In June 1912, the executive board of the German Deutsch-Asiatische Bank (DAB), one of the major multinational banks operating in China, reflected on the impact of the revolution that had broken out in China during the previous year:

The year 1911 constitutes an important episode in the history of China. The Manchu [Qing] Dynasty, which had ruled since 1644, was overthrown and a republican form of constitution proclaimed. The calm observer, who had seen how the work of reform in China had progressed slowly but inexorably, stands surprised before this sudden change and hesitates to answer in the affirmative the question of whether the new government will hold together the different population groups of the large empire and bring to the country a long-lasting period of peaceful development. . . . The failure of important government functions, which was caused by the [revolutionary] movement and currently remains prominent as an unpleasant phenomenon, disturbs the order in the country, has led to the temporary drying up of regular sources of [government] revenue and has thrown capital and productive work into a state of caution, which we cannot necessarily hope will be overcome soon.Footnote 1

This statement by the German bankers reflects the insecurity and uncertainty that the Chinese Revolution of 1911 had brought to the business of multinational banks in China. Within the first wave of modern multinational banking, during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, China had become a major area of activity for multinational banks. By the end of the Qing dynasty, foreign banks could be found in most of China's major treaty ports, where they operated under extraterritoriality and were thus not subject to Chinese jurisdiction. Their business included the financing of China's foreign trade and the floating of Chinese loans on foreign capital markets.Footnote 2 For these foreign banks, the revolution was the biggest rupture China had witnessed since foreign banks had first started to enter the Chinese market in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 3 This sudden instability and uncertainty regarding China's future meant that foreign banks were confronted with a sudden rise in the political risk attached to operating and investing in China. Consequently, they needed to find ways to deal with and manage the increased political risk that resulted from the revolution. This article explores the measures taken by multinational banks operating in China to manage political risk during the 1911 Revolution and its aftermath.

Business historians have explored a broad range of strategies that multinational corporations have historically used to manage political risk, such as concealing a company's ownership.Footnote 4 However, multinational banks and the distinctively financial measures they could employ to deal with political risk have so far received little attention in the business history literature on political risk.Footnote 5 Broader studies of multinational banking have touched on how these banks dealt with political risk and uncertainty in their host countries; however, they have largely done so only in passing.Footnote 6 We therefore lack studies that explicitly and in detail study the question of how multinational banks managed political risk, including the risk associated with revolutions, and what specific financial tools they had at their disposal with which to do so.

Business historians working on political risk have paid relatively little attention to political risk management during revolutions.Footnote 7 However, examining how multinational banks dealt with political risk during revolutionary upheaval is particularly useful given that revolutions were common during the long nineteenth century, when modern multinational banking experienced rapid growth. As Jürgen Osterhammel argues, “the entire long nineteenth century was an age of revolutions.” He explains that during this age of revolutions, the Chinese Revolution was part of the “third wave” of revolutions that “washed over Eurasia after the turn of the [twentieth] century.”Footnote 8 Thus, dealing with revolutionary upheavals was an important problem and risk factor facing multinational banks during the long nineteenth century.

Recently, Hassan Malik's study of the activities of international financiers and multinational banks in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Russia and the Russian Revolution has shed some light on how multinational banks reacted to the political risk associated with revolutions. Malik describes the largely complacent, passive, and often overly sanguine attitude of international bankers toward the possible negative impact of political change and upheaval in Russia. As we will see, this stands in stark contrast to the active use of financial measures by international bankers to mitigate political risk after the outbreak of the Chinese Revolution of 1911. Especially as Malik traces this attitude of international bankers partly to perceptions shaped by orientalism that saw Russia as a Western “great power not to be pushed around by financiers” and a member of the “European family of civilized nations,” it is essential to also explore in detail how multinational banks reacted to and dealt with the political risk connected to revolutions in non-European emerging markets such as China.Footnote 9

While much research has been produced on the Chinese Revolution of 1911, its financial side and implications for multinational enterprises in China have been understudied.Footnote 10 The research that discusses the role played by foreign banks during the revolution and its aftermath at some length has been largely limited to investigating the negotiations of the Reorganisation Loan of 1913 from the perspective of Western diplomacy and imperialism.Footnote 11 In his institutional history of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC), Frank King also focuses on the loan negotiations and only mentions in passing the reaction of the London bond market and the role of the HSBC in maintaining China's credit.Footnote 12 Despite the growth of Chinese business history in recent decades, there is a lack of literature that specifically studies the management of political risk by foreign companies in China before 1914.Footnote 13

This study aims to address these shortcomings in the existing literature by tracing the strategies employed by multinational banks in China to manage political risk during the 1911 Revolution and its aftermath. As this article explains, the main concern of multinational banks was the restoration of political stability, the maintenance of China's credit abroad, and the establishment of a viable Chinese government after the revolution. This was meant to ensure that political disorder would not disrupt the banks’ business and that China could continue to repay Chinese loans the banks had floated in Europe and would remain a feasible target for foreign indirect investment. The main contribution of this article is that it provides detailed historical evidence of how multinational banks in modern China, and in non-European emerging markets more broadly, could actively use distinctively financial measures to mitigate political risk.

This article first discusses the immediate impact of the revolution on the business of multinational banks in China and on foreign bond markets. It then describes how foreign bankers attempted to maintain China's credit abroad and ensure the servicing of Chinese debt in the aftermath of the revolution. The third part returns to China and shows how foreign bankers withheld financial support for both belligerent parties in the revolution to bring about reconciliation and restore stability. Finally, the article discusses how foreign banks financed the new Chinese Republican government and contributed to restoring a certain level of stability in China.

The Outbreak of Revolution

After the Chinese Revolution broke out in Wuchang, upstream from Shanghai, in October 1911, it quickly spread throughout China. Uprisings mushroomed and military conflict ensued between the revolutionary armies and the forces of the ruling Qing dynasty.Footnote 14 Multinational banks in China's treaty ports quickly felt the impact. First, the turmoil of the revolution led to financial crisis. As the DAB reported to its supervisory board, a consequence of the revolution was runs on the Chinese banks in different treaty ports, including Shanghai, Hankou, and Tianjin, which as a result were often unable to repay their debts. In Shanghai alone, the outstanding loans made by foreign banks to Chinese banks amounted to 9 million taels (approximately £1,088,271).Footnote 15 This crisis caused many Chinese banks to close their doors and also extended to banks in the Chinese interior. In the words of the British commercial attaché in Beijing, the revolution resulted in the “whole banking system of China [breaking] down.”Footnote 16 Besides the outstanding debts of Chinese banks, their dysfunction was also a problem for foreign banks more generally, as their operation in the Chinese banking sector was dependent on cooperation with their Chinese counterparts.Footnote 17

More broadly, the business of multinational banks was also negatively influenced by the adverse effect of the revolution on China's foreign trade. The revolution and, more directly, the ensuing financial crisis inflicted a “crushing blow on the trade of China,” resulting in a “complete stagnation of trade at the end of the year.”Footnote 18 In their report to the DAB supervisory board, the German bankers immediately concluded that the negative development of China's foreign trade would adversely affect the bank's business.Footnote 19 The unstable situation in the Chinese market also had repercussions for the activities of these multinational banks outside of China. As foreign banks needed to transfer money to their Chinese branches, some faced liquidity problems in ports such as Yokohama and Kobe. Given the importance of intra-Asian trade, the revolution in China unsurprisingly also had an adverse effect on the foreign trade of Japan and Singapore, where multinational banks like the DAB were also active.Footnote 20

The immediate reaction of foreign banks to this crisis was to try to come to the aid of Chinese banks. They accepted a delay in payment from Chinese banks in Shanghai and seem to have also tried to work out a repayment plan in Hankou.Footnote 21 In the northern port city of Tianjin, foreign banks also tried to alleviate the crisis, but this effort failed because of a “complete lack of acceptable securities.”Footnote 22 In any case, these measures had only a limited effect. For example, even when the Shanghai financial market started to recover, this gave “little stimulus to trade, for the whole country was in such a state of anarchy that there was no security in transport, whilst native merchants’ whole available funds were either voluntarily or compulsorily offered in support of the popular revolutionary cause.”Footnote 23 As the British commercial attaché in Beijing wrote, “the country everywhere had become so unsettled that neither goods nor money could be moved freely.”Footnote 24 Clearly, the larger problem was that the instability following the revolution had paralyzed the country and only a return to stability with a legitimate government in place could solve the crisis. Accordingly, the North-China Herald opined in November 1911 that the “entire responsibility for the existence of the abnormal trade conditions rests upon the political situation. What is urgently wanted is peace and government in the country, without which commerce cannot be resumed.”Footnote 25 Naturally, this was also in the interest of foreign banks.

However, despite the disastrous state of Chinese commerce after the revolution, the greatest concern of foreign bankers at that time was the performance of Chinese bonds in Europe and the maintenance of China's credit abroad. Faced with a fiscal crisis, China had during the nineteenth century begun to resort to foreign loans to raise funds and borrowed foreign capital from Western merchants and banks. Consequently, providing loans to the Chinese government became an important part of the business of foreign banks in China.Footnote 26 Starting in the 1870s, mainly with the help of the HSBC, China also began to issue public loans on European bond markets.Footnote 27 Subsequently, Chinese foreign borrowing increased dramatically and China developed a reliance on foreign loans. At the same time, its financial problems and deficit grew, so China was bound to need further foreign loans if it faced any emergencies that required large sums of money.Footnote 28 In 1911, London and Berlin were the biggest markets for the trade in Chinese bonds.Footnote 29 Thus, this section and the following section pay particular attention to the actions of British and German bankers. In the years before the 1911 Revolution, Chinese bonds had performed well in London and Berlin and were always traded either at a premium or only slightly below par.Footnote 30 This favorable credit had enabled China to borrow large sums of foreign capital abroad.

News of the uprising in Wuchang reached Britain on October 12, 1911, and “brought a feeling of uncertainty over the [bond] market” in London.Footnote 31 In Berlin, investors also grew concerned about the situation in China and soon the topic that “received most of the attention” at the bourse was “the news about the uprising in China” indicating “that the danger [created by] the revolutionary movement is greater than previously expected.”Footnote 32 Newspapers in London and Berlin continued to inform investors of the course of events in China and increasingly reported on “the progress made by the rebels” and “the sympathy with which the rebellion is regarded throughout China.”Footnote 33 The Berliner Börsen-Zeitung, a newspaper published specifically for German investors, reported on the situation in China and expressed worries that a “civil war [between the government and the revolutionaries] appears to become more and more likely.”Footnote 34 There were also more positive reports that “the Chinese troubles will soon come to an end.”Footnote 35 Nevertheless, there existed a general anxiety about the political instability in China. The uncertainty on the bond markets led to a price fall of some “Far Eastern stocks . . . on account of the Revolution.”Footnote 36 Figure 1 shows the price development of China bonds in Britain and Germany immediately after the revolution using the example of the two large Chinese indemnity loans floated in 1896 and 1898. As we can see, between October 7 and November 30 the price average of these bonds decreased from 102.125 percent to 97.75 percent in Britain and from 100.4 percent to 96.65 percent in Germany.

Figure 1. Price of British and German China bonds, October 7, 1911, to November 30, 1911. (Sources: The Economist, October 7, 14, and 21, 1911, November 11, 18, and 25, 1911; Investor's Monthly Manual, October 31, 1911, November 30, 1911; and Berliner Börsen-Zeitung, October 7, 14, 21, and 31, 1911, November 11, 18, 25, and 30, 1911.)

This volatility in the price of Chinese bonds was a concern not only for bondholders but also for multinational banks like the HSBC and the DAB, which had underwritten and floated loans for the Chinese government in Europe in the past.Footnote 37 A worsening of China's credit could damage their reputation as underwriters of Chinese loans.Footnote 38 Naturally, it would have also threatened the floating of future Chinese loans, which represented an important part of the business of these banks. Given the reliance of the Chinese government on foreign borrowing, any new regime that could restore stability in China for Chinese commerce would most likely depend on the ability to continue to borrow foreign capital. As King argues for the HSBC and its loan business more generally, foreign bankers also had an interest in protecting China's credit due to a feeling of responsibility toward existing bondholders, the bankers’ own investment in Chinese bonds and a long-term business interest in financially supporting Chinese economic growth.Footnote 39

The greatest fear of these bankers was that China would default on its loans. Charles Addis, London manager of the HSBC, believed that “even a temporary failure of the [Chinese] Government to meet its obligations” would have had a serious impact on China's credit.Footnote 40 Although these foreign banks still held limited funds to the credit of the Chinese government, at the end of 1911 the first payments of foreign loans fell due without payment having been arranged by the Chinese government.Footnote 41 Thus, there existed the serious threat of a full Chinese sovereign default. The concerns grew further, when news appeared in late October that the revenues of the Chinese government from the Yangzi provinces, which “contributed the greater portion of money required for monthly remittances” for the servicing of loans, had stopped flowing.Footnote 42 Furthermore, in November 1911 some rebels abolished the lijin, a trade tax, which had been pledged as guarantee for several loans.Footnote 43 The political developments in China had not only affected the business of foreign banks on the spot in China but also increased the political risk of those multinational banks that had underwritten Chinese bonds and for those investors that owned Chinese government bonds. Clearly, this new situation had to be managed somehow in Europe until things calmed down in China and stability would be restored.

Maintaining China's Credit Abroad

The first measure taken by foreign banks to mitigate the impact of the revolution on Chinese bonds was that they pledged to pay the interest payments on Chinese loans should there be delays in Chinese payments. This strategy was first fixed during an international banking conference held in Paris on November 8, 1911, with French and American bankers with whom the HSBC and the DAB had formed a consortium for issuing Chinese loans in 1910. Known as the Four Power Groups (or Four Groups) consortium, it constituted the most powerful foreign financial consortium in China.Footnote 44 At the conference, the problem of “coupons [of Chinese loans] falling due was discussed and there was no difference of opinion among the Groups that such coupons should be protected as far as possible and that all Groups should arrange the matter in the same way.”Footnote 45 As Addis later explained, the understanding of the Groups was that the bankers would “take common action for the protection of these coupons by paying the money themselves.”Footnote 46 Thus, the bankers were essentially pledging their own money to maintain China's credit.

As the 6 percent 1895 Gold Loan floated by the HSBC in London was due first, the HSBC was the first bank to issue a statement that it would purchase the coupons for this loan.Footnote 47 The Nationalbank für Deutschland, which had floated a Chinese loan in Germany in 1895, also soon pledged to pay for the coupons that became due.Footnote 48 When payments for the 1898 indemnity loan were about to be due, the Konsortium für Asiatische Geschäfte (KfAG; Consortium for Asiatic Business), which united the interests of more than a dozen German banks in China and was connected to the DAB, pledged to pay both the coupons and drawn bonds due, as the HSBC now had also agreed to pay drawn bonds as well.Footnote 49 British banks and syndicates other than the HSBC, such as the Chartered Bank and the Peking Syndicate, also paid interest coupons for due bonds. According to the secretary of the Peking Syndicate, this was done to avoid the “disastrous effect” that a Chinese failure to pay its debt would have “on all Chinese Government securities.”Footnote 50 Thus, these banks pledged their own money during the months following the revolution to avert a Chinese failure to service its debt and to maintain China's credit, although it was unclear if and when a stable Chinese government that could repay them would be established.

While the banks were willing to put forward their own money for the time being, it soon became clear that a long-term solution for guaranteeing the payment of Chinese bonds needed to be found. As Edward Hillier, the Beijing manager of the HSBC, put it, the “gravity and uncertainty of [the] situation have so increased since [the] Paris Conference” in November that the banks could not “prolong indefinitely” their pledge of paying for interest.Footnote 51 For the time being, discussions of both British and German bankers focused mainly on securing the customs revenue under control of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, a foreign-led Chinese government agency headed by British Inspector General Francis Aglen in Beijing. A significant number of Chinese loans were hypothecated on customs revenue.Footnote 52 Therefore, the second measure that bankers took to maintain China's credit was to work with Aglen to secure the customs revenue for the servicing of Chinese loans. As early as October 14, 1911, Aglen had started devising plans to deposit customs revenue at the HSBC to secure this revenue from the revolutionaries and ensure the repayment of foreign debt. In December 1911, he ordered the customs commissioners, who until then had exercised no control over the revenue, to assume that control.Footnote 53 The Chinese government had initially planned to ask for “deferring the payment” of the Boxer indemnity, which in October had been the first payment due to be paid from the customs revenue to a foreign party, but as this “would have ruined [China's] credit” the Chinese officials decided to “fulfil the payment as usual” and, agreeing to Aglen's plan, “instructed [him] to place into foreign banks the whole amount of the customs revenue, which will be used to pay the indemnity and foreign loans” hypothecated on customs revenue.Footnote 54

In November 1911, the foreign banks in Shanghai proposed the establishment of a commission consisting of those banks whose countries received parts of the Boxer indemnity, which was not a loan but also hypothecated on customs revenue. This commission was to elect an executive commission consisting of the HSBC, the DAB, and the Russo-Asiatic Bank. The inspector general was to remit the customs revenue to these three banks every week to repay those loans guaranteed by customs revenue; the remaining surplus would then be used for the repayment of the Boxer indemnity starting at the end of 1912.Footnote 55 Franz Urbig, the head of the supervisory board of the DAB, agreed with this proposal and wrote to Addis that he considered it “very reasonable” and stressed that not only was “mak[ing] effective the security given by the maritime customs” the banks’ “duty towards the bondholders” but safeguarding it was also necessary for the “protection of [the] issuing credit” of the banks.Footnote 56 By the end of December, diplomatic support for this measure was also forthcoming.Footnote 57 In January 1912, an International Commission of Bankers was established. From then on, the customs revenue was transferred in equal amounts to the HSBC, the DAB, and the Russo-Asiatic Bank to ensure the repayment of China's foreign obligations.Footnote 58

In London, Addis published a telegram by Aglen in the Times that confirmed the establishment of the commission and the safety of the repayment of Chinese loans secured by customs revenue. Addis was certain this would “hardly fail to have a reassuring effect upon the holders of Chinese bonds.”Footnote 59 He continued to publish reports on customs funds received by the foreign banks to reassure investors.Footnote 60 German bankers do not seem to have used newspapers in the same way to publicize the commission's establishment, although news of it would have reached Berlin. For the German consortium, the main advantage of the establishment of the commission was that it could reduce its guarantees for the payment of loans floated by the DAB, as at least the servicing of those loans secured by customs revenue was now ensured.Footnote 61 In both the British and the German cases, the arrangement the foreign bankers concluded with the Customs Service and the foreign diplomats had a reassuring effect for investors and provided a long-term solution for the servicing of a large part of the Chinese loans, thereby also maintaining China's credit.

Besides these two measures, the German bankers took a further step to deal with the increased political risk for investors and to maintain China's credit. They pooled money to actively intervene in the bond market in Berlin and buy up Chinese bonds to stabilize their price, especially for those bonds not secured by customs revenue. It is unclear whether British banks took similar measures, but unlike the HSBC or the Chartered Bank, the German banks united in the KfAG possessed such large capital power that they were able to pool enough money easily without putting any single member of the consortium at too much risk. After the 1911 Revolution broke out, German bankers started to buy up Chinese bonds on October 14.Footnote 62 Two days later, bankers of the Disconto-Gesellschaft and the Deutsche Bank, both members of the KfAG, met at the Berlin bourse and agreed that a consortium was to be established to purchase bonds for the purpose of “price regulation” of Chinese bonds. The costs were split among the consortium banks.Footnote 63 On the following day, it was decided to extend the consortium to all the members of the KfAG, as there was a possibility that the volume of the “intervention purchases [Interventions-Käufe]” could increase further.Footnote 64

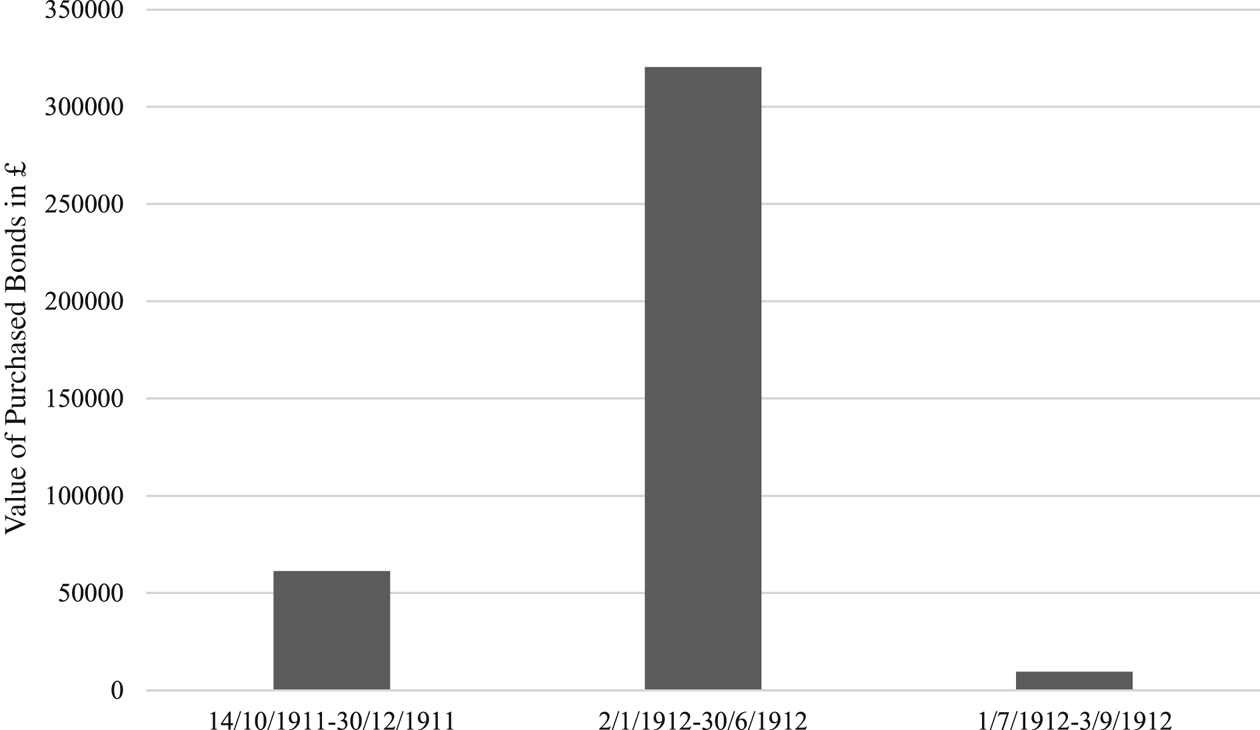

As Figure 2 shows, in 1912 the consortium bought up a large number of Chinese bonds to increase demand in the market and prop up the price for those bonds. It needs to be pointed out that the consortium not only purchased but also sold bonds at the same time.Footnote 65 Figure 2 shows the total volume of purchases rather than the consortium's balance of payments. While purchases remained limited to only £61,260 between October and December 1911, they rose sharply to a total of £320,375 in the first half of 1912. This sum eventually decreased to only £9,460 in the last months before the consortium decided in December 1912 that further purchases were unnecessary for the time being.Footnote 66 The correspondence of the consortium contains no specific information on the direct impact of the purchases on bond prices; however, the fact that the consortium continued to carry out large intervention purchases throughout the first half of 1912 suggests that they believed purchases were necessary to stabilize bond prices until then.

Figure 2. Chinese Bonds purchased by German consortium, October 14, 1911, to September 3, 1912, in £ (Source: Relevant tables in S2606, Historical Archive of Deutsche Bank, Frankfurt am Main).

If we look at the overall performance of Chinese bonds on the London and Berlin markets from 1910 to 1914 (provided in Figure 3 and Figure 4), we can see how the measures taken by the bankers were reflected in the performance of Chinese bonds. Chinese bonds are divided into two samples of bonds traded in both London and Berlin. One consists of the two Anglo-German indemnity loans of 1896 and 1898, both secured by revenue collected by the Maritime Customs Service run by foreigners, and the other comprises three railway loans not secured by customs revenue or any other revenues under foreign control.Footnote 67 The two graphs (Spread I and Spread II) show the spread between the two samples of Chinese bonds and British consols and German sovereign bonds, respectively, thereby demonstrating how the Chinese bonds performed in relation to the overall development of the markets.Footnote 68

Figure 3. Spreads of British China bonds (current yield), January 1910 to July 1914. (Source: Investor's Monthly Manual, 1910–1914.)

Figure 4. Spreads of German China bonds (current yield), January 1910 to July 1914. (Source: Berliner Börsen-Zeitung, 1910–1914.)

From the two figures we can see that overall yields for Chinese bonds remained stable throughout the Revolution of 1911 and its aftermath. Clearly, the measures taken by the bankers in London and Berlin were effective in limiting the impact of the increased political risk in China on European bond markets and in preventing any large-scale fluctuations in bond prices. The bankers succeeded in maintaining China's credit and mitigating the impact of the revolution and the increased political risk for investments in China on foreign bond markets. The stability of Chinese bond yields during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has been noted before and simply traced to risk being limited through continuous foreign control of Chinese revenues.Footnote 69 However, this section has shown the importance of bankers in maintaining this stability during and after the 1911 Revolution. The two figures also show that Chinese bonds with and without foreign control of Chinese revenues had performed similarly before 1911. Only after the revolution does there seem to have been a slight divergence in bond yields between the two groups of bonds, indicating that investors to a certain degree lost confidence in bonds secured by revenues without foreign control. As we will see, the overall stability of bond yields achieved by the foreign bankers allowed China to continue to raise capital on foreign markets and thereby keep the new republic afloat.

Foreign Capital and the Transition from Empire to Republic

With the impact of the revolution on foreign bond markets mitigated for the time being, the foreign banks active in China were still confronted with the necessity of restoring stability in the country so that China's commerce could recover. While the bankers’ ability to intervene in the Chinese political process was naturally limited, they successfully employed the leverage they held over the supply of foreign capital—which both belligerent parties desperately needed—to bring about a quick agreement between the belligerents, ending the internal conflict and its impact on Chinese commerce.

As early as October 1911, the Qing government asked the Four Groups for an advance of 12 million taels (approximately £1,451,028). The HSBC in Beijing felt that the “groups should entertain [the] proposal” if Yuan Shikai “returns with full powers,” believing that his return would mean the “government will be able to cope with [the] revolution.”Footnote 70 This sympathy for Yuan, a former Qing official dismissed by the Qing in 1908 but reinstated as prime minister in November 1911 to fight the revolutionaries, was already indicative of the later support for him by foreign bankers. However, at the time, HSBC director A. M. Townsend in London was opposed to such a loan, deeming it “undesirable and impolitic.”Footnote 71 In Germany, the KfAG agreed that the banks should remain neutral and not provide any loans to the Chinese government to fight the revolutionaries. However, they were open to providing the Chinese with loans that allowed China to continue previous loan payments, which again reflected the importance the bankers attached to maintaining China's ability to service its loans.Footnote 72 Nevertheless, the Four Groups eventually decided that they were “not opposed to making [a] loan to a responsible Chinese Government” but given “the present uncertainty of the situation [were] not disposed at present to entertain application for financial assistance,” thereby essentially declaring their neutrality in the conflict.Footnote 73

Besides the general uncertainty in China, we can discern two reasons why the bankers remained neutral. First, openly supporting either side financially would have come with the risk of upsetting one side or losing favor in China more generally. This was especially the case given that both the Qing government and the revolutionaries had issued admonitions to the foreign representatives that they should prohibit any foreign lending to the other side in the conflict.Footnote 74 Addis noted that the revolutionaries had so far spared foreign life and property but that siding with their opponents might lead them to end this stance and to “anti-foreign feeling” and “disorder.”Footnote 75 Urbig also believed that as long as no agreement between the belligerents had been found, “it may easily happen that it will be taken amiss in China that the Four Groups have sided with a certain party.”Footnote 76

However, an arguably even more important reason was that the refusal of any direct financial support forced both parties to come to an agreement, thereby clearing the way for the reestablishment of a viable government and stability in the country. As Addis explained, providing financial support to Yuan might “only harden his heart and make him more inclined to be uncompromising.” In contrast, Addis felt that “the diminishing financial resources of the two contestants [resulting from no access to foreign borrowing] in itself [might be] an incentive to a compromise being arrived between them.”Footnote 77 His HSBC colleagues in Shanghai also feared that financial support of Yuan would “almost certain[ly] result in anti-foreign movement” that would be detrimental to foreign residents and trade. They agreed that the “solution of trouble will be effected sooner by withholding financial support from both sides.”Footnote 78 This sentiment was shared more widely. W. M. Koch of the well-known stock brokerage firm Panmure Gordon & Co., which had before been involved in the floating of Chinese loans in London, viewed the groups’ decision to “refuse all pecuniary help to both parties” as “wise.” Like Addis, Koch felt that the “difficulty, if not the impossibility, of [both parties] raising any money may perhaps help towards a compromise.”Footnote 79 Thus, the refusal to provide financial support to the two belligerent parties must be seen as a way of mitigating the risk of both antiforeign repercussions and, more importantly, prolonged civil conflict and disorder.

By the end of 1911, the Qing's financial problems had still not been resolved and Yuan was worried that the government's inability to pay its troops might lead many of them to turn into bandits and cause further turmoil.Footnote 80 In a letter to the governor-general of the three northeastern provinces, Zhao Erxun, Yuan complained that no foreign loan was forthcoming and indicated that the court now wished to come to an agreement with the revolutionaries, as the military campaign against them could no longer be supported financially.Footnote 81

Just as the Qing government tried to raise funds through foreign borrowing, the revolutionaries also tried to win financial support. When revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen, who had been in the United States, heard revolution had broken out, he did not immediately return to China but first made stops in London and Paris to gain foreign support.Footnote 82 There, Sun also tried to win over foreign financiers for his cause. In London, he approached the HSBC about financial assistance, but the British bankers were not willing to help before a proper Chinese government was established.Footnote 83 Sun also tried his luck in Paris, but the director of the French Banque de L'Indochine explained to him that the Four Groups—of which his bank was a member—had decided to remain neutral.Footnote 84 Sun firmly believed that “victory or defeat [against the Qing government] is decided by [foreign] loans.” Reflecting on his failed attempts to gain financial support in Europe, he recognized the main problem as the reluctance of foreign lenders to financially support the new republican government, as it was so far only a temporary government not recognized by other states.Footnote 85 Eventually, both Yuan's admission that the Qing lacked the funds to continue fighting and Sun's realization that only a proper government recognized by other states would be able to borrow the needed foreign capital on a large scale suggests that the neutral position taken by foreign bankers was an important factor in bringing the two belligerents to the negotiating table.Footnote 86 After peace negotiations between the revolutionaries and Yuan, the Qing emperor abdicated in February 1912; after just over four months, the revolution ended and Yuan emerged as the provisional president of the new Chinese republic. Thus, by maintaining neutrality during the revolution the bankers had successfully managed to mitigate the risk of possible prolonged civil war and opened up the road to a new unified government that could restore long-term stability.

Financing the New Republican Government

Even though a compromise between the belligerent parties had been reached, only a new stable government could guarantee a restoration of long-term stability. After the abdication of the Qing ruling house and the transfer of power to Yuan Shikai, contracting a large foreign loan became an important element of Yuan's presidential program.Footnote 87 He could count on the support of the foreign bankers, who early on had seen him as the person capable of restoring stability.Footnote 88 In Berlin and London, newspapers welcomed that Yuan was taking charge of the government and were hopeful that stability could now be restored.Footnote 89 Given the bleak financial situation the government found itself in, it was not surprising that foreign loans became the basis for any other plans the government might have. According to an estimate by Xiong Xiling, who served briefly as Minister of Finance in 1912, the annual deficit of the new government would be around 178 million taels (approximately £24,260,597) owing to the existing deficit of the Qing government and administrative and other expenses.Footnote 90

Yuan approached the Four Groups in February 1912 about a possible loan. He required 7 million taels (approximately £954,068) for the disbandment of troops and the costs of the retiring Nanjing government. Moreover, Yuan asked for 3.4 million taels (approximately £463,405) a month for the requirements of the central government and a further 3 million taels (approximately £408,886) for the expenditures of the rest of China.Footnote 91 He hoped that such monthly payments could continue at least until August and that eventually a larger loan could be secured to repay the advances made by the Four Groups and provide a financial basis for the establishment of the new republic.Footnote 92 Regarding this larger loan, Tang Shaoyi, then premier of Yuan's government, inquired on behalf of the Chinese government about a £60 million loan spread over five years and secured by the salt revenue. This sum was to be used first for debt and indemnity payments and then the remainder split “in proportion [of] 80 per cent [for] productive works [and] 20 per cent [for the] army, navy, and education.”Footnote 93

Now that a united Chinese government was again in place, the bankers were willing to support it financially and extend the required advances. They proposed that the Chinese government should issue treasury bills to the Four Groups as collateral for the advances made; these could then be redeemed from the proceeds of a large reorganization loan.Footnote 94 However, the banks also attached conditions to their financial assistance. The bankers saw the loan as a chance to push China toward financial reform. British and German bankers hoped that a part of the proceeds from the large loan could be used for fiscal reform and infrastructure expansion.Footnote 95

Naturally, the bankers were also concerned with their future bondholders and were willing to provide funds only if China could provide the “necessary guarantees.”Footnote 96 The last years of the Qing dynasty had seen a readiness by foreign bankers to accept streams of revenue not under foreign supervision as security for loans and to leave control over loan funds to China.Footnote 97 However, this changed with the political instability that ensued after the revolution and the consequential increased political risk that investment in Chinese government bonds would carry. Even after the establishment of a provisional government, the representatives of the Four Groups in China reported that China's public finance was in a very serious state, “much more serious, than [the Four] Groups or ourselves previously realized,” and, except for customs revenue, “practically no revenue” was being collected.Footnote 98 The representatives feared that “China will ruin herself unless she is taken in hand properly.”Footnote 99 While the Four Groups accepted the salt revenue as security for the large loan, they demanded that “the Chinese Government shall take immediate steps to reorganise the Salt Gabelle, with the assistance of foreign experts [and] [a]dequate guarantees shall be obtained for the control and supervision of the expenditures of the Loan proceeds.”Footnote 100

The bankers were also concerned about the ability of European markets to absorb such a large loan, especially given that China had previously already used part of its salt revenue as security for loans. Addis believed that “the Chinese are opening the mouth wide. For a nation which has recently been in default with its loan coupons to propose a loan of £60,000,000 against a second mortgage security is enough to stagger, if not humanity, at least the European markets.”Footnote 101 The directors of the DAB were convinced that “we will not find new investors for [the] Chinese loan unless they can realise [the] efficiency of [the] guarantee given for such a loan.” Such an efficient guarantee would be the “salt gabelle, to be reorganised under foreign experts.”Footnote 102 Thus, all these demands reflected the bankers’ intention of encouraging Chinese fiscal reform and responsible spending and ensuring the successful floating and repayment of the loan.

In principle, Yuan agreed to the reorganization of the salt revenue with the help of foreign experts and to foreign assistance “in inaugurating [a] modern system of accounts and [the] framing [of a] budget,” which would have ensured the appropriate expenditure of the loan funds.Footnote 103 Thus, the banks agreed to fund the expenses of the Chinese government until the conclusion of the reorganization loan. By the end of May, the banks had already advanced 6.1 million taels (approximately £831,402) to the Chinese government and estimated that until October the Chinese government would require advances totaling £10 million.Footnote 104 The negotiations eventually dragged on until April 1913. This period saw the entry of a Russian and a Japanese group into the consortium in June 1912 and the exit of the American group after the election of Woodrow Wilson. Eventually, the Reorganisation Loan agreement was signed on April 26, 1913. The loan sum had been reduced to £25 million.Footnote 105 According to the loan agreement, a new Central Salt Administration was to be established, which was fully under the control of the Chinese Ministry of Finance. Foreign control was limited to a foreign associate chief inspector, who was to manage the Salt Administration together with a Chinese chief inspector.Footnote 106

Given the still large amount of money that China required, and the near failure on its loan payments to bondholders that China had witnessed, it was surprising that the bonds were initially floated successfully in Britain, Germany, France, Russia, and Belgium.Footnote 107 However, in London the bonds at first fell to 54.5 percent below par by the end of July 1913. While the London price recovered in August, in both Germany and Britain the bonds soon stagnated around the issue value of 90 percent below par and remained clearly below the average of the indemnity loans of 1896 and 1898, which had a security similar to that of the Reorganisation Loan (see Figure 5). Given the divergence in the performance of bonds after the revolution observed above, the Reorganisation Loan would most likely have performed even more poorly without a foreign-controlled security. Thus, the bankers had not been wrong in insisting on a good security. The weak performance of the Reorganisation Loan bonds also showed that a bond issue of this size would most likely not have been possible had the bankers not maintained China's credit in Europe and thereby limited the impact of the heightened political risk on bond prices during the months following the revolution. Only the previous actions of the bankers enabled China to raise this large amount of money abroad and keep the new government afloat.

Figure 5. Reorganization loan bond prices (Berlin/London), July 1913 to July 1914. (Sources: Investor's Monthly Manual, July 1913–July 1914; Berliner Börsen-Zeitung, July 1913–July 1914.)

The Reorganisation Loan played an important role in Yuan's consolidation of power and his quick victory against an upheaval by several southern provinces in 1913.Footnote 108 Thereby, the actions of the bankers, this time in the form of financial support for the new government, once more prevented any prolonged interior conflict. The loan also allowed the government to continue servicing its debt, resume basic administrative functions, and initiate reforms for the strengthening of the central government. According to the German bankers, this all had a positive impact on the Chinese economy—despite the negative impact of the upheaval of the southern provinces.Footnote 109 Evidence from Tianjin suggests that the reorganization loan eased the money market and thereby helped trade.Footnote 110 More broadly, the limitation of civil conflict had a positive impact on China's foreign trade. As Figure 6 shows, after the growth of China's foreign trade had stagnated in 1911, it recovered in the following two years. Undoubtedly, the quick reestablishment of a new Chinese government, induced by the foreign banks’ withholding of financial support, and the funding provided to the new government had played an important role in making both a return to stability and this economic recovery possible. In the aftermath of the revolution, the foreign bankers had managed to maintain China's credit, ensure the continuous payments to bondholders of Chinese loans, help bring about a quick resolution of civil disorder and conflict, and restore stability. Thus, the strategizing of the multinational banks throughout the revolution shows how multinational banks could use their limited capabilities to mitigate the impact of major political upheaval like the 1911 Revolution on their business and the business environment in emerging economies more broadly.

Figure 6. Gross value of the foreign trade of China in £ (not including value of goods carried coastwise), 1909 to 1913. (Source: Foreign Office and Board of Trade, Report for the Year 1913 on the Foreign Trade of China [London, 1915], 26.)

Conclusion

This article has traced how multinational banks in China managed political risk during the Revolution of 1911 and its aftermath. I have shown that these banks used distinctively financial measures—namely the maintenance of China's credit abroad, through the use of the banks’ own resources and cooperation with Chinese government institutions, and the control of the supply of foreign capital to China—to influence political and economic developments in such a way that helped to manage the political risk after the outbreak of revolution. The 1911 Revolution shows that bankers, as opposed to other multinationals, were in a particularly favorable position for mitigating political risk in emerging markets reliant on foreign capital because of their connections to foreign bond markets and their role as the main providers of such capital. These two advantages allowed them to maintain a country's credit, curtail civil conflict, and support the establishment of a new government during political crises.

Studying the strategies for the management of political risk adopted by multinational banks in a non-European emerging market like China also allows for comparison with their behavior in a European context. As mentioned above, Malik shows that in the case of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Russia, multinational bankers exhibited a certain complacency and passivity with regard to political risk, partly owing to Russia being a European country. In contrast, we have seen that multinational banks in China were willing to take immediate active measures to mitigate political risk and even use their control over the supply of foreign capital to intervene in the political process. Additional case studies of political risk management by multinational banks would be necessary to arrive at a typology of risk management of such banks in different countries during revolutions. However, this comparison already suggests that multinational banks operating on the periphery of the global economy not only were more responsive to heightened political risk but also understood their role in resolving and limiting the impact of political upheaval to mitigate political risk as much more active than in Europe. These differences in the behaviors of multinational banks in European and non-European contexts once again shows the importance of studying business history—in particular, how businesses reacted to political instability—in non-European emerging markets.Footnote 111

Beyond the realm of multinational banking, the findings of this article contribute to the risk management literature in business and financial history more generally. First, when discussing political risk management strategies by multinationals that took the form of intervention in a country's political process, business historians have so far focused mainly on the post–World War II era.Footnote 112 However, the case presented here suggests that already in the early twentieth century multinational banks were willing to use the withholding and supply of foreign capital to influence political processes in their host country to manage political risk. Second, the financial measures that multinational banks could take to mitigate political risk during revolutions also are a new addition to the repertoire of financial risk management techniques of banks more generally that financial historians have begun to study.Footnote 113

While this article has showcased the financial measures that multinational banks in non-European emerging markets could take to mitigate political risk, it needs to be pointed out that the long-term political development of China after the 1911 Revolution also shows that there existed important limitations to the ability of multinational banks to manage political risk and influence the larger political developments in their host countries. While the bankers’ financial support allowed Yuan Shikai to establish a new government, this neither changed Yuan's inability to solve the larger fiscal and military problems that the Qing rulers had left him nor prevented his government's eventual failure.Footnote 114 The bankers succeeded in mitigating the immediate political risk that followed from the Revolution of 1911, but, in the end, it only delayed China's political disintegration until after Yuan's downfall and death in 1916.