This chapter will look at what I call the ‘flip side’ of Krautrock. That is to say I will focus on the political, social, economic, and cultural developments in 1970s West Germany that this music genre did not reflect, rather than those it did. The protagonists of Krautrock posed as the cultural avant-garde of their era, a stance that is often uncritically adopted by commentators.Footnote 1 In fact, as I will show here, Krautrock was essentially a highly conservative music movement. There are three good reasons for this.

First, Krautrock was almost exclusively dominated by heterosexual men. Consequently, it had no links to the women’s rights movement of the time. In the first part of this chapter, I will show that feminist values were reflected in German pop and rock music made during the decade of Krautrock – but only in genres outside of Krautrock itself. A connection between Krautrock and women’s liberation only took place in the transition period to Neue Deutsche Welle, or NDW (German New Wave) at the beginning of the 1980s.

Second, Krautrock was almost exclusively the domain of white, German men, who often came from wealthy, upper-middle-class backgrounds. Despite this, Krautrock presented itself as an international, cosmopolitan movement. Apart from Can’s two vocalists – Malcolm Mooney and Damo Suzuki – musicians from diverse ethnic backgrounds were rare on this scene. West Germany’s gradual transition from an ethnically homogeneous to a multicultural society in the 1970s is therefore not reflected in Krautrock. For this reason, I will mention the migrant community most prominently represented in Krautrock – the Turkish labour migrant community or Gastarbeiter (guest workers).

Third, despite its emphasis on cosmopolitanism, Krautrock also featured a group of bands that aimed to rediscover and preserve German cultural traditions. These bands took their names from famous Romantic poets, set medieval poetry to music, or sang in the regional dialects of north and south Germany. While canonised, cosmopolitan Krautrock is regarded outside Germany as the most important, formative, influential music to emerge from post-war West Germany, within Germany the impact of this traditionalist movement has been far greater: it continues in Mittelalter Rock (medieval metal) bands who have enjoyed commercial success since the early 1990s in a reunified Germany.

Feminist Approaches: Inga Rumpf, Juliane Werding, Schneewittchen, and Claudia Skoda

Krautrock, as the genre has been canonised in recent decades, remained a purely male affair. Apart from Renate Knaup, the singer from Amon Düül II and, briefly, Popol Vuh, there were no prominent women in this music genre. For this reason, its political impact was limited. Krautrock had no connections to the German feminist movement of the 1970s. Women’s sexual emancipation played no role in Krautrock – in fact, the entire subject of sexuality was strangely absent. This is even more astonishing in a decade that was essentially all about sexual liberation.

The first female rock band in Germany, The Rag Dolls, from Duisburg,Footnote 2 were founded in 1965 and oriented on American rhythm and blues and British beat music. They named themselves after a song by the Four Seasons; the only single they recorded was a cover version of ‘Yakety-Yak’ by The Coasters. Despite numerous performances, The Rag Dolls failed to produce another single, let alone an entire album. They disbanded in 1969.

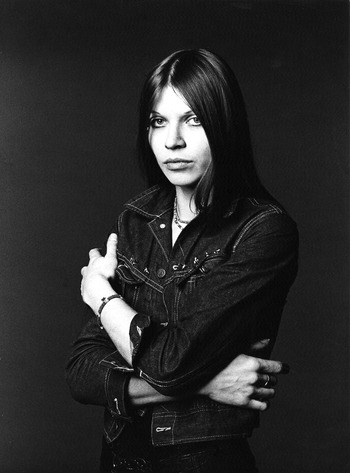

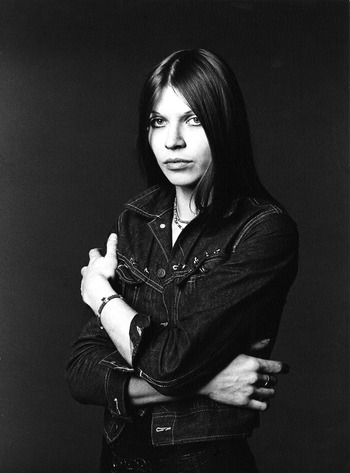

The most prominent German female rock singer at the beginning of the 1970s was Inga Rumpf. She started her career in 1965 in the folk band City Preachers, from which the rock band Frumpy emerged in 1970. In 1972, Rumpf founded Atlantis with former Frumpy members Jean-Jacques Kravetz and Karl-Heinz Schott. Their name and the psychedelic design of their album cover art were inspired by the burgeoning style of Krautrock, yet they remained strongly rooted in blues, jazz, and soul. Not least due to their English song lyrics, the leading German music magazine Sounds described them as ‘the “most English” of German groups’.Footnote 3 Rumpf was soon considered a female role model. On her first solo album, Second-Hand Mädchen (Second-Hand Girl, 1975), she sang in German for the first time. The title track is one of the first female empowerment songs written in German. Defying male expectations, her lyrics encouraged young women to refuse to dress in ‘glitter jackets’ or wear ‘sequins’ to get ahead in their careers, proudly stating ‘meine Nähte sitzen schief und krumm’ (the seams on my clothes are crooked).

Illustration 15.1 Inga Rumpf.

In 1975, a hit feminist anthem was also released: ‘Wenn du denkst du denkst dann denkst du nur du denkst’ (When You Think You Think, Then Only You Think You Think) by Juliane Werding, written by Gunter Gabriel. The lyrics of this hit single encouraged women to behave ‘like men’: to drink as much as they could in the pub without falling over, and to win at cards. Werding started her career as a political pop and folk singer in 1972. Her first hit ‘Am Tag, als Conny Kramer starb’ (The Day Conny Kramer Died) was a cover version of ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ by The Band, but with different, German lyrics: Werding’s version mourns a friend who has died of a drug overdose. She was also one of the first singers to focus on environmental pollution and ecological disaster in ‘Der letzte Kranich vom Angerburger Moor’ (The Last Crane on An-gerburg Moor).

In 1976, the first group formed who explicitly saw themselves as a mouthpiece for second-wave feminism, the all-female Schneewittchen. They were led by the folk singer, guitarist, and flute player Angi Domdey. She had previously played in a jazz band. Schneewittchen, however, combined German folk songs and blues ballads with feminist messages. Their debut album Zerschlag deinen gläsernen Sarg (Frauenmusik – Frauenlieder) (Smash your Glass Coffin (Female music – Female songs)) was released in 1978. For example, on ‘Der Mann ist ein Lustobjekt’ (The Male is an Object of Lust), Domdey critiques the sexualised male gaze on women by reversing it, while on the title track of the album she demands:

These are some of the few feminist voices in German pop music in the mid-to-late 1970s. However, they developed independently of Krautrock or were even – in the case of Inga Rumpf, Frumpy, and Atlantis – diametrically opposed to its musical style. There was, nevertheless, one exception: Die Dominas (The Dominatrices) emerged in West Berlin in the early 1980s, consisting of fashion designer Claudia Skoda and her model Rosi Müller. Their first and only single was produced by Ash Ra Tempel’s founder Manuel Göttsching, while the cover was designed by Kraftwerk members Ralf Hütter and Karl Bartos.

Claudia Skoda was one of the defining figures of West Berlin’s underground scene in the early 1970s and beyond. She designed avant-garde knitwear, combining wool with polyester yarn and tape from music cassettes. In 1972, Skoda moved into a factory floor in Berlin with artist friends who named their headquarters ‘fabrikneu’ (mint condition, or literally: ‘factory-new’) in an allusion to Andy Warhol’s Factory. Klaus Krüger, who experimented with homemade drums and later worked with Iggy Pop and Tangerine Dream, belonged to this community.

The fabrikneu family maintained close relations to the Krautrock scene. Amon Düül II often stayed at fabrikneu when he was in Berlin, and Göttsching wrote music for Claudia Skoda’s fashion shows in 1976. The highlight of their collaboration was the 1979 fashion show ‘Big Birds’:

There was no longer any catwalk in the classical sense. … The team of acrobats consisted of Salomé and Luciano Castelli, who would later become famous as painters and performers with the ‘Junge Wilde’ tendency, along with the Australian duo Emu, who hatched out of a large egg at the start of the performance. Screened concurrently was a film of penguins in the Antarctic.Footnote 4

Göttsching provided electronic music. ‘He began with a simple heartbeat, which immediately drew the public into his narrative, at the same time providing a foretaste of the never-ending tracks, characterised by repetition and phrase displacement, that would become so formative for the sound of the time.’Footnote 5 Göttsching started working with computers in 1979, first with the Apple II, then with early Commodore and Atari models. In 1981, his first solo album, E2–E4, recorded exclusively with electronic instruments, was released. It inspired Claudia Skoda to store her knitting patterns on punch cards and in the early 1980s she also began to make her knitwear with the help of Atari computers.

Together with Rosi Müller in the duo Die Dominas, Skoda sang about sadomasochism to Göttsching’s minimalist beats: ‘Schlag mich / schlag mich nicht / Schmerz, wo bist du?’ (Hit me / don’t hit me / pain, where are you?). Minimalism and sadomasochism were also echoed in the music of the first successful album by Deutsch-Amerikanische Freundschaft, Alles ist gut (Everything is Fine), released in 1981. It was not until the 1980s that Krautrock music became sexualised, and the first women performers staked their claim, but this transition occurred when Krautrock was already giving way to post-punk and Neue Deutsche Welle.

Krautrock was therefore blind to German society’s feminist awakening. Despite its avant-garde aspirations, its line-up had a highly conservative character, especially on the topic of sexual politics. Feminist expression was more likely to be found in music genres maligned by Krautrockers and their supporters, such as German Schlager or in rock based on Anglo-American models. Strong indications of feminist tendencies only featured on the West German underground scene when the era of Krautrock was over.

Migrant Voices: Türküola, Metin Türkoz, Cem Karaca, and Ozan Ata Canani

Krautrock was not only almost exclusively a male domain: the men who dominated the scene were almost all white Germans. Musicians with diverse ethnic backgrounds were few and hard to find, with the notable exceptions of Malcolm Mooney and Damo Suzuki, vocalists with Can, and the female Korean singer Djong Yun, who featured on records by Popol Vuh. These exceptions were evidently made for the singers’ ‘exotic’ appeal. Diverse voices were not represented in Krautrock as a matter of course, which once again shows its political failings. From 1968 to 1980, the number of ethnic migrants in West Germany increased from 3.2 to 7.2 per cent, or from just under 2 million to roughly 4.5 million.Footnote 6 This influx profoundly changed West German society, but the increasing visibility of migrants was barely reflected in Krautrock.

In the 1960s, however, a flourishing music scene developed among Turkish migrants living in Germany. They were the largest migrant group from 1961 onwards. Following a government drive to recruit Gastarbeiter, by 1973, some 867,000 workers from Turkey alone had come to live in West Germany.Footnote 7 The Turkish music scene was just as strictly segregated from the German cultural scene as its people were from German society. Significantly, Germany’s best-selling independent record company in the 1960s and 1970s was one that produced Turkish-language music for migrants living in Germany.

The record label Türküola was founded in Cologne in 1964 and still exists with a catalogue that comprises more than 1,000 albums, singles, and compilations. Its vinyl records and, later, compact cassettes were not distributed through regular record shops but in corner grocery shops and other stores that were part of the German-Turkish community. Türküola’s most successful artist, Yüksel Özkasap, nicknamed Köln’ün Bülbülü (The Cologne Nightingale), sold 800,000 copies of her 1975 album Beyaz Atli (White Horseman). But that went unnoticed by German society; Özkasap did not appear on any TV shows, nor were her immense sales reflected in the official album charts because of the label’s unconventional distribution channels.Footnote 8

Another prominent Türküola artist was Metin Türkoz, who started his career in Germany as an assembly line worker in Cologne’s Ford factories. From the late 1960s to the early 1980s, he sang about his own experiences and everyday problems, and the longings and dreams of first-generation migrants. For example, in ‘Guten Morgen, Mayestero’Footnote 9 (Good Morning, Mayistero), Türkoz switches back and forth between German and Turkish, in a slightly mocking conversation with his line manager. At the turn of the 1980s – because of Germany’s economic crisis and the resulting rise in unemployment – Türkoz also incorporated racist slogans such as ‘Ausländer raus!’ (Foreigners out!) into his lyrics as these were now heard more and more often in real life. He was the first singer to systematically mix German and Turkish slang words, a technique that became a key stylistic device in the next generation of German-Turkish music rappers like Microphone Mafia and Eko Fresh or, most recently, Haftbefehl.

From the end of the 1960s, the Türküola label also released albums by Cem Karaca, one of Turkey’s best-known musicians. He combined Anatolian folk style with elaborate soundscapes and elements of progressive rock and psychedelic music, coming surprisingly close to the aesthetics of Krautrock. Karaca’s lyrics took up the theme of social revolution as well as calls to resist Turkish nationalism. Yoksulluk kader olamaz (Poverty Need Not Be Fate) is the title of his 1977 album. ‘Safinaz’, released the following year, was a rock symphony inspired by Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ on the difficult fate of a working-class girl. When political tensions in Turkey intensified – culminating in the military coup in September 1980 when a military junta seized power, imposing martial law and banning all political parties – Karaca emigrated to Germany and remained there until 1987. He founded a German-language band called Die Kanaken (The Kanaks, a derogatory German expression for Turks) and released his first eponymous German-language album in 1984.

The songs on this album are musically far less ambitious than Karaca’s songs from the 1970s, though they too alternate between rock and folk themes, and between Western and Anatolian music styles. The opening track of the album ‘Mein deutscher Freund’ (My German Friend) is particularly succinct in showing how Turkish guest workers hope to be seen by Germans as more than just cheap labour: ‘Er glaubt so fest daran, oh, so fest daran / Freund ist jeder deutsche Mann’ (He believes so firmly, oh, so firmly / That every German is his friend). But the social barriers remain insurmountable: ‘Gastfreundschaft war zugesagt / Und jetzt heißt es: “Türken raus!”’ (They promised to welcome us / And now it’s: ‘Turks out!’). The song still ends with a euphoric verse promising reconciliation between people of future generations: ‘Da wo jetzt noch Schranken sind / Reißt sie nieder, stampft sie ein’ (Where there are now barriers / Tear them down, stamp on them).

Ozan Ata Canani, born in 1963, was one of Die Kanaken’s musicians. He came to Germany from Turkey in 1975 and taught himself to play the Turkish long-necked lute, the bağlama, while still at school. He performed at Turkish wedding parties and began to compose his own songs, soon also in German. ‘Deutsche Freunde’ (German Friends) is the name of his first German-language song. ‘Arbeitskräfte wurden gerufen / … Aber Menschen sind gekommen’ (Labourers were called for / … but human beings turned up). ‘Deutsche Freunde’ is a song about the fate of the people who eke out an existence in Germany as welders, unskilled workers, and bin collectors, as well as about the fate of their children: ‘Sie sind geteilt in zwei Welten / Ich … frage Euch / Wo wir jetzt hingehören?’ (They are divided into two worlds / I … ask you all / Where do we belong?).

It was already clear to Canani as a teenager that he would spend his life in Germany.Footnote 10 But it was just as clear to him that Germans would like him sent ‘home’, sooner rather than later. His songs about split identities tried to mend this rift through music. But despite his best efforts, success escaped him. Turkish audiences in Germany did not want to hear songs in German; and Germans were not interested in the problems or music of their fellow citizens. The same applied to fans of alternative and countercultures: at the beginning of the 1980s, these groups were open to Afro-American sounds, hip-hop, and Jamaican reggae as well as the emancipatory struggles they reflected. But the music of the large Turkish minority living in their own country was ignored in the same way as everyday racism.

After Cem Karaca went back to Turkey, for a while Canani led the follow-up project, Die Kanaken 2, but again with little success. He finished his musical career in the late 1980s and it took almost three decades before he was rediscovered when he re-recorded ‘Deutsche Freunde’ in 2013 for a compilation with the title Songs of Gastarbeiter. Now he regularly plays concerts with the Munich-based neo-Krautrock band Karaba. In spring 2021, his long-delayed debut album Warte mein Land, warte (Wait, My Country, Wait) was released. He plays his intricate, melodic bağlama over a solid machine-like rhythm section, reminiscent of Can and Neu! No less than forty years after their first performances, the sound of German-Turkish migrants joined that of Krautrock.

Krautrock and the German Nation: Hölderlin, Novalis, Ougenweide, and Achim Reichel

Krautrock is often labelled as iconoclastic, hostile to tradition and trailblazing. Krautrock’s goal to make a decisive break with the tainted musical traditions of post-war West Germany is often described as its most significant political impetus. Holger Czukay of Can put it as follows: ‘In the end, music has only two options: either to outperform music history or to start from scratch. Can decided on the latter.’Footnote 11 But apart from those who sought to break with tradition, various bands also dedicated themselves to cultivating and reappropriating German cultural traditions. German Romantic literature and philosophy played a role, as did medieval poetry; historical and regional forms of German such as Old and Middle High German, as well as Low German and Frisian, were also included.

One of the first acts to be released on the Krautrock label Spiegelei was Hölderlin, named after the poet Friedrich Hölderlin (1770–1843). Initially, the band mainly played cover versions of British folk revival bands like Fairport Convention, Traffic, and Pentangle. On their debut album Hölderlins Traum (Hölderlin’s Dream, 1972), their lyrics were political as well as ecstatically romantic. Later, Hölderlin’s arrangements were more sophisticated and featured extensive organ and guitar solos. The musicians also set texts to music by political writers such as Bertolt Brecht, Erich Fried, and H. C. Artmann. Touring with their third album Rare Birds (1977), singer Christian Noppeney appeared in costume as a giant bird, inspired by Peter Gabriel and the stage shows of early Genesis.

Another German Romantic poet, Georg Philipp Friedrich von Hardenberg (alias Novalis; 1772–1801), lent his pen name to the group Novalis, which formed in Wuppertal in 1971. Their 1973 debut album Banished Bridge, released on the Krautrock label Brain, was an exercise in ‘Romantic rock music’,Footnote 12 as they put it. Novalis dispensed with the electric guitar and opted for expansive organ solos and English lyrics. For their eponymous second LP in 1975, Novalis used German lyrics. They also set poems by their namesake to music, such as ‘Wunderschätze’ (Wondrous Treasures) or ‘Wenn nicht mehr Zahlen und Figuren’ (When Numbers and Figures Are No More) from his unfinished novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen (1802). These poems convey a deeply Romantic mistrust against the rationalisation of the world.Footnote 13 Some centuries after the poet Novalis, the twentieth-century band of the same name belatedly brought hippie mysticism to German rock music. And they did so very successfully: with sales of 300,000 albums, Novalis were one of the most successful West German rock bands of the 1970s.Footnote 14

The formation with the most long-term, decisive impact in the cultivation of German tradition was Ougenweide, founded in 1971 and named after a poem by the Middle High German minstrel Neidhart von Reuenthal (1210–45). In modern German, their name translates as Augenweide (a sight to behold). Using the xylophone, guitars, slide whistle, flute, cymbals, and other rare instruments, they set medieval German poetry to music. Lyrics included, among others, poems by the first great German minstrel from that epoch, Walther von der Vogelweide (ca. 1170–1230) as well as his lesser-known contemporaries like Burkhard von Hohenfels (thirteenth century) or Dietmar von Aist (1115–1171). Ougenweide singers Minne Graw and Renee Kollmorgen chanted German from centuries yore with great vigour. On their second album, All die weil ich mag (All Those Because I Like) from 1974, Ougenweide even set an Old High German poem to music, the ‘Merseburger Zaubersprüche’ (Merseburg Incantations) from the ninth century, probably the oldest surviving literary text in the German language.

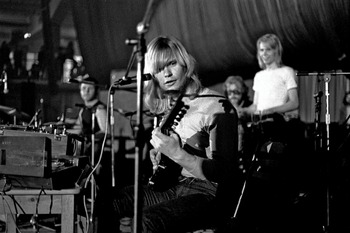

Ougenweide’s producer was the Hamburg musician Achim Reichel; on their debut album, he can also be heard on timpani and bass. Reichel’s career was one of the most interesting at this time because it spanned all areas of German rock music.Footnote 15 In 1961 he was one of the co-founders of The Rattles, the first successful English-language beat band in West Germany. In 1971, under the moniker A.R. & Machines, he released Die grüne Reise (The Green Journey), which consists of looped guitar improvisations recorded on an Akai 330D tape machine, allowing Reichel to create an entire guitar orchestra by himself. He continued to pursue this concept – in parallel to his collaboration with the traditionalists of Ougenweide – until 1976 when his career took another surprising turn.

Illustration 15.2 Achim Reichel (with A.R. & Machines), Hamburg, 1971.

He completely reinvented himself as an interpreter of sea shanties sung in Low German. His debut Dat Shanty Alb’m (The Shanty Album) from 1976 opens with the track ‘Rolling Home’ and features the chorus: ‘Rolling home, rolling home / Rolling home across the sea / Rolling home to di old Hamborg / Rolling home, mien Deern to di!’ (Rolling home to you, old Hamburg / Rolling home, my girl, to you!). Mixing English and Low German, the song tells of a sea journey from Hamburg to a foreign country and the return to the woman who is at home waiting for him. Reichel’s lyrics skilfully exploit the linguistic similarities between Low German and English while the chorus openly alludes to his role models in rock music, The Rolling Stones.

Just as Ougenweide revived obscure forms of German, Reichel rejuvenated Plattdeutsch (Low German), a dialect that had almost completely disappeared in the 1970s. In northern Germany in the 1970s, Low German was widely used by older generations in rural areas; towards the end of the twentieth century, however, it had largely disappeared first from public, then from private use. This trend of decline was a development that equally affected other dialects and minor languages. The gradual disappearance of Low German was also reinforced by the standardisation of language promoted by the media and culture industries, and therefore also by pop culture. For this reason, a recourse to Low German could be seen both as an act of resistance against standardisation and as an attempt by musicians to promote ‘the language of the people’. Reichel attempted to reach an audience who felt disowned both the political music by songwriters of the 1960s and the ‘avant-garde’ sounds of Krautrock.

Achim Reichel singing in Low German was considered by many followers of Krautrock in the 1970s to be a regression to outdated nationalist traditions. In fact, his recourse to a dialect could have been seen as an anti-nationalist reappropriation of a repressed (language) tradition. So his intention was closer to the Krautrockers’ will to radically break with tradition than it might first appear. In the same year as Dat Shanty Alb’m, 1976, the album Leeder vun mien Fresenhof (Songs from My Frisian Farm) by the northern German songwriter Knut Kiesewetter, the former producer of communist songwriter Hannes Wader, was released. It sold over 500,000 copies in a short period, featuring new compositions by Kiesewetter with lyrics in Low German and Frisian.

The opening track is called: ‘Mien Gott, he kann keen Plattdüütsch mehr un he versteiht uns nich’ (Dear God, He Can’t speak Low German Anymore and Doesn’t Understand Us’). The lyrics address a young man who can no longer speak the language of his ancestors and is therefore cut off from his traditional origins. In his song, Kiesewetter laments the young man’s cultural impoverishment and alienation from his rural, peasant, proletarian background: forgetting your own language is tantamount to forgetting your social class.

In the 1980s, lyrics in dialect underwent another astonishing revival. This time, however, the scene was not so much dominated by northern German artists: the Spider Murphy Gang from Munich wrote in Bavarian dialect while BAP from Cologne used local dialect kölsch, which until then had been mainly limited to German carnival songs. Now, it served as a tool for protest songs – for example, ‘Kristallnaach’ (Night of Broken Glass, referring to the anti-Semitic pogrom of November 1938) whose subject was the resurgence of right-wing radicalism in West Germany in the 1980s. The Austrian singer Falco also mixed Austrian dialect with English into a kind of early hip-hop hybrid in hit songs like ‘Der Kommissar’ (1982).

Shanty Bands and Beyond

The interest in German language and tradition found in groups such as Ougenweide, Hölderlin, and Novalis finally waned in the 1980s only to experience a remarkable revival in the 1990s. Following German reunification, a renaissance of political and cultural nationalism took place that led to a flare-up of nationalist violence. Especially in the East German federal states, there were repeated, violent riots against migrant workers as well as arson attacks on homes of asylum seekers. The most successful German rock band of the 1990s, Rammstein, dangerously and irresponsibly toyed with symbols of nationalism and national socialism that attracted attention and provoked outrage.Footnote 16

Such recourse to patriotism and nationalism in German pop culture and politics from the 1990sFootnote 17 also found a less aggressive expression in many groups that emerged in this period. They drew their inspiration, music, lyrics, and instruments, once more, from the Middle Ages, resulting in the genre of medieval metal. Its most important proponents were bands like Corvus Corax, Schandmaul, Subway to Sally, Saltatio Mortis, and In Extremo; the latter explicitly referred in their music to the Krautrock of the 1970s as well as Ougenweide. These neo-medieval rockers combined electric guitars with bagpipes, hurdy-gurdies, harps, shawms, and many other kinds of historic instruments.

The Shanty Album by Achim Reichel, in turn, inspired the most successful northern German rock band of the 2010s: Santiano saw themselves as a ‘shanty rock band’ and posed as weathered mariners at their concerts. Their songs were mostly about seafaring and pirates. They both ironically ruptured tradition and raised it to a new, non-ironic level with their masculinist rock-music performance style. With Santiano, nostalgia for one’s roots merges with a nostalgia for the perceived authenticity of ‘good old rock music’, all in the service of re-enacting a fake past that serves as an escapist fantasy from confusing, globalised culture.

Conclusion

By looking at the ‘flip-side’ of Krautrock, a counter-narrative emerges that puts into question its prevailing status as a modern movement of the 1970s. On the one hand, Krautrock was disconnected from the modernising forces of 1970s West Germany, such as feminism and Germany’s shift towards multiculturalism. On the other, the legacy of the 1970s – one that reaches well into the pop-cultural scene today – springs from music traditions connected to this ‘flip-side’ of Krautrock. And these run counter to its claims of cosmopolitanism, anti-traditionalism, and internationalism. What’s more, due to their immense commercial success, medieval rock and shanty rock were formative for German-language rock music of the 2010s. Albums by the bands mentioned consistently enter number one in the German album charts, although these genres do not feature in music-journalist discourses that critique artistically and/or politically relevant releases. So, the most powerful legacy of 1970s Krautrock is not a forward-looking, cosmopolitan music genre, but rather one that fulfils a nostalgia for old times when life seemed clearer and simpler.

Essential Listening

Ozan Ata Canani, Warte mein Land, warte (Staatsakt, 2021)

Die Dominas, Die Dominas (Fabrikneu, 1981)

Cem Karaca, Die Kanaken (Pläne, 1984)

Knut Kiesewetter, Leeder Vun Mien Fresenhof (Polydor, 1976)

Ougenweide, Ougenweide (Polydor, 1973)