Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by an enduring pattern of affective instability, lack of behavior control with the specific features of impulsivity and aggression, instability in identity and self-image, instability in interpersonal relationships, and cognitive features including dissociation (Skodol et al. Reference Skodol, Gunderson, Pfohl, Widiger, Livesley and Siever2002; Bohus et al. Reference Bohus, Schmahl and Lieb2004). A dual brain pathology is assumed to account for some of the characteristic features. Both frontal and limbic circuits are thought to be affected, more specifically the anterior cingulate, the orbitofrontal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus and the amygdala seem to be involved (Bohus et al. Reference Bohus, Schmahl and Lieb2004).

Only a few studies have, with a variety of results, been concerned with the neuropsychological functioning of persons with BPD (see review by LeGris & van Reekum, Reference LeGris and van Reekum2006). Studies that consider attention mechanisms have in general not reported any differences between patients with BPD and healthy controls (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen, Herrmann, Stahl, Zwaan, Meier, Hill, Osterheider and Petersen2000; Kunert et al. Reference Kunert, Druecke, Sass and Herpertz2003; Lenzenweger et al. Reference Lenzenweger, Clarkin, Fertuck and Kernberg2004) except for the Digit Symbol task from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) (O'Leary et al. Reference O'Leary, Brouwers, Gardner and Cowdry1991; Judd & Ruff, Reference Judd and Ruff1993). Whereas some studies report reduced working memory (Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Burkhardt, Hautzinger, Schwarz and Unckel2004), others show no differences between patients with BPD and healthy controls (Kunert et al. Reference Kunert, Druecke, Sass and Herpertz2003; Dinn et al. Reference Dinn, Harris, Aycicegi, Greene, Kirkley and Reilly2004; Dowson et al. Reference Dowson, McLean, Bazanis, Toone, Young, Robbins and Sahakian2004; Lenzenweger et al. Reference Lenzenweger, Clarkin, Fertuck and Kernberg2004). When it comes to learning abilities and memory, divergent results have been reported, with reduced performance in some studies (O'Leary et al. Reference O'Leary, Brouwers, Gardner and Cowdry1991; Judd & Ruff, Reference Judd and Ruff1993; Swirsky-Sacchetti et al. Reference Swirsky-Sacchetti, Gorton, Samuel, Sobel, Genetta-Wadley and Burleigh1993; Dinn et al. Reference Dinn, Harris, Aycicegi, Greene, Kirkley and Reilly2004; Beblo et al. Reference Beblo, Saavedra, Mensebach, Lange, Markowitsch, Rau, Woermann and Driessen2006) and normal functioning on the same functions in others (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen, Herrmann, Stahl, Zwaan, Meier, Hill, Osterheider and Petersen2000; Sprock et al. Reference Sprock, Rader, Kendall and Yoder2000; Kunert et al. Reference Kunert, Druecke, Sass and Herpertz2003). Executive functions are cognitive abilities that control and regulate other abilities and behaviors. Studies focusing on BPD patients and their performance on tests measuring executive functioning show divergent results. On the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), reduced performance has been reported in some studies (van Reekum et al. Reference van Reekum, Conway, Gansler, White and Bachman1993; Lenzenweger et al. Reference Lenzenweger, Clarkin, Fertuck and Kernberg2004) but not in others (O'Leary et al. Reference O'Leary, Brouwers, Gardner and Cowdry1991). On the Trail Making Test (TMT) and the Stroop task, and also on different planning tasks, variable results have been found (Swirsky-Sacchetti et al. Reference Swirsky-Sacchetti, Gorton, Samuel, Sobel, Genetta-Wadley and Burleigh1993; Sprock et al. Reference Sprock, Rader, Kendall and Yoder2000; Bazanis et al. Reference Bazanis, Rogers, Dowson, Taylor, Meux, Staley, Nevinson-Andrews, Taylor, Robbins and Sahakian2002; Kunert et al. Reference Kunert, Druecke, Sass and Herpertz2003; Dinn et al. Reference Dinn, Harris, Aycicegi, Greene, Kirkley and Reilly2004; Beblo et al. Reference Beblo, Saavedra, Mensebach, Lange, Markowitsch, Rau, Woermann and Driessen2006). On different gambling tasks that assess decision making where response inhibition is required, reduced performance has been found (Burgess, Reference Burgess1992; Bazanis et al. Reference Bazanis, Rogers, Dowson, Taylor, Meux, Staley, Nevinson-Andrews, Taylor, Robbins and Sahakian2002; Haaland & Landrø, Reference Haaland and Landrø2007). In a recent review of the neuropsychological correlates of BPD, it was concluded that a range of neuropsychological deficits exist (LeGris & van Reekum, Reference LeGris and van Reekum2006). These findings are particularly pertinent to executive functioning.

Some methodological circumstances may account for the inconsistencies found between the different studies. Most of these studies have relatively small sample sizes, and some of the results might have been influenced by various sample characteristics affecting the external validity of the studies. The studies vary, for example, with the regard to whether differences in IQ between the patients and the controls have been reported and/or taken into account. Although IQ seem to be one of the functions that is least affected in BPD (LeGris & van Reekum, Reference LeGris and van Reekum2006), there is still a question of whether IQ differences between the BPD samples and the healthy controls may account for some of the neuropsychological differences reported.

In the present study, the neuropsychological functioning of patients with BPD was compared to the functioning of subjects without a history of mental disorders while IQ was used as a covariate. We expected patients with BPD to perform worse than healthy comparison subjects in the cognitive domains of attention, working memory, visual memory, auditory memory, and executive function but that some of the differences would be accounted for by differences in general intellectual functioning. Assuming that altered function of the anterior cingulate, the orbifrontal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus lies at the basis of some of the BPD features, we expected executive functions and long-term memory functions to stand out as deficits.

Method

Participants

This study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, and written informed consent was obtained after the subjects had been provided with a complete description of the study.

Patients with BPD

Forty-seven in- and out-patients were referred for participation in the study from different units of the Clinic for Psychiatry and Dependency Treatment at Sørlandet Hospital HF, a general hospital in southern Norway serving a population of about 265 000. To be eligible, patients had to fulfill the DSM-IV criteria for BPD (APA, 2000) and be 18–40 years old. Exclusion criteria were a history of psychotic disorder, head trauma or epilepsy, significant neurological findings, mental retardation, and ongoing substance abuse, defined as use of illicit substances during the past month. Twelve of the referred patients did not meet those criteria and the final sample consisted of 35 patients. Thirty patients were diagnosed with lifetime affective disorder: 13 in remission, 17 with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 12 with an anxiety disorder other than PTSD, 13 with another personality disorder, and seven with substance abuse. All but eight patients were taking psychotropic medications, 20 used antidepressants, 18 used antipsychotics, and 11 used mood stabilizing antiepileptic medication. For each participating patient, the fulfilled BPD criteria, co-morbidity and medication are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Criteria fulfilled for BPD, BPD severity, split GAF, current co-morbidity, age of first mental disorder, and psychotropic medication separately for each patient

BPD, Borderline personality disorder; M, male; F, female; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning Scale [split version with current functioning (F) and current symptomatology (S) assessed separately]; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; n.a., not available.

a Age when criteria for first mental disorder was fulfilled according to retrospective information.

b Fulfilled criteria for BPD; numbers refer to the criterion numbers in DSM-IV-TR.

c Severity of the BPD. Numbers of criteria fulfilled multiplied by 2 plus the number of subthreshold criteria.

d SD, substance-related disorder; MD, mood disorder; AD, anxiety disorder; ED, eating disorder; PD, personality disorder.

e AD, antidepressants; AP, antipsychotics; MS, mood stabilizers; A, anxiolytics; D, depressants; O, other.

Healthy comparison subjects

Thirty-five non-clinical comparison subjects were recruited among non-health-care employees at the hospital, students in practicum at the hospital, through newspaper advertisement, or among friends and relatives of the staff of the hospital. In addition to the exclusion criteria that applied to the patient group, selection criteria for the comparison subjects were: no history of contact with psychiatric services, no history of psychotropic medication, and no history that indicated psychiatric disorders.

Materials and procedures

Clinical evaluation

Diagnoses were established using the structured clinical interviews for DSM-IV SCID-I and -II (First et al. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1997a, Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williamsb), in addition to all available sources including electronic patient records. As an indicator of the severity of the BPD we added the number of BPD criteria fulfilled multiplied by two to the number of subthreshold criteria. Level of depression was measured with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1967). Global functioning was measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF; APA, 2000), split version (GAF-F and GAF-S). All clinical assessments were administered by an experienced clinical psychologist (V.Ø.H.). Twenty of the interviews with potentially participating patients were videotaped and the rating was repeated by an external experienced clinical psychologist who had no awareness of whether the patients were included in the study or not. The inter-rater agreement for the ratings of the nine criteria for BPD was found to be good (average Cohen's κ=0.640).

Neuropsychological evaluation

All participants underwent a battery of intellectual and neuropsychological tests administered by a test technician or a clinical psychologist trained in standardized assessment. Subjects were tested individually. The total time required for testing was about 4 h split between 2 days. The tasks were given in the same order, and testing was performed at the clinic in the same location for all subjects. The neuropsychological test battery grouped by cognitive domain is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Test battery used to assess neuropsychological and intellectual performance grouped by cognitive domain

WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Third Edition.

The Digit Symbol-Coding subtest from WAIS-III (Wechsler et al. Reference Wechsler, Nyman and Nordvik2003) and Conners' Continuous Performance Test II (CPT-II; Conners, Reference Conners2002) were used as measures of attention. The Digit Span subtest from WAIS-III, a variant of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT; Gronwall, Reference Gronwall1977), the Letter Number Span (LNS; Gold et al. Reference Gold, Carpenter, Randolph, Goldberg and Weinberger1997), and the n-back task (Callicott et al. Reference Callicott, Ramsey, Tallent, Bertolino, Knable, Coppola, Goldberg, van Gelderen, Mattay, Frank, Moonen and Weinberger1998) were used as measures of working memory. The Stroop Color-Word Test (Lund-Johansen et al. Reference Lund-Johansen, Hugdahl and Wester1996), a version of the Tower of London (TOL-4; Shum et al. Reference Shum, Short, Tunstall, O'Gorman, Wallace, Shephard and Murray2000), the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWA; Spreen & Strauss, Reference Spreen and Strauss1998), the WCST (Heaton, Reference Heaton1981), the TMT (Spreen & Strauss, Reference Spreen and Strauss1998) and the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT; Bechara et al. Reference Bechara, Damasio, Damasio and Lee1999) were used as measures of executive functioning. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised (HVLT-R; Benedict et al. Reference Benedict, Schretlen, Groninger and Brandt1998) was used as a measure of verbal long-term memory. The Kimura Recurring Recognition Figures Test (Kimura, Reference Kimura1963) and the Rey Complex Figure Test (RCFT; Spreen & Strauss, Reference Spreen and Strauss1998) were used as measures of visual long-term memory. The Vocabulary, Block Design, Picture Completion, Picture Arrangement, and Similarities subtests from WAIS-III were used as measures of IQ. The original scoring procedure was used. IQ was estimated on the basis of the pro-rated sum of scaled scores, which was computed using the sum of the scaled scores of those five subtests multiplied by 11/5 (Axelrod et al. Reference Axelrod, Ryan and Ward2001).

Data analysis

Data analysis was completed by means of SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). t tests and χ2 tests were used to compare the groups regarding demographic variables.

For the purpose of analysis, to ensure comparability between test scores, all neuropsychological raw scores were transformed into standardized scores (z transformation) using the mean and standard deviation of the comparison group. The standardized measures were grouped into five different cognitive domains and summary scores were computed. This is a common way to create composite cognitive domain scores (Saykin et al. Reference Saykin, Gur, Gur, Mozley, Mozley, Resnick, Kester and Stafiniak1991; Landrø et al. Reference Landrø, Stiles and Sletvold2001). Table 2 presents the constituent test scores in each cognitive domain.

Multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVA) were performed with diagnostic group as the between-group variable and the score on the five neuropsychological domain variables as within-subject variables. The pro-rated IQ score was entered as covariate. Follow-up analyses were conducted using ANCOVAs.

Within-subject contrasts were also performed to evaluate the selectivity of the neuropsychological deficits among the patients with BPD. The score of each functional domain was contrasted with the mean of the remaining domains using t tests for paired samples. This method has been used in prior profile analysis of patients with schizophrenia (Saykin et al. Reference Saykin, Gur, Gur, Mozley, Mozley, Resnick, Kester and Stafiniak1991) and depression (Landrø et al. Reference Landrø, Stiles and Sletvold2001).

Results

Demographic characteristics

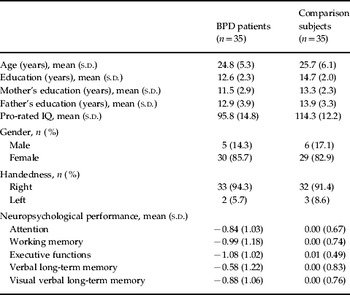

Table 3 shows the demographics and test results for the two groups, which were statistically similar in terms of age and sex ratio. BPD patients had a lower educational level [t(68)=4.152, p<0.001], and a lower educational level was also dominant among their mothers [t(59)=4.29, p=0.026] but not among their fathers [t(59)=1.18, p=0.242]. The comparison subjects showed higher pro-rated IQ [t(68)=5.71, p<0.001].

Table 3. Demographic and clinical characteristics, and neuropsychological test performance of patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) and healthy comparison subjects

s.d., Standard deviation.

Neuropsychological functioning and clinical characteristics in the patient group

No significant correlations were found between the performance on the neuropsychological domains and BPD severity, the score on the HAMD, or the score on the GAF.

To verify whether the patient group showed internal differences in neuropsychological functioning related to the presence of depression, the neuropsychological performance of the groups with (n=15) and without (n=20) a current major depressive episode was compared. Independent samples t tests revealed no significant differences between the groups in attention [t(32)=0.399, p=0.692], working memory [t(30)=0.096, p=0.924], verbal learning and memory [t(31, 35)=1.576, p=0.125], non-verbal learning and memory [t(31)=0.582, p=0.565], executive functioning [t(30)=0.293, p=0.772] or IQ [t(33)=0.173, p=0.864]. Similar results were found when we split the patient group into two following the median split procedure based on the score on the HAMD.

Given that PTSD was the most frequent co-morbid, non-affective mental disorder, we also compared the performance of the groups with (n=17) and without (n=18) PTSD with regard to the neuropsychological test performance. The independent samples t test revealed no significant differences between the two patient groups in attention [t(19.36)=1.28, p=0.217], working memory [t(30)=0.26, p=0.796], verbal learning and memory [t(33)=0.41, p=0.682], non-verbal learning and memory [t(27.9)=0.33, p=0.742], executive functioning [t(30)=0.48, p=0.632] or IQ [t(33)=0.45, p=0.444].

Those of the patients who were on any form of medication (n=27) were also compared with those who received no medication (n=8). No significant differences were found with respect to attention [t(32)=1.46, p=0.155], working memory [t(30)=0.96, p=0.328], verbal learning and memory [t(33)=1.40, p=0.171], non-verbal learning and memory [t(31)=1.19, p=0.242] or executive functioning [t(30)=1.68, p=0.103] but a significant difference was found with regard to IQ in favor of the unmedicated group [t(33)=3.00, p=0.005]. For all further analysis the patient subgroups were merged into one group.

Neuropsychological functioning in the patient group and the healthy control group

Table 3 presents the mean and standard deviation for each domain separately for the patient group and the healthy controls. Fig. 1 displays the bias corrected (Hedges' ĝ) effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals for each neuropsychological domain. MANCOVA (Wilks' λ) indicated an overall effect of the covariate IQ [F(5, 56)=17.60, p<0.001]. An overall group difference was found in neuropsychological test performance [F(5, 56)=2.72, p=0.028].

Fig. 1. Effect sizes (with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals) of the differences between the patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) and the healthy controls on every cognitive domain. LTM, long-term memory.

ANCOVA showed significant effects of IQ on every neuropsychological domain: attention [F(1, 60)=8.00, p=0.006]; working memory [F(1, 60)=52.93, p<0.001]; verbal learning and memory [F(1, 60)=24.98, p<0.001]; non-verbal learning and memory [F(1, 60)=32.40, p<0.001]; and executive functioning [F(1, 60)=49.58, p<0.001]. ANCOVA also revealed significant differences between the two groups in executive functioning [F(1, 60)=6.41, p=0.014]. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups in working memory [F(1, 60)=0.20, p=0.658), attention [F(1, 60)=3.78, p=0.057], verbal learning and memory [F(1, 60)=1.06, p=0.307] or non-verbal learning and memory [F(1, 60)=0.22, p=0.642].

The within-subject contrasts, where the mean performance of the patients on each domain was compared to the mean performance on the remaining domains, also revealed that the domain of executive functioning was a selective area of deficit (p=0.009), whereas verbal learning and memory emerged as a relative strength (p=0.007). The remaining three domains [attention (p=0.869), working memory (p=0.344) and non-verbal learning and memory (p=0.893)] were not significantly different from the mean of the other domains.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the functioning of patients with BPD on five neuropsychological domains. When controlling statistically for the effect of IQ, the patients were found to have reduced executive functioning as compared to healthy controls. We also found a tendency toward reduced attention. With regard to the other neuropsychological domains (working memory, long-term verbal memory and long-term non-verbal memory), no differences were found between the two groups. Within-subject analyses also identified executive functioning as a selective deficit among the patients whereas long-term verbal memory was identified as a relative strength. This study contributes to the understanding of cognitive functioning of patients with BPD, indicating that executive functions and possibly attention might constitute selective deficits. This is in accordance with the hypothesis that frontal circuits constitute some of the brain areas underlying BPD psychopathology (Bohus et al. Reference Bohus, Schmahl and Lieb2004). The performance on the measures included in the executive domain require the anterior cingulate (Stroop; Carter et al. Reference Carter, Macdonald, Botvinick, Ross, Stenger, Noll and Cohen2000), the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (TMT; Stuss et al. Reference Stuss, Bisschop, Alexander, Levine, Katz and Izukawa2001) and the orbitofrontal cortex (IGT; Bechara et al. Reference Bechara, Damasio, Damasio and Lee1999). The finding that verbal learning and memory emerged as a relative strength within the BPD patients is not in accordance with the expectations given that hippocampal structures are presumed to constitute one of the neurobiological substrates of BPD.

Furthermore, the study identified an association between general intellectual functioning and every neuropsychological domain. This finding is in line with what is known about the relationship between neuropsychological functioning and general intellectual functioning (Diaz-Asper et al. Reference Diaz-Asper, Schretlen and Pearlson2004). This sample presented a relatively large discrepancy between the IQ scores of the two groups, as the controls outperformed the patients by more than one standard deviation. The question therefore arises of whether group differences with regard to IQ may account for some of the inconsistencies that exist between different studies devoted to the neuropsychological functions of patients with BPD.

Examining differences in IQ between clinical and healthy control samples in studies like ours represents a theoretical and statistical challenge. To what extent such a group difference is a result of sampling error or a difference that can be accounted for by the diagnosis itself is impossible to establish. It could be argued that the development of a mental disorder such as BPD, which possibly involves both early age person factors and early age environmental factors, would also imply a reduction in intelligence. Thus intelligence could be considered a cognitive domain variable in the same way as attention, for example. Following this argument in our sample, we could have drawn the conclusion that BPD patients show reduced cognitive functioning in every domain, but this again would have been to overemphasize the difference. Another possibility would be to match the groups on IQ, but this would have overshadowed the probable reduced IQ, as a consequence of the development of the disorder. It could therefore have had the opposite result of underemphasizing the differences. We are aware that our method of statistically ‘solving’ the problem may be unsatisfactory. By using the MANCOVA there is the possibility that the removal of the variance accounted for by IQ may ‘alter’ the other cognitive constructs (Miller & Chapman, Reference Miller and Chapman2001). The results from the within-subject analysis were, however, in accordance with the results of the MANCOVA identifying the performance in the executive domain as a specific neuropsychological deficit in this sample.

The participants were tested with an extensive neuropsychological battery, where most cognitive domains were covered by several tests to obtain stable and robust measures. The creation of cognitive domains deserves particular attention. The selection of neuropsychological tests to represent different domains involves some decisions that may be questioned. Our sample was not large enough to use a factor analysis to confirm our creation of domains. In our view the most difficult differentiation concerns some of the tests involving working memory and executive functioning. These are closely related functions. Our working memory domain includes simple working memory tasks and also more complex tasks involving updating the working memory. Our executive functioning domain involves tasks requiring inhibition (Stroop, TOL), shifting (WCST, TMT), fluency (COWA) and decision making (IGT), which represents a ‘newer’ aspect of executive function. Altogether, the selected test covers most of what is considered to be executive functions (Pennington & Ozonoff, Reference Pennington and Ozonoff1996; Robbins et al. Reference Robbins, Weinberger, Taylor and Morris1996; Bryan & Luszcz, Reference Bryan and Luszcz2000), with the exception that some researchers would have included some of the working memory tests in the executive domain (Miyake et al. Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000).

We aimed for a sample of BPD patients that may be considered representative of subjects in an in-patient and out-patient setting. Given the high co-morbidity of DSM-IV axis I and II disorders in BPD (Zanarini et al. Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Dubo, Sickel, Trikha, Levin and Reynolds1998; Becker et al. Reference Becker, Grilo, Edell and McGlashan2000), co-morbidity per se was not a criterion for exclusion. A comparison between the patient groups with and without a current major depressive episode showed no differences. This is surprising because major depression is thought to be related to reduced neuropsychological functioning. For example, Landrø et al. (Reference Landrø, Stiles and Sletvold2001) found dysfunctions in attention, working memory, verbal long-term memory and verbal fluency in patients with major depression. Depressive symptoms have also been found to be related to neuropsychological dysfunctions in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder (Moritz et al. Reference Moritz, Birkner, Kloss, Jacobsen, Fricke, Bothern and Hand2001) and in patients with schizophrenia (Holthausen et al. Reference Holthausen, Wiersma, Knegtering and Van den Bosch1999). Other studies, however, have found no effect of depressive symptoms on neuropsychological performance in patients with schizotypal personality disorder. On the contrary, on some measures a positive effect of depressive symptoms was identified (Spitznagel & Suhr, Reference Spitznagel and Suhr2004).

In our sample PTSD was the most common non-affective co-morbid disorder. When comparing the two groups with and without PTSD, no differences were found in performance on any of the neuropsychological domains. For the other co-morbid disorders, no such statistical analyses were conducted because of the small frequencies. Except for current depression, co-morbidity was only assessed on the level of diagnostic categories, not on current states. Current affective states may be an important mediator in cognitive performance, at least for functions such as attention, psychomotor speed and inhibition (Domes et al. Reference Domes, Winter, Schnell, Vohs, Fast and Herpertz2006; Fertuck et al. Reference Fertuck, Marsano-Jozefowicz, Stanley, Tryon, Oquendo, Mann and Keilp2006), and affective state should be assessed in future studies.

Most of the patients in our sample were taking psychotropic medication when the tests were conducted, and no steps were taken to reduce any influences their medication might have had. When comparing the group of patients receiving any medication with the unmedicated group, no differences were found with regard to any of the neuropsychological domains, but a significant difference of IQ was found in favor of the unmedicated group. For selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), some positive effects have been found on neuropsychological performance in healthy subjects (Dumont et al. Reference Dumont, de Visser, Cohen and van Gerven2005). Atypical antipsychotics have been found to have some negative effects on attention but no effect on executive functioning in healthy subjects (de Visser et al. Reference de Visser, van der Post, Pieters, Cohen and van Gerven2001). It is therefore unlikely that medication influences could have caused the reduced executive functioning found in this study.

With the possible exception that our sample consisted of a higher percentage of female patients than the 75% that would be expected according to the DSM-IV (APA, 2000), we argue that it may be considered representative of the population of patients seen in a general clinical setting. Accordingly, inferences might be drawn from this sample to that population, but not necessarily to the patient group with BPD and no co-morbid disorders without psychotropic medication. Future studies should take the effect of co-morbidity and medication systematically into consideration.

In summary, this study reports selective deficits in executive functioning in a representative group of patients with BPD. This gives support to studies identifying frontal regions as potential neurobiological substrates of the BPD syndrome. The relative strength of the verbal long-term memory function raises questions about the presumed importance of hippocampal structures. Further studies are necessary to specify the connection between the psychopathological characteristics of BPD and the different aspects of neuropsychological functions. The question of whether current affective states mediate executive functioning should be addressed, and also whether there are subgroups of patients with BPD where reduced neuropsychological functioning is more profound, and potentially not limited to executive functioning.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants, research nurse G. Steensohn for assisting us with the data collection, and Dr T. Haaland for valuable language consultation. The study was supported by a grant from Sørlandet Hospital HF and the Southern Norway Regional Health Authority.

Declaration of Interest

None.