The Island of Kharg

KhargFootnote 2 is an Iranian island in the Persian Gulf, situated 25 km off the coast and 50 km northwest of the port of Bušehr. The island is 21 km2 in area, bisected by the 29.25° North latitude. The traditional economy of Kharg was based on modest warm-climate agriculture of date palm groves, citrus orchards, and vineyards, irrigated by subterranean channels called kāriz, while the nearby, uninhabited islet of Khārgu (Andarovi in local usage) served as pastureland. More remarkably, until recently Kharg was a centre of fishing, pearling, and sea pilotage. This had been the case since medieval times. Since the 1960s, the island has become a crude oil terminal and loading facility, attracting industrial workers from different parts of Iran. The population of Kharg increased from 650 in 1956 to 7,700 in 2011.Footnote 3

Historically Kharg is the only inhabited island associated with the province of Fārs. It has had commercial ties with Bušehr, the terminal point of Shiraz—Kāzerun—Borāzjān—Bušehr highway. The linguistic analysis presented in this paper suggests that Kharg had extensive maritime contact with the ports and islands around the Strait of Hormuz, which are historically associated with Kermān more than with Fārs.

The vernacular spoken in the Kharg Island is an isolated variety belonging to the Southwest stock of the Iranian language family. The language was first documented by the Persian publicist Jalāl Āl-e Aḥmad in his visit to the island in the late 1950s. He reports in his ethnography that out of the 120 resident households in Kharg, most had migrated from the coastal district of Tangestān and only a minority was local, and in terms of denomination the Shāfiʿi Sunnis were twice as many of Shiʿis. The native speakers characterised Khargi as a dialect close to those of Tangestān and Bušehr, the inland districts standing opposite to Kharg.Footnote 4 Āl-e Aḥmad published texts and a short glossaryFootnote 5 of the Khargi terms related to material culture.

Following the fundamental transformation of the island from an isolated rural society to a petroleum export hub, Kharg has seen a dramatic social and demographic shift. Persian has become dominant in all spheres of life. My interviews in 2016 revealed that Khargi was still spoken by as few as a dozen families, and even therein it was not properly transmitted to the new generation. The rest of the local population of the island was either the indigenous Khargis who had lost the native language or the immigrants from nearby littoral settlements who spoke their own kindred dialects.

Commensurate with the worry of its extinction, the local community has published new materials on Khargi: nostalgic poems by Jamāt MoždeFootnote 6 (henceforth JM) and proverbs by ʿAbdollāh Amāni.Footnote 7 The language of the latter works is in general agreement with that collected by Āl-e Aḥmad with only minor discrepancies. During a telecommuting documentation in 2016, I verified the materials from Āl-e Aḥmad and Možde and elicited additional data. My main informant was Manṣur ʿĀrefinežād, 41 years old, who had earned a postgraduate degree and worked at the Kharg Petrochemical Company. I also interviewed Ḥāj Sheikh Jamāt Možde, circa 70, the chief Sunni clergy of the Island.

1. Phonology

Khargi holds a solid membership in the Southwest branch of Iranian languages (§1.1). Within the Southwest domain, we may identify two isoglosses applicable to Khargi: the outcome of PIE *kw (§1.2) at an Old Iranian stage, and rhotacism of dentals (§1.10), a much younger sound shift.

1.0. Synchrony

The phonemic inventory of Khargi is typical to modern Southwest Iranian. The vocalic system consists of the vowels /ā o u a e i/ and semivowels /ey ow/. The phoneme /ā/ corresponds to [ɒ], much the same as common Persian. Vowel length is not phonemic: historically long vowels are occasionally pronounced long, especially in careful speech, as in Āl-e Aḥmad's documentation, but my further elicitation revealed that length is not distinctive, even when partially compensating for elision. The consonants are /b p t d k g č ǰ s z f v š x h q γ m n l r y/. The affricates are /č/ [t͡ʃ] and /ǰ/ [d͡ʒ]. As is the case with many Southwest varieties, ž probably does not exist as an independent phoneme, as there is mezo for Persian može “eyelash”. Notable is the distinction between /γ/ and /q/ in the minimal pair γāč “mushroom” vs. qāč “cross-eyed”.

1.1. Old Iranian Stage

Historical-comparative phonology places Khargi squarely within the Southwest Iranian family, the extinct members of which being Old Persian, Middle Persian, and medieval Shirazi. The oldest drifts of this family from proto-Iranian, *ts, *dz, *θr > h, d, s have reflexes in the Khargi words pah “goat” (cf. Av. *pasu- “small cattle”), ohi “gazelle” (< MPers. āhūg < OPers. *āθūka-; cf. Av. āsu- “swift” < PIE *ōḱú-sFootnote 8); demesto “winter” (cf. Manichaean MPers. dmystʾn), dehni “yesterday” (cf. Lori dinyā, Judeo-Shirazi dikna, MPers. dīk;Footnote 9 Northwest Iranian Kešaʾi heze), domah “son-in-law” (cf. MPers. dāmād, Av. zāmātar); pos “son” (< *puθra-), ās “hand mill” (cf. Pers. ās, Kešaʾi ār).

To the oldest stratum of sound changes, we may add the development *št > st that appear in most “fist” (cf. Lārestāni must, mos, Davāni mos, MPers. must/mušt, Balochi mušt, from PIr. *mušti-, with obscure etymonFootnote 10).

Another possible reflex of the split during the proto-Iranian stage can be sought in the Khargi word pas, standing for Pers. pašimān “regretful”. Should the Persian word be derived from paš “after, behind”,Footnote 11 the Khargi pas makes a convincing case for the development of PIr. *sč, which is reflected in the binary Av. pasca vs. OPers. pasā “after” (cf. Skt. paścā́ < PIIr. *pas(t)-sčā),Footnote 12 followed by Parthian paš vs. MPers. pas “after, behind”.Footnote 13

1.2. Proto-Fārs split

The development of PIE *kw, corresponding to PIr. *tsw, has three outcomes in Southwest Iranian languages. These are best reflected in the word “louse”, from PIr. *tswiš-: heš in Lārestān; teš in central-eastern Fārs, to the southeast of Shiraz; and šVš in the rest of Fārs, including the Kāzerun area and the littoral band running from Bušehr down to the Strait of Hormuz (see Table 2, Isogloss 3). Khargi šoš belongs to the latter group, concordant with the geography of Kharg. The Khargi form follows the chain of developments that retained the Old Iranian sibilant (*tswiš- > *siš > šVš ), as opposed to the Fārs varieties that turned it into the interdental /θ/ at either Old Iranian or Middle Iranian stage, and then to /t/ or /h/ at later stages.Footnote 14 Note that the Persian form of the word (from MPers. spiš, spuš ), with *sp, corresponds to the Northwest type development.

1.3. Middle Iranian stage

Here Khargi finds its place on the Southwest side of the binary division, due to these sound shifts: *ǰ > z in zan “woman”, *-č- > z in zi “under”,Footnote 15 *dw- > d- in dega “again, other”, *y- > ǰ in ǰoh “barley”.

1.4. *w-

The development of Middle West Iranian initial *w- > b is found systematically, e.g., in bād “wind”, bāru “rain”, bafr “snow”, korbak “frog”.Footnote 16 Note that *w- > b- occurs in all attested vernaculars of Fārs for the words “wind” (bâd, bâδ, bâ), “rain” (bâru(n)), and “snow” (usually barf, but also bafr, etc.Footnote 17). This sound change therefore must be deep-rooted in Fārs, quite possibly within Middle Iranian period; it forms a sharp isogloss within New Southwest Iranian, bisecting the Garmsiri languages of Kermān and Fārs.Footnote 18 See Isogloss 2 in Table 2. In Khargi the sound change *wi- > go is attested in a closed set, including goroxt (< *wirēxt-) “fled” and gošna “hungry”, as is the case in Persian.

1.5. Lenition

An opposite effect, softening of b > v, is prevalent in Khargi: vo “with” (< bā < abāg), verd- (< burd-) “carry”, tavar “axe”, tavesto “summer”, pā-sovok “swift”, ow “water”, ov-e garm “warm water”.

1.6. Consonant clusters

The inlaut cluster *xt survives: doxt “girl”, bext- “sift”, rext- “poor”, goroxt- “flee”.Footnote 19 The group *ft is reduced to t in the past stems got- “say”, xot- “sleep”, and gert- “seize”, but is retained in roft- “sweep”, baft- “weave”, šenaft- “hear”; this anomaly cannot be justified by etymology: the roots of the verbs are all labial: *gaub, *hwap/f, *grab, *raup, *wab/f, *xšnav, respectively.Footnote 20 The traces of this reduction may be sought in a noticeably longer vowel in a-xoˑt-e “he is sleeping” and gemination of the consonant in xett-i “he slept”, both carrying an underlying past stem *x(w)uft-. This reduction must be far more recent than the shift from Old Iranian *-t- to d, else the verb stems would have become d-final, thus subjected to rhotacisation discussed in §1.10.

1.7. Final consonants

Elision of the final consonant is the norm: nasals: nu “bread”, dondo “tooth”, darmu “cure”, zemi “earth”, and in personal endings (§3.5); stops: demād “son-in-law”, band “tie”, pust “skin”. See also §3.1.

1.8. Fronting of back vowels

A remarkable vocal development is fronting of original ū and ō, as seen in ši “husband”, ri “face”, hani (for Pers. hanuz) “yet”, ohi “gazelle”, xeyn “blood” (MJ xin), čipo “shepherd”, sandiq-āvāz “gramophone”, sizan “needle”, bir- < būd- “be”, šer- < *šid- < šud- “go”; but kur (< kōr) “blind”. Note also the residual maǰhul in meyz Footnote 21 “table”, še(y)r “lion”.

1.9. *-ak

Contraction of the Middle Persian suffix -ak/-ag can be seen in ostorg “star” (< stārag), meyg “locust” (for Pers. malax < Old Ir. *madaka-), seyg “shade” and hamsoyg “neighbour” (cf. Pers. hamsāye < ham-sāyagFootnote 22), and probably in Xārg “Kharg Island”, apparently from Xārag, comparable to Khargi xārak “date” (see below).

A renewed -ak is found in bačak “child”, beygak “doll”, toveyak “pan”, howdak “basin”, xārak “date”, pahak “unripe date” to express endearment or diminution.

There is yet another set, in -e, that has emerged from the Middle West Iranian ak: čāle “hearth” (< *čāl-ak “pit, hollow”), ǰume “clothing”, kiče “alley”, gordāle “kidney”, darve “gorge” (Mid. Pers. darrag < *darnaka); the last two words, due to their idiosyncratic phonology, should not be recent loans from Persian.

A final -a is chiefly a result of contraction: plural marker ha- (< hā), xorma “date” (< xormā), dega “again, other” (< dīgar), yema “we” (< amāh), ta “thou” (< tō < *tava-), bāla “up” (< bālā), kārga “workplace” (< kārgāh). The last word is expected to be kārgah due to the pattern -āh > ah, in rah “road”, kah “straw”, čah “pit, well” and other words.

1.10. Rhotacism

The change of dental voiced stop to r in intervocalic positions is a regular sound change in past stems:

Rhotacism does not occur in non-intervocalic positions: bid “it was”, borče (← bord̥=še) “he carried”, začče (← zad̥=še) “he hit”, where d has become unvoiced in the vicinity of š (see §3.1), suggesting that rhotacism is a synchronic feature, with possible allophonic status. It is comparable with the intervocalic tapping of dentals in North American English: butter [ˈbʌɾɹ̩], leader [ˈliɾɹ̩].

I found no parallel to this sound change in the languages of Fārs. On the other hand, rhotacism is common in the Garmsiri vernaculars of Kermān: North Baškardi, Minābi, Hormozi, Kumzāri, and to a limited extent the inland dialects of the Halilrud valley show this feature.Footnote 24 Khargi therefore may have been infected by the vernaculars spoken around the Strait of Hormuz through commerce or migration.

2. Noun Phrase

The nominal system of Khargi corresponds to those of Southwest Iranian languages in one way or another. There are prepositions that seem particular to Khargi, including šā and ǰam (§2.3) but these do not qualify as isoglosses due to paucity of data for the neighbouring languages.

2.1. Inflection

Plural markers are -ha and -o (apparently from -hā and -ān respectively), e.g., in zenha “women”, čišo “eyes”. These suffixes are comparable with Buš. -a, while -gal prevails in the vernaculars of Fārs proper. As in Persian, the eżāfa is allowed: bāl-e domb-e gorbe “on the tail of the cat”.

Definitiveness is marked with -o, -a, and -ak(u), as in i mardo “this man”, māsta “the yogurt”, širakaku “the milk”, but is not obligatory, especially when a noun takes a personal clitic, as displayed in examples (34, 39), below. Similar markers are current in Bušehri, as opposed to commonly -u and -a elsewhere in Fārs. Indefiniteness is marked with -i/-y, usually accompanied by the numeral one, as in yak ruz-i “one day” and example (42) below. See also §4.5.

There is no case in Khargi. The accusative remains unmarked; Khargi, as many other varieties in Fārs, does not favour the Persian-type -rā, as shown in the following examples.

2.2. Pronouns

Independent personal pronouns are sg. 1 mo/me, 2 ta/to, 3 u; pl. 1 yema, 2 šemā/šoma, 3 inhe. Demonstratives are i “this”, ā “that”, hami “this very”, and hamu “that very”.

The oblique set of personal pronouns consists of the clitics sg. -m, -t, -š; pl. -mu(n), -tu(n), -šu(n), with potential connecting vowels. These clitics may either be proclitic or postclitic, especially when acting as agent in transitive past tenses (§3.6). As indirect objects the oblique pronouns are signalled by prepositions (§2.3). The clitics may act as experiencer alone (yād-šu šar-e “they have forgotten”) or when interfaced with the verb “be” in structures expressing possession and modality (§§3.8, 3.9.2).

As in Persian, the personal clitics function as possessive determinants, as in pil-me “my money” and ri-š “his face”, and can be hosted by the stem xo- to express emphasis (3) or reflection (4):

2.3. Adpositions

Khargi is entirely prepositional. Some of the Khargi preposition seem characteristic to the island or shared only with the nearby littoral communities.

A remarkable preposition is šā, as a variant to si “to, for”. The latter is frequently attested in Southwest Iranian languages, while Delvāri has both šey and sey synonymously. Examples:

(5) si-m bia “bring [it] for me”

(6) si-t hādāyah “that I give [it] to you”

(7) šā-š resi “he reached him”

(8) šā ši-š “to her husband” (JM)

(9) avem šā to boguyah “I want to tell thee”Footnote 25 (JM)

Other common prepositions are: ǰam Footnote 26 (for Pers. píše, názde) “to, by, beside”, pi (for Pers. péye, donbā́le) “after, following”, pi (for Pers. píše) “with, in the presence of”, pas “behind”, meyl “toward” (as in meyl-e čowl “toward the depression”), vo “with” (see §4.6), zi (< zir) “under”, bāl (< bālā) “over”. In the examples below propositional phrases are placed in square brackets. Note the random position of agent clitics (§3.6) at the end of the prepositional phrase (12, 14) or on the verb (13).

3. Verb phrase

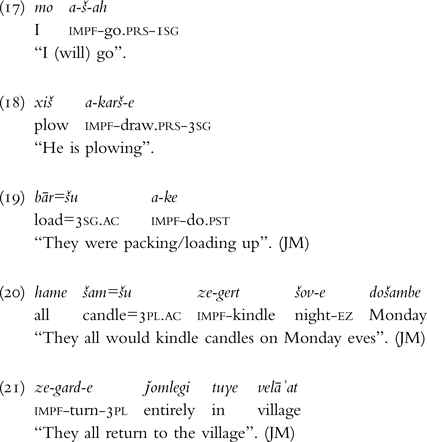

A remarkable feature of Khargi is that the imperfective aspect can be expressed with two morphemes, a-, shared by some other Southwest Iranian languages, and ze-, seemingly particular to Khargi (§3.3; Table 2, Isogloss 5). Another prefix, be-, marks the present subjunctive (§3.2). The infix -est-, a weighty isogloss in typology of the region (Table 2, isogloss 7), has low occurrence in Khargi (§3.4). The transitive past is ergative (§3.6), allowing the agent clitics to float freely within the clause.

3.1. Stems

There are two verb stems in Khargi: the present stem serving the present-future tenses in both indicative and subjunctive moods, and the past stem, employed in all past tenses. Unlike the Lārestāni and Kermān's Garmsiri groups, Khargi does not employ the past stem for present tenses (Table 2, Isogloss 6). When the stem is word-final, its final consonants may disappear: amar “he came”, ša=rof t “he swept”, če=mu kerd “what we did” (see also §1.7).

3.1.1.

Aremarkable morphophonemic feature of Khargi is that when /t/ and /š/ are joined at morpheme junctions they are perceived and therefore written as č [t͡ʃ], as demonstrated in the following examples:

(15) goče (← got=še) “he said”

gerče (← gert=še) “he seized”

arexčo (← a-rext=šo) “they used to poor”

This feature extends to the morphemic intercept d+š, in which the dental stop becomes unvoiced:

(16) borče (← bord̥=še) “he carried”

začče (← zad̥=še) or zadše “he hit”

axončo (← a-xond̥=šo) “they used to sing”

3.2. Subjunctive

The subjunctive and imperative are marked with be-,Footnote 27 as in be-guy-ah “that I say”, be-ga “say!” The subjunctive prefix is replaced with lexicalised preverbs hV- and vV-, e.g., ho-či “sit!”, hā-da “give!”, he-novis “write!”, šekār ho-kon-ah “that I go hunt”, vo-ruf-ah “that I sweep”, vā-st=aš “he seized”.

3.3. Imperfective

Khargi is distinguished by having two imperfective markers, a- and ze-. The latter, which is far more frequent in JM's material, principally marks the habitual. However, the data suggest, as demonstrated in the examples that follow, that both markers may function as both progressive and habitual with a random distribution. It is not clear which condition favours each of the two morphemes. A free distribution of the two morphemes becomes obvious for the verb “become” (§3.7).

In addition to the aforementioned imperfective markers, we also find mi-/me-, standing between the negation marker and the stem in example (22). In (23) and (24) me- seemingly co-occurs with ze-, preceding the stem *stad- or *stānd- “take”, with a possibility of me- having been integrated to the verb stem.

The marker a- connects Khargi to the Garmsiri languages of Fārs and Kermān (Table 2, isogloss 5),Footnote 29 as against the coastal dialects of Bušehr and Delvār and further north in Fārs proper, which employ mi-.Footnote 30 Its occurrence in Khargi is testimony to the mixed nature of the language.

The imperfective marker ze- is unmatched in the Iranian languages known to me. The closest morpheme I could find is Delvāri's indeclinable hasey/hey. Footnote 31 These may derive from an adverbial word—a typical source for the creation of new verbal tense and aspect markers.

3.4. Perfective

The perfect tenses are built on the past participle, which is represented by two distinct morphemes in Khargi. The prevailing form of the past participle is formed by suffixing -e/-a to the past stem and is used in the perfect tenses:

The other morpheme est- is attested only in a few sentences in the Khargi data. Most notables are:

(29) koǰ bir-est-a (for Pers. koǰā budi/budei?) “where were you?” or “where have you been?”Footnote 32

(30) key umar-est-a (for Pers. key āmadi/āmadei?) “when did you come?”Footnote 33

(31) hame az tars-e ǰen bir-est-e tarsun “they were all dreadful of the jinni”Footnote 34

The exact function of -est- cannot be discerned from these only examples. This morpheme is found in Lārestāni and a good number of the dialects of Fārs proper (Table 2, Isogloss 7). Across the strait that separates Kharg from the coastal line, Daštestāni has this morpheme but Bušehri and Delvāri do not.Footnote 35 It is hard therefore to judge whether -est- in Khargi is a recent influence from another language or a fading morpheme.

3.5. Person markers

The verb endings are suffixed to the stem in all present tenses and the past tenses of the intransitive verbs. (For the past transitive, see §3.6.) The personal endings display a certain degree of variation in the data from which the following set is inferred: sg. 1. -ah, 2. -a, 3. -e/a/i, pl. 1. -e (JM -i), 2. -e, 3. -e. The plurals are levelled due to elision of final nasals (§1.7). The endings make up for two isoglosses in Table 2.

The first singular has lost its nasal element and developed a glottal, apparently to contrast the second singular. Other Southwest Iranian languages have the general form -am (Isogloss 8), while Davāni has -e.Footnote 36

The second singular stands distinct from the rest of the Fārs varieties, who normally have a mid or high vowel (-e or -i), whereas Lārestāni distinguishes itself by the ending -eš (Isogloss 9).

The third singular present suffix -e (< *-at) has lost its final consonant. Its varying forms in the data can be a result of what Ilya Gershevitch called the “crushing” phenomena that occurs in a subset of stems found in the languages of the area.Footnote 37

3.6. Agent Clitics

The transitive past tenses employ a split ergative construction typical to many West Iranian languages (Table 2, Isogloss 4).Footnote 38 Instead of utilising suffixial person makers (§3.5) the agreement with the subject is attained via pronominal clitics (§2.2). These are designated here, in the context of verbal agreement, as agent clitics (AC).

Agent clitics fill various positions within the Khargi sentence. They are allowed to attach on the stem, either before or after it: mo=di ~ di=me “I saw”. A frequent position of the AC is on light verb components, e.g., piāda=š ke “he dismounted [it]” (see also example (2), above). AC may attach to verbal negative (32)Footnote 39 or to an overt subject, particularly in a clause initial position (33).

The most frequent position of the AC is on the object. It can be the direct object (34, 35) or indirect object (36–39). It is possible that the object itself is a pronominal clitic that is hosted by a preposition, as in (14), (37) and (38). Note also (39a), where the AC is attached to a prepositional phrase with two prepositions.

Agent clitics are obligatory; they may not be suspended in cases of same-subject verb sequences. In the following examples (b) and (c) are ungrammatical:

Clitic agents occasionally appear with non-past forms: be-xar=še “that he eat”. The limitation of this construction requires further investigation. The extension of ergativity to present tenses has sporadic evidence in the varieties spoken throughout Fārs, as well as in historical data.Footnote 41

3.7. Be, become

Copulas are the same as personal endings, with some degree of variation in vowels; the past forms are built on the stem bi-. Worth mentioning is third person singular: its present form may appear as emphatic he, which is used in existential contexts (41, 42), but as the copula it appears as clitic, e.g., či-e “what is it?” pos ke-y-a “whose son are you?” The third singular with a nasal (-en), the norm in many Iranian dialects of the south, has sporadic occurrence in Khargi data: yak man vazn-eš=ene “it weighs one maund”, corresponding to Pers. vazn dārad or vazn-aš ast; the latter structure belongs to the category of possession (§3.8). Note that possession (§3.8) and modality (§3.9) can be constructed impersonally with “be” and the personal clitic as experiencer.

The verb “become” is built on the present stem b- and past stem bi(r)-. It takes the imperfective markers a- or za- (§3.3) and the preverb vā-. Examples: ǰam abe “gather ye”, tešne zabiri “we would become thirsty”, vābe “that it become; it became”, vābire “it has become”. More data is needed to arrive at a full paradigm for this verb.

3.8. Possession

The verb “be” in accompaniment of the pronominal clitics (§2.2) function in lieu of the verb “have”.Footnote 42 In the data, the copula always follows the clitic directly, while the latter is attached to the end of the object clause. Note that in (45) the clitic is hosted by the indirect object clause pi bu-t “with your father” in order to stay next to the copula.

3.9. Modals

The verb “want” is expressed by two means, the stem ve- (< MPers. abāy-) and the impersonal eskār. They are interchangeable as far as the data reveals.

This feature forms Isogloss 11 in Table 2. The forms employed in Southwest Iranian for “want to” are various but most are derived from MPers. xwāh- : xwāst- and abāy- : abāyist-. Both forms are discernible in the Kāzerun area: Pāpuni om=xâs, Nudāni om=mies (< °vest?), Dahleʾi em=vâvi (<°vist?) “I wanted”.Footnote 44 In Lārestān the predominant form is a-vi- : a-vess-, but we also come across murky forms such as Banāruʾi madâz “I wanted”.Footnote 45 The Garmsiri dialects of Kermān have both forms, e.g., the past forms are veyt-/vâst - and xâst- in the Halilrud valley, xâst- and wâst- in Mināb, and vâst- in Bandar Abbas.Footnote 46 In coastal Fārs, near Kharg, there is Del. xâ-Footnote 47 while Dašti is reported to employ televun- : televund- to express “want”.Footnote 48

3.9.1

The present stem ve- and past stem vess-, also found in the vernaculars of Fārs and Lārestān, are preceded in Khargi by the imperfective marker (§3.3) and succeeded by pronominal clitics (§2.2); the conjugation for the three singular persons is avem, avet, aveš, neg. ney va-me/-te/-še. The dependent verb is subjunctive (§3.2):

3.9.2.

The impersonal eskār has an obscure origin. It may be formed on vess “must” (which serves also as the past stem of the verb “want”; §3.9.1) and the noun kār “deed, duty”.Footnote 49 The only other dialect known to have it is Ardakāni, spoken in northern Fārs.Footnote 50 For the third person singular the forms are: present eskār-eš-e (with contracted form: eskāš ), neg. ne-š-eskār-e, past š-eskāre bi. The pronominal clitic signifies the experiencer; thus the underlying meaning in (47) is “to me water is must”. We may analyze the same sentence in light of the possession structure introduced in §3.8, resulting in the meaning “I have need for water”. A corresponding form in Delvāri is displayed in (50). When eskār expresses modality, the verb appears in the subjunctive mood (48).

Delvāri

4. Lexis

Khargi has retained a basic stock of Iranian words. There are idiosyncratic vocabularies relevant to traditional economy, especially fishing. Some verbs of high frequency lend themselves to typological comparison within Southwest Iranian.

4.1.

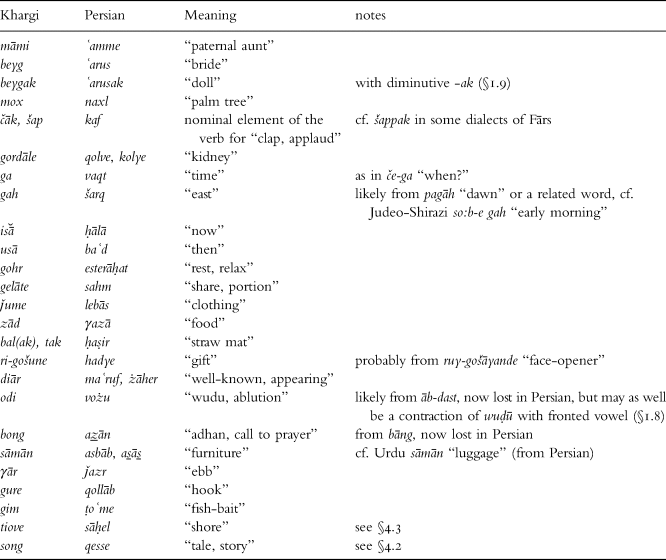

Counterintuitive to an Iranian language spoken in the Persian Gulf, the data display no preponderance of Arabic elements in the lexicon of Khargi, not any more than a typical Iranian vernacular,Footnote 53 notwithstanding frequent contacts with the communities encircling the Persian Gulf. Table 1 compares a list of Khargi words with Persian equivalents which are either Arabic loans or contain Arabic elements.

Table 1. Lexical comparison between Khargi and Persian

4.2.

song “tale” should be a contraction of *sānag, which is built on the Iranian root *sanhFootnote 54 and suffix *-aka (cf. §1.9). If so, the word is related to Parthian and Middle and New Persian afsāna(g) “story, tale”, which carries the Old Iranian prefix *abi-. A possible related word is vâsunak, the wedding songs sang by the womenfolk in Shiraz.Footnote 55

4.3.

tiove “shore” can be broken down into ti and ove. The latter consists of ow “water” (§1.5) and the suffix *-ak (§1.9). The component ti in Fārs has the meaning “end, tip”, thus possibly related to Pers. tah, Tajik tag. There are however reasons to assume that ti° has a sense of direction or destination. It can be compared with the Judeo-Shirazi preposition a-te “in, into” (author's field notes). A medieval manuscript in Kāzeruni contains the proposition <ty> with possible directional sense, comparable to Pers. az piš-e.Footnote 56 Considering the fronting of back vowels (§1.8) in all these Fārs varieties, we may as well assume that ti < tu “in, inside”. See also §4.4.

4.4.

Herte-boland is a toponym on the shore of the neighbouring Khārgu island (locally called Andar-ovi),Footnote 57 onto which the islanders used to unload their flocks for autumn graze (§6.2). It is probable that herte is made up of *ēr “low” and °te “toward” (cf. ti in §4.3), leading to the toponymic outcome “low-toward-high”, that is, the low-lying, sandy shores of the island rising toward the inner grasslands.

4.5.

toi, toy “one”, as in toi-šun “one of them”, toi-band for Pers. yek-band “uninterruptedly”. It is possibly from the classifier -tā, used along numbers to count things in many Iranian languages. The final vowel can be the indefinite marker -i (§2.1).

4.6.

vo “with” is a comitative preposition (§1.5) equivalent to and cognate with Pers. bā (< MPers. abāg). It is included in Table 2, as Isogloss 10, for its contrastive stance against certain other Southwest varieties. Lārestāni has xod.Footnote 58 The prevalent comitative preposition in Fārs proper is poy (< pay-e “following”), while there is amrey (< hamrā́he) in Davāni and vā in Kāzeruni Persian.Footnote 59

Table 2. Selected Isoglosses81

81 Legend: Cells shaded gray carry features shared by other Southwest Iranian languages. Crosshatching marks features specific to Khargi.

4.7.

čin- : čest- “sit”, as in a-čin-e “he sits”, ho-čin-ah “that I sit”, ačeste “they used to sit”. The intriguing č-initial stems are also found in the coastal dialects of Fārs (Delvāri past stem čes- and Dašti vâ-nax- : čezde-) and in vernaculars around Kāzerun: Dahleʾi and Banāfi u-či- : čes-, Davāni hū-či- : hâ-yiss-, Dusirāni ho-ni- : čas-.Footnote 60 Other Southwest languages have different forms, as shown in Table 2, Isogloss 12.Footnote 61 The Persian stems, nešin- : nešast-, derived from the proto-Iranian root *had (PIE *sed) “sit” and the prefix *ni- “down”, fused into *nišed per the RUKI sound law.

Interestingly, the č-initial stems are prevalent in northern and western Central Plateau languages: hā-čin- : hā-češt and the likes.Footnote 62 Based solely on the Central Plateau evidence, CheungFootnote 63 proposes, with reservation, the root *čaiH2 “to rest, sit down”. There is however another possibility: since in all the languages having č-initial stems for the verb “sit” there is also an original prefix *ad- (§3.3) as the imperfective formant,Footnote 64 it is likely that the č-initial stems are the outcomes of the fusion of *ad- and š-initial stems.

4.8.

The verb “go” has a suppletive set of stems in Khargi: present stem in be-ra-∅ “go!” (< *raw-), be-š-a “that he go”, a-š-e “he goes” (< *šaw-); past stem in be-šo-∅ “he went”,Footnote 65šar-e “he has gone” (< *šud-), raf t “he went” (< *raft-). Interestingly, suppletive stems are also found in the nearby coastal vernaculars but in the opposite direction: Dašti š- : raft-/-št-, Delvāri š- : raft-.Footnote 66 See the comparative list in Isogloss 13, Table 2 for “I (will) go”. Curiously the latter phrase is used as an identifier for the Lārestāni group, which is called ačemi by its neighbours (from Lāri a-č-em “I go”), and for the Garmsiri group of Kermān, which is amusingly characterised as a language of aram–nâram, contrasting to Persian miravam–nemiravam “I go–I don't go”.

4.9.

amar-, the past stem of the verb “come”, has the underlying form āmad- (§1.10). The Khargi form is thus typologically Persian, contrasting with the form and- used in Delvāri,Footnote 67 Dašti,Footnote 68 and most dialects of Fārs and Lārestān, and extends into Garmsir of Kermān.Footnote 69 The forms are listed in Table 2 under Isogloss 14.

4.10.

Khargi words characteristic to Fārs include: dey mother, bard “stone”, taš “fire”, kom “belly”, sur “salty”, muri “ant”, rešmiz “termite”, komutar “pigeon”, hā “yes”. Partial agreements and idiosyncrasies include the following.

gonz “wasp” agrees with gonǰ, common in Fārs, vs. be(n)j and bez in central-eastern Fārs and bâz in Lārestān; cf. MPers. <wpc, wpz> wabz.

kač “mouth” is common in Fārs along with kâp.

čil “mouth” is also found in Arsanjān.

lus “lip” is distinctive, vis-à-vis low and lonǰ in Fārs and loč and livir in Lārestān.

nāx “throat, windpipe” compares with naf in Arsanjān and localities to its south (cf. Pers. nāy); otherwise, goli/gori, xer, korkor, bot, boloru in the rest of Fārs.

tih “eye”, glossed by J. Āl-e AḥmadFootnote 70 with a question mark, compares well with North Lori tia and Bakhtiāri tey.Footnote 71 The main word for “eye” in Khargi is čiš.

nimešk “butter”, compares with nemešk in Evazi (Lārestān) and the Balochi dialect of Korosh spoken in Fārs; otherwise kara or the like prevails in the rest of Fārs.

širu “he-turtle” and hamas “she-turtle” stand alone vs. kâsapošt and kalapošt in Fārs.

4.11.

Old borrowings from Arabic include howdak (< ḥawż) for Pers. howz “basin”, mazǰed “mosque”, hadi (<? ḥadīṯ) “word, speech” (§6.3), ǰes (< ǰisr) “bridge”, do(w)at (< daʿwat “invite”) “(wedding) feast” (also in Hindi). Note also šambet “Saturday”, cf. earlier New Pers. šanbad < šabbaθ. The English loan gelās stands for Pers. livān “glass”.

4.12.

Some features of Khargi persist in the current Persian variety spoken on the island: mo “I”, bid “was”, pil “money”, goroxt “he fled”, diār oftād (for Pers. peydā šod) “it appeared, emerged”. A similar Persian variety was featured in the film Tangsir (1973), based in Bušehr.

5. Linguistic Position

To arrive at an approximate position of Khargi among Iranian languages, I have incorporated fourteen isoglosses, or features, that differentiate Khargi from some or all varieties spoken in Fārs and Kermān. The features are listed in Table 2. Features 1 to 3 are phonological, 4 to 9 grammatical, and 10 to 14 lexical. Isogloss 3, “louse”, qualifies as lexical as well, but it is listed as phonological for the significant role it plays in the discussion on historical sound changes (§1.2).

In order to show a meaningful and concise comparison with kindred Southwest Iranian languages, besides Khargi seven languages or language groups are listed in Table 2: (1) The group of dialects spoken in coastal districts nearest to Kharg, that is, in Tangestān and Daštestān, represented here by Delvāri and Dašti, which have received some scholarly attention.Footnote 72 (2) A continuum of dialects traditionally called the Fārs dialects, designated in this study as Fārs proper, spoken around Kāzerun and Shiraz.Footnote 73 (3) Another distinct group, the Lārestān dialects, spoken in a large area in the southeast of Fārs province.Footnote 74 (4) Adjacent to the latter, the vernaculars spoken in the vicinity of the Strait of Hormuz and extended northward to the Halilrud valley in southern Kermān, altogether designated as the Garmsiri dialects of Kermān.Footnote 75 (5) The Lori group of dialects, including Bakhtiāri, covering a large expanse in southwestern Iran.Footnote 76 (6) Persian, i.e., New Persian, which has undergone major evolution during a period well over a millennium, with grammatical features such as the imperfective marker mi- (Isogloss 5) having emerged and apparently been passed to other Iranian languages. The vast domain of Persian as lingua franca has resulted in local Persian forms, such as perfect with -est- (Isogloss 7), which is absent in mainstream Persian and thus received a negative mark in the table. (7) Middle Persian, the only language of the Middle Iranian period representing the Southwest branch of the family; during its long period of usage ergativity (Isogloss 4) eventually faded out. To this comparative table Medieval Shirazi would have been added had sufficient studies were available.

A glance at Table 2 reveals no obvious pattern as to what languages Khargi shares most features with. Isogloss 3, “louse”, a weighty distinctive feature due to unlikelihood of being a loanword, must be a shared inheritance of Khargi with the languages of Fārs shown in the table; this feature at once excludes Lārestāni as a genetic kin to Khargi. Another major feature, the imperfect marker a- (Isogloss 5), allies Khargi, in an entirely opposite direction, with Lārestāni and other Garmsiri varieties to its east, versus the Fārs groups. But there might be an explanation for this: The morpheme mi- — having been grammaticalised in New Persian as late as the 12th century,Footnote 77 most likely in the northeastern province of Khorāsān, where the language emerged as a literally medium — extraordinarily quickly diffused southwestwardly, reached Fārs, seemingly its capital city Shiraz first, as attested in historical data, then continued infecting the vernaculars along the trade route via Kāzerun and Borāzjān down to the coast, but here the expansionist wave was offset by the waves of the Persian Gulf from reaching the Kharg island.

The idiosyncrasies of Khargi are found in several features, first and foremost in verbal endings (Isoglosses 8 and 9), pointing to a substratal variance not matched with any other known variety spoken in southern Iran. Outstanding are also the doublets in Isoglosses 5 and 11. The imperfective marker ze- (Isogloss 5) seems characteristic to the island so far as the data at hand reveal — another evidence of Khargi's alienage to the dialect continuum spoken along the adjacent coast, unless we consider Del. hasey as a possible relative. As to the other doublet (Isogloss 11), the word eskār “want” is only shared with Ardakāni in northern Fārs, a variety otherwise unrelated to Khargi as expected from geographic remoteness. To the doublets we may add the triplet outcomes of Middle West Iranian*-ak in Khargi (§1.9).

A hint of contact-induced borrowing through maritime is rhotacism (Isogloss 1). Its occurrence in Khargi is limited to verb stems while it is in force in the languages spoken in islands and littoral and inland areas around the Strait of Hormuz and Bandar Abbas. Having a low density of its use, the borrower therefore should be Khargi and the lender the Garmsiri language group of Kermān, which are otherwise genetically and typologically distant from Khargi,Footnote 78 as revealed in Isoglosses 2 to 9 and 12 to 14.

The emerging taxonomy, heterogeneous as it is, is further muddled by the outcome the verb “come” (Isogloss 14) that bounds Khargi to Persian and Lori as opposed to all other major Southwest Iranian languages, may receive some justification when we turn our attention to the history of the island, which is long and convoluted and strikingly at odds with the small size and inhospitable climate of Kharg.

***

The archeological remains on Kharg are remarkable as they are witness to the island's significant maritime position between the Indian Ocean and Mesopotamia. The complexes of antiquity on Kharg include magnificent catacombs that carry architectural traits found also in the Fertile Crescent during the Seleucid and Arsacid dynastic rules. There are Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian traditions adduced from cemetery relics; a temple of likely Zoroastrian origin, later turned into a mosque; the remains of a well-equipped Christian monastery—all pointing to the importance of Kharg as a staging point for commercial vessels travelling between India and the Shatt al-Arab in late antiquity.Footnote 79

Substantive historical data only start to emerge from the Fourteenth Century, when Kharg was reported to be under the control of the ruler of Hormuz. During the Dutch East India Company's commercial activity in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries a large fort was constructed on the northwest corner of Kharg, and the island attracted traders of various nations, leading to a sizable Christian community that reached 10,000 in number at its highest point.Footnote 80

What do we make of this multifaceted, multi-ethnic setting to explain the development of the native Iranian language spoken on Kharg? The centuries long European maritime presence has left no significant linguistic trace. Had there been a Dutch-based creole formed on the island, it became extinct, as did the creoles which originated in Dutch colonies in the Americas and Southeast Asia. We find no converts that would have survived from Christian denominations possessing monasteries on the island. There is no trace of the Armenians who once had a sizable presence on Kharg in conjunction to both commerce and seminaries. Arab tribes akin to those living along the northern shores of the Persian Gulf have been reported residing also on Kharg at least since the Eighteenth Century, but we find no massive Arabic borrowing that would evince population mix. These all lead us to the conclusion that the native Iranian populations, notwithstanding their engagement in international commerce, lived their private lives in relative segregation from seemingly transitory alien communities. Subsequently, one may wish to know the roots of the Khargi aboriginals.

A key point in the sustainability of a human community on Kharg is water supply. Low precipitation supports little if any dry farming on the island. As said in the introduction, the underground water is brought from aquifers in the central foothills down to the fields by means of manmade subterranean channels called kāriz. As sustainable farming on Kharg had only been possible because kāriz assured a continuous water supply, the presence of a permanent community there cannot predate the spread of the kāriz, which came about under the Achaemenid rule in the Near East (550–330 bce).Footnote 82 Supporting evidence in Kharg might be rock graffiti with a short piece of writing in Old Persian cuneiform, which was discovered during road construction in 2007. It reads, according to a preliminary decipherment, “The not irrigated land was happy [with] my bringing out [of water]”.Footnote 83 Even though this reading has neither been confirmed nor disputed by other experts, it accords perfectly with the possible beginning of a permanent human settlement on the Kharg island.Footnote 84

The Old Persian inscription, if authentic, suggests a Persian colonisation of the island under the Achaemenids. The Iranian dialect of those settlers can very well be the ancestor of Khargi, and there is no contradicting evidence to make this hypothesis implausible. At the same time the multidirectional agreements Khargi shows with various South Iranian language groups implies polygenesis. Given the divergent historical contexts of the island, this outcome is hardly surprising. Kharg's population was surely composed in part of refugees, sailors, and skilled labourers who settled on the island individually or in groups, and new settlersFootnote 85 would have added strata to the original language. This multilayered Iranian-speaking community sustained itself by means of highly specialised skills of agriculture, purling, and piloting sea commerce before the advent of petroleum industry which changed the sociolinguistic texture of the island.

6. Texts

6.3. Proverbs:Footnote 91

âdam ke gošna-š=obi bard ham a-xo

A hungry person would eat stone as well.

ard-me bext=me, orbiz-me allâg=em kerde

I have sifted my flour, and hanged my sieve.

si kas be-merg ke si-t tow be-ger-e

Die for the one who would become feverish for you.

hadi râs az bečak ešnof-e

Hear true words from children!

nâdo ne a-don-e ne pors a-kon-e

The ignorant neither knows nor asks

Abbreviations