Women are almost universally under-represented in politics. According to the Interparliamentary Union, 77 per cent of the world’s parliamentarians are male, and only two out of 193 parliaments (in Rwanda and Bolivia) comprise at least 50 per cent women.Footnote 1 Although the norm of gender equality has been widely supported in Western societies for decades, this has not translated into gender-equal politics. While there has been a wide range of female governors, prime ministers and party leaders, a large majority of the higher offices and governing positions are still filled by men. Many scholars have examined possible causes of this political under-representation, seeking to understand why men still dominate politics and how we can fix this disadvantage for women. As current-day politicians do not operate in a vacuum but exist in a strongly mediatized political environment in which the media are citizens’ primary source of political information,Footnote 2 any systematic gender bias in the media coverage of politicians is likely to contribute to the under-representation of women in politics.

This article offers an innovative approach to studying gendered media coverage, and contributes to our understanding in at least two ways. First, most research on gender differences in the media coverage of politicians focuses on gender bias resulting from everyday gender stereotypes. However, people do not usually apply everyday gender stereotypes to politicians but instead rely on leadership stereotypes.Footnote 3 While these leadership stereotypes are more specific to the political arena, they are nonetheless gendered. Therefore, we argue that we should look beyond regular gender stereotypes and direct our attention to the media coverage of politicians in terms of their leadership traits: these are the traits that matter most to voters, and are the characteristics of politicians that influence voters’ decisions.Footnote 4

Secondly, research on the media coverage of male and female politicians has been overwhelmingly conducted on the short periods of electoral campaigns,Footnote 5 while we direct our attention to the entire election cycle. We expect any gender bias to be greater during times of routine politics, as there is a stronger focus on the norms of fair and balanced reporting during campaigns,Footnote 6 while partisan conflicts are also stronger in election campaigns.Footnote 7 Studying all political periods instead of focusing on campaigns is important, as voters’ perceptions of politicians are largely based on media coverage during times of routine politics, and many voters decide which party to vote for long before the start of the election campaign.Footnote 8

How does gendered media coverage in terms of leadership traits come about? We argue that journalists apply gendered leadership stereotypes in their reporting on politicians (as opposed to everyday gender stereotypes). Thus when journalists are writing about a male politician, the male leadership stereotype becomes activated, including the leadership traits of political craftsmanship and vigorousness; the female leadership stereotype is activated when they write about female politicians, and this stereotype does not contain any of the traits voters desire in their leaders. Following this logic, we hypothesize that male politicians are described more often in terms of the leadership traits of political craftsmanship and vigorousness, and we expect no gender bias in media reports on the traits of integrity, communicative skills and consistency.

To test these expectations, we conduct a computer-aided content analysis of all national newspapers in the Netherlands from 2006 to 2012, covering over 200,000 articles during both routine periods and the campaign periods for three national parliamentary elections. Contrary to Hayes and Lawless,Footnote 9 we find gender differences in the media’s evaluations of leadership traits. These results are consistent with the overall masculinity of the leadership stereotype,Footnote 10 while the male and female leadership stereotypes explain most of the variation in gender bias between leadership traits. Contrary to our expectation, there is little evidence to suggest that gender differences are stronger in times of routine politics than during campaigns. As the Netherlands has comparatively average to high levels of female political participation and support for gender equality, we expect these results to hold in a wide range of countries.

The article proceeds by reviewing the existing literature on leader effects and on gender and leadership stereotypes, after which we arrive at the expectation that based on the male and female leader stereotypes, male politicians will be discussed more frequently in terms of specific leadership traits in media coverage, especially between elections. Subsequently, we describe the data, methods and case of the Netherlands. Thereafter, we present the empirical results for party leaders, the robustness tests for cabinet ministers and an alternative level of aggregation of the media data. We conclude with a discussion of the results, their implications and some ideas for future research on this topic.

LEADERSHIP TRAITS AND GENDER STEREOTYPES

Party leaders are the spokespersons of political parties, and actively try to persuade voters to vote for the party they represent. Not surprisingly, party leaders are electorally important: numerous studies demonstrate that voters’ perceptions of party leaders affect party support. More specifically, we know that the subjective evaluation of a leader’s personality traits influences voters when they cast their ballot.Footnote 11

However, what exactly about a leader’s personality sways voters? Research on leader effects has sought to answer this question by examining which trait evaluations affect vote decisions. In his seminal work, Kinder focused on four traits: competence, leadership, integrity and empathy.Footnote 12 Others have conceptualized only two leader traits, competence and character,Footnote 13 or three traits, for example, Funk,Footnote 14 who studied leadership effectiveness, integrity and empathy. Finally, some studies include more than four traits, for instance, Miller, Wattenberg and Malanchuk,Footnote 15 who study competence, integrity, reliability, charisma and personal traits; Bass,Footnote 16 who includes intelligence, self-confidence, dominance, sociability, achievement drive and energy; and Simonton,Footnote 17 who formulated fourteen character dimensions. Although there are common denominators in these conceptualizations, a widely accepted framework of leader character traits is lacking.Footnote 18

Based on a large-scale literature review, Aaldering and VliegenthartFootnote 19 provide a conceptualization of five leadership traits that integrates existing research on leadership characteristics. The advantage of this conceptualization is that it, on the one hand, comprehensively captures the different perspectives in the field while being sufficiently extensive to differentiate between separate character dimensions and, on the other hand, is sufficiently parsimonious to be used in empirical studies. They distinguish five leadership traits. First, political craftsmanship captures the skills necessary within the political arena, including a politician’s general knowledge, knowledge on specific issues, and political intelligence, including competence, insightfulness, strategic behavior, anticipation and experience. Secondly, they include politicians’ vigorousness, capturing the ‘strength’ of their leadership, their (self-)confidence and decisiveness and whether they dominate the decision-making process. Thirdly, integrity refers to a politician’s intrinsic motivation. It captures whether a politician is honest, guided by the needs of the electorate and uncorrupted. Fourthly, politicians’ communicative skills capture both inspiring or visionary leadership and the mediagenic qualities of politicians, including whether a politician comes across as empathic, charming, friendly and relaxed. Fifthly, leaders’ consistency captures the stability across the visions and actions of party leaders and whether the politician behaves in a predictable manner.

Because voters rarely meet politicians in real life, perceptions of party leaders likely originate in the media’s portrayal of them.Footnote 20 Indeed, research shows that media coverage of party leaders’ personality traits has a non-negligible electoral impact.Footnote 21 As the media portrayal of party leaders affects their electoral success, systematic differences in how male and female politicians’ leadership traits are covered may help explain female under-representation in politics. This gendered media coverage of politicians can be expected, as research into stereotypes shows that leadership is associated with masculinity. Koenig et al.,Footnote 22 for instance, conducted a meta-analysis of over 200 studies on the associative link between gender and leadership stereotypes from three different research paradigms. According to the three paradigms, leaders are seen as similar to men, but different from women; leaders are seen as more agentic than communal; and leaders are seen as more masculine than feminine.Footnote 23

GENDER AND TRAITS IN THE MEDIA

What does the extant scholarly work tell us about how the media cover male and female politicians? Very few studies of gender differences in media coverage consider leadership characteristics per se; most examine other aspects of coverage. We only know of three studies to date that specifically examine gendered coverage of leadership traits. Bystrom, Robertson and Banwart compared the ‘images’ of leaders conveyed in the media coverage of senatorial and gubernatorial primaries, some of which can be considered leader traits – honesty, competence and toughness.Footnote 24 They find, surprisingly, that male candidates are portrayed more often as honest and women more often as tough, although the latter difference is not statistically significant. Semetko and Boomgaarden compare reporting on the two main candidates for chancellor in the 2005 German election, considering the traits energetic, likable, winning type, problem solving competency, leadership strength and media competency.Footnote 25 Though not strictly testing for significance, they find that Angela Merkel scored lower on all characterizations except problem-solving competence. Finally, Hayes and LawlessFootnote 26 inspect media discussion on the KinderFootnote 27 leadership traits of competence, leadership, integrity and empathy in the campaigns for the 2010 US House of Representatives, and find that female candidates are mentioned equally often in terms of these traits as their male counterparts.Footnote 28

Much more routinely than leadership traits, scholars compare coverage of traits derived from gender stereotypes, thus reviewing whether journalists use stereotypically male and female traits when reporting on politicians.Footnote 29 In these studies, ‘strong leadership’ is often included as part of the male stereotype, but not analyzed separately. Traits such as tough, independent, competitive, ambitious, objective, unemotional, aggressive, strong leader, assertive, knowledgeable, effective and sometimes untrustworthy or dishonest are considered ‘male’, while the designated ‘female’ traits include passive, dependent, non-competitive, gentle, weak leader, emotional, compassionate, kind, honest, warm, attractive, honest, altruistic and sometimes unintelligent or uninformed.Footnote 30 In Australia, Canada and the United States, Kittilson and Fridkin find the clearest support for gender stereotype-consistent coverage of congressional candidates.Footnote 31 Atkeson and Krebs likewise find more media discussion of male traits in male-only mayoral races in the United States, as opposed to mixed-gender races.Footnote 32 KahnFootnote 33 observes the stereotypical pattern only for senatorial candidates but not gubernatorial, while MeeksFootnote 34 finds that female politicians are described more by male and female traits in the media. All in all, the findings regarding gender bias in the media reporting of politicians based on everyday gender stereotypes are mixed.

This article’s main argument is that we need to look beyond regular gender stereotypes and direct our attention to the media coverage of politicians in terms of their leadership stereotypes: the leadership traits isolated by the electoral research literature are those that matter most to voters. As such, in electoral terms, they are the most obviously consequential aspects of media coverage to consider. Moreover, theories of stereotype subtypes and subgroups give reason to suspect that people do not apply regular gender stereotypes to politicians, but rely on stereotypes specific to the political domain. As there are gender differences in these stereotypes as well, gendered leadership stereotypes should be the focus of study.

Schneider and BosFootnote 35 expressly compare the content of ordinary gender stereotypes to gendered political leadership stereotypes. They hypothesize that the ‘female politician’ stereotype is a subtype of the overall female stereotype, while the ‘male politician’ stereotype is a subgroup of the male stereotype. A subtype is characterized as a new category with its own unique stereotypical characteristics,Footnote 36 while a subgroup shares many characteristics with the larger stereotype category. Such gendered subtyping is also found in other areas of study: the stereotypes of male managers and males show strong overlap and include many of the same traits, while female managers are seen as different from the overall female stereotype.Footnote 37 In addition, they distinguish between ideal leader traits and the traits voters believe leaders actually have. The five leadership traits discussed above form the prescriptive dimension of political leadership: leaders ought to have these five characteristics. However, the traits that voters believe leaders do possess (that is, the descriptive dimension of political leadership) are quite divergent: voters do not believe or expect political leaders to fulfill their prescriptive leader ideal.

Schneider and Bos’ results confirm their expectations: the stereotypical traits people ascribe to women do not overlap with the traits they assign to female politicians, while the male stereotype and the male politician stereotype largely coincide.Footnote 38 Thus the female leadership stereotype is a subtype of the overall female stereotype, while the male leadership stereotype is a subgroup of the male stereotype. In addition, they show that the stereotype of politicians, in general, includes political craftsmanship and vigorousness,Footnote 39 while the other leadership traits are excluded from the descriptive dimension. Thus only two out of five desired leadership traits are actually associated with political leadership.

More specifically, while people associate women with integrity and related characteristics such as honesty and decency, they do not think female politicians typically score high on integrity.Footnote 40 Communicative skills are likewise linked to women but not to female politicians.Footnote 41 The desired leadership traits of political craftsmanship and vigorousness are part of neither the overall female nor the female politician stereotype. The stereotype of male politicians, by contrast, does coincide with both the general male stereotype and the general politician stereotype: both men in general and male politicians are stereotypically thought to have the traits of political craftsmanship and vigorousness.

The question arises as to whether these gender differences in subtyping are also reflected in the public debate. It is quite likely that they are, as journalists presumably stereotype in the same way as other people. This should result in systematically divergent media coverage for male and female politicians. Thus when journalists are confronted with a politician they want to write about, they are also likely to be influenced by gender leadership stereotypes. Therefore we expect different leadership traits to be associated with male and female politicians. When the politician is male, the male leadership stereotype becomes activated (these traits largely resemble the male stereotype and the general stereotype for leaders), including the traits political craftsmanship and vigorous but not integrity, communicative skills or consistency. When the politician is female, the female leadership stereotype is activated, which is ‘nebulous and lacks clarity’,Footnote 42 does not overlap with the female stereotype or the general leadership stereotype, and contains none of the prescriptive leadership traits.

The activation of a stereotype makes it easier to apply the corresponding traits in describing politicians.Footnote 43 Therefore, we expect the following about the coverage of the leadership traits of male and female politicians:Footnote 44

Hypothesis 1: Male politicians are discussed more often in terms of the leadership traits ‘political craftsmanship’ and ‘vigorousness’ than female politicians.

Hypothesis 2: Male and female politicians are discussed equally often in terms of the leadership traits ‘integrity’ and ‘communicative skills’.

As the literature lacks any indication that the leadership trait of consistency is more strongly associated with the male or female (leadership) stereotype, we expect no differences in how male and female politicians are described in terms of this non-gendered leadership trait:

Hypothesis 3: Male and female politicians are discussed equally often in terms of the leadership trait ‘consistency’.

ROUTINE TIMES AND CAMPAIGN PERIODS

The most important and recent existing research on gender differences in the media coverage of politicians in terms of leadership traits is a study by Hayes and Lawless.Footnote 45 In their work, they investigate how male and female candidates for the US House of Representatives are covered in local newspapers in the month preceding the elections; they show no effect of gender on a candidate’s visibility in the media or in the amount of trait coverage. Additionally, they find that male and female politicians are described equally in terms of their competence, leadership, integrity and empathy. Thus, in contrast to our expectations, they show no gender effect for candidates’ character trait evaluations in news reports.

However, Hayes and Lawless study media coverage only during campaign periods, while we believe that gender bias in media coverage is relatively muted during campaigns and more pronounced during periods of routine politics. There are at least two reasons for this expectation. First, during election periods, the media are more focused on the journalistic norms of fairness and balanced reporting.Footnote 46 In some countries, there are even formal or semi-formal regulations to ensure fair and balanced coverage,Footnote 47 which means that attention is devoted fairly across competing parties.Footnote 48 However, in most countries, the intensified public scrutiny in the short run-up to election day leads journalists to be more careful about any biases in their reports,Footnote 49 so in other words, the fairness norm extends beyond the division of attention over parties. Indeed, in a study on Belgium, Van Aelst and De Swert found that during campaign periods, reporting was not only more balanced in general but also significantly more gender equal regarding the visibility of individual politicians.Footnote 50

Secondly, in addition to bringing the news norm of balanced reporting more to the fore, election campaigns also heighten the salience of conflict between parties. As Hayes and Lawless describe, partisan conflict is the prevailing theme structuring news stories, diminishing the relevance of the candidates’ gender.Footnote 51 By contrast, during routine political times, political conflict has a less determinative role. In addition, the media follow (rather than set) the political agenda during campaign periods, whereas during routine times, the media form a more independent influence on politics.Footnote 52 In their own campaign communication, female politicians largely highlight the same character traits as men,Footnote 53 or even stress agentic traits like leadership more to counteract existing gender associations.Footnote 54 Thus, as the media largely follow what politicians do during a campaign, campaign reporting should be less influenced by gender bias.

It is important to know whether gender differences in coverage are exacerbated between election periods, as many voters in parliamentary systems decide which party to vote for long before the election campaign starts.Footnote 55 In addition to directly affecting vote decisions, the portrayal of politicians during routine politics is highly likely to contribute to the subjective perceptions we have of politicians. Therefore, focusing only on campaign periods disregards a long and influential period during which media coverage is likely to strongly affect voters. This leads to our fourth expectation:

Hypothesis 4: The gender bias in media coverage in terms of the traits ‘political craftsmanship’ and ‘vigorousness’ is stronger during campaign periods than during times of routine politics.

THE DUTCH CASE

Most research on gendered media coverage of politicians is conducted in the United States, while much remains unknown about the differences in media portrayals in European countries. The American context evolves from a primarily candidate-centered political environmentFootnote 56 to a more party-centered arena, in which politics is ideologically more polarized and partisan cues are increasingly influential. According to Hayes and Lawless,Footnote 57 this development results in a diminishing role for gender stereotypes in politics. In Europe, where politics has always been much more party-centered, no such development is taking place; thus the possible influence of gender on politics is smaller than in the United States. In addition, a politician’s role differs substantially across regime types: leaders’ influence on voters, for instance, is (still) larger in the US presidential system than in European countries, which mostly have parliamentary systems.Footnote 58 Hence, examining political news coverage in the Dutch context instead of the United States is a conservative test of gendered media reporting.

Among Western European countries, the Netherlands can be considered a typical case for finding gender-based political leadership coverage. The Netherlands can be characterized as placing a relatively high value on tolerance of minorities or deprived groups, it has a Protestant cultural heritage, and it scores high on the survival/self-expression divide,Footnote 59 all of which should contribute to the active participation of females in the political process. Moreover, the norm of gender equality is widely supported in Dutch society. Yet this does not translate into completely gender-neutral practices. The Netherlands is steadily ranked in the top 20 per cent on gender equality in politics in the Global Gender Gap reportsFootnote 60 for the years included in the article and in the top 12 per cent on gender equality in the economy, health, education and politics combined.Footnote 61 Therefore, it performs at an average level compared to the rest of Europe. Although the Netherlands has never had a female prime minister, female politicians are relatively common in the Dutch context, especially in local politics and in the national parliament. Thus stereotypes are expected to affect the coverage of these women to a lesser degree than in countries where female politicians are less common.

DATA AND METHODS

To test our hypotheses empirically, this article studies the discussion of leadership traits of party leaders in newspapers and tests the findings’ robustness on newspaper coverage of cabinet ministers. We study the period from 1 September 2006 to 12 September 2012, which allows us to examine the three campaign periods for the national elections on 22 November 2006, 9 June 2010 and 12 September 2012. To compare the results of this study with the research of Hayes and Lawless in a meaningful manner,Footnote 62 we define the campaign period as the four weeks prior to election day, while all other weeks are considered to be periods of routine politics.Footnote 63 For the entire research period, a large-scale computerized content analysis was conducted on the political news coverage of newspapers. All newspaper articles in Dutch national newspapers that refer to a party leader or a cabinet minister were collected through the digital archive LexisNexis and included in our analysis, yielding over 200,000 newspaper articles. All twelve Dutch daily national newspapers are included in the analysis: Volkskrant, Telegraaf, NRC Handelsblad, NRC Next, Algemeen Dagblad, Trouw, Parool, Financieele Dagblad and the free newspapers Spits, Metro, Pers and DAG.

To assess whether politicians are discussed in terms of their political craftsmanship, vigorousness, integrity, communicative skills and consistency in the media coverage, we rely on a measurement instrument developed by Aaldering and Vliegenthart:Footnote 64 an automated content analysis of leadership traits based on the dictionary approach. For each of the five traits, two dictionaries exist: one that taps into positive images for this trait and one that taps into negative images. A total of ten leadership images for each politician were included in this study. The dictionaries search for words and word combinations that measure the appearance of the images in the newspaper articles, including the negation of the absence of that image. For instance, newspaper articles were captured that include a reference to a party leader combined with one of the phrases that reflect a positive image on the leadership trait vigorousness, such as decisiveness or firmness but also ‘not indecisive’ and ‘not weak’. Appendix 1 presents some of the most important search terms for each political leadership image, although the actual dictionaries are much more comprehensive.

The occurrences of the leadership images are coded as a proportion of the total number of references to the party leader per week, that is, the measurement of the images in the media are relative to leader visibility. The content analysis was split into two phases. First, we selected articles in which politicians are mentioned, sampled using their last name. To exclude misfits, however, we customized each search term with name-specific attributes. For instance, for politicians with a very popular Dutch name, we also included their first name, the name of their party or their political function. In a second step, we used the dictionaries of the leadership images on this subset of political news articles; this process combines a reference to the politician’s last name in close proximity to words or phrases from one of the search strings developed by Aaldering and Vliegenthart.Footnote 65

The validity of the automated content analysis was extensively examined and, among other tests, cross-validated with a manually coded content analysis of over 4,000 newspaper articles. Aaldering and Vliegenthart show that the measurement instrument of leadership images in newspapers performs well and produces valid results, with an average standardized Lotus coefficient of 0.67 and a percentage agreement of 93 per cent between the automated and the manually coded content analyses.Footnote 66 In total, we found 694,933 unique mentions of party leaders and cabinet ministers in 202,631 newspaper articles and 57,126 unique evaluations (positive and negative) of the ten leadership images.

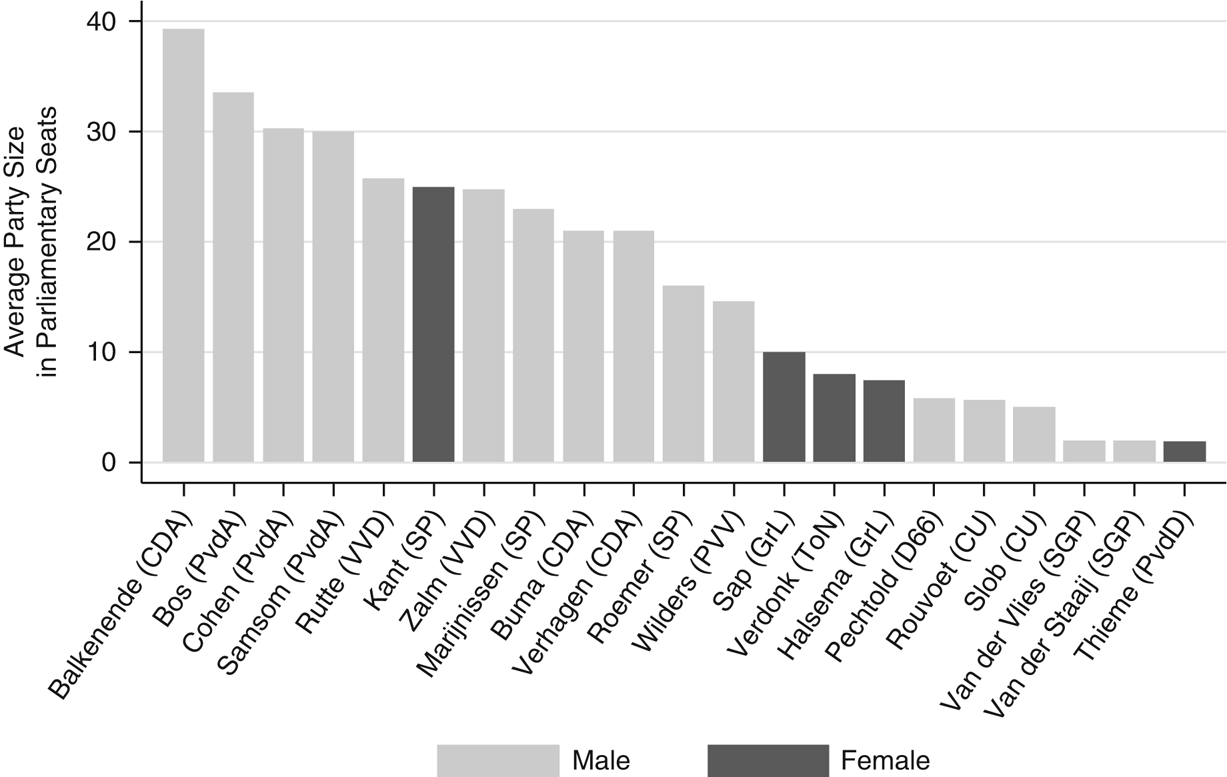

Party leaders are operationalized as the top candidate on the party list during campaign periods, as the chairperson of the parliamentary group of opposition parties during routine periods and as the chairperson of the party in parliament or the (prime-) minister for government parties during routine periods. All leaders of political parties that obtained at least one elected seat in parliament during the study period are included,Footnote 67 resulting in twenty-one party leaders of eleven political parties. Figure 1 shows that there were five female party leaders and sixteen male party leaders in the study period. The largest parties (the PvdA, the CDA and the VVD – the Labor Party, the Christian Democrats and the Liberals, respectively) were represented by male party leaders, while the female party leaders led small or medium-sized parties. The average party size for male party leaders is 18.56 seats in parliament, while the average party size for their female counterparts is only 7.74 seats. As argued by Bennett,Footnote 68 journalists ‘index’ news sources on their power and give priority to more powerful and more politically relevant actors. As a consequence, journalists might consider the leaders of large parties – who are male – more newsworthy because of the relationship between power and party size, and might give them more extensive trait coverage. To remedy this potential bias, we control for party size in all analyses on party leaders. In addition, some politicians were both party leader and cabinet minister during the time period under study. When these functions overlap in time, we included these politicians in the analyses with the party leaders and excluded them from the robustness analyses on ministers. The models for party leaders include a dichotomous variable that measures whether a leader is also a minister to control for these double functions.

Fig. 1 Average party size in parliamentary seats, by party leader

We conduct our analyses on weekly data, in which the dependent variable is the percentage of articles referring to the politician that also evaluates him/her by the specific leadership trait. Because we inspect five traits, we estimate five models using OLS regression analyses with panel-corrected standard errors clustered on individual politicians. Furthermore, since there are only twenty-one party leaders in our dataset, of which only five are female, there is a reasonable risk that individual leaders are driving the results. To prevent this possibility, we jackknifed all models on party leaders, excluding each party leader for one analysis and correcting the standard errors based on these twenty-one separate analyses. Finally, since we use weekly data, following the recommendations of Beck and Katz,Footnote 69 we inspect the temporal dependence in the dependent variable prior to adding the independent variables and add lagged dependent variables to our models when necessary.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

To test whether male party leaders are more often described in terms of their leadership traits than their female colleagues, five analyses are conducted and presented in Table 1. As the table shows, male party leaders are described significantly more often using three out of the five leadership traits than their female colleagues. First, male party leaders are discussed more often in terms of their political craftsmanship than female party leaders. The predicted probabilities based on these models (not shown here) indicate that in 4.54 per cent of the newspaper articles that mention a male party leader, his political craftsmanship is discussed, compared to 3.01 per cent of the newspaper articles that mention a female party leader. Secondly, a gender effect is found for the leadership trait vigorousness, as male party leaders are evaluated on this trait in 5.95 per cent of the articles in which they are mentioned and women in 4.52 per cent of the articles, all else being equal. Thirdly, male party leaders are more often discussed in terms of their communicative skills than female leaders, in 4.92 per cent of the articles in which they are mentioned, while the communicative skills of female party leaders are discussed in 3.79 per cent of the articles. By contrast, male and female party leaders are discussed equally often in terms of their integrity and consistency, as these differences are small and not statistically significant.

Table 1 Gender Effects in Trait Coverage on Party Leaders

Note: OLS models with panel-corrected standard errors in parentheses, clustered on individual politicians and jackknifed on leader. The dependent variable is the percentage of the references to the party leader that also includes a reference to the leadership trait by week. Source: LexisNexis. †p<0.10, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Overall, these results support Hypotheses 1 and 3 and show that political news coverage has a gender bias such that male politicians are more often described in terms of their political craftsmanship and vigorousness, while no gender bias is found in reporting on a leader’s consistency. Hypothesis 2 is supported insofar as it concerns the lack of a gender bias in reporting on politicians’ integrity, but the results reveal that male party leaders are more often discussed in terms of their communicative skills than female party leaders, contrary to our expectation.

Is the bias equally strong for positive and negative evaluations? To provide a more in-depth insight into the differences in coverage between male and female politicians, Table 2 presents the gender effects in trait coverage for positive and negative leadership images separately. For positive trait discussions, we see a pattern that is very similar to the one in the combined positive and negative trait assessments. Male leaders are more often discussed in a positive manner regarding their political craftsmanship, vigorousness and communicative skills than female party leaders, although the differences in vigorousness and communicative skills are only significant at the 0.10 level (two-tailed). As with the overall trait coverage, the media pay equal attention to male and female party leaders’ positive traits of integrity and consistency. The results regarding the negative discussions on leadership traits show that although male party leaders are mentioned more often with these negative images (as all coefficients for gender are negative), the differences tend to be smaller than they are for the positive traits, and fewer are statistically significant. Female party leaders are less often described in negative terms regarding their political craftsmanship and vigorousness, although the difference for political craftsmanship is only significant at the 0.10 level.

Table 2 Gender Effects in Trait Coverage on Party Leaders – Positive and Negative Images

Note: OLS models with panel-corrected standard errors in parentheses, clustered on individual politicians and jackknifed on leader. The dependent variable is the average percentage of the references to the party leader that also includes a reference to the leadership trait by week. Source: LexisNexis. † p<0.10, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

In summary, male party leaders receive more reporting on their leadership traits than female leaders, which is mostly due to positive coverage of their political craftsmanship, vigorousness and communicative skills and some negative press regarding their political craftsmanship and vigorousness. These results seem to indicate that, as expected, there is a gender bias in political reporting on leadership traits associated with male political leaders, while contrary to our expectation, male leaders are also more often mentioned in relation to one trait that is not stereotypically linked to male leaders – positive communicative skills.

Our fourth hypothesis states that gender differences in the coverage of politicians are stronger during times of routine politics than during campaign periods. In the run-up to elections, journalists are extremely conscious of the norm of fair reporting and aim to avoid any semblance of bias. In addition, during routine periods, the media agenda is mainly influenced by the political agenda, while partisan conflict governs news reporting, making it less likely that other differences come to the fore. The hypothesis is formally tested by estimating the interaction effect between the gender of the politician and a dummy for campaign periods, which is shown in Table 3. For all traits, the interaction effect is not significant, meaning that the effect of the gender of the party leader on his or her coverage is not significantly different during routine and campaign times, and therefore we must reject Hypothesis 4.

Table 3 Gender Effects in Trait Coverage on Party Leaders – Routine and Campaign Periods

Note: OLS models with panel-corrected standard errors in parentheses, clustered on individual politicians and jackknifed on leader. The dependent variable is the average percentage of the references to the party leader that also includes a reference to the leadership trait by week. Source: LexisNexis. † p<0.10, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

In Figure 2, we further inspect what occurs in routine times and campaign periods by displaying the marginal effects of gender on the media discussion of leadership traits separately for both periods. The figure displays the coefficient for gender, where a negative coefficient indicates less reporting of this trait in the articles discussing female party leaders. The upper half of the figure shows that during routine political times, female party leaders are discussed less often in terms of political craftsmanship, vigorousness and communicative skills (p≤0.05). These results for routine times mirror those presented above for the entire period, which is unsurprising since routine politics constitutes by far the largest share of time. By contrast, the lower half of Figure 2 shows the effects of the party leader’s gender on media coverage only in the month preceding the elections of 2006, 2010 and 2012. Although the effect is negative for most traits, none of the differences are significant at the traditional level of 0.05, and only the difference in communicative skills is significant at the 0.10 level. In other words, had we conducted these analyses only on media data from the month of campaigning preceding the elections, we would have come to a completely different conclusion. Looking solely at the campaign data comprising the three election campaigns, gender does not significantly affect the depiction of party leaders’ traits, whereas looking at the routine periods, it does. These results are in line with the findings of Hayes and Lawless,Footnote 70 which found no gender differences in leadership trait coverage during an election campaign.

Fig. 2 Gender effects in trait coverage on party leaders – routine and campaign periods Note: predicted marginal effects based on OLS models with panel-corrected standard errors, clustered on and jackknifed by party leader. See full model in Table 3. The dependent variable is the percentage of the references to the party leader referring to the leadership trait by week. Source: LexisNexis.

ROBUSTNESS ANALYSES

To test the sensitivity of these findings to the specific features of our models, we perform two additional robustness tests. First, we replicate our analysis on a second set of political actors: cabinet ministers. Female cabinet ministers are less of a rarity than female party leaders, and thus we enlarge the pool of female politicians. These politicians are well known and receive much media attention, but usually do not actively participate in election campaigns. Therefore, the results based on the media coverage of cabinet ministers in terms of their leadership traits are a conceptual replication of the analyses for party leaders in routine times. Appendix 2 discusses the operationalization and the included control variables, and Appendix 3 presents the full results of the analyses for ministers. The male ministers of these three cabinets were more extensively covered on all leadership traits, but only two of the differences are statistically significant in our jackknifed and clustered analyses. Similar to male party leaders, male ministers are discussed more in terms of their vigorousness than their female colleagues, but unlike party leaders, they are not discussed significantly more often in terms of their political craftsmanship. Of the three traits for which we expected no gender effects, integrity does show a gender difference, with male cabinet ministers receiving more attention for this trait, although the difference is only significant at the 0.10 level. In all, there appears to be a tendency to give fuller coverage to the leadership traits of male cabinet ministers than to those of female ministers, but this result is less clear for the specific traits that we argued are part of the male politician stereotype.

Secondly, as statistical significance is related to the number of observations, the differences in effects between routine periods and campaign periods shown in Figure 2 may be explained by differences in statistical power. To test whether low power is the reason we find no significant gender bias during election campaigns, we additionally performed the analyses based on the non-aggregated level of newspaper articles (n=180,187). The disadvantage of these analyses is that the time dependency is not accounted for. Appendix 4 presents these models, which confirm the main results that female party leaders are less often discussed in terms of their political craftsmanship, vigorousness and communicative skills during times of routine politics. However, in these analyses, the gender differences also hold during the electoral campaigns. In line with the main analyses, and contrary to our Hypothesis 4, the moderation effects between the leader’s gender and campaign periods are not significant. Thus, while the habit in existing research of restricting analyses to campaigns might cause gender bias to remain invisible due to a lower number of observations, there is little evidence to suggest that gender bias is actually stronger during routine politics than it is during campaigns.

CONCLUSION

This article studies whether male and female politicians are systematically covered differently in the media. Based on the male and female leader stereotypes,Footnote 71 we expected to find that male politicians are discussed more often in terms of their leadership traits of political craftsmanship and vigorousness (Hypothesis 1), while no gender bias was expected in the coverage of the traits integrity (Hypothesis 2), communicative skills (Hypothesis 2), or consistency (Hypothesis 3). In addition, we hypothesized that the gender differences in media coverage would be especially prevalent during routine times and less so during campaign periods (Hypothesis 4), as in the latter periods journalists are more conscious of the norm of fair reporting and are almost exclusively focused on partisan conflict. We tested these hypotheses based on a large-scale automated content analysis of all Dutch national newspapers during the period from September 2006 to September 2012.

We indeed find evidence of gender-differentiated coverage. Hypothesis 1, that male politicians receive more coverage on the traits political craftsmanship and vigorousness, holds fully for party leaders and partly for cabinet ministers: male ministers are discussed more for their vigorousness but not for their political craftsmanship. Hypothesis 2 stated that as neither male nor female politicians are stereotypically associated with integrity or communicative skills, newspaper coverage would be equally comprehensive regarding these traits for male and female politicians. Yet in half the cases, male politicians also score higher on coverage of these traits in the media: the communicative skills of male party leaders are more often discussed than those of female party leaders, while the integrity of male ministers receives more media attention than the integrity of female ministers (although only significant at the 0.10 level). Hypothesis 3 concerned the trait ‘consistency’, for which we expected equal coverage of male and female politicians, and indeed, differences in the coverage of the consistency trait were not found for either party leaders or cabinet ministers.

In summary, the results show that men are more often discussed in terms of the leadership traits that are strongly linked to male politicians, political craftsmanship and vigorousness. However, male politicians are also more extensively evaluated on some of the other leadership traits, contrary to expectations. Therefore, we conclude that the overall masculinity of the leadership stereotypeFootnote 72 ensures an occasional advantage on all leadership traits, even though the male and female leader stereotypesFootnote 73 explain most of the variation in gender bias between leadership traits. In addition, this article shows that the greater media attention given to the leadership traits of male party leaders is not because male politicians are discussed more critically than their female colleagues are. Gender differences are found in media reporting on politicians for both positive and negative traits, although the differences are most pronounced in the analyses with positive traits.

Previous studies have almost exclusively examined political news coverage during election campaigns, and we hypothesized that gender differences would be greater during periods of routine politics. This expectation was not supported by the data: we found no greater gender bias in reporting during routine periods. Nonetheless, we see compelling reasons for the field to continue to examine the portrayal of male and female politicians outside of election periods. First, had we limited our scope to election campaigns, we would have concluded that gender bias in political news coverage is non-existent,Footnote 74 likely due to a smaller number of observations. Secondly, the focus of the wider field of political communication on short campaign periods is becoming questionable, given that large parts of the electorate make their ultimate voting decision during times of routine politics.Footnote 75 At the same time, we have a limited understanding of how the dynamics of political media coverage during campaigns compare to the dynamics during routine times. Studying gendered coverage during the entire election cycle can thus contribute to a better comprehension of media influences on political decision making.

The gender-differentiated coverage of the leadership traits of politicians is likely to contribute to the continued under-representation of women in politics in at least two ways. First, media consumers are much more often exposed to males being connected to leadership traits, which perpetuates existing associations between leadership and masculinity. The persistence of a masculine leadership stereotype likely dampens women’s political ambitionFootnote 76 and conceivably strengthens parties’ hesitance to appoint females to top political positions. Secondly, as trait coverage is generally more positive than negative, the more evaluative news coverage for male politicians puts female politicians at an electoral disadvantage. Media profiles are of the utmost importance for the electoral fortunes of candidates in modern democracies: prior research shows that positive leader evaluations in the minds of voters increase support for the leader’s party, while negative evaluations have the opposite effect.Footnote 77 Moreover, the tone of the media portrayals of politicians is shown to be electorally influential.Footnote 78 Thus the tendency to under-represent leadership images of female politicians in the media is very likely to affect public opinion to their detriment, implying a considerable electoral disadvantage for female politicians.

This article is based on a study in the Netherlands from 2006 to 2012, although we expect these conclusions to hold in a wide range of countries for various reasons. First, although the masculine connotation of leadership has not been sufficiently studied comparatively across nations, it has been consistently found in many nations independently.Footnote 79 In particular, in English-speaking countries, there is overwhelming evidence of the male association with leadership. It is therefore likely that the mechanism proposed here holds in these countries as well. Secondly, the Netherlands is highly party centered instead of leader centered. Since politics, particularly in the United States, but also in the United Kingdom, is more personalized than in the Netherlands, the electoral consequences of favorable leadership presentation are likely to be even greater in these candidate-centered countries. Thirdly, even though the norm of gender equality is widely supported in Dutch society, there are still fewer female than male politicians in the national legislature. The Netherlands, however, performs at an average level on gender equality in politics compared to the rest of Europe, implying that in about half of the European countries, the gender gap in political functions is even more disadvantageous for females. As the strength of the association between political leadership and masculinity in journalists’ minds is likely to depend on the relative number of females in political functions, we expect gender bias in media reporting to be even stronger in countries with even fewer female politicians.

The hypotheses of this article are derived from an assumed process of stereotyping by journalists and news editors. However, there is a second interesting possible explanation for the findings to consider. Are the differences in media coverage driven by female politicians behaving differently in the media and toward media personnel? This is particularly relevant, as the male association with leadership potentially puts female politicians in a double bind, where both displaying and not displaying traditional leadership traits could be disadvantageous. What strategies do female politicians choose in the face of this double bind, and which ones pay off? Future research should unravel the exact role of politicians and journalists in the unequal media portrayal of male and female politicians based on their leadership traits.