MR. POTTER'S MUSEUM OF CURIOSITIES was a small Victorian museum that contained unique anthropomorphic tableaux made by the taxidermist Walter Potter (1835–1918). Its glass cases were crammed with small “stuffed” or “mounted” animals, such as birds, squirrels, rats, weasels, and rabbits, wearing miniature clothes and placed in models of the human settings of Potter's time. They play sports, get married, fill schoolrooms and clubs, but they also illustrate well known sayings, rhymes, and rural myths. From the 1860s the tableaux were displayed in Bramber, Sussex, in the southeast of England. In 1972 the Museum was sold and relocated to Brighton and two years later to Arundel, in Sussex. In 1985 it was sold again and moved to the Jamaica Inn – a Daphne du Maurier inspired tourist attraction on the edge of the bleak Bodmin Moor in Cornwall. The collection was finally dispersed in an auction sale in 2003. This sale attracted some media attention and several campaigns attempted to preserve the museum intact. The artist Damien Hirst claimed he had offered to buy the entire collection, but the auction went ahead (Hirst). Hirst was perhaps only the most high profile of those campaigning to keep Potter's collection together. Nevertheless, at the time it seemed hardly surprising that this unusual museum stood more chance of being rescued by an artist whose work often uses animal corpses to speak of mortality and the processes of preservation and decay, than it did of being bought by any public museum.

Potter's museum was always marginal; in his own lifetime it was never more than a small curiosity museum, and his work was not something which would have been held by a major museum. But the failure to rescue it is partly attributable to a new anxiety about taxidermy on the part of British museums, which since the 1980s have tended to reduce their taxidermy on display, and which, for various reasons, no longer employ their own taxidermists. While a good proportion of museum visitors in Britain continue to appreciate taxidermy, for many, taxidermy of any kind (let alone the anthropomorphic kind) seems increasingly odd, and even unbearable. It no longer seems to be about nature, but about death.1

This assertion is based on my own experience of taking students around museums, listening to the conversations of visitors in front of displays of taxidermy, and on various discussions with museum staff, including an interview with Bob Bloomfield at the Natural History Museum in London in 2001. According to him, a good number of visitors to the museum had complained about the display of taxidermy, but many others had expressed disappointment at what they saw as a limited number of specimens. On the connections between taxidermy and horror, see Niesel, “The Horror of Everyday Life.”

Indeed, the anti-naturalistic taxidermy produced in the nineteenth century may be very revealing about nature – not nature as something eternal and outside human culture, but as something which is both cultural and historical. Rather than dismiss such taxidermy as grotesque or peculiar, we might see it as a significant branch of Victorian natural history and aesthetic practice. Alternative taxidermy practices that were developed in the nineteenth century depicted a cultural world thoroughly populated with animals and a natural world thoroughly mediated by cultural representations such as myths and folktales. The work of the three taxidermists I discuss here clearly develops out of some of the contexts in which taxidermy had long been employed by Europeans: as a museum practice in Plouquet's case, as a trophy practice linked to rural hunting and farming in Potter's case, and in the collecting of explorer-naturalists in Waterton's case. It also draws on the traditions of fakes and curiosity taxidermy. Yet, all three arrive at new and peculiar practices, shaped by specifically Victorian preoccupations, which tell of a world in which the relationship of humans to animals was being dramatically transformed.

The work of both Plouquet and Potter was typically displayed in tableaux. Tableaux, like the dioramas in natural history museums, are in-situ displays, which construct a small contextual world around the animals represented. Both invite the viewer to imaginatively enter the scene and daydream. However, while the diorama context helps to make the taxidermy it contains appear more naturalistic, the tableau-form of anthropomorphic taxidermy works differently. A tableau is a narrative form: animals are frozen in action to suggest both the scene's immediate past and what will immediately follow. In the habitat diorama, the moments before and after are often implied too: “before” the audience was wandering through the forest, suddenly they glimpse some deer grazing, in a moment the deer will flee. However, in anthropomorphic tableaux, the animals, not the viewers, produce the narrative. The positions of their bodies are not naturalistic but meaningful as the gestures and movements of actors in a narrative.

As Susan Stewart has argued, tableaux take a particular moment and freeze it so that the “instance comes to transcend, to stand for, a spectrum of other instances” (48). Even tableaux which do not employ taxidermy are a form of “arrested life.” The scale of taxidermic tableaux distinguishes them from the diorama too: the tableau is a world in miniature, in which a narrative is both temporally and spatially compressed, with the participants in a scene brought close together and attention drawn to the minutest of details (48). Miniaturisation intensifies the arrested moment, replacing the movement of time with a telescoping effect that is potentially just as endless. As Stewart observes, “This is the daydream of the microscope: the daydream of life inside life, of significance multiplied infinitely within significance” (54).

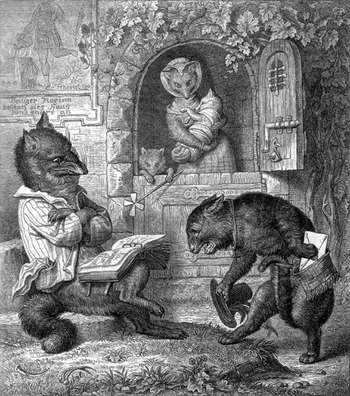

Anthropomorphic taxidermy became popular in Britain after Hermann Ploucquet's animal tableaux were successfully exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851. A book entitled The Comical Creatures from Wurtemberg was published following their exhibition. Here, Ploucquet's taxidermy was reproduced in the form of engravings, and some now had stories attached to them. The scenes are given titles such as “The Duel of the Dormice,” “Young Marten bidding farewell to Miss Paulina,” “Jack Hare and Grace Marten leading off the Ball.” As these titles suggest, the animals are engaged in human activities: dancing, attending school, hunting, duelling. Dame Weasel, for example, stands upright and cradles her baby in her front legs.

Other tableaux were more directly based on fables and folk-tales. If, as I have suggested, all tableaux generalize the specific instant, Ploucquet's tableaux also generalize the particular through his choice of narrative type, which is set in a mythic time and geography and in which each species stands for a type or is used to illuminate human character traits. For instance, several of Ploucquet's tableaux were illustrations to Goethe's satirical poem “Reineke Fuchs” (“Reynard the Fox”) of 1793 (see Figure 18) and, as one nineteenth century writer pointed out, seem to be directly based on Wilhelm von Kaulbach's 1846 illustrations to the poem (Fitzgerald) (Figure 19). The animals are unclothed, except for belts used to carry knives, and only a few props give clues to the era. Here, as in many (not all) of Ploucquet's tableaux, the animal is not a natural animal but a symbolic one. The character of Reynard, which can be traced back to the twelfth century has always been symbolic or allegorical: representing sin or “the devil in disguise,” “falsehood and treachery,” or “religious hypocrisy” (Varty 21–22). During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, in literature, drawings, and sculpture, he becomes well established as a vehicle for satire, especially religious satire (Varty 22, 59).

Hermann Ploucquet, “Sir Tibert delivering the king's message.” Taxidermy, c. 1851. Private Collection. Photograph courtesy of Pat Morris.

Wilhelm Kaulbach, illustration to Johann Wolfgang Goethe's Reinecke Fuchs (1846).

Foxes are common in British taxidermy, a staple of rural pubs, where they are sometimes shown carrying off a hen, and more rarely they illustrate folk beliefs about foxes’ behaviour. But the symbolic fox is rare, perhaps because taxidermy does not lend itself to symbolic representation. Roland Barthes’ observation about photography also holds true for taxidermy: it too is hampered by the fact that everything it represents has a singular existence. Since its material is the skin of an individual animal, it can eternalize the moment (as photography does) but is unable to detach itself completely from its referent (Barthes 4–7). Existing photographs of Plouquet's tableaux convey the problems in using anthropomorphic taxidermy to present a series of scenes from a narrative. Photographs of the Reynard tableaux show a number of different fox-cubs representing Reynard. In some, the animals’ bodies are pressed into clumsy and unnaturalistic positions more suited to a human body. By contrast, the engravings return Reynard to being one fox seen in a number of scenes, a fox who strikes semi-human poses with elegance and poise (Figure 20). Though Ploucquet's taxidermy is remarkably expressive, the engravings give the fox an appearance of mobility and a liveliness which would not be possible in taxidermy until Carl Akeley developed his technique in the 1920s at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.2

Some of the most hyperreal and muscular taxidermy dates from several years later: perhaps the finest examples at the AMNH are the big cats in the Hall of North American Mammals, which opened in the 1940s.

“Sir Tibert delivering the king's message.” Illustration from The Comical Creatures from Wurtemberg; including the Story of Reynard the Fox with twenty illustrations drawn from the Stuffed Animals Contributed by Hermann Ploucquet of Stuttgart to the Great Exhibition (London: D. Brogue, 1851).

Ploucquet's other tableaux have much less narrative content and are more about simply representing human social situations using animals. John Berger usefully distinguishes between different kinds of anthropomorphism in his essay “Why Look at Animals.” Of the illustrations in Grandville's Private and Public Lives of Animals (1840–42), he argues:

These animals are not being ‘borrowed’ to explain people, nothing is being unmasked; on the contrary. These animals have become prisoners of the human/social situation into which they have been press-ganged. The vulture as landlord is more dreadfully rapacious than he is as a bird. The crocodiles at dinner are greedier at the table than they are in the river.

Here animals are not being used as reminders of origin, or as moral metaphors, they are being used en masse to ‘people’ situations. The movement that ends with the banality of Disney, begins as a disturbing, prophetic dream in the work of Grandville. (19)

According to Berger, Grandville's drawings prophesy the marginalisation of animals, which was then beginning. Disney marks an end consequence of this process, and universalizes “the pettiness of current social practices” by projecting them onto the animals’ world (Berger 19). This is true not only of Disney of course, but of many recent animated films – Finding Nemo, for instance, which begins with two clownfish discussing their new home (an anemone) in the ways contemporary middle class North Americans might discuss real estate. In Ploucquet's tableaux too, animals could be said to simply inhabit human situations. They do have the vestiges of their animal characteristics and relationships: the marten holds the cockerel by the throat in “Mr. Bantam's interview with Old Marten.” Just as the stories of Reynard tell us something of cultural attitudes to foxes, the animals in these tableaux are turned into particular kinds of people based on the cultural associations of each species. However, the qualities associated with animals, the cunning of the fox for instance, are not intensified by their being placed in human situations: rather the taxidermy struggles to represent the fox as cunning, something the more fluid engravings manage with ease. This difficulty in adequately conveying the vices and virtues culturally attributed to various species separates taxidermic anthropomorphism from that of Grandville, Kaulbach, and other illustrators. The fact that the living animals’ bodies would not be able to manage the poses struck by their mounted skins heightens the sense that animals are being forced to populate human situations. This impression is even greater in Walter Potter's work, where, as in Grandville, the animals appear en masse, and where the taxidermy is, in my view, rather more inexpressive and stiff.

Potter was sixteen at the time of the Great Exhibition and, possibly inspired by Ploucquet's work, began producing his own animal tableaux in the 1850s. His tableaux are very different from Plouquet's, even where they represent the same activities. The differences are related to their status and the contexts in which the two men worked. Ploucquet was a taxidermist at the Royal Museum in Stuttgart; Potter was the proprietor of a small village curio museum which included many of the staples of Victorian curio museums. Both used indigenous species, but Potter outdid Ploucquet in the sheer number of animals in his tableaux and the lengths to which he took his anthropomorphism. Ploucquet displayed a rabbit being beaten by a weasel (or marten?) schoolmaster, while three other rabbit schoolchildren wrote on their slates; Potter produced a whole class of rabbits in a village schoolroom (Figure 21). His first tableau “The Death of Cock Robin,” begun in 1854, includes ninety-six British birds. Other tableaux make use of large groups of guinea pigs, rats, squirrels, kittens, and rabbits – with between ten and twenty animals in each case.

Walter Potter, “Rabbits’ Village School,” late nineteenth century. Taxidermy. Private collection. Author's photograph.

Potter's tableaux are not about universals. They are filled with the furnishings and social activities of his own era. Some animals are clothed and some wear jewellery. Some tableaux represent human social activities, in schoolrooms, drinking clubs, croquet and cricket lawns, with great attention to detail. Other tableaux illustrate rural myths and sayings relating to animal behaviour: “A Friend in Need …” is based on the belief that rats cooperate with one another and shows two rats collaborating to take the bait from a trap. This tableau depicts a human-like behaviour which was thought characteristic of rats, but there is no need to assume from this that Potter's work is moral allegory or that it makes much use of animal symbolism. In Potter's anthropomorphism, species are not consistently associated with specific character types as they are in the anthropomorphic tradition which Ploucquet draws on, and which we find in the fable. In animal fables, we usually expect to meet only one representative of each species, but Potter overpopulates his tableaux with members of the same species. Nor do different species straightforwardly represent different social classes or social roles, though they may seem to at first glance: “The Upper Ten” has eighteen squirrels representing the clientele of a gentlemen's club, and “The Lower Five” uses rats to depict a working class club (Figure 22), but the servant to the gentlemen is another squirrel and rats play the part of policemen who have caught the other rats illegally gambling.

Walter Potter, “The Lower Five (The Rat's Den),” late nineteenth century. Taxidermy. Private collection. Author's photograph.

Walter Potter has been grouped with Beatrix Potter, in the way he humanises animals by dressing them as people, and places them in human social situations (Blount 73). His anthropomorphism is certainly closer to hers than to Aesop's or Ploucquet's. But there are significant differences. In The Tale of Tom Kitten, Tom and his sisters are kept out of the sight of their mother's “fine company” because their mother is ashamed of their inability to conform to civilized/grown-up/human behaviour: they have dirtied and lost their clothes and had difficulty walking upright. In Potter's tableaux the kittens do not lapse into feline or childish behaviour because they are not kittens trying to be society ladies or wedding guests; they simply are. The fact that kittens are not adult animals, or that they are feline, has nothing to do with it. In some of Potter's larger tableaux, the creatures seem to simply function as dolls.

As with dolls’ houses, Potter's scenes show a hermetic world in miniature. He almost always used small animals in his tableaux. One of the most interesting aspects of miniaturization is its apparent effect on our experience of time. Stewart refers to a research experiment in which adult subjects’ experience of time as they played with scale-models was found to change in proportion with the scale of the model, so that time seems to pass more slowly at smaller scales (66). She explains that re-enacting everyday activities on 1/12 scale creates a subjective experience of time, which is dreamlike because compressed. Of course, it doesn't follow that merely gazing at miniature tableaux would have the same effect. However, if the diorama is a frozen version of a subjective experience of nature (a glimpse, a scene stumbled upon), then the miniature anthropomorphic tableau presents us with a scene that at least reminds us of the private dream time of dolls’ house play. Stewart views miniatures in general as placing the observer in a position of omniscience, but the power of being able to see the whole, all at one time, is qualified by the impossibility of entering the miniature scene (66). This is more true of the museum tableaux of Potter, protected from our tampering by their glass cases, than the dolls’ houses of childhood into which we can enter through imaginative play. The enclosed world of the tableau invites nostalgia because of the association of miniaturization with childhood, and with a private temporality which is outside time, along with the delicate handiwork of a pre-industrial world (68).

Walter Potter's miniature tableaux double this nostalgic effect, because they tie it to a specifically English, and predominantly rural, folk culture. Potter's taxidermy could be described as an astonishing manifestation of naïve art, combining self-taught craft with a folkloric content (rural life and sayings) and local materials (native species). The Potter's Museum visitors’ guide encouraged visitors to read his work as the product of a more innocent age; a time when animals were plentiful and rural life relatively unchanged by industrialisation. It states that: “many of the things here shock us today, but are a reminder of how activities and attitudes have changed. In Potter's day wildlife was much more abundant than now and nobody had any reason to worry about things getting rare” (Morris, Mr Potter's Museum, 16).

This view of Victorian and Edwardian England is meant to protect against offence and addresses a contemporary sensibility: we are told that the kittens were “abandoned” by their mothers, white rats were donated after they turned “vicious.” When I visited the museum, another story was also suggested: that some animals would otherwise have been turned into fur cuffs for women's clothes – the only glimpse we get of the semi-industrialized countryside. Potter's work combines a number of late Victorian fascinations: with the miniature, with natural history and with folk culture, with childhood. It is a microcosm of an era in which the accelerated destruction of the old social order and of nature was accompanied by an increasing obsession with preservation and memory. His work is evidence of the fragile co-existence of English wildlife and human life, as well as their interdependence. It is a practice only possible in a narrow historical moment.

Whilst it is true that wildlife was more abundant in the nineteenth century than today, nevertheless the decimation of British wildlife was noticeable half a century before Potter began his first tableau. Animals were killed indiscriminately by all social classes, on the basis of superstition, for the pleasure of hunting, for food, or for the trade in feathers and fur. By the 1840s the north of England was heavily polluted by the rapidly developing industries. Charles Waterton (1782–1865) wrote that he had sighted his last buzzard on his estate Walton Hall, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, in 1813, that the kite had disappeared from there and the last raven was shot in 1820 (Waterton 1: 184).

Waterton was also an anthropomorphic taxidermist – of sorts. This Roman Catholic aristocrat, naturalist, and taxidermist became famous through the publication of his Wanderings in South America (1825) and gained a reputation for eccentricity. His reputation was partly based on his commitment to providing a safe haven for wildlife, his outspoken criticisms of his peers, as well as his refusal to conform to the conventions of his time. It was cemented by the publication of a highly inaccurate and mythologizing posthumous bibliography by Richard Hobson, and later by his inclusion in Edith Sitwell's English Eccentrics. According to a more recent biography by Julia Blackburn, Waterton was ahead of his time in some ways: he was pioneering in his attitude to conservation and ecology, and particularly irritated by the tendency of other naturalists to present animals as fierce and dangerous in order to exaggerate their own bravery. Blackburn states that one of the unfortunate effects of the way his reputation has been constructed is that his intimacy and gentleness with animals were misrepresented as reckless demonstrations of bravery (192). Nevertheless, as Christina Grasseni has argued, “Even that which has been written in defence of the Squire has portrayed him as a solitary soul at odds with his own time,” whether ahead of his time or behind it (272).

The other source of Waterton's reputation for eccentricity was his use of taxidermy as a vehicle for satire. During his travels in Guyana, Waterton had collected animal specimens and perfected a laborious taxidermy technique that involved chemically hardening the skin and then shaping it so that the end result was a realistic and anatomically accurate but completely hollow specimen. He produced a number of straightforward taxidermy specimens and was proud of their naturalistic appearance. But he also produced satirical “creations” or “assemblages” which are made from animal skins manipulated to take on a human appearance and/or various animals collaged together to produce grotesque and fantastic creatures. The majority of these were political satires: critiquing government policy or taking a swipe at Protestantism, or both. A man of his class would usually have entered into politics, but as an English Catholic, Waterton refused to take the Oath of Allegiance. Taxidermy was his craft and his chosen means of expression.

Waterton's hybrids are not anthropomorphic in the traditional sense. His “creations” are not “people with animals’ heads,” or animals which have become civilized (Blount 70–92). In fact, Waterton was very much opposed to some of the ways in which Victorian popular culture anthropomorphised animals. His own identification with animals can also be understood as anthropomorphic – but the distinction between his own anthropomorphism, and that which he opposed is drawn in his own account of his visit to a captive ape on show in Scarborough. The ape had been given the name Jenny and lived with a young woman in an attic room, where people would pay to see her. She was dressed in clothes and fed a human diet. Waterton wrote:

‘Farewell, poor little prisoner,’ said I. ‘I fear that this cold and gloomy atmosphere of ours will tend to shorten thy days.’ Jenny shook her head, seemingly to say, there is nothing here to suit me. The little room is far too hot; the clothes which they force me to wear are quite insupportable, whilst the food which they give me is not like that upon which I used to feed, when I was healthy and free in my own native woods. (Waterton 3: 66–67)

According to Blackburn, Jenny was a gorilla, the first to be displayed in England, though this was not known at the time (194–95). The way in which she was displayed was common: while British wildlife were studied assiduously by legions of amateur naturalists, there was a great deal of ignorance about the exotic beasts of far-off lands, which were displayed in travelling shows and zoological gardens. The resemblance of apes to humans, recalling the more shocking aspects of evolutionary theory and complicated by the belief in distinct and separate races of humanity (a belief repeatedly reinforced by a popular culture designed to boost working class support for Empire), seems to have provoked a great deal of uneasiness. The practice of masquerading orang-utans, chimpanzees, and, later, gorillas as humans, forcing them to wear clothes and eat human food, allowed the animal's closeness to humans to be recognized, but simultaneously assuaged the anxiety produced by this recognition through ridiculing and infantilizing the animal.3

For a discussion of popular displays of apes in Britain, see Ritvo, The Animal Estate, 31–39 and 228.

In other words, anthropomorphism became a means for nineteenth century popular displays to negotiate the problematic relationship between people and animals for a thrill-seeking audience. They shared with the curiosity cabinets of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries a fascination with the anomalous, the hybrid, and the grotesque. By contrast, the Victorian and Edwardian natural history museums rejected such explicit anthropomorphism and through techniques of scientific classification of the natural world produced a vision of a natural world marked by clean boundaries between types and species. Thus, and despite their differences, both the public museums and the popular anthropomorphic displays inhibited the recognition of like and not-like, which, as John Berger has suggested, the encounter with a wild animal might otherwise produce (6–7).

When Jenny died in 1856, Waterton had few qualms about using the corpse anthropomorphically. When the corpse was sent to him to be preserved, he decided to use it as one of his “creations.” Unfortunately this “creation” is now lost, but according to Blackburn he added a donkey's ears and called it Martin Luther (194–95). If his attitude to the exhibition of the live gorilla marks his distance from the popular display culture of the time, then his treatment of the corpse establishes his distance from the respectable world of “closet” natural history, where a dead specimen is material for study, not satire.

Waterton's taxidermic satires do not belong to either of these contexts, though he had some relation to both worlds. He was fascinated by displays of miracles and wonders. He also participated in public displays of the effects of the poison curare (his research into curare is one of the things for which he is best known), and received at least one example of a “mermaid” to assess its authenticity. He was offered, but refused, the opportunity to exhibit some of his taxidermy at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Though his work in naturalism did earn him the respect of other naturalists, he was very scathing about “closet naturalists” who had no experience in the “field” (Barber 107–10).

The most famous of his satires was the “Nondescript” which was exhibited in Georgetown, Guyana, and reproduced as the frontispiece of his Wanderings. It was seen as ingenious and humorous by some but also as casting doubt on the veracity of his accounts of his travels and his authority as a naturalist. The Nondescript appears as an odd, round-faced little man. Waterton accompanied its display with an account of how he had caught this strange creature – which seemed halfway between man and ape – and how he had cut off its head and shoulders and brought it back. In fact the “Nondescript” was fashioned out of a monkey's skin – probably the back end of a red howler monkey – and the mouth was probably originally the animal's anus. The “Nondescript” has been read as a satire on the credulity of the viewing public and as a joke at the expense of other scientists and their preference for the classification of dead specimens over field naturalism (Ritvo, The Platypus and the Mermaid 55; Grasseni). Waterton's interest in the curious and the marvellous and a strong dislike of closet naturalists gives credence to Grasseni's view that it was the scientists, not the credulous crowd, who were the target for this satire.

Stephen Bann also uses the “Nondescript” to understand the construction of identity, specifically, the identity of the traveller for whom home is “a place of conflictual identity” because of his alienation from a Protestant dominated political hierarchy (157–58). Making monsters is an ideological working-through of this dissenting identity. Similarly, Grasseni argues that taxidermy becomes, in Waterton's hands, a means of self -representation, “an eloquent practice of self-making” (281). By showcasing his unique taxidermy technique in the form of the “Nondescript,” Waterton was demonstrating taxidermic mastery while inviting debate about “what constitutes ‘naturalness’, and about who has the authority to describe and appropriate it” (286). Grasseni reads Waterton's taxidermic practice as an assertion of the importance of making over naming as a form of description, and as a critique of established views of what constituted scientific truth (281, 286). She sees taxidermy as a means by which Waterton inscribes and legitimates his own identity, and his privileged and exceptional access to animals.

Nevertheless, Waterton's taxidermy also serves as a representation of the world. We can understand his “creations” as participating in the tradition of the grotesque. According to Mikhail Bakhtin, grotesque realism develops in the folk culture of the middle ages, and takes on different forms in the Renaissance and in Romanticism. Bakhtin describes it as degrading and materializing: bringing its subjects down to earth and emphasizing the lower body; presenting bodies as “unfinished,” “open,” “blended with the world, with animals, with objects”; representing life as teeming, profuse, and diverse (20–21, 26–27). Likewise, Waterton puts the lower body where the upper should be, blends human and animal, disregards species boundaries, and creates monsters, some gently humorous, some outrageous, and some with slightly mocking or Mona Lisa smiles. “Martin Luther after his Fall,” the “Nondescript,” and “John Bull and the National Debt” are all memorable for their very human facial expressions (Figure 23). “John Bull and the National Debt” is an example of Waterton's “assemblages,” teeming with various hybrid creatures.4

Gordon Watson, the curator of the Waterton exhibit at Wakefield Museum in Yorkshire at the time I visited, distinguished between the “creations” where Waterton manipulates animal skins to make a different creature, and “assemblages” which are made up of several hybrid creatures.

Charles Waterton, “Martin Luther after his fall,” late nineteenth century. Taxidermy. By courtesy of Wakefield Metropolitan District Council, Public Services Department, Museums and Arts. Author's photograph.

This contrasts sharply with the aesthetic of the diorama as reinvented by Carl Akeley and his colleagues. In the habitat diorama, the wilderness is represented as the sublime. These dioramas are conventionally empty of human presence, and every species is represented in family groupings or herds, each with their own individual diorama. The clean separation of species from one another, of animals from humans, and the presentation of perfect specimens against a backdrop of wilderness give a very different impression of the natural world than that provided by Waterton's work. In Waterton's taxidermy cases, human and animal commingle and become one, the social order is translated into nature, fiction and reality converge.

To representations that “freeze” life in a snapshot of eternal youth, grotesque satire responds with an image of life and death intertwined. Bakhtin characterizes the grotesque as that which, “seeks to grasp in its imagery the very act of becoming and growth, the eternal, incomplete, unfinished nature of being. Its images represent simultaneously the two poles of becoming: that which is receding and dying and that which is being born” (52). The political content of the “creations” is not only what they explicitly ridicule (such as Lutheranism), nor solely the debate about scientific authority and Waterton's own social legitimacy, but also this vision of human-animal life. Perhaps Waterton's “wanderings” in the jungle of Guyana had shaped this vision, and perhaps it was also his experience, at the age of twenty-two, of catching yellow fever in Malaga. According to Blackburn, this left him able to walk immune through the plague-stricken port, in which thousands of people died, and where he witnessed human corpses piled one upon the other in communal graves (21–26). After this he took up the practice of treating his own illnesses with bloodletting and purging, a practice he continued throughout his long life. He also seems to have started regarding his own illnesses and injuries and near-death experiences in the jungle, with a detached curiosity rather than self-pity. In any case, in his assemblages, Waterton produced an impression of a teeming, unclassifiable living world, using dead animal material.

Although these animal remains were probably the leftovers of his other taxidermic practice, mostly animals that had died in captivity and were donated, Waterton's taxidermic satires are commonly viewed as peculiar and rather tasteless, even by Blackburn, otherwise his most sympathetic biographer (195–96). Perhaps Blackburn dismisses them because they inhibit attempts to have him recognized as a serious naturalist, seeming to be a gratuitous use of taxidermy, as opposed to its more justifiable use for the preservation and identification of specimens. However, the rehabilitation of Waterton as a respectable naturalist might only be achieved at the cost of ignoring or excising what Grasseni refers to as his own “deliberate construction of difference” (290). Nor is this grotesque aesthetic at odds with the contemporary view of Waterton as an ecological pioneer. The assemblages are one product of Waterton's tolerance toward the disorderliness and interdependence of “creeping” nature, which led to the transformation of his estate near Wakefield in Yorkshire. Blackburn states that the Walton Hall estate became a kind of “Western jungle, with ancient hollow trees allowed to die slowly and undisturbed, with dense bushes, trailing ivy, crumbling walls, swamps and marshes, and endless possible hiding places for birds and animals” (168).

The work of each of these three taxidermists, Herrmann Ploucquet, Walter Potter, and Charles Waterton, is situated differently in the display culture of the nineteenth century. Even so, Potter's curiosity museum, Ploucquet's display at the Great Exhibition, and Waterton's display in the staircase of his own home, Walton Hall, all contained examples of taxidermy which sit outside the development of taxidermy as a form of scientific illustration and/or preservation. At the time they seem to have been regarded as amusing or marvellous oddities – if Waterton's “creations” caused some offence, it was not for the reasons they might today. This anthropomorphic taxidermy is not all easy to trace. Some of Waterton's “creations,” including the “Nondescript” and “John Bull and the National Debt” are held at the museum in his hometown of Wakefield, along with a room devoted to his work as a naturalist and displaying his other taxidermy. Plouquet's Reynard the fox tableaux were sold privately in an auction of the contents of Stoneleigh Abbey in 1981 but many of his tableaux remain untraced.5

The zoologist and natural history author Pat Morris has researched missing taxidermy collections (“Lost Found and Still Looking”).

Today, the museum displays constructed in the United States by Carl Akeley and his followers in the first part of the twentieth century are regarded as historical pieces and their preservation is advocated on these grounds: that is, they no longer serve the purpose of adequately or accurately representing the species and habitat they depict but they nevertheless have come to be regarded as masterpieces of scientific illustration. Even so, their permanent preservation is not yet entirely assured. This is even more the case for Victorian and Edwardian anthropomorphic and assemblage taxidermy, which was, and remains, a marginal art. Although it now finds a place in the collectors' market for Victorian and Edwardian taxidermy, in a society where museums are uncomfortable about displaying taxidermy at all, it is difficult to put the case for its historical value. It would be unfortunate if contemporary attitudes toward taxidermy were to obscure what these practices may reveal about their time and about our own.

Thanks to Gordon Watson of Wakefield museum for sharing his expertise on Waterton with me when I visited. Also to Tia Resleure, whose well-researched website, www.acaseofcuriosities.com is an excellent source of information about Potter and Ploucquet. Thank-you to Kenneth Varty, Pat Morris, and Ken Everett for their kind help in locating the illustrations, and to my neighbour Arlo, for lending me the Potter's Museum Auction catalogue. This essay is based on research funded by the British Academy in 2000 and by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the University of the West of England in 2004.