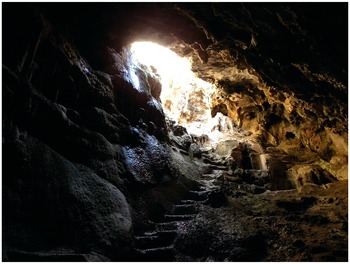

Pan, the goat god child of Hermes, is a nimble musician, playing his syrinx as he jumps and leaps across the craggy mountainside, at least according to the Homeric Hymn to Pan. However, among the Greek gods associated with music and dance, Pan is not an immediately obvious figure to include. He appeared late to the Athenian pantheon, having apparently arrived from Arcadia within the broader context of the Persian Wars in the early fifth century bce and, according to Herodotos, for this reason he seems to have been initially associated with torch races and sacrifices.1 However, by the end of the fifth and beginning of the fourth century in Attica, Pan came to be depicted and described predominantly as a capable musician. He not only is described in the Homeric hymn as piping a tune in the rural countryside for the Nymphs who accompany him (5–18),2 but in Athens there seems to have been considerable and deliberate effort put toward depicting Pan as a musician. It is especially on the series of late Classical Attic votive reliefs, as we see on an example discovered in a cave at Eleusis (Fig. 1.1),3 where we see Pan represented as a musician who actively plays his pipes while the Nymphs dance beside him.4 As a corpus, these reliefs were deposited in cave shrines located in the Athenian chōra, the polis’ surrounding territory, and may be dated fairly precisely since they were mostly excavated from closed contexts. Even more, their original place of display within the caves is often known, so that in many cases, the evidence allows for a preliminary reconstruction of the appearance of the cave sanctuaries together with the rituals that were once performed within them. As a result, the votive reliefs on which Pan is depicted as a musician can be collectively positioned within clearly defined ritual spaces, so that both the images and the cave sanctuaries situate Pan’s music within a particular mode of experience that was potentially open to ancient worshippers.

1.1. Votive relief depicting Pan and the Nymphs, from a cave of Pan in Eleusis, white marble, 28 × 35 cm, 325–300 bce.

The relief from Eleusis, as is typical for the corpus, focuses entirely upon Pan’s musical performance and the Nymphs’ corresponding choral dance. Three female figures take up most of the available visual space; although it is often difficult to identify groups of mythical or divine female dancers, the figures should be understood as Nymphs, given their association with Pan and the frequent presence of dedications to the Nymphs in the majority of the caves in which the reliefs were discovered.5 On this relief, the figures grasp tightly onto their companions’ robes and move together across the visual field, their drapery floating out behind them. Pan strides forward in front of the Nymphs, separated from his companions by the large, rectilinear stone altar. He holds in his hands an extremely large syrinx, roughly the size of the god’s torso.6 The size and nature of his instrument hint at the type of music that the god plays, so that the visual prominence the instrument holds within the image suggests a corresponding acoustic dominance. As viewers, then, we are invited to imagine a loud musical sound emerging from Pan’s pipes, which then fills the space, enveloping the three Nymphs. The four figures, bound together in their collective experience of music and corresponding bodily response, move as a unit throughout the cave in which they reside. The Nymphs’ restrained movements, heavy clothing, and downturned gazes suggest that they perform for themselves and for Pan, dancing to the sounds of the pipes that have filled their cave. They nevertheless have an attentive audience: nestled throughout the cave walls are Pan’s goats and sheep, and along the left side sits the protome, or mask, of Acheloös the river god. Although the animals and the god do not participate in the Nymphs’ dance, their rhythmic placement on the rocky frame that encloses the central performance nonetheless retains a sense of movement and chorality.7

We may see a similar conception of Pan as musician advanced in Euripides’ Ion, where, with evocative language, in lines 492–502, the tragedian paints for his audience a vivid picture of a divine celebration, as the chorus of Creusa’s servants sing that:

Here, in a dark cave, nestled into the slopes of the Acropolis, the haunting sound rises from Pan’s piping to accompany the young girls’ dance that takes place just outside. The ode teases and entices its listeners, painting an aural picture of the brilliant grass outside Athena’s temple, the clear sounds of the god’s pipes, the dark, mysterious recesses of Pan’s cave, and the beautiful sight of the young girls’ dance. The use of αἰόλος in line 499 goes even further in creating this image, since the adjective elusively evokes both visual and acoustic qualities with respect to Pan’s music.9 The ode thus asks of its audience that they imagine a sound that shimmers as it emerges from Pan’s pipes, perhaps a high-pitched song, easily flitting about from note to note under the masterful hands of the goat god. Indeed, at every turn, the tragedian invokes and involves the audience’s senses, absorbing them in the scene through his description of lush, green grass (στάδιον χλοερόν), or the dark cave in which Pan resides (ἀνήλιον ἄντρον). Euripides’ description of the mythical music and dance, fittingly, constitutes part of the choral ode in his tragedy, so that a visual doubling occurred before the audience who watched the chorus sing and dance on stage, while at the same time the chorus performed the mythical music and dance of the ode. Human and divine music and choral dance blend together in this theatrical context, so that the audience at once witnessed the performance of a tragedy and gained a privileged vision of the mythical revel that could occur on the other side of the Acropolis.10

In both the votive relief from Eleusis and the tragic choral ode, Pan and his female companions are presented as musician and dancer, each interacting with the others through his or her movements. In depicting divine music and the danced response to it, the votive reliefs in particular offer us the opportunity to situate Pan’s visual music and the Nymphs’ danced response within the ancient contexts in which they would have once been encountered and within the ritual practices that once occurred around them. In this chapter, then, I consider divine music together with the visual effect the reliefs may have had on the worshippers who once saw these scenes within the Nymphs’ sacred caves. Even more, I explore how ancient viewers may have interacted with the reliefs when they encountered them in the immersive, evocative context of the cave shrines. Such an emphasis on the gods’ music and dance and the subsequent effect their performance could have had upon their viewers is suggested, above all, by the images themselves. If we return to the relief from Eleusis, we can say with certainty that the Nymphs’ dance stands out as a captivating and striking element of the composition, capturing the viewer’s attention as the three female divinities move elegantly across the visual field. And indeed, the Nymphs’ dance, which takes up the majority of the visual field, hints at the profound response they have to Pan’s music, which fills the space of the cave with the sounds of the syrinx. The Nymphs’ bodily response to the sounds of Pan’s music, therefore, acts as one of the primary ways by which we can access the presence and effect of divine music on its listening audience. To draw out compositional elements that hint at the visualized presence of Pan’s music and the Nymphs’ response, throughout this chapter I focus on the reliefs’ particular mode of representing Pan’s music-making and the Nymphs’ danced response, as well as the images’ overall composition; such an approach also allows for an exploration of the relationship between image and context, and between divine musician and mortal audience.11 By looking both within and outside each votive relief, I argue that when these images were encountered within the cave shrines sacred to Pan and the Nymphs, the reliefs invited their worshippers to have a fully embodied, multisensory experience of divine music and dance.

Music in Stone

The Homeric Hymn to Pan presents a particularly Athenian persona of the goat god, one where he is associated with the Nymphs, for whom he plays his pipes while they dance.12 The hymn, which was probably composed in the first half of the fifth century bce,13 takes place in a wild, rural setting where Pan roams about the wooded fields and mountainous hills, accompanied by the dancing Nymphs (2–3).14 As each day draws to a close, Pan returns from tending to his sheep and plays “sweet music,” μοῦσαν νήδυμον (15–16), with his syrinx. Pan’s music echoes across the landscape while the Nymphs accompany him with their song, so that, together, Nymphs and god dance to their collective performance.15 A later Hellenistic hymn from Epidauros also conceives of Pan as the musical and dance companion of the Nymphs. In this evocative song, Pan is described as the “star of the dance-floor,” χρυσέων χορῶν ἄγα[λ]μα (3), and the “prince of popular music,” χωτίλας [ἄ]νακτ[α μ]οίσα<ς> (4), who may “coax heavenly notes from his sweet-sounding pipes,” εὐθρόου σύριγγος εὐ[θὺς] | ἔνθεον σε[ι]ρῆνα χεύει (5–6).16 Moreover, the hymn posits that Pan also acts as the leader of the Nymphs, or νυμφαγέτης (1), suggesting that it is he who guides the Nymphs in their dance. Together, they provide musical entertainment for the gods.

Pan is similarly shown playing his pipes while the Nymphs dance on Attic votive reliefs. Despite the consistency with which he performs on his instrument across the corpus, the compositional placement of the divine musician within each relief is surprisingly varied. While the Nymphs generally dance in the center of the image, Pan may instead be found in numerous positions, moving from left to right, top to bottom, inside the image to superimposed on the frame. His ever-changing location thus suggests that the god was thought to be capable of moving freely throughout his cave, jumping nimbly from one rocky perch to another, much like we hear in the Homeric hymn. Given the moveability of his performance, the location from which Pan’s music emanates has a correspondingly different visual effect on the composition of the scene and the viewer’s encounter with the object.

When the god is included within the main scene, Pan often sits on the extreme side of the relief (e.g. Fig. 1.7), where he acts much as the musicians in an orchestra do when they accompany a modern opera or ballet, in that he contributes the music that provides the rhythmic foundation for the performance but does so from the periphery. Pan may also occasionally participate in the Nymphs’ dance, as we saw on the relief from Eleusis (Fig. 1.1).17 Here, Pan acts as the nymphagetēs, much like he is described in the hymn from Epidauros, as he leads the Nymphs in their dance, moving with them across the floor of the cave while he plays his instrument. The composition of the relief draws further attention to the importance Pan and his music hold for this scene: not only does Pan play a singularly impressive syrinx, which suggests a correspondingly large and expansive sound, but the god is also the only standing figure on the left side of the altar, so that the viewer’s attention is immediately drawn toward his performance. As he plays his pipes, he moves to its music, his chlamys billowing out behind him. The curving lines of his legs are echoed by the undulating rock frame, almost as if to suggest that the music that emanates from him fills the space of the cave and the surrounding landscape.

Pan’s movements are not restricted to the main visual field, however, and he may also leave the scene altogether to occupy a position on the relief’s frame. On a triangular relief discovered in the Vari Cave (Fig. 1.2), Pan perches cross-legged upon the stylized cave frame while he holds his syrinx to his mouth.18 Depicted frontally, he sits at the apex of the triangular relief that invokes the shape of Mount Hymettos, into which the Vari Cave descends. Sheep and goats populate this rocky landscape, drawing a visual connection with the actual mountainous and cave landscapes in which ancient viewers would have found themselves. The curvilinear border of the relief rises up in a broad arc at the top of the votive, as if to suggest that Pan himself has forced the rock of the relief to move outwards to create space for his body. Even when Pan is depicted outside of the central scene, nestled on his hilltop at a distance from the dancing Nymphs, their beautifully moving bodies nevertheless make clear to the viewer that they both hear and respond to the god’s music.

1.2. Votive relief depicting Pan and the Nymphs, from the cave to the Nymphs (Vari Cave) on Mount Hymettos, probably Hymettian marble, 68 (including tenon) × 70 cm, 320–300 bce.

Such moveability in the rendition of Pan’s body is common across the corpus of reliefs. In depicting the god in many possible locations throughout the image and its frame, each image plays with and tests its own borders, pushing back on the limitations of the relief sculpture to communicate something distinct about the representation and cult of Pan, and his relationship with the Nymphs.19 The specific mode of representing Pan and his music as crossing boundaries is thus a consistent and perplexing feature of the reliefs: although he may occupy many positions on the frame, in each he interacts with the main visual scene in a distinct way. For instance, on two reliefs discovered in the cave to Pan and the Nymphs on Mount Parnes (Figs. 1.3 and 1.4),20 Pan appears at the top left corner of the frame. Yet, even though his position with respect to the rest of the relief is similar in both of these images, his appearance differs greatly between the two. On the first, a relief dedicated by Telephanes (Fig. 1.3), Pan sits cross-legged and is depicted frontally so that he stares at the viewer while lifting his pipes to his mouth to play the instrument. Conversely, on the second relief (Fig. 1.4), Pan is shown in profile as he perches among the rocks and peers down at the rest of the image; the god also holds his syrinx and, despite some damage to the relief, the Nymphs’ dance suggests that he too plays it here. Pan can even intrude into reliefs dedicated to other gods, such as on a relief to Kybele, where the goat god is shown halfway up the naiskos frame, seemingly suspended mid-air, playing his pipes (Fig. 1.5). Such organizational and representational freedom for the figure of Pan within the corpus of votive reliefs suggests, through a visual medium, a prevailing conception of the god as being able to appear spontaneously to his worshippers and to unsuspecting individuals, taking them by surprise much in the same manner as do the goats who roam the rocky faces of mountains.21

1.3. Votive relief dedicated to Pan and the Nymphs by Telephanes, from the cave of Pan on Mount Parnes, white marble, 43 × 47 cm, 310–290 bce.

1.4. Votive relief depicting Pan and the Nymphs, dedicated by Aristokles, Polystratos, Phaulos, Pausias, Diopeithes, Theotimos, Stratos, Archias, Pytheas, Phaidon, Eucharides, Aristonikos, Pythodoros, Thrasyllos, Kallisthenides, from the cave of Pan on Mount Parnes, white marble, 52 × 82 cm, 330–320 bce.

1.5. Votive relief dedicated to Kybele, found near the Enneakrounos fountain, Athens, Hymettan marble, 45 × 27 cm, late fourth century bce.

Pan’s short stature and changeable position across the reliefs enhance our interaction with his music and the Nymphs’ dance. First, with the majority of the reliefs, the viewer’s eye is immediately drawn to the large and imposing Nymphs. It is only after we recognize that the Nymphs dance that we must also search for Pan, the source of the music, in order to make sense of the image. Second, Pan’s inconsistent position from image to image, moving throughout the main visual plane and the frame, has the potential to have a profound effect upon the viewer: each time we come across a relief dedicated to the Nymphs, we must look anew to find the inspiration for the Nymphs’ movements. In other words, we must deliberately seek out Pan and his music in each image. Moreover, if we were to consider the reliefs broadly in their original cave setting, for the ancient worshipper, who also stood in a cave and looked up at reliefs, the effect is such that Pan almost seems able to appear anywhere in the undulating masses of rocks, the deep stalagmites, and the hundreds of tiny crevices of the cave’s walls. By encouraging the viewer to imagine that Pan moves throughout the cave shrine in this way, the votive reliefs could manipulate the viewer’s senses: by showing that Pan and his music could be present at multiple times and in multiple places, each image suggests the possibility that Pan and his music might invade the space of the cave and surround the worshippers.

Sculpted Dance

In attributing such transformative power to Pan’s music, his performance on the votive reliefs and its effect upon the dancing Nymphs takes on added significance. As with Pan’s music-making, the Nymphs’ dance is consistently depicted on the fourth-century votive reliefs, on which they hold hands or their companions’ mantles and move forwards together as a unified group, their drapery swirling around their feet and flowing out behind them. For instance, the triangular relief from the Vari Cave (Fig. 1.2) offers us a clear example of how the Nymphs exhibit features of choral dance: the figures move forward together in unison, holding each other’s hands, their steps carefully coordinated. As they move together, the Nymphs’ drapery falls in similar folds across their bodies, sweeping diagonally down around their outstretched legs and trailing out behind them. This particular mode of representation is typical within the Greek visual vocabulary for indicating that the figures are engaged in choreia.22 The gesture of Nymphs holding hands during a choral dance is not restricted to the visual material, and it also appears, for instance, in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, where the “lovely-haired Graces and the cheerful Horai, and Harmonia, Hebe, and Zeus’ daughter Aphrodite, dance, holding each other’s wrist” (194–96).23 Within Greek mythology, the Nymphs are often characterized as chorus dancers. The Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite introduces dancing Nymphs when Aphrodite narrates her abduction by Hermes, stressing that just beforehand, she was in the forest where “nymphs and marriageable maidens,” νύμφαι καὶ παρθένοι ἀλφεσίβοιαι, danced together in the wild forest with Artemis (117–41). Aphrodite returns to the Nymphs at the end of the hymn, where she uses dance as a feature that is distinctive to these particular divinities, saying that they “tread the lovely dance (καλὸν χορόν) among the immortals” (254–76). Dancing Nymphs similarly appear in the Homeric Hymn to Dionysos, where they move alongside Dionysos (10–11). Perhaps the clearest discussion of dancing Nymphs in relation to Pan occurs in the Homeric Hymn to Pan, where the “clear-voiced mountain Nymphs” (Νύμφαι ὀρεστιάδες λιγύμολποι, 19), “moving nimbly” (φοιτῶσαι πύκα, 20) beside Pan as they sing and dance (μέλπονται, 21). Later fifth-century comedy similarly develops the idea of choral Nymphs, who dance in caves with the chorus in Aristophanes’ Birds (1099), or who dance in a chorus with Socrates in Clouds (271). The inclusion of dancing Nymphs on the fourth-century votive reliefs, therefore, would have immediately evoked for the viewer the choreia with which these divinities were associated.24

In visually emphasizing the divinities’ choreia, the votive reliefs collectively present a consistent understanding of the Nymphs. Importantly, the portrayal of these divinities throughout the corpus does not necessarily imply that it is possible, or even desirable, to reconstruct a sequence of danced steps or to determine to which performance or ritual these sculpted dances may allude. Indeed, it has already been argued by Naerebout and Smith, among others, that such endeavors are not only difficult but probably futile.25 Moreover, as with our discussion of divine music throughout this book, these images of divine dance cannot be understood solely as ideal versions of related human actions. Rather we must take seriously the particular way in which these divinities are shown responding to Pan’s music, how their movements affect other figures in the scenes, and how they may have engaged with the ancient viewers.26 Therefore, we must examine how these reliefs depict the Nymphs engaging with each other and with Pan through their shared experience of hearing the music and responding to its sounds through their dance, all within the cave shrines in which the images were once displayed. For instance, if we look again at the triangular relief (Fig. 1.2), we may see that while the repetition in their clothing emphasizes the dancers’ connection with each other, the individual variation that occurs in each Nymph’s dress, where one pulls her himation to her face, or another twists in her dance so that her drapery pulls tightly across her torso, also suggests distinct personae among them. Far from undermining the strength of their chorality, the distinctions made among each figure further underscore their unity, as each individual Nymph works with the others for their performance, responding as a unified group to the sounds of the music that they hear.

Similarly, if we return to the relief from Eleusis (Fig. 1.1), we may further see how interrelated Pan’s music is with the Nymphs’ dance, so that together, the gods are shown as a spectacle to be enjoyed. The relief makes clear that the divinities’ dancing is essential to its composition and perhaps even to a broader theological conception of the Nymphs as choral dancers. Together, Pan and the Nymphs complement the meaning of each other’s gesture: the visual sounds of Pan’s music are suggested by the Nymphs’ embodied response to it, physically moving to the sounds of the pipes. This close connection between musician and dancer is particularly drawn out here as the Nymphs’ swirling drapery echoes the curvilinear line of Pan’s chlamys, indicating that they hear his song and dance to his music. The left-most Nymph stares directly at Pan, as if captivated by his music, while the second looks down, absorbed in her dance. The final Nymph appears to have been startled mid-dance step by her foot hitting the cave wall (Fig. 1.6). Her surprise at her surroundings hints at the music’s ability to consume the full attention of whomsoever hears it. This subtle detail also points to the spaces in which the reliefs were displayed, as it potentially evokes the worshippers’ experiences within similar caves, where they may have also moved carefully throughout the dark landscape, hitting their feet against the rocks that jut outwards.

1.6. Detail of a Nymph. Votive relief depicting Pan and the Nymphs, from a cave of Pan in Eleusis, white marble, 28 × 35 cm, 325–300 bce.

We should also consider the space in which the Nymphs dance. Although in the literary sources the Nymphs typically dance outdoors in the wilderness, whether a forest or an open field, in the votive reliefs their dance always takes place in a cave. The reliefs thus clearly establish where these Nymphs dance and, by extension, where the viewer could expect to encounter the divinities. The relationship between landscape and dance is developed on a votive relief deposited in a cave sanctuary to Pan and the Nymphs at Megalopolis in Arcadia; although the relief was discovered outside of Attica, it largely adheres to the Attic style of representing these divinities, hinting at the broader dissemination of the Athenian theological conception of the divinities (Fig. 1.7).27 Here, the three divinities again take up the majority of the visual plane as they move within a shallow rocky frame that surrounds the image. Each is dressed similarly in a chitōn and himation, with her hair elaborately braided and pulled back. They move across the visual field while they hold onto each other’s robes. Their collective forward movement is made clear by the treatment of their drapery: deep incised lines reveal each dancer’s body by twisting and folding around her form. Their complementary movements and gestures thus establish their unified chorality.

1.7. Votive relief depicting Pan and the Nymphs, from Megalopolis, Pentelic marble, 55 × 73 cm, 330–320 bce.

The image also develops a close relationship between the dancers and Pan. The musician sits adjacent to the dancing chorus and holds his instrument up to his mouth, his nearly frontal position confronting the external viewer with his musical performance. The dancer closest to Pan most clearly exhibits the influence his music has on her. The broad sweeping lines of her drapery echo the rigid parallel lines of Pan’s syrinx. The deep, incised folds of her clothing gradually become animated as they near her ankles, where her drapery gently twists out behind her as she internalizes his music and expresses it through her movements. She also maintains a physical connection with Pan through her hanging drapery, which falls on his leg. A strong diagonal thus extends from her arm, down through her drapery, and continues with the line of his leg. A similarly formed diagonal intersects with this line, beginning with Pan’s right arm and continuing through the dancer’s outstretched right leg, creating a chiastic effect between these two figures that exemplifies the integration of their movements. The divinities are thus shown not only dancing within their cave to music that originates from Pan’s syrinx, but they are depicted as having been completely absorbed by his performance.

Beyond locating the divine musical and dance performance within the walls of a cave, this relief also displays an awareness of the relationship between the divinities and the natural landscape.28 For instance, the dancer furthest away from Pan, the tallest of the three, holds out a sheath of wheat, as if displaying the grains to her external audience. The plant’s curvilinear stalks and leaves repeat the lines of their drapery that move and twist around their bodies as they dance, suggesting a deep connection between the plant’s growth and the choral performance. While this relief is unique in its inclusion of plant life and may draw from other representations of the Horai,29 the image provides what is perhaps the most overt reinforcement of the Nymphs’ fundamental connection with nature, which is not elsewhere seen in the votive reliefs but which, as we have seen, is a recognizable element of their divinity as it is presented in literary evidence. For the ancient worshipper, who would have probably travelled to a cave to venerate the Nymphs, this relief from Megalopolis would have brought to mind the entire semantic range of meaning associated with these particular divinities. In other words, when confronted with the image of Nymphs dancing, worshippers may have recalled the reasons for which they had come to worship the Nymphs: the growth and prosperity of plants and animals, the continuation of natural fertility, and the regeneration of human life.

Further nuancing the Nymphs’ dance on the votive reliefs is the close syntactical relationship between divine Nymphs and mortal young women. Their name, nymphai, hints at their ambiguous status, where the term refers both to the nature spirits and to young women.30 In Euripides’ Ion, discussed above, the tragedian conflates the mortal Aglaurids, who are young, unmarried virgins, or nymphai, with the dancing Nymphs.31 However, despite their shared actions, the Aglaurids are not divine nor can they expect to have the Nymphs’ long lifespan.32 Rather, Euripides’ elision of the two groups establishes a link between young female figures and the physical landscape of Athens, in which the Nymphs are “almost omnipresent.”33 The young girls in Euripides’ tragedy are thus at once representative of an ever-present potential for future regeneration, much as we see with the Nymphs or Horai on the relief from Megalopolis, but as the daughters of King Erechtheus, who was born from the earth itself, they also maintain a link with the Athenian landscape through their genealogical heritage. In front of Athena’s temple, with the patron goddess of the city as their audience, the three young women dance with Pan, continually celebrating the Athenian landscape in order to ensure the continual prosperity of the polis and its citizens. We might consider the female visitors who travelled to the cave sanctuaries of Pan and the Nymphs as similarly engaged with the full semantic understanding of Nymphs, so that they could venerate the Nymphs even as they were themselves nymphai. The potential for an embodied response to the scenes of divine music and dance, and even the embodied participation in the divine celebration, was thus built into the very framework of cult worship for the Nymphs.

Gods and Sacred Caves

Pan’s choice of musical instrument and his moveable location within the votive reliefs owes much to his genealogical ties with his father Hermes, who invented the syrinx at the end of the Homeric Hymn to Hermes (512) and who, as the messenger god, was thought to be capable of moving through disparate spatial realms.34 It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that Hermes is included in the majority of reliefs. Unlike Pan, however, Hermes’ position within each composition is much more consistent: in the majority of votive reliefs, the messenger god holds a Nymph’s hand and acts as the dominant male koryphaios (κορυφαῖος) as he leads the dancing divinities forwards.35 The only major point of change in Hermes’ representation is the position of his body, which can range from a profile position, such as on a relief from Megara (Fig. 1.13), to a three-quarters view as on a vertically oriented relief from the Vari Cave where the god stands in contrapposto,36 or a frontal position as on another relief from the Vari Cave (Fig. 1.12). In each instance, however, Hermes maintains close physical contact with the Nymphs, evoking the theological relationship that existed among the divinities.37

Hermes’ role as a messenger god, responsible for transporting figures across borders, is underscored by his actions in the reliefs, where he directs the Nymphs’ dance.38 His function as leader of their choral dance is particularly emphasized on a relief found in the Piraeus, where the god carries his kērykeion, his messenger staff, as he dances, guiding the chorus’ path (Fig. 1.8).39 Hermes here does not simply guide the Nymphs’ movements within their cave, directing them around the altar, but as he moves forward, his hand and kērykeion overlap with the rocky frame. By intruding upon the physical boundary that encloses the image, Hermes’ actions draw attention to the distinct framing device that is unique to this corpus of votive reliefs. And, if we were to consider Hermes’ boundary-crossing movement together with Pan’s frequent appearance on the frame, the reliefs as a group seem to play with their physical boundaries, exploring that point of tension where the sculpted image begins and ends.

1.8. Votive relief depicting Hermes, Pan, and the Nymphs, found in the foundations of a private house in Piraeus, white marble, 27 × 38 cm, 320–300 bce.

The figure of Hermes thus draws repeated attention not only to the cave frame and setting in which the gods perform, but also to the actual caves in which the reliefs were displayed and in which ancient viewers would have encountered their imagery. Such engagement between the scene, the object, and the landscape thus suggests that there was an awareness of the potential for interaction between the image and the cave shrine in which the reliefs were deposited and displayed. Indeed, the surviving Attic cave sanctuaries that housed dedications to Pan and the Nymphs offer an entirely unique opportunity to situate visual representations of divine music and dance within their ancient context.40 It is thus worth taking a closer look both at the Dyskolos, a fourth-century comedy by Menander, and at the surviving cave shrines sacred to Pan and the Nymphs, in order to gain a better sense of how a cave landscape may have affected the ways in which ancient viewers encountered and experienced the votive reliefs and the cult more broadly. Moreover, in attempting to position the reliefs within their original landscape, we must also posit active and willing viewers, who were eager to engage with the experience of the divine that the caves offered, since they deliberately had to leave Athens and travel to the cave shrines.41

As we have seen across a number of examples, while the votive reliefs consistently introduce the presence of divine music and dance to the sacred space of the cave shrines, they are less forthcoming about whether music was a feature of human ritual activity in those spaces. While there is, unfortunately, little evidence that speaks to human musical activities in the caves, Menander’s Dyskolos, a comedy performed in 316 bce, offers an example of cult activity for Pan and the Nymphs, where a small community convenes outside of a cave at Phyle, located to the northwest of Athens.42 The religious gathering, which would have been staged in the center of the orchestra between the houses of Knemon and Gorgias,43 takes on the qualities of a raucous celebration, during which the worshippers play music, dance, pour libations, eat the meat of a sacrificed sheep, and drink wine, all within the sacred cave where couches for the participants have been set up.44 Though no clear archaeological evidence has survived attesting to these actions in actual ritual practice, Menander’s comedy provides invaluable evidence for the effect that Pan’s music was understood to have on his mortal audience, as well as for how music may have functioned more generally within the context of cult for Pan and the Nymphs.45

While this dramatic performance of the ritual took place on stage, so that its costumes, sets, and songs presented their own sensory experiences to the audience, Menander’s clear portrayal of the setting and actions nevertheless allows for an imaginative reconstruction of the participants’ potential experience. In this scene, the worshippers are described as having gathered within the small enclosure of Pan’s cave,46 where each sensory element of the ritual would have been amplified. In addition to the smell and taste of food, we might also imagine the participants listening to the rich, resonant sounds of the aulos that would have filled the cave. In fact, Menander places particular emphasis on music, and Sostratos’ mother, whose dream inspired the sacrifice, instructs a young girl named Parthenis to “play Pan’s song, [since] this god, they say, should not be approached in silence,” αὔλει, Παρθενί, | Πανός σιωπῇ, φασί, τούτῳ τῷ θεῷ | οὐ δεῖ προσιέναι (432–34).47 At one point, the sounds of the instruments, the women’s dance, and general merriment were so loud, that one character, Getas, remarked to Sikon that the worshippers “are making such a racket in there, carousing – no one will notice,” θόρυβός ἐστιν ἔνδον, | πίνουσιν· οὐκ αἰσθήσετ᾿ οὐδείς (901–02).48 Getas’ remark also points to the extent to which the human, ritual, and musical sounds could echo throughout the cave. We may further imagine, then, that the particular blending of sounds from the music, the women’s dance, and the feasting produced a cacophony appropriate to Pan’s musical nature.49 In Menander’s comedy, while the cave provides the setting for the ritual celebration and feast, it is the amplified sounds of music that seem to facilitate a possible encounter with the gods themselves.50

Menander’s Dyskolos thus gives detailed attention to the sensory experience offered by the performance of music and dance within the cave shrine, so that the natural sounds produced by the cave accompany those created by the worshippers. We might expect, then, that a group of worshippers approaching a cave to Pan and the Nymphs could also potentially have played music. Although no surviving evidence can establish that humans performed music within the caves, it is clear from the votive reliefs that these spaces were conceived as having been infused with musical sounds and, when considered together with the Dyskolos, that these sounds could have been partially produced by the cave itself and partially by human musicians. Within this framework, Pan joins his worshippers in performing his own music, while the Nymphs depicted in the reliefs dance to both human and divine musical sounds. This mimetic repetition between a god making music and his human worshippers playing their instruments suggests a high degree of participation required of the viewers when they encountered these votive reliefs. Not only did they look actively at the scene, but they may even have lent their own music to their experience of viewing, so that they could have engaged with the image both visually and sonically.

If we turn our attention to a particularly well-preserved cave in Attica, the Vari Cave on Mount Hymettos, we find that it similarly offers a powerfully evocative experience within its walls.51 Moreover, given its relatively intact state and the archaeological work previously undertaken there, this cave also offers a compelling example for reconstructing the appearance of the ancient religious site and the rituals that would have occurred within it. Familiar to local shepherds who used it to find shelter for themselves and their flocks,52 the cave became known to scholars after Richard Chandler came across it in 1765.53 It was subsequently visited by European travelers throughout the nineteenth century and first excavated in 1901 by a team of American archaeologists.54 The site and its finds have been re-examined by J. M. Wickens in 1986, and more recently by Günther Schörner and H. R. Goette, who significantly add to our understanding of the cave, which is not otherwise mentioned in surviving ancient literature.55 In addition to studying the finds discovered in the cave, they also attempted a reconstruction of ancient worshippers’ movements within the space based on the surviving inscriptions, the physical landscape of the cave, and initiation cults involving the Nymphs.56

Together with other surviving caves sacred to Pan and the Nymphs, such as those at Phyle and Penteli, the Vari Cave presents a clear picture of the typical appearance of late Classical cave shrines.57 Regular features in these caves include small springs with fresh water, terracotta figurines of Pan and, occasionally, Silenos, pottery fragments of loutrophoroi, and wall inscriptions. The body of each cave could also be manipulated and adapted by particularly devout individuals; at Vari, a certain Archedemos from Thera claims to have renovated it and the work that he apparently undertook seems to have transformed the cave into its current state (Fig. 1.9).58 In each instance, the votive reliefs were set up throughout the cave: at least seven complete reliefs have been reconstructed from the cave at Phyle, with additional fragments, while another seven, with additional fragments, were found in the Vari Cave.59 Importantly for my discussion, the Vari Cave was discovered in a relatively intact condition, and because of the amount of evidence that has survived from it, it is a site that lends itself to a rich, sensory interpretation of the archaeological evidence.60 Moreover, given the cave’s high level of preservation, it offers an exciting opportunity to situate the ancient worshipper’s potential religious experience within a distinct and defined landscape.61 Indeed, the thorough excavation and subsequent publications of the Vari Cave, as well as its excellent state of preservation, provide the most complete picture of what probably occurred within cave sanctuaries to Pan and the Nymphs. Although it is difficult to be certain as to how an ancient visitor to the cave would have experienced its features, the cave’s landscape has changed little since antiquity,62 so that certain traces in the archaeological site expose what must necessarily have been visible to ancient visitors. Much of my analysis thus foregrounds both the worshippers’ potential interactions with the reliefs that would have been displayed in the cave and the suggestion of music within the cave and the reliefs.63

Since the Attic cult for Pan and the Nymphs was regularly located in caves, consistent across the worshippers’ potential experience of the votive reliefs was the way in which the dramatically different environmental conditions of the subterranean shrines amplified the senses, bent sounds, and introduced a unique sensorial environment into the context of religious ritual.64 The Vari Cave, with its dark rooms, dripping water, and echoing sounds, offers this particular range of sensorial experiences and, as a result, its physical landscape becomes much more than a simple delineation of sacred space that passively hosts the rituals performed within it. Rather, by acknowledging its role in enhancing visitors’ sensory perception, we allow for the possibility that the cave actively contributed to the ancient worshippers’ experience of religious ritual for Pan and the Nymphs.65 Moreover, the specific experience the cave offers to its visitors is as essential a part of the ritual as are the actions performed or offerings given.66 The Vari Cave, in other words, works upon all those who entered, exerting its own material presence upon them. The cave’s rocks, earth, moss, and water, as well as the gradual darkness and echoing sounds that it creates, all would have contributed, and indeed still do, to one’s experience of its landscape. The entirety of the cave could thus actively affect the worshipper’s perception of that space.67

The Vari Cave adheres to the general trend for these cave shrines in that it is located far outside the city limits of Athens.68 Most of the journey from the city to this specific shrine is steadily uphill and becomes increasingly rural; in antiquity, worshippers would probably have passed shepherds and their flocks along the way. One’s sensory experience on this isolated mountain walk would have been, and indeed still is, one of relative silence except for the noises of animals, the rustling of plants and trees, and the crunching of grass underfoot.69 The cave itself is not immediately visible from the slope of the mountain, since its small entrance opens almost directly downwards into the earth, where it divides into two rooms separated by a large, rocky barrier wall.70 The cave, in contrast with the mountainside, thus presents a very different sensorial field that is determined by its cavernous nature.71 It was, and remains, a dark, damp space: the western room descends quickly, engulfing its visitors in darkness, while throughout both rooms water continuously drips from the stalactites that cover the ceiling. There is even a small pool in the western room, upon which is inscribed ΧΑΡΙΤΟΣ, indicating that the pool belonged to one of the Graces, or possibly to a single nymph (Fig. 1.10).72 Though the basin is now empty, in antiquity the water’s own material nature not only would have conditioned its movement within its rocky container, but the sounds it would have created as it flowed around the small basin would have contributed to the other sounds already present within the cave. Moreover, the presence of the manmade basin suggests deliberate human activity in the space: in antiquity, the continuous stream of water dripping from the stalactites and the gurgling of water in the spring located on the far side of the eastern room may have prompted worshippers to carve out this small pool.73 This attention to the cave’s landscape and a deliberate attempt to enhance its natural features amplifies the auditory presence of water in the cave, and may even suggest that within it, the sound produced by the abundance of water was conceptualized as an auditory manifestation of a divinity.74

Indeed, water’s pervasive presence throughout this particular cave may be associated with the similarly ubiquitous presence of Acheloös, the god of the large river in northern Greece who is included in the majority of the late Classical votive reliefs.75 The sound of the water as it drips and falls from the stalactites or moves within the spring thus is more than the material presence of naturally occurring water and, instead, it becomes almost indistinguishable from the god.76 The omnipresence of water, combined with the repeated depiction of Acheloös on the reliefs where he emerges from the cave walls, reinforces the visitor’s impression that the god is eternally present and hints at the way that watery sounds moved throughout the space. The water that Acheloös embodies may thus be conceived as dripping from the rocky material of the Vari Cave, so that each time visitors heard the water or felt it drip upon them, they experienced the physical presence of the river god. Above all, by drawing out the connections between the reliefs and the water and rock of their physical surroundings, the images establish the environment of the Vari Cave as one that is materially divine.

Further enhancing the relationship between the carved reliefs that were deposited in this and other cave shrines and the landscape of the caves themselves is the rocky frame that surrounds each votive; as we have seen, almost the entire corpus of votive reliefs dedicated to Pan and the Nymphs exhibits this feature.77 The sculpted cave thus refers both to the cave in which the relief was deposited and to the rocky material substance from which the image was made. The ancient viewers who looked at the reliefs within the actual, physical space of the Vari Cave would have perceived a clear repetition, a visual doubling, between the frame and the walls of the cave. We have already encountered one relief from the Vari Cave that was carved into a roughly triangular shape (Fig. 1.2), while yet another was shaped into a tall, rounded hill, each echoing the shape of the very mountain into which the cave descended.78 As a group, therefore, the reliefs are intimately linked with their environment in their shared material and form.

Within the Vari Cave, the votive reliefs were once set up on the hill in the southern room (Fig. 1.11). Importantly, their mode of display in this particular cave differs from contemporaneous practices in open-air shrines, where votive reliefs were typically set up on top of stēlai; instead, based on the surviving cuttings in the rock, here they seem to have been inset into holes drilled down into the hill or inserted into recesses carved directly in the walls of the cave.79 Set into the cave’s upward incline in this way, the images would have loomed over the visitors as they entered the southern room and stood on the flattened platform at the base of the hill.80 However, as the worshippers approached the reliefs, the gods would have been visible at eye level or even slightly below. Each relief would probably have also been brightly painted, so that the divine bodies would have stood out against the rocky landscape, almost appearing to dance and play music in the cave itself. When looking at the reliefs, perhaps even walking among them on the hill, the ancient worshippers encountered a mimetic echo between the actual, physical cave in which each relief was dedicated and the sculpted cave that surrounds the gods. This perceived blurring, encouraged by the rock frames and subterranean setting of each relief, allows the images to fold into the cave’s own landscape, the visitor’s sensory experience of the reliefs collapsing into their physical experience of the cave.81 The repetition between landscape and image, sanctuary and icon, not only draws attention to the importance the physical cave had for the Athenians’ conception of Pan and the Nymphs, but also suggests that it both determined and created the conditions in which worshippers experienced the presence of the gods. The sheep and goats that are often depicted on the frame of the reliefs echo this visual blurring between divine image and sacred space, because they recall the animals that roam the slopes of Mount Hymettos, the shepherds who enter the cave to rest with their flocks, and the goats that run with Pan in the countryside.

The corpus of votive reliefs thus presents a consistent portrayal of the divinities within their cave: Pan plays his music while his sheep and goats hop across the rocky landscape, the Nymphs dance across the relief and are often led forward by Hermes, and Acheloös watches over the performance. Given that a clear context exists for these objects, it becomes possible to analyze the imagery presented on the reliefs within potential ancient experiences in the cave sanctuaries. It thus remains to discuss how the images could communicate the sounds of divine music to the viewer within visually similar spaces, and also what experience ancient worshippers might have sought to engender by depositing reliefs that consistently depicted the gods playing music and dancing. How, in other words, did the reliefs create a landscape that invited the possibility of human participation in Pan’s musical performance and the Nymphs’ dance within these caves?

Divine Music and Dance in the Cave

Above all, scenes of the gods’ music and dance invite us to think about how worshippers were invited to interact with, and even amplify, the divine performance within the cave shrines of Pan and the Nymphs. Beyond the deliberate evocations of the physical space around them, the consistent depictions of divine music in the votive reliefs point to the importance of music within the space of the cave, as we see with an inscription left by Archedemos near the entrance to the Vari Cave.82 It reads:

With this inscription, Archedemos clearly establishes his identity as a Theran, isolating himself from any particular Attic deme or tribe, though he may have been a metic in Athens.84 He further describes himself as a nympholept, someone possessed by the Nymphs.85 The ritual consequences of using this loaded term, however, are unclear, as it could imply that an individual was caught up in a frenzy, had oracular capabilities, or experienced heightened awareness and clarity of thought, as occurs in Plato’s Phaedrus. There, when Socrates responds to Phaedrus, who has noted that an unusual rhetorical eloquence accompanies Socrates’ sentences, he says: “Then be quiet and listen to me. For the place seems truly inspired by a god (θεῖος ἔοικεν), so do not be surprised if I perhaps become possessed by the nymphs (νυμφόληπτος) as my speech progresses. You see at the moment I am also at the point of breaking out into dithyrambs (διθυράμβων φθέγγομαι)” (238d).86 As the philosopher comes under the influence of the Nymphs, present at their nearby shrine on the Ilissos river, he demands silence in his audience, so that his musical, and even dithyrambic, performance can be clearly heard.87

There is thus something inherently musical, or at the very least poetic, in the term nympholept. If we return to the inscription left by Archedemos in the Vari Cave, we may see a hint of a similar relationship between the Nymphs and poetic music, as well as some attempt to introduce music into the cave. Though the initial three lines are challenging to scan, the last three form an iambic trimeter.88 While it is difficult to determine the precise character of these lines’ musicality, at the very least the inscription evokes a sonic quality, as it could have been read out loud within the cave, almost confirming the Nymphs’ power in their cave by infusing that space with the sounds of testimony to divine presence.89 If we take the attempt at metrical composition seriously, then we have a rudimentary song, which could be sung out into the cave, possibly for the Nymphs, the divine audience for this performance. Thus, already at the entrance to the cave, this inscription provides a connection among worship for the Nymphs, music, and sung poetry.90

The votive reliefs to Pan and the Nymphs, together with the landscapes of the cave in which they were displayed and the suggestion of music within them, thus suggest a mode of interacting with divine music that was available to the ancients themselves. If we return to the relief where Hermes’ kērykeion intrudes upon the rock wall of the frame (Fig. 1.8) with a deeper understanding of the context in which the relief was displayed, the image suggests that the god could continue walking forwards, up to, and through the frame. Moreover, his assertive grasp upon the Nymph’s hand raises the possibility that as the god moves through the frame, so too will the Nymphs join him on his journey. The relief thus presents Hermes both as a leader of the Nymphs’ dance within their cave, as well as a god capable of moving individuals, whether human or divine, across otherwise solid boundaries, since both spaces are infused with music.

Pan’s moveable position throughout the corpus of reliefs further nuances our understanding of the effect of divine music within the ancient caves and the particular ways in which space, both in the image and within the physical caves, was manipulated to make divine music more accessible to the worshippers. Moreover, the god’s changeable position at the limits of each image, whether on the frame or the edge of the visual field, confers a sense of liminality to the god’s presence, so that the peripheral Pan acts not just as the source of music, but also as a mediator between human viewer and dancing Nymph.91 On a relief dedicated to the Nymphs by Eukleides, Eukles, and Lakrates (Fig. 1.12),92 the main visual field is taken up by the three dancing Nymphs and Hermes, who holds his kērykeion in his left hand while he guides their dance forward, while Pan stands to the right, overlapping with the rocky frame that encloses the image. As he stands in this visually indistinct space, he lifts his syrinx to his mouth and creates the music to which the Nymphs dance. The rightmost Nymph takes a step to the left, and as she passes by Pan, her foot overlaps with his, emphasizing the connection between her dancing steps and his music. The central Nymph is almost frontal facing and is carved in the deepest relief, suggesting that she is the closest to the viewer as she weaves back and forth. The Nymph at the beginning of the line, depicted in profile, takes a step to the left, which creates the forward momentum that pulls her companions with her past the altar. Her robes sweep out behind her and frame the entire altar.93 The group’s movement is directed toward a frontal mask of Acheloös, embedded in the rounded arch of the cave wall where he evokes the water that drips down throughout the space. As the Nymphs dance to Pan’s music and follow Hermes, they twist their way through their dark cave, passing by the altar and emerging on the other side.94 But more than simply dancing across the space occupied by the altar, in this scene the group transgresses the spatial boundaries of the image itself: Hermes, with his right hand, touches Acheloös’ horn and bores through the wall of the cave.95 The dancing divinities follow him, moving dynamically to the sounds of Pan’s music as they walk toward and, presumably, through the frame.

1.12. Votive relief dedicated to the Nymphs by Eukleides, Eukles, and Lakrates, from the cave to the Nymphs (Vari Cave) on Mount Hymettos, white marble, 40 × 50 cm, 340–330 bce.

We see another instance where Pan’s musicality and moveability act as essential compositional elements of these reliefs, together preparing viewers to experience the god’s music by inviting them to search visually for the god, to enliven both his actions and his performance. Looking beyond the corpus of reliefs to Pan and the Nymphs to a late fourth-century votive dedicated to the goddess Kybele, we see Pan and his music acting as intermediaries between human and divine. On the relief, the goddess sits on a throne, holding a tambourine, or tympanon, in one hand and a libation bowl in the other (Fig. 1.5).96 At her feet sits a lion, mimicking the frontal posture the goddess maintains, while a young lion stretches across her lap. Meanwhile, Pan is suspended against the left column of the naiskos framing the seated goddess. Positioned in a manner similar to Kybele, Pan is depicted in a frontal stance, echoing the goddess’ own confrontation with her viewers. Pan’s stillness on the frame, where he stands with one hand straight down by his side, is offset by a single gesture: as on the reliefs dedicated to Pan and the Nymphs, he raises his syrinx to his mouth to play the instrument. He is joined on the relief’s frame by two other individuals, possibly intended to depict human worshippers.97 They are represented in profile, turning their heads and bodies toward the enthroned goddess.

In locating Pan’s musical performance on the relief’s frame, the image explores how divine presence manifests within the experience of worship and, even more, how divine music is essential to that process. Positioned on the frame, Pan’s music surrounds and encloses Kybele, following the architectural barrier established by the relief itself. In this way, both he and his music at once act as a barrier and a mediator between human and divine. Indeed, the image hints that Kybele betrays an awareness of the unifying effect of his melody. The specific manner in which Kybele holds out her libation dish, tilting it to pour out its contents, suggests that she may soon put the vessel down, her ritual having been completed,98 and will devote her attention to the other object she holds, her tambourine. The large size of her instrument further draws attention to the potential music that the goddess might soon create, so that the viewer is invited to imagine the percussive sounds of the tambourine blended with the piped music from the syrinx.99

The musical potential built into her representation here adds a sense of energy to her entire appearance, as if she might, at any moment, be animated through the sounds of Pan’s music to devote her attention to musical performance and to move her body to its music. Indeed, the image hints at the kinetic potential bound up in her figure: as the goddess leans forward, her right leg follows the movement of her body, and her foot slips over the podium upon which her throne stands, as though she is about to stand and take a step outward into the space beyond the relief. Yet her body position is ambiguous, for while her lower body suggests forward momentum, her upper body remains firmly within her naiskos. Her head betrays no movement, and she continues to stare directly ahead. The two figures depicted on the frame, possibly a man and woman who have come to worship Kybele, are similarly depicted in a moment of transition between action and stillness. They are each shown with one leg outstretched behind, as if to suggest that they are in the act of walking past Pan and toward the goddess. Furthermore, just as Kybele’s foot encroaches upon the surface of the relief, as if emerging from the stone, so do the worshippers’ hands intrude deeper into the relief as they reach around the side of the pilasters, their outstretched limbs coming ever closer to the goddess. In depicting the effect of Pan’s music in this way, the relief thus captures in stone a crucial element in our understanding of the significance of Pan’s music for his human audience, for whom the act of hearing his music could have the ability to bring them closer together through the shared act of listening. Pan’s frontal position in this image, so reminiscent of his appearance on the votive reliefs to Pan and the Nymphs, thus continually offers this possibility to his audience, inviting them to hear his music through looking at his image.

Dancing with the Gods

The visual repetition between the sculpted cave that surrounds the votive reliefs and the actual, physical cave in which the reliefs were displayed blurs the image into its surroundings, so that Pan’s music and the Nymphs’ dancing bodies seem to slip easily from the cave carved into the marble slab to the one made up of the living rock. In this way, as the viewer is invited to imagine the sounds of Pan’s music and see the Nymphs dancing to the piped music within their cave, each image also suggests that this divine performance takes place in the very space in which the worshippers stand, so that god and mortal occupy the same landscape. Further obscuring the limitations of each relief are the frontal faces that are regular compositional features of the reliefs.100 The Nymphs, for instance, often betray an awareness of the space beyond the image by the direction of their gazes. Not only may they be depicted frontally, as if piercing the surface of the image with their movements, but the central Nymph, positioned second in the line of dancing women, is also frequently shown gazing out into the space beyond the carved relief.101 Their direct gazes may thus be conceived as connecting with those of the worshippers, bringing about an epiphany through ritually conditioned modes of looking.102

The concept of kinesthetic empathy is particularly relevant here since it allows us to examine how ancient viewers may have engaged with these scenes of dancing Nymphs – how, in other words, they might “feel when [they] watch dancing.”103 The term, which developed from current work in dance studies, may be defined following Deidre Sklar as “the process of translating from visual to kinesthetic modes,” so that the viewer gains the capacity “to participate with another’s movement or another’s sensory experience of movement.”104 The importance of sight within a dance, whether the gazes exchanged among the figures who dance or between the spectators who look upon a performance, should not be underestimated: in each instance, bodily movement or physical responses to the dance are encouraged through these acts of looking and, by extension, of imaginatively hearing the sounds of Pan’s music and feeling it move through one’s physical body. Such embodied seeing that is encouraged by the Nymphs’ awareness of their audience is thus further complemented by the viewing audience’s potential response to Pan’s music, as well as to the sights and sounds of the cave itself. As a result, whether or not visitors to the cave sanctuaries of Pan and the Nymphs played their own musical instruments, their encounter with the votive reliefs still remained a multisensory one. Not only would they have seen the figures carved into the reliefs, but they would also have smelled the dampness of the cave and heard the torches snapping and crackling in the dim lighting, all of which affected their encounter with the image. Adding to the distinct sensoryscape offered by each cave was the worshipper’s potential enlivening of Pan’s musical performance, so that he or she imaginatively listened to his pipes by drawing on their previous experiences with what type of melody a syrinx produces, how it felt to participate with one’s peers in a communal dance, and what it meant to internalize a melody and respond to it with one’s body.105 Therefore, while music may have been made within the caves, and may even have been required of the worshippers as they approach the sanctuary, musical sounds already were virtually present in the cave through their inclusion in the votive reliefs. Each image thus invites the viewer to search for the source of music to which they dance: Pan’s moveable position in the image works in tandem with the Nymphs’ dance, so that the worshippers would need to actively search for the musician and, upon discovering him, imaginatively listen to the sound of his music. By activating the images in this way, they might ‘hear’ Pan’s music within themselves as they watch the Nymphs perform their dance.

Mortal worshippers are shown as the audience for Pan’s music and the Nymphs’ dance on two reliefs, suggesting a potential model for human engagement with the divine within the space of the sacred caves. The first of the two, from Megara, located near the boundary of Attica, depicts a man, woman, and two children who stand near a stone altar while they look up at a chorus of dancing Nymphs who are being led forward by Hermes (Fig. 1.13).106 A small Pan is perched high up on the cave wall and holds his syrinx up to his mouth.107 Pan’s placement in the scene shows one possible way in which his music could affect the mortal worshippers. He sits directly above the human family, and his legs dangle below him, almost reaching the man’s head. While the family does not hold any instruments, it is nevertheless visually linked with Pan’s musical performance through its close proximity to him. Together, as musician and audience, the family and Pan complete the Nymphs’ dance, whether by playing the syrinx, watching the dance, or, for those worshippers who encounter this relief in their own cave, by imaginatively supplying the music to which the divinities move. The image thus suggests that the sculpted cave has been filled with divine and mortal music, creating a musically infused space in which the Nymphs freely dance.

A similar scene may be found on a relief from the deme of Hekale, located to the northeast of Athens (Fig. 1.14).108 Once again, Pan sits above the mortal worshippers and plays his syrinx. Below, the three Nymphs hold hands and, as a chorus, dance forwards. Their flowing drapery, suggested by the curvilinear lines used to demarcate their clothes, marks the unison of their physical movements. Immersed in their physical response to Pan’s music, the Nymphs’ dance draws them out of the deep cave, away from Acheloös and the water trickling down the walls, moving toward the altar. In front of this altar stand an older man, a woman, and a younger man, two of whom raise their hands in recognition and prayer as they watch the Nymphs’ performance. The mortal worshippers and Pan are again linked through their close visual proximity, suggesting that both are actively engaged in the Nymphs’ dance, whether by contributing the music that fills the cave or by watching the spectacle unfold. Moreover, there are a number of visual cues in this relief that suggest that it could have deliberately provoked its external audience to participate as well. Pan not only is depicted frontally, but even rests his arms on the image’s border line, suggesting that he exists at once outside of and within the image, in the space of the worshipper and of the dancing Nymphs. The young man to the far left mimics Pan’s frontality, directing his attention to his viewer. The central Nymph also betrays an awareness of the external cave in which the relief was deposited as she throws her head back and seems to look through the surface of the stone votive. In the figures’ awareness of the external world, the relief thus seems to invite its viewers to engage with the depictions of the dancing divinities, to imaginatively hear Pan’s music and to join the choral dance.

1.14. Votive Relief Depicting Pan, the Nymphs, and Worshippers, from Hekale, white marble, 28 × 52 cm, 325–300 bce.

Through his frontal position and the way in which his music surrounds the scene as it moves through the frame, Pan in this relief acts as a mediator between Nymph and mortal worshipper. He not only performs for those who have gathered in the cave, but he establishes them as the attentive audience for the Nymphs’ dance. Moreover, as we have seen, Pan’s marginal position on the frame infuses both spaces with his divine music. On the relief dedicated by Telephanes (Fig. 1.3), Pan sits on the top left side of the rectangular frame where he is surrounded by his goats as he plays his pipes. Just as the frame encloses the central scene, so too does Pan’s music, which cascades down and reverberates across the rocky frame, surround it with music. By occupying this liminal position on the frame, Pan is depicted in the parergonal space that belongs both to the image and to the external rocky cave.109 As such, he marks the dividing point between the figures depicted within the relief and those mortal viewers who exist beyond it. His frontal stare and bodily organization confront the visitor to the cave, establishing, in much the same way as a herm, a visual boundary that marks the distance between two spaces. The Archaizing style used for the depiction of his body also points to a visual relationship established between Pan and herms, drawing a formal connection between his rigidly formed body and that of a herm’s rectangular support, erect phallus, and Archaic facial features.110 The image thus suggests that Pan acts as an extension of Hermes, helping here to maintain the boundaries separating the human from the divine, even as he renders this barrier permeable through his music. In his liminal position on the frame, between the image and the outside world, Pan’s music oscillates between the two spaces and infuses the larger external cave with its sounds. Within the shared sensory experience offered to the sculpted figures in the relief and the worshippers standing in the cave, the formal boundaries between image and reality break down in the shared experience of listening to Pan’s music. Inside the frame, the three Nymphs hold hands and sway to the music as their drapery swirls around their legs. At the same time, within the dim lighting of the cave, the ancient viewer could see Hermes guiding the Nymphs’ dance to the left, out from their dark cave, passing from the image to the cave. Yet, as we can see in Telephanes’ relief, while Hermes leads the Nymphs to the left, the image depicts them taking small steps forwards, around the altar, and toward the viewer. As they move closer to the human world, they stare out, engaging the worshipper’s gaze and inviting them to join in their sacred dance.

While the depiction of Pan’s music prompts its viewers to recall the sounds of his instrument and contribute that sound to their viewing experience, the Nymphs’ embodied response to that music asks their audience to respond similarly, to feel the sound move through their own bodies. The significance of this shared sensory experience can be further explained if we return to Sklar’s definition of kinesthetic empathy as “the capacity to participate with another’s movement or another’s sensory experience of movement.”111 In her discussion of choreia in the Greek theater, Olsen expands upon Sklar’s work to suggest that though dance is “initially received visually by the audience, ancient and modern theories of kinesthetic empathy and proprioception would suggest that viewers can also have an embodied response to dance, a sensation of felt participation or inner mimicry.”112 While our reliefs would not have been seen in the theater, they do depict scenes that, as I have shown, are broadly associated with choreia, so that they collectively created a similar opportunity for the ancient viewer to have an embodied experience of the divine musical and danced performance.113 For the viewer, who may have been standing in front of these reliefs, looking at them juxtaposed with the rocky cave landscape in which they were displayed, the Telephanes relief offers one way by which to experience, by way of kinesthetic empathy, the divine music, the divine dance, and the sacred space in which both occur. The image, in other words, repeatedly invites its viewers to see themselves in the same physical space as the gods, to imaginatively listen to Pan’s music, and to jump up, assemble some companions, and dance around the cave, joining the Nymphs in their chorus.114 Bodies thus come together through embodied seeing and listening, so that whether stone, human, or divine, all may dance together in a moment of visual and kinesthetic unity.

This kind of powerful, embodied provocation is particularly evident with the relief dedicated by Eukleides, Eukles, and Lakrates in the Vari Cave, discussed briefly above (Fig. 1.12). Here, three Nymphs follow Hermes as they dance to the left, while Pan stands on the right as he plays his syrinx. The first Nymph energetically follows Hermes by the altar, and the central Nymph throws open her body, facing the viewer in an almost complete frontal position as she dances to the left. The final Nymph takes a step into the relief, entering it on the diagonal as she holds her companion’s outstretched hand with her left. Hermes is also frontally facing and takes a diagonal step outwards, toward the viewer. Together, the four figures almost seem to create a semicircle, where at the right of the relief the Nymph enters the relief, and on the left Hermes prepares to step out of it.115

But where do they step out to? Let us return to the Vari Cave, where our ancient worshippers stand together at the base of the southern room, where there extends a large, flattened-out terrace. As they look up at the reliefs, they would have seen Hermes leading three dancing Nymphs while Pan plays his syrinx, whose music the viewers imaginatively enliven. They might take in the relief, animated by the music they have imagined and heard, and then see Hermes step out of the scene and move toward them. Through their shared acts of listening to Pan’s song and playing their own music, the worshippers could join in their celebration, and together, god, Nymph, and human dance across the floors of the cave. These images thus require the viewer to have a multisensory experience in which sight becomes confused with sound, and sound is then translated into a bodily response through dance. In this way, the human visitors to the cave do not merely see a god, but rather they experience an epiphany of Pan and the Nymphs in their own bodies by sharing in the Nymphs’ physical response to Pan’s music.

Just as Pan’s music has an effect upon the Nymphs and inspires them to dance, so too could it have an effect on the human worshippers who travelled to the cave sanctuary and looked upon these reliefs. As we have seen, the god’s music is repeatedly shown having the ability to elevate the human listener to the level of the divine or to break down the barriers separating god and man, thereby allowing the Nymphs to step out of the reliefs and into the actual, physical cave. The viewers in turn could facilitate the Nymphs’ movement by contributing their own melody to the image when they respond cognitively to the representation of a musician playing his instrument; they hear the sounds of the pipes within their own minds by drawing on previous experiences of listening to the music produced by the instrument.

But more than simply witnessing the Nymphs dancing in their cave, these reliefs allowed for a fully embodied experience of the Nymphs: by imaginatively listening to the music that Pan plays, and perhaps even contributing their own music, ancient worshippers were repeatedly invited to join in the Nymphs’ dance. Not only would they have seen the Nymphs dancing in their cave, but they might even have heard the music to which the divinities dance and responded to it with their own bodies. The reliefs show, in other words, that an epiphany of Pan and the Nymphs was not one that was experienced through sight alone but, rather, the images encouraged their viewers to feel the Nymphs’ presence through their own bodies, so that Pan and the Nymphs became present to the worshippers when they listened to Pan’s syrinx or when they danced in the cave. Pan and the Nymphs were thus revealed when the worshippers committed themselves to a fully sensory and bodily engagement with the reliefs, at which point they could experience an epiphany of the gods by feeling the divine music move through their own bodies.