This virtual special issue is the outcome of a project entitled Women and JAS, which was launched by the coeditors of the Journal of American Studies in October 2019 to document the involvement of women in the journal's day-to-day business from its inception in 1956 as the Bulletin of the British Association for American Studies.Footnote 1 The project arises out of – and will hopefully contribute to – larger conversations about the progression of women scholars in academia. While the UK and US higher-education contexts (the contexts most pertinent to this discussion) differ, there are notable similarities in terms of the relationship between gender and career advancement.Footnote 2 Both witness attrition of women from academia as they progress from undergraduate studies to PhD and beyond;Footnote 3 both see disproportionate numbers of women scholars employed in precarious, part-time and/or teaching-only roles; both see a very low proportion of women in senior professorial roles; fewer women in both locations apply for (and are, therefore, awarded) major grants.Footnote 4 In the UK, specifically, recent conversations around gender inequality in higher education have revolved around issues (and initiatives) such as the gender pay gap,Footnote 5 Athena SWAN,Footnote 6 sexual harassment and the effects of nondisclosure agreements (NDAs),Footnote 7 caring responsibilities and affective labour.Footnote 8

Of course, the foregoing is a mere snapshot of what is a complex and wide-ranging set of issues. This project addresses one important facet of these discussions: the role of women as authors, peer reviewers and editors at the Journal of American Studies. A 2018 Royal Historical Society report, the result of a survey of 472 history academics in the UK, found,

Gender inequality was experienced, seen or suspected by a high proportion of all survey respondents, especially ECRs [early-career researchers], in all the main fora of intellectual exchange in History: 43% saw it in journal editorships; 44% in appointments to editorial boards; 49% in seminar programmes; 53% in learned societies; 59% in conference programmes; and 65% in selection of keynote lecturers.Footnote 9

Given the role journal editors play as academic gatekeepers in some of “the main fora of intellectual exchange,”Footnote 10 the JAS coeditors are keen to account for and address gender-based inequality in the journal, and, in doing so, build on the legacy of our predecessors.Footnote 11

Encouragingly, the last few years have seen several humanities and/or area studies journals take stock of their record in respect of publishing work by women scholars and/or research devoted to women's lives, literatures and histories. For example, in the issue marking its fiftieth anniversary, the Irish University Review included “an overview of the changing demographics of contributors to, as well as the changing focus of articles published within,” its pages.Footnote 12 Incoming editors of the American Journal of Political Science, Kathleen Dolan and Jennifer L. Lawless, examined submissions to their journal between 1 January 2017 and 31 October 2019. They found that women accounted for 25 percent of article submissions but that 35 percent of accepted articles had at least one female author.Footnote 13 Separately, and using JSTOR Data for Research, Chad Wellmon and Andrew Piper collected statistics on women authors publishing in twenty humanities journals in the five years to 2015 in order to compare their findings in respect of four key journals (Representations, Critical Inquiry, PMLA and New Literary History) across a wider data set. They found that “gender equality in academic journals is moving slowly toward parity, though not universally across the field, nor is the process close to completion.”Footnote 14 The challenge for the editors of JAS – as for other journals – is to make meaningful changes based on the evidence that has emerged from these audits.

The Women and JAS project has three key goals: (1) to generate, publish and analyse quantitative and qualitative data surrounding women's involvement in the journal (as authors, peer reviewers and editors) during its history; (2) based on this quantitative and qualitative data, to suggest ways of addressing aspects of the journal's business where participation by women might be encouraged and enhanced; (3) to identify, highlight and showcase a range of important articles by women across the journal's history. This introduction, coauthored by Maryam Jameela (intern at Women and JAS) and coeditors Sinéad Moynihan and Nick Witham, begins by identifying the methodology used to generate the data (including its limitations); moves on to provide accounts and analyses of the quantitative and qualitative data; suggests some “ways forward” based on what we have learned from the project; and, finally, introduces the scholarship by women, published historically in JAS, that makes up the special issue.

Before we move on to the substantive detail of methodology, data and analysis, it is worth sketching briefly some relevant contexts in respect of publishing journal articles in a UK context, from both an editor's and an author's perspective. The following will be familiar to those actively researching in higher education in the UK, but perhaps less so to those working outside it. First, it is important to note that journal editorship – while considered an important scholarly endeavour and rewarded in promotion applications – is rarely counted as labour by the institutions for which we work. The degree of support editors receive varies from institution to institution, of course. But it is uncommon in the UK for journal editors to receive any “buyout” of the time they are expected to devote to teaching, research and administration (or “service”) in order to carry out editorial work. As one former JAS editor put it,

Journal editors are not, generally, given much in the way of institutional support by their home universities in the UK. It might merit a line on a webpage, the REF submission, or the workload planner, but it was not seen as something that ought to be facilitated by additional resources in terms of time or, say, teaching buyout.

Of course, editorial work does come under the umbrella of “research,” but few heads of department at UK institutions would accept “I was editing a journal” as a valid reason for an individual not publishing their own scholarly articles and books in line with Research Excellence Framework (REF) expectations (see below). Simply put, while journal editing in the UK is a professional privilege and a marker of prestige, the labour is rarely acknowledged at an institutional level. Given that it is work carried out in addition to regular teaching, research and administration loads, there are significant gender implications in respect of editorial work, which raise important questions: who is more likely to apply for editorial positions as they arise? Who is more likely to be able to commit to the “extra” workload that will not be formally acknowledged by their institution? From 1967, when JAS, 1, 1 was published, to the end of 2014, JAS had eight editors, two of whom were women. From 2015 to 2018, there were coeditors (one man, one woman); this is also the case with the current coeditors, who are serving a four-year term from 2019 to the end of 2022.

Second, potential contributors to JAS who are based in the UK have to consider REF when they make a submission to the journal. Formerly known as the Research Assessment Exercise, this assessment of research quality in UK higher education takes place every five to seven years. Its role is to evaluate research at UK institutions in relation to three key areas: outputs (quality of articles, books, performances etc., weighted 65 percent), impact of the research outside academia (weighted 20 percent), and the environment that the institution fosters to support research (weighted 15 percent). REF panellists, comprising subject specialists, assign a star rating to every individual article, book, impact case study and so on. The highest grade is 4*, which is deemed: “Quality that is world-leading in terms of originality, significance and rigour.” The outcome of the REF determines how much “quality-related” (QR) funding an institution receives, with funding allocated on the basis of research activity assessed as 4* and 3* at a ratio of 4:1.Footnote 15

The REF regime has a number of knock-on effects for scholars of American studies (and, of course, all scholars) based at UK institutions. First, the bluntness of REF's method of quantifying research quality means that research outputs that don't conform to the “traditional” scholarly article or monograph are more difficult to evaluate and are less likely to be ranked 4*. Thus, although JAS's submission guidelines welcome contributions “that go beyond the normal confines of an academic article – whether these be Research Notes, States of the Field pieces, Thought Pieces, Forums and Roundtable Discussions, Exhibition Commentaries, Research Notes,” the reality is that we receive few (if any) submissions of this sort from UK-based scholars. The stakes of “REF-ability” are, of course, higher for those who are on the academic job market and/or are part of the academic precariat: many shortlisting committees literally scan CVs for “outputs” suitable for submission to the REF that might potentially be ranked 3* or 4*. Second, because of REF deadlines (at time of writing, this is 31 December 2020 for publications), an individual scholar may submit their research to a journal with “likelihood of being published in time for the REF,” a consideration that takes precedence over “fit,” “prestige” or a variety of other factors.

The implementation of broader policy agendas within UK higher education therefore has a significant, if often indirect, impact on the work of the journal. While a large number of our authors and peer reviewers are drawn from the US, Europe and Australasia, and our editorial vision encompasses everything that international and transnational American Studies has to offer, JAS is inescapably a product of the UK higher-education system: its editorial teams have always been employed at UK universities, and its sponsoring organization, the British Association for American Studies (BAAS), is also deeply embedded in it. While we hope that our observations about the gendered nature of academic publishing and editorial work speak to contexts beyond the UK, then, it is also important for all readers to understand that, without systematic overhaul of the UK higher-education sector, some of its limitations are inescapable.

METHODOLOGY

JAS has not historically collected diversity data on authors or peer reviewers. As such, there was no existing information on the gender of people publishing in and/or reviewing for the journal. The collection of this data required a detailed search of the archives of the Bulletin (1956–59) and JAS (1960–present) to collate the names of every author to have published in the journal. As well as collecting information on publication dates and article titles, gender was the key differential factor in the study, and was determined by searching the author's name online to corresponding use of pronouns either on academic profiles, in publication biographies, or elsewhere. This was not always a successful indicator of gender, particularly for authors publishing with the journal in its earlier years, and often required certain authors to be omitted from the pool of data.

We used this data to quantify the following:

• the number of articles published by women in the journal in the period from 1956 to 2019,

• the acceptance rates for articles submitted by gender over the past five years (2015–19),

• the makeup of the journal's pool of peer reviewers by gender over the past five years (2015–19).

Having separated women authors from men authors, we used NVivo to build a picture of topic areas and sifted through these results to examine patterns in publication of women authors across disciplines. Finally, this research was supplemented with qualitative surveys completed by previous editors, authors and peer reviewers.

METHODOLOGICAL LIMITATIONS

At this juncture, it is worth pausing to briefly interrogate the methodology used to arrive at these results. As diversity targets are becoming the norm in a number of fields, so too are journals carrying out gender appraisals of their publication histories. However, these processes are fraught with problems of best praxis relating to tokenism, racism and transphobia.

From the outset, the collection of data relating to authors’ gender for this study was challenging, in part because authors writing in the period from the 1960s to the 1980s had, for obvious reasons, little online presence. Largely, however, the key limitation of the approach taken by the research team derives from the fact that the majority of authors, at least until the last decade or so, did not include biographical notes with their articles. This required us to make a series of judgement calls to guess the gender of authors.

Other journals, especially those in STEM subjects, have used a similar process for determining the race and gender of research subjects, and the strategy speaks to an emphasis on practicality and logistics at the expense of recognition of trans* authors. For example, in their analysis of women's authorship in medical journals, Giovani Filardo et al. state that their analysis involved guessing gender based upon the researcher's apprehension of the first author's name, and if this remained unclear, using biographical notes through online searches.Footnote 16 Any authors whose gender could not be determined after this process were excluded from analysis. Other studies entered authors’ names into name-checking databases which categorized names according to the likelihood of being male, female or unisex.Footnote 17 Each of these studies utilized an approach to data collection that rests upon the deduction of individual researchers, allowing transphobic perceptions of which names appear female, male or unisex to shape, no matter how unwittingly, a framework of assumptions about gender identity and presentation, and thus to overlook nonbinary genders.

None of the studies referenced above consider the limitations of this approach, nor the impact of assumptions of gender. We raise these concerns not to argue that findings derived from such research are useless, but rather to recognize that transphobic methodologies are harmful to trans* people themselves. For example, a 2017 article by Erich N. Pitcher considers the impact of misrecognition and misgendering of trans* people in academia, outlining how these aggressions translate into a hostile work environment. Based on interviews with a number of trans* academics who explain the psychological toll of misgendering, Pitcher argues that “each of the participants carried with them a stock of stories that situated them as unwelcome (mis)recognised guests within someone else's academy, bathroom, workshop, or meeting.”Footnote 18 These places are often the battleground for transphobic articulations of violence, and demonstrate the need to incorporate testimony of lived experiences from trans* academics who are routinely erased and ignored within the academy. Indeed, Pitcher goes on to describe the emotional toll of publishing the paper itself:

While there was much joy in connecting with trans* academics via this study, this manuscript was a difficult one to write. It was painful to repeatedly read the all too familiar mistreatment of participants. My experiences with writing about micro-aggressions may be secondary traumatic stress. Memories of my own experiences with anti-trans* micro-aggressions come flooding back and witnessing the pain of others was challenging.Footnote 19

Clearly, then, the social and emotional toll exerted on trans* academics by a society which routinely misses and erases them must be considered and confronted in a study such as this, rather than relegated to the footnotes. Data generation and analysis are not neutral ground and, as the discussion above demonstrates, decisions on how to undertake research always involve individual judgements about who can be said to belong to a particular group. This is not to argue that our findings are without use, but rather to paint a fuller picture of our process and to signal the overhaul required in diversity initiatives not only in terms of analysis of data, but also methodologically, via data collection, and, indeed, epistemologically, via interrogation of the very concepts used to frame such research.

QUANTITATIVE DATA AND ANALYSIS

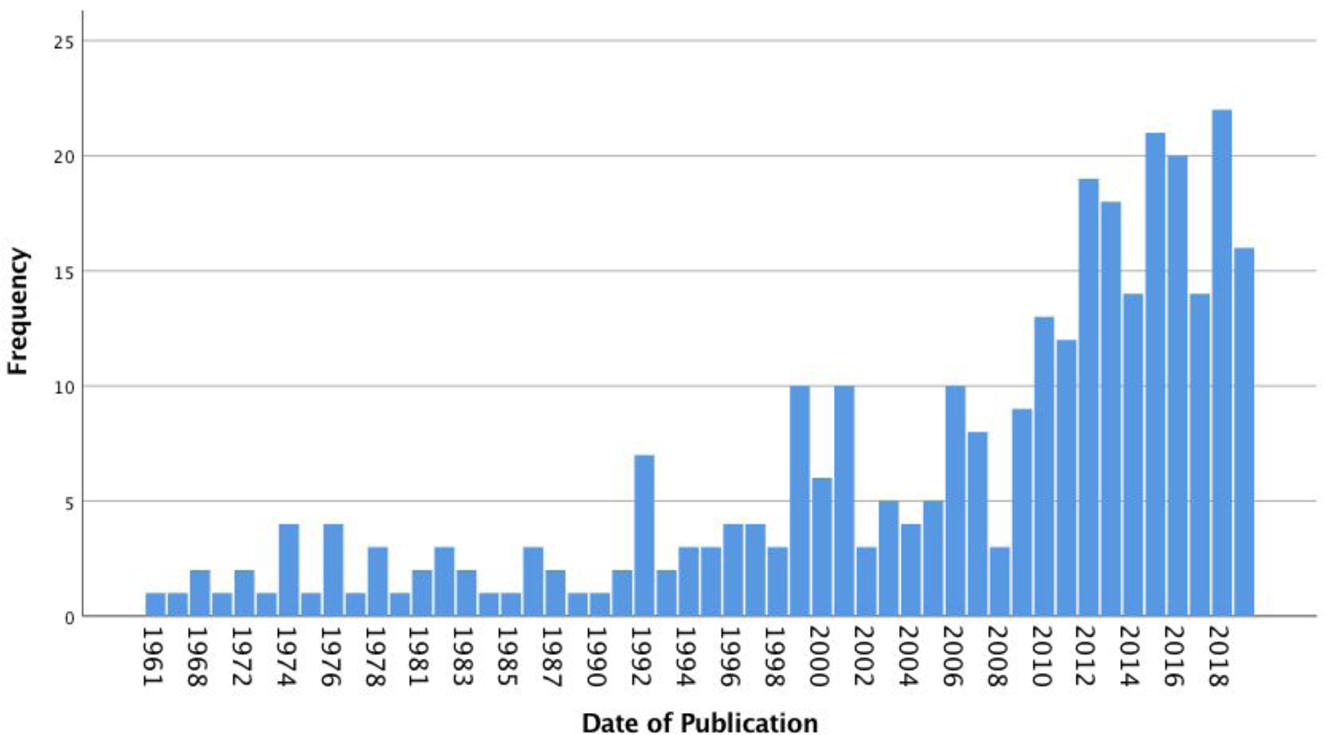

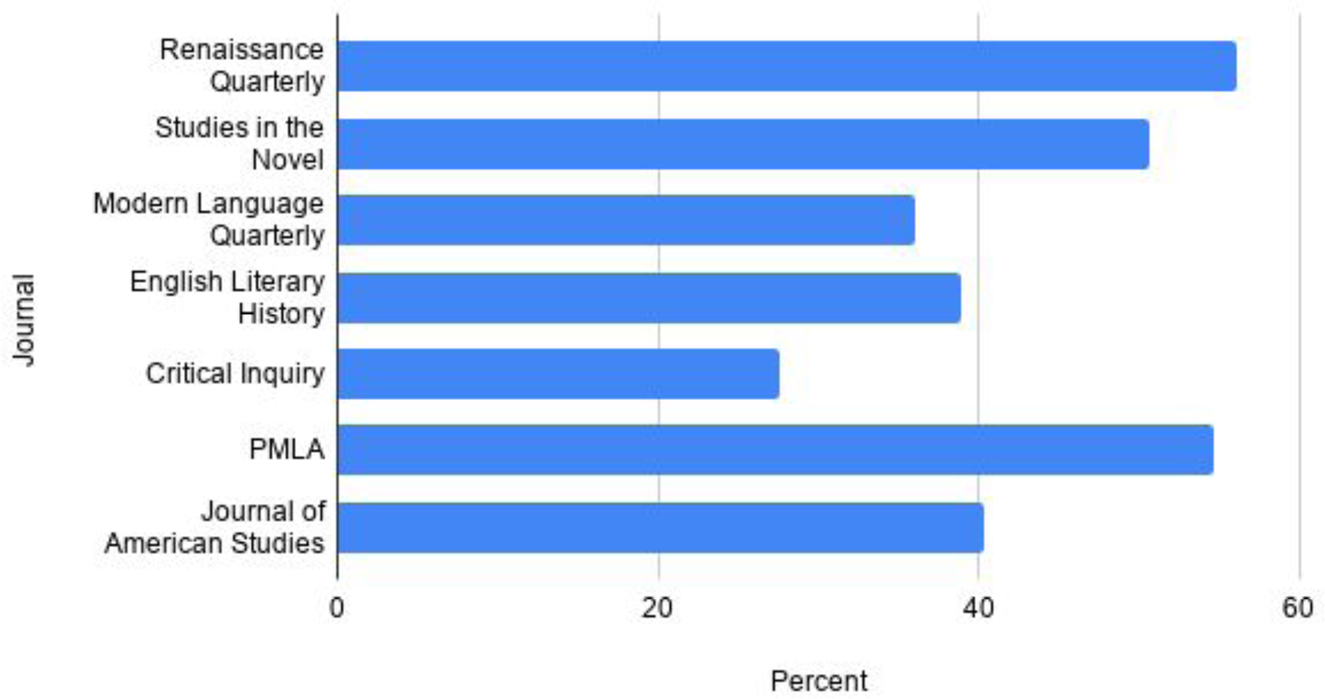

The data clearly demonstrate that, as women's presence and visibility in American studies have increased since the establishment of the field in the UK in the 1950s, their presence and visibility in the pages of the journal have also increased (see Figures 1 and 2). Women now make up a substantial number of the authors published in the journal – in the volumes published between 2010 and 2015, between 32 percent and 58 percent of all authors. These figures mean that JAS's representation of women authors is in line with that of a range of comparator journals (see Figure 3).Footnote 20

Figure 1. Gender breakdown of Bulletin and JAS.

Figure 2. Women authors over time.

Figure 3. Average women authors across journals.

Furthermore, the data on acceptance rates (see Figures 4 and 5) shows that articles submitted by women between 2015 and 2019 resulted in an acceptance rate of 37.8 percent, while articles submitted by men in the same period resulted in an acceptance rate of 36.9 percent. As well as the increasing representation of women authors over time, then, our data also point to a relative balance of editorial outcomes over the past five years: women are about as likely to have their work accepted for publication as men. As such, it is possible to identify a narrative of long-term change: the representation of women authors in the pages of the journal has increased over time, and these gains appear to be stable and sustainable, given the comparable acceptance rates across genders.

Figure 4. Acceptance rates of submissions from women over the past five years (2015–19).

Figure 5. Acceptance rates of submissions from men over the past five years (2015–19).

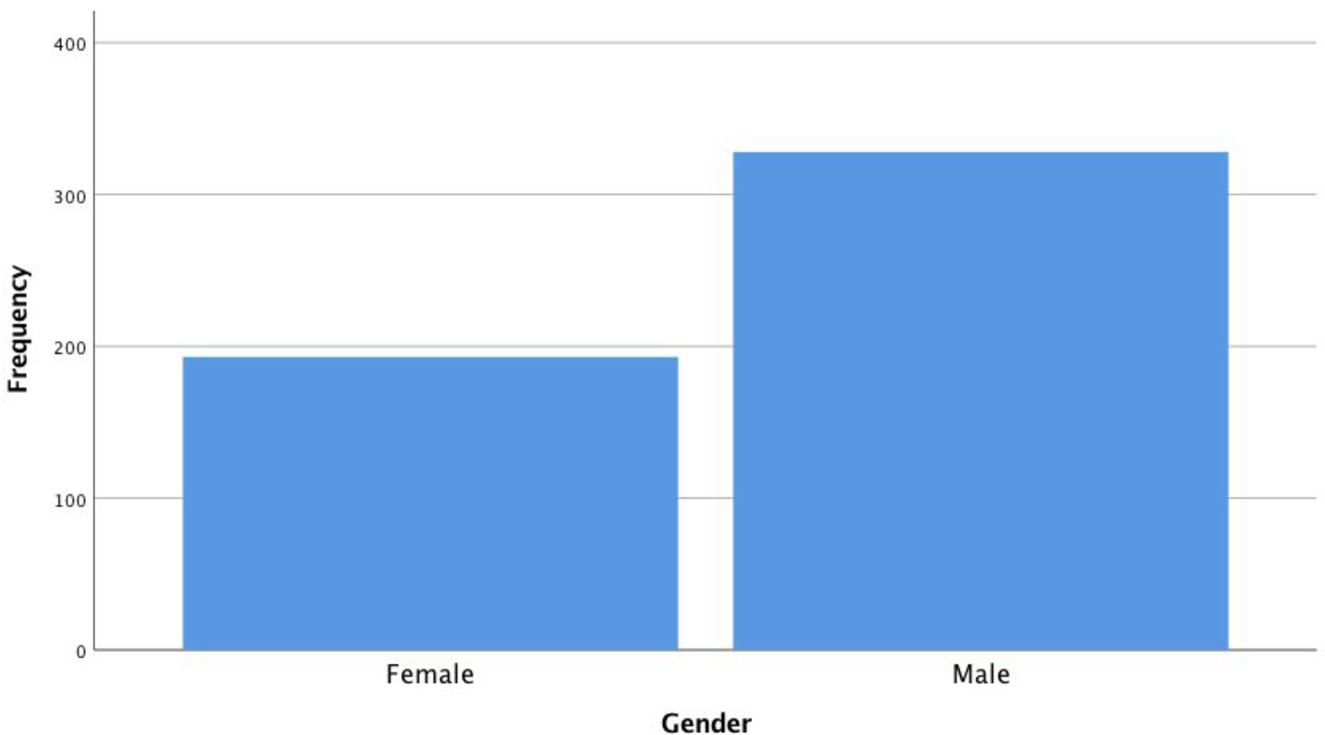

However, the data also provide clear insights into continuing gender imbalances in the journal's practices, both in the pipeline to publication and in our editorial practices. First, submissions data for the period 2015–19 (see Figure 6) shows that men (62.6 percent) are significantly more likely to submit articles to the journal than women (36.8 percent). This demonstrates that while women's chances of being published once they have submitted are roughly equal to those of men, the number of submissions by women is substantially lower than those by men. The implication of this trend is a cause for concern, and suggests that while editorial practices have allowed for the “fast-tracking” of articles by women to publication in order to balance gender ratios in individual issues, the longer-term trend is, ultimately, for articles by men to be published in greater number than those by women. In the longer term, then, “fast-tracking” is not a sustainable strategy. At time of writing, of twenty-eight articles in the journal's article bank (articles accepted and ready for publication, but which have not yet been allocated to an issue), six are by women with a seventh coauthored by a woman. A challenge, going forward, is that several scholarly journals have noticed submissions by women decline from March 2020 on, a trend that coincides with the global effects of COVID-19. For example, the Journal of Contemporary History recently compared submissions from April to June 2019 with those from April to June 2020. While a substantial increase in submissions was noted (25 to 72), the proportion of women submitting fell from 55 percent in 2019 to 35 percent in 2020.Footnote 21

Figure 6. Gender breakdown of all submissions to JAS over the past five years (2015–19).

Second, in the same period (2015–19), JAS's pool of peer reviewers (totalling 751 scholars from all over the world and in a variety of career stages) consisted of a lower percentage of women (43 percent) than of men (57 percent) (see Figures 7, 8 and 9). Throughout this period, the journal's editorial staff have pursued a policy of foregrounding the names of women scholars when lists of potential peer reviewers for articles are drawn up. As such, this points to an important, if unsurprising, inequality in the editorial process: articles are significantly more likely to be reviewed by men than by women.

Figure 7. Gender breakdown of peer reviewers at the Journal of American Studies.

Figure 8. Number of women peer reviewers 2015–19.

Figure 9. Percentage of women peer reviewers 2015–19.

QUALITATIVE DATA AND ANALYSIS

Researchers with a similar remit to investigate gender inequality often begin with certain assumptions. In this instance, we initiated our study with an expectation that we would find an underrepresentation of women in the pages of JAS. To a significant extent, this is what we found. While quantitative data such as those presented above are therefore a vital starting point for analysis, it does not adequately represent the complex realities faced by women who work in academic publishing as authors, peer reviewers and editors.

To better capture these experiences, we designed a survey and solicited responses from women authors, peer reviewers and former editors of the journal (men and women). We received nine responses. While small in number, those who responded made a number of valuable points.

a Editorial practices. Several of our respondents drew attention to the ways in which journals’ editorial practices are impacted by gender. At one level, this is about the tone of peer reviewing, i.e. how readers communicate both their praise for, and their constructive criticism of, the articles they are asked to review. One respondent recommends, “Editors should monitor readers and not use readers again if they have concerns about their practices.” At another level, it is about how editorial staff work to support authors in developing their articles. The problems associated with these questions are not inherently gendered, and, as one of our respondents put it, “peer review by its very nature is a difficult and abrasive business” for everyone. However, in the case of “revise and resubmit” decisions (the most likely outcome for a submission to JAS that gets past the initial desk-review phase), men and women authors “often respond to these decisions quite differently,” with women less likely to resubmit, and, when they do, for the revisions process to take them much longer than men. The coeditors are hopeful that some of these concerns have already been addressed via the journal's recently published Peer Review Code of Practice, the foundational assumption of which is that “robust and rigorous critique in a supportive and courteous tone are not mutually exclusive endeavours.”Footnote 22 However, it is important to recognize that the uncertainties raised by peer review will not disappear overnight, and that supportive editorial processes and bespoke guidance for authors must always underpin high-quality editorial practice.

b Intersectionality. At least two of our respondents identified the extent to which the gendered nature of academic publication intersects with other identity positions, notably class and race/ethnicity. These comments highlight that, whilst it is vital to pay significant attention to the gendered inequalities in academic publishing, it cannot be taken for granted that publishing more women necessarily equates to a more “diverse” journal. There remains the issue of hiring women in all positions, of seeking out editors, authors and peer reviewers who would not otherwise come across the journal or have the opportunity of doing so. Single-axis analysis of gender thus has the potential to restrict the effectiveness of policy change. We have to start somewhere, but starting and restarting with short-term policy projects that do not connect through multiple generations of researchers restricts the progress of the work and has the potential to remain tokenistic. In any ongoing conversation, then, questions of intersections must be considered: analysis of gender should include an adoption of pro-trans* politics, anti-racist critique, class concerns, and a study of ableism.

c The politics of citation. There was some difference of opinion among respondents on this issue (“How useful is increased awareness of the politics of citation in enabling and equipping more women to publish in, peer review and edit for journals like JAS?”) One respondent wrote, “I think that any ‘citation affirmative action’ is merely going to hide the deeper structural inequalities which go beyond any publication.” Another responded, “I hate any reduction of publication to a primary focus on ‘politics of citation’ over any issue in our profession. That politics of citation has already led to the shackles of the REF.” However, another wrote, “A strong editorial policy about citing women, citing scholars of colour, would shift peer review practices to support different kinds of research.” A further, lengthy, response reflected on the author's own experience of poor citation practices and lack of scholarly integrity, asking, “how do scholarly communities hold their members to account and what is the role of journals?” They suggest that journals might require authors to “monitor their bibliographies and footnotes to ensure they include not only recent, ‘relevant’ scholarship, but scholarship that reflects the diversity of the societies in which we work and for whom we write.”

d Career development and career stage. One respondent wrote that

They added, “a journal cannot operate in isolation from the foundational issues of entry into profession and support of those trying to advance – so encouragement and action has to be given on those fronts.”there are foundational issues about entry into the profession and advance within it, especially obtaining a Ph.D. and a secure, long-term position. That would be my area of focus in discussions on ensuring just representation and recognition for women scholars; publication would follow naturally from an address of these foundational issues.

As coeditors of the Journal of American Studies, we recognize that publication in the journal should not be a “pay-off” for having achieved a certain academic standing and career status, but that it might itself be a step on a junior scholar's pathway towards secure employment. One of the key initiatives of our tenure to date has been the JAS “Office Hours” we held (in person) at BAAS 2019 and (via video conference) at BAAS 2020. They are open to all, but the majority of participants to date have been early-career researchers (ECRs). The purpose of this initiative is to hear about the research individuals are undertaking and to encourage submission to JAS. More broadly, however, we aim to demystify the process of academic publishing by putting “a face to a name” of the editors; talking individuals through the process that ensues after they submit their article to ScholarOne; and advising prospective authors on paying attention to the journal's “Instructions for Contributors,” the importance of abstracts/titles, and thinking carefully about what works as a PhD chapter versus a scholarly article.

The importance of career development relates to another issue that arose among respondents to the questionnaire, which is the particular vulnerability of early-career women to inequalities inherent in citational practices. One respondent noted that, in the context of a junior scholar's work not being appropriately cited by more senior scholars, “The risks in defending one's work are often too great for early career, untenured scholars and those whose gender, race, sexuality and class positions make their foothold in the academy less secure and the accusations less likely to be believed.”

e Formal changes as well as constructive conversations (i.e. instituting new policies and/or new approaches to the journal's practices, as well as amplifying women's work for and in JAS). In response to our question “What should journals be expected to do … to address gender inequality?” we received a number of proposals which, in some cases, overlapped with one another. We outline these only briefly here, because they are dealt with in greater detail in the following section.

At least two respondents suggested that JAS might commission women scholars to guest-edit special issues of the journal. Another suggested that, in addition to the data we have compiled on articles, we should pay attention to the books that are reviewed in the journal and who the reviewers are. Another proposal was to provide open access for published articles by women and minorities to increase the visibility of their work, enabling “scholars in low-paying, precarious positions [to] get their name out and potentially secure better positions.”

f Emphasis on institutions as changemakers as well as individuals. Several respondents suggested that an important approach to the problem of gender inequality should involve self-reflection amongst those in gatekeeping positions, as well as by individual women scholars as they develop their scholarship and/or mentalities in the context of a sexist academic landscape. For example, one respondent suggested that “the responsibility for addressing gender disparity should not lie only with women and nor should it be understood as a ‘deficit’ issue to be addressed principally by equipping women with more/better skills.” Another encouraged us to

confront and work out how to manage what some see as an uncomfortable truth: making space for women and people of colour may mean fewer opportunities and jobs for all white people and particularly for white men. But it will also mean that the work produced in and by the academy will have both integrity and relevance for the societies it serves.

Overall, then, these firsthand reflections help us identify some of the key challenges faced by authors, peer reviewers and editors working for academic journals in the humanities and area studies today. They point not only to the complexity of the situation “on the ground,” but also to the need for both JAS and BAAS to conceptualize the process of interrogating data relating to inequalities in the field of American studies as an ongoing process. While this special issue captures an important moment in time, then, its true success will be measured by the new initiatives and conversations it initiates.

WAYS FORWARD/PRACTICAL STEPS

More and Better Data Collection. As discussed above, the data collection for this study, whilst productive, was nonetheless problematic, and required us to identify authors’ genders via methods that are unreliable and potentially transphobic. Cambridge University Press's online submission system, ScholarOne, has the capacity to ask authors and reviewers to self-identify when they submit or agree to read work for us, and we will seek to proactively use this function moving forward. This will allow the journal to keep on top of data more easily, and continue to review our progress (or otherwise) on the representation of women. The collection of comparable data in relation to race and ethnicity will also be essential to future analysis of the journal's diversity initiatives, particularly given the importance of intersectionality, as discussed above, in any study of contributors to and peer reviewers for JAS. In addition, respondents to our survey suggested that we extend our data collection and analysis to the book reviews side of the journal, which we will actively pursue with associate editors Zalfa Feghali and Ben Offiler.

Peer Review. As noted above, cumulatively, from 2015 to 2019, 43 percent of our peer reviewers have been women. For most of those years, women comprised 38–44 percent of peer reviewers. In 2019, they comprised 55 percent of peer reviewers. It is too early to say whether the COVID-19 crisis will have a major impact on the number of women scholars undertaking peer review for JAS but we have already seen anecdotal evidence of this possible outcome: women citing childcare and/or home-schooling commitments as the major reason for declining peer review invitations. We recognize that peer review is one of those “extra” tasks that scholars try to fit in around, or in addition to, their substantial existing commitments. Short of a radical overhaul of, or dispensing with, peer review altogether, we are trying to think of ways of incentivizing peer review. In addition, there are ways of modifying existing material on the JAS website and in our automated communications that might encourage women reviewers.

JAS website and communications. After a panel discussion at the 2019 BAAS conference and a follow-up conversation at the JAS editorial board meeting in December 2019, it was agreed that the coeditors would draw up a Peer Review Code of Practice. This went live on the JAS website in February 2020. Prospective expert readers are now directed to this information before they accept our invitation to review an article. In light of feedback and discussion from the Women and JAS project, we will return to the Peer Review Code of Practice and provide specific guidance regarding unconscious bias and citation practices, which will also be highlighted in the “Information to Contributors” section of the journal's website.

Mentoring. One impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been to demonstrate how successful the journal's “Office Hours” approach to mentoring can be as a digital as well as an in-person initiative. We will therefore expand its scope and regularity to include twice yearly digital “office hours” as well as those attached to specific conferences at which the editorial team are in attendance. By doing so, we hope that these meetings will be more accessible to those unable to attend UK American studies conferences.

Guest-edited special issues. A number of respondents to our questionnaire suggested that JAS solicit special issues with women as guest editors. While we are mindful of the pitfalls of this approach, not least the potential to shift more unpaid labour onto women that may not be fully recognized by employers, we will actively pursue it, and, in doing so, consult with the journal's Editorial Board for guidance.

Engagement with BAAS. BAAS, the journal's sponsoring subject association, is a dynamic and thriving organization. We will continue to engage and connect with its multiple communities, in order to feed into larger conversations about diversity and inclusion in the field of American studies. In doing so, we are particularly keen to liaise between BAAS and Cambridge University Press to explore the possibilities of an initiative to provide opportunities for Open Access publication for women and scholars of colour in order to more effectively amplify their contributions to the journal.

THE ARTICLES IN THIS VIRTUAL SPECIAL ISSUE

The articles in this virtual special issue collect a selection of writing in the journal by women authors spanning the period from 1964 to 2015. They represent a wide range of disciplinary, geographical and chronological interests, and are organized into the following thematic sections.

Section I: Recoveries

The first section showcases articles that might be broadly categorized as “recovery work” (though not necessarily feminist recovery work). Christine Avery's article on Emily Dickinson, from 1964, appeared only nine years after the publication of Thomas H. Johnson's three-volume edition of Dickinson's poetry (from which Avery quotes). Johnson's edition was the first complete edition of Dickinson's poetry and was considered the authoritative one, at least until the emergence of R. W. Franklin's work, particularly The Poems of Emily Dickinson in 1998. Johnson's edition, along with that of Dickinson's letters, which Johnson coedited with Theodora Ward (1958), secured Dickinson's place in the canon of American literature. Avery's argument – that Dickinson was “out of sympathy with most of the basic assumptions of science, but some of its methods appealed to her and she was uniquely sensitive to the incisive quality of scientific terms” (53) – anticipates much later scholarly interest in the relationship between Dickinson's poetry and burgeoning scientific thought and endeavour.Footnote 23

The second article in the “Recoveries” section, from 1974, focusses on little-known African American magazines during the Harlem Renaissance. Shifting attention away from periodicals such as the Crisis, Opportunity and Messenger, coauthors Abby Ann Arthur Johnson and Ronald M. Johnson uncover the importance of Stylus, Fire!!, Harlem, Black Opals and the Saturday Evening Quill. While some of these have (since) attracted a good deal of attention from scholars of the Harlem Renaissance, what is remarkable is how contemporary the article's subject matter feels, given the predominance of the “material turn” in literary studies of the past decade. The same is true of Ann Massa's article from 1986, which historicizes Harriet Monroe's efforts to establish Poetry magazine in 1911. The digitization of Poetry (1912–22) by the Modernist Journals Project in 2009, along with several other “little magazines” of the modernist period, has both shaped and facilitated the material turn in literary studies.

Moving away from literary studies, the “recovery” context for Elizabeth Clapp's article from 1994 is the emergence of feminist histories. Clapp surveys this scholarship to show how bringing methodologies and approaches from women's history to bear on the history of the US welfare state has challenged many of the latter's assumptions: for instance, that women were passive recipients of welfare during the Progressive Era; and that policymaking was dominated by men. Instead, “A much more complex picture emerges … in which women are not only the clients but also the originators of welfare programmes, some of which may have been discriminatory towards women” (363). Using the juvenile-court movement as a case study, Clapp builds on this claim to nuance understandings of middle-class women's involvement in the welfare state, concluding that “there were differences among middle class women reformers themselves and that this influenced the kind of reforms they sought” (383).

Section II: American Spaces

The second section features a range of ambitious articles, each of which engages with American “spaces,” from historical spaces of conquest, colonialism and imperialism such as the frontier, the urban low country, the Atlantic world and Hawai'i, to more contemporary spaces of conflict such as post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans, and the Latin@ public sphere.

Dolores E. Janiewski's 1998 article on colonial and postcolonial discourses of the frontier highlights the multilayered contributions made by late nineteenth and early twentieth-century researchers and writers such as Alice Cunningham Fletcher, E. Jane Gay, Francis La Flesche, Margaret Mead, Archie Phinney and Christine Quintasket. These authors developed forms of knowledge and understanding of the conflicts and violence inherent in US territorial expansion. In doing so, they provided sites of “imaginative resistance” to the dominant narratives provided by historians and politicians such as Frederick Jackson Turner and Theodore Roosevelt. This meant that rather than being “the crucible of democracy and the birthplace of the quintessential American,” for these writers the frontier was instead remembered as both postcolonial and colonizing (82). Their narratives incorporated the perspectives of indigenous peoples (in the case of La Flesche, Quintasket and Phinney) and “sympathetic allies who analogized colonialism to their own experiences as women” (in the case of Fletcher, Gay, and Mead) (102). Developing a comparable set of themes but in the context of third-generation Asian American writers from Hawai'i, Rocío G. Davis's 2001 article argues that “place is at the very center of identity politics” via analysis of story cycles by Garret Hongo, Sylvia Watanabe and Lois-Ann Yamanaka. In different ways, then, these articles register the impact of the late twentieth-century “imperial turn” in American studies represented by signal texts such as Amy Kaplan and Donald E. Pease's Cultures of United States Imperialism (1993).

The next article in this section, Inge Dornan's 2005 study of “Masterful Women,” shows how, in the liminal urban spaces provided by the South Carolinian low country, colonial white women “performed vital and visible roles … as slaveholders.” In doing so, they “adapted and conformed to prevailing ideas regarding white women's place and role in colonial slave society as mothers, wives, widows, and, ultimately, as masterful women with slaves” (402). This intricate piece of social history demonstrates the power of gendered perspectives on the history of slavery in early America: “redrawing the current portrait” of the topic “so that it includes women slaveholders” was thus to recognize their vital agency in the processes of enslavement (402). Another complex urban space is probed in D'Ann R. Penner's 2010 article on post-Katrina New Orleans, part of a fifth-anniversary special issue dedicated to the topic and edited by Sharon Monteith. Drawing on extensive oral-history interviews with survivors of the hurricane, along with mental-health, disaster and public-health professionals, Penner argues that these traumatic experiences were remembered not only through the lens of environmental catastrophe (i.e. the impact of the winds and floodwaters), but also by the violent changes in the urban landscape they experienced as it descended into “a militarized zone” in which the city's African American inhabitants felt “singled out for persecution because of their race/ethnicity (and gender)” (573). In spite of vast differences in the geographical and chronological spaces they analyse, Dornan's and Penner's articles highlight the overlaps between gender, race, ethnicity and questions of urban space that are so vital to contemporary American studies.

The section closes with two articles that explore radically different intellectual spaces: the Latin@ public sphere and black Atlantic thought, via 2012 and 2015 articles by Marissa López and Karen Salt respectively. In a wide-ranging display of the interdisciplinarity inherent to contemporary American studies, López pursues the identity formation of “emo” teenagers in Mexican and Latin American communities in the US. This “unabashedly queer” teen aesthetic, López argues, draws our attention to the “utopian longing” inherent in a transnational community of young people with “its eyes not towards the past but towards an unscripted future full of undefined hope and redefined boundaries of race, ethnicity, nation, and opportunity” (918). Salt's article is another conceptual masterpiece, tracing the question of sovereignty via “Haiti's tangled and complicated geopolitical positioning within the Atlantic world” (267). Ultimately, she argues, “blackness as a concept, a stance and a performance transforms and haunts sovereignty and demands that it respond to the conditions that consistently challenge its existence” (286). As well as probing deeply resonant discursive spaces, both articles therefore highlight the immense benefits to American studies of scholarly boundary crossing via the introduction of insights from disciplines such as ethnography and political theory.

Section III: American Studies and American Self-Image

The issue's third section demonstrates the consistency with which JAS's women authors have interrogated, on the one hand, ideas of American national self-image, and, on the other, the nature of American studies as both a discipline and a body of knowledge.

The first two articles in the section focus on the theme of self-image, as narrated via the social history of immigration and the institutional history of art galleries. Bronwen J. Cohen's 1974 article on the relationship between nativism and the “Western myth” highlights how, in the final decade of the nineteenth century, Americans shaped their idea of westward-moving pioneers as those with identities at odds with Italian and Jewish immigrants. Cohen argues that, throughout the 1890s, Americans viewed themselves through a social Darwinist lens as “having fared considerably better in the evolutionary struggle” than recent Southern and Eastern European immigrants (25). To support these claims to racial superiority and nativism, they constructed myths of the frontier that placed westward movement as a “pre-eminently domestic migration” from which immigrants were excluded (38). Ultimately, Cohen argues, American national self-image in this moment revolved around the idea that “the immigrant was the scapegoat; the West contained the cure” (39). In her 1992 article on the foundation of the American National Portrait gallery in Washington, DC, Marcia Pointon continues this focus on self-image, by scouring the archival record to reconstruct the intellectual and political dynamics at work in the creation of this signal American artistic institution. The dominant view of the gallery, Pointon argues, was that it would deploy portraiture “to maintain a status quo against the threat of revolutionary social transformation in the late 1960s” (359). That it was opened in the autumn of 1968, when much of the city was experiencing the fallout from that summer's racial uprisings, only served to highlight the problems of such an attempt at national self-definition. As Margaret Mead, who spoke at the gallery's opening, commented, “This is a black city. There's something wrong with this audience. Some people are not here” (358). The observations raised by these articles, about the links between between nativist rhetoric and American self-image, and about who is and is not included in dominant, state-sponsored narratives of American culture, consequently seem uncannily prescient today.

The issue's final two articles refocus our attention on questions of (inter)disciplinary self-image, probing as they do the manner in which American studies has responded to the intellectual demands placed on it by recent academic and political developments. Consciously situating herself as part of a community of scholars “working outside the US,” Milette Shamir, an Israeli Americanist, interrogates the theoretical dynamics of multivalent efforts during the 1990s and 2000s to “internationalize” American studies (376). In spite of these much-needed developments in the field, in which this journal has itself participated, Shamir does vital work in highlighting how “the new, multicultural American Studies remained – though rarely declared itself so – a patriotic project anchored in a discourse of the self” (378). To rectify this situation, she suggests a theoretical reckoning with the role of the “foreigner” within Americanist discourses, which she describes as “the primary prerequisite for a productive encounter between US and foreign Americanists” (388). In her 2011 article on representations of 9/11 in American studies, Lucy Bond, a British Americanist, extends some of the questions raised by Shamir, arguing that the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 are “subject to a crisis in criticism” because of an overwhelming reliance on narratives of trauma and rupture in explaining their significance. This has meant that “much-needed counternarratives” have failed to emerge. The provocative and insightful analysis offered by these articles prompts us to remember that American studies is an (inter)discipline that is never settled, always in motion, and constantly open to reconfiguration and critique.

Overall, then, we present this virtual special issue to our readers in the spirit of both self-critique and celebration. JAS is, and will continue to be, focussed on grappling with the long-term and challenging work of better supporting women Americanists. The quantitative and qualitative data compiled as a part of this report will help us to pursue this goal, and, in doing so, we welcome feedback and critique from our readers. However, at the same time as we recognize the ongoing inequalities in academic journal publishing, we also believe that it is vital to highlight women's contributions to the journal throughout its history, whether as authors, editors or peer reviewers. In doing so, we hope that our readers will come away with a new appreciation of the contributions made to American studies not only by the journal and its women contributors, but also and more specifically by the articles we have chosen to foreground.