Introduction

The ASEAN–EU relationship is particularly significant in terms of trade and investment. Being a market with a population of about 600 million, accounting for more than US$1400 billion in global trade, ASEAN has become an increasingly important destination for EU producers and investors. The ASEAN bloc ranked third among the EU’s major trading partners outside Europe with total trade amounting to €246 billion in 2014. For ASEAN, the EU was the second largest trading partner after China and the largest investor in 2014. So, as the EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström states: ‘Southeast Asia has been very high in the EU’s trade agenda for decades now’. 1

In recent trade policy documents, the EU has presented an ambitious liberalization agenda that aims at market opening, especially in emerging markets, through the launch of negotiations for ‘deep and comprehensive’ FTAs. ASEAN countries are a priority for these new generation FTAs which are chosen on the basis of economic motivations including market potential and protected-market criteria. In 2007, the EU launched FTA negotiations with ASEAN, but negotiations dissolved in 2010 because of the EU’s comprehensive approach that its FTAs include classical trade liberalization (e.g. traditional border barriers to trade: import tariffs and quotas); WTO-plus liberalization (investment, procurement, intellectual property rights) and developmental issues; and disputes over human rights, especially the Burmese human rights problems.Reference García 2 – Reference Petersson 5 Other reasons include ASEAN’s lack of common negotiation machinery, and the wide discrepancy in economic performance among its members.Reference Lim 3 These bi-regional trade talks were replaced with bilateral negotiations with the most advanced economies in ASEAN which are hoped will serve as foundation blocs on which to upgrade to the region-to-region FTA. Negotiations with Singapore and Vietnam concluded in 2013 and 2015, respectively, and Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines are presently involved in such talks with the EU.

In the new generation of FTA with ASEAN, the EU’s underlying idea is to include its sustainability principles so that ‘trade supports environmental protection and social development’.Reference Cuyvers, Chen, Goethals and Ghislain 6 In doing so, the EU aims to use a trade policy as its leverage for diffusing normative objectives of international labour and environment norms. However, the EU’s ability to ‘shape the conceptions of the normal in world politics’Reference Manners 7 depends on outsiders’ ‘cognitive prior’,Reference Acharya 8 i.e. an existing set of indigenous ideas, belief systems, mindsets and norms, rather than solely on its own rhetoric. This paper argues that intrinsic factors of ASEAN may affect the EU’s credibility as a norm-exporting entity through trade.

This paper first outlines how normative values including labour rights and environmental sustainability evolved in the EU’s external trade policies. In this section it is illustrated that as a policy entrepreneur in terms of labour standards, decent work, and environmental sustainability, the EU aims to promote these ‘universal values’ through its external trade policies. ASEAN viewpoints on the trade-labour/environment linkage are outlined in the subsequent section. Finally, the EU and ASEAN’s divergences on the trade–development nexus raised in the FTA negotiations are discussed. By doing so, this study seeks to assess critical external resistance to EU attempts at linking its trade policy with those developmental issues that weaken the EU’s normative power. To this end, the EC’s discourses, ASEAN countries’ official documents and data from the leading newspapers in Southeast Asia (e.g. New Strait Times Online, The Borneo Post Online, The Straits Times, The Brunei Times, VietNamNet, The Saigon Times, etc.) have been examined. Moreover, several interviews have been conducted to add deeper understanding.

A Linkage between Labour Rights/Environment Standards and Trade Policy: Normative Trade Power Europe

Scholars debating the role of the EU in the international system see the EU as wielding a normative power that is essentially based on the force of ideas and values to ‘change others through the spread of particular norms’.Reference Diez and Manners 9 The EU’s trade is seen as the very heart of such potential or actual normative power.Reference Meunier and Nicolaïdis 10 The EU states that its trade policy ‘is conceived not only as an end in itself, but as a means to promote sustainable development’ principles, particularly core labour standards and environmental norms. 11 In this regard, the EU always connects its ‘non-trade’ objectives to its trade agreements, preferably by integrating non-trade provisions into such agreements. Here, ‘linkage is almost invariably defined by the literature as a provision in the bilateral or multilateral trade system allowing for the use of trade policy instruments, such as import bans, quotas, tariffs and embargoes, to enforce non-trade standards abroad.Reference González Garibay 12 The use of trade to achieve non-trade objectives reflects the EU’s ambition to play a significant role in ‘harnessing globalization’ in accordance with its interests and values.Reference Meunier and Nicolaïdis 10

The principle of sustainable development has become an important component of EU external action since ‘Towards a global partnership for sustainable development’ was adopted in 2002. International labour and environment standards are also part of the EU’s acquis communautaire. The 2008 Lisbon Reform Treaty incorporated developmental objectives in the trade articles guiding trade deals with other partners. The principle of consistency between different areas of external action mentioned in Art. 21 of the Lisbon revised TEU (Treaty on European Union) implies that the EU has to take into account both the economic liberalization agenda and other foreign policy principles (i.e. human rights, fundamental freedoms, solidarity, the rule of law, democracy, and sustainable development) in formulating its commercial policy. This article stresses that the ‘Union’s action on the international scene shall be guided by the principles which have inspired its own creation […], respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter and international law.’ Also, Art 207.1 of the TFEU (Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union) attaches the requirement that the EU’s common trade policy ‘shall be conducted in the context of the principles and objectives of the Union’s external action’. Despite giving priority to trade liberalization and competition, the 2006 Global Europe Strategy still underlines the EU’s commitment to the promotion abroad of its own developmental norms: ‘we should also seek to promote our values, including social and environmental standards and cultural diversity, around the world.’ 13 This position is reiterated in the post-‘Global Europe’ policies: ‘we are committed to promoting sustainable development, international labour standards and decent work.’ 14 The EU’s new trade and development strategy issued within the post-crisis context indicates ‘concrete ways to enhance synergies between trade and development policies’. 15

These objectives have been incorporated into the EU’s trade activities at unilateral, bilateral and multilateral levels. Its unilateral trade preference programme of GSP (Generalized System of Preferences), applied since 1971, provides further evidence of an evolution in the approach of the EU to labour and environmental integration. The GSP is consistent with WTO rules and conditional upon compliance with core labour rights, ILO conventions and multilateral environmental agreements (‘social’ clause). The EU’s GSP grants certain products imported from beneficiary countries either lower tariffs or completely duty-free access, and suspends incentives if beneficiary countries violate these standards. The GSP scheme for 2001–2005 was the first to contain an arrangement specifically dealing with environmental matters, with a focus on deforestation elaborated by the International Tropical Timber Organization. This limited GSP environment has been extended to a more systematic approach by integrating a selected number of MEAs for the period 2005–2011, until today.Reference Durán and Morgera 16 The EU position and policy at the WTO has also shown the linkages between trade and labour/environmental issues.Reference Bretherton and Vogler 17 , Reference Orbie 18 The EC’s first Communication on Trade and Environment was adopted in 1996, affirming that an active participation of the EU in these international trade forums was ‘essential’ and called for the environmental integration requirement (Ref. Reference Durán and Morgera16, p. 48). The EU was also a principal advocate of the inclusion of environmental issues into the agenda of the 2001 WTO Ministerial Conference at Doha that has raised the close relationship between trade and the environment.

Recently, the EU has tried to apply a more ‘homogeneous approach’Reference Bossuyt 19 to the social sections in the prospective bilateral FTAs as indicated by Directorate General for Trade (DG Trade).Reference Mandelson 20 This implies that in such FTAs the EU first aims for recognition of sustainable development as a general objective of the parties (Ref. Reference Bossuyt19, p. 704). Second, alongside Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures and Technical Barriers (TBTs) to trade that contain environmental aspects, the EU aims to further the concept of sustainability through the inclusion of social and environmental sustainability provisions in a separate chapter. Finally, the Union adds provisions committing the parties to evaluate the potential political and socio-economic impacts of FTAs on the EU and partner states through the instruments of Trade Sustainability Impact Assessments (TSIAs). The commitment of the EC to undertake TSIA is commendable as an innovative instrument to ensure an integration of sustainable development both in the definition and implementation of EU external trade (Ref. Reference Durán and Morgera16, p. 249) in spite of the informality of ex ante TSIAs. The Cariforum Agreement and FTA with Korea (2011) were the first trade agreements to include commitments to sustainable development in the preamble, and specific chapters on environment and labour-related issues.

In the same vein, the EU demonstrates its ambition to integrate the environment and labour chapter into future FTAs with ASEAN countries. In detail,

such a chapter should […], contain provisions on core multilateral labor standards and the decent work agenda including in areas where core ILO conventions are not yet ratified; […] incorporate common commitments to multilateral environmental conventions and sustainable fisheries; […] contain provisions with respect to upholding levels of domestic legislation and may include more specific language on the sustainable management of natural resources. 21

This approach has complicated FTA negotiations, and stands in sharp contrast to the Chinese FTA approach (Ref. Reference García2, p. 501). The Commission insists that development-related provisions will be non-binding and are driven by a soft, incentive-based approach instead of by trade sanctions (Ref. Reference Bossuyt19, p. 716). The FTAs negotiated with Singapore (EUSINGFTA) and Vietnam (EUVFTA), which have been described as models and templates for future negotiations with ASEAN countries, indeed contain a comprehensive chapter on trade and sustainable development aiming at ensuring that trade supports environmental protection and social development and promotes the sustainable management of forests and fisheries. At the time of writing this paper, it is too early to assess exactly the status of the sustainability clause because FTA negotiations with Malaysia and Thailand have not yet been concluded, and the EUSING FTA and EUVFTA have not yet been ratified by the European Parliament and Member States. Nevertheless, these FTAs have highlighted both the EU’s insistence on extending international worker rights of the ILO and environmental standards of MEAs, and also the continuity in the EC’s approach to sustainable development as referred to in its TSIA.

Labour Rights and Environment Standards in ASEAN Trade Policy

International trade has been an engine of economic growth for ASEAN’s members since its foundation in 1967.Reference Hanouz and Geiger 22 ASEAN states are increasingly active in pursuing FTAs with non-regional counterparts, especially since the global economic crisis of 2008–2009, which is regarded as a reminder of the important role trade plays in economic prosperity. The FTA strategy benefits ASEAN member states in terms of market access and domestic market reform. The essential view of ASEAN governments is to strongly commit to free trade by standing firmly against protectionist measures, while resisting new non-tariff barriers to enhance economic growth and investment in the region.Reference Purugganan 23 This idea guides their FTA strategy in which references to the labour and environmental issues in both regional and national trade policies are very weak.

Trade and Environment

In Southeast Asia, concerns about the environment have emerged later and slower compared with concerns on security or economic matters, and they tend to focus on environmental problems directly affecting living conditions and health (e.g. urban air pollution, access to safe drinking water), rather than broader environmental issues such as global warming and biodiversity.Reference Bøås 24 In addition, ASEAN has focused on programmatic cooperation rather than adoption of formal, easily cited legal instruments requiring environmental protection.Reference Lian and Robinson 25 On a national level, although various environmental laws and regulations have been enacted, the institutional capacity for developing, implementing and enforcing existing regulations and laws is limited.Reference Bøås 24 Indeed, most ASEAN governments appear to believe that too much emphasis on environmental issues and policies could threaten their goal of economic growth.Reference Ibitz 26 Rather, their attitude has been one of ‘grow now, clean up later’.Reference Bøås 24 More recently, with the rapid economic growth, and rising industrial production fuelled by the liberalization in trade and investment putting increasing pressures on their environmental policies, ASEAN’s concern for the environment of its member countries has increased. ASEAN leaders started to express their concern with climate change in their declarations to the 2007 Bali UN Climate Change Conference, and in a Joint Statement to the December 2009 Copenhagen UN Climate Change Conference. The ASEAN Vision 2020 calls for ‘a clean and green ASEAN’ through protection of the environment and the sustainable use and management of natural resources.Reference Letchumanan 27 Yet, in fact, little has been done to do this because concerns about the environment have not been prioritized in most ASEAN countries.Reference Dosch 28 Therefore, environmental regulations have been ineffectively designed and not well implemented in these countries, particularly countries with relatively low economic development (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam). This shows their weak political will in balancing economic and environmental considerations and turning environmental programmes into concrete action.

Regarding the trade-environment nexus, the core of the ASEAN position remains that ‘national competitiveness is the single most important concern for trade, and not global commons like ozone depletion, climate change or endangered species’ (Ref. Reference Bøås24, p. 50). ASEAN policymakers still view this linkage with concern. So far, at international trade forums the main response from ASEAN has been that the trade-environment nexus should not be included in the WTO agenda and trade agreements. In the WTO’s debates on this issue, ASEAN nations have criticised developed countries such as the EU and the US for being hypocritical. They argue that the latter’s efforts to raise environmental standards in developing countries is driven by increased unemployment at home, and the intention to blame this problem on the unsound exploitation of the environment in developing countries, rather than by environmental concerns (Ref. Reference Bøås24, p. 50). According to ASEAN, its members should strive to protect their local environments for their own sake, but not because they have to adhere to requirements made by trading partners.Reference Azis 29 DoschReference Dosch 30 finds that ASEAN countries have limited political will to mainstream environmental issues that are strongly supported by transnational NGOs and foreign donors into regional trade policy (i.e. at the level of the Secretariat) because they are regularly blocked by individual member states. In this spirit, references to the environment in the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint are very limited. In addition, national environmental policies and standards are mostly an integrated part of a country’s national development strategies rather than trade policy. Similarly, the ASEAN–China FTA puts a great deal of the cooperative efforts on eliminating trade barriers and facilitating more effective economic integration, without provision for cooperation on environmental matters that may originate from trade liberalization. This is also evident in the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum’s plans for trade liberalization among members, and the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) currently under implementation.

Trade and ILO’s Core Labour Standards

The ratification status of the ILO core labour standards varies considerably among the ten ASEAN countries.Reference Gupwell and Gupta 31 , Reference Cuyvers 32 Only three countries – Cambodia, Indonesia and the Philippines – have ratified all eight core labour conventions. Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam have each ratified five. Laos has ratified three and Myanmar two. Brunei Darussalam has only participated in the ILO since January 2007 and ratified two. Singapore has ratified six of eight fundamental conventions. Most member states failed to sign, and even criticized, conventions on the freedom of workers to organize trade unions, child and forced labour, and discrimination in employment.

With regard to the trade–labour linkage, ASEAN reaction to the December 1999 WTO conference was similar to the case of the trade–environment nexus. ASEAN leadership opposed US calls to incorporate core labour standards into the new world trade regime, arguing that they were an attempt to protect US jobs. Rodolfo Severino, the former secretary-general of ASEAN, said that the US and other Western industrialized countries had not complied with the new WTO textile agreement that would allow ASEAN garment exporters greater access to First World markets.Reference Miller 33 The ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint contains no labour standards provisions. In the process of agreeing to set up AFTA, there was very little discussion on labour markets.Reference Sussangkarn 34 This opposition to the trade–labour linkage originates from a general view that freer trade with no labour regulations will bring about greater intra-ASEAN trade and investment flows, enhance ASEAN’s comparative advantage of lower wage production, increase the attractiveness of ASEAN as a destination for large scale foreign investment, strengthen its ability to promote economic development, and benefit the labour force and the population at large.Reference Lanzona 35 On the level of bilateral trade agreements, there has not been much experience of linking trade policy with labour issues in the Southeast Asian region. Even so, there are some exceptions: the US Singapore FTA (2003) provides a comprehensive chapter on labour rights with a commitment to ILO Core conventions. Coverage of labour matters also occurs in the Memorandum of Understanding on Labour, concluded in 2005 in parallel with an Association Agreement (AA) between New Zealand and Thailand, which includes the two countries’ commitments to the ILO and in particular to the 1998 ILO Declaration.Reference Pablo 36 A similar scheme can be found in the Memorandum of Understanding on Labour Cooperation among the Parties to the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership signed by Brunei Darussalam, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore in July 2005.

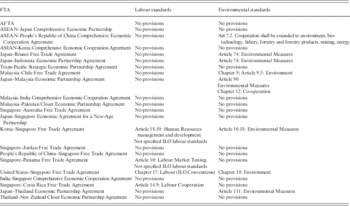

In sum, it can be argued that ASEAN members have hardly any experience of including sustainable development provisions in FTAs. According to the Asian Development Bank database, only six of the 89 ASEAN’s FTAs have provisions concerning labour policy and ten concerning environmental policy (see also Ref. Reference Cuyvers32, footnote 28). There are only four FTAs explicitly referring to ILO core labour standards: the Japan–Philippines Economic Partnership Agreement, the Singapore–Costa Rica FTA, the Singapore–Panama FTA and Singapore–US FTA. Among ASEAN countries, only Singapore has substantial experience with integrating labour rights and environmental standards into trade agreements (see Table 1). In addition, Singapore had made ambitious commitments with respect for core labour standards at the global level.

Table 1 Labour and environmental provisions in ASEAN’s FTA.

Source: Asian development Bank database (retrieved 15 August 2014).

ASEAN Perspectives on the EU’s Incorporation of Social Clauses to FTAs

The Economic Focus of ASEAN’s FTA Strategy

As discussed in the previous section, the guiding economic principle of the ASEAN countries has traditionally been to seek economic growth through further liberalising trade (Ref. Reference Bøås24, p. 53). Indeed, the East Asian ‘tigers’, which have maintained high rates of economic growth for decades, have prominently exemplified the export-led industrialization or export-led growth model. With this model, ASEAN countries struggle to further open up trade in goods and services through bilateral and regional free trade agreements, and undertake considerable reforms in their investment policies at the country level that encourage and give incentives to foreign investments. This affirms that the centrepiece of ASEAN’s approach to economic integration has been a pursuit of preferential trade agreements. The idea of great emphasis on the removal of tariff and non-tariff trade barriers that prevails in the trade agreements indicates that closer ties among larger markets seems to be the mantra of trade policies across the region.

In an attempt to strengthen and develop market relations, ASEAN members hope to boost exports and attract more Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) by signing FTAs with the EU. This suggests that they may have a sharper focus on the economic aspects of the FTA, although other aspects may be considered during FTA talks (Ref. Reference Gupwell and Gupta31, p. 91). It is worth noting that the trade and economic relations between the two regions are asymmetrical, with the EU a much more important trading partner for ASEAN than ASEAN is for the EU.Reference Doan 37 ASEAN’s involvement in the EU’s FTA negotiations could be ‘an opportunity to secure market access in one of its major export markets, […], to enhance competitiveness as well as FDI attractiveness’ aiming at facing competition from China. 38 The EU FTA is expected to increase EU capital sources for ASEAN, and to reduce around 90% of tariff lines on ASEAN’s exports to the EU to zero, while still allowing for carve-outs for swathes of agricultural trade. 39 , Reference Sally 40 Bearing this idea in mind, ASEAN countries do not want to go beyond a pure goods-FTA (Ref. Reference Doan37).

In the framework of current FTA negotiations, ASEAN members have very much relied on economic cost-related arguments to reject the linkage of trade–labour/environment. The first issue is that the EU’s labour/environment standards exceed those standards that the countries already have (Ref. Reference Lanzona35, p. 3). Given their low level of economic development, these standards can be too high for them to satisfy. They do not have enough know-how and modern facilities to comply with and adapt to the international labour and environmental standards (anonymous interviews). Besides, they argue that bringing labour rights and environmental standards into the arena of trade negotiations presents new barriers for exports or a smokescreen for protectionism undermining the trade potential of developing countries (Ref. Reference Lanzona35, p. 3).Reference Hoang, Phung, Tran, Nguyen and Nguyen 41 The fact that the proposal to include a social clause in international trade agreements, with trade sanctions to enforce core labour standards, is being raised by major developed countries such as the EU and the US, is interpreted as being to some extent driven by their protectionist interests (anonymous interview). The Commission indeed admits that ‘in the context of multiplication of bilateral and regional free trade initiatives in South East Asia, the EU has both offensive and defensive interests in forging stronger economic ties with the region’. 42 This argument is fuelled by the fact that, in these FTA negotiations, the EU aims to pursue comprehensive trade agreements covering issues of classical trade liberalization and deep-integration raised by the idea of ‘competitiveness’.Reference Woolcock 43 Arguably, for ASEAN countries, there might be a real danger that the integration of environmental and labour standards into the FTA will emerge as non-tariff barriers rather than as true environmental and social protection measures (anonymous interview). In this regard, violation of these environmental and labour standards could benefit ASEAN partners since they can reduce production costs. Conversely, when labour-intensive products from developing countries are imported into EU markets, in a worst-case scenario social dumping, this could burden EU internal employment and social policies.Reference García and Masselot 44 The attempt to bring these issues into the FTA is thus seen by ASEAN countries as a means to hamper their market access to Europe, and thus undermine their comparative advantage of lower wage production and their ability to promote economic development. Compliance with labour commitments can result in increased costs in the short term, increasing compliance costs, and decreasing the competitiveness of its domestic labour force when compared with foreign labour (Refs Reference Lanzona35, Ref. Reference Hoang, Phung, Tran, Nguyen and Nguyen41, also anonymous interviews). It should be noted that Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam are regarded as the world’s potential ‘low-cost labour alternatives’ in East Asia – in competition with China. Arguably, the EU is widely perceived as presenting a normative agenda in a way that seeks to undermine the competitive advantage of developing countries. For Vietnam, observance of labour commitments in FTAs forces the Government of Vietnam (GoV) to take into account conflicting interests of different interest groups, and confront a significant law-making workload to translate these regulations into Vietnam’s legal system and to issue detailed guidelines, thereby making policy- and law-making procedures more costly and time-consuming (Ref. Reference Hoang, Phung, Tran, Nguyen and Nguyen41, p. 50). In the case of the Philippines, Lanzona arguesReference Lanzona 35 that if these labour standards are included in the Philippine Labour Code, integrating them into a FTA will not lead to distortions. However, additional demands on the part of the EU can cause the dislocation of existing labour market conditions and can increase unemployment in the Philippines (Ref. Reference Lanzona35, p. 3).

With regard to environmental standards, there exists a suspicion of green protectionism among ASEAN countries because of the EU’s strict technical barriers for imports such as environmental certification requirements, and sanitary and phytosanitary standards. The EU–Malaysia FTA negotiations faced such difficulties when discussing the case of the Malaysian palm oil industry mainly because of how palm oil as a biofuel source is evaluated by the EU (Ref. Reference Cuyvers32, p. 25). The sustainability criteria used to assess imports of palm biodiesel into EU markets include greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and biodiversity losses caused by the wanton deforestation for oil-palm plantations.Reference Yean 45 With a GHG emission saving rate of 19% considered too low by EU standards, Malaysian palm oil biofuel fails to qualify for tax credits under the European Renewable Energy Directive (RED). Kuala Lumpur has therefore criticized the RED as arbitrary, even threatening to bring the case before the WTO (Ref. Reference Cuyvers32, p. 25; Ref. Reference Yean45, pp. 9–12).Reference Ching 46 Since the palm oil industry is the fourth largest contributor to the Malaysian economy, it should not come as a surprise that barriers to palm oil trade are a priority issue in the EU–Malaysia FTA negotiations, as noted by the Malaysian Minister for Plantation Industries and Commodities, Tan Sri Bernard Dompok.Reference Ching 47 Both the Malaysian political elites and the palm biodiesel exporters consider that the current findings on palm oil carbon footprint are faulty, and that palm oil is being unfairly assessed in the European markets. The government is thus concerned that EU protectionism is cloaked in a veil of green environmentalism. According to the EC, however, the inclusion of a sustainable development chapter in the FTA will address the environmental challenges Malaysia currently faces (Ref. Reference Cuyvers32, p. 25). Malaysia is a member of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil and should ‘subscribe to the social and environmental criteria it has developed’ (Ref. 21, p. 9). This divergence led to the long break in FTA negotiations after two years of negotiation (2010–2012), and the Malaysian Ministry of International Trade and Industry even said that it would focus on the completion of the TPP talks and only then resume the EU–Malaysia FTA negotiations. 48

For Vietnam, there are hesitancies in accepting the EU’s approach of sustainable development because Vietnamese small and medium producers may meet with numerous difficulties when complying with EU regulations on chemicals, illegal fishing, and the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade Action Plan (FLEGT). The Vice Chairman of the Ho Chi Minh City Business Association said that the European Parliament’s Regulation 995/2010 on timber and timber products and FLEGT’s provisions for legal logging might amount to protectionist measures imposed on Vietnam’s wooden products. 49 According to the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the EU has set up some new requirements on food hygiene, technique and product quality which cannot be satisfied by all enterprises, thereby blocking Vietnamese exports to the EU market. 50

Different Perceptions of the ‘Trade–Development Nexus’

The two parties, EU and ASEAN, have been unable to reach a consensus on the compatibility between trade and social development. The EU sees the inclusion of developmental aspects in the forthcoming AEUFTA negotiations as a way to promote economic development in the Southeast Asian region.Reference Chandra 51 However, for ASEAN, the issue of sustainable development is not appropriate for discussion in the framework of FTA negotiations, because trade is not, and never has been, the cause of environmental and labour problems (Ref. Reference Azis29, pp. 311–312). They see these standards as basically ‘unrelated to trade performance’.Reference Garibay 52 Linking trade arrangements with labour/environmental standards would be equivalent to opening the door to veiled protectionism driven by the fears of relocation held by developed countries’ domestic constituencies (Ref. Reference Garibay52, p. 772). The EU’s trade policy would decrease benefits to countries characterized by high levels of agricultural employment, obstructing their attempts to increase employment in other more productive sectors, and thereby increasing the poverty rate in these countries (anonymous interview). Instead, labour rights and environmental sustainability should be taken into consideration in the framework of development cooperation policy instead of FTAs.

Furthermore, the concept of sustainability through incorporation of social and environmental sustainability clauses of EU FTAs seems to be conceptualized in quite narrow terms as ‘decent work’, ILO conventions, and MEAs. Some of the major EU normative principles such as poverty alleviation, health and education, or discrimination, are not included in the scope of action of the DG Trade and its frame of reference, although some of its actions in the area of trade could affect these matters (e.g. liberalization of health services in FTAs) (Ref. Reference García and Masselot44, p. 197). It is also worth remembering that during the region-to-region FTA negotiations, developmental issues were problematic for both ASEAN and the EU because, according to ASEAN, developmental aspects of an economic arrangement should involve all dimensions of human development, such as physical, mental, technological and infrastructural fields (Ref. Reference Chandra51, p. 73). A former member of the Expert Group on ASEAN–EU FTA, Dr Djisman Simanjuntak, noted that developmental issues are tricky for both ASEAN and the EU (cf. Ref. Reference Chandra51, p. 73). The Indonesian trade minister Mari Pangestu said that ‘Europe wants to have a much more comprehensive coverage of issues like environment [and] labour, which are sensitive for ASEAN countries’.Reference Phillips 53

Political and Cultural-relativist Arguments on the Trade–Labour Linkage

From a cultural-relativist point of view, labour standards can be seen as the products of the historical context, level of development and culture of each country or region.Reference Bhagwati 54 In the case of ASEAN–EU FTAs, some people have confided that many differences of view between the two sides are a ‘question of culture’. A vital pillar of Asian cultural values is ‘communitarianism’ instead of personal freedoms or individualism prevailing in Europe. The Indianized and Chinese parts of Southeast Asia exhibit a collective identity that can be traced back to the Hindu-Brahmanic mandala concept and Confucianism, respectively.Reference Wang 55 The EU’s insistence on promoting historically grown Western standards may appear an imperialistic imposition irrelevant to Southeast Asian conditions and disturb the natural development of society (cf. Ref. Reference Garibay52, p. 773).

More importantly, ASEAN countries’ resistance to EU trade–labour linkage policies stems from their concerns about a veiled attempt to impose neo-colonial political control. Environment and core labour standards are not as sensitive to security and politics as the first and second generation of human rights (i.e. civil–political and socio-economic human rights), and the EC assures that development-related provisions will be driven by a soft, incentive-based approach (Ref. Reference Bossuyt19, p. 716). However, ASEAN counterparts are very often reluctant to be lectured on these matters, linking them with national sovereignty (Ref. Reference Cuyvers32, p. 24). ASEAN is premised on core Westphalian norms of national sovereignty and non-interference, which are determined by aged-honoured collective identities and shared historical experience of the colonial period (Ref. Reference Acharya8, Ref. Reference Wang55).Reference Jetschke and Murray 56 These norms are central to ‘the ASEAN way’, and explicitly guide its regional and international relations. Internationally imposed labour standards would curtail a country’s freedom to choose freely its local policies, constituting an impingement on the country’s national sovereignty from a legal point of view (Ref. Reference Garibay52, p. 772). In this respect, the trade–labour nexus is regarded by ASEAN as a reflection of ‘export of Western ideology’, which creates economic or political constraints, and subsequently threatens the legitimacy of the political regimes in the ASEAN region. This argument is fuelled by the fact that most ASEAN countries have not ratified the ILO C.87 Convention concerning Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise, which concerns the first generation of human rights, or political and civil rights. Three countries (Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam) negotiating bilateral FTAs with the EU have ratified the least number of core human and labour rights conventions that are regarded as a principal legal basis for sustainable development mentioned in EU trade agreements. Even in Vietnam, the ILO C.87 and 98 on the rights to association and collective bargaining are not included in the national Constitution, which leads to a legal challenge for an incorporation of the ILO C.87 and 98 into the FTA. Arguably, the EU will probably also be confronted with occasional reluctance from its counterparts to agree with the general ‘philosophy’ and content of specific conventions (Ref. Reference Cuyvers32, p. 23).

Practically, these divergences not only cause region-to-region FTA negotiations to stagnate, but also prolong bilateral FTA negotiations with individual ASEAN countries. Despite ‘the more developed an economy, the more applicable the EU experience’ (Ref. Reference Jetschke and Murray56, p. 187), even Singapore, the most developed state, prolonged FTA negotiations because of systematic opposition to the incorporation of sustainability clauses in the agreement (cf. Ref. Reference García and Masselot44, p. 202; Ref. Reference Doan37). Significantly, signing a Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Partnership and Cooperation (FA) with the EU (or agreeing to do so in the future), which is the political framework of the relationship, setting normative commitments of human rights, sustainability, and cooperation for anti-corruption, peace and security, is a prerequisite to an FTA. Yet, when the negotiations with Singapore concluded in December 2012, no announcement was made on the conclusion of an FA that was being negotiated alongside the FTA (Ref. Reference García and Masselot44, p. 202). FTA negotiations with Malaysia commenced in 2010 but could not be concluded within 20 months as planned. 57 In addition, Vietnam was hesitant to incorporate this issue in the framework of FTA negotiations (anonymous interview). In earlier FTA talks, some Vietnamese policy-makers said that Vietnam could not accept this requirement. 58 , Reference Hoang 59 A Former Minister of Trade, Truong Dinh Tuyen, claimed that the EUVFTA could be signed in the beginning of 2015 if Vietnam resolved its differences with partners on the establishment of labour unions and privileges extended to state firms. However, FTA negotiations only concluded in December 2015. As a one-party country, there is a single national trade union organization (VGCL), which has official links with the ruling Communist party (CPV) as referred to in the Vietnamese Labor Code. Observance of standards such as required by the EU can interfere in Vietnam’s legislation and political stability and undermine the conventional strategic ‘relationship’ between the Communist party and the labouring class – the crucial component in building the successful governance and leadership of the Party according to the Marxist and Leninist ideology of the CPV (Ref. Reference Hoang, Phung, Tran, Nguyen and Nguyen41).

Conclusion

The EU promotes itself as the Normative Power in world politics and aspires to lead the global debate on social and environment sustainability. This study demonstrates that the countervailing factors coming from ASEAN states have challenged the EU’s normative aspirations. The linkage of these non-trade issues with trade is a sensitive and controversial issue for many ASEAN countries. Their resistance originates from the position that EU demands would not only hurt ASEAN’s economic interests, but also undermine their political stability. The predominance of the economic view was the most salient point in the response of the developing countries’ statements against the use of labour and environmental standards to appease domestic constituencies (Ref. Reference Garibay52, p. 769). Most ASEAN countries are still developing countries with a high rate of poverty, and thus they prioritize economic growth over social objectives in their trade policy making and FTA talks. In this regard, they fear that FTA labour and environmental commitments reveal a new form of protectionism and therefore threaten their market access to Europe. Also, because ASEAN has strictly followed the principle of non-interference in member states’ domestic affairs, external efforts to affect such policies and standards are seen as infringements on the national sovereignty of the association’s member states. This behaviour is prominent because the EU has implemented quite effectively the ‘incentive-based’ approach through trade-related assistance in Southeast Asia. 60 , 61 and just focused on its ‘soft’ approach to social provisions in FTAs. These divergences, originating from their different political, socio-economic and cultural backgrounds, not only cause region-to-region FTA negotiations to stagnate, but also prolong bilateral FTA negotiations with individual ASEAN countries.

Acknowledgement

A first draft of this paper was presented at the 44th UACES conference in Cork (Ireland) in September 2014.

Hoang Hai Ha is a Lecturer at Hanoi National University of Education (Vietnam). She earned an MA in European Studies from Maastricht University (the Netherlands), and a Joint Doctoral degree at the Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies (Italy) and Ghent University (Belgium). Her current research focuses on EU-ASEAN relations, and on Vietnam’s foreign relations.