Recent decades have witnessed profound changes in archaeological knowledge of the ancestral Maya past, with particularly notable empirical advancements in our understanding of the initial adoption of ceramics, sedentism, and agricultural lifeways (Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2010; Lohse Reference Lohse2010, Reference Lohse and Walker2022; Traxler and Sharer Reference Traxler and Sharer2016; Walker Reference Walker2022). New evidence indicates that the earliest documented sedentary communities were integrated into an early pan-Mesoamerican interaction sphere by the beginning of the first millennium b.c. (Cheetham Reference Cheetham and Powis2005; Cheetham et al. Reference Cheetham, Forsyth, Clark, Laporte, Arroyo, Escobedo and Mejía2002; Clark and Cheetham Reference Clark, Cheetham and Parkinson2002; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig and Lesure2011, Reference Rosenswig and Hodos2016). By the sixth century b.c., this tradition would be replaced by a distinctively Maya material culture horizon that would spread across most of the Maya Lowlands (Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2010; Traxler and Sharer Reference Traxler and Sharer2016). This emergent autochthonous tradition, reflected in ceramics, art, and architecture, was characterized by homogeneity, conservatism, and a long temporal span.

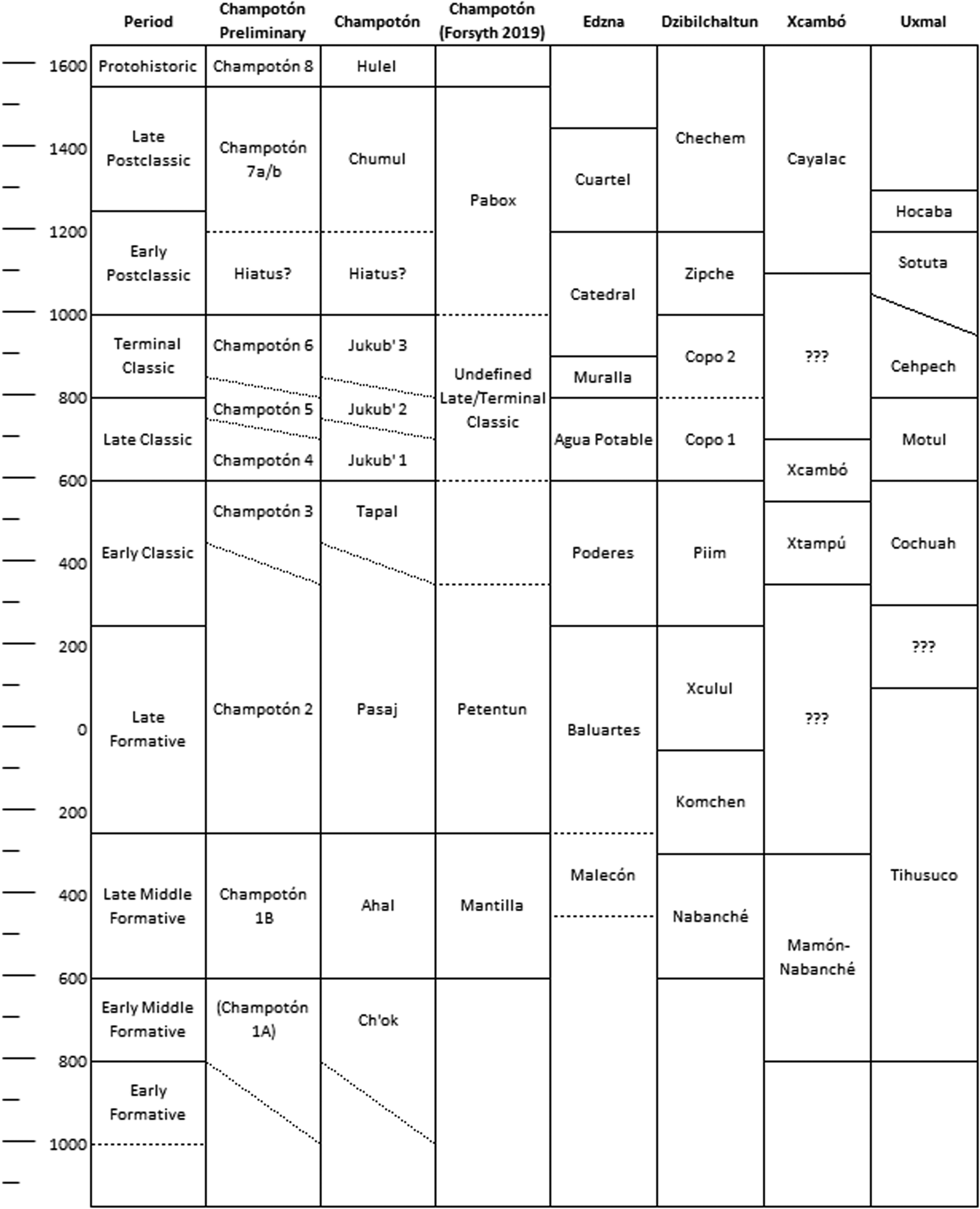

New data have served to underscore some fundamental shortcomings in the chronological frameworks we use to understand the ancestral Maya past. The variant of the Mesoamerican chronology used in the Maya area was first developed as an evolutionary typology untethered to absolute dates and applicable to the entire western hemisphere (Table 1; Phillips and Willey Reference Phillips and Willey1953; Willey and Phillips Reference Willey and Phillips1955, Reference Willey and Phillips1958). The nature of this chronological framework gradually metamorphosed from a developmental sequence into a static timeline with fixed intervals. Over the course of seven decades as the standard temporal nomenclature in Maya studies, there have been only minor revisions to this chronology to accommodate new evidence. This article examines the nature and development of this conceptual framework, and its applicability in a specific case study from coastal Campeche.

Table 1. Developmental stages outlined by Willey and Phillips (Phillips and Willey Reference Phillips and Willey1953; Willey and Phillips Reference Willey and Phillips1955, Reference Willey and Phillips1958). This framework was originally created as a developmental sequence untethered to absolute dates. Typological: Absolute criteria pertain to attributes that are empirically evident, such as the appearance of specific technologies or diagnostic artifacts. Configurational: Relative criteria include characteristics based on political/social organization, or more subjective criteria that involve aesthetic judgements or diachronic contrasts (e.g., religious/secular, ritualistic/militaristic).

Regional settlement survey in the Champotón River drainage in central Campeche documented three millennia of human occupation, crosscut by episodes of major change in political affiliation, economic organization, and human-environmental interactions. The earliest sedentary communities in the Champotón region produced and consumed pottery that was a participant within an early pan-Mesoamerican stylistic horizon. The Ch'ok complex has been documented in small frequencies in multiple sites in the Champotón River drainage, with a notable pattern of intraregional variability. The transition to a radically different ceramic tradition unfolded during the sixth to seventh centuries b.c.: the traditional boundary between the early and late facets of the Middle Preclassic period. The ensuing Ahal complex represents a major change in patterns of ceramic influence, with a shift from pan-Mesoamerican stylistic influences toward full participation in the earliest autochthonous material culture tradition that is uniquely Maya in character. The Mamom and ensuing Chicanel spheres were part of a waxy-ware tradition with remarkable persistence over at least eight centuries, appearing in consistent form across most of the Maya Lowlands. This era was marked by conservatism and gradual growth.

This timeline is an awkward fit within the current iteration of the Mesoamerican chronological framework. This study highlights some shortcomings in the version of the Mesoamerican chronology currently implemented for archaeological research in the Maya Lowlands, particularly incongruences between the original purposes of this framework and its usage in contemporary research. Instead of forcing new data into a largely outdated chronological framework, the goal of this article is to refocus attention on disjunctions in the archaeological record that reflect historical inflection points. This study highlights a broader need for major revisions in the temporal heuristics we employ to understand the Maya past.

TEMPORAL THEORY AND FRAMEWORKS FOR UNDERSTANDING THE ANCESTRAL MAYA PAST

What do we mean when we say “Maya?” At the time of Spanish contact, the area we now refer to as the Maya Lowlands was an expansive zone linked by a common set of languages, material culture, ideology, and lifeways. Archaeological and epigraphic evidence indicates that these characteristics extend back at least into the Classic period (Houston and Martin Reference Houston and Martin2016; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Robertson and Stuart2000). However, it is important to remember that the concept of “Maya civilization” is an etic anthropological construct. Ethnohistoric and epigraphic evidence indicate more intersectional conceptualizations of identity, with political, factional, and class distinctions holding greater social relevance (Hendon Reference Hendon, Grove and Joyce1999, Reference Hendon and O'Donovan2002; Pugh Reference Pugh, Rice and Rice2009; Rice and Rice Reference Rice and Rice2009; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2013). Our understanding of these dynamics is even more fragmentary for eras pre-dating the textual record.

The concept of “Mayaness” emerged from colonial social dynamics and became a meaningful ethnonym following the crystallization of anthropology as an academic discipline during the twentieth century. The concept derives from the theoretical perspective of culture history, a trait-based approach to anthropology embodied within Boasian historical particularism (Trigger Reference Trigger2006:211–311). This anthropological paradigm was characterized by a taxonomic approach to the study of human cultural diversity, with delineation of cultural groups based on shared attributes. The incorporation of this approach into archaeological research focused on the temporal and spatial delimitation of units based on shared attributes of material culture. Childe (Reference Childe1950:2) defined the “archaeological culture” by co-occurrence of traits, or “arbitrary peculiarities of implements, weapons, ornaments, houses, burial rites, and ritual objects … assumed to be the concrete expressions of the common social traditions that bind together a people.” The concept of the “Maya” as a cultural tradition derives from this approach, combining both social (shared languages, worldviews, and ways of life) and material culture attributes (pottery, tools, art, and architecture). In some regions the past was envisioned as a sequence of distinct material culture traditions (e.g., a broader Woodland tradition divided into distinct archaeological cultures: Adena, Hopewell, Fort Ancient, etc.). In contrast, the ancestral Maya past is viewed as a single developmental sequence spanning three millennia. The rationale for selecting between temporal sequences of cultures or a unified historical tradition was often arbitrary, yet has critical repercussions in the ways we envision the past.

In the wake of calls for archaeology to address topics of greater social relevance (Kluckhohn Reference Kluckhohn, Hay, Linton, Lothrop, Shapiro and Vaillant1940; Taylor Reference Taylor1948), Willey and Phillips undertook the ambitious task of defining the central conceptual frameworks for archaeological practice as well as a model of cultural change (Phillips and Willey Reference Phillips and Willey1953; Willey and Phillips Reference Willey and Phillips1955, Reference Willey and Phillips1958). Drawing on neo-evolutionary and ecological perspectives, explicit emphasis was placed on the delimitation not of traits, but of processes of cultural development. The Willey/Phillips chronology consisted of six stages: Early Lithic, Archaic, Preformative, Formative, Classic, and Postclassic (Table 1). This developmental scheme became the foundation of Mesoamerican chronologies, with later stages connected to ceramic sequences following the adoption of the type-variety approach (Smith and Gifford Reference Smith and Gifford1966).

Decoupling developmental stages from interval time was a central element of the Willey/Phillips scheme. As their evolutionary framework was intended to be applicable for the entire western hemisphere, it was independent of any fixed intervals of time. This approach was historically important because it established cultural evolution as the dominant paradigm in American archaeology, setting the stage for further theoretical and methodological shifts in the processual era (Leventhal and Erdman Cornavaca Reference Leventhal, Cornavaca, Sabloff and Fash2007; Trigger Reference Trigger2006). In the ensuing generations, it was adopted as the standard temporal heuristic in Mesoamerican studies.

Over time the temporal boundaries of stages within the Mesoamerican chronology became fixed and took on a fundamentally different character: what Willey and Phillips defined as periods. Now coupled to specific spans of time, these temporal units continued to be implemented despite increasing incongruence between their original defining attributes and empirical evidence. For instance, there is broad consensus that many distinctive “Classic Maya” attributes originated no later than the Late Preclassic period. As a developmental chronology, such new empirical findings should necessitate modification of the temporal placement of the stage. In current usage, these terms are little more than shared vocabulary used to refer to fixed temporal intervals.

The shift from a chronological framework comprised of developmental stages to a fundamentally different set of heuristics consisting of periods with fixed temporal boundaries was gradual, with no corresponding changes in nomenclature. Yet the corresponding terminology retained the original developmental baggage, entailing not just evolutionary but often moral overtones (Joyce Reference Joyce, Richards and Buren2000). We tend to view the Preclassic period through a teleological lens, comprising developments along a pathway to the (often fetishized) Classic fluorescence (Webster Reference Webster and Fagan2006). Likewise, instead of “secular, urban, mercantile, and militaristic,” the Postclassic period was portrayed as unenlightened and morally deficient (i.e., “decadent”). Despite widespread rejection of neo-evolutionary models, our basic framework for thinking about time is still based on a developmental typology that is both embedded in neo-evolutionary paradigms and increasingly inconsistent with empirical evidence.

Concurrent with the gradual metamorphosis of the Mesoamerican chronology, the late twentieth century witnessed vigorous debates and theory building outside Maya studies focused on new approaches to archaeological chronologies (Bailey Reference Bailey1983; Binford Reference Binford1981; Knapp Reference Knapp1992; Plog Reference Plog1974; Schiffer Reference Schiffer1985). These concerns link archaeology with other historical sciences that deal with temporal scales beyond a human lifetime. Chronological frameworks based on hierarchies of temporal units—best embodied in the Annales approach in history (Braudel Reference Braudel and Matthews1980)—hold obvious archaeological relevance (Knapp Reference Knapp1992). Braudel identified a hierarchy of phenomena that exist at different temporal scales: event, conjuncture, and longue durée. Events concern episodes or occurrences which form the basic subject matter of mainstream history: people, battles, and treaties. Conjunctures consist of processes that operate at an intermediate temporal scale, ranging from shorter-term cycles (wars, market cycles) to long-term phenomena (demographic trends or geopolitical and economic reorganizations). Finally, phenomena within the longue durée include long-term structural relationships that condition more dynamic processes at shorter temporal scales.

Research in historical ecology by Butzer (Reference Butzer1982) identified analogous rhythms of systemic change with variable temporalities: adaptive adjustments, modifications, and transformations. Adaptive adjustments consist of short-term economic and social dynamics that exist within the frame of a human lifetime, corresponding to events and short-term conjunctures in the parlance of Braudel. Adaptive modifications consist of major change in human adaptive strategies, such as agricultural intensification, demographic movements, and political cycling. These correspond with Braudel's longer-term conjunctures and longue durée. Finally, adaptive transformations exist on a temporal scale beyond Braudel's framework, describing fundamental human adaptive modes, such as the development of agriculture or industrialization. This perspective mirrors new approaches in socio-ecological systems theory, particularly theories of adaptive change (Gunderson and Holling Reference Gunderson and Holling2002). A common feature of these new frameworks is a hierarchy of nested temporal scales.

The main contribution of archaeology to the broader social and historical sciences is time depth. Thus, chronology theory holds particular relevance in the development of archaeological frameworks that can integrate time frames far beyond a lifetime (what Braudel referred to as “unconscious history”), with intermediate and short-term dynamics that relate more directly to historical eras and lived human experiences. Nested temporal frameworks can best accommodate a wide range of phenomena: events and short-term conjunctures that are the realm of history and text-aided archaeology; dynamics that operate on a scale comparable to ceramic phases (100–200 years); and long-term adaptative processes and socio-ecological regimes with temporalities measurable in centuries or millennia. Linking archaeological models of change with conceptual frameworks from complex systems approaches, transitions between periods are often defined by nonlinear change and threshold behavior, with “tipping points” between major eras of history marked by the emergence of new sets of political, economic, social or human-environmental interactions (Meyer and Crumley Reference Meyer, Crumley, Moore and Armada2012). Indeed, accommodation of phenomena with variable temporalities is a necessity for any effective chronology. The underlying goal of any chronological framework is to help us make sense of the past by delimiting periods defined by key historical developments: the pivot points or transitions that define eras.

THE INITIAL CERAMIC COMPLEXES IN THE MAYA LOWLANDS

Recent studies provide a nuanced view of the initial appearance of distinctively Formative cultural traits in the Maya Lowlands (Brown and Bey Reference Brown and Bey2018; Clark et al. Reference Clark, Hansen, Suárez, Manzanilla and Luján2001; Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2010; Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2010; Traxler and Sharer Reference Traxler and Sharer2016; Walker Reference Walker2022). The period between 1100 and 1000 b.c. is emerging as a temporal threshold for the adoption of pottery, with studies from across the Maya Lowlands documenting ceramic complexes that pre-date the widespread Mamom ceramic sphere (Figure 1; Walker Reference Walker2022). Pre-Mamom complexes were initially documented at Altar de Sacrificios (Adams Reference Adams1971), Ceibal (Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975), Barton Ramie (Gifford Reference Gifford1976), the Peten Lakes (Rice Reference Rice1976), Komchen (Andrews V Reference Andrews1988), Cuello (Hammond Reference Hammond1991), and Tikal (Culbert Reference Culbert1993, Reference Culbert and Sabloff2003). The initial pottery from Champotón pertained to one of several highly regionalized ceramic spheres—including the Cunil, Eb, Swasey, Ek, and Xe spheres—linked by participation in a broader pan-Mesoamerican stylistic, iconographic, and ideological system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Early Middle Formative ceramic spheres in the Maya area. Cartography by the author using NASA SRTM base map.

The Xe sphere of the Pasión River is the best-documented pre-Mamom ceramic tradition in the Maya area. The earliest ceramic complexes from Altar de Sacrificios (Adams Reference Adams1971) and Ceibal (Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975) are characterized by matte-slipped red, white, and black serving vessels with dichrome and post-slipped incised decorative motifs. Andrews V (Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990) noted similarities between Xe and contemporaneous Isthmian ceramics in slip characteristics (dull matte color, powdery and easily eroded surfaces, and red-on-white decoration), pastes (generally coarse-grained, with sand or ash temper), and vessel form repertoire.

Sabloff (Reference Sabloff1975:48–49) noted temporal changes in Xe sphere ceramics, with a shift from early dull, dark, and matte red slips toward lighter and glossier redwares and decreasing frequency of white-slipped ceramics. Recent research at Ceibal has led to significant refinement of the original ceramic typology, including identification of three facets of the Real (Xe) complex from precisely dated contexts (Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Aoyama, Castillo and Yonenobu2013, Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015). The Real 1 phase (1000–850 b.c.) is characterized by high frequencies of diagnostic matte white-slipped ceramics and a simplified form repertoire (see summary in Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017). The ensuing Real 2 phase (850–800 b.c.) is defined by decreasing frequencies of white-slipped ceramics and new forms, including wide, everted bowls. Real 3 (800–700 b.c.) is marked by red-and black-slipped pottery with glossier slips, pre-slip incised designs, grooved rims, and chamfering. Xe pottery is the closest analog to contemporary pottery at Champotón, with these patterns of temporal variability corresponding to intra-regional patterns noted at the Ch'ok complex (discussed further below).

The Central and Eastern Maya Lowlands—the zone encompassing the northern and central Peten in Guatemala and adjacent areas of the upper Belize River Valley—is home to multiple sites with documented Middle Formative ceramic complexes. The Cunil tradition was initially documented at the site of Cahal Pech (Awe Reference Awe1992; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Brown, Awe, Morris, Jones, Awe, Thompson and Helmke2009), part of a regional sphere in western Belize that includes Blackman Eddy, Xunantunich, Pacbitun, and Barton Ramie (Cheetham Reference Cheetham and Powis2005; Cheetham et al. Reference Cheetham, Forsyth, Clark, Laporte, Arroyo, Escobedo and Mejía2002; Clark and Cheetham Reference Clark, Cheetham and Parkinson2002; Garber and Awe Reference Garber and Awe2009; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Brown and Hartman2002, Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004; Healy et al. Reference Healy, Cheetham, Powis, Awe and Garber2004; Sullivan and Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe and Aimers2013; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Brown, Awe, Morris, Jones, Awe, Thompson and Helmke2009). Cunil shares common typological and form repertoires with the Eb tradition documented at Tikal, Uaxactun, Holmul, Cival, Nakbe, and the Peten Lakes region (Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada Reference Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada2016; Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Cheetham Reference Cheetham and Powis2005; Clark and Cheetham Reference Clark, Cheetham and Parkinson2002; Culbert Reference Culbert1979, Reference Culbert1993; Hansen Reference Hansen and Powis2005; Moriarti Reference Moriarti, Foias and Emery2012:201–205; Neivens de Estrada Reference Neivens de Estrada and Braswell2014; Rice Reference Rice1976). Ceramic assemblages from Holmul, Guatemala, exhibit a greater degree of ware and type diversity, including a mix of modes common in Cunil and Eb (Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada Reference Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada2016; Neivens de Estrada Reference Neivens de Estrada and Braswell2014). There is a lack of consensus on the relationship between the Eb and Cunil traditions (Ball and Taschek Reference Ball and Taschek2003; Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Neivens de Estrada Reference Neivens de Estrada and Braswell2014). Given the clear overlaps in type descriptions from primary red, white/cream, and black slipped groups in both spheres, this could reflect either a unified Cunil/Eb sphere or separate spheres with clinal differences between eastern and western zones (see Figure 1).

A very different ceramic tradition has been documented in northern Belize. The Swasey sphere includes the Swasey/Bladen complexes first documented at Cuello and identified at Colha, Nohmul, Blue Creek, Pulltrouser Swamp, and other sites in northern Belize (Andrews V and Hammond Reference Andrews and Hammond1990; Fry Reference Fry, McAnany and Isaac1989; Hammond Reference Hammond1991; Kosakowski Reference Kosakowski1987; Kosakowski and Pring Reference Kosakowski and Pring1998; Levi Reference Levi1993; Lohse Reference Lohse2010; Pring Reference Pring1977). Swasey redwares lack the characteristic dull matte slips of other contemporary pottery traditions, with glossy surface textures similar to—and likely predecessors of—late Middle Formative Mamom ceramics. In contrast to the sharp break between early and late Middle Formative pottery documented in other regions, the continuity in northern Belize has led several to argue that this is the first clearly identifiable “Maya” material culture tradition (Andrews V Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990; Kosakowski and Pring Reference Kosakowski and Pring1998:64).

The earliest pottery from the Northern Lowlands and Puuc Hills forms another regional sphere. The Ek complex was initially documented at Komchen (Andrews V Reference Andrews1988, Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990), and later at multiple sites in northwest Yucatan and the Bolonchen region in the northeast Puuc Hills (Andrews V and Bey III Reference Andrews, Bey and Walker2022; Andrews V et al. Reference Andrews, Bey, Gunn, Brown and Bey2018; Cruz Reference Cruz Alvarado2010). These materials differ from southern counterparts in a narrower repertoire of slip colors and combinations. Decorative modes are characterized by an extensive focus on elaborate post-slip incised decoration. As in Xe, Eb, and Cunil, there is a sharp break in ceramic traditions between the early and late Middle Formative period.

While the earliest ceramic traditions in the Maya area are regionalized and typologically distinctive (Walker Reference Walker2022), they reflect participation in a symbolic and iconographic system that was pan-Mesoamerican in scale. These broad stylistic similarities transcend localized production spheres and industries, including:

• dull matte slips, typically red, white, orange, and black, in rough order of commonality;

• red-on-white or red-on-cream dichromes;

• unslipped (sometimes burnished) serving vessels;

• elaborate post-slip incised geometric designs;

• ash, sand, and micaceous inclusions;

• incised iconography with pan-Mesoamerican distribution, including cleft, avian, serpent, “flame eyebrow,” lightning, cross, shark tooth, and music bracket motifs (see expanded discussion in Cheetham Reference Cheetham and Powis2005).

Based on these common characteristics, Cheetham and colleagues (Cheetham Reference Cheetham and Powis2005; Cheetham et al. Reference Cheetham, Forsyth, Clark, Laporte, Arroyo, Escobedo and Mejía2002; Clark and Cheetham Reference Clark, Cheetham and Parkinson2002) have argued for a “Cunil Horizon” linking the Xe, Eb, and Cunil spheres. Yet these modes do not appear uniformly in different participant complexes, but instead constitute unique local amalgamations of broadly shared attributes.

Although the dating of the early Middle Formative ceramic complexes has been the topic of some debate (Andrews V and Hammond Reference Andrews and Hammond1990; Hammond Reference Hammond1977, Reference Hammond1991; Kosakowski Reference Kosakowski1987; Kosakowski and Pring Reference Kosakowski and Pring1998), synthesis of the available evidence seem to be converging on a common chronology. Recent research at the site of Aguada Fénix in the western periphery of the Maya area revealed evidence for ceramic use by 1200 b.c. and the development of major public architecture by 1000 b.c. (Inomata Reference Inomata2019). Initial reports indicate that the earliest pottery from Aguada Fénix demonstrates strong similarities with slightly later Xe ceramics from Ceibal. Similar pottery appears in other parts of the Maya Lowlands around 1000 b.c. (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015; Lohse Reference Lohse2010, Reference Lohse and Walker2022; Walker Reference Walker2022). The end of these traditions is more variable, with either a continuous developmental trajectory into Mamom sphere ceramics or (more commonly) abrupt replacement sometime around 700–600 b.c.

The high degree of variability between ceramic complexes reflects regionalized spheres linked by shared stylistic and iconographic modes that were widespread during the early part of the Middle Formative. This pattern of regionalized ceramic spheres seems most consistent with a relatively balkanized political and economic landscape of loosely connected communities. The seven spheres discussed above (Figure 1) likely reflect relatively small-scale networks of producers with distinctive practices, norms, and technologies. However, these spheres share important similarities—particularly decorative modes—that reflect participation in a broader pan-Mesoamerican system of interaction. The lack of standardization both at the regional scale and across the Maya area is a notable contrast to the more inclusive and homogeneous Mamom and Chicanel spheres that emerge in ensuing periods.

REGIONAL RESEARCH IN THE CHAMPOTÓN RIVER DRAINAGE

The Champotón Regional Settlement Survey (CRSS) documented political, economic, social, and environmental dynamics within long-term cycles of adaptive change in the Champotón River drainage (Ek Reference Ek and Cobos2012a, Reference Ek and Braswell2012b, Reference Ek2015, Reference Ek2016, Reference Ek and Walker2022). The initial phase of the project (2003–2011) was regional in scope, incorporating reconnaissance, intensive survey, and test excavations. In total, 13 pre-Hispanic centers were documented, with intensive surface survey and testing in seven sites (Figure 2). Test excavations generated samples of domestic refuse from residential contexts to reconstruct patterns of political and economic change. The CRSS research complemented earlier investigations undertaken by the Universidad Autónoma de Campeche (UAC) in monumental constructions within the modern city of Champotón (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Morales, Dominguez, Ruiz, Heredia, Gunn, Florey, Barredo, Hernandez and Bolles2002, Reference Folan, Folan, Morales, Heredia, Blos, Bolles, Ruiz and Gunn2003, Reference Folan, López, Trujeque, Heredia, Folan, Bolles and Gunn2004, Reference Folan, López, Heredia, Trujeque, Folan, Bolles, Gunn, Carrasco, Pacheco and Castillo2007, Reference Folan, López, Heredia, Trujeque, Folan, Forsyth, Tiesler, Gómez, Cen, Bishop, Bowles, Braswell, Ek, Gunn, Götz, Vallanueva, Blanso, Gunam, Carrasco, Noble and Palma2013; Forsyth Reference Forsyth2004, Reference Forsyth2008, Reference Forsyth and Palma2012, Reference Forsyth2019; Gómez Cobá et al. Reference Cobá, José, López, Blos and Folan2003; Götz Reference Götz2006, Reference Götz2008; Gunn and Folan Reference Gunn, Folan, McIntosh, Tainter and McIntosh2000; Hurtado Cen et al. Reference Hurtado Cen, Bastida, Blos and Folan2005, Reference Hurtado Cen, Bastida, Tiesler, Folan, Tiesler and Cucina2007).

Figure 2. Champotón Regional Settlement Survey project study area, with Phase 1 Reconnaissance and Phase 2/3 Full Coverage Survey and Testing zones. Map by the author.

Ceramic samples from 13 sites—a total of 261 surface collections and 99 test excavations—were analyzed and classified within the Type-Variety system (Tables 2 and 3). The basic framework for this analysis was based on the ceramic chronology developed by Donald Forsyth in his analysis of ceramic materials excavated by the UAC's Proyecto Champotón (Figure 3; Forsyth Reference Forsyth2004, Reference Forsyth and Palma2012, Reference Forsyth2019). The CRSS ceramic assemblage was analyzed and classified by Jerald Ek, Wilberth Cruz Alvarado, Josalyn Ferguson, Matthew Sargis, and Sean O'Brien, with assistance from Donald Forsyth (Ek Reference Ek and Cobos2012a, Reference Ek and Braswell2012b, Reference Ek2015, Reference Ek2016; Ek and Cruz Alvarado Reference Ek and Alvarado2010). While regional occupations were previously viewed as limited to the Postclassic and Historic periods (Eaton and Ball Reference Eaton and Ball1978; Ruz Lhullier Reference Ruz Lhullier1969), the CRSS documented a much longer history of human settlement in the Champotón River drainage. A serendipitous result of the project was documentation of extensive Preclassic occupations in all the areas studied by the project, comprising three distinct ceramic complexes: Ch'ok, Ahal, and Pasaj.

Figure 3. Ceramic complex and regional chronology developed for the Champotón River drainage, as well as contemporary related complexes. Image by the author.

Table 2. Sample sizes for ceramic assemblages from the Champotón Regional Settlement Survey. This assemblage was generated from surface collections (SC) and excavation units (EU) from Phase II and Phase III sites in the Champotón River drainage between 2003 and 2009. Stratigraphic (Strat.) contexts consist of documented strata from excavation units.

Table 3. Percentages of each ceramic complex within the total assemblages from each of the seven Phase III research loci. Total percentage for each loci adds up to approximately 100%. Ch'ok complex (Champotón 1A); Ahal complex (Champotón 1B); Mixed/Transitional Pasaj/Ahal; Pasaj complex(Champotón 2); Tapal (Champotón 3); Jukub' (Champotón 4, 5, and 6); Chumul (Champotón 7); and Hulel (Champotón 8).

THE EARLIEST CERAMICS IN THE CHAMPOTÓN RIVER DRAINAGE

The earliest evidence of sedentism and pottery production in the Champotón region is associated with the Ch'ok complex (Table 4). Ch'ok shares broad modal similarities with contemporary ceramic traditions in the Maya Lowlands, including dull matte-slipped wares, incised post-fire geometric motifs, red/white dichromes, and some basic form modes. This complex was one of several regionalized and distinctive small-scale production and distribution spheres that appeared during the early facet of the Middle Preclassic period (1000–600 b.c.; see Figure 1).

Table 4. Major constituent ceramic groups and types of the Ch'ok (Champotón 1A) complex. The types share modal similarities with other pre-Mamom ceramic complexes identified in the Maya Lowlands. All of the type names listed above were established by the author.

Although Ch'ok materials were encountered in multiple sites in the Champotón River drainage, the complex remains poorly represented in comparison with later time periods. Ch'ok ceramics were encountered in small quantities within the CRSS study area. In total, 476 sherds recovered from sealed contexts were classified within four ceramic groups, with a notable pattern of intra-regional variability in paste and slip characteristics (for more detailed typological descriptions, see Ek Reference Ek2015:410–534, Reference Ek and Walker2022). This diversity could reflect a lack of standardization among regional communities or temporal variability that remains poorly understood due to small sample sizes. Given this uncertainty, we adopted a conservative approach in the creation of groups and types (Table 4). It would be unsurprising if continuing research results in typological subdivisions and refinement.

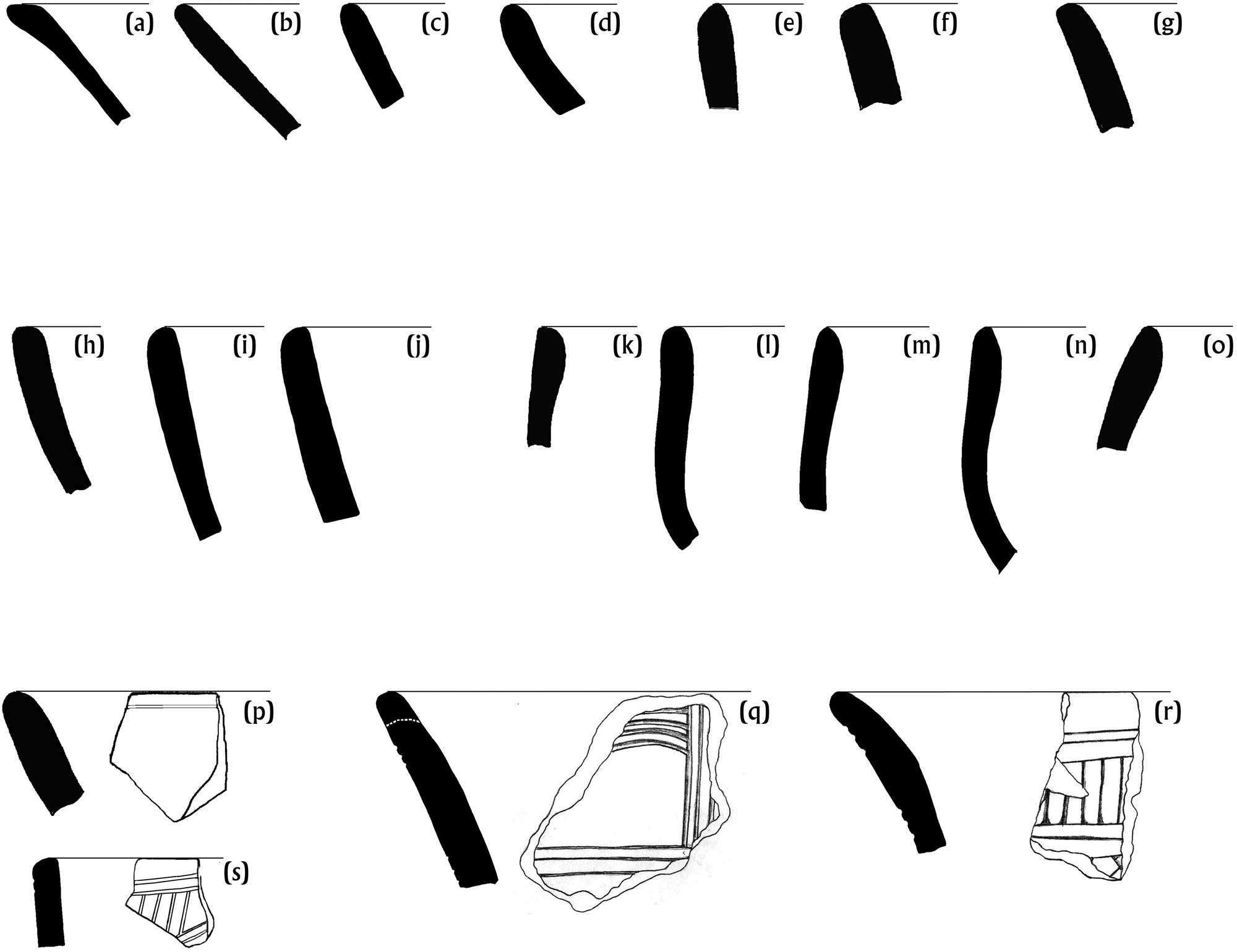

There are two dominant paste groups in the Ch'ok complex: a more frequent light gray ware, often with notable dark gray nuclei; and a less common compact, sandy, orange-textured ware. White, cream, orange, and red groups are present, consisting of very thin slips with a matte to powdery texture that is easily eroded. Redwares of the Yax ceramic group often have a thin slip that adheres poorly to vessel walls, with colors ranging from dark red to orange red (Figure 4). Orange-slipped ceramics of the Canasayab group are difficult to classify due to a very high degree of paste variability. Some ceramics classified in this group have compact pastes with complete oxidization, indicating more controlled firing. Other orange-slipped materials have coarse pastes with incomplete oxidization similar to local red- and white-slipped groups in the Ch'ok complex. This could indicate the existence of two separate production systems within this group.

Figure 4. Ch'ok Ceramics 1—all rims (a–s) exemplify the Yax ceramic group. Drawings by the author.

White-slipped vessels of the Chanpet group are among the most distinctive components of the Ch'ok complex (Figure 5). Chanpet slips also have a matte surface texture, with a range of coloration between white and cream. Dichromes are a consistent and distinctive attribute of the complex. Red-on-white and red-on-cream pottery consists of a secondary red slip applied to the outside of the bowls, which extends a few centimeters below the edge of vessel interiors. Red dichromes differ from red monochromes, with the former having a much brighter and more lustrous surface finish. Less common black-on-white and black-on-cream dichromes include drip designs and wavy line motifs that to my knowledge have no analogs in contemporaneous complexes in other parts of the Maya area.

Figure 5. Ch'ok Ceramics 2—Chanpet, Cansayab, and Xkeulil ceramic groups. (a–e) Xkeulil Unslipped; (f–h) Canasayab Orange; (i–m, o–q) Chanpet White; (n) Misc. Mottled. Drawings and photographs by the author.

Pastes and surface treatment of unslipped wares are difficult to separate from the Achiotes Unslipped and Sapote Striated types of the subsequent Ahal complex. The main difference between the Xkeulil Unslipped group in Ch'ok and later complexes is in vessel forms and the prevalence of striations. Xkeulil unslipped vessel forms include plates and bowls with direct to slightly incurred sides and thick, rounded lips. Jars are much less common than in the Ahal complex, in which unslipped bowls and dishes are relatively rare. The high frequencies of bowl and dish forms parallel unslipped burnished groups noted in contemporaneous complexes at other sites in the Maya area. Incised motifs are common on the exterior walls of bowls, ranging from rim bands to more complex geometric motifs. However, incised decorations are far less common or elaborate in comparison with other pre-Mamom traditions in the Maya Lowlands.

Beyond these primary groups, Ch'ok deposits consistently included examples of ceramics with rather unique characteristics that did not fit easily into established categories. A few examples of black-slipped sherds were encountered, with characteristics quite different from later waxy-ware black materials. Examples of ceramics with distinctive mottled brown and green slips were also found in pure Ch'ok deposits. These materials had more compact pastes, thinner vessel walls, and thick lustrous slips. The slip and paste characteristics of these materials were notably different from contemporary ceramics that occurred in greater frequencies, indicating alternative production systems. These minority types—potentially trade wares—were encountered in insufficient quantities to justify creation of new groups. However, given the relatively limited sample sizes, the pottery in use during this period presumably includes greater group diversity than is reflected in Table 4.

Ch'ok evinces notable intra-regional variability. The high variability in paste composition could reflect a lack of consistency in production methods within the region. The two main paste groups exist in the same contexts, perhaps reflecting overlapping production areas. Slip color is also highly variable, particularly in the white, cream and buff tones that could represent a range of coloration instead of distinct groups. Pending additional research in sites with substantial Ch'ok occupations, as well as direct comparisons with contemporary materials, the existing evidence indicates a high degree of intra-regional heterogeneity. Notable intersite differences in the region include a higher frequency of white-slipped and red-on-white dichromes in sites near the mouth of the Champotón River (Table 5). Inland sites—particularly Ulumal and San Dimas—have greater quantities of red- to orange-slipped materials. Further, redwares from coastal sites have a dull, matte texture compared with inland contexts. In contrast, redwares from Ulumal and San Dimas included serving vessels with glossier slips and more compact and completely fired pastes.

Table 5. Frequencies of ceramic groups and types in the Ch'ok (Champotón 1A) complex. All groups and types established by the author (Ek Reference Ek2015).

Although we currently lack sufficient evidence to determine if these differences reflect geographic or temporal variability, coastal/inland differences mirror distinctions between temporal facets in the Real complex documented in recent research at Ceibal (Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015). Well-dated faceting of contemporary materials from the latter site documented increased prevalence of white-slipped and red-on-white dichromes in earlier deposits. This pattern could reflect an earlier chronological placement for Ch'ok contexts along the coast, adjacent to the mouth of the Champotón River and coastal estuaries, with later expansion into inland areas along the Champotón River floodplain. This model will be evaluated in future research.

Interregional Comparisons

Ch'ok shares modal similarities with other early complexes, most notably with the Xe/Real sphere of the Upper Usumacinta, as well as contemporary pottery from northern Belize, the Belize Valley, and northern Yucatan. Paste composition and the prevalence of white-slipped and white base dichromes mirror descriptions of Xe sphere materials from Ceibal and Altar de Sacrificios (Adams Reference Adams1971; Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975). Yax Red shares form and slip similarities with Abelino Red from the Pasión/Usumacinta (Adams Reference Adams1971; Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975), particularly early (Real 1) forms of Abelino Red from Ceibal (Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Aoyama, Castillo and Yonenobu2013, Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015). This could indicate a relatively early chronological placement for these materials, particularly examples found at sites near the mouth of the Champotón River. The matte white slips, form repertoire, and sandy paste textures of the Chanpet group have shared characteristics with the Huetche ceramic group at Ceibal (Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975:53–56). Finally, the small samples of black-slipped materials from Champotón have similar paste and slip characteristics as Crisanto Black (Adams Reference Adams1971:24; Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975:57). These correspondences indicate that the potters who produced Ch'ok ceramics had closest interactions with communities in western parts of the Maya Lowlands, including the upper and middle Usumacinta drainages.

The Ch'ok complex shares similarities with other contemporary traditions across the Maya Lowlands. White-slipped ceramics are also common at Holmul (Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada Reference Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada2016:44), Cahal Pech (Awe Reference Awe1992:231; Sullivan and Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe and Aimers2013), and Tikal (Culbert Reference Culbert1979). The Yax group has modal similarities in Uck Red from the Belize Valley (Awe Reference Awe1992; Sullivan and Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe and Aimers2013; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Brown, Awe, Morris, Jones, Awe, Thompson and Helmke2009), Consejo Red from Northern Belize (Kosakowski Reference Kosakowski1987; Kosakowski and Pring Reference Kosakowski and Pring1998; Pring Reference Pring1977), and K'atun Red from Holmul (Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada Reference Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada2016:36–41). The compact variant of Cansayab Orange shares attributes with Chicago Orange (Kosakowski Reference Kosakowski1987:21–22). Further, the mottled brown materials that occur in very small quantities described above could be local analogs to Mo Mottled from the Belize Valley and eastern Peten (Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada Reference Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada2016:50; Neivens de Estrada Reference Neivens de Estrada and Braswell2014:191; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Brown, Awe, Morris, Jones, Awe, Thompson and Helmke2009). However, these intersite comparisons remain conjectural pending formal in-person comparisons.

Form repertoires of unslipped ceramics noted in Ch'ok are also evident in pre-Mamom ceramic traditions in the Maya Lowlands. The prevalence of bowl and dish forms in the Xkeulil group have analogs in unslipped burnished groups in other early Middle Preclassic complexes, perhaps representing a local variant of this broader tradition. The frequency of unslipped and unslipped incised bowls and dishes is one of the clearest differentiators of early and late Middle Preclassic unslipped ceramics in the Champotón River drainage.

The red-on-white and red-on-cream dichromes that are particularly common in Ch'ok complex have also been noted in Cunil, Xe, and Eb sphere complexes (Awe Reference Awe1992; Kosakowski Reference Kosakowski1987; Kosakowski and Pring Reference Kosakowski and Pring1998). Fine-line incisions are a common decorative mode in pre-Mamom complexes, including cross-hatched and zoned patterns (Andrews V Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990; Ball and Taschek Reference Ball and Taschek2003; Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Cheetham Reference Cheetham and Powis2005; Clark and Cheetham Reference Clark, Cheetham and Parkinson2002). Geometric post-fire incisions are particularly notable among Ek complex materials initially documented at Komchen (Andrews V Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990). Similar materials have been documented at multiple sites in northeastern Yucatan and the Puuc Hills, likely representing a regional sphere (Andrews V and Bey III Reference Andrews, Bey and Walker2022; Andrews V et al. Reference Andrews, Bey, Gunn, Brown and Bey2018). Yet elaborate geometric incised designs seem less prominent in Ch'ok than other contemporary traditions in the Maya area, particularly from northern Yucatan. Diagnostic modes, including dishes with highly everted rims and incised post-fire motifs on the interior lip common in the Cunil and Eb traditions of the interior Lowlands, have not been documented in Ch'ok. Although present, elaborate incised designs reported in other pre-Mamom complexes are less prevalent in the Champotón River drainage.

Ch'ok complex dichromes share notable similarities with early Middle Formative pottery from outside the Maya Lowlands, including the Soconusco, the northern Guatemalan highlands, Chiapa de Corzo, and the Valley of Oaxaca (Coe and Flannery Reference Coe and Flannery1967; Dixon Reference Dixon1959; Kosakowski and Pring Reference Kosakowski and Pring1998:59; Sharer and Sedat Reference Sharer and Sedat1987). This red/white dichrome tradition appears across Mesoamerica at the transition between the Early and Middle Formative, with red-on-white dichromes giving way to zoned red-and-white decorations sometime around 800–700 b.c. (Coe and Flannery Reference Coe and Flannery1967:37–40). Sak Chac Red-on-white from the Ch'ok complex conforms to the earlier tradition, with zoned dichromes of the Muxanal group occurring in small but notable quantities in the ensuing Ahal complex.

Synthesis of extant data indicates a high degree of variability among the initial ceramic complexes in the Maya Lowlands. This regionalization could reflect a balkanized political landscape consisting of poorly connected villages, or even a high degree of ethnic diversity among the first sedentary groups in the Maya Lowlands (Figure 1). Ch'ok represents one of several contemporaneous small-scale regional spheres that existed between 1100 and 700 b.c.

Chronological Placement

Our understanding of the chronological placement of the Ch'ok complex has been limited by a lack of absolute dates from sealed stratigraphic contexts. However, all contexts with Ch'ok ceramics were identified in the lowest levels of excavations, often in pure contexts beneath levels pertaining to the later Ahal complex. Current evidence is consistent with Ch'ok as a unitary functional complex, as opposed to an early subassemblage that co-existed with Mamom sphere ceramics. These data indicate the temporal priority of Ch'ok in the Champotón ceramic sequence. Likewise, there is little evidence that Ch'ok has a direct developmental relationship with later ceramics of the Ahal complex.

As outlined above, the Ch'ok complex shares modal similarities with securely dated complexes from other parts of the Maya Lowlands. Although there remains some controversy of the precise dating of the initial appearance of pottery in the Maya area (Walker Reference Walker2022), an increasing body of data supports a chronological placement of 1100–600 b.c. (Adams Reference Adams1971; Andrews V Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990; Awe Reference Awe1992; Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada Reference Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada2016; Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Aoyama, Castillo and Yonenobu2013, Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015; Kosakowski and Pring Reference Kosakowski and Pring1998; Lohse Reference Lohse2010; Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975). Within this span of five centuries there is some evidence that coastal assemblages initially appear in the earlier part of this range, with inland sites toward the latter facet (see below). However, this hypothesis remains tentative, pending further empirical evaluation.

Spatial Distribution of Ch'ok

Contexts with significant quantities of Ch'ok ceramics were documented at four sites in the Champotón River drainage: the modern city of Champotón, Niop, San Dimas, and Ulumal (Figure 2, Table 5). Ch'ok pottery was encountered in deeply buried strata in all cases, including sealed stratigraphic contexts beneath Ahal complex deposits at the coastal sites of Champotón and Niop. There is a strong correlation between the spatial distributions of Ch'ok and Ahal, part of a consistent locational pattern documented in pre-Mamom complexes across the Maya Lowlands. These data could indicate either continuity in populations that produced and consumed pre-Mamom and Mamom ceramics, or sampling bias toward sites with occupational continuity into later eras. Yet the stratigraphic and attribute data indicate that the transition between pre-Mamom and Mamom pottery reflects a major transition. As outlined above, Ch'ok and Ahal are documented in pure contexts, with a lack of clear evidence for developmental relationships. This supports both the temporal priority of the former and their existence as separate entities. The most parsimonious explanation for these patterns is shifting spheres of ceramic influences and relatively rapid adoption of new ceramic traditions. Whether this took place within a single population or was embedded in demographic processes (as outlined in the “Zoque hypothesis”; Andrews V Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990; Ball and Taschek Reference Ball and Taschek2003) remains unclear.

The provisional identifications of early (coastal) and later (inland) facets of the Ch'ok complex could reflect the economic foundations of the initial development of sedentism and ceramic use in the Champotón River drainage. Ch'ok materials with close modal similarities with early Real ceramics were encountered near the mouth of the Champotón River and adjacent coastal margin. These unmixed and possibly earliest Ch'ok deposits were documented near marine and estuary zones, including the estuaries of the lower Champotón River and adjacent mangroves along the Gulf Coast (Ek Reference Ek2015). This spatial pattern could indicate the importance of marine food resources associated with the transition to sedentism. Ch'ok ceramics were associated with Melongena bispinosa (crown conch) and Crassostrea rhizophorae (mangrove oyster). Both species share a similar habitat in intertidal and estuary zones. Although oysters no longer exist in the Champotón River due to pollution and overfishing, they were important resources in ancestral Maya subsistence economies during later pre-Contact eras (Collier Reference Collier and West1964; Ruz Lhullier Reference Ruz Lhullier1969:15–30).

Ceramics sharing stronger affinities with later facets of Real were encountered at the inland centers of San Dimas and Ulumal, located along the edges of the Champotón River floodplain. This setting would facilitate access to a greater mix of agricultural settings along the river floodplain margin, as well as resources along the river. Soils along the floodplain include humic vertisols: moderately fertile and easily cultivated soils with high water retention capacity. The middle to upper reaches of the Champotón River support productive fisheries and a wide range of wildlife. This setting would have been well-suited to a subsistence economy with increasing focus on domesticates. These spatial patterns could indicate the importance of marine and estuary food resources during the transition towards sedentism. A similar pattern has been observed in other parts of Mesoamerica, with the development of increasing sedentism supported by exploitation of highly productive floodplain, riverine, and estuary resources in the Early Preclassic period (Arnold Reference Arnold2009; Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2001). The Champotón data could reflect a similar process: initial adoption of pottery and village life based on a mixed subsistence system incorporating diverse marine food resources, with a gradually increasing reliance on a narrower range of cultivated plants through time. These historical developments mirror processes associated with the Preformative stage within the original Willey and Phillips chronology (Table 1).

Despite documentation of Ch'ok contexts within multiple sites in the region, it is important to reiterate the current limits in our understanding of this critical era. One current inadequacy is a lack of clear architectural correlations, with Ch'ok materials encountered in off-mound testing adjacent to constructions pertaining to later periods. Since the CRSS excavations did not penetrate architecture, we know little about the construction histories of associated structures. An additional problem is a near complete lack of chipped cryptocrystalline silicate (CCS) tools dating to this era. This could simply be sampling bias or might reflect more fundamental differences in regional tool production industries. Likewise, no greenstone or obsidian artifacts were encountered from Ch'ok contexts. As with CCS, this could be due to sampling bias. However, it is more likely that obsidian was less readily available and consumed in fundamentally different ways than in subseuqent eras. The CRSS excavations recovered substantial assemblages of obsidian implements, with a gradually increasing frequency through the Preclassic and Classic, reaching a peak in the Late Postclassic. During the late Middle and Late Preclassic, obsidian was procured from the Chayal source in highland Guatemala (Ek Reference Ek2015:586–639). Information currently available indicates that interaction spheres of the early Middle Preclassic were focused on pan-Mesoamerican links to the west and were largely limited to information: material culture styles and iconography. It would not be until the subsequent Ahal complex that interaction spheres would shift to the interior Maya Lowlands and broaden to include obsidian commerce.

The transition between Ch'ok and the later Ahal complex witnessed dramatic changes, representing a tipping point in Maya history. While deposits with Ch'ok ceramics were consistently identified beneath later Ahal contexts, the two complexes differ markedly in pastes, form repertoire, and decorative techniques. Further, these two complexes evince distinctive patterns of interactions with other regions: while Ch'ok reflects a regional tradition with links to other parts of Mesoamerica, Ahal is a participant in a much more homogeneous pan-Maya material culture phenomenon.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE FIRST DISTINCTIVELY “MAYA” MATERIAL CULTURE TRADITION

The transition between Ch'ok and Ahal represents a major inflection point in Champotón regional history. The Ahal complex was a participant in the earliest autochthonous Maya ceramic tradition: the Mamom ceramic sphere. In contrast to the regionalized expressions of a broader pan-Mesoamerican horizon in the early Middle Preclassic (Figure 1), the latter part of the Middle Preclassic witnessed the development of a more homogeneous material culture tradition. The Mamom sphere is very well-documented across the Maya area, characterized by distinctive waxy slips, consistent form repertoires, a high degree of technological sophistication, and a strengthening of interregional ceramic affinities within the Maya Lowlands.

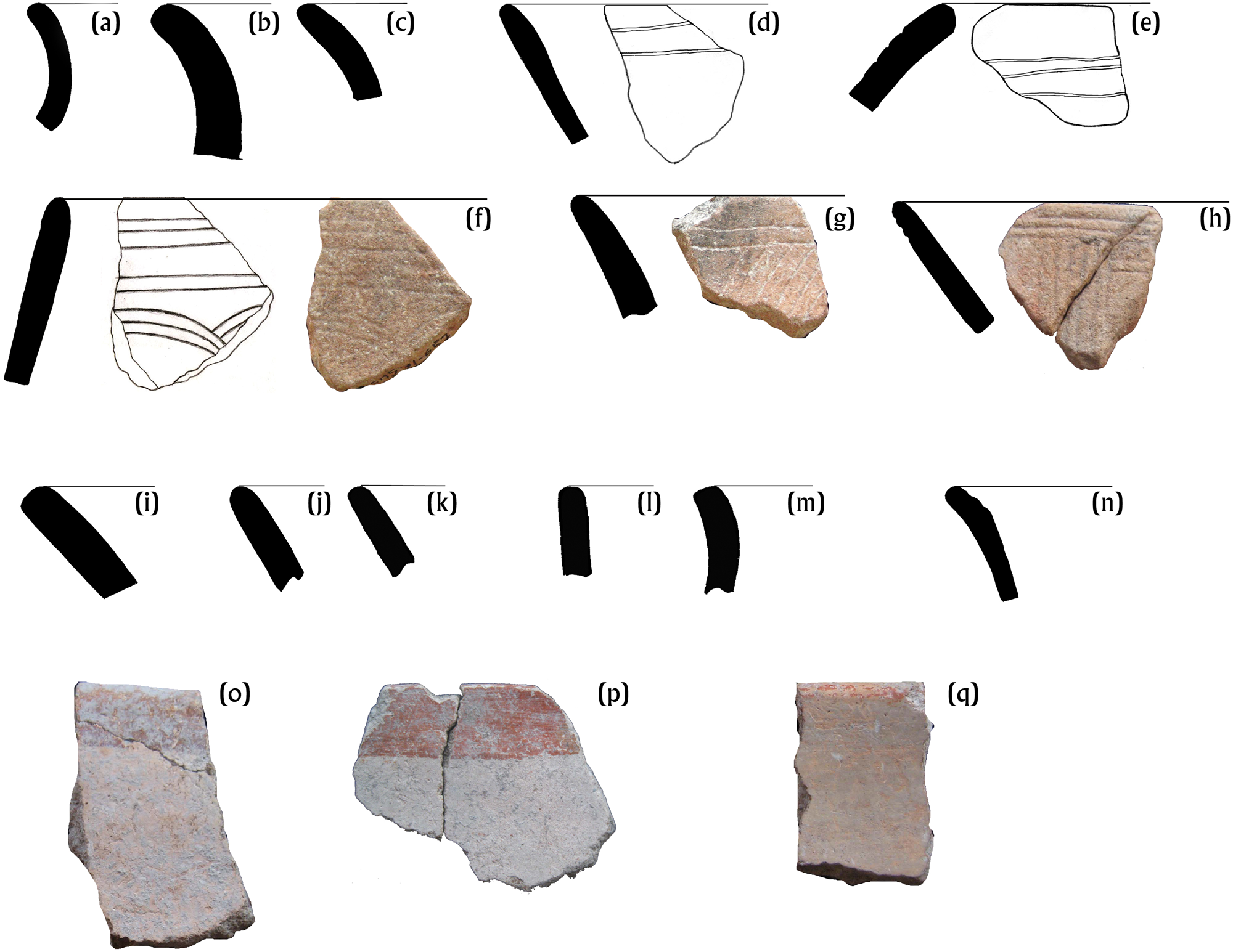

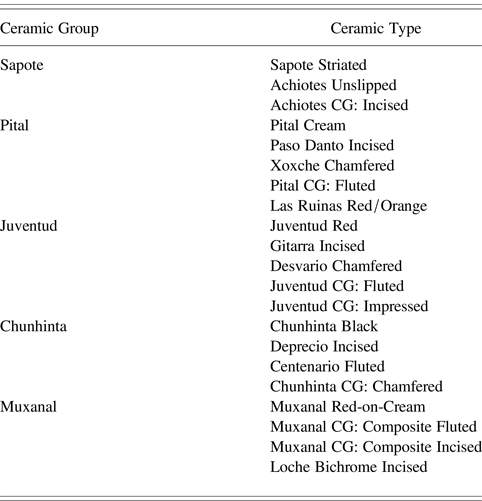

The Ahal complex includes common Mamom-sphere ceramic groups, including Joventud, Pital, Chunhinta, Muxanal, and Achiotes (Table 6; Andrews V Reference Andrews1988, Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990; Forsyth Reference Forsyth1983, Reference Forsyth1989, Reference Forsyth2019; Kosakowski Reference Kosakowski1987; Kosakowski and Pring Reference Kosakowski and Pring1998; Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975; Smith Reference Smith1955; Smith and Gifford Reference Smith and Gifford1966). Muxanal Red-on-cream is particularly common in the Champotón assemblage, characterized by well-executed zonal patterns and composite decorations. Compared with the previous period, Ahal pottery displays more complete firing and greater intraregional consistency. These attributes reflect a higher degree of technological sophistication in ceramic production industries. The transition between the early and late facets of the Middle Preclassic reflects a major change in ceramic affinities, with little evidence for a developmental relationship between the Ch'ok and Ahal pottery traditions.

Table 6. Major constituent ceramic groups and types of the Ahal (Champotón 1B) complex. The groups and types are diagnostic of the Mamom ceramic sphere, signifying participation of Champotón communities in the first large-scale ceramic tradition in the Maya Lowlands.

Mamom sphere ceramics are well represented in sites throughout the region. Most sites along the central Campeche coast tested by the CRSS were occupied during this era, indicating population growth (Anaya Cancino et al. Reference Anaya Cancino, Ojeda Más, Salazar Aguilar, López, Suárez Aguilar, LaPorte, Arroyo and Mejía2009; Ball Reference Ball1977, Reference Ball1978; Ball and Taschek Reference Ball and Taschek2015; Benavides Castillo Reference Benavides Castillo2003, Reference Benavides Castillo2005; Ek Reference Ek and Cobos2012a, Reference Ek2015; Folan et al. Reference Folan, López, Heredia, Trujeque, Folan, Forsyth, Tiesler, Gómez, Cen, Bishop, Bowles, Braswell, Ek, Gunn, Götz, Vallanueva, Blanso, Gunam, Carrasco, Noble and Palma2013; Ford Reference Ford1986; Forsyth Reference Forsyth1983, Reference Forsyth2008, Reference Forsyth2019; Nelson Reference Nelson1973; Suárez Aguillar and Ojeda Mas Reference Suárez Aguilar and Ojeda Mas1996; Suárez Aguilar et al. Reference Suárez Aguilar, Ojeda Mas, Aragón, Arroyo, Palma and Aragón2010; Vargas Pacheco Reference Vargas Pacheco2001a, Reference Vargas Pacheco2001b; Williams-Beck Reference Williams-Beck and Prem1994). Despite a notable degree of homogeneity, studies of paste composition indicate local production of most Mamom sphere ceramics (Stanton and Ardren Reference Stanton and Ardren2005:214). Correspondences among complexes incorporated in the Mamom sphere reflect a notable increase in interaction among potters across the Maya area compared with the preceding era (Forsyth Reference Forsyth2008:213–214). The first evidence for obsidian exchange also dates to this period, with materials from the Guatemalan highlands (particularly the Chayal source) appearing in low densities (Ek Reference Ek2015:605–616). Although the catalysts of this homogeneity remain unclear, existing evidence reflects a reduction in barriers to the movement of information during this period.

In summary, a major transformation took place within Champotón sometime between the eighth and seventh centuries b.c. While the earliest pottery reflects participation in a regionalized ceramic system, the shift from the Ch'ok to Ahal complexes marks the inclusion of Champotón into a pan-Maya ceramic tradition that would persist for several centuries. Based on currently available evidence, the most parsimonious explanation for this transition is adoption of a new and distinctly Maya ceramic tradition that initially developed in northern Belize and expanded to encompass much of the Maya area (Andrews V Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990; Kosakowski and Pring Reference Kosakowski and Pring1998:64; Lohse Reference Lohse2010; Walker Reference Walker2022). While the preceding era is characterized by peripheral membership within an expansive Mesoamerican horizon among several small-scale ceramic spheres, the development of the Mamom sphere marks the beginning of a much more inclusive and distinctively Maya material culture tradition. Questions remain concerning the broader political, economic, and social processes in which these phenomena were embedded. However, it is clear that sedentary village life had become the dominant norm across the Maya area, with information and likely goods flowing readily between communities.

EIGHT CENTURIES OF CONSERVATISM AND CONTINUITY

In contrast to the abrupt shift between the Ch'ok and Ahal complexes, the transition between Ahal and the subsequent Pasaj complexes was gradual. Participation in this widespread and homogeneous waxy-ware tradition extends through the end of the Late Preclassic period. The Pasaj complex was a full participant in the most extensively and consistently documented ceramic tradition in the Maya area: the Chicanel sphere. The Chicanel sphere had an even broader geographic distribution, with remarkable consistency across most of the Maya Lowlands.

The Chicanel complex shares many attributes with the earlier Mamom sphere, with clear evidence for a direct developmental relationship. In fact, at Champotón the dividing line between Ahal and Pasaj is largely arbitrary, with intermediate forms clearly evident. Despite the long period of use, conservatism in the production and consumption of waxy-ware ceramics complicates the delimitation of temporal facets. Together, the Ahal and Pasaj complexes represent an ongoing ceramic tradition that demonstrates remarkable continuity over the course of eight centuries.

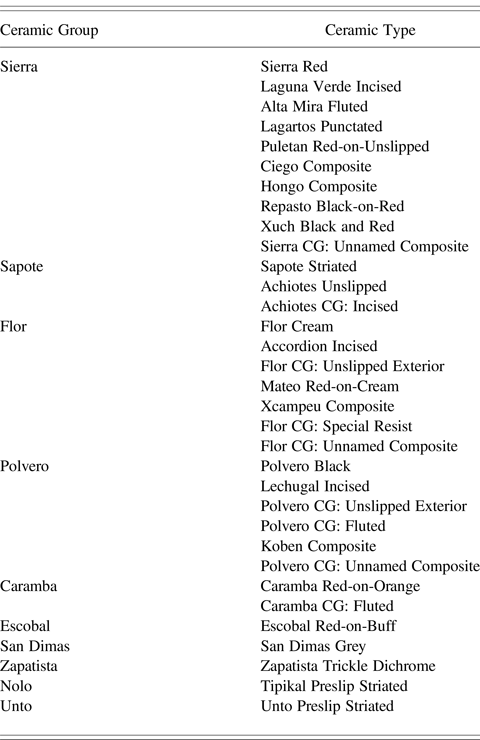

The predominant groups in the Pasaj complex include Sierra, Polvero, Flor, and Mateo, with a relatively high diversity of minority groups, including Mateo, Xuch, and Zapatista (Table 7). A regional variant of this tradition defined by frequencies of a few forms and modes has been documented across much of central Campeche (Forsyth Reference Forsyth1983:33–37, Reference Forsyth2019:212–213). Yet distinctions between other regions are subtle, including higher frequencies of composite surface treatments (particularly slipped vessels with unslipped and striated exteriors). Despite this regional variation, the Pasaj complex is a full participant in the Chicanel sphere.

Table 7. Major constituent ceramic groups and types of the Pasaj (Champotón 2) complex. The groups and types are diagnostic of the Chicanel ceramic sphere, with notable similarities with Chicanel sphere materials from across the Maya Lowlands.

During the Ahal and Pasaj eras, we have a more complete view of settlement patterns and regional economic systems. Demographic expansion is reflected in all parts of the region, with expansion of communities along the coast, as well as establishment of major centers inland along the Champotón River waterway. Increasing sociopolitical complexity is evident in monumental architecture and regional demographic expansion. Communities expanded across the coastal margin, with research along the littoral revealing a continuous distribution of residential groups. Central places with public monumental architecture have been documented within this continuous settlement matrix at Champotón and Moquel, with smaller centers in Niop and Rancho Potrero Grande (Figure 2). The largest inland centers in the region—Ulumal and San Dimas—also had extensive Ahal occupations. These places emerged as central nodes of public life no later than this period.

Excavations within the modern city of Champotón by the Universidad Autónoma de Campeche indicate population growth and conspicuous investments in monumental architecture, with Champotón rising to regional prominence during this period (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Morales, Dominguez, Ruiz, Heredia, Gunn, Florey, Barredo, Hernandez and Bolles2002, Reference Folan, Folan, Morales, Heredia, Blos, Bolles, Ruiz and Gunn2003, Reference Folan, López, Trujeque, Heredia, Folan, Bolles and Gunn2004). The primary complex in Group 1 consists of a massive platform, measuring over 54 × 54 m in area and 8 m in height, which supported three superstructures (Figure 6; Folan et al. Reference Folan, Gunn, Carrasco, Inomata and Houston2001, Reference Folan, Folan, Morales, Heredia, Blos, Bolles, Ruiz and Gunn2003, Reference Folan, López, Heredia, Trujeque, Folan, Bolles, Gunn, Carrasco, Pacheco and Castillo2007; Forsyth Reference Forsyth2008:216, Reference Forsyth2019; Forsyth and Folan Reference Forsyth, Folan and Forsyth2019). This structure was occupied by the late Middle Preclassic and reached its maximum size by the Late Preclassic period. This triadic architectural template has been documented in contemporary centers across the Maya Lowlands (Anderson Reference Anderson2011; Awe et al. Reference Awe, Hoggarth, Aimers, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017; Folan et al. Reference Folan, Gunn, Carrasco, Inomata and Houston2001; Mathews Reference Mathews, Fedick and Taube1995, Reference Mathews1998; Mathews and Maldonado Cárdenas Reference Mathews, Cárdenas, Mathews and Morrison2006; Vargas Pacheco Reference Vargas Pacheco2001a). The principal platform shares characteristics with the megalithic style documented in the Late Preclassic period in the Northern Lowlands, including rounded corners and use of megalithic stones over a meter in length (Mathews and Maldonado Cárdenas Reference Mathews, Cárdenas, Mathews and Morrison2006:98–100). The Group 1 platform differs from the latter tradition in the use of finely cut and extremely large stones tightly fitted together without use of crushed stone chinking. Structure 1 in Group 1 includes multiple stones weighing in excess of 250 kg, with the monolithic stair on the north side of the structure built using elements more than 7 m in length (Forsyth and Folan Reference Forsyth, Folan and Forsyth2019; Folan et al. Reference Folan, Morales, Dominguez, Ruiz, Heredia, Gunn, Florey, Barredo, Hernandez and Bolles2002, Reference Folan, López, Trujeque, Heredia, Folan, Bolles and Gunn2004).

Figure 6. Plan and reconstruction of Group 1, Champotón. Adapted from Folan et al. Reference Folan, López, Heredia, Trujeque, Folan, Bolles, Gunn, Carrasco, Pacheco and Castillo2007; Forsyth and Folan Reference Forsyth, Folan and Forsyth2019.

Group 1 is the largest existing structure within the city of Champotón. Although most of the epicenter of ancient Champotón has been heavily impacted by continuous occupation, extensive distributions of megalithic stones throughout the modern city provide a hint of the extent and scale of the ancient center. It is very likely that Champotón emerged as one of the largest centers along the Campeche coast by the Late Preclassic period (Ek Reference Ek and Cobos2012a, Reference Ek2015, Reference Ek and Walker2022; Folan et al. Reference Folan, Morales, Dominguez, Ruiz, Heredia, Gunn, Florey, Barredo, Hernandez and Bolles2002, Reference Folan, Folan, Morales, Heredia, Blos, Bolles, Ruiz and Gunn2003, Reference Folan, López, Trujeque, Heredia, Folan, Bolles and Gunn2004, Reference Folan, López, Heredia, Trujeque, Folan, Bolles, Gunn, Carrasco, Pacheco and Castillo2007, Reference Folan, López, Heredia, Trujeque, Folan, Forsyth, Tiesler, Gómez, Cen, Bishop, Bowles, Braswell, Ek, Gunn, Götz, Vallanueva, Blanso, Gunam, Carrasco, Noble and Palma2013; Forsyth Reference Forsyth2008, Reference Forsyth and Palma2012, Reference Forsyth2019).

We also have a better understanding of regional economic systems and human-environmental interactions during the latter part of the Preclassic period. Existing evidence reflects the development of a diversified regional subsistence system. Faunal assemblages from coastal settlements in Champotón indicate the exploitation of a wide range of marine resources (Ek Reference Ek and Braswell2012b, Reference Ek2015). The development of agricultural communities in the upper reaches of the Champotón River is concentrated initially along the floodplain, facilitating access to flat terrain dominated by humic vertisols. Due to high capacity for water retention, humic vertisols can help to mitigate risks associated with seasonal and erratic rains. The main management challenge with cultivation in humic vertisols is management of excess water. During the Formative period there is little evidence for investments in agricultural infrastructure to facilitate exploitation of upland soils. The most common implements in the lithic tool assemblage from the two inland centers of Ulumal and San Dimas are associated with agricultural activities. These implements were part of a local or perhaps regional exchange system, with evidence for production at the site of San Dimas. Obsidian from Highland Guatemalan sources appear in household assemblages, although in lower frequencies than later eras (Ek Reference Ek2015:605–615). These data indicate some access to exotic materials, but no evidence of widespread consumption as a basic part of regional economies.

The preponderance of evidence suggests a period of population growth supported by previously unexploited or underexploited resources from the late Middle Preclassic through the end of the Late Preclassic period. This era of growth included a major expansion of the population across the region, but with little evidence of intensification of food production. In other publications I refer to this set of human-environmental dynamics of the Preclassic period as the Localized Extensive Diversified socio-ecological regime (Ek Reference Ek2015:640–733, Reference Ek, Carrasco, Gómora, Torres and Méndez2018). The characteristics of the regime include extensive settlements, local subsistence economies, and the exploitation of diverse food resources in different eco-zones. During this period, it is likely that growing populations took advantage of relatively abundant food resources, including marine and estuarine fisheries and moderately fertile but easily cultivable soils along the floodplain of the Champotón River. The subsistence economy—as well as the production and exchange of most commodities—were local in scale. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that the Ahal and Pasaj complexes developed within this broader context characterized by conservatism and growth over the course of at least eight centuries.

In aggregate, the era from the start of the late Middle Preclassic and extending through the close of the Late Preclassic was marked by the adoption of a unified material culture tradition that linked communities across the Maya Lowlands. The waxy-ware tradition was part of a broader suite of material culture traits that could be characterized as broadly “Maya” in nature and distribution. This broader ceramic tradition was marked by widespread distribution, homogeneity, and remarkable continuity over approximately eight centuries. Although questions remain about the political, economic, or social mechanisms which might explain this conservatism, most of the key developments that unfolded in association with the Mamom sphere intensify during the ensuing Late Preclassic, including full adoption of agricultural lifeways, population grown, urbanization, and the development of a distinctive Maya material and visual culture tradition.

RECONSIDERING EARLY MAYA CHRONOLOGICAL FRAMEWORKS

Chronological frameworks influence the way we think about the past, with the potential to either promote or hinder the development of new theories of social change. The gradual metamorphosis of the Willey/Phillips framework from a developmental to absolute chronology has created a disjunction between our system of periodization and the empirical record. Due to a failure to engage in episodic revision over the course of generations of research, the gap between this chronological framework and empirical evidence continues to widen. The ongoing use of this system without amendments or critical evaluation is justifiable only by superficial utility as an expedient reference to fixed chronological periods.

As change in human societies is often characterized by punctuated equilibria, the ways we classify periods of time should conform to our best understanding of episodic political, social, economic, and ecological reorganizations. We thus return to the original formulation of the Willey/Phillips framework, outlined in Table 1, to reconsider how extant information might best fit into this set of heuristics untethered to largely outdated understanding of their temporal placement. In this endeavor, analytical separation of developmental phases and periods is useful. As different types of social phenomena can have variable temporalities, chronological frameworks with nested temporal scales can provide a useful conceptual foundation (Bintliff Reference Bintliff1991; Braudel Reference Braudel1958; Iannone Reference Iannone2002; Knapp Reference Knapp1992; Smith Reference Smith and Knapp1992).

The Nascent Formative: Islands of Complexity (1100–600 b.c.)

Sedentary agricultural life is a foundational element in the definition of Mesoamerican culture. Proxies for the development of these distinguishing characteristics include habitual dietary reliance on domesticates, sedentism, and ceramic use. Yet the appearance of domesticated maize dates as far back as 3400 b.c. (Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Josserand1996), with corn as a viable staple product by 2200 b.c. (Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Thakar, VanDerwarker, Webster, Culleton, Harper, Kistler, Scheffler and Hirth2017). The adoption of agricultural lifestyles is not evident until the beginning of the second millennium b.c. (Blake Reference Blake2015; Clark et al. Reference Clark, Pye, Gosser, Lowe and Pye2007; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015; Lohse Reference Lohse2010, Reference Lohse and Walker2022; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2010, Reference Rosenswig and Lesure2011, Reference Rosenswig2015; Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, VanDerwarker, Culleton and Kennett2015). By 1000 b.c. there is unambiguous evidence for ceramic production and consumption within multiple areas of the Maya Lowlands (Figure 1). The earliest documented constructions of communal ritual spaces date to the ensuing centuries. These new dynamics are all consistent with the culmination of the Preformative—a gradual transition to the full adoption of Formative lifeways—as outlined in the Willey/Phillips framework. Thus, the end of the first millennium b.c. represents a watershed moment in the Maya past.

Existing data indicate that the initial adoption of sedentism was not a wholesale transition, but a new lifestyle adopted by communities interspersed among mobile neighbors. Rosenswig (Reference Rosenswig and Lesure2011, Reference Rosenswig and Hodos2016) refers to these early experiments with agricultural life as “islands” of complexity. One of the most notable features of this pivotal era is the consistent association with a shared set of symbolism and iconography that was pan-Mesoamerican in scale. However, there seems to be little evidence for adoption of common ceramic production technologies. Variability in the first ceramic complexes in the Maya Lowlands is likely the product of localized production of pottery conforming to shared practices (Bill Reference Bill and Aimers2013:34–39). This is reflected by the marked intra-regional variability of the Ch'ok complex within the Champotón River drainage, as well as differences between pre-Mamom ceramic complexes across the Maya area (Figure 1). Extant data reflect relatively small-scale communities of ceramic producers with distinctive practices, norms, and technologies. This pattern of regionalization differs markedly from latter eras following the appearance of the Mamom sphere. The dispersion of these communities, and the nature of links between them, are consistent with Rosenswig's (Reference Rosenswig and Lesure2011, Reference Rosenswig2015, Reference Rosenswig and Hodos2016) archipelago analogy. The adoption of a shared visual culture reflected in this early Mesoamerican horizon likely reflects the importance of shared practices and ideologies in the initial development of central places for communal ritual.

The Preformative/Formative transition is reflected in the gap between evidence for maize agriculture and evidence of ceramic use. Likewise, the balkanization of ceramic spheres during this era, with a high degree of variability between ceramic complexes across the Maya Lowlands, is consistent with dispersed adoption of village life. However, these spheres share important similarities in decorative modes that reflect participation in a broader emergent system of interaction.

Developments that took place sometime between 1100 and 600 b.c. reflect a major point of disconnect between the original intent of the Willey/Phillips developmental sequence and its subsequent metamorphosis into an absolute chronology. Based on the currently accepted boundaries between major periods within the Maya variant of the Mesoamerican chronological framework, the dynamics outlined above would begin at the end of the Early Preclassic and extend into the first few centuries of the Middle Preclassic. Yet in the Maya area this represents the earliest evidence for the adoption of Formative lifeways, and thus the beginning of the Formative stage as envisioned by Willey and Phillips.

Besides lack of congruence between developmental phases and periods, our current nomenclature fails to correlate key long-term historical thresholds with high-level chronological eras. Characterizing the entire time span between 1000 and 250 b.c. as a single “Middle Preclassic” period glosses over critical changes that take place during this era. If the goal of periodization is to organize the chaos of the past into units useful for delimiting and understanding processes of political, economic, and social change, conflating most of the first millennium b.c. into a single period is not just counterproductive, but misleading. The era between 1100 and 600 b.c. represents a key moment in Maya history, differing in important ways from the ensuing era. Delimiting this by faceting—the early and late Middle Preclassic—places primacy on the chronological system in lieu of empirically evident contours of history. To avoid confusion that would result from the redefinition of terms already in widespread use, neologism is a viable alternative. I suggest we adopt the term Nascent Formative to classify the era corresponding to the initial adoption of sedentism, ceramics, and pan-Mesoamerican iconographic systems in the Maya area. Alternatively, terms like “Cunil Horizon” (Cheetham Reference Cheetham and Powis2005) highlight some important defining attributes of material culture traditions during this time period: adoption of a shared set of symbolism, iconography, and decorative modes across dispersed local ceramic traditions. However, the value of analytical separation between horizons (defined by visual culture) and periods also lends support for new chronological terminology.