In the decade following its premiere in Weimar in 1893, Engelbert Humperdinck and Adelheid Wette's Hänsel und Gretel was one of the most widely performed operas in western Europe. This article considers the critical discourse prompted by the work's premiere in Paris in 1900, as a basis for exploring the political dynamics of the fairy tale in a late nineteenth-century context, for developing musicological interests in childhood and for elucidating the historical significance of a piece that opera scholars have largely overlooked. The discussion contributes to two areas of scholarly debate. The first is a very well-established constellation of themes: opera, nationhood, Wagnerism and ‘cultural transfer’ in French culture around 1900, together with the recent interest in opera as the subject and arena of transnational encounters.Footnote 1 For French audiences, the nationalist ideologies associated with the genre of the fairy tale, and the similarity between the Grimms’ original and a well-known French equivalent, turned Humperdinck's opera into a prime vehicle for perpetuating the Franco-German cultural competition that reached considerable heights between the Franco-Prussian and First World Wars. Just as prominent, however, was some critics’ emphasis on transnational commonalities linking French and German cultural heritage, and a sense of community beyond (as well as within) the nation, to which this shared heritage drew attention.Footnote 2 The nationalistic associations of fairy tales facilitated that emphasis.

Studies of nineteenth-century opera have neglected the second concern that this article addresses: music's significance for the cultural history of childhood.Footnote 3 Through Humperdinck and Wette's development of the Grimms’ story, Hänsel und Gretel became the principal operatic embodiment of a historically contingent perception of childhood, popular throughout nineteenth-century Europe, as an enchanted realm proximate to the divine, in need of preservation and protection. Indeed, Parisian reviewers suggested that the opera's representation of childhood explained its popularity both in France and across national borders more generally. I propose, in particular, that the attitudes towards childhood concentrated in the ‘Dream Pantomime’ in Act II accorded closely with ideals promoted in late nineteenth-century French literary and political contexts. By conforming to contemporaneous literary celebrations of Romantic childhood, Hänsel und Gretel absorbed some unsettling features. The operatic setting of the tale threatens to dispossess the two protagonists of the agency that originally defined them.

National fairy tale

When Hänsel und Gretel arrived at the Opéra-Comique in May 1900, the opera's success both in and outside Germany was widely known.Footnote 4 A large majority of the Parisian reviews were enthusiastic, many positively ecstatic. The few critics who demurred still acknowledged audiences’ rapturous responses.Footnote 5 Reviewers predicted a long run, which in reality extended to the end of the following year.Footnote 6 The venerable Wagnerian Catulle Mendès had provided a verse translation of the libretto by Adelheid Wette, Humperdinck's sister. Officially approved by Humperdinck, this libretto prioritised the preservation of the rhythmic patterns of Humperdinck's melodies over idiomatic text-setting, and a cheerful rhyming verse over a strictly literal translation of Wette's German.Footnote 7 Critics universally praised Albert Carré's mise en scène and the immersive naturalism of Lucien Jusseaume's decor (especially the forest scenery of Act II). Neither the libretto nor the production adjusted Wette's modifications of the original Grimm tale. A few critics noted one of these modifications: in the tale, Hänsel and Gretel's stepmother persuades their father that the children should be abandoned in the Forest (because the whole family cannot survive the current famine); in Wette's version, the stepmother is replaced by a biological mother who, angry at the children's lack of work, simply sends them out to the Forest to pick strawberries.Footnote 8 But Parisian reviewers did not remark on Wette's other substantial alterations (which are assessed later in this section).

Naturally, reviews of the Opéra-Comique performances reiterated some points of debate in the German reception. Like German critics, French commentators were struck by the realisation of a fairy tale through a ‘symphonic’, richly orchestrated setting, with extended contrapuntal treatments of theme. For many Parisian reviewers, this did not best suit the lightness of the story, though for most it did not detract from the opera's overall triumph.Footnote 9 Like their German counterparts, Parisian critics also remarked on the interpolation of simple, closed-form children's songs and folk tunes into that ‘symphonic’ setting, together with a popular flavour reminiscent of Strauss or Suppé (especially in Act III). As Dahlhaus put it, the opera's ‘stylistic inconsistency’ assured its spectacular success, and this was as true in Paris as elsewhere.Footnote 10 Adolphe Jullien declared the opera ‘a new resource for [those seeking] musical success’.Footnote 11 Critics did not refer in detail to recent French debates about the future direction of opera, although Arthur Pougin did claim Humperdinck's new template – with its clearly demarcated numbers, and generally clear, rhythmic writing – as exemplifying the quintessentially French model of opéra comique.Footnote 12

What obsessed German critics was the opera's status as a potential solution to the question of how to compose a post-Wagnerian opera. As Rudolf Louis put it, Humperdinck's solution – by far the most successful in Germany around 1900 – was to ‘build a small hut in the shadow of the Wagnerian art work’, replacing epic myth with cosy fairy tale and shaping a Wagnerian chromatic language into regular phrase structures.Footnote 13 Unsurprisingly, Parisian critics took up the subject. Most of the longer reviews mentioned Humperdinck's discipleship with Wagner, and many referred briefly to the Wagnerian ‘appearance’ of the style and orchestration.Footnote 14 The conservative Pierre Lalo complained that Wagnerian recitative reminiscent of adult passions in Die Meistersinger felt ‘oppressive’ when expressing the feelings of child characters.Footnote 15 Most critics, however, found no fault with Humperdinck's realisation of the ‘childlike’ through a sporadically Wagnerian language.Footnote 16 Although the Parisian press covered many positions on the Wagner question, what is most salient about French views of Humperdinck's Wagnerism is how little critics made of it.Footnote 17 Opinions would presumably have been more heated had the composer been French. By 1900, as many scholars have noted, Wagner's music was no longer the cultural and political dynamite of recent decades (though it continued to face opposition on nationalistic grounds).Footnote 18 The Opéra-Comique performances of Hänsel und Gretel did serve as a vehicle for the continuation of Franco-German cultural competition, but the central factor in that competition was something else: the identity of the tale that the opera told.

The perception of connections between fairy tales and the character of nationhood was essential to nineteenth-century European culture. The Grimms’ promotion of German nationhood rested on the notion that their tales set down oral, ‘popular’ traditions of story-telling that preserved an uncorrupted essence of national character.Footnote 19 The equivalent idea developed slightly differently in France, but by the late nineteenth century, collections of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century literary tales were associated with a comparable ‘folk’ tradition and were central to French culture.Footnote 20 In particular, Charles Perrault's Contes de ma mère l'oye (Mother Goose Tales) had become – to quote Lewis Seifert – ‘engraved … into the collective French consciousness’.Footnote 21 The Parisian reviews of Humperdinck's opera testify to the fact that Perrault's tales, at least for metropolitan intellectuals, formed a cultural ground where impressions of national community found their roots. Paul Milliet described the old woman depicted on the cover of his edition as ‘mother to us all’.Footnote 22 Most reviews of the opera compared its plot with Perrault's ‘Petit Poucet’, whose first half is strikingly similar to the Grimms’ ‘Hänsel and Gretel’. Regardless of a writer's judgement of the opera, it was always notre ‘Petit Poucet’ – a tale preserving an essence of Frenchness. The storyline of Hänsel und Gretel represented an equivalent Germanic sensibility embodied in the Grimms’ story, with the distinguishing facets of each nation's version of the tale exhibiting that nation's essential character.Footnote 23

A brief comparison between Perrault's tale, the Grimms’ story and Wette's adaptation of that story will be necessary here. Perrault's tale is considerably closer to the Grimms’ ‘Hänsel and Gretel’ than to the opera's plot. In both Grimm and Perrault, the parents lead their children into the Forest to abandon them, but the protagonists leave a trail of stones that leads them back to the house; when the parents try again, the children can only use breadcrumbs for their trail, which are eaten by birds. None of this happens in the opera. After Hänsel and Gretel are sent out to the Forest (Act I scene 2), the opera's central Act merely recounts their picking strawberries and getting lost of their own accord, before the Sandman and some angels (both Wette's additions) make them safe. Lost in their respective Forests, Perrault's children find shelter in an ogre's house, while both the Grimms’ and Wette's children discover the Witch's gingerbread cottage (Act III scene 1 of the opera). From here, the opera and the Grimms’ tale largely converge, while Perrault's takes a different turn. Petit Poucet tricks the ogre into murdering his own daughters, steals his magic ‘seven-league boots’ to escape and becomes rich through the employment that these boots secure for him. By contrast, in the Grimms’ tale and the opera, Hänsel is locked up for cooking before Gretel tricks the Witch into peering into her oven; the children triumph by shoving the Witch inside. No Parisian critics – not even Mendès – mentioned Wette's specific modifications to the Grimms’ tale beyond her reinvention of the Mother's character. Most comments about the plot referred to the opera as if it was a direct and literal realisation of the tale.Footnote 24

As one would expect, comparisons between Perrault and the Grimms provided an outstanding opportunity for touting French cultural superiority. For example, an anonymous notice in Le temps contrasted Perrault's liveliness with ‘the rather heavy, rather flat tale by the Grimm brothers’, who appeal more to ‘certain aspects of the Germanic sensibility’.Footnote 25 Here, apparent French ignorance of the extent of Wette's alterations, combined with the alterations themselves, amplified the national differences purportedly thrown into relief by the comparison. A few positive reviews made the same point less dismissively, playing more to a pride in the French character than to anti-German chauvinism. For Edouard Sarradin, the Grimms’ tale had ‘neither the variation nor the lightness of our Petit Poucet’.Footnote 26 The character of Humperdinck's setting of the fairy tale was an obvious further target for clichés about Teutonic heaviness. In Gil Blas, Gaston Salvayre observed disdainfully that ‘a less excessive sonority would better suit French ears’ for a fairy tale subject.Footnote 27 Again, some critics who adored the work also presented Humperdinck's music as a marker of national difference, in line with their assumptions about French exceptionalism. Albert Dayrolles, for example, noted that Humperdinck's German temperament did not equip him for the ‘tender finesse’ with which a French composer such as Delibes would have set the tale.Footnote 28

More interesting, however, is other reviewers’ considerable emphasis on international commonality. In his review for Le Figaro, Alfred Bruneau observed that Wette's libretto ‘evokes the memory of numerous stories from this or that country, stories among which we ourselves are happy to recognise our Petit Poucet.’Footnote 29 In Le théâtre, Jullien indulged in the contemporary fashion for folklore by noting the English as well as French and German versions of the tale; Paul Milliet also compared the characters of this ‘Petit Poucet allemand’ with those from Russian culture.Footnote 30 In his review for the mass circulation Le journal, Mendès himself ventured two explanations for the ‘moving’ commonalities of ‘so many tales from so many countries’.Footnote 31 He considered the first explanation to be the conventional one: the similarities were records of the symbols through which primitive man had understood the natural world. He was more taken by the second: the shared plots stemmed from mothers telling stories at a single location in the deep past. Mendès set out versions of an important nineteenth-century idea that derived from fairy tales’ association with folk traditions (and which is familiar to musicologists in the context of folk song): while manifesting different identities at a local/national level, fairy stories were ultimately underpinned by a few primitive forms indicating some universal historical collectivity.Footnote 32

In a situation where two ‘national’ versions of the same tale demanded comparison, the nationalist ideologies that structured nineteenth-century understandings of fairy tales could support essentially opposing perceptions of the relation between the national communities represented in those tales. Depending on one's aesthetic and political agendas, one could focus on the divergences between those versions, and therefore on questions of cultural superiority, or on the similarities, and therefore on the phenomenon of international commonality. Assessing Humperdinck's opera a few years earlier in Le gaulois (a paper favoured by the haute bourgeoisie), Stanislas Rzewuski considered the fairy tale's potential to transcend the national as a vehicle for a specific creed: an elitist Wagnerian universalism.Footnote 33 For Rzewuski, the fairy story on which the opera was based had the potential to speak, like the subjects of Wagner's operas, to ‘universal humanity’, because it stemmed from the folk's ‘collective genius’; but the tale was essentially too vulgar.Footnote 34 This was unrepresentative of most reviewers’ remarks on the commonalities of French and German heritage, both because Rzewuski questioned the cultural value of fairy tales and because he pushed a clearly defined universalist agenda.Footnote 35 The emphasis by other reviewers such as Milliet and Jullien on the tales’ shared features appeared as an extension, not a contradiction, of a commonplace sense of national identity. This emphasis did not suppress perceptions of national difference (indeed, it relied upon those perceptions), but presented them as natural variants upon an implicit transnational communality.

The same issues of interpretation applied directly to Humperdinck's arrangements and imitations of folk song. Critics discussed these much less than the fairy tale plot, though most referred in passing to the ‘motifs populaires allemands’ woven into the score, and almost all to the opera's folk-style aspect.Footnote 36 Gretel's song at the beginning of the opera harmonises a folk melody, as does her equivalent song at the opening of Act II. Other moments, such as the dance-song in Act I scene 1, retain the ‘folk-like’ character of these passages.Footnote 37 In late nineteenth-century France (as elsewhere), folk song provided the focus of a nationalist project, on the assumption that a nation's folk songs could, like its tales, express its ‘physiognomy’.Footnote 38 As with equivalent concerns about the fairy tale, Hänsel und Gretel prompted French critics to consider questions about folk song and identity in an international rather than intra-national context.Footnote 39 However, unlike the literary material on which the opera was based, Humperdinck's settings of folk music did not prompt comparisons between the respective national physiognomies embodied in French and German folk material.Footnote 40 While folk music from peripheral European countries was often musically packaged as signifying forms of ‘Otherness’, Humperdinck's anodyne arrangements (or imitations) of his German material did no such thing.Footnote 41

Whether because of this or despite it, Mendès claimed that the songs of Humperdinck's country closely resembled those of France, extending his statements about the transnational dimensions of fairy tales into the realm of folk song. He gave no evidence, and neither did Corneau in observing a striking resemblance between the opera's folk melodies and some French ones he knew.Footnote 42 But in his guide to the opera published the year before, Étienne Destranges provided some details of his own, identifying (with musical examples) the melody of the Father's song at the opening of Act I scene 3 with that of a Breton folk song.Footnote 43 In the 1880s, folklorists’ investigation into the links between Arthurian legend and Breton folk tales had allowed French Wagnerians to claim the Tristan subject as ultimately French, heading off anti-German chauvinism.Footnote 44 Like these critics, Destranges embraced Breton material as representative of, rather than separate from, a broader French identity. But unlike them, he did not draw his comparison into a contest of national ownership. For him, this ‘curious similarity’ simply proved ‘the relatedness of folk motifs from different countries’.Footnote 45 Destranges anticipated those assessments of fairy tales which, rather than opposing French and German cultural identities, emphasised the tales’ indication of what Matthew Gelbart terms the ‘national-as-universal’.Footnote 46

The relative prominence of this idea in the Parisian reception of Hänsel und Gretel is both noteworthy and unremarkable. That is to say, it indicates an unremarkable strain of national sentiment that is noteworthy given the weight of scholarly emphasis on fin-de-siècle French anxiety about (and opposition to) the dominance of German musical culture, and what Fulcher calls the ‘mounting French political and cultural rivalry with Germany by the turn of the century’.Footnote 47 The overall character of audiences’ response is testament partly to the opportune moment in which the opera arrived. By 1900, the general sentiment of revanche, rampant in the wake of the Franco-Prussian war, had greatly diminished (though far from disappeared).Footnote 48 In the musical world, the necessity of German influence and exchange had been accepted at least through the uneasy consensus that Wagner – the pre-eminent representative of German cultural dominance – must be Gallicised and surpassed, rather than simply opposed.Footnote 49 In some cases, specific political motivations were presumably at work. For example, Fulcher links Bruneau's views as a Leftist Dreyfusard with the ‘universal and humanist values’ that emerged around 1905 in Socialist and Syndicalist discourse.Footnote 50 His celebration of the similarities between national tales could reveal the development of those values, if not their explicit promotion – the right-wing Gauthier-Villars, writing in the nationalist, anti-Dreyfusard L’écho de Paris, took much the same line. Overall, what the ideologies of the fairy tale genre revealed and facilitated in critics’ responses was a direct acknowledgement of deep-lying commonalities between French and German heritage, surprisingly free of competitive anxiety, coming from various points on the aesthetic and political spectrum.

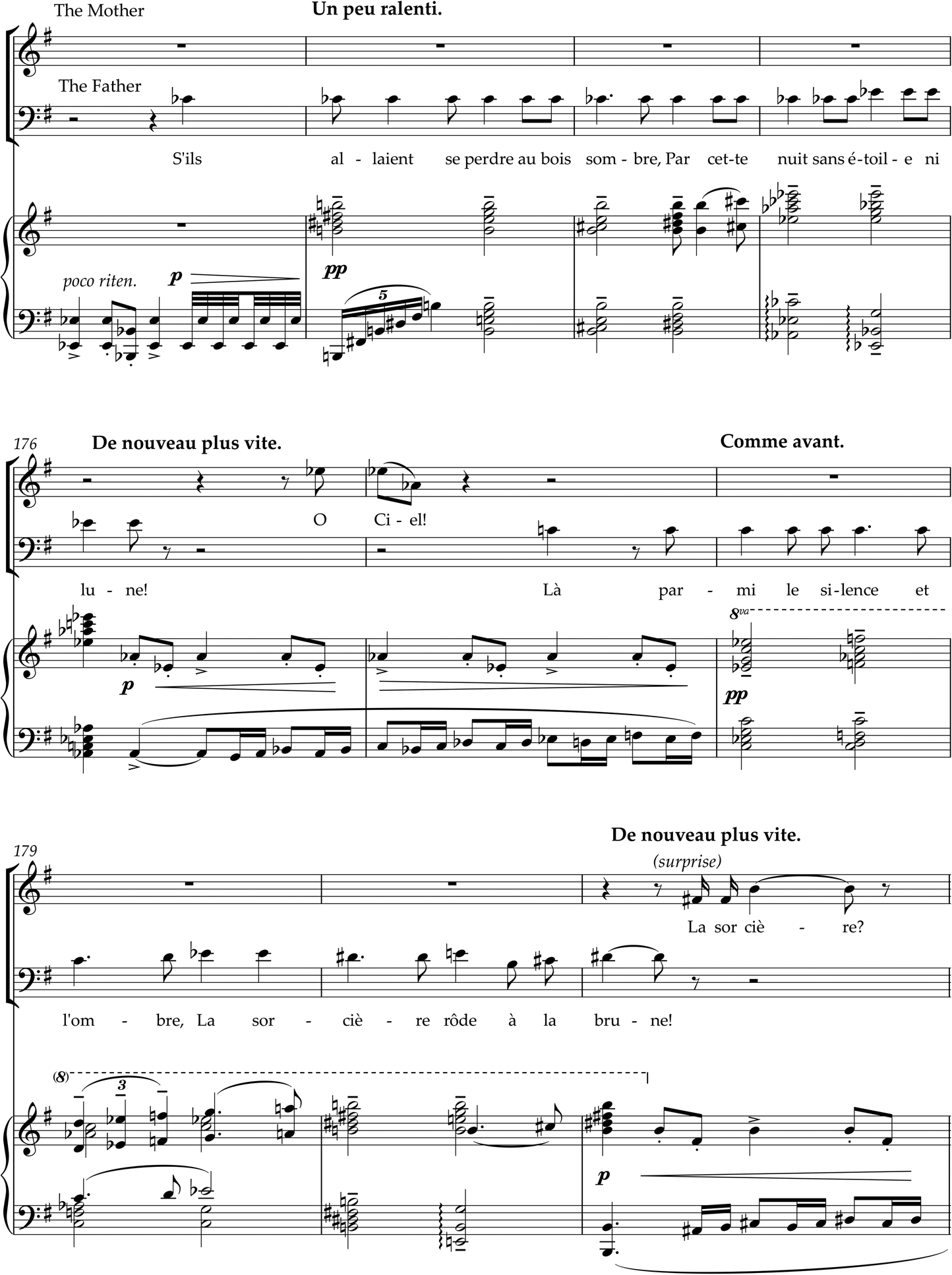

The staging encouraged rather than inhibited this response. The protagonists’ costumes apparently signified the generic local colour of a poor rustic milieu, rather than anything specifically German (see Figure 1 for a press photograph).Footnote 51 The costumes and the singers’ performances also helped to perpetuate a widespread feature of late nineteenth-century thought that the opera clearly embodied: the conflation of ‘the folk’ (understood as a universal collective of the distant past, whose traces lived on in the practices of rural communities) with the idea of childhood. Through the children's singing that opened the first two acts, the qualities that distinguish the opera's ‘folk’ elements – a cheerful naïvety, realised through closed song numbers – are also musical realisations of the ‘childlike’. The dance-song of Act I scene 1 (Example 1) epitomises this realisation.Footnote 52 In late nineteenth-century France, as Jann Pasler observes, folk melodies were associated with a stylistic quality that emphasised their ‘naïve grace’.Footnote 53 Humperdinck's setting of his folk numbers accords exactly with this aesthetic. Critics’ assessments of the opera's appeal extended its infantilisation of folk material, describing the closed song numbers of the first two acts interchangeably as ‘folk’ and as children's music.Footnote 54 Destranges suggested that audiences must listen to the opera ‘with the simple soul of children’ in order to understand it fully, not just because it was a fairy tale but also because of its ‘folk feeling’.Footnote 55

Figure 1. Mathilde de Craponne and Marthe Rioton as Hänsel and Gretel, Le théâtre (July 1900), 11. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Example 1. Gretel teaches Hänsel a dance. Hänsel und Gretel, Act I scene 1, bb. 215–24.

Such statements appealed to the widely held view that the development of an individual recapitulates the development of a culture or species. Both children and the communities purportedly harbouring traces of folk practices constituted versions of an idealised internal ‘primitive’, which had a connection with nature that was lost to the fully civilised adult.Footnote 56 This belief gave rise to a conflation of cultural and personal nostalgia that was well established in the French literary imagination.Footnote 57 The influential historian Jules Michelet had also invoked the link in his book of 1846, Le peuple, in which he had asserted that both the child and the peasant possess ‘a vision of existence that has a freshness and energy inaccessible to the cultured’.Footnote 58 It is this un-learned vivacity that characterises the child characters’ folk-style numbers in Humperdinck's opera. In the first Opéra-Comique performances, the two leads clearly emphasised this characterisation, ‘laughing, leaping, singing and dancing like mad’.Footnote 59 Indeed, the richness of the opera's representation of childhood remains the most important and the most neglected aspect of its cultural significance.

Lost children

Like the opera's contemporaneous German critics, today's scholars account for Hänsel und Gretel's enormous early success in German contexts in terms of its cosy domestication of Wagnerian musical language.Footnote 60 German scholars have also emphasised the popularity of Humperdinck's ‘folk’ aesthetic.Footnote 61 In the Parisian reception, an additional factor comes to the fore. Several critics offered their own explanations for the opera's popularity across Europe. For Dukas, the winning melodic simplicity of the child characters’ music ‘explains why Hänsel und Gretel pleased the public of every country where there are still children or people who have been children’.Footnote 62 Bret formulated the same explanation less cryptically: it was the sections devoted to characterising the childlike – the start of Act I and Act II, in particular – that would be as popular in France as in Germany.Footnote 63 For Jullien, the opera's childlike character as a whole explained its success with ‘all its publics’.Footnote 64 Milliet gave two reasons for its international popularity: first, Humperdinck's music generally (including his incorporation of ‘folk rhythms’); second, the ‘children's tale’ that it set.Footnote 65 Opinions differed on how the opera embodied a ‘childlike’ spirit: for Dukas and Bret, that quality arose from the folk-like song numbers; for Milliet and Jullien, from its compositional origins and the simplicity of the fairy tale subject. But for each, the principal explanation of the opera's international success was its treatment of the subject of childhood. The ‘childlike’ features identified by these critics are clearly inextricable from those to which scholars usually attribute the opera's popularity: the children's story, for example, was an ingenious vehicle for justifying a break from the sheer length and symbolic import of Wagnerian models while maintaining aspects of a Wagnerian musical language.Footnote 66 But the importance of the subject of childhood for the opera's success was far deeper than this. Hänsel und Gretel, I would suggest, was the most culturally significant operatic embodiment of a perception of childhood that artists and intellectuals obsessively promoted across mid- to late nineteenth-century western Europe. In the French context, certainly, the opera's elevation of that perception accorded closely with prevailing attitudes towards childhood in contemporaneous political and literary discourse.

For the majority of enthusiastic reviewers, the opera's appeal lay principally in its evocation of a world of childhood. Kunc assessed at length how the text and the action manifested a brilliant exercise in ‘child psychology’.Footnote 67 The same term lay at the heart of Gauthier-Villars's praise, which singled out the dance song's acuity as an expression of childhood joy.Footnote 68 Other critics besides Dukas (including some who were generally negative) were especially taken by the sections where the child characters sing: according to de Bréville, the first half of Act I and Act II in general were the source of the opera's warm reception.Footnote 69 In the longer reviews, enthusiastic descriptions of the work's origins – Humperdinck's setting of songs from the Grimms’ tale, subsequently expanded into a small Singspiel for the entertainment of Wette's children – often framed the opera as an act of parental affection writ large on the theatrical stage, highly suited for all ages.Footnote 70 Another closely related theme was the opera's capacity to precipitate an idealised return to childhood reverie. Bruneau described Humperdinck's music in general as ‘the poem of childhood, of the childhood of beautiful laughter, of beautiful dreams’.Footnote 71 Milliet declared that fairy stories ‘rejuvenate’ the public, and ‘bring them back to their first dreams’.Footnote 72 All such references were steeped in a Romantic perception of childhood, indebted to Rousseau, as a deeply idealised, homogeneous spiritual domain, one set apart from adulthood's utilitarian concerns, to which adults aspired to return. Destranges celebrated the ‘children who, everywhere, have come in crowds to applaud [the opera] with their little hands’.Footnote 73 Dukas's remark about the ‘public of every country’ adopted a similarly homogenising image of children appearing in joyous crowds from all places.

In a study published in 1889, Hippolyte Durand celebrated the fact that ‘almost all contemporary [French] writers unite to form a superb choir chanting, in honour of childhood, a song of happiness and love’.Footnote 74 In the most general terms, Humperdinck's opera manifests this idealising attitude: just such a ‘song of happiness’ appears in Act III scene 4, when the gingerbread children celebrate their liberation, exhorting themselves to dance and sing.Footnote 75 The following discussion focuses on Act II scene 3 – a sort of set-piece ballet usually described as the ‘Dream Pantomime’ – since it is here that, as Hans-Josef Irmen has briefly suggested, the tale's protagonists most clearly become nineteenth-century child characters.Footnote 76 In the Opéra-Comique performances, this scene was extremely popular with audiences. Almost every review praised Carré's realisation of the fourteen angels’ majestic descent down a series of luminous, coloured steps, to protect the children as they sleep.Footnote 77 Milliet and Bruneau's euphoric references to childhood reverie suggest that this scene in particular shaped their overall response to the opera. Entirely Wette's invention, the Dream Pantomime scene staged the stock image of an angel watching over a (sleeping) child, a motif that saturated late nineteenth-century French culture (as well as other national cultures), appearing everywhere from adult poetry to children's song books.Footnote 78 The image had various connotations: it summarised a conventional ideal of childhood as a state of supreme moral innocence, proximate to the divine; it also cast the protector of childhood as a figure with celestial attributes. In staging this image, the Dream Pantomime exploited the nineteenth century's new sense of a responsibility to shelter childhood from the world's ills.

Writing of western Europe generally, Linda Pollock observes that, by 1900, the ‘ideal of childhood as a state to be protected and prolonged had become entrenched for middle-class children and extended, as a right, for the first time to the poorer child’.Footnote 79 Durand's 1889 study congratulated contemporary French society on its enlightened attitudes towards children, whose protection was considered the responsibility of all. In 1900, the universal acceptance of this ideal by French society could not be taken for granted. Although legislators had targeted child labour since the 1820s, influential polemics about the need for state intervention continued to appear in the Third Republic.Footnote 80 Only from the early 1880s, with the introduction of free, universal and compulsory primary education, could French children in general (as opposed to middle- and upper-class children) be considered schoolboys and schoolgirls, rather than workers, in the wider imagination. If the notion of a child without a childhood was not new to the nineteenth century, then its elevation to the status of grand literary pathos certainly was. Fictional representations of vulnerable children gave emotional shape to the political movements that aimed to remove them from the streets and the factory.Footnote 81 Another motivation for such movements in France was the state's embrace of childhood as political capital, which underpinned the introduction of compulsory schooling. Republican thinkers presented their conception of children as citizens-in-the-making in terms of the ideal that Pollock describes. To justify the state's unprecedented intervention in the raising of children, pedagogues and politicians promoted the metaphor of the state as a parent, intervening to protect and strengthen its children.Footnote 82 Appeals to the perception of childhood as a ‘state to be protected and prolonged’ invoked, in short, a central tenet of contemporaneous literary culture and the prevailing political environment. French critics’ delight in the opera's representation of childhood can only be fully understood in the context of that perception.

Nineteenth-century writers often combined the image of the protecting angel with another archetype: the lost or abandoned child. Humperdinck and Wette expertly adapted their protagonists into versions of these lost children.Footnote 83 Through her choice of fairy tale and her adjustments to it, Wette took advantage of the appetite for stories involving this archetype: all that happens in Act II is that the children become lost and are saved from a condition of vulnerability. Humperdinck's setting further emphasises the theme of ‘lostness’. Lucie Kayas has noted the dramatic significance of Hänsel's bare, unaccompanied announcement in Act II that he has lost the way.Footnote 84 At least as striking is the Father's exclamation, in Act I scene 3, that his children might be lost in the Forest. A sudden elevation of register marks his realisation, suspending the motion of the scene (Example 2).Footnote 85 Humperdinck makes striking use of the ‘voice-leading efficiency’ characteristic of late nineteenth-century chromatic harmony: the vocal line is locked to a single pitch, as if transfixed with emotion, while around it the shifting triadic relations evoke a frisson of terror. This music reappears un-transposed in Act III scene 1 (though without some of the enharmonic shifts), accompanying Gretel's first recollection of the angels’ descent. The dramatic contexts of this material associate it with the gravity of abandoning children in a dangerous world, the urgency of rescuing them, and the spiritual import of that urgency.

Example 2. The Father's fear about his children astray in the Forest. Hänsel und Gretel, Act I scene 3, bb. 172–81.

In accounts of the Paris premiere, several reviewers responded directly to this import, singling out the sudden intensity of the passage in Act I.Footnote 86 French audiences would certainly have been primed to appreciate Wette and Humperdinck's elevation of the theme of the lost child. One of the most important figures in later nineteenth-century French fiction was, in Lloyd's words, that of ‘the orphan, the foundling, the child separated from its parents, or the child rejected by family or peers’.Footnote 87 The character type had many different realisations. The narrative embodied in Act II of Hänsel und Gretel, in which a divine force secures the safety of the lost children, was very prominent in French fiction, and adopted especially by Victor Hugo. As Marina Bethlenfalvay puts it, in most of Hugo's accounts of lost, abandoned or abused children, ‘a higher, often supernatural force’ saves or avenges them; often that force is an angel.Footnote 88 The drama of lost children that Wette built out of the original tale therefore replayed the tension and resolution of a scenario popular with French readers. Humperdinck's Dream Pantomime music emphatically celebrates the moment of resolution. Although for some Parisian critics this passage exemplified Humperdinck's overblown setting, for others it was a triumph that matched Carré's staging.Footnote 89 In Hugo's narratives, as Bethlenfalvay observes, the interventions on behalf of lost children affirm ‘the sovereignty of innocent things’.Footnote 90 This phrase aptly describes the intended power of the chorale theme that emerges at the climax of the Dream Pantomime, with what Jullien called ‘seraphic serenity’ (Example 3, b. 43).Footnote 91

Example 3. The climax of the Dream Pantomime. Hänsel und Gretel, Act II scene 3, bb. 35–47.

The appeal of this scene also derived from the fact that literary obsessions with lost children were often really about adulthood. Lloyd proposes that these characters were metaphors for the alienated nineteenth-century urban subject seeking an identity in the shifting conditions of modernity.Footnote 92 The enshrinement of childhood as a protected realm also secured it, for adults, as a protective realm of the imagination. This was certainly what childhood became in those critical responses that located the opera's power in its ability to return the spectator to a state of childhood ‘dream’. Bruneau's description of Humperdinck's music generally – the poem of ‘the childhood of beautiful dreams’ – not only evoked the sacrosanct ideal of childhood as a state to be protected but also suggested a vaguer nostalgia, directed beyond the bounds of individual memory, which ideals of childhood both occasioned and fulfilled.

Keeping children childlike

In recent decades, literary scholars and art historians have increasingly emphasised the more unsettling features of nineteenth-century representations of childhood as a beatific state, vulnerable but spiritually exalted. Does Hänsel und Gretel, as a prime operatic example of such representations, exhibit those features? Nineteenth-century evaluations of childhood innocence extended the assessment of childhood as ‘a race apart’, to some extent inaccessible to the adult mind. That assessment in turn demanded that accounts of childhood experience become more circumscribed, and child characters increasingly drained of any real psychological presence.Footnote 93 As a consequence, child figures often served simply as a blank screen for the projection of adult desires, whether nostalgic, emotional or sexual. James R. Kincaid puts this particularly strongly in his accounts of how the Romantic child – ‘this emptiness called a child’ – seems ‘oddly dispossessed … without much substance’.Footnote 94 Humperdinck and Wette admitted traces of this ‘dispossession’ of the Romantic child through updating their protagonists into nineteenth-century character types.

Jack Zipes observes that, in Humperdinck and Wette's hands, the Grimms’ tale becomes ‘a kind of Christian parable, celebrating God the Father's majesty and benevolence’.Footnote 95 From their first version onwards, the Grimms supplied various Christian references of their own (in the final version, for example, Hänsel reassures his sister that God will protect them, after they overhear their parents’ murderous plans). Wette's additions of religious references, symbols and characters attain a different level of significance. Zipes implies that the operatic setting is no longer quite a fairy tale; and indeed, the opera significantly undermines the crux of the tale – the moment at which the children pass a test of maturation. This is the moment when Gretel turns the Witch into the victim of her own plan.Footnote 96 Musically and dramatically, this moment is curiously under-powered. Humperdinck's setting of the children's triumph over the Witch (Act III scene 3) hardly registers the structural importance of this moment, despite a brief climax. Several responses to the first Opéra-Comique performances also emphasised a general lack of musical tension in Act III. Salvayre, for example, noted Humperdinck's abandonment of a more Wagnerian mode after Act II, in favour of lighter textures and waltz rhythms.Footnote 97 The tensions ramped up by the high-flown drama of lostness in Act II dissipate by Act III, despite the fact that the children's predicament only deepens at the beginning of the final Act.

According to the opera's own logic, this lack of tension makes sense: the structural climax occurs at the end of the previous scene. As Amanda Glauert puts it, the Dream Pantomime music ‘more than balance[s] the … Witch's Ride and leave[s] one in no doubt that good will triumph in the coming battle between evil and innocence’.Footnote 98 The tale's resolution, then, is predetermined by the angels’ intervention, which guarantees not only the children's immediate safety in the forest but also their safety in the coming confrontation with the Witch. Certainly, the return of the Evening Prayer theme in the Dream Pantomime, in the global tonic of F major, feels like a more dramatic resolution than any other point in the opera. That ‘good will triumph’ over evil is rarely in doubt in many fairy tales, but how exactly this triumph occurs is significant. The angels’ intervention threatens to displace, rather than complement, the moment of the children's maturation. At the opera's conclusion, the Father does not attribute the Witch's defeat to the children's wits, but to divine law.Footnote 99 Another possible moment of structural resolution is the cadence prepared at the beginning of Act III scene 5, producing a jubilant F major transformation of the Witch's theme from the opening of Act II (as the Witch herself is dragged out of the oven). Both the resolution and dominant preparation of this cadence are, however, much less climactic than the Dream Pantomime's equivalent. This final resolution is also soon sealed by the concluding reiteration of the Evening Prayer theme, setting the opera's final refrain, which itself refers to God's protection in one's darkest hours. Verbally and musically, then, the opera's conclusion re-invokes the angels’ intervention, as if that intervention has governed the tale's resolution, taking control of the narrative at the end of Act II.

The idea, perhaps, is that Hänsel and Gretel are vehicles of divine law. Inheriting late nineteenth-century interests in the affinities between fairy stories and Christian narratives, mid-twentieth-century literary critics famously proposed that the moments of triumph precipitating fairy tales’ happy endings carry a suggestion of the numinous.Footnote 100 Yet that suggestion belongs only to the quality of the narrative; it is not revealed as an occurrence within the tale's fictive world. In the opera, by contrast, the force that underwrites the fairy tale's ‘happily ever after’ appears onstage, personified, in the Dream Pantomime.Footnote 101 The scene's Hugo-esque sanctification of the actions by which children are made safe depends on the fact that the angels constitute an alternative source of agency to the children. In overshadowing the children's moment of death-defying ingenuity, the divine intervention risks divesting them of their own agency.

In much nineteenth-century literature, as Linda M. Austin observes, narratives of growing up would often ‘set the boundaries of childhood by individual experiences’.Footnote 102 This was partly because childhood was less firmly defined in terms of an age range: childhood gave way to the next stage of life after a particular event marked the end of a former self. In one sense, the crux of the fairy tale narrative is this experience – the one that the opera weakens. Wette weakened it in other ways, too. Commentators have missed an essential dimension of her adjustments to the parent characters: by excising their attempts to abandon the children, Wette also deprives the two protagonists of opportunities to demonstrate the ingenuity that defines them in the tale. A comparable alteration comes at the end, when Hänsel and Gretel do not make their own way back through the Forest (as they do in the tale) but are found by their parents. The reunion occurs during the dominant preparation to the final cadence, after which the Father leads the concluding moral lessons. The moment of tonal closure is therefore also the moment when the children are reinserted into the protective, disciplinary structures of the family – the structures that went much of the way to defining them as childlike, objects of parental devotion.

Hänsel und Gretel, then, betrays a deep disposition to keep children childlike. Humperdinck and Wette's adaptation of the Grimms’ tale bears witness to a tension between, on the one hand, promoting the protection of childhood and, on the other, representing children's self-determination. In the opera (as in so many late nineteenth-century representations of childhood), the former overrides the latter, giving shape to the highly restrictive aspect of the image of the divinely protected child. Wette's alterations accorded perfectly with the ‘complex of bourgeois Christian values’ promoted in late nineteenth-century French children's literature.Footnote 103 In assuring audiences that threats to the enchanted domain of childhood are always defeated, those alterations also deprive Hänsel and Gretel of agency and ingenuity, rendering them (in Kincaid's phrase) ‘oddly dispossessed’.

Childhood and (trans)nationalism

How do these attitudes relate to my earlier topic – critics’ interest in transnational commonalities between French and German cultural identities? Our existing picture of the relation between childhood and nationhood in nineteenth-century French culture would suggest that there is little connection. That picture emphasises the exploitation of Romantic ideologies of childhood for the promotion of nationalisms that were often exclusive or combative. The image of the lost child lent itself well to nationalist discourse, as symbolising a subject denied the affirmation of national belonging. This usage was well established in Republican discourse before pedagogues’ sustained promotion of the metaphor of the state as parent.Footnote 104 The compulsory universal schooling instituted by Republicans in the 1880s not only was founded on the notion of pupils as ‘children of France’ (national-citizens-in-the-making) but also introduced curricula often promoting antagonistic nationalist sentiments – the new state method of raising Frenchmen sought to avoid a repeat of the 1870 capitulation in the event of future German aggression.Footnote 105 Musicological contributions to the cultural history of childhood in the nineteenth century have also, naturally, emphasised childhood's connections with the forms of nationalism most familiar to music scholars.Footnote 106

Parisian reviews of Hänsel und Gretel, however, point to rather different associations between nationhood and childhood. It was the ideologies of the fairy tale that allowed critics most clearly to express a sense of rootedness beyond as well as within the nation; but notions of childhood (and motherhood) were clearly inextricable from those ideologies. Dukas's assessment of the opera's success – that its childlike qualities ‘pleased the public of every country where there are still children or people who have been children’ – projected the connotations of Romantic perceptions of childhood (as a homogeneous, indivisible state elevated above adult concerns) onto the issue of nationhood, implying that the significance of national divisions recedes when melody sings ‘like childhood itself sings’.Footnote 107 Dukas's conception of childhood, like that embodied in the opera, was one whose idealisation suppressed an awareness of children's individual agencies and experiences. Around 1910, French writers were increasingly exploring very different worlds of childhood, structured by savagely enforced, intricate hierarchies.Footnote 108 These could not have presented childhood as a joyous, uniform collective, the image embraced both in the opera's conclusion and by Parisian reviewers.Footnote 109 Remarks such as Dukas's, in other words, raise the possibility not only that the opera celebrated a historically contingent perception of childhood prized by both French and German audiences but also that, on some level, that perception afforded a means of cultivating non-oppositional or non-exclusionary national sentiment.

To speculate along these lines is not, of course, to advocate the introverted utopianism that often characterised late nineteenth-century attitudes towards childhood; in any case, one cannot read too much into a few observations. However, literary and historical scholarship frequently traces the transmission of nineteenth-century perceptions of childhood across Europe without considering the role played by those perceptions in creating the environment that encouraged such transmission.Footnote 110 In the continually developing field of the history of transnational thought, both within and beyond opera studies, ideologies of childhood merit further investigation.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Flora Willson, Daniel Grimley and Jonathan Cross for their generous comments on early versions of these ideas and to the reviewers of this journal for their feedback.