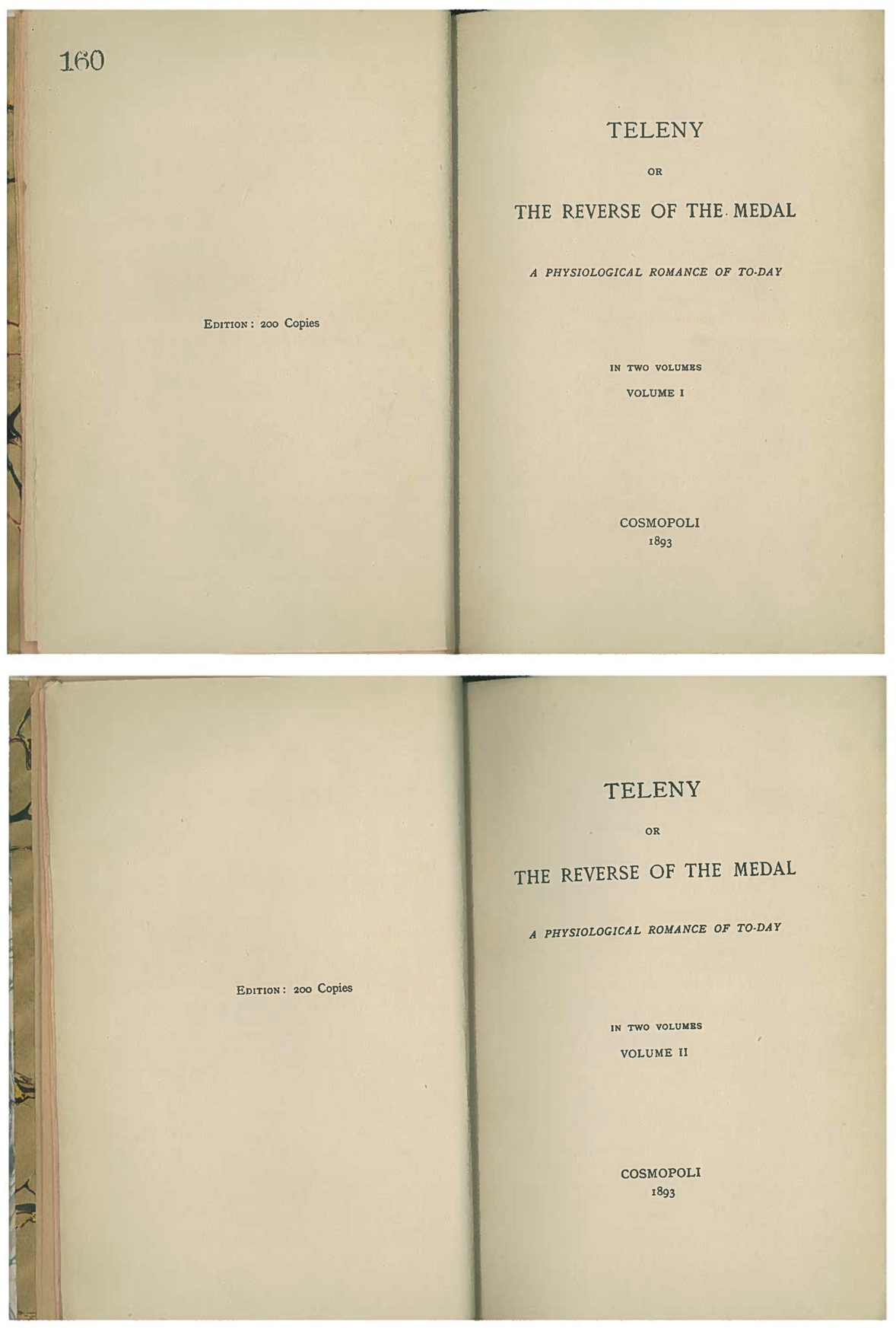

In the words of its London-based publisher, Leonard Smithers, Teleny, or, the Reverse of the Medal: A Physiological Romance of To-day (1893) “may truthfully be said to make a new departure in English amatory literature.”Footnote 1 Set in late nineteenth-century Paris and issued from the fictitious locale of “Cosmopoli,” Teleny appeared anonymously in two volumes in a limited edition of two hundred copies and sold for around five pounds, an expensive price that strongly suggests it was directed toward an exclusive readership.Footnote 2 The tragic love story of two men, Camille Des Grieux and René Teleny, the novel opens in the midst of a conversation between Des Grieux and an unnamed male interlocutor, who interrupts their intimate chat and asks, “tell me your story from its very beginning.”Footnote 3 From its outset, then, Teleny is structurally predicated on inaccessible and yet desirable antecedent narratives: those stories outside of, and leading up to, the one we are about to read. Long after this opening in medias res, the sexual chronicle culminates in Teleny's suicide, and the novel concludes with Des Grieux's teasing promise to reveal further stories to his interlocutor (and to us) on the condition that such revelations are deferred to “some other time” (Teleny 2:191). It is high time, I think, to reevaluate some of the stories that get told frequently about Teleny, and a good place to start is by assessing its complex relation to the little-known 1899 prequel, Des Grieux (the Prelude to “Teleny”), of which only three copies are extant.Footnote 4 I tell three stories about Teleny and Des Grieux's origins here: one about authorship, one about publishing history, and one about sexual etiology. Taken together, they elaborate the possibilities of queer bibliography, which brings the insights of queer theory to bear on book-historical scholarly inquiry and works to trouble, estrange, and queer some of the field's prevailing assumptions.

For a narrative so preoccupied with origins and causes, it should not be a surprise that, for many commentators, Teleny represents the point of departure for an entire literary lineage. Neil Bartlett has dubbed it “London's first gay porn novel,” following the editor John McRae, for whom Teleny is “the first gay modern novel.”Footnote 5 Teleny is certainly not, of course, the first pornographic fiction to depict sex between men. However, it is arguably the first such text whose plot is anchored by an explicit, male-male love story that reflects the Foucauldian model of homosexuality as a modern and identitarian phenomenon. Indeed, for historian of pornography Lisa Z. Sigel, Teleny is “one of the first pornographic novels to explore homosexuality as an identity rather than a practice.”Footnote 6 The story of Teleny, as a book, is thus a familiar one in modernist literary history, wherein a text notorious for its representation of sexual themes—The Well of Loneliness or Lady Chatterley's Lover, for instance—forges new links between the category of the pornographic (or obscene) and a nascent modernity.

Teleny's importance in the genealogy of homoerotic writing in English—indeed, its uniqueness—has long been traced to Oscar Wilde's putative role in its creation. Such an attribution, variously casting Wilde as single author, collaborator, or overseeing editor, has only reinforced its status as a foundational text in gay literary history.Footnote 7 The 1984 Gay Sunshine Press edition and the 1986 Gay Men's Press edition make direct attributions to Wilde, and both feature images of Wilde on their front covers. The logic of attribution seems uncomplicated: since Teleny is a “gay first,” and a clandestinely published vestige of fin-de-siècle decadence, it follows that its era's most (in)famous queer writer—Wilde—must have had a hand in it. Indeed, the most frequently recounted origin story for the novel was put forward by the French bookseller and publisher Charles Hirsch, who claimed in the prefatory “Notice Bibliographique” to his 1934 French translation of the novel that the (now lost) manuscript circulated in 1890 among several hands under the supervision of “a gentleman of forty years, fairly podgy, with [an] absolutely beardless face of matte paleness, slightly swollen, and who wore on his wrist a row of thin gold bracelets garnished with colored stones.”Footnote 8 The figure conjured here is of Wilde as a decadent, effeminate queen, and the site of these exchanges, according to Hirsch's gossipy “Notice,” was his own French-language bookshop in London.Footnote 9 The argument for Wilde's involvement has proven far from universally persuasive, however. Dismissing the attribution, Jason Boyd suggests that Teleny's explicit homoeroticism should not be uncritically conflated with reconstructions of Wilde's sexual identity. “Wilde's involvement with Teleny,” he writes, “is one of the many appealing fictions that make up the construction of the ‘gay’ Wilde.”Footnote 10 In the absence of any conclusive manuscript evidence, what should we do, then, with the novel's persistent ties to Wilde in the cultural imagination?

For the moment, I wish to put aside this story about authorship in order to sketch out two other generative (and related) contexts for the novel—clandestine publishing and sexology—that the name “Oscar Wilde” may otherwise obscure. In the first pursuit I follow Robert Gray and Christopher Keep, who understand Teleny's origins in terms of its writers’ collaboration. As “the work of a community as opposed to an ‘author’ in the proper sense,” the text disrupts unitary identities and categories; for them, to read Teleny as Wilde's work is “to affix its polyvalence, its many voices and multiple desires, to the name of [a] single author and, in so doing, foreclose its being read as an interrogation of individualism as such.”Footnote 11 Colette Colligan reaches a similar conclusion about Teleny, although from a different angle. Attending to the marginal and mysterious literary world of clandestine Anglo-French erotica, she observes that the novel “emerged within a loose network of booksellers and publishers who specialized in a clandestine book trade in a small area in the heart of London notorious for its sundry peccadilloes and its fin-de-siècle cultural streams of past and present, old and new media, fantasy and reality, French and English, heterosexual and homosexual.”Footnote 12 Teleny originates not only from the crucible of international and intercultural literary systems and exchanges, but also from the cross-channel sexual culture those exchanges produced. In light of this broader international—or, since it issues from “Cosmopoli,” cosmopolitan—context, it makes good sense to regard Teleny, as Joseph Bristow has done, as engaging nineteenth-century medico-legal writing about sexual deviance, in particular the influential theories of the early French sexologist Ambrose Tardieu.Footnote 13 Tardieu's Etude médico-légale sur les attentats aux moeurs (1857), which Bristow translates as “Forensic Studies on Sexual Offences,” provided a prominent account of the pathologized homosexual male body in the second half of the nineteenth century. Bristow elaborates Teleny's defense of the male homosexual body and homosexual sex, which he identifies in the novel's depiction of the healthy “man-loving penis.”Footnote 14 In this reading, the rambunctious eroticism of a novel whose subtitle proclaims it a “physiological romance” stands as a bold rebuke to Tardieu's theories about the “misshapen” and “impotent” characteristics of sexually nonnormative male bodies.Footnote 15

Building on these readings of the novel that emphasize, respectively, sex and community or place, and sex and the male body, I attend to the stress Teleny places on sex and time. I focus on its incessant return to genealogies and sequences and on the impact of these structural elements on how the book, as an artifact in the period's print culture, is situated (and how it situates itself) in time and in relation to its virtually unknown prequel, Des Grieux (the Prelude to “Teleny”). This critically neglected (and mostly unavailable) novel was published in 1899 in Paris by Aimé Charles Emile Duringe (1854–1913), and its authorship remains unknown.Footnote 16 Des Grieux reads as if it could be an extended sexological case study: it recounts the sexual lineage of Camille Des Grieux through several generations. Emerging from a historical moment that witnessed, in Benjamin Kahan's words, “a revolving door between literature and sexology,”Footnote 17 Des Grieux shares sexology's etiological narrative burden in that it is preoccupied with cataloging and assessing the causes of the Des Grieux family's (congenital) sexual irregularities. A far less accomplished production than its counterpart, Des Grieux (the Prelude to “Teleny”) nevertheless makes good on Teleny's numerous hints about storylines set in an earlier time, even though it fails specifically to fulfill the promise Des Grieux makes to his interlocutor in Teleny that “some day I shall tell you the reason why I am an only son” (Teleny 1:[41]). Although the single, 152-page volume of Des Grieux delves deeply into the Des Grieux family's (sexual) past, it brings us forward only into Camille Des Grieux's childhood. This multigenerational adaptation of the familiar nineteenth-century bildungsroman pointedly omits Camille's sexual initiation and experiences in adolescence and early adulthood, thereby excluding events that structure better-known Victorian erotic memoirs such as My Secret Life (ca. 1888). What it offers its readers instead is a nearly literal pedigree of the Des Grieux family's “minor perversions”—a pedigree that establishes the etiology of Camille's homosexuality in his family's bizarre relation with dogs.

As this narrative of sexual etiology suggests, Des Grieux provides provocative and unexpected answers to the vexed question of origins that are inspired as much by Teleny's publishing history as by both novels’ plot trajectories. A sequel that is also a prequel, Des Grieux capitalizes on (and seeks to extend) Teleny's apparent success. Although Peter Mendes avers that “Des Grieux was indeed written by the same hand(s) as Teleny, and possibly before Teleny at that,”Footnote 18 I argue that its appearance six years after the first edition of Teleny articulates a queer textual genealogy for the two novels, situating Teleny in an inverted relation to a prequel that postdates it. Both pornographic texts share a specific preoccupation with a particular aspect of genealogical time, namely its directionality and sequencing. In their plots as well as in the bibliographic relation that obtains between them, Teleny and Des Grieux inhabit a queer temporality: a chronology or temporal sequence that moves backward as much as it moves forward, frustrating unidirectional (and heteronormative) progression and linearity, a temporal mode that Elizabeth Freeman dubs “chrononormativity.”Footnote 19 I find especially useful for comprehending these novels what Freeman calls the queer “stubborn lingering of pastness.”Footnote 20 Des Grieux, for example, retrospectively assembles—catalogs—the diversely deviant episodes in Camille Des Grieux's family history, moving toward a homosexual future that is narrated in Teleny and which will inescapably recall in that novel the family's ancestral past.

In reading these texts in terms of queer time and queer sequencing, I also follow the lead of Annamarie Jagose, whose theorization of “the logic of sexual sequence” provides a powerful framework for thinking through Teleny and Des Grieux's sexual and textual genealogies. For Jagose, “the organization of first and second naturalizes chronology as hierarchy”: this organization places nonheterosexual identities in a secondary or inferior position with regard to the assumed primacy of heterosexual ones.Footnote 21 Depending on how we read the bibliographical evidence that configures the sequencing of these novels, either Teleny or Des Grieux (as the “parent” text) could be consigned to the secondary, belated position of the sequel (the “child” text). In unfolding the sequencing logic of Camille's (sexual) past—however incompletely—the retrospective positioning of Des Grieux vis-à-vis Teleny reflects this understanding of sexual identity's sequential constitution at the level of the material book. But it also disrupts the matter of hierarchization, since we cannot name which novel is the parent or the child. If we adapt Victorian sexological terminology for same-sex desire in order to imagine a way for thinking queerly about the genealogical time of these novels, then Teleny and Des Grieux exist in a distinctly inverted sequence. Teleny can thus be said to be queerly generative in that it engenders an origin for itself that is realized in its own prequel, Des Grieux (the Prelude to “Teleny”).

Authorship as Origin in Teleny

In the absence of a definitive authorial candidate for either novel, I want to propose that the Oscar Wilde attribution functions as a kind of shorthand solution to the bibliographical enigmas Teleny and Des Grieux present. Authorial speculations remain important features of both books’ histories, as they provide these textual orphans with an ancestry that affirms their grouping within the newly hardening categories of homosexuality and obscenity that Wilde came to represent after his trial and imprisonment in 1895. The attribution of Teleny (and, by extension, of Des Grieux) to Wilde is certainly an appealing item of literary gossip, one that probably began to circulate by word of mouth long before its emergence into print.Footnote 22 Whatever his role in its production, Wilde can't escape Teleny. And it seems that Teleny can't escape Wilde.

In the 1893 prospectus for Teleny, its first publisher, Smithers (who would go on to publish Wilde after the latter's release from prison), does not name Wilde as the author, although we might read an oblique pun on his name in the proclamation that “the novel contains scenes which surpass in freedom the wildest license.”Footnote 23 Sometime between 1903 and 1905 Teleny was advertised in a more outspoken erotica catalog issued by Paris-based publisher and bookseller Charles Carrington.Footnote 24 This advertisement not only borrows the text of Smithers's prospectus,Footnote 25 but also explicitly identifies Wilde as Teleny's author: “We may say that the writer referred to […] is stated on good authority to be no other than Oscar Wilde. This becomes the more convincing when we compare the style of his famous ‘Dorian Gray’ with the present brilliant but awfully lewd book.”Footnote 26 At the intersection of fame, gossip (“good authority”), brilliance, and lewdness, Wilde's name functions here as a sensational mode of advertisement, linking Teleny with The Picture of Dorian Gray—a title memorably described during the author's 1895 trials as “immoral and obscene” and “sodomitical”—which Carrington had exclusive rights to publish since 1901.Footnote 27 As Colligan points out, “there is no evidence to corroborate Carrington's claim that Wilde authored this work. But evidence was irrelevant.”Footnote 28 For Carrington, and presumably for his customers as well, Wilde's reputation as a sexual outlaw and a writer of notorious books—a defining aspect of his fame by the 1900s—makes the attribution not only plausible but also extends the commercialization of that fame.

The Wilde attribution appeared again at irregular intervals in the 1910s and ’20s. Its purveyors included Aleister Crowley, Bernard Shaw, and Wilde's son Vyvyan Holland.Footnote 29 In each of these gestures of attribution, Wilde's putative involvement with Teleny reflects a well-known aspect of his personality and sexual legend. These origin stories all converge at the figure of the gay Wilde, where certainties about the sexual realm (Wilde's life) would seem to confirm speculations about the textual one (his writings). For my purposes, however, the question of Wilde's authorship of erotica (did he? / didn't he?) ultimately matters far less than the fact that by at least the 1920s, Teleny is indelibly associated with his name in literary lore.

Wilde's configuration as the point of Teleny's textual and material origin even preoccupies accounts of its history that emphasize the collective over the individual author. As we have seen, the story of Teleny's production by a community of writers associated with Wilde originates with Charles Hirsch, who characterized the text as a “bizarre assemblage issuing from various imaginations.”Footnote 30 Hirsch republished Teleny in 1934 in a private printing of three hundred copies, stated to be not for sale but instead produced for the edition's subscribers and therefore beyond the reach of punitive legal strictures against obscenity. These select, and probably imaginary,Footnote 31 readers are described as members of the homophile “Ganymède Club” of Paris, to whom Hirsch, as “president” of the club, addresses an obsequious prefatory letter. Attuned to his customers’ demand for a text “si longtemps désiré, si longtemps attendu” (longingly anticipated for such a long time),Footnote 32 Hirsch may very well be telling this audience what he thinks they want to hear: a story about Wilde and a late-Victorian homosexual subculture that envelops and exceeds Teleny's plot. The prefatory matter in Hirsch's edition has proven formally influential to Teleny's presentation in print: in his and every subsequent edition of the novel, the backstory behind Teleny, and Wilde's alleged role in its composition, precedes and even takes precedence over the story of René Teleny and Camille Des Grieux. Teleny has thus become as much a sociohistorical document about the history of homoerotic representation as it is a fictional, literary text—or what Smithers had called “a new departure in English amatory literature.”Footnote 33 By the logic of literary history, a Wildean context has overwhelmed the novel's queer content.

In addition to aligning the novel suggestively with Wilde in his “Notice,” Hirsch situates Teleny within a sequence of documents arranged in chronological terms—a porn archive, in other words. Not only does he place Teleny and its lost manuscript in real time in the “Notice Bibliographique,” but he also equips the text's fictional world with yet another origin narrative. In the 1934 printing, the “Notice” is followed by an “Avant-propos” or prologue, a paratext absent from the 1893 first edition, which Hirsch claims was omitted by Smithers. This “Avant-propos” opens the story in the voice of the unnamed narrator recounting his acquaintance with Camille Des Grieux, whom he finds dying of tuberculosis in Nice. It is conspicuously dated “Juillet [July] 1892,” thereby conveniently dating the narrator's recollections to a historical moment a few months prior to the first publication of the novel. In this prologue, the narrator takes pains to insist that the recollections contained in the pages of the novel constitute a true story, “une histoire vraie, la dramatique aventure de deux êtres jeunes et beaux, d'une nature raffinée” (the true and dramatic story of two good-looking young men of refined temperament).Footnote 34 The story of Camille Des Grieux's relationship with René Teleny comes newly into focus as a deathbed confession, and the “Avant-propos” supplies a suitably tragic narrative frame for a tale that also ends with René Teleny's own death. With its accretion of prefatory documents, Hirsch's 1934 edition proffers multiple (not to say competing) origin stories: we get not only the history of where Teleny—the book—came from, but also the metafictional history (or fate) of its main character, Camille Des Grieux, in a prologue that unsettles the boundary between fiction and material fact.Footnote 35 And in the aggregation of these documents and time lines, with their attention to origins and deaths, the question of authorship and the name of Oscar Wilde blend with and engulf narrative content. But a turn from the specific (and somewhat limiting) context of gay literary history to the material and ancestral contexts of Teleny and Des Grieux allows us to assess these novels in terms of queer sequencing and bibliography. Such an approach reveals how the (bookish) child is indeed the father of the man.

Decoding Queer Temporality in Des Grieux

Hirsch's “Avant-propos” fleshes out the fictional biography of Camille Des Grieux, neatly tying up the loose ends left at the conclusion of Teleny. But nowhere amid these tangled accounts of narrative origins do we find a mention of Teleny's putative prequel, Des Grieux. Indeed, judging from the paratexts that delay and condition a reader's entry into the world of Teleny as presented by Hirsch in 1934, the bookseller and editor would seem to be entirely unaware of its self-declared 1899 “Prelude.” Given Hirsch's extensive contacts in the publishing world of clandestine erotica, the apparent ignorance of Des Grieux on the part of a publisher who styles himself “un vieux bibliopole” (an old bookseller) seems undeniably strange, even mildly suspicious. To put it another way, if Hirsch is so uniquely well informed about Teleny's past, why does he refrain from discussing that novel's literary progeny? Hirsch's “Notice Bibliographique” even describes Des Grieux's publisher, Duringe, whom he names as the keeper of the lost Teleny manuscript, as a mutual friend or “ami commun” that he shared with Smithers. And yet he omits to mention Des Grieux. Colligan meticulously details Hirsch's encounters with both Wilde and Smithers at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, the year after Des Grieux's appearance, and if either Wilde or Smithers had anything to do with Duringe's 1899 publication, it seems unlikely that Hirsch would not have known about it.Footnote 36 But if Hirsch did indeed know about the existence of Teleny's prequel, he appears to be suppressing that knowledge in order to enhance the credibility of his own (incomplete) version of Teleny's history. As Jason Boyd observes, “accepting Hirsch's account is a matter of faith: one must simply trust that Hirsch is telling the truth.”Footnote 37 But then again, why should he necessarily tell the truth? Again, according to Colligan, Hirsch loved mysteries, and he adopted a playful approach to his erotic publishing endeavors, “exploiting the thrill of secrecy” to the extent of printing densely encoded colophons in certain books.Footnote 38 Des Grieux represents a mystery entirely out of his control, and its emergence for scholarly analysis marks a significant intervention in the literary history of Teleny, for it retroactively reconfigures all of the origin stories that Hirsch is at pains to promote. Des Grieux (the Prelude to “Teleny”) compels us to rewrite the histories of both novels by attending to the queer sequencing that links them.

Des Grieux significantly complicates Hirsch's account of Teleny's genesis. Although this prelude supplies a genealogical prehistory for that novel's central character, Camille Des Grieux, it fits awkwardly alongside the concerns and commitments of the 1893 novel's narrative, to say nothing of the bibliographical lore that had accumulated around it. We may never know who wrote Des Grieux, or whether it represents the work of a single author, or (like Teleny) a collaboration among several individuals. Wilde is an extremely unlikely authorial candidate, even though the time he spent in Paris between 1898 and 1900 overlaps somewhat with what we know of the novel's (likely) dates of composition and publication. During those years, moreover, Wilde was “disinclined to produce new work,” according to Nicholas Frankel, thereby frustrating his few remaining literary friends and supporters.Footnote 39 Despite its imperfect literary merit, Des Grieux would undoubtedly have constituted such “new work,” and there isn't a single allusion to it in an otherwise well documented and sexually candid period in Wilde's life. Oscar Wilde did not write Des Grieux. Barring a major authorial revelation, we can only sketch out Des Grieux's history by assessing the narrative and bibliographical evidence it affords us. Its author (or authors) had clearly read Teleny with some care, since the 1899 prelude certainly fulfills, in a manner of speaking, some of the earlier novel's narrative and textual prophecies. According to Paul Budra and Betty Schellenberg, prequels can be distinguished from the larger category of the sequel in terms of their temporal orientation toward the past, regardless of when they may have been written: prequels are “works in which the internal chronological relation to the pretext narrative is prior.”Footnote 40 By the logic of both narrative chronology and publication history, Des Grieux is a prequel, since it represents the deferred occasion for erotic storytelling—that “some other time” to be set aside for further disclosures about the past—that Camille Des Grieux promises his interlocutor at the end of Teleny.

In order to conjure a genealogical backstory for Teleny's narrator, Camille Des Grieux, the 1899 prequel draws consistently upon several of its counterpart's recurring motifs. Des Grieux's multiple sex-dream sequences, for instance, echo the 1893 novel's themes of altered erotic consciousness, telepathy, and mysticism. When Des Grieux first sees Teleny performing at the piano (in Teleny), the young Frenchman experiences a hallucinatory erotic reverie in a series of orientalist images moving from Islamic Spain to Egypt to “the gorgeous towns of Sodom and Gomorrah.” These visions culminate in a disembodied autoerotic episode in which “a heavy hand seemed to be laid upon my lap, something was bent and clasped, which made me faint with lust” (Teleny 1:15).Footnote 41 Teleny soon reveals that he and Camille have experienced “the same vision at once,” thereby establishing Teleny's figuration of erotic attraction as akin to telepathy and magnetism (Teleny 1:31). In the first episode of Des Grieux, during a similarly specular and dreamlike erotic encounter, an unnamed young man desirously watches, and is watched by, one of Des Grieux's female ancestors. When their eyes meet, they also experience a telepathic erotic connection, a “soul-commingling” of which the narrator asks, “was it a contagion of sympathy?” (Des Grieux 23). As in the earlier novel, sexual desire is rendered as a mysterious and overpowering force, and not always subject to human volition.Footnote 42

Although Teleny provides something of a thematic template for the imaginative territory explored in Des Grieux, the actual relationship of one text to the other remains elusive despite the limited—but tantalizing—bibliographical clues that Des Grieux affords. A good place to start decoding Des Grieux and its time lines is with the title page itself (fig. 1). The titular phrase Des Grieux (the Prelude to “Teleny”) foregrounds one proper name while associating it with another. These proper names, which identify Teleny's pair of male lovers, also function as the short-form titles of two discrete books. The placement of “Teleny” in parentheses further sutures the texts together. A gesture of literary affiliation, the parenthetical phrase connects the 1899 novel to a specific, preexisting narrative that the reader is presumed to know intimately and signals the reader's desire to continue to explore the imaginary erotic world first encountered in that earlier novel.Footnote 43 As Teleny had done, Des Grieux indicates its ostensible publication format as a two-volume novel with the statement “VOL. I” on the title page. Neither authorship nor place of publication are given, and the only remaining piece of information provided by the title page is the publication date, 1899.

Figure 1. The title page of Des Grieux (the Prelude to “Teleny”)

None of these paratextual cues would be remarkable if they accurately reflected Des Grieux's actual publication format. Although Teleny, as we have seen, was issued as a two-volume novel, Des Grieux does not fulfill its title page's promise of a second volume. That novel abruptly terminates with the conventional statement “End of Vol. I.” No second volume exists. Judging from the absence of any manuscript evidence and from the incomplete state of the narrative, which breaks off during Des Grieux's early adolescence, it is reasonable to infer that a second volume was planned and never executed. And given Des Grieux’s extreme rarity, it is also conceivable that a second volume was indeed printed and that all copies have either disappeared, been destroyed, or yet remain to be unearthed. Even if a planned second volume never made it into print, the shoddy design of the surviving single volume strongly suggests that the publisher, Duringe, and his printers simply published the material they had to hand—however limited or incomplete. They likely did so hastily, and as cheaply as possible, without affording the book the care and attention to design matters that Smithers lavished on Teleny. Finely printed on laid paper with ornamental initial capitals, in material terms Teleny is an altogether more polished and sophisticated book than Des Grieux.

Duringe was well connected within the Paris-based pornographic book trade, and as Colligan observes, “it is possible that he sometimes operated under someone else's commission rather than solely as an independent publisher.”Footnote 44 Those professional roles and relationships, she notes, could be “precarious,” and we may discern that precarity in the production values that give Des Grieux (the Prelude to “Teleny”) a provisional or incomplete appearance. Of the three extant copies that have been identified, I have only examined the copy at the University of British Columbia Library. Although that copy is no longer in its original binding, many of its physical characteristics testify nonetheless to a less than ideal production process. It is printed, for example, on thin wove paper, and the gatherings have been trimmed in a seemingly haphazard manner to produce pages of startlingly uneven sizes. The typography is faint in several places, and numerous letters are reversed or transposed, suggesting a less than careful setting of type. The book's French origins are underscored by frequent Gallicisms and spelling errors, which strongly suggest that the text's typesetters and printers were not native English speakers. In a novel redolent with decadent Catholic imagery, for instance, the name of the most homoeroticized of saints is rendered with a frenchified hyphen as “St-Sebastian” (Des Grieux 33).Footnote 45

When we compare the information conveyed by the title page with the rest of the book, Des Grieux's further bibliographical prompts prove puzzling and inconsistent. To put it another way, the totality of the bibliographical evidence afforded by the volume is queer. These prompts insistently situate the novel vis-à-vis Teleny in a relation that draws our attention to temporal and sequential logic while concurrently frustrating the directionality of that logic. Mendes states that the single “VOL. I” of Des Grieux represents “all published,” and he asks rhetorically if this state of affairs thereby “impl[ies] Teleny as Vol. II?”Footnote 46 Under this scenario, the two titles represent a narrative unit arranged sequentially along a linear time line. The prelude thus comes first in a narrative teleology that prioritizes the chronology (and linear development) of Camille Des Grieux's ancestry. The temporal end point of this two-novel sequence is thus the homosexual self-discovery Des Grieux experiences through his erotic and tragic relationship with Teleny, and the terminal notice “End of Vol. I” at the closing of Des Grieux would seem to confirm this view by impelling the reader forward in narrative time to the events related in Teleny.

But this is not the only way to interpret Des Grieux's bibliographical prompts, and hence the sequential relation of one text to the other. Des Grieux is a small octavo volume. It carries signature marks on the lefthand footer of pages 17, 33, and 49 (marking three gatherings of sixteen pages), although after that point the signatures abruptly disappear from a volume that runs to 152 numbered pages and terminates with the phrase “End of Vol. I” (fig. 2). The signed pages are ambiguously marked “T. II.” Mendes cautiously interprets this abbreviation to imply that Des Grieux (the Prelude to “Teleny”) represents the “2nd volume of Teleny.”Footnote 47 According to this line of reasoning—which, Mendes acknowledges, runs “contrary to the title page”—if Des Grieux represents “T. II,” then Teleny must be “T. I.” (No such signatures appear in Teleny.) “T.” would thus stand for either “Tome” (the French word for volume) or “Teleny.”

Figure 2. A page from Des Grieux

Following this reading, the title page, signature numbers, and the terminal notice “End of Vol. I” in Des Grieux offer competing and contradictory accounts of the “problematic” sequential relation Mendes describes between the two titles.Footnote 48 If we follow Mendes's interpretation of the title page, amplified by the terminal notice, the two texts are linked in a sequence that puts Des Grieux first. We could call this a narrative or diegetic chronology in which the two novels are related to each other by the time lines and events internal to their fictional world. The signatures, however, point to a bibliographical, or external, chronology that prioritizes the order of publication, wherein Des Grieux (published in 1899), despite its designation as a “Prelude,” functions as “T. II,” a sequel that constitutes a second part to Teleny (published in 1893), albeit one set in an earlier time frame. In this bibliographical analysis, the material textual history of the two novels’ printing and publication sequence takes precedence over the narrative chronology that both relates Camille Des Grieux's ancestry and predicts his homosexual future.

My purpose is not to determine whether these books’ “problematic” relationship is deliberately intended (or not), but instead to highlight how the bibliographical prompts recorded in the pages of Des Grieux situate both books within a queer temporal structure that inverts conventional narrative and material sequencing. In other words, both options that Mendes adduces for understanding the structural relation of the two texts are predicated on a kind of reversal, or backwardness, and both may be happening simultaneously. Either the later-published “Prelude” comes before the ostensibly primary narrative unit known as Teleny (in which case 1899 precedes 1893), or the “Prelude” should be seen as a sequel—“T. II”—that antedates the main text (Teleny) it ostensibly prefaces. In either scenario, that bibliographic relation is one that hearkens backward instead of forward while maintaining the logic of sequencing that obtains between the two novels. The queer sequencing of these books disrupts conventional models of precedence and chronology—and, by extension, one of the most powerful metaphors for the timely order of things: heredity and heterosexual reproduction.

Queer Parentage and Progeny in Des Grieux

What loose narrative unity there is to be found in Des Grieux coheres around the motif of heredity and ancestry. Its episodic plot alternates unpredictably between third- and first-person narration, and unfolds in a sequence of sexual adventures experienced by several generations of the Des Grieux family who are, at times, difficult to distinguish. There are multiple characters with the surname “Des Grieux,” just as there are “Camilles” of both sexes. If Teleny is the “first gay porn novel,” then perhaps the most surprising feature of its prelude is the dearth of overtly homosexual encounters. In point of fact, Des Grieux is scarcely a “gay porn novel” at all: unlike Teleny, it contains no elaborately lyrical descriptions of gay sex. Instead, much of the sex in Des Grieux is configured in terms of female desire for male bodies, and the fulfillment of this desire leads inexorably toward pregnancy. Des Grieux is beholden to the inevitability of what, in a different context, Lee Edelman designates as “reproductive futurism.”Footnote 49 Equipped with a plot structured by the theme of ancestry, multiple generations are thus necessary to get us to the novel's ultimate narrative and reproductive goal: the childhood of Camille Des Grieux—a figure whose homosexuality emerges fully, of course, only in the pages of Teleny. And yet a reader of Des Grieux alert to the queer sequencing of the two novels comes to it with Teleny in mind. Camille Des Grieux's future exists in memory, in his reader's past.

Despite the narrative's hetero-reproductive imperative, male homosexuality is nonetheless an underlying presence in this family story, which is redolent with homoerotic imagery. If Teleny is arguably about Des Grieux's discovery of his own sexual identity, then the prelude that bears his name links together a series of episodes that offer themselves for interpretation as that identity's cause(s). The 1899 novel tacitly takes both sides in the sexological debate over whether homosexuality should be considered acquired or congenital, and its plot figures homosexuality as an ultimate end point or narrative destination, although its full expression is deferred to the story of Teleny. Near the close of Des Grieux, once the child version of Teleny's lover has been introduced to the story, Des Grieux relates two childhood episodes in which other characters seem to have been more aware than he is of his erotic orientation toward other males. In the first episode, a group of working-class adolescent boys taunt him by offering him their penises, and the shame of this memory is so intense it produces suicidal thoughts. (Suicide, we recall, is also a prominent tragic motif in Teleny.) In the second, he is tormented at boarding school with the effeminizing nickname “Mademoiselle,” while other boys mime anal sex with him:

They used to catch me from behind, and clasping me, they began bumping their middle parts against my bum, asking me how I'd like it. Thereupon all would laugh. Of course I did not understand what they were hinting at, but I felt sure that in their words there was some hidden meaning which I could not fathom. (Des Grieux 114)

In childhood, Des Grieux is an innocent who knows less about himself than the possessors of “hidden meaning” who surround him—a group that includes these tormentors as much as the readers of Teleny who are informed about his adult homosexual future. Homosexuality in Des Grieux is therefore configured less by the trope of the secret past than by the promise of the imminent and inevitable future. Far from having no future, the Des Grieux family is awash in queer futurity.Footnote 50

At first glance, the relative paucity of homosexual content in Des Grieux seems inconsistent with Teleny's primary narrative concern of making, as Joseph Bristow puts it, a “constant appeal to the strength of the gay phallus.”Footnote 51 Why, after all, would the book's writer(s) and its publisher take such care to affiliate it with Teleny while avoiding (or diminishing) that novel's celebration of male-male erotic pleasure? Moving from theme to structure offers a helpful way of thinking through the ostensibly heteronormative architecture of Des Grieux. If we understand the structural relationship between the two novels as lineal or generative (and both readings of Des Grieux's bibliographical prompts point toward such a reading, despite being vectored differently), the 1899 novel's genealogical drive toward a queer futurity elaborates and reinforces an understanding of his homosexuality as innate. Des Grieux is an etiological tale burdened with adumbrating the causes of queerness—causes that can only be adduced through an extensive tour of his genealogical past. For as he observes in Teleny, Des Grieux was “born a sodomite,” and the orientation of his desires toward other males represents nothing more than “natural feelings” over which he has no control (Teleny 1:98). With Des Grieux as Teleny's progenitor and its progeny, the (pre)history of “the first gay porn novel” becomes a history of genetically determined homosexuality whose source is the deviant sexual behavior of several generations. And although the supernatural trappings of Des Grieux may push against such a scientistic reading, we could understand the relation (in all senses of that word) between the two novels to be articulating what we might now call the “gay gene.”Footnote 52

The 1899 “Prelude” articulates the logic of inherited homosexuality with a novel—if eccentric—plot device. It accomplishes this narrative task by aligning sexual deviance (including same-sex eroticism, but not exclusively) with dogs—poodles in particular. Anthropomorphized queer poodles abound in Des Grieux. “Were I a believer in the transmigration of souls,” one of the narrators asks early in the novel, “I might conclude that the spirits of sodomites are made to dwell as a punishment in the body of these dogs” (Des Grieux 29). Poodles sniff around the edges of many of that novel's sexual encounters, and they tend to appear at moments when (deviant) sexual desire or enjoyment transcends the boundary between the real world and the dream world.

In Des Grieux, Camille, the identically named grandmother of Teleny's lover, is depicted as a lusty adolescent having erotic dreams about St. Sebastian that are provoked by a persistently lascivious poodle's licking of her vagina. In this sequence, the saint's figurative queerness is aligned with the lustful presence of the male dog, and unconscious pleasure derived from the one is transferred onto desire for the other. Crucially, however, this episode remains cross-gendered (to say nothing of crossing taxonomic categories); its logic is associative, and it does not distinguish between, or give precedence to, particular varieties of deviance. Earlier in the novel, after a male poodle tries to mount her in another trance state, the narrator asks, “what had made the poodle come into her room that evening and make such an attempt of buggery upon her? Was there any bestial affinity between them?” (Des Grieux 38). In light of the narrator's earlier musings on the transmigration of souls from sodomites to poodles, the answer to this rhetorical question must be a definitive affirmative. This “bestial affinity”—not unlike the “secret affinity” Des Grieux shares with Teleny—is something that Camille dimly grasps as standing in the background of his desire for his “own sex” (Teleny 1:[69]). The affinity is, in a sense, in his breeding—and, like breeding, it expresses the genetic transmission of acquired characteristics.

Such scenes seem to have been inspired by Teleny. In that novel, when Camille Des Grieux awakes from a bizarre erotic dream in which he imagines having sex with his sister, the disorienting conjunction of incest-dream and ejaculatory awakening is witnessed by “a loathsome poodle, standing there on its hind legs leering at me” (Teleny 1:45). Poodles are further categorized in Teleny along with “young Arabs” (familiar figures of Victorian sex tourism lore) as being free from misleading (and homophobic?) “wrong ideas” that would condemn same-sex desire (Teleny 1:98).Footnote 53 As he struggles to overcome these “wrong ideas,” Des Grieux's dislike of poodles emerges as nothing more than anxiety about homosexual self-discovery. The poodles that haunted his ancestors and witnessed (or participated in) their various desires and couplings vector his homophobic self-loathing. The details of repeated encounters with “that bugger of a beast” in Des Grieux are humorous and outlandish to be sure, but taken in the aggregate they emblematize Camille Des Grieux's inherited homosexuality (Des Grieux 60–61). These poodles—always male—are the pets of female ancestors in both texts: an aunt of the female Camille in Des Grieux, and the mother of the male Camille in Teleny. In both novels, poodles are the familiars of sexual deviance, where “bestial affini[ties]” cross the human/animal divide. They queer heterosexual sex and reproduction, and they queer its end point. The queer spirit of the poodle is therefore not only transmitted through the generations; along the way, its intrinsic deviance is also transmuted from zoophilia (or canine anthrophilia?) to an internalized, essentialized homosexuality.

In The Book of Minor Perverts: Sexology, Etiology, and the Emergences of Sexuality, Benjamin Kahan argues for “historical etiology” as a “crucial tool … for periodizing and narrativizing what is variously referred to as the invention of sexuality, the birth of homosexuality, the formation of sexual subjectivity, [and] the emergence of the homo/hetero binary.”Footnote 54 This approach enables Kahan to contend with historically specific sexualities and practices that the binaristic model of homo/hetero occludes, such as “the cast of minor perverts that stick around after the initial tentative articulations of the homo/hetero divide.”Footnote 55 Among such perversions, Kahan cites “bestiality, kleptomania, nymphomania, necrophilia, dendrophilia,” and even “sex with statues.”Footnote 56 Kahan's exploration of a historical moment marked by competing understandings of deviant sexuality's causation clarifies this aspect of Des Grieux, for as Kahan says, “I want to retain etiology's cataloguing energies and narrative capacities, particularly its ability to register the contingent and specific conditions of sexuality's production.”Footnote 57 Such cataloging energies and narrative capacities, articulated by highly “contingent and specific conditions” (such as female erotic dreams for queer-coded saints with canine assistance) abound in a novel whose inclusiveness when it comes to imaginative depictions of atypical sexuality is perhaps more than anything what distinguishes it from Teleny—a text far more interested in, as Eve Sedgwick puts it, “the gender of object choice.”Footnote 58 Des Grieux's sexually attentive poodles are minor perverts par excellence.

The co-presence of a multitude of “perversions” that could be imagined as causes for homosexuality—such as erotic encounters with dogs—does not in itself, of course, explain why this specific breed of dog would be employed to designate a queer but hetero-reproductive form of futurity in these erotic novels. Although this breed-specific figuration might seem disorienting to us, nineteenth-century British writing about the poodle turns out to affirm many of the (sexually suspicious) stereotypes that Des Grieux seems at pains to promote. In Aubrey Beardsley's unfinished erotic fantasia The Story of Venus and Tannhäuser (1896/1907), for instance, the representation of a “panting poodle” forms part of a perverse and decadent tableau when the Chevalier Tannhäuser observes a pornographic print depicting “how an old marquis practiced the five-finger exercise, while in front of him his mistress offered her warm fesses to a panting poodle.”Footnote 59 Although it remains unclear in Beardsley's tale which aspects of this image produce the chevalier's arousal, his response to the poodle's excitement is unequivocal, for it “made the Chevalier stroke himself a little.”Footnote 60 Originally a German breed, the pudel was widely understood by the Victorians to be of French derivation. In The Illustrated Book of the Dog (1881), for example, T. H. Joyce writes that the poodle is “a favourite of the French” and is “constantly met with on the boulevards of Paris.”Footnote 61 As with French culture itself among conservative-minded Victorians, poodles had a bad reputation, for according to Joyce, “in England the poodle proper is the least understood, and consequently the least appreciated, of almost any known breed of dog. Indeed, as a rule he is looked down upon with a feeling approaching contempt as a canine mountebank, amusing enough in his way […] but of no practical use in real life.”Footnote 62 Due to their intelligence, poodles were often trained for the disreputable spectacle of the circus, where they could be seen in human drag “walking about on hind-legs with a parasol and petticoats.”Footnote 63 (Recall the apparition of a bipedal poodle “leering” at Des Grieux in Teleny.) And notwithstanding the “sagacity” that enabled their training for such performances, poodles were also condemned for (human-imposed) artificial grooming styles. In point of fact, this “fancy dog,”Footnote 64 which was reviled among canine commentators as “a fop, whose time is largely occupied in personal embellishment,”Footnote 65 shares many of the associations that came to define the stereotypical image of the male homosexual that solidified at the fin-de-siècle and that we also see captured in Teleny's queer and decadent character Briancourt: they are viewed as vain, dandified, useless, and theatrical creatures who are not to be trusted. In view of such troping, the symbolism of poodles—those “canine clowns” that serve as receptacles for the “spirits of sodomites”—starts to make somewhat more sense for a reader in 1899 (Des Grieux 29). If selective breeding produces the inherited traits that define this disreputable dog breed, Teleny and Des Grieux keenly suggest that male homosexuality in humans may well be the result of analogous forces. It is as if the novels record the soul's multigenerational transmigration from a poodle to Camille, and so back to its own source in the body of a sodomite.

The heritability of (often unwelcome) deviant desire is central to the story Camille recounts in Teleny, as he explains his inability to repress his growing attraction to the Hungarian pianist by citing the inescapable “inclinations of [his] nature,” which dictate that he be “predisposed to love men and not women” (Teleny 1:57). Confused by his attraction to Teleny early in the novel, Des Grieux looks for answers in the world of books. In addition to ancient accounts of love between men,Footnote 66 Des Grieux also reads contemporary (and homophobic) sexological material, such as Ambrose Tardieu's work, when he researches “the love of one man for another” (Teleny 1:99). He reads “all [he] could find” about the subject, and his discoveries include information about dogs. He reads, for instance, an account “in a modern medical book, [of] how the penis of a sodomite becomes thin and pointed like a dog's,” a notion that understandably fills him “with horror and disgust,” given his strong aversion to the canine world (Teleny 1:100–101). The distorted sex organ he reads about horrifies Camille, partly because it bears no resemblance to his own healthy and “good-sized” penis (Teleny 1:43). Teleny invokes this pseudoscientific image of bodily deviance in order to explicitly repudiate it; indeed, according to Joseph Bristow, that novel explicitly situates itself in critical dialogue with the homophobic assumptions of Victorian sexology.Footnote 67 But what Teleny critiques Des Grieux appears fully to endorse, as dog-penises abound in Des Grieux's family background. The (frequently disorienting) conjunction of dogs, penises, and deviance is the ancestral legacy that Des Grieux unfolds. Des Grieux has little in the way of a sexual past when he meets Teleny, but he does have a genetic (and literary) past. And although Des Grieux's sex organs are masculine, vigorous, and decidedly human, unusual penises (human and canine) are nonetheless present among his forbears. One ancestor, Gaston Des Grieux, is described as possessing a “smooth and tapering” penis, “better fitted for the hole of the anus than for a capacious coynte” (Des Grieux 93). Judging from this and similar descriptions of penile physiognomy in Des Grieux, the ancestral male bodies in his family affirm rather than repudiate Tardieu's homophobic theories, for they are physically predisposed toward anal (or canine?) sexual expression even in the absence of male sexual partners.

The crucial difference among these canine and penile representations is that whereas Teleny, despite the “physiological” concerns announced by its subtitle (“A Physiological Romance of To-day”), stoutly refutes the imagery of the deformed and dehumanized homosexual body drawn from nineteenth-century sexology, Des Grieux embraces it with salacious, and indeed homophobic, enthusiasm. This essential disjunction between the two books strongly suggests, in the first instance, that they were composed by different hands with very different understandings of, and investments in, the impact of sexual science on queer people. Homosexuality may not be immediately visible on Des Grieux's healthy male body, but Des Grieux makes sure to argue that it is written into his body's genetic history in a code decipherable only with reference to lusty dogs. His horror of dogs is thus a genetic memory and a figure for fear of the queer self. For Des Grieux, heredity becomes fate. Read in narrative sequence after Des Grieux, then, Teleny—as Des Grieux's “Volume II”—becomes a (more positive) chronicle of sexual inevitability, and the fulfillment of a queerly generated narrative promise.

Cosmopolitan Continuities

By way of conclusion, I return to a bibliographical beginning, as it were, to take up Teleny's surprisingly informative title page. The title page states that the novel's place of publication is “Cosmopoli.” Clandestine erotic publications often resorted to false and misleading imprints, and Smithers, Teleny's publisher, had long employed such stratagems. He began issuing erotica, for instance, under the “Erotika Biblion Society” imprint during his partnership with H. S. Nichols in the 1880s.Footnote 68 But what does “Cosmopoli” itself mean? And can this obviously coded term shed any light on the persistent bibliographical enigmas posed by Teleny and, for that matter, Des Grieux?

Figure 3. The title page of Teleny

This playful fiction displaces actual geography into a realm of fantasy. It circumvents the enforcement of the punitive obscenity laws that could be brought to bear on the novel with humorous mystification. Although “Cosmopoli” has been identified by Peter Mendes as the cosmopolitan city of London, where Smithers operated, that placement is complicated somewhat by the setting of the novel, with its French characters and names, in the city of Paris. Indeed, “Cosmopoli” could represent either the epicenter of the British Empire or the city Walter Benjamin dubbed “Paris, the capital of the nineteenth century.”Footnote 69 Teleny seems to slip imaginatively between the two cities: in 1934 Charles Hirsch claimed that Teleny was originally set in London and transposed to Paris by Smithers; in his translation, Hirsch resituates the novel in London.Footnote 70 One of the effects of the appearance of “Cosmopoli” on the title page is certainly to multiply, and thus obfuscate, the text's real place of origin with a joke that demonstrates a playful awareness, on the part of those responsible for Teleny's production, of the need for concealment and double meanings. But if we regard this coding in light of the temporal—as opposed to spatial—concerns I have outlined, we can read in the title page of Teleny nothing less than a pronouncement about its place in (queer) literary history.

Teleny was not the first Smithers publication to make use of “Cosmopoli” as a false imprint. As James G. Nelson and Peter Mendes have shown, Richard Burton's translation of the first-century CE Latin erotic poems known as the Priapeia (1890) was also issued by Smithers from “Cosmopoli.”Footnote 71 Aligning the faux-Greek of “Cosmopoli” with classical erotica is just the sort of learned joke that Smithers, who prided himself on his erudition, would make. So why repeat the joke with the apparently unrelated Teleny? As we have seen, that novel cites classical, and especially Roman, precedents for homosexuality; they form a crucial part of Des Grieux's research into the history of same-sex desire in print.Footnote 72 And if Des Grieux turns to historical precedents, could not the same be said of Teleny's publisher? “Cosmopoli,” in other words, turns out to have a durable literary legacy as well. According to Ian Frederick Moulton, “Cosmopoli” was “a false name used in many editions of erotic texts in the sixteenth century, including John Wolfe's London editions of [Pietro] Aretino published in the 1580s,” and it was also employed in an 1863 Brussels edition of the sixteenth-century Italian erotic dialogue La Cazzaria (The Book of the Prick).Footnote 73 By suggesting Teleny's affiliation with both classical Latin and Renaissance erotic texts (and, crucially, ones that accord pride of place to the penis), “Cosmopoli” signals the long heritage of sexually explicit print culture. Smithers's citation of this fictional city in the paratextual framing of Teleny ultimately isn't about place; rather, it's about genealogical time. Placed in company with a past represented by the Priapeia, Aretino, and La Cazzaria, the up-to-the-moment contemporaneity announced on the title page of Teleny—“A Physiological Romance of To-Day”—also looks backward, making a long, sweeping gesture that is very queer indeed.