years earlier, in an interview with David Fricke, Zappa had said much the same thing, adding this tantalizing bit of information: “In fact, if you're looking for rare collectors’ items, there are 8-track tapes with the Capitol label of Lumpy Gravy that have a different Lumpy Gravy than the album. Those have only the orchestral music and they do exist.”Footnote 19 One collector apparently did succeed in obtaining a copy of this elusive item, in the form of a test pressing; the details he reported, including total timing and the master number on the label, agree with the details given in the 2009 Lumpy Money release.Footnote 20

A short digression is in order here. The existence of an earlier version of Lumpy Gravy had been rumored for years, but since little if any hard information was available about it, published accounts tended to be sketchy. The general consensus seemed to be that, whatever material was returned to Zappa as the result of settling the dispute between Capitol and MGM, it was incomplete and in a disorganized state. Neil Slaven gives an account that at least allows that some of the material in the final version was recorded earlier, in Los Angeles; but he also implies that some of the orchestral passages were recorded in New York, which now appears not to be the case.Footnote 21 David Walley refers to “the mess of tapes” that Zappa got back from Capitol and the ineptitude of Capitol's engineers allegedly demonstrated by the condition of these tapes.Footnote 22 This account is cited and paraphrased by Michael Gray in his own book;Footnote 23 James Borders, in turn, cites both Walley and Gray and adds the further claim that the entire Lumpy Gravy was “recorded over an eleven-day stretch at New York's Apostolic Studios in February 1967,” with “a pick-up ensemble of fifty-one musicians”—apparently an inference from the highly misleading notice on the original Lumpy Gravy sleeve, faithfully reproduced in the CD reissues, that “this album was recorded in February of 1967.”Footnote 24 Such a feat would have been impossible anyway, because Zappa was nowhere near New York or Apostolic Studios at that time. (What was recorded in February 1967, we now can be reasonably certain, was the [first?] studio orchestra session at Capitol, probably with no strings except basses, as shown below.) It now appears that, although by the time Zappa did go to New York in mid-1967 Lumpy Gravy still was very far from completion in the form we know it now, all of the orchestral recordings were either already in his possession, waiting to be used, or were eventually sent to him there.

It is actually easier to work backwards from the final version of Lumpy Gravy, discussing the two “sketch versions,” as I will call them for convenience, in reverse-chronological order. What is most likely the May 1967 Capitol master (called “Lumpy Gravy [Primordial]” in the sleeve notes;Footnote 25 hereafter, in this essay, sketch version 2) is significantly shorter than the final version (22:37 compared to 31:40) and lacks much of the material that gives the final version its crucial character—such as the piano voices, the concrète treatments, and the pop allusions and intrusions. In fact, it appears to consist entirely of music from the recording sessions for the studio orchestra assembled at Capitol in February and March. It is markedly different from the final version in other ways as well: With the exception of a few passages, everything in sketch version 2 can be found in the final version, but often in radically different order and sometimes in different edits, takes, and/or arrangements. Also, the explicit designation of nine short movements in sketch version 2, as if a suite, gives a very different sense of continuity from that of the two larger parts, each just under sixteen minutes, that occupy Sides 1 and 2 of the final version.

Table 2 collates the material of sketch version 2 with its various locations in the final version. From this table, one can see that some features of what Lumpy Gravy would finally become were in fact already present in May 1967. Disregarding, for the time being, the cartoonish opening (which functions as kind of prelude or overture) and the concluding cheesy pop arrangement of “Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance” that bracket the final version,Footnote 26 the opening of sketch version 2, with the orchestral treatment of “Oh No,” certainly resembles the final version—even if we do hear the two differently orchestrated arrangements of this tune in reverse order. Two passages notably emulative of Varèse are somewhere in the middle, in the order that they assume in the final version (and, as in the final, separated by other material)—even if their effect on the pacing of the whole is rather different in sketch version 2, as one can see from the timings given in Table 2. Further, most of the last two movements of sketch version 2 corresponds exactly (same arrangements, same edits/takes, same order) to the four minutes-plus of the final version preceding the cheesy finale.

TABLE 2. Lumpy Gravy: Reordering of Sketch Version 2 Segments in Final Version

We will never know what kind of place Lumpy Gravy would have assumed in Zappa's oeuvre today if Capitol had released sketch version 2 in 1967 (that is, of course, assuming that this recording is actually the one that Zappa delivered to them, and that they were planning to issue commercially). All we do know is that its recovery in 2009, like some kind of time capsule, makes a comparison with the final version inescapable, and it is difficult to believe that a Lumpy Gravy in this earlier form would stand with the same significance that the eventual final version does now. For one thing, there doesn't seem to be quite enough material there to justify even 22½ minutes’ duration. Large chunks of the first two movements are devoted to the same tune (“Oh No”), with scarcely any break between the two treatments and with yet a third treatment in the seventh movement; there is a nearly literal repeat of music from the third movement (0:38–1:10) in the seventh (1:22–1:45); and all but a few seconds of the fifth movement (0:03–1:41) is reused quite literally as the last music of the finale (1:49–3:27). Might Zappa have decided, in retrospect, that these duplications stretched his material too thin, creating formal problems? Might he have found other shortcomings, too, such as the somewhat monochromatic, over-earnest air of the whole production? If so, perhaps he figured that he might as well take the time to revise substantially, since a delay had already been forced on him for legal reasons. This account, although of course speculative, is consistent with Zappa's trajectory from the mid-1960s into the 1970s: Possessed of enormous energy and initiative, he was developing rapidly as musician, composer, and producer of his own records, and he was always eager to try new things—especially when new technology became available to him, such as the twelve-track equipment at Apostolic Studios in New York, where he began work on a new Mothers album, Uncle Meat, in October 1967 and where all or most of the nonorchestral components of Lumpy Gravy were recorded.Footnote 27 For these reasons, Zappa perhaps regarded the year's delay in Lumpy Gravy's release, in retrospect, as not entirely a bad thing—although, true to form, he tended to downplay the opportunity it gave him to reinvent the work in favor of pointing out the ways in which the whole episode reflected poorly on MGM.

If the “primordial” sketch version 2 seems as though it had a long way to go before becoming the final version, “How Did That Get in Here?” (hereafter, in this essay, called sketch version 1), by comparison, sounds positively prehistoric, reflecting a much earlier stage of thought about the form of the work. In this version, “Oh No” looms even larger than it does in either of the later versions, in part because it is the only music with a fixed and definite profile, and also in part because the entire form—at 25:01 actually slightly longer than sketch version 2—is suspended, as it were, between the initial presentation of “Oh No” in the opening minutes and its reprise at the end. Most of the intervening music is either quasi-improvisatory in nature, serving as transitional passages, or is given over to boogie-type grooves lasting several minutes at a stretch, with solos taken in turn by vibraphone, electric piano, trumpet, and guitar—material resembling nothing at all in the later versions. Another factor distinguishing this (apparently) earliest extant sketch from the other versions is that the studio forces assembled for the mid-February 1967Footnote 28 recording session seem not to have included any strings other than double basses. Where one might expect to hear the higher strings featured, as in the revamped orchestration of the reprised “Oh No” in the final version (a passage also present in sketch version 2), they are noticeably absent. (In fact, the coda of “Oh No,” where the violins initially assume the lead, is itself noticeably absent.Footnote 29 This coda appears to have been a late addition to the song, transplanted from an early version of “Lonely Little Girl,” a song that eventually was incorporated into We're Only in It for the Money.)Footnote 30 Some, at least, of the additional orchestral material that was recorded in mid-March may well owe its very existence to producer Nick Venet's willingness, for this second go-round, to hire the additional players (the string section listed on the LP sleeve of Lumpy Gravy numbers nineteen players in all, besides the five bassists who are listed separately).

Nevertheless, there are some links between sketch version 1 and the later versions, apart from “Oh No.” One can be heard through the idioms of modern jazz, which have a stronger presence in sketch version 1 (especially from about the midpoint on) than in the later versions, where they persist more as a texture, notably in the employment of piano-trio combinations and vibraphone solos. The opening music of sketch version 1 (0:00–0:24, repeated 1:12–1:36) has been quite thoroughly recomposed and extended to become the music that opens the third movement, “Up & Down,” of sketch version 2 (0:00–0:38), which in turn is taken over literally to Part One of the final version, where it becomes a kind of interlude (13:08–13:46).Footnote 31 What comes in between (0:24–1:12) in sketch version 1 is a different take, in a longer edit, of the music that opens “Gum Joy,” the second movement of sketch version 2, where it is used as an introduction to “Oh No”—the same purpose to which it is put in the final version (I/1:38–2:09). Finally, from 15:30 or so onward in sketch version 1, several recognizable passages from various movements (of sketch version 2) and Part Two (of the final version) crop up, sometimes in fragmentary form. This last set of correspondences is compiled in Table 3.

TABLE 3. Lumpy Gravy: Passages in Sketch Version 1 Incorporated into Later Versions (Partial List)

Finally, two features of the finished version deserve further comment: the cartoonish overture and the cheesy finale, since not a trace of either is to be found in the sketch versions. In fact, the orchestra heard in the overture sounds quite different from the Capitol ensemble, and the instrumentation of the finale is quite definitely pop (not orchestral). If these sections of Lumpy Gravy did not originate in the Capitol sessions, where did they come from? Without additional documentary evidence, it is impossible to say for certain—but one hypothesis worth considering is that they were culled from recordings made a good deal earlier than 1967, perhaps tapes that Zappa had saved from his early film-music projects (The World's Greatest Sinner, 1961; Run Home Slow, 1962–63), or from his years of association with Paul Buff's Pal Studio in Cucamonga (which Zappa eventually bought and renamed Studio Z) in the early 1960s.

From comparison of the three versions, we get some idea of how Zappa's compositional process for this work might have developed: From a structure that was essentially an arch between pillars constituted by an old tune of his (“Oh No” in later nomenclature) and its reprise—that is, sketch version 1—Zappa's conception evolved, in sketch version 2, into a more complex, suite-like form in which “Oh No” still played a major role (a rather lopsidedly dominant role, in fact) but was intertwined with a number of other components, a few of which, mainly through literal repetition, received more emphasis than others. The resulting problems of balance, mentioned earlier, were successfully addressed in the final version, where “Oh No” and its reprise are confined to not much more than the first half of Part One, never to be heard again; moreover, the incidence of literal repetition is greatly reduced, and the sonic landscape is greatly enriched with the addition of the piano voices, concrète treatments, and other materials linked in segue rather than in discrete movements.

In short, Lumpy Gravy, together with its sketches, brilliantly illustrates the avant-garde–inflected modernism that was a thriving part of Zappa's aesthetic in the late 1960s: The components are sometimes composed, sometimes improvised, but even the composed parts are in flux, subject to rescoring, rearrangement, abridgment, and extension—and, especially, reordering, together with a great deal of other material (in the final version), some of which was arrived at essentially by chance, that offers many opportunities for juxtapositions ranging from startling incongruities to beautiful accidents.Footnote 32 The whole production is imbued with an adventurous spirit and comes across as cheerfully irreverent, even if the subject material occasionally evinces a more somber hue.

Although this more somber hue is easy to overlook, with so many things competing for one's attention in the heterogeneous mix of materials, it needs to be noticed as background color to the piano people's situation, since in that function it also alludes, partly by way of contrast, to the hippies’ victimization in Lumpy Gravy's dark sister album, We're Only in It for the Money. That is, both groups exist under threatening conditions, but the latter is more severely endangered: Whereas the characters in Lumpy Gravy are safely sheltered and out of immediate danger in their piano, the hippies in Money are out on the street, prey not only to their own naïveté in the face of the commercial forces that are exploiting the “Summer of Love” and all the trappings of the so-called counterculture for whatever profit can be squeezed out of them, but also to the hostility emanating from a rigidly conformist society that would like to hurt them, lock them up, or worse for looking and behaving as they do. So, at least, their plight appeared in the rather feverishly paranoid vision conjured up by Zappa on the Money album. It was, after all, an era in which paranoia ran rampant—enough so as to provoke Zappa into the “unpleasant premonitions,” as he referred to them, brought to musical depiction in the last track on that album, “The Chrome-Plated Megaphone of Destiny.” This fairly lengthy (6′30″) finale to an album made up mostly of songs is essentially a concrète piece, with no lyric content whatsoever—and as such constitutes another sort of link to Lumpy Gravy, in that Zappa's fellow Mothers had nothing to do with its performance. In his liner notes, Zappa asks the listener to imagine that “you are a guest at Camp Reagan,” a World War II–style internment camp remade along the lines of the ghastly penal colony in Kafka's famous story, “as part of the FINAL SOLUTION to the NON-CONFORMIST (hippy?) problem.” He continues:

You might allow yourself (regardless of the length of your hair or how you feel about greedy wars and paid assassins) to imagine . . . [that] you have been invited to try out a wonderful new RECREATIONAL DEVICE designed by the Human Factors Engineering Lab as a method of relieving tension & pent-up hostilities among the members of the camp staff. . . . At the end of the piece the name of YOUR CRIME will be carved on your back.Footnote 33

We're Only in It for the Money would be a fit subject for an essay all by itself. Brief attention has been paid to it here, though, mainly for the sake of pointing out that there is a certain amount of leakage between it and Lumpy Gravy that shows up in various ways—some of them rather funny, others not funny at all—that will have an impact on the reappearance of the piano people in Zappa's later work. Zappa's peculiar genius for playing up the absurd side of even serious situations, or for making a serious point in the midst of a routine designed essentially for laughs, has a lot to do, not only with the relationship between the two sister albums consecutively produced during the 1960s, but also with the shape eventually taken by Civilization Phaze III in the 1990s.

This is not to say, however, that Lumpy Gravy and Money can be reduced to two sides of the same coin. That Lumpy Gravy was made with very little participation from the Mothers has both practical and symbolic significance: As to the former, Zappa needed studio musicians who were well trained in reading staff notation to get the results he wanted; as to the latter, he needed to present himself to the musical world as a composer in a more explicit way than he ever could as the leader of an R&B band with freaky predilections. Ultimately the similarities of all his orchestral, that is, “serious,” musical endeavors (in which he was usually not a performer) to his work with his own bands (in which he led and performed) outweigh the differences between them.Footnote 34 In the present instance, however, the differences are more important, precisely because it was the first time Zappa had made an album that was unambiguously all his own. Moreover, given his relatively young age (twenty-six), his self-taught status, and his idolization of earlier twentieth-century composers, it would not be surprising if he had approached the occasion in as naïve a state in certain respects as that of the hippies he satirized in Money. A careful look at the front cover is instructive. It bears the heading: “Francis Vincent Zappa conducts LUMPY GRAVY,” followed by the text already quoted above (“A curiously inconsistent piece . . .”). The composer scowls at the camera through a mop of hair and a couple of days’ growth of stubble on the part of his face that isn't already occupied by his signature mustache-with-below-the-lip-patch; he's wearing a PIPCO T-shirt, and his feet, which are just barely visible, are shod in tennis shoes without socks—but he's standing on a podium. Zappa thereby puts himself in a quite deliberately absurd and unpretentious light, which clashes amusingly with the use of his full “formal” name while at the same time perfectly matching the title of his album.Footnote 35 The studied nonchalance, though, only makes it the more obvious that he is also thrilled with the whole thing. (Even to attempt a ballet is to lay claim to the same territory as Stravinsky's, after all.)Footnote 36

Having the opportunity to make a record of his own music, with real (i.e., notation-reading) musicians to play it, and without any real concern for its likely popularity or even marketability: This was true freedom, like entering another world, removed if only temporarily from the mundane problems of generating enough income to keep a band together. In short, this effort was toward his future reputation as a composer. One might say that when Zappa walked into the recording studio with his Lumpy Gravy musicians, he entered a kind of enchanted state. The idea of the recording studio as refuge, where he could perpetuate something of that experience of enchantment, would tend to explain a good deal about Zappa's behavior later, when he built his own studio at his home and ventured forth only intermittently—and with ever greater reluctance as time went on—to tour in support of his latest album. Under the circumstances, then, we might see Zappa's refugee piano people as under a kind of enchantment as well: removed from the unpleasant real world; safe, as long as they remained within its protective confines, from the vilification and abuse that lay in wait just outside. It would be hard, too, to imagine a more perfectly chosen haven than the resonant space of that enduring, physically substantial symbol of serious musical art, the grand piano. (In fact, we soon find out that some of the present denizens of this space have tried living elsewhere—in a drum, for instance—and have found the accommodations far less satisfactory. “Drums are too noisy, you got no corners to hide in,” says the character known as Louis the Turkey at one point.) Finally, the piano people's situation is all the more enchanted for being enigmatically and fragmentarily revealed. There's no real narrative; as noted before, in the context of this overloaded work, too much else is going on for any coherent story to be told.

III

We might never have heard anything further about the piano people, but for the fact that their strange, incompletely worked-out story apparently stuck at the back of Zappa's mind for the next twenty-five years or so, until he finally found a use for it again, in one of the most ambitious works he would ever complete: Civilization Phaze III. It's “phase three,” of course, whether Money was phase one of Lumpy Gravy or the other way around.Footnote 37 In any case, it could not have been very easy to pick up the thread after a quarter-century had passed, especially the kind of quarter-century that Zappa had experienced. To say that he'd had his share of disappointments and disasters would be putting it mildly. A list of the principal ones would include major fallings-out with two record companies and one long-time manager, resulting in several protracted and expensive lawsuits; a number of abortive “orchestral ventures” and a few other recording projects with orchestral forces that garnered mixed results, all at enormous cost;Footnote 38 a quixotic campaign against the initiative mounted by the Parents’ Music Resource Center to place “Parental Advisory” stickers on pop records with language or themes deemed unsuitable for minors; a potentially lucrative tour with a large band that self-destructed less than halfway through its planned run, mainly owing to Zappa's distraction by nonmusical concerns; and, finally, the most devastating blow of all, diagnosis of well-advanced prostate cancer in 1990.

Fortunately, these years weren't a time of unmitigated gloom either. Zappa continued to compose, perform, and record at a remarkable pace, and enjoyed a measure of both artistic and commercial success; among the brightest spots were his discovery of the Synclavier in the mid-1980s, and his and the Ensemble Modern's discovery of each other in the early 1990s. These two developments in particular, together with the advent of digital recording and editing, played crucial roles in reviving the piano people. Zappa's account of how it happened picks up here from the end of the previously quoted passage in which he mentions that some of this recorded dialogue material was used in Lumpy Gravy:

The rest of it sat in my tape vault for decades, waiting for the glorious day when audio science would develop tools which might allow for its resurrection.

In Lumpy Gravy, the spoken material was intercut with sound effects, electronic textures, and orchestral recordings of short pieces, recorded at Capitol Studios, Hollywood, autumn 1966. These were all two-track razor-blade edits. The process took about nine months. Because all the dialog had been recorded in (to borrow a phrase from “Evelyn, a Modified Dog”) “pan-chromatic resonance and other highly ambient domains,” it was not always possible to make certain edits sound convincing, since the ambience would vanish disturbingly at the edit point. This severely limited my ability to create the illusion that certain groups of speakers, recorded on different days, were talking to each other. As a result, what emerged from the texts was a vague plot regarding pigs and ponies, threatening the lives of characters who inhabit a large piano.

A new generation of piano people . . . were recorded in a Bösendorfer Imperial at UMRK [Zappa's home studio, the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen] during the summer of 1991. By that time, digital editing technology had solved the ambience hang-over problem, finally making it possible to combine their fantasies in a more coherent way with the original recordings from 1967.Footnote 39

Some support for the idea that Civilization Phaze III is a kind of Lumpy Gravy redux can be found in features held in common on the level of overall form. Both are in two parts (called “Acts” in Civilization) of nearly equal duration; in both, Zappa has weighted the running time of the first half substantially in favor of music and has tended to keep it separate from spoken material, both in relatively large chunks, while in the second half he has increased the proportion of spoken material to music and has also increased the number of shorter text fragments. (In Act Two of Civilization, in fact, some of the music is heard simultaneously with stretches of dialogue, as if in accompaniment to them.) Both works begin, after a short spoken segment, with a substantial instrumental movement in the character of an overture; Part One (Lumpy) and Act One (Civilization) conclude with an even more substantial movement; and Part Two and Act Two conclude with music (in the later work including, as coda, a collage of urban environmental sounds). Even though the lengthy concluding “N-Lite” of Act One and “Dio Fa,” “Beat the Reaper,” and “Waffenspiel” of Act Two of Civilization skew the proportions somewhat, making it less obvious that (for example) up until the beginning of “Dio Fa” in Act Two nearly equal time is given to music and to spoken material, a basic resemblance between the two works is clear enough in this respect.Footnote 40

The other, more specific linkage—the piano-interior conversations that Zappa taped back in 1967—is of crucial importance not only because so much more of this material is incorporated into Civilization than was used in Lumpy Gravy, but also because several substantial excerpts from the earlier work appear again in the later one, lengthened by the restoration of material cut out at the beginning, at the end, or in the middle for their placement in Lumpy. From these reuses, the impression naturally develops that “the same story” is being told over again, in a more fully fleshed-out form and with a new installment in Act Two, as a second cast of characters appears on the scene.Footnote 41

Could one say, then, that Civilization is an improvement, in artistic terms, over Lumpy Gravy? Zappa does seem to imply this judgment in the text quoted above, even though he doesn't express it in so many words. Nevertheless, whether or not he was actually dissatisfied with Lumpy Gravy at the time he finished it—and one would tend to doubt that he was—the mysteriously incomplete story of the piano people and the fluctuating sonic ambience of the recording were probably not perceived as deficiencies by most listeners at the time.Footnote 42 Speaking for this listener, at any rate, I can say that the record came across at the time of its release as something that was not precisely worked out in every detail, but that worked nonetheless, mainly because its general outlines were so interesting and the local accidents, if that's what they were, lent a raffish, brash unpredictability to a whole that was, in almost every respect, carefully assembled.

By drawing our attention to the technical improvements, Zappa has somewhat obscured the fact that in other, more important respects he has produced something very different in this late work, the last major project he completed before his death in December 1993. (It was released only posthumously, late in 1994.) The work that unfolds around the piano people this time reflects a complete revision in aesthetic stance; over the intervening decades, Zappa's tastes have changed. Whether he regarded the quirky, jump-cut, crazy-quilt style of Lumpy Gravy as passé, or technologically primitive, or simply a naïve phase that he had gone through at an earlier point in his development, by the 1990s he had had enough of emulating the mid-century avant-garde and has turned out a composition of a much more conservative stamp: an opera-pantomime, as Zappa calls it, four times the length of Lumpy Gravy, stylistically quite uniform, with no singing but with a very elaborate scenario and complete script laid out in full in the booklet accompanying the CDs. The music ranges from brief interludes (some played simultaneously with the dialogue) to lengthy “concerted” movements composed for the Synclavier, or the Ensemble Modern, or a digitally engineered combination of the two—with not a detail left to chance. Contributing to the reader/listener's impression that Civilization is a more monumental work in a conventional, art-music sense is the inclusion in the scenario of specific cues for visual realization: All of the instrumental sections are paired with descriptions of dance routines. (In this respect, then, Civilization might also be advertised as an improvement: If Lumpy Gravy was not quite a ballet, the newer work, Zappa implies, is quite worthy of being realized as one.)Footnote 43

Despite the occasional touches of humor and the overall grotesquerie, the atmosphere of Civilization is pretty bleak. The piano has lost its enchanted aura; it is now simply an ark, from which (it now appears) there is no hope of ever escaping, since, as Zappa tells us, “the external evils have only gotten worse” since we last met up with the piano's inhabitants. The scenario for “N-Lite,” the six-movement suite that concludes Act One, reads as follows: “This dance shows the exterior world crushed by evil science, ecological disaster, political failure, justice denied, and religious stupidity.”Footnote 44 Not even Jesus, who suddenly appears in the last movement of “N-Lite,” can redeem the situation: He is compelled to retreat into the piano after witnessing the terrible mess that a group of creationists have made of his parables. (Also detracting from the piano's allure is the fact that it has become a much more crowded place, with the arrival of a whole new crop of refugees.)

The story, too, has lost its enigmatic charm. It's still not much of a narrative, because nothing ever happens to these characters trapped outside of time; but now we are compelled to attend to it as the dramatic focus of the work, and the details of this plot are not enough to sustain interest. The achronic aspect it wore in Lumpy Gravy has been retained, but instead of the air of mystery lent by this quality in the earlier work, the effect in Civilization is simply odd—especially for anyone familiar with Lumpy. For example, the conversation in Act One of Civilization between Louis the Turkey and Roy entitled “A Very Nice Body,” following as it does the instrumental movement entitled “Reagan at Bitburg,” seems to focus on Reagan's “personal attributes” (as the scenario has it) and the fact that the two characters miss his presence in public life. However, Reagan's infamous laying of a wreath at the SS officers’ memorial happened, of course, while he was president, long after the original Lumpy Gravy conversations were recorded; back in 1967, Louis and Roy would have been talking instead about Motorhead, who had left the piano and who they wished would come back. (This reference to Motorhead is eventually made explicit, but not until the beginning of Act Two. Since Motorhead is absent from Civilization, except in the form of these references, only the listener already familiar with Lumpy Gravy will have any idea of who he is.) In Act Two, where the hippies of 1967 are joined by two Californians from ca. 1990 and various other characters speaking in a Babel of European languages (among them French, Italian, German, and Turkish), any attempt at plot development effectively dissipates.

Perhaps it is this lack of a real plot—this time exposed at such length—that leads Zappa occasionally to incorporate his own voice, giving the “talk-back” cues that were kept inaudible in Lumpy Gravy. It is somewhat odd to hear them at first, but eventually one can see that their presence in the mix is perfectly in keeping with Zappa's perceived need to make the story more definite in its details, and perhaps also to assert his role as the master ventriloquist.Footnote 45 (Part of making the story more definite is also making it more of a “construction,” a contrivance.) In the following excerpt, the piano people are discussing the pigs’ music; the line “The smoke stands still” is delivered in Zappa's actual voice:

Monica: Have you ever heard their band?

Spider: I don't understand it though. Their band. I don't understand . . .

Monica: I . . . I don't think they understand it either.

Spider: What? The smoke?

John and Monica: The band!

Spider: The band doesn't understand what?

Monica: Did you know that?

F.Z.: The smoke stands still.

John: There's some kind of thing that's giving us all these revelations . . .

Spider: Yeah, well that's the . . .

John: It's . . . It's . . . It's this funny voice . . . and he keeps telling us all these things and I . . . it . . . I just thought that before we just thought of these things . . . ya know, like just off the wall and out of our heads.

Spider: No, that's religious superstition.Footnote 46

Substituting for plot development, in a way, are the dance elements of the scenario. Since these elements register neither in the music nor in the dialogue as heard, they constitute an essentially independent thread, along which Zappa arranges his (largely) static tableaux in the form of a sociopolitical critique. Zappa's penchant for this sort of thing is nothing new—the second “underground oratorio” of Absolutely Free and most of We're Only in It for the Money were already heavily devoted to it—but his efforts at satire, often right on target, sometimes threaten to spill over (and sometimes do) into mere preachiness. In Civilization, with only the hypothetical realization of vaguely sketched choreography to go on, the reader of the scenario is inevitably left wondering what the real purpose of these choreographic descriptions could be. Is Civilization meant to come across as another incomplete artwork, like the unfinished movie of Uncle Meat?

Two examples will suffice to lend an impression of the whole:

[“Xmas Values,” Act One, No. 9] Lights come up on the left and right tableau sets, each featuring a Christmas tree. The left set shows the yuppie dancers mutating into pigs. The right set has them mutating into ponies. As the transformations are completed, the two groups leave home and smash each other in the third tableau (shopping mall) area.

[“Dio Fa,” Disc 2, Track 19] The piano exterior area is now inhabited by dancers-as-ponies, wearing Catholic religious garments. The Pig Pope is dead. He is upside down now, and his wagon is being towed away. The new Pony Pope is being adored.Footnote 47

There is an obvious intent here to make more of the pigs and ponies than the fearsome (but unseen) monsters of Lumpy Gravy. Yet they seem to symbolize nothing definite—unless, perhaps, they are stand-ins for Democrats and Republicans, which Zappa, with his usual cynicism about politics, tended to regard as two sides of the same counterfeit coin (it wouldn't matter which was which, obviously).Footnote 48

In the end, though, it's not the additions to the cast of piano people, or the scenario with its depictions of the horrors of the world outside, that are likely to persuade the listener that Civilization Phaze III is not simply a gussied-up retake on Lumpy Gravy; it's the music we hear in the newer work, so strikingly different from that of the older one. What has happened to Zappa's style in the intervening years?

Certainly, he has developed as a composer. The segments of Lumpy Gravy for studio orchestra reveal a very tenuously established technique, still largely confined to imitation (with uneven results) of early-twentieth-century art-music composers or (more successfully) TV-show themes or movie-soundtrack filler. Zappa yearned to be able to do better and, thanks to the experience he gained in subsequent decades, eventually did do better. Viewed chronologically, the record of his compositional work for (more-or-less) conventional ensembles of (mostly) acoustic instruments shows steadily increasing dexterity and confidence, as well as an increasing consistency of style, beginning with the score for his film 200 Motels (1971) and continuing with his reworking of some extractions from it together with new compositions, all of which went into the 1983 sessions with the London Symphony Orchestra (issued in two volumes: 1983, 1987). Then come the chamber ensemble tracks on The Perfect Stranger, recorded by Pierre Boulez and the Ensemble Intercontemporain (1984); the large three-movement piece Sinister Footwear, performed by a student orchestra at Berkeley (also in 1984); and, finally, the Ensemble Modern's Yellow Shark concerts and recording of the early 1990s. Meanwhile, Zappa's work with his amplified and often eclectically constituted bands continued at a prolific pace. This side of his career constituted musical experience as well, and there was much more of it than the other kind: Zappa's maturation as a composer was never driven exclusively or even primarily by his work with acoustic concert ensembles. Nevertheless, his style of writing for such instrumental forces is distinctive, with a quality that has been dubbed “anti-fetishist” for its lack of conformity to the conventions of orchestration, including doubling, spacing, and voice leading.Footnote 49 Some of these characteristics clearly owe a lot to the norms of arrangement in rock and pop, where the guitar is at least as likely as the keyboard to be the frame of reference, and where relatively recent innovations such as the tracking-chord features of synthesizers have provided a route to great density and apparent activity without promoting truly independent lines, as in (old-fashioned) counterpoint.

Formally speaking, too, Zappa's writing for groups apart from his own bands was considerably affected by his experience as a performing guitarist, especially as his fluency as a soloist increased. After the original Mothers disbanded, Zappa had recourse to the head-plus-solos format of jazz ever more frequently, something that inevitably has led some critics to classify him as a “fusion” artist.Footnote 50 Head plus solos, as such, figured very little in his work for orchestras or chamber ensembles; improvisation as a general technique, however, seems to have become very important to all of Zappa's compositional endeavors—and, when it was applied to his work with acoustic concert ensembles, where the music needed to be fully written out, it often produced rather odd results. Written-out improvisation, if conceived of as transcription, can sound cramped and “studied,” especially if the emphasis is on rendering the rhythmic intricacies with absolute fidelity—something that Zappa and transcribers such as Steve Vai did often try to do. Of likely relevance as well is the fact that what might work to convincing effect as a spontaneous creation can start to sound, if fixed exactly, rather routine after a while, even if rendered with perfect fluency. One might also venture to observe that the longer the improvisation, the more its transferal into a nonimprovising medium is likely to pose problems. Circumstances of this sort serve to explain, in part, the peculiarly “airless” quality of much of Zappa's work for acoustic concert ensembles, especially the larger ones and especially in situations where no rhythm section is used to enforce a steady, underlying groove of at least minimal coherence.

Some of the same shortcomings are evident in the music for Civilization, although it must be said that the instrumental tracks, on the whole, are quite skillfully done, and many of them can easily stand on their independent compositional merits. As if in demonstration of that fact, the Ensemble Modern chose two, “Put a Motor in Yourself” and “A Pig with Wings” (in all-acoustic arrangements by Ali N. Askin), for its recent all-Zappa album, Greggery Peccary and Other Persuasions (2004). “Put a Motor in Yourself” is particularly successful, with its jittery groove and burbling, interconnected and recurrent woodwind motifs (alternating, in Zappa's original realization, with more overtly synthesized material) that metamorphose about two-thirds of the way through this piece of slightly more than five minutes’ duration into a more broadly constructed ensemble tutti without losing the underlying jittery rhythm. Others would have made equally plausible selections for the Modern's album, such as “Reagan at Bitburg,” with its doom-laden opening and conclusion bracketing faster music that never entirely escapes the lugubrious undercurrent of low, slow tones; the faster music is ultimately dragged down and suppressed. “Amnerika” juxtaposes an irregularly pulsating accompaniment in its lower voices with a generally slower-moving, plaintive melody, essentially continuous for the entire three-minute length of the piece, that in the Synclavier realization sounds as though it is being played in unison by multiple overlapping high woodwinds. Overall, Zappa has achieved striking variety in his textures, rhythmic characters, and tonal language: Every piece is distinctly different from the others, although they are all obviously of a piece stylistically—and also similar in mood, which is extremely dark. As for “N-Lite,” an eighteen-minute suite of six movements played in segue, or “Beat the Reaper,” of nearly equal duration at 15½ minutes, they seem, like many of Zappa's previous efforts in such longer forms, somewhat sprawling and not quite coherent formally. However, perhaps exactly what is needed in these cases is an all-acoustic realization by musicians with both an aesthetic sympathy for this music and the requisite technical command of contemporary idioms to put it across. The Synclavier, for all its virtues, lends a rather mechanical affect to much of Zappa's late output.Footnote 51

Zappa often complained, from the late 1960s on, that he couldn't find musicians who could play his notated music exactly as he had intended it to be heard. Being almost entirely an autodidact, he may not have realized that the perceived shortcomings of his bandmates and hired musicians had something to do with the notation itself, which often presented nearly insuperable rhythmic challenges. The Synclavier certainly solved the problem of exact rendering, if through the agency of a nonhuman performer; the Ensemble Modern met him more than half way, bringing with their remarkable virtuosity a constructive attitude and a supportive working environment for Zappa, in which he apparently began to be persuaded that selective renotation of his impossible rhythms did not necessarily constitute a compromise to his artistic integrity.Footnote 52

With these technical difficulties of performance at least provisionally conquered, we seem to have the makings of a happy ending, destined to grant even a composer stricken with a fatal illness some measure of fulfillment. That the conclusion to Zappa's career does not come across that way is partly owing to the fact that no quantity of accomplishments would ever be enough for him: His mad scramble to finish as many projects as possible in his final year of life, Civilization among them, is sufficient testimony to this perpetual dissatisfaction. It may be even more owing, though, to a quality that becomes ever harder to ignore in listening to Civilization itself: that getting through it is kind of a chore. Frankly, and especially during Act Two, it becomes boring, in a way that Lumpy Gravy never does. (Although, as noted earlier, the general strategy of Act Two of Civilization, with its shorter instrumental passages broken up more frequently with spoken material, is similar to that of Part Two of Lumpy Gravy, the effect is very different, possibly owing to Zappa's decision to have some of the music of Act Two heard simultaneously with dialog, inevitably pushing that music into a subordinate role until it re-emerges as the main focus in the final numbers.) Perhaps, at two hours’ duration, Civilization is just too long; perhaps the unrelieved pessimism, which the brief flashes of humor do little to alleviate, is to blame—but more likely, it's that the static plot, as limned by both the dialogue and the dance, is mirrored in the music. However stylistically consistent (yet attractively varied) the individual pieces are, they remain separate, with no arc of development to link them in sequence or, for that matter, in any other way. To return to a point made earlier: If Civilization comes across as an unfinished or only provisionally finished work, this quality may in fact not stem from any intent on the composer's part—for this work is not “open,” in the avant-garde sense, like some of its predecessors, Lumpy Gravy among them. Rather, the feeling Civilization lends of being unfinished more likely arises from both physical and psychological exhaustion. The physical part, under Zappa's circumstances at the time, is easy to understand; the psychological requires further exploration.

Previous extended works by Zappa such as Joe's Garage (1979–80) and Thing-Fish (1984) were equally pessimistic, but they also embodied real rage against the ugliness and stupidity of contemporary life and, concomitantly, an urge to bring his listeners to the realization that things don't have to be this way. In Civilization, by contrast, Zappa watches the death throes of contemporary civilization in a resigned state, having effectively given up hope that disaster can be staved off. At the same time, and equally resignedly, he contemplates the imminent end of his own physical life and his work as a creative artist. It would not be surprising if the personal and the global became, for him, at least symbolically connected. Nor would it be surprising if these meditations on mortality, coupled with the ebbing of his physical stamina, began to interfere substantially with the composing he had left to do.

If this conjecture comes at all close to the truth, it may support the assertion that Zappa, artistically speaking, had reached a creative impasse even as he began to get the kind of performances he had always dreamed of, thanks to technological innovations and the advent of contemporary-music ensembles made up of ferociously talented players young enough to be thrilled at the prospect of playing his brand of “crossover.” It may also afford some insight into his decision to revisit those old piano-voice tapes for his Civilization project: Either he was trying to recapture some of the magic, from back in the days when it was all new and fun, or he was deliberately and rather sourly admitting that all the fun had slipped away—presenting us, as proof, with a last, massive, truly serious (despite a few touches of macabre humor) and definitely not avant-garde work. Perhaps these two possibilities actually represent successive stages that he went through during the conception and realization of the project.

As to the macabre humor, one classically Zappanian instance at the end of Civilization has an edge to it that he rarely, if ever, achieved in any earlier piece. “Beat the Reaper,” the penultimate track, is to be accompanied by depiction in dance of “social actions,” which “illustrate the current fetish for life-extending or ‘youthening’ trends, including meditation, bizarre diets, pill and algae consumption, violent aerobics, ‘THE EASY GLIDER,’ stair-steppers, etc.” All rather heavy-handed satire—but in the finale, “Waffenspiel,” comes a kind of diabolus ex machina: the Reaper shows up, to the sound of a car door slamming, “much to the dismay of the dancers in the previous piece,” to take them away. “Act Two ends with a large model of a crop-dusting plane, spraying the audience with a toxic substance.”Footnote 53 So everyone dies, whether they have lived healthy lives or not—a last jest from the workaholic, religiously nonexercising, chain-smoking composer who will soon be joining them.

It may seem just too neat a correspondence, the “disenchantment” of the piano people after twenty-five years and the putative exhaustion of Zappa's ability to grow musically in ways that meant something to him. One might ask: Did he really show any sign of having intended to convey such a self-analysis? Certainly, there is no overt evidence, but one brief stretch of dialogue—the last, in fact, heard in Civilization—offers a possible clue:

John: We don't even understand our own music.

Spider: It doesn't . . . does it matter whether we understand it? At least it'll give us . . . strength.

John: I know but maybe we could get into it more if we understood it.

Spider: We'd get more strength from it if we understood it?

John: Yeah.

Spider: No, I don't think so, because—see I think, I think our strength comes from our uncertainty. If we understood it we'd be bored with it and then we couldn't gather any strength from it.

John: Like if we knew about our music one of us might talk and then that would be the end of that.Footnote 54

If this voice is really Zappa's—and it could be his, both of them in fact, since every ventriloquist is, in the end, talking to himself—he is plausibly revealed here as being torn creatively between the need to know—that is, to be able to realize in sound anything he was capable of imagining—and the need to remain unknowing—that is, in some ways innocent, with worlds yet to conquer. The almost wistful quality of this conversation suggests that, in the end, Zappa felt he had learned too much about the avant-garde and its obverse, and had come to realize that the commercialism of fashion is as much a force in the world of contemporary art music as it is in pop, erasing his one-time ambition to take them both by storm.