Michael Jordan supposedly once said that the reason he did not want to endorse a candidate in a North Carolina Senate race was because “Republicans buy sneakers too.”Footnote 1 The logic seemed impeccable: if the goal was to sell sneakers, why risk talking about something that might turn off potential customers?Footnote 2 Yet even as we wrote this article, Taylor Swift—a crossover country-pop star—decided to announce her endorsement of not one, but two, Democrats running for office in Tennessee in the 2018 US midterm elections. Moreover, she made this announcement on Instagram, in a post that has since been liked by more than 2.16 million people.Footnote 3 Today, the name of the game for celebrities on social media is just this kind of engagement with fans. But the question still remains: If you want to engage with fans, why risk talking about political topics that are bound to alienate some of them?Footnote 4

In the era of the first celebrity-in-chief of the United States, this question should be of more than just passing interest to political scientists. There is now ample evidence of declines in trust in institutions, mainstream media, and political parties in multiple established democracies.Footnote 5 With the “old guard” suffering from a credibility deficit, is it possible that individuals who possess a cultural cachet may be substituting for traditional elites in some aspects of public life? In the aftermath of one celebrity successfully running for US president, there is an expectation that more celebrities may enter politics directly or may choose to contribute to mobilizing voters. But to what degree is that impressionistic account accurate? Is it actually the case that celebrities no longer care if Republicans buy sneakers?

In this article, we seek to provide answers to these questions. More specifically, we derive three hypotheses from the extant communications and political science literature regarding celebrity behavior in politics:

H1: Social media users’ engagement with celebrities’ political tweets will be lower relative to typical (nonpolitical) tweets.

H2: Celebrities endorsing major party candidates on social media should be more likely to act as critics than as cheerleaders.

H3: Celebrities’ social media posts that criticize opponents should elicit a higher volume of retweets than social media posts that endorse their favored candidates.

Although the first hypothesis is most accurately described as testing the conventional wisdom—or at least the conventional wisdom according to the Michael Jordanesque folklore—the second and third collectively introduce a new theoretical framework for thinking about celebrities: once they choose to enter the political arena, by and large, they act like – and are treated like – other well-known political actors.

Social media, with its rich collection of interactions between celebrities and their followers, as well as the digital footprints they leave behind, represent a perfect platform on which to test these hypotheses. To this end, we collected approximately 3,200 tweets from each of 83 celebrities that we could confirm supported either Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, or Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential election campaign.Footnote 6 Using these data, we document how often American celebrities talk about politics on their own profiles, exposing often politically uninterested citizens to political content.

As it turns out, many celebrities are quite vocal about their political views. Knowing that not all their fans—and potential customers—will agree with their political stances, they are still apparently prepared to discuss politics. Although celebrities have not become all-around political activists, some can be viewed as amateur pundits. Both during and after the presidential campaign, many spoke about politics occasionally and, perhaps surprisingly, appeared not to arouse high levels of annoyance or disapproval among their followers. Indeed, political content from celebrities has not led to less engagement among social media users. In other words, we do not ultimately find much support for the Republicans-buy-sneakers hypothesis, counter to what has been the prevailing wisdom.

More broadly, we also shed light on the relationship between celebrities, politics, and their followers on social media. We test hypotheses regarding the subject matter of tweets (regarding one’s own candidate or an opponent, H2) and how followers respond to tweets about the celebrity’s endorsed candidate or opponent (H3). Although some of the evidence is mixed, in general we find that while celebrities do not shy away from tweeting about political opponents, during a campaign they are more likely to tweet about their supported candidate than about opponents and thus are not exclusively acting in the traditional “attack dog” manner often ascribed to campaign surrogates. However, we do find that tweets about opponents generate more engagement from followers on Twitter than tweets about the endorsed candidates, so it is possible that celebrities are not actually acting in their own best interest in discussing their preferred candidate, at least insofar as the goal is engaging their followers.

In this article we make several original contributions. Theoretically, we provide a road map for linking our expectations about celebrity behavior in politics to the communications and political science literatures. Substantively, we present, to the best of our knowledge, the first falsifiable empirical test of whether celebrities bear a cost for political endorsements in terms of online engagement. Although this hypothesis is not supported by our data, we provide at least a partial explanation for why celebrities may be becoming more engaged in politics. Our argument is that, on Twitter at least, posting about politics may help celebrities generate more attention than traditional posts. However, our analysis also shows that celebrities are not necessarily rushing to embrace the attack dog role traditionally assigned to campaign surrogates. At an even more basic level, we document systematically that many celebrities were mobilized during the 2016 US presidential campaign and continued to talk about politics well into 2017–18.

We proceed as follows. In the next section, we define what we mean by celebrity, summarize the relevant literature, and introduce our three hypotheses. We then describe our data and data collection process and present our empirical findings. In the final section we summarize our main findings and offer directions for future research.

Literature and Hypotheses

David Marshall emphasizes two key features of celebrities—operating on the public stage and being known to large portions of the population:

In the public sphere, a cluster of individuals are given greater presence and a wider scope of activity and agency than are those who make up the rest of the population. They are allowed to move on the public stage while the rest of us watch. They are allowed to express themselves quite individually and idiosyncratically while the rest of the members of the population are constructed as demographic aggregates. We tend to call these overly public individuals celebrities (emphasis in original; Marshall Reference Marshall2014, xlvii).

By acquiring visibility through media and showcasing their public and private lives, celebrities maintain affective bonds with their audiences while cultivating the public as both consumers and citizens (Marshall Reference Marshall2014). The codes, styles, and tactics through which celebrities achieve these goals have increasingly percolated into the political domain, as leaders present themselves as public and private personae to embody the feelings of their constituents (Street Reference Street2012). The logic of celebrity culture has also spread throughout other domains, such as business, with the rise of “celebrity CEOs” (Littler Reference Littler, Redmond and Holmes2007), and science, with “celebrity scientists” (Fahy Reference Fahy2015). The rise of Donald Trump as a celebrity in business, entertainment, and politics illustrates how versatile the logic of celebrity culture can be (Street Reference Street2018).

Celebrities maintain their status only insofar as audiences are willing to pay sustained attention to them. Turner (2014: 3) pushes this logic to the extreme by arguing that “the modern celebrity may claim no special achievements other than the attraction of public attention.” It is primarily the media that bestow fame and celebrity status (Rojek Reference Rojek2004). Classic studies and definitions of celebrities have focused on mass media, chiefly television, radio, and newspapers. The movie and music industries, popular television, and sports all emerged thanks to the promotional backbone of mass communication, advertising, and public relations. More recently, social media have enabled celebrities to expand their reach and messaging toolkit, directly and continuously delivering to fans a rich and timely selection of personal stories (Turner Reference Turner2014).

Celebrities are mainly involved in commercial and promotional activities (Wernick 1991; Turner Reference Turner2014). Hence, celebrities have been equated with “human entertainment” (Gabler Reference Gabler2011) that “involve[s] the commodification of reputation” (Kurzman et al. Reference Kurzman, Anderson, Key, Lee, Moloney, Silver and Van Ryn2007: 353). Celebrities derive income and prestige from their ability to promote themselves, the cultural products they appear in, and the goods and services they endorse. Their likelihood of success, in turn, depends on whether they can maintain the goodwill and affection of the public. To this end, the affective bonds that celebrities create with fans need to be constantly maintained.

Celebrities play an important role in the crowded public spheres of contemporary Western democracies. As citizens’ attention is increasingly saturated (Webster Reference Webster2014), individuals are incentivized to select contents and sources aligned with their interests and preferences. These selective pressures may reduce the variety of sources and topics about which individuals learn; citizens who prefer entertainment to news may therefore avoid public affairs and become less politically knowledgeable and engaged as a result (Prior Reference Prior2007). However, some counterbalancing mechanisms provide new avenues by which citizens who are relatively uninterested in politics may still encounter political content. There is evidence that large numbers of social media users stumble on political news by accident when they go online for other reasons. In turn, the information that social media users accidentally see can enhance their political knowledge (Bode Reference Bode2016), increase their perceptions of the saliency of certain issues (Feezell Reference Feezell2018), and lead to higher levels of online political participation, particularly for less interested voters (Valeriani and Vaccari Reference Valeriani and Vaccari2016).

When television dominated political communication, scholars argued that political content on entertainment programs helped reach voters who did not generally follow the news, providing helpful information to inform their voting decisions (Baum and Jamison Reference Baum and Jamison2006; Delli Carpini and Williams Reference Delli Carpini, Williams, Bennett and Entman2001). By the same token, in the digital age, celebrities may help channel political content toward social media users who do not otherwise engage with politics. For this to happen, however, celebrities must meaningfully address some political topics on their social media profiles. To shed light on these hitherto unexplored dynamics, we explore the ways in which celebrities engage with electoral politics, the strategies they employ, and the response of social media users who encounter their messages.

Marsh and colleagues propose a five-category typology of how celebrities interact with politics. They differentiate between “celebrity advocate,” “celebrity activist/endorser,” “celebrity politician,” “politician celebrity,” and “politician who uses others’ celebrity” (Marsh, Hart, and Tindall Reference Marsh, Hart and Tindall2010: 327). Street (Reference Street2012) argues for a simpler distinction between “the traditional politician who emerges from a background in show business or who uses the techniques of popular culture to seek (and acquire) elected office” and “the celebrity who seeks to influence the exercise of political power by way of their fame and status.” We focus on the second of Street’s categories—celebrities who aim to influence politics—and in particular on Marsh and colleagues’ category of “celebrity activists/endorsers”: “high-visibility figures from traditionally non-political spheres offering financial and/or public support for a specific political candidate and/or party” (2010: 327).

There is evidence that celebrities have some ability to affect the public’s perceptions and evaluations of candidates and political causes they support. In 2007, television talk show star Oprah Winfrey endorsed Barack Obama for president during the Democratic primaries, a move that was heavily discussed in news coverage of the campaign. Research based on both observational (Garthwaite and Moore Reference Garthwaite and Moore2012) and experimental methods (Pease and Brewer Reference Pease and Brewer2008) suggests that Oprah’s endorsement boosted support for Obama. Celebrity endorsements have been found to affect political attitudes and behaviors outside high-stakes election campaigns as well.Footnote 7

Political advocacy has almost become the norm among US celebrities. Thrall and colleagues (2008: 366–67) studied 247 American celebrities and found that 62.8% spoke out about some publicly relevant issues, with each celebrity supporting an average of 1.8 causes. However, more than half the celebrities involved in some advocacy did not receive any news media coverage for these efforts, and only a select few achieved substantial media visibility. Hence, they argue that the broadcast-era model of “make noise-make news-make change,” by which celebrities could assume they could get visibility for any legitimate cause they endorsed, no longer applies in a saturated and fragmented media system. Instead, celebrity advocates increasingly target smaller niches of supporters directly via social media rather than relying on news coverage (364).

Concurrently, social media have become an important component of celebrities’ self-presentation and advocacy strategies. On these platforms, celebrities can reach large numbers of their fans continuously and without any journalistic mediation. Celebrities can also mobilize their supporters and share messages to their own followers. Moreover, directly communicating with followers on social media does not preclude seeking the press’s attention: journalists on the show business beat eagerly follow celebrities on social media, and political journalists also constantly patrol these platforms—Twitter in particular—for newsworthy material (Lasorsa, Lewis, and Holton Reference Lasorsa, Lewis and Holton2012; Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Molyneux, Coddington and Holton2014; McGregor and Molyneux Reference McGregor and Molyneux2018).

Most contemporary celebrities are skilled and successful social media users. According to market research, one-quarter of worldwide internet users aged 16–64 are strongly interested in celebrity news and gossip.Footnote 8 In particular, Twitter is very popular among celebrities’ fans as a way of staying in touch with their favorite stars: 25% of Twitter users claim to have tweeted at a celebrity and 24% to have retweeted them; among those users who are strongly interested in celebrities, the percentages are 34% and 31%, respectively. Many celebrities have become known in the business for their success in marshaling social media to enhance their brand and relationships with fans (e.g., Duffy and Hund Reference Duffy and Hund2015). In the business literature, celebrities are often touted as models for how to adapt to the social media age (e.g., Holt Reference Holt2016).

Although there is evidence that celebrities have adopted nuanced strategies to support their favored political causes, and that social media play an important part in promoting celebrities’ political engagement, we know little about how online followers respond to celebrities’ political ventures. Social media platforms are a very competitive environment, where new voices and messages constantly threaten to crowd out celebrities. Thus, the implicit deal between celebrities and users on social media is that the former provide entertaining material for free and the latter reciprocate with some measurable engagement. When substantial numbers of celebrities’ followers withhold their engagement, they are not keeping their end of this bargain.

The fact that engagement can easily be quantified with seemingly objective measures of likes, shares, comments, interactions, followers, views, and so forth creates challenges and opportunities for celebrities. These measures of popularity and engagement, Marshall argues (2014: xxiv), “are defining the new metrics of fame and, by implication, value and reputation.” Aggregated at a mass scale, users’ individual reactions to celebrities’ social media posts give fans some power over celebrities. If fans are unhappy, they can choose to be vocal about it, but they can also signal their dissent by staying silent, which in the currency of social media involves both not posting and not clicking. As the logic of engagement metrics on social media is fundamentally additive, silence or a lack of engagement by fans is, at the very least, a missed opportunity. To speak up and be ignored is to forgo a chance to generate user engagement; to be ignored by many fans over a long period of time may be a sign of decline in a celebrity’s popularity.

Whether they use social media or other means to convey their political views, celebrities need to weigh different priorities in deciding when, how, and on what issues to speak. On the one hand, they may want to use their public platforms to address causes they care about and may even gain popularity by taking stances on issues that resonate with the media and the public. On the other hand, as discussed earlier, promotional imperatives mean that celebrities need to appeal to broad audiences for commercial reasons, and addressing controversial political issues may alienate some of their supporters and customers of the companies that sponsor them. Many of the people who follow celebrities may not be particularly interested in politics, and although some may welcome a little political education from their favorite stars, others may not appreciate the diversion.

Moreover, some celebrities’ followers may be interested in politics and have strong preferences for parties, candidates, and policies that are at odds with those endorsed by the celebrity. Unless celebrities take positions that are widely shared among voters—an increasingly difficult task in a polarized political system—they risk alienating part of their audiences. This is the concern at the root of the supposed Michael Jordan quote with which we began this article. Therefore, we should expect celebrities to generally endorse political causes that are not very controversial in the electorate rather than venturing into polarizing issues—particularly into electoral politics, which is a zero-sum game that pits roughly half the voting population against roughly the other half.Footnote 9

The pitfalls of political advocacy around partisan issues are also clear to celebrities who communicate on social media. Marwick and boyd (Reference Marwick and boyd2011) found that Twitter users with large numbers of followers conceptualized their audiences as broad aggregates of individuals with disparate tastes that had to be navigated carefully. Celebrities are aware they need to balance the competing goals of appealing to different audiences—which includes trying to avoid alienating anyone—and of presenting themselves as authentic—which may involve taking contentious stances to appear outspoken and genuine (see also Marwick Reference Marwick2013).

Thus, celebrities can be expected to be reluctant to make inroads into partisan and electoral politics, especially during contentious and polarized times such as those the United States is currently experiencing (Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Layman, Carsey, and Horowitz Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowitz2006). Even Oprah Winfrey’s television show ratings and popularity declined after she endorsed Obama, fueling speculation that taking such a strong political stance may have alienated both Republicans and Hillary Clinton’s primary supporters.Footnote 10

One way to assess whether fans withhold their online engagement when celebrities tackle political controversies is to compare how followers react to political versus nonpolitical posts by celebrities. Our study focuses on Twitter, where a key metric to gauge user support and engagement is the Retweet (RT), which allows a user to post a message by another user in his or her own timeline. Although not all retweets are simple statements of support, they make it more likely that one’s followers will see the message being retweeted. Retweets amplify the visibility of both the celebrities and their messages, thus constituting a crucial currency in the attention economy on social media (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wells, Wang and Rohe2018).

To develop some theoretical expectations about fans’ aggregate behaviors, we need to conceptualize what kinds of users constitute the audience of a celebrity on Twitter. We argue that, for the purposes of our analysis, fans can be classified based on two sets of characteristics: their levels of interest in politics and their agreement with the celebrity’s position. Users with low levels of interest in politics may respond negatively to most political endorsements, because reading political commentary is not one of the key motivations why they follow a celebrity. Users with high levels of interest in politics, by contrast, may respond to the celebrity’s stance according to whether they agree with it. Users who, although interested, disagree with the celebrity should be less likely to express support and engagement than they would be to nonpolitical posts. By contrast, politically involved users who agree with the celebrity should be more likely to voice their support when the celebrity posts about politics than when she posts about other topics. Overall, then, we expect one group of followers to respond positively—interested users who agree—whereas the two remaining groups—interested users who disagree and politically uninterested users—should respond negatively, whether by openly criticizing the endorsement or, crucially for this study, by ignoring celebrities’ messages and withholding their online engagement with them.

Other dynamics and mechanisms, however, may lead to different outcomes. First, due to the fact most celebrities’ posts on social media do not refer to politics, the few that do may elicit higher levels of engagement because of their novelty.Footnote 11 Second, Twitter users who discuss political topics tend to post substantially more political messages than average users (Vaccari et al. Reference Vaccari, Valeriani, Barberá, Bonneau, Jost, Nagler and Tucker2015). Hence, fans who are politically inclined and support the celebrity’s endorsement may be disproportionately more vocal than others, more than making up, at the aggregate level, for the engagement that celebrities’ political tweets lose among the rest of their fans. To be sure, politically interested fans who oppose the celebrity’s stance may be equally vocal in their opposition and may do so by commenting on and replying to the celebrity’s endorsement post, rather than simply retweeting it without commentary and criticism.

To find out which of these different dynamics tends to prevail, we ask: do celebrities’ posts generate more retweets when they deal with electoral politics than when they deal with other topics? The baseline hypothesis, given that political content is not a key reason for following most celebrities, is that engagement with celebrities’ political tweets will be lower than with typical (nonpolitical) tweets (H1).Footnote 12

Once celebrities have decided to take a political stance, however, their expectations of how their social media followers are likely to react could inform their political strategy. More specifically, like other political actors, celebrities need to decide whether and to what extent they will act as cheerleaders for their favorite candidates or as critics of their opponents. Empirically, cheerleading celebrities would post a larger proportion of messages touting the positive qualities of the endorsed candidates compared with messages emphasizing the negative qualities of their opponents; for critical celebrities, the opposite would be true, with negative comments outweighing positive ones.

Although different celebrities’ inclinations, personal brands, and communication strategies may tilt their electoral tactics in favor of cheerleading or criticism, we argue that there are broader incentives to which, all else being equal, most celebrities should respond. We theorize that celebrities endorsing major party candidates on social media should be more likely to act as critics than as cheerleaders (H2). This proposition may be seen as contradicting the popular image of celebrities as “feel-good” personas, aiming to project positivity and good intentions. However, once celebrities have decided to venture into the zero-sum game of electoral politics in a polarized environment, there are three main reasons why they may be more inclined to engage in negative than positive campaigning.

First, research in political science and political psychology has shown that negative messages are more likely to be paid attention to, processed centrally, and subsequently remembered (see Lau et al. Reference Lau, Sigelman, Heldman and Babbitt1999 and Lau, Sigelman, and Rovener Reference Lau, Sigelman and Rovner2007 for systematic reviews). Relatedly, on social media negative political messages are generally more likely to elicit user engagement than positive ones. For instance, a study of users’ reactions to the Facebook posts of candidates in the US 2010 midterm elections found that messages attacking opponents yielded significantly more comments and likes (Xenos, Macafee, and Pole Reference Xenos, Macafee and Pole2017). Similarly, research on Facebook posts by members of Congress found that posts expressing disagreement with the other party garnered significantly more likes, comments, and shares, and this was especially true for posts expressing annoyance, resentment, or anger (Pew Research Center 2017). Thus, by acting as critics, celebrities should maximize online engagement.

Second, as discussed previously, celebrities need to carefully balance the ways in which they cater to different audiences. Some of their apolitical followers may be alienated by any diversion into politics. However, to the extent these fans tolerate any political messaging, they may be more receptive to negative than positive campaigning. Politically uninterested and unaffiliated voters tend to have low levels of trust in politicians writ large and may therefore be more open to messages that criticize them (Ansolabehere and Iyengar Reference Ansolabehere and Iyengar1997; Zaller Reference Zaller1992). When addressing apolitical supporters, then, celebrities may encounter less resistance if they act as critics than as cheerleaders.

Third, negative messages are more likely to attract news media coverage (Groeling Reference Groeling2010). Research shows that politicians who criticize others are more likely to be covered by the press, especially those who do not normally enjoy high levels of visibility (Haselmayer, Meyer, and Wagner Reference Haselmayer, Meyer and Wagner2019). To the extent that similar patterns apply to celebrities, they may be more likely to keep their name in the news—a crucial goal of their social media presence—by acting as critics than as cheerleaders.

In sum, celebrities should be expected to tailor their political ventures on social media toward the goal of maximizing user engagement (which, as explained, we measured as retweets on Twitter), and that, to the extent that negativity yields higher levels of engagement, celebrities should act more as critics than cheerleaders. However, the premise of our argument is that social media users react to negative campaigning by celebrities in a similar way to how they have been found to react to negative campaigning by politicians. This is an empirical question that has not been answered yet, and our research aims to fill this gap. To this end, we test the hypothesis that celebrities’ social media posts that criticize opponents should elicit a higher volume of retweets than social media posts that endorse their favored candidates (H3).

Data

To study how celebrities discussed politics on social media during and after the 2016 US presidential election and how their followers engaged with these messages, we first need to operationalize what constitutes a celebrity. We rely on widely adopted definitions of celebrity, discussed earlier, as someone who enjoys high public visibility across different media. If celebrities are “evaluated in terms of the scale and effectiveness of their media visibility” (Turner Reference Turner2014: 5), then the most accurate operational definition of celebrity must rely on the news media themselves. In other words, he, she, or they whom the media treat as a celebrity is, for all intents and purposes, a celebrity. Although this definition may be objectionable on some grounds—chiefly, that the news media may be biased in both their selection and presentation of different kinds of people as celebrities—it has the advantage of anchoring our study to a well-defined and replicable set of public documents—news reports by publications with mass diffusion—that are highly likely to affect, or at least reflect, widely shared characterizations of who is and who is not a celebrity. Other definitions focusing on particular traits exhibited by celebrities, such as charisma, star power, and stage presence (Turner Reference Turner2014), are much more difficult to reliably operationalize in a replicable manner, especially when collecting data on a large scale.Footnote 13 The constructivist approach we use is widely adopted in the literature on celebrities, which emphasizes that celebrity “is constituted discursively, by the way in which the individual is represented” (Turner, Bonner, and Marshall Reference Turner, Bonner and Marshall2000: 11). As the media are the main sources of these discourses and representations, we rely on them to identify who is a celebrity in the context of the contemporary United States.

More specifically, we identified 72 celebrities who either directly endorsed or implicitly supported Hillary Clinton before the 2016 election; 64 of those 72 Clinton-supporting celebrities are active on Twitter. The celebrities were identified through Boolean searches on Google identifying endorsements by people whom the media described as a celebrity when reporting the endorsement.Footnote 14 The list includes Lena Dunham, Oprah Winfrey, Katy Perry, LeBron James, and 60 other widely followed individuals from the entertainment industry (broadly understood).Footnote 15 Although Hillary Clinton attracted the most support from both the cultural and political establishment, we also identified 14 celebrities who endorsed Donald Trump in 2016, 12 of whom use Twitter. The personalities in this category include Jon Voight, Dennis Rodman, and, perhaps the most well-known at the time of this writing, Roseanne Barr. Finally, we included seven celebrities who endorsed Bernie Sanders and are active on Twitter, including Susan Sarandon, Spike Lee, and Mia Farrow.Footnote 16

We then used the Twitter Rest API to collect up to the 3,200 most recent tweets from each of the 83 celebrities we identified. The full corpus consists of more than 220,000 tweets (see table 1 for the summary statistics).Footnote 17 More than 4% of the tweets in the corpus—meaning the full dataset where every celebrity’s tweets and retweets are included—explicitly mention either Trump, Clinton, or Sanders by name. In the subset of the original tweets—that is, excluding all retweets— 2.8% of tweets in the sample mention either Trump, Clinton, or Sanders.Footnote 18

Table 1 Summary Statistics: Number of Tweets

The number of tweets that mention one of the candidates is surprisingly large (nearly 10,000 if retweets are included and 4,403 in the subsample of celebrity-authored tweets).Footnote 19 Hence, less than half of the tweets that mention one of the three presidential candidates were written by celebrities themselves. Often, these candidates’ mentions appear in the corpus because a celebrity retweeted some claim or article about Trump, Clinton, or Sanders. Writing political statements implicates a celebrity directly; as such, celebrities seem to be inclined more often to amplify political messages from other sources than to create original content about the candidates.

It is important to note that the tweets that explicitly mention a politician constitute a subset of the total number of celebrities’ tweets about politics. To be sure, celebrities sometimes express themselves about salient political issues without alluding to specific politicians. Furthermore, tweets about Trump, Clinton, or Sanders may be undercounted, given that statements such as “can you believe what he did?” or “I’m with her” need not include the name of the referenced politician to be understood, at least at the time in which they were posted. The total number of celebrities’ posts we considered as political should therefore be considered a lower bound on the extent to which they engage in political commentary. For our research purposes, we study specifically those messages that directly and clearly have a political meaning (insofar as they refer to a presidential candidate), rather than counting general expressions of opinions on the state of the country as well. Although the patterns described in this article suggest that many American celebrities are politically quite vocal (sometimes bordering on becoming activists), our analyses probably still understate the degree to which entertainers and other cultural elites are politically mobilized.

Further, the aggregate statistics show that it is not the case that celebrities make a single cautious endorsement during the campaign and then step aside. Figure 1 displays monthly counts of candidate mentions by each celebrity in the 12 months up to and including January 2017. The data show that some celebrities tweeted about presidential candidates multiple times per month. However, most tweeted just a few times per month. Figure 1 also reveals that celebrities became more politically vocal on Twitter as Election Day approached. Until the summer of 2016, Trump was mentioned by celebrities only in rare instances. Most celebrities avoided mentioning any candidate more than a handful of times, and only a very small number alluded on Twitter to any candidate for president more than 10 times per month. (Longer time horizons are displayed in figures 2 and A1.)

Figure 1 Monthly Mentions of Any Candidate by Each Celebrity, February 2016–January 2017

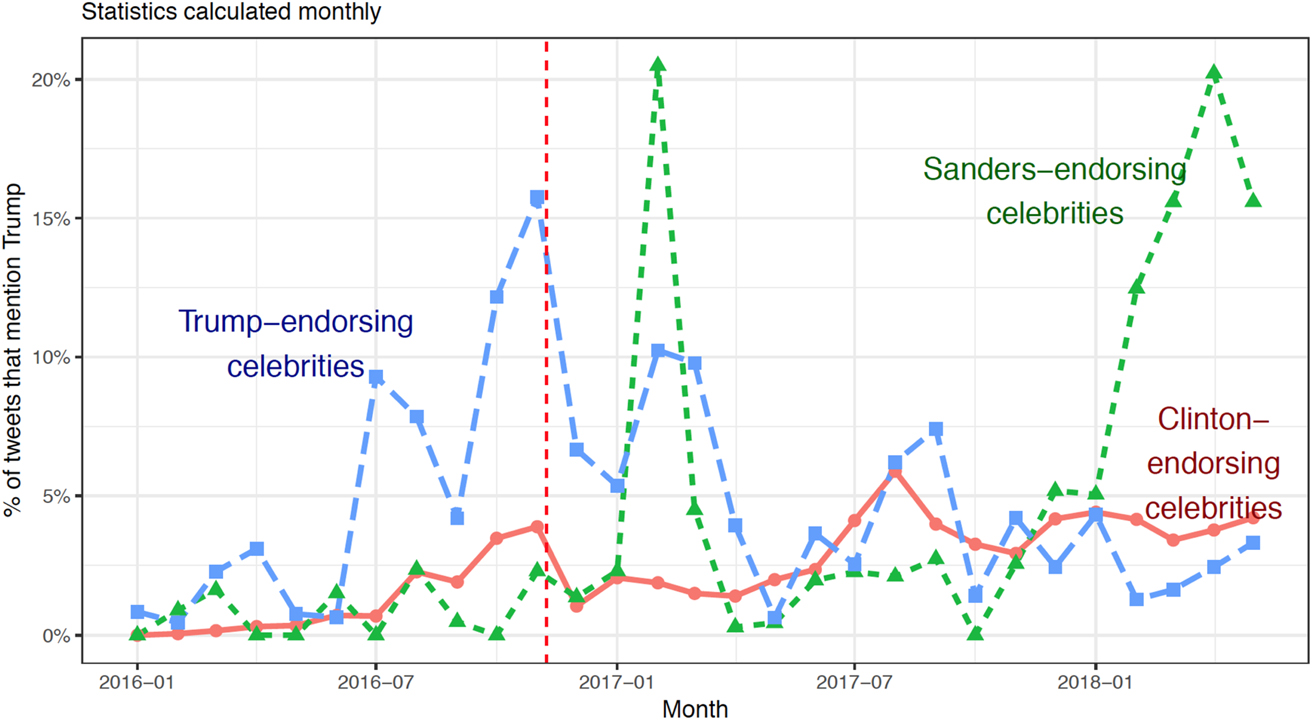

Figure 2 Proportions of Celebrity Tweets that Mentioned Trump, Broken down by Candidates Endorsed by Celebrities during the 2016 Election

Note: Dotted red line is the date of the 2016 US presidential election.

We assess the prevalence of supportive versus critical tweets by analyzing the frequency of the candidate-mentioning tweets, broken down by “celebrity type,” with the type referring to the candidate that a given celebrity supported in 2016. Thus the types included in our sample are Trump-supporting, Clinton-supporting, and Sanders-supporting celebrities. We conducted analyses on all celebrity types, but the data are particularly rich for Clinton-endorsing celebrities. Our sample is not politically balanced, but this composition reflects the true state of the world, in which many more celebrities endorsed Clinton than Sanders or Trump.

We analyze both the preelection campaign period and the first 16 months of the Trump presidency. Here, we note one data limitation: tweets by a handful of celebrities appear in our sample only since Trump’s election, due to the 3,200-tweet download limit maintained by Twitter.Footnote 20

Results

Do celebrities’ followers view political tweets as boring and possibly even annoying, and ignore them as a result? Our first hypothesis (H1) predicts that celebrities’ speech related to political figures should lead to lower levels of engagement by followers. Instead, we observe that tweets directly mentioning a political candidate are typically shared more widely than the remaining tweets. Among all tweets that mention one of the three candidates, the average number of retweets is 763. Tweets that mention no candidate are retweeted on average 733 times.

Celebrities’ tweets that mentioned Trump were re-shared most often (794 times on average), although there are differences across celebrity types. Specifically, celebrities who endorsed Clinton on average received 1,011 RTs when their tweet referred to Trump. In standardized terms—taking into account that different celebrities have varying potentials to amplify their messages because of inequality in their numbers of followers—celebrities who endorsed Clinton enjoyed on average an increase of nearly a half-standard deviation (0.42) in retweets when they tweeted about Trump (see table 2) as opposed to other subjects.

Table 2 Engagement (Celebrity-Standardized Retweets) as a Function of Tweet Content and Celebrity Type

Notes: Cell entries are OLS regression coefficients. Parentheses contain t-statistics. The significance threshold is * p < 0.01.

The Trump-endorsing celebrities in our dataset generally produced tweets that were not widely shared, mostly because they had fewer followers: the typical tweet among this group of celebrities that mentioned no candidate was retweeted only 63 times. Of 192 tweets from this group of Trump-endorsing celebrities that explicitly mentioned Clinton, 8 were retweeted at least 1,000 times. Focusing on these eight relatively popular tweets, we note that the number of RTs was unusually high for some but not all of their authors: Jon Voight’s tweet that mentioned Clinton (while criticizing Robert De Niro) received a level of RTs that was comparable to his other tweets. By contrast, other celebrities in this group (Scott Baio, Stacey Dash, Ted Nugent) saw their number of retweets increase by up to seven standard deviations when they mentioned Clinton.

Clearly, then, standardizing the number of retweets for each celebrity is important to get the full picture of the benefits (or possibly costs) that can materialize when celebrities tweet about political candidates. Therefore, in table 2, we examine the impact of political tweeting on standardized retweets that a celebrity received relative to that celebrity’s own other tweets.Footnote 21 In examining standardized retweets, we see that when Clinton supporters mentioned her, their statements on Twitter on average received 0.35 standard deviation more retweets relative to the average RTs of all their own tweets.

This popularity boost is comparable to the one received from tweeting about Trump. In fact, most celebrity types on average benefited when they tweeted about Trump. Even Clinton supporters—who did receive a boost from mentioning Clinton—received a larger boost from mentioning Trump (although the effects, .42 and .35, are fairly close in size and the difference between them is not statistically significant). Only Sanders supporters did not receive a conventionally statistically significant bump from mentioning Trump (although even here the predicted effect was positive and not too far from conventional measures of statistical significance).

Given that we observe no statistically significant negative effect across any of our types for mentioning any of the politicians—indeed, table 2 does not even feature a single negative coefficient, let alone a statistically significant one—it seems safe to conclude that the empirical evidence falsifies H1. Overall, then, celebrities who tweet about politicians bear no clear engagement cost, at least not as a general rule in terms of retweets. Thus it may be safer for celebrities to tweet about politics than some earlier research and popular wisdom have suggested.Footnote 22 Large numbers of followers do engage with political content, suggesting that they find it interesting enough to share.

To be sure, tweets that mention no candidate are occasionally political. As discussed earlier, this means that table 2 accounts for only the most explicitly political content. To briefly give readers a sense of some other themes that appeared in the widely circulated tweets. some of the 28 viral celebrity tweets (retweeted more than 100,000 times) do contain messages that should be viewed as political expression. One tweet from Ellen DeGeneres argues, “Banning transgender people [from serving in the military] is hurtful, baseless and wrong.” Another tweet (from singer and actor John Legend) states, “Impeach the white supremacist in the White House.” Or the tweet containing “#FreeMeek”Footnote 23 (from LeBron James) can certainly be viewed as a statement pointing to racial inequalities or perhaps even as a call for criminal justice reform. Still, the typical highly retweeted message is not political. Among the most popular tweets are LeBron James’s message, “Love me or Hate me but at the end of the day u will RESPECT me!!” and Leonardo Di Caprio’s expression of appreciation to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for his Oscar award. However, DiCaprio did make a political statement in his Oscar acceptance speech, saying, “We need to work collectively together and stop procrastinating” in fighting climate change. Showing that celebrities can influence behavior on social media regardless of what platform they use, Leas and colleagues (Reference Leas, Althouse, Dredze, Obradovich, Fowler and Noar2016) document that the number of tweets containing the terms “climate change” and “global warming” increased 636% immediately after Di Caprio’s speech.

With the evidence clearly showing that celebrities do not pay a price in terms of engagement for tweeting about presidential candidates—thus falsifying H1—we can now turn to the question of how they tweet about those candidates. H2 predicts that celebrities will act more often as critics than as cheerleaders of politicians. We test this proposition by comparing how often celebrities mention their endorsed candidate versus an opponent. Table 3 shows that when celebrities who endorsed Clinton or Sanders mention a politician, they mention Trump more often than the candidate whom they favored in 2016. Many of these tweets are sharply critical of the president (though some “merely” mock him). That said, the data only partially support the second hypothesis, because cheerleading for their candidate was a frequent tactic among those celebrities who endorsed Trump. The evidence suggests that celebrities are often on the attack, but there is heterogeneity across types. Sanders-endorsing and Clinton-endorsing celebrities devoted most of their tweets to the candidate of whom they disapproved, whereas Trump-endorsing celebrities mostly tweeted about the candidate they supported.

Table 3 Tweet Frequency Percentages for the Entire Corpus

Of course, after the presidential election Clinton and Sanders waned, while Trump, as the new president, became more topical than ever, so table 3 is not a complete assessment of the hypothesis. We present additional evidence in table 4 and figure 2 by assessing the data separately for 2016 and the period of time after Trump was inaugurated.

Table 4 Percentage of Tweets that Mention a Specific Candidate

When we limit the analysis only to the tweets that were written in 2016, we observe that celebrities actually devoted a slightly greater amount of time to cheerleading by mentioning the candidate they endorsed. They posted slightly fewer tweets attacking opponents, at least on average (table 4, panel A).

It was not until after the election that most Sanders and Clinton supporters took on the role of critics. The candidate they had supported was largely “forgotten” – at least on Twitter -- once Donald Trump took office (table 4, panel b). Celebrities supporting Trump, in contrast, generally continued to speak about the candidate they endorsed.

Similarly, figure 2 confirms that commentary about Trump from celebrities certainly did not cease after the election, but suggests a change in who, among celebrities, spoke the most about him.Footnote 24 Before the election, Trump supporters engaged in a fair amount of cheerleading and were the most likely to mention the candidate. Eventually, the Clinton-supporting celebrities became more likely to mention the president on Twitter than Trump supporters. Although this reversal did not take place immediately after the election, in the latest months for which we have data, celebrities who opposed Trump as candidate were more likely to mention him on Twitter than celebrities who supported his presidential bid.

Another noteworthy pattern visible in figure 2 is that there were three months after the election in our dataset when Sanders-endorsing celebrities mentioned Trump in at least 15% of their tweets. Although Sanders endorsers are a much smaller group of celebrities than Clinton endorsers, this further confirms that they do not seem to fear substantial backlash from continuing to discuss politics after the election. Combined with the continuing nontrivial number of tweets about Trump from Clinton-endorsing celebrities, it is clear that Democratic-leaning celebrities did not retreat from political combat on Twitter well into the Trump presidency. Whether this would still be the case if Trump were more popular remains an open question.Footnote 25

This finding directly addresses our third hypothesis: Is tweeting about a political opponent a strategy that leads to good outcomes from the perspective of a celebrity (assuming such celebrity values retweets), as H3 predicted? As table 2 shows, Clinton supporters—who, it is worth recalling, are the vast majority of the celebrities in our dataset—did indeed get higher numbers of retweets when tweeting about Trump than when tweeting about Clinton. Trump supporters, in contrast, received more engagement when tweeting about Trump. These findings thus provide mixed evidence in support of H3, but also suggest there could simply be a Trump effect, whereby tweets about the celebrity-in-chief are just generally more likely to generate engagement than tweets about other politicians.

Taken together, however, given the preponderance of Clinton endorsers in our dataset, the evidence leans toward supporting H3, showing that there may be an advantage to playing the attack dog role once celebrities have made a decision to enter the political fray. But without this same advantage accruing to Trump and Sanders supporters, it is difficult to claim overwhelming support for H3. Moreover, the very fact that there may be a Trump effect at work (which would explain the results for both Trump and Clinton celebrity supporters, if not the few Sanders supporters in the dataset) makes it that much more difficult to conclusively claim support for H3 from the data at hand.

Before we suggest some conclusions, there are a few significant limitations to our analysis that are important to consider. Like many other studies of social media, we rely on Twitter data and thus miss a potentially richer source of data on Facebook because of issues surrounding data access (Tucker et al. Reference Tucker, Guess, Barbera, Vaccari, Siegel, Sanovich, Stukal and Nyhan2018). Twitter itself is not a perfect source of data, as the limit of 3,200 tweets that can be collected per account meant that we could not capture all the tweets posted by all the celebrities for the whole period of analysis. More generally, we capture only the interactions that celebrities have with their followers on a single social media platform—although, as we document, Twitter is an extremely important arena for celebrities— and thus our study cannot pick up celebrities’ behaviors that vary across platforms. Our research design, which involves identifying celebrities who supported presidential candidates via news reports of this support, does not permit us to analyze the behavior of celebrities who may have privately supported a candidate, but did not receive public recognition of this support.Footnote 26 In addition, celebrities occasionally delete posts on social media, so we may not be working with a complete corpus comprising all tweets. That being said, there are potentially greater costs for celebrities associated with deleting tweets than for average citizens, as the very act of deleting a tweet can itself become news, so we are less concerned about this possibility than we might be in other cases.Footnote 27

Finally, an important contextual element is that the 2016 presidential campaign saw voters develop historically negative evaluations of both candidates. For instance, according to Gallup, at the end of the campaign 52% of voters had an unfavorable view of Clinton and 62% of Trump: in both cases, these were the highest unfavorability percentages among all presidential candidates tracked by Gallup since 1956.Footnote 28 Perhaps reflecting and possibly exacerbating these trends, the campaign was likewise highly negative on social media (Gross and Johnson Reference Gross and Johnson2016), and the tone of newspaper and television news coverage was also markedly critical of both candidates (Patterson Reference Patterson2016; Watts and Rothschild Reference Watts and Rothschild2017). To the extent that celebrities were aware of the state of public opinion and the overall climate the media had created around the campaign, they may have slightly shifted their messaging strategy. First, celebrities may have been aware that praising their favorite candidate was not the most effective tactic to advance their cause, as most voters did not share those feelings. Second, and perhaps more selfishly, celebrities may have reasoned that behaving as critics would have kept them on the right side of public opinion, as majorities of voters disliked both candidates. Criticizing disliked candidates may thus have been a tactical move to limit the potential damage that taking a more positive stance in favor of an unpopular candidate may have caused. Research comparing different political systems or different elections at different points in time would be needed to disentangle the role of general incentives, such as those outlined by our theory, and context-specific incentives, such as the ones highlighted here. Our best guess is that the widespread antipathy toward both candidates that characterized the 2016 elections might bias us toward finding support for H2 and H3 that might not be present in other years.

We also recognize that 2016 might have been viewed as a critical election by those left-leaning celebrities who were alarmed by Donald Trump’s success in the GOP primaries. If less polarizing nominees emerge in the future, celebrities could respond by reducing the volume of their political tweets, so we cannot say whether the patterns we observe are generalizable over time. That said, there is no reason to expect that cultural elites will stay on the sidelines during the 2020 election campaign.

Conclusion

Contemporary election campaigns and the permanent campaigning that follows them are increasingly heterogeneous assemblages of different types of political, media, and social actors, each playing different but potentially overlapping roles in striving to shape media narratives and voters’ preferences. Social media, and Twitter in particular, are interesting environments where these interactions can be observed in public and in real time. In this article, we have shed light on the role celebrities play in political discourse and on the levels of engagement that different types of political posts by celebrities elicit among their followers.

Our first contribution is that, contrary to conventional wisdom, we find that celebrities on Twitter do not pay a price, at least in terms of users’ engagement via retweets, for venturing into the electoral arena. Celebrities obtain on average a higher number of retweets when they tweet about high-profile politicians than when they do not. This finding has at least two important implications. First, celebrities may be able to be effective political messengers, at least when it comes to high-stakes presidential campaigns and their aftermath. Not only can they directly reach large numbers of followers—often larger, and, in all likelihood, less politically involved and thus potentially more open to influence than the politicians they support—but they can also enroll these followers to relay their messages to other users who are thus indirectly reached by celebrities’ political statements. This two-step flow of communication suggests that celebrities’ social media profiles may play a similar role to other forms of mediated political entertainment in reaching the types of voters who might not otherwise pay much attention to politics and public affairs. The second implication is that, to the extent that celebrities and their social media managers track the engagement metrics of their social media profiles, they may be further encouraged to speak up about politics. Whereas Michael Jordan was reportedly worried that he would pay a commercial price if he got involved in politics, contemporary celebrities on Twitter seem to be faced with a starkly different set of incentives—of which perhaps Taylor Swift was aware—and one that may be conducive to increased, albeit occasional, political activism. We note that our conclusion here is based on observational data, and it may be that the celebrities we analyze here have histories of tweeting about politics in a way that has left them with only sympathetic supporters. But given the nature of the 2016 election, we believe that the political tweets of many of these celebrities conveyed new information to their followers.

Our second contribution has been to provide a theoretically informed framework to assess how celebrities speak up about politics on social media. We conceptualized two different roles celebrities can play in the political arena—as cheerleaders and as critics—and offered a set of theoretical expectations for why they should perform each of these roles. Our findings indicate that celebrities take up these roles differently in different political contexts. During campaigns, they mostly perform as cheerleaders for their favorite candidate, although they do not shy away from criticizing opponents. Outside of campaigns, they overwhelmingly focus on the president and neglect his or her past electoral contenders. Celebrities’ social media followers responded positively to these strategies. Twitter users did not withdraw their engagement—the key currency on social media—from celebrities who acted as political attack dogs, and in some cases they actually rewarded them for doing so.

Our third contribution has been to reveal some interesting differences between the celebrities who endorsed different candidates in the 2016 US presidential election. Celebrities generally elicited higher levels of users’ engagement when they discussed politics. Trump-supporting and Sanders-supporting celebrities, however, were more vocal in terms of explicitly political tweets posted as a fraction of all their tweets than were Clinton supporters. Moreover, Trump-supporting celebrities were more likely to act as cheerleaders than were Clinton-supporting celebrities. Interestingly, Trump-supporting celebrities got the biggest boost in engagement when mentioning their own candidate, whereas Clinton-supporting celebrities—again, the vast majority of celebrities in our dataset—enjoyed a smaller increase from tweets mentioning Clinton (as opposed to Trump) and, if anything, got a slightly bigger boost from mentioning Trump.

Remarkably, we did not find strong support for any of our hypotheses that we drew from the literature: celebrities did not receive lower engagement for political posts; they did not primarily focus on attacking opponents; and there is no clear evidence that attacking opponents was rewarded with more retweets than supporting one’s preferred candidates. Perhaps the reason this is the case is because there is something fundamentally different about social media as opposed to other forms of communication, suggesting that there may be a need for new theorizing of celebrities’ (and their followers’) political behavior in the digital age. Alternatively, these patterns may suggest that the competitive context of an election and its aftermath needs to be taken into account when theorizing and modeling celebrities’ political behavior. The selection of an entertainment star with a substantial Twitter following as the Republican presidential nominee and his subsequent election as president clearly must be considered in interpreting our findings. Trump’s historically low popularity coupled with a high intensity of support among his base should also be borne in mind. We hope future research can build on the framework we proposed and tested in this article to compare different elections and different candidates, thereby testing theories of how candidate characteristics and electoral context contribute to shaping the ways in which celebrities become politically mobilized, how they choose to do so, and how audiences respond to these messages.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719002603