George Gershwin has been both celebrated and reviled as a hybridizer of musics popular and classical. The tale that he was turned down as a pupil by Stravinsky is a case in point. In this frequently reprinted anecdote, the young American met Stravinsky (or Ravel in some tellings) and asked for lessons. The European master replied by asking Gershwin how much money he made and, after Gershwin named an astronomical sum, quipped: “Then I should take lessons from you!” Whether the story is true or not is irrelevant to the argument here. It is the persistence of the tale and its humor that highlight an ideological fault line between Old World and New, classical and popular, artistic accomplishment and economic success.

Scholars have long recognized Gershwin’s concomitant financial success, but the interrelationship of his artistic and economic accomplishments only rarely receive sustained attention. This chapter argues that Gershwin’s economic and artistic fortunes were deeply intertwined. Documents in entertainment trade magazines and the composer’s personal legal/financial records deposited at the Library of Congress reveal that Gershwin brought the economic experience of popular music to the concert hall, applying for-profit strategies from Tin Pan Alley and Broadway to the tradition of classical music. Raised in a musical world defined by hits, Gershwin sought “hits” in the concert hall as well. He was as ambitious in his artistic dreams as he was in his quest for financial reward.

Gershwin’s pursuit of profit was in harmony with his pursuit of compositional craft, musical innovation, and emotional expression. For Gershwin, writing original music that delivered a message, whether as a freestanding song, as part of a Broadway spectacle, or as a piece of concert music, was what led to hits that would be successful both musically and financially. Gershwin’s strategies for wealth, fame, and artistic achievement were all part of the same ambition to write great music that would reach large audiences. He saw musical excellence as a market opportunity; melody propelled by original, sophisticated music would triumph as art and product. He would write great music, and great music would sell.

Gershwin’s An American in Paris offers a signal example. This orchestral tone poem was not commissioned, but a project of Gershwin’s own. He received no fee to compose it, yet the resulting high-profile premiere in December 1928 established the reputation of Gershwin’s first work for orchestra alone. The composer then leveraged this success not only for subsequent concert performances, but also for a series of radio, recording, publishing, and stage projects that within one year reached larger audiences and returned significantly more financial reward than would be realized even today through a traditional orchestral commission. While An American in Paris continues to thrive as a concert hall staple (not only in pops programming but now also as a subscription concert feature that sells tickets), during its first year of existence it was heard more often outside the concert hall than within it. Gershwin’s approach to An American in Paris is as indebted to the patterns established by his first Tin Pan Alley hit “Swanee” as his experience with Concerto in F.

Gershwin’s creative and business practices are best described as a symbiosis. His success in popular music, as well as Rhapsody in Blue, subsidized the creation of An American in Paris, allowing him to compose without a commission or promise of performance. The payoff came later, when radio, recording, and Broadway performances carried the music to an increasingly broad audience, propelling its success both financially and critically. Such additional revenue streams led to financial freedoms that furthered Gershwin’s focus on creating music and his increasing independence in terms of how he composed, what he composed and for whom. Economic stability enabled artistic risk taking. Gershwin’s artistic achievements thus were often nurtured and amplified by commercial success. In turn, such success provided a financial base to support further artistic exploration. Money and music were harmonized.

George Gershwin’s first published song was the 1916 title “When You Want ’Em, You Can’t Get ’Em, When You’ve Got ’Em, You Don’t Want ’Em,” with lyrics by Murray Roth. Although in 1914 Gershwin dropped out of school to work for Remick & Co. for a weekly salary of $15 as a staff pianist (also known as a “song plugger”), the firm at first refused to publish his songs.1 On the recommendation of Sophie Tucker, Gershwin’s first title was published by the rival house of Harry Von Tilzer. Together Roth and Gershwin were paid $1 for the song with the promise of a half cent royalty on every printed copy sold in the United States and Canada, plus 25 percent of any recording fees received by the publisher.2 Gershwin reportedly made a grand total of only five dollars on the song.3 But sheet music sales were not his only source of income from this tune. In September of the same year, Gershwin recorded a piano roll of “When You Want ’Em“ as a “fox trot” instrumental for Universal.4 Thus, from even this first song publication, Gershwin leveraged connections with a star performer to create opportunity and then used multiple product streams to increase the economic reach of a single creative work.

After leaving Remick on March 17, 1917, Gershwin worked as an accompanist, landing a job for the Broadway show Miss 1917, produced by Charles Dillingham and Florenz Ziegfeld and directed by Ned Wayburn.5 The music was by Jerome Kern, a composer and partner in the Harms publishing firm. Gershwin described the resulting career breakthrough in an interview with The Billboard magazine in 1920:

After I got to know the music of the show, I started to put little frills and furbelows into it. This made a hit with the chorus girls and Ned Wayburn found they worked better when I played for them. Jerome Kern had written the music for the show and both he and Harry Askins, the manager, took an interest in me. I had written a song called “The Making of a Girl,” which was in The Passing Show of 1917 and made quite a hit. On the strength of this, Mr. Askins offered to introduce me to Max Dreyfus, the head of T.B. Harms and Francis, Day & Hunter, the publishers.

I accepted gladly and the following day we went to see Mr. Dreyfus. He asked me to play for him and I played four of my songs. When I finished, he said “Come and see me next Monday.” At this I laughed inwardly, for it had a familiar sound by that time [of polite refusal]. It so happened that I had been engaged to play the piano for Louise Dresser’s vaudeville act and I didn’t consider Mr. Dreyfus’ invitation to call again very seriously. You can judge of my surprise then, when on going to see him the next Monday, he said, “Gershwin, I believe you’ve got the stuff in you. I’m willing to back my judgment by putting you on the salary list. You may make good the first year, but if you don’t, you will in the second or third or fourth or perhaps the fifth. Go to it.”6

Gershwin signed with Dreyfus on February 21, 1918.7 His was a remarkable contract for a young songwriter with more promise than hits to his credit.

Founded in 1881 as the Thomas B. Harms Music Publishing Company and known as Harms, Inc. from 1921, the house would remain Gershwin’s publisher under one imprint or another throughout his creative life, publishing both his songs and his concert music. Dreyfus had purchased the firm in 1904 from Thomas Harms, gradually turning it into the most prestigious publisher of New York’s Tin Pan Alley. By 1918 when Gershwin signed, it was known as T. B. Harms, Francis, Day, & Hunter and was fast becoming a Broadway powerhouse. Dreyfus discovered and promoted Jerome Kern, Vincent Youmans, Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein, Kurt Weill, Alan Jay Lerner, and Cole Porter as well as Gershwin.8 In 1920 Harms, Inc. was named as one of the defendants to a US Justice Department lawsuit under the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act. Together the seven defendants allegedly controlled some 80 percent of the US music publishing business.9 In time, Harms would combine with the English firm of Chappell, Inc. to publish some 90 percent of Broadway’s songs.10

Gershwin’s contract with Harms granted the publisher exclusive and comprehensive ownership of Gershwin’s music and the “sole, exclusive, absolute and unlimited right, license, privilege and authority to publish, copyright, re-copyright, print, reprint, copy and vend, throughout the civilized world, all the music and all the ensembles, concerted numbers, solo numbers and all other numbers composed and written” by the composer.11 Any lyricist collaborating with Gershwin would be bound by the same stipulation, and the company retained the right to change title or lyrics to any work. Harms negotiated agreements with his lyricists separately, but they were required to sign, or they could not work with Gershwin.

The composer was at liberty to compose for any Broadway production company, as long as the music would be published exclusively by Harms. Gershwin could not publish with anyone else, even as a collaborator, nor allow his name to be used by another publisher. There was only one exception – three works already under contract to Remick: “There’s More to a Kiss,” “Loving Makes Living So Sweet,” and “A Corner of Heaven with You.”

In exchange Gershwin received the promise that Harms would publish any and all of the works created by the composer. If the company chose not to publish a work within a year, ownership of that work would revert to its author. Gershwin received an initial royalty of three cents per copy for each piece of sheet music sold (publicity and professional copies exempted). And he was given a weekly salary of $35, payable on Saturday, for the rights to whatever he might compose. In 2018 dollars, this salary would have amounted to approximately $30,000 a year. The contract includes no requirement that any composition be delivered, but Gershwin negotiated a handwritten addition to the contract – he would receive an additional advance of $15 each week against future royalties. The composer thus increased his living allowance, but incurred a debt to the company that would necessitate publication success to offset. The advance can be seen as a sign of his confidence and determination. It also allowed and required a greater focus on composition; by signing, Gershwin committed to being a full-time songwriter. Any other income earned by the company off of Gershwin’s music, say in licensing the music for foreign publication or for a recording or for use in a stage show, would net Gershwin 25 percent of the publisher’s receipts. The parties paid each other $1 to seal the deal.12

Dreyfus’s offer represented an investment in Gershwin’s all-but-unproven talent and economic potential. It also amplified and propelled this potential. With the Harms’ marketing machine leveraging Gershwin’s music, both composer and company sought to benefit. An important clause in the contract at once flattered and disciplined the composer:

It is further agreed upon between the parties hereto that the said Composer is well, favorably and extensively known as one of the leading composers of music, and that his services as such are peculiar, exceptional, unique and extraordinary, and that his compositions have been uniformly distinctive; that his compositions cannot be duplicated, and that in the event of a breach of this agreement by the said Composer, the Company will sustain irreparable damage and inestimable loss, due to the fact, among other things, that immediately upon the execution of this contract the Company will incur considerable expense in advertising and popularizing the compositions of the said Composer, and it is agreed that in the event of any such breach upon the part of said Composer, the Company shall thereafter be wholly and absolutely released from any and every obligation hereunder.13

If Gershwin were to renege on the deal, he would lose everything. Everything included the rights in perpetuity to all of the music published under the terms of the deal. The compositions would become the sole property of the publisher. In addition, the company would no longer need to pay any royalty due on this music now or in the future.

The terms and conditions applied indefinitely to Gershwin’s musical works “in full force and effect forever.” The contract would be valid for just a year, but Harms had the option to renew on the same terms for an additional year at its own discretion. Such a renewal would presumably include a similar one-year renewal clause, so Gershwin was, in effect, signed for life.

In 1945, eight years after Gershwin’s death, his music industry friends created the reverential biopic film Rhapsody in Blue.14 While Robert Alda appeared as Gershwin, many of the industry figures who played a role in the composer’s success appeared in cameos as themselves, and maybe not surprisingly with a bit of self-aggrandizement as to their personal impact on Gershwin’s career. Oscar Levant and Al Jolson appeared as themselves. Both figure prominently in the scenes addressing Gershwin’s initial song hit, “Swanee” (1919), a major episode in both the composer’s life and the biopic. About twenty minutes into the film, Levant encounters Gershwin in the waiting room of Harms, Inc., where the young George is hoping to meet Dreyfus for the first time and introduce him to his music. Levant looks over the song Gershwin has brought to pitch to the publisher and remarks wryly: “Hmm, diminished ninth; if I had your talent, I’d be a pretty obnoxious fella.” Dreyfus (played by Charles Coburn) soon meets privately with Gershwin. Reviewing the manuscript to “Swanee,” Dreyfus similarly identifies a “diminished ninth” chord and remarks that it is “unusual for popular music.” The filmic George points out that in popular music “we gotta have something different.” Certainly, a diminished ninth chord would be innovative and a signal of the influence of jazz, but it is not precisely clear what this non-standard musical term might indicate in the script. It could be a joke, a reference to jazz-sounding chord extensions, or literal description.

The film then compresses two events into one: Dreyfus’s negotiation of Gershwin’s Harms contract and the introduction of Gershwin’s soon-to-be hit to star Al Jolson, who would make “Swanee” famous in his musical revue Sinbad. In the film, Dreyfus immediately offers Gershwin a two-year contract at $30 a week. When Gershwin expresses surprise, Dreyfus raises his salary to $35. The incredulous composer remarks: “You mean you’d pay me to write my own songs.” Dreyfus quickly realizes his error, smiling as he recognizes Gershwin’s noble naiveté. Next, George sits at the piano and plays an ornamented accompaniment to “Swanee.” Without another word, Dreyfus walks to his desk and phones the Winter Garden Theatre, where Sinbad is running. Jolson answers backstage and hears Gershwin playing in the background. He asks: “Who’s that guy plunkin’ the piano?” Dreyfus replies “Gershwin,” and Jolson responds: “Gershwin! Never heard of him.” Yet after listening a bit more, Jolson remarks “Say, that ain’t a bad ditty” and wants to know “Who wrote it?” After being introduced to the composer, Jolson remarks to Dreyfus: “Max, look, send that song over to me, and I guarantee I’ll make ’em beat a path to it a mile long.”

While exaggerating Gershwin’s passive role in this business opportunity and thus amplifying the role of Dreyfus and Jolson in launching the young composer’s career, the scene communicates two ideas. First, that George was either too pure of musical heart or simply too naïve to be aware of the art’s business side. Second, it depicts Dreyfus as Gershwin’s career mastermind, immediately making a connection to Jolson that would guarantee the composer’s success. Neither of these claims ring precisely true to history.

In reality, Gershwin had worked his way up from song plugger to vaudeville accompanist to Broadway rehearsal pianist with grit, determination, and savvy, all the while writing songs and gaining musical skills, artistic insights, and a network of professional connections. Gershwin first met Jolson at the Atlantic City tryouts for his show La-La-Lucille! in April of 1919, likely through the show’s lyricist Buddy DeSylva, a Gershwin collaborator and Jolson friend.15 DeSylva, in fact, co-wrote one of the songs originally featured in Sinbad, “I’ll Tell the World,” as well as two song hits later interpolated into the revue: “I’ll Say She Does” and “Chloe,” both co-authored with Jolson.16 It was some eight months later, in December 1918, with Jolson no doubt searching for new songs to add to Sinbad, that Gershwin – not Dreyfus – pitched “Swanee.” In the company of DeSylva and “Swanee” lyricist Irving Caesar, Gershwin performed the song for Jolson. Dreyfus was not present, although the fact that the composer had signed with Harms the previous year would have been both a significant professional endorsement and a signal to Jolson that pushing the young composer’s song offered an economic opportunity for him as well.

Jolson soon incorporated “Swanee” into his ongoing revue Sinbad during a December 22 to January 3 run at the Crescent Theatre in Brooklyn. The song was featured subsequently in the show’s run at Poli’s Theater in Washington, DC beginning on January 11.17 A review in The Washington Post described “Swanee” as “the biggest hit of last evening.”18 Sheet music for the song sold concurrently for 35 cents a copy at a local store.19 Dreyfus certainly shares credit for the song’s success, rushing a new sheet music edition into stores. Jolson’s portrait nearly fills the cover page of this Harm’s imprint, leveraging the singer’s celebrity to sell the song. Using the endorsement of a star performer to spur sales was a time-tested technique, and given Jolson’s unparalleled celebrity and popularity as an entertainer and recording artist at this time, the singer’s bold “guarantee” as voiced in the 1945 film was a realistic boast. Likely more influential than Jolson’s stage performance, however, was the recording he made for Columbia on January 8, 1920, immediately after its original New York run in Sinbad.20 The recording featured the singer’s characteristic birdsong whistling and helped sell the sheet music. Again, Harms marketing machine capitalized.

When Jolson’s recording was released around February 20, Harms placed a two-page advertisement in the music industry magazine Variety, touting “Swanee” as a “sensational song success.”21 By April, Columbia Records was placing illustrated advertisements coast to coast.22 These make no mention of Gershwin, who did not yet have a national following, and who was not a Columbia artist. Nonetheless, the composer benefited. Jolson’s recording sold an estimated two million copies, twice that of the music, and in doing so secured Gershwin’s first triumph. In May, Jolson’s recording hit number one on the Billboard chart. It remained on the charts for eighteen weeks, holding the top position for nine. Gershwin himself released two recordings of “Swanee” seemingly timed to take advantage of the Jolson boost. The first was a solo piano roll recorded in February 1920.23 For the second, released the next month, Gershwin performed as pianist with banjoist Fred Van Eps and his quartet.24

It is important to note that while the success of “Swanee” was certainly propelled by Jolson, it did not begin with Jolson. “Swanee” was originally featured as the music for a production number in the Demi-Tasse Revue – a twelve-scene spectacle created by Ziegfeld Follies choreographer Ned Wayburn for the October 1919 grand opening of New York’s luxurious Capitol Theatre at Broadway and 51st Street.25 With 5,300 seats, the Capitol was touted as “the largest theater in the world” and targeted an upscale, but necessarily broad, popular audience. Although located in the theater district, the Capitol was first and foremost a “silent” movie house whose musicians provided accompaniment to the film. The Demi-Tasse Revue stage show was performed twice daily to entertain an audience anticipating the rotating cinema feature.26

Gershwin contributed two songs to the revue: “Swanee” as well as the final production number, “Come to the Moon.” “Swanee” appeared in Scene V as one of two “Shadowland” dance numbers. While the up-tempo syncopation of “Swanee” spoke to post-war optimism, the lyric’s nostalgic references to the antebellum South inspired the costuming. Its eight dancers are listed as four “Old Fashioned Belles” and four “Old Fashioned Beaux.”27

To make money on music in Tin Pan Alley in 1919 was to sell sheet music. The first edition of “Swanee” was published by Harms for the Capitol Theatre show, and it appeared months before Jolson had even heard the song. Printed in two colors (black and olive green), the sheet music’s cover features a line drawing of a dapper couple, the man wearing a top hat and the woman wearing a white hat, reflecting both the pairs of dancers in the revue, and no doubt aimed at couples attending the show who might want a souvenir from their romantic evening. With economic efficiency, this identical design was used – the title and lyricist’s name changed – for “Come to the Moon.”

The Demi-Tasse Revue continued through November and December 1919, and Gershwin’s song gained prominence. The November 15 issue of The Billboard touted “Swanee” as a hit and its future success is predicted: “The big song hit of the Ned Wayburn Revue at the Capitol Theater is ‘Swanee.’ This is a new number by George Gershwin, the composer of ‘La La Lucille.’ I. Caeser [sic.] is responsible for the lyric ‘Swanee’ is sung in the revue by Muriel De Forrest and has scored strongly at all performances. It is a different sort of a Southern song and will probably be classed among the hits of the day ere long.”28

The December 27 issue of the same trade journal notes that “Swanee” has been moved to the top of the show as the “first number” and “should be a big hit for dances.”29 Received wisdom in the Gershwin literature explains the triumph of “Swanee” as a result of Jolson’s star power. Certainly, Jolson propelled the music to nationwide fame and made this first hit the biggest seller of Gershwin’s career, but it was the Capitol Theatre Revue that first launched “Swanee” toward success. Jolson thus adopted a regional hit, transforming it into a national one. That Jolson came to play this role, however, may have been part of the songwriters’ creative inspiration, if not a savvy and bold business plan.

The tale of Gershwin’s “Swanee” typically depicts the writing of the tune as a bit of good fortune. Caesar claimed it was written in about fifteen minutes, while Gershwin gave it “about an hour.”30 Apparently the pair began composing the song on a bus ride to the Gershwin family apartment, having just visited the Harms offices. The rapid timeline of its creation mythologizes Gershwin’s genius but fails to recognize how the song’s themes and style may have been intentionally calculated to meet the needs of popular success. Tin Pan Alley cared about hits and little else. As aspiring songwriters, Gershwin and Caesar would undoubtedly have had the same goal, and their publisher would no doubt have offered advice on what and how to write.

“Swanee” is a parody of songwriter Stephen Foster’s pre-Civil War tune “Old Folks at Home.” A parlor minstrel tune in dialect, Foster’s song opens with the line: “Way down upon the Swanee Ribber,” thus giving Gershwin’s “Swanee” its name. “The word [“Swanee”] fascinated me,” Gershwin later explained.31 Gershwin’s music as well as Caesar’s words – particularly the concluding reference to the “old folks at home” – make the connection to Foster’s song immediate and clear. Likewise, Gershwin’s melody for the chorus paraphrases Foster’s opening melody.32 In “Swanee,” minstrelsy, nostalgia, exoticism, and ragtime are wrapped into one, lyrically and musically.

Although written in 1851, Foster’s song was alive and well in Gershwin’s sound world more than six decades later. It had been reborn in the midst of World War I through the community singing movement as an expression of homesickness and patriotic nostalgia. Jolson himself had struck this vein of gold with his 1916 hit recording of “Down Where the Swanee River Flows,” written by Charles S. Alberts and Charles K. McCarron with music by Albert Von Tilzer. It reached number three on the Billboard chart in August.33 Its lyrical themes – love and longing for “home,” “Dixieland,” “the Swanee River,” “the banjo,” “my dear old mother,” and singing birds – all prefigure Caesar’s lyric three years later. Yet another Swanee song triumphed just the month before Gershwin’s own premiered, Harry Hamilton’s “My Swanee Home.” This sentimental ballad, which likewise made both melodic and lyrical reference to Foster’s original, peaked at number five on October 18.34 Thus Gershwin’s fascination with the word may well have been genuine, but it was seeded by fashion and economic opportunity. A standard Tin Pan Alley songwriting strategy was to mimic the themes and styles of a current hit to create a new one.

Gershwin’s “Swanee” seems all but calculated to the commercial needs of Tin Pan Alley generally and a Jolson hit song in particular. The blackface performer specialized in mammy songs and up-tempo ragtime numbers. “Swanee” met both needs with its syncopated rhythms and references to the Deep South, “Dixie,” and the singer’s “Mammy, waiting for me.” Jolson’s show Sinbad traded upon a fascination with exotica, specifically the Arabian nights, so Gershwin’s use of an exotic sonic model, the 1918 hit “Hindustan” by composer Harold Weeks, made a song about the past, stylistically current.35 Further, a long-running show such as Sinbad demanded new material. Revues had to be updated with new songs to keep audiences coming back for more. This continual revitalization of repertoire provided economic opportunities to launch a sequence of hit songs, sell sheet music, and sell recordings.

Gershwin’s “Swanee” seems almost custom built for Jolson’s revue. In this regard, it is possible that the 1945 Rhapsody in Blue biopic may hint at the truth. If Caesar and Gershwin wrote “Swanee” on the way home after a meeting at Harms, maybe Dreyfus or another Harms’s employee had suggested that the pair create a song for Jolson. In any event, the extraordinary success of the Sinbad/“Swanee” combination inspired future efforts of undeniable economic calculation. Gershwin, with both DeSylva and Caesar, continued to write songs for Jolson’s show, including “Tomalé (I’m Hot for You)” and “Swanee Rose” (also known as “Dixie Rose”).36 The latter was a direct attempt at a follow-up hit. As a Harms advertising notice put it, “Swanee Rose” “looks like another ‘Swanee.’”37

Yet Gershwin’s “Swanee” was much more than a vapid commercial product. In an interview for Edison Musical Magazine, Gershwin expressed pride in the economic and artistic synthesis of the song:

I am happy to be told that the romance of that land [the South] is felt in it [“Swanee”], and that at the same time the spirit and energy of our United States is present. We are not all business or all romance, but a combination of the two, and really American music should represent these two characteristics which I tried to unite in “Swanee” and make represent the soul of this country.38

Gershwin’s artistic ambition is embedded in the harmonies of “Swanee.” His “diminished ninth” (in the form of the song’s unusual augmented chords in the insistent chorus) broke the mold of the typical Tin Pan Alley song structure. Gershwin did, in fact, do something “different” musically with “Swanee” to make it stand out from its competitors as something special. For Gershwin, artistic innovation was a feature of value, a feature that would appeal to the public and help create a hit.

In many ways, Gershwin’s alloy of romance and drive, passion and profit, inaugurates the Roaring Twenties, a time when the ragged rhythms of African American culture catalyzed the peace-time prosperity of the industrial age in the United States. Gershwin’s art seems to resolve at once the tension between Old World and New, between the ambition for artistic expression and the drive for business success. Passion and profit seem, if not harmonized, then at least placed in a constructive partnership that brings the Ziegfeld Theatre and Carnegie Hall – Tin Pan Alley song and orchestral composition – into conversation.

In early 1925, conductor Walter Damrosch of the New York Symphony Society asked the society’s president, Harry Harkness Flagler, to commission a piano concerto from George Gershwin. Flagler phoned Gershwin with the proposal. “This showed great confidence on his [Damrosch’s] part,” Gershwin noted, “as I had never written anything for symphony before.”39 Gershwin stopped by the symphony offices in Steinway Hall on April 17, 1925 to sign the contract with manager George Engles. The composer agreed to deliver score and parts to a work for piano and orchestra, tentatively titled “New York Concerto,” a week before rehearsals for a premiere on December 3. The contract anticipated seven performances: two in New York, for which Gershwin would receive $500; and five additional performances compensated at a rate of $300 each. The December 3 date at Carnegie Hall was specified to be “the first performance of the work in New York.”40 Gershwin was thus set to earn $2,000 total.41 That the fee was tied to performances – which were likely to be highly anticipated and sold out – adroitly served the needs of the Symphony Society, which was in significant financial trouble.42 Gershwin only performed Concerto in F with the society six times, and he seems to have received no advance financial support or fee for composing the piece.

Certainly, the motivations of both composer and commissioner were more than financial. A composer himself, Damrosch was a regular supporter of contemporary music. He gave the American premiere of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony and performed new works by Elgar, Debussy, Strauss, Stravinsky, and Milhaud. He supported American composers as well, conducting music by John Alden Carpenter, George Chadwick, Aaron Copland, Charles Martin Loeffler, Daniel Gregory Mason, and Deems Taylor, as well as Gershwin. Damrosch not only knew Gershwin through the composer’s friendship with his daughter Alice, but he had also attended both a rehearsal and the 1924 premiere of Rhapsody in Blue. Talking about the composer in the press, Damrosch echoed Paul Whiteman’s rhetoric that Gershwin’s classical efforts made jazz respectable as art. According to Damrosch, Gershwin was a musical “prince who has taken Cinderella by the hand and openly proclaimed her a princess to the astonished world.”43

For Gershwin the concerto was a claim to artistic respectability. He sought to prove that the 1924 success of Rhapsody was not a fluke. “Many persons had thought that the Rhapsody was only a happy accident. Well, I went out, for one thing, to show them that there was plenty more where that had come from. I made up my mind to do a piece of absolute music. That Rhapsody, as its title implied, was a blues impression. The Concerto would be unrelated to any program.”44 That Gershwin changed the title from New York Concerto to the more prosaic, standardized classical moniker, Concerto in F, signaled his attempt to cleave to the traditions of absolute music. Three years later, his orchestral tone poem would embrace these same ideals of symphonic concert music to please the critics, but with the addition of a narrative program to please the public.

An American in Paris was premiered by the same conductor and ensemble, and represents another step in Gershwin’s quest to earn both a living and critical respect. Gershwin’s interest in composing the tone poem seems to have been ignited not by a call from an orchestra manager, but by a one-week visit to the European cultural capital in 1926. He had visited with friends Mabel and Bob Schirmer in Paris during a break from the London launch of his hit musical Lady, Be Good! An inscribed photograph dated April 11 thanking the Schirmers for their hospitality includes notation for two musical themes: the opening “Andantino” from Rhapsody in Blue and a new melodic motif labeled “Very Parisienne” and prophetically titled “An American in Paris.” The four-bar fragment would find its way into Gershwin’s “Orchestral Tone Poem” two years later as its opening “walking theme.”

Gershwin started composing An American in Paris in January of 1928. Unlike Concerto in F or Rhapsody in Blue, he wrote without the promise of performance. He had no particular deadline in mind, yet continued work on the score from March to June, during a three-month tour of England, France, Austria, and Germany, and completed a draft on August 1 back in New York. Described variously in the press as a “symphony,” a “ballet for symphony orchestra” and a “jazz symphony,” the ultimate title of the work had been announced even before Gershwin had set sail for London.45 A May 29 Parisian premiere at an all-Gershwin concert had been contemplated if Gershwin could finish the score in time.46 Instead, it appears that a meeting between Gershwin and Damrosch in Europe led to the plan for a Carnegie Hall debut.47 On June 5, the New York Philharmonic-Symphony (the now combined forces of the New York Symphony and New York Philharmonic Society), announced it would perform Gershwin’s “orchestral rhapsody” that fall.48 When Gershwin got word on November 5 that Damrosch would lead the premiere in December, he retreated to Bydale, the Connecticut home of Kay Swift and James Warburg, where he sequestered himself in a private cottage to work. A little more than two weeks later, on November 22, Gershwin was pictured in the New York Sun, sitting next to the conductor at the piano, the pair reportedly reviewing the new score.49

It is perhaps an indication of his characteristic confidence that Gershwin composed An American in Paris without a commission. Yet the score also contains a shadow of the composer’s professional anxiety. The cover page proudly proclaims that its contents were “Composed and Orchestrated by George Gershwin.” Such a declaration suggests that the work was meant as an answer to critics who had branded him an incapable orchestrator. Each page of sketch, draft, and full score are written entirely in the composer’s own hand. Gershwin was proud of this work, and, not coincidentally, it seems intended as a kind of artistic manifesto, simultaneously accessible to a broad swath of listeners due to its sonic narrative while also demonstrating polished compositional skills, especially in the integrated development of its themes. The melodies and mottos of An American in Paris are derived primarily from the original “Very Parisienne” theme inscribed to the Schirmers. Each theme in the work’s A section (bars 1–383) is developed from this single two-eighths and quarter-note motif and presents a remarkable example of motivic cohesion. An American in Paris is thus a proclamation of compositional authority on a symphonic scale.

Gershwin was certainly paid for the New York premiere of An American in Paris. He received a rental fee for the “orchestration” of $25 and an additional $25 for each performance. In December 1928, the orchestra performed the work four times: the December 13 premiere plus performances on December 14, 21, and 22. There appears to have been no extra fee assessed for the rights to the world premiere. A Philharmonic receipt reports a payment of $125 to “New World Music Corp.,” a Harms subsidiary that handled only the Gershwin catalog.50 Considering that Gershwin spent approximately six months on the composition, this fee is far from a just wage and is far below the sum he might earn in the popular music realm. However, Gershwin was financially successful enough to afford a three-month European tour. He could effectively subsidize his own time through previous earnings. Further, he was about to earn significantly more money from his new orchestral work by licensing it to popular outlets outside the concert hall.

Gershwin’s largest single payday for An American in Paris came in January 1929 when he sold the rights for its radio broadcast premiere to the Godfrey Wetterlow Company representing the W.S. Quinby Company.51 Quinby was a tea and coffee importer, roaster, and wholesaler located in Boston and Chicago.52 Like many companies in the first decades of radio, it sponsored a radio show to reach customers across a wide geography. In Quinby’s case, this show was the La Touraine Coffee Concerts on NBC, which was broadcast through WCAE in Pittsburgh. Gershwin’s radio contract was pathbreaking. According to the Pittsburgh Press, the agreement marked “the first time in the history of radio that sponsors of commercial features have contracted for the rights to the first performances of such a work.” The composer and Deems Taylor seem to have helped narrate the show on January 30, 1929 beginning at 7:30 p.m. Nathaniel Shilkret conducted the La Touraine Orchestra. The program also included “excerpts from the famous Gershwin ‘Rhapsody in Blue,’ and a medley of his musical comedy, revue and dance hits.”53

Gershwin was paid the astonishing fee of $5,000 for this broadcast premiere, a fee not much different from what an A-list composer might receive for an orchestral commission today.54 Adjusted for inflation, $5,000 in 1929 is roughly equivalent to $73,000 in 2018 and would thus equate to around $4,000 per minute for the 18-minute musical work.

The radio premiere secured, Gershwin then released a recording. Victor Recording Company logs report that conductor Nathaniel Shilkret, fifty-three instrumentalists, and Gershwin himself gathered in New York City’s Liederkranz Hall on February 4, 1929 to record An American in Paris. According to Shilkret’s autobiography, the composer had asked him personally to conduct the recording. Gershwin himself played celeste, and Shilkret reported that the composer was so deeply invested in offering suggestions to the orchestra, that he had to request that Gershwin leave the soundstage for an hour so that the musicians could rehearse uninterrupted.55 The resulting two-disc 78 rpm set was nominally part of Victor’s May 1929 releases, but newspaper reviews and store advertisements appear as early as April 19, less than three months after the recording session. Each premium 12 inch disc sold for $1.25.56 Four years later, a second “recording” was released. In June 1933, master piano-roll maker Frank Milne arranged An American in Paris for player piano. It was published by the Aeolian American Corporation on both the Duo-Art and the Ampico series.57 “Milne and Leith” are credited as pianists to give the impression of a full four-hands arrangement, but Milne made the rolls alone, using the added pseudonym “Ernest Leith.” The rolls were coded with unusual dynamic detail and required a reproducing piano in excellent condition. Such rolls were considered of special artistic value.

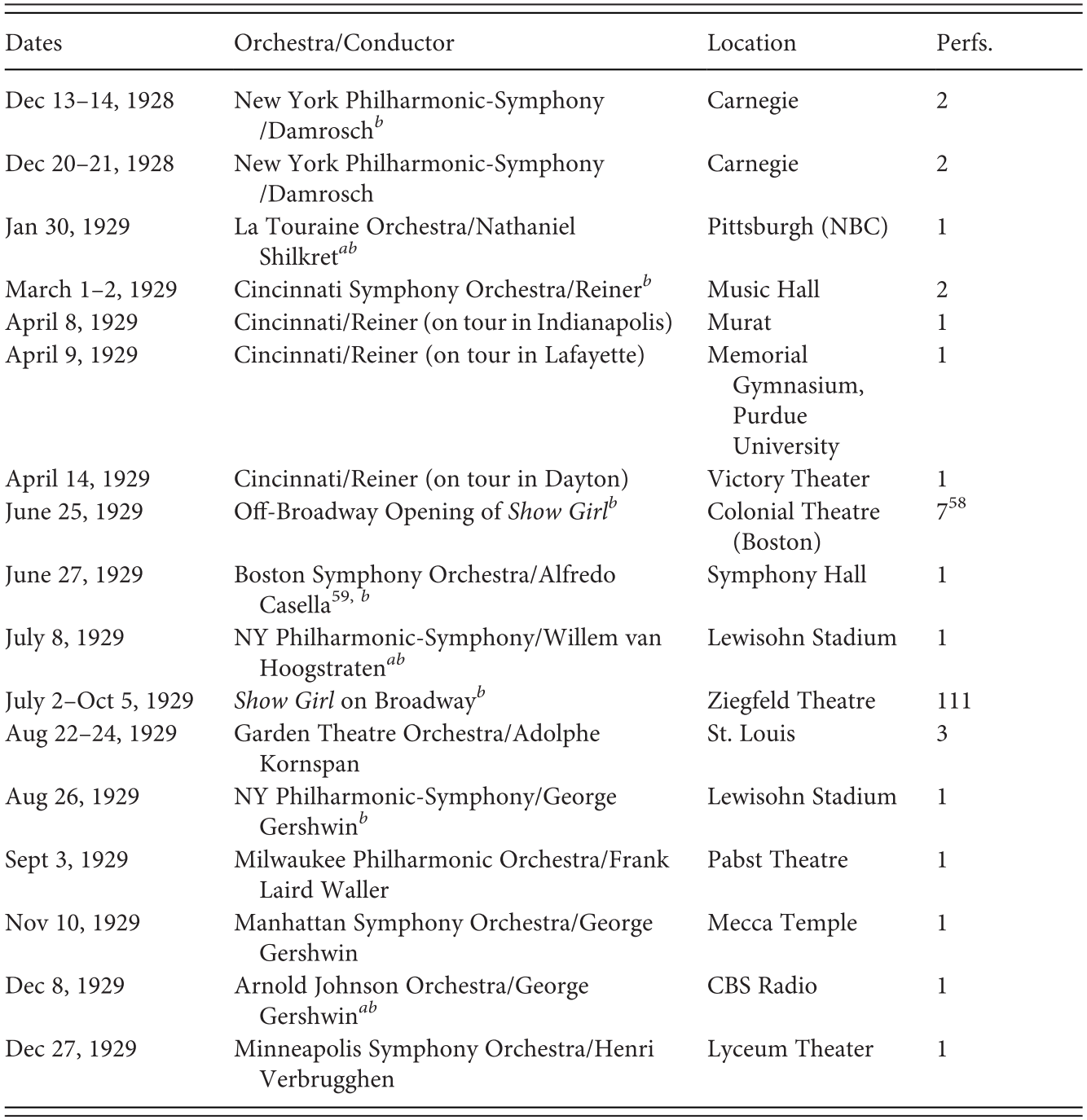

A review of the performance history of An American in Paris tells a story of artistic success and financial innovation (see Table 8.1). In the first year after its premiere, An American in Paris was performed in some twenty instrumental concerts – a remarkable level of interest in a new work, then as now. The New York Philharmonic-Symphony performed the work six times, while the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Fritz Reiner undertook five renditions. Other performances were done by the Boston, Milwaukee, Manhattan, and Minneapolis symphonies, while a St. Louis theater orchestra presented the work three times. Three other performances were broadcast via radio, including a coast-to-coast performance for CBS.

Table 8.1 Performances of An American in Paris 1928–1929

| Dates | Orchestra/Conductor | Location | Perfs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dec 13–14, 1928 | New York Philharmonic-Symphony/Damroschb | Carnegie | 2 |

| Dec 20–21, 1928 | New York Philharmonic-Symphony/Damrosch | Carnegie | 2 |

| Jan 30, 1929 | La Touraine Orchestra/Nathaniel Shilkretab | Pittsburgh (NBC) | 1 |

| March 1–2, 1929 | Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra/Reinerb | Music Hall | 2 |

| April 8, 1929 | Cincinnati/Reiner (on tour in Indianapolis) | Murat | 1 |

| April 9, 1929 | Cincinnati/Reiner (on tour in Lafayette) | Memorial Gymnasium, Purdue University | 1 |

| April 14, 1929 | Cincinnati/Reiner (on tour in Dayton) | Victory Theater | 1 |

| June 25, 1929 | Off-Broadway Opening of Show Girlb | Colonial Theatre (Boston) | 758 |

| June 27, 1929 | Boston Symphony Orchestra/Alfredo Casella59, b | Symphony Hall | 1 |

| July 8, 1929 | NY Philharmonic-Symphony/Willem van Hoogstratenab | Lewisohn Stadium | 1 |

| July 2–Oct 5, 1929 | Show Girl on Broadwayb | Ziegfeld Theatre | 111 |

| Aug 22–24, 1929 | Garden Theatre Orchestra/Adolphe Kornspan | St. Louis | 3 |

| Aug 26, 1929 | NY Philharmonic-Symphony/George Gershwinb | Lewisohn Stadium | 1 |

| Sept 3, 1929 | Milwaukee Philharmonic Orchestra/Frank Laird Waller | Pabst Theatre | 1 |

| Nov 10, 1929 | Manhattan Symphony Orchestra/George Gershwin | Mecca Temple | 1 |

| Dec 8, 1929 | Arnold Johnson Orchestra/George Gershwinab | CBS Radio | 1 |

| Dec 27, 1929 | Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra/Henri Verbrugghen | Lyceum Theater | 1 |

a radio broadcast;

b Gershwin attended at least one performance

Gershwin was present for most of these performances. His participation would have facilitated the delivery of the four pitched taxi horns that he had composed into the work. Initially, Gershwin’s participation typically involved attending a performance and acknowledging the enthusiastic appreciation of the audience, but for the Lewisohn Stadium concert on August 26 Gershwin appeared in the triple role as composer, soloist, and conductor. This drew a standing-room audience of some 12,000 to the New York University sports stadium. After playing Weber’s Der Freischutz overture, Willem van Hoogstraten conducted the New York Philharmonic-Symphony, with Gershwin at the keyboard, for Rhapsody in Blue. Three Hungarian Dances by Brahms followed and gave Gershwin a few minutes’ break before he returned to the stage to close the first half of the program by conducting An American in Paris himself. One reviewer described the dramatic scene and less-than-stellar conducting:

In due time Mr. Gershwin reappears to conduct his newest opus, “An American in Paris.” So tensely quiet are these 15,000 listeners that voices in the street two blocks away can be plainly heard. The young maestro is nervous. He stands rigid, merely beating time and marking the attacks of the violins on the one side and of the horns on the other.60

After the performance Gershwin was “hardly able to contain his enthusiasm,” the New York Times explained. “Never,” the paper quoted Gershwin as saying, “had he conducted before an orchestra or even a jazz band.” While observing that the composer would not claim to be a “virtuoso conductor,” the Times review describes the rookie effort more generously as displaying “a clear and admirable sense of rhythm” and notes that “he watched his score closely … giving these musicians the clean beat and the occasional cue.”61

Conducting the Manhattan Symphony three months later, Gershwin as maestro got an even stronger review from critic Edward Cushing: “The composer himself conducted, and with a competence that enlarged our opinion of his versatility.”62 Gershwin’s enthusiasm led to other conducting engagements with his tone poem, including a national broadcast on CBS on December 8 and a return to Lewisohn the next summer as both soloist and conductor.63 By adding conductor to his musical repertory, Gershwin opened up a new professional pathway. Rather than sit among the audience and acknowledge their appreciation after a performance of An American in Paris, the composer could now conduct onstage, earning an additional fee plus additional press that augmented his artistic reputation, celebrity, and income.

By far the largest audience reached by Gershwin’s new work was on Broadway as An American in Paris was incorporated as the Act II ballet of Show Girl – a theatrical narrative by Florenz Ziegfeld. While not a financial success, the lavish production dominated Broadway in the summer and early fall of 1929 and offered 118 performances from its Boston previews through its New York run. The Ziegfeld Theatre where it was produced had a capacity of 1,638 and thus the music of An American in Paris was heard by upwards of 100,000 ticket-buying patrons. Plans for a national tour and film version never came to fruition.

Based on a best-selling 1928 novel by J.P. McEvoy initially serialized in Liberty Magazine, Show Girl was already hugely popular before Ziegfeld took on the subject. Described in one review as “not overburdened with plot,”64 the backstage musical featured a spunky, aspiring Broadway showgirl named Dixie Dugan pursued by four suitors: saccharine salesman Denny Kerrigan; fiery tango dancer Alvarez Romano; Wall Street sugar daddy John Milton; and the ultimately successful suitor, writer Jimmy Doyle. In this rags-to-riches tale, Dixie finds not only love but also Broadway stardom.

The music was to be entirely by George Gershwin with lyrics by Ira Gershwin and Gus Kahn. Although facing what the composer called “the greatest rush job I’ve ever had on a score” after the hit Show Boat closed earlier than anticipated and the producer was faced with the prospect of a dark house, Gershwin still wrote some twenty-five new songs for the show.65 The most famous was and remains “Liza,” which brings the Act II show-within-a-show to a close. In several performances, including the Boston opening, Al Jolson rose from the audience to sing this song to his actual bride Ruby Keeler, who played the lead role of Dixie. The composer and lyricist’s brother Arthur Gershwin remembered that Jolson substituted “Ruby” for the title lyric.66 The stunt inspired considerable publicity.

As was typical of Ziegfeld’s lavish productions, Show Girl included a large and expensive cast: some fourteen principals, an oversized orchestra (to handle the instrumentation of Gershwin’s tone poem), three comedians including Jimmy Durante, and an all-female chorus of some seventy dancers. To this the impresario added Duke Ellington and his ten-piece Cotton Club jazz orchestra, which performed onstage for the Act I finale as well as the Act II floor show that culminated in “Liza.” The band then hustled off to play its regular sets at Harlem’s Cotton Club at midnight and 2 a.m.67

An American in Paris appeared in a fifteen-minute arrangement (slightly shortened by the composer) as the opening of a “new” Ziegfeld Follies show for which the heroine was competing for a featured role. The orchestra was conducted by Gershwin’s friend William Daly and may even have involved members of the Ellington band. The tone poem’s adaptation was likely inspired, if not made necessary, by Show Girl’s accelerated production timeline. By contract Gershwin had just four weeks to deliver the music.68 When Gershwin complained that he could not write an entire score in just a few weeks, Ziegfeld responded: “Why sure you can, just dig down in the trunk and pull out a couple of hits.”69 Gershwin ignored Ziegfeld’s suggestion when it came to the songs, but adapting An American in Paris as the instrumental dance number for the Follies show-within-a-show certainly saved the composer time and leveraged the new tone poem’s own popularity to boost Ziegfeld’s production. Reusing songs was anathema on Broadway, as it wasted the economic opportunity to feature a potential hit. Each new song was a new chance to sell more sheet music. Incidental music, however, was not typically sold in sheet music form and thus recycling previously composed work did not squander the chance to make more money.

Albertina Rasch, a frequent Ziegfeld collaborator, choreographed the An American in Paris ballet, featuring premier dancer Harriet Hoctor. The choreography was divided into three named scenes – “La Rue St. Lazare,” “Le Bar Americain,” and “Le Reve de l’Amerique” – that traced the orchestral work’s A (Paris)–B (New York)–A (back to Paris) form. The ballet focused on “half a dozen vividly colorful tableaux” and was generally praised as the “outstanding feature of the evening’s entertainment”70 and the “most magnificent number in the show.”71 The central homesick blues theme of Gershwin’s tone poem, intoned by a jazzy solo trumpet in the orchestral work, is reimagined in Show Girl as a song sung by Dixie’s Latin suitor Alvarez Romano. He is described as the son of the president of “Costaragua” and is presumably far from home.72 New lyrics created for Show Girl extend the melody’s theme of homesickness, already central to the orchestral work’s original narrative program, to Broadway:

It is unclear if the Gershwins made much money from Show Girl. Ziegfeld liked to have his songwriters on retainer even after a show opened in order to revise and respond to changes, but George, at least, did not report for this duty. By July 25, only a bit more than three weeks after the show’s Broadway debut, the impresario’s lawyer put the composer on notice that “although repeated demands have been made upon you to be present at rehearsals and fix the music of Show Girl, which you have agreed to do, you have failed to do the same, making it necessary for Mr. Ziegfeld to call in others to do your work.”73 Dated April 1929, Gershwin’s contract with Ziegfeld required that the music of Show Girl be made up exclusively of Gershwin compositions. The lawyer’s notice thus amounted to a breach of contract claim, releasing Ziegfeld from these original terms and allowing him to hire composer Vincent Youmans to revise the score.

The financial terms of the Ziegfeld contract were generous for Gershwin. The composer was due a royalty of 3 percent of Show Girl’s gross weekly box office receipts (i.e. of all ticket sales income before accounting for expenses), which should have amounted to a generous sum. In addition, Gershwin would receive 25 percent of any subsidiary monies – from radio licenses, other performances, foreign adaptations, etc. – received by Ziegfeld. If a film was made including Gershwin’s music, he would receive one-third of Ziegfeld’s royalty. Rights to the music itself, however, remained the sole property of the composer through New World Music Corporation. Ziegfeld was not entitled to any publication or mechanical rights to the music.

It may be that Ziegfeld stopped paying royalties once his lawyer got involved. In whatever event, the Gershwins ended up suing Ziegfeld for royalties due, but these appear never to have been paid. Show Girl closed on October 5, and on October 10 Gershwin wrote to a relative: “Ziegfeld (the rat) sent for me. On arriving in his office, he immediately threw both arms around me & only my great strength kept him from kissing me. He informed me he was so sorry we had a disagreement & was anxious to make up – send me a check for back royalties – & be friends. I consented but as yet no check has arrived.”74 The US stock market crashed just a few weeks later. Gershwin and Ziegfeld never again worked together.

The final strategy Gershwin used to earn revenue from An American in Paris was publishing. In 1927, Dreyfus formed New World Music Corporation as a Harms subsidiary to hold the works of George and Ira Gershwin. In early 1929, a photostatic copy of much of Gershwin’s handwritten score was made, bound, and sent to the Library of Congress for the purpose of copyright registration. It remains in the library’s collection and was stamped as received on February 15, 1929.75 Later that year, New World Music published a “solo piano” version of the score transcribed by William Daly. The piano edition is more accurately described as a proxy conducting score that contains indications of orchestration and muting as well as additional lines of music that go beyond the typical pair of piano staves. In 1930, An American in Paris was published as a full orchestral score – a largely unedited, but careful transcription of the manuscript – although without Gershwin’s handwritten changes to the score.

The economic strategies used by Gershwin to earn a living from An American in Paris run the gamut of the techniques he learned from his experience in Tin Pan Alley and Broadway as exemplified by “Swanee.” He wrote without a commission, confident of finding collaborators to propel the work and create a hit. Instead of Jolson as his outside celebrity sponsor, however, Gershwin leveraged the cultural authority of the New York Philharmonic-Symphony, the nation’s oldest and most prestigious orchestra, conducted by famed conductor Walter Damrosch. The attendant publicity led to subsequent orchestral performances, even in the first year of the work’s existence. Gershwin then sold non-exclusive licenses to others, initially for a radio premiere, earning money from the score while retaining the right to license subsequent uses. Recording created further avenues for both royalties and to reach new audiences, leveraging and reinforcing the work’s popularity and reputation. Soon the tone poem became the centerpiece of a Broadway show, at least theoretically helping to earn 3 percent of receipts while bringing Carnegie Hall respectability to Ziegfeld’s theater. Orchestral performances cross-promoted the new musical, most directly in Boston.

In turn, Ziegfeld’s show may have increased interest in summer orchestral performances for thousands at New York University’s Lewisohn Stadium. There Gershwin made his conducting debut, serving not only as composer of An American in Paris but also becoming one of its performers. Gershwin had long expanded his income as a composer by writing orchestral music that included piano solos for himself, as he did with Rhapsody in Blue and Concerto in F. Now he could appear in gala concerts, enhancing his celebrity, as a triple threat: composer, pianist, and conductor. Finally, Gershwin published An American in Paris as both a solo piano work and a full orchestral score, generating sales and a royalty through his publisher’s Gershwin subsidiary, New World Music Corporation. As with “Swanee,” one musical composition led to multiple streams of revenue. Gershwin thus saw An American in Paris not as a sacred and immutable object of classical veneration, but rather as a mutable artistic product that could and should be repackaged and adapted to a series of economic opportunities, each one increasing the value of the others.

This linkage between economic and artistic success was part of Gershwin’s creative identity from the very beginning. Responding to a 1920 interviewer in The Billboard on the heels of his success with “Swanee,” he optimistically charted a course for future success, both for himself and for American music in general:

I believe we are getting a better grade of music all the time. A composer doesn’t have to be afraid of writing a musicianly score nowadays, if he will only provide melody … I have used whole tone harmonies a la Debussy in one piece and it was very effective. One can write dissonances where a few years ago they would have been torn out of the score instantly … Creative effort is what is needed. Melodies must be treated in a novel way … and they must have a new twist if they are to get into the hit class. If you will analyze the songs which have made the biggest hits lately, you will find that some part of them, if only a bar or two, is a passage which strikes the ear as something new and pleasant … There is a lot of money waiting for the fellow who can write original scores.76

George Gershwin’s success was twofold. Increasingly asserting his creative talents, he was a savvy entrepreneur. Gershwin’s artistic ideology not only resolved the stylistic tension inherent in a distinctive US musical voice poised between classical and popular, but it also addressed the battle between music and money. As Gershwin’s sonic inspiration could come from any source – Tin Pan Alley, vaudeville, Broadway, the jazz club, the concert hall, and the opera house – so too could his financial tactics. He earned money from publications and performances, but also from recordings, broadcast rights, and licensing. While classical music’s economic anxiety is to avoid the dishonor of “selling out” one’s creative independence to the marketplace, Gershwin discovered that by selling his art effectively, he could achieve independence and enable his artistry. In addition to lucrative profits, his contracts gave him full creative authority. Earnings from hit songs made it feasible for Gershwin to take time off to compose. Rhapsody in Blue, Concerto in F, and An American in Paris, not to mention Porgy and Bess, would never have come into existence without Gershwin’s combination of artistic ambition and economic independence.