In recent years, there has been increased interest in the linguistic competence of adult early bilinguals of minority languages, also called heritage language speakers in the context of the United States (Au, Knightly, Jun & Oh, Reference Au, Knightly, Jun and Oh2002; Montrul, Reference Montrul2008; Polinsky Reference Polinsky2007, Reference Polinsky2008a, Reference Polinskyb; Valdés, Reference Valdés2000). Although heritage speakers were typically exposed to the family language and the majority language early in life, as adults many have weaker command of the family language than of the majority language. This population is quite diverse and heterogeneous. Proficiency in the heritage language can range from minimal to advanced levels of attainment and everything else in-between. Potential reasons for why many of these bilinguals may be less fluent in the family language than in the community language are numerous, but two possibilities that have been entertained in the literature are incomplete acquisition and/or attrition in childhood as a result of both language contact and reduced input and use of the language (Montrul, Reference Montrul2002, Reference Montrul2008; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2007; Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán1994). Incomplete acquisition may occur if the bilinguals were still in the process of acquiring the family language when use of the majority language intensified. More frequent and extensive use of the majority language brings about reduced exposure to the family language, and reduced opportunities for using the family language. If language attrition in childhood occurred, the bilinguals may have lost aspects of the family language already acquired in early childhood some time in late childhood or early adolescence, perhaps due to use of the majority language and absence of schooling in the minority language (Anderson, Reference Anderson1999; Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán1994, Reference Silva-Corvalán, Montrul and Ordóñez2003). Most studies of adult heritage speakers to date have focused on the minority language only because it is assumed that this language has not developed fully, or is incompletely mastered. Because these studies involve cross-sectional rather than longitudinal data, incomplete acquisition or attrition is typically assessed by comparing these bilinguals’ linguistic abilities in the heritage language to the linguistic abilities of monolingually raised and educated counterparts, who are assumed to display full and “stable” linguistic competence in the same language. Ideally, more longitudinal studies of heritage language children spanning several years, studies like Anderson (Reference Anderson1999) and Silva-Corvalán (Reference Silva-Corvalán, Montrul and Ordóñez2003), should be conducted.

In addition to demonstrating variability or loss with respect to the full variety spoken by monolinguals, above-mentioned studies have assumed that the minority language is also functionally weaker than the L2 or community language, which has become primary (Seliger, Reference Seliger, Ritchie and Bhatia1996). This assumption is not surprising and may stem from the fact that in second language acquisition, for example, the functionally and psycholinguistically stronger L1 representation at all levels of linguistic analysis (phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics) is transferred to different degrees during L2 development, with its stronger influence being at beginning and intermediate stages (see Schwartz & Sprouse, Reference Schwartz and Sprouse1996, for morphosyntax). Similarly, Seliger (Reference Seliger, Ritchie and Bhatia1996), who hypothesized five stages of possible relationships between the L1 and the L2 in bilingualism, considers that attrition sets in at stage 4, when the L2 becomes functionally dominant, and transfer now occurs from the L2 to the L1 (see Montrul, Reference Montrul2010; Montrul & Bowles, Reference Montrul and Bowles2009; Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko, Schmid, Köpke, Keijzer and Weilemar2004). Except for Montrul's (Reference Montrul2006) study of lexical semantics in Spanish heritage speakers, which has looked at Spanish heritage speakers in their two languages, most studies have not tested whether, in fact, the L2 (the sociolinguistically dominant language) is also psycholinguistically stronger than the L1 (the heritage language) of these bilinguals. Reduced input during childhood has been claimed to be a significant factor underlying non-native outcomes in many child and adult heritage speakers.

However, input-related frequency and reduced exposure are not the only factors involved (O'Grady, Lee & Lee, Reference O'Grady, Lee and Lee2008). It is also possible that the morphosyntactic and semantic reductions and regressions observed in many heritage languages may be the result of extensive contact with English, or transfer. Since English has more rigid word order, does not mark case overtly, and lacks the rich nominal and verbal inflectional system of Russian and Spanish, for instance, a great deal of the morphosyntactic simplification observed in these heritage language grammars can also be attributed to transfer from English. Typically, knowledge of the minority language, and not the majority language, is investigated in heritage language studies. Naturally, when focusing on properties such as subjunctive, gender and case, it is not possible to study the majority language, since English lacks these properties.

Montrul (Reference Montrul2006) investigated the lexical-semantic and syntactic properties of unaccusativity (the distribution of two classes of intransitive verbs) in a group of Spanish heritage speakers (with intermediate to advanced command of Spanish) in English and Spanish. Although English and Spanish both have unaccusative and unergative verbs, the syntactic reflexes of unaccusativity are very different in the two languages. Montrul found that despite some differences in accuracy and ratings of individual verbs, the heritage speakers were quite balanced and native-like on the syntactic effects of unaccusativity in the two languages when compared to a monolingual group in each language. Proficiency differences between the heritage speakers and the two native speaker groups attested in the proficiency tests and with self-ratings did not correlate with similar differences in the linguistic tasks testing unaccusativity in each language. Montrul concluded that a universal phenomenon like unaccusativity, which develops early in language acquisition and is manifested differently in each language, might not be prone to incomplete acquisition or transfer in unbalanced bilingual grammars.

Due to the scarcity of studies investigating the two languages in these types of bilinguals, the present study takes over the same research question and research design as Montrul (Reference Montrul2006), but in a different linguistic domain. The main contribution of the present study is that, unlike most prior studies, it investigates the two languages of adult heritage speakers and assesses both the dominance relationship between the languages, and whether there is transfer from the dominant language onto the weaker language. In order to investigate more directly the potential role of transfer from the dominant language this study focuses on knowledge of articles in Spanish and English. Unlike the case of unaccusativity, where there are important differences in individual verbs and in the syntactic reflexes in the two languages, article semantics is quite similar in Spanish and English, but not identical. As a result, article semantics may be a grammatical domain more prone to transfer than unaccusativity. Given that Spanish and English have definite and indefinite articles, although with somewhat different morphosyntactic distribution in certain contexts and subtly different semantics, articles are an ideal testing ground for examining potential cross-linguistic differences in the minority and the majority languages.

The purpose of this study, therefore, is to examine competence differences in the syntactic and semantic distribution of definite articles, with particular focus on transfer from the dominant language at the level of semantics. Although both Spanish and English have definite articles, the two languages vary somewhat in the interpretation of these articles in generic contexts and in inalienable possession constructions. A central question driving language attrition research from a linguistic perspective is what particular areas of grammar are prone to cross-linguistic influence (transfer), attrition and/or incomplete acquisition, and why. Montrul (Reference Montrul2008) makes a distinction between L1 attrition in adults and L1 attrition during childhood (incomplete acquisition) and argues that there are age effects in L1 attrition. Linguistic research on adult L1 attrition suggests that the syntax–pragmatics interface appears to be affected, but the syntax–semantics interface is not (Tsimpli & Sorace, Reference Tsimpli and Sorace2006). By contrast, when attrition occurs in childhood, Montrul (Reference Montrul2008) shows how the integrity of the entire grammatical system can be seriously compromised at several levels, affecting not only the syntax–discourse interface (Kim, Montrul & Yoon, Reference Kim, Montrul and Yoon2009) but also morphosyntax and some aspects of semantics (Montrul, Reference Montrul2002, Reference Montrul2004; Montrul, Foote & Perpiñán, Reference Montrul, Foote and Perpiñán2008; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2007, Reference Polinsky2008a, Reference Polinskyb; Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán1994; Song, O'Grady, Cho & Lee, Reference Song, O'Grady, Cho, Lee and Kim1997).

The present study is part of a larger research project investigating the acquisition of generic reference in adult L2 acquisition of Spanish and English and in Spanish heritage speakers, and is unique among heritage language studies in its focus on the interface between semantics and syntax in the two languages (but see Serratrice, Sorace, Filiaci and Baldo, Reference Serratrice, Sorace, Filiaci and Baldo2009, for an investigation of this topic with school age bilingual children in the UK and in Italy).Footnote 1 While Tsimpli and Sorace (Reference Tsimpli and Sorace2006) claim that this particular interface is not affected under attrition in adults or in late child bilingualism, we will show that it is indeed affected in Spanish heritage speakers, who are not cases of adult attrition but of childhood attrition or incomplete acquisition. Therefore, Montrul's (Reference Montrul2008) idea that the integrity of the native grammar is substantially affected in incomplete acquisition is supported by the data presented in this study. The semantic interpretation of articles in English and in Spanish, extensively investigated in theoretical linguistics, L1, bilingual and L2 acquisition, has not been investigated in adult bilinguals, and particularly those assumed to have unbalanced command of the two languages. To assess whether Spanish is weaker with respect to English and with respect to the linguistic competence of monolingual Spanish speakers, we present the results of three tasks in each language that look at the Spanish heritage speakers’ overall proficiency in each language and their syntactic and semantic representations of Spanish and English definite articles. Our results confirm that even when the Spanish skills are quite advanced in these heritage speakers, Spanish (the minority language) is indeed the weaker language, as demonstrated by the proficiency tests and some aspects of article use in the two languages.

Background

On the interpretation of definite articles with plural noun phrases in Spanish and English

Although Spanish and English both have definite and indefinite articles, English contrasts with Spanish and (most) Romance languages on the interpretation of articles with definite plurals. To express a generic concept or generic reference in English, the plural subject noun phrase may not take a definite article. In English, only bare plurals, but not definite plurals, can have generic interpretation, as illustrated in (1).Footnote 2 For example (1a), with a bare plural, is a statement about tigers in general, while (1b), with a definite plural, cannot be a statement about tigers in general. The only reading available to (1b) is that some salient tigers (e.g., the tigers in this zoo) eat meat – the same reading which is available to the demonstrative plural in (1c).Footnote 3 This reading is not available to (1a), which cannot be a statement about a specific group of tigers: bare plurals in English cannot have specific reference.Footnote 4

(1)

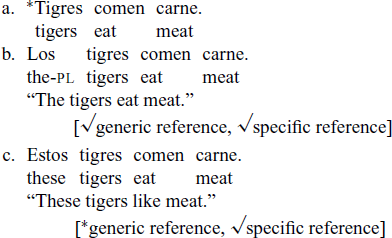

Unlike English, preverbal bare plurals are ungrammatical in Spanish, as in (2a). Like most Romance languages, Spanish uses definite plurals for generic reference, as shown in (2b). Thus, while definite plurals have both specific and generic readings in Spanish (2b), in English they only have specific reference, while genericity is expressed through bare plural NPs. Like in English, Spanish demonstrative plurals (estos) also have only specific readings, as in (2c).

(2)

Thus, while English has two plural forms (NP with definite determiner and bare NP) to express two meanings (specific, generic), Spanish has only one plural form (NP with definite determiner) on which to map the two meanings (specific, generic).

In addition to the expression of generic reference, there is another interesting semantic contrast between Spanish and English definite articles in inalienable possession constructions, a phenomenon which according to Vergnaud and Zubizarreta (Reference Vergnaud and Zubizarreta1992) is related to how generic reference is expressed in the two types of languages. Inalienable possession refers to possession of body parts, articles of clothing, and sometimes kinship terms. Consider examples (3) and (4), from Spanish and English, respectively.

(3)

(4) The boys raised the hand.

The Spanish example in (3) is ambiguous between an inalienable (the boys’ hands) and an alienable (somebody else's hand) interpretation. That is, one paraphrase is that the boys raised their own hands (the hands are integral parts of the boys), whereas the other interpretation is that the boys raised a hand that does not belong to the boys’ own bodies (the hand belongs to somebody else). Such ambiguity does not arise in the English sentence in (4): the most typical interpretation is alienable possession; that the hand belongs to somebody else. In order to express inalienable possession in English, a possessive determiner (their) is used, as in (5). The possessive determiner (su) is also possible in Spanish, as in (6), again with two possible meanings (alienable or inalienable possession), although the definite article is typically preferred for the inalienable possession interpretation. Note also that while English requires a plural NP (their hands), Spanish uses a singular NP (la mano/su mano), even when the NP has a plural, distributive meaning (each child raised his or her own hand).

(5) The boys raised their hands.

(6)

In fact, both alienable and inalienable possession interpretations are available to different degrees for possessive determiners in both Spanish and English. The main difference is that in English the inalienable interpretation is the default one for possessives – but the alienable one is in principle still possible; in Spanish, the alienable interpretation is in fact the default for possessives, but the inalienable is also still possible. This paper will show that these tendencies hold in our data.

Accounts of English/Spanish differences in definite plural interpretation

A particularly influential line of analysis of the cross-linguistic difference in generic reference ((1)–(2)) is that of Chierchia (Reference Chierchia1998) and Dayal (Reference Dayal2004), on which definite articles in English and Spanish have slightly different semantics. Definite articles in both languages lexicalize maximality: the tigers in (1b) denotes the maximal set of tigers in the discourse (e.g., the tigers just mentioned, the tigers visually present, etc.), and the same reading is available to los tigres in (2b). However, the Spanish definite article additionally lexicalizes the meaning of generic reference: los tigres in (2b) can denote either the maximal set of tigers (the specific reading), or the entire category/kind of tigers (the generic reading). On Chierchia's (Reference Chierchia1998) account, this is a result of cross-linguistic differences in NP denotation, which Chierchia captures under the Nominal Mapping Parameter. In English, a bare NP can be either an argument or a predicate; as an argument, it can denote a kind, as in (1a), so the definite article is not needed unless true maximality is being expressed, as in (1b). The use of a definite article where a bare NP is appropriate (with generic interpretation) is ruled out by an Avoid Structure Principle; according to this principle, additional structure (projecting a DP) is avoided when the relevant interpretation (in this case, the generic interpretation) is already available to the bare NP. In contrast, in Spanish, a bare NP can only be a predicate, and cannot appear in an argument position – hence the ungrammaticality of (2a) and the need for a definite article to express generic reference in (2b).Footnote 5 Dayal (Reference Dayal2004) disagrees with Chierchia's parametric approach (based on data from languages like German, which do not fit neatly into Chierchia's framework), but adopts Chierchia's basic semantic proposal, on which definite articles have different semantics in English vs. Romance.

Another proposal is that of Vergnaud and Zubizarreta (Reference Vergnaud and Zubizarreta1992), who place the differences between English and Romance articles in syntax rather than semantics. They propose that there are two definite determiners in Romance: one is an expletive element (a form with no semantic content), which is inserted with both plural generics and inalienable possession for syntactic reasons, while the other is non-expletive and used in other contexts, as in English. In contrast, English has only one definite determiner, the non-expletive one, which is why it is not used with either plural generics or inalienable possession. This proposal attempts to unify the generic reading of definite articles in Romance with the inalienable possession interpretation of definite articles, based on the contrasts presented in examples (1)–(4). Vergnaud and Zubizarreta's (Reference Vergnaud and Zubizarreta1992) proposal has been questioned on both conceptual and empirical grounds based on data from L1 acquisition (Baauw, Reference Baauw, Cremers and den Dikken1996, Reference Baauw2000). But because our study tests both the generic and inalienable possession interpretations of definite determiners in Spanish, it seems natural to adopt Vergnaud and Zubizarreta's proposal as our starting point. Under this proposal, if definite determiners are affected in Spanish under the influence of English and are used predominantly for specific rather than generic reference in Spanish heritage speakers, we should also find that definite articles may no longer be used in inalienable possession constructions in their Spanish. That is, under the influence of English, Spanish heritage speakers will no longer analyze the Spanish determiner as having the possibility of being expletive, as per Vergnaud and Zubizarreta's account. We will come back in the “Discussion” section to a comparison between Vergnaud and Zubizarreta's (Reference Vergnaud and Zubizarreta1992) and Chierchia's (Reference Chierchia1998) accounts in light of our experimental findings.

Previous studies

The acquisition of definite NP interpretation in English and Romance has been explored in both monolingual and bilingual child language acquisition, and in adult L2 acquisition, but has not been previously investigated in adult heritage speakers.

Pérez-Leroux, Munn, Schmitt and DeIrish (Reference Pérez-Leroux, Munn, Schmitt and DeIrish2004a) investigated the generic interpretation of plurals with definite articles in pre-school age monolingual English-speaking children and monolingual Spanish-speaking children. Pérez-Leroux et al. used a truth-value judgment task with stories and found that while the Spanish-speaking children correctly interpreted definite plurals as generic 80% of the time, the English-speaking children also incorrectly interpreted definite plurals as generic between 40% and 70% of the time, an option that is not possible in English (and that was not adopted by the native English adult controls). The English-speaking children appeared to temporarily entertain a Spanish-like grammar.

The acquisition of inalienable possession constructions has also been investigated in L1 acquisition of Spanish, English, and Dutch (Baauw, Reference Baauw, Cremers and den Dikken1996, Reference Baauw2000; Pérez-Leroux, Schmitt & Munn, Reference Pérez-Leroux, Schmitt, Munn, Bok-Bennema, Hollebrandse, Kampers-Manhe and Sleeman2004b). Baauw found that Dutch-speaking children incorrectly accepted sentences like (3)–(4) in Dutch with inalienable possession meanings of definite NPs, which is not possible in Dutch. Spanish-speaking children correctly accepted the inalienable interpretation of the same sentences in Spanish and tended to reject the alienable interpretation, which is also possible (but dispreferred) in Spanish. Pérez-Leroux et al. (Reference Pérez-Leroux, Schmitt, Munn, Bok-Bennema, Hollebrandse, Kampers-Manhe and Sleeman2004b) also found that English-speaking children had high rates of inalienable interpretation of definite NPs in object position in English. Like Baauw (Reference Baauw, Cremers and den Dikken1996, Reference Baauw2000), Pérez-Leroux et al. (Reference Pérez-Leroux, Schmitt, Munn, Bok-Bennema, Hollebrandse, Kampers-Manhe and Sleeman2004b) also found that Spanish-speaking children were quite accurate with the interpretation of inalienable possession in Spanish, although they showed different responses with plural and singular determiners and were also sensitive to verb classes.

Although the evidence is not conclusive, these studies suggest that the acquisition of generic reference and inalienable possession is not very problematic for Spanish-speaking children. Spanish-speaking children are overall target-like early on. However, English-speaking (and Dutch-speaking) children appear to go through a developmental “Spanish-like” or “Romance-like” stage during which they incorrectly accept definite determiners in the contexts of generic reference with plurals, and with inalienable possession, options that are not available in the adult English (or Dutch) grammar.

As for bilingual and L2 acquisition, cross-linguistic influence or transfer seems to be the main reason behind the developmental patterns observed in the acquisition of definite article interpretation. In a study of simultaneous bilingual acquisition, Serratrice et al. (Reference Serratrice, Sorace, Filiaci and Baldo2009) tested 6–10-year-old English–Italian bilingual children on their interpretation of plural NPs in both English and Italian, and compared their performance to that of age-matched English and Italian monolinguals and Spanish–Italian bilinguals (Spanish and Italian pattern identically with regard to interpretation of definite plurals as generic). Serratrice et al. used a Grammaticality Judgment Task (GJT) and found that monolingual Italian children were at ceiling at rejecting bare plurals with both generic and specific interpretation in Italian, and Spanish–Italian bilinguals were also largely accurate, although some of the younger bilinguals did incorrectly accept bare plurals to some degree. English–Italian bilinguals were non-native-like in accepting bare plurals with generic readings (bilinguals residing in the UK, with less input in Italian, also incorrectly accepted bare plurals with specific readings). Thus, this study found transfer effects from English into Italian. (The results of the English GJT were quite problematic, and it is not possible to tell whether influence from Italian to English was attested as well.)

Similar transfer effects from English into Spanish/Italian and from Spanish/Italian into English in the expression of generic reference have been recently reported in adult L2 acquisition as well: in Slabakova's (Reference Slabakova2006) study of bare plurals in L2 Italian and L2 English; and in Ionin, Montrul and Crivos's (Reference Ionin, Montrul and Crivos2009) study of definite plurals in generic contexts in L2 Spanish and L2 English. Finally, Pérez-Leroux, O'Rourke, Lord and Centeno Cortés's (Reference Pérez-Leroux, Lord, O'Rourke, Centeno Cortés, Pérez-Leroux and Liceras2002) study of different inalienable possession constructions in L2 Spanish of adult English-speaking learners suggests that beginner learners have difficulty distinguishing overt possessors and definite determiners in these constructions but by the intermediate level, learners are able to acquire this difference. In conclusion, for bilingual acquisition and adult L2 acquisition, transfer from the dominant language seems to underlie the development of these bilingual and interlanguage systems.

To our knowledge, the expression of generic reference or inalienable possession has not been investigated in adult Spanish heritage speakers. However, Lipski (Reference Lipski, Roca and Lipski1993, p. 162) notes that “these speakers frequently employ articles in fashions which deviate significantly from usage among fluent native Spanish speakers, but which are at times found among foreign language learners”. Two examples from Lispki (Reference Lipski, Roca and Lipski1993, p. 162, ex. (3)) are shown in (7) and (8). These examples suggest that Spanish heritage speakers are allowing English-like distribution of bare nouns in Spanish.

(7) *Tengo miedo de exámenes. (los exámenes)

“I'm afraid of exams.”

(8) *Me gusta clases como pa escribir. (las clases)

“I like classes to learn to write.”

Since both Spanish and English have articles, and articles are learned by age 3 or 4, Spanish heritage speakers are assumed to have acquired the form and basic meaning (definite/indefinite) of Spanish articles. But due to reduced input in childhood they may have not completely acquired the specific semantics (i.e., generic and inalienable possession meanings) of definite articles in Spanish, unlike monolingual children who, according to the studies reviewed in this section, are quite accurate early on. If that is the case, reduced Spanish input and use may facilitate transfer from English. Hence, our research question is whether as adults Spanish heritage speakers interpret articles in a fully target-like manner in those contexts where Spanish and English differ. Although the issue of transfer has not received much attention in heritage language development so far, we contend that together with reduced language use and input conditions, it also plays a crucial role in shaping heritage language grammars (see also O'Grady et al., Reference O'Grady, Lee and Lee2008).

In a bilingual situation, the two languages are likely to influence each other (Seliger, Reference Seliger, Ritchie and Bhatia1996). However, we ask whether transfer is more likely or more pronounced from the stronger language to the weaker language than the reverse. If English is psycholinguistically and functionally stronger than Spanish, Spanish heritage speakers may exhibit transfer effects from English into Spanish in the syntactic and semantic distribution of definite articles, especially in cases where the two languages differ. Specifically, we expect to find incorrect acceptance of bare plural subjects in generic contexts in Spanish (see examples (7) and (8) above), as well as a predominantly specific interpretation of definite plurals as opposed to the generic interpretation also available in Spanish. And although both possessive and definite determiners can express inalienable possession in Spanish, we expect heritage speakers to prefer the use of possessive pronouns for inalienable possession and definite articles for alienable possession, like English native speakers.

Method

In order to test our prediction – that the stronger language (English) will encroach into the semantic domains of the weaker language (Spanish) – we conducted two studies (one in English and one in Spanish) comprising a total of six tasks (three tasks in each language) testing knowledge and interpretation of the syntactic and semantic properties of definite articles in Spanish and English.

Participants: Background and proficiency

The same Spanish heritage speakers participated in the two studies. The heritage speaker group consisted of 23 adult Spanish heritage speakers (Spanish–English simultaneous bilinguals, 16 female and 7 male; mean age 21, range 18–28) who were students at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.Footnote 6 Most of them were taking Spanish-language classes and were exposed to speakers from different Spanish-speaking varieties in the classroom. Eighteen of the heritage speakers (78%) were born in the United States and the rest were born in Mexico and immigrated in early childhood. In 85% of the cases, both parents were from Mexico; in the other cases one parent was from Mexico and the other from Colombia, Honduras, Argentina, or Ecuador. The vast majority of the heritage speakers (21 of 23, or 91%) came from working class families (as indicated by reported parents’ occupation), while in only two cases the parents were professionals. In 60% of the cases, Spanish was spoken at home whereas the rest reported speaking both Spanish and English. When asked which their native language was, 16 (70%) responded Spanish, 5 (22%) responded English, and 2 responded both languages (8%). Fifteen (65%) of the heritage speakers were exclusively schooled in English since elementary school, while 8 (35%) received some elementary schooling in Spanish temporarily or in a transitional bilingual program (whose main objective is assimilation to mainstream education in English). All heritage speakers have visited their Spanish-speaking country of origin. At the time of testing, except for one participant, they all reported using English and Spanish. The mean use of Spanish on a daily basis was 29.12% (range 10–90%) and the mean use of English was 70.86% (range 10–90%). Fifty-five percent of the heritage speakers reported that English was their dominant language, 25% indicated that both languages were equally dominant, while the remaining 20% indicated that language dominance depended on the situation. Their mean self assessment in Spanish was 4.39 (range 3–5, where 1 = low proficiency and 5 = native-like), while their mean self assessed proficiency in English was 4.77 (range 4–5).

The comparison group for the Spanish study consisted of 17 fully fluent monolingually-raised Spanish speakers (mean age 31). Eight of them were tested in Argentina. The remaining nine were tested in the U.S., where they were students and/or instructors of Spanish at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. They had all moved to the U.S. as adults, from a variety of Spanish-speaking countries, including Mexico, Spain, Argentina, and Puerto Rico. The phenomena we are investigating are the same in all varieties of Spanish, and the individual performance of all the native speakers was quite target-like in all tasks.

The comparison group for the English study consisted of 19 monolingual American English speakers (mean age 21), who were students at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

All heritage speakers and Spanish monolingual participants were asked to complete a Spanish proficiency test, consisting of a cloze passage (with three multiple-choice response options for each blank) from a version of the Diploma de Español como Lengua Extranjera (DELE) and a multiple choice vocabulary part from an MLA [Modern Language Association] placement test. The maximum possible score on the proficiency test (both sections combined) was 50. The same test was used in Montrul and Bowles (Reference Montrul and Bowles2009) and Montrul et al. (Reference Montrul, Foote and Perpiñán2008). The Cronbach alpha for this cloze test was .827, indicating reliability. On this proficiency test, scores between 80–100% are considered advanced (native speakers typically score above 90%); scores between 60–79% are intermediate, and scores of 59% and below are low.

To assess whether the Spanish skills of the heritage speakers were weaker in Spanish than in English, their dominant language according to many of the bilinguals tested, all the bilinguals and the 19 monolingual English speakers were tested in English as well. The English proficiency test consisted of a cloze passage with a blank for every seventh word (total 40 blanks), and participants were to select one of three choices for each blank.Footnote 7 The same test was used in Ionin and Montrul (Reference Ionin, Montrul, García-Mayo and Hawkins2009, Reference Ionin and Montrul2010). The Cronbach alpha for this cloze test was .817, indicating that the test is reliable.

To allow comparisons between the Spanish and the English proficiency measures used, raw scores were converted into percentage accuracy. The boxplots in Figure 1 (English proficiency test) and Figure 2 (Spanish proficiency test) present the proficiency distribution of the heritage speakers in each language. Descriptive statistics appear in Table A in the Appendix.

Figure 1. Mean accuracy and distribution on English cloze test (proficiency measure).

Figure 2. Mean accuracy and distribution on Spanish cloze and vocabulary test (proficiency measure).

The Spanish heritage speakers’ mean percentage accuracy score in the English proficiency test (92.2%) differed marginally from that of the English native speakers (94.3%) (t(40) = 1.93, p = .06). But in the Spanish proficiency test, the heritage speakers fell into the intermediate-to-advanced range (scores of 32–48 out of 50), and scored significantly lower than the Spanish native speakers (81.3% vs. 96.8%, t(42) = 6.76, p < .01, equal variances not assumed), and lower than their own mean score in English (t(22) = 5.45, p < .01). We now examine whether these differences between proficiency in Spanish and English are also observable in other linguistic tasks.

Tasks and procedure

In addition to the proficiency measures in both languages, the study included three experimental tasks in each of the two languages: an Acceptability Judgment Task (AJT) used as a baseline measure to estimate the bilinguals’ overall knowledge of English/Spanish articles, a Truth-value Judgment Task (TVJT) examining interpretation of English/Spanish plurals as generic vs. specific, and a Picture–Sentence Matching Task (PSMT) testing the interpretation of inalienable and alienable possession with definite articles and possessive determiners in English/Spanish.

All tasks, as well as a language background questionnaire, were administered through a web interface. Participants were tested individually in the presence of a research assistant. They entered their responses on the computer screen, and the responses were automatically recorded in a database.

The administration of the Spanish proficiency test and of the Spanish experimental tasks took place in a session conducted entirely in Spanish, while the administration of the English proficiency test and of the English experimental tasks took place entirely in English. Some heritage speakers took the Spanish version of the tests first (N = 8), while the others took the English version first. A week or two weeks, depending on the subject availability, elapsed between the two testing sessions of the heritage speakers. Background questionnaires in the language of the session were also administered in the Spanish and English sessions. In this way, efforts were made to conduct the Spanish part in Spanish mode and the English part in English mode (Grosjean, Reference Grosjean1998). All tests were untimed. Total testing time was about an hour in each language.

Acceptability Judgment Task

The AJT was designed to test basic familiarity with articles in English and Spanish, and thus provide a baseline measure of the heritage speakers’ overall article knowledge. To test the grammaticality of articles in discourse, the AJT consisted of pairs of sentences, and participants were asked to evaluate the second sentence as either acceptable or unacceptable in the context of the first sentence, choosing YES or NO in the English version, SI or NO in the Spanish version. If participants chose the NO response, they were asked to provide a correction. The AJT contained 72 sentence pairs, half designed to be acceptable, and half unacceptable, targets as well as fillers.

Of the 72 test items, 32 target items (16 acceptable and 16 unacceptable) were designed to test basic article usage in English and Spanish, including the requirement that a definite article be used on second mention ((9a) vs. (9b)) and the impossibility of a bare singular count noun ((9c) vs. (9d)). (The target DP is in bold in the examples for ease of reference; it was not in bold in the actual test.) Both singular and plural count nouns, and both definite and indefinite uses were tested; the Spanish items were similar to the English items in structure, as in (10), with minor variations designed to make the sentences sound natural.Footnote 8 Those items designed to be acceptable in the English version were also designed to be acceptable in the Spanish version, and those designed to be unacceptable in the English version were designed to be unacceptable in the Spanish version. Therefore, the heritage speakers were expected to perform at ceiling with sentences (9) and (10) in their two languages since the discourse-syntactic distribution of definite and indefinite articles is the same in the two languages in these sentences.

- (9)

a. Mary has a cat. The cat is named Steve.

b. Robin owns a dog. *A dog is named Rollo.

c. Sue looked out the window. A lion was standing in her garden.

d. Louis has a kitten. *Kitten is named Sheila.

- (10)

a. María tiene un gato. El gato se llama Ben.

b. Rosa tiene un perro. *Un perro se llama Polo.

c. Susi miró por la ventana. Un tigre estaba en su jardín.

d. Luisa tiene un gatito. *Gatito se llama Michi.

There was another test category, generic bare plural subjects, in which bare plurals were used generically, as in (11) and (12):

(11) Roger's cat doesn't listen to him. Cats are very independent.

(12) El gato de Roger no le hace caso. *Gatos son muy independientes.

This was the only target category in the test in which the target English and Spanish judgments are different, since generic bare plurals are grammatical in English but ungrammatical in Spanish. With these sentences, heritage speakers are expected to be native-like in English but non-native-like in Spanish: they are expected to incorrectly accept ungrammatical sentences like (12) in Spanish, with bare plural NP subjects, due to transfer from English. As a result, we will compare performance on this category separately from overall performance on the other AJT categories in each language.

Truth-value Judgment Task

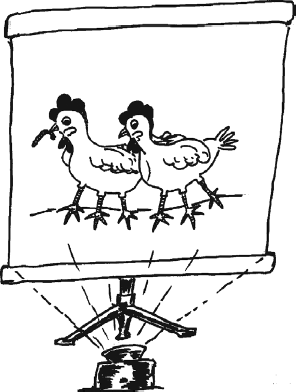

In order to investigate the Spanish heritage speakers’ interpretation of plural NPs in English and in Spanish, we designed a Truth-value Judgment Task (TVJT), whose format was loosely modeled on the task used by Pérez-Leroux et al. (Reference Pérez-Leroux, Munn, Schmitt and DeIrish2004a) with child L1-learners, but with a number of changes (including written rather than oral format). Each TVJT item consisted of a story accompanied by a picture and followed by a test sentence. The participants had to judge the test sentence as true or false in the context of the story. As in Pérez-Leroux et al.'s (Reference Pérez-Leroux, Munn, Schmitt and DeIrish2004a) task, each test story juxtaposed a specific reading with a generic reading, by describing animals that bear a characteristic unexpected for their species. Sample stories from the English study are given in (13) and (14), and the corresponding stories from the Spanish study are given in (15) and (16). There was a total of eight target stories, and each appeared three times in the test, each time with a different target sentence.

In the English TVJT, each story appeared once with a target sentence containing a bare plural, which has a generic reading ((13a), (14a)); once with a target sentence containing a definite plural, which has a specific reading ((13b), (14b)); and once with a target sentence containing a demonstrative plural ((13c), (14c)). The demonstrative plural was a control item, since the specific reading is the only possible interpretation for it in Spanish as well as English. Target truth-values were counterbalanced across items. For the item in (13), the sentences with bare and definite plurals, (13a–b), are designed to be true, while the sentence with a demonstrative plural, (13c), is designed to be false. This was the case for half of the target items, while for the other half, the sentences with bare and definite plurals were false, and the sentences with demonstrative plurals were true, as shown by the sample item in (14).

(13) Sample picture with test story: English TVJT

Everyone knows that a zebra always has stripes. But not in our zoo! Our zoo has two zebras, and they are really unusual: they have spots instead of stripes! That's really strange.

a. Zebras have stripes. → TRUE

b. The zebras have spots. → TRUE

c. These zebras have stripes. → FALSE

(14) Sample picture with test story: English TVJT

Last night, I saw a movie about two very strange chickens. They have three legs, instead of two! That's so weird. Everyone knows that a chicken normally has two legs!

a. Chickens have three legs. → FALSE

b. The chickens have two legs. → FALSE

c. These chickens have three legs. → TRUE

In the Spanish TVJT, the set-up is somewhat different. Since a bare plural in preverbal position is ungrammatical in Spanish, it was not possible to test target sentences analogous to (13a): participants cannot be asked to judge an ungrammatical sentence as true or false. Instead, each target item appeared once with a test sentence containing a definite plural, and designed to be true on the specific (spec.) reading and false on the generic (gen.) reading ((15a), (16a)); once with a test sentence containing a definite plural, and designed to be false on the specific reading and true on the generic reading ((15b), (16b)); and once with a test sentence containing a demonstrative plural ((15c), (16c)). Half of the demonstrative plural sentences were designed to be false on the specific reading, as in (15c), and half were designed to be true, as in (16c).

(15) Sample picture with test story: Spanish TVJT

El zoológico de Buenos Aires tiene dos cebras nuevas. Estas cebras no son comunes: tienen manchas en vez de rayas. ¡Son muy extrañas!

(16) Sample picture with test story: Spanish TVJT

Ayer vi una película sobre dos gallinas muy extrañas. En vez de dos patas, las gallinas tenían tres patas. Eran muy raras.

Thus, there was a total of 24 test items: in the English test version, 8 contained bare plurals, 8 contained definite plurals, and 8 contained demonstrative plurals, while in the Spanish test version, 16 items contained definite plurals and 8 contained demonstrative plurals. There were also 36 filler items in each test version, for 60 items total. The fillers consisted of stories juxtaposing either two different aspectual interpretations or two different temporal interpretations. All filler items had proper personal names or NPs with possessive pronouns in subject position, to avoid a focus on the presence vs. absence of articles. If heritage speakers have weaker command of Spanish than of English, we expect to find that they will be quite accurate with the interpretation of the definite plurals in the English TVJT but more inaccurate in the Spanish TVJT. In particular, they would allow more specific than generic interpretations of definite plurals compared to native Spanish speakers, imposing the English pattern.

Picture–Sentence Matching Task

A Picture–Sentence Matching Task (PSMT) in English and one in Spanish were designed to test the interpretation of definite and possessive determiners in alienable and inalienable possession contexts.Footnote 9 Each test item consisted of two pictures, A and B, presented side by side with only one sentence underneath. Participants were instructed to read the sentence and decide whether it described picture A, picture B, or both pictures, by circling one of the three options, as in (17) for English and (18) for Spanish. (The same pictures were used in the two versions.)

Sample pictures used in the two versions of the PSMT

Sample sentences in the English PSMT

(17)

Sample sentences in the Spanish PSMT

(18)

In the English version, the target response for sentences like (17a) with definite determiners was B, the alienable possession interpretation; the target response for (17b) with the possessive determiner was A, the inalienable interpretation. No Both responses were expected in English.Footnote 10

In Spanish, by contrast, both definite and possessive determiners are grammatical with an inalienable possession interpretation. Hence, either A or Both was the expected response for sentence (18a) with the definite determiner, whereas either B or Both was the expected response for sentence (18b) with the possessive. What we wanted to find out is whether the Spanish heritage speakers would match the English sentence (17a) to A or Both, as in Spanish, or whether they would match the Spanish sentence (18a) only to B, as in English.

The English PSMT included a total of 40 pairs of pictures and sentences. There were 8 sentences with body parts, 4 plural (eyes, feet, fingers, tongues) and 4 singular (hand, leg, head, mouth). Each body part sentence appeared once with a definite determiner and once with a possessive determiner. Hence, there was a total of 16 target items. The remaining 24 items were all fillers and included plural and singular objects of possession (cars, dogs, kittens, etc.), presented with possessives and definite or indefinite articles; other filler sentences and pictures tested interpretation of pronouns and anaphors (e.g., him vs. himself). The Spanish PSMT included a total of 38 sentences. It was identical in format to the English PSMT, except that two sentences with plural body parts and possessives were eliminated because they sounded awkward and were hard to judge.Footnote 11

If heritage speakers have weaker command of Spanish than of English, we expect them to perform like the English native speakers in the English PSMT but we expect them to perform unlike native speakers in the Spanish PSMT. Specifically, we expect them to show a tendency to interpret definite determiners as corresponding to alienable possession and possessive determiners as predominantly corresponding to inalienable possession, following the tendencies of English.

Results

The Spanish and English AJTs

Before submitting the responses to statistical analysis, we checked the scores and the corrections provided by the participants. We first looked at whether the participant had entered YES (grammatical) or NO (ungrammatical) for each item. Second, if the participant entered NO, we checked whether the participant provided the expected correction. If the target response was YES (as in (9a, c) and (10a, c)), then the response was scored as “appropriate” if the participant either chose YES or chose NO but corrected a part of the sentence that had nothing to do with the interpretation of the subject NP (e.g., changed was standing to stood in (9c)); if the participant corrected the form of the subject NP (which was already grammatical), the response was scored as “inappropriate”. On the other hand, if the target response was NO (as in (9b, d) and (10b, d)), then a response was scored as “appropriate” if the participant assigned NO and provided an appropriate correction; if the correction had nothing to do with the subject NP, if there was no correction at all, or if the subject chose YES, then the response was scored as “inappropriate.”

The mean scores (converted to percentages) for test categories illustrated in (9) in the English AJT and (10) in Spanish AJT were computed separately from the scores for bare plural subjects as in (11) and (12). The categories in (9) and (10) tested basic usage of definite and indefinite articles in discourse, which is the same in the two languages. The categories in (11) and (12) tested the acceptability of bare plurals in subject position, which are grammatical in English but ungrammatical in Spanish. If Spanish heritage speakers know that bare plural subjects are grammatical in English and transfer their generic interpretation onto Spanish, we expect Spanish heritage speakers to incorrectly accept bare plural subject NPs in Spanish.

The results of the English AJT showed that the heritage speakers were quite accurate in English, scoring above 90% accuracy like the native English speakers. (Descriptive statistics are presented in Table B in the Appendix.) To confirm that the proficiency test used reliably captures the proficiency of the heritage speakers, we ran a correlation between the results of the cloze test and the overall scores on the AJT including all sentences in (9), (10) and (11) for the English native speakers and the Spanish heritage speakers. Although most participants scored above 90%, there was a positive relationship between the scores on the English cloze test and overall mean percentage accuracy on the English AJT. Pearson correlations (two-tailed) were r = .57, p = .01 for the English native speakers, and r = . 59, p = .003 for the Spanish heritage speakers. Figure 3 presents the results of accuracy on general use of articles in discourse (the main conditions tested, illustrated in examples (9) and (10)). Since English and Spanish are very similar, the heritage speakers were expected to perform at ceiling, and they did. However, the statistical analysis comparing the English native speakers and the Spanish heritage speakers on all these sentences with definite and indefinite articles in English indicated a significant difference (t(40) = 2.33, p = .02). This may be due to the fact that there was more variability in the bilingual group than in the English native speaker group as judged by the standard deviations. As for bare plural NPs (grammatical in English but ungrammatical in Spanish), there were no differences between the native speakers and the Spanish heritage speakers (t(34.51) = 0.2, p = .84, equal variances not assumed) (see Table B in Appendix), suggesting that heritage speakers know that bare plural NPs can be subjects in English.

Figure 3. Mean percentage accuracy on English Acceptability Judgment Task (AJT) (general article use).

For the Spanish heritage speakers there was a positive and significant correlation between the scores of the Spanish proficiency measure and mean accuracy on the Spanish AJT, r = .55, p = .006, suggesting that the proficiency test used with the heritage speakers is reliable; for the Spanish native speakers the correlation was nonsignificant (r = −.09).

The results of the Spanish AJT showed that the Spanish heritage speakers were quite accurate on overall knowledge of articles in discourse (Figure 4), although their score (86%) was lower than that of the Spanish native speakers (91%) but not statistically different from them (t(38) = 1.6, p = .16), and lower than their own score in the English AJT (91.6%) on the same sentences. However, the results for the category of bare plurals in Spanish presented in Figure 5 suggest that the heritage speakers incorrectly accepted ungrammatical bare plurals with generic reference in Spanish, confirming our hypothesis of transfer from English onto Spanish. The difference between the native Spanish speakers’ (99%) and the Spanish heritage speakers’ (50%) scores on bare plurals was highly significant (t(23.52) = 6.07, p < .01, equal variances not assumed). At the individual level, 15 of the 23 heritage speakers (65%) scored below between 0% and 50% accuracy with ungrammatical bare plurals in Spanish. There was a significant correlation between accuracy on bare plurals and proficiency scores for the heritage speakers (r = .486, p < .01).

Figure 4. Mean percentage accuracy on Spanish Acceptability Judgment Task (AJT) (general article use).

Figure 5. Mean percentage accuracy on Spanish Acceptability Judgment Task (AJT) (ungrammatical bare plural NPs).

The Spanish and English TVJTs

We now turn to the interpretation of plural NPs in generic and specific contexts in the two languages, as measured by the TVJTs. Recall that in the TVJT, participants evaluated each sentence as true or false in the context; since the specific and generic readings are juxtaposed in the context, participants’ responses give us an indication of whether they interpret the subject NP specifically or generically. We scored each response as either target or non-target, as follows: For sentences with bare plurals in the English TVJT, the target response is one that indicates the generic reading: in (13a), the response of true indicates the target generic reading, whereas in (14a), the target response is false. For definite and demonstrative plurals, the target response is one that indicates the specific reading: true in (13b) and (14c), false in (13c) and (14b). Since there were eight items in each category, the maximum possible number of target responses in each category for each participant was eight. We converted the raw scores into % target for each category. For the English TVJT, working with percentages vs. raw scores makes no difference, since the number of items was equal across categories.

In contrast, in the Spanish TVJT, the number of items was unequal across categories, which warranted conversion into percentages for comparability. The design of the Spanish TVJT was somewhat different from that of the English TVJT: recall that there were no items with bare plurals in the Spanish TVJT, and therefore twice as many items with definite plurals. Once again, we scored each response in terms of whether it was target-like. For demonstrative plurals, the target response is one that indicates the specific reading (e.g., false in (15c) but true in (16c)). For definite plurals, both specific and generic interpretations are in principle possible. However, as shown in Table C in the Appendix and in Figure 7, we found that native speakers overwhelmingly preferred the generic interpretation of definite plurals; we therefore scored each response on definite plurals as target-like if it indicated the generic interpretation (true in (15a) and (16a), false in (15b) and (16b)), and non-target-like if it indicated the specific interpretation.Footnote 12 Due to the different number of items per category, the maximum score for definite plurals was 16, while the maximum score for demonstrative plurals was 8. In order to allow comparison between these two categories, we converted the raw scores into percentages for both categories. For uniformity of presentation, we use percentages rather than raw scores in both studies.

The results of the English TVJT appear in Figure 6; descriptive statistics can be found in Table C in the Appendix. The results showed that both Spanish heritage speakers and English native speakers were fairly accurate on bare plurals as well as demonstrative plurals, while performance on definite plurals was a bit lower. We conducted a repeated-measures ANOVA on the results, with NP type (bare, definite, or demonstrative) and target truth-value (true vs. false) as the within-subjects variables, and group as the between-subjects variable. There was no significant effect of NP type (bare plural, definite, or demonstrative) (F(1.37, 55.1) = 2.27, p = .096, Greenhouse-Geiser correction for violation of sphericity). There was no effect of target truth-value (F(1,40) = 0.68, p = .41), which indicates that there was no truth-bias in the participants’ responses. There was no significant main effect for group (F(1,40) = 0.55, p = .81), nor a significant group by NP type interaction (F(1.37, 55.1) = 7.3, p = .77, Greenhouse-Geiser correction for violation of sphericity). Like the English native speakers, the Spanish heritage speakers interpreted bare plural subjects as generic in English and they assigned specific reference to plural NPs with definite determiners.

Figure 6. English Truth-value Judgment Task (TVJT). Mean percentage target interpretation of plural NPs (bare NPs: target generic, definites and demonstratives: target specific).

Figure 7 shows the results of the Spanish TVJT (see Table C in the Appendix for the descriptive statistics). Recall that in this task we have only two categories: definite plurals and demonstrative plurals, since bare plural NP subjects are not possible in Spanish. Both the Spanish native speakers and the Spanish heritage speakers performed at ceiling on demonstrative plurals (95.6% accuracy in both cases). Importantly, while the native Spanish speakers showed a strong preference for the generic readings of definite plurals (81.2%), the Spanish heritage speakers chose the generic reading of definite plurals only about half the time (56.7%), indicating clear transfer effects from English.

Figure 7. Spanish Truth-value Judgment Task (TVJT). Mean percentage target interpretation of plural NPs (demonstratives: target specific, definites: target generic).

We conducted a repeated-measures ANOVA on the results, with NP type (definite vs. demonstrative) and target truth-value (true vs. false) as the within-subjects variables, and group as the between-subjects variable. There was a significant effect of NP type (F(1,38) = 14.8, p < .001), but no effect of target truth-value (F(1,38) = 1.68, p = .202), which indicates that there was no truth-bias in the participants’ responses. There was a marginally significant effect of group (F(1,38) = 3.56, p < .07) and a significant group by NP type interaction (F(1,38) = 4.42, p = .04). There were no other significant interactions.

In order to explore the interaction between NP type and group in more detail, we conducted separate independent samples t-tests, with group as the between-subjects variable, and with the alpha significance level set at .025 (Bonferroni correction for multiple familywise comparisons). The t-test for definite plural interpretation showed that there was a marginally significant difference between the Spanish native speakers and the Spanish heritage speakers (t(37.74) = 2.08, p = .04, equal variances not assumed), but the t-test for demonstrative plurals did not find a significant difference (t(38) = 0.27, p = .97).

To look deeper into the results, we conducted an individual subjects’ analysis on the Spanish TVJT data, grouping subjects into three patterns: generic, specific and mixed, as described in (19).Footnote 13

- (19)

a. The generic pattern: definite plurals interpreted as generic at least 75% of the time.

b. The specific pattern: definite plurals interpreted as specific at least 75% of the time.

c. The mixed pattern: definite plurals interpreted as generic more than 25% of the time, and as specific more than 25% of the time.

The results of the individual subjects’ analysis are given in Table 1. This Table 1 shows that there is variability among the Spanish native speakers, with one native speaker showing the “specific” pattern and two allowing both specific and generic readings (the “mixed” pattern); however, the majority of the native speakers (14 of 17 or 76%) are in the “generic” pattern, as expected. More variability is evident in the Spanish heritage speaker group. Only 47% (11/23) were in the generic pattern. The remaining 12 (53%) were split between the specific “English” pattern (7 individuals) and the mixed pattern (5 individuals).Footnote 14

Table 1. Spanish TVJT: individual subjects’ patterns of responses.

a In terms of type of speaker, a valid question is what kind of grammar the “mixed” pattern exemplifies. We found that only one heritage speaker in the “mixed” pattern has a clear truth-bias, in most instances picking the response that makes the sentence true, regardless of whether it is generic or specific. The other four heritage speakers and the one native speaker were not affected by a truth-bias. We believe that the native speaker clearly allows both the generic and specific options, but unlike the other thirteen and two native speakers falling in the generic and specific patterns, respectively, the “mixed” native speaker does not exhibit a preference one way or the other. The same explanation holds for the heritage speakers in the “mixed” pattern. We believe that the heritage speakers in this pattern, like those in the “generic” pattern, are exhibiting an awareness that generic readings of definites are allowed in Spanish. Importantly, we note that the mixed pattern is not a random pattern: it is not a case of learners simply not understanding the test items and responding randomly, because the same randomness did not show up with demonstratives. All subjects consistently interpreted demonstratives as specific.

Comparing the results of the English and Spanish TVJTs, we see significantly more variability in the Spanish TVJT than in the English TVJT, in line with the greater variability among the Spanish native speakers. Still, the variability is even greater in the Spanish heritage speaker group. Some subjects have clearly adopted the English-like interpretation of Spanish definite articles.Footnote 15

The Spanish and English PSMTs

If the generic interpretation and the inalienable possession interpretation of definite determiners in Spanish are related, as per Vergnaud and Zubizarreta's analysis, then we expect to find that heritage speakers also impose the “English” interpretation of articles in inalienable possession constructions. That is, they should consider that Spanish articles, like English articles, are obligatorily non-expletive, and hence incompatible with inalienable possession constructions as well as with generic reference. As a result, the heritage speakers should take the definite determiner to indicate that the possessed element belongs to somebody else, not to the referent of the subject.

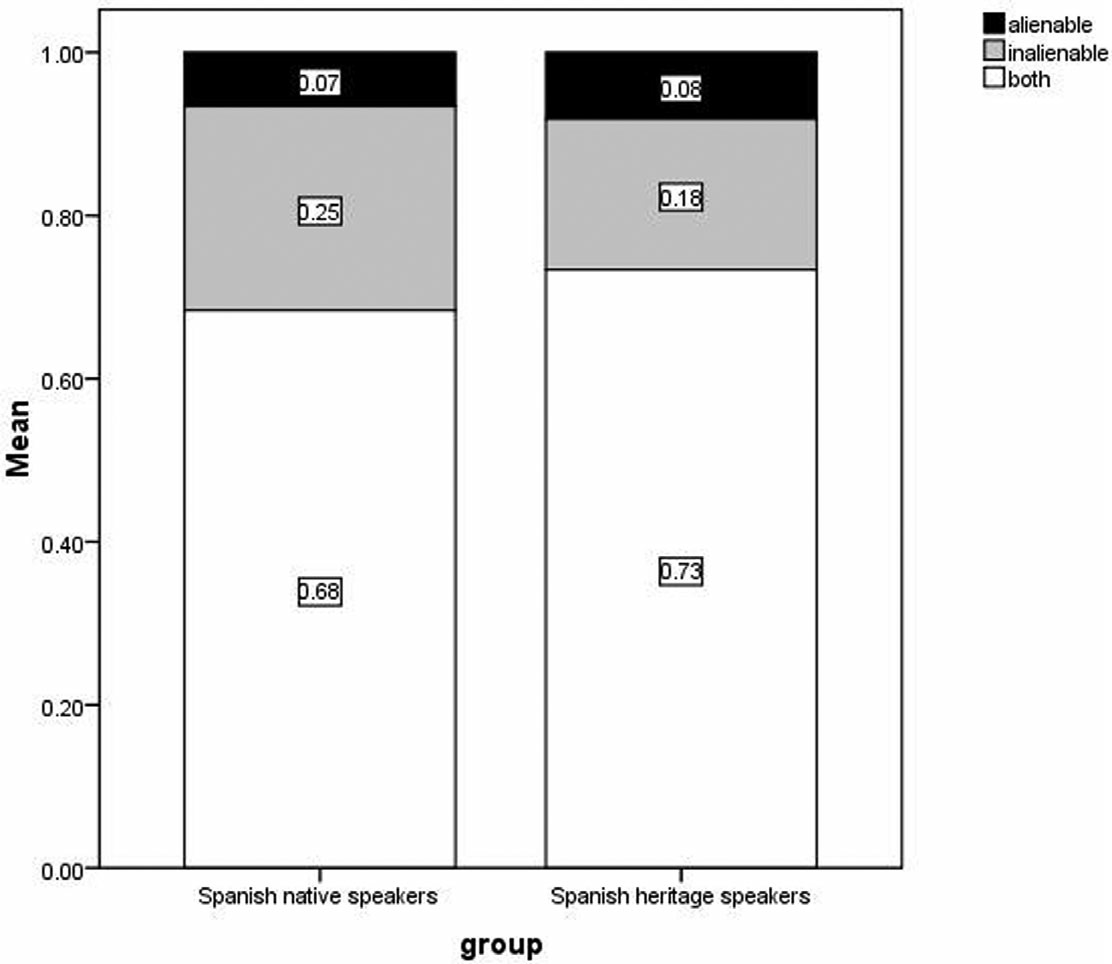

In the English PSMT, the target is for sentences with determiners to be matched to alienable possession pictures (the body part belongs to somebody else), whereas sentences with possessive determiners should be matched with pictures representing inalienable possession. In the Spanish PSMT, both possessives and determiners can potentially express alienable or inalienable possession, so both pictures were in principle acceptable. Still, we wanted to see whether the Spanish native speakers and the Spanish heritage speakers had the same preferences and interpretations. In both the Spanish and the English PSMTs, we coded the sentences to keep track of the proportions of alienable, inalienable or “both” responses; we calculated percentages of the types of interpretation (alienable, inalienable or both) for NPs with definite articles and for NPs with possessive determiners. Descriptive statistics for sentences with definite determiners are presented in Table D in the Appendix; those for sentences with possessive determiners are in Table E.

Figure 8 presents the proportions of alienable, inalienable or both interpretations for sentences with definite articles in the English PSMT. Both English native speakers and Spanish heritage speakers overwhelmingly interpreted definite articles as indicating alienable possession: the English native speakers chose the picture with alienable possession (e.g., a boy holding a plastic hand) 95.4% of the time and the Spanish heritage speakers did so 81.6% of the time. Independent samples t-tests comparing the two groups showed no statistical difference between the English native speakers and the Spanish heritage speakers for any of the interpretations: alienable (t(40) = 1.8, p = .07), inalienable (t(40) = 0.9, p = .33), both (t(40) = 1.8, p = 0.08). Figure 9 presents the results for sentences with possessive determiners, which by default have an inalienable interpretation in English. As with the results of definite determiners, there were no statistical differences between the English native speakers and the Spanish heritage speakers on any of the interpretations with possessive determiners either: alienable (t(40) = 0.13, p = .89), inalienable (t(40) = 1.28, p = .208), both (t(40) = 1.05, p = .29). Thus, the Spanish heritage speakers converged on the interpretations of the English native speakers with definite and possessive determiners in inalienable possession constructions in English, their stronger language.

Figure 8. English Picture–Sentence Matching Task (PSMT). Mean match frequency between sentences with definite articles and pictures expressing alienable vs. inalienable possession.

Figure 9. English Picture–Sentence Matching Task (PSMT). Mean match frequency between sentences with possessive determiners and pictures expressing alienable vs. inalienable possession.

But how do heritage speakers fare in Spanish, their weaker language? In the Spanish PSMT, the results for definite determiners are very different from the trends seen in English, as shown in Figure 10: both Spanish native speakers and Spanish heritage speakers overwhelmingly chose Both as their response, i.e., they allowed both alienable and inalienable interpretations for sentences with definite articles (68.4% Spanish native speakers and 74% Spanish heritage speakers), but the inalienable possession response was the second most frequent choice (25% and 17.3%). Independent samples t-tests comparing the two groups showed no statistical differences between the Spanish native speakers and the Spanish heritage speakers for any of the interpretations: alienable possession (t(38) = 0.35, p = .72), inalienable possession (t(38) = 0.86, p = .39), both (t(38) = 0.51, p = .61). Finally, Figure 11 presents the results for sentences with possessive determiners, which can be associated with an alienable possession interpretation in Spanish, although as Figure 11 shows, many speakers also chose the Both interpretation. As with definite determiners, there were no statistical differences between the Spanish native speakers and the Spanish heritage speakers on any of the interpretations of possessive determiners: alienable possession (t(38) = 0.69, p = .49), inalienable possession (t(38) = 0.05, p = .95), both (t(38) = 0.60, p = .54). We therefore say that the Spanish heritage speakers also converged on the interpretations of the Spanish native speakers with definite articles and possessive determiners in inalienable possession constructions in Spanish, their weaker language.

Figure 10. Spanish Picture–Sentence Matching Task (PSMT). Mean match frequency between sentences with definite articles and pictures expressing alienable vs. inalienable possession.

Figure 11. Spanish Picture–Sentence Matching Task (PSMT). Mean match frequency between sentences with possessive determiners and pictures expressing alienable vs. inalienable possession.

In conclusion, there are differences in the interpretations of sentences with definite articles and possessive determiners in inalienable possession constructions in English and Spanish. Yet, we observed no transfer from English (the stronger language) in the Spanish heritage speakers on this task. The heritage speakers were no different from the English native speakers in the English PSMT or from the Spanish native speakers in the Spanish PSMT.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the linguistic competence of Spanish heritage speakers in the domain of the interpretation of definite articles in Spanish and English. More specifically, under the assumption that the minority language (Spanish) is typically psycholinguistically weaker than the majority language (English) in this population, and at least in the particular group reported in this study, we investigated the potential role of transfer at the morphosyntactic and semantic levels. A previous study by Montrul (Reference Montrul2006) on the lexical-semantic and syntactic properties of unaccusativity (the distribution of two classes of intransitive verbs) also looked at a group of Spanish heritage speakers in English and Spanish. Montrul found that despite some differences in accuracy and ratings of individual verbs, the heritage speakers were quite balanced and native-like in the two languages when compared to the monolingual control group in each language. Proficiency differences between the heritage speakers and the two native speaker control groups attested in the proficiency tests and with self-ratings did not correlate with similar differences in the linguistic tasks testing unaccusativity in each language. Montrul concluded that a universal phenomenon like unaccusativity, which develops early in language acquisition, might not be prone to incomplete acquisition or transfer in unbalanced bilingual grammars. Furthermore, the syntactic manifestations of unaccusativity are language specific and very different in Spanish and English. For example, constructions like resultatives (The bag broke open) and pseudopassives (This hall has been lectured in by three Nobel laureates), typical unaccusativity diagnostics in English, are not possible in Spanish. Nor are absolutive constructions (*Landed the plane, the crew opened the door) or postverbal subjects (*Left Paul), typical unaccusativity diagnostics of Spanish, available in English. Thus, transfer from one language to the other is less likely because there is not much perceivable overlap in this domain.

But in the case of the morphosyntax and semantics of definite articles, Spanish and English have more in common than in the case of unaccusativity. Following a similar research design as Montrul (Reference Montrul2006) – a group of Spanish heritage speakers tested in the same linguistic property in Spanish and English – the present study confirmed that Spanish is the weaker language in this sample, as shown by the scores on the Spanish vs. English proficiency measures used. Unlike what Montrul (Reference Montrul2006) found, however, in the present study some transfer effects from English were detected in the interpretation of definite articles in Spanish. The effects found in this study are similar to the transfer effects from English onto Italian attested by Serratrice et al.'s (Reference Serratrice, Sorace, Filiaci and Baldo2009) study of plural NP interpretation by English–Italian bilingual children living in the UK. Even though the Spanish proficiency in the heritage speakers tested in the present study ranged from intermediate to advanced, many Spanish heritage speakers accepted ungrammatical bare plural NPs in the Spanish Acceptability Judgment Task (mean 50% accuracy), and 13 of 23 (57%) Spanish heritage speakers preferred the specific interpretation of definite plurals in the Spanish Truth-value Judgment Task, unlike the Spanish native speakers. No transfer effects were observable in this group with the task testing the interpretation of definite determiners in inalienable possession constructions (the PSMT). There were no detectable transfer effects from Spanish into English in any of the tasks.

According to the L1 literature reviewed, Spanish-speaking children are quite accurate in their acquisition of articles with generic reference and with inalienable possession. By contrast, English-speaking children seem to go through a “Spanish-like” stage in English, during which they initially overgeneralize definite determiners in generic contexts and in inalienable possession contexts (Pérez-Leroux et al., Reference Pérez-Leroux, Munn, Schmitt and DeIrish2004a; Pérez-Leroux et al., Reference Pérez-Leroux, Schmitt, Munn, Bok-Bennema, Hollebrandse, Kampers-Manhe and Sleeman2004b). However, the results of the Spanish heritage speakers in this study are more in line with the trends found in adult L2 acquisition and child bilingualism, where transfer effects from the dominant language have been found in studies of generic reference. Serratrice et al. (Reference Serratrice, Sorace, Filiaci and Baldo2009) found that Spanish–Italian bilingual children were native-like in Italian (Italian and Spanish have the same distribution of definite articles in generic contexts) but that the English–Italian bilingual children tested in the UK (as opposed to a similar bilingual group tested in Italy) showed significantly more transfer effects from English into Italian. The Italian–English bilingual children were significantly more likely to accept ungrammatical bare plural noun phrases in generic contexts in Italian (e.g., In genere pomodori sono rossi “In general tomatoes are red”) than monolingual Italian children. Ionin and Montrul's (Reference Ionin and Montrul2010) and Ionin, Montrul and Crivos's (Reference Ionin, Montrul and Crivos2009) studies of adult L2 acquisition of Spanish and English similarly found L1 transfer in the two languages with the interpretation of definite plurals in generic contexts: at least at the lower proficiency levels, the English speakers in the Spanish study tended to interpret Spanish definite plurals as specific, while the Spanish speakers in the English study overwhelmingly interpreted English definite plurals as generic. The results of the present study suggest that Spanish heritage speakers make the same transfer errors at the level of morphosyntax (incorrect acceptance of bare plural NPs) and semantic interpretation as English-speaking learners of Spanish at low and intermediate stages of development. In Montrul and Ionin (in press) we directly compare a group of 30 Spanish heritage speakers (which includes the 23 heritage speakers from the present study) and 30 proficiency-matched L2-Spanish speakers on these properties to find out whether language dominance or age of acquisition (early in heritage speakers but late in L2 learners) mattered more for transfer. We found similar transfer effects from English onto Spanish in the two groups with ungrammatical bare plural subjects in generic contexts (AJT) and preference for a specific as opposed to generic interpretation of definite plurals in the TVJT. As in the present study, there were no transfer effects from English with the interpretation of definite articles in inalienable possession constructions (PSMT); the two experimental groups were quite native-like in this respect. We conclude that language dominance, rather than age of acquisition, matters for transfer in these two groups, at least in the linguistic domain investigated.

Recall that for Vergnaud and Zubizarreta (Reference Vergnaud and Zubizarreta1992), the definite determiner in Romance can be an expletive element (a form with no semantic content) which occurs with both generic reference and inalienable possession for syntactic reasons. However, while we found transfer effects with generic reference of definite plurals in the present study, no effects were found with definite articles in inalienable possession contexts. That is, the heritage speakers were native-like in both English and Spanish on the latter. If these results are corroborated by other studies, this would suggest that, perhaps, the semantics–syntax link between generic reference and inalienable possession is not as strong as Vergnaud and Zubizarreta (Reference Vergnaud and Zubizarreta1992) propose, or even that generic reference and/or inalienable possession are not related to the existence of an expletive determiner in Romance. Alternatively, it is possible that these two properties are related at the underlying level, but that they do not emerge at the same time in adult L2 and bilingual grammars due to independent reasons (such as less frequency in the input of generic uses of articles than of articles in inalienable possession contexts). Although other studies of L1 acquisition of inalienable possession have questioned Vergnaud and Zubizarreta's (Reference Vergnaud and Zubizarreta1992) proposal on both conceptual and empirical grounds (Baauw, Reference Baauw, Cremers and den Dikken1996, Reference Baauw2000), these studies have not tested the same subjects’ knowledge of definite determiners in generic contexts and inalienable possession constructions. While we tested both phenomena with the same group of heritage speakers, we used different tasks to test the two properties, and the differential results may be a methodological artifact. Further studies testing the relationship between the two constructions in different populations should be carried out, with similar methodologies. Finally, the fact that we did not find transfer effects with the particular inalienable possession constructions tested in our study does not preclude the possibility that transfer effects may be found with other inalienable possession constructions in Spanish, perhaps those that involve reflexive verbs (Juan se afeitó la barba “Juan shaved his beard”) and dative clitics (Susana me mojó la cara “Susana wet my face”). In fact, these structures are quite complex and have been found to be quite problematic for adult English-speaking L2 learners of Spanish (Pérez-Leroux et al., Reference Pérez-Leroux, Lord, O'Rourke, Centeno Cortés, Pérez-Leroux and Liceras2002).