Feminist analyses have provided a social constructionist account of the female body, showing that in Western societies the female body is socially constructed as an object to be looked at and evaluated. The objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, Reference Fredrickson and Roberts1997) argues that women often are regarded as objects by society, with the focus being placed on all or part of their bodies in a sexual context rather than on their abilities. When objectified, women are reduced to the status of “mere instruments” available for visual inspection, evaluation, and the pleasure of others (Bartky, Reference Bartky1990, p. 26). Through the pervasiveness of objectification experiences, women are socialized to internalize an observers’ perspective upon their body. This process is called self-objectification and happens when women treat themselves as objects to be considered and evaluated based upon appearance (Fredrickson & Roberts, Reference Fredrickson and Roberts1997).

Mass media play a key role in promoting self-objectification through the extensive sexualization of women’s body and the separation of sexualized body parts from the rest of the female body. However, it is not just exposure to mass media per se that seems detrimental: the real problem comes when individuals internalize such sexually objectifying messages (Vandenbosch & Eggermont, Reference Vandenbosch and Eggermont2012). The internalization of the objectifying messages from the media causes women to self-objectify and guides the perception of their worth (Rollero, Reference Rollero2015; Vandenbosch & Eggermont, Reference Vandenbosch and Eggermont2012). Empirical research has largely demonstrated that internalization of media ideals has a direct impact on self-objectification processes (Karazsia, van Dulmen, Wong, & Crowther, Reference Karazsia, van Dulmen, Wong and Crowther2013; Moradi & Huang, Reference Moradi and Huang2008).

Since the foundational work of Fredrickson and Roberts (Reference Fredrickson and Roberts1997), numerous studies have investigated the damaging psychological corollary of self-objectification. Correlational studies have found relationships between self-objectification and body shame, appearance anxiety, negative and depressive affect, and various forms of disordered eating (e.g. Miner-Rubino, Twenge, & Fredrickson, Reference Miner-Rubino, Twenge and Fredrickson2002; Tiggeman & Kuring, Reference Tiggemann and Kuring2004). Experimental research has demonstrated that heightened self-objectification promotes body shame, appearance anxiety, and hinders task performances (for a review see Moradi & Huang, Reference Moradi and Huang2008).

Although objectification theory is grounded in women’s experiences, researchers have begun to investigate the applicability of this framework to explore men’s experience as well (e.g., Johnson, McCreary, & Mills, Reference Johnson, McCreary and Mills2007; Rollero, Reference Rollero2013). Men seem to experience lower self-objectification than do women, but especially young male adults are becoming increasingly more concerned with their physical appearance (Moradi & Huang, Reference Moradi and Huang2008; Weltzin et al., Reference Weltzin, Weisensel, Franczyk, Burnett, Klitz and Bean2005). This may be due to the increasing tendency to objectify men’s physiques in Western societies, which fosters body image concerns among men (Bully & Elosua, Reference Bully and Elosua2011; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, McCreary and Mills2007). Consistent with the pattern of findings in female populations, internalization of media ideals increases self-objectification even in men (Vandenbosch & Eggermont, Reference Vandenbosch and Eggermont2014) and men’s self-objectification is negatively correlated with self-esteem, positive mood and less disordered eating (Calogero, Reference Calogero2009; Rollero, Reference Rollero2013).

Surprisingly, to date empirical research has not focused on the effects of self-objectification in the context of social relationships, with few exceptions considering romantic relationships (e.g., Meltzer & McNulty, Reference Meltzer and McNulty2014; Zurbriggen, Ramsey, & Jaworski, Reference Zurbriggen, Ramsey and Jaworski2011). Exploring how self-objectification can affect the way individuals behave in their social context could contribute to advance our knowledge on objectification processes. If the focus on one’s own appearance interferes with time and attention dedicated to forming an authentic connection with a romantic partner (Zurbriggen et al., Reference Zurbriggen, Ramsey and Jaworski2011), this might happen even in the other kinds of relationships people are involved in. Individuals may experience disconnection from their feelings, values, aspirations, as significant portions of their conscious attention “can often be usurped by concerns related to real or imagined, present or anticipated, surveyors of their physical appearance” (Fredrickson & Roberts, Reference Fredrickson and Roberts1997, p. 180). In sum, driving the attention to physical appearance, self-objectification might affect authenticity in social relationships.

The conceptualization of authenticity

The notion of authenticity has long been a prominent concern for philosophers and social thinkers. In modern times, authenticity emerged as an essential concept within a number psychological perspectives, including existential (Yalom, Reference Yalom1980), humanistic (Maslow, Reference Maslow1973; Rogers, Reference Rogers1961), psychodynamic (Horney, Reference Horney1950), social (Kernis & Goldman, Reference Kernis and Goldman2006), and positive psychology (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, Reference Sheldon, Lyubomirsky, Linley and Joseph2004). As Maslow stated, “authenticity is the reduction of phoniness toward the zero point” (Maslow, Reference Maslow1973, p. 183). According to Rogers (Reference Rogers1961), authenticity can be conceived as the sense of empowerment and freedom to behave in a way which is an expression of deeply held principles, aims, and feelings, rather than the consequence of external expectations. Authentic individuals would experience coherence between their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Rogers, Reference Rogers1961).

Based on this Roger’s (Reference Rogers1961) theoretical foundation, a recent approach considers that, to be authentic, one’s actions should be in line with the personal values, beliefs and motivations of which one is aware (Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis, & Joseph, Reference Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis and Joseph2008). This approach conceptualizes authenticity as involving three components. The first aspect of authenticity is self-alienation and refers to the experience of feeling out of touch with the true self. Self-alienation is conceived as the degree of incongruence between the individual’s experience of physiological states, emotions, and cognitions and the way these experiences are represented in cognitive awareness (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis and Joseph2008). The second component is named authentic living and refers to the congruence between behavior and experience as consciously perceived. Authentic living implies being true to oneself and living in accordance with one’s values and beliefs (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis and Joseph2008). The third component is defined as accepting external influence and is related to the internalization of the views of other people. It involves the extent to which one accepts the influence of others and allows them to control his/her own actions (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis and Joseph2008). This model provides a comprehensive consideration of the concept of authenticity, as it encompasses both internal dimensions, i.e. the experience of being in touch and congruent with the true self, and environmental and social dimensions, i.e., the influence of others and the necessity to conform or not to their expectations. As Schmid (Reference Schmid, Joseph and Worsley2005) argued, since people are basically socially beings, self-alienation and authentic living can not be conceived without considering the role played by the social environment individuals live in. Consistently, literature has demonstrated that authentic behavior is a more property of social interactions than of persons: the experience of authenticity has been found to be strongest within social environments promoting self-disclosure and mutual social support and acceptance (Robinson, Lopez, Ramos, & Nartova-Bochaver, Reference Robinson, Lopez, Ramos and Nartova-Bochaver2012).

Over the past decade, the interest in the consequences and correlates of authenticity has significantly increased (Wickham, Reference Wickham2013). In general, research has largely shown that authenticity is fundamental for many positive outcomes. It is associated with greater life satisfaction and well-being, higher levels of self-esteem, and positive affect (Kifer, Heller, Perunovic, & Galinsky, Reference Kifer, Heller, Perunovic and Galinsky2013; Theran, Reference Theran2010; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis and Joseph2008) and predicts more adaptive coping styles (Kernis & Goldman, Reference Kernis and Goldman2006). Moreover, authenticity decreases negative affect, perceived stress, anxiety, and verbal defensiveness (Lakey, Kernis, Heppner, & Lance, Reference Lakey, Kernis, Heppner and Lance2008; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis and Joseph2008).

Current study

The aim for this research project was to bring the study of objectification processes into the context of social relationships, to understand the association between self-objectification and authenticity among young adults. Specifically, we were interested in examining whether self-objectification affects the extent to which individuals feel self-alienated, experience authentic living and accept others’ influence.

Based on prior research, we expected that internalization of appearance ideals would be related to valuing one’s appearance over competence, i.e., self-objectification (Karazsia et al., Reference Karazsia, van Dulmen, Wong and Crowther2013; Moradi & Huang, Reference Moradi and Huang2008), which in turn would decrease each dimension of authenticity in social relationships. By testing this model, we aimed to overcome two limitations of prior research by (a) extending the study of the damaging consequences of self-objectification to the context of social relationships; and (b) exploring whether the hypothesized relationships differ between men and women. As Moradi and Huang (Reference Moradi and Huang2008) pointed out, empirical research is necessary to evaluate, rather than assume, construct equivalence for men and women.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were 235 Italian undergraduates (55.7% females) attending the first year of the Faculty of Political Sciences at the University of Turin, a city of about 900000 inhabitants in the north west of Italy. Their mean age was 20.90 years (range: 19–27 years, SD = 1.86; men’s mean age: 20.71, SD = 2.18, women’s mean age: 21.05, SD = 1.55, T= –1.40, n.s.). The ethnic composition of the sample was completely homogeneous, being all participants Italian. They were recruited in two classrooms during a break and were given a copy of a self-reported questionnaire. Participants were told that their answers would have been treated in a strict confidence and the anonymity of all of them would have been secured. Informed consent was obtained by the students. No fulfilment of course requirements was given in exchange for their participation. The rejection rate was 3.8 %.

Measures

Data were gathered by a self-reported questionnaire which took about 15 min to be filled in. Participants were asked to complete the following scales:

Internalization of media standards

The 9-item Internalization-General subscale of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 (SATAQ-3; Rollero, Reference Rollero2015; Thompson et al., 2004) was used. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = definitely disagree, 5 = definitely agree). (α = .92). Sample of items include “I would like my body to look like the models who appear in magazines”.

Self-objectification Questionnaire

Following Noll and Fredrickson’s (Reference Noll and Fredrickson1998) procedure, participants were asked to rank a list of body attributes in ascending order of how important each is to their physical self-concept, from that which has the most impact (rank = 1) to least impact (rank = 12). Twelve body attributes were listed: six that were appearance based (i.e., physical attractiveness, coloring, weight) and six that were competence based (i.e., muscular strength, stamina, health). Scores were computed by summing the ranks for the appearance and competence attributes separately, then computing a difference score. Scores range from –36 to 36, with higher scores reflecting a greater emphasis on appearance, which is interpreted as greater self- objectification (Noll & Fredrickson, Reference Noll and Fredrickson1998). In the present study, a strong negative correlation was demonstrated between appearance and competence rankings, indicating good reliability (r = –.91, p = .02).

Authenticity Scale

This is a 12-item instrument that measures authenticity (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis and Joseph2008; for the Italian version see Rollero, Spotti, & De Piccoli, Reference Rollero, Spotti and De Piccoli2013). It contains three subscales, one of which is a positive indicator and two of which are negative indicators of authenticity. The positive indicator subscale refers to authentic living (AL) (4 items, i.e. “I think it is better to be yourself, than to be popular”, α = .74.). The negative indicator subscales refer to accepting external influence (AEI) (4 items, i.e. “I am strongly influenced by the opinions of others”, α = .83) and self-alienation (SA) (4 items, i.e. “I feel as if I don’t know myself very well”, α = .66). Items are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 7 (describes me very well).

Results

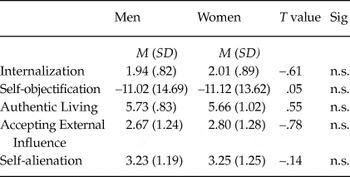

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. Before testing the hypothesized model, T-tests were performed to assess gender differences concerning internalization of media standards, self-objectification, and the three components of authenticity. As presented in Table 2, no significant difference was observed.

Table 1. Descriptive analyses and correlations of the studied variables

* p < .05 **p < .01

Table 2. Gender differences on the studied variables

The hypothesized relationships were tested with structural equation modelling (software Amos 4.0, Arbuckle & Wothke, Reference Arbuckle and Wothke1999) using the maximum likelihood method. As recommended (Bentler, Reference Bentler2007; Bollen & Long, Reference Bollen and Long1993), the model fit was tested by using different fit indexes to reduce the impact of the limits of each index: χ2, GFI (Goodness of Fit Index), Adjusted GFI, CFI (Comparative Fit Index), and RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation). For GFI, Adjusted GFI, and CFI values higher than 0.90 are considered satisfactory. As for RMSEA, values lower than 0.08 are indicative of model fit (Bentler, Reference Bentler2007).

The model tested proved satisfactory, according to all fit indexes, except χ2: χ 2 (3, N = 231) = 11.81; p = .01; GFI = .98; Adjusted GFI = .95; CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03. Given that the significance of χ2 depends on the sample size, the model could be considered well fitting (Bentler, Reference Bentler2007). All the estimated parameters were significant. Figure 1 shows the validated model. As expected, internalization of media standards lead to increased self-objectification (β = .33, SE = .08, p = .001), which in turn strongly related to accepting external influence (β = .50, SE = .01, p = .001) and self-alienation (β = .14, SE = .08, p = .04) and decreased authentic living (β = –.21, SE = .09, p = .001). Following the theoretical conceptualization of authenticity (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis and Joseph2008), the error terms for the three subscales were correlated and results showed that the correlations between the dimensions of authenticity were significant. Specifically, authentic living was negatively correlated with both accepting external influence and self-alienation, whereas these two last dimensions were strongly positively related.

Figure 1. Path diagram and standardized regression weights.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Finally, a multiple groups analysis assessed the moderating role of gender by testing whether the fit of the model, which assumes that the hypothesized relationships do not vary across gender and are thus constrained to be equal between men and women, differs significantly from the fit of a model that allows the relationships to vary between men and women (Byrne, Reference Byrne2010). Results revealed that the relationships did not significantly vary between genders, χ2 (4, 231) = 6.29; p = .18 Footnote 1 .

Discussion

The present research aimed to investigate the effects of self-objectification on authenticity in social relationships among male and female undergraduates. It was successfully tested a three-step process, which begins with the internalization of media standards. Such internalization raises the focus on appearance over competence, i.e. self-objectification, which in turn makes individuals less aware of their feelings and values, and more dependent on others’ influence.

Two conclusions can be derived. First, self-objectification has an impact on individuals’ perception of authenticity in social relationships. Consistently with findings about romantic relationships (Zurbriggen et al., Reference Zurbriggen, Ramsey and Jaworski2011), it is likely that high self-objectified undergraduates feel more self-alienated, as they experience higher disconnection from their physiological states, emotions, and cognitions. The objectification theory perspective posits that self-objectification leads women to separate themselves from their own bodily sensations, decreasing their sensitiveness to internal bodily states (Fredrickson & Roberts, Reference Fredrickson and Roberts1997). The present study represents a first attempt to investigate the effects of self-objectification on awareness of psychological states. Our results suggest that we are dealing with the same process: self-objectification, reflecting a focus on body appearance, diminishes individuals’ awareness not only of their own internal bodily states, but also of their own feelings, needs, desires and values. As above seen, feeling in touch with the true self is an essential component of authenticity (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis and Joseph2008). Being unaware of their psychological states, high self-objectified individuals are also more sensitive to external influences and behave less authentically. Another possible explanation suggests that self-objectified subjects are so embedded in self-objectification processes, which deny their value as persons (Fredrickson & Roberts, Reference Fredrickson and Roberts1997), that even if they are aware of their internal states, they believe that such states are unimportant, or at least less important than their appearance.

Second, the pattern of the above described relationships is similar across gender. Although previous literature has shown that men seem to experience lower self-objectification than do women (Moradi & Huang, Reference Moradi and Huang2008; Weltzin et al., Reference Weltzin, Weisensel, Franczyk, Burnett, Klitz and Bean2005) and it is a general consensus that body issues are more sensitive and problematic for girls than for boys (Balaguer, Atienza, & Duda, Reference Balaguer, Atienza and Duda2012; Borges, Gaspar de Matos, & Diniz, Reference Borges, Gaspar de Matos and Diniz2013), recent studies have demonstrated similar results across gender (Vandenbosch & Eggermont, Reference Vandenbosch and Eggermont2014). This may be due to the increasing cultural tendency to objectify men’s bodies as well. Indeed, in contemporary Western societies men are similarly exposed to images of body type ideals and encouraged to adopt the ideal body valued by society (Daniel, Bridges, & Martens, Reference Daniel, Bridges and Martens2014). Our findings support the idea that these increasing depictions lead to the development of self-objectification processes even within male population. However, they deserve future attention, as the experience of self-objectification may maintain gender-specific characteristics, even if both genders are similarly socialized to internalize and observers’ perspective upon their body.

Authenticity is recognized as a central component of the good life in philosophical thought and represents a key concept in psychology, as it is argued to serve as the foundation for a secure sense of high self-esteem that is resilient to external threats. Indeed, empirical research has largely demonstrated that authenticity plays a relevant role in enhancing or maintaining well-being (Davis, Hicks, Schlegel, Smith, & Vess, Reference Davis, Hicks, Schlegel, Smith and Vess2015). For this reason, it is essential exploring processes that may compromise authenticity, such as self-objectification.

The current study extends our knowledge on self-objectification processes. However, it presents some limitations. First, emotions were not considered. Theorists from the humanistic tradition suggest that emotions are central to authenticity because a feeling of authenticity signals to the individual that the self is integrated and organized (Sheldon, Ryan, Rawsthorne, & Ilardi, Reference Sheldon, Ryan, Rawsthorne and Ilardi1997). Future research should integrate in research the assessment of emotions. Moreover, authenticity represents a complex construct: other instruments, such as the Authenticity Inventory (AI-3, Kernis & Goldman, Reference Kernis and Goldman2006), or qualitative data would enrich knowledge on this construct and associated psychological variables. Another limitation is that the current sample is comprised of young adult. Given that authenticity is considered to be a developmental construct (Maslow, Reference Maslow and Maslow1962), the present results can not be generalized to adults in midlife or older adults. Finally, selecting only Caucasian subjects we did not examine the influence of culture, which is particularly relevant in reference to both self-objectification processes and authenticity as a value (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Lopez, Ramos and Nartova-Bochaver2012). Further research should consider the key role played by culture.