In late 1927, New York hosted the latest of a long series of public exhibitions exposing US audiences to the “thrills of the orient.”

The interior Madison Square Garden yesterday assumed the color and form of Bagdad on a fete day, as merchants and craftsmen of the East prepared for the opening of the Oriental Exposition.Footnote 1

Though more mercantile in nature than the famous exhibitions at the Chicago and St. Louis World Fairs, the language around these was similar.Footnote 2 Booths of Turkish rugs, Indian crystal, and Chinese silk were advertised, but the chance to gawk at the culture—and the women—of these far-off lands, seemed to be the more central lure. Alongside images of sheiks and jewel-encrusted rifles, ads for the exposition featured “Desert Queens serving coffee” in “The Sheik's Café,” while newspapers promoted the chance to see “100 girls from almost every country in the world . . . in an Oriental beauty contest in their native costumes.”Footnote 3 Accompaniment was provided by a “16-piece Oriental Orchestra,” conducted by one Alexander Maloof, a Syrian-American who emigrated to New York in 1894 at age ten and was in 1927 entering the third decade of his multifaceted career as a pianist, composer, conductor, arranger, publisher, and music teacher.Footnote 4

Performing Arabic music for Euro American audiences had been a consistent element of Maloof's career. Over the previous decade and a half, he published and recorded a series of tunes appealing to popular fads in Orientalist imagery and dance styles, including “oriental fox-trot[s]” (“Syria,” “Egyptiana,” “Pharoah,”), “harem dances” (“Najla”), “oriental waltzes” (“Call of the Sphinx”), and tangos (“Tango Egyptienne”).Footnote 5 He even wrote his own “Salome,” though in 1923 well after the initial craze between 1907–1910.Footnote 6 Around 1914, his “Egyptian Glide,” available in “oriental tango” and “turkey-trot” versions, could be heard performed by Maurice Levi's orchestra at the Jardin de Danse.Footnote 7 In the 1920s his Maloof label recorded and released music as the Arab ethnic entry into Gennett's race-records business.Footnote 8 Maloof wrote music for silent films and talkies, songs for Broadway, sentimental parlor songs, and dances for Adolf Bolm's Ballet Intime. Footnote 9 He conducted pit ensembles for musical productions, the Bamberger Symphony Orchestra, and his own Maloof Oriental Orchestra, often broadcast over the radio in programs like “Orchestras That Differ” or as incidental music for radio dramas set in the “Orient.”Footnote 10 Maloof also wrote instructional piano books and Arabic-language songbooks and performed Arabic music for the audiences of “Little Syria,” the Arab neighborhood in lower Manhattan.Footnote 11

Scholars of Arab American music may be familiar with Alexander Maloof through Anne K. Rasmussen's thoughtful discussion of his work and its relationship to larger trends in Arab American music in her 1991 doctoral dissertation, and her subsequent work has become foundational to the field.Footnote 12 As Rasmussen has documented, trends in Arab American music during the twentieth century did not follow up on Maloof's brand of Arab Western musical mixture, and his music disappeared from popular consciousness.Footnote 13 Nevertheless, Maloof contributed to the integration of the Syrian population into the musical life of New York, to the popularization of Arabic and “Oriental” musical sounds in US concert halls and films, and foreshadowed some of the Lebanese popular music to come later in the twentieth century.

Scholarship on early twentieth-century popular music in the United States has documented the ways that racial and ethnic caricature—most significantly based in anti-Blackness—as well as representation and self-presentation, were fundamental to the development and popularity of musical style and to the construction of popular notions of racial and ethnic difference.Footnote 14 The appetite for “Oriental”-themed entertainment was enormous in the early twentieth-century United States, and excellent scholarship on Orientalist tropes in music and theater has illuminated their ubiquity within US popular culture.Footnote 15

I am interested in a different story about the significance of his music, one which decenters European American audiences for the “Music of the Orient” in order to consider how Maloof's “conspicuous musical hybridization” (to quote Rasmussen) performed a different set of functions within the context of the Syrian mahjar (diaspora).Footnote 16 Focusing on the 1910s, this article uses Maloof's example to demonstrate how the music of the New York mahjar reflected and informed the contested political conversations taking place in Arabic around the world, from the homelands around Beirut and Damascus, to the initial Syrian settlements in Cairo and Paris, to other American colonies in Sao Paulo and Buenos Aires. Specifically, I argue that music and written discourse about music in the Arabic press were centrally concerned with the existential question looming over the Syrian mahjar: the political fate of greater Syria.

An examination of the role of Arab American music within the mahjar not only adds a further dimension to the growing literature on the Arab diaspora in the early twentieth century, but it also forces us to reconsider standard narratives of US Orientalist music in the period. To this end, I conclude this article with a discussion of “Armenian Maid,” an “oriental song and Fox-trot” from 1919.Footnote 17 On first consideration, the song appears to be a standard entry into the huge register of “oriental” tunes written by and for European Americans, if perhaps with an additional news peg to drive sales. The discovery that its composer “M. Alexander” was in fact Alexander Maloof writing under a pseudonym requires consideration of the politics of composing for a largely European American audience while embedded in the discourses of the Syrian mahjar. Within this context, the song was a political tool, designed to exploit the Orientalist tropes of US popular music in order to move public opinion towards US interventions on behalf of the Christian minorities within the Ottoman empire.

Biography and Little Syria

Iskandar Rājī al-Mʿalūf was born January 23, 1884 in the town of Zahle in modern-day Lebanon, on the western slopes of the Beqa ʿValley.Footnote 18 Iskandar (Alexander) came from an educated and relatively well-off branch of one of the largest groups of families in Mount Lebanon (variously Malouf/Maluf/al-Mʿalūf).Footnote 19 His father, Ibrahim (Abraham) Hanna, “reared in abundance and wealth” in Zahle, studied Arabic, French, and English at the Jesuit College of Ghazeer, Mount Lebanon, and served as translator for visiting dignitaries to Syria.Footnote 20 According to an article in al-Majla at-Tijāriyya as-Sūriyya al-Amīrkiyya (the Syrian American Commercial Magazine), Abraham worked with a trader who imported goods from Europe and purchased a piano from him when Alexander was three years old. Alexander took to the instrument immediately, but his time in the family home in Zahle was short; he was still a child in 1890 when the family joined the growing exodus of Syrians to Beirut.Footnote 21

In the late 1800s Beirut—alongside Cairo, Baghdad and the other Arab capitals—was experiencing a cultural renaissance known as the nahḍa, an explosion in literature, science, and the arts.Footnote 22 In an introduction to his history of the Maloof family, writer and scholar ʿIssa Iskandar Mʿalūf describes the period:

The foundation of schools was strengthened, and the wares of knowledge overflowed in their marketplace. Our scholars published inspiring thoughts dispersed by printing presses on inked papers, straightened by the fingertips of printers into gilded leather bindings. Bookstores overflowed, and the range of thought expanded. It seemed as if authors drew their ink from the blackness of their eyes and the fathoms of their hearts, as they wove their manuscripts. . . . They fueled the lamp of their work with the oil of their foresight, and exhausted the wells of their souls on research.Footnote 23

While the nahḍa witnessed a resurgence in cultural production across the Arab world, the economic and political situation in Ottoman Syria and in the Mount Lebanon area in particular was not as bright. Along with the opening of international markets for textiles and shifts towards proletarian labor forms, the Lebanese silk industry collapsed in the 1870s.Footnote 24 One third of the population of Mount Lebanon (as much as one-sixth of the population of Greater Syria) emigrated by the turn of the century.Footnote 25

Leaving for economic opportunities, muhājirīn (migrants) from Greater Syria joined existing communities in Cairo, Alexandria, and Paris, or went farther afield, founding communities in Argentina, Brazil, Central America, Canada, and the United States; the first Syrian muhājirīn probably arrived in New York in 1871.Footnote 26 Early Syrian immigrants to the Americas were primarily peddlers and sellers of clothing and dry goods, including silk “kimonos” and trinkets from the “Holy Land,” and they founded a thriving community on Washington Street in lower Manhattan.Footnote 27

Travelling from Beirut by way of Boulogne, Alexander along with his mother Hanna and five siblings arrived in New York in 1894 at the peak of Syrian migration to the United States.Footnote 28 Unlike the majority of the first wave of Arab immigration, the Maloofs were not peasant farmers or small-time merchants, but members of the educated middle class, though a class where matriarch Hanna still earned an income in “fancy needlework.” Both Abraham and Alexander were referred to in Arabic-language documents as ‘effendi’, an Ottoman Turkish word originally designating members of the clerical corps of the Ottoman bureaucracy but which had come to refer to men constituting the cultural bourgeoisie.Footnote 29

Alexander enrolled in New York public school upon arrival and was composing under school music director Alfred Hallam by age thirteen. As a teenager, he worked as an errand boy while his sisters worked in embroidery and dressmaking. He also studied piano, theory, orchestration, and composition with Joseph Henius, who went on to teach at the Institute of Musical Art (which became Juilliard).Footnote 30 Maloof's first registered copyright is from 1902, for a set of waltzes entitled “Twilight Echoes.”Footnote 31 At the age of twenty, Maloof was Henius's assistant and taught piano in his music school.Footnote 32 By 1908, twenty-four-year-old Maloof was fully embedded in the musical life of New York and Little Syria. The only professional musician listed in the Syrian businesses directory from that year, he charged between ten and twenty dollars for performances at parties and weddings and one dollar per piano lesson, which he gave at the Goetz & Co. Piano Parlor. He also taught both Arabic and “American” composition.Footnote 33

The New York community in which young Maloof found himself remained connected to Mount Lebanon, the Arab world, and the rest of the mahjar through a lively Arabic-language press. The earliest Arabic newspaper, Kawkab Amrika (American Planet), was founded in 1892, followed by titles such as al-Huda (The Guidance), Mir'āt Al-Gharb (Mirror of the West), and al-Ayām (the Days). As Stacy Fahrenthold describes, “mahjari editors established a functional press syndicate by 1908” and “in New York alone, nearly a dozen Arabic language periodicals operated simultaneously by 1914.”Footnote 34 Beyond publishing news and debates about local issues, listing church services, public events, and arrivals of ships and immigrants from Syria, these newspapers also provided near-daily dispatches from Zahle, Beirut, Tyre, Cairo, Paris, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, and Montreal.

These pages document a thriving Syrian community of restaurants, cafes, dress shops, and churches, and teem with references to the sounds of the American mahjar. Articles in an edition of Mir ͗āt Al-Gharb might describe the piano playing at a Syrian wedding reception, the songs at a Greek Orthodox Sunday school pageant, or a meeting of Syrian musicians in Montreal. The musician most often named in these early Arabic-language newspapers is Ustādh al-Fāḍl Iskandar Effendī al-Maloof (Esteemed Professor Alexander Effendi Maloof). Newspapers advertised the sale of pianos, player pianos and rolls, and Middle Eastern instruments like the ʿūd and qānūn, and every issue featured ads for music sold in shops with names like al-Macksoud, Khoury and Coury, Daher and Rizcallah, and Sabongi.Footnote 35 As Ali Jihad Racy has written, commercial recording in the Arabophone world began in the first decade of the twentieth century, and by 1904 shops in Cairo were advertising Columbia phonographs.Footnote 36 At the same time, shops in New York's Syrian Quarter were importing records from Cairo and Beirut.

Arabic newspapers and magazines imported from abroad reported on music from Cairo and Beirut as well. When ʿIssa Mʿalūf began his own journal from Zahle in 1912, al-Āthār, he published an article on music in the first volume. Describing humanity's historical drive to make music, he states:

[It is] as if that longing which endures in the hearts of the sons of Adam for the fertile garden of Eden has caused them to open themselves and give air to [music], and to relieve that which in their souls was blocking remembrance of the past. . . . Thus their bright wisdom guided them to invent music, as necessity is the mother of invention . . . and we will return at every opportunity to discuss [it] for the delight of the generous readers of al-Āthār.Footnote 37

The metaphor of music as the means of remembering the garden of Eden would have resonated for New York's muhājirīn from Mount Lebanon. As Akram Khater argues, for many Syrians in the Americas, the goal was always to return. The trajectory from peasant farmer in the Beqaʿ, to economic migrant, to merchant in the Americas, to a member of the Lebanese middle-class back home was common; returnees became a major factor in the development of Lebanon in the 1920s.Footnote 38

Planning to return or not, the inhabitants of Little Syria were avid consumers of music from back home, and new recordings arrived off of transoceanic liners every month. As Racy and Moser have argued in regard to the Brazilian mahjar, music was a tool of memory, of maintaining an attachment to the homeland, and preventing the loss of Arabic language and culture among the generation being raised in New York.Footnote 39 However, this does not imply the preservation of a static past; the Arabic press from this period is shot through with traces of live music demonstrating that New York's Syrians viewed themselves as full participants in a pan-Arab nahḍa, propelled by artistic and cultural progress, or taṭwīr.

These two goals, memory and progress, coexisted within the public Arabic discourses around music and theater. For example, one 1911 article titled “Nahḍa al-tamthīl al-ʿarabiyya” (“A Renaissance of Arab Acting”) reviewing two productions by women, one in Cairo and the other by Syrian women in Arabic at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, begins by arguing that artists cannot progress by remaining in one place and later states that these Syrian actresses may create a “renaissance of memory.”Footnote 40

Maloof began publishing songs consistently in 1909, and in 1917 he compiled the first of several books of piano arrangements, Music of the Orient, which embodied both the memory and progress strains of mahjar discourse.Footnote 41 Half of their pages consist of sparsely harmonized transcriptions of folk tunes and the Arabic musical forms mawwāl, muwashaḥāt, bashraf, and dūlāb. In the other half of each book, Maloof published original songs and instrumental pieces, sometimes on explicitly contemporary themes as in tunes like “Hakeeni al Telephone” (Talk to me on the telephone) or “bJeel al-Ishreen” where Maloof uses the ambiguity of the title (the twentieth generation or the generation of the ‘20s) to joke about contemporary fashion (“In generation 20, Eve has returned to wearing a fig leaf”).Footnote 42 Others include love songs, patriotic marches, and arrangements of popular hits like “O Sole Mio” or “La Donna e Mobile” from Rigoletto with lyrics translated into Arabic.Footnote 43 Maloof's connection to the larger mahjar is also made clear in these compilations. For example, he sets to music poems and translations by Emil Zaidan, a fellow muhājir in Cairo (and editor of al-Hilāl following the death of his famous father Jurji Zaidan,) as well as texts by Nasseeb Arida, the founder of literary journal al-Funūn.Footnote 44

The design of the Maloof Records label illustrates the divergent meanings that one set of symbols held for (mostly European American) Anglophone audiences and for the Arabic-speaking audiences of the mahjar (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Maloof Phonograph Company, Soorya alWatan.

To most US listeners, the Sphinx would have invoked a general sense of “Oriental” mystery; the fact that the record contained music from the Syrian mahjar, not Egypt, an irrelevant distinction. To Syrian muhājirīn, however, the Sphinx was both a specifically Egyptian symbol and an indication of quality rather than simply place of origin. The best recordings of Arabic music came from Cairo, and Maloof explicitly marketed his records as on par with the newest recordings from Egypt, a strategy central to Maloof's Arabic-language marketing. For example, one advertisement for the Maloof Record Company in al-Majla al-Tijaria as-Suriyye al-Amrikiyye, published near Thanksgiving of 1920, begins thus:

Thanksgiving.

(1) Thank God, that a republic elects the leadership of the United States.

(2) . . . That you live in America the Great, far from the trouble and crisis overseas.

(3) . . . That you don't need, at the end of the day, to seek out Syrian phonographic records from Egypt, and pay enormous prices, because the Maloof Phonograph Company will give you all of the modern Egyptian and Syrian songs for a price of two dollars per disc.Footnote 45

From the earliest years of his career, Maloof also published in European American styles, often romantic piano pieces like “Day Dream Reverie” and “Majestic Waltzes” from 1909.Footnote 46 Significantly, Amrīkī (American) rather than “Western” or “classical” was the term used to describe that music in the Arabic press and in his own advertisements. Maloof's “American” piano music is fairly standard for the time; he was well versed in Stephen Foster, later publishing a book of Foster melodies arranged for children.Footnote 47 He composed in US genres like barn dance music; according to Habib Katibeh, Maloof even composed some music for the Marlene Dietrich/Jimmy Stewart Western Destry Rides Again (1939).Footnote 48 Maloof's “American” compositions extended beyond US-associated idioms to more directly patriotic pieces, as exemplified by “For Thee America,” a piece which became his calling card in the Arabic- and English-language press.

For Thee America

In 1912, the National Flag Day Association called for a new national anthem that would combine elements of the “German, French, and English anthems,” arguing that the United States was a combination of these peoples. President Taft sent the organization a telegram of support, prompting a number of composers to take up the challenge.Footnote 49 Maloof quickly offered up a song titled “For Thee America,” setting a text by Elizabeth Serber Freid. While the piece is idiomatically American, with an AABA’ structure, and harmonic vocabulary and keyboard arrangement that could have come directly from Katherine Lee Bates and Samuel Ward's “America the Beautiful,” Maloof took the opportunity to work a tiny hint of Syria into his US national anthem. The melody of “For Thee America” begins with a figure nearly identical to the initial motion of his “A Trip to Syria” composed that same year.Footnote 50

The initial gesture of “A Trip to Syria,” an upward fourth leap followed by scalar motion up a fifth in maqām nahāwand (in Arabic modal terminology), reappears in “For Thee America” transposed to F major with a lower-neighbor ornament removed (Figures 2 and 3). More broadly, the leap-followed-by-scalar-motion melodic trope is also common in Maloof's arrangements of Arabic tunes for piano, where he typically uses octave doubling within monophonic or heterophonic textures to imitate the sound of the doubled courses of an ʿūd. Similarly, linear melodic motion set against leaps to and from a stable pitch recalls the melodic motion of an ʿūd player interspersing linear melody with leaps across the strings to the asās or ghammāz of the maqām.Footnote 51

Figure 2. Initial melodic gesture from “For thee America.”

Figure 3. Initial melodic gesture from “A Trip to Syria.”

Though never adopted for its original purpose, “For Thee America” was integrated into the patriotic repertoire of the New York public school system and included in several collections; notices from the 1910s and 1920s frequently mention performances at patriotic celebrations, on one occasion with Maloof conducting a choir of five hundred students.Footnote 52

Maloof's success was well-documented in the mahjar press. Not only did the New York Arabic papers cover performances of “For Thee America,” expressing pride in the young “Professor,” Arabic publications in Cairo and Beirut reported on the song, depicting Maloof as an example of the intelligence and diligence of the young Syrian muhājarīn, and their capacity to thrive wherever they lived.Footnote 53 In an Arabic-language excerpt from “Syrians in the United States,” published in al-Muqtaṭaf (Beirut and Cairo), Phillip Hitti wrote:

Among those who have distinguished themselves [among young Syrians in the United States] in the fine arts is a musician who has become known throughout the country, and who has achieved national fame by introducing Arabic melodies to the Western world. Among his tunes is the anthem “For Thee America,” which the school boards in New York and elsewhere have chosen as an official education song for use in public schools.Footnote 54

Patriotic songs and the use of music as a political tool were hardly foreign to Arabic discourse in the mahjar, though in 1912 that discourse was not precisely nationalistic in tenor. Instead it reflected the particular aims of a Syrian mahjar still hopeful about the possibility of reform within an Ottoman context rather than directly focusing on nationalist revolution. As Fahrenhold states, “In 1912, no one in the mahjar envisioned a Syrian future outside the framework of the Ottoman Empire.”Footnote 55 This changed profoundly over the next decade, and Maloof's piano books and recordings from the 1910s and 1920s are filled with patriotic and nationalist songs for both his current home—for example, “Amreeka ya Helwa” (America O Sweet), “For thee America,” and “Uncle Sammy”—and a range of articulations of a national homeland such as “Sooria,” “Mt. Lebanon,” “Soorya'l Watan” (Syria the Nation/Homeland), “Lebanon,” “Sooria al-Jadeedat” (New Syria), “Sooria Bilady” (Syria My Country), “Cedars of Lebanon,” and “Lobnanol Ckalido Lobnani” (My Eternal Lebanon, subtitled “Syrian Patriotic Song”).

The breadth of lyrical content in these songs indicates that Maloof was less interested in advancing one political position than in providing a musical soundtrack for the diverse political visions of the mahjar, including proponents of a unified and independent bilād ash-Shām (Greater Syria), Lebanese nationalists, and pan-Arabists. In a nod to the Egyptian independence movement, he wrote a march dedicated to “Zaglul Pasha” (S ʿad Zaglul), the founder of the Egyptian Wafd party and eventual prime minister of Egypt.Footnote 56

The status of Syrians vis-à-vis the Ottoman Empire was also of local importance to Syrians living within the United States. Prior to 1900, the US census did not distinguish between “Turks” and “Syrians.” People arriving in the United States from modern day Lebanon and Syria were labeled “Turks” on their entrance forms, rankling the Syrian muhājirīn who were growing progressively more anti-Turkish in their politics. Furthermore, the resultant classification as “Asiatic” could preclude naturalization. A series of court cases between 1909 and 1915 settled the legal question of whether Syrians were “white” for immigration purposes in the affirmative.Footnote 57 In a personal demonstration of this tension, it appears that someone initially wrote “Turkey” for place of birth on Maloof's 1908 “declaration of intent” to pursue naturalization, which was subsequently scratched out and replaced with “Syria” (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Correction on Maloof's Naturalization Document. Alexander Maloof. “Declaration of Intention.” Petitions for Naturalization from the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, 1897–1944. Series: M1972; Reference: Roll 0104. Petition No. 10431–Petition No. 10714. Washington DC: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), n.d.

The centrality of Syria's political status within the New York mahjar is further exemplified in an article in New York's Mir ͗āt Al-Gharb, describing a May 1911 concert (ḥafla mūsiqiyya) that featured Maloof and his piano students:

At 8:30pm last Saturday the hall of the Kings County Democratic Club in Brooklyn filled with Syrian and American audiences for the presentation of a musical concert and dance, organized by the esteemed Professor Alexander Effendi Maloof. At 9 o'clock George Effendi Ferris, the well-known Syrian lawyer, appeared on stage, and welcomed those present on behalf of Professor Maloof.Footnote 58

George Ferris was a significant figure within the New York Syrian community, well known for high-profile cases and communications with the US State Department about legal matters on behalf of the community.Footnote 59 He was also Alexander Maloof's brother-in-law and a member of the Syrian “Damascus” Masonic Lodge, where Maloof was a participant and official lodge organist.Footnote 60

With Ferris as MC, Maloof and his students played a variety of tunes; Mir ͗āt Al-Gharb identified these as “Eastern, and some of them American, Italian, and French.” The article also indicates that the subsequent dancing continued until “three hours after midnight,” and the audience was “entranced” (iṭrāb) by the singing of “a new American anthem composed by Maloof.” But the tune that most notably delighted the audience was the Egyptian Khedival anthem.Footnote 61

That this group of young Syrian muhājirīn, reveling long after midnight at a Brooklyn party, became most animated in response to an Egyptian anthem reveals the transnational political focus of the New York mahjar. For Syrians everywhere, Egypt at this point represented a potential political model, as well as the cultural center of the Arabophone world and home to the most educated and elite population of the Syrian mahjar.Footnote 62 Though still nominally subject to Ottoman rule, Egyptians enjoyed a level of political and economic autonomy, especially relative to their Arab counterparts in bilād ash-Shām. As Fahrenthold describes, New York muhājirīn had celebrated the 1908 Young Turk revolution in Istanbul and the reinstatement of the Ottoman constitution as opening the possibility for an autonomous Ottoman state in Syria in line with Egypt's status.Footnote 63 Within the climate of 1911 Little Syria, then, the Egyptian Khedival anthem represented a connection not only to the transnational mahjar, but to the possibility of a politically autonomous homeland.Footnote 64

Between 1912 and 1916, however, the tenor of the New York Arabic press shifted significantly in response to Ottoman repression, most notably the public hanging of over forty Arabists and reformers in Damascus and Beirut in 1915 and 1916.Footnote 65 This shift was also in response to the Ottoman ban on the import of mahjar newspapers into Syria.Footnote 66 Throughout the 1910s the discourse in mahjar newspapers began to espouse a variety of nationalisms and political movements. Mir'āt al-Gharb, published by Najeeb Diab and associated with the Greek Orthodox community of Little Syria, espoused an explicitly anti-Ottoman stance earlier than many of the other newspapers, which influenced its coverage of culture both locally and abroad.

In 1913, Diab was one of the three official representatives of the American mahjar to the First Arab Congress in Paris, and he represented New York alongside Na ʿum Mukarzel, editor of Al-Huda.Footnote 67 The Paris Congress holds a central place in the history of Arab nationalism and dominated the Arabic press at the time.Footnote 68 There is some evidence that Maloof travelled to Europe at or around the time of the conference. He submitted his petition for naturalization in July of 1912, a step that would have facilitated international travel, and by the fall of 1913 Maloof was performing as part of a trio that had “appeared in Paris, Vienna and all the large cities of Europe.”Footnote 69 Additionally, his brother-in-law George Ferris travelled to Mt. Lebanon via France that same summer.Footnote 70

Regardless of whether he was in Paris at the time of the conference, Maloof's name was so ubiquitous in the New York Arabic-language press that he was evoked as a rhetorical device within the discussion of the conference. In a wide-ranging 1913 editorial grab-bag entitled “Shadhrāt” (“Fragments”), which mostly decries ʿAbd al-Rahman Bey al-Yousef, a Syrian who attended a pro-Ottoman meeting in Paris simultaneous with the First Arab Congress (a move the author likens to “selling their mother”), an aside is made to address Alexander Maloof (Figure 5):

Figure 5. Maloof's “For Thee America” as rhetorical device. “Shadhrāt,” Mir'āt Al-Gharb, June 28, 1913.

The appearance of both the Egyptian Khedival march and “Sooriya al Watan” (Syria the Nation/Homeland), a new patriotic anthem, in his 1917 collection suggests he took that directive to heart.Footnote 72 Moreover, Maloof became invested not just in providing music to articulate the emergent political configurations being imagined in the mahjar but in the idea that this music should be flexible enough to facilitate different idioms of performance most relevant to muhājirīn around the world.

Soorya al Watan

Though the first published version of “Soorya al Watan” does not provide a composer attribution, mentioning only that the version is both “Arranged as played in the Orient and Harmonized,” a revised version published in 1925 clarifies that the music is by Maloof, with lyrics by Asad Milkie, another New York Syrian (see Appendix).Footnote 73

The lyrics praise Syria as the birthplace of Christianity and center of the moral universe and articulate the remembrance of Syria as a practice best engaged in through song:

This later arrangement of the piece with lyrics demonstrates the flexibility of Maloof's piano output for the muhājirīn: he includes both a “Western” arrangement with full harmonization, and a version of the tune “as played in the Orient,” with bass lines voiced in octaves, fifths, or single notes rather than full chords. The top left corner of the score advertises both versions for purchase on record and on piano roll.

Maloof recorded “Soorya'l Watan” on the Maloof label in 1922, and the incommensurability of that recorded performance with the piano roll version makes clear that Maloof intended his music to be performed and heard in different ways by different audiences. The recording features the “well-known muṭrib” Ilias (aka Louis) Wardini, accompanied by Maloof on piano, and anonymous musicians on ʿūd and violin.Footnote 75 The violinist is likely Naim Karakand, a Syrian musician who recorded extensively in New York before moving to Brazil in the 1930s.Footnote 76

Adhering closely to Maloof's 1925 version, the recording sheds light on how Maloof expected his Arabic melodies would be realized by Syrian musicians. The difference in metrical placement of the melody between the two published arrangements of the song reveals that Maloof conceived it more in relation to the dum and tak rhythmic patterns of Arabic music (implied by the piano left hand) than locations within a measure. The recording begins with solo piano as Maloof plays through the first half of the main melody twice, using the “as played in the orient” version with extensive octave doubling and right-hand ornaments, rather than the harmonization. The ʿūd and violin then join for the second half of the melody, the highest and climactic section of the verse (beginning at measure 15 “Mah-bit-ul War-ya” in Appendix), with the piano abandoning the melody in favor of a rhythmic left hand punctuated by the occasional chord. Upon the entrance of Wardini's voice, the piano drops out, allowing the violin and ʿūd to carry the accompaniment, the latter providing the rhythmic propulsion.

A comparison between the second half of the verse in the harmonized piano score and the same point in the sung recording is illuminating.Footnote 77 Whereas a tonal interpretation of the piano harmony is possible (a direct move to a subtonic VII chord in D minor), the recorded performance demonstrates the irrelevance of the tonal explanation, instead requiring analysis within the maqām system. Here, the tune is in maqām Bayāti , complete with sikāh, the second scale degree located on the quarter-tone between the E-flat and E natural. This note becomes most audible at the moment above, when the melody ascends in measure 15, and presents a temporary modulation to jawāb al-maqām (the upper octave of a maqām, or here a descending maqām Muḥayyar). The divergence from equal temperament is made explicit when the melody ascends to the buzrak (the upper E-half-flat) on “Mouthic-ki” in the violin and ʿūd, though here Wardini extends the melody upwards another step above the written apex, extending the descent back down the maqām.

The fact that Maloof's piano anthologies commonly included pieces to be played in maqāmāt (pl. of maqām) unavailable in equal temperament is made explicit in his 1928 collection Syrian, Oriental, & American Vocal and Instrumental Compositions, where he includes arrangements of bashraf and dūlāb (both instrumental genres) set in various maqāmāt.Footnote 78 Some of the titles of these pieces—such as “Bashraf Rasd” and “Doolab Rasd”—indicate maqāmāt (in these pieces, maqām “rasd” or rāst) that are not playable on the piano. Maloof even includes a piece like “Doolab Sega,” in which the tonic or asās of the maqām would be the note sikāh (E-half-flat).

The different mediums in which “Soorya al-Watan” exists—the 78-rpm recording sung by Wardini, the equal-tempered piano roll, and the two written arrangements—necessarily imply separate understandings of Maloof's composition. The fact that these different understandings were all produced directly by Maloof under his namesake companies demonstrates that not only was Maloof aware that his compositions would receive different performances depending on the medium and the audience, but that he embraced these different possibilities. The song was a tool to be used in a variety of musical configurations, all in the service of imagining possible political and social realities for Syrians around the world.

Moving beyond compositions with directly political lyrics, some pieces which became “standards” of the Arabic repertoire (to use Rasmussen's construction of a “standard” repertoire of songs routinely performed in Arab American concerts) were likely perceived as politically relevant to audiences in the 1910s and 1920s mahjar. For example “ʿal-Rozana,” a Levantine folksong that became a standard during the course of the twentieth century, performed and recorded by countless singers from bilād ash-Shām and beyond, appears in several of Maloof's collections.Footnote 79 As described by Saadallah al-Agha al-Qal ʿa, the song tells the story of an Italian ship (the Rozana) sent to Beirut by the Ottoman government on a mission of trade warfare, with the goal of driving Lebanese farmers out of business with below-market prices, a plan thwarted when the Aleppo tradesmen refused to purchase Ottoman goods and bought from the Lebanese farmers instead, forgoing profits.Footnote 80 In other versions it is an Italian ship which sinks on the way to relieve a famine in Beirut, or which arrives full of grapes and apples, the only crops that were already available. In yet other interpretations, “Rozana” is the name of a woman; in most readings, however, the song tells of a ship full of the promise of external aid which never arrives, or arrives in a form which causes more harm than good.Footnote 81

As greater Syria suffered from extensive famines during and after the First World War, this story about the failure of external “aid” would have been particularly poignant to Syrian muhājirīn.Footnote 83

As his composition and arranging output reflected the political tenor of the 1910s, so too did Maloof's concertizing reflect the political aims of the New York mahjar. Scanning the press for notices of his live performances reveals Maloof's ubiquity: at benefits for the Syrian and Armenian relief fund, the annual dinner of the Syrian Democrats association, political talks by visiting scholars at the New York Historical Society, a rally led by the US ambassador to Turkey, and a debate between the Syrian Pilgrim's Club and the Plymouth Young Men's Club on the issue of a literacy test for immigrants, to name a few.Footnote 84

Arabic newspapers during World War I brimmed with updates on the humanitarian crisis in Beirut, where the West's “Great War” was known as the ḥarb al-majā ͑a (war of famine), and where muhājirīn in the United States had already been sending a huge portion of their earnings home in remittances. Also central to their press coverage and advocacy was the plight of the Armenians fleeing genocide in Turkey in 1915. As fellow Christian subjects of the Ottoman Empire, there was a strong political affinity between Arab Christians and Armenians. The Syrian muhājirīn made every effort to bring this crisis into broader view, focusing especially on the plight of Armenians, and their joint efforts found traction with the broader US public. According to Herbert Hoover, during World War I, “The name Armenia was in the front of the American mind . . . known to the American schoolchild only a little less than England.”Footnote 85 In 1918 seventy-five thousand “four-minute men” organized by President Wilson's Committee on Public Information gave speeches on Armenian and Syrian relief in churches and Sunday schools.Footnote 86 The first Red Cross mission abroad was to assist Armenian refugees, especially in Beirut, which to this day has a large Armenian population. An independent Armenia was part of Wilson's political vision, but most of the language directed towards European American Christian audiences focused on charity for suffering co-religionists.Footnote 87 For the writers of the mahjar, however, the causes of Christian relief, Syrian independence, and anti-Ottoman activism were inseparable.

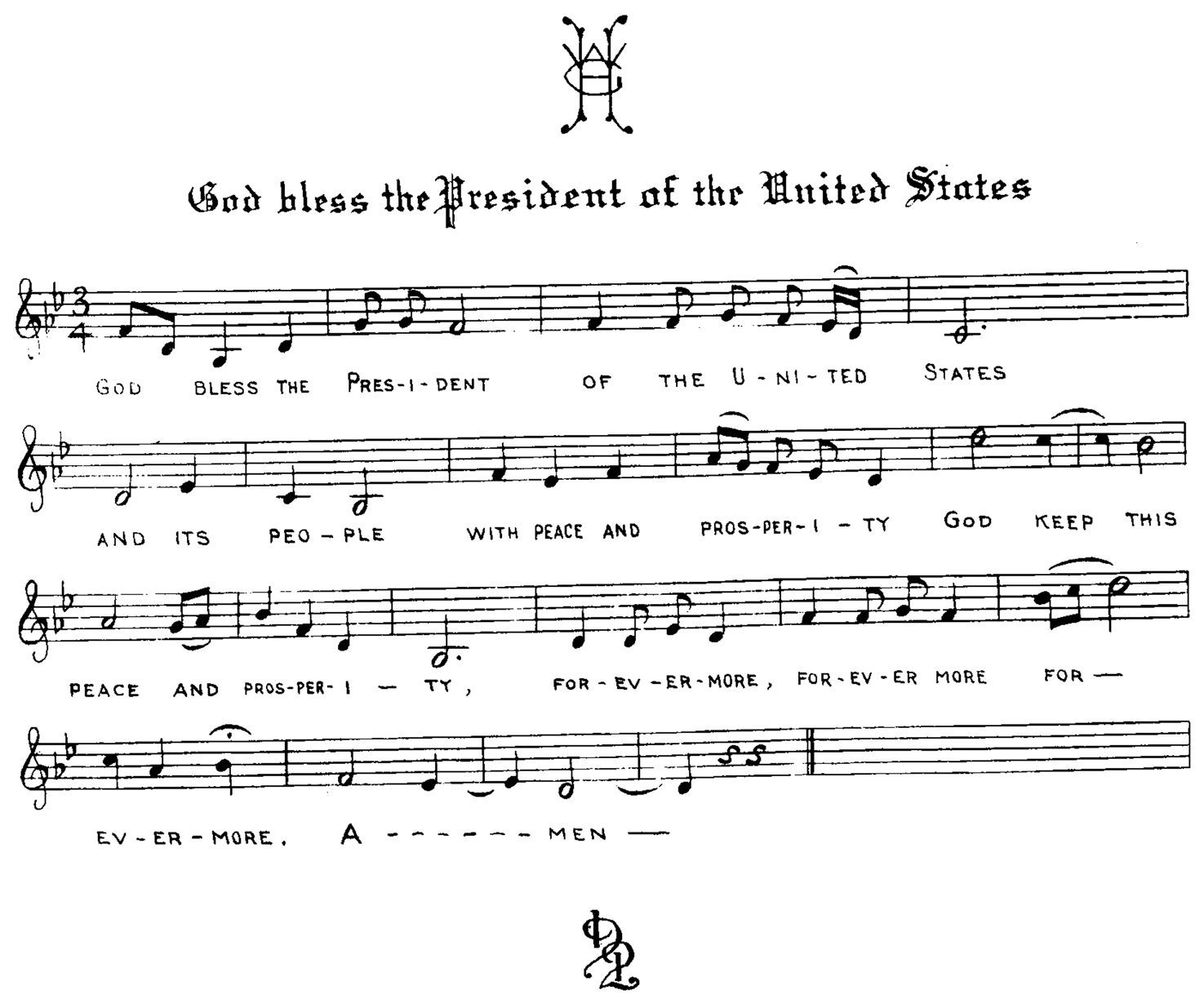

Indeed, the mahjar's primary rhetorical means of lobbying both the US government and American public became advocacy for Christian minorities suffering under the Ottomans. The multiple Christian denominations of the Ottoman diaspora were active in raising funds and distributing anti-Ottoman information, such as the widely distributed pamphlet Turkish Atrocities in the Black Sea Territories issued by Greek Orthodox Archbishop Germanos (Karavangelis), who took his regnal name from a nineteenth-century hero of the Greek Revolution against the Turks. The anti-Ottoman bent of the Orthodox clergy was widespread in this period. Metropolitan Germanos Shehadi, also from Zahle like Maloof, was acting bishop of the Syrian (Antiochan) Orthodox community in New York during the 1910s and 1920s. Known for his excellent singing voice, Shehadi recorded a number of sides for Saidaphon and even sent President Harding a musical invocation in 1921 upon his inauguration. Unsurprisingly, Shehadi was an acquaintance of Maloof, who arranged the music in Shehadi's Eight Arabic Songs and likely assisted with some of his other musical publications and recordings.Footnote 88

Figure 6. Metropolitan Germanos Shehadi Musical Invocation. Scan from Harding Library Archive, Ohio History Project.

The sounds of Maloof's piano, songs, and arrangements accompanied the public discourse on the need for assistance and independence for the Ottoman Empire's Christian minorities. However, he was simultaneously building a career within the mainstream Anglophone musical economy and listenership, composing and performing both identifiably Arab music and music that would have registered as ethnically unmarked or Anglo-American to that audience.

For example, Charles T. Griffes arranged Maloof's “A Trip to Syria” for western chamber orchestra in 1917.Footnote 89 That arrangement became part of the standard repertoire of Adolph Bolm's Ballet Intime, danced by Bolm and Roshanara.Footnote 90 “A Trip to Syria” represents a prime example of Maloof's engagements with the Orientalist trend in US popular music. Rather than drawing from the stereotypical images of the harem, the savage desert fighter, or the dervish, and in contrast to the voyeuristic tunes written by European American composers (e.g., “Rebecca came back from Mecca” and “My Turkish Opal from Constantinople”), the majority of the pieces recorded with Maloof's orchestra were named for places around the Middle East and North Africa.Footnote 91 These pieces appealed to European American desire for the exotic, but they served another purpose for members of those diasporas who heard their homes represented in tunes like “Cairo,” “Tunisia,” “Syria,” “Morocco,” “Baghdad,” “Kurdistan,” “Mt. Lebanon March,” “Ruins of Balbaak,” and “On the Beautiful Nile.” Rasmussen goes so far as to describe these titles as “reflect[ing] a sense of pan-Orientalism.”Footnote 92 Collectively, they also formed a kind of travelogue, introducing US listeners to unfamiliar places guided by a mixture of musical styles that were more familiar than the versions being performed in the Arab neighborhoods of New York. To this end Maloof even wrote the musical accompaniment for two “educational” silent film shorts for Columbia.Footnote 93

Arabness and Arab Women

The question of whether a Christian composer from Zahle would have considered himself personally “Arab”—that is, the object of the United States’ Oriental fascination—does not have a straightforward or universal answer. During the interwar period especially, one cannot assume that members of the US mahjar's educated class would have considered themselves Arab at all, much less associated themselves with the tropes of US Orientalist imagery. In addition to the question of whether Arabness precluded whiteness, the explicit differentiation between Arab and non-Arab (specifically, non-Arab Lebanese) did arise in mahjari political arguments. Salloum and Na`um Mokarzel (publisher of al-Huda), drawing on a Phoenicianist understanding of history most associated with Maronite Christianity, argued that Christian Lebanese genealogy and culture was historically Phoenician rather than Arab, and specifically, that the Lebanese impulse to navigate the seas towards the United States should be traced back to the sea-going Phoenicians, rather than to the Arabs.Footnote 94

Although most modern scholars reject the Phoenician argument, it retains currency today among some Lebanese. Maloof certainly would have known those arguments but would also have been familiar with the historical work of his relative ʿIssa Iskandar Maʿlūf, who traced their family back to a Yemeni (Arab) origin by way of the Hourani region of Syria, and noted that children of the Maloof line were known for “the fine relationship of the features, the blackness of the eyes (and their beauty), the blackness of the hair, and the other characteristics of the Arabs.”Footnote 95 Regardless, Maloof's own compositional output explicitly self-identifies his community as “Arab,” setting this question to rest in his particular case.

For example, his paean to the morals and industry of the women of the mahjar is titled “Ya Binat al-Arabi” (Oh Arab Girls):

Maloof's lyrics describe Arab women of the mahjar in terms familiar from other nationalist movements: as moral centers of the family and the nation, economic engines working tirelessly (achieving “the victories of men”), and maintainers of culture and honor, educating the next generations.Footnote 96 As Fahrenthold has described, “the notion that women had the power (and responsibility) to civilize, enlighten, and revitalize Syrian society emerged in the late nineteenth century,” and equivalent notions were widespread across national movements in the nineteenth century.Footnote 97

In contrast to some men of the mahjar such as Yousef Touma, who advocated for women rhetorically as “mothers of the nation” while attempting to subsume the civic and charitable work of women's groups (and especially the funds they raised) into a patriarchal nationalist movement, Maloof was more involved on a day-to-day level in the charitable, political, and artistic work by women that was so central to social and political life in the mahjar: he facilitated music for plays and performances organized and performed by women's groups in Little Syria, and the majority of his piano and composition students were women.Footnote 98 And while “O Arab Girls” clearly exists within that patriarchal vein of gendered nationalism, it also represents a starkly different depiction of Arab women from the sexualized one that prevailed in Anglophone music publishing.

Maloof did occasionally set English lyrics with women as subjects in tunes titled “Salome,” “Katerina,” “Egyptiana,” “Moonflower,” and “Orienta,” but the standard harem-girl images are notably absent on the sheet music covers bearing his name, and in the midst of a public market for sexualized Eastern femininity, Maloof for the most part avoided this mode of pandering to Orientalist demand in his own compositions (at least in those attributed to Alexander Maloof).Footnote 99 In both Arabic and English, Maloof set lyrics by others more often than his own, and we do not know to what extent he influenced the subject matter's lyrical treatment. However, just as the compositional techniques in his music differed according to its expected audiences, so did the political content of his English and Arabic language output.

The possibilities and constraints present in communicating in Arabic and English idioms were fundamental to the artistic and political output of the New York mahjar, as Waïl Hassan describes for Ameen Rihani and Khalil Gibran, two famous writers of a slightly older generation of muhājarīn:

Obviously, when writing in Arabic, Rihani and Gibran not only had a different agenda, but also enjoyed greater discursive latitude in that, first, they did not have to explain Arab culture to Arabic readers; secondly, they were not expected by their readers to pose as Oriental spokesmen; and thirdly, they did not have to abide by discursive strictures imposed on their cultures by a conquering knowledge system—with its stereotypes, typologies, culturalist and racialist frames of reference, privileged texts and modes, and so forth—even when they could not free themselves entirely from its powerful imprint. They write within an Arabic cultural discourse and could ignore or dismiss simplistic or offensive Orientalist descriptions, or they could boldly and directly challenge their imperialistic underpinnings. When writing in English, however, they had to couch their message in ways that guaranteed, or at least increased, the likelihood of its acceptance – of their acceptance as writers—by American readers.Footnote 100

Perhaps the most intriguing example of how Maloof navigated different idioms and audiences comes in a piece that employs both of the standard depictions of Middle Eastern femininity—as the exoticized object of Orientalist projection (for Anglophone audiences) and the feminine symbol of national honor (for oppressed minority groups of the Ottoman Empire). The piece is “Armenian Maid,” a tune Maloof wrote (using his occasional pen name of M. Alexander) to lyrics by Wilbur Weeks.

Armenian Maid

The cover art to “Armenian Maid” (an “Oriental Song and Fox-Trot”) is a grab bag of images from Orientalist fantasy: a smiling woman in Salome drag seductively pulling at her necklace; background dancers in outfits that invoke belly dancing on top and Sufi men's robes from the waist down; and silhouettes of Istanbul's skyline backed by North African palm trees.Footnote 101

Figure 7. “Armenian Maid” cover. M. Alexander and Wilbur Weeks, “Armenian Maid: Oriental Song and Fox-Trot,” New York: E. T. Paull Music Co., 1919. Scan from The Lilly Library at Indiana University.

In stark contrast to the smiling cover art, the song is a tragic one, dedicated to Aurora (originally Arshaluys) Mardiganian, the “Sole Survivor of the Million Armenian Maids Taken by the Turks in the Great Armenian Massacres.”Footnote 102 The song was a tie-in meant to drum up publicity for the 1919 silent film Auction of Souls (also known as Ravished Armenia) depicting Mardiganian's story and the tragedy of the Armenian genocide.

Figure 8. “Armenian Maid” inside cover. Scan from The Lilly Library at Indiana University.

The inside cover of the sheet music features the “Message of an Armenian Maid to all Sweethearts Everywhere.” Purportedly written by Mardiganian, it veers wildly between language describing her plight as a survivor of genocide and language reinforcing the “Armenian Maid's” status as a romantically inclined ingénue.

I am almost the only Armenian Maid left alive of all those who used to live and love and play in my Armenia. I had a sweetheart too, who used to sing to me just such pretty songs as this. And I used to watch for him to come into my father's garden every night when the moon came up, and I used to make sweet plans for the time when we could walk together in a garden all our own. But the Sultan sent his soldiers through Armenia to take away all the pretty Armenian Maids, that they might be sold into the harems of the Turks. They took me too, and killed my sweetheart just as they killed the sweethearts of all the other maids who were carried away. I was the only one who escaped to this beautiful America, but I have no sweetheart now; no one to sing pretty songs to me.Footnote 103

Several scholars of the Armenian diaspora have taken note of “Armenian Maid.” In her excellent monograph, Music and the Armenian Diaspora, Silvia Angelique Alajaji remarks that apart from its introduction, which “signifies the Orient in its melodic-minor mode, harmonic progressions, ornamentation, and predominant use of the flat VII,” the tune is a “rather unremarkable, straightforward fox-trot.”Footnote 104 In Ravished Armenia and the Story of Aurora Mardiganian, Anthony Slide dismisses the song as “difficult to forget, but certainly well worth the effort.”Footnote 105 In 2018 researcher Geghard Arakelian, unable to find a recording of the song, even organized a group of musicians and recording engineers to perform and record it, documenting the process on video.Footnote 106

Understandably, none of these scholars were aware that M. Alexander was not simply another European American songwriter cashing in on the Orientalist trends in popular music, but rather a mahjarī composer who spent years of his childhood in Beirut, a city whose population, including tens of thousands of Armenian refugees, was still suffering from food shortages after the war and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 107 The confusion over A. Maloof and M. Alexander is understandable. Both names collaborated with lyricists Wilbur Weeks and D. Frank Marcus, but when M. Alexander wrote a turkey trot entitled “Ticklish Sensation” in 1914, also published by E. T. Paull, the copyright indicated “by Maloof Alexander.”Footnote 108 Similarly, the back cover to Maloof's 1925 song “Twilight,” lists “6 New Maloof Songs” for sale, of which the first three (with non-descript English titles) are listed with “music by M. Alexander,” while the next three “oriental”-themed songs (“Egyptianna,” “Orienta,” and “Twilight”) are attributed to Alexander Maloof.Footnote 109 While we do not know the precise reason for the use of a pseudonym, it is easy to imagine possible scenarios. Based on the “Twilight” advertisement it seems at least plausible that Maloof or his publisher used M. Alexander when they wanted a name ethnically marked as European American. Interestingly, while Maloof wrote many songs with English lyrics under his own name that were not musically or lyrically marked as Arab or Eastern, of the seven pieces I found attributed to M. Alexander, the only one with any non-Western indications in title or style is “Armenian Maid.”

Unlike the majority of US composers of the Orientalist style, Maloof was intimately familiar with the musical culture alluded to in “Armenian Maid.” Maloof frequently played with Armenian musicians like violinist Haig Gudenian in small groups, parties, and his “Oriental Orchestra.” In addition, he performed in New York's Armenian churches, arranged Armenian folk songs for his compilations, and composed an original “Armenian March” for piano. Nevertheless, it would take significant effort to differentiate “Armenian Maid” from other songs in the popular “Oriental Foxtrot” style of the 1910s. Maloof does include certain aspects associated with his more “Oriental” music in “Armenian Maid,” such as moments of octave doubling to mimic the ʿūd. He also places the “exotic” augmented 2nd between the flat 6 and major 7th scale degrees, rather than the 5th and the flat 7th, as Hamberlin found in most “Salome” melodies.Footnote 110 Overall, though, the piece displays a more standard tonal trajectory than the maqām-directed development of the folk songs Maloof arranged for his Syrian-American audience.Footnote 111

“Armenian Maid” was clearly meant to appeal to a broad US audience, using the images and some of the musical language of the “Oriental” craze. But the purpose behind this piece was not simply titillation in service of a good cause, as it might have been for another M. Alexander. For al-Ustadh Iskandar Effendi al-Maloof, the sympathy, desire, and fascination evoked in Anglophone US audiences by this disturbing conflation of the Salome fantasy with the Armenian Genocide would also have the goal of preventing a similar fate for the families back in Beirut, starving even as he wrote the song. Furthermore, within the mahjar, the goals of mobilizing aid for suffering populations of Christians in the formerly Ottoman territories were by 1919 linked to garnering US support for an independent state.

We must then consider the act of composing the song as situated not just within European American discourses about the “Orient” but within mahjar discourses about the political fate of Syria, Lebanon, and the broader post-Ottoman world and the potential role of the United States in establishing that political order. Just as the Arabic-language patriotic songs that Maloof composed in the 1910s were potential tools with which muhājirīn could perform new and emergent social and political configurations, the musical idiom of Anglophone Orientalist music was itself a tool for Maloof and other musicians of the mahjar, a lever with which to move the rock of US public opinion.

Conclusion

In a 1931 interview, Maloof said about his music, “we try to Americanize the Syrians,” but his educational mission was, in fact, multifaceted.Footnote 112 His career and music relied on the transatlantic connections of the turn-of-the-century mahjar to encourage Syrians to remember the language and culture of their homeland while mastering and refining the language and idioms of US music. At the same time, his music tried to turn the United States into a country that was a bit more Syrian. By introducing audiences to more of the Arab world, he used fascination with the exotic to his advantage, invoking sympathy or outrage and educating the US populace about the geography and plight of the Middle East with the hope of engaging Americans more positively with the politics and people of the region.

Maloof's “Oriental” popular songs, and even his arrangements of Syrian songs for Syrian audiences, are more western in style than the music of other Syrian musicians who recorded at this time. In the Syrian press, however, Maloof's music was not considered an unequivocal adoption of western styles. Writing in The Syrian World, critic Ameen Rihani said:

The compositions of Alexander Malouf . . . are evidences of the Syrian's power of assimilative and creative expression. . . . Western forms are made to yield to the Orientalism of his spirit. . . . The wistful appeal, the distilled, as it were, exoticism, the gesture that has in it the grace and languor of an ancient tradition, these are noteworthy features of the compositions of Malouf.Footnote 113

The output of Maloof and his Oriental Orchestra certainly displays Rihani's “exoticism,” and Maloof himself was not shy about invoking exoticism in the press when promoting his work. However, just as the subtleties of his music for the mahjar are reduced towards caricature when presented to the US public in “Armenian Maid,” an examination of Maloof's early career demonstrates that a focus on the European American production and consumption of “Oriental” sounds obscures an altogether different set of discourses and goals operating for and on behalf of the communities of the mahjar.

To conclude, I would like to examine a moment from Maloof's representation in the English language press in light of those dual valences. In 1926, in an interview with an English-language paper describing Syrian music and his Oriental Orchestra, Maloof stated that “Hopelessness is the predominant quality of Oriental music.” Perhaps this invocation of hopelessness was a cynical, exotic appeal to non-Arab audiences. Perhaps it was an unsubtle translation of the Arabic poetic and musical aesthetic of ḥuzn or “painfully sweet longing.” Perhaps it was a commentary on the emotional state of the mahjar as the Levant was carved up by European colonial powers. Certainly that meaning would have rung true for many Syrians in New York, where initial hopes of an independent Syrian state, and then for an US mandate in Lebanon, were dashed by the revelation of the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the imposition of the French/British Mandate System in the Levant.

While it might have slotted into a half-dozen ongoing conversations and narratives in the mahjar, Maloof's statement, “Hopelessness is the predominant quality of Oriental music,” was also picked up as a wire item in the US English press. Reprinted by newspaper after newspaper, it was a fleeting snippet of a larger conversation, broadcast across the United States as the essential statement about a world-spanning musical culture, reduced to a moment of Orientalist ephemera.

Read through the lens of the Orientalist economy of the consumption of Arabness by European American audiences, this characterization of “Oriental music” seems a straight-forward appeal to exoticism, coming from a composer whose compositional output and professional activity were by 1926 primarily focused on European and European American idioms. However, viewed through the lens of the early twentieth-century mahjar musical and political discourses, hopelessness might be something different, the expression of thwarted dreams of an independent national homeland. Either view is a projection; but the task of decentering European American audiences in our understanding of the musical cultures in the United States opens up and, indeed, requires another set of possibilities for telling this US story.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2