An Indigenous petitioner might travel for days to have an audience with the viceroy of New Spain, in the jurisdiction of the special Indian court called the Juzgado General de Naturales. Once in the huge, bustling capital of Mexico City—its population was around 60,000 at the turn of the eighteenth century and at least twice that by 1800—a legal pilgrim would traverse orderly, grid-like streets in the city center, where colonial elites fixated on the unruly presence of Indigenous residents and launched ceaseless segregation schemes over the centuries.Footnote 1 With no friends or acquaintances in the big city, perhaps the traveler would lodge at the Real Hospital de San José de los Naturales, which doubled as an inn.Footnote 2 The hospital was funded by a tax on Indigenous men set at the amount of a medio real, a half real, valued at about 1/16th of a peso. A half real was, in fact, the same quantity levied annually on native men of tributary age in the Viceroyalty of New Spain to support the personnel and functioning of the Juzgado General de Naturales (Figure 1).

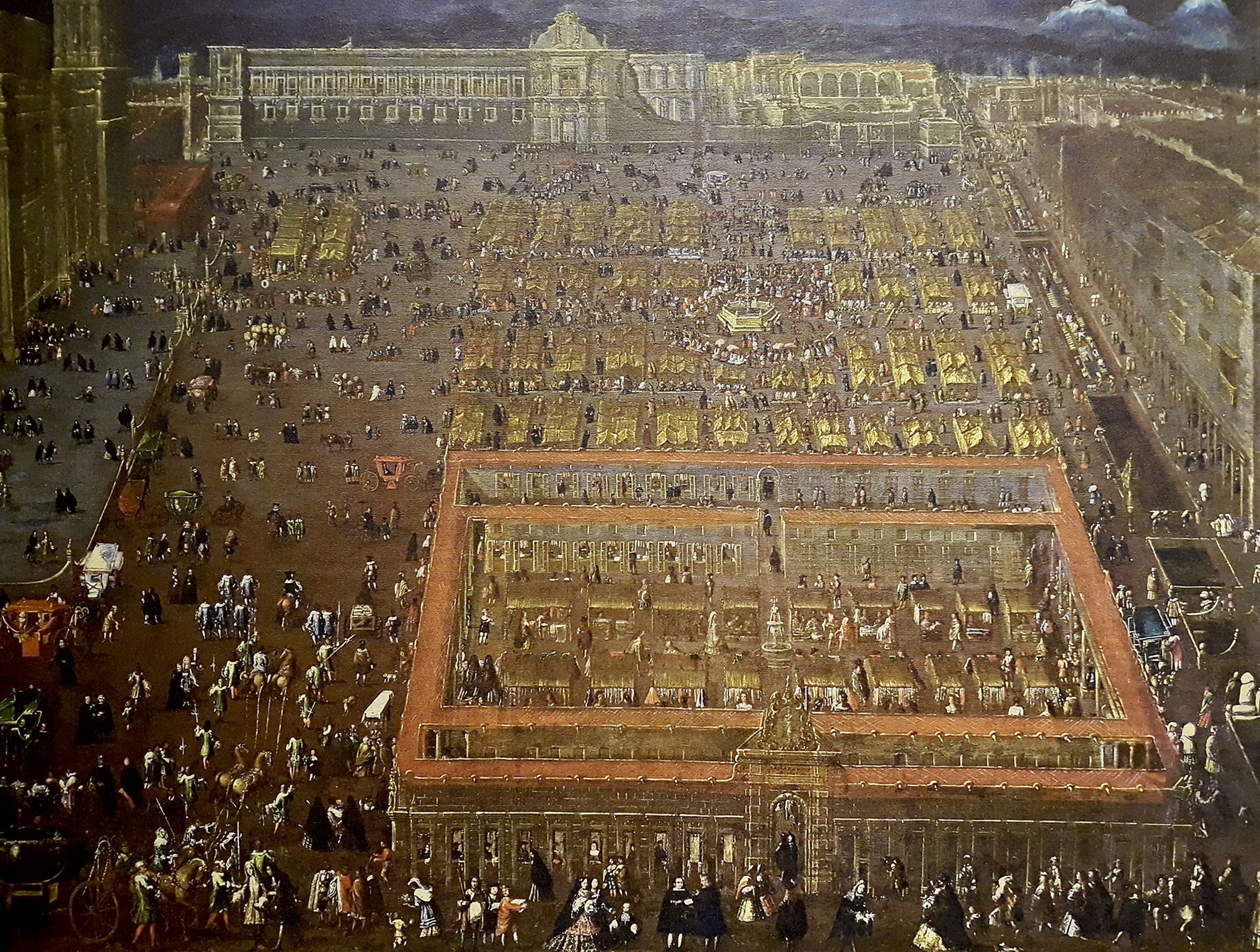

Figure 1. Cristóbal Villapando, Vista de la plaza mayor de México.

From the Real Hospital de San José, petitioners would have approached the zócalo, or central plaza, from the west, as depicted in this painting by Cristóbal Villalpando at the turn of the eighteenth century. There, they would have passed by the famed market known as the Parián, entering the exceptionally large, open square, which was flanked on the left by the Cathedral. Treading cobblestones constructed over the rubble of the Aztec Great Temple, petitioners would behold the viceregal palace, a sprawling, block-long, rectangular structure.

As Villalpando's painting illustrates, those who arrived around the turn of the eighteenth century would find only half a palace.Footnote 3 The building had been torched in June of 1692 by rioters protesting high grain prices and official corruption. The uprising, though composed of a pretty broad cross-section of Mexico City's population, would later be characterized as an “Indian riot.”

This article centers on the materiality of Indigenous legal interactions with the viceroy in this special executive court, the Juzgado General de Naturales, which was located, at least ostensibly, inside the palace. The partial destruction of the palace during the riot of 1692—a year that roughly bisected Spanish colonial rule in Mexico—serves as one focal point for exploring the dynamic history of personal encounters and physical space in the viceregal jurisdiction of the court. By surveying the architectural features of the palace and looking for physical presence within the Juzgado's operation, the court reveals itself as a space of absence and abstraction as much as pomp and procedure.

Established in 1592, the Juzgado de Naturales was a fixture of colonial governance and justice. Based on the tax that funded it, modern historians have dubbed this unique tribunal the “court of the half-real,” producing landmark studies about its functioning.Footnote 4 The Juzgado retrofitted medieval Catholic laws on personae miserablis to a colonial purpose. The petitions and disputes of conquered inhabitants in Spain's American Empire, in particular those involving disputes between native communities or brought against them by Spaniards, could take an express route to royal favor. For Indigenous subjects, these legal disputes were to be gratis, summary and frequently solved by the viceroy's executive decisions in the form of writs.Footnote 5 In other words, using the Juzgado de Naturales, Indigenous subjects could address legal complaints directly to the king's representative in the colonies without having to go through the exacting formalities of regular civil procedure. In exercising his jurisdiction within the court, the viceroy cooperated with the highest judicial body, the Real Audiencia, whose courtrooms were also housed in the palace, by remanding some of these cases to its authority. Critically, he also competed with this and other judicial bodies by himself issuing executive rulings on native suits, effectively reversing decisions or intervening at lower district levels.

It is logical to assume that the interactions that comprised great deal of the business of the Juzgado General de Naturales took place, with the capital city serving as a sort of spatial magnet, drawing Indigenous people from the diverse corners of Mexico to the palace, where they might have a personal encounter with the viceroy, as the king's “living image” in the American colonies.Footnote 6 The language of legal documents, including petitions to the viceroy as well as cases remanded to the Audiencia, renders hearings as personal exchanges. Petitioners and litigants “appeared and said” things before judges and magistrates (parezco y digo, ante). Legal authorities “saw” them and often required not only a recorded response from opposing parties but also their physical appearance before the judge (parecer; ocurrir).

Indeed, most days of the year hearings occurred before very real judges and magistrates who sat on elevated stages called estrados, in courtrooms (salas) adorned with tapestries, ticking clocks and watchful saintly patrons. And in the palace, the presence of viceregal authority and Indigenous subjects was also embodied in other ways. In the parts of the palace structure that were not filled with dedicated courtrooms, especially the northern part of the building which housed viceregal residences and reception halls, courtiers hustled down halls and Indigenous servant girls were busy making tortillas for the royal retinue.Footnote 7 Outside the palace, the viceroy and his wife could be seen around Mexico City, as they processed into the city or hobnobbed with the aristocracy at mass or banquets. Thus, it seems worthwhile to put flesh on the process of colonial law by spotlighting the Indigenous legal experience in petitioning maximum colonial Spanish legal authority right at its heart: the palace. And right at its highest level: the viceroy.

Yet, just as the term “court” referred not to only to a space but also to the accumulated effect of royal retinues, hierarchies and proxies, courts of law (juzgados) functioned similarly.Footnote 8 Beyond gavels and hearings, law in colonial Spanish America flowed through the circulation of texts, which sparked an imagined proximity to royal justice.Footnote 9 Petitioners and litigants collaboratively created legal texts with writers both sanctioned and unsanctioned, often outside the designated halls of justice, in back-alley drinking establishments, in the houses or street stalls of writers-for-hire, or far away from courts in rural regions, where informal papers would be folded into squares and sent on days’ long journeys by mule back to be turned into formal legal documents at courts.Footnote 10

So, while the term “space” is frequently employed metaphorically to discuss justice in the Spanish Empire, it can be surprisingly difficult to discern how physical spaces of law were constituted and used, and how necessary physical presence was to the functioning of viceregal jurisdiction in the Juzgado General de Naturales.Footnote 11 This not for lack of historical attention to the materialities of the court. Woodrow Borah's study of the court of the half real, for example, covers its procedures and personnel, sometimes in exquisite detail. Rather, it is difficult to peer inside this famed jurisdiction because, in a sense, it was at once both half real and hyper-real. Looking inside Mexico City's palace for the physical and material encounters between Indigenous petitioners and the viceroy allows us to extend the “medio real” into a more poetic metaphor about a court that was, in many ways, a palace made of paper, a place of proxies, and a jurisdiction based on disappearances.

****

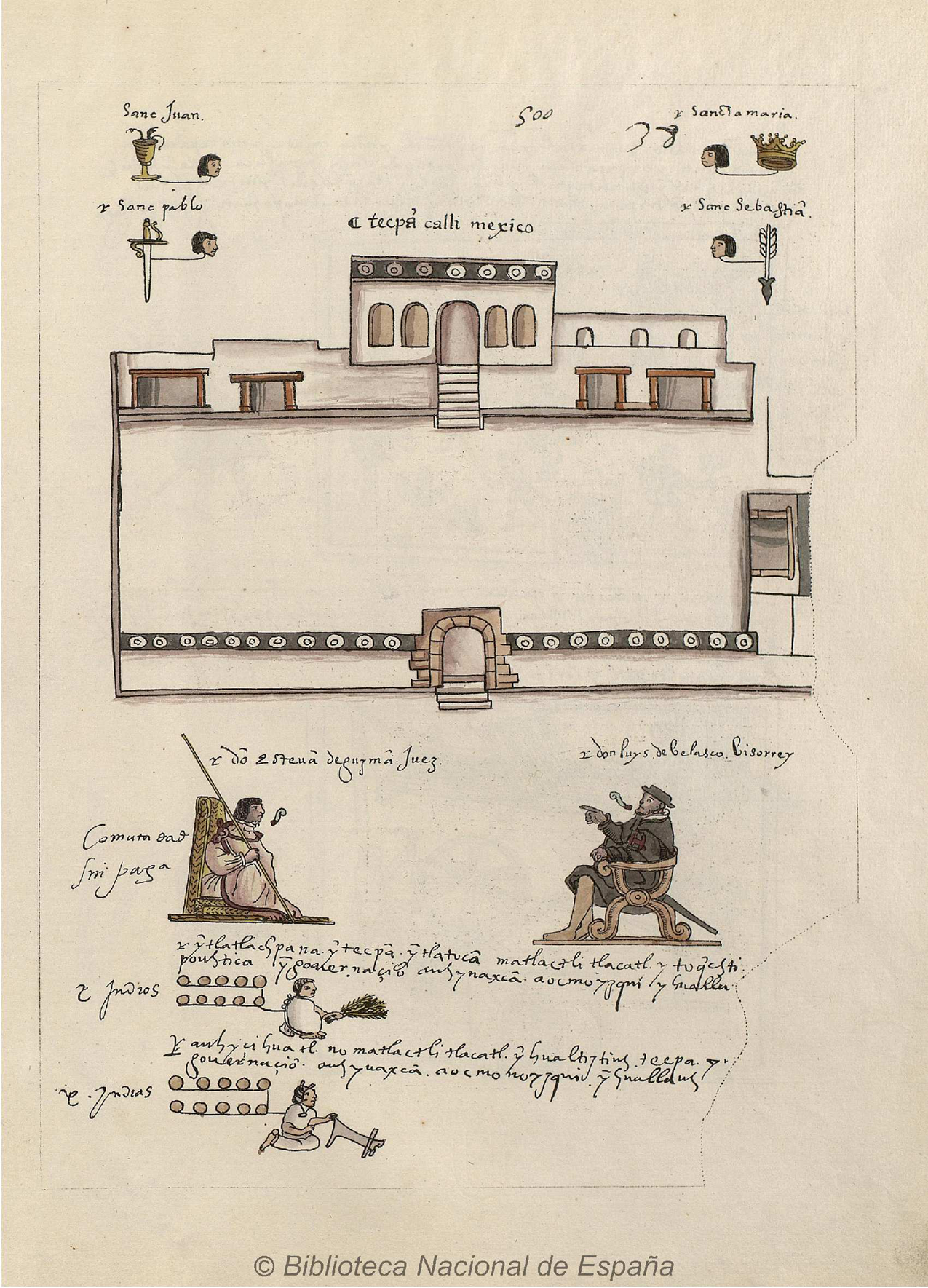

Before the formal creation of the court at the end of the 1500s, the first viceroy of Mexico, Antonio de Mendoza, had emphasized the importance of receiving native petitioners directly, in person and in the palace. His physical proximity to gathering Indigenous subjects was close enough that he warned his successor of the “stench and heat” that they gave off. Despite registering disgust, he persisted in audiences with large contingents because he believed that personal engagement in dispute settlement increased Spanish legitimacy.Footnote 12 The 1564 Codex Osuña, a native depiction portraying the exploitation of Indigenous labor for the workings of the palace, suggests something of a face-to-face encounter between a native judge and viceroy Luis de Velasco at his “tecpán [sic] calli.” The term was a Nahuatl rendering of viceregal authority that combined the concept of a palace, a jurisdiction, and a noble lineage. In this regard, the designation was prescient. Velasco's s son, who thirty years later succeeded him as viceroy, became the legal architect of the Juzgado as a unique court in the palace of Mexico City where the viceroy exercised special oversight of native legal complaints (Figure 2).Footnote 13

Figure 2. Codex Osuña, 1565. Biblioteca Nacional de España.

When Velasco II formalized the court's functioning in 1592, it attracted streams of petitioners from throughout the Viceroyalty of New Spain—some filing duplicate copies of papers related to civil disputes simultaneously before the viceroy and the Audiencia, proliferating papers and legal authority. Others came only to the viceroy, looking for licenses and acts of grace, and still others for writs of “amparo,” or executive, summary rulings that would assist them with conflicts taking place at jurisdictions closer to their pueblos. New Spain's viceroys soon realized that the expansion of their authority over native cases would mean, in the words of one, “acting as an ordinary judge” and working incessantly.

Velasco's successors more rigidly formalized the court's personnel structure, and began to limit personal, if not paper, access to their viceregal persons. Several tried to restrict the number of petitioners who could appear in person at the court to no more than two representatives from the pueblos.Footnote 14 The idea was that the movement of native petitioners in search of justice had to be fettered and populations fixed in place. When Viceroy Gaspar de Zúñiga y Acevedo, the Conde de Monterrey, fine-tuned the functioning of the court at the turn of the seventeenth century, he fretted to the crown about Indians streaming into the city “so far from their lands” and established a series of gatekeeping measures.

The Conde also signaled his own disappearance from the court. Showing up in person to preside over the judicial business of the Juzgado had, he claimed, diminished the dignity of his office. Receiving petitioners in person had resulted in “a certain loss of decorum in a place that stands in (thiniente) for Your Majesty, in seeing public hearings as if [the viceroy] were an ordinary judge over causes of very little importance, overseeing petitions and hearing evidence in suits in front of a lot of people, who [like the petitioners] are also of very ordinary quality, who will notice [only] what they each wish.”Footnote 15

While the viceroy's original presence before Indigenous petitioners might have been a colonial innovation intended to draw authority to his person, the later retreat from public audiences with Indigenous petitioners in the Juzgado system tracked with a broader imperial “disappearance” of the king from courtly ceremonies in Spain during the reign of Felipe II (1556–98).Footnote 16 The king was not, of course, gone forever; subsequent monarchs varied ritual ideologies, playing peek-a-boo with subjects throughout the centuries. Still, it is worth comparing the Conde de Monterrey's concern with his in-person accessibility to Indigenous subjects with an exchange between Mexico and Madrid a half century later. When in the 1660s the viceroy of New Spain inquired about where to place the main altar in Mexico City's Cathedral, the response from the crown was philosophical, pairing royal and sacred power: “in the palaces of princes the lord should not be seen from the door, for respect increases the greater the diligence required in seeking him.”Footnote 17

Over time, the legal process at the Juzgado de Naturales worked to maintain the distance. The growing physical remoteness of viceroy from the time of the Conde de Monterrey on fit within a colonial political ideology that substituted in-person royal favor for legal bureaucracy and access to the royal person for expertise in navigating the labyrinthine halls of justice and its warren of its legal offices. As Borah periodizes it, “by the eighteenth century, as the movement of papers took over in increasing measure, presentation of the petition became more a matter of filing by the Indian agent and examination without the plaintiff's presence.” Meetings with the viceroy eventually took place “only in unusual circumstances.”Footnote 18

The Conde de Monterrey could perform his early disappearing act because he outsourced much of the work to the asesor of the Juzgado, a university-trained magistrate drawn from the Audiencia who served as legal advisor to the court on rotation. But even in-person interactions with this figure became rare. The asesor went from making private recommendations in chambers that the viceroy wrote out and signed, to making the recommendations himself in writing, with the viceroy generally merely affixing his own rubric to those papers, behind closed doors. By the later eighteenth century, many of the records related to the Juzgado show no clear signs that the viceroy or even his asesor were present or touched the papers with any ink at all.

A great deal of the archive of the Juzgado General de los Naturales was overprocessed compared with the autos, or individual papers drawn up in various spaces by various hands that accumulated in civil hearings in the Audiencia or before district judges.Footnote 19 It is possible that the shift to paperwork actually improved the efficiency and accessibility of royal justice. Just because they did not enter the palace did not render the jurisdiction invalid for Indigenous subjects. Indeed, their legal positions and occasionally even their first-person voices can be recovered from the condensed and summary textual records of the Juzgado. Still, access came at a physical remove and with the result of abstracting the court. For example, many of the Juzgado's records from the 1770s contain executive rulings bearing the viceroy's name but showing only the rubric of the chief notary of the governmental office, who scratched out papers containing decisions in a bare office that was adorned only by a single, wood filing cabinet.Footnote 20 At least a couple of times in the eighteenth century, the Juzgado went so far as to explicitly forbid Indigenous subjects from personally appearing at the court, as when it required the district magistrate to tell the natives of Tacuba not to travel bringing gifts of fowl to the court for the Christmas holiday, or when another order went out warning defendants in a civil suit from Ixtlahuaca to refrain from bringing “sinister reports” to the palace.Footnote 21 Whereas the early viceroys used their physical presence and personal encounters with Indigenous subjects as a source of authority, by the seventeenth and eighteenth century, the logic seemingly had flipped, and they viewed personal interactions as possible channels of corruption or influence.Footnote 22

My review of the series “Indios” in the Archivo General de la Nación of Mexico, which houses thousands of Juzgado General de Naturales records, tells us that the court certainly did call for parties to appear in person at the palace at times.Footnote 23 But the patterns are intriguing: of roughly 150 calls that I identified for legal subjects to show up in person in judicial matters (ocurrir or parecer), the vast majority required that parties appear not in the palace but rather in their pueblos, before local secular or ecclesiastical officials. When parties were called to the capital city to appear in person at the Juzgado proper, they were given a window of a set number of days, usually around 15. These calls generally pertained to cases that were determined to belong to the branch of the Juzgado presided over by the Audiencia. Increasingly in the eighteenth century, the order to appear included an indication that the parties could send adequate legal representation rather than appearing in person.Footnote 24 As Yanna Yannakakis shows in her geospatial study of powers of attorney from colonial Oaxaca, a cadre of apoderados, or individuals vested by native communities with power of attorney, traveled regularly from rural regions to Mexico City, and the volume of their journeys to seems to have increased over the eighteenth century.Footnote 25

Meanwhile, a veritable army of bureaucratic buffers moved to keep Indigenous petitioners physically, if not textually, at a remove from the palace. The doormen were charged with filtering out all but the court-appointed representatives of Indigenous petitioners, called solicitadores. Indeed, the question of whether doormen would receive a salary from the half-real levy on Indigenous tributaries for their work ushering petitioners into the Juzgado was an issue of ongoing controversy, highlighting how important their work must have been in dictating who could enter the palace complex to file a petition or attend a public hearing. Solicitadores were agents of the Juzgado, paid by the medio real funds, working on the clock by setting up their desks in the palace corridors each workday between 8 and 11 in the morning and from lunch to close of business each workday. There, they took the oral complaints of petitioners or collected the pieces of paper that they had brought, turning them by formalizing magic into acceptable legal genres to be vetted— by them—in public audiences in the Juzgado on Monday and Wednesday mornings, and Friday afternoons. If not proficient themselves in Nahuatl or another native language, the solicitadores could call on the service of interpreters who were held in the employ of the medio real.

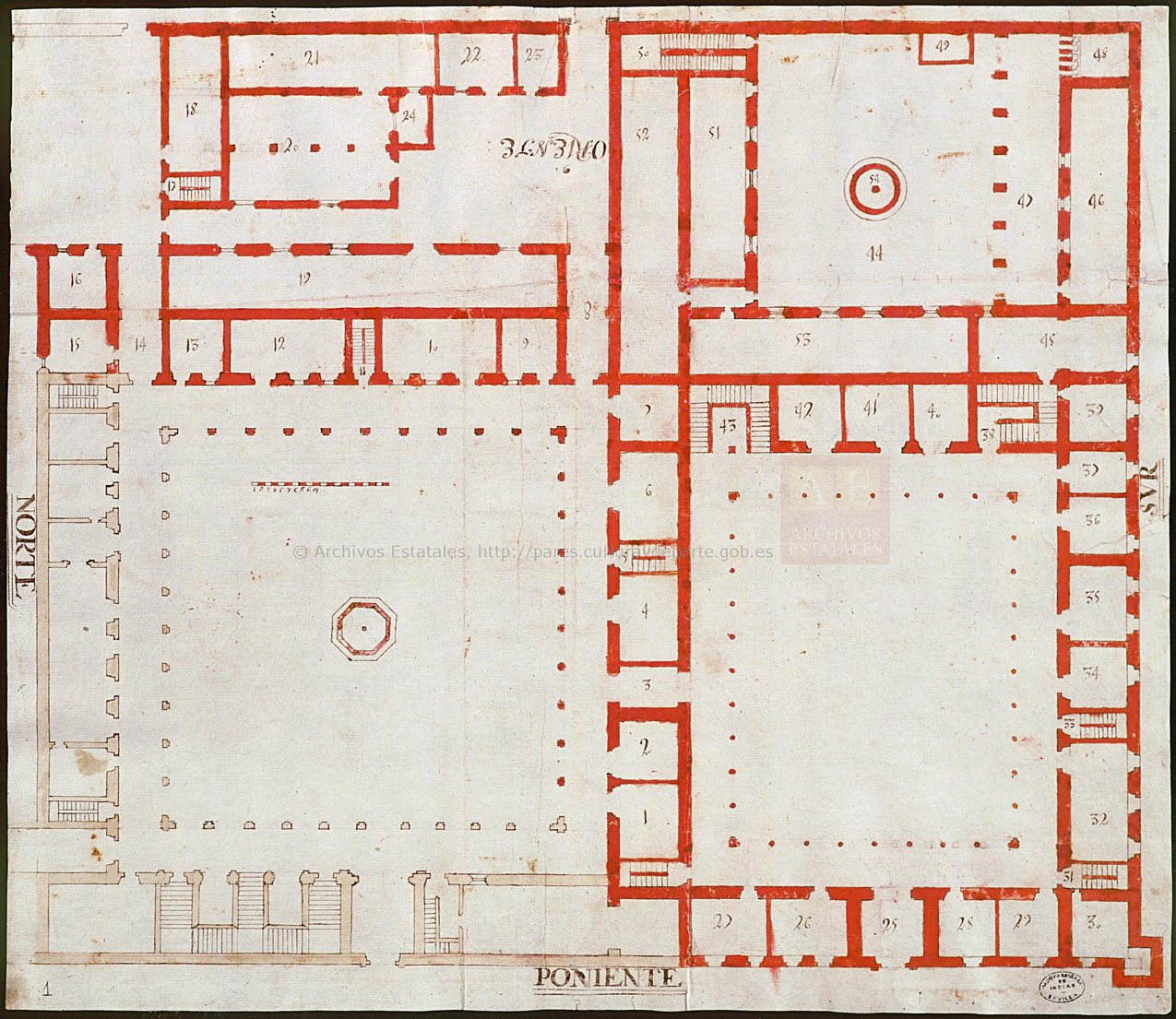

Whether the parties themselves sought an audience or they sent their representatives, when Indigenous legal pilgrims arrived in Mexico City, their encounter with the Juzgado General de Naturales was likely experienced mostly in the lower floor of the palace structure, a bustling, busy, urban space where coaches sometimes randomly parked, a brusque trade in official paper bearing royal or papal seals took place in almacenes lining the lower floor, and where unofficial legal agents stepped over splayed-out drunks and makeshift market stalls to hustle possible petitioners, hawking their literacy in the law by offering to craft their petitions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Plaza-level entrance, with open courtyard with fountain, and stores selling official sealed paper (papel sellado) indicated, in planned reconstruction of the Palace, “Planos…Real Palacio de los Virreyes en la Ciudad de México.” Source: Archivo General de Indias, Mapas y Planos, Méxica, 105, 1709. Used by kind permission of the Archivo General de Indias, Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Spain.

At least this was how it was described in 1784, when the Juzgado's asesor Eusebio Bentura Breña attempted to put an end to the infiltration of informal or vernacular paper petitions into the court. After insisting that the solicitadores keep regular hours and always sport the ruffled collars (golillas) that would distinguish them from rogue writers, he opined that that any Indigenous subject who showed up at the palace with a document written up by an anonymous writer should be questioned about the identity of the author, and the author thrown in jail. This was an impotent move, especially given the fact that royal authorities would rule 3 years later that, both at the Council of Indies in Madrid and in Mexico City, litigants from New Spain had the right to select their own legal representatives. By the time Bentura Breña's book was published, he had to add a footnote acknowledging the royal position on the freedom of litigants to select legal representatives in courts. But he added his own caveat: the Juzgado General de Naturales should remain an exception and native litigants should be restricted to using only the provided legal functionaries (Figure 4).Footnote 26

Figure 4. Second-floor offices and courtrooms in planned reconstruction of the Palace, “Planos…Real Palacio de los Virreyes en la Ciudad de México” Source: Archivo General de Indias, Mapas y Planos, México, 105, 1709. Used by kind permission of the Archivo de Indias, Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Spain.

It still unclear to me whether the Juzgado occupied a permanent, stable physical space inside the palace for any extended period. There are times when sources seem to refer to it as a fixed space, such as when the solicitadores of the Juzgado were directed to set up tables in the corridors “right outside the” tribunal. Famed Baroque intellectual Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora also referenced the Juzgado in his recounting of the riot of 1692 as he traced the spread of a fire as it roared upward and inward in the palace structure, until it reached what seemed to be the vulnerable heart of the palace: the residences of the viceroy, the royal chapel and the “juzgado de indios,” which he located as facing south toward the Plaza del Volador (Figure 5).Footnote 27

Figure 5. Key to 1709 floor plans for the reconstruction of the Palace, with no indication for any dedicated space for the Juzgado de Naturales, “Planos…Real Palacio de los Virreyes en la Ciudad de México.” Source: Archivo General de Indias, Mapas y Planos, México, 105, 1709. Used by kind permission of the Archivo de Indias, Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Spain.

Despite these descriptions, in many of the plans of the palace, there is no specific space designated for the Juzgado itself, even though rooms are designated for an array of different legal affairs and jurisdictions. For example, a key to the 1709 plan shows that the bureaucratic wing of the palace is filled with various offices for the power players of Spanish colonialism and their targets: antechambers for nobles, torture chambers, the sala and scribal office of the Merchants’ Guild, and even offices of the Juzgado for the Property of the Deceased, all of which had a place in the arched halls of the palace. It is possible that the hearings in which the viceroy presided took place in the throned “sala de acuerdo,” a tribunal close to his apartments. But what of the “hearings”—the vast majority in the executive channel—in which the viceroy did not appear? What about the volumes of pages that contain not the varied handwriting, folded papers, and marks of movement over space and time that one might find in a civil case but instead only the uniform script of the escribano who copied complaints and rulings, one after the next, on running pages, filing them away in his wooden cabinet? Until the end of the eighteenth century, these interactions appear to have taken place in no place.Footnote 28

****

Perhaps the disembodiment and dislocation of law that took place as Indigenous petitions ascended to the viceroy means that the Juzgado General de Naturales should be considered not so much in material or physical terms but as part of the realm of colonial political imaginary. The hazy extra-textual life of the Juzgado might not indicate a distance or barrier between the viceroy and Indigenous subject but rather a space for the production of the royal mystique that legitimized colonial rule. Following scholars like Alejandra Osorio, we might conclude that, much like the simulacra of Spanish kings paraded through colonial capital cities, the absences as much as the pageantry of the Juzgado General de Naturales made it not unreal or half-real, but hyper-real.Footnote 29

But blueprints lay a different path for the history of the Juzgado de Naturales after 1692. Many of the palace plans I searched looking for its location were created in a specific context: the palace's reconstruction after the riot left it only half standing. The building plans indicate a desire to better fortify the palace with guard houses and interior turrets, suggesting the response to the riot was for colonial elites to dream of greeting with arms those who entered the palace to conduct legal business (Figure 6).Footnote 30

Figure 6. Planta del Palacio Mayor, 1693. Source: Archivo General de Indias, Mapas y Planos, México, 571. Used by kind permission of the Archivo de Indias, Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Spain.

With this larger trajectory in mind, let us also look again at Villalpando's post-riot painting—the Vista del zócalo de la Cuidad de México, of a place where, as piles of papers grew, the viceroy seemingly receded—now from the vantage point of a court that was increasingly buffered and bureaucratized. In the words of literary scholar Anna More, Villalpando's depiction of the square, like the blueprints for the palace's reconstruction, imagined an “order that could develop in the shadow of the crumbling façade of viceregal governance” after the riot.Footnote 31 Among the idealized elements in this painting is the size and presentation of the main door, a detail especially obvious when it is compared to later drawings (Figure 7).Footnote 32

Figure 7. Close-up focused on palace door, Villalpando, Vista, shown in Figure 1.

Perhaps Villalpando enlarged the door to indicate that, in a post-riot world, the king's colonial subjects still found ample entry to the palace, that there was no blockage to get to the Juzgado and, ultimately, to justice. Along the same lines, perhaps maximizing the door minimized how prominent a role entry to and exclusion from the palace might have figured in the riot itself. On the first day of unrest, a crowd had pushed into the palace courtyard, aiming to climb up the stairs toward the upper floor of the palace, where the tribunals and viceregal residences were located. But they were repelled. The next day, rioters—led by fierce, stone-throwing women—came back to the plaza. According to Sigüenza's account, it was not so much the scuffle in the patio of the palace that marked the turning point of the riot but the “moment the [principal] door was shut.”Footnote 33

In fact, it is worthy of reflection that native petitioners who came for their day in court at the Juzgado General de Naturales generally were not to enter through this main door. Instead, from the time of the Conde de Monterrey on, if they were to have an audience at all, they were to be ushered through a side entrance and up back stairs, known as an escalera escusada. Was this special access to the king's special justice for Indigenous subjects or was this a narrowed channel?

Surely the answer to that question varied among different colonial subjects and changed over time. But in 1692 the answer to a different question can provide us a proxy answer. In the heat of the riot, as the fire tore through the offices of the palace—each tribunal painstakingly enumerated by Sigüenza in his account, each representing a distinct jurisdiction or privilege in colonial law—the flames finally reached a space he called the Juzgado de Indios, engulfing it in smoke. The creole intellectual's chief concern was not the personnel or space of the court but the flammable documents it contained. Paperwork had come to constitute not only the Juzgado's archive but its very essence. Beneath the fire, on the street, an official confronted one rioter and asked what he was doing. His answer: “I swear to Christ those legal bureaucrats who do nothing but push paper and throw people in workhouses must die.”Footnote 34

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Marie Francois, Christoph Rosenmüller, Matthew Mirow, and Gustavo César Machado Cabral, along with the participants in the Semanário Permanente do Núcleo de Estudos Sobre o Direito na América Portuguesa for their generous engagement with this article, and thanks the other forum participants for their camaraderie.