Introduction

Bone formation and repair rely on the regulated induction of new blood vessels within a growth zone (Ref. Reference Wang1). The intricate role of angiogenesis in bone formation, beyond that of simply providing nutrients and oxygen to proliferating tissue, displays a temporal and spatial interdependence with osteogenesis (Ref. Reference Schipani2). The molecular mechanisms that couple these two processes are being discovered and exploited for therapeutic and tissue-engineered approaches for bone regeneration. Local delivery of angiogenic cytokines, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), into repairing bone or within bone bridging scaffolds has shown promising results (Ref. Reference Keramaris3). However, these methods have several potential drawbacks, slowing clinical application, such as cost, stability and concerns surrounding super-physiological doses of bioactive proteins.

Tissue hypoxia is a critical driving force for angiogenesis and is under the control of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway (Ref. Reference Maes, Carmeliet and Schipani4). Activation of the HIF pathway stimulates the transcription of multiple hypoxia response genes of which VEGF is a major target (Ref. Reference Riddle5). Additionally, in bone, the HIF pathway may also independently modulate osteogenic precursor recruitment and subsequent function at sites of bone formation (Ref. Reference Arnett6). Manipulation of hypoxic signalling for tissue regeneration is a rapidly growing area of multi-disciplinary research, and both genetic and pharmacologic strategies have recently been investigated for bone repair with exciting results. Critical to the control of cellular HIF activity is the discovery of oxygen-sensing hydroxylase enzymes that destabilise HIF in normoxic conditions. Several small molecules of low cost and proven clinical safety profiles have been found to repress these enzymes independently of oxygen status resulting in overexpression of HIF and subsequent strong angiogenic and osteogenic responses when delivered in vivo. This review provides an overview of the role of the hypoxic signalling pathway in bone regeneration. Current strategies for the manipulation of this pathway for enhancing bone repair are presented with an emphasis on recent pre-clinical investigations. These findings suggest promising approaches for the development of therapies to improve bone repair and tissue-engineering strategies.

Hypoxia-inducible factors

HIFs act as cellular oxygen sensors that induce a response to low oxygen tension (Refs Reference Maes, Carmeliet and Schipani4, Reference Wang and Semenza7). HIF is a αβ heterodimeric transcription factor that comprises three functionally nonredundant α subunits; HIF-1α, HIF-2α and HIF-3α and one HIF-1β subunit (Ref. Reference Wan8). Both α and β subunits of HIF are constitutively expressed. However, the β subunit is most often present in excess, whereas the functional expression of the α subunit is regulated by an oxygen-dependent post-translational mechanism (Ref. Reference Wang1). In well-oxygenated tissues (O2tension >5%), HIF-α displays one of the shortest half-lives (<5 min) among cellular proteins (Ref. Reference Schipani2). Under this condition, specific prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes hydroxylate proline residues in the oxygen-dependent domain (ODD) of the HIF-α subunit (Ref. Reference Jaakkola9). This reaction mediates the rapid binding of the Von Hippel–Lindau tumour suppression protein (pVHL) that subsequently targets HIF-α for E3-ligase-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (Refs Reference Maxwell10, Reference Kallio11) (Fig. 1). Under hypoxic conditions, the enzymatic activity of the PHDs is suppressed resulting in the accumulation of cytoplasmic HIF-α and subsequent translocation to the nucleus, where it dimerises with the β subunit (Ref. Reference Kallio12). Upon the recruitment of various other transcriptional co-activators this complex binds to hypoxia response elements within the promoter area of hypoxia-regulated genes to induce transcription (Ref. Reference Kallio11). In addition to stabilising HIF-α, hypoxia also promotes the ability of the HIF-α C-terminal transactivation domain (CAD) to interact with its major transcriptional coactivators such as p300 (Refs Reference Gu, Milligan and Huang13, Reference Lando14). Under normoxia an asparaginyl hydroxylase, factor-inhibiting hypoxia-1 (FIH-1), hydroxylates a conserved asparagine residue within the CAD thus inhibiting the ability of HIF-α to recruit its transcriptional apparatus (Ref. Reference Lando14).

Figure 1 HIF-α regulation. In well-oxygenated tissues HIF hydroxylases, PHDs and FIH downregulate the HIF-α subunit and decrease its transcriptional activity. PHDs hydroxylate proline residues in the ODD of the HIF-α subunit. This reaction mediates the binding of the von Hippel–Lindau tumour suppression protein (pVHL) that subsequently targets HIF-α for E3-ligase-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. FIH hydroxylates a conserved asparagine residue within the CAD thus inhibiting the ability of HIF-α to recruit its transcriptional apparatus. Under hypoxia, the enzymatic activity of PHDs and FIH is suppressed resulting in the nuclear transportation of HIF-α and the formation of an active transcription complex. Reprinted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd. Schofield and Ratcliffe (Reference Schofield and Ratcliffe16).

Work by Wang and Semenza, provided some of the initial evidence for the direct role of HIFs in the transcriptional regulation of gene expression in response to hypoxia (Ref. Reference Wang and Semenza7). To date, more than 100 putative HIF target genes have been identified (Refs Reference Greijer15, Reference Schofield and Ratcliffe16). These genes function in a multitude of biological processes including energy metabolism, angiogenesis, erythropoiesis, cell survival, apoptosis and pH regulation (Ref. Reference Schipani2). HIF-1α and HIF-2α have both overlapping and unique biological functions (Ref. Reference Nagel17). It appears that regulation of expression of enzymes of the glycolytic pathway is unique to HIF-1α, whereas control of erythropoiesis is specific to HIF-2α. However, angiogenic stimulation is common to both (Refs Reference Keith, Johnson and Simon18, Reference Hu19). Less is known about HIF-3α, which seems to suppress hypoxia-inducible gene expression in certain organs (Refs Reference Makino20, Reference Hara21).

Role of HIF-1a in bone formation and repair

Osteogenic–angiogenic coupling

During endochondral bone formation, chondrocytes within the centre of growth plates proliferate and synthesise an avascular extracellular matrix. As these cells migrate towards the growth plate periphery they differentiate into hypertrophic chondrocytes and release molecular signals, including the pro-angiogenic cytokine VEGF, that stimulate vascular invasion of the growth plate (Ref. Reference Zelzer and Olsen22). The induction of blood vessels coincides with the migration of osteoclastic precursors and osteoblasts that remodel the cartilaginous template and lay down new bone matrix (Ref. Reference Maes23). Bone repair recapitulates this process (Refs Reference Claes, Recknagel and Ignatius24, Reference Gerstenfeld25) and in the initial phase of endochondral bone healing, inflammatory signals within the fracture site stimulate the recruitment of mesenchymal progenitor cells that differentiate into chondroblasts and initiate callus formation (Ref. Reference Claes, Recknagel and Ignatius24). Following callus mineralisation, hypertrophic and hypoxic chondrocytes signal for vascular invasion of the callus which is followed by callus remodelling into woven bone by osteoclasts and osteoblasts (Ref. Reference Claes, Recknagel and Ignatius24).

In both skeletal development and bone repair VEGF-dependent blood vessel invasion into avascular cartilage is a critical step to the formation of bone (Ref. Reference Wang1). Gerber et al. showed that administration of a VEGF receptor antibody, completely blocked neoangiogenesis in the growth plates of 24-day-old mice and resulted in decreased trabecular bone formation. Subsequent termination of the anti-VEGF treatment was followed by capillary invasion, normalisation of the growth plate architecture and restoration of bone growth (Ref. Reference Gerber26). Similarly Street et al. demonstrated that inhibition of VEGF in a mouse fracture model dramatically reduced angiogenesis, callus mineralisation and bone formation (Ref. Reference Street27). Moreover exogenous VEGF administration has been shown to enhance bone formation in both mice and rabbit fracture models (Refs Reference Street27, Reference Geiger28). A close temporal and spatial relationship exists between formation of bone and vascular proliferation. Osteoblast precursors and endothelial cells may be simply attracted to the same or simultaneous chemo-attractants produced by hypertrophic cartilage such as VEGF (Refs Reference Wang1, Reference Zelzer and Olsen22). However, it is now becoming established that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (Refs Reference Crisan29, Reference Corselli30) and early-differentiated osteoblast precursors (Refs Reference Maes23, Reference Sacchetti31) reside within the walls of blood vessels and are directly channelled into developing and regenerating bone areas during angiogenesis. In addition, invading blood vessels also themselves release factors termed angiocrine signals that affect cell differentiation, bone growth and homoeostasis (Ref. Reference le Noble and le Noble32). This coupling of angiogenesis to osteogeneisis appears to require specific cross-talk between osteoprogenitors, osteoblasts, osteoclasts and the endothelial cells at a variety of levels (Ref. Reference Wan33). Recently HIF-1α has been shown to be central to this coupling phenomenon regulating both VEGF-dependent recruitment of vessels into metabolically active areas of bone development and also influencing the release of angiocrine signals from the vessels themselves promoting osteoprogenitor cell recruitment and activity in areas of invading vasculature.

HIF-1α couples angiogenesis and osteogenesis

Classic studies by Birghton et al. demonstrated that pericellular reduction in oxygen tension is a hallmark of the condition within the epiphyseal plates during bone development and is maintained within a fracture callus during repair (Refs Reference Brighton and Heppenstall34, Reference Brighton and Krebs35). Since then, the intimate relationship of HIF-1α and to a lesser extent HIF-2α, to the regulation of osteogenic–angiogenic coupling in bone development, haemostasis and repair has been extensively studied (Refs Reference Riddle5, Reference Wan33, Reference Provot36, Reference Wang37, Reference Pfander38, Reference Shomento39, Reference Saito40, Reference Araldi41, Reference Amarilio42). The research group of Thomas Clemens performed some of the landmark findings on the subject. Initially, the group showed that primary mouse osteoblasts expressed all of the components of the HIF regulatory pathway. During osteoblast culture under hypoxia (2% O2), increased nuclear translation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α was evident, leading to upregulation of VEGF mRNA. Mice overexpressing HIF-1α by conditional disruption of pVHL in osteoblasts had striking increases in post-natal femoral bone volume compared with controls (Ref. Reference Wang37). Increased osteoblast numbers were seen in the mutants, whereas osteoclast numbers remained the same compared with control mice. In contrast, mice lacking HIF-1α in osteoblasts had femurs with markedly decreased diameters and lower osteoid volume (Ref. Reference Wang37). Importantly, the bone volumes in these two mutant mice directly correlated with the amount of bone vasculature as measured by micro-angiography (Ref. Reference Wang37). In further work, the group showed that mice with osteoblast HIF-2α knockdown had only a modest decrease in trabecular bone volume compared with those lacking HIF-1α (Ref. Reference Shomento39). However, VEGF expression and blood vessel formation showed similar decreases in the two models. While both isoforms function to elevate VEGF expression, certain expression patterns of HIF-1α may also modulate bone formation by exerting direct actions on osteoblasts (Ref. Reference Wang1). Overall the results of the Clemens group have demonstrated a model for the role of the HIF-1α pathway in bone formation. Osteoblasts residing in the nascent bone upregulate HIF-1α in response to hypoxia, which activates target genes that are secreted into the micro-environment and stimulate neo-angiogenesis, which in turn brings in new progenitor cells and nutrients (Refs Reference Schipani2, Reference Wang37) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Regulation of osteogenesis–angiogenesis coupling by HIF. In hypoxic conditions osteoblasts upregulate HIF transcriptional activity, resulting in the activation of multiple hypoxic response genes of which VEGF is a major target. VEGF acts on endothelial cells to induce angiogenesis. This process increases the supply of oxygen and nutrients required for osteogenesis. Additionally, stem cells and osteoblast precursors residing within the walls of blood vessels are directly channelled into regenerating bone areas during angiogenesis. Invading endothelial cells are also responsible for the secretion of signals that generate micro-environments specialised for osteogenesis. Reprinted with permission from Wiley Materials. Schipani et al. (Reference Schipani2).

A similar mechanism is implemented in bone repair where the abrupt disruption of oxygen and nutrient supply within a fracture site results in upregulation of HIF-1α (Ref. Reference Riddle5). Komatsu et al. demonstrated temporal upregulation of HIF-1α as well as of VEGF at both transcriptional and translational levels in the fracture callus of rat femora (Ref. Reference Komatsu and Hadjiargyrou43). Work from the Clemens Laboratory further established the role of HIF-1α in skeletal repair using a mouse model of tibial distraction osteogenesis (Ref. Reference Wan8). Using their established genetic mouse models for modulating HIF-1α expression in osteoblasts, they showed significantly increased vascularity and new bone formation within the distraction gap in HIF-1α overexpressing mice (P < 0.05). This outcome was VEGF dependent and eliminated by secondary administration of VEGF receptor antibodies. Mice lacking HIF-1α in osteoblasts demonstrated opposite effects (Ref. Reference Wan8).

While HIF-1α signalling is an essential upstream regulator of blood vessel growth, HIF-1α activity is also central to the mechanisms by which endothelial cells function to generate micro-environments specialised to induce osteoprogenitor recruitment and osteogenic activity (Ref. Reference Kusumbe, Ramasamy and Adams44). Recently Kusumbe et al. demonstrated that the capillary endothelium within bone vasculature of mice tibia demonstrates a unique spatial and phenotypic heterogeneity distinguished by two subpopulations of endothelial cell that they termed type H cells and type L cells (Ref. Reference Kusumbe, Ramasamy and Adams44). Subsequent immunostaining revealed that osteoblastic precursor cells as well as osteoblasts were selectively positioned around the type H but not the type L cell endothelium. Moreover, these type H endothelial cells displayed a genetic upregulation of multiple growth factors with known roles in osteoprogenitor cell survival and proliferation. Using endothelial selective knock-down and upregulation studies, the authors identified that the expression of HIF-1α is a key positive regulator only of the type H cells (Ref. Reference Kusumbe, Ramasamy and Adams44). HIF-1α overexpression led to pronounced expansion of the type H endothelium and higher numbers of local osteoprogenitor cells. Increased overall bone mass was also evident in these mutants. Interestingly the expected decline of osteoprogenitor cells in the long bone of aging mice correlated with the loss of the H subset of endothelial cells without a respective decline in type L cells. Pharmacological stimulation of HIF-1α in these aged mice resulted in re-expansion of the type H endothelium, increased levels osteoprogenitor cells and overall significantly increased bone mass over controls (Ref. Reference Kusumbe, Ramasamy and Adams44).

Effect on progenitor cell recruitment

The work by Kusumbe provides evidence that HIF-1α activation influences genetic cascades effecting osteoprogenitor cell recruitment and activity. This effect may be partially through the upregulation of VEGF, which is known to exert some of its effect on bone growth independently of angiogenesis through a direct action on stem cell recruitment and differentiation (Refs Reference Wang1, Reference Zelzer and Olsen22). For example, Lui et al. showed that intracellular VEGF expression within MSCs drives differentiation towards osteoblasts rather than adipocytes via an intracrine signalling loop (Ref. Reference Liu45). In addition to VEGF, hypoxic signalling governs stem/progenitor cell recruitment through activation of stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) (Refs Reference Ceradini46, Reference Kitaori47). SDF-1 is responsible for stem cell chemotaxis and migration through an interaction with its cell surface receptor CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) (Ref. Reference Marquez-Curtis and Janowska-Wieczorek48). Specifically in bone, SDF-1 is induced within periosteal cells of injured bone and promotes repair by the recruitment of local as well as circulating bone marrow derived osteoblastic precursors (Refs Reference Kitaori47, Reference Otsuru49). SDF-1 has been investigated for bone tissue engineering applications and most recently has been shown to enhance bone formation within scaffolds for critical sized cranial defects by increasing the recruitment of MSCs (Ref. Reference Liu50). SDF-1 expression is also involved in the recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) into repairing tissues. Recent hypotheses suggest the importance of these cells in enhancing tissue re-vascularisation via de novo vessel formation (vasculogensis) rather than vessel sprouting and invasion from surrounding intact vessels (angiogenesis) (Ref. Reference Ceradini and Gurtner51). Cerandi et al. first demonstrated evidence that HIF-1α stabilisation is directly responsible for the upregulation of SDF-1 in injured tissues in response to sudden hypoxia (Ref. Reference Ceradini46). Additionally increased expression of HIF-1α within MSCs and HSCs results in upregulation of CXCR4 expression (Ref. Reference Staller52) suggesting that activation of the HIF-1α pathway results in enhancement of both the trafficking stimulus (SDF-1) and receptor (CXCR4) for progenitor cell recruitment.

Effect on osteoblasts and osteoclasts

In vitro work has attempted to determine direct effects of hypoxia and hypoxic signalling on self-regulatory activity within osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Phenotypic studies examining the proliferation and differentiation of pre-osteoblasts and primary osteoblasts cultured under variable oxygen levels have demonstrated contrasting and inconclusive results (Refs Reference Hirao53, Reference Utting54, Reference Steinbrech55, Reference Matsuda56). Similarly, genetic profiling studies examining modulation of crucial signalling pathways in osteoblasts in response to hypoxia and HIF-1α activation report directly contradictory findings (Refs Reference Genetos57, Reference Chen58). There is no clear consensus on the overall biological response of HIF-1α expression on autonomous osteoblast activity, although secretion of VEGF from osteoblasts in response to hypoxia has not been discounted.

The differentiation of monocytes into bone resorbing osteoclasts is crucial in the initial stages of fracture repair. Local accumulation of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) stimulates osteoclast differentiation. RANKL signalling is one of the major molecular differentiating factors between autograft assisted bone healing over allograft, suggesting the necessity of robust osteoclastic activity for conferring autograft properties to allograft and synthetic bone graft substitutes (Ref. Reference Ito59). Recent evidence points towards hypoxic signalling being intimately involved in the differentiation and activity of osteoclasts (Ref. Reference Arnett6). Arnett et al. found that hypoxic conditions significantly increased the number and size of osteoclasts that formed from RANKL/M-CSF-treated 7-day mouse bone marrow cultures. The effect was most dramatic at 2% O2 and resulted in a 21-fold increase in resorptive activity (P < 0.001) (Ref. Reference Arnett60). Similar results were demonstrated using cultures of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Ref. Reference Utting61). This effect could be HIF-1α dependent, as silencing of HIF-1α during hypoxic culture of mature human osteoclasts ablated the increased resorptive activity (Ref. Reference Knowles and Athanasou62), while the addition of HIF-2α siRNA had variable effects (Ref. Reference Knowles63). Moreover, activation of HIF-1α through administration of PHD enzyme inhibitors stimulated osteoclastic resorption two to 3-fold in assays of lacunar dentine resorption (P < 0.001) (Ref. Reference Knowles63). Conversely other results show inhibitory effects of PHD inhibitor mediated HIF-1α activation on osteoclastogenesis and upregulation of apoptotic mediators in osteoclasts (Ref. Reference Leger64). From the above findings it is possible to infer that HIF-1α is more directly involved in osteoclast mediated resorption rather than early osteoclastogenesis and proliferation. Bone resorption is energy demanding, and osteoclasts undergo a metabolic switch during the course of differentiation so as to meet the increased demand in ATP (Ref. Reference Indo65). HIF-1α expression has been postulated to coordinate this metabolic adaptation by increasing the transcription and subsequent expression of glucose and glutamine transporters to facilitate glycolysis and glutaminolysis (Ref. Reference Indo65).

Therapeutic strategies targeting HIF-1α

Activation of the HIF-1α signalling pathway results in angiogenesis, recruitment of progenitor cells and even has direct effects on differentiation and activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Substantial progress has been made in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which oxygen content regulates the levels and activity of HIFs. The discovery of the indispensible role of oxygen sensing hydroxylase enzymes (PHD and FIH-1) in modulating expression and activity of HIF has sparked interest in potentially promising therapeutic strategies in multiple clinical fields and most recently in bone healing.

Gene therapy

The importance of several discrete HIF-1α amino acid residues on its regulation has generated interest in gene therapy strategies to create HIF-1α constitutively expressing transplantable stem cells for bone regeneration. In humans, pVHL mediated HIF-1α degradation is dependent on the hydroxylation of Pro402 and Pro564 within the 200-amino-acid oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODD) (Ref. Reference Huang66). Hydroxylation of a third amino acid (Asn803), found at the C-terminal transactivation domain of FIH-1, blocks the interaction of HIF-1α with its nuclear co-factors thereby repressing transcription of HRE genes (Ref. Reference Mahon, Hirota and Semenza67). In a series of publications, Zou et al. reported several HIF-1α DNA constructs with specific mutations aimed at abrogating the ability of PHD and FIH-1 to suppress HIF-1α activity in normoxic conditions (Refs Reference Zou68, Reference Zou69, Reference Zou70). Bone marrow MSCs transduced with these genes were subject to in vitro culture and subsequently seeded within ceramic or gelatin scaffolds for evaluation in rat cranium critical sized defects (Refs Reference Zou68, Reference Zou69, Reference Zou70). The results showed a marked increase in transcription and translation of multiple pro-angiogenic factors in cultured cells by qPCR and Western Blot analysis. Alkaline phosphate expression as well as Alizerine Red staining was also significantly observed in culture demonstrating the ability of HIF-1α activation to promote the osteogenic activity of BMSCs (Refs Reference Zou69, Reference Zou70). Eight weeks after BMSC delivery with gelatin scaffolds there was markedly increased new bone formation within the scaffolds seeded with HIF-1α BMSCs as compared with nontransduced BMSCs (Micro-CT bone volume fraction 72 versus 17.5%, P < 0.01) (Ref. Reference Zou70). Micro-angiography showed significantly increased vascularity (vessel number and volume P < 0.01) (Refs Reference Zou68, Reference Zou70). HIF-1α BMSCs seeded within calcium–magnesium phosphate cement accelerated degradation of the scaffold and increased new bone formation within the scaffolds pores as compared with controls (Ref. Reference Zou69).

HIF-1α transduced BMSCs have also been used to promote the repair of the necrotic tissues in a rabbit model of corticosteroid-induced femoral head osteonecrosis (Ref. Reference Ding71). After core decompression of the necrotic area of the femoral head, fluorescently labelled transplanted cells were shown to survive for at least 4 weeks after the transplantation. Using micro-angiography, micro-CT and histomorphometric analysis, Ding et al. showed significantly (P < 0.01) higher vasculature, increased bone volume and improved bone quality within the femoral head following HIF-1α BMSC transplantation compared with nontransduced BMSCs (Ref. Reference Ding71).

While HIF-1α gene therapy shows some experimental promise, multiple barriers exist to translate the technology into clinical applications. As with any genetic manipulation of osteogenic and angiogenic factors for tissue repair, the ethical considerations and potential tumorigenic risks must be properly taken into account. Moreover, given the need for cell expansion, a process that requires several weeks of culture in a laboratory, the efficacy, cost and practicality of using transgenic cell therapy currently limits clinical applications (Refs Reference Ma72, Reference Murray73).

Hypoxia mimicking agents

One of most intriguing aspects in developing therapeutics that target HIF-1α is the discovery of small molecules that can effectively stabilise HIF-1α in normoxic conditions by blocking the hydroxylation reactions of PHD and FIH. The PHD proteins are members of a larger superfamily of oxidative enzymes that require molecular oxygen and the citric acid cycle intermediate 2-oxoglutarate (2OG) as co-substrates and depend on Fe+2 as a cofactor for enzymatic activity (Ref. Reference Nagel17). While three human PHD isoforms (PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3) exist, PHD2 appears to be the most ubiquitously expressed and likely responsible for regulation of HIF-1α during normoxia (Ref. Reference Aprelikova74). Moreover, PHD2 levels are specifically induced by HIF-1α activation and may serve as a feedback loop to increase HIF-1α degradation upon re-oxygenation (Ref. Reference Nagel17). Similarly FIH-1, responsible for hydroxylation of HIF-1α Asn803, is also an Fe+2 and 2OG-dependent oxygenase.

The hydroxylation reaction mediated by PHD2 and FIH-1 requires a series of steps. Fe+2 is first coordinated at the enzyme active site, which then allows for sequential binding of 2OG followed by the substrate amino acid residues of HIF-1α. Binding of free oxygen leads to the decarboxylation of 2OG and the formation CO2, succinate and a highly reactive Fe(IV)=O intermediate that subsequently hydroxylates HIF-1α (Ref. Reference Nagel17) (Fig. 3). The understanding of this mechanism of action has led to the exploration of multiple hydroxylase inhibitors that function by either removing iron from the micro-environment through chelation or by competitive inhibition at the enzyme's active site for Fe+2, 2OG or HIF-1α. In the following section is a summary of the current data exploring the in vivo application of hypoxia mimics to augment bone revascularisation and regeneration (Table 1).

Figure 3 The mechanism of the prolyl hydroxylases. Initially Fe+2 is coordinated at the enzyme active site. This allows for sequential binding of 2OG followed by the substrate amino acid residues of HIF-1α at the active site. This process is followed by binding of oxygen to the iron centre, leading to decarboxylation of 2OG and the formation of a highly reactive Fe(IV) = O intermediate. This intermediate is responsible for hydroxylation of specific amino acids on HIF-1α. Reprinted with permission from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.

Table 1 Summary of in vivo studies examining hypoxia mimic for bone regeneration

DCP, dicalcium phosphate; DFO, desferoxamine; DO, distraction osteogensis; DMOG, dimethyl-oxalylglycine; MSC, mesencymal stem cell; POD, postoperative day; 2OG, 2-oxaloglutar.

Iron chelators as hypoxia mimics

In 1993, Wang et al. presented some of the first evidence that HIF-1α activity can be induced in vitro by treatment with the iron chelator Desferoxamine (DFO). Gleadale et al. subsequently reported that DFO as well as hydroxypyridinon chelators, were able to modulate the expression of pro-angiogenic genes in multiple cell lines in a near identical fashion to hypoxic culture conditions (Ref. Reference Gleadle75). It is now well recognised that various iron chelators can stabilise the activity of HIF-1α indirectly by inhibiting PHD2 and FIH-1 in normoxic conditions (Refs Reference Flagg76, Reference Cho77). Compared with other oxygenases, the binding of Fe+2 within the active site of 2-OG-dependent oxygenases is relatively labile and therefore removal of iron from the cellular micro-environment is a likely mechanism by which iron chelation reduces the function of these enzymes (Ref. Reference Schofield and Ratcliffe16). Since then, multiple studies have explored the use of DFO for augmenting tissue healing in numerous clinical contexts including cerebral, cardiac and limb ischaemia (Refs Reference Li78, Reference Hamrick79, Reference Chekanov80). Pre-clinical investigation of DFO therapy in bone healing was first documented by Clemens and colleagues (Ref. Reference Wan33). Mouse MSCs cultured with 50 μM of DFO under normoxia resulted in a 5-fold increase in VEGF expression determined by qPCR. Eight-week-old mice were subjected to tibial distraction osteogenesis, and injected with 20 μl of DFO (200 μM) or saline, as a control, into the distraction gap every other day from days 7–17 after surgery. DFO increased vascularity in the distraction gap, as demonstrated by markedly increased (P < 0.05) vessel numbers and vessel connectivity measured by micro-angiography. At day 31, X-ray and micro-CT analysis showed significantly increased (P < 0.05) bone volume fraction within the distraction gap in the DFO treatment group compared with controls (Ref. Reference Wan33). In a follow-up study, five doses of DFO (20 μl of 200 μM solution) were injected directly into the fracture gap of an intramedullary stabilised mouse tibia fracture from time of surgery to post-op day (POD) ten. At POD14 micro-CT angiography demonstrated increased vascularity (P < 0.05) in the treatment group with a statistically significant quantitative increase in vessel number and vessel volume. Micro-CT scanning at POD28, showed a marked and statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase in total volume and bone volume of the fracture callus in the DFO group (Ref. Reference Shen81).

Using a similar methodology, Buchman and colleagues reported a series of studies examining the effect of local DFO injections into the distraction gap of a rat mandibular DO model. They showed that 300 μl of DFO (200 μM) injected every 48 h during the active distraction period (POD 4–12) resulted in a robust increase in vascularity by POD28 compared with saline injected controls. A 40% (P < 0.05) increase in the number of vessels was determined by micro-angiography morphometric analysis (Ref. Reference Donneys82). DFO treatment also accelerated bone consolidation (Ref. Reference Donneys83). Using a 28-day healing time of saline injected mandibles as a fully consolidated control, the group compared micro-CT and biomechanical bone metric data obtained at earlier time points of 14 and 21 days from both DFO-treated and saline-treated mandibles to the fully consolidated control. At 14 days, the DFO group demonstrated significant increases in bone volume fraction and bone mineral density (P < 0.05) in comparison with nontreated controls. Furthermore, these metric values of the treatment group were close to 100% of those in the fully consolidated 28-day control group. However, comparison between the treatment and control groups at day 28 showed no statistical difference indicating that the bone growth in the control group ‘caught up’ to the accelerated experimental group at the later time point. Mechanical testing revealed that bone stiffness, yield and ultimate load at the 21-day time point in the DFO group was comparable with values obtained for 28 day controls (Ref. Reference Donneys83). Together these results show that angiogenic enhancement during DO by DFO therapy can accelerate bone regeneration and shorten consolidation periods.

To explore the use of DFO in augmenting bone regeneration and vascularity in conditions of poor tissue growth, these experiments were repeated with an irradiated murine mandibular DO model. Using the above-described DO protocol, they showed that administering human equivalents of pre-operative radiation profoundly decreased the density (P < 0.005) and number of vessels (P < 0.001) within the distraction gap after a 28-day healing period (Ref. Reference Farberg84). Interestingly, local DFO therapy effectively reversed this hypovascularity with objective restoration of all vascular metrics to levels close to nonradiated controls (Ref. Reference Farberg84). After a 40-day healing time, bone volume fraction and mineralisation, as well as biomechanical strength in DFO-treated irradiated mandibles were significantly increased as compared with irradiated saline-injected samples. The bone metric values observed in the DFO-treated group were restored to a similar level as nonradiated controls with bone volume fraction and mineral density values actually demonstrating significantly higher results (Ref. Reference Felice85). Moreover, the DFO treatment increased union rate from 11% in irradiated mandibles to 92% after DFO therapy (Ref. Reference Felice85).

Using an irradiated mandibular fracture model stabilised with an external fixator, Donneys et al. demonstrated the therapeutic potential of local DFO injections in improving bone regeneration following radiation (Refs Reference Donneys86, Reference Donneys87). Rats subjected to pre-operative radiotherapy and mandibular osteotomy demonstrated reduced vascular density (Ref. Reference Donneys87), diminished callus size (P < 0.001) and decreased quantifiable radiographic and biomechanical bone metrics (P < 0.001) (Ref. Reference Donneys86) as well as a 75% incidence rate of nonunions after a 40-day healing period (Ref. Reference Donneys87). Local DFO injection (300 μl of 200 μM) every 48 h from post-op day 4–12, significantly improved vascularity, callus size (2-fold) and bone metrics (1.5-fold BVF and 3-fold BMD 2.5–3-fold in biomechanical parameters) compared with nontreated irradiated mandible fractures (Refs Reference Donneys86, Reference Donneys87). DFO treatment again brought values within close range to nonirradiated controls. Bony union occurred in 67% of the DFO-treated group compared with 25% of radiated fractures without treatment (Ref. Reference Donneys87).

DFO has also been explored to augment the integration of bone-bridging scaffolds. Steward et al. used DFO to improve vascular invasion and bone regeneration within a biodegradable polypropylene fumarate/tricalcium phosphate scaffold in a rat femoral defect model (Ref. Reference Stewart88). Cylindrical scaffolds 5 mm long were created with four dicalcium phosphate dihydrate cement portals that were each loaded with DFO (30 μl of 400 μM) or saline. After implantation, animals underwent a healing period of 12 weeks. Vessel number assessed by micro-angiography was approximately doubled in the DFO group compared with saline controls and vessel volume trended upwards without reaching significance. Micro-CT quantified bone volume was increased but not statistically different from saline controls (Ref. Reference Stewart88). Zhang and colleges used a bovine true bone ceramic (TBC) scaffold coated with type I collagen and soaked in a 2 mM DFO solution to repair 1.5 mm rabbit radial defects (Ref. Reference Zhang89). They analysed the bony ingrowth after an 8-week implantation period into the DFO-loaded scaffolds compared with nonloaded controls. Bone volume fraction quantified by micro-CT was close to double in the DFO-loaded scaffold compared with controls (P < 0.001) (Ref. Reference Zhang89).

Results obtained from sustained local injections of DFO appear to induce greater de novo bone growth than those currently seen with attempted scaffold drug delivery systems. From a clinical standpoint, finding an adequate carrier agent for DFO that would avoid the need for multiple injections into healing tissue would be ideal. Hertzberg et al. analysed calcium sulphate pellets, collagen sponges and demineralised cortical bone matrix as potential controlled release systems for DFO using a foetal mouse metatarsal angiogenesis assay (Ref. Reference Hertzberg90). 150 μM DFO were added to each material, which were subsequently added for 24 h to incubation media of cultured mouse metatarsals. Visual grading scales of angiogenic sprouting was assessed and compared with a 50-μM DFO positive control as well as a negative control media. There was evidence of angiogenesis with all three carriers, but DFO-loaded calcium sulphate pellets significantly increased all vascularity grading systems compared with negative controls and displayed values closest to the positive control media. When exposing the CaSO4 pellets to control media for 30 min prior to adding them into the angiogenesis assay, vascularity somewhat decreased indicating that there was rapid release of DFO from the material. While these experiments do show the stability of DFO when added to different materials the sustained release from commonly used engineered scaffolds remains to be determined. In our laboratory, we have used a validated High Performance Liquid Chromatography assay to record the release profiles of DFO from dicalcium phosphate cements as well as multi-layer chitosan and alginate polymer drug carriers. In all the cases, there was rapid release of DFO from these materials with over 95% release within 24 h of incubation in physiologic buffer. Additional work needs to focus on slowing the release of DFO from biomaterials for tissue engineering strategies.

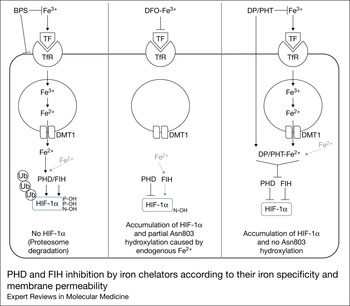

In theory any Fe+2 chelator may work in a nonselective manner to stabilise intracellular HIF-1α activity. Cho et al. showed that iron chelators displayed differential effects for PHD and FIH in cells depending on their iron specificity and membrane permeability rather than in vitro enzyme blocking potencies (Ref. Reference Cho77). Fe+3 is the predominant ionic form in the extracellular fluid, while Fe+2 ions are abundant in the cytoplasm and are required for PHD and FIH function (Ref. Reference MacKenzie, Iwasaki and Tsuji91). External Fe+3 is transported into cells via transferrin/transferrin receptor-mediated endocytosis. In the endosome, Fe+3 is reduced to Fe+2 and transported into the cytoplasm (Ref. Reference MacKenzie, Iwasaki and Tsuji91). DFO is a nonspecific iron chelator and displayed higher isolated enzyme inhibition of both FIH and PHD than the other specific Fe+2 chelators such as 1,10-phenanthroline (PHT) and dipyridyl (DP) (Ref. Reference Cho77). However, PHT and DP were able to induce expression of HIF-1α and hypoxia response gene EPO in significantly higher amounts than DFO at similar concentrations in Hep3B and HELA cell cultures. These specific Fe+2 chelators PHT and DP are able to freely cross the cellular membranes and directly access and deplete the intracellular Fe+2 without it being first bound to extracellular Fe+3. DFO is unable to cross cellular membranes by diffusion, but has been reported to enter cells via pinocytosis and can remain within cellular lysosomes and possibly reduce intracellular iron stores through nonspecific lysosomal uptake (Ref. Reference Lloyd, Cable and Rice-Evans92). Additionally, DFO exerts its action by reducing pericellular Fe+3 concentration, limiting its availability for intracellular iron uptake. PHT and DP were able to prevent Asn803 hydroxylation by FIH inhibition, whereas DFO was not. The authors suggested a potential mechanism whereby DFO is sufficient for stabilisation of HIF-1α through PHD inhibition, while pre-existing Fe+2 in the cytoplasm may be sufficient to maintain the activity of the more potent iron-binding hydroxylase FIH-1 (Fig. 4). De Boer and colleagues identified that PHT induces a high expression of hypoxia-target genes when compared with DFO (Ref. Reference Doorn93), highlighting the importance of in vivo testing of membrane permeable Fe+2 selective iron chelators, since they likely have less systemic effects by virtue of not binding extracellular iron.

Figure 4 PHD and FIH inhibition by iron chelators according to their iron specificity and membrane permeability. Fe+3 is transported into cells by transferrin (TF)/transferrin receptor (TfR)-mediated endocytosis. Within the endosome Fe+3 and converted to Fe+2 which is then transported to the cytoplasm. BPS is a strict Fe+2 chelator that cannot cross cell membranes and therefore results in a minimal chelation of cytoplasmic Fe+2, correlating with its poor inhibition of HIF hydroxylases. DFO chelates external Fe+3 decreasing the iron transported within the cell. However, DFO cannot readily cross cell membranes and therefore does not block the function of the pre-existing cytoplasmic Fe+2. This explains why DFO may be sufficient to inhibit the PHD activity, but may not be enough to fully inhibit the FIH activity. In contrast PHT, can be internalised into cells by diffusion and directly chelate the cytoplasmic Fe+2, which may induce the simultaneous deactivation of PHD and FIH activity. Reprinted with permission from Wiley Materials. Cho et al. (Reference Cho77).

So far, no clinical trials examining the local administration of iron chelators for augmenting bone repair have been attempted. DFO is an FDA-approved medication that has been used for managing iron levels in patients since the 1970s with clinical side effects only related to long-term use (Ref. Reference Cunningham94). Its demonstrated safety and history of use is probably a factor in the prevalence of studies on this molecule over other hypoxia mimics. It is difficult to extrapolate any potential bone regenerative therapeutic effects of DFO from clinical data on patients undergoing chronic chelation therapy given their significant confounding pathologies. Young patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia and increased total iron levels have a high prevalence of bone disease including significant reductions in bone mineral density, increased fractures, deformity and chronic bone pain (Refs Reference Vogiatzi95, Reference Fung96, Reference Wong97). Recent clinical data have suggested that elevated total body iron storage is an independent risk factor of accelerated bone loss even in healthy populations (Ref. Reference Kim98). The proposed mechanism of iron-induced bone loss is likely through oxidative stress that progresses as physiological iron-binding proteins are overwhelmed and labile-free iron catalyses the formation of reactive oxygen species (Ref. Reference Tsay99). DFO administration has been shown to attenuate oxidative stress and bone loss in iron-overloaded zebrafish (Ref. Reference Chen100). Any evidence of a protective effect of DFO on iron overload bone disorders in clinical data remains elusive due to the impossibility of comparing transfusion-dependent patients with and without chelation therapy. On the contrary, some studies attribute stunted paediatric bone growth and spinal deformities in young thalassemia patients directly to chronic DFO therapy (Refs Reference Olivieri101, Reference Hartkamp, Babyn and Olivieri102). Wong et al. published the first longitudinal study examining bone mineral density in thalassemia patients over 19 years (Ref. Reference Wong103). They found an accelerated reduction in BMD at the femoral neck in the last 5 years of the study as compared with previous 7 years (2.5-fold increase). This coincided with the time that DFO treatment was changed in the study institution to a newer oral chelator, Deferasirox (Ref. Reference Wong103). As both drugs function to effectively chelate iron, the authors attribute this finding to possible secondary effects of Deferasirox such as renal tubular dysfunction and renal phosphate wasting as aetiologies for lowering BMD. However, it should not be ruled out that DFO might also have actions that result in reduction to skeletal tissue damage and maintenance of bone density. While augmentation of angiogenesis and osteogenesis after the local application of DFO in pre-clinical models is convincingly due to activation of the HIF-1α pathway, other undiscovered effects of DFO on bone remodelling other than iron chelation may be contributing to its reported pre-clinical efficacy. The direct inhibition of PHD and FIH enzymes by binding of DFO to the active site has been suggested (Ref. Reference Nagel17).

Active site competitors

N-oxaloylglycine (NOG) is a 2-oxaloglutarate (2OG) analogue in which the C-3 methylene group is substituted for an NH, thus preventing its ability to act as a co-substrate for 2OG-dependent oxygenases (Ref. Reference Cunliffe104). Dimethyl-oxalylglycine (DMOG) is a derivative of NOG that can penetrate cell membranes and induces HIF-1α in cell culture assays (Refs Reference Jaakkola9, Reference Ding105). DMOG has been shown to enhance the angiogenic and osteogenic activity of adipose stem cells (ASCs) through activation of HIF-1α. Rats with critical-sized calvarial defects treated with hydrogels containing DMOG preconditioned ASCs had more bone regeneration and new vessel formation than rats treated with a nonpreconditioned cells (Ref. Reference Ding105). Shen et al. injected DMOG (20 μl of 500 μM) into the fracture site of a stabilised mouse femur fracture model every 48 h from surgery till post-op day 10 (Ref. Reference Shen81). The DMOG group trended towards increased vascular metrics by micro-CT but unlike DFO-treated femurs, they did not reach statistical significance. Micro-CT bone metrics at 4 weeks were significantly increased with DMOG treatment, while biomechanical data showed a trend in increased resistance to torsional force (Ref. Reference Shen81).

Transition metals such as cobalt can function as a hypoxia mimetic by substituting iron within the active site of PHD and FIH-1 rendering the catalytic activity dysfunctional (Ref. Reference Schofield and Ratcliffe16). Xiao and colleagues showed that low amounts of Co (<5%) incorporated into mesoporous bioactive glass scaffolds significantly enhanced VEGF protein expression as well as osteocalcin expression in bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) cultured on the scaffolds for 7 days (Ref. Reference Wu106). HIF-1α protein expression was also elevated in a dose-dependent manner. The same group constructed a dual-layered synthetic periosteum by embedding osteogenic differentiated BMSCs combined with CoCl2 pre-treated BMSCs within a type I collagen scaffold (Ref. Reference Fan, Crawford and Xiao107). Control scaffolds were made using only osteogenic differentiated BMSCS or nondifferentiated BMSC cells. Engineered periostea were tested for osteogenic and vasculogenic parameters in a mouse ectopic (subcutaneous) and orthotopic (cranial partial thickness defect) model. Two weeks after subcutaneous implantation, the CoCl2 group showed greater volume of mineralised areas by micro-CT and Von Kossa staining. Double staining with Von Kossa and von Willebrand Factor stains revealed a close relationship between mineralisation and vessel distribution. In the cranial model, implants carrying CoCl2-treated BMSCs had significantly greater volume of mineralised areas (P < 0.001), more histologically confirmed de novo bone tissue (P < 0.001), and a greater degree of vascularisation than the other implants (P < 0.001) (Ref. Reference Fan, Crawford and Xiao107).

Low concentrations of cobalt ions have been shown to directly increase osteoclast differentiation and resorptive functions (Ref. Reference Patntirapong, Habibovic and Hauschka108). Cobalt chrome alloy is widely used in orthopaedic and dental implants. After implantation, the surrounding bone and soft tissues are exposed to particulate debris and elevated metallic ion release (Refs Reference Dorr109, Reference Urban110). It has been hypothesised that observed osteolysis and aspetic loosening during the lifespan of the implant could be in part due to cobalt-induced osteoclastic activity at the tissue implant interface (Refs Reference Patntirapong, Habibovic and Hauschka108, Reference Patntirapong and Hauschka111). Patntirapong et al. demonstrated that osteoclast differentiation and function was unregulated after culture on plates coated with calcium phosphate containing traces of cobalt ions, mimicking peri-prostetic mineralised tissue incorporated with cobalt debris (Ref. Reference Patntirapong, Habibovic and Hauschka108). This group demonstrated that cobalt-induced osteoclastic activity may occur through activation of the HIF-1α pathway (Ref. Reference Patntirapong, Sharma and Hauschka112). These findings open the door to the possible use of HIF-1α blocking agents commonly explored for cancer therapeutics (Ref. Reference Kung113) to be translated for solutions aimed at reducing hypoxia or hypoxia-mimicked osteoclastic activity.

Potential adverse effects of osteogenic HIF-1α activation

The use of hypoxia mimics as therapeutics in bone repair is potentially an appealing strategy. However, disturbing the closely regulated interplay between angiogenesis and osteogenesis may lead to bone and haematological pathology, which needs to be carefully assessed and explored.

Pathological bone

Recently, Maes et al. explored the consequences of increased VEGF expression in adult bone, using a genetic mouse model in which VEGF overexpression could be temporally controlled and confined to endochondral bone (Ref. Reference Maes114). Brief VEGF overexpression induced a dramatic stimulatory effect on both angiogenesis and osteogenesis. However, the effects quickly turned pathological, as VEGF induction for only 2 weeks resulted in severe osteosclerosis and bone marrow fibrosis. Furthermore, the bone vascularity, although increased, exhibited a pathological morphology. These mice also showed evidence of increased mobilisation of hematopoietic cells to the circulation and the spleen as well as evidence of increased extramedullary haematopoiesis. Together these findings resemble the pathological changes seen in the musculeoskeletal and the haematological systems of patients suffering from myelofibrosis-associated bone disease (Ref. Reference Maes114). As such, it is crucial that more work is performed on optimising the dosing and controlled local release of hypoxia mimics to avoid these potential adverse effects.

Hypertrophic scaring

Wound healing involves a complex series of interactions between cells, chemical signals and extracellular proteins. Alterations in these processes can result in abnormal scar formation after surgery. For instance, an excessive fibrogenic response leads to hypertrophic scars and keloid formation which are often painful, itchy and prone to contracture development (Ref. Reference Hong115). Elevation of HIF-1α has been observed in keloid and scleroderma tissues compared with normal skin. Hypoxia mimics used in vitro and in vivo have been shown to increase the proliferation of fibroblasts as well as the production of extracellular matrix proteins from dermal fibroblasts (Refs Reference Zhang89, Reference Distler116). Using these drugs for bone regeneration may also affect the overlying dermal tissues in normal skin. However, given that clinical situations of compromised bone healing often coincide with significant soft tissue damage, the local use of hypoxia mimics may positively affect wound healing.

Polycythemia

One of the first HIF targets identified was EPO, an essential growth factor that stimulates the production of RBCs from bone marrow and maintains their viability (Ref. Reference Semenza117). Since then, HIF activators have been investigated as therapeutic agents for treatment of anaemia with several molecules currently in clinical trials (Ref. Reference Yan, Colandrea and Hale118). The kidney is the primary site for EPO production in adults, with the liver and brain also able to produce significant levels under stress conditions (Ref. Reference Haase119). Recently Rankin et al. showed that mice possessing osteoblasts with constitutive activation of HIF signalling, displayed enhanced erythropoiesis marked by the development of severe polycythemia by 8 weeks of age (Ref. Reference Rankin120). This elevated bone EPO expression occurred in a HIF-2α-dependent manner. While the discovery that osteoblasts have the capacity to regulate EPO expression in bone and in turn to directly modulate erythropoiesis raises exciting possibilities for the treatment of anaemia, it may be detrimental if this pathway is activated in patients with regular RBC levels. Polycythaemia places patients at risk of venous or arterial thrombosis (Ref. Reference Yan, Colandrea and Hale118), which can result in significant and even fatal cardiovascular and pulmonary complications. This is seen in patients with Chuvash polycythaemia who have a high premature mortality because of thrombotic and haemorrhagic vascular complications. These patients express congenital mutations in the VHL protein resulting in high EPO levels from excessive stabilisation of HIF-1α (Ref. Reference Yan, Colandrea and Hale118). Using hypoxia mimics for bone regeneration would inevitably turn on EPO expression in surrounding osteoblasts. While a single injection of DMOG into mouse femora has been shown to significantly elevate EPO mRNA levels 7 h later (Ref. Reference Rankin120), it remains to be seen whether the dosing of HMAs required for the clinical applications of bone regeneration would result in clinically significant polycythaemia.

Tumourigensis and progression

Cellular adaptation to a hypoxic micro-environment is essential for tumour progression. As tumour cells outgrow their vascular supply, this leads to areas of hypoxia and necrosis and subsequent upregulation of hypoxia response genes that promote survival, angiogenesis and metastatic dissemination of cells (Ref. Reference Bertout, Patel and Simon121). HIF-1α also modulates multiple pathways that contribute to radiation and multi-drug chemotherapy resistance (Ref. Reference Semenza122). In addition to the hypoxic micro-environment of solid tumours, HIF overexpression can arise secondary to genetic alterations in the pathways of HIF regulation – a classic example being mutations in the tumour suppressor gene VHL seen in clear-cell renal carcinomas and cerebellar haemangiomas (Ref. Reference Semenza122). Discussions on the role of hypoxia and HIF on cancer have been reviewed and targeting HIF for the development of antineoplastic medications is an expanding field of research over the past several decades (Refs Reference Hu, Liu and Huang123, Reference Rapisarda124, Reference Li and Ye125, Reference Wilson and Hay126).

Zhong et al. analysed HIF-1α expression in 179 tumour specimens. They found that HIF-1α was overexpressed in the majority of tumour types compared with their respective normal tissues, including in colon, breast, gastric, lung, skin, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate and renal carcinomas. With respect to primary bone tumours, Yang et al. were among the first to identify HIF-1α overexpression in over 80% of osteosarcoma samples, with the expression pattern correlating with patient prognosis (Ref. Reference Yang127). Subsequently Chen et al. showed that HIF-1α positively correlated with the size, pathologic grade, clinical stage and recurrence of osteosarcoma of the jaw (Ref. Reference Chen, Feng and Li128). It is now well established that HIF-1α has a significant role in the pathogenesis of osteosarcoma metastasis via the overexpression of CXCR4 (Ref. Reference Guo129). This HIF-1α regulated chemokine receptor has been implicated in the interactions between numerous cancer cell lines and organs susceptible to metastasis that express the matching chemokine SDF1 (Refs Reference Staller52, Reference Ishikawa130, Reference Liu131). Blocking this pathway has been proposed to have therapeutic potential to decrease metastasis in osteosarcoma patients (Ref. Reference Guan132). Further highlighting the relationship between hypoxia and osteosarcoma progression, HIF-1α activation increases resistance to widely used chemotherapeutic agents of this tumour (Ref. Reference Roncuzzi, Pancotti and Baldini133). Therefore, prolonged HIF-1α expression in the context of bone regeneration needs to be evaluated for any potential of tumorigenic transformation of native cells or of existing benign bony lesions.

Conclusion and future perspectives

HIF-mediated pathways appear to have profound effects on bone development, haemostasis and regeneration. HIF-1α activation in response to hypoxic conditions stimulates a robust angiogenic response, the recruitment of bone cell precursors and also may have direct effects on osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation and activity. Therapeutic manipulation of this pathway for improved bone regeneration is of interest to the orthopaedic and biomaterial researcher. The key aspect is the discovery of small molecules that can function as effective hypoxic mimics. The preliminary results in their application for bone regenerative strategies have been positive and exciting. More so, these molecules avoid the practical and high cost barriers that have hindered the clinical application of recombinant protein growth factors in orthopaedic technology. However, the use of hypoxia mimics is not without concern. HIF-1α activation has been observed in many cancer cell types leading to postulation that that long-term HIF activation might have pro-neoplastic actions (Refs Reference Semenza122, Reference Unwith134). EPO stimulation by HIF-1α activation is another concern as high levels of EPO are implicated in cardiovascular and thromboembolic events (Ref. Reference Smith135). These processes however would likely require a longer time course of HIF-1α stimulation than needed for augmenting angiogenesis and osteogenesis for bone healing. Current hypoxia mimics are also nonspecific in that they act to modulate function of a large class of 2OG-dependent hydroxylases possibly leading to unwanted effects. This has led to the discovery of PHD2-specific inhibitors synthesised through three-dimensional enzymatic modelling (Refs Reference Nangaku136, Reference Kontani137). These molecules have yet to be tested in the context of bone biology. Additional work should focus on the incorporation of known hypoxia mimics within biomaterials and synthetic bone grafts for controlled local release so as to avoid the need of repeated injections. While the timing of hypoxia mimic therapy appears to be best correlated with the natural angiogenic response of healing tissues, further experimentation with different therapeutic time courses during bone healing could be of interest. Additionally, hypoxia mimetic experimentation in larger animal models needs to be conducted. As it stands currently, the therapeutic manipulation of hypoxia is an exciting area and has significant promise for bone regenerative and bone tissue engineering strategies.

Acknowledgements and funding

This work was supported by funding from the Foundation for Orthopaedic Trauma (FOT) and from AOTrauma North America.

Conflicts of interest

None.