Introduction

After almost a quarter of a century, Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997) is one of the most cited papers in management, yet there is continued debate as to its theoretical and practical implications (e.g. Barreto, Reference Barreto2010), particularly in relation to transformation. Theories on the transformation of an organization, industry, or a field have traditionally focused on explaining how structures within them affect organizational processes. Particular attention has been given to the conforming behavior of organizations' capabilities and routines. Our research responds to a call by Hallberg and Felin (Reference Hallberg and Felin2020) who point out that past research provides only a limited insight into the underlying dynamics of change, hence being unable to explain varying outcomes of seemingly similar (dynamic) capabilities. In this study, we are particularly interested in how it is possible to build a deeper understanding of the development of a higher-order entity by analyzing capabilities that exist to promote change. Nelson and Winter (Reference Nelson and Winter1982) proposed that certain dynamic capabilities or metaroutines, specific to individual organizations, promote innovation, and that the relationship between these concepts should be examined. Despite this, the theory has been criticized for its unclear practical implications (e.g., Arend & Bromiley, Reference Arend and Bromiley2009). While a transformation is often viewed to have occurred as a result of putting resources into action by means of certain dynamic capabilities (Winter, Reference Winter2003), little consideration has been given in the literature to learn how the transformation should be managed and why it actually takes place. This lack of available operationalization has been considered to be due to the unclear microfoundations (Barreto, Reference Barreto2010; Prieto, Revilla, & Rodríguez-Prado, Reference Prieto, Revilla and Rodríguez-Prado2009) and therefore that is the research approach that we have taken. Our overall research question considers how can we differentiate between capabilities that lead to transformation and capabilities that support change but do not transform?

A starting point in our research was the notion that capabilities can be divided into two categories, first- and second-order capacities, and that the latter are defined, following the literature, as dynamic capabilities or metaroutines that are designed to transform existing operational routines or to create new ones. To better understand such change processes, we have conducted a phenomenon-driven research study where we explore the roles of dynamic capabilities and their highly varying outcomes in the implementation of customer data use in Tesco, the largest retailer in the United Kingdom. Based on our findings, we propose that it is fruitful to differentiate between capabilities that are truly transformational, and those that coordinate or adapt operations – leading to incremental change, rather than transformation.

By observing and analyzing selected capabilities that were considered dynamic (i.e. having a higher-order role), our research results in three important contributions to the literature: (1) we develop a more microlevel understanding on the role of capabilities in change and provide a more practical definition and taxonomy of capabilities, depending on their role in the process of change. Understanding the mechanisms of change can enhance our knowledge of strategy, operations, and innovation management, (2) we relate the interdependence of different capabilities to varying (dynamic) outcomes (e.g. innovations and transformations), and (3) we discuss how our findings connect the so-called capabilities and routine perspectives.

Theoretical background

Since the 1990s, the need to keep pace with increasing competition has driven firms to constantly adapt, reconfigure, and recreate their resources (Arndt, Reference Arndt2019; Teece & Leih, Reference Teece and Leih2016; Wang & Ahmed, Reference Wang and Ahmed2007). In such environments, the operational (i.e. first-order) capabilities that drive competitive success – such as conducting range-reviews, pricing, and the design of promotions in the retail space – quickly become outdated and so fall short of ensuring success (Felin & Powell, Reference Felin and Powell2016; Paavola, Reference Paavola2021). The notion of dynamic (second-order) capabilities was originally introduced and conceived as a new framework intended to explain how organizations may gain and sustain competitive advantage in situations that place high demands on the degree of reflexivity (Day & Schoemaker, Reference Day and Schoemaker2016; Helfat & Winter, Reference Helfat and Winter2011; Teece & Pisano, Reference Teece and Pisano1994). For example, Teece (Reference Teece2012) has examined how organizations keep up with their evolving surroundings and identified the existence of types of dynamic capabilities that determine the speed, and degree to which, firm's capabilities can be ‘aligned and realigned to match the requirements and opportunities.’ For example, Zou, Guo, and Guo (Reference Zou, Guo and Guo2019) in their paper discuss how the breadth of an absorptive capacity positively impacts innovation performance. From a managerial perspective, such understanding of capabilities is considered to be an important aid for management endeavoring to combine competitive advantage with an element of future-proofing in changing environments (Deng, Liu, Gallagher, & Wu, Reference Deng, Liu, Gallagher and Wu2020; Day & Schoemaker, Reference Day and Schoemaker2016; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997).

Dynamic capabilities and their inputs are seen to include not only the higher-level routines, such as the building blocks of their execution, but also the context (e.g. skills, competencies and competitive pressures) that support their functioning (Felin, Foss, Heimeriks, & Madsen, Reference Felin, Foss, Heimeriks and Madsen2012; Frigotto & Zamarian, Reference Frigotto and Zamarian2015; Paavola, Reference Paavola2021; Winter, Reference Winter2003). More specifically, Winter (Reference Winter2003: 994) has defined them as ‘high-level routines (also known as metaroutines) that, together with its implementing input flows, confers upon an organization's management a set of decision options for producing significant outputs of a particular type.’ Overall, they are defined rather broadly as higher-order capacities that are designed to align, change or transform existing capabilities externally, or to create entirely new ones (Adler, Goldoftas, & Levine, Reference Adler, Goldoftas and Levine1999; Helfat & Winter, Reference Helfat and Winter2011; Teece, Reference Teece2012). They typically involve collecting, analyzing and interpreting data concerning the way the operating environment changes, as well as the putting of change into action (Adler, Goldoftas, & Levine, Reference Adler, Goldoftas and Levine1999; Day & Schoemaker, Reference Day and Schoemaker2016; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997; Zhou, Zhou, Feng, & Jiang, Reference Zhou, Zhou, Feng and Jiang2019).

On the other hand, the higher-order impacts driven by dynamic capabilities resemble what Van de Ven and Poole (Reference Van de Ven and Poole1995) call the process of teleological change. In accordance with the philosophical doctrine of teleology, dynamic capabilities and their implementation are determined by the specific intention and goal they are designed to accomplish (Amit & Schoemaker, Reference Amit and Schoemaker1993; Helfat & Karim, Reference Helfat and Karim2014; Van de Ven & Poole, Reference Van de Ven and Poole1995). For example, Deng et al. (Reference Deng, Liu, Gallagher and Wu2020) argue that the existence of certain capabilities that were designed to be ‘dynamic’ explain the successes in the internationalization of emerging market multinationals and their strategic choices. More specifically, they identified four distinct but related dimensions in the capabilities that drive the outcomes. Hence, the intention and transformational nature of dynamic capabilities is often understood to be determined and known a priori, even before the capabilities' performance has been observed (Helfat et al., Reference Helfat, Finkelstein, Mitchell, Peteraf, Singh, Teece and Winter2007). It has for example been shown that not only do the goals of dynamic capabilities differ, but also the impacts of the ‘same’ capabilities often vary from the intended. For example, the research by Paavola (Reference Paavola2021) has shown how seemingly similar capabilities may lead to very different outcomes depending on the surrounding circumstances, leaving space for their deeper microlevel understanding in change. In his study, he showed how the impacts of dynamic capabilities of individual tenants led to varying outcomes when the surrounding shopping center environment evolved, hence driving the evolution of the entity. Building on similar ideas, Helfat and Winter (Reference Helfat and Winter2011) have argued that ‘it is impossible to draw a bright line’ between operational and dynamic capabilities.

Our goal in this paper is to advance the microlevel understanding of the roles that capabilities may have in change. Thus, in our analysis we consider a problem where capabilities can be first-order or second-order depending on their interactions with the aim of providing a classification that may be informative to both theory and practice. Simultaneously we respond to the call by Helfat and Winter (Reference Helfat and Winter2011) to differentiate incremental (non-radical) change from transformation by building an understanding of the role of dynamic capabilities in the observed change.

Methods and data

We apply an open-ended, inductive, and exploratory theory-building approach to studying capabilities and their varying outcomes. By definition, an inductive case research strategy utilizes an empirical case or cases to build theory in an inductive fashion (Bacharach, Reference Bacharach1989; Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007). Our findings stem from a 20-year ethnography of Tesco, the largest UK retailer, and their data analytics company Dunnhumby, in the pursuit of seeking to understand the use of customer data in consumer services. In the role of a worldwide frontrunner in the use of customer data analytics, the collaboration between Tesco and their data analytics company Dunnhumby has provided a unique setting to explore the way in which customer data and related analytical capabilities have transformed an organization's retail processes.

The chosen case setting (Tesco) can be considered extreme or polar in nature as the firm's performance stood out from that of their competitors (Pettigrew, Reference Pettigrew1990). On the one hand, we can trace the broad transformational changes that the use of customer data went through over two decades; on the other hand, we have fine-grained knowledge about the functioning of the observed routines and dynamic capabilities throughout that time. Hence, we consider this well-suited for a single in-depth case study to analyze the transformational effects of capabilities (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989).

Data collection and analysis

Throughout the study, we gathered data in the form of observations, informal discussions, formal interviews, as well as various documents. Our aim was to learn as much as possible about the challenges and possibilities related to the use of customer data. The observations and informal discussions led to more targeted questions that we sought to answer through formal interviews and documentation. Our data analysis progressed in three phases: (1) observing the implementation of customer data analytics and selecting the highly varying outcomes of capabilities as the phenomenon and problem worth explaining; (2) selecting specific capabilities for further analysis based on performative observations of highly varying effects with the aim of identifying the different theoretical extremes; (3) modeling the changes in data analytics processes and then verifying the results with people that have been participating in the capability, with the aim of confirming the changes in their work.

From 1994 to 2014, the second author observed the development of Tesco's customer data program. During this period, a large number of general discussions were held with different retail experts and consultants to uncover the observed challenges related to the use of data. Based on observing the processes and the related challenges, the research was oriented toward mechanisms that, despite remaining very mechanical and recurring (data analytics), provided highly varying performative outcomes when interacting with operational processes.

Building on this work and for the particular purposes of this paper, we conducted 10 additional interviews with senior executives and management directors (referred to in our data as group A if from Dunnhumby, and B from Tesco), senior data scientists (C from Dunnhumby, and D from Tesco), data analysts (E, Tesco), suppliers (F), as well as operational employees implementing the decisions based on the data (G, Tesco). Both authors attended all interviews, which were organized during years 2014–2016.

The interviewees were asked to provide their views on the phases of change that the customer data use within Tesco have undergone, to explain and illustrate why and how the changes have happened, as well as to discuss the cause-and-effect relationships. The interviews lasted between 50 min and 2 h and resulted in approximately 10 h of recorded material. All interviews were transcribed verbatim. During the interviews, flowcharts were drawn and created to summarize the performative aspects of the identified processes. Once we had completed the interviews, we compared the material produced against one other, as well as with the previously collected primary and secondary data, and in cases of contradiction we sent the transcriptions back to the interviewees for further clarification. The interviews provided a consistent picture and no major contradictions arose. We stopped the process after 10 interviews, when no new insights emerged and we considered saturation of our particular focus to have been achieved.

The aforementioned data collection was supplemented by a large amount of documentation. Publicly available data included a complete set of historical annual reports, financial analyst reports, prior studies of the development of UK grocery retailing, and business press articles of the organizations operating in the field of UK retailing, particularly in the grocery sector. Various archive materials supplemented the publicly available data. Past presentations, organization charts and technical papers helped document the evolution of the organizations in question. Archival data is particularly suitable for longitudinal process analyses where the development of an entity is observed over a long period of time (Langley, Reference Langley1999; Langley, Smallman, Tsoukas, & Van de Ven, Reference Langley, Smallman, Tsoukas and Van de Ven2013), in this case over a period of twenty-five years.

Developments in the use of customer data in Tesco

In this section, we provide a narrative on the development of the use of customer data in Tesco over the analyzed two decades. In the narrative, we specifically focus on the developments of a range-review process that works as an illustration of the variety of ways in which capabilities can interact and result in a variety of changes.

Introducing customer data capability

From the 1970s until the early 1990s, Tesco seemed to be permanently stuck as the number two supermarket in the UK: ahead of Asda (later part of Walmart) and Safeway (now part of Morrisons), but behind Sainsbury's. Generally, Tesco had been content with copying tactics from competitors and retailers in other markets, but in 1977 Ian MacLaurin was appointed leader of innovation at Tesco, and he embarked upon modernizing the company and creating a more innovative culture (Humby, Hunt, & Phillips, Reference Humby, Hunt and Phillips2008). Up until this time, Tesco's key strategy essentially consisted of observing the sales of an individual product, determining its profitability, and obtaining products from suppliers efficiently in large quantities, a strategy known as ‘pile it high, sell it cheap’ (Corina, Reference Corina1971).

‘How cheaply can I get the product?’ Then suppliers try to build strong enough brands that the retailers have to stock them. It's always been a power struggle really between retailers and suppliers. The retailers look at the sales of individual products, calculate their profits, and make the stocking decisions. That's what the range review process in essence was all about.’ (B)

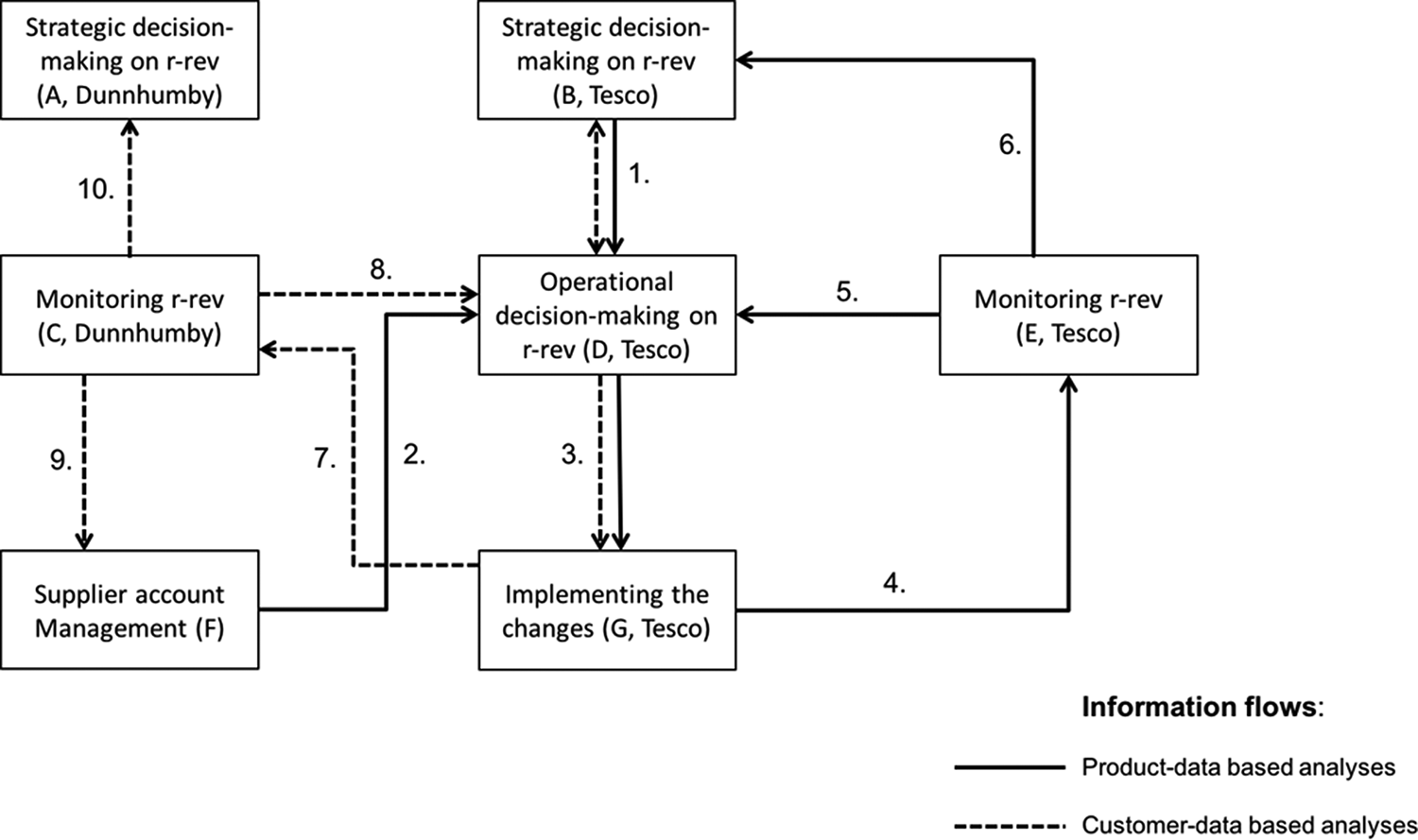

Tesco's product range review process is modeled in Figure 1. (The arrows in Figure 1 represent information flows, and are described in more detail later in Table 1, alongside details from similar Figures 2 and 3). In this process, Tesco adapted and made changes in its product range, monitored the resulting product sales data, and analyzed the results. Initially, this often happened at the level of one or a few stores, but the outcomes could then affect decision-making at the strategic level, i.e. could be applied to all stores in the same way.

Figure 1. Range review (r-rev) of Tesco prior to collaboration with Dunnhumby (further information on information flows in Table 2). Practices (boxes) of the everyday functioning of the range-review process consist of the following routines: Operational decision-making: Collecting data on what is expected to be sold (from monitoring), considering strategic metrics (presented by a member of senior manager), making decisions, confirming decisions (product manager). Implementing the changes: Collecting data (list of products and amounts), making orders, confirming orders. Monitoring range-review: Collecting data from EPOS system, plotting data to a forecasting software, comparing and contrasting data to past annual/monthly/weekly data-sets, considering product-specific variables (such as expected weather), making predictions on expected sales. Strategic decision-making: Observing overall sales development, conducting environmental assessment (comparing own sales to general customer behavior provided by e.g. AC Nielsen, identifying strengths/weaknesses with respect to competitors, identifying new possible competitive advantages.

Figure 2. Range review (r-rev) of Tesco during the active role of Dunnhumby (further information on information flows in Table 2).

Figure 3. Range review (r-rev) of Tesco during the passive role of Dunnhumby (further information on information flows in Table 2).

Table 1. Connections among the different phases of the range review process of Tesco

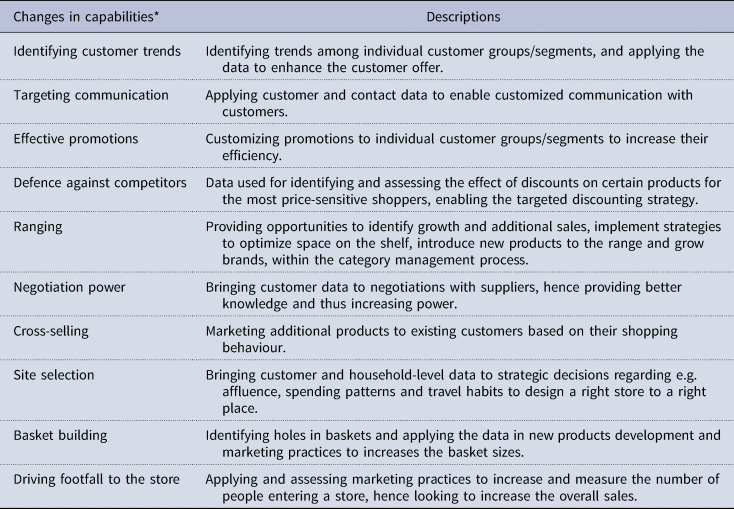

Table 2. Customer data induced changes in capabilities

*Source JP Morgan Cazenove (from Humby, Hunt, & Phillips, Reference Humby, Hunt and Phillips2008).

In the early 1990s, Tesco was running trials of several marketing programs. One of these trials, codenamed ‘Omega,’ was a new card-based customer loyalty program. Customers could sign up for their Clubcard, and by making purchases at Tesco they would accumulate points that were converted into vouchers that could be used to purchase items subsequently at Tesco. This was intended to increase customer loyalty. However, at this time, the program was not considered transformational. In general, Tesco's promotional initiatives were expected to be useful only in a certain locality or for a limited period of time, and the scope of the Clubcard trial was ‘modest even compared to other marketing pilot programs.’ (Humby, Hunt, & Phillips, Reference Humby, Hunt and Phillips2008)

Tesco's marketing staff had actively assessed retail loyalty schemes in the US, but had concluded that such schemes were unlikely to provide sufficient return on the investment. In 1993, Grant Harrison was selected to head the development of the Clubcard (Humby, Hunt, & Phillips, Reference Humby, Hunt and Phillips2008). Research that Harrison had conducted on loyalty marketing had revealed that a crucial additional benefit that could be obtained from Clubcard was the accumulation of customer data. Customers would give their names, addresses, as well as information on the size and ages of their family, and in this way, Tesco was able to identify the customer in each transaction performed at one of its stores (similar to the online identification of customers today, for example at Amazon).

During the first two months of the trial in 1993, Clubcard turned out to be a success in terms of the proportion of sales attributable to Clubcard owners in the stores participating in the trial, 60–80%. The 1% reward for their spend turned out to be a sufficient incentive for customers to sign up for the Clubcard (internal company document). However, there remained a problem; in order to gain information on individual customers and to respond to their preferences, massive amounts of transactional data needed to be processed. With the limited computing power available at the time, this was proving to be too time-consuming and expensive. To obtain the data analysis expertise they required, Tesco turned to a small consumer data analysis company named Dunnhumby. Dunnhumby showed that ‘instead of analysing all of the transactional data that had been gathered, they could analyse around 10% of it and reach conclusions that were 90–95% accurate.’ (Humby, Hunt, & Phillips, Reference Humby, Hunt and Phillips2008)

Various interesting facts were discovered by Dunnhumby from the Clubcard trials that were extended to 14 stores in 1994. For example, previously it had not been known that a small proportion of customers produced a very large part of Tesco's profit. Information was obtained on how far customers were willing to travel to shop, as well as which departments within stores failed to attract particular customers who shopped heavily in other areas. As several of our interviewees explained, when Dunnhumby presented their results to the Tesco board in 1994, Ian MacLaurin (now CEO and Chairman of the Board) famously remarked: ‘What scares me about this is that you know more about my customers after three months than I know after 30 years.’ (Humby, Hunt, & Phillips, Reference Humby, Hunt and Phillips2008) With its culture of innovation and bold decision-making, the Tesco board decided at the end of 1994 to launch the Clubcard nationally only 12 weeks later. (Humby, Hunt, & Phillips, Reference Humby, Hunt and Phillips2008)

With the introduction of customer data, the interplay between a retailer such as Tesco and its suppliers started to become more complicated. Instead of product supply being just a negotiation between Tesco and one supplier, the setting could involve several suppliers as well as the data-analysis company Dunnhumby.

It was very much a sort of unstable equilibrium, a bit like balancing a ball on the top of a hill, in which all three parties were kind of like, ‘Yes, this is what we want, you could keep it there.’ As soon as anybody said, or Dunnhumby said, ‘I want to make a bit more money,’ or Pepsi said, ‘Oh you know, rather than just growing the category I'd quite like to batter Coke,’ then very quickly this unstable equilibrium would revert to a much more adversarial situation. (C)

Over time, as computing power developed, Tesco was able to analyze more and more transactional data, and so they could mail coupons and offers that were tailored to different customer groups such as vegetarians, diabetics, large families, and eventually, in effect, to individual customer households based on their individual historic and predicted purchasing patterns.

Shifting focus from products to customers

Dunnhumby, the data analysis company working for Tesco, managed the costs far better than Tesco's competitors by focusing its analysis on small samples of the data and using them to draw conclusions with implications for all customers and operations. According to the interviews, Tesco and Dunnhumby developed a simple but effective method of collecting data, analyzing it, and acting upon it, in a short period of time. The approach was highly pragmatic, with a focus on questions that could realistically be answered at the time with the technological resources available. At the time Clubcard was launched, it was fashionable to store huge amounts of operational data in databases with the intent of eventually analyzing it thoroughly. However, the cost of storing and analyzing such quantities of data was very high, and in retailing, data can become out of date very quickly. Instead, Dunnhumby made the pragmatic decision of taking in only part of the available data and focusing only on the most interesting analyses.

After the introductory phase, the collaboration between Tesco and Dunnhumby took two primary forms. First, Dunnhumby analysts were embedded within Tesco that provided ‘routine analyses’ and customer data insight to decision-making. With Dunnhumby running the Clubcard and collecting data from its use, Tesco embedded a Dunnhumby data analyst into every team that we studied (promotions, ranging, and NPD). With the customer data being constantly collected, there was for example an analyst in the department of new product development constantly analyzing the customer-specific sales of each product. ‘We embedded people into the team, so just like any business unit today’ (C)

Second, Dunnhumby has a free-thinking team that applied customer data to develop processes within Tesco. ‘We had an R&D team that were basically looking at the things that were interesting and reported monthly to the senior management team… ….The idea was to see whether looking at customer data provided solutions to some challenges that Tesco was facing.’ (A)

Recall Figure 1 representing Tesco's product range review process; Figure 2 represents this process after Tesco had begun to collaborate with Dunnhumby. In this figure, Tesco's process based on product sales data has remained essentially unchanged, but now Tesco's (strategic) decision-making is no longer influenced only by its own range review process. Instead, Dunnhumby's customer data analysis capability is operating alongside Tesco's process. In fact, due to the quality of the data and analyses provided by Dunnhumby, they constituted the most significant impact on Tesco's range review analysis and even strategic decision-making.

In several instances, the monthly research analyses delivered by Dunnhumby led to Tesco making profound changes in its product range and identifying customer groups that had not earlier been acknowledged. One example of this was the introduction of the ‘Tesco Finest’ product range (other introduced applications listed in Table 2).

‘We identified a group of customers that weren't buying that much with this, we had a lot of holes in baskets … we knew they were a market, from everything they bought from us, but when we looked at what they were not buying, we couldn't imagine they were buying it at Asda or Morrison's or Sainsbury's, so we did a bit of research, and we confirmed the fact that they were primarily buying ready meals at Waitrose and Marks & Spencer's. And that really led to the development of Tesco Finest range. [The introduction of the range] provided general awareness on the existence of a customer group that had earlier not been considered.’ (A)

While the quarterly mailings of coupons to Tesco's customers could eventually be, in essence, tailored to individual customers, other uses of customer data took place at a broader level. An important way in which Tesco used this data was the process of segmenting its customers. The idea was to classify customers into different groups, say, environmentally conscious buyers, those looking for the best nutritional quality at the lowest price, bulk shoppers, etc., by analyzing key product sales. At first, 80 high-volume products that each had a particular attribute were selected, and the number of items customers bought of each of these products produced data points in an 80-dimensional space. As a result, a total of 27 different clusters were identified in this space, and interpreted as customer segments.

In 1998, this segmentation proved highly useful for Tesco in the price wars against competitors, especially Asda, which has had a consistent reputation of being cheaper than Tesco. A traditional method for such price wars is to simply compare prices with the competitor and then to lower prices on the biggest-selling items. However, this costs a lot of money, some of which is effectively wasted, especially as few customers choose where to shop exclusively based on price. Instead, based on the customer segmentation, Tesco was able to identify price-conscious shoppers and the particular products bought almost exclusively by them. According to the management of Dunnhumby at the time: ‘6% of products typically account for 40% of the sales to price sensitive customers.’ By focusing price cuts on these few products, Tesco was able to make a large impact at a comparatively low net cost.

The customer segmentation was also successful more generally; when coupons mailed to customers were targeted according to the segment they belonged to, redemption rates doubled. However, this early segmentation had its weaknesses, for example, some of the 27 segments were simply too small to address effectively. Entirely new segments were defined by placing every product on a certain point in a total of 20 different scales, such as ‘low fat’ against ‘high fat’, ‘ready to eat’ against ‘needs preparation’, etc. When customers were classified according to the quantities they purchased on these scales, 14 segments were identified. The results were again highly interesting: for example, it was found that one group of loyal customers regularly shopped at 12 of 16 Tesco store departments, implying that encouraging these customers to shop even sporadically in the other four departments would produce large profits.

A process that is also related to customer segmentation is the so-called Customer Plan Process. This is an annual process where customer data is used to identify what is important to customers, what their opinions are of Tesco, etc. As a result, a small number of Customer Plan Projects are conceived each year and put into effect. As one interviewee explained, ‘The nature of these is that it's done at a high level because in order to change, let's say, to make Tesco better for quality customers, who are called Finer Food Customers within our segmentation, then that's going to have implications on what products you sell but also how you merchandise them, how you source and distribute them, how you think about them not just in isolation but also in combination.’

Crucial in the whole transformation concerning the use of customer data was a switch in the mindset – the focus at Tesco was shifted from analyzing sales of products to analyzing (and understanding) customers (Paavola & Cuthbertson, Reference Paavola and Cuthbertson2021). As the knowledge of how and what to sell is the backbone of retailing, this change in thinking necessarily revolutionized almost all operational processes within Tesco. Furthermore, the transformation in operations was not limited to Tesco itself, as the next important step in the utilization of customer data was providing it to the supply chain partners. In the UK, and perhaps globally, this was pioneered by Tesco in 2002.

As stated in the interviews, ‘The suppliers are always going to be the greatest experts on their particular product area. Unilever and P&G will always know more about detergent than Tesco.’ (C) On the one hand, a retailer might wish to use this specialized knowledge. On the other hand, customer data collected by a retailer is useful for its suppliers, who are indeed willing to pay for it. However, in both cases, finding a ‘common language’ is crucial. The goal is that suppliers and retailers are both ‘… talking about the same segmentation, talking about the same customers. They're both seeing the same metrics in terms of sales performance…’ (C) For example, a particular promotion can increase the sales of Coca Cola, but decrease the sales of Pepsi by almost an equal quantity. This results in no overall sales benefit to the retailer – though the supplier is likely to be paying the retailer for the privilege of targeting specific customer groups.

‘It's actually quite easy to design promotions that increase the sales of a particular product. The reality is that you sell more Coke, but as a result you sell less Pepsi because Coke is on a great offer. The retailer actually doesn't really benefit from that. It might benefit a little bit because the customer feels they've got a bit of a deal, so it might impact a bit on their overall price perception, but the reality is that certainly if the customer just substitutes, then the retailer sells the same amount of stuff. What they're increasingly pushing suppliers to do is to design promotions and to fund promotions that actually increase the total category purse rather than just product sales.’ (A)

‘That's a really good example of, if you like, the difference between retailers that haven't gone through these stages. I work with other retailers where they haven't yet got to this stage. In effect, if I look at the promotions that they're doing, because the suppliers are usually quite savvy about this, they're running promotions which do increase their sales. They're really doing it all through substitution, which is not really much benefit to the retailer.’ (B)

Decline of the transformational impact of customer data capabilities

On top of the successful innovations and competitive advantages that Tesco achieved in collaboration with the data analysis company Dunnhumby, selling aggregate data to supply chain partners provided an opportunity to obtain revenue from the customer data directly. Partly due to these reasons, in 2001 Tesco purchased 53% of Dunnhumby, and in 2006 Tesco increased its share to 84%. Finally, in 2010, Tesco acquired Dunnhumby entirely. However, providing customer segment data to the supply chain partners required increasing the number of personnel in Dunnhumby significantly, hence increasing costs. Moreover, since aggregate data was now being routinely sold to interested parties, the collection, analysis, and selling of the data became more of a mechanical operation, representing a shift from exploring to exploiting.

‘We're exploring on ranging and we've hit something so now we'll exploit ranging … While some resources are being pushed to exploitation, there's still quite a lot of momentum … then maybe it all slows down a bit when suddenly if you're not replacing exploration that's turned to exploitation.’ (C)

The fact that the customer data was now being merely exploited rather than being developed further could be seen in Tesco's drive for geographical expansion and the opening of new stores.

‘…the company was so used to being able to incrementally improve things or put them into a new geography and very reasonably accurately predict what was going to happen that it didn't seem to have the appetite for true innovation.’ (C)

After the acquisition, the founders of Dunnhumby left the business. Soon afterwards in 2011, the management team of Tesco also went through significant changes as the CEO, Terry Leahy, resigned. Subsequently, Dunnhumby's influence on Tesco has not been as significant as with the previous management teams, who had worked together for 14 years.

According to one of the interviews as well as our observations, prior to the acquisition of Dunnhumby by Tesco the managements of Tesco and Dunnhumby were very close and regularly organized joint activities, including social events, where new innovations may be first envisioned, but after the changes in the senior management on both sides such a connection was lost. Thus, Dunnhumby appears to have had less of a strategic impact on Tesco, and has focused more on the transactional. This was true of the product range review process, as just one example.

‘Customer data was used in ranging decisions in a sort of exploitative way. It remained a critical metric in these decisions. But it didn't generate new ways to do things, as it had in so many instances earlier… like radically transforming the understanding on the ranging decisions.’ (C)

The data collection and analyzing performed by Dunnhumby remained, in fact, essentially unchanged, but instead of experimenting with new ideas, the work now mostly involved running simulations concerning incremental changes in Tesco's stores.

‘We always provided a supporting service … What we would do is if someone played around with the layout, we put the premises into our algorithm, and we'd predict what the outcome would be. So we'd say, that would be 10,000 pounds a week less on current formats. They didn't always take our advice and we weren't always right.’ (A)

Table 1 illustrates these changes over time, comparing and contrasting the range review processes documented in Figures 1, 2, and 3.

Findings

Confirming dynamic capabilities as drivers of transformation

We have seen how the retailer Tesco and the way in which it has utilized customer data has evolved during the past two decades. Despite the previously identified ability of dynamic capabilities to drive change, they have also been traditionally viewed as seemingly stable capacities embedded in routines (Winter, Reference Winter2003). Indeed, in our study many of the relevant routines, such as environmental assessment and the collection of product sales data, have remained fairly stable but undergone ad hoc small adaptations through learning and enactment (Figure 4) – a topic discussed more broadly in the literature of routines (e.g. Felin et al., Reference Felin, Foss, Heimeriks and Madsen2012). As one interviewee explained, ‘I think the focus on competitors hasn't really changed. I think grocery people were obsessing about market share data 10 years ago, they were obsessing about what their competitors were doing 10 years ago, so I wouldn't say that's changed massively.’ (C)

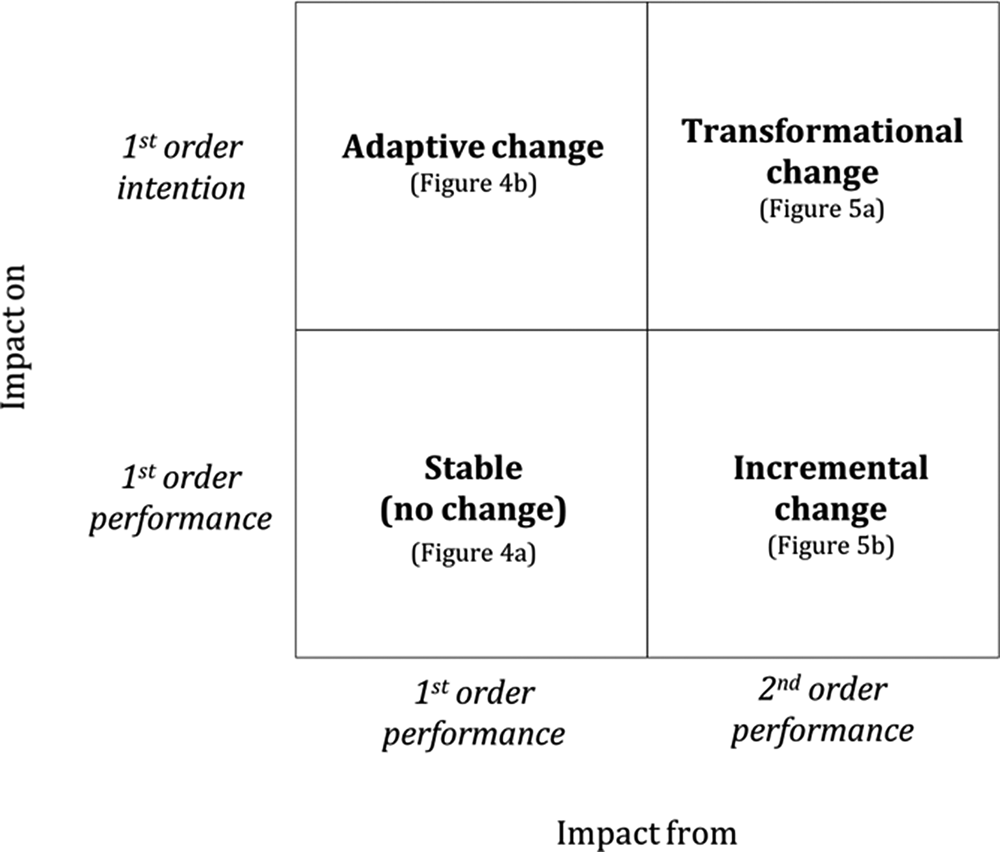

Figure 4. Stable capability (a) versus adaptive capability through performance (b).

Other developments have resulted in changes in organizational routines and processes. As discussed earlier, the development of technology, especially increases in computing power, have had a significant impact on the field. It may be noted, however, that the introduction of Tesco's Clubcard in 1994 was not really based on the invention of any new technology, but rather on innovative thinking on the part of Tesco's board, as well as on the part of Dunnhumby who needed to find ways to effectively analyze data with the limited computing power that was then available. By contrast, an increase in the available computing power has since facilitated data analysis by competitors. According to one interviewee, ‘I think the technology clearly has changed. … There's a desire to stay more to the forefront in those spaces and people realizing that you will either gain or lose market share based on your ability to deploy the best technology to your business.’ (C)

Prior to the introduction of the Clubcard in 1994, none of the grocery retailers in the UK were directly gathering significant customer data, though some customer data was captured via third party panels, such as those provided by AC Nielsen (a global marketing research firm). While access to customer data sources were limited, all grocery retailers gathered significant and comprehensive product sales data. However, the product sales data did not provide any information relating to individual customers. Our research clearly demonstrates this lack of knowledge. For example, Tesco did not know that a small proportion of customers were responsible for a large proportion of the profits. While observing one's competitors has seen little change and the role of technological development has been mostly a facilitating one, ideas and practices in collecting customer data have changed radically, particularly with the introduction of online retailing where the collection of customer data is a necessary part of the process. As one of our interviewees explained, ‘I guess I've already talked about the level of emphasis on particularly data and analytical talent, and I think that's probably the one that's actually changed the most.’ (C)

To illustrate and explore the development of capabilities through the use of customer data, we have focused on Tesco's product range review process, which prior to Tesco's collaboration with Dunnhumby was organized as presented in Figure 1. Before Tesco's collaboration with Dunnhumby, this process focused on the goal of meeting demand separately for each individual product. As we recall from the case description, this could not greatly take into account the interactions between sales of competing products, say Coca-Cola and Pepsi– though suppliers would obviously consider such data at a market level.

Tesco's product range review process after it began collaboration with Dunnhumby was organized as presented in Figure 2. In the new process, the focus was no longer on products individually, but rather on overall sales as observed by means of customer data. Returning to the previous example, in the event of a change in the sales of Coca-Cola, it was now possible to observe whether new Coca-Cola customers previously purchased Pepsi and vice versa, in order to draw more insightful conclusions. This new focus represented a fundamental shift in the overall understanding of the range review process, as it was possible to identify truly unique products from those that were substitutable. Dunnhumby's ability to change the process can be seen as a dynamic capability that shifted the focus of the decisions from products to customers. The analyses had a profound influence on changing Tesco's understanding and decision-making in range management.

The variety of applications of the concept of dynamic capabilities came about in an attempt to explain competitive advantage (Helfat & Winter, Reference Helfat and Winter2011). It can be said that during the time when other UK grocery retailers were not yet actively analyzing customer data, Tesco viewed the world quite differently from its competitors. While the competitors did collect contact data, demographical data, and sales data, the focus of this data analysis was on product sales rather than the type of customer segmentation analysis that Tesco performed and successfully applied. This resembles the way in which capabilities are seen as dynamic based on the specific goals they are designed to accomplish, see Helfat and Karim (Reference Helfat and Karim2014). As stated in the interviews, ‘… a lot of the changes have come as new segmentations have been developed … [providing] new levels of understanding.’ (B) This supports the description of capabilities as a key part of the knowledge creation and building of core competencies within an organization.

Even with the example set by Tesco, competitors have taken very different paths in their approach to customer insight. As noted by Eisenhardt and Martin (Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000), organizations seek to repeat those adapted routines with successful outcomes. In some cases, this seems to have promoted the use of customer data, whereas in other cases it seems to have discouraged it. Environmental assessment led Tesco's competitors to introduce their own loyalty card programs, but such assessment was sometimes too superficial, in that it recognized the externally focused consumer marketing aspects but did not reveal the crucial internally focused advantages offered by such a program, namely customer data driving change in the routines and structure within the retail organization.

More recently, almost all of the remaining competitors have moved toward the collection and active use of customer data, whether directly through loyalty programs and online sales, or indirectly via association with a particular payment card. ‘Technically, just the raw computing power and the dramatically lowering of cost around that has been a big influence because it definitely makes the cost implication of storing the data much, much, much, much lower. It's also allowed the data to be genuinely utilized for business decisions.’ (C) Altogether, the collection of customer data as well as its utilization in decision-making can be seen as a capability that was first introduced in the mid-1990s and has now become ubiquitous in the mainstream field. In accordance with the view that dynamic capabilities are a source of organizational change and adaptation, customer data has been a decisive factor that has resulted in the transformation of Tesco and eventually the entire field of UK grocery retailing during the past two decades.

Questioning dynamic capabilities as drivers of transformation

We observe that Tesco's range review process, or at least Tesco management's understanding of the process and its goals, has remained largely stable throughout Dunnhumby's collaboration with Tesco. In essence, this fits the description by Nelson and Winter (Reference Nelson and Winter1982) and later Winter (Reference Winter2003) of organizational capabilities as embedded within its routines.

Prior to its acquisition by Tesco, the independent management of Dunnhumby collaborated with and significantly influenced the strategic management of Tesco, and vice versa. This provided everyone with a common mindset on the collection and analysis of customer data and the significant new innovations that were produced, resulting in high levels of motivation and smooth decision-making, as is typical of routinized processes Okhuysen and Bechky (Reference Okhuysen and Bechky2009).

However, in 2010 Tesco acquired Dunnhumby, and the CEO of Dunnhumby stepped down, with Tesco's senior management changing shortly afterwards. The new senior management of Dunnhumby did not have a similar influence on Tesco at the strategic level, while at the operational level Dunnhumby essentially started to function under the management of Tesco. Tesco's range-review process after the acquisition was organized as presented in Figure 3. While Dunnhumby's data analysis routine remained essentially unchanged, the previous deep impact on Tesco's range review process analysis and strategy has been replaced by a more superficial input to Tesco's decision-making. Instead of fundamentally changing the way in which ranging was done, the customer data was now exploited to make regular incremental changes to the product range.

Following Adler, Goldoftas, and Levine (Reference Adler, Goldoftas and Levine1999), we recall that dynamic capabilities (or metaroutines) are understood to be routines that are designed to transform existing operational routines or to create new ones. In our study of dynamic capabilities, we have seen that a clearly defined Dunnhumby's data analysis capability emerged over time, but the specific executions of it (i.e. the performance) and its impact changed over time. Early on, in several instances, this dynamic capability had a profound impact on Tesco's decision-making routine, but later it began to merely influence Tesco's everyday operations in an operational way, which can be seen as an influence on and support to the performance of Tesco's routines. In the model given in Figure 5, this represented a shift from a higher-order capability that is driven strategically to one that is focused on current operations.

Figure 5. A higher-order capability that is (a) strategic or (b) operational and consequently (a) transformational or (b) non-transformational. (a) 2nd order performance impacts 1st order intention (second-order capability transforms first-order capability). (b) 2nd order performance impacts 1st order intention through 1st order performance (second-order capability adjusts first-order capability).

While the transformational nature of a dynamic capability is understood to be determined a priori, we argue that it is not possible to determine beforehand whether or not a higher-order routine will succeed in producing transformation. In the role of a coordination mechanism that helps adjust the execution of the everyday operations of an organization, higher-order routines may produce incremental (rather than transformational) change. One of our interviewees explained: ‘Certainly all the same processes and analyses were still run… and there was new data around… I think they've massively improved the data collection side of it, but who is interpreting it?…that part of the process was lost’ (C). As noted by Becker and Zirpoli (Reference Becker and Zirpoli2008) as well as by Eisenhardt and Martin (Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000), the management of an organization seeks to repeat those adapted routines with successful outcomes, but in the case of the Tesco-Dunnhumby interaction, such as exemplified in the range review process, the end result has apparently been a decrease in the impact of innovation.

Discussion

The main contribution of our paper is to better understand how capabilities may have varying roles in higher-order transformation. This overall contribution is founded upon three smaller contributions. First, we argue that introducing a more theoretically consistent and practical taxonomy for (dynamic) capabilities may help in resolving some of the criticisms of their practical implications in reality. We discuss how transformation requires a disruption of existing operational capabilities, which may result from one of the three identified mechanisms, adaption, incremental change or transformation. Second, we underline the importance of studying capabilities in their networks within organizations (Birnholtz, Cohen, & Hoch, Reference Birnholtz, Cohen and Hoch2007; Salvato, Reference Salvato2009). Taking a relational perspective (Emirbayer, Reference Emirbayer1997) enables us to show how capabilities can interact and are consequential for organizational outcomes. This allows us to overcome the oft-voiced criticism of studies that use an aggregate perspective to examine capabilities and their microfoundations (Winter, Reference Winter2012). Third, and building on the previous contribution, our study addresses the lack of constructive exchange between the parallel streams of capability and routine research (Parmigiani & Howard-Grenville, Reference Parmigiani and Howard-Grenville2011). By focusing on the relationality of capabilities in higher-order change, we look to link micro-foundations of capabilities with questions of organizational performance, and vice-versa, in a novel way. Finally, we discuss our results in the light of future research.

Redefining capabilities as drivers of adaptation, incremental change, and transformation

A starting point in our research was the notion that capabilities can be divided into two categories, first- and second-order capabilities, and that the latter are defined, following the literature, as dynamic capabilities or metaroutines that are designed to transform existing operational routines or to create new ones. However, based on our findings, we propose that it is fruitful to differentiate between capabilities that are truly transformational and those that coordinate or adapt operations (e.g. through input data), providing incremental change, rather than transformation. In our definition, the term transformational change only refers to the case where a capability leads to a process of change that orients an organizational process in a new direction and brings about profound changes in the overall understanding of operational (first-order) capabilities. In our case, the degree to which a capability is transformational strongly depends on whether it is viewed, particularly by senior management, as more strategic or operational (cf. Felin et al., Reference Felin, Foss, Heimeriks and Madsen2012).

Building on this notion, we propose a new more theoretically consistent and practical taxonomy for capabilities. Operational (first-order) capabilities can be seen as stable (see Figure 4a) or internally adaptive (see Figure 4b), while higher-order capabilities provide a link to other drivers that provide either incremental changes or transformation (see Figure 5). To clarify the concept of capabilities, we propose a clear division for the use of this terminology that is depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Proposed taxonomy for capabilities.

Interdependence of capabilities within organizations

Second, our focus on the interaction of capabilities within organizations has implications for our understanding of capability interdependence and its role in creating connections. Interdependence is a long-standing object of inquiry in organization and management studies that goes back to Thompson (Reference Thompson1967) classical distinction between three types of task interdependence: sequential, pooled, and reciprocal. While scholars interested in practices have pointed out that the interdependence of routines is important to achieving the set tasks of an organization (e.g. Parmigiani & Howard-Grenville, Reference Parmigiani and Howard-Grenville2011), capabilities have often been seen to provide predefined outcomes (Winter, Reference Winter2003). Recent work under the umbrella of routine dynamics has slowly started shifting the focus toward understanding interdependencies in more detail at different scales; from the interdependence of action patterns within single routines to viewing the interaction of routines as an ecology (Feldman, Pentland, D'Adderio, & Lazaric, Reference Feldman, Pentland, D'Adderio and Lazaric2016). Our study also underlines the relational nature of capabilities.

Taking such a relational perspective is useful because it does not focus on the aggregation of capabilities in the sense of a mere accumulation of stable entities. Instead, it acknowledges that as capabilities operate, they interact, creating varying generative forces (Emirbayer, Reference Emirbayer1997). Our empirical findings support this conceptual shift, which is less concerned with bringing together the ‘right’ capabilities to fulfil a task and more to do with how these capabilities and their outcomes feed into each other, potentially leading to changes within an organization. Capabilities may also be consequential for organizational outcomes that go far beyond their individual purpose.

Bridging the capabilities and routines perspectives

Third, and building on the previous contribution, our study offers the opportunity to create connections between the so-called capabilities perspective and the routines ‘as practices’ perspective (Davies, Frederiksen, Cacciatori, & Hartmann, Reference Davies, Frederiksen, Cacciatori and Hartmann2018). As acknowledged by Parmigiani and Howard-Grenville (Reference Parmigiani and Howard-Grenville2011), the two streams of literature have relatively distinct epistemological underpinnings but each has its shortcomings, such that each could profit from the other. Our study illustrates the relational nature of capabilities and hence explores how the changing context may bring about varying higher-order impacts. Such co-constitution among capabilities and organizations has not been sufficiently studied.

Future research

Future research may utilize this understanding of the interactions between capabilities to shed light on other questions important for strategic management, such as: What are the roles of templates and formal descriptions of capabilities in shaping their impact in practice? How are different temporal enactments of a capability best coordinated or managed? Is there a ‘natural’ evolution for dynamic capabilities, for example, to move from being drivers of organizational transformation, to field transformation, to incremental change, and eventually ceasing to be relevant?

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.