“An anxious and frightened nation was waiting, and we were to provide the answers … That sense of urgency made people all around us push themselves to what seemed the limits of their endurance. Eighteen or twenty-hour days were commonplace, with every waking moment devoted to dealing with NACCD demands.”

Robert Shellow, Assistant Deputy Director for Research, National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders Footnote 1

“Public commissions, especially ones appointed in a crisis atmosphere or dealing with emotionally-charged issues, are obviously ill-suited to the careful development and use of good research … I am struck by the fact that, on any given topic that has become a crisis, the amount of extant, policy-relevant, well-done social science research is just about zero.”

James Q. Wilson, Professor, Harvard University Footnote 2

For most of its first fifty years, “The Harvest of American Racism,”Footnote 3 the Kerner Commission staff paper that sought to explain why the rioting of 1967 occurred in some cities (but not in others), seemed to largely be surrounded by controversy and mystery—along with a dose of conspiracy. Written by the Commission’s social scientists, it was supposed to have provided the foundation for the Commission’s final report. However, instead, it was quickly and severely rejected, and everyone associated with it was soon fired. In the histories about the Commission that followed, “Harvest” was typically mentioned with just a few comments about it being “too radical” and that it was not just merely rejected—it was suppressed by the Commission’s senior staff.Footnote 4

Fortunately, in 2018, Steven Gillon’s comprehensive (and excellent) book about the workings of the Kerner CommissionFootnote 5 and a very personal account by four of “Harvest’s” five primary authorsFootnote 6 did much to expand our knowledge about the paper and about what had actually happened. Because of these works, we can now read “Harvest” in its entirety, we know more about the background of this 1967 paper and about who wrote its various sections, and in an important discovery, we now know that the paper’s authors and field researchers were fired, not because of “Harvest,” but because the Commission, despite what the White House had earlier said about it always having sufficient resources to do its job, had suddenly learned that it was going to be given enough funding to stay in existence for just another ninety days and so was having to lay off more than one-half of its total staff.

However, although we now have a far better understanding of “Harvest,” a much larger question remains: Could this entire situation, which according to Gillon, left “a gaping hole in the center of the Commission’s overall report” and “produced a deep split that threatened the future of the Commission itself,”Footnote 7 have been avoided? As much as social science and public policy “need” each other, like many relationships, the one between these two areas is particularly complicated. Social scientist Nathan Caplan suggests that researchers and policy makers live in “separate worlds with different and often conflicting values, different reward systems, and different languages.”Footnote 8 Clearly, such obstacles are formidable, but, for “Harvest,” did they have to be insurmountable?

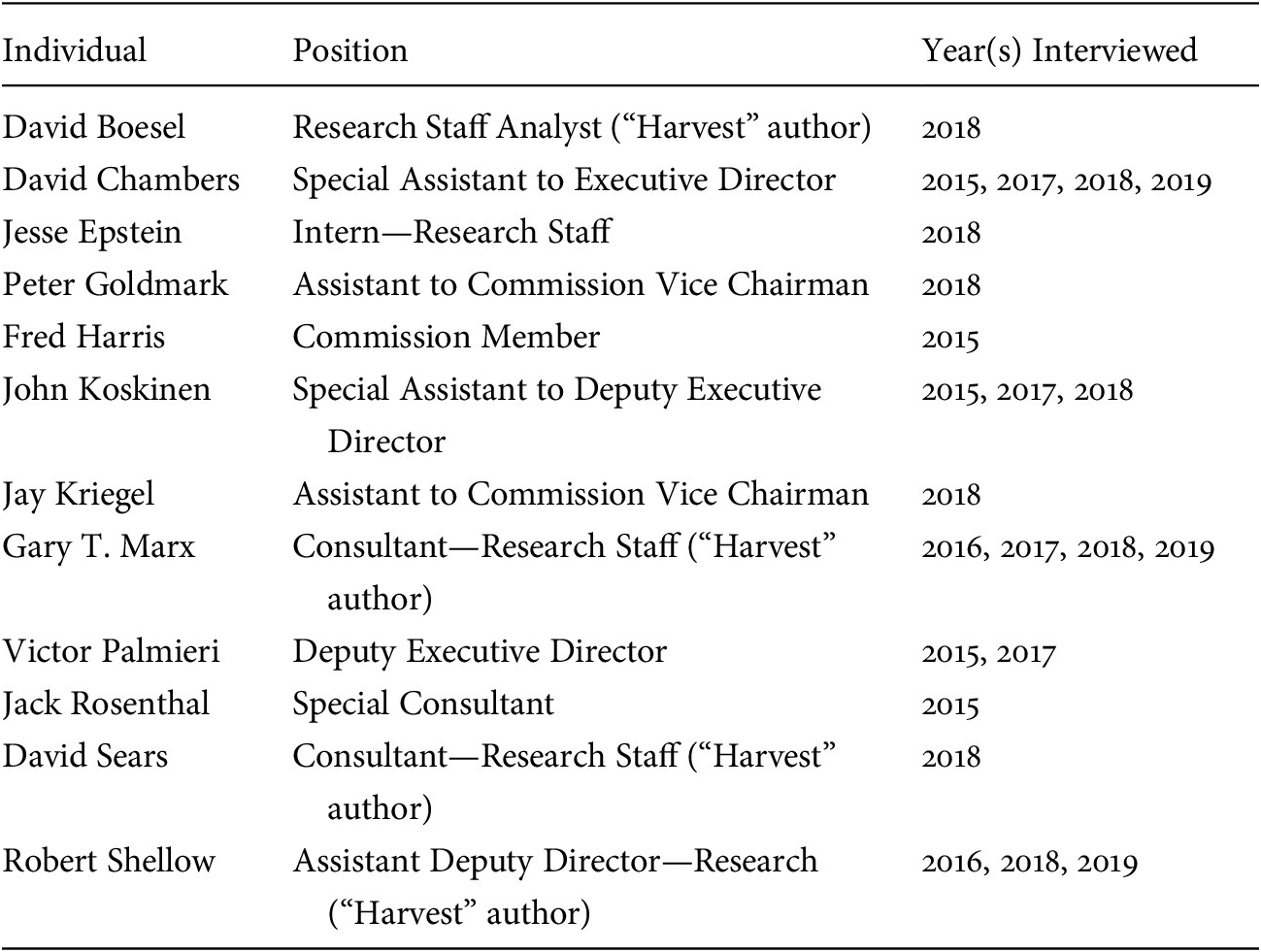

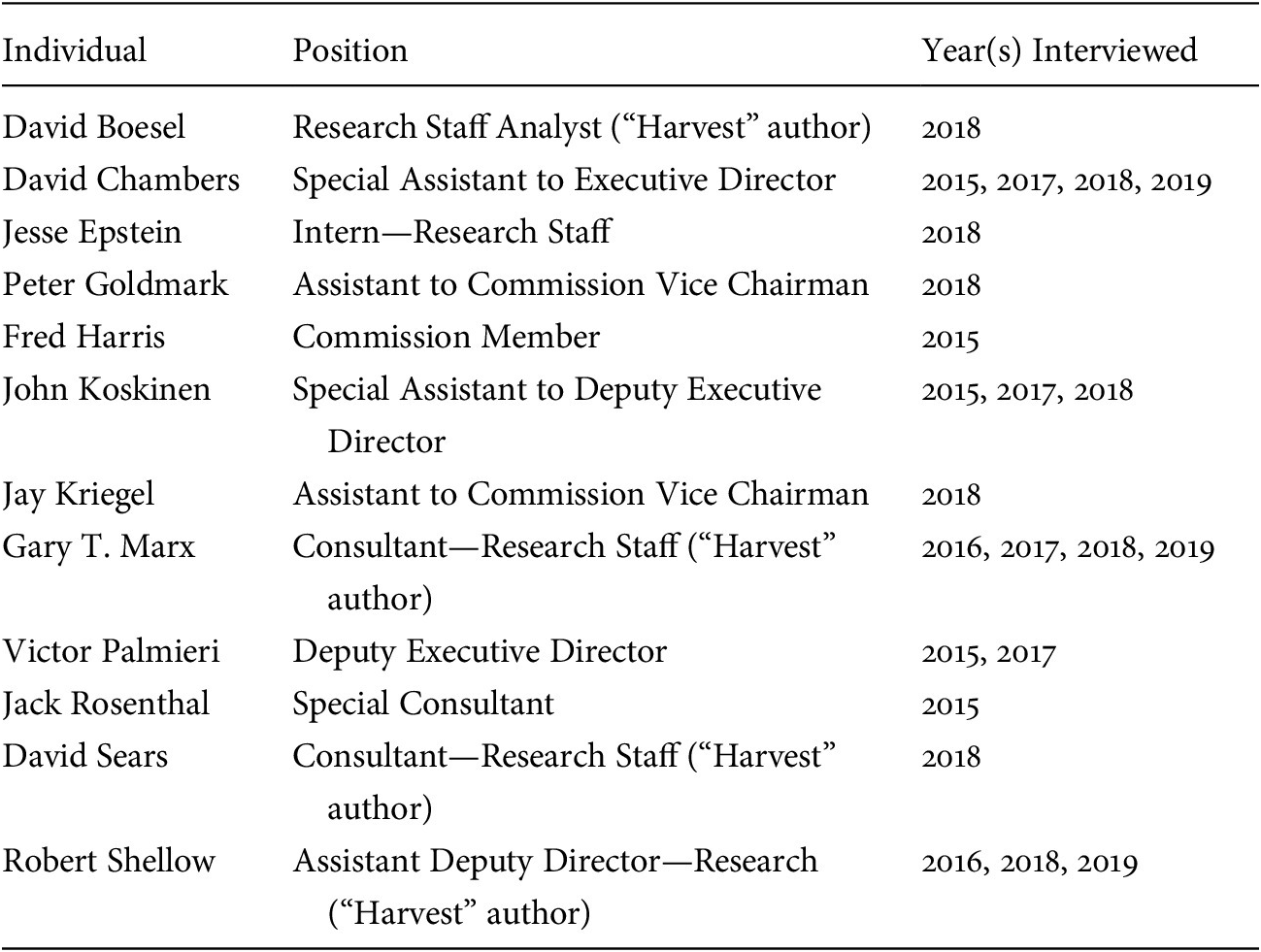

To answer this question, what happened to “Harvest” is examined as a case study that begins with a review of the literature on the challenges of combining social science and public policy. This study then continues with background information on the origin of both the Kerner Commission and “Harvest” and a discussion of what made “Harvest” unacceptable. Next, to determine whether any of the “typical” social science-public policy challenges were present as “Harvest” was being written and reviewed, Gillon’s work and that of the four “Harvest” authors is used, along with material from the Commission’s files, an oral history from the Commission’s executive director, a 2018 conference presentation by the head of the research team that wrote “Harvest,” and interviews conducted by the author over the last several years with key members of the Kerner Commission and its staff (see Table 1 below).

Table 1. Kerner Commission Interviewees

This information is then supplemented with the author’s own thirty-plus-year experience in conducting research for governmental entities and serving on and staffing special committees to determine what influence any complicating factor may have had on “Harvest” as well as determine what, if anything, could have been done to produce a different outcome. In addition, a brief discussion on whether the public policy challenges that confronted “Harvest” and social scientists over fifty years ago continue to exist is included.

Conducting such a case study that will also create a more complete history of “Harvest” is important because the Kerner Commission sought to address the causes of one of the most troubling times in our nation’s history, and the Commission’s final report is regarded as one of the country’s most important works on race.Footnote 9 Allowing us to better understand what decisions pertaining to “Harvest” were (or were not) made will thus enable us to better assess the significance of the Commission and its work. It will also be of benefit to individuals who presently conduct research and participate in the public policy-making process. Knowing, for instance, what missteps or issues befell “Harvest” can perhaps help others in the future avoid and navigate around such problems in their work.

The Social Science and Public Policy Challenges that Confronted “Harvest”

During the 1960s, social science became an indispensable part of the federal government, advising Washington on issues ranging from counterinsurgency policy in southeast AsiaFootnote 10 to the elimination of poverty at home.Footnote 11 Accompanying this use of social science has been an increasing body of articles and reports on the difficulties of incorporating this field with public policy. A review of the literature produced during the 1960s and 1970s discloses a number of issues and characteristics that are generally thought to have caused the complicated dynamic between the world of the researcher and that of the policy maker:Footnote 12

-

• the inherent complexities of rigorous research,

-

• a lack of understanding among policy makers about the social science process,

-

• the difficulty in communicating research results,

-

• a concern that circumstances can lead social scientists “to advocate” rather than “to educate” or “to advise,”

-

• training that social scientists should follow the data no matter where it leads,

-

• a lack of familiarity among social scientists with the political decision-making process,

-

• the need to provide decision makers with “answers,” and

-

• incompatible time schedules.

Many of these factors—like most policy makers lacking a formal background in research methods and the complicated nature of conducting rigorous research—are obviously closely related to one another. As a result, it may not always be easy for policy makers to understand the discipline’s limitations or processes. Complicating matters, add Carol Weiss and James L. Sundquist, is that “researchers are prone to what others call jargon (although for the social scientist, the jargon may be a precise shorthand for complex concepts)”Footnote 13 and that findings “may be quite unintelligible to any lay person, written more in algebra than English, full of gammas and deltas and multiple correlations and regression analyses.”Footnote 14

Adam Yarmolinsky notes that it is not just the policy maker that lacks an understanding of the “other world,” saying “scholars seem to have at least equal difficulty in understanding their opposite numbers in government—and in adapting their work product to the needs of government.”Footnote 15 They thus may be “puzzled if not utterly shocked,” observes Yaron Ezrabi, “when political storms are stirred up” by their findings and communications.Footnote 16

Not being familiar with the public policy process, researchers may not initially be prepared to accommodate the schedule that public policy often requires. As Yarmolinsky points out, “the movement of affairs and the movements of the reflective mind are on different time schedules. Accordingly, the bureaucratic and political pressure of events is probably the greatest obstacle to seeking and receiving scholarly advices … one might almost conclude that by the time government is ready to ask a specific question of scholars, it will not stay for a scholarly answer.”Footnote 17

It is not just the policy maker’s schedule that the researcher might have trouble accommodating; he may also encounter some difficulty providing the type of “answer” that is expected. Policy makers are often looking for what will be a quantifiably clear “answer.” Unfortunately, either because of the nature of the findings or the time constraints involved, they sometimes gets one of two extremes—advocacy (rather than advice grounded in facts) or conclusions that, to the policy maker, are so qualified or inconclusive as to have little value.

Both James Q. WilsonFootnote 18 and Yarmolinsky have commented that because of the pace, pressure, and the nature of the policy-making environment, researchers can sometimes easily “veer” into advocacy. “Public policy problems,” explains Yarmolinsky, “seldom if ever fall neatly within the confines of a single discipline.” This, in turn, can cause a problem for the researcher who is then, to some degree, having to step outside of his discipline, a discipline that usually provides him with “a framework,” an “historical perspective,” and “rigorous procedural standards.” Combined with “the exciting hurly-burly of political decision making” and the pressure to deliver an answer, the researcher may find himself “relax[ing] his guard against implicit biases and unexpressed major premises” and “offer[ing] generalizations” that he would ordinarily not provide if operating exclusively within his own discipline.Footnote 19

The opposite of this occurrence is the research that results in conclusions that are not as definitive as the policy maker desires. As Wilson,Footnote 20 Weiss,Footnote 21 and Michael Lipsky and David OlsonFootnote 22 note, many policy matters do not readily lend themselves to research, and there are often great difficulties in trying to measure what is being studied, controlling other variables, or defining and obtaining an appropriate sample. As a result, researchers are often faced with no choice but to present findings, which, to the policy maker, may seem indecisive or watered-down.

Another source of potential conflict between the social scientist and the public decision maker is that researchers are trained to investigate and present what they believe the data show, regardless of whether the findings are politically difficult. However, although policy makers also generally desire “the truth,” they cannot so readily dismiss political realities, as the job is to facilitate and make decisions in a political environment. Unfortunately, for the researcher, political realities and sensibilities may not always be obvious, and unlike social science that has formulas and generally accepted research methods to help guide work, there are no such comparable tools available for the researcher trying to traverse the political world.

The controversy generated by Daniel P. Moynihan’s 1965 report on African American families demonstrates how difficult avoiding these political trapdoors can be because Moynihan was not just a PhD social scientist; he was also a high-level policy maker (he was Assistant Labor Secretary at the time), and he was well regarded for his insight and writing ability. Yet, his report, despite initial favorable consideration by the White House, soon generated what has been called “one of the angriest and most bitter” debates within the civil rights community.Footnote 23

Concluding that the increasing rate of single-parent Black families was preventing African Americans from escaping a “tangle of Negro pathology,” his report was severely criticized “for blaming the victim,”Footnote 24 for encouraging “a new form of subtle racism,”Footnote 25 and for providing a convenient excuse for civil rights and antipoverty program opponents by attributing some of the persistence of Black poverty to out-of-wedlock births.Footnote 26 So adverse was the reaction to Moynihan’s report that Stephen Hess says it turned Moynihan “into an embarrassment for the national Democratic Party,”Footnote 27 and Yarmolinsky says, it made “any rational consideration of policies in matters related to the subject … impossible for a considerable period.”Footnote 28

Thus, the challenges confronting the social scientist and the policy maker who hope to work together are varied and significant. Sundquist adeptly summarizes the effects of many of these challenges from the perspective of the frustrated policy maker: The researcher is “not quite sure enough or quick enough or not politically wise and sensitive… . Why does every judgment that comes from the research community have to be qualified? Why does every question need more study? Why do researchers never seem to understand the political necessity for sharp and unequivocal policy positions?”Footnote 29

The Origins of the Kerner Commission and “Harvest”

For people who were not alive in 1967, it is very difficult to describe just how terrifying that summer was. Within only a few months, incidents involving some combination of rock-throwing, fire-setting, window-smashing, and looting spread through Black neighborhoods in over 100 cities, from Atlanta to Phoenix, from Milwaukee to New Haven. As alarming as this violence and destruction was, what occurred during the last three weeks of July in Newark and Detroit was even worse.

In Newark, rioting began following rumors that police had beaten a Black cab driver that had been arrested for tailgating a police car. When the rioting ended five days later, state police and the National Guard had expended over 13,000 rounds of ammunition, 250 fires had been set, and twenty-three people had been killed. Property losses totaling more than $10 million (the equivalent today of about $75 million) were incurred.Footnote 30

Less than two weeks after Newark, rioting began in Detroit after police raided a small-time, illegal after-hours club in a Black neighborhood and encountered many more people than anticipated. The rioting that resulted from this incident almost made Newark look insignificant and left portions of Detroit—the nation’s fifth largest city—looking like they had been firebombed during World War II. Only when U.S. paratroopers arrived did the violence begin to subside, and when it finally did, forty-three people had died and over $50 million in property (about $400 million in today’s dollars) had been stolen or destroyed.Footnote 31

With the Detroit riot occurring so soon after Newark, the nation truly seemed to be coming apart, and 71 percent of white America was convinced that a conspiracy was involved.Footnote 32 On July 27, 1967, with smoke still hanging over Detroit, President Lyndon Johnson appointed an eleven-member commission to investigate this wave of destruction and instructed the commission (which was officially named the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, but which came to be called the Kerner Commission, after its chairman, Illinois governor Otto Kerner) to deliver a report within a very short period—one year—that would answer three basic questions:

-

• What happened?

-

• Why did it happen?

-

• What can be done to prevent it from happening again?

Concerning this second question—why the rioting occurred—the Commission hoped that social science would provide the answer.Footnote 33 In fact, only about a month before President Johnson had created the Commission, Theodore White had written that the work of social science had become “the drivewheel” of Johnson’s Great Society.Footnote 34

Leading the team that would seek to answer this key question was Robert Shellow, a three-stripe commander in the Public Health Service. Shellow, who had a PhD in psychology from the University of Michigan and who had been working in the field of juvenile justice and police–community relations, was soon joined by David Boesel and Louis Goldberg, both of whom were PhD candidates (Boesel in political science and Goldberg in sociology); three interns from Antioch College; and Gary Marx, a professor at Harvard University, who was officially a consultant, but who spent a couple of days each week in Washington working alongside Shellow and his staff. Also assisting the group was David Sears, a professor at UCLA, who provided the Commission with the research he had conducted on the participants in the 1965 Watts riot.

This team began its work at the end of September 1967, understanding that its paper would become “the core chapter” of the Commission’s final report.Footnote 35 Said Shellow, “we took one of the President’s charges quite literally, seriously, what caused them [the riots]. Not what happened.”Footnote 36 Gary Marx similarly agrees, saying that their work “was supposed to answer ‘why?’”Footnote 37

Often times not going home to sleep, the team reviewed and analyzed a seemingly infinite supply of data from over 1,200 interviews conducted in twenty riot-affected cities and a study of 13,000 people who had been arrested during the riots. On November 22, 1967 (and 176 typewritten pages later), they provided the Commission’s senior staff a draft of what they had found.Footnote 38

The Problems with “Harvest”

Unfortunately, for the research team, senior staff’s reaction to “Harvest” was immediate and harsh. Reportedly, David Ginsburg, the Commission’s executive director, uncharacteristically swore after he read it. Victor Palmieri, the Commission’s deputy executive director, said that he “fairly threw it across the room.” Nathan Caplan, who had been brought in by Shellow to advise the Commission, said that the paper made him “sick at his stomach” when he read it.Footnote 39

Although the paper did make several important contributions and observations (it identified the factors that influence a disorder and the phases that a riot goes through, and it noted that there was not just one type of riot, but several; that the term “riot” had been misapplied during the year to cover incidents as insignificant as teenagers breaking windows after a dance; and that the typical riot participant was not “riffraff” and thus did not fit the public’s perception of who a rioter was), these benefits quickly became overwhelmed by the paper’s word choice and by a lack of substantiation and explanation. From the very beginning of the paper—in its third paragraph—it implied that some of the rioting may have represented “a general insurrection,” and in the next several pages, terms like “incipient rebellion,” “political confrontation,” and “generalized rebellion” frequently appear to describe incidents. However, as alarming and as important as these terms are, there is never an explanation, for instance, of what turns a “disorder” into a “rebellion.”

“Harvest” also made a large number of assertions—that some groups of Blacks were intent on burning down a whole city, that police act the way that they do because the community wants them to, that Black militancy was widespread, that rioting is not an irrational response, etc.—that potentially have enormous significance. Yet, again, the basis for these statements is not ever explained nor are specific examples given.

The paper’s subtitle, “The Political Meaning of Violence in the Summer of 1967,” offers another clue about what made the paper so troublesome for senior staff. Shellow’s team believed that it had discovered “a political dimension” that existed in a number of disturbances.Footnote 40 These “political” disturbances, wrote the paper’s authors, differed from other disorders because they tended to possess a combination of the following characteristics: they had a focus, they appeared to be rational, they represented a collective purpose, they involved the addressing of prior grievances, and they featured negotiations and meetings that alternated with violence.

The implication of referring to such riots as being “political” was significant, as it could be construed that the riots were perhaps justified. John Koskinen, who was the special assistant to the Commission’s deputy executive director, recognized the consequences of implying that the riots were political, saying that “it is a very big step” to say that the riots “are justified as opposed to saying that they are simply a reaction to racism. You’re beginning to sound like Rap Brown and Stokely Carmichael”Footnote 41 (two Black radicals known at the time for advocating violence as a means of achieving political and economic equality).

Jay Kriegel, who was an assistant to John Lindsay, the Commission’s vice chairman, likewise voiced similar concerns. “I would think it’s pretty clear that you couldn’t say the riots were politically justified,” as the Commission was already about to “push the boundaries” by concluding that discrimination was responsible for the rioting, that the rioters were not riffraff, and that a conspiracy was not involved.Footnote 42 With Kriegel being one of John Lindsay’s closest staff members and with Lindsay being one of the Commission’s most liberal members,Footnote 43 this observation was especially significant because the other commissioners would have been even more resistant to suggesting that the rioting was political.

What also concerned senior staff was that it was not clear how correct this conclusion about the riots being political was. A memo from Charles Nelson, who supervised the field teams that compiled the data for “Harvest,” states, “‘political’ connotes [a] disorder intentionally begun and continued for specific ends. Our data does not support such a connotation.” The memo further notes that many of the factors that “Harvest” cites as being important in creating a political riot also exist in other cities and recommends that “a much deeper and more particularized analysis” be conducted.Footnote 44

In addition, while the “political riot” became the primary theme of “Harvest,” a clear majority of the riots studied for “Harvest,” according to the paper itself, did not possess any political content. Only ten of the twenty riots studied by the research staff possessed such characteristics, with only six of the twenty riots containing “pronounced political content” and another four possessing “some political content.”

Such issues and doubts greatly concerned senior staff. As Ginsburg said in 1988, the paper “seemed superficial, unsupported by the evidence. It was just in a sense a concoction that may be true, but how can a government analysis rest itself on that sort of thing?”Footnote 45 Palmieri, in 2015, said that he, too, had the same concern.Footnote 46

Despite “Harvest’s” unsubstantiated comments and its use of “rebellion,” it is its last chapter (which was primarily written by Louis Goldberg) that many believe ensured the strong rejection that “Harvest” received. Shellow, in retrospect, calls this last chapter “pretty ripe” and “impolitic.”Footnote 47 Marx says it “was radioactive.”Footnote 48 David Boesel, another of the paper’s writers, remembers thinking, after reading it, “Jeez, can we get away with this?”Footnote 49

Extensively filled with rhetoric, this section’s intent was to emphasize the political meaning that the research staff attributed to the rioting and to shock the reader into action. However, in doing so, it moved the paper away from being an academic, objective explanation as to why the riots occurred into what Gary Marx called “an impassioned manifesto”Footnote 50 that warned that a racially inspired revolution was about to occur.

It strongly discouraged the use of a “law and order” strategy to prevent future rioting, saying it could lead to an Algerian-style form of guerilla warfare where people would prefer to “die on their feet” rather than live “on their knees.” It did not believe moderation was the answer either, severely denigrating this course, calling it the product of when whites “cannot make up their minds” and an “impetus for revenge.” Believing that the riots were caused, not by a lack of opportunity, but a lack of power, it said that future rioting could only be averted if “power on real decisions” involving the operation of local poverty programs could be directly transferred “to the young militants in the ghetto.”

Not surprisingly, such conclusions, which seemed to equate rioting with an acceptable form of political action and to legitimize those who were militant, deeply alienated senior staff. “It has always flabbergasted me,” says David Chambers, the special assistant to the Commission’s executive director, how the paper’s authors “could have possibly thought that the last part would have been acceptable.”Footnote 51 , Footnote 52

What Went Wrong?

After having examined the environment in which the Commission was conducting its work, as well as having interviewed the people who were principally involved in the formulation and discussion of “Harvest,” it is apparent that many of the previously identified obstacles—along with several others—confronted this paper. “Harvest” was written under enormous pressure, it represented a research effort that had never before been undertaken on such a scale, and it involved one of the most controversial issues facing the country in decades—characteristics that only exacerbated the usual difficulties of understanding the complexities of social science and the political process, meeting timelines, and providing the type of results that were expected.

What the research team was attempting to do, trying to determine why over 100 cities had disorders while others did not and to do so in only three months, was unparalleled, with Lipsky and Olson saying that the Commission “was asked to do no less than thoroughly analyze the history of American race relations”Footnote 53 (as points of reference, Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma, which examined the nature of race in America, took almost six years to plan, research, write, and publish,Footnote 54 and the commission that New York City mayor Fiorello LaGuardia appointed in 1935 to investigate the causes of just one riot in Harlem took a full year to do its work).Footnote 55

There was also enormous pressure on the Commission’s staff to complete its work. Moynihan said the Commission was created in “an atmosphere of near panic,”Footnote 56 and members of both senior staff and the research staff recall it as being one of the more intense periods of their careers.Footnote 57 For the research team, it was especially so since their work, said David Boesel, was to have become “the interpretative chapter … the guts” of the Commission’s report.Footnote 58 At one point, Shellow said he worked eighteen hours a day for forty-one consecutive days.Footnote 59

The situation confronting the research team thus would have been a challenge for many. Shellow, by his own admission, “had never worked in that kind of an environment. I don’t know how you can prepare for that. I was overwhelmed … the project got away from me.” Not wanting to interfere or hamper the team’s work, he admits that he “edited with a light hand. I was not an expert in these areas. My job was to watch what they were producing and stay out of the way.”Footnote 60 He also encouraged his staff to allow the data to speak for itself and to “let the chips fall where they may.”Footnote 61

Shellow’s style may have worked if he had a veteran staff, but he did not. As Gary Marx, one of Shellow’s staff members, said, we were “very inexperienced”Footnote 62 with “a dash of youthful arrogance.”Footnote 63 Marx, who was the oldest of the primary writers, had just turned twenty-nine as “Harvest” was being written. The other two primary writers—David Boesel and Louis Goldberg—were still in graduate school.

At the same time Shellow was trying to give his staff the freedom to work, Victor Palmieri “was on his case” about getting “Harvest” completed.Footnote 64 David Chambers recognizes that Shellow “was caught between two competing and inconsistent forces”Footnote 65—not wanting to rush his staff that was already spending the night in the office and the need to deliver “Harvest” as soon as was absolutely possible. Unfortunately, this pressure, fatigue, and inexperience caused the research team to submit a draft that clearly was not written in the style that was expected (Commission staff had repeatedly been given instructions about how papers were to be written),Footnote 66 thinking that it was better to submit something then and to revise it later. However, this initial wording was so damagingly controversial that the research team was never given another chance to revise it.

That Shellow’s team chose to submit a paper that was so politically volatile is particularly confusing given Shellow’s role in a late-October briefing before the eleven-member Commission. Prior to this briefing, one of the field teams had conducted a presentation for the Commission on information that had been collected in one city, and according to several sources,Footnote 67 this presentation was “an unmitigated disaster.” Instead of sticking to what could be substantiated, the field staff began offering “emotional conclusions” and “conclusions that seemed more akin to persuasive advocacy than analysis.” Not surprisingly, this presentation greatly distressed the Commission and caused it to question staff’s objectivity.Footnote 68

To overcome this damage, Palmieri asked Shellow to conduct a follow-up briefing. Shellow did so, and by several accounts, his presentation was very successful and did much to restore the Commission’s confidence in staff.Footnote 69 That Shellow, one month later, could not make the connection that what had happened to the earlier briefing that had gone seriously awry could also occur to “Harvest” had serious consequences for “Harvest.”

Several other factors conspired to produce the harsh reaction that “Harvest” received. Senior staff, reports David Chambers, was expecting a paper that could readily be dropped into the Commission’s final report as what was subsequently done with Robert Conot’s work (his description of 1967’s major riots became the first chapter of the final report).Footnote 70 Instead, senior staff received a draft that, from its perspective, was largely useless and that was received at about the same time that the Commission suddenly learned that, because of funding problems, it was only going to have about ninety days to complete its work instead of 240 days. John Koskinen believes that this financial crisis certainly contributed to the harsh reaction that the paper received,Footnote 71 and Chambers says that while “Harvest” may not have completely sent the Commission “back to square one” in its plans, it did “certainly send it back to square two.”Footnote 72

One last factor that potentially complicated the writing of “Harvest” was that, at the end of October, senior staff and the research team were no longer located in the same building. Because the Commission’s operations had outgrown its original office space, senior staff moved to another building a couple of blocks away about one month before “Harvest” was completed. When this occurred, the opportunity for the informal watercooler talk that can often be so helpful in updating one another was reduced at a critical time.

Could the Controversy Have Been Avoided?

In assessing what happened to “Harvest,” while there were factors like the Commission’s financial crisis that were outside the control of either senior staff or the research team, a good part of the controversy was within their control and could have been avoided. That this did not occur, though, is not surprising. There was not just one major issue that led to the paper’s problems; there were several, and many of these were interrelated and were especially intense.

Such circumstances likely contributed to Shellow’s difficulty in managing expectations about what was being produced (even adding a one-page transmittal memo explaining how “unpolished” the paper was, what the sources were for some of its major points, and how much time would be needed to fully complete the paper could have helped offset senior staff’s initial reaction to the paper), in recalling the disastrous October briefing session, in appreciating the importance of senior staff’s writing instructions, or in asking for another week of time so that some footnotes could be added and inflammatory wording could be deleted. They also had to have exacerbated the “typical” communication problems between the researcher and the public policy maker, for if such problems exist on “routine” policy matters, one can only imagine how much more difficult they must have been for something as complex, as intense, and as politically sensitive as what the Commission was trying to address.

It is important to recognize that Ginsburg and Palmieri were not political or administrative neophytes. Ginsburg was the consummate Washington insider and had clerked at the Supreme Court and worked at the SEC, the White House, and the Office of Price Administration.Footnote 73 Palmieri was on leave from the Janss Corporation (the developer of the Sun Valley and Snowmass ski resorts), where he was known for his “considerable management skills” and “his experience in dealing with large and complicated ventures,”Footnote 74 and he had previously been considered for a HUD appointment (perhaps as the new department’s first secretary) by President Johnson. Both Ginsburg and Palmieri would have certainly understood the importance of communication, and under their direction, the Commission did undertake a series of measures to try to ensure that sufficient communication did take place. Staff was reminded about how papers and draft chapters were to be written, Palmieri met regularly with Shelllow,Footnote 75 senior staff periodically stopped by to inquire about the research team’s work,Footnote 76 and Ginsburg provided written updates to the eleven Commissioners on the research’s team’s work.Footnote 77 In many instances, these measures would have been adequate, but for something as complicated as “Harvest,” even with the experience of Ginsburg and Palmieri, this was not the case.

One of the problems that can arise from being involved in a subject that is so complicated and that is not in your area of expertise is that sometimes one simply does not know what one does not know. Compounding this situation is that one also often does not realize that a lack of understanding or communication exists until it is too late. As talented and well regarded as Ginsburg and Palmieri were,Footnote 78 that did not mean that they fully understood all that Shellow may have been telling them about the “Harvest” research or that they knew what follow-up questions to ask.Footnote 79 Gary Marx, for example, believes that Palmieri had “undue faith in social scientists”Footnote 80 and may not have realized “how complicated it [social science research] was.”Footnote 81

Because of this—and the other items competing for the attention of senior staff (they had to run an organization with 200 employees, develop a methodology and schedule for conducting the Commission’s work, search for funding to keep the Commission operating, process and sift through the flood of information that was coming into the office daily, conduct hearings, and brief and develop a consensus among the eleven Commissioners, most of whom did not previously know each other)—one can easily imagine an exchange where Victor Palmieri asks about the status of the “Harvest” research and Shellow tells him that the data are proving to be “very interesting” and that it will be a few more weeks before his team’s analysis is completed. However, while Palmieri leaves this conversation thinking he will soon be getting the basis for “the interpretative chapter” of the Commission’s final report, the paper he receives on November 22, 1967, is actually much different.

In retrospect, Palmieri could have been more clear as to what he wanted and done more to ensure that he was going to receive that (Weiss warns that “if policy makers are unclear about what they expect from research, researchers have to ferret, guess, and improvise”; she also adds that “policy makers who do not know what they want are not likely to recognize it when they get it).Footnote 82 Shellow may have also been correct in saying that while Palmieri may have thought he understood social science research, he “really didn’t have an idea as to how the sausage was made,”Footnote 83 but it was also equally incumbent upon Shellow, as the head of the research group, to make sure that senior staff understood how “Harvest” was being written and how the research staff was interpreting the data.

Further adding to the controversy that arose over “Harvest” was the emotion that surfaced after the paper had been submitted. Shellow reports that the reaction among his staff to the news that “Harvest” had been rejected and that they would not be allowed to revise it “was at first shock, and later bitterness,”Footnote 84 and Gary Marx talks about the “the sense of betrayal” that he said he and the team felt.Footnote 85 Although these reactions are not very dissimilar to Yaron Ezrabi’s earlier observation about what can sometimes occur when researchers who are new to the political process become involved, even David Ginsburg, who was so critical of the paper, acknowledged that Shellow and the research team were “understandably … offended” because they had invested so much time and energy in the effort.Footnote 86

Much of this resentment could have, of course, been dissipated if the research team had been given the opportunity to revise “Harvest.” However, although the research team, as it was writing “Harvest,” had the expectation that it would be able to revise itFootnote 87 (a not unreasonable assumption because the authors of other parts of what became the Commission’s final report were allowed to revise their work), David Chambers says, that at this point, David Ginsburg had lost confidence in the research team. The team had already produced a hugely disappointing paper, and with the Commission just learning that it now had even less time to complete its work, senior staff could not risk hoping that the next draft would be sufficient.Footnote 88 As a result, Ginsburg, says Chambers, “would have had no interest of working further with Shellow or trying to revise ‘Harvest,’” adding that Ginsburg “could be quite dismissive of people who weren’t capable.”Footnote 89 Indeed, in an oral history interview for the Johnson Presidential Library, Ginsburg mentions, when speaking of Shellow and “Harvest,” that “we pushed that man aside” and “dropped the report.”Footnote 90

Not unexpectedly, conversations between senior staff and the research team after the submission of “Harvest” were tense.Footnote 91 Although the research team was not given the opportunity to revise “Harvest,” it was asked to continue participating in the development of the Commission’s final report by helping answer a series of questions that had been posed by President Johnson when he created the Commission. Although the questions addressed many of the same issues that “Harvest” covered (e.g., who rioted, why some disturbances were contained and others were not, etc.) or were closely related to what “Harvest” sought to address (e.g., why one man riots while another living in the same conditions does not), Boesel said the research team “demurred” when asked to undertake this assignment, saying that the one week it would be given would not be long enough.Footnote 92 Unfortunately, such an answer did nothing to restore the relationship with senior staff or dispel the sentiment that social scientists never seem to have enough time.Footnote 93

Finally, one can also speculate whether the entire story might have been different if the Commission had hired someone with more high-profile research experience to lead the “Harvest” effort, and it appears that the Commission initially sought to do just that. The minutes from its first meeting on August 1, 1967, indicate that an inquiry about the availability of Kenneth A. Clark whose research on race and self-perception was cited by the Supreme Court in its landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling had been made,Footnote 94 and it has been reported that other prominent sociologists, like James Coleman, who had conducted a major federal study on the equality of educational opportunities, were approached but that they declined either because the fall semester was about to begin and they had teaching commitments to honor or they were concerned that the Commission’s final report would be “a whitewash.”Footnote 95 However, although Robert Shellow was not the Commission’s first choice to lead its research team, he had been recommended by Arthur Brayfield of the American Psychological AssociationFootnote 96 and he had been interviewed by a group of senior staff and Commission members that included Ginsburg, Palmieri, the Commission’s chairman, and the Commission’s vice chairman.

Also, several “Harvest”-related articles written by Shellow, Goldberg, Marx, and Boesel just a couple of years after their work at the Commission provide an indication of what they were capable of doing with a little more time, less pressure, and a little more experience. In 1968, Goldberg wrote about the types and phases of riots.Footnote 97 In 1969, Marx wrote about the role of the police in either containing a disorder or making it worse,Footnote 98 and Boesel presented a paper on the politicization of the rioting,Footnote 99 and in 1970, Shellow wrote about the challenges of conducting a massive research project in the public arena.Footnote 100 In each instance, the articles are tightly worded, very straightforward, and void of incendiary language—all of which is in marked contrast to “Harvest.”

Has Anything Changed for Social Science and Public Policy Since “Harvest”?

Although people have landed on the moon since “Harvest” was written and the development of laptops, texts, and email have certainly helped combat the type of revision and clarification problems that afflicted “Harvest,” it appears that many of the issues that Robert Shellow and other social scientists faced over fifty years ago continue to remain. Brian Baird, who is both a PhD clinical psychologist and a former U.S. congressman, observed in 2015 that “the vast majority of policymakers are not trained as scientists” and are “likely to have very little knowledge of research design or statistical techniques … likewise, the vast majority of researchers have little to no policymaking experience.”Footnote 101 George Galster noted in 1996 that a “proclivity toward technical jargon” still existed and that it resulted in social scientists “communicating with one another rather than with policy makers.”Footnote 102 In 2017, Simon Attwood similarly discussed the need for effective communication from social scientists that is “compelling” and “clear” and that does not “hide behind the science” with an inordinate number of statistics and equations,Footnote 103 and a 2016 survey of policy makers by Joshua Newman, Adrian Cherney, and Brian W. Head continued to identify the long-standing concern that the differing work schedules for the researcher and the policy maker can impede their ability to work together.Footnote 104

Conclusion

Through this case study review of “Harvest,” we have sought to understand the controversy that came to surround this paper and determine whether any of it could have been avoided. In so doing, we have learned that a great deal of the displeasure with “Harvest” was not atypical and could have been precluded but that it is not surprising that this did not occur.

Reflecting what much of America thought—and what NBC News referred to as the nation’s “worst crisis … since the Civil War”Footnote 105—Commission staff believed that the country was in the middle of a national emergency, and they operated as if on “a war-time footing.”Footnote 106 The time constraints, the pressure that was placed on the Commission, the uncharted territory that it found itself in, the other responsibilities that senior staff had, and the challenges of incorporating different disciplines into one massive project all played a part in such matters as why no one clarified either exactly what was being produced or what was expected, why sufficient follow-up questions weren’t asked, why it was more important to quickly turn the paper in rather than polish it, why deep concern rather than a straightforward narrative found its way into the writing, and why the disastrous October briefing was not recalled.

Such problems are not unusual when one seeks to significantly involve social science in the public policy process. In fact, in many respects, “Harvest” is very representative of the inherent conflicts and issues that one frequently encounters when attempting to successfully combine the two fields, the only difference being that the obstacles for “Harvest” were far more pronounced.

It is also important to recognize that although today’s technology now makes the revision of drafts and the clarification of conversations far easier than in 1967, the dynamics of the public policy process and the potential for many of the problems that affected “Harvest” remain. Miscommunication—or more correctly, the lack of “the right type” of communication—still occurs, even with today’s cellphones. The complicated relationship between social scientists—who are not necessarily experienced with political nuances—and public officials—who usually do not understand correlation coefficients—still exists, and no matter the era, there never seems to be enough time.

“Harvest” was supposed to have explained why the rioting of 1967 occurred. Although it may not have provided the explanation that senior staff was expecting, its story does provide us with important insight into the public policy process. Such knowledge is beneficial to today’s social scientists and public policy practitioners who seek to navigate around many of the same obstacles that challenged “Harvest” more than fifty years ago.