On the evening of 14 August 1651, a number of prominent Londoners, who had just heard a sermon on The New Jerusalem, retired to the Painters-Stainers’ Hall on Little Trinity Lane for a convivial feast of venison and ale. The company, which was predominantly composed of mathematicians, medical practitioners and instrument-makers, engaged in learned conversation until the early hours of the morning, when one of their number, the antiquarian Elias Ashmole (1617–1692), regrettably fell ill with a ‘surfeit’.Footnote 1 In the months that followed, the guests kept in touch through the postal service, requesting further details from their conversations in August and planning additional collaborative projects.Footnote 2 Like Ashmole, many of those present were keen participants in the vibrant culture of practical mathematics that thrived in London in the second half of the seventeenth century. Indeed, although this was clearly a fun-loving group, these were studious people whose lively feast was underpinned by very serious aims. Their feast in August 1651 was one of a great many similar events organized over a forty-year period. The group was the Society of Astrologers of London, and this was their annual general meeting.

Before the formation of the Royal Society in 1660, London was home to several voluntary institutions in pursuit of knowledge of nature. The little-studied Society of Astrologers, who also went by the names ‘Society of Artists’ and ‘Learned Students in Astrology’, was one of these collectives.Footnote 3 From 1647 until the mid-1680s, this energetic group met in London churches and taverns to enjoy feasts, listen to sermons, exchange instruments and manuscripts and translate astrological texts. Their main objective was to ‘resuscitate’ the science of the stars, which they believed was desperately suffocating under the weight of persistent attacks.Footnote 4 Not only was astrological education increasingly difficult to come by in English universities, but aspersions cast upon astrology by English preachers meant that the art was ‘of late despised’, and in desperate need of ‘vindication … from the Scandalls of the Ignorant and Malitious’. The society saw their task in distinctly national terms. Astrology was ‘hardly knowne to this … Segment of the Terrestrial-Globe’, and the society accordingly hoped to teach it widely, making it ‘publique to the Benifitt of this Nation’.Footnote 5 In the face of accusations that astrology was ‘a wicked Art, whose original is from the Devil’, the society took it upon themselves to convince the public that it was instead a ‘Divine-science’ with a venerable biblical history.Footnote 6 Emerging on the eve of the decline of astrology throughout Europe, the Society of Astrologers was in the business of public relations. The present article, drawing on untapped archival material, offers the first full account of this little-understood society, focusing on their dual attempts to democratize and legitimize their art.

The Society of Astrologers has received little attention from historians. This is perhaps unsurprising considering that, when compared with the Royal Society, limited contemporary testimony has survived. Moreover, early historians of science tended to overlook ‘unsuccessful’ knowledge systems like astrology.Footnote 7 Coming of age in a period associated with experimental science and its institutionalization, the Society of Astrologers has frequently met with derision and dismissal by scholars.Footnote 8 These days historians of science take astrology far more seriously. Beginning in the 1970s, Keith Thomas, Peter Wright and Patrick Curry produced some initial work on the Society of Astrologers.Footnote 9 Vittoria Feola has more recently provided a short description of the society's origins and activities.Footnote 10 These accounts offer us only a partial view, however, because none considers the full range of available evidence. Taken together, manuscript sources, the publications of society members and their critics, and especially the society's commissioned sermons generate a rich picture of an ephemeral institution fighting for celestial causation. Studying the overlooked Society of Astrologers enriches our understanding of seventeenth-century intellectual culture first by shedding new light on a frequently disregarded subset of the London mathematical community, and second by fleshing out our current understanding of astrology's contested status in this period with new evidence of a reactionary socio-religious campaign. Moreover, in contrast to the received picture of London astrologers in this period, which emphasizes their bitter competition and fiery interchanges, this article draws attention instead to their attempts at unity, their endeavours to mount a united front in defence of astrology in spite of their admittedly complicated and often thorny interrelationships.Footnote 11

As a practical part of astronomy, astrology was a complex mathematical art. The first section of this article, which outlines the society's origins, members and meetings, locates their democratizing aims within broader contemporary programmes to promote mathematical education. Yet, unlike other mathematical arts, astrology's religious credibility was under serious threat. The Society of Astrologers, desperately aware of this, embarked on a campaign to restore astrology's religious credentials. As I show below, a key part of this strategy was the organization of a series of six sermons in London churches in the 1640s and 1650s. I argue that the society commissioned the delivery and publication of apologetic sermons with the aim of legitimizing astrology on the basis of its sacred history. This tactic makes sense when we consider that a large amount of English attacks against astrology in this period were more religiously than scientifically based.Footnote 12 While work on the decline of astrology in England has paid much attention to the success of satirical assaults on the art, we should not ignore the serious religious and theological issues that were at stake.Footnote 13 That the society invested so much in defending astrology's religious legitimacy suggests that they saw this as a primary barrier to wider acceptance of the art. Nevertheless, as I outline in the final section, which introduces several hitherto unknown critiques of the society, the astrologers failed to persuade, and the society soon dissolved. Not only were they mounting a rearguard action, but also they built their legitimizing campaign on obsolete historical arguments.

The Society of Astrologers: origins, members and activities

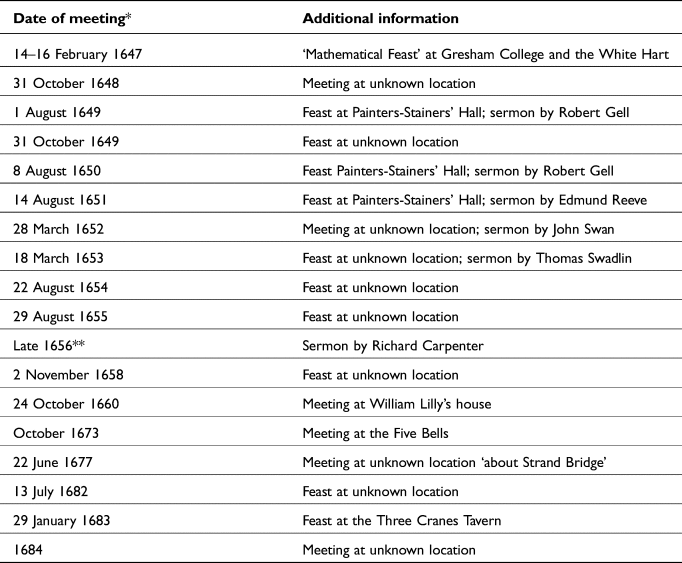

The Society of Astrologers came into being at a time when mathematical practitioners thrived in London. Those with expertise in timekeeping, navigation, surveying, hydrography and other fields grew in popularity and sophistication from the mid-seventeenth century and were increasingly organized in professional and commercial institutions.Footnote 14 This was a culture that privileged arts that were practical. Called upon to provide guidance on relationships, travel, agriculture and health, astrologers enjoyed extraordinary popularity in England especially during the Civil War (1642–51) and Interregnum (1649–60), when practitioners promised to address various personal and political needs.Footnote 15 Yet the formation of the Society of Astrologers was prompted by the knowledge that the art was being seriously challenged in learned circles.Footnote 16 It was also harder to access astrological teaching at the universities. The Savilian statutes of 1619, for example, had ‘utterly debarred’ the professor of astronomy at Oxford from teaching ‘all judicial astrology without exception’.Footnote 17 Such circumstances called for the opportunities afforded by institutionalization. Like other mathematical clubs, the Society of Astrologers originated in gatherings at Gresham College during the 1640s. Gresham lectures on astronomy and geometry provided a forum for like-minded people – mechanical craftspeople as well as gentlemen natural philosophers – to socialize over shared interests.Footnote 18 In November 1646, Jonas Moore (1617–79), leading mathematician and central figure in this community, introduced two people who would become intimate friends and leading members of the Society of Astrologers: Elias Ashmole and the astrologer William Lilly (1602–81).Footnote 19 Ashmole was shortly invited to a ‘Feast of Mathematicians’ at Gresham and the White Hart.Footnote 20 Soon the astrologers in the group organized their own ‘Feast of Astrologers’, which was held annually, alongside other informal gatherings. Six of their feasts were preceded by sermons on astrology's religious legitimacy, held on at least two occasions at the wealthy Church of Saint Mary Aldermary.Footnote 21 Some of the society's events were particularly well timed. Their meeting on 28 March 1652, for example, was held the day before the notorious ‘Black Monday’ solar eclipse, a major media event.Footnote 22 After 1656, however, there is no consistent record of regular society meetings for almost two decades. After a handful of events in the late 1670s and the 1680s, which Ashmole describes as a restoration of the feast by the mathematician and globe-maker Joseph Moxon, the society seems to have disbanded (see Table 1).Footnote 23

Table 1. Known meetings of the Society of Astrologers.

* Evidence for these meetings is derived from C.H. Josten (ed.), Elias Ashmole: His Autobiographical and Historical Notes, His Correspondence, and Other Contemporary Sources, 5 vols., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967, vol. 2, pp. 418–19, 492–3, 539, 580, 640, 665, 679, 751; vol. 4, pp. 1485–6, 1705, 1712; William Lilly, Merlini Anglici Ephemeris, London: Humphrey Blunden, 1649, sig. B1r; Mercurius Politicus, London, 15 August 1650, issue 10; John Swan, Signa Coeli, London: John Williams, 1652; Richard Carpenter, Astrology Proved Harmless, Useful, Pious, London: John Allen and Joseph Barber, 1657; Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys (ed. Richard Lord Braybrooke), New York: Frederick Warne, 1887, p. 57; Ashmole to Lilly, 23 October 1673, Bodleian Libraries, Rawl. D 864, fol. 57r. The fact that stewards were chosen in 1684 for the following year suggests that the society met in 1684 and at least planned to meet in 1685. John Gadbury, Ephemeris, London: Company of Stationers, 1684, sig. C8v.

** I have dated the delivery of Carpenter's sermon to 1656 because the Thomason copy includes an annotation that alters the printing date from 1657 to ‘1 January 1656’. Considering that George Thomason tended to write Old Style dates on pamphlets that used the New Style, this would mean 1 January 1657, suggesting that the sermon itself was delivered the year prior. If my dating is correct, it would mean that Feola's claim that Carpenter's sermon was a direct response to Fox's anti-astrological pamphlet of 1657 may be unfounded. Cf. Vittoria Feola, Elias Ashmole and the Uses of Antiquity, Paris: Librairie Blanchard, 2013, pp. 130–1.

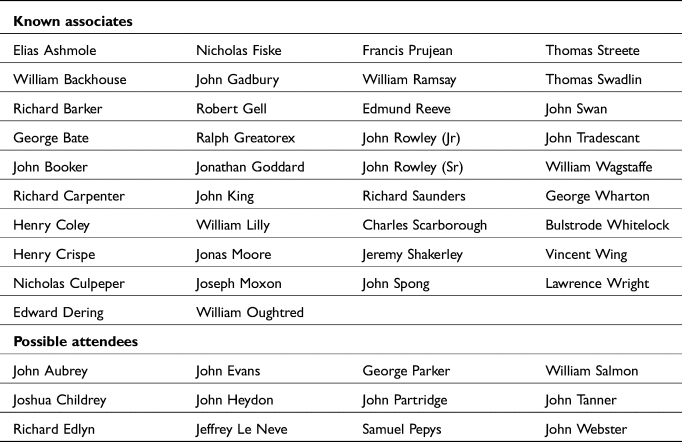

The Society of Astrologers was not a small group. Lilly claimed in 1649 that there were ‘above forty’ attendees that year.Footnote 24 Although we lack an official list of society members, we can reconstruct membership by drawing on various contemporary sources (see Table 2).Footnote 25 Alongside practising astrologers, membership included instrument-makers, physicians and mathematicians with astrological interests. Along with Lilly and Ashmole, leading members included the celebrated physician and herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616–54), as well as the astrologers John Booker (1602–67), George Wharton (1617–81) and Richard Saunders (1613–75). Contemporary pamphlets provide names of additional members. As Feola has shown, in 1657 the Quaker leader George Fox registered several practitioners linked with the society: Lilly, Booker, Saunders and Wharton, but also Charles Scarborough, Jonathan Goddard and several other physicians.Footnote 26 Unknown to Feola, the satirical His Perpetual Almanack (1662) similarly listed twenty-six guests expected at ‘our next Feast’, including many aforementioned names alongside the astrologers John Gadbury, Jeffrey le Neve and John Tanner.Footnote 27 The astrologer and midwife Sarah Jenner, known for her short-lived The Womans Almanack, was likewise named, although it seems unlikely that a woman would have attended the feasts.Footnote 28 The pamphlet also listed the pseudonymous compilers of several popular almanacs, often named for birds: Jonathan Dove, John Swallow, John Woodhouse and Poor Robin.Footnote 29 Some of these were real people whose names continued to be used on ghostwritten almanacs long after their death, while others were entirely fictional.Footnote 30 It is most likely that the collection of names in His Perpetual Almanack was simply a list of popular almanac writers, even if some of those listed had genuine connections with the society. Gadbury, for example, was named as a member by John Partridge.Footnote 31 In any case, the exact make-up of the society doubtless differed at each meeting, and it is probable that Londoners interested in astrology or simply curious about the meetings took part on occasion. Samuel Pepys attended in October 1660, but this was likely a one-off.Footnote 32 Moreover, when the feasts were ‘restored’ in the 1680s, the society's membership was likely altered, especially considering that many former members had now died. All in all, the members we do know of had various political and confessional allegiances.Footnote 33 One contemporary complained that the society indiscriminately admitted sectarians: ‘Presbyterians, Independents, Anabaptists, Quakers, Shakers, Seekers and Tearers’.Footnote 34 Yet in 1649 Lilly claimed that during their annual meeting there was ‘no dispute of King, Parliament, or Army’.Footnote 35 While historians have extrapolated from this the unfounded conclusion that political disputes were banned, it is nonetheless remarkable that they joined forces despite their differences and the deeply strained relationships between many members.Footnote 36

Table 2. Membership of the Society of Astrologers.

Little is known about the society's internal organization. In contrast to the Royal Society, for example, no charter or constitution survives. We know it was predominantly patronized by Ashmole, who financed books produced by its members.Footnote 37 In return, Ashmole acquired the reputation of a scholar and virtuoso, and used his new-found network to support his voracious collecting.Footnote 38 The society also won the patronage of Bulstrode Whitelocke (1605–75), a powerful parliamentarian whom Lilly befriended in 1643.Footnote 39 Some administrative duties in the society were performed by stewards, who were appointed periodically. Ashmole was made ‘Steward of the Astrologers Society’ in 1650, and some three decades later, in 1683, Sir Edward Dering and William Wagstaffe were given the same role. Dering was reappointed the following year alongside Henry Crispe (c.1650–1700).Footnote 40 The steward's role may have been secretarial, as Feola suggests.Footnote 41 Yet while Ashmole certainly acted upon correspondence delivered to the society, which in the first instance was typically directed to the address of Ralph Greatorex's instrument shop, Dering and Wagstaffe – who led busy political lives – were presumably not burdened with this responsibility. It is not known who organized the meetings, although on at least one occasion Lilly played a key role. In July 1651, John Rowley of Luton wrote to Lilly saying that his father had told him that the society ‘intend[s] a meeting shortlye’, and he asked Lilly to give him ‘warning’ of the proposed date so that he could join (the meeting was held one month later).Footnote 42 Invitations may have been distributed in small print or manuscript summonses. Other mathematical clubs used this method; surviving examples suggest that stewards were responsible for issuing, although not delivering, invitations.Footnote 43 Members of the society used similar notes for informal gatherings: in September 1649, Ashmole was invited to dine with Wharton and other astrologers in the Three Tunns pub via a short poetical memorandum.Footnote 44

What were the society's key activities? One historian has characterized the Society of Astrologers as ‘more of a social and trade association than a research motivated group’.Footnote 45 But although the Society of Astrologers did not undertake the systematic investigations we associate with the Royal Society, they nevertheless engaged in the science of the stars in practical and textual ways. On a spectrum of seventeenth-century clubs and associations, we can place the Society of Astrologers in between learned societies and colleges and more trade-based livery companies and guilds. A large amount of material attests to research projects undertaken by the society. For example, they collaborated to produce new astronomical tables and exchanged letters about eclipses and other astronomical phenomena.Footnote 46 In letters addressed to the society in late 1652, William Oughtred described a comet he had witnessed for eleven subsequent nights, and asked for his colleagues’ opinions.Footnote 47 Lilly later printed Oughtred's descriptions alongside the observations of other members, comparing them with his own calculations and reading of comet lore.Footnote 48 John Aubrey, whose astrological interests and close relationships with society members make him a possible candidate for society membership, worked with Ashmole in the 1680s to compile nativities of distinguished men from the records preserved in Lilly's papers.Footnote 49 It seems that more junior members were often put to work by senior members. In a letter to Lilly, the young Rowley asked for both Lilly's patronage and explicit directions about what ‘peece of Astrologye’ he should next ‘Convert into the English tongue’.Footnote 50 Though an admittedly hostile source, William Rowland claimed in his 1651 attack on astrology that ‘it is brought to me by good hands’ that William Ramsay, who was ‘but a Boy’, was ‘set [to] work’ by the society to defend the art.Footnote 51 Jeremy Shakerley likewise worked extensively for Lilly, furnishing him with weather records and various calculations.Footnote 52

Society members engaged closely with mainstream mathematical culture. Booker, licenser of mathematical publications from the 1640s, was in close contact with astronomers at Gresham, who sent him up-to-date observations.Footnote 53 Oughtred taught many Royal Society mathematicians and maintained relationships with leading practitioners. Many society members were primarily specialists in mathematical arts other than astrology, and in their astrological publications advertised their non-astrological books as well as private mathematical tuition.Footnote 54 Vincent Wing, whose circle included the mathematicians and astronomers John Flamsteed, Laurence Rooke and William Leybourne, among others, promoted his surveying services in his almanacs, telling readers he was also ‘ready to teach … several other branches of the Mathematicks’.Footnote 55 It is well known that there was considerable overlap between instrument-makers and learned natural philosophers and mathematicians in this period.Footnote 56 As an example of a similar crossover between astrologers, practical mathematicians and instrument makers, when advertising his surveying textbook in his astrological almanac, Wing told his readers that if they wanted access to ‘the Instruments there described’, they could find them at Walter Hayes's instrument shop.Footnote 57 Members also publicized mathematical instruments built by their society colleagues, such as Oughtred's dials and Moxon's globes.Footnote 58

In the later seventeenth century, mathematical practitioners endeavoured to increase public knowledge of their fields through popular books and public lectures and demonstrations.Footnote 59 The Society of Astrologers likewise conducted a campaign to democratize astrological knowledge. Their efforts included private tutoring.Footnote 60 The postal service was a useful additional medium. Society members corresponded with amateur astrologers, providing advice on casting horoscopes, interpreting phenomena, and making prognostications.Footnote 61 In 1647, Lilly and Booker received letters ‘from sundry parts of this kingdom’ about a recent parhelion; Lilly used his almanac for that year to provide an explanation.Footnote 62 While Feola concludes that these letters do not technically constitute a ‘network’ because Lilly's correspondents outside London only ever sent him just one letter, it must be noted that the letters in the Ashmole archive in the Bodleian Library are only a small proportion of what Lilly received; we know this because Lilly often published letters that no longer survive in manuscript.Footnote 63 The print market was central to the society's operation. Fiske believed that one of his key tasks as a member of the society was to republish, and thus make more available, older English astrological works.Footnote 64 As Feola has shown, the society also translated Latin astrological texts. In 1650 William Backhouse coordinated a workshop in his Berkshire home, where several members translated such texts into the vernacular.Footnote 65 Shakerley worked on translations of Ptolemy's Tetrabiblos for Lilly in the late 1640s.Footnote 66 A complex premodern science, astrology was largely locked away in Latin tomes until society members offered accessible English accounts. Lilly's pedagogical Christian Astrology (1647), for example, was widely read, and Lilly received letters from budding astrologers thanking him for it.Footnote 67

In sum, the Society of Astrologers was a product of the mathematical culture bourgeoning in London in this period. The society joined their mathematical colleagues in a programme to expand public mathematical knowledge. In a context in which astrology was under threat in educated circles, the society declared that its main goal was the restoration, or resuscitation, of their field. In a letter to Whitelocke transcribed in the Appendix below, the society explained that throughout history, astrology ‘hath had her Wax, & her Waine, her Assertors & Assassinates’. With Whitelocke's help, the society would ensure that it was restored to a respected state.Footnote 68 This involved activities not only to democratize the art, but also to legitimize it. As I argue below, the society endeavoured to accomplish the latter by establishing astrology as a divine art with an august history.

Sermonizing at the Society of Astrologers

The Society of Astrologers attempted to revive their field with a robust response to attacks mounted against it by ministers and theologians. To this end, the society actively sought out relationships with preachers who were sympathetic to astrology. The Society of Astrologers’ network therefore included not only mathematical practitioners and aspiring prognosticators, but also the local clergy. Astrology had always been controversial in Christian Europe, but widespread acceptance was facilitated by its ambiguous biblical status. Genesis 1:14 pointed to God's intended use of celestial bodies as signs, and Job 38:31 highlighted ‘the sweet influence of Pleiades’. But scripture seemed to object to astrology in passages like Leviticus 19:26 (which cautioned against divination) and Jeremiah 10:2 (which disparaged the pagans who were ‘dismayed at the signs of heaven’). Society members were aware that many English men and women were ‘prejudiced or dis-affected unto Astrology’ because contemporary ministers told their auditors it was unlawful and pagan.Footnote 69 The society therefore appointed their own preachers to exploit these biblical ambiguities, elevating scriptural evidence that seemingly supported astrology, and contesting passages that did not.

The society convinced five local ministers to support their cause. While society members had their political and religious differences, their preachers were all royalists and members of the English Church. This may have been intended to help to distance the society from religious and political radicalism.Footnote 70 Many preachers were strategic choices, even if Curry dismisses them as obscure.Footnote 71 Before preaching two sermons to the society, Robert Gell (1595–1665) was a popular preacher and chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury. From 1641 onwards, he was a clergyman at St Mary Aldermary, a rich London parish with parishioners sympathetic to his astrological interests.Footnote 72 As Gell acknowledged, the society ‘made choice of me … as being one of your judgement touching your Art’.Footnote 73 Thomas Swadlin (1599/1600–69), another well-known society preacher, had a loyal following amongst Laudians at St Botolph's, Aldgate. Ashmole heard Swadlin preach in October 1646, which likely led to his invitation to preach to the society a few years later.Footnote 74 Other society preachers were Laudians: Edmund Reeve (d. 1660), who taught biblical languages in London, and John Swan (1605–71), minister in Cambridgeshire and Booker's personal friend.Footnote 75 Only Richard Carpenter (1604/5–70) offered a more complex story; he declared himself a Roman Catholic in 1625, only to apostatize in a recantation sermon in 1637.Footnote 76 At least Gell, Swadlin and Swan were known to society members before they preached.Footnote 77 In Reeve's case, however, the society seemed eager to vet his sermon before its delivery. In a prognostication of the 1652 eclipse dated 10 March 1651, Lilly claimed that a sermon on Jeremiah 10:2 would soon be forthcoming. He then included a two-paragraph quotation from Reeve's sermon, some five months before Reeve delivered it.Footnote 78 As one sharp reader noticed, either Lilly ‘did by the Stars foresee, that such a Sermon … should be preached’, or else the preacher, ‘having penned it … did tender a Copy of it to M[aster]. L[illy]. his Client … with a purpose to dispose of it, as he should either like or mislike it’.Footnote 79

The society's sermons were public affairs. When delivering his sermon, Swadlin addressed himself to those who ‘professe yourselves Students in Astrology, and for all others, who are here assembled’.Footnote 80 One contemporary described Swan's sermon as ‘prepared for, and preached unto a popular Auditorie’.Footnote 81 Gell remarked that before his sermon appeared in print, he was censured by people who were ‘hired to take notes’ during its initial delivery.Footnote 82 As a result of the sermons’ public nature, the society became well known in popular culture, as attested by the references made to it in the 1650s and 1660s.Footnote 83 That the sermons had an image-management function is suggested by the fact they were the only material published explicitly in connection with the society. One sermon was printed even though it was never delivered due to the preacher's illness.Footnote 84 Nathaniel Brooke, a stationer who worked closely with Ashmole and Lilly, printed and distributed most of the sermons.Footnote 85 Brooke printed many works by society members, including a medical lecture delivered to the society by Culpeper in the early 1650s.Footnote 86 A selection of the society's sermons was later sold together as Five Several Sermons Preached for and Dedicated to the Society of Astrologers (1684), at the ‘command’ of Dering and Crispe.Footnote 87 Yet the society had to campaign its preachers extensively to ensure their cooperation. Gell admitted he was ‘not easily perswaded to speak in publique’ in defence of astrology, and did so only after several society members ‘importuned’ him. He was then ‘more averse [than] I ever have been’ to ‘exposing my thoughts in print’, but the society eventually convinced him.Footnote 88 Even Lilly admitted that Gell only agreed to ‘suffer that learned Sermon of his … to be printed’ at ‘our many importunities’.Footnote 89

The subject of the sermons was the legitimacy of astrology for Christians. Historians have tended to sideline the society's sermons as unoriginal and therefore uninteresting. While Curry rightly suggests that they would have been unconvincing for Puritans and Presbyterians, he unfairly dismisses them as ‘hackneyed arguments’, ‘standard Biblical defences of astrology, many centuries old’.Footnote 90 While the preachers’ arguments were largely unoriginal, their age was the point: the fact that historical Christian leaders could be called upon was key. Besides, their arguments made sense in light of the obstacles astrology was facing: astrology and pagan superstition were increasingly connected in the public imagination.Footnote 91 In contrast, the sermons revealed astrology as a divine, Hebraic art, which God had used to bring the Magi to Christ. This strategy sheds light on the society's extensive use of the term ‘restore’ to describe their project: implicit in the ‘Restauration of Astrologie’ is the assumption that there existed at some point in the art's long history a Golden Age that could be reinstated.Footnote 92

The society's preachers emphasized astrology's Hebraic origins. This was hardly an original claim. Various Jewish and early Christian sources explained how Abraham had expertise in astrology and astronomy and introduced both to the Egyptians.Footnote 93 Renaissance introductory lectures on scientia stellarum used biblical mytho-histories to display its legitimacy and splendour.Footnote 94 Antiquity was associated with religious and philosophical purity in these narratives. The preachers followed this convention, maintaining that the biblical patriarchs excelled in astrology. Astrology's root was ‘not Idolatrie, but Innocency; Adam in Paradise was the Father of this Art’.Footnote 95 Genesis 4:20–2 provided useful evidence in its suggestion that while Cain and his children invented the inferior arts, the most noble arts (i.e. those considering the heavens) were developed by the sons of Seth. In Jewish Antiquities, Josephus emphasized Seth's role in the invention of astrology, explaining how his sons wrote their learning on pillars to ensure its longevity.Footnote 96 Thus the preachers maintained that Adam founded astrology, but Seth's children ‘ripen'd it into an Art or Discipline’. In his sermon, Carpenter referred to the society as the ‘learned children of Seth’.Footnote 97 The society exploited this tradition in their letter to Whitelocke, claiming that they hoped astrology would remain ‘like so many Pillars, whereon are Engrav'n the Principles of Arts & Sciences to preserve them from … the Injuries & Affronts of time’.Footnote 98 Gell also followed Philo and Acts 7:22 when he argued that Moses’ skill in ‘Egyptian wisdom’ included astrology.Footnote 99 Similarly for Swadlin, Solomon was ‘the best Astrologer the world ever entertained’.Footnote 100 The fact the patriarchs were astrologers proved that the art was both ancient and condoned by God.Footnote 101

A second central argument of the sermons revolved around Matthew 2:1–12, which described how ‘Magi’ from the east followed a star to see Christ in his manger. Commentators had long drawn attention to the similarity of this text to Numbers 24:17 (‘there shall come a star out of Jacob’), one of several oracles of the prophet Balaam that was seen as a messianic prophecy. These parallels allowed commentators to link the Magi and Balaam, who was said to dwell in the east; this explained how the Magi had known the star's meaning.Footnote 102 Some of the preachers went so far as to suggest that the Magi were themselves descendants of Balaam (himself kin to Jacob). After all, Balaam lived in Arabia, which was east of Jerusalem and boasted native products of gold, frankincense and myrrh.Footnote 103 This was crucial evidence for the preachers for two reasons. First, by using astrology, God had ‘vouchsafed a speciall respect unto the well-minded Students in the Starres’.Footnote 104 God accommodated himself to the gentiles, using the stars to literally and allegorically bring them to Christ.Footnote 105 Second, the text implied that a tradition of pure astrology had been handed from the Hebrews to the Magi, which again served to highlight its divine history.Footnote 106

The sermons acknowledged that although astrology had pure roots, it had been subject to corruption during its life. A critical issue was idolatry. Gell admitted that many pagan astrologers had become ‘worshippers of Stars’.Footnote 107 Carpenter singled out Zoroaster as ‘the Father of those who perverted the noble Science of Astrology’.Footnote 108 But the preachers argued that astrology was not necessarily yoked with pagan worship. Swadlin explained that he knew from first-hand experience that some astrologers engaged in demonic activity, but this was not representative of ‘the true Astrologer’.Footnote 109 The preachers knew that pagan astrology was at risk of being determinist, a theologically sensitive issue. Thus the preachers found the maxim astra non necessitant sed inclinant useful, for it clarified how astrologers could predict inclinations, which could then be heightened by ‘holy Ambition’ or thwarted by ‘good Education’.Footnote 110 As Reeve wryly noted, while some claimed that astrology should be rejected because of these historical corruptions, ‘may not by the same reason the Studie of sacred Theologie bee omitted, seeing that not few errours have entered into Bookes of the same?’Footnote 111 Astrology had at times been corrupted by idolatry, the preachers suggested, but original, pure astrology could still be salvaged. ‘Purge away the dross, and keep the gold’, Swan declared.Footnote 112

After the sermons were printed, society members referred to them repeatedly. Citing a sermon became shorthand that allowed the astrologers to eschew in depth theological arguments in favour of a quick response to their opponents.Footnote 113 The sermons also enabled society members to play different preachers off each other; Gadbury, for example, wrote in 1654 that while some ministers were certainly against astrology, Gell, Reeve, Swadlin and ‘many more’ were greatly in favour of it.Footnote 114 Society members consistently referenced astrology's divine origins in their own books. For Lilly, God's angels taught astrology to the first men, who then trained their descendants.Footnote 115 Booker wrote a poem for Gadbury's Doctrine of Nativities (1658), which declared, ‘Adam first Man, found out Stars Influence, / And taught his Sons’.Footnote 116 Ramsay (who, believing he was descended from the Egyptians, spelled his name ‘Ramesey’) argued throughout his oeuvre that astrology had ancient and divine foundations.Footnote 117 In Lux Veritatis (1651), he included a genealogical table of hundreds of ‘Astronomers and Astrologers from the Creation’, which began with the Hebrew patriarchs.Footnote 118 Ramsay copied this list from Sir Christopher Heydon, a hero of the society, but added to it the names of several society members.Footnote 119 Such a list was designed not only to highlight famous past practitioners of the art, but also to show a line of succession since Adam. As one contemporary remarked, the society and its preachers ultimately laboured to make the biblical patriarchs ‘member[s] of the society of Astrologers’.Footnote 120

Contemporary responses

In August 1650, the Mercurius Politicus newspaper included a review of the recent feast of the Society of Astrologers. According to the anonymous reviewer, they

saw more of true piety this day in a Lay-Congregation, than ever was found in the Scotified Clergy: It was a day dedicated to Devotion, and friendly Converse, by the learned Society of Astrologers, who met together at Aldermary Church in London … After which, they Treated each other civilly at dinner at Painters-Hall; where was so grave an Appearance of Doctors and Students in several Faculties, as made up a compleat Academy.Footnote 121

This glowing report notwithstanding, the majority of the surviving evidence suggests that, in spite of their efforts, the society's public relations campaign failed to convince many. Historico-religious attacks continued to be mounted against astrology. Unfortunately for the society, their enemies had on their side the consensus of leading scholars who, drawing on the discoveries of Renaissance humanists, increasingly located astrology's origins not amongst the biblical patriarchs, but instead within ancient paganism.Footnote 122 To name one prominent and influential example, in his famous Disputationes adversus astrologiam divinatricem (1496), Giovanni Pico della Mirandola placed astrology's origins squarely in Chaldea and Egypt, arguing that these eastern nations did not deserve admiration because of their idolatry and superstition.Footnote 123 This revisionist account was incredibly successful, and was taken seriously by leading seventeenth-century intellectuals. In England, the experimentalist par excellence Robert Boyle critiqued astrology principally on historical grounds: the art was a product of idolatrous eastern star worship.Footnote 124 This scholarship also trickled down into more popular anti-astrological works. In his assault on the society, Fox claimed that astrology stemmed from idolatrous Egyptian practices.Footnote 125 In 1652, John Gaule argued that astrology began life ‘as a Religion, amongst the vilest of Heathenish Idolators’.Footnote 126 Gaule professed himself shocked that the astrologers had the gall to ‘assemble … and set up themselves for a society; amidst all others discociations [sic], and distractions’ during the Civil War and Interregnum.Footnote 127 Gaule explained that in the second century, two preachers, Fugatius and Damianus, had abolished native British astrology. Meanwhile, the society's preachers were now aiming to restore ‘the Religion, as it was held and used among Pagans’.Footnote 128

The society's sermons elicited refutations from rival ministers. In 1653, the ageing clergyman Thomas Gataker (1574–1654) rebutted Swan's sermon on Jeremiah 10:2. Gataker had recently published annotations on the same passage, and he now chastised Swan for misinterpreting it.Footnote 129 Gataker's Vindication was also directed at Lilly, who in his Annus Tenebrosus (1651) had dismissed Gataker's annotations on this verse as a waste of ‘a whole side of paper’ that would soon be superseded by the ‘exposition of a reverend Minister … equall in years to Mr. Gataker; and in true divinity and knowledge of the Orientall tongues, far surmounting him’.Footnote 130 Lilly then included the excerpt of Reeve's sermon mentioned above which interpreted this passage as favourable to astrological prognostication. Gataker was understandably riled up by these comments, and Lilly's failure to provide the author and title of the sermon left Gataker and his friends ‘to seek after a needle in a bottle of hay’.Footnote 131 When Gataker eventually came across Swan's sermon of 1652 on Jeremiah, he assumed that it was the sermon to which Lilly had referred. Gataker therefore dedicated over two hundred pages to refuting Lilly and Swan, and his Vindication was printed with separate title pages for seven different booksellers across London, likely in expectation of a large readership. Gataker had a good deal of ammunition against the Society of Astrologers, as by this point it had become clear that the 1652 eclipse and its effects were not nearly as bad as the astrologers had predicted. But Gataker spent most of his time questioning Lilly and Swan's claims for the antiquity and divinity of astrology. Swan had argued that Jeremiah's censure of pagans who were ‘dismayed’ at heavenly signs taught Christians to be unafraid of ostensibly frightening astrological predictions. For Gataker, however, the correct reading was that astrology was a direct path to pagan idolatry.Footnote 132 After all, Gataker asked, ‘whence had people these frivolous fancies and superstitious conceits?’Footnote 133 Lilly and ‘his Complices’ claimed that Adam and Abraham were the first astrologers, but in reality it was the Egyptians, Chaldeans and other ‘idolatrous Pagans’.Footnote 134

Similarly, when John Raunce took aim at Gell's second society sermon, he accused the preacher and his auditors of being ‘deluded with a superstitious and heathenish opinion’, and for striving to delude others.Footnote 135 Raunce claimed to see through the astrologers’ strategy: ‘we are not able to prove Astrologie a lawfull and honest Art’, so we have employed preachers like Gell to ‘prove it for us’.Footnote 136 Their endeavours were in any case a waste of time, Raunce argued, as astrology was clearly an art with origins in all things idolatrous, heathen and diabolical.Footnote 137 The Society of Astrologers, armed with outdated mytho-histories, was seemingly fighting a losing battle.

While Feola has claimed that Fox's pamphlet was ‘the only printed attack openly directed against … the Society of Astrologers’, the society in fact received numerous direct attacks.Footnote 138 Many were satirical, and ridiculed the society's dubious morals. His Perpetuall Almanack poked fun at their feasts and their manipulation of clients. In the guise of giving serious advice on ‘how to judge of things happening suddainly whether they be good or ill’, the author explained that finding twenty shillings on the ground should be considered a good thing, while a deadly fall from a horse should be considered a bad thing.Footnote 139 Another pamphlet, primarily concerned with satirizing the skill of coal dealers in inflating prices, imagined a fruitful collusion between coal merchants and Lilly ‘and the rest of the star-gazers’. If a coal dealer could encourage the astrologers to predict ‘snow and frost and flabby cold weather’, this could ‘bring in our Customers the faster’. For this service, the coal dealer would ‘finde in my heart to spare halfe a chaldron of Coales to bee distributed amongst the star-gazing fraternity, to warm their Noses at their Critical Conventions’.Footnote 140 To construct a respectable image for the society in response to popular ridicule, the engraver Thomas Cross (fl. 1632–82) was engaged to produce portraits of several members that depicted them in studious aspect, surrounded by astrological books, mathematical instruments and depictions of the heavens.Footnote 141 Yet their efforts were lampooned in the broadside Lillies Banquet: or, the Star-Gazers Feast (1653), which boasted an engraving of a scholar at work on an astrological book, except that the scholar was an owl, complete with gown and ruff. This was a play on the symbolic folly of the owl common to satirical literature.Footnote 142 Following the image were eleven stanzas of verse recommending a complex feast suitable for guests of all Zodiac signs, brimming with sexual references.Footnote 143

Other attacks on the society sought to undermine their astronomical credibility. Black Munday Turn'd White (1652) refuted the predictions of ‘Mr. Lillie, Mr. Culpeper, and the rest of the Society of Astrologers’ concerning the 1652 eclipse. After reporting grave errors in their calculations, the author scolded them for not being better skilled in ‘the speculative part’ of the science of the stars (astronomy) before they ‘adventured on the Practick’ (astrology).Footnote 144 The pamphlet also questioned the society's piety. Lilly's almanac on the eclipse included ‘unchristian like words’ and made references to heaven when the author was sure ‘Heaven hath little to do with him, since he hath so much to do with Hell’.Footnote 145

Conclusion

The Society of Astrologers was a last-ditch effort to save astrology from decline. Despite their often fractious relationships, members of the society came together in a unified attempt to resuscitate the art through programmes of public education and religious legitimization. The first should be considered part of the world of contemporary mathematical culture. Excellent recent studies have taught us much about practical mathematics in this period, and have encouraged a ‘move away from a concentration on the Royal Society’.Footnote 146 However, astrology remains conspicuously absent from these accounts.Footnote 147 The evidence offered here suggests a more comprehensive account of this important aspect of seventeenth-century intellectual life and requires us to consider astrology and practical mathematics in tandem.

The Society of Astrologers endeavoured to vindicate their art through apologetic sermons. In all treatments to date, the society's sermons have either been overlooked or dismissed as a ‘gloss of sanctity’.Footnote 148 Taking the establishment of the sermons seriously, this article has shown how they aimed to locate astrology within an authentic and religiously sound historical tradition. In this the society in fact proceeded in a comparable way to the Royal Society. Wright argues that while the Royal Society's main preoccupation was ‘the explanation of puzzling natural phenomena’, the Society of Astrologers’ main concern was the legitimization of their art.Footnote 149 Yet historians have since demonstrated the Royal Society's necessary interest in justifying experimental natural philosophy.Footnote 150 Both societies remind us that learned sodalities often formed not at the height of their field's success, but when its members felt it was in jeopardy. When faced with a crisis of intellectual identity, the early Royal Society responded in part by constructing historical defences of experimental science.Footnote 151 On first glance a key difference between the two societies might be that while astrology was millennia old, the new experimental philosophy was just that – new. Yet proponents of the new science also located their methods within the long history of philosophy. That the historical rhetoric of both societies fell short was in good part because they did not rely on the best and most up-to-date historical scholarship.Footnote 152

The Society of Astrologers disbanded in the mid-1680s. The question of why this occurred is tied to the larger issue of astrology's decline more generally in this period, which remains an area of active research.Footnote 153 In terms of the society more specifically, Curry has argued that its dissolution was the result of its members’ radical politics, which were unpalatable after the Restoration.Footnote 154 Feola's account of the society's politico-religious diversity challenges this somewhat, although the society's ‘real’ politics is a different issue to their reputation in the eyes of the public.Footnote 155 Though it is tempting to point to experimental philosophy and its institutionalization in the Royal Society, this too cannot offer a full answer.Footnote 156 In 1697, Gadbury asked the Royal Society why they did not patronize ‘Experiments in Astrology’.Footnote 157 The answer may partly lie in Michael Hunter's suggestion that the early Royal Society avoided discussion of magic and occult practices because its fellows’ views were so divided.Footnote 158 Several Royal Society fellows were, after all, also members of the Society of Astrologers.Footnote 159 It is in any case probable that by democratizing astrology, the society unwittingly helped redefine it as ‘vulgar knowledge’, thereby undermining its credibility and the society's own scholarly pretensions.Footnote 160 Yet a simpler explanation for the end of the society might be that many of its leading associates had died by the 1680s.Footnote 161 Already in 1669, Gadbury's biography of Wing included a poem ‘On the Death of So Many Eminent Astrologers’.Footnote 162 And, in 1677, Ashmole told Lilly rather melancholically that he had recently ‘summoned the remainder of our old Club about Strand Bridge that are left alive’.Footnote 163 Surviving society members, moreover, were becoming preoccupied with other things: Ashmole with the Royal Society, for example, while Lilly, for his part, moved to the country following the fallout from his scandalous prediction of the Great Fire of London. Lack of direct contemporary testimony renders the issue perhaps unanswerable, at least by a single explanation. The attacks discussed here, however, are likely representative of a wider sense that the society had failed to achieve religious legitimization. The Society of Astrologers, armed with an out-dated and ineffective arsenal, struggled to resist astrology's marginalization.

Appendix

Document: The Society of Astrologers to Bulstrode Whitelocke, 24 April 1650, Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, MS Ashmole 423, fol. 168r–v.

For the Right Honorable the Lord WhitlockFootnote 164

Right Honorable

Such hath ever bin the happy Fate of Learning, that although in her restlesse Progresse through the World she hath sometimes mett with Declinations & Eclipses, yet has she still bin supported by the favour & Munificence of Noble Patrons; whose worth wee find transmitted to Posteritie, by the Gratfull Penns of every Age.

Amongst other, Astrology, (a Divine-science, & no lesse Necessary then Famous for the Dignity of her Admirers) hath neverthelesse incurred the Brunt of all Ages & Humors: she hath had her Wax, & her Waine, her Assertors & Assassinates.

And considering how great an Obligation is due to such Generous spirits, whose Devotion or Bounty, renders them like so many Pillars, whereon are Engraven the Principles of Arts & Sciences to preserve them from the Deluge, (the Injuries & Affronts of time.)

Wee, (seriously weighing your Lordships Noble & Pious Disposition, as to all manner of good and profitable Learning; so, more especially to that (untill of late despised) part, Astrology;) assume the boldnesse to present you with our Tribute of Thankes for your good Affection, & the great Encouragement you have given to the Advancement thereof, more then others.

And the rather, because it is a Science was hardly knowne to this (herein unhappy) Segment of the Terrestriall-Globe: Or (if at all) but lodged in the retired bosomes of some few, untill made publique to the Benifitt of this Nation, & the cleare vindication of it selfe from the Scandalls of the Ignorant and Malitious, by the dexterous Scrutiny and Paines of Master Lilly: whose deservings therein are indeed very great, but your Noblenesse most to be Celebrated; who (as himselfe ingenuously acknowledges) not only ledd him by the Hand when first he stept abroad; but have ever since afforded him your Countenance & Assistance, in the whole Course & Conduct of his Studies: the most Signall Productions whereof, (for the Ease and Benifitt of all Students in that Science;) weare your name, as theire greatest Badge of Honour, & Bulworke of Protection.

Yet should wee not imagine our Thread-bare-Thanks a Present acceptable, for so truly-Noble Favours, but that they come to the hands of so Worthy a Personage as your Lordshipp whose Genus and Genius make you verè Nobilem et Notabilem,

Unde magis magisque Tuj nunc Gloria claret;Footnote 165

And that therewithall, wee cannot but Blesse & Magnify God for you, as being every way so Eminent for Honorable Endowments, & so completly fitted with an Heart open to all Noble Overtures, aiming at the further Advancement of what is Learned and Ingenious: And (which we count the ἁκμὴ [sic]Footnote 166 of all Gratitude) that your Lordshipp may be ever blest with an happy Encrease of Favour with God and Good-men, to make your Name and Fame flourish on Earth

_______ Donec fluctus formica marinos

Ebibat, & totum Testudo perambulet Orbem;Footnote 167

And be afterwards æternally blest in Heaven, you shall never want the unfeigned Devotions of

Your Lordshipp's Humble Servants

The Society of Astrologers, of London

Aprilis 24 die Labente Anno 1650

Acknowledgements

This article began life as a coursework essay for an MSc paper on Astrology in the Medieval and Early Modern World at the University of Oxford; much gratitude goes out to the instructors, Silke Ackermann and Stephen Johnston, for igniting my interests in the history of astrology. Further archival research was generously supported by the Royal Society, under a Lisa Jardine History of Science Grant. I would like to thank the archivists at the Royal Society and the Bodleian Library for their assistance. For their comments on the paper, I would like to thank Peter Harrison, Dmitri Levitin and the two anonymous referees.