Introduction

With the Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (TWWC), Esping-Andersen presented a typology of welfare state regimes that was intended to draw the ‘big picture’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 2). On the one hand, he did not want to lose himself in the details of the various social programmes but to expose general patterns of welfare provision beyond policy borders. On the other hand, as indicated by his book's title, Esping-Andersen was not merely interested in the welfare state as a means of social amelioration (what he termed the narrow approach of researching the welfare state), but also in ‘the state's larger role in managing and organizing the economy’ (the broad approach) (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 1–2). His typology appeared to be a good tool to bring order to the complex variety of welfare systems.

However, it was only a few years after the publication of TWWC that alternative classifications mushroomed. In the first part of this article we review these proposed alternatives. We demonstrate that they arose because TWWC was not able to live up to its high ambitions. Instead of covering all aspects of welfare regimes, it had only focused on specific areas. In consequence, the initial TWWC typology did not turn out to be a suitable framework for every aspect in the realm of welfare capitalism.

Figure 1. Linking the welfare regime to the economy – steps in the research process

By and large, the allocation of countries to these alternative classifications conformed to Esping-Andersen's typology. These findings have often been interpreted as sufficient evidence that the respective policy fields were well-covered by TWWC after all. However, instead of contributing to an integrated, holistic approach, sector-specific findings were simply added up. In consequence, the interplay between the different areas has often been ignored. It was the aim of Esping-Andersen to develop a comprehensive typology that integrates the different areas of research. As every typology ‘is the initial stage of a theory of politics’ (Peters, Reference Peters1998: 95), this approach would help expose the correlations and interactions within and between the types and improve our understanding of the causal mechanisms at work. In the second part of this article, we therefore collect the arguments in the literature that suggest that the congruence is not only coincidental but causally related. In particular, the varieties-of-capitalism (VoC) approach has demonstrated that classifications of industrial production regimes are similar to the TWWC clusters. Thus, we have four similar classifications.

In order to come closer to a truly holistic approach to welfare regimes and their impact on the economy, these different typologies need to be connected. We thereby hope to contribute to bringing TWWC nearer to its initial ambition of providing a comprehensive typology of welfare capitalisms.

Within and beyond Esping-Andersen's Worlds of Welfare Capitalism

Academic work on different classifications has mainly been conducted with respect to two areas. First, analyses on welfare services arose as a reaction to the transfer bias of TWWC. Second, the VoC framework filled the void of classifying countries according to the organisation of their market economies.

The sphere within TWWC: cash benefits and welfare services

The initial TWWC-framework actually examined the transfer component of the welfare state only. The decommodification index took into account pension, sickness and unemployment benefits (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 49–50) as did the stratification index. Although Esping-Andersen stressed the important role of education in shaping the class structure, he deliberately confined his attention ‘to the stratification impact of the welfare state's traditional, and still dominant, activity: income maintenance’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 57–8). The public–private mix of social provision was examined with respect to pensions only. By studying the transfer component of the welfare state, Esping-Andersen intended to arrive at general conclusions:

[W]hen we study pensions, for example, our concern is not pensions per se, but the ways in which they elucidate how different nations arrive at their peculiar public–private sector mix. (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 2)

In other words, he did not study welfare transfers because he was especially interested in the programme design in the particular policy fields but in order to understand the general principles underlying the welfare regimes. He took on a holistic approach that looked at the wood instead of the single trees. By this line of reasoning, including all different areas of social policy into his study was dispensable.

However, this exclusive focus on welfare transfers was problematic as it soon emerged that welfare services must be treated differently from the transfer component of the welfare states (Jensen, Reference Jensen2008: 153). Thus, researchers occupied in the field of welfare services got the impression that TWWC did not have much to offer to them. They lamented that ‘Esping-Andersen's theory does not really provide the tools we need for the analysis of other types of relations of subordination and dependence’ (Anttonen and Sipilä, Reference Anttonen and Sipilä1996: 89).

This shortcoming triggered several policy-specific comparative studies in the field of social care (Anttonen and Sipilä, Reference Anttonen and Sipilä1996: 88; Leitner, Reference Leitner2003; Bettio and Plantenga, Reference Bettio and Plantenga2004; Woods, Reference Woods, Koistinen, Mosesdottir and Serrano-Pascual2009), health care (Bambra, Reference Bambra2005; Wendt, Reference Wendt2009) and education (Willemse and de Beer, Reference Willemse and de Beer2012; West and Nikolai, Reference West and Nikolai2013).

The studies led to a range of different cluster structures that have been used in order to confirm or contest the TWWC typology. These inferences are, however, questionable, as they were mostly drawn from policy-specific analyses and are therefore ill-suited to make general statements on a holistic approach. But of course, the more these findings conform to the TWWC typology, the more do they lend weight to the existence of general patterns for welfare transfers and welfare services alike.

The studies employed a variety of different indicators to measure social care services, health care services or welfare services in general, such as expenditure (Kautto, Reference Kautto2002), defamilialisation (Bambra, Reference Bambra2004, Reference Bambra2007), provision levels (Anttonen and Sipilä, Reference Anttonen and Sipilä1996: 93) and welfare sector employment (Stoy, Reference Stoy2014). We do not wish to discuss the pros and cons of the respective indicators, nor do we want to outline the findings individually. At this point, we take a look at the broader picture. The topic has been approached from very different angles, and the various studies have highlighted different aspects of the provision of welfare services. If these studies, with their different foci, revealed similar cluster structures, we could assume with a certain confidence that there are general patterns in place. In order to test this we conducted a social network analysis. On the basis of the different studies that analysed welfare services in their own right and provided cluster structures (Anttonen and Sipilä, Reference Anttonen and Sipilä1996: 93; Kautto, Reference Kautto2002; Leitner, Reference Leitner2003; Bambra, Reference Bambra2004, Reference Bambra2007; Bettio and Plantenga, Reference Bettio and Plantenga2004; Wendt, Reference Wendt2009; Willemse and de Beer, Reference Willemse and de Beer2012; West and Nikolai, Reference West and Nikolai2013; Stoy, Reference Stoy2014), we counted how often two countries were grouped into the same cluster. We visualised the results in Figure 2. It reveals a structure that is almost perfectly consistent with the TWWC typology. As argued elsewhere (Stoy, Reference Stoy2014), there is sufficient and consistent evidence that in general the worlds of welfare services correspond to the worlds of transfers.Footnote 1

Figure 2. Frequency of country pairs being grouped into the same cluster with respect to welfare services

Note: Connecting lines are only depicted for dyads with at least four joint groupings.

Source: Visualization done with Gephi (Bastian et al., Reference Bastian, Heymann and Jacomy2009).

The sphere beyond TWWC: welfare state and the economy

It was one of Esping-Andersen's main objectives in TWWC to analyse welfare states not only as an independent but also as a dependent variable. He saw the ‘welfare state as a principal institution in the construction of different models of post-war capitalism’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 5), and devoted around a third of his book's space to this topic. The interplay between welfare regime and the economy in changing times was also the guiding theme of his 1999 book. In both his works he studied the transition from an industrial to a post-industrial economy in which the service sector has come to replace the manufacturing sector as the economy's mainstay. He argued that the three regime types have taken different trajectories of service-employment growth as the transitions have been directly shaped by the welfare state. The structure of the economy is therefore strongly influenced by the state–market–family nexus.

This focus was the second oversimplification he made in his book. Not only did he speak of welfare states when he only studied welfare transfers, but he also equated the service sector with the economy as a whole. However, the industrial sector still plays an important role in many OECD countries, and has therefore attracted a lot of scholarly attention in recent decades. The VoC framework (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001b) has filled the void of comparing different systems of industrial production that had been deliberately ignored by TWWC. Of course, VoC takes a completely different approach and is therefore not just a stand-in for the gaps in TWWC. But, as we shall demonstrate later, TWWC does have a lot to say about the industrial part of the economy as well, and it would have been a fruitful exercise to incorporate these aspects right from the beginning.

VoC distinguishes two types of capitalism according to the way that the coordination problems of firms are solved. While liberal market economies (LMEs) focus on coordination by the market, coordinated market economies (CMEs) are regulated by networks. These institutional infrastructures cause different comparative institutional advantages that are conducive to different production strategies.

Whereas liberal welfare regimes (such as Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the UK and the United States) are classified as LMEs, social-democratic welfare regimes (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden) as well as conservative welfare regimes (Austria, Belgium, Germany, Netherlands) belong to the CME cluster. On the one hand, this similarity suggests that there might be a causal link between the two approaches. On the other hand, the mismatch between a tripartite TWWC typology and a dichotomy with respect to production regimes raises questions. Apparently, the degree of abstraction of the VoC approach is too high for the research question at hand. There have been some suggestions in the literature for a more nuanced typology. Amable (Reference Amable2003) and Ebbinghaus (Reference Ebbinghaus2006) distinguish five types of capitalism. These more fine-grained approaches shed further light on the different regimes and help to understand the relation between welfare and production regimes.

Towards a comprehensive approach

The ambition in TWWC was to study the influence of the welfare regime on the economy. However, as discussed above, TWWC fell short of this claim and studied the influence on the service sector only. In the course of the VoC debate, links between the welfare state and the industrial sector have been analysed. A good overview of these arguments is provided in the publications by Schröder (Reference Schröder2009, Reference Schröder2013). This debate mainly focuses on the relationship between the transfer component of the welfare state and the structure of the industrial sector. Thus, some inroads have already been made, but we still lack the comprehensive picture that was the aim of TWWC. Therefore, we would like to systematically collect evidence on the links between the four different areas that have been brought forward in the academic debate. By integrating the insights from different analyses, we hope to reveal consistent patterns of interaction in the different regime types.

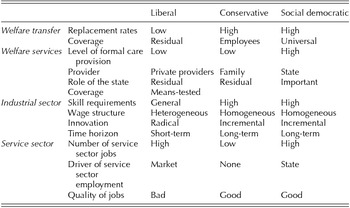

Descriptive overview of the regime characteristics in the four areas

As a first step, we will bring the four different classification systems together in order to provide a comprehensive description of each welfare regime type. We will briefly recapitulate the regime characteristics in the four areas.

As has been argued in TWWC, the liberal welfare state is designed as a mere safety-net and leaves the primary responsibility for the people's wellbeing with the individual. The role of the state is strictly residual and private provision for social risks is expected. Accordingly, reliance on the market is very high for social insurance and social care services alike.

The economy in liberal welfare regimes consists of a liberal market economy in the industrial sector and a large low-wage service sector. The coordination of both sectors is left to the market. Their institutional set-up favours short-term production strategies, based on radical innovation, inegalitarian wage structures and rather general skill requirements. The transition to a post-industrial economy, i.e. an economy dominated by the service sector, has been driven by the market. In the absence of state regulations, the wage differential within the economy was allowed to increase, leading to the creation of many, rather badly paid jobs in the service sector.

The conservative welfare regime is tailored to the needs of (male) workers. Entitlements to welfare programmes must be earned through mandatory contributions to social insurances. Their purpose is to prevent severe wage losses in hard times. The welfare regime is characterised by a strong male breadwinner model, where entitlement to welfare benefits for family members is dependent on the wage-earner. Formal care services are underdeveloped as social care is mainly provided within the family.

The structure of the economy is biased towards the industrial sector as service sector development is not far advanced. As a CME, manufacturing is concentrated in highly productive branches that require long-term investment strategies. Collective wage bargaining ensures a homogeneous wage structure that prohibits poaching of workers between firms.

The social democratic welfare regime is characterised by a strong role for the state. Universal coverage and high replacement rates of tax-financed welfare schemes lead to a high degree of decommodification and redistribution. Formal welfare services are offered by the public sector in order to enable women to participate in the labour market. Accordingly, the service sector is mainly driven by the public sector and its focus on welfare services. It is an important part of the economy, with public employment accounting for a third of total employment by the turn of the millennium (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1999: 153). Direct state influence and strong unions ensure good job quality. The industrial sector conforms to the characteristics of a CME, with its network mode of governance and its focus on manufacturing in highly productive industries.

Making sense of the patterns

The three welfare regime types identified in TWWC are apparently not only distinct with respect to the transfer component of the welfare state, but also with regard to the overall structure of its welfare regime and its economy. However, in order to rule out mere coincidental correspondence, this empirical finding has to be theoretically backed. Only if it is possible to identify a theoretical bracket that holds the different areas together can we confidently assume the existence of general regimes.

The explanations provided by TWWC and VoC are a good starting point for investigating the causal link between the different areas. Both approaches were based on distinct theoretical provisions to capture the differences and similarities in their ‘narrow’ field. Thus, instead of reinventing the wheel, we consider it a fruitful strategy to attempt to apply their theoretical assumptions to the broader picture at hand.

Functionalist explanation (VoC)

The VoC framework takes an institutional perspective. Its understanding of institutional development is mainly functionalist. Institutions are chosen by rational-choice actors because they are expected to provide a more efficient solution/coordination of a given problem. In this vein, the constructive role of employers in expanding the welfare state has been stressed. Whereas the power resources approach depicts companies as being hostile towards welfare state development, Swenson (Reference Swenson1991, Reference Swenson2002) argued that employers are not necessarily opposed it. On the contrary, they actually supported the new policies as they saw them as an instrument to further their comparative institutional advantage (cf. Thelen, Reference Thelen1994; Mares, Reference Mares, Hall and Soskice2001).

As a consequence, a series of rational choices leads to a coherent institutional set-up where the different institutions complement each other. In the VoC literature, these institutional complementarities are seen as the main reason for the success of the system as a whole and for its persistence. Institutions are stabilised by their relations to each other, ruling out radical change.

Table 1 Characteristics of the welfare regimes with respect to the four areas under study

However, the industrial sector of an economy does not operate in a vacuum but is integrated into a wider institutional framework. One way of arguing for coherent welfare regime types across the classifications is to identify institutional complementarities between the different sectors.

Institutional complementarities in the conservative welfare regime

With respect to the link between welfare transfers and the industrial sector, conservative, as well as social democratic, welfare regimes complement their industrial sector with a welfare state that guarantees a high level of decommodification for industrial workers. This link appears to further their comparative institutional advantages. CMEs require workers with firm- and sector-specific skills. However, for individual workers specialisation is an investment that only pays off when they are able to exercise this kind of job permanently. In situations when workers lose their jobs and are forced to take any new job, firm-specific skills are often no longer needed and may even be detrimental. High levels of decommodification minimise this risk as workers are insured against losses of income and status degradation (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001a: 51; Ebbinghaus and Manow, Reference Ebbinghaus, Manow, Ebbinghaus and Manow2001: 1–2; Estevez-Abe et al., Reference Estevez-Abe, Iversen, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Manow, Reference Manow, Ebbinghaus and Manow2001: 157–8; Schröder, Reference Schröder2013: 70–2).

Relations between the actors in CMEs are marked by mutual trust rather than competitive behaviour. Collective wage bargaining prevents the poaching of workers on the basis of wage competition. Publicly provided comprehensive and uniform welfare benefits can help to avoid workers being lured by company-based welfare benefits instead (Schröder, Reference Schröder2013: 68). Furthermore, generous early retirement plans are instruments to reduce the workforce without destroying the required relationship of trust between long-term employees and the companies (Manow, Reference Manow, Ebbinghaus and Manow2001: 159; Schröder, Reference Schröder2013: 81).

Table 2 Joint groupings of welfare regimes into one cluster

However, the welfare transfers are not only crucial for the industrial sector but also for the regime's distinct organisation of welfare services. The high degree of familialism in the conservative welfare regime and the low level of female employment lead to a male breadwinner model. The entire household is dependent on the income situation of the male wage-earner. Accordingly, the wage has to be high enough to sustain a family income and also must be secured in times without employment. Otherwise, if the wage of a single breadwinner did not cover the expenses of the entire family, women would seek employment in order to support the household's income. This would endanger the system of care provision that is traditionally done by housewives, and would furthermore stir up wage competition in the labour market. Thus, the reliance on the family for social care provision in the conservative welfare regime needs to be complemented by a high level of decommodification, strong labour market protection and an economy that is geared towards the provision of good jobs (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1999: 123).

Taken together, the different areas of the welfare regime exert an important influence on the service sector. It is well-known in economic literature that increases in productivity of service sector jobs lag behind those of industrial jobs. As a consequence of this Baumol's disease, productivity in service sector employment is comparatively low. In general, there are two roads to service employment: allowing wages to deteriorate until they express their real market value or creating publicly financed jobs in the service sector (Iversen and Wren, Reference Iversen and Wren1998: 512–13; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf, Ebbinghaus and Manow2001: 276–7).

Both options are ruled out by the characteristics of the conservative welfare regime. The conservative welfare regime is characterised by a high level of decommodification that is required to sustain the industrial sector as well as the provision of social care services within the family. As it is financed to a large extent through payroll taxes, high fixed labour costs crowd out market-driven service sector employment (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen and Esping-Andersen1997: 79; Ebbinghaus and Manow, Reference Ebbinghaus, Manow, Ebbinghaus and Manow2001: 2). Additionally, a high reservation wage renders low paid jobs unattractive. But, due to the high reliance on informal care, there are also no incentives for employment growth led by publicly financed services, either on the supply-side or on the demand-side (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 224; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf, Ebbinghaus and Manow2001: 277–8). This constellation caused high unemployment rates that led to the dictum of ‘welfare states without work’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen and Esping-Andersen1997: 79).

The process of dualisation that can be witnessed in most countries of this regime type (Palier and Thelen, Reference Palier and Thelen2010; Palier, Reference Palier, Natali and Bonoli2012) is a response to this stalemate. As production in the industrial sector requires high levels of decommodification, the traditional welfare institutions are left in place for industrial workers. However, as social security contributions render employment in the service sector cost-prohibitive, employment and welfare provision in the low productivity sector have been liberalised.

Institutional complementarities in the social democratic welfare regime

With respect to the link between welfare transfers and the industrial sector, the social democratic welfare regime is similar to the conservative welfare regime. Both types complement their industrial sector with a welfare state that guarantees a high level of decommodification for industrial workers. However, decommodification in social democratic welfare regimes follows a more individualistic logic. Social benefits are primarily tied to the individual based on their citizenship, rather than to the household. As a consequence of its universal orientation, the state has a great interest in bringing all persons into employment in order to broaden the state's tax base. A universal welfare state with generous benefits cannot be financially sustained with a low employment rate. It also sets high incentives for the individual to work, as high marginal taxes on households force both partners to work to achieve a high standard of living (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 223).

Accordingly, the labour market integration of women was one of the state's objectives. This goal requires the expansion of publicly financed formal care services. On the one hand, defamilialisation is a precondition for the commodification of women. On the other hand, formal welfare services provide important employment opportunities for women (Alestalo et al., Reference Alestalo, Bislev, Furåker and Kolberg1991: 56; Gornick and Jacobs, Reference Gornick and Jacobs1998: 691).

In this regard, the social democratic welfare state acts as an important employer. As high taxes prevent market-driven employment growth in the low paid sector, the service sector in these countries is heavily driven by public welfare services (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 223, Reference Esping-Andersen1999: 153).

Institutional complementarities in the liberal welfare regime

In contrast to CMEs, where industrial workers need a certain level of financial security, the labour market in LMEs must not be distorted by welfare state regulations or welfare benefits. The production strategy of firms requires flexible adaptation to changing labour demands. A lean welfare state with low levels of decommodification and regulations belongs to the economy's comparative institutional advantages. As the economy depends on a labour force with flexible skills, the education system is geared towards general skills. This orientation is supported by the welfare state. Weak employment protection and low welfare transfers render investment in specific skills risky, and hence set incentives for the acquisition of general skills. The lack of job specialisation helps to clear the labour market. As a consequence, generous social protection legislation is less important.

The low level of public welfare benefits sets strong negative work incentives. This pressure to work, in combination with low levies, renders employment in the low- and medium-productive sectors possible. This is true for the industrial as well as the service sector. Hence, in a liberal welfare regime the market-driven development of service sector employment is feasible. In the absence of public service provision, the service sector is marked by many, rather low paid jobs. In consequence, the purchase of welfare services is feasible for many households, enabling the regime's reliance on market-based provision of welfare services.

Political explanation (TWWC)

Functionalist explanations are based on the premise that actors can anticipate the effects of new institutions and foresee their institutional complementarity. Critics have questioned this assumption as these effects cannot reasonably be predicted. Instead of being a product of intentional design, institutional complementarities are the unintended consequences of political decisions (Ebbinghaus, Reference Ebbinghaus2006: 55–6). These decisions result from the different general orientations of the political actors.

In accordance with Esping-Andersen's prior works, TWWC regarded welfare state development as the outcome of the class struggle and political coalition building in democratic societies (Korpi, Reference Korpi1983; Esping-Andersen and Korpi, Reference Esping-Andersen, Korpi and Goldthorpe1984; Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). The classes in a society have different conceptions of the desired social order. It is the class that, through its intermediate organs, has the biggest power resources and controls the commanding heights of the political system that will shape the welfare regime according to its goals. Thus, welfare state development is a highly political process. In TWWC, Esping-Andersen traces the three welfare state regimes to different actor constellations. The social democratic welfare state has been wrought from the capitalist class by the strength of the labour movement (trade unions and social democratic party) in the Scandinavian countries and its ability to form coalitions with the middle class. The conservative welfare state regime is the result of a long period of conservative rule with the backing of the church. These conservative forces succeeded in securing the loyalty of the middle class by setting up status-distinctive social insurances. Liberal welfare state regimes were established in those countries that neither had strong labour movements nor were subject to the influence of the church and there were, therefore, no political forces that tried to push the middle class from the market to the state (Schmid, Reference Schmid2010).

It is not very likely that political actors confined their political ambitions exclusively to the welfare state. Instead, we might expect that they used their power resources to stamp their influence on the structure of the economy as well. Thus, on the basis of the power resources approach we would expect the economies and the welfare regimes to be structured according to the same underlying principles.

The liberal regime type had been mainly shaped by secular, anti-socialist forces. They valued individual freedom and responsibility and did not want these ideals to be curtailed by state paternalism. State influence had to be restricted to an absolute minimum in order not to suppress individual and economic initiatives or distort the incentives set by the markets. This conception underpins the structure of all four areas, welfare regime and economy alike. Coordination is almost exclusively left to market forces, and social inequalities are accepted as a necessary and productive work incentive.

The main goal of political actors in the conservative welfare states of continental Europe had been to preserve the existing social order with respect to economic status and gender differences. This led to a specific configuration of the welfare regime and the economy. Social insurances are an instrument to avoid social deprivation in hard times that lack any redistributive function. Their organisation along sectoral lines ensures a high level of stratification. The strong reliance on the family for care provision and the low level of formal care services conforms to and sustains traditional gender roles. Wage bargaining is conducted in a decentralised and sector-specific fashion, and follows a segmentalist mode of coordination. Solidarity is primarily group-based (Thelen, Reference Thelen2010: 195–6).

In contrast to the conservative model, the social democratic welfare regime attempts to level out class and gender inequalities. The welfare regime and economy are shaped by the labour movement and the social democratic party in accordance with their political goal of an egalitarian society. Universal and tax-financed welfare benefits are used as redistributive instruments that are not directed at the household but at the individual. High levels of formal care services improve the conciliation between employment and family. They enable women to participate in the labour market and become economically independent. Furthermore, the growth of public services was at least partly caused by the desire to create decent jobs in the public sector to cater for rising female participation rates. In consequence, the service sector is dominated by the public sector. Centralised collective bargaining ensures a homogeneous wage structure without high wage differentials and is therefore labelled ‘solidaristic’ (Thelen, Reference Thelen2010: 195–6).

Conclusion

In the twenty-five years since its first publication, TWWC has sparked a lot of research in various areas. Much effort has been devoted to exposing and addressing the shortcomings in the initial publication. In this article, we have reviewed the academic debate and argued that TWWC fell short of the promise of providing a comprehensive picture as it neglected welfare services as well as the industrial sector of the economy. To be fair, TWWC was certainly not meant to be the final word in, but rather a starting point for, a debate on a comprehensive welfare regime typology. In our view, critics have been too preoccupied with attempts to prove Esping-Andersen ‘wrong’, rather than using their findings to improve the TWWC framework. There is overwhelming empirical evidence that Esping-Andersen's typology is a useful heuristic not only with respect to welfare transfers.Footnote 2

In this article, we have collected the evidence brought forward in the academic debate over the last decades with respect to a holistic typology covering the welfare regime and its influence on the economy. The most compelling finding is the high degree of consistency of various classifications that have looked at welfare transfers and welfare services, as well as the industrial or the service sector of the economy.

In a last step, we drew together the theoretical arguments that help us understand why these classifications coincide. We distinguished between a functionalist and a political explanation, which both provide plausible arguments for the existence of holistic welfare regimes. However, the picture is still sketchy and further research on the causal links between the different areas is needed. Linking the different areas of the welfare regime and the economy appears to be a promising research avenue.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Martin Powell, Armando Barrientos and two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful and valuable comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.