A large body of research identified, and then sought to explain, the tendency for democracies to win wars. The effect is large—democracies win almost all the wars they start and about two-thirds of the wars in which they are targets of aggression (Reiter and Stam 2002). While democratic victory has achieved the status of conventional wisdom, the field continues to struggle to understand why this is so.

The effort to understand democratic victory naturally began at the state level, where democratic attributes reside. For example, democratically elected politicians might be more resolute because they pay a higher price for the failure of their foreign adventures (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Morrow, Siverson and Smith1999; Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2003). Democracies may possess better motivated and more skillful soldiers (Reiter and Stam Reference Reiter and Stam1998), or they may be more adept at marshaling the resources necessary to prevail (Lake Reference Lake1992; Valentino, Huth and Croco Reference Valentino, Huth and Croco2010). Alternately, democracies may be more astute in their selection of contests, choosing only those they are likely to win (Reiter and Stam Reference Reiter and Stam1998; Reiter and Stam 2002). Another set of explanations derives from the social/international setting within which democracies operate. Choi (Reference Choi2003; Reference Choi2004; Reference Choi2012) argues that democracies tend to co-ally and are more effective alliance partners than non-democracies.

While plausible, all these theories ignore a simple possibility, one that should be considered even in the presence of other causal mechanisms. Democracies may or may not win wars because of their own qualities—because of what they are or what they do—or because of the qualities of their allies. It is also possible, however, that democracies prevail due to quantity (not quality), by fighting alongside a larger number of countries in most of their contests. Having more comrades in a fight must often prove to be an advantage, one that is likely to be valuable regardless of regime type. The biggest martial asset of democracies may well be that they are better at making friends, not that they are better at vanquishing their enemies.Footnote 1

We begin our “quantity” theory of democratic victory with the insight that the domestic incentives confronting political leaders differentially affect the costs and benefits of forming international coalitions to prosecute a war.Footnote 2 While both democracies and non-democracies have an obvious interest in victory, democracies are better able to make war collectively. Autocracies, with the small winning coalitions highlighted by the literature, tend to seek private benefits from fighting. A thirst for private goods means that autocracies optimize at a smaller coalition size to avoid diluting the spoils of war. Democracies, in contrast, already supply public goods to large domestic winning coalitions. They therefore gravitate toward war aims that are less adversely affected by the number of allies or participants. Objectives such as enforcing norms or advancing ideologies allow coalition members to share in the fruits of victory without diluting the payoffs available to other participants.

This contrast may help to explain, for example, the huge disparity between the number of Allied and Axis powers during World War II. For example, within this conflict, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, all democratic states in 1939, chose to join Britain in September 1939 to fight Germany. Each of these countries made many important contributions to the eventual allied victory, especially in the North African campaign and the D-Day landing. Importantly for our argument, these countries, along with the other allied powers, shared in the public benefits of the eventual allied victory.Footnote 3 Similarly, while Saddam Hussein chose to “go it alone” in invading Kuwait in 1990, the US-led coalition opposing him included no less than 32 countries. Saddam could have improved his chances of deterring the US-led coalition by creating his own alliance. However, this would presumably require sharing the spoils of war with others, diluting the very payoff that motivated Saddam to conquer Kuwait. The United States, in contrast, could share the public benefits of victory—including re-asserting territorial integrity, re-imposing the status quo and realizing various forms of solidarity—without these benefits becoming watered down.Footnote 4 It could even allow participants in the coalition to have different objectives, as long as these did not involve territory or plunder. No doubt, the United States would have defeated Iraq even without the assistance of other nations. Still, the ability to increase the size of a coalition should be an important military advantage.

As we show, democracies tend to go to war as members of more numerous and cumulatively more capable coalitions than do non-democracies. As we also demonstrate, states fighting alongside larger and cumulatively more powerful sets of partners tend to win the wars or disputes in which they are engaged. Finally, the penchant for democracies to fight in larger and more powerful coalitions actually accounts for much of the empirical relationship between regime type and victory and, in many specifications, subsumes any direct effect of regime type on victory. We run two separate analyses, one which operationalizes coalition size as the number of coalition partners fighting on the side of the state in question, and the other that assesses the total military capabilities of those partners. Results are consistent across both analyses. Similarly, our findings are robust to a variety of confounding effects and alternative explanations. After a brief review of relevant literature, we expand on each of these items, concluding with a discussion of key implications.

Democracy and Victory

The existing literature proposes a range of mechanisms linking regime type to military victory, with the bulk of contemporary scholarship arguing that democracies are more cautious in their selection of contests, more committed or adept on the battlefield, or both. We seek to augment the explanations provided in the literature with a simple and intuitive alternative causal account. In this section, we briefly review the claims made in other theories before moving on to present our own.

Existing electoral accountability explanations suggest that leaders in democracies are more likely to be removed from office after poor performance in a contest than are counterparts who avoid such conflicts (Bueno De Mesquita and Siverson Reference Bueno De Mesquita and Siverson1995; Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2003; Croco Reference Croco2011).Footnote 5 Democratic leaders thus have an incentive to work harder to avoid entering into conflicts they are unlikely to win.

In addition to electoral accountability, other explanations suggest ways in which democratic norms or institutions might constrain the behavior of liberal leaders (Russett Reference Russett1993; Doyle Reference Doyle1997). Officials in democracies are said to exhibit greater respect for the rights and freedoms of their citizens as they participate in war, thereby limiting unnecessary loss of life or destruction of resources (Reiter and stam Reference Reiter and Stam2008).Footnote 6 A reluctance to incur casualties could force democratic leaders to make more concessions to avoid fighting, so that the contests that actually occur are those where democracies are resolved. Democratic leaders may thus be forced to choose their conflicts more carefully, emphasizing disputes where victory appears assured. Finally, selection into contests could also lead to frequent victories if democracies have access to better strategic information than autocracies (Reiter and Stam Reference Reiter and Stam1998).

While arguments that democracies do a better job of “picking winners” are engaging and plausible, they are limited in the range of cases they can explain.Footnote 7 Democracies are not just more likely to win the wars they select and start, but are also more likely to win the wars in which they are targeted (Reiter and Stam 2002). This suggests that selection is at most, only part of the explanation. To account for democratic victory in even the contests democracies do not initiate, Reiter and Stam (Reference Reiter and Stam1998) claim that democracies exhibit a superior capacity to fight because their political culture produces more skilled and dedicated soldiers who exhibit greater leadership and take more initiative. Alternatively, democracies may have a greater ability to marshal resources for the war effort and demonstrate greater resolve given citizens with more at stake (e.g., Lake Reference Lake1992; Valentino, Huth and Croco Reference Valentino, Huth and Croco2010).Footnote 8 It is also possible that the same logic of electoral accountability that drives selection into conflicts may also influence democratic leaders’ choices once a conflict begins.

However, controversy persists about the source(s) of democratic acumen in combat, with researchers looking to refine existing theories or to identify additional implications of arguments to facilitate critical tests. Theories of accountability, risk aversion, and the putative abilities of democratic soldiers are all motivated by the desire to account for the puzzle of democratic victory. While democracies may, at the margin, demonstrate these advantages, there is much less of a mystery to explain if democracies simply show up to the battlefield as members of coalitions with superior aggregate capabilities. At the very least, it is necessary to determine whether democracies win wars and militarized disputes because they are better, individually, at fighting than non-democracies, or because they happen to benefit in conflict from the collective contributions of more (or more powerful) partners.

In contrast to purely state-level explanations for democratic victory, Choi (Choi Reference Choi2003; Choi Reference Choi2004; Choi Reference Choi2012) outlines a possible contribution from social aspects of war fighting. Democracies are said to be victorious because they tend to band together, allying with other democracies, and because democracies are more effective allies within these coalitions. Choi’s emphasis on the characteristics of alliance partners—namely that democracies co-ally and that democracies make better allies—is an important step in the direction that we ourselves advocate. However, her argument is not immune to criticism, even as we provide an alternative theoretical conception.

There are two critical elements of Choi’s coalition “quality” argument. Both must be present for the theory to correctly predict democratic victory: democracies must be better allies and they must be more likely to ally with other democracies. If democracies make better allies, but they are no more likely to ally with other democracies than with non-democracies, then the increased wartime effectiveness of democracies will not be disproportionately associated with democracies, but would instead diffuse through all coalitions involving at least some democratic members. This would not then account for the observed tendency toward democratic victory. Similarly, if democracies are not more effective allies, then a tendency for democracies to co-ally would not produce more successful military coalitions.

Research on democratic alliance preferences initially indicated that democracies were more likely to co-ally (Siverson and Emmons Reference Siverson and Emmons1991). However, this relationship is not robust to refinements in analysis or sample (Simon and Gartzke Reference Simon and Gartzke1996; Lai and Reiter Reference Lai and Reiter2000; Gartzke and Weisiger Reference Gartzke and Weisiger2014). Current thinking is that democracies co-ally, but that autocracies show a similar preference. As Lai and Reiter note, there are “sharp limits to the connection between democracy and international cooperation” (Reference Lai and Reiter2000, 203), suggesting as well sharp limits to the claim that democracies make better allies. See also section 10.3 of the appendix to this study, where we test, and reject, the proposition that countries prefer democratic allies.

Empirical evidence connecting regime type with alliance reliability is also mixed: Leeds (Reference Leeds2003) finds evidence that democracies are less likely than non-democracies to violate their alliance commitments, while Gartzke and Gleditsch (Reference Gartzke and Weisiger2004) find that democracies are less reliable allies when alliance commitments require actual intervention. We further explore and contrast the evidence for the democratic coalition quality argument and our own coalition quantity perspective in a portion of the Empirical Analysis section that follows evaluation of our hypotheses (details of this analysis appear in section 10.4 of the appendix). Re-confirming evidence in the literature, we find that democracies are not more likely to form exclusive coalitions with one another and that the quality of democratic coalitions, where present, is not sufficient to account for the apparent success of coalitions that include democratic participants.

Democratic political systems have more veto players, which is said to lead to more stable policy preferences, causing democratic alliance commitments to become more reliable. Although Choi is certainly not unique in asserting that democratic preferences are more stable, this is a claim that conflicts with democratic theory. Representation does not work without re-selection and re-selection invites volatility in social preference aggregation (Arrow Reference Arrow1951; Downs Reference Downs1957).Footnote 9 Madison (Reference Madison1961) rested his appeal to federalism on the assertion that democracy was ever-changing and therefore immune to the tyranny that attaches to a stable majority. According to other theories of democratic victory, it is instability, in the form of leverage by citizens over their leaders, that makes democracies so successful on the battlefield. It is therefore unlikely that democracies are both more stable as allies and less stable as regimes.

Existing findings in the literature, and further evidence provided here, call into question the core assumptions of the coalition quality explanation. At the same time, one can make the social/alliance argument without reference to the quality of partners, provided that the quantity of partners can adequately compensate. In the next section, we lay out our quantity perspective: a set of explanations consistent with our expectation that democracies tend to have more coalition partners of all regime types and that it is coalition size or aggregate capabilities—rather than the quality of alliance partners or intrinsic regime attributes—that best accounts for the observed tendency for democratic regimes to more often win at war.

Victory by Coalition: More is Better

Fighting alongside a large and powerful set of coalition partners increases a state’s probability of victory (Gartner and Siverson Reference Gartner and Siverson1996). Having more partners increases the material capabilities available to a given side, reducing the costs of fighting for each state and raising the likelihood of military success. In other contexts, scholars focus on “allies,” defined as states that are bound together by formal treaty obligations.Footnote 10 Because we are largely interested in only the effect that the number or capabilities of states fighting together have on military success, we focus on wartime “coalitions,” defined as states that fight on the same side of a military contest, whether or not they are party to formal treaties. It may be useful to distinguish this view of wartime coalitions as strictly de facto, in contrast to de jure alliances.

Our theory linking regime type to coalition size begins with the type of war aims that different regimes are likely to pursue. Almost by definition, democratic leaders are accountable to larger domestic constituencies than are autocracies, and so must provide benefits to a much larger number of people or groups in order to remain in power. For the same reasons that democratic leaders should logically focus on public goods spending internally in attempting to stay in office, and that autocrats should rely disproportionately on private goods spending (Lake Reference Lake1992; Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Morrow, Siverson and Smith1999; Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2003), non-democracies should seek out private benefits through their foreign policies, including the use of force, while democracies must generally prefer public foreign policy objectives. The basic “selectorate” logic developed to explain differences between the domestic policy preferences of leaders in democracies and autocracies applies equally to foreign policy decision making. Democratic leaders still value the acquisition of private goods through conquest, but large selectorates are less easily appeased through the distribution of private plunder. Democracies must be more easily led to war in pursuit of public goods, such as security or stable access to important economic resources or markets. Autocratic states in contrast should be more disposed to initiate or join contests with a focus on private goods.

At its core, our expectation that democracies tend to fight alongside larger sets of coalition partners rests on the expectation that democracies have a tendency to pursue war aims for which the incentive is to maximize coalition size, whereas non-democracies are more likely to seek war aims that produce incentives to fight alongside the minimum number of partners necessary to ensure victory. This expectation is, in turn, derived from expectations about the type of goods over which democracies and autocracies are most disposed to fight.

A state fighting for a private good—for example, control of territory or resources—receives the same probability-of-victory benefit from additional allies obtained by states fighting for social goods. However, states considering the option of merging military enterprises must also consider how to allocate the fruits of victory. The larger the number of partners involved in achieving victory, the smaller the portions of territory or plunder available for each participant. States may rationally be willing to accept a marginally higher risk of failure in exchange for a larger share of the spoils. Conversely, when a state is fighting with a goal that is non-rival, such as enforcing the territorial integrity norm (Zacher Reference Zacher2001; Fazal Reference Fazal2007), then there are few disincentives to recruiting many partners (Conybeare Reference Conybeare1992; Conybeare Reference Conybeare1994). States fighting for non-rival objectives should seek, and more often obtain, a larger number of partners than states that are fighting primarily to obtain private benefits. While combatants pursuing non-rival objectives can face free-rider problems in building coalitions (perhaps requiring the leadership of a major power), a country fighting for private goods is confronted by major positive costs for forming a coalition.

Conveniently, this logic applies both to targets and joiners as well as to war initiators. For example, the norm that state borders should not be changed by military force serves to enhance the security of all states in the system; therefore, the enforcement of this norm can usefully be viewed as a non-rival good. Defending states that limit their war aims to fending off the attacker and restoring the status quo have incentives to maximize coalition size (and democratic states have incentives to come to their aid to preserve a norm they value). Conversely, a state that is attacked may aim, in addition to defending the territory it currently holds, to turn the tables and seize territory from its attacker. Such a defender would face incentives to limit coalition size to avoid diluting the spoils of victory. These more expansive aims focused on securing rival goods are more likely among autocratic targets.

Our logic also holds for joiners. If a state is considering joining a coalition that is pursuing a rival good, a larger existing coalition means a smaller share of the spoils to any additional joiners. Thus, a state that is considering joining a coalition to seek rival goods has an incentive to avoid joining oversize coalitions—it is often better to join a small coalition with some probability of losing, but a large potential payoffs rather than joining a much larger coalition with a high probability of winning but diluted payoffs. When considering joining a coalition in pursuit of a non-rival good, however, such incentives to not exist, leading democracies, on average, to join larger coalitions.

Democratic states, as they have less interest in the conquest of private (rival) goods, should do more of their fighting to defend norms and secure other global public goods. Consistent with this expectation, Sullivan and Gartner (Reference Sullivan and Gartner2006) demonstrate empirically that democratic states are less likely to grant concessions when the belligerent state’s war objectives include a change in the status quo, especially a demand for a revision of the territorial status quo or a change in regime. Similarly, democracies tend to unite against demands by revisionist states (Lake Reference Lake1992).Footnote 11

In addition to the main rationale detailed above, we can provide at least two other arguments linking democracy and coalition size. First, democracies may have stronger incentives than non-democracies to diffuse the costs of costly contests. Coalitions diversify risk, lowering war costs and reducing the variance in those costs. This is important because democratic states may face incentives to adopt minimax strategies when it comes to war costs. For example, Russett, argues that “governments lose popularity in proportion to the war’s cost in blood and money” (Reference Russett1990, 46) and Gartzke notes that “war contrasts with citizens’ interests in survival so that citizens have incentives to use their political influence to attempt to avert casualty-causing contests” (Reference Gartzke2001, 481).Footnote 12 Filson and Werner (Reference Filson and Werner2004) demonstrate formally that democracies should be more likely than non-democracies to make concessions in order to avoid incurring war costs. By recruiting coalition partners, democratic states spread war costs across coalition members and placate domestic populations sensitive to the costs of war (Gartzke Reference Gartzke2001; Koch and Gartner Reference Koch and Gartner2005).

Second, the participation of coalition partners may increase the legitimacy of a side or faction in a war. Heightened legitimacy may lower the costs of fighting by lowering the resistance to fighting by both domestic and international audiences (Weitsman Reference Weitsman2004; Tago Reference Tago2005; Ikeda and Tago Reference Ikeda and Tago2014; Tago and Ikeda Reference Tago and Ikeda2015), and it may also increase the probability of participation by additional democratic partners. Research on international institutions finds tangible evidence that support for the use of force from the international community makes it easier for a democratic leader to obtain domestic approval (Martin and Simmons Reference Martin and Simmons1998; Hurd Reference Hurd1999; Voeten Reference Voeten2005; Chapman Reference Chapman2007). Fighting alongside coalition partners may have a similar effect to receiving support from the international community. Constituents who see the conflict as legitimate are more likely to assist in the war effort. Opponents may also find it harder to resist the moral suasion of a coalition.

Each of the explanations above provides a plausible account of why the relative success of democracies in war may be tied to external relationships, rather than, or in addition to, innate war fighting advantages localized within liberal regimes. While we find our main argument logically more compelling, empirical adjudication among alternative accounts falls outside the scope of this paper. The arguments above all anticipate an indirect causal relationship between democracy and military victory, one in which coalition size or capability plays a critical intervening role. The remaining focus of this paper involves testing the general relationship between regime type, coalition size, or capability, and victory.

Testable Implications

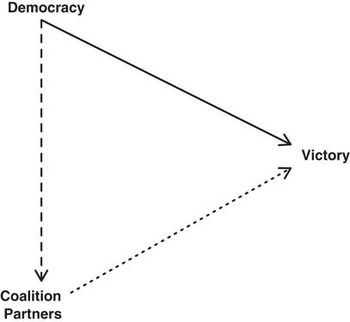

If the conventional wisdom in international relations is that democracy leads to an increased likelihood of victory (solid line in Figure 1), our perspective suggests that democracy more vigorously influences coalition size (dashed line), and that coalition size then affects whether states win wars or disputes (dotted line).

Fig. 1 Direct and indirect relationships between democracy and military victory

The relative impact of these direct and indirect effects of regime type and coalition size cannot be derived through logic, but must be estimated empirically. We can use the intervening variable argument made above to offer predictions. First, democracies should have more coalition partners when they experience militarized conflict and, given their higher numbers, these sets of coalition partners are likely to be cumulatively more powerful than those fighting alongside non-democracies.

Hypothesis 1: Democracies experiencing disputes/wars tend to fight alongside more coalition partners than non-democracies experiencing disputes/wars.

Hypothesis 1a: Democracies experiencing disputes/wars tend to fight alongside sets of coalition partners that are cumulatively more powerful than sets of coalition partners fighting alongside non-democracies experiencing disputes/wars.

Second, our claim of an indirect link between democracy and victory suggests that democracies tend to win their disputes and wars because they have more coalition partners. A test of the motivating puzzle of democratic victory requires that we establish not only that democracies in wars and disputes have more coalition partners, but also that states fighting with more partners tend to be victorious.

Hypothesis 2: States that fight alongside a greater number of coalition partners tend to win the disputes/wars in which they are engaged.

Hypothesis 2a: States that fight alongside more powerful sets of coalition partners tend to win the disputes/wars in which they are engaged.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 delineate the broad outlines of our argument. However, while necessary, each component is not sufficient separately to establish our claim that coalition size accounts for democratic victory. To do this, we need to assess a third set of hypotheses combining attributes of both of the other two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3: Democracies tend to win disputes/wars if and when they fight alongside a larger number of coalition partners.

Hypothesis 3a: Democracies tend to win disputes/wars if and when they fight alongside more powerful sets of coalition partners.

Empirical Analysis

Dependent Variables and Sample

For data on interstate conflict, we examine militarized interstate disputes (MIDs) involving displays or uses of force (levels 3–5) from 1816–2000, drawn from the dyadic MID (DYMID) data set (Maoz Reference Maoz2005). We include high-intensity, non-fatal MIDs as well as disputes with actual fighting because if large coalitions are effective in producing victory in fighting, they should also be effective in inducing opponents to back down before fighting. We omit the lowest intensity MIDs because these often result from accidents and other processes that do not directly reflect leader decision making (and thus are unrelated to the arguments posed above). The coding of minor fishing disputes, for example, might overrepresent democratic disputes (Weeks and Cohen Reference Weeks and Cohen2007). To parallel existing studies, in some of the regressions below we limit the sample to wars only (i.e., disputes in which there are at least 1000 fatalities).

The dispute-participant is used as the unit of analysis, which means that one observation per participant in each dispute enters each statistical regression model. Errors are clustered on the dispute-side, a unique identifier that captures both the dispute number and whether the state in question is on side 1 or side 2 in the data.

The first dependent variable is number of partners, or the number of coalition partners on a given state’s side. In some models, we also use an alternative binary version of this variable that is measured as 1 if the state side has more than two partners and 0 otherwise. We label this dichotomous variable as simply coalition. In hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3a, we operationalize coalition size differently, using the summed military capabilities of a state’s partners as a measure of coalition size (partners’ Composite Indicators of National Capabilities (CINC) score). Lastly, in the section 10.5 of the online appendix, we show that our results are also robust to measuring coalition size as the logged number of states on side 1.Footnote 13 As noted above, we take an inclusive view of what it means to be a partner—we consider any two states fighting on the same side of a conflict to be partners.

The second dependent variable, victory, is an ordinal variable that measures dispute outcome. The victory variable takes a value of 2 if side 1 achieves military victory or if side 2 concedes; it takes a value of 0 if side 2 achieves a military victory or side 1 concedes. Stalemates and compromises are assigned a value of 1.Footnote 14 There is one observation per dispute-side, and side 1 always refers to the side in question—side 1 and side 2 are thus different than the originally defined sideA and sideB in the Maoz MID data set. We also use an alternative binary version of this variable (win) in which stalemates and compromises are coded as 0 (i.e., not victory).

Other Data

We use the Polity IV democracy score to measure regime type, which captures rich variation in the level of democracy (see Marshall, Jaggers and Gurr Reference Marshall, Jaggers and Gurr2003; Marshall and Jaggers Reference Marshall and Jaggers2007). More variation should translate into a strong estimated effect for regime type on victory if such an independent effect indeed exists. However, because our theory focuses on the distinction between democracies and autocracies, we also use the Boix, Miller and Rosato (Reference Boix, Miller and Rosato2013) binary measure of democracy.

The material capabilities of a given country, CINC score, and the summed capabilities of all of the states on side 2 of the conflict, opponent(s)’ CINC score, are measured using the CINC data from the Correlates of War data set. CINC scores are composed of a state’s share of the total population, urban population, consumption of energy, iron and steel production, number of military personnel, and military expenditures in the system. Following Reiter and Stam (2002), we include a measure of troop quality in some regressions.Footnote 15

Finally, states may vary in their dispute propensity in ways that impact their interest in forming coalitions. States that are, ex ante very likely or very unlikely to go to war may tend to fight in different size coalitions when they do fight, and may face different probabilities of winning.Footnote 16 Therefore, we control for the propensity of a given dyad to engage in a MID (levels 3–5).Footnote 17 This dispute propensity control variable is then included in our directed-dyad and dyad-level analyses discussed in the next section.Footnote 18

In the following sections, we present results for Hypotheses 1–3, which make predictions regarding the number of coalition partners and Hypotheses 1a–3a, which make about the aggregate capabilities of coalition partners. In the online appendix, we demonstrate the robustness of these results to a variety of alternative specifications. The appendix includes analysis using a third measure of coalition size (the logged number of coalition partners in section 10.1 of the online appendix), and well as bivariate ordered probit results (an alternative to the bivariate probit models presented in the body of the paper in section 10.2 of the online appendix). We also conduct as extended comparison of our results with predictions from the literature on democratic alliance quality (e.g., Choi Reference Choi2004), which is supplemented with additional empirical analyses (see sections 10.3 and 10.4 of the online appendix). In section 10.6, we conduct a temporal sensitivity analysis and a consider the system wide level of democracy. In section 10.7, we consider initiation and its interaction with regime type. In section 10.8, we demonstrate that our results are robust to a brand new data set for wars from 1816 to 2007 developed by Reiter, Stam and Horowitz (Reference Reiter, Stam and Horowitz2014). Finally, we use permutation tests to show that our primary results are not artifacts of chance in section 10.9 (e.g., Gordon Reference Gordon2005). And in section 10.10, we evaluate the out of sample performance of the models using cross validation tests (e.g., Efron Reference Efron1983; Ward, Greenhill and Bakke Reference Ward, Greenhill and Bakke2010; Hill and Jones Reference Hill and Jones2014; Crabtree and Fariss Reference Crabtree and Fariss2015). We also estimate several of our models with different samples and reduced specifications (sections 10.12–10.13).

More Democratic States Fight in Larger Coalitions

Our first hypothesis is simply that democratic states fight alongside more partners. In tests of this hypothesis, the unit of analysis is the dispute-participant. Therefore, there can be multiple observations for each dispute in the MIDs data set.

We use a negative binomial regression to evaluate the relationship between regime type and the number of partners. Many states fight without partners, leading to a high proportion of 0s in the dependent variable. We follow King (Reference King1989) in choosing the negative binomial model over Poisson regression, which assumes that the mean number of partners equals the variance in the number of partners.

Figure 2 reports the distribution of the number of coalition partners for war participants and participants in major MIDs, 1816–2000. The mean number of partners for autocracies and for democracies appear as dashed vertical lines in each plot.Footnote 19

Fig. 2 Distribution of the number of partners in the sample of all war participants (left panel) and all militarized interstate dispute (MID) participants (right panel), 1816–2000 Note: the dashed line represent the median number of coalition partners in each panel.

Table 1 presents the results of this estimation in both the sample of all wars 1816–2000 and in the sample of MIDs (levels 3–5) during the same time period. Errors are clustered on dispute-side, which, as mentioned, captures both the dispute number and whether the state in question is on side 1 or side 2. It is necessary to control for the material capabilities of the state in question (CINC score) because democracies are often stronger than their non-democratic counterparts (see Przeworski and Limongi Reference Przeworski and Limongi1997; Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Bates, Goldstone, Kristensen and O’Halloran2006), and because more capable states may prove more attractive as potential security partners. We also control for the capabilities of the opposing state(s) (Opponent(s)’ CINC score). For both measures of democracy in both samples, the level of democracy strongly predicts the number of coalition partners for states involved in disputes or wars.Footnote 20

Table 1 Number of Coalition Partners

Note: standard errors in parentheses. Specification: negative binomial regression with errors clustered on dispute-side.

MIDs=militarized interstate disputes; CINC=Composite Indicators of National Capabilities.

*p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

Figure 3 depicts the substantive effect of an increase in democracy on a state’s expected number of partners in a dispute. This evidence supports the first link outlined by our argument: democratic states contest disputes in larger coalitions.

Fig. 3 Predicted number of partners as a function of two different measures of democracy for militarized interstate disputes (MIDs) (3–5) and wars only Note: all other variables from the models are held at their mean values.

More Partners, More Victory

The second link of our argument (Hypothesis 2) posits that states that are accompanied by more partners are more likely to prevail in contests. To test this hypothesis, we estimate the probability of victory using ordered probit regression, where the dependent variable, victory, is equal to: loss (0), draw/stalemate (1), or win (2).

We control for regime type as well as the capabilities of the state in question (CINC score) and the enemy’s summed material capabilities (Opponent(s)’ CINC score). Including the state’s own material capabilities as a regressor controls for the possibility that more powerful states may have an easier time recruiting partners. Including the material capabilities of a state’s opponent(s) addresses any impact on the likelihood of victory attributable to the correlation between the number of partners on side 1 and the strength of side 2. Democracy controls for the direct effects of regime type on the probability of victory (i.e., effects not involving coalition size).

The results presented in Table 2 are consistent with Hypothesis 2. The number of coalition partners correlates positively and significantly with the likelihood of victory. Though not large, the effect is far from trivial. In wars, increasing the number of partners by 0.5 SD (a 3 partner increase) is associated with an 11 percent increase in the probability of outright victory and an 10 percent decrease in the probability of outright defeat (both relative to draw/stalemate).Footnote 21 For high-intensity MIDs, a 0.5 SD increase in the number of partners (a 2.6 partner increase) is associated with a 7 percent increase in the probability of outright victory and a 6 percent decrease in the probability of outright defeat.Footnote 22

Table 2 Probability of Victory

Note: standard errors in parentheses. Specification: ordered probit with errors clustered on dispute-side.

MIDs=militarized interstate disputes; CINC=Composite Indicators of National Capabilities.

*p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

Table 2 also reveals the expected results for the independent variables. More capable states tend to win, while states facing capable opponents tend to lose.

Figure 4 details the substantive effect of possessing partners on the predicted probability of winning a dispute. The evidence supports the second link of our causal argument; states with more partners are more likely to win disputes or wars.

Fig. 4 Predicted probability of ordered outcomes during militarized interstate dispute (MIDs) (3–5) and wars only as a function of the number of coalition partners using two different measures of democracy (Polity IV in the two left panels and Boix, Miller and Rosato (Reference Boix, Miller and Rosato2013) in the two right panels) Note: all other variables from the models are held at their mean or median values.

Aggregate Partner Capabilities

In the preceding section, we measured the size of a state’s coalition as the number of co-participants a state has in a conflict. A second way to measure coalition size is as the total power of a state’s co-participants, which we measure as the summed CINC scores of all of the state’s partners, partners’ CINC score. Tables 3 and 4 recreate the results from Tables 1 and 2 with the use of this alternative measure. The results are consistent. More democratic states tend to fight with more powerful coalitions (Table 3; Figure 5), and states with more powerful sets of coalition partners are more likely to prevail (Table 4; Figure 6).

Fig. 5 Predicted Composite Indicators of National Capabilities (CINC) score for all coalitions partners as a function of two different measures of democracy for militarized interstate disputes (MIDs) (3–5) and wars only Note: all other variables from the models are held at their mean values.

Fig. 6 Predicted probability of ordered outcomes during militarized interstate disputes (MIDs) (3–5) and wars only as a function of partners’ summed Composite Indicators of National Capabilities (CINC) scores using two different measures of democracy (Polity IV in the two left panels and Boix, Miller and Rosato (Reference Boix, Miller and Rosato2013) in the two right panels) Note: all other variables from the models are held at their mean or median values.

Table 3 Partners’ Summed CINC Scores

Note: standard errors in parentheses. Specification: ordinary least squares with errors clustered on dispute-side.

MIDs=militarized interstate disputes; CINC=Composite Indicators of National Capabilities.

*p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

Table 4 Probability of Victory

Note: standard errors in parentheses. Specification: ordered probit with errors clustered on dispute-side.

MIDs=militarized interstate disputes; CINC=Composite Indicators of National Capabilities.

*p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

As with number of partners, more democratic states are more likely to fight in more capable coalitions. This result is robust to controlling for the power (CINC score) of the state in question, which is also positively correlated with the aggregate power of their coalition partners. More democratic states contest disputes alongside partners that are not only more numerous, but also cumulatively more powerful.

More powerful coalitions are also associated with a higher probability of victory. Consistent with Table 2, we also find that powerful states are more likely to prevail, while states facing more powerful opponents or coalitions are less likely to do so.

Jointly Modeling Coalition Size and Victory

While democracies fight alongside larger coalitions and states that fight alongside larger coalitions tend to win disputes and wars, we have not yet shown directly that democracies win wars because they fight alongside larger coalitions. Therefore, we next combine the two equations evaluated above into a bivariate probit regression.Footnote 23 This approach allows us to estimate the joint relationship depicted in Figure 1.

The two equations in the bivariate probit model are estimated simultaneously. The relatedness of the two jointly estimated models is captured by a parameter for the correlation between the two outcomes as they are explained by the variables in the two models. Using this method, we can account for the direct relationship between war outcomes and coalition size, as well as the indirect relationship between regime type and the choice to enter a coalition, as captured in the first equation.

For these models, we collapse the count of the number of partners into the binary variable coalition, and we collapse the continuous measure of partners’ strength into the binary variable powerful partners. The dependent variable for the second regression in each model is the binary variable win, in which stalemates and compromises are coded 0 (i.e., not winning). The same controls used above enter the two equations of this model and errors are clustered on dispute-side. The original number of partners and Partners’ CINC score variables enter the second equation.Footnote 24

Though we necessarily lose some information by creating binary variables out of the count and ordered dependent variables, we do gain computational tractability and numerical stability. As Cameron and Trivedi (Reference Cameron and Trivedi2005) discuss, “[g]eneralizations to multivariate probit are obvious though will experience numerical challenges because of higher order integrals” (523). However, Cameron and Trivedi (Reference Cameron and Trivedi2005) go on to state that when the outcome variables are “ordered then the model can be generalized to a bivariate ordered probit model” (523). We also estimate bivariate ordered probit models in the appendix and the results are generally consistent.

Tables 5 and 6 display results that corroborate the findings presented earlier and lend further support to both links in our argument. Democracies tend to win the wars that they fight, not because of a direct effect of regime type on victory, but because they fight as part of larger coalitions. Note that no statistically significant relationship exists between the probability of victory and level of democracy when the number of coalition partners or strength of coalition partners is accounted for. Meanwhile, the number/strength of coalition partners variable is significant in each of the models in both tables.Footnote 25

Table 5 Joint Probability of Partners and Victory: Bivariate Probit

Note: standard errors in parentheses.

MIDs=militarized interstate disputes; CINC=Composite Indicators of National Capabilities.

*p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

Table 6 Joint Probability of Allies and Victory

Note: standard errors in parentheses. Specification: bivariate probit with errors clustered on dispute-side.

MIDs=militarized interstate disputes; CINC=Composite Indicators of National Capabilities.

*p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

Disaggregating the Data

It is often helpful in analyzing regression results to disaggregate the data to show the strength of relationships across the full range of values. For example, it could be that democracies attract more coalition partners because they win. If democracies are more effective or charismatic coalition partners, then we again return to characteristics of regimes as an explanation for democratic victory. We want to confirm that the relationship between winning and coalition size is broadly consistent in all regions of the data. Figure 7 reports the probability of victory for democracies and autocracies for every possible number of coalition partners. The figure thus allows one to compare the probability of victory for democracies with two partners to the probability of victory for autocracies with two partners, and to compare democracies with autocracies again when they each have three partners, and so on.

Fig. 7 The probability of victory by regime type, varying number of coalition partners

Evaluating the effects of regime type and coalition size at different thresholds is somewhat complex. Figure 7 helps to make sense of different combinations of democracy and coalition size by displaying the distributions for the probability of victory estimated from 14 probit regression models. Each regression is estimated on observations that are all of the same regime type and have the same number of coalition partners. Some observations were consolidated in order to estimate each model on at least 100 observations. For example, observations were included in the same model if they had 4 or 5 coalition partners. These models also include the controls as outlined previously. The percentages displayed along the top horizontal axis of the figure represent the proportion of democracies for each “bin” of partner counts. The number of observations in each model is displayed above the democracy probability distributions and under the autocracy probability distributions.

Disaggregation of the relationship between regime type and victory by number of coalition partners confirms the basic picture provided by the previous analysis. Democracies are not generally more likely to win wars and disputes independent of the count of partners. Fighting with more partners increases the probability of victory for both democracies and autocracies. The results also show that, for most values of coalition size, democracies have a higher probability of victory than autocracies, which is consistent with the small positive, but statistically insignificant, effect of democracy on victory reported in the bottom half of Table 5. The effect of the number of coalition partners on victory is clearly much stronger than the effect of regime type. When fighting alone, a democracy is no more likely to win wars or disputes than an autocracy, while an autocracy fighting with more than six coalition partners is far more likely to achieve victory than an unassisted democracy.

Not only is a larger number of coalition partners associated with a higher probability of victory, but consistent with Hypothesis 1, more democratic participants fight with more partners. This is apparent in the proportion of democracies figures reported above each “bin” which generally increase with the size of the coalition. The ratio of democracies to non-democracies increases as we move from left to right on the chart, reflecting the fact that democracies tend to have more partners.Footnote 26

Finally, Figure 7 also casts considerable doubt on the assertion that better democratic war fighting leads more states to partner with democracies. While democracies have more partners on average, many democracies possess no partners or few partners. A theory in which superior democratic war fighting leads democracies to attract more partners must, thus grapple with the fact that democracies vary to a considerable degree in their apparent attractiveness and therefore must vary in (perceived) battlefield effectiveness. One must either conclude that at least some democracies are less effective than some autocracies at war fighting, or that variation in coalition size is associated with other factors besides wartime effectiveness. We prefer to attribute the success of democracies to the fact that democracies have more coalition partners, as the evidence from Figure 7 is that fighting alongside more numerous partners unambiguously increases the probability of victory.

A Comparison with Previous Findings

It is useful to contrast our empirical approach with that taken by Reiter and Stam (Reiter and Stam Reference Reiter and Stam1998; Reiter and Stam 2002), who conducted the seminal work on democratic victory. Unlike Downes (2009), our intent is not to challenge their core findings: we agree that democracies tend to win the wars they fight. Thus, we structure our analysis to test our hypotheses, rather than to replicate their findings exactly. Most notably, because we wish to model both the direct effect of regime type on victory and its indirect effect (via coalition size), we adopt a bivariate modeling approach in our test of Hypotheses 3 and 3a.

Reiter and Stam (2002, 45) treat democracy as a continuous variable and predict a linear relationship between democracy and victory among target states and a non-linear relationship among war initiators.Footnote 27 Our theory applies to initiators, joiners, and targets alike and addresses the distinction between democracies and autocracies rather than the effect (curvilinear or otherwise) of a continuous measure of democracy. Therefore, we employ both the continuous Polity measure and a binary measure of regime type and we do not interact regime type with initiation.

While we conduct our analysis on a sample of wars, we also expand our sample to include all high-intensity MIDs (there is nothing in our theory specific to conflicts with over 1000 battle deaths, the threshold for the wars only sample).Footnote 28

Despite these differences in approach, Reiter and Stam’s original findings are actually not in conflict with our argument: they find a large and robust effect of coalition size on victory and this effect is statistically stronger in their models than the direct effects of regime type. However, their model is not designed to capture the possibility that coalition size is, as we show, determined by regime type.Footnote 29 Once we account for the indirect effect of democracy on victory via coalition size, we no longer observe the strong direct effect of democracy that Reiter and Stam identify.Footnote 30 Thus, while do not rule out the possibility that Reiter and Stam are correct and that, at the margins, democracies are superior war fighters, statistically these direct effects of regime type on victory pale in comparison with the indirect effect of regime type on victory through coalitions size.

Conclusion

The theory and results presented here provide a simple and intuitive link between regime type and war-fighting success: democracies win the wars they fight because they are joined in disputes and warfare by larger and more powerful coalitions. We show that democracies fight with more coalition partners than non-democracies, that states with more partners are more likely to prevail, and that the indirect effect of democracy on war-fighting success through coalition size subsumes the direct effect of regime type on victory. These results are robust to a wide range of alternative specifications, shown both here and in the online appendix, and the core relationships are consistent across the full range of the data. We also present theoretical and empirical reasons for favoring our “quantity” argument regarding democratic coalition over “quality” arguments made elsewhere.

Theoretically, we have linked the incentive to fight alongside additional partners with the differential domestic incentives faced by democratic and non-democratic political leaders. Specifically, each partner brings additional material capabilities to the war effort. Additional partners lower war costs, and also reduce the variance in war costs paid by each state. This reduction in war costs is a direct benefit to the citizens of each democracy paying for and participating in the conflict. Moreover, war over issues that democracies care about requires no significant division of the spoils, encouraging initial participants to maximize coalition size. In contrast, additional partners dilute the payoffs of conflicts over private goods, such as territory and tangible resources, which seem more often to motivate non-democracies to fight.

Definitive tests of the mechanism(s) linking regime type to coalition size require more precise data that are able to distinguish between war aims with primarily public goods components and war aims with primarily private goods components. Similarly, information about the costs born by publics in terms of both troop deployments and casualties in addition to the financial and material resources allocated by each state within a coalition would allow us to further test the causal mechanisms of our argument. Future research will attempt to provide more direct evidence regarding these mechanisms. However, the results presented here make a strong empirical case for our central assertion: democracies win the wars that they fight because they fight alongside more (and cumulatively more powerful) partners.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2015.52