Introduction

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is characterized by an excessive preoccupation with a perceived flaw in one or several areas of one's physical appearance that causes significant distress and/or functional impairment. BDD is common and affects between 1.7% and 4.9% of the general population (Rief et al. Reference Rief, Buhlmann, Wilhelm, Borkenhagen and Brähler2006; Boroughs et al. Reference Boroughs, Krawczyk and Thompson2010), with the onset typically occurring in adolescence (Gunstad & Phillips, Reference Gunstad and Phillips2003). Comorbid mental health problems seem to be the norm rather than the exception with major depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) or social phobia being the most common additional difficulties (Gunstad & Phillips, Reference Gunstad and Phillips2003).

Cognitive models and processes

Cognitive behavioural models of BDD (e.g. Veale, Reference Veale2004; Neziroglu et al. Reference Neziroglu, Khemlani-Patel and Veale2008) highlight key processes that are understood to maintain body image concerns. These include safety-seeking behaviour (e.g. grooming and camouflaging rituals), self-focused attention, repetitive behaviours (e.g. mirror checking, reassurance seeking), attempts to correct one's appearance (e.g. through plastic surgery) and avoidance (e.g. of social situations), which may all reduce distress in the short-term but ultimately prevent disconfirmation of feared outcomes thus maintaining unhelpful appearance-related beliefs and preoccupation with perceived flaws. For example, someone who believes themself to be unacceptable because of perceived flaws in their skin might attempt to minimize a perceived threat of being bullied for bad skin by engaging in elaborate skin care routines before leaving the house. The absence of any comments is then attributed precisely to those safety-seeking behaviours (rather than to the fact that the risk was overestimated) thus perpetuating the BDD belief system.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) aims to help clients develop a more helpful understanding of their difficulties through targeting and reversing these maintaining factors. Various case series and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have found CBT to be superior to waitlists (Rosen et al. Reference Rosen, Reiter and Orosan1995; Veale et al. Reference Veale, Boocock, Gournay, Dryden, Shah, Willson and Walburn1996) and more recently superior to anxiety management (Veale et al. Reference Veale, Anson, Miles, Pieta, Costa and Ellison2014a ). A different RCT by Wilhelm et al. (Reference Wilhelm, Phillips, Didie, Buhlmann, Greenberg, Fama, Keshaviah and Steketee2014) also found manualized CBT for BDD effective compared to waitlist controls. The authors added modules utilizing basic CBT for BDD [e.g. exposure and response prevention (ERP), cognitive restructuring, or perceptual retraining] and also optional treatment modules selected for particular symptoms such as compulsive skin picking, cosmetic treatment, or concerns about muscularity.

CBT is the treatment of choice. Outcome studies have consistently shown average symptom reduction between 32% (Wilhelm et al. Reference Wilhelm, Otto, Lohr and Deckersbach1999) and 53% (Neziroglu et al. Reference Neziroglu, McKay, Todaro and Yaryura-Tobias1996); these drops are related to individual CBT (Veale et al. Reference Veale, Boocock, Gournay, Dryden, Shah, Willson and Walburn1996) or group CBT (Rosen et al. Reference Rosen, Reiter and Orosan1995). Early studies have primarily focused on behavioural interventions such as ERP (e.g. McKay et al. Reference McKay, Todaro, Neziroglu, Campisi, Moritz and Yaryura-Tobias1997) to pure cognitive interventions (e.g. Geremia & Neziroglu, Reference Geremia and Neziroglu2001); and most protocols draw on both ERP and cognitive techniques (Rosen et al. Reference Rosen, Reiter and Orosan1995; Neziroglu et al. Reference Neziroglu, McKay, Todaro and Yaryura-Tobias1996; Wilhelm et al. Reference Wilhelm, Otto, Lohr and Deckersbach1999). Wilhelm et al.’s recent RCT found that 81% of all participants who received CBT for BDD showed symptom reduction of ≥30% at post-treatment. NICE guidelines therefore recommend CBT, including ERP using a need-based stepped-care approach, with the intensity of care depending on the severity of the presentation. However, current treatment protocols for BDD may be less effective in addressing non-anxiety emotions such as shame, disgust, and anger; and therefore recent studies have sought to enhance CBT with emotion processing interventions, in particular with imagery rescripting of past relevant events (Ritter & Stangier, Reference Ritter and Stangier2016; Willson et al. Reference Willson, Veale and Freeston2016). While anger is common in trauma-exposed individuals (Whiting & Bryant, Reference Whiting and Bryant2007) including BDD it is often not sufficiently recognized in treatment (Cassiello-Robbins & Barlow, Reference Cassiello-Robbins and Barlow2016). Both shame and anger can be destructive to those with BDD and if not targeted successfully may keep the person stuck and potentially lead to dropout. Shame in particular promotes withdrawal from others and leads people to hide; these behavioural responses to shame may be closely linked with depression, housebound rates, or suicide risk – all harmful outcomes that may be elevated in those with BDD (e.g. Weingarden & Renshaw, Reference Weingarden and Renshaw2015).

Functional and contextual approach

Recent advances in conceptualizing BDD have emphasized functional and contextual aspects in the development and maintenance of BDD (Veale & Gilbert, Reference Veale and Gilbert2014). Taking an evolutionary angle Veale & Gilbert (Reference Veale and Gilbert2014) hypothesize that people with BDD are particularly sensitive to monitoring aesthetics. Physical appearance is one of the most common dimensions for shame (Gilbert & Miles, Reference Gilbert and Miles2002) and those with BDD have often experienced social threats in the form of shame, humiliation and rejection (Veale, Reference Veale2004; Neziroglu et al. Reference Neziroglu, Khemlani-Patel and Veale2008). Furthermore, sexual and physical abuse in childhood and adolescence are common in individuals with BDD who in turn are at risk of developing intense disgust and shame about the trauma and their bodies (Didie et al. Reference Didie, Tortolani, Pope, Menard, Fay and Phillips2006; Neziroglu et al. Reference Neziroglu, Khemlani-Patel and Yaryura-Tobias2006; Buhlmann et al. Reference Buhlmann, Marques and Wilhelm2012). These experiences and their interpretation may also lead to hypersensitive monitoring of physical appearance and also reinforce overvaluation of appearance. Osman and colleagues (Reference Osman, Cooper, Hackmann and Veale2004) describe the experience of BDD as a distorted image or ‘felt impression’ of their appearance, often visually perceived from the observer perspective; and these are commonly emotionally linked with past experiences, accompanied by a current sense of threat due to lack of processing. In fact Osman et al. (Reference Osman, Cooper, Hackmann and Veale2004) found that people with BDD experience intrusive negative appearance-related images associated with early aversive memories (e.g. being bullied). People with BDD respond to threat either by threat monitoring such as mirror checks or comparing themselves with others or avoidance and safety-seeking behaviours. These behaviours all increase self-focused attention and monitoring of how they think they look on the basis of their ‘felt impression’.

Aim of the study

In this paper we describe the case of a 25-year-old man with severe BDD following experiences of sexual abuse and bullying. The service user whose case we describe here, is referred to as Michael, and has consented to publication of his case. To ensure his anonymity, we have also altered minor details of his background and context of his story, without changing the meaning or complexity of his difficulties. Michael met criteria for severe and treatment-refractory BDD and was seen in a UK national residential specialist clinic for obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. The term ‘treatment-refractory’ (or treatment-resistant) is used in UK mental health and applied to those BDD patients who meet the following criteria: a Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale modified for BDD (BDD-YBOCS) score of ≥36 (out of 48); two previous unsuccessful courses of CBT (including ERP) and at least two adequate trials of a serotonin reuptake inhibitor for a minimum of 3 months. Patients who meet these criteria qualify for NHS national funding of treatment in so-called highly specialized services which are staffed by multidisciplinary teams of healthcare professionals with expertise in the management of BDD (for a description of highly specialized services for OCD and BDD in the UK, see Drummond et al. Reference Drummond, Fineberg, Heyman, Kolb, Pillay, Rani, Salkovskis and Veale2008). Michael also suffered from low mood, which was secondary to his BDD, and he had felt so hopeless that he had previously attempted ending his life by overdosing (aged 16 and 21), although on admission he denied any suicidal plans. At the time of admission Michael was under the care of his local community mental health service. He had met his care coordinator fortnightly and had been regularly reviewed by his local psychiatrist. Three past CBT outpatient courses had a pure behavioural focus and were of limited success. Below we describe Michael's case, his treatment and some implications for working with complex BDD. We hypothesize that past treatment failure was due to not processing the emotions of shame and anger related to Michael's early experiences that were the emotional origins of his BDD.

Method

Presenting difficulties and background information

Michael is a man in his mid-twenties who suffered from severe and treatment-refractory BDD. His BDD was characterized by an excessive preoccupation with facial skin, in particular with spots, blemishes and blackheads, which he believed would make him look ‘ugly’ and unacceptable. He was also preoccupied with the belief that he had dark rings under his eyes. Michael suffered from low self-esteem and social anxiety. Michael lived with his mother; his parents were separated and he had no contact with his biological father. His elder brother (by 2 years) was married with two small children and lived close by. Michael was unemployed and was receiving disability allowance. Football was his passion but he had been unable to play for many years because of the severity of his BDD.

Coping behaviours and formulation

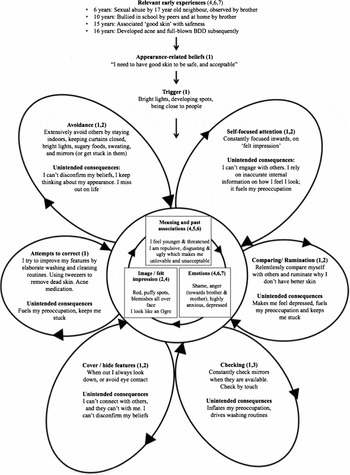

Michael's formulation is displayed in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Michael's formulation of the onset and maintenance of his body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) including the unintended consequences of each BDD behaviour. Numbers in parentheses denote the therapeutic intervention targeting the relevant BDD behaviour, process and/or experience: 1, Behavioural experiments; 2, Attentional training; 3, Mirror retraining; 4, Imagery rescripting; 5, Stimulus discrimination; 6, Compassion-focused therapy; 7, Family work.

His preoccupation was easily triggered in social contexts, particularly when sitting close to someone else, seeing others whom he perceived to have ‘better skin’, or catching a glimpse of his appearance in the mirror or other reflective surfaces. When Michael's BDD was triggered he experienced a felt impression of having large, puffy spots all over his face from an observer perspective of how he thought he looked to others. He said he felt he looked like an ‘ogre’, a monster-like fantasy figure. To him, his appearance meant that he was an ugly, repulsive and disgusting person that no one would want to know. His self-portrait as displayed in Figure 2 captures a sense of how he felt his face looked at the beginning of treatment. To cope with his appearance distress Michael engaged in extensive avoidance and a number of safety-seeking behaviours.

Fig. 2. Self-portrait that Michael drew of his perceived flaws in his facial skin at the beginning and at the end of treatment.

He either attempted to avoid mirrors or got stuck looking in them for long periods trying to ‘seek satisfaction’ with his appearance. Unsurprisingly, it was virtually impossible for Michael to find any satisfaction when examining his facial skin in the mirror, which almost always increased his self-focused attention thus exacerbating his preoccupation with perceived flaws. At the beginning of treatment he was using elaborate washing and creaming routines to reduce the likelihood of developing spots. This involved expensive creams and strong anti-acne medication (Roaccutane). Michael also avoided sugary foods and drinks because he feared this would make skin outbreaks more likely. He also avoided any form of physical exertion or exercise to prevent himself from sweating which he thought would increase the likelihood of developing spots. He also avoided bright lights at all costs and mostly stayed indoors with the curtains shut. He would shower in the dark to minimize the chance of seeing himself in reflective surfaces. His mother had taken down all the mirrors in the house (except in the bathroom) and had hidden all hand mirrors. Michael's days were unstructured, and he spent most days sitting in the dark in his room ruminating about why he did not have better skin. He also relentlessly compared himself to other people and those in magazines or on the TV ‘losing 9 out of 10 times’. On various occasions he attempted to scrape off his facial skin using sand paper, and several times came close to burning off his skin believing that scraped or burnt skin would still be better than having spots. On the rare occasion when he left the house Michael would walk fast, always keeping his head down, and avoided eye contact to keep safe from the scrutiny of others.

Developmental formulation

The onset of Michael's BDD was in his adolescence, and in the following section we describe the relevant early experiences that appeared to be at the root of his BDD. At the age of 6 he was sexually abused by his 17-year-old neighbour who coerced Michael twice into having oral sex with him in the space of a few weeks. The second time this happened in the fields near his house, and was secretly observed by his brother. A couple of years after this incident his brother started telling Michael's peers in school what he had witnessed, and subsequently Michael was bullied and shamed in school. His bullies would call him names; spray derogatory terms on house facades near his home, mock him in public by pretending to give oral sex, and exclude him from activities. At home his brother constantly shamed Michael by reminding him of the abuse, calling him ‘gay’, ‘weird’ or weak. Michael was so ashamed of this experience and his brother's bullying that he felt unable to tell his mother; although in treatment Michael told his therapist that his mother should have been aware and he recalled a number of occasions when his brother openly bullied him and Michael had felt unsupported and unprotected by his mother. Michael constantly felt under threat of being ashamed and humiliated (either by his brother or by bullies at school) and his safest way of coping was to remain silent when attacked and/or to ‘run away’. The bullying continued for several years, which understandably affected Michael's self-esteem, and because he was too ashamed and also too afraid of any consequences he did not speak out or express his anger towards his bullies, or to his mother. Michael avoided social situations and conflict, and coped by ‘keeping quiet’ and ‘taking the bullying’. He gradually became more and more reclusive and mainly stayed indoors. His appearance concerns developed when, aged 15, he became preoccupied with his skin. He associated ‘good skin’ with feelings of safeness. He watched a lot of TV at the time, was reading youth magazines and noticed that famous people always seemed to have perfect ‘Hollywood skin’. While he felt that he had no control over his environment, and in particular about people shaming him, he felt he could control what his skin looked like. He became more and more emotionally invested in having good skin, and felt more confident in his social skills when he perceived his skin to be clear. He developed a set of appearance-related beliefs such as ‘if you have good skin, you are untouchable’ and ‘No matter what people do to you, at least you have good skin’. He believed that skin was everything and developed the conditional assumptions that ‘If you have good skin, you are god. If you have bad skin, you are a piece of rubbish’. Michael exclusively applied this belief to himself because he felt that others had more to offer than just good skin, whereas the only acceptable thing that he felt he could offer to others was to have good skin, he also believed that only having good skin would stop others from ‘taking the mickey’.

Controlling his skin gave him some sense of protection, and this fragile shield crumbled when he started developing some spots in puberty. At the age of 16 he felt he lost his only protection and subsequently developed full-blown BDD. Throughout puberty he met with his dermatologist numerous times who prescribed strong anti-acne medication which did not alleviate his BDD symptoms. His preoccupation with good facial skin seemed predominantly associated with shame, and was therefore particularly heightened when these old feelings of shame, threat, rejection, inferiority or humiliation were triggered. Because these emotional memories remained unprocessed they continued to fuel his felt impression thus maintaining a sense of current threat.

Measures

BDD-YBOCS

The BDD-YBOCS is a clinician-rated 12-item scale (Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Hollander, Rasmussen, Aronowitz, DeCaria and Goodman1997) which assesses the severity of BDD symptoms over the past week. All items range from 0–4, and cover preoccupation, behaviours, insight and avoidance; scores range from 0 to 48. Greater scores indicate more severe symptomatology. The BDD-YBOCS was carried out at pre-, mid-, post, and 6-month follow-ups by the primary author (O.S.). Psychometric properties are good. Cronbach's α for the scale is 0.92. Response to treatment is defined as a ≥30% decrease in the total BDD-YBOCS score (Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Hart and Menard2014).

Appearance Anxiety Inventory (AAI; Veale et al. Reference Veale, Eshkevari, Kanakam, Ellison, Costa and Werner2014b)

The AAI is a 10-item self-report questionnaire for measuring frequency of avoidance behaviour and threat-monitoring (e.g. self-focused attention or mirror checking) that are characteristic of a response to a distorted body image; each item is scored from 0 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘all the time’), and the range of the total scores is 0–40, with higher scores reflecting a greater frequency of the responses. Psychometrics are good with a Cronbach's α of 0.86.

The Body Dysmorphic Disorder Dimensional Scale (BDD-D; LeBeau et al. Reference LeBeau, Mischel, Simpson, Mataix-Cols, Phillips, Stein and Craske2013)

The BDD-D is a 5-item self-report measure to assess BDD severity, with the total score ranging from 0 to 20. The scale has been modeled on the Florida Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (Storch et al. Reference Storch, Bagner, Merlo, Shapira, Geffken, Murphy and Goodman2007), and has shown good psychometric properties in a non-clinical sample (LeBeau et al. Reference LeBeau, Mischel, Simpson, Mataix-Cols, Phillips, Stein and Craske2013) but has not yet been validated in clinical samples of individuals with BDD.

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke & Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002)

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report measure of depression with items ranging from 0 (‘not at all’) to 3 (‘nearly every day’), with a maximum score of 27. Higher scores reflect a greater symptomatology of depression; Cronbach's α for the scale is 0.89.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7; Spitzer et al. Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006)

The GAD-7 is a 7-item self-report measure for symptoms of generalized anxiety; each item is scored from 0 to 3, thus the total score ranges from 0 to 21, with higher scores reflecting a greater symptomatology; Cronbach's α for the measure is 0.92.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID, First et al. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1997)

The SCID is a semi-structured clinician-administered interview guide for the assessment of emotional disorders according to DSM-IV. The SCID has been shown to have moderate to excellent psychometric properties (Lobbestael et al. Reference Lobbestael, Leurgans and Arntz2011).

Reliable Change Indicator (Morley & Dowzer, Reference Morley and Dowzer2014)

The Leeds Reliable Change Indicator is a statistical method to determine whether change on our outcome scores is reliable and clinically significant. We used a user-friendly Excel spreadsheet that is freely available from the University of Leeds (http://medhealth.leeds.ac.uk/info/2692/research/1826/research/2). We obtained clinical population means and standard deviations for the BDD-YBOCS, AAI, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 from Veale's recent RCT on BDD (Veale et al. Reference Veale, Anson, Miles, Pieta, Costa and Ellison2014a ); and relevant psychometric properties for the BDD-D from LeBeau et al.’s study (Reference LeBeau, Mischel, Simpson, Mataix-Cols, Phillips, Stein and Craske2013).

Treatment

Michael's psychological treatment was multi-faceted and focused on helping him (a) to build a more helpful perspective of his difficulties, (b) to develop a more functional and healthy relationship with reflective surfaces, (c) to develop, consolidate and build his self-soothing, self-compassion and mindfulness skills, (d) to plan and move towards activities in line with his valued life goals, (e) to resolve his feelings of anger towards his brother and the bullies of his childhood, and (f) to reduce the sense of shame associated with past sexual abuse.

Treatment broadly fell into the following three stages

Stage 1. Engagement; socialization into treatment model; shared understanding of development of BDD and alternative view on problem; behavioural experiments to test out alternative view.

Stage 2. Imagery rescripting of relevant past shame-based experiences, alongside continuous behavioural interventions.

Stage 3. Family sessions with mother and brother to work through feelings of anger towards them, alongside continuous behavioural interventions.

Michael was treated by an experienced therapist (O.S.) who received expert supervision by the second author (J.W.) and fortnightly discussed treatment with the multidisciplinary team at ward round. Treatment aimed to help Michael to build an alternative more benign view on his difficulties using a cognitive model of BDD (Veale, Reference Veale2004). An overview of how the different treatment components map onto Michael's formulation is presented in Figure 1. The first 6 weeks focused on engaging and socializing Michael into the model. All therapeutic exercises and discussions aimed to test out two different theories of his difficulties.

Theory A (appearance problem): ‘My problem is that my facial skin is terrible and makes me look ugly. Therefore, no one wants to know me. Also, others have better skin than me and therefore are better humans than me (higher status, relationships)’.

Theory B (preoccupation problem): ‘My problem is that I am preoccupied with my facial skin and that I worry others would see me as ugly and therefore don't want to know me. I also worry that others are somehow better than me’.

When coming to the residential unit Michael had been treating his difficulties as one of flawed appearance (Theory A). Therapy helped him to discover that trying to solve his difficulties as an appearance problem fuelled and maintained his preoccupation and distress. We discussed that given his adverse early experiences of sexual abuse and subsequent bullying it was understandable that he had felt that he had no control over his life at the time, and that when discovering that people he saw as successful allegedly had good skin, it made sense that he started overvaluing the appearance of skin. Unfortunately Michael's ‘solutions’ namely his extensive avoidance, mirror checking and all the other BDD behaviours had kept him stuck in his preoccupation for the last 12 years. We therefore worked on strengthening Michael's belief in Theory B. According to Theory B his problem was one of preoccupation with his appearance and the perceived flaws in his facial skin are not as noticeable as they feel to him and do not mean that he is unacceptable. Testing out Theory B involved a great number of behavioural experiments that supported Michael in choosing to drop all his safety and avoidance behaviours to test out his appearance-related beliefs. For example, Michael discovered that even without using his elaborate washing routines others did not humiliate him by laughing, shouting or staring at him. Michael reflected that ‘others seem to mind their own business’ which led to a marked reduction of his conviction that he needed his washing rituals to stay safe in public. To consolidate this belief we carried out a series of experiments that went beyond what Michael thought people without BDD would do. This included putting on fake warts and spots that were clearly noticeable, and spending an extended period of time in public spaces such as the canteen, the residential community meeting or walking around in the grounds, while not engaging in any other safety-seeking behaviours such as walking fast, or avoiding eye contact. To his great surprise he was not humiliated and felt much safer than he had anticipated. His belief that others would shame him if not completing his washing routines dropped to 0%, and markedly improved his social functioning in the community. Behavioural experiments were optimized following Craske et al.’s (Reference Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek and Vervliet2014) inhibitory learning approach by maximizing expectancy violation of beliefs rather than fear habituation, generalizing all experiments to multiple contexts and helping Michael to label his affect.

Alongside these experiments we also worked on developing healthier and more functional ways of using mirrors such as only briefly looking in the mirror when needed, focusing outwards on his whole reflection, instead of zooming in on his perceived flaws thus magnifying his felt impression of unclean skin (similar to the perceptual training described by Wilhelm et al. Reference Wilhelm, Phillips, Didie, Buhlmann, Greenberg, Fama, Keshaviah and Steketee2014). Furthermore Michael practised attentional training that helped him to focus outwards in social situations (following Veale & Neziroglu, Reference Veale and Neziroglu2010) and to speak up in community meetings without using safety behaviours. Michael had also significantly reduced his social comparing and his time spent ruminating, which further reduced his preoccupation.

At week 5 Michael was less avoidant, more vocal in community meetings and with his peers at the unit, and generally seemed more hopeful about his future. He started connecting with his valued activities such as playing football or going to the pub to watch sporting events. Despite this good progress Michael was still easily triggered into feeling ashamed and humiliated. While he ‘knew’ that others would not judge him he still felt an overwhelming need to have better skin whenever he felt threatened or challenged. This was an important discovery which required a revision of his formulation. Michael's preoccupation and the felt impression of his perceived flaws in his skin was particularly strong when something reminded him emotionally of his early experience of being shamed, which subsequently triggered a need to control his skin, or hide from others. Michael was initially not aware that he was experiencing the same affect (from a time when his earlier life had felt out of control) without recollecting the context [see Ehlers & Clark's (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) description of affect without recollection].

We therefore used imagery rescripting, following Arntz's protocol (Arntz & Weertman, Reference Arntz and Weertman1999) to help Michael to emotionally process and re-evaluate these shame-based memories that continued to shape his experience of the world. We rescripted the experience of sexual abuse and a numerous bullying incidents that had followed this. Michael was able to revisit these experiences through imagery exercises. Through a process of ‘mental time travel’ he was able to imagine his adult self going back in time to rescue his younger self and confronting the abusers confidently, chasing them away and demanding apologies for their bullying behaviour. Imagery rescripting also aimed at helping him to process the understandable anger that he had developed about these experiences but had suppressed for so long. Imagery rescripting proved to be a powerful therapeutic tool for Michael. He reported that he felt much safer in social situations and appeared more resilient towards situations that would previously have triggered him to feel threatened. He started to break the emotional link between shame-driven experiences and current triggers. To support this learning process Michael also used stimulus discrimination (see Ehlers & Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) to contextualize his past and present experiences. This involved focusing on as many details as possible that discriminated the past from the here and now. To further enhance breaking these emotional links Michael wrote a compassionate letter to himself that summarized his new formulation of his difficulties. In this letter he explained to himself why it was understandable that he felt and behaved the way he did, but that the world was now much safer than he had feared. Throughout treatment we helped Michael to develop and consolidate his self-soothing skills and compassionate skills such as soothing rhythm breathing.

Revisiting and rescripting early experiences of shame had helped Michael to further recover from his anxiety, which was clearly reflected in his scores dropping into the low clinical range. However, Michael was still easily triggered into old shame-based feelings which subsequently could, sometimes seemingly out of the blue, flare up his felt impression and trigger BDD behaviours. In our discussions it became clear that Michael had been left with intense feelings of anger towards his mother, and in particular towards his brother. Two further interventions aimed to help Michael resolve his anger. First, Michael wrote letters towards both his mother and his brother in which he expressed his feelings of hurt and anger; to his brother for bullying him and ‘making my life hell’, and to his mother for ‘not protecting me’. Second, we invited both the mother and the brother to attend joint sessions with Michael towards the end of his treatment. We first met with his mother twice. Michael read his letter to her in the session. It was initially difficult for his mother to accept responsibility for the role she may have had in the development of her son's problems and during the session Michael perceived her as being defensive and not caring when she defended Michael's brother's behaviour. However, following this session, after giving what she had heard further thought, she was able to authentically acknowledge Michael's difficult early experiences and apologized sincerely to her son for not protecting him and not making him feel safer during his childhood. In week 14 his brother attended our joint session. As before with his mother, Michael read aloud the letter that he had written to his brother. He became tearful and trembled when doing so. To Michael's surprise his brother listened quietly without defending himself. He was seemingly moved, said he did not recall many of the bullying incidents (which he had put down as normal sibling rivalry); however, he fully acknowledged how these experiences must have affected his brother. His brother told Michael that he loved him and asked for his forgiveness, expressing his wish to have a good relationship with Michael from now on. This was the moment that Michael truly recovered from his BDD as it allowed Michael to forgive and put his shame-based memories to rest.

Therapeutic community

Michael's treatment occurred in a residential therapeutic community setting which promoted a caring and safe environment through adopting compassion-focused therapy and functional analytical therapy principles (see Veale et al. Reference Veale, Gilbert, Wheatley and Naismith2014c for a systematic review of therapeutic communities and a proposal for compassion-focused environments). Michael and the other residents attended a weekly compassion-focused therapy group that focused on de-shaming through both psychoeducation of how his old and new brain create tricky feedback loops, and how learning skills of greater compassion and mindfulness may help to break out of them. Michael learned that he was not to be blamed for his BDD and that his suffering made sense in the context of his past experience. Residents were encouraged to support each other's recovery through responding to each other's acts of courage with compassion.

Results

Michael made steady and consistent progress throughout treatment. Table 1 summarizes the scores of his outcome measures.

Table 1. Michael's outcomes on all measures over the course of his treatment and follow-ups

Ast, Assessment; BDD-YBOCS, Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale modified for BDD; AAI, Appearance Anxiety Inventory; BDD-D, Body Dysmorphic Disorder – Dimensional Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; RCI, Reliable Change Index.

*Comparing pre-treatment with 18-month follow-up.

CBT for BDD, as based on Veale's cognitive model, was highly effective in formulating his difficulties and guiding treatment. The first stage (week 1–5) focused on behavioural interventions which led to a marked reduction in his preoccupation with his skin, and resulted in improvement of his mood and functioning. At the end of week 5 Michael had made remarkable progress which was reflected by a drop on his weekly AAI, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 which all reduced between 35% and 60% and were now in the mid-clinical range. His belief in Theory B had increased to 70% (up from 0% at the start of treatment). At this point it was formulated that shame-based memories appeared to be at the root of his suffering and seemed emotionally fused with his felt impression. Therefore the second stage of treatment (weeks 6–11) focused on imagery rescripting of past experiences, alongside helping Michael to build greater compassion and self-soothing skills. Scores on all measures continued to drop. In the final stage of treatment (weeks 11–16) Michael was able to further process his emotional memories by expressing and his feelings of anger towards his mother and his brother, and after doing so, all scores were in the non-clinical range. Figure 2 displays Michael's self-portrait both at the beginning and at the end of treatment, clearly showing how his perception of his facial appearance had changed. The marked improvement was reliable and clinically significant as indicated by the drop in his BDD-YBOCS at the end of treatment, 3-month, and 18-month follow-ups (Reliable Change Index=8.19).

All gains were maintained at the 3- and 18-month follow-ups; in fact they continued to drop to zero suggesting a full and stable recovery from his BDD. At 18 months post-treatment Michael returned to the hospital as a recovered service-user to inspire other residents and share his remarkable recovery with some of the BDD patients, instilling hope for their treatment. By this time Michael was in full-time employment, had a girlfriend, and was connecting with his friends; he had truly reclaimed his life.

When leaving the programme Michael believed Theory B 100% saying ‘There is nothing wrong with my skin’. On reflection Michael thought that processing his relevant past experiences, expressing his anger and forgiving his brother, alongside experiencing safeness without using safety-seeking behaviours had allowed him to make a full recovery.

Discussion

The current case study demonstrates effective therapy of a young man who presented with treatment-resistant BDD. The main objective of this study is that CBT enhanced with emotion-focused techniques (such as imagery rescripting and compassion-focused techniques) may improve outcome, particularly when shame and anger are at the emotional root of the BDD. Michael had suffered from longstanding treatment-resistant BDD, and low mood secondary to his BDD. He did not meet diagnostic criteria for other Axis I disorders. During his 4 months of intensive residential treatment he made a progressive and full recovery. CBT is the first-line treatment for BDD and its evidence base continues to emerge (Veale et al. Reference Veale, Anson, Miles, Pieta, Costa and Ellison2014a ). However, full recovery from severe BDD is rare. For example, in their recent RCT Veale et al. (Reference Veale, Anson, Miles, Pieta, Costa and Ellison2014a ) found a mean reduction of 40% on the BDD-YBOCS at 1-month follow-up. Previous early trials led to average improvements in BDD symptomatology ranging from 42% (Veale et al. Reference Veale, Boocock, Gournay, Dryden, Shah, Willson and Walburn1996) to 52% (Rosen et al. Reference Rosen, Reiter and Orosan1995). Wilhelm et al.’s (Reference Wilhelm, Phillips, Didie, Buhlmann, Greenberg, Fama, Keshaviah and Steketee2014) recent RCT found symptom reductions of 55% among treatment completers with gains maintained at 6 months follow-up. There is a lack of process research and a scarcity of mediator analyses. Therefore it is difficult to ascertain which of the various cognitive and behavioural interventions contribute to what extent to recovery. In Michael's case it appeared that his felt impression was strongly fused with past experiences of sexual abuse and being bullied and shamed by his brother. Behavioural interventions (e.g. leaving his room without engaging in ritualized washing or putting on fake warts in public) helped Michael to become significantly less preoccupied with his skin and improve his functioning, but Michael remained vulnerable to being triggered into feelings of shame which in turn triggered his BDD. Therefore the second stage of his treatment focused on processing relevant past experiences. Imagery rescripting was the main technique used, alongside CBT for BDD, and this seemed to further boost his recovery as suggested by a marked drop in his AAI from week 4 to week 5. This finding links in with recent research applying imagery rescripting to help people with BDD. Two recent single-case series both adopting an A-B design, demonstrated efficacy of imagery rescripting after only one (Willson et al. Reference Willson, Veale and Freeston2016) or two sessions (Ritter & Stangier, Reference Ritter and Stangier2016). In Ritter & Stangier's study (Reference Ritter and Stangier2016), five of their six patients responded to the intervention, and overall symptoms on the BDD-YBOCS had improved by 26% at 2-week follow-up. Similarly, Wilson and colleagues found in their multiple-baseline single case experimental study of using imagery rescripting as a stand-alone intervention, that four out of their six BDD participants showed clinically meaningful improvements. These findings, in conjunction with the present study, suggest that imagery rescripting may enhance treatment for BDD. However, in Michael's case imagery rescripting did not appear sufficient to fully resolve past feelings of shame and anger. While Michael's appearance-distress greatly improved when imagery rescripting was added to this treatment, he continued to monitor social threat and, while much less frequently, was still triggered into feeling ashamed, particularly at home around his brother. Only after Michael's anger was expressed and acknowledged (stage 3, weeks 11–16) could he truly put his shame-, and anger-based memories to rest which ceased to fuse with his felt impression. Michael achieved this through writing an ‘angry letter’ to his mother and brother who were both able to authentically apologize to Michael for the pain caused to him by their actions. Once the emotional associations between his bullying experiences and his present suffering were broken, his BDD was fully overcome. Veale & Gilbert (Reference Veale and Gilbert2014) recently wrote about the function of BDD symptoms in relation to a perceived threat of a distorted body image and past aversive experiences. In line with their study, we conceptualized Michael's avoidance and BDD behaviours as threat-based safety strategies that functioned to monitor and avoid social threats of shame and rejection, which Michael had developed in response to humiliation and bullying. As a child he had associated good skin with safeness, and felt, as long as he had good skin, he had some control over his life. These associations were only broken once his aversive past experiences were fully processed. Michael also developed effective self-soothing and self-compassion skills that appeared to help de-shame his past, and also helped him disengage from threat monitoring and self-critical thinking.

Limitations

This study has strengths and limitations. Its main strength is Michael's remarkable recovery that appeared possible once CBT for BDD was enhanced with emotion-focused techniques. We hypothesized that his felt impression of poor facial skin was fused and driven by shame-based early memories. Another strength is the use of weekly symptoms and process measures that allowed for an accurate monitoring of Michael's recovery and its link with the various interventions. The long follow-up appointment of 18 months gives us confidence that Michael's recovery is stable. A number of limitations need to be highlighted. First, naturally caution is warranted when evaluating these findings as, of course, generalizability is limited due to the single-case design. Second, this single case was non-experimental and did not use clearly defined baselines and control interventions to allow for stronger conclusions. More research is needed and in particular multiple single-case experimental designs may help to disentangle the effects of each of the various treatment components. Daily individualized measures may further allow tracking of mechanisms of change and fine-grained analyses of its related processes. For example, it would be of interest to relate daily measures of shame and anger before and after imagery rescripting sessions, family sessions, or link it with practicing self-soothing skills. Furthermore, to assess shame and anger this study relied on self-reports by the client and clinical observations rather than systematic measures which future studies may wish to include to obtain more quantifiable outcomes. Finally, various dimensions of therapy such as length of sessions or their spacing in time were not controlled for. A recent systematic review of the optimal delivery of therapy by Sündermann and colleagues (O. Sündermann et al., unpublished observations) sets out a framework for researching these dimensions. For example, future studies may explicitly negotiate the length of an individual session with the client rather than offering a standard, inflexible therapy hour. While there are natural constraints in busy outpatient clinics, a residential or inpatient setting as described here may be optimal to test out flexible session times in people with severe anxiety.

Conclusion

In summary, this case study illustrates the successful recovery of a young man who attended residential intensive treatment for his severe BDD following treatment failures in the community. The study demonstrated the effective enhancement of CBT for BDD using emotion-focused techniques to process past shame-based experiences. Full recovery of treatment-resistant BDD is rare, and Michael was fortunate that his great courage in expressing his anger was met with true compassion by his brother (‘his greatest bully’) which enabled Michael to forgive his brother and truly put his memories to rest. The study also highlights how formulating BDD within a contextual and functional framework, and adopting compassion-focused therapy principles may further enhance CBT for BDD.

Acknowledgements

D.V. acknowledges salary support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLAM) and the Institute of Psychiatry (IoP), King's College London. NIHR, SLAM and IoP had no role in the study design, writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit this paper for publication.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Learning objectives

-

• Emotion-focused techniques may enhance CBT for BDD

-

• Imagery-rescripting, compassion-focused techniques and family work may help to process past relevant experiences

-

• Considering functional and contextual aspects of BDD may further increase treatment effectiveness and engagement

-

• Self-portraits of perceived flaws are helpful additional pre-post measures

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.