Few could have appreciated how difficult economic conditions in Singapore would become after the Japanese Occupation began on 15 February 1942 or how much they would deteriorate as the Pacific War dragged on. This article focuses on Singapore's Second World War economy and has two main aims. One is to quantify as far as possible Japan's wartime economic exploitation of Singapore and neglect of its people. Since both were considerable, we also try, as our other aim, to account for the persistence of an outwardly socially calm Singapore through over three-and-a-half years between the onset of occupation and Japan's 15 August 1945 surrender.

In pursuit of these aims, we pose a series of questions which we attempt to answer. First, what were the main components of Japanese exploitation and why did Japan, despite the occupation's increasingly dire economic effects, allow Singapore's economy to be reduced to a state of chronic and acute shortage? We argue that Japan never supplied Singapore with any appreciable amount of consumer goods because it had never intended to and, before long, even if this policy might have been reversed, Japan's own economy gave no scope for reversal. Throughout the war, Singapore's population had almost entirely to make do with the stock of goods available at the start of occupation. For most of the war, Singaporeans lacked not just palatable food but also sufficient food. By 1945, most residents were malnourished, often seriously. Our argument in this regard is that, once again, the Japanese were indifferent to the hardships of Singaporeans so long as those working for them were physically able to do so and mass famine was avoided. A lack of appreciation of the geography of Malaya, an area unsuited to growing rice, and an unwillingness to offer economic incentives to farmers exacerbated food scarcity. Finance can be central to economic exploitation but often is not considered. We show that, Japan not only occupied Singapore but, through the hidden taxation of printing money, forced Singaporeans to finance the costs of being occupied.

A second set of questions is: What use did Japan try to make of Singapore, and why did the Japanese determine the course they followed? Our explanation is that originally the Japanese, planning for a short war, had fairly narrow, short-term objectives for the usefulness of Singapore, but these altered as the war went on. At first, Japan wanted Singapore above all for its strategic position and as a centre for the storage and shipment of oil, the latter fundamental to Japan's war effort. By mid-1943, Japan, badly pressed for military supplies, goods at home and shipping capacity as well, hoped against all odds to make Singapore an industrial centre.

The third question is how did Japan so effectively keep a lid on social unrest, even popular rebellion, in a society so exploited, so short of goods and food, and so beset by rampant inflation as wartime Singapore's? In a city with such a concentrated Chinese population, one might expect underground resistance. Part of the answer is, of course, apparent. Singapore's Chinese population was divided among dialect groups while guerrilla bands in the Peninsula offered an opportunity to oppose the Japanese. Moreover, in Singapore repression was savage and pervasive, as many recollections of the war graphically document. On a small island like Singapore with a population of about a million it was easy for Japanese security services to watch and track anyone appearing suspicious. Additionally, as Chin Kee Ong observes, many Singaporeans believed that the war would not go on that long.Footnote 1 If so, why risk running afoul of the Japanese. Just endure and stay alive for better days. However, we suggest that a further, and not unimportant, reason for placidity had its roots in Singapore's wartime economy of shortage. In an environment of serious calorie deficiency for nearly every Singaporean, Japan's control over food afforded a powerful social control tool. The supply of food, both as priority rations and in exchange for work, helped to tie a substantial section of the population into at least tacit acceptance of Japanese rule.

Consumer goods and food deprivation

Pre-war Japanese policy and goods shortage

Japanese policy for occupied Southeast Asia was clear by November 1941: ‘We will have,’ Finance Minister Kaya Okinori emphasised, ‘to pursue a so-called policy of exploitation’. Japan must

adopt a policy of self-sufficiency in the South, keep the shipment of materials from Japan to that area to the minimum amount necessary to maintain order and to utilize labour forces there, ignore for the time being the decline in the value of currency and the economic dislocations that will ensue from this, and in this way push forward.Footnote 2

Although sending almost nothing to Southeast Asia meant that its inhabitants would be thrown back entirely on the pre-war stocks of goods and their own ingenuity as well as having to support the occupying armed forces, Japanese officials considered this acceptable. Self-sufficiency, Kaya explained, could be easily maintained by Japan and would pose no problem for Southeast Asians ‘because the culture of the inhabitants is low, and because the area is rich in natural products’.Footnote 3

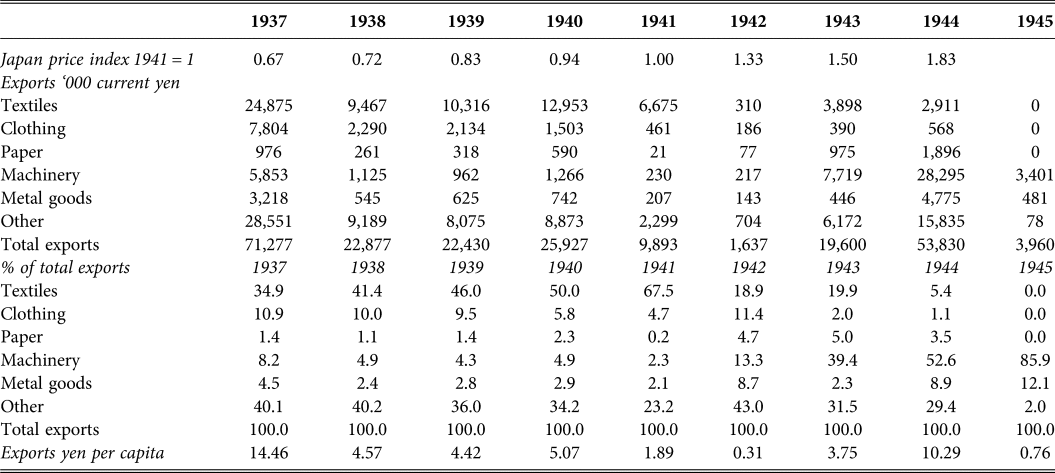

Throughout the war, Japan sent virtually no consumer goods to Southeast Asia. Japanese import and export data record the great bulk of wartime Southeast Asian commerce, since countries in the region had little opportunity to trade except with Japan. Insofar as Southeast Asia received any Japanese help this went overwhelmingly to Thailand and Indochina which were Japanese allies. Japanese exports to Singapore and the rest of Malaya abruptly ceased in 1942, amounting that year to a third of one yen (a sixth of a Straits dollar at pre-war exchange rates) per person. Throughout the war, Japan supplied to Singapore consumers almost no textiles, clothing or paper. These were goods for which Singapore and the rest of Malaya relied heavily on imports and for which, as for a host of other consumer items, local manufacturing capacity was lacking (table 1). The acute wartime shortages in Singapore of practically every basic good and nearly all medicines is well known. Rationing could not make up for shortfalls, since this had to draw on pre-war stocks and these were soon depleted. By the later stages of the war, cloth rations in Singapore were three yards of fabric and three ready-made pieces a year for a family of eight. That was also approximately equivalent to the early 1944 ration detailed in a contemporary Japanese research report of a yard per person per year.Footnote 4

Table 1: Composition of Japan's exports to Malaya 1937–45

Sources: Trade: Japan, Ministry of Finance, Nihon gaikoku bōeki nenpyō [Annual return of the foreign trade of Japan], annual series, 1937–1944–48 (Tokyo: variously published by Ministry of Finance, Cabinet Printing Office, Finance Association of the Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Printing, 1941–1951). Prices: J.B. Cohen, Japan's economy in war and reconstruction (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1949), p. 97.

Japan did not supply household goods to Malaya until July 1943, but this was not followed by many, if any, similar shipments.Footnote 5 The main exception to the lack of Japanese exports to Malaya was in 1944 and largely due to the arrival of machines and metal goods. These exports from Japan reflected a combination of the new, mid-1943 Japanese desire to make Singapore an industrial centre, analysed below, and Japanese defence needs against a likely Allied invasion.

Evidence is lacking to suggest that in 1943 or 1944 Japan wished to relent and begin to send goods to Singapore. But even if the Japanese, aware of the increasingly straitened circumstances of Singaporeans, had wanted to supply Singapore this would have been difficult for two reasons. One is that Japan was now desperately short of goods at home. A successful war economy must increase output while also switching production in favour of war goods. In Japan, however, from 1940 to 1944 GDP stagnated and home consumption dropped continuously and to far beyond any acceptable level: the Japanese economy could not spare goods to supply Southeast Asians even had that become a policy objective.

Japanese central government expenditure, largely a reflection of military spending, was still a fifth of GDP in 1940, but by 1944 stood at 45 per cent of national income. In 1944, war expenditure probably absorbed half of national income.Footnote 6 As Japan shifted towards a war economy consumer expenditure fell from two-thirds of GDP in 1940 to under two-fifths by 1944. Official Japanese statistics indicate falls in real per capita household consumption expenditure of over two-fifths between 1937 and 1944 and almost a third from 1940 to 1944.Footnote 7 Evidence of a sharp drop in civilian living standards by 1944 includes a reduction in average daily calorie intake from an estimated 2,250 in 1940 to 1,800 by 1944; a decrease in the net supply of cotton cloth from 2,184 million square yards in 1937 to 51 million square yards; and a similar decline in the availability of woollens. Few, if any, additional supplies of silk or synthetic fibre compensated for the lack of cottons and wool.Footnote 8

The second reason for not sending goods was that by 1943 Japan was already seriously pressed for merchant shipping.Footnote 9 In analysing Japanese wartime shipping capacity it is important to separate tanker and non-tanker ships. Although Japanese tanker capacity continuously increased until 1944, other merchant shipping tonnage fell almost continuously. By December 1942, it was already dropping and a year later was less than three-quarters of its pre-war level (table 2). As early as 1944, Japan could no longer meet even its paramount shipping needs: it could not transport much to its home economy even from the nearest Southeast Asian countries, and nothing from Burma. Merchant tonnage had to be prioritised for a few strategic exports from Southeast Asia such as bauxite, needed to make aluminium for airplanes.

Table 2: Japan: Merchant non-tanker and tanker shipping 1941–45 (‘000 tons)

Notes: Panel a: 1. Serviceable ships are Army ships, Navy ships and serviceable civilian ships. 2. Tonnage afloat does not correspond to ships built minus ships sunk because Japan added to total tonnage, mostly during 1942, through the addition of captured and salvaged ships. 3. Dec. and Aug. 1945 figures are for the shipping situation at the first of the month. 4. Some sources, e.g., Cohen, Japan’s economy, p. 267, and G. Ránki, The economics of the Second World War (Wein: Bohlau Verlag, 1993), p. 159, show Japanese operable merchant shipping on 15 Aug. 1945 as 557,000 tons. This figure is arrived at by excluding from operable tonnage ships cut off in the southern areas. That is not done in this table because cut-off shipping would still have been available for use in Southeast Asia.

Panel b: 1. In 1945 the collapse of tankers importing oil to Japan was mainly because Japan was cut off from supplies in Southeast Asia. The termination of Singapore convoys occurred in March 1945. Tanker tonnage importing oil to Japan fell from 700,000 tons in January 1945 to 100,000 tons in April 1945 and thereafter declined continuously until the end of the war.

Source: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The war against Japanese transportation 1941–1945 (Washington, DC: Transportation Division, USSBS, 1947). p.116.

Although Japan sent virtually no goods to Malaya, transfers from the latter back to the Japanese home islands were substantial. Table 3 quantifies as far as possible Malayan real resource transfer to Japan. Between 1942 and 1945, Malaya's trade surplus with Japan totalled 140 million yen and accounted for a fifth of the overall Japanese surplus with Southeast Asia. While the quantifiable trade transfer suggests the Japanese were not wrong in seeing the Malay Peninsula as an area to exploit for raw materials, the wartime usefulness of Malaya to Japan, and so resource transfer, was limited: Japan already had considerably more tin and rubber than it needed, even for a long war. Bauxite and some iron were the main Malayan raw materials that Japan could use. Table 3 omits, however, plunder and other resources taken from Malaya that cannot be reliably quantified and so is a lower bound of total transfers. The plunder of commodities, although including between 60,000 and 150,000 tons of rubber, was not especially great but it was considerable for all types of transport.Footnote 10

Table 3: Malaya: Trade balance with Japan, 1941–45 (‘000 current yen)

Source: Japan, Ministry of Finance, Nihon gaikoku bōeki nenpyō [Returns of foreign trade of Japan], 1937–1944–48.

Singaporeans and Japanese alike attempted to fashion substitutes for previously imported goods. Fibres of pineapple plants were used to make fishing nets, belt conveyor hoses and tyres and also to mend clothing. The fibres were extracted in a process remarkable for its high labour-intensity, by women scraping the pineapple leaves with small knives.Footnote 11 People in Singapore produced shark oil to provide, as a dietary supplement, a sort of medicine.Footnote 12 Rubber oil was made locally as a substitute for petrol and to take to Thailand where it could be exchanged for rice.Footnote 13 Rubber was, however, just one of many possible fuel substitutes. Taxis in Singapore ran on charcoal, as did some automobiles.Footnote 14

Food shortages

Japanese food policy in Singapore and the rest of Malaya mirrored the insistence on self-sufficiency in goods, but imposed even greater hardships. The strategy was that if Malaya tried hard enough it could become food self-sufficient and that, as for other parts of Southeast Asia, an autarkic Malaya was essential to avoid the domino effect of a military loss in one region causing the Japanese military to lose another due to food and materiel shortages. It is unclear how much of a role misperception and a lack of understanding of Malaya's economy played in the approach to Malayan food self-sufficiency, but even a cursory look at the facts should have made obvious the vulnerability of the Straits Settlements and the rest of Malaya to enforced autarky, and the near impossibility of self-sufficiency in the medium term of three to four years, if ever.

In 1940 in Malaya, imported food, including livestock, provided an average of 1,400 calories a day per person and local production a further 1,162 calories, a total of 2,562.Footnote 15 Rice was the staple food and accounted for the largest share of calorie consumption, livestock hardly any. By the 1930s, Malaya produced less than a quarter of the rice it consumed; the rest, about 610,000 metric tons, was imported, making apparent the supply problem of obtaining Malaya's customary quantities of rice. Once Japan's policy of autarky largely cut off Malaya from trade with the great Southeast Asian rice producers of Thailand, Burma and Indochina, food and calorie consumption in Singapore plummeted. It was impossible to make up for the loss of pre-war imports for three reasons. One was that much of Malaya was geographically ill-suited to growing rice or most other food crops. Second, in 1943 Japan ceded Malaya's main rice-producing states to Thailand. Third, high inflation but low, inflexible Japanese-administered prices for rice deliveries discouraged Malayan production.

Nevertheless, Singapore avoided famine, apart from Javanese labourers imported by the Japanese and possibly a few isolated cases. Five principal sources of food explain this, even with the swelling of the island's population by roughly 230,000 to around a million, due to a large inwards migration from 1942 of refugees flocking down the peninsula to avoid the invading Japanese. Three food sources are discussed now, namely urban cultivation and squatter settlements; smuggled and legal imports by Chinese traders; and black markets. The remaining two, rationing and working for the Japanese, are considered later because they are important in accounting for effective Japanese social control over Singapore. It should be noted here, however, that by the war's later stages Japanese-organised food supplies were markedly insufficient to maintain Singaporeans even at the level of the malnutrition from which most suffered by 1944.

Urban cultivation and squatter settlements

Singapore municipality, where in 1947 half the population lived on 11 per cent of the island, was exceptionally densely packed and offered limited scope for cultivation.Footnote 16 For peninsular Malaya, it has been shown that in comparison to a pre-war calorie intake of 2,500, in 1945 production of root crops, bananas, maize, ragi, groundnuts and sugar provided an average of 520 calories per person per day, which compares badly with minimum adult calorie requirements of some 2,000 to 2,250 calories. Almost certainly, cultivation on Singapore island resulted in fewer calories than 520 due to limited land availability.Footnote 17

The need for food and large inwards migration during the war led to the appearance for the first time of large squatter populations on the fringes of Singapore. The area under market gardens expanded from 1,500 acres to 7,000 acres, or 0.021 of an acre for each of an about 263,600 additions to Singapore's population between 1938 and 1944.Footnote 18 Squatters, as well as finding land to grow their own food, had easy access to central Singapore and so a ready market for surplus production. For one observer returning to Singapore just after the war, the spread of squatter settlements, along with a proliferation of hawkers, were among the city's most prominent features.Footnote 19

Given Singapore's restricted agricultural opportunities, calorie intake from resources available on the island itself could be maximised in two ways. One was that the cultivation of root crops like tapioca and sweet potatoes boosted the calorific, though typically not the nutritional, benefit per unit of land. Japanese administrators made great efforts to promote cultivation through numerous campaigns to grow-your-own food and a dissemination of information on the preparation and cooking of previously little known, and to Singaporeans notoriously unpalatable, crops.

Second, as well as gardening some Singapore residents kept chickens and ducks which they fed on the city's two-inch cockroaches trapped in the sewers at night.Footnote 20 Urban cats and dogs, although not always easily caught, afforded an obvious source of high protein. In Singapore, these animals disappeared in sufficiently great numbers to qualify as endangered species.Footnote 21 A 1946 Malayan Union Medical Department Report laconically observed: ‘food was very scarce and no dogs were to be seen’.Footnote 22

Food imports

Singapore's location in so great a rice-deficit country as Malaya might seem to have made wartime famine almost inevitable. But geography and a 1944 shift in Japanese policy helped Singapore to obtain sufficient food to keep famine at bay. The key geographical factor was Singapore's centrality in Southeast Asia, which allowed relatively cheap and simple transport by coastal shipping of smuggled rice and other foodstuffs from Thailand, Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula.

An April 1944 Japanese decision, discussed below, to permit the private import of rice from Songkhla in southern Thailand further enabled Singapore to utilise unknown, but almost certainly substantial, rice supplies from nearby Southeast Asia. These new ‘free market’ Singapore Chinese participants in Japanese-sponsored schemes to bring more rice to the city could sell some of their cargo on the open market. When private importers’ rice reached Singapore, it was immediately sold by the bag ex vessel to wholesalers who met returning ships, usually at Crawford Bridge. Sanctioned imports and, with them, added scope for unsanctioned ones, created trade opportunities to which Singaporeans responded with a flurry of boat building. Wartime possession of a junk, a Singapore trader recalled, was ‘like owning six ships during peace time’.Footnote 23

Black markets

In Singapore, a faltering Japanese rationing system and the restricted scope for urban cultivation point to the centrality of rice brought to Singapore (illegally and legally) by Chinese traders and the vital role of black markets in Singapore's food provision. In Singapore and elsewhere in Malaya, black market food was ‘crucial’ in maintaining the health and welfare of the population.Footnote 24 During the war, most Singapore Chinese firms continued to trade and many apparently prospered.Footnote 25 A Chinese commercial network and the port's central location in Southeast Asia facilitated the clandestine transport of rice and other foodstuffs from nearby areas to Singapore, while the city's accumulated pre-war stocks of gold and other tangible wealth provided readily accepted means of payment.Footnote 26 Middle class Singapore relied partly on the extensive black market selling of jewellery, gold, furniture and other tangible possessions to maintain nutrition. One set of dealers trading in jewellery and property and operating mainly in the High Street or Chulia Street off Raffles Place, bought from a middle class ‘parting with family heirlooms in order to stay alive’. Other dealers with the necessary contacts purchased these goods to sell to Japanese civilians or to give as presents to Japanese military officers who handed out contracts.Footnote 27

Black markets, however, also performed two vital, much wider functions than middle class survival. Both helped to put food within the reach of a range of urban consumers. One was, in the absence of well-functioning markets, to draw food to Singapore by compensating sufficiently for the effort of producing supplies, and then the risk and danger of transporting them clandestinely from surrounding areas. Given the illegality of transporting food beyond small areas and its scarcity, the more food that black markets drew into cities the lower was its price there.

Second, while black markets undoubtedly re-allocated food in favour of the better off, they also provided substantial employment in a burgeoning informal economy. This helped to replace pre-war work, much of which had disappeared, and to accommodate the large increase in hawkers and street vendors characteristic of wartime Singapore. Much of the retail black market distribution of food and other basic goods was through coffee shops and hawkers, since those in successive layers of ‘wholesale’ distribution assessed contact with the public as too risky.Footnote 28 A few black market kings, known in Singapore as ‘mushroom millionaires’, became rich, if, at least initially, perhaps mainly in Japanese paper money. But profits also filtered down and into local communities although also frequently to corrupt Japanese officials.Footnote 29

For the many unemployed and older and less agile Southeast Asians, chronic shortages opened a new job opportunity. In urban Malaya, for those lacking other work, queue-standing and the sale of rationed goods at enhanced prices was ‘always a possible source of livelihood’.Footnote 30 Large numbers of Singapore's pre-war household servants left this employment because ‘they could earn much more by joining the “queues” for cigarettes, for fish, for meat’. ‘Queuing up’ became a major profession and a way of life for the poor. When successful, ‘the proceeds of a long wait could be disposed of at ten times the sum paid’.Footnote 31

During the occupation, Singapore was not affected by famine because Malaya was not densely populated; because the city offered Southeast Asia's greatest black market opportunities; because of the port of Singapore's advantageous geography; because the pre-war commercial relationships between Singapore traders and their counterparts in surrounding countries facilitated exchange; and because of a realism on the part of Japanese administrators which gave scope to the ingenuity of the city's Chinese population in exploiting black market opportunities as well as, late in the war, allowing new, legal ones.

Finance: Making Singaporeans pay Japan's costs of occupying the city

This section first considers the overt methods of various direct and indirect taxes as well as savings campaigns that Japan used to try to extract resources from Singaporeans. We then consider Japan's more subtle, and to Singaporeans less obvious, means of financing occupation: printing money. That had the benefit for Japan of being able to shift the cost of occupation onto all Singapore's residents, but it also disproportionately disadvantaged those with relatively fixed money incomes and contributed to the collapse of the economy.

The occupied can be made to pay for occupation through the occupier selling bonds to banks or to the public, through taxation, and through printing money. Although the destruction of the pre-war European banking system including the three great British banks — the Hongkong and Shanghai, the Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China, and the Mercantile Bank of India — effectively ruled out bonds as a way for the Japanese to finance occupation, taxation remained a possibility. That was difficult, however, because Singapore depended heavily on exports of rubber and tin from Malaya and Indonesia and selling a return flow of consumer goods and manufactures to these economies. Once Japanese occupation cut off Singapore and the rest of Southeast Asia from global, chiefly Western, markets, the Singapore economy collapsed and, with this, so too did its tax base.

To try to mobilise finance, Japanese administrators initiated savings campaigns including compulsory post office saving. Additionally, numerous new taxes were introduced in an attempt to retain pre-war tax arrangements and exploit them as much as possible. Chinese businessmen were an easy target for new taxation. The most notorious taxation, labelled a donation by the Japanese, was a ‘voluntary’ 50-million dollar gift from Chinese businessmen. No doubt in part it aimed to limit inflation by taking currency out of circulation, but the donation must also have been partly intended to cow influential Chinese opposition to occupation.Footnote 32

Over the course of the war, the Japanese administration instituted lotteries and encouraged gambling as ways to tax. Gambling was farmed out and the Shaw brothers, leading figures in post-war Singapore society, are said to have become prosperous by virtue of gaining a licence to run gambling farms.Footnote 33 Japanese officials began lotteries like the Southern Dream Lottery (Konan Lottery) and also levied taxes on amusement parks, including Great World and New World, and on cinemas. Restaurants, coffee shops, waitresses, hawkers, dogs and fishing licences were also taxed. So too were prostitutes, to try to generate revenue from the great wartime spread of prostitution.Footnote 34 But taxes, like savings, raised only relatively small amounts of finance.

The lack of other good revenue sources left money creation as the main way that Singaporeans paid for the Japanese Occupation, a financing method that inevitably led to high and rising inflation. Money, like any commodity, can be taxed, and governments can finance themselves, partly or for a period even largely, through monetary expansion and therefore seigniorage, defined as the revenue that governments obtain from their right to issue money and the difference between the cost of printing money and what it will buy.Footnote 35 So long as people hold money, inflation acts as a form of tax on it. Money is the tax base and inflation the rate of taxation. The effective taxation of money, and so seigniorage as a sustainable revenue source, relies on the public being willing to hold currency issued by the government. That, in turn, depends partly on avoiding too much inflation. In Singapore, it also depended on outlawing the use of any money except that issued by the Japanese and enforcement through torture or death for anyone transgressing the law.Footnote 36 Even so, eventually, if prices continuously increase, people demand less money because its real value falls and the cost of holding currency rises. And yet money was not easily replaced in Singapore. Barter was not feasible. To be sure, money was soon no longer desired as a store of value due to high inflation. By the war's latter stages, ‘only the most stupid were lulled into a sense of wealth by the possession of such notes’.Footnote 37 Nevertheless, money was still needed for transactional purposes: it was used to pay salaries, to make everyday purchases and payments including for lottery tickets and amusements, and to pay taxes.

Money to finance the occupation of Singapore and Malaya was not difficult for the Japanese to create. Military scrip, unbacked paper money, could be printed at will and at minimal cost. Since the nominal spending power generated was the face value of the notes, the Japanese transferred resources to themselves simply by printing as scrip the required amount of currency. Scrip — printed expressly for Singapore and Malaya — was, as before the war, denominated in Malayan dollars. Now, however, currency carried new, ‘appropriate’ pictures such as the banana plants featured on the Malayan ten-dollar note.

As inflation increased and the real value of Japanese scrip, derisively known as ‘banana money’, continuously fell, the Japanese had to print ever greater quantities of notes to try to achieve the same real (actual) transfer of resources to themselves as previously. Although monetary promiscuity led to extremely high inflation, not until the last stages of the war did this turn into hyperinflation, as defined by Philip Cagan's commonly accepted criterion of price increases of 50 per cent a month for three consecutive months.Footnote 38

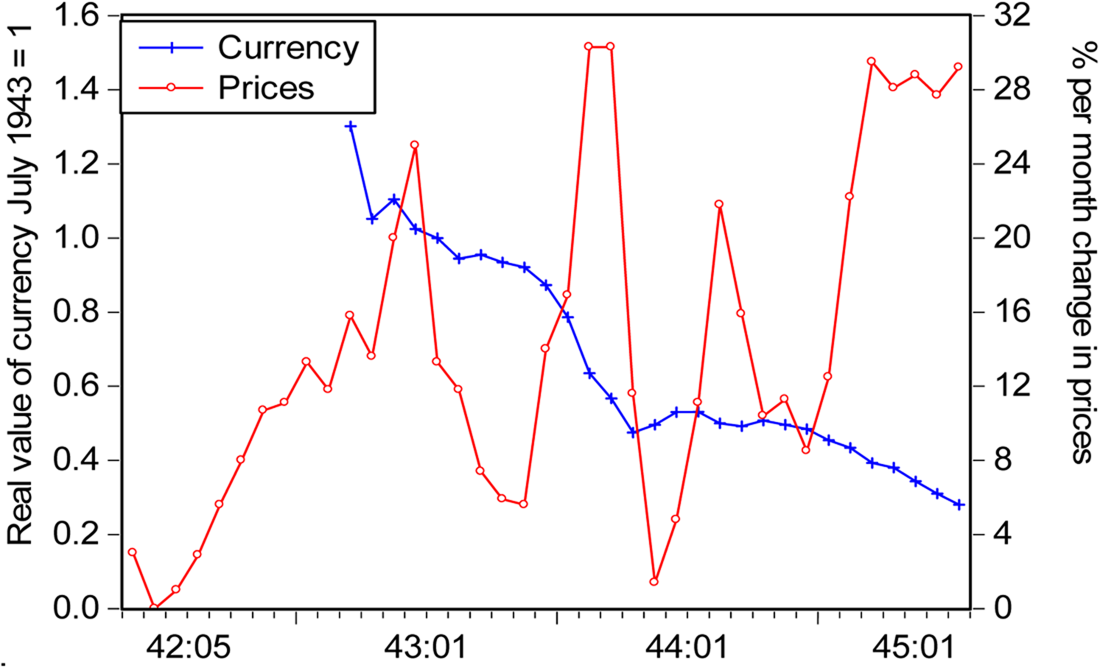

Prices doubled between February and June 1942; were double again in June 1943, and doubled a further time by January 1944. By March 1944, they were rising at some 25 per cent a month, consistent with a yearly increase of around 1,355 per cent. Predictably, most Singaporeans became continuously more unwilling to hold Japanese banana money and as the speed at which it changed hands (its velocity of circulation) accelerated so, too, did inflation. Axis reversals especially eroded scrip as a store of value. In Malaya, ‘Every time there was an Axis defeat, particularly Japanese defeats, prices of goods jumped up. Every Allied victory … and every visit of B-29s over Malaya, caused spurts of prices in foodstuffs. Saipan, Iwo Jima, Manila, Rangoon, and Okinawa were inflation spring-boards.’Footnote 39 Between February 1942 and July 1945, while the money supply rose fifteen-fold, prices increased by a factor of 150. By 1945, Japanese scrip was a fraction of even its 1943 value (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Singapore: End-of-month index of real value of currency and rate of change in prices May 1942–July 1945

Real seigniorage is made up of two elements: the change in real money balances (the value of money adjusted for inflation and measured on the left-hand axis of fig. 1) from one period to the next and the inflation tax, that is the amount by which the private sector must augment its nominal money holdings to maintain the same value of real balances (needed for the transactional uses of money) when inflation is positive. An erosion of the (money) tax base, like that shown in fig. 1, from which the Japanese administration could generate finance from seigniorage caused this revenue to decline. To try to make up for falling seigniorage, the Japanese had to print ever greater quantities of money. That was at the cost of increasing inflation as a tax to very high percentages. Since money was held by everyone, the effect was to levy this taxation on a large number of poor Singaporeans. For much of the war, Japan largely paid the costs of occupying Singapore from the inflation tax component of seigniorage.Footnote 40

Japanese use of Singapore

For Japan, the highly strategic position of Singapore, aptly described as ‘the naval key to the Far East’, is apparent.Footnote 41 Singapore controlled the Malacca Straits and the port added 2,500 miles to the radius of the Japanese fleet, since Japan had no first-class naval base outside her home waters.Footnote 42 In this section we first examine how Japan tried to make use of Singapore's unparalleled locational advantages and its associated communications infrastructure. Attention is drawn to the value to Japan of the nearness of Singapore to the oil fields of Indonesia and the port's facilities to store and ship oil produced there. The section then traces Japanese efforts to adapt Singapore industry to military needs and argues that an attempt under way by mid-1943 to establish the city as an industrial centre was almost certain to fail.

Strategic value

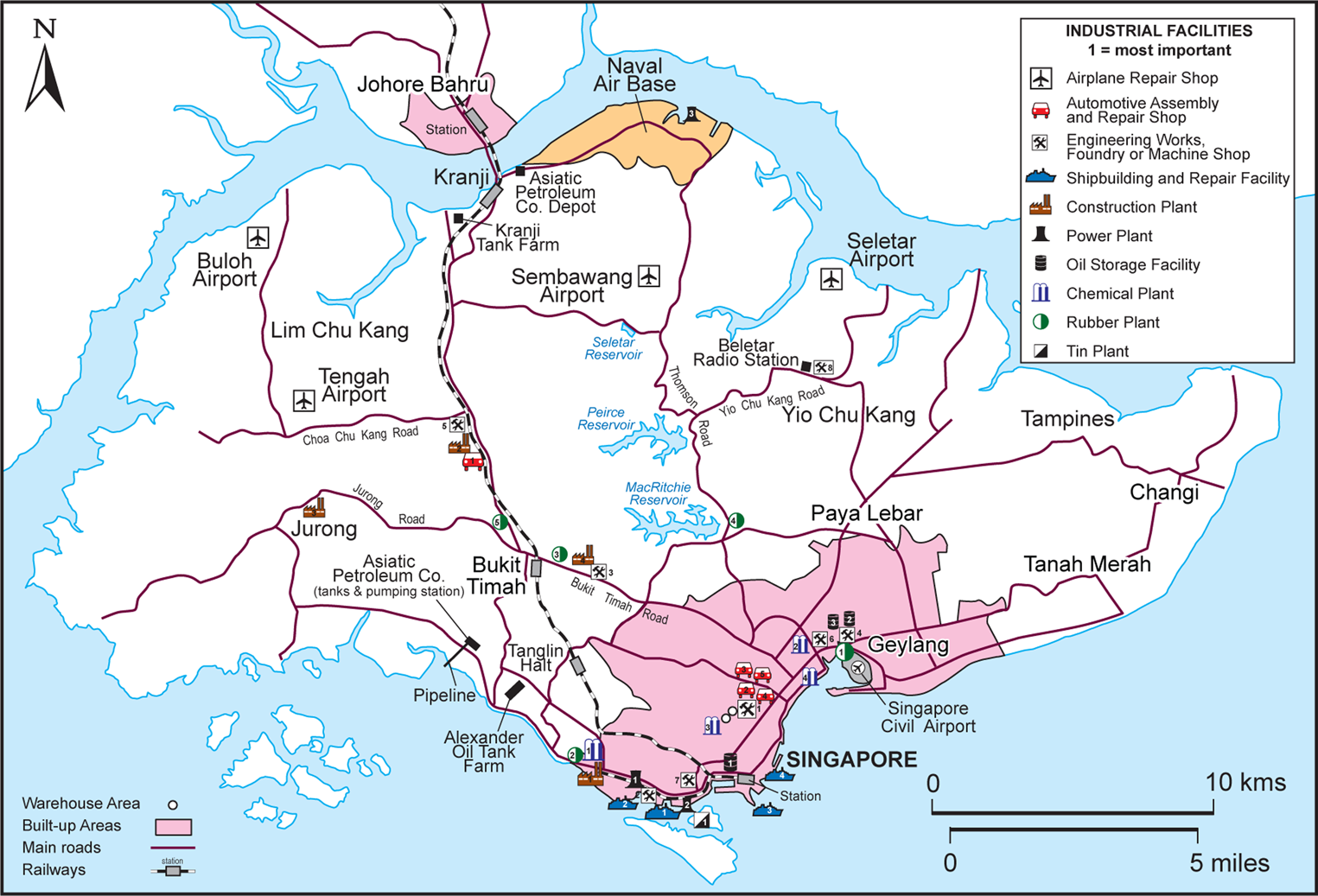

Singapore, along with Saigon, functioned as the nerve centre for Japanese military operations. Malaya and Sumatra comprised ‘the geographical centre of communication’ in Southeast Asia, the nuclear zone of empire, ‘the core of JAPAN's Southern strategy’. All aspects of these areas were to be stringently controlled.Footnote 43 In addition to geographical considerations, the reasons for Singapore's strategic importance are apparent. Singapore's was a natural harbour accompanied by port and ship repair facilities, including the Empire Dock and Naval Base, unmatched in Southeast Asia. The island had four airports as well as the Naval Air Base, the last already adapted for military use; an airplane repair shop along with a similar facility for automobiles; and numerous engineering works, foundries and machine shops (fig. 2). One of these, United Engineers, was Southeast Asia's largest engineering enterprise, with two works in Singapore and branches in the Malay Peninsula as well as elsewhere in Southeast Asia. Telegraph links connected Singapore to all large cities in Southeast Asia and even small up-country towns in the Malay Peninsula and Outer Islands of Indonesia.

Figure 2. Singapore: Strategic facilities

Japanese war leaders, a 1946 US Strategic Bombing Survey found, did not anticipate increasing Japan's miniscule home oil production: ‘their eyes and calculations were fixed on the rich oil fields of the Netherlands East Indies’.Footnote 44 Without this oil, Japan would have to draw on existing stocks which would be exhausted after at most two years and possibly well before.Footnote 45 Sumatra's oil made it too valuable for the Japanese ever to surrender control of the island and partly because of this even towards the end of the war, Japan planned to keep Sumatra and Malaya as permanent Japanese colonies.Footnote 46 Singapore was ideally situated to handle oil from Sumatra and Borneo (fig. 3). Indonesian oil and Singapore's oil storage and transport facilities, of which the depot, tanks and pumping station of the Asiatic Petroleum Company loomed largest, were fundamental to Japan's war effort (fig. 2). Since East Asia was grossly deficit in oil, the same strategic considerations would have applied to a post-war empire that Japan hoped to build as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Figure 3. Indonesian oil production and proximity to Singapore

Attempts to manufacture

After occupying Malaya, the Japanese moved to adapt industry there and use pre-war industrial facilities and machines for military requirements. These efforts focused on Singapore. One reason for this was that Singapore's industrial facilities and manufacturing industry complemented its great military importance as a service, repair and storage centre (see fig. 2). Second, most Malayan industry was already in Singapore. It had Malaya's principal repair facilities, its main engineering firms and its only auto assembly plant, a Ford factory built in 1939.Footnote 47 To augment Singapore's industrial facilities the Japanese brought some essential machinery from home and some from Indonesia.Footnote 48 United Engineers was converted to a munitions factory and, according to one intelligence report, work at the Singapore site continued 24 hours a day on a shift system.Footnote 49 Cement was essential for the war, and since it was not manufactured in pre-war Singapore, the machinery and equipment for cement production had to come from Japan for installation at Batu Caves in Malaya.Footnote 50 Two Japanese firms, the Yokohama Rubber Company and the Central Rubber Company, brought machinery from Japan to manufacture rubber goods, mainly for the military.Footnote 51

Even so, during the war manufacturing in Singapore almost certainly contracted. Decline was caused partly by the difficulties of shifting towards war production — even though the British had already made a start in putting manufacturing on a war footing — and of establishing new management and control structures. Moreover, primary commodity processing, which fell sharply, had accounted for a large share of pre-war manufacturing. Singapore's some 25 pre-war rubber mills became largely redundant; pineapple canning, a major industry before the war, fell into complete decay, and machinery was removed from the factories. The Straits Trading Company's plant at Pulau Brani, an island just off Singapore and formerly the site of one of the world's largest tin smelting operations, had been severely damaged by the departing British. Japanese forces dismantled the smelting plant and removed one of its large generators to a sub-station on Penang Island. Tin smelting, which had needed ten furnaces, was replaced by various units, including some for the manufacture of sulphuric acid, a printing works and, in one furnace, the melting of spent cartridge cases.Footnote 52

By mid-1943, in keeping with self-sufficiency initiatives elsewhere in Southeast Asia, Japan planned to go well beyond existing manufacturing in Singapore. The Production Materials Control Act and the Key Industrial Goods Act aimed to develop heavy and chemical industries in Singapore and other parts of Malaya.Footnote 53 For Singapore, despite an industrial base superior to that in most other large Southeast Asian cities, the establishment of such industries would have marked a major historical departure. Singapore had never been an industrial centre, nor was it located anywhere near one. Pre-war Malaya was ‘dependent upon importation for all machines, plant, iron and steel, raw materials, etc.’.Footnote 54 It had neither capital goods nor chemical industries. Wartime Japanese industry in Malaya was ‘largely equipped by the cannibalization of machinery ex British firms’ workshops’.Footnote 55 For example, to make automobile fuel from rubber ‘Machinery was cannibalized, engine fan belts were made from old airplane tires and smoked sheets, and straw mats were waterproofed as a substitute for unavailable paper or gunny sacks’.Footnote 56

The industrial transformation of Singapore envisaged by Japanese planners would at best have been difficult and was probably impossible. It would have required large quantities of imported goods and a trained labour force. Neither was obtainable under wartime conditions nor quickly achievable even in peacetime. Unsurprisingly, plans announced in September 1943 for heavy industrialisation and in 1944 to construct Malaya as a self-sufficient industrial centre did not come to fruition. An intended Singapore production of large quantities of steel, automobile tyres and electric bulbs failed to materialise.Footnote 57 Like other economic sectors, manufacturing was increasingly hindered by a lack of fuel, lubricants, power supplies, spare parts and transport, which rendered machinery partially, or even wholly, inoperative. Labour became a major constraint. A 1944 Japanese research report found that in Singapore hunger and insufficient public transport reduced production and seriously impeded the war effort through contributing to sickness and absenteeism of factory workers. According to the report, a lack of nutrition left many workers unable to work hard while others were physically drained from time spent on transport.Footnote 58

Why Singapore remained so orderly

Throughout the three and a half years of occupation, the Japanese succeeded in effecting tight control over Singapore's population. That was remarkable because ethnic Chinese comprised three-quarters of the city's inhabitants and many of them felt intense hatred towards Japan due to its ongoing war in mainland China and atrocities there. In this section, we argue that the Japanese controlled Singapore through a combination of terror and food, the former extreme, uncompromising and on occasion arbitrary. No one could deny the primacy of terror in the tight social control that the Japanese effected in Singapore. Nevertheless, food played a significant and, as shortages worsened, an increasingly important role in explaining the tight grip on Singapore's population maintained by the Japanese.

Terror as a social control policy

Japanese terror tactics were immediate and brutal. After occupying Singapore, the Japanese began a systematic mass murder of Chinese as part of a sook ching, or ‘purification by elimination’, a war crime and an occupation strategy reminiscent of the Rape of Nanjing. Sook ching executions were said by the Japanese to be about 6,000 and by Chinese to number as many as 40,000. It seems probable that the actual death toll was at least 20,000, and quite possibly more.Footnote 59 All groups of Singaporeans, even if, unlike the Chinese, considered potential allies, suffered verbal abuse and the ubiquitous Japanese practice of face-slapping for a misdemeanour, which might be failing to bow to a Japanese soldier or official. In Malaya, everyone bowed to Japanese personnel. They also bowed to passing cars since it was unlikely that anyone except Japanese would be riding in them.Footnote 60 Minor offences attracted severe treatment from the Japanese; major ones torture and often execution.

Japanese military police, the Kempeitai, were fundamental to wartime orderliness. Kempeitai methods of interrogation and torture were so brutal that few dared oppose or openly question Japanese rule. Acquiescence was almost total.Footnote 61 Such a civilian reaction is understandable: under Kempeitai control, even Shanghai, notorious for an extensive underworld, relapsed into comparative law and order.Footnote 62 While the military police were to be avoided at all cost, as one moved about Singapore, any Japanese were to be given a wide berth. As a Singapore Eurasian later recalled, Japanese sentries were to be circumvented if possible because you would be slapped a couple of times or tied to a lamp-post if you failed to bow to a sentry. In Singapore, ‘[I[t was just the law of the sword, they used to chop off heads and all that kind of thing … a kind of strict military discipline control over the city’.Footnote 63

The response of the military police and Army to any form of protest in Singapore was truckloads of troops and arrests.Footnote 64 After someone in Bukit Timah raised a Chinese flag, for example, the Japanese came two days later and ‘took over and then they slaughtered all the Chinese in Bukit Timah’.Footnote 65 Anyone arrested by the Japanese was in danger of being brutally tortured and then killed. Torture, perhaps followed by decapitation as a favoured form of execution, was systematically and routinely used by the military police and also practised by the Japanese military.Footnote 66 Terror tactics were less a product of sadism than due to the implementation of a policy of intimidating and terrorising the population to secure social and economic control. Lee Kuan Yew makes this point.Footnote 67

Numerous independent contemporary accounts of Kempeitai torture, graphic and harrowing, suggest that it would have been better to die immediately than be tortured, even if one might have survived. In fact, execution frequently followed torture. It was standard practice to inflict brutal torture on anyone suspected of transgression before interrogating them. To be suspected of any crime, for example dealing in British or American currency, listening to the BBC or smuggling, was almost certain to lead to torture.Footnote 68 If one person in a house was wanted the Japanese might torture everyone in residence. The practice of pulling out a victim's finger nails was frequent and vicious beatings usual. Water torture, followed by jumping on the stomach until water came out of the victim's orifices, was said to be the most dreaded of the Japanese methods.Footnote 69

The shortage economy and social control

Paradoxically, acute food shortages worked to help bolster Japanese social control, not to lessen it, because the Japanese distributed substantial food supplies through rations and in exchange for work. Although Japanese distribution fell short of meeting the food requirements of Singaporeans, it was sufficiently important that to stay alive most Singaporeans had to rely on Japanese administrators for food. The effect was to encourage dependence and dampen the likelihood of rebellion. Among Singaporeans the Japanese offering of rice for work became an ‘infallible draw. People who hated the Japanese had eventually to submit because of rice … many women and girls of poor families succumbed to necessity and became Japanese mistresses because of rice’.Footnote 70

Rationing

The Japanese administration linked food rationing directly to social control through the ten-house system and strict reporting. In Singapore, this tonari-gumi or neighbourhood system, founded in September 1943 and called the Peace Preservation Corps, functioned simultaneously as a basis for the distribution of rations and means of tracking the population. The Corps comprised 5,500 neighbourhood units of 30 households, 550 subsections, and 55 sections, each with a leader. Through registering all families in a neighbourhood, the Corps, as well as a basis for overseeing rationing, could monitor local behaviour and serve as a form of census.Footnote 71 Behaviour infringements were likely to be punished severely.

Throughout the war, rations, although increasingly inadequate in themselves, reduced the risk of grossly inadequate nutrition by putting a floor under food availability. At first and from March 1942 until November 1942, rice rations of 20 catties (26.6 pounds) per person per month were not impossibly short of estimated daily pre-war consumption in Malaya of 1.1 pounds (499 grams) per capita.Footnote 72 Beginning in November 1942, with the worsening rice rations, Japan's rationing authorities began to supplement the distribution of rice with small amounts of rice substitutes, principally tapioca. That did not, however, in any way make up for continuous falls in rationed rice. By February 1944, the monthly ration for the Japanese was 12 catties, although in July it was increased to 19 catties (see table 4, n. 8). The February 1944 ration for Singaporeans classified as doing non-essential work was much less: just 8 catties for males, 6 catties for females and 4 catties for children (table 4).Footnote 73 Since minimum daily calorie requirements are at least 1,700 calories for productive work and 2,000 to 2,250 calories for an adequate food intake, the February 1944 ration of 8 catties (officially reckoned as 160 grams and 544 calories a day) left non-essential workers facing very considerable food deficits. They had little choice except to turn to Japanese employment or non-rationed sources of food including the black market.

Table 4: Municipal Singapore rice rations, Mar. 1942–May 1945 (rice catties per month unless otherwise specified)

Notes: 1 catty = 1.33 lbs. 1. 20 Mar. 1942 onwards: Official rice prices were (per catty): lime rice: 7 cents; whole rice 10 cents; broken rice 8 cents. 2. 16 Nov. 1942 to 31 Jan. 1943: 1 catty of soya beans per person per month. 3. 7 Mar. 1943: Sale of tapioca and soya bean bread. 4.15 Feb. 1944: Tapioca noodles were sold to the public 1 catty per card at all markets. 5. 17 Apr. 1944: Tapioca flour bread rations were distributed through retailers at 6 cents a loaf at: 1–3 persons, one loaf; 4–6 persons two loaves; 7–9 persons three loaves and so on. 6. Apr. 1944: Because of confusion in the markets, the sale of tapioca noodles was entrusted to heads of wards. They in turn sold to heads of teams for onward sale to householders. Rations every three days were: 1 to 5 persons: 1 catty; 6 to 10 persons: 2 catties and so on. Municipal and government employees were given 7 catties of rice extra per month. 7. May 1944: Essential workers received 5 catties of rice extra each from private importers' stock (one month only). 8. July 1944: Japanese rice ration increased to 19 catties of rice and 2 catties of pulet (or pulut, meaning glutinous rice in Malay) or bee hoon (rice vermicelli) per person. 9. Sept. 1944: 3 catties of extra rice to the public from private importers stock at $2.80 per catty. 10. Nov. 1944: 1 catty rice, 1.5 catties rice flour and 0.5 catty beans available from private importers stock all at $2.80 per catty. It is unclear how much was available per person or over what time period. 11. Dec. 1944: Supply to the public (but not municipal and government servants) of bread and tapioca noodles stopped. Sale of 5 catties of rice and cereals to the public from private importers' stock. 12. May 1945: Bread supply to municipal and government servants stopped.

Source: NA WO 203/4499 Rice—SEAC territories Oct. 1945. See also, WO 203/2647, ‘Summary of economic intelligence no. 130, 15 Oct. 1945’, p. 5.

Working for the Japanese

The ability to trade food for work allowed the Japanese an even more direct means of social control than the distribution of ordinary rations. Employment in a Japanese firm or by the military always had the attraction that typically a large share of wages was paid in food. After mid-1943, when the Japanese needed more workers to bolster defences against a probable Allied invasion, they found paying in rice the ‘surest method of securing a work force’.Footnote 74 Work for the Japanese became increasingly attractive to Singaporeans as rations fell and as high inflation ate away at relatively inflexible money wages. The power this conferred was considerable since, as one resident later recalled, the Japanese in effect said: ‘If you don't work for us, you don't get any rice’.Footnote 75 Singaporeans who worked for the Japanese were subject to accusations of being sympathizers. However, it is difficult to know how many genuinely sympathized as opposed to working for the Japanese to obtain food or housing.Footnote 76 The attraction of this employment to secure a source of adequate quantities of food was further strengthened by the introduction of priority rationing.

The Japanese authorities had to react to the sharp drop in ordinary rations in order to try to maintain work effort at a functioning level among workers essential to the war effort. The response of priority rations in February 1944 both helped to meet the goal of a more effective war effort and strengthened Japanese control mechanisms by increasing dependence on a job with the Japanese military or firms. Added to the priority rice ration were some other rationed foods and a small money wage. Nevertheless, even priority workers could suffer from a lack of nutrition and priority rationing fail to achieve the intended aim of eliciting work effort. One reason for this was that the workers often sold part of their priority rice on the black market, leaving themselves short of the main food staple. A further nutritional impairment was that virtually every other constituent of a balanced diet, including oils, fats and protein, was in short supply, so that black market proceeds from selling rice bought only small quantities of other essential foods or goods like soap or clothing.

In Singapore in March 1944, priority rationing applied to around 130,000 Singaporeans. These included most, if not all, of a workforce of 70,000 employed by the Navy and Japanese companies and an additional 60,000 with food priority on the basis of their importance to the war effort. While the general ration provided near the bare minimum for survival, workers with priority rations could obtain as much as 2,000 calories a day. Labourers working for the Army were especially favoured and had a monthly rice ration of 23 catties (officially reckoned as 460 grams and 1,564 calories a day). Even for those less favoured, in 1944 the officially-listed daily ration of 420 grams (1,428 calories) of white rice and 1,922 calories overall was far above average Singapore consumption, although often some of these rations were sold on the black market (table 4).Footnote 77

Japanese use of food as an incentive through priority rationing for about 130,000 Singaporeans would have helped to feed about two-fifths of Singapore's wartime population, assuming that each worker usually had, additional to himself, at least two persons partially dependent on food brought home from work. The contribution might be roughly the same even if there were no immediate dependants because recipients often sold part of their priority rations. In this way, Japanese-supplied food spread beyond those without a direct connection to Japanese employees. The sale of priority rations helps to explain the vibrancy of Singapore's black market.

Nutrition and health

Detailed health and nutrition data for Singapore and Kuala Lumpur help an appreciation of how close Singapore was to famine and so the importance of Japanese-controlled food supplies and the black market in its avoidance. The data also draw attention to the impact of the occupation on living standards in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur and allow comparison of the health outcomes in the two cities. In both, malnutrition was widespread and serious by the end of the war. By 1945 in Singapore, ‘a very large percentage of the population was suffering from serious under-nourishment’.Footnote 78 Between about two-fifths and two-thirds of Singapore school children were malnourished by pre-war standards.Footnote 79 Most children showed stunted growth and very poor musculature.Footnote 80

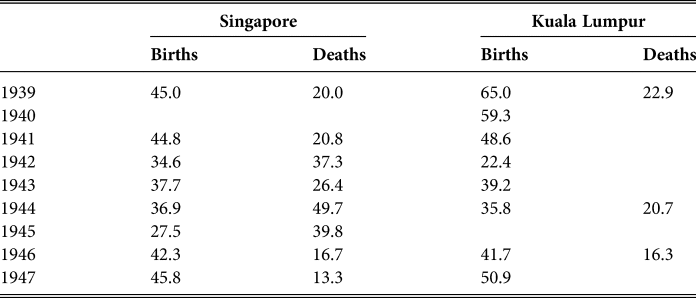

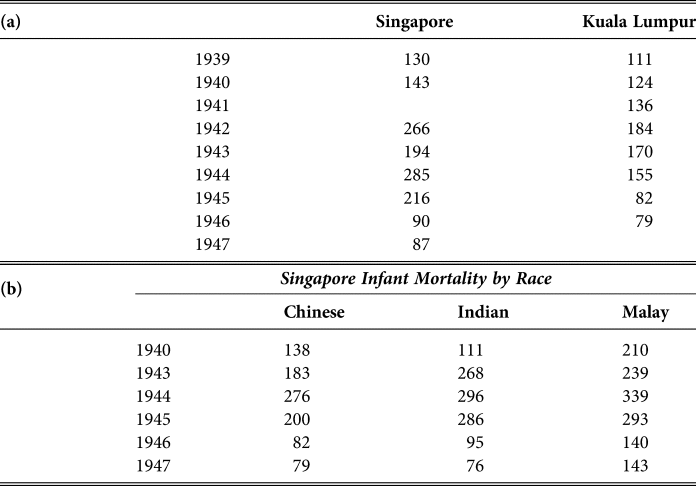

In Singapore and Kuala Lumpur alike, health services and anti-malarial programmes were, as in much of Japanese-occupied Southeast Asia, progressively abandoned. Death rates surged due to declining health services, serious shortages of quinine, reduced availability of clean water, an end to imports of condensed milk and inadequate diets. Evidence for this last was a much higher incidence of beri-beri (dietary deficiencies associated with an overload of carbohydrates) and infantile convulsions (poorly fed women unable to obtain milk or suckle infants, and infants weaned on cereals).Footnote 81 Between 1941 and 1944, Singapore's crude death rate more than doubled. Birth rates fell more slowly than deaths rose, but by 1945 Singapore's crude birth rate per thousand of 27.5 was not much above half its 1940/1941 average and far below the crude death rate of 39.8. In Kuala Lumpur the birth rate approximately halved during the war, but, as in Singapore, largely recovered in 1946, and in 1947 regained its pre-occupation level (table 5).

Table 5: Singapore and Kuala Lumpur: Crude birth and death rates 1940–47, (births and deaths per 1,000 population)

Notes: 1. For 1940, 1942, 1943 and 1944 for Kuala Lumpur, births are estimated using estimated mid-year population figure of 144,414 and are indicative of trends only. Figures for 1943 and 1944 are almost certainly overstated due to wartime population inflows. 2. Death rates, in particular, may be understated for Singapore and Kuala Lumpur due to non-reporting.

Sources: Singapore, Annual report on the registration of births and deaths, 1940–47, pp. 6, 8, 12; AN 1957/ 0289720, Report of the Kuala Lumpur Sanitary Board, 1939, p. 22; 1957/0292046. RC Selangor 269/1947, Report of the Kuala Lumpur town board, 1946, p. 22; and 1957/0294190, Selangor Secretariat 554/1948, Report of the Kuala Lumpur town board, 1947, p. 17.

Infant mortality is a good measure of health trends and, in particular, of access to clean water. In Singapore and, though less so, in Kuala Lumpur, the infant death rate rose markedly during the Japanese Occupation (table 6). Between 1940 and 1942, an 86 per cent rise in Singapore's infant death rate and 48 per cent increase in Kuala Lumpur's compares with a 40 per cent increase in occupied Europe over a similar period and emphasises how quickly and how greatly conditions deteriorated.Footnote 82 Between 1942 and 1945 in Singapore, infant deaths accounted for a quarter of total deaths but for a much higher share of the increase in deaths. In comparison to 1940, between 1942 and 1945, while average annual deaths excluding infants increased by 56 per cent infant deaths rose by 256 per cent. Among Singapore's main racial groups, Indians suffered the largest increase in infant deaths, but in 1945 in absolute numbers remained just behind the Malays. Between 1940 and 1944, infant death rates for Singapore as whole doubled, but they were 2.7 times higher among Indian infants (table 6).

Table 6: Singapore and Kuala Lumpur infant mortality rates 1940–47 (deaths per 1,000 children under 1 year old)

Notes: For Kuala Lumpur data are for Jan. to Oct. for 1941, May to Dec. for 1942 and Sept. to Dec. for 1945.

Sources: Singapore, Annual report on the registration of births and deaths, 1940–1947, p. 9; AN 1957/ 0289720, Report of the Kuala Lumpur Sanitary Board, 1939, p. 22; AN1957/0292046, RC Selangor, Report of the Kuala Lumpur Town Board, 1946–1948, p. 23.

To some extent, Chinese adults and also their children were probably less seriously affected nutritionally than Indians or Malays because Singapore's Chinese population included a substantial middle class. On average, Chinese had higher pre-war incomes and more assets than Indians and Malays and so were better able to turn to wartime black markets than the other racial groups. Chinese also seem to have adapted more successfully than either Indians or Malays to food shortages. A significant proportion of Chinese lived on the outskirts of Singapore, working as market gardeners. Singapore Malays, although not self-sufficient in rice, also had advantages in comparison to Indians. Malays tended to live outside central Singapore where they were likely to have at least some access to land on which root crops could easily be grown.

Indians, overwhelmingly Tamils, suffered especially, because many had come to Malaya as contract workers, and when the demand for rubber disappeared so too did their jobs. By the end of the war, the number of people living on rubber estates had fallen from a pre-war figure of 370,000 to 190,000 and actual labourers from 148,000 to 70,000, of whom some 28,000 now grew only food.Footnote 83 Some of these workers are likely to have drifted to Singapore. A lack of entitlements frequently deepened the predicament of the unemployed Indian estate workers. In contrast to the 1930s, when there was an entitlement to return at no cost to India, the former plantation workers now had no way to get home.Footnote 84 Indians who had come alone to Malaya might be without family or kinship networks which would likely have afforded some entitlement to help. Furthermore, unlike other ethnic communities, Indians lacked institutional support and this further compromised their position.Footnote 85

Conclusion: Medium- and long-term effects of occupation

The fall of Singapore, Churchill later wrote, was ‘the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history’.Footnote 86 It also marked, as has been argued, ‘a significant watershed in Singapore's political and constitutional development’.Footnote 87 Japanese Occupation and British humiliation hastened the end of colonialism although this did not occur in the Malay Peninsula and Penang until 1957 and fully in Singapore only in 1963 as part of Malaysia. After the war, the approaching demise of colonialism led to much heightened political discourse and labour unrest, the latter initially exacerbated by the inheritance of high wartime inflation. As Lee Kuan Yew remarked of the effect of wartime occupation, ‘there was no return to the old peaceful, stable, free-and-easy Singapore’.Footnote 88 The social and economic impact of occupation at least partly accounts for post-war political change and in this concluding section we try to analyse some of these legacies.

The Japanese made determined efforts to instil Japanese culture and ways of thinking in Singaporeans but these efforts were markedly unsuccessful. Japanese behaviour during the occupation was, if with some notable exceptions of individual kindness, so unattractive and food and goods so scarce that not many could have wanted to emulate the Japanese. Added to this, the Japanese language, Nihon-go, is not easily learned and few resources, either teachers or books, were available to teach it.

Large numbers of Singapore schools were closed and if they reopened it was usually to try to teach Japanese and improve pupils spiritually. ‘Education’ consisted largely of compulsory mass physical exercise and the rote learning of songs and a few Japanese phrases. The fall of Singapore was described as the beginning of 3.5 years of ‘educational twilight’ throughout Malaya.Footnote 89 Older Southeast Asians were encouraged to speak Japanese with slogans like one in Singapore: ‘Do you wish to always be a rickshaw puller? If not, learn your Nippon [Nihon]-go’.Footnote 90 Even a smattering of Japanese could facilitate rapid promotion.Footnote 91 Singapore's first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, just 19 years old when Japan invaded, was among those who saw the advantages of learning Japanese and by doing so got a job at Domei, the military-controlled Japanese news agency.Footnote 92

Chin Kee Ong felt that ‘Given a further five years, her [Japan's] programme of Nipponisation would be so consolidated that all of East Asia would be thoroughly conquered politically, economically, spiritually and culturally.’Footnote 93 However, slight Japanese cultural success with Singaporeans and the antipathy most felt towards their occupiers casts serious doubt on Chin's view. The more trustworthy analysis, also from someone who lived through the occupation and writing with the additional advantage of historical perspective is Lee Kuan Yew's. In Taiwan, he observed, Japan had managed to gain an acceptance of its administration and culture but it never succeeded in doing so in Korea. Lee went on to suggest that Malaya was a sufficiently young, diverse and culturally malleable society that acceptance of Japanese rule and thinking would have come, but only within 50 years.Footnote 94

Wartime scarcities and almost universal poverty bred corruption and decadence throughout Malaya. In Singapore, gambling and brothels were seen everywhere.Footnote 95 Singapore became ‘one big city of gamblers’ as everyone tried to supplement their incomes.Footnote 96 The Singapore amusement parks, Great World and New World, were gambling centres and, in all, about 300 gambling houses were scattered over the city.Footnote 97 As well as Singapore, Malaya had two other ‘Monte Carlos’, in Seremban, Negri Sembilan, and Kampar, Perak.Footnote 98

The black market, which had become a way of life in occupied Singapore, continued to flourish after the war.Footnote 99 For all of Malaya, the effect of the Japanese Occupation was summed up as ‘four years of psychological and physical deterioration’.Footnote 100 After the war, Japanese scrip was declared worthless and could be picked up freely from the gutters. Re-starting a monetary economy was not, however, instantaneous and for some time many people had no money. Barter was a partial substitute and cigarettes served as a form of money. Although they ‘could buy almost anything’, few people except the British military had any cigarettes.Footnote 101

Japanese ‘comfort’ stations, brothels for Japanese military and civilian personal, added to the decadent air of occupation. Almost immediately after Singapore fell, the Raffles Hotel was used by Japanese officers as a comfort station.Footnote 102 For non-commissioned officers and enlisted men, comfort stations were typically assembly-line operations and it was in these that the women suffered the most degrading and sub-human conditions. Almost any large building might be converted to a comfort station by partitioning off many small rooms. The Singapore Chinese Girls School became a comfort station, as in Penang did the otherwise nondescript Tan Lock Hotel.Footnote 103 Women who did not comply with the expected regime were forced to through being beaten or restrained.Footnote 104

The social consequences of Japanese conscription of women as ‘comfort girls’ for the troops, the closing of schools, a breakdown in social services, and the spectre of starvation lasted well beyond the end of the war. The convergence of all these aspects of Japanese occupation in Singapore ‘made easier the revival of the practice of selling female children to brothel keepers and others who trained them for prostitution’. In 1946, Singapore's medical authorities drew attention to the large numbers of girls aged 10 to 14 appearing for the treatment of venereal disease.Footnote 105 The Japanese presence encouraged hasty marriages in Singapore, many of which survived after the war on shaky foundations. There were also de facto wartime Chinese–Japanese marriages, but these involved girls outside the existing social structure and norms.Footnote 106

The Japanese Occupation did not leave a legacy of industrialisation; Singapore's industrial success began only in the late 1960s, and is not explained by its Second World War experience. During the war, Japanese efforts to develop Malayan industry had, despite many failures, some success. But new factories and industries were dictated by necessity and not by any consideration of commercial viability.Footnote 107 By 1947, ‘many of the mushroom industries of the occupation folded up in the face of competition with imported goods which were both better and cheaper’.Footnote 108 The sole purpose of most wartime industries was ‘to meet the urgent needs of war production and their equipment was of poor quality and their design often inefficient. Few of them had any prospect of a permanent future’.Footnote 109

The wartime fall in Singapore's GDP is unknown but was undoubtedly large, perhaps half or more, due mainly to loss of trade and all its associated services, and this GDP was lost forever. But recovery in Singapore was rapid, due especially to relative post-war political stability unlike almost everywhere else in Southeast Asia. By 1949 per capita GDP in Singapore exceeded its pre-war level. Singapore's historic orientation towards the global economy and determination to be part of it were not shaken by the Second World War. The city quickly reverted to its pre-war strongly globally oriented outlook and, helped by the Korean War boom, resumed its pre-war role as a port which handled rubber and tin as two of Southeast Asia's staple exports. The Second World War and the Japanese Occupation do not mark a turning point in Singapore's economic history, but rather a deeply unwelcome, painful interlude in it.