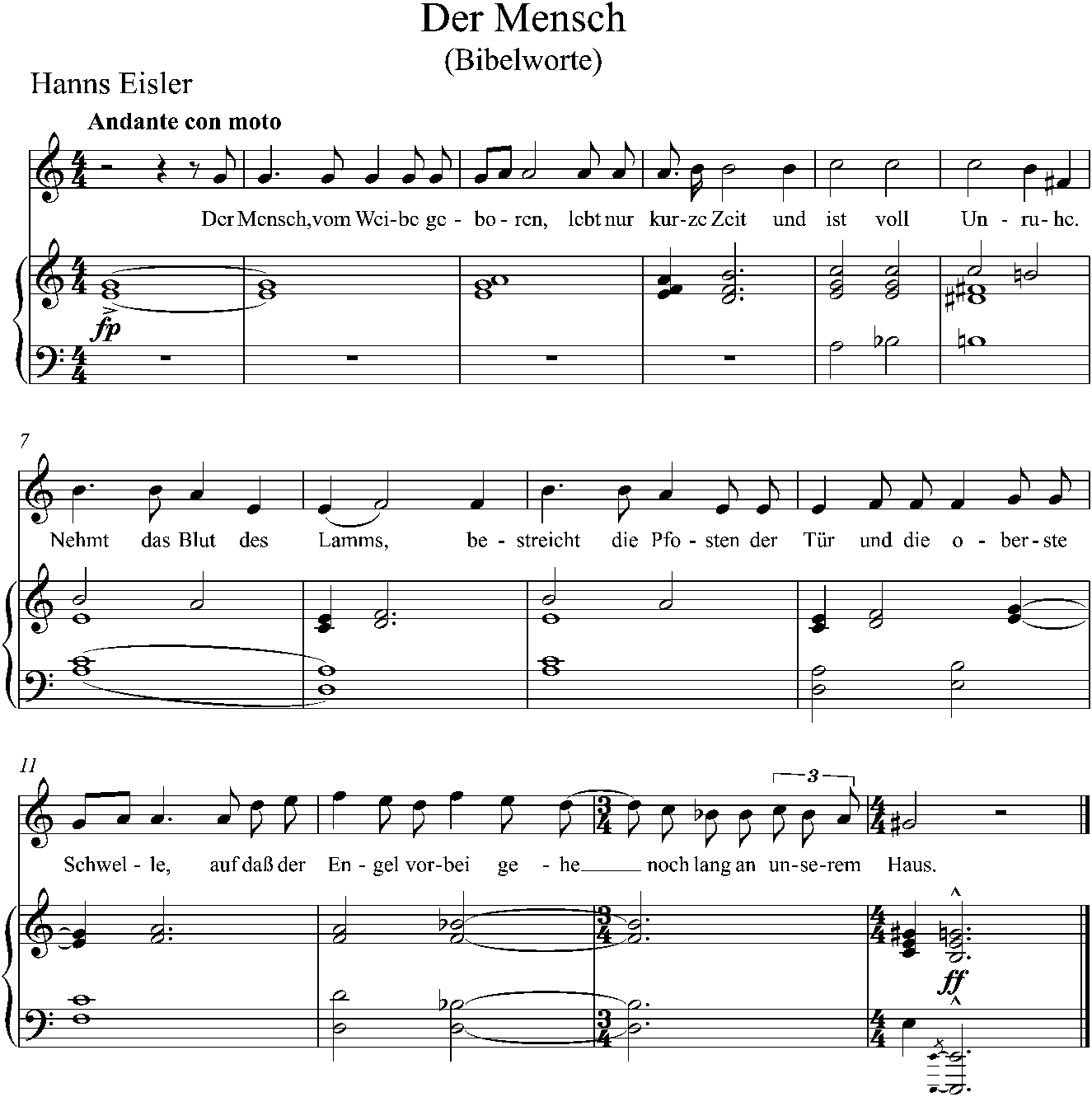

The song that opens this chapter on ontologies and definitions of Jewish music is as unlikely as it is uncommon (Example 1.1). Hanns Eisler's “Der Mensch” is unlikely because Eisler (1868–1962) rarely appears in the catalogues of twentieth-century composers contributing to a modern repertory of Jewish music. It is uncommon because the song actually does bear profound witness to a Jewish life shaped by modern history.1 It is unlikely because the song appears in a collection of songs composed by Eisler while in American exile, during the years 1942–3, when he hoped to make a career in Los Angeles composing for Hollywood films. “Der Mensch” is uncommon because it conforms to none of the genres and styles that might reflect the conventions of popular song, which, indeed, he knew well and incorporated into his music for stage and film with great skill.

Example 1.1 Hanns Eisler, “Der Mensch” (1943), from the Hollywooder Liederbuch, © by Deutscher Verlag für Musik.

“Der Mensch” announces itself as Jewish, and this, too, was uncommon for Hanns Eisler, whose attitude toward his own Jewishness, religious or cultural, was largely ambivalent. There is little ambivalence, however, in “Der Mensch.” Eisler attributes the text to “words from the Bible,” unique among the songs of the Hollywood Songbook, which draw heavily on the poetry of his most frequent collaborator, Bertolt Brecht, but freely set poetry by Goethe, Eichendorff, Hölderlin, Pascal, and others, situating the Hollywood Songbook in a historical and stylistic moment between the Romantic song cycle and the Great American Songbook.2

An unlikely moment for the enunciation of Jewishness, but it is for this reason that this moment of Jewish music is even more arresting. There is no equivocation in Eisler's deliberate evocation of sacred song. The song text, written by Eisler himself in 1943,3 combines passages from the Hebrew Bible, recognizing liturgical and exegetical practice common to many Jewish communities:4

Line 1 – Job 14:1 – The human is born of woman and lives for only a brief time, full of troubles.

Line 2 – Exodus 12:7 – Take the blood of the lamb and spread it on the sides and the upper threshold of the doorframes.

Line 3 – Exodus 12:12 and 12:23 – In order that the angel passes over our house for many years to come.

Melodically, Eisler enhances his biblical setting by using stepwise motion with declamatory rhythm, transforming what might initially seem tonal, dominant-tonic movement between G and C, through chromatic tension in the individual movement of the sparsely layered voices of the piano accompaniment. This song of suffering and exile, of the beginning and ending of human existence, belies the simplicity of resolution, textually and musically. The G# with which the voice seeks to find comfort on its final note, on “home,” turns dissonant with the piano's fortissimo move to G natural. How do we come to believe the song has reached its end?

The question that “Der Mensch” raises is both ontological and definitional: Does it define, or is it defined by, Jewish music? Does Eisler's intent to articulate an ontological moment biblically and musically suffice to enunciate Jewishness, because of or despite the song's unlikely uncommonness? Such are the questions I pose in the course of this chapter. They are questions that ultimately transform the unlikely and the uncommon into conditions that we experience as familiar when, in fact, we enter the ontological moments of Jewish music. Hanns Eisler's “Der Mensch,” too, becomes familiar as Jewish music when we place it in the five conditions that define moments of ontology in the section that follows: religion, language, body, geography, identity – they are all there. They converge musically to expand the field of definitions through which we have come to sound and experience Jewish music.

The problem and paradox of definition

The ontology of Jewish music is tied to the critical need to define and delimit. At many moments in Jewish intellectual history that critical need becomes virtually obsessive. The musicality of sacred texts and worship has been crucial to biblical exegesis and traditions of commentary, in other words, to the tradition and transmission of Torah and Talmud. Extending the boundaries of sacred song to secular song proved fundamental to creating national music during the early decades of modern Israeli statehood. Anti-Semites and philo-Semites alike sought ways to make Jewish music identifiable and to calculate its impact on cultural identity.5 Ontological questions were as pressing for those who asserted that virtually no music was truly Jewish as for those who believed virtually every music had the potential to be Jewish. The questions seem never to abate, with debates that seek resolution or even consensus still raging across the Internet of the twenty-first century.

The ontological search to identify and define Jewish music, moreover, took the form of action and agency, transforming the abstract to the material. At various moments in Jewish liturgical history, when sacred-music specialists sought repertories that would lead them toward professionalism, they discovered and invented, collected and created anew practices of Jewish music that would allow them to become cantors and composers. Religious and musical specialists in communities at the greatest extremes from the Ashkenazic and Sephardic diasporas, for example, the Falashim in eastern Africa and the Bene Yisrael in South Asia, consolidated musical practices that distinguished them as Jewish. The ideological challenge of generating “Jewish folk music” or “Jewish popular music” in eras of shifting political boundaries sent collectors to the field and performers to street and stage alike.6 Moments of anxiety about the absence of Jewish music – the loss of Judeo-Spanish romancero after the reconquista or klezmer after the Shoah – inspired the agency that led to their revival.

The concerted efforts to make Jewish music material, hence, to afford it with the meaning necessary for religious, social, and political action, accrue to what I call “ontological moments” in this chapter. At these ontological moments Jewish music becomes identifiable because of what it can do by contributing to the definition of self, other, or both at moments of historical change and, often, political exigency. At such moments, Jewish music is not simply passed along as definable identities with authenticity and authority from the past, rather it responds to the need to define identities that respond to the present. The old and the new converge at the ontological moments in which Jewish music acquires its identities, shaping the ways in which Jewish history itself unfolds. The historical conditions and musical subjectivities that yield the ontological moments I consider here combine ontologies and definitions of Jewish music in different and distinctive ways. I should like to outline these conditions and subjectivities briefly before turning to the series of ontological moments I further explore in this chapter. The five conditions and subjectivities are neither definitive nor exhaustive, but they are meant to be comprehensive, thereby opening the historiographical field of this chapter and the volume in which it appears below.

1) Sacred ontologies / religious definitions: Revelation of sacred voice 2) Textual ontologies / linguistic definitions: Jewishness conveyed by Jewish language (Hebrew, Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Arabic, etc.) 3) Embodied ontologies / contextual definitions: Genealogical descent and identity 4) Spatial ontologies / geographical definitions: Jewish music in the synagogue or ritual practices 5) Cultural ontologies / political definitions: Music and survival in a world of otherness Ontological moments of Jewish music – conditions and subjectivities

At the core of the paradox of defining Jewish music is the frequent belief in authenticity, chosenness, and uniqueness. No definition of Jewish music has more currency in the past half-century than that of Curt Sachs (1881–1959), an immigrant German-Jewish comparative musicologist and organologist, who is reputed to have established at the 1957 International Conference on Jewish Music in Jerusalem that Jewish music is “by Jews, for Jews, as Jews.” Sachs's own distinguished career – the classification system for musical instruments that he developed with his Jewish Berlin colleague Erich M. von Hornbostel (1877–1935) remains the standard worldwide almost a century after it was formulated – would hardly confirm that he placed much currency in such an essentialist definition.

The frequency with which we encounter the definition, nonetheless, suggests it reveals a belief in the selfness of music that many wish to will into existence. It represents a class of definitions that accepts that, whatever else Jewishness is, it is self-contained, biologically determined, and borne with other attributes of chosenness. Historically, we witness the ways in which such definitions express a concern for pollution and chosenness, as well as anxieties for the boundaries and borders with the non-Jewish. The continuum of definitions from exclusive to inclusive represents the persistent tendency to define Jewish music by what it is not and should not be: secular, hybrid, mixed gender, too beautiful, too noisy or dissonant. There is a sharp critical awareness that is turned toward music that does not fulfill the definitions of Jewish music, even when – or even especially when – those definitions are not stated.

A more expansive history of music in Jewish thought and experience, however, reveals that exclusive definitions form along a continuum that also accepts inclusiveness and the accompanying contradictions. Music “by Jews” may not be compatible with performance “as Jews.” Subjectivities of exclusivity may create boundaries within self even more than with other. Such is the case, for example, with injunctions against hearing kol isha (woman's voice) in orthodox Jewish sacred music, which has historically justified gender separation in the synagogue no less than the refusal to allow women to worship and sing at many of the most sacred of all Jewish sites in Israel, notably the Western Wall. In contrast, the revival of the repertory and practice of popular music regarded as most Jewish of all in post-Shoah Europe, klezmer, has attracted far more non-Jewish performers and audiences than Jewish. Complicating the definitional paradox even more are the traditions in which Jewish musical professionals dominated the performance of music that was not “theirs,” for example, the art music of Muslim courts in the Middle East and Central Asia. Under other historical circumstances, say, in the history of the modern musical and film music, the creation of music that was not exclusively “theirs” was crucial to a process of musical translation and social transformation.

In the section that follows I explore the historically changing meanings of Jewish music by examining multiple ontological moments. Jewish intellectual history accrues to these moments as a set of responses to changing historical landscapes and conditions, particularly the relations of individual Jewish communities and their social practices to the world about them. Historically, music provided one of the most powerful means and voices for response, and it is for these reasons that the ontologies and definitions of Jewish music are so critically important to understanding the larger forces that shaped Jewish history.7

Ontological moments of Jewish music

Be-reshit – ontological moments of musical translation

The ontological moments of Jewish music begin as acts of translation. Jewish music comes into being when an original text or ritual process undergoes transformation that expands upon its meanings, enhancing them within the multiplying contexts of Jewish culture and history. The enhancement of biblical text or prayer through cantillation and chant is possible because of the musical attributes of targum, a translation that functions also as interpretation. The ontological moment from which sacred Jewish music emerges, thus, retains the essential elements of its original forms, but it allows them to serve in new ways, responding to changing texts and contexts. The forms of translation that create Jewish music are themselves strikingly evident in the intellectual history of Jewish thought. Biblical translation begins at the beginning, with the Torah, and continues unabated as the tradition of interpretation that historically unifies and transforms the metaphysics of Judaism to the present. Torah recitation relies on the translatability that sustains the changing sameness of interpretation over the historical longue durée, as well as under the immediate constraints of the present. Biblical translation also expands the field of difference. Accordingly, every act of translation is political, whether by establishing contemporary linguistic meaning from related languages or establishing the limits of interpretation for the different religions, especially those constituting the Abrahamic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam that draw upon biblical texts and narratives.8

An intellectual history of Jewish music, therefore, accrues to the ontological moments as acts of translation and interpretation come into being. Such moments are fully evident be-reshit, in Genesis, the first book of Moses in the Torah. Accounts of the origins of music appear in both the fourth and twenty-second chapters of Genesis. In the first account, we encounter different narratives about the human attributes of music (Yuval as the inventor of music generated by the body) and those that describe attributes forged through artifice (Tubal Cain as the inventor of instruments from bronze and iron). In the second account, the Akeda, or “Binding of Isaac,” it is the shofar, the ram's horn left after the burnt sacrifice that replaces the sacrifice Abraham was prepared to make of his own son, that enters Jewish ritual history as the horn blown during the High Holidays.

From the beginnings in Genesis, musical instruments enter the Bible in ever-increasing numbers from sources within and outside the Jewish communities that constitute the historical landscape and polity of the Bible. The Psalms identify instruments played as components of ritual and community praise. Psalm 150, for example, accounts for a full orchestra, used to accompany dance no less than prayer and praise in the sanctuary of God. The Psalms also contain frequent references to genre, for example shir ha-ma'alot (song of degrees), at the beginning of Psalms 120–34, sung during pilgrimage festivals.

As texts that identify musical attributes, the biblical references to music were – and are – open to interpretation, and it is for this reason that we are able to understand the meanings of music that they convey as acts of translation.9 Such acts of translation function in different ways and rely on different forms of transformation in the intellectual history of Jewish music, and it is crucial to recognize these differences as we seek meaning and definition for Jewish music. Musical translation, for example, frequently takes the form of mediation. Sacred voice or sacred acts are performed by intermediates, such as Yuval or the angel of God in the passages on the origins of musical instruments in Genesis. Musical translation is necessary because of the several languages spoken and used in Jewish communities throughout history, making polyglossia and intertextuality normative. The exile of Jews in Babylon provided only the first of many historical narratives yielding allegories about musical distinction and interpretation. Musical translation characterizes communities that form around borders of all kinds, where it accommodates movement and migration. As ontology translation ensured the historical processes that could renew music as Jewish.

1. By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. 2. Upon the willows in the midst thereof we hanged up our harps. 3. For there they that led us captive asked of us words of song, and our tormentors asked of us mirth: “Sing us one of the songs of Zion.” 4. How shall we sing the LORD's song in a foreign land? Shir ḥadash – ontological moments of diaspora

Even the biblical narratives of diaspora challenge the ontological status of Jewish music. In Psalm 137, the very possibility of singing a “song of Zion” in a place of otherness is called into question, establishing conditions of otherness that appear repeatedly across the successive diasporas that would define Jewish history. Many forms of encounter have shaped the history of Jewish diaspora – religious, racial, cultural, political, military – each of them accompanied significantly by musical encounter. The crucial questions are already evident in Psalm 137. How does the music of Jewish selfness – the abandoned harp, the song of Zion – enable survival? Is lament the only means of musically representing the past? If music making only brings mirth and celebration to the tormenting others, does it shift the boundaries between self and other? Psalm 137 does contain responses to the questions of its opening lines, troubling as they are, in a call for remembering the loss of Jerusalem also with a music of vengeance and survival. In the sixth line the Psalmist continues: “Let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth, if I remember thee not, if I set not Jerusalem above my chiefest joy.”

The resolution of self and other remains in question in the countless moments of musical encounter that form the historical longue durée of Jewish diaspora. Ontological boundaries form in the ways music defines encounter, even in the earliest communities forming after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE, historically imagined as the site at which Jewish musical practices were canonized. In exile from Jerusalem, Jews would need to worship locally in the synagogue, yet bear with them the traditions that they could experience through memory alone. Musical practices changed to accommodate the local, with oral and written traditions forming a counterpoint that contributed to the resolution of self and other.

It is hardly surprising that Jewish music enters modern historiography as evidence for the local worship practices resolving the encounter of self and other. Abraham Zvi Idelsohn (1882–1938), for example, regarded the spread of musical practice in diaspora synagogues as critical to Jewish music itself.10 In his comparative studies, the musical markers of Jewishness were resilient, not because they could be reduced to authenticity, but because they accommodated the possibilities of generating “new song” (shir ḥadash), hence the survival of Jewish communities in diaspora.

The ontological moments of diaspora also yield hybridity, religious and cultural subjectivities in which selfness and otherness are interdependent. When rituals and repertories change, they respond to the exchange of music across religious and cultural boundaries. The systems of mode that provide the structural framework for diaspora traditions most often absorb local traditions, even when these signify musical practices that have little to do with Jewish worship. The oldest Jewish communities in India, for example, the Bene Yisrael and the Cochin Jews – the former settled for at least two millennia, the latter for about 1300 years – use rāga, the theoretical basis of Indian classical music. The standardized modal system used in the synagogues of Israel today, the “Jerusalem-Sephardi” tradition, is based on maqām, or mode, in the Arabic classical music of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Folk- and popular-music traditions, in the Jewish diaspora or from the Jewish diaspora, depend extensively on hybridity. The Israeli popular music known as musica mizrakhit (eastern music) often makes use not only of maqām, but also of genres from Arabic popular music, such as layālī.11 Jewish folk music in the Ashkenazic traditions of central and eastern Europe often forms repertories around the boundary regions in which intercultural exchange is most intensive and normative.12 Individual songs in such regions often circulate in Yiddish and German, as well as their many dialects. Similarly, they may combine additional linguistic variants, published in translations to and from Hebrew, or in regional languages. In diasporic music traditions hybridity is fluid and responsive to the changing historical conditions that prescribe the ontological moments of Jewish music.

Vox populi – musical ontologies of collection and community

At each stage in a Jewish intellectual history constituted of ontological moments, there was a renewal and revival of Jewish music as new and modern. The modernity of a repertory was assured by the ways it gathered parts from the past and provided a new context for them in the present. The modernity of early modern Jewish musical practice in the wake of the expulsion of Jews from Spain and Portugal at the end of the fifteenth century was measured in the pace of change from prima to seconda prattica (first and second practice) in the late Renaissance repertories of sacred music by Jewish composers in northern Italy, notably Salamone Rossi (c. 1570–c. 1628), whom Don Harrán identifies as one of the first historical figures designated as a “Jewish musician.”13 New repertories, no less than repertories of new Jewish music, led to the formation of new categories of musician with responsibility for upholding the presence of the traditional in the modern. The early modern developments in music printing, for example, led to the publication of new works and genres of Jewish music for sacred and secular practice, among them Rossi's Ha-shirim asher lishlomo (Songs of Solomon, c. 1622), in which his role as composer is evident in the play between the names of the biblical and modern musicians, Solomon, thus a clear modernization of the usual title, Shir ha-shirim (Song of Songs).

Other Jewish repertories formed as a response to modern technologies of musical reproduction. The first printings of European ballads from the fifteenth century consolidated repertories of songs with Hebrew orthography that served to locate narrative genres from medieval Ladino and Yiddish oral traditions in broadsides and folios that circulated in the growing public sphere of early modern Europe.14 These would attract the attention of the early collector of folk song in the Enlightenment, Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), who first invented the term Volkslied (folk song) for his collections of the 1770s, among which Jewish ballads are to be found, for example, “Die Jüdin” (The Jewish Woman), already part of a canon of ballads from the late Middle Ages.

As folk-song collecting became one of the most important media for the expression of nationalism in the nineteenth century, the search for Jewish folk song, too, accelerated. A vocabulary that circumscribed Jewish folk music may have developed later in the nineteenth century, probably in the early 1880s, but within decades thereafter, volume upon volume appeared, containing modern editions of Jewish folk music that needed to be protected against loss.15 The songs now called Jewish in these modern collections resulted from considerable acts of collection, translation, and dissemination. German-language collections contained parallel song texts, in modern Yiddish and High German, enhancing their literary value. Collections of urban popular music included texts that spoke to the social conditions of the day. Instrumental collections documented the paths of ensembles from East to West, representing the earliest histories of klezmer musicians.

Collecting Jewish music contributed substantially to the rise of a modern class of Jewish professionals primarily engaged with music. That rise is spectacularly evident in the transformation of the ḥazzan and the ḥazzanut to the cantor and the cantorate in the nineteenth century. Cantors came to fulfill many different roles in the European urban synagogue – teacher, composer, choral director, sometimes even star performer in the community – many of which served as an index to growing professionalism. The repertories used by cantors increasingly appeared in print, frequently with new compositions, which reveal the shifting of borders that connected them to an ontological moment. In Salomon Sulzer's Schir Zion (Song of Zion) of 1840/41, for example, there are compositions by other composers of the day, among them Franz Schubert, who contributed a setting of Psalm 92.16 Cantorial societies were forming by the mid-nineteenth century, and these published journals that connected cantors worldwide. By the early twentieth century, the modernization of the cantorate had produced inroads into early recordings. Jewish music was becoming very modern indeed, and its modernity was sounded across an expanding public sphere, both Jewish and non-Jewish.

The in-gathering of Jewish music – recorded ontologies

The prayer following the Passover meal had been recited, the end of the hagadah had been reached, and the seder had come to its conclusion. Everyone passed into the living room, where a phonograph with Joseph's narrative on a cylinder stood on the table…David sat down beside the machine and turned the horn toward the listeners.

Recorded sound and song were critical to the histories that paved the return to the Yishuv, the modern settlement of the land of Israel. Phonographs and the sounds they reproduced appear in Zionist narratives in all genres, from the utopian fiction in Theodor Herzl's novel Altneuland (1904), from which the above epigraph is taken, to the scientific reports that amateur and professional scholars, such as Idelsohn, brought back to the scientific commissions that sponsored their field research.18 The early twentieth-century recording excursions in the Yishuv took as their model the first uses of wax-cylinder and wax-disc technology used to gather the sounds of cultural difference and distinction – folk song and folk music, language and dialect – from places far away in order that they could be heard again and organized into the repertories and social hierarchies that gave order to history and culture. The early ontological moments that captured sound and music formed what Mark Katz calls “record events.”19 The proliferation and spread of such record events paralleled the transformations in Jewish history that began in the final decade of the nineteenth century and led to the foundation of Israel in the mid-twentieth century. The record event consolidates and shapes ontological moments. Listening to a recording of a Yemenite Jewish song, for example, is a shared experience. Recordings reach into disparate pasts, but they sound common presents. Spatially defined by their tangibility, they replay the common dimensions of the Jewish music they physically establish.

It would be possible, in fact, to write modern Jewish and Israeli history as a succession of record events that influenced, no less than they were influenced by, social, cultural, political, linguistic, and musical of modernity. Recordings gave Jewish music a new reality, the tangibility and portability Katz claims as the result of record events. With recording machines, themselves portable, it was possible to traverse the diaspora in search of Jewish music, to find it wherever Jewish communities were found, and to gather it, consolidating both commonness and difference as repertory, genre, ritual, and history – as sound and the materials that captured it. Recordings transformed sound to history, and Jewish music on record made history. Recordings located Jewish music in time, and the collectors and scholars of Jewish music reimagined and rewrote Jewish history by connecting past to present to future. Idelsohn's wax-disc recordings in Jerusalem from 1911–13 were foundational to his most influential writings, especially Jewish Music in Its Historical Development. Robert Lachmann's wax-cylinder recordings in Jewish communities on the island of Djerba off the coast of Tunisia freed them from temporal isolation and retrieved them, sonically, for Jewish history.20

The proliferation of recordings of Jewish music, as well as the materiality of their reproducibility through 78-rpm shellacs, LPs, cassettes, and digital technology, reflects an ontology of in-gathering. It is that in-gathering – from the centers of diaspora communities no less than from the farthest peripheries – that motivated the establishment of archives and Jewish music research in its twentieth- and twenty-first-century forms. The historical path from Idelsohn's wax-disc recordings to their publication in the early volumes of the Hebräisch-orientalischer Melodienschatz (The Thesaurus of Hebrew Oriental Melodies),21 to their accessibility to the first generation of Israeli composers and to their digitization22 lends Jewish music specifically technological dimensions, which in turn are ever expanding. The intellectual history of Jewish music research that began with Lachmann's archival impulse in Berlin and led to the establishment of the Archives of Oriental Music in Jerusalem, which in turn provided the foundations for the Jewish Music Research Centre at the Hebrew University, has been critical for the subject formations that afford Jewish music a common set of ontologies for all subdisciplines of modern Jewish music scholarship. It is this field of Jewish music that the contributors to the present volume share.

Film and music – mediating Jewish ontologies

Jewish music was part of sound film from the beginning. The very subject of the first full-length talkie, Alan Crosland's The Jazz Singer (1927), based on Samuel Raphaelson's novel The Day of Atonement, formed around the decision faced by an immigrant Jewish son, Jakie Rabinowitz/Jack Robin, to remain true to the traditional world of his orthodox family or enter the world of popular American music. Throughout the film the “jazz singer” crossed musical borders, between the ritual practices of home and synagogue, between the stages claimed by great cantors, notably Yossele Rosenblatt (1882–1933), and the clubs and theatrical venues claimed by Al Jolson (1886–1950) playing a leading role both fictional and real. The Jazz Singer posed ontological questions and provided answers to them, but ultimately multiplied the ways in which the viewer could understand and define Jewish music.

The first German sound film, Josef von Sternberg's 1930 Der blaue Engel (The Blue Angel), similarly placed jazz and Jewish music on the stage representing its center – “The Blue Angel” was the name of a cabaret in the harbor district of a larger German city, where much of the movie is musically enacted – but poses yet other ontological questions about what these musics might signify in modern society. Musical borders and boundaries crisscross throughout the film, undoing the distinctions between the worlds realized musically on and off the cabaret stage. The house band at the Blue Angel, Weintraub's Syncopators, performs diegetically throughout the film, with songs by Friedrich Holländer, leader of the Syncopators, drawn from his signature jazz style for Marlene Dietrich, who played the lead in the film. The Jewishness of the music in The Blue Angel is at once obvious and thrown into question. As sound film and film music developed – and both Holländer and Dietrich would follow careers that intersected with the history of film music through the 1930s and then the Shoah – ontological questions would multiply, always at the intersection of modern film and Jewish history.

The mediation of Jewishness in film music shaped vastly different historical processes and cinematically portrayed complex social formations. Among the first experiments with sound film were modernist compositions in the mid-1920s, and among these one of the most influential was Hanns Eisler's Opus III, composed as an accompaniment to Walter Ruttmann's 1925 Berlin, die Sinfonie der Großstadt & Melodie der Welt (Berlin, Symphony of the City and Melody of the World). In Opus III Eisler concerned himself with the representational borders between shifting, abstract shapes and musical sound. Throughout his long and influential career as a film composer Eisler moved in different ways between film and music, from his earliest collaborations with Bertolt Brecht (Kuhle Wampe, 1932), through those with Fritz Lang (Hangmen Also Die, 1943) and Charlie Chaplin (The Circus, 1947), to the soundtrack for the first large-scale documentary about Auschwitz, Alain Resnais's 1955 Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog). The music in these films also expressed Jewishness in vastly different ways, sometimes not at all, at other times dispassionately, directly, as in the Auschwitz film. In his extensive theoretical writings on music and film, especially in the first major book on film music, co-authored with Theodor W. Adorno, Composing for the Films (1947), Eisler provides more questions than answers.23 The condition he describes as “dramaturgical counterpoint” leaves the borders between music and narrative representation in film intact. The question of Jewish film music remains unresolved.

In the short-lived age of Yiddish film, however, the possibility of resolving the question is unequivocal. In the 1930s, the decade immediately following the emergence of sound film, Yiddish film flourished. In less than a decade, film studios in Poland mustered actors and musicians, screenwriters and composers, from across the diaspora to produce a series of classic films, among them Joseph Green's 1936 Yidl mitn fidl (Yidl with His Fiddle) and 1937 Der purimshpilr (The Purim Actor; also called The Jester). As in The Jazz Singer and The Blue Angel, Jewish music itself – klezmer and the theatrical traditions of the Purim season – provide means of exploring the musical attributes of cinema. The borders between the stage and reality, traditional music and modern popular music, too, are plied. The worlds sounded with music are Jewish, but they are fragile, and as history would prove, endangered. The music that filled these cinematic worlds, too, was endangered, but for that reason as well, was powerfully and poignantly Jewish.

Jewish music as Israeli music – national and nationalist ontologies

The exile, displacement, and return that rerouted modern Jewish history in the early twentieth century were no less dramatic in resituating the ontological questions about the meaning of Jewish music. Rather than being posed primarily in the lands of the diaspora and the Holocaust, the new questions began to equate Jewish music and Israeli, and they searched for answers in the culture and ideology of the State of Israel, even before its founding in 1948. The early collectors began the process of rerouting Jewish music history to the Yishuv, for example, when Idelsohn made his wax-cylinder recordings in the communities formed of immigrants from the diaspora. In the wake of World War I, with the collapse of nineteenth-century European nations and empires, Jewish settlers returned to mandatory Palestine, where they actively employed music in the processes of nation-building.24 Ambitious plans were enacted to create recording collections, such as Robert Lachmann's in Berlin and after 1935 in Jerusalem,25 and to build archives that would provide nothing short of a “World Centre for Jewish Music.”26 Folk songs in modern Hebrew were gathered from the kibbutzim (communal settlements) and circulated to Jewish composers throughout the world who might collectively create a national repertory of Israeli art song even prior to statehood.27 Modern Jewish music, combining the old and the new, should become the music of Israel.

The new music of Israel provided contexts for reconfiguring the ontological moments of Jewish music as national – and as international. Israeli folk music, for example, would differ from Jewish folk music insofar as it resulted from the musical repertories and practices of immigrant and ethnic communities in Israel. Musical scholars turned their attention to the musical cultures of Yemenite-, Iraqi-, or Syrian-Israelis, many of which developed repertories and rituals in languages that were identifiably Jewish, such as the Judeo-Arabic of the Yemenite Jewish diwan tradition. The study of liturgical music in Israel spread to Moroccan baqqashot and Sephardi romances in the South American, Greek, or Turkish community. Israeli music was vast enough to embrace the multitude of differences that had historically distinguished Jewish musics.28

Israeli art-music composers, too, confronted the need to accept or reject concepts of Jewish music. Those composers who chose to create a style that would reflect the modern nation, for example Paul Ben-Haim (1897–1984), had the opportunity of drawing from a vast store of sounds, genres, and repertories to shape movements such as Eastern Mediterraneanism. Composers preferring, instead, to reject a strictly nationalist compositional style, for example Josef Tal (1910–2008), still engaged with the historical materials of Jewish music to shape their more personal or cosmopolitan vision of Israeli music.

Popular music in Israel, too, followed a historical course that moved through numerous repertories that contained traditional Jewish practices, or had formed along the borders with non-Jewish neighboring communities.29 Musica mizrakhit (eastern music) provided the basis for popular music in the rapidly growing eastern Jewish ethnic communities at the end of the twentieth century, but it contained a rich store of sounds for other popular musicians to make their musics Israeli. At its most cosmopolitan extremes, popular musics in Israel are notable because they rarely forego sounding Israeli in some way, and this often means not foregoing the identifiably Jewish. Israeli jazz festivals in Europe or the United States, for example, regularly turn to synagogues for concert venues. The mix of global and local that Israel brings to the annual Eurovision Song Contest also insists on a fusion of the Jewish and the Israeli, often to political and ideological ends. The musicians of modern Israel, whether creators of folk, popular, or art music, whether working with traditional materials or forging avant-garde experimentalism, sustain a history of defining and redefining Jewish music and the twenty-first-century ontological moments in which we experience that music.

Jewish music beyond itself

By setting biblical texts in “Der Mensch” (Example 1.1) Hanns Eisler was not trying to compose music that was in some way specifically Jewish, or that would conform to the expectations of those compelled to define music as Jewish. He aspired, instead, to create a moment in which the Jewish elements from which he drew allowed the song to become more than itself. His turn to an ontological moment of Jewish music was for Eisler a search for transcendence. By recognizing its ontology as Jewish music Eisler actually unleashed it from definitions that would limit and isolate Jewish music to no more than itself, a cipher of essentialized identity unable to escape itself. Definitions of Jewish music made evident the permeability of borders and boundaries, the sites of agency. Eisler recognized, indeed believed, that Jewish music had the potential to make history – historiographically and ontologically – in those moments when Jewish music could be more than itself.

The explorations of meaning that I undertake in this chapter illustrate the paradox and counterpoint that determine the many paths of Jewish music history. The counterhistories that we witness at the ontological moments of Jewish music are many rather than few, and they rarely afford us the materials for definitions. Jewish music today bears witness to what we might call the “anti-teleology” of Jewish history. The belief that history converges with an in-gathering after diaspora is countered by the expanded and more complex presence of Jewish music in the world – and Jewish music in world music. When we consider ontologies and definitions historically and situate them in Jewish intellectual history, however, we recognize that they have long been anti-teleological: they are responsive and resistive; they make space for self and other; they may be highly exclusive and broadly inclusive. It is these many processes that we witness in the chapters of this volume that ultimately bring us closer to a field of definitions and ontologies of Jewish music that expands at each ontological moment as Jewish music becomes more than itself.