Introduction

On 8 July 1876, Captain Joseph Wiggins of Sunderland (1832–1905) (Fig. 1) set out on his third polar expedition in an attempt to reach one of the mighty Siberian rivers, the Ob’ or the Enisei. His objective was to establish a commercial shipping lane that would link Britain and Siberia through the Kara Sea. The expedition achieved partial success by completing a one-way journey to the Enisei. On the return voyage, however, Wiggins’s screw schooner Thames was lost. The commercial performance of the expedition was also discouraging. Nevertheless, despite this dismal start, Wiggins persisted, staging expeditions to the Kara Sea for two more decades.

Fig. 1. Captain Joseph Wiggins during his last visit to Eniseisk, 1895. Courtesy of A. I. Kytmanov Eniseisk Museum of Local Lore.

One hundred and forty years later, in 2016, Thames was discovered in a tributary of the Enisei River. Earlier, in 2015, the steamer Phoenix, which Wiggins commanded in 1887, had also been discovered. While these two vessels have a far less dramatic history than those of Sir John Franklin’s, they are reminders of Great Britain’s contribution to the development of the Northern Sea Route. Moreover, they are mementoes of a complicated, but to some extent, successful cooperation between the British and the Russian empires in establishing commercial relations in the Arctic.

A recent publication by David Saunders in Polar Record (Reference Saunders2017) about Joseph Wiggins is a welcoming sign that this prominent figure has not been forgotten in his home country. Saunders not only rebrings the story of Wiggins to the anglophone reader, but complements it by addressing a large body of Russian historical literature and, most importantly, Russian archival sources. Saunders (Reference Saunders2017) sees Wiggins’s voyages as mercantile expeditions, not voyages of discovery, and relates the captain’s misfortunes to economic and political tension between British commercial interests and Russian protectionism. Economically, this was the primary cause for Wiggins’s and his British associates’ inability to transform the Kara Sea Route into a regular shipping lane. However, it was also Wiggins’s concept of the route that was flawed. Today, the Northern Sea Route is one of the most technologically advanced waterways in the world, equipped with complex navigational aids, powerful icebreakers, and ports designed to cope with the heaviest ice. In Wiggins’s time, however, many, including the captain himself, supposed that it was enough to have a good vessel commanded by a determined and skilled captain to tame the impregnable ice cellar.

Despite their commercial objective, Wiggins’s voyages to the Ob’ and Enisei were in essence polar expeditions venturing into the unknown. In the 19th century, the Kara Sea Route was not a shipping lane in the sense the Northern Sea Route is today. It referred to any passage through the Kara Sea to the mouths of the Ob’ and the Enisei. Knowledge, particularly concerning the physical geography, and, most importantly, the hydrography of this sea and its inflowing rivers, was inadequate. Without accurate nautical charts and pilots, Wiggins had only his seamanship and experience to rely on. Even on his last successful expedition in 1895, he used data that were predominately one and a half centuries old. By then, the first results of the Russian Hydrographical Expedition of the Arctic Ocean (1894–1904), the first major survey of the Kara Sea since the Great Northern Expedition (GNE) (1733–1743), were only being published. Nonetheless, despite being armed with only “primitive knowledge” of the Kara Sea (Josephson, Reference Josephson2014, p. 25), Wiggins conducted more expeditions to this sea than any of his contemporaries and had the highest expertise in navigating these waters in the 19th century.

While acknowledging the need for some measures, such as escorting convoys with a special ice strengthened vessel, the captain argued that the Kara Sea was as navigable as any other and could be penetrated by conventional vessels (or those with slight modifications) (Viggins, Reference Viggins1895, p. 13; Saunders, Reference Saunders2017). This optimism, however, was misleading, and those who followed it, assured by years of more or less successful voyages, risked finding themselves in a lethal struggle with the ice, as had the expedition of Georgii L. Brusilov in 1912. Ironically, Brusilov used the same vessel, Blencathra (renamed Sviataia Anna) that had taken part in Wiggins’s 1893 expedition. Wiggins had advocated using such wooden ships, which he thought were sufficient, to convoy vessels bound for Siberia (Viggins, Reference Viggins1895, pp. 13–14). Unfortunately for Sviataia Anna, there was no icebreaker to help her when she froze into an ice field and drifted north just 17 years after Wiggins’s encouraging report in St Petersburg.

Certainly, these are no grounds for accusing the captain for his confidence in the Kara Sea route, which sprang from his positive seafaring experience. Surely, he realised the potential of icebreakers for polar navigation; however, he must have also seen that their exploitation was too expensive and would undermine the commercial side of the voyages. Furthermore, the epoch of icebreakers came only decades after the first Arctic icebreaker, Ermak, entered service in 1899. This was because there was no clear understanding of how exactly this new technology should be used, despite vague plans for utilising icebreakers for communicating with Siberia (Saunders, Reference Saunders2017). Eventually, the first attempted use of Ermak for escorting a convoy into the Kara Sea in 1905 lapsed and she was transferred to the Baltic, remaining there until 1934 (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong1952, p. 71). Other icebreaking vessels were later exploited on the Kara Sea. However, they were uncommon even during the renowned Kara Sea (Barter) Expeditions of the 1920’s (Belov, Reference Belov1959, p. 212). Two factors spurred the reintroduction of icebreakers: navigation along the entire length of the Northern Sea Route and the need to prolong the navigation season in the Kara Sea. In Wiggins’s day, however, such objectives did not exist.

Despite his success as a practitioner, Wiggins is far less renowned than many of his contemporary polar explorers. The captain’s obscurity stems from his inability to communicate his expertise to the world. To our knowledge, he left virtually no records or detailed accounts of his expeditions with the exception of a few shallow reports made at various learned societies in Britain and Russia (Viggins, Reference Viggins1877; Wiggins, Reference Wiggins1877; Viggins, Reference Viggins1895). Because of this, the scientific community of the age could not fully appreciate the importance of his exploits. Furthermore, from the very start, Wiggins’s voyages were overshadowed by those of the Swedish polar explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (1832–1901), who unlike Wiggins returned from his Kara Sea expeditions (1875, 1876) with extensive scientific results that were diligently published (Hämäläinen, Reference Hämäläinen2015, p. 30). Furthermore, Nordenskiöld became the first known explorer to traverse the entire Northeast Passage, a feat that made him a leading figure in Arctic history. Wiggins, on the other hand, would never be centre stage. Memory of him began to fade soon after his death. Even detailed studies of the exploration history of the Kara Sea and the Enisei, written less than a decade after he was gone, do not mention his name among other explorers (Blizniak, Reference Blizniak1914, p. 7).

There was, however, a short-lived revival of interest in Wiggins during the 1920–1930’s in Soviet polar literature (Sibirtsev & Itin, Reference Sibirtsev and Itin1936, p. 30), which can be ascribed to the success of the Soviet Kara Sea Expeditions and the reestablishment of commercial relations with Great Britain via this route. It was then that professor Vize (Reference Vize1936) gave, perhaps, the highest assessment to the captain’s commitments:

“There cannot be any doubt that the honour of conquering the most important step in the practical usage of the Northern Sea Route to the estuaries of the rivers of Western Siberia belongs to this [Wiggins] valorous and clever mariner.” (p. 176)

However, this readiness to credit a foreigner for developing the Northern Sea Route quickly ended. During the ideological clashes of the era of High Stalinism (1945–1953), particularly the infamous campaigns against “cosmopolitanism” and “idolising the West”, the role of westerners in such national projects as the Northern Sea Route was significantly belittled, a tendency which was continued in future Soviet historiography. Most of all this affected practitioners like Wiggins, who was now regarded as an agent of British capitalism, interested solely in profiting from his exploits (Pinkhenson, Reference Pinkhenson1962, pp. 76–77). Obviously, attempts to reassess the role of foreigners by western historians faced severe criticism from their Soviet colleagues (Pinkhenson, Reference Pinkhenson1962, p. 17). On the contrary, western polar explorers such as Nordenskiöld and Fridtjof Nansen escaped the fate of their utilitarian counterparts. Nordenskiöld’s turbulent background with his participation in pro-Finnish political gatherings during the 1850s and subsequent emigration to Sweden earned him a token of sympathy among Soviet scholars who held him short of being a revolutionary (Pasetskii, Reference Pasetskii1979). Nansen, likewise, was highly respected in the Soviet Union, especially because of his help to the Soviet republic during the Volga famine of 1921–1922.

All this made Wiggins and his voyages obscure footnotes to polar history. Regrettably, this view point continues to prevail even in the latest Russian publications (Emelina, Savinov, Filin, Reference Emelina, Savinov and Filin2019, p. 11).

So, how significant was Wiggins’s contribution to the development of the Northern Sea Route? He was certainly a talented polar navigator and devoted to the idea of opening a sea route to Siberia, but was he actually, as his biographer, Henry Johnson, declared “the modern discoverer of the Kara Sea Route”? Let us try to answer these questions by closely examining Wiggins’s first expedition to the Enisei in 1876–1877 (Fig. 2), which in essence set the blueprint for all future commercial expeditions and was the precursor of the Soviet Kara Sea Expeditions.

Fig. 2. Map of the Kara Sea and inflowing rivers with locations visited by the expedition.

Planning the expedition: connections and maps

Considering that Wiggins’s first two expeditions (1874 and 1875) to the Russian Arctic as well as his motifs have been extensively discussed in historical literature (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, pp. 15–81; Armstrong, Reference Armstrong1952, pp. 3–5; Krypton, Reference Krypton1953, p. 31; Pinkhenson, Reference Pinkhenson1962, p. 76; Stone, Reference Stone1994; Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1996, pp. 29–30; Saunders, Reference Saunders2017), we shall not inquire into the events leading to his decision of finding a maritime trade route to the mouths of the Ob’ and Enisei. However, it is worth examining the captain’s knowledge on the Kara Sea and northern Siberia as this not only fits his expeditions into proper geographical context but also suggests his incompatibility with the psyche of his contemporary polar explorers and men of business.

Wiggins is not known to have conducted any extensive research on the Kara Sea prior to his voyages (Saunders, Reference Saunders2017). His knowledge on the subject, therefore, arrived from whatever English sources on Siberia he could find. One such book was Ferdinand von Wrangell’s Narrative of an Expedition to the Polar Sea (Reference Wrangell and Sabine1840) (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, 19; Saunders, Reference Saunders2017). From it, Wiggins learned about the voyages of the Pomors to Mangazeia and the Enisei in the 17th century:

“They [the Pomors] were accustomed to sail in small flat vessels, or ladji, from the White Sea and from the mouth of the Petchora, across the Sea of Karskoie, as far as the entrances of the Obi and Jenisei. Sometimes they performed the whole voyage by sea; in general, however, to lessen the distance, they were in the habit of drawing their boats across the [Iamal Penisula]….” (Wrangell, Reference Wrangell and Sabine1840, p. xviii)

This passage was extremely important to Wiggins. If the Pomors had been able to use this route two and a half centuries ago travelling in “wretched flat-bottomed boats, sewn together with willow twigs” (Eden, Reference Eden1879, p. 257), “what is there to prevent the same thing being done now by the superior class of steam shipping of the present day?” he argued (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 49). Therefore, Wrangell’s book was among Wiggins’s main sources on the Kara Sea. He might have read other authors, such as the prominent polar explorer and admiral Friederich Benjamin von Lütke (Fedor Petrovich Litke), but it is highly disputable whether by 1876 be had become acquainted with Georg Adolf Erman’s Travels in Siberia (Reference Erman1848) (Saunders, Reference Saunders2017). The captain would have definitely taken notice, as Saunders (Reference Saunders2017) argues, of the passages containing Erman’s description of “Ivanof’s survey of the northern coasts” (Erman, Reference Erman1848, pp. 25, 27–29).

In 1827–1828, the Russian naval officer I. N. Ivanov had surveyed the coast of the Baidaratskaia Bay [Baidaratskaia Guba], the Iamal Peninsula [Poluostrov Iamal], and the west coast of the Ob’ Gulf [Ob’skaia guba] (Pasetskii, Reference Pasetskii1984, p. 176). Deeply interested in this part of the Kara Sea, Wiggins would have certainly tried to learn more about this survey and obtain some relevant materials. However, as witnessed by his voyage into the Baidaratskaia Bay in 1876, the captain had no knowledge of Ivanov’s exploits.

Prior to his expeditions, Wiggins contacted a number of leading experts on the Arctic. The most important acquaintances were the Scottish Arctic explorer James Lamont and the prominent German geographer August Petermann of Gotha. Lamont, whose yacht Diana Wiggins had chartered in 1874, had a rich background in polar exploration, particularly a hunting expedition to the Kara Sea in 1870. Six years after the expedition, he published a book titled Yachting in the Arctic Seas (Reference Lamont1876), which contained a superb description of the geography of Novaia Zemlia and its surrounding seas. Lamont expressed considerable interest in matters which affected navigation most – sea currents and winds. Drawing from the accounts of earlier exploration, primarily, the Russian expeditions of the first half of the 19th century and the recent voyages of the Norwegian sealers, coupled with his personal experience, Lamont (Reference Lamont1876) drafted a list of recommendations for sailing through the Kara Sea to the Iamal (pp. 180–182). Of these, Wiggins almost certainly knew as he had precisely followed them in 1874. During that expedition, however, he concluded that the voyage should begin a month later than Lamont had suggested (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 40–41).

Wiggins approached Petermann in 1874. The German geographer, who was at that time preoccupied with disproving the “ice-cellar” concept, which he had earlier been so enthusiastic about (Tammiksaar & Stone, Reference Tammiksaar and Stone1997), would have been eager to help Wiggins, perhaps, seeing in him that “experienced and determined navigator” he had envisaged two decades earlier (Petermann, Reference Petermann1853, p. 135). Petermann needed authentic geographical data to advance in his studies, and, as anticipated, Wiggins’s voyages added to his understanding of the Kara Sea (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, pp. 51–52; Tammiksaar & Stone, Reference Tammiksaar and Stone1997). In his turn, Petermann contributed to Wiggins’s knowledge of the Arctic. The captain became particularly fixated with the idea that warmer Barents Sea waters, flowing through the straits of Novaia Zemlia, open the southernmost part of the Kara Sea to short periods of navigation (Eden, Reference Eden1879, p. 258; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 20). This idea derived from the recent investigations on the hydrology of the Kara Sea; according to them, warmer North Atlantic waters reach the northeast part of Novaia Zemlia, a deduction first made by Karl Ernst von Baer [Karl Maksimovich Ber] on the basis of the observations of earlier expeditions (Tammiksaar, Sukhova, & Stone, Reference Tammiksaar, Sukhova and Stone1999) and backed by Petermann (Tammiksaar & Stone, Reference Tammiksaar and Stone1997). During a Russian expedition to Novaia Zemlia in 1870, a study of this current was made by Alexander von Middendorff [Aleksandr Fedorovich Middendorf] (Tammiksaar & Stone, Reference Tammiksaar and Stone2007). He corresponded with Petermann on the results of the expedition, aware of the German geographer’s interest in the Gulf Steam problem (Tammiksaar & Sukhova, Reference Tammiksaar and Sukhova2015). In his report, published in Petermann’s Geographische Mitteilungen, Middendorff (Reference Middendorff1871) mentioned a side current flowing through the Matochkin Shar that is affected by warmer Atlantic waters (p. 31), thereby further convincing Wiggins in his theory.

Petermann gave Wiggins some of his newest maps of the Kara Sea (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 23). Among them must have been a map of Novaia Zemlia (1872) and one of the coast between the rivers Enisei and Lena (1873); both maps had been published in Petermann’s journal (Tammiksaar & Sukhova, Reference Tammiksaar and Sukhova2015). Although these maps updated knowledge on the Kara Sea and the estuaries of the Ob’ and the Enisei by reexamining the results of earlier expeditions and adding new data from contemporary voyages, they were of little practical value. Besides, the maps were outdated as most of the hydrographic data they contained came from the observations of the GNE. A more functional map was the Russian nautical chart of the Kara Sea and Novaia Zemlia issued by the Hydrographic Department in 1872 (Fig. 3).

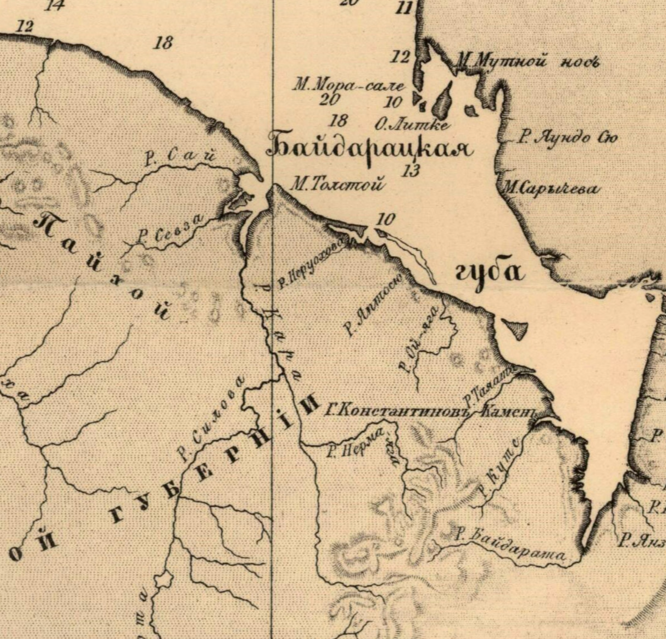

Fig. 3. Map of the Kara Sea and Novaia Zemlia (fragment showing the Baidaratskaia Bay) issued by the Russian Hydrographic Department in 1872. Courtesy of the Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Along with the original GNE framework, this map included Ivanov’s survey and had a corrected coastline configuration based on a series of recent high-precision observations (Sergeevskii, Reference Sergeevskii1936, p. 14). Water depths, however, remained nominal and, therefore, could only be used for general guidance, making it necessary to perform time-consuming soundings. A copy of this map was sent to Wiggins by the Russian gold miner Mikhail Konstantinovich Sidorov (1823–1887) after the Whim expedition in 1875 (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 69)

Sidorov had been attempting to establish a sea route between Europe and Siberia since the 1850s and was well-informed about this part of the Arctic. In spite of this, his knowledge was also constrained by the scarcity of data on the Kara Sea and its inflowing rivers. This can be deduced from a map found in Sidorov’s collection at the Archives of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg (SPF ARAN 270/5/302, l. 1). While one would expect from Sidorov’s latest map an aggregate piece of cartography with major improvements, there is little difference between this map and the one published by the Hydrographic Department, with the exception of the addition of certain data from an expedition headed by the geologist I. A. Lopatin to the lower reaches of the Enisei in 1866, during which, the Enisei Estuary had been resurveyed (Kleopov, Reference Kleopov1964, pp. 16, 19).

Wiggins also had a map presented to him by Nordenskiöld (Fig. 4). The map is well-known because its final version, drawn by Petermann, was published in a number of reports on Nordenskiöld’s expeditions to the Enisei (Stuxberg, Reference Stuxberg1877; Nordenshel’d & Tel’, Reference Nordenshel’d and Tel’1880). All of Petermann’s maps, however, lack a number of details that are present in the Russian map of 1872. This cartographic confusion resulted in Wiggins making an erroneous discovery in 1876.

Fig. 4. Fragment showing Baidaratskaia Gulf from Nordenskiöld’s map of his expedition to the Enisei in 1875. Courtesy of the Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Such was Wiggins’s assortment of knowledge on the Kara Sea by the time of his third voyage. It was utterly unsystematic and made the expedition depended on the captain’s seamanship and luck rather than hard science. Despite his previous experience in navigating these waters, it can hardly be considered sufficient and could not compensate the deficit of accurate geographical data. Countless white spots remained on the map, some of which Wiggins set out to explore. And yet, he was not an explorer in the sense of a researcher like Nordenskiöld or Nansen. Wiggins belonged to the older type of explorers; he was the merchant adventurer, the navigator, in pursuit of the unknown, but at the same time, gripped by the practical side of his discoveries.

Having settled the theoretical part of his endeavour, Wiggins set out to find an employer. During the Whim expedition in 1875, Wiggins approached the Russian admiral Gottlieb Friedrich (Bogdan Aleksandrovich) von Glasenapp, former chief officer of the port of Arkhangel’sk and an advocate of developing Russian foreign trade. Obligingly, he advised Wiggins to contact Sidorov. Being a prominent figure within the Imperial Society for Encouraging Russian Mercantile Shipping, Glasenapp introduced Wiggins to its members.

The society, like many other Russian professional societies, had been established in the years following the liberal reforms of Alexander II (r. 1855–1881). As follows from its name, the objective of the Imperial Society for Encouraging Russian Mercantile Shipping was to act as an intermediary between the government and the mercantile and intellectual communities for the purpose of stimulating the development of Russian commercial shipping. The society’s branch in St Petersburg was deeply involved in the Siberian sea route problem, especially after the first successful expeditions, making Wiggins a welcomed figure.

In a short while, Wiggins began a correspondence with Sidorov (Studitskii, Reference Studitskii1883, p. 160; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 69). In exchange for a renewal of Sidorov’s proposed £2,000 prize for reaching Obdorsk, the captain offered to survey the Baidaratskaia Bay and facilitate a shipping scheme through the ancient Mangazeian route to the Ob’. The two men met in November 1875 in St Petersburg. Wiggins had been invited to an extraordinary joint meeting of the Imperial Society for Encouraging Russian Mercantile Shipping and the Imperial Society for Encouraging Trade and Manufacture (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877b, 162). The captain, introduced as an “English marine engineer”, made a report on his expedition aboard Diana and the perspectives of trade through the mouths of the rivers of Western Siberia (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877a, p. 263; Studitskii, Reference Studitskii1883, pp. 88–95).

Enthusiastically, Wiggins suggested a series of projects for developing the sea route, including a hydrographic survey of the Ob’ and Enisei estuaries, establishing a river-portage route to the Ob’, and setting up meteorological stations on Vaigach Island [ostrov Vaigach] and along the Siberian coastline (Studitskii, Reference Studitskii1883, p. 85). He agreed to join Sidorov’s Northern Company and acquire on its behalf a steamer in Britain the following year. Accompanied by two Russian naval officers, he was then to take this vessel, laden with cargo, up the Ob’ Gulf and the river Ob’ to the town of Berezov. En route, the expedition was to conduct relevant cartographic and hydrographic surveys and determine sites for erecting navigational aids. After reaching Berezov, Wiggins was to take the same steamer to the Enisei to collect a cargo of graphite and deliver it to Europe (Krypton, Reference Krypton1953, 34). In return, he would receive £2,400 from Sidorov to compensate his expenses during the 1874 and 1875 expeditions. The captain would also be allowed to keep all the profits from imported and exported merchandise for six years.

The proposed scheme resembles a walkover, not a complicated shipping operation as its architects, seemingly, lacked the slightest understanding of polar navigation. They supposed that an ordinary ship could easily complete a trip to two destinations, both of which were situated far inland, and make a return voyage in one season. This was, of course, impossible. The crew would lose precious navigation time searching for deepwater channels and performing exhaustive surveys; transhipment operations, particularly loading the vessel with local cargo on a wild riverbank without proper machinery or even a pier, would further jeopardise the expedition’s outcome. Therefore, the entire 35,000-rouble scheme (Studitskii, Reference Studitskii1883, p. 88) was a sham orientated on extracting as much profit as possible with the smallest investments. And before it even had a chance to start, the merchants were arguing about Wiggins’s role in the company. Many disfavoured his candidature, assuming threat from British foreign trade, and the captain was eventually turned down. Soon, the entire project was terminated. Wiggins realised that the Russian capitalists were reluctant of long-term investments and mutual cooperation, preferring to surrender costly endeavours to the state.

Eventually Wiggins was able to secure £1,000 from Charles Gardiner, a wealthy financier and yachtsman, interested in the captain’s exploits in the Kara Sea. Gardiner contacted Aleksandr Sibiriakov, another rich Siberian merchant interested in the northern routes and famous for financing Nordenskiöld’s expeditions, and urged him to contribute another £1,000. Finally, the Imperial Society for Encouraging Russian Mercantile Shipping gave Wiggins 7,000 roubles (Studitskii, Reference Studitskii1877a, p. 116), seemingly, with Sidorov’s help.

Wiggins purchased Thames, a screw schooner with a gross tonnage of 126 tons (Fig. 5). She was originally built as clipper schooner in 1847 in Aberdeen (Lloyd’s register, 1848). By 1874, she had been fitted with a direct action 20 hp steam engine with inverted cylinders, which rotated a single screw propeller. Thames was rigged as a topsail schooner. Some unspecified repairs had been made to the underside of the hull (Lloyd’s register, 1874), and Wiggins spent a considerable sum of money reinforcing the hull with double elm planking and casing it with iron. The captain wrote that he was pleased with the ship, which was “extraordinarily well-built” and “the most suitable vessel for the job” (Wiggins, Reference Wiggins1876). However, drawing two fathoms (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877c, p. 191), Thames would be difficult to sail in shallow waters. Knowing that the Ob’ Gulf was abundant in shoals (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, pp. 87, 89), Wiggins decided to try searching for the fabled portage route from the Baidaratskaia Bay to the Ob’ instead of directly sailing to this river; of this he informed Leigh Smith (Wiggins, Reference Wiggins1876). If the shortcut was not found, the expedition would attempt to reach Obdorsk through the Ob’ Gulf.

Fig. 5. Thames in the Kara Sea.

However, the expedition’s programme was soon changed. Before setting sail, Wiggins received a letter from Sidorov with a proposal of 200 tons of graphite as a prize cargo that was to be collected from skipper David Ivanovich Shvanenberg either at zimov’e Krestovskoe (a seasonal settlement in the Enisei Gulf [Eniseiskii zaliv]), or at the confluence of the rivers Enisei and Kureika (Krypton, Reference Krypton1953, p. 72).

With Thames fitted out and stocked with provisions for six months, the expeditions was prepared to overwinter in Siberia. A steam launch was taken aboard to assist navigation in the shallows. Despite these preparations, it is unlikely that Wiggins thought of this journey as a true polar expedition. He rather imagined it as a conventional commercial voyage with a slightly higher difficulty level. A characteristic of this was the cursory selection of the crew, who were neither seasoned polar sailors nor had personal commitment to the captain. An all-out description of the crew is given by Johnson (Reference Johnson1907): “[the] crew was a scratch one, picked up hurriedly at Sunderland” (p. 162).

Bearing in mind the alleged commercial nature of the expedition, Wiggins loaded Thames with a cargo of sample goods provided by the merchants of Sunderland (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 84). A copy listing this merchandise and signed by Wiggins is held at the Krasnoiarsk State Archive. There are two lists: cargo taken to Turukhansk and cargo remaining at Kureika (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 12). The lot of goods in Turukhansk comprised 19 bales of unspecified cloth with a recorded gross weight of 18 poods (1 pood equals 16.38 kg) and 153 funts (one funt equals 0.35 kg), four crates weighing 3 poods and 123.5 funts (contents unspecified), and one barrel containing sample cutlery and crockery weighing 4 poods, 24 funts; the overall weight was just over 500 kg. The goods remaining at Kureika received a more detailed description; however, their weight was not recorded. There were 22 packages of various ropes, including half a package of Manila rope, one coil of hemp rope, 24 packages of fishing line, six rolls of sailcloth, one barrel, and two large baskets with cutlery and crockery. The sailcloth and ropes were, evidently, the spare rigging and sails of Thames, deemed as merchandise after Wiggins tried to sell them to Shvanenberg. This odd assortment of goods, fittingly described by Henry Seebohm (Reference Seebohm1882) as that of “odds and ends and rubbish” (p. 46), exposes the captain’s indifference to the mercantile outcome of the expedition, a characteristic that he shall demonstrate throughout his polar career.

In the Kara Sea

Wiggins sailed from Sunderland on 8 July. On 3 August, having overcome intense southerly winds and fogs, Thames penetrated into the Kara Sea through the strait of Iugorskii Shar without encountering any ice (Viggins, Reference Viggins1877, p. 241; Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 4). The vessel then sailed south-east along the coast of the Iugorskii Peninsula [Iugorskii Poluostrov] and crossed the Baidaratskaia Bay over to Litke Island [ostrov Litke], the east coast of which was inspected to determine its potential as a haven. Shortly afterwards, Thames weighed anchor and sailed north along the Iamal coast, but was halted at 70°45′N by an ice barrier stretching west and had to return to exploring the southernmost part of the gulf and approaches to the Baidarat River. On 16 August, another attempt to sail north encountered impregnable ice at 70°10′ N. Here, from the captain of a Norwegian sealing sloop, Wiggins learned about Nordenskiöld’s and Gardiner’s successful expeditions, both of which had penetrated into the Kara Sea that year (Viggins, Reference Viggins1877, p. 243; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 88). During the following week, the expedition continued exploring the waters around Litke Island and the Mutnyi Bay [Mutnyi Zaliv] along with the mouth of the Iuribei River on the east coast of the Iamal. However, all attempts to find a navigable channel to what had in fact been the entrance of the sought route to the Ob’ failed. Following this, Thames sailed north to inspect the ice conditions, however, at 70°20′N, was stopped by ice for the third time. On the 24th, the expedition headed for the Karskaia Bay [Karskaia Guba]. In search of a harbour, Wiggins tried to ascend the river Kara in the steam launch; however, the river was found to be very shallow. The ship then returned to the southern part of the Baidaratskaia Bay and traced the coastline to the Baidarat River in hope of rendezvousing a German expedition sent by the Bremen Verein fur die Deutsche Nordpolarfahrt to survey the isthmus between the gulf and the Ob’ (Studitskii, Reference Studitskii1877a, p. 68; Viggins, Reference Viggins1877, p. 244; Krypton, Reference Krypton1953, p. 51). This expedition was among three others sent to find the ancient Pomor route that year (Studitskii, Reference Studitskii1877a).

Not having found the Germans, Wiggins crossed the gulf westwards and examined, what he thought was an uncharted island (Viggins, Reference Viggins1877, p. 244; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 96). Here, he found a good harbour that could be used if the isthmus scheme worked (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877b, p. 162; Eden, Reference Eden1879, p. 262; Viggins, Reference Viggins1877, p. 245). Wiggins suggested naming this island after Sibiriakov and the harbour after Gardiner, assuming that Sibiriakov Island [Ostrov Sibiriakova] in the Enisei Gulf had been known to the Russians as ‘Ostrov Kuskin’ (also Kuzkin) long before its discovery by Nordenskiöld (Nordenskiöld, Reference Nordenskiöld1885, p. 238).

In fact, the supposition that Sibiriakov Island had been discovered prior to Nordenskiöld and named Kuskin was so popular, that the Russian naval hydrographer Andrei I. Vilkitskii assigned both names to the island in 1895. Later, it was shown that “Ostrov Kuskin” is actually Olenii Island [Ostrov Olenii] (Popov & Troitskii, Reference Popov and Troitskii1972). Even though there had been assumptions on the existence of a large island in the Enisei Gulf long before the Swedish expedition (RGAVMF 913/1/30, l. 44; Kleopov, Reference Kleopov1964, p. 93; Popov & Troitskii, Reference Popov and Troitskii1972; Troitskii, Reference Troitskii1975, p. 18), its existence had been proved only by Nordenskiöld, making him its rightful discoverer. On the contrary, it was Wiggins’s ‘Siberiakof Island’ that had already been discovered. Perhaps relying on Nordenskiöld’s map (Fig. 4) as his latest piece of cartography, Wiggins failed to notice that the island was depicted on the 1872 Russian map (Fig. 3), which he also had. The island, known as Levdiev Island [Ostrov Levdiev], first appeared on Isaac Massa’s map in the early 17th century. On later maps, the island reappeared and disappeared, until its existence was finally ascertained by Ivanov during his survey of the Iamal in 1827–1828.

On 2 September, after a southerly wind set in, Thames sailed for Belyi Island [Ostrov Belyi]. Caught in a gale, the vessel dropped anchor off the north coast of the island. Four days later, having rounded the island, Thames reached the Ob’ Gulf. After consulting his crew, Wiggins decided to head for the Obdorsk. With her leaky boiler repaired, Thames attempted to make it up the gulf, constantly struggling against contrary winds and a strengthening current. Having travelled south less than in 1874, Wiggins decided to change course and head for the Enisei, despite the tempting 3,000-rouble prize promised to him by Sibiriakov if he reached Obdorsk that year (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 86).

En route to the Enisei, the expedition discovered an uncharted island off the Iavai Peninsula [Poluostrov Iavai], known today as Shokal’skii Island [Ostrov Shokal’skogo] (Viggins, Reference Viggins1877, p. 245; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 98, Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877b, p. 162, Pinkhenson, Reference Pinkhenson1962, p. 76). Wiggins proposed naming the island Chernyi (Black) due to its appearance and position – opposite of Belyi Island. The island’s discovery caused controversy. Thus, David Shvanenberg (Reference Shvanenberg1877b) disputed its existence when, the following year, he sailed, as he claimed: “within five minutes of it” (p. 253). The island did, however, appear, marked as a “Low Sand Island”, on a map compiled for a book on Charles Gardiner’s discoveries of the remains of Willem Barentsz’s expedition (De Jonge, Reference De Jonge1877). The map also shows Wiggins’s ‘Siberiakof Island’ and Gardiner’s Haven (Fig. 6). However, apart from reporting his finds to Gardiner and the Imperial Society for Encouraging Russian Mercantile Shipping, Wiggins made no further attempts to claim his discoveries, and the existence of the island was soon forgotten. It was rediscovered only in 1922 by a Soviet hydrographic expedition (Popov & Troitskii, Reference Popov and Troitskii1972).

Fig. 6. Map fragment from Jan Karel Jacob de Jonge’s Nova Zembla (1596–1597). The Barents relics (1877), showing Wiggins’s Siberiakof Island (1) and an island opposite Belyi (2).

After winding her way around the islands and shoals between the Iavai Peninsula and the Enisei Gulf, Thames arrived in view of the west coast of the Taimyr on 9 September. In order to reballast the vessel and seeking cover from strong north-westerly gales, the expedition stopped at an uncharted island, known today as Nosok Island [Ostrov Nosok], off the northern tip of Sibiriakov Island (Viggins, Reference Viggins1877, p. 246; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, pp. 100–102). Thereby, Wiggins discovered a second unknown island. He named the cove where Thames had been anchored – “Ballast Cove”.

On the 12th, the expedition set out for the Enisei. A notable episode occurred at Cape [Mys] Efremov Kamen’. Here, Wiggins found a wooden post erected by pilot Fedor Minin of the GNE in 1738 (RGAVMF 913/1/31, l. 44 verso). From this post, Wiggins removed a wooden tablet with a carved text recording Minin’s arrival at this location and took it to Eniseisk, where the find was donated to the local museum (Lotsiia Eniseiskogo zaliva, 1924, p. 46; Popov, Reference Popov1990, p. 135).

Having reached the rendezvous at zimovie Krestovskoe, Wiggins found no signs of Shvanenberg’s vessel. Still hoping to make a return journey that year, Wiggins continued upriver. At stanok (a hamlet with postal duties) Korepovskoe, where the expedition arrived on 22 September, a local inhabitant volunteered to guide the vessel to Dudinka. However, he could not find a navigable channel in the maze of the Brekhov Islands [Brekhovskie ostrova]. Fortunately, the expedition met a Samoyed (Nenets or Dolgan) named Pat’ka (different versions of his name exist, including Pachkar (Viggins, Reference Viggins1877, p. 248), Patshka (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 176), and Patchka (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 206)), who offered to guide Thames through the channels, which he knew very well. This was the second time Pat’ka assisted an expedition; a decade earlier, he worked as a guide for Lopatin (Kleopov, Reference Kleopov1964, pp. 99–100). Without this assistance, Wiggins would have had serious trouble in finding a navigable passage through the Enisei Delta and be compelled to overwinter much further north, or turn back like Nordenskiöld, who had been unable to find a deepwater channel for his steamer, Ymer (Nordenshel’d & Tel’, Reference Nordenshel’d and Tel’1880, pp. 131–134).

In 1887, during his second expedition to the Enisei, Wiggins found Pat’ka (the blind king of the Samoyeds), who once again guided him through the maze of islands.

Despite the generally friendly attitude of the local Russian and indigenes population towards foreigners, as seen from other expeditions, Pat’ka’s and other locals’ willingness to cooperate with the British can be attributed to Nordenskiöld’s 1876 expedition. The Swedish explorer had substantial support from the tsarist government including the right to deliver a party of goods free of duty “for the first time in the history of the northern sea route” (Krypton, Reference Krypton1953, p. 43). Following the governor’s orders, instructions to aid the Swedes were issued to all those who resided north of Dudinka (GAKK 595/19/6144, l. 43 verso). Therefore, Wiggins and his companions may have been taken for members of the Swedish expedition and promptly assisted. However, the opportunity of bartering or receiving presents was an equally, if not more, significant reason to cooperate with the crew of a foreign ship.

From Cape [Mys] Muksuninskii, the British preceded on their own, as Pa’ka did not know this part of the river. With the help of the steam launch, they arrived at Tolstyi Nos (Tolstanosovskoe), where they were met by Nordenskiöld’s pilot, Fedor Selivanov of Turukhansk and village starosta (warden) Afanasii Koksharov. With their help, Thames was piloted to Dudinka. There, Wiggins was told that Shvanenberg had sailed downriver and was now somewhere in the vicinity of the Brekhov Islands. The captain asked Selivanov and Koksharov to find Shvanenberg and inform him that Thames was proceeding upriver (Viggins, Reference Viggins1877, p. 248). Piloted by the watchman of Dudinka, Thames reached the river Kureika on 17 October. It was decided to leave the ship for the winter here (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, pp. 109–110). A dispatch was sent to Turukhansk (Staroturukhansk today) requesting to inform Sibiriakov of Thames’s safe arrival at Kureika.

Shvanenberg rendezvoused with the British on 9 November. The following day, it was decided to send four reindeer sledges laden with Sunderland goods to Turukhansk. The first party was led by two of Shvanenberg’s men; Wiggins and Shvanenberg were to follow when the reindeer were brought back.

Customs problems in Turukhansk

A picturesque but exaggerated description of the trip from Kureika to Turukhansk is given in Wiggins’ biography (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, pp. 113–119). The events are depicted as a sledge ride up the frozen river with various random encounters, including an unpleasant incident with the pristav (magistrate) of Turukhansk. A closer examination of this affair provides insight into the economic, administrative, and social situation in this part of Siberia.

News of the expedition’s arrival reached the local administration before communication was interrupted by the Enisei freezing up: the river was the only winter road between the remote riverine settlements. On 23 October, while Wiggins was still at Kureika, Raznotovskii (first name unknown), the pristav of Turukhansk filed a report to the governor of the Eniseisk Province [Eniseiskaia Guberniia] about the arrival of an “English two-masted steamer” to collect a cargo of graphite and overwinter at Kureika (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 4). The pristav then set out for Kureika, with intentions, as he reported, “to provide the foreigners with any necessary legal assistance” and to inspect the delivered goods. Justifying the unauthorised transportation of imported cargo to Turukhansk, Shvanenberg later rebuked Raznotovskii for taking almost a month to come for inspection (Shvanenberg Reference Shvanenberg1877a, p. 259). However, the pristav could not have arrived earlier as the ice on the Enisei had not frozen. Of this Shvanenberg was aware, as only a few weeks earlier, while dog-sledging from Tolstyi Nos to Kureika, he had fallen through the ice on several occasions, saved, as he wrote, “only by the dogs’ miraculous ability to swim between ice floes” (Shvanenberg, 1877, p. 258).

At stanok Angutskii, halfway to the Kureika, the pristav intercepted the caravan of British merchandise, which he immediately arrested (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 75). The following day, he reached Kureika and demanded an official trade permit from Wiggins. At this point, Raznotovskii and Shvanenberg clashed. Unable to understand Russian, Wiggins could only incomprehensively observe the scene and rely on Shvanenberg for interpreting. With the skipper’s active involvement, the conflict has often been passed off as the continuation of a personal affair between him and Raznotovskii (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 75; Vladimirov, Reference Vladimirov1940, pp. 12–13). Shvanenberg held a grudge against the pristav for his attempt to detain several crewmembers of Severnoe Siianie earlier that year (Shvanenberg, Reference Shvanenberg1877a, p. 254; Vladimirov, Reference Vladimirov1940, p. 9). After the arrest of Wiggins’s goods, including the spare sailcloth and tackle from Thames that Shvanenberg wanted for his vessel, the skipper became further enraged and insulted the official. Appalled, Raznotovskii arrested the remaining goods and ordered both mariners to Turukhansk, where they were detained for a few days, before being allowed to continue their trip south.

The incident at Turukhansk is another notable indicator of expedition’s ill-preparedness from a commercial standpoint. It would not have occurred if Wiggins had received permission to import foreign goods into Siberia beforehand, as Nordenskiöld had done earlier (Krypton, Reference Krypton1953, p. 43; Goncharov, 2014). All the captain had was a letter from Alexander von [Aleksandr Fedorovich] Berg, the Russian general consul in London, guaranteeing him an “open passage” and a letter, dated 15 May 1874, from Edward Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby requesting to provide Wiggin with all necessary assistance (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 11).

The captain found himself amid an intensifying social conflict, which stemmed from the tangle of economic and administrative problems of the Turukhanskii Krai, a territory within the borders of today’s Taimyr and Evenkiia. Governing this enormous region had long posed a problem to the central authorities. On the one hand, the pristav was vested with virtually unchecked administrative power, including police and military powers, which enabled some officials to ruthlessly maintain control through physical force and plunder (Kytmanov, Reference Kytmanovno date, p. 312). On the other, the pristav was unable to effectively govern such an enormous territory with the few resources placed at his disposal. This limited his actual power to a small area around Turukhansk.

In contrast, the owners of the few of riverine paddle steamers, which had appeared just over a decade earlier, could effectively reach the northernmost settlements and trade at their advantage. By the time of Wiggins’ expedition, the shipping companies of Eniseisk, the historical centre of northern trade, had become the dominant economic power in the region (Gaidin & Burmakina, Reference Gaidin and Burmakina2016). This resulted in rivalry between the administration and merchantry. The main flashpoint was the spirits trade, which was an essential tool in the hands of the shippers, deservingly described as the “arch-robbers of the Yen-e-say´” (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 46). Despite the fact that Russian laws forbade alcohol trade in the north, it flourished, securing enormous profits. “Some enriched, while the others were driven into poverty, particularly the indigenes, with their passion for wine like none other”, wrote Rasnotovskii (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 88). In fact, the natives suffered most of all, being robbed by all groups of the Russian population. In order to ensure a blind eye from the Turukhansk authorities, the merchants copiously bribed them. Unlike his predecessors, however, Raznotovskii strongly opposed the spirits trade and rejected bribes, thereby becoming a bitter adversary of the merchants (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 46). To make matters worse, he imposed taxes on those traders, who made profits of 300–400% selling manufactured goods while offering the lowest bid on local produce (furs and fish) (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 87). In these circumstances the pristav’s conflict involving a foreigner offered the merchants a desired pretext for his removal. A petition to the provincial governor, signed by both Wiggins and Shvanenberg (Fig. 7), persuades its reader to sympathise with the two mariners, who had become victims of the pristav’s arbitrary conducts. And, as expected, on receiving this document, the governor relieved Raznotovskii of his post without making any further inquiries (Krypton, Reference Krypton1953, p. 44).

Fig. 7. Wiggins and Shvanenberg’s petition to the deputy pristav of Turukhansk. Courtesy of State Archive of the Krasnoiarskii Krai.

Heavily relying on Shvanenberg for interpreting, Wiggins would have seen the whole affair from his companion’s perspective, ultimately siding with him in the conflict. However, unlike his Russian counterpart, the captain seemingly was not much concerned about the affair. This is how the priest Vasilii Dmitrievich Kas’ianov describes Wiggins and Shvanenberg’s stay in Krasnoiarsk in December 1876:

‘The captain of an English vessel, Wiggins, and the captain of a vessel from Eniseisk, Shvanenberg came to my house in my absence. I met them again in the evening. The former is sleeping, while the latter is complaining about the police pristav of Turukhansk … A foul business indeed. It shall not go unnoticed abroad. When Wiggins sailed for Siberia, thousands bade him farewell and his nearest warned him that in Siberia he might he hanged. It is woeful to hear that this warning had not been idle’ (Brodneva, Reference Brodneva2013, p. 176).

There was, of course, no risk of being hanged. The passage, however, reveals the provincial intelligentsia’s anxiety of a negative representation of Siberia in the west, which, among other things, might impede Kara Sea shipping that had barely begun. It was well understood that the perception of the country as an inhospitable land of exile, which appeared during the first half of the 19th century (Gutmeyr, Reference Gutmeyr2017, 79), continued to live on in the form of a more depressing house of the dead. In these circumstances, the Siberians were desperate for a positive image of the country.

From Eniseisk to England

Without any news from Wiggins, his supporters in St Petersburg were becoming increasingly worried. Sibiriakov even proposed an unspecified award for determining the expedition’s whereabouts (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877b, p. 162). Finally, in early December, Sidorov received a telegram from Eniseisk informing him of Wiggins’s safe arrival. Two days later, Wiggins wired to Sidorov himself. These were among the first telegrams sent from Eniseisk: the line had been completed shortly before Wiggins’s arrival on 7 December (Kytmanov, Reference Kytmanovno date, p. 521). Wiggins and Shvanenberg then travelled to Krasnoiarsk. Here, after a personal plea, the governor promised to return Wiggins his goods (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877b, p. 163). The Imperial Society for Encouraging Russian Mercantile Shipping, in its turn, sent a telegram to the governor-general of Eastern Siberia asking his help in returning the imported cargo and granting the captain a right to sell it free of duty (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877b, p. 163). On 28 December, the Ministry of Finances granted such a privilege to Wiggins (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 33; Krypton, Reference Krypton1953, p. 44).

Wiggins and Shvanenberg travelled by sledge through Western Siberia to Nizhniy Novgorod and then by train to St Petersburg. In the Russian capital, both seafarers made speeches at the Imperial Society for Encouraging Russian Mercantile Shipping (Fig. 8), describing their polar expeditions, and were elected its lifetime members. However, as in 1875, no concrete support was provided to Wiggins. The Russians were suspicious of the British and were unwilling to cooperate. This was made clear in the society secretary’s response to a proposal of an Anglo-Siberian company in January 1877:

“I doubt that captain Wiggins is capable of establishing a company under his supervision… I propose that we establish a Russian company for the merit our fatherland.” (Studitskii, Reference Studitskii1877b, p. 288)

This never happened. Unable to enlist the support of major Russian capitalists, and, at the same time, wary of foreign involvement, the society futilely sought finance from the Russian government. The latter, however, like the emerging Russian industrial elite, ignored the Kara Sea projects fearing the potential risks and being preoccupied with more pressing matters such as railway construction. During the following decade, the society continued promoting various schemes to make the route function, most of which remained on paper.

Disappointed, Wiggins returned to England. The expenses for his trip from Eniseisk to Sunderland and for the crew’s salary were once again covered by Sibiriakov and Gardiner. The latter also gave Wiggins £300 for his next year expedition (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, pp. 132–133). The results of the 1876 voyage were published in various journals, including The Geographical Magazine (Wiggins, Reference Wiggins1877).

Fig. 8. Photograph of Wiggins and Shvanenberg during their stay in St Petersburg in the winter of 1876–77. Courtesy of A.I. Kytmanov Eniseisk Museum of Local Lore.

The 1877 expedition

On his return to England in February 1877, Wiggins was approached by the industrialist and amateur naturalist Henry Seebohm (1832–95), who wanted to go to Siberia for the purpose of ornithological and ethnological research (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 5). This was his second trip to Russia, the first being to the Pechora River in 1875. On 1 March, Wiggins and Seebohm departed for Russia. In St Petersburg, they met the Russian Minister of Interior Aleksandr Egorovich Timashev and the Finance Minister Michael von Reutern; letters of introduction were given to both travellers after discussing the perspectives of Kara Sea trade (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 12, 23). However, nothing came of these initiatives. The timing for joint British–Russian projects was wrong due to the escalation of diplomatic tension between the two countries in view of the upcoming Russo-Turkish War.

When Wiggins and Seebohm arrived in Eniseisk in early April, they were greeted by Shvanenberg and the town’s society, among whom was Peter [Petr] Boiling, an emigrant from Heligoland and now the local shipbuilder (Fig. 9). While Wiggins would be busy in Kureika loading graphite onto Thames and preparing her for the return voyage, Seebohm intended to conduct his studies, for which purpose he purchased a vessel from Boiling and arranged it to be towed to Kureika as soon as the ice on the Enisei broke up.

Fig. 9. Joseph Wiggins and Peter Boiling in Eniseisk (1877). Courtesy of A.I. Kytmanov Eniseisk Museum of Local Lore.

Since this little vessel would play an important role in the history of the Northern Sea Route (Beer, Reference Beer2013), it is worth describing her. She was built in Eniseisk for the purpose of transporting Nordenskiöld’s goods delivered in 1876, but was not used. Seebohm christened her Ibis – a reflection of his passion for ornithology. Existing accounts refer to her as a schooner, though it is not known what rig she carried before being refitted with Thames’s sails. Boiling later issued a certificate to Shvanenberg in which the following specifications were written: length – 56 (Russian) feet; breadth – 14 feet; hull height – 7 feet; displacement – 50 tons; deadweight tonnage – 3,000 poods. The hull was built of larch (to the waterline), pine, and spruce (Vladimirov, Reference Vladimirov1940, p. 22). This description characterises the state of the Enisei shipbuilding industry, which at the time could only produce flat-bottom wooden riverine barges and rowboats, with the exception of the steamer Enisei (1863) and the schooner Severnoe Siianie (1876). Unsurprisingly, many Siberians were eager for the sea route to function. New ships could be delivered to the Enisei to ensure competition and stability in riverine shipping.

Back in the Turukhanskii Krai

Travelling by sledge, Wiggins and Seebohm came to Turukhansk in the second half of April. The new pristav, von Gazenkamper (name unknown), readily returned Wiggins’s goods. A shop was set up in the town to sell the merchandise. However, business went bad. Most of the stock did not appeal to the locals, either being too expensive or impractical. Eventually, a sum of only a few hundred roubles was secured with a profit of 10–50% (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 42). The remaining goods were carried back to Thames.

Shvaneberg, who also came to Turukhansk, was busy arranging the delivery of graphite to Kureika and securing a certificate from the pristav asserting that a specific amount of graphite had been extracted: a measure necessary for Sidorov to claim the possession of the mines (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 51).

The location where Thames had overwintered (Fig. 10) was barely inhabited: on the opposite bank of the Enisei was the stanok of Ust’kureika, which according to an 1859 census had a population of 25 with three households (Maak, Reference Maak1864, p. 29). The crewmen were provided with living quarters on the bank of the Kureika in Sidorov’s cabin, which had four rooms, an iron stove, and a brick Russian stove for heating and baking bread (Shvanenberg, Reference Shvanenberg1877a, 259). With the arrival of Wiggins, Seebohm, and Shvanenberg on 23 April, all nine men were found in good health. Wiggins had taken care to enforce scurvy prevention methods, including a supply of lime juice and dried vegetables. The captain had also instructed the crew to perform daily physical exercises and stock a supply of firewood for the return journey as no coal was available (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, 55). However, the regular supply of fresh provisions delivered by the Russian administration had been just as important. After the incident in Turukhansk caught the attention of the general-governor of Eastern Siberia, the local authorities were instructed to assist the British crew by all possible means. Regular reports were sent from Turukhansk, informing the governor that all was well in Kureika. For instance, a report dated 11 February 1877 stated that the crew were regularly supplied with all necessary provisions including medicaments from the shop of one Aleksandr Smirnov (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 45). Another account remarks that the good health of the crew was a consequence of a whole variety of activities, including reading, hunting, and even (!) dancing with the local Ostiak (Ket) women (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877c, 189).

Fig. 10. Confluence of the rivers Enisei and Kureika where, Thames was moored during the winter and spring of 1876–1877.

During the winter, the vessel froze to the riverbed, and in March, von Gazenkamper reported that the schooner was in danger and urged the crew to take immediate action; if the vessel foundered, the pristav was to immediately rescue the British. At the time of Wiggins’s return to Kureika, Thames was anchored within 6 m off the elevated (north) bank of the river. The vessel was held by three anchors (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 57). With the help of the local Russian peasants, the crew cut away the ice around and from under the ship (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 60). Despite these preventive measures, the ice breaking up on the Enisei severely damaged the rudder and hull of Thames, requiring repairs to these parts of the ship (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p.117; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 143).

In early May, Shvanenberg accompanied by eight workers and a group of Kets travelled up the Kureika to the graphite mine. Wiggins had taken a sample of graphite from the cargo of Severnoe Siianie to London; however, it proved to be of low quality, so Sidorov ordered Shvanenberg to extract a new consignment of this mineral (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, pp. 69–70). When loaded onto Thames, the graphite doubled its purpose as ship ballast.

In June, Ibis arrived under tow by the steamer, Nikolai, and under Boiling’s supervision. The steamer also delivered provisions for the voyage and a batch of Siberian sample goods, purchased earlier in Eniseisk (Kytmanov, Reference Kytmanovno date, p. 533). After transhipment, the shipper’s agent attempted to charge a second payment for the prepaid goods (twenty casks of tallow and the same number of sacks of biscuits) (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 140), thereby further fouling Wiggins’s attitude towards the Siberian merchantry.

Loss of Thames

On 30 June, Thames and Ibis set sail down the Enisei piloted by Boiling. He had some experience in sailing this part of the river, however did so aboard vessels, drawing only one fathom (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877c, p. 191). The high water changed the riverscape, submerging many low islands, and soon Thames grounded a sandbar off the head of Ostrov Tal’nichnii, about 100 km from Kureika (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877c, 191). In attempt to save the vessel, the graphite was cast overboard, an act that would be justified by Sidorov (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 64; Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877c, p. 191), but not in later publications, where the incident would be used as an argument to show the reluctance of foreigners to export Siberian produce (Makarov, Reference Makarov1898, p. 14). After using a whole arsenal of exhaustive methods, Thames was set afloat (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, pp. 151–152; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, pp. 144–145). However, having sailed only to the village of Igarka, Thames ran aground again. This time, despite all efforts, the vessel could not be moved from the shoal. The water level fell, making any further attempts to save the vessel futile. It is unclear what exactly the reason of this accident was: an undercurrent, a sudden gust of wind (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 156), and the damaged rudder (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877c, p. 191) were among the possible causes, as was Wiggins’s confident procession down the Enisei “as if he were at sea, with all sails set” (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877 d, p. 260). However, the objective reason for the wrecking was the total absence of navigation charts for the Enisei, a problem recognised after the loss of the vessel (Moiseev, 1879, p. 131), but not solved until decades later.

Anxious to continue the voyage, Wiggins suggested using Ibis. With little enthusiasm from his crew and Seebohm, the captain proposed sailing to Gol’chikha and there decide on further actions. The stranded steamer was stripped of her rigging and instruments to increase the seaworthiness of Ibis. Four of Thames’s crew were chosen to continue the voyage north, while the rest remained at Igarka awaiting a steamer to be taken to Eniseisk. Morale among the crew was so low, that Wiggins had to resort to threats in order to continue the voyage (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 157). Seebohm (Reference Seebohm1882) points to the unpopularity of the captain among his men due to his tactlessness and, moreover, the teetotalism administered aboard Thames (pp. 162–163), an argument with which Johnson (Reference Johnson1907) disagrees (p. 149). As mentioned earlier, the men’s unwillingness to follow their captain lay in the fact that they were not a consolidated team, but a random group of ordinary mercantile seamen. They had already spent a whole winter in northern Siberia and were not prepared to take further risks.

During the trip to Gol’chikha, Ibis performed surprisingly well for a flat-bottomed boat, being able to sail close to the wind and in depths of only 3 feet (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 164). On 11 July, the expedition reached Dudinka. Waiting for better weather, the ship remained for some time under the cover of Karaul’nyi Mys, which Seebohm (Reference Seebohm1882) obsoletely names ‘Tolstyi Nos’ (p. 171). At the Brekhov Islands, the expedition encountered Shvanenberg and his companions, who were heading for Kureika in a small boat. Sidorov’s schooner, Sevenoe Siianie had been wrecked by ice floes and all but one of her crew perished during the winter. Having recruited new men, Shvanenberg was looking for a vessel to sail to across the Kara Sea. With the bulk of the riverine fleet loading fish at Gol’chikha, Wiggins’s offer of a passage to this outpost was readily accepted as it offered a chance to obtain a ship.

On 19 July, Ibis finally reached Gol’chikha. This became the final destination for the expedition: the crew refused to take the makeshift schooner out to sea despite Wiggins’s attempts to persuade them. Unwilling to continue the journey, Seebohm also abandoned Wiggins, boarding himself a passage to Eniseisk on one of the three riverine steamers anchored at Gol’chikha (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 185; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 151; Stone, Reference Stone1994). The fate of Ibis was also decided. While Wiggins was still hoping to at least sail her to the Ob’, Shvanenberg saw an opportunity to obtain the vessel for his voyage to St Petersburg. Eventually, Ibis was sold to Shvanenberg for a price of 600 roubles in a bill upon Sidorov; Wiggins received 400 roubles in cash and 300 roubles in a bill upon Sidorov for the anchors, sails, and tackle. Despite their previous relations, Wiggins later had to file a suit against Sidorov to retrieve his money. Seebohm, who, unlike Wiggins, had not obtained Sidorov’s endorsement, was unable to settle financial scores with the merchant (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, pp. 188–189; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, pp. 151–152). After this incident, Wiggins and Sidorov became estranged and no longer cooperated.

Ibis was renamed Utreniaia Zaria (Morning Dawn) and successfully sailed to Norway, from where she was towed to the Russian capital, becoming the first vessel to accomplish such a voyage.

The long way home

Having parted with Shvanenberg, Wiggins boarded a passage to Eniseisk aboard the steamer Nikolai. He had to decide the fate of Thames after an “official inspection” of the wreck in the presence of himself, von Gazenkamper, and Sidorov, who came north to insure the transfer of the promised graphite, and, as claimed in his letter to the Russian Geographical Society, with intentions to sail across the Kara Sea “to the shores of Norway” with either Wiggins or Shvanenberg (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877 d, p. 260). Thames sat on dry land 30 m from the water’s edge with her keel buried in sand; she had a starboard list, a damaged stern, and broken rudder (GAKK 595/19/265, l. 64). It was suggested that she could be towed off the mudbank if sufficient help was provided. Wiggins consulted Boiling, who concluded that the expenses of salvaging the steamer would exceed its cost, thereby sealing Thames’s fate. Boiling organised a rudimentary auction at which the vessel was sold to a joint venture of Eniseisk merchants for a price of 6,100 roubles (Sidorov, Reference Sidorov1877c, p. 192; Kytmanov, Reference Kytmanovno date, p. 533).

Even after being sold, misfortune continued to pursue Thames. The merchants were able to preserve the vessel in tact during next year’s ice breaking on the Enisei and float her again. She was towed upriver by Balandin’s steamer Aleksandr; however, at the village of Goroshikha, the vessel ran aground and then sank in the mouth of the Sal’naia kur’ia River. The company, nonetheless, compensated this loss by stripping Thames of her engine and equipment (Kytmanov, Reference Kytmanovno date, p. 534). As is happened, the merchants were chiefly interested in the vessel’s machinery (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 161; Stone, Reference Stone1994). The last recorded sighting of Thames was in 1885. She was seen lying on her side 20 m from the riverbank almost totally submerged. Part of the boiler was still visible. The merchant, who recorded this, went out on a boat to salvage whatever was left on the schooner; however, all he could get was a piece of metal rigging (AGE 6/1/35, l. 27–27verso).

Seebohm reached St Petersburg in late September. Wiggins arrived shortly after. He had made one more trip down the Enisei to transfer Thames to her new masters before departing Eniseisk. Overall, he travelled five times down and up the river in 1876–1877. The crew also returned to England safely (Seebohm, Reference Seebohm1882, p. 276).

Discussion

The Thames expedition of 1876–1877 was one of the first shipping operations in the Kara Sea; however, it was not yet a true commercial expedition as its primary objective was to determine the potential of various routes to Siberia. Wiggins succeeded in sailing his ship upriver to Kureika, almost 1,000 km further than Nordenskiöld, thereby proving the accessibility of the Enisei for seagoing vessels (Us, Reference Us2005, p. 56). Despite the loss of his ship, Wiggins was able to recognise the potential advantages of the Enisei over the Ob’ for maritime shipping. He became even more convinced in this after attempting one last ascent up the shallow Ob’ Gulf and losing virtually the entire cargo on the return journey (Balkashin, Reference Balkashin1879, p. 11; Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 191–192). However, it would not be until the late 1920s and years of hydrographic surveying that his foresightedness of the Enisei’s superiority for Kara Sea shipping was finally acknowledged. And, ironically, it was near the place where Wiggins had seen Thames for the last time that the first permanent Siberian seaport, Igarka, appeared in 1929.

The expedition yielded a number of important scientific results, among which was the discovery of two islands in the Kara Sea and a description of the Baidaratskaia Gulf. Valuable material on the ornithology, ethnology, and history of the Enisei had been gathered. This was done mainly by Seebohm, who, among other, collected 15,000 specimens of bird skins and eggs (Johnson, Reference Johnson1907, p. 153). His observations were published as Siberia in Asia (1882) and The Birds of Siberia; a Record of a Naturalist’s Visits to the Valleys of the Petchora and Yenesei (1901). Seebohm’s observations on matters concerning the economic development of country, as well as its administrative and social aspects, significantly contribute to our knowledge of the history of the northern reaches of the Enisei.

Conclusion

Thus, having summed up the results of the expedition, let us return to the question of Wiggins’s role in the development of the Kara Sea Route.

While Wiggins, in essence, was a merchant seaman (Saunders, Reference Saunders2017), his failure as an entrepreneur, coupled with his inability to establish business connections, and, above all, his indifference to commerce calls for a re-examination of his inducements. What drove Wiggins on, when so many quit? It was definitely not profit. Wiggins had a romantic notion that the Kara Sea Route was destined to serve a humanistic cause. This attitude made him careless in the selection of business partners, undermining his survival in the mercantile world. Moreover, Wiggins never had a concrete plan of what to import and export or how to facilitate the route; it seems that he cared little about the logistics of his expeditions. This clearly distinguishes him from figures such as his contemporary Baron Ludwig von Knoop (Barr, Krause, & Pawlik, Reference Barr, Krause and Pawlik2004) or the Norwegian entrepreneur Jonas Lied, who drew immense inspiration from Wiggins (Lied, 1946/Reference Lied2009, pp. 64–65), and could, otherwise, be regarded as Wiggins’s heir.

What is most striking about Wiggins, though, is that he never produced any practical materials (charts or pilots) on navigating in the Kara Sea and the mouths of the Ob’ and, especially, the Enisei. It appears that he did not even share his expertise with his partners. For instance, in a paper on the sea route published by the Anglo-Siberian Trading Syndicate Ltd, which contains a general guide to sailing in the Kara Sea, we find only the crudest recommendations and a schematic map (Butler & Fletcher-Vane, Reference Butler and Fletcher-Vane1890, pp. 4–5). Furthermore, this paper is based primarily on Nordenskiöld’s writings, not Wiggins’s, which is surprising, since the latter had been an employee of the syndicate. Another notable example occurred when Wiggins was offered to escort three Russian vessels to the Enisei in 1893; one Russian naval officer was so dismayed by the captain’s seemingly superficial knowledge of the route that he wrote:

“The plan for the voyage, as proposed by Wiggins, was of an extremely primitive nature. Most probably two hundred years earlier, our coastal inhabitants who sailed their tiny ‘kochas’ were guided by these same rules.” (Semenov, Reference Semenov1894, pp. 51–52; Krypton, Reference Krypton1953, p. 83)

Moreover, Wiggins did not even claim his discoveries, as we have seen earlier. This deprives the captain of vanity, rightfully making him the “humble mariner” and a model of Victorian virtue as portrayed by Johnson.

Overall, Joseph Wiggins was visionary, who believed that one day the Kara Sea Route would benefit both the peoples of Britain and Russia through commerce and free-trade. However, his approach to the route’s development was outdated. Polar shipping required massive investment into its research and infrastructure. This, Wiggins failed to recognise, treating his expeditions as bold adventures, assured by his own success and endeavour. His views on the Kara Sea Route never evolved and, in essence, his last expeditions followed the scenario of 1876–1877 less the search for alternative routes.

At the same time, Wiggins’s idea of turning the Kara Sea into an international commercial highway turned out to be long-lasting. Foreign vessels, many of which were British, came to Igarka until the 1970s. Today, decades after the collapse of the Soviet Union, it is tempting to imagine that Joseph Wiggins’s concept of the Siberian sea route might be brought back.

Thus, Wiggins’s greatest contribution to the development of the Northern Sea Route was his devotedness to the idea of commercial shipping on the Kara Sea. Where others stopped, he continued, making even the pessimists believe that one day the waterway to Siberia will flourish.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous referees for helping improve this paper.

Financial support

The reported study was funded by RFBR, the government of the Krasnoyarsk Territory and Krasnoyarsk Region Science and Technology Support Fund according to the research project: No. 16-11-24010.

Conflict of interest

None.