1. Introduction

Lexicalization patterns in verbs vary widely across languages since verbs are free to encode different aspects of an event in their semantics (Gentner Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982, Talmy Reference Talmy and Shopen1985, Gentner & Boroditsky Reference Gentner, Boroditsky, Bowerman and Levinson2001, Evans Reference Evans and Thieberger2011). While nouns are often claimed to be ‘given’ by the world in the sense that they represent stable and ‘cohesive collections of perceptual information’, verbs carry complex relational meanings that can be construed in a multitude of different ways (Gentner Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982: 46; see also Thompson, Roberts & Lupyan Reference Thompson, Roberts and Lupyan2020). Thus, for instance verbs of motion – aside from the fact of motion – can lexicalize a number of distinct components of the motion event, e.g. path, manner, figure (moving entity), and ground (reference entity) (Talmy Reference Talmy2000a). Verbs of physical separation, i.e. cutting and breaking, can encode manner, instrument, or type of separation (Majid et al. Reference Majid, Bowerman, Staden and Boster2007, Majid, Boster & Bowerman Reference Majid, Boster and Bowerman2008). Verbs of ingestion, in turn, may code for the type of ingested matter, manner of ingestion, but also speed and intensity, or the consumed quantity (Newman Reference Newman and Newman2009, Burenhult & Kruspe Reference Burenhult, Kruspe and Endicott2016, Wnuk Reference Wnuk, Papafragou, Grodner, Mirman and Trueswell2016b). In domain after domain, denotations of verbs show cross-linguistic variability and malleability of the underlying concepts. Still, despite the considerable variation, the packaging of meaning in verbs is not random as there are a number of factors which contribute to shaping the lexical verb categories (Malt & Majid Reference Malt and Majid2013).

One such factor is related to the recurrent patterns of lexicalization exhibited by specific languages. For instance, in default descriptions of motion events, languages tend to use main verbs lexicalizing either path of motion (as in Spanish bajar ‘to descend’) or manner of motion (as in English roll). They were classified into verb-framed (i.e. bajar-type) and satellite-framed (roll-type) languages (Talmy Reference Talmy and Shopen1985, Reference Talmy2000a) on this basis, although these two patterns may be reversed in some contexts and do not exhaustively represent the typological picture. A third type – equipollently-framed languages – has since been distinguished and refinements have been proposed to accommodate the fact that languages can exhibit mixed patterns of motion event expression (Slobin & Hoiting Reference Slobin and Hoiting1994, Slobin Reference Slobin, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004, Zlatev & Yangklang Reference Zlatev, Yangklang, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004, Levinson & Wilkins Reference Levinson and Wilkins2006, Beavers, Levin & Tham Reference Beavers, Levin and Tham2010, Selimis & Katis Reference Selimis and Katis2010).

While the typology of motion verbs distinguishes a verb-framed pattern and a satellite-framed pattern, each found in a sizeable sample of languages from across the world, the picture seems to be different in the domain of visual perception. Here, the path of looking, i.e. gaze trajectory, is expressed externally to the main verb in both satellite-framed languages, e.g. English – look up and Polish – patrzeć w górę ‘look-in-up’, and those that otherwise favour verb-framing, e.g. Spanish – mirar para arriba ‘look-toward-up’ and Turkish – yukarı bakmak ‘upwards-look’. Slobin (Reference Slobin and Mueller-Gathercole2009: 205) suggests that ‘verb-framed languages do not provide specialized verbs for visual paths, on a par with “enter”, “ascend”, and the like; rather, both types of languages rely on all-purpose perception verbs such as “look,” combined with various sorts of adjuncts’. Matsumoto (Reference Matsumoto2001) found the same pattern in a typologically diverse sample of languages (verb-framed, satellite-framed, equipollenty-framed): English, Spanish, Hindi, Japanese, Korean, and Thai, and referred to this situation as a ‘typological split’.

The ‘typological split’ has been observed in the better-known verb-framed languages, but – as will be shown here – it does not represent a universal lexicalization constraint. Mentions of verbs of looking encoding trajectory of gaze (i.e. visual path) appear in the literature (Klein Reference Klein1981, Evans & Wilkins Reference Evans and Wilkins2000), but the pattern appears to be typologically rare and, as of yet, it has not received systematic treatment. This article contains the first detailed documentation of the semantics of such verbs, making a descriptive and typological contribution to the verbs of perception literature. The central phenomenon examined here are the verbs of looking which encode visual path in Maniq (Austroasiatic, Thailand). Consider the following two spontaneous descriptions of looking events, illustrating the use of an upward-directed looking verb balay, seen in (1), and a downward-directed yɔp, seen in (2):

Both balay and yɔp have specific meanings and – in addition to lexicalizing the looking activity itself – carry information about the trajectory of looking. Such meaning specialization is in line with Maniq’s general typological profile of a language with a semantically specific verb lexicon and a consistent preference for verbal encoding of information across a number of lexical fields such as motion, ingestion, transportation, and many others (Wnuk Reference Wnuk2016a, b). In many cases, the shape of the lexicon can be shown to be linked to cultural preoccupations and indigenous expert knowledge. The question here is whether a similar culture–language link might exist for verbs of looking. What pressures are shaping this vocabulary? And, related to that, what could be the possible communicative advantages of encoding path in verbs?

Following earlier explorations (e.g. Slobin Reference Slobin and Mueller-Gathercole2009, Cifuentes-Férez Reference Cifuentes-Férez2014), the present discussion of visual perception draws parallels to the domain of motion. Visual perception and motion have been noted to display a number of similarities. In Talmy’s terms, visual perception is an example of fictive motion – ‘motion with no physical occurrence’ (2000b: 99; see also Matlock & Bergmann Reference Matlock, Bergmann, Dąbrowska and Divjak2019), more specifically categorized as emanation, i.e. ‘fictive motion of something intangible emerging from a source’ (2000b: 105).Footnote 2 The conceptualization involves an agent who ‘volitionally projects his line of sight’ (Talmy Reference Talmy2000b: 116) and is an active perceptual act (an activity-type predicate; Viberg Reference Viberg1984), rather than a passive experience. The observation regarding similarity of vision and motion rests on linguistic evidence showing motion and vision enter similar syntactic frames and occur with the same spatial expressions such as to and from (Gruber Reference Gruber1967, Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1983, Slobin Reference Slobin and Mueller-Gathercole2009, Gisborne Reference Gisborne2010). Evidence for the fictive motion conceptualization of vision is found in numerous languages across the world and has been proposed to be universal (Slobin Reference Slobin and Mueller-Gathercole2009: 199).

While visual perception and motion display similarities, they are also clearly different from each other. Slobin (Reference Slobin and Mueller-Gathercole2009: 204–205) makes the following observation:

An act of looking doesn’t bring about a change of locative state of the fictive agent or of the gaze as an extended entity. That is (at least from the point of view of an English speaker), when I look into another room, my gaze is still anchored at my eyes, and has not left me and achieved a new state of containment on the other side of the threshold. But if my dog goes into that room, he is no longer here at my side, but there, having crossed the boundary. That is, boundary-crossing is a change of state event for physical motion, but not for visual motion.

Such fundamental differences between visual perception and motion could well result in different sets of constraints shaping the lexical categories across these domains, and ultimately help account for why visual paths in many verb-framed languages are resistant to verbal encoding. Maniq does lexicalize path information in verb roots in both verbs of motion and visual perception. However, the question remains whether the distinctive nature of the two types of events results in specific differences as to the types of lexicalized paths. What paths do verbs of motion and verbs of vision encode?

To address the above points, this paper explores in detail the expression of visual paths in Maniq and the extent of their parallelism to motion paths. To prepare the ground for comparison, I introduce Maniq and its speakers (Section 2) and provide a brief outline of the domain of motion event descriptions outlining basic facts about the expression of spatial relations in Maniq (Section 3). Following that, I introduce the central part of the present investigation – the verbal encoding of visual paths, explored by means of a translation questionnaire (Section 4.1) and a picture-naming task (Section 4.2). These two tasks probe the distinctions of potential relevance to the domain of visual perception and bring out the semantic subtleties of the featured verbs. This information – contextualized within the local ecological and cultural setting – sheds light onto the organizing principles of the visual perception lexicon and the communicative utility of encoding path in verbs. The final sections contain a comparison of paths encoded in verbs of motion and verbs of vision (Section 5). The data show there is a core set of spatial distinctions lexicalized across the two verbal lexical sets. A broader look across the Maniq lexicon reveals parallel cases of such encoding (Section 6), thus demonstrating a pervasive systematicity in the packaging of meaning in verbs.

2. The Maniq language background

Maniq (also known as Ten’en, Tonga or Mos; ISO: tnz) is a Northern Aslian language from the Aslian branch of the Austroasiatic family. It is spoken in Southern Thailand by approximately 300 people, most of whom live in small nomadic groups scattered across four provinces in the Banthad mountains (Wnuk Reference Wnuk2016a). Maniq displays complex morphological processes such as combined reduplication and affixation. The default constituent order is SVO, with frequent argument ellipsis. Among its most characteristic features is a strong preference for encoding semantically specific information in monomorphemic verbs, a feature shared with other Aslian languages spoken to the south. Maniq can also be described as a ‘verby’ language, due to an almost equal one-to-one noun-to-verb ratio in the lexicon, and a prominent position of verbs in discourse (Wnuk Reference Wnuk2016a).

The research reported here is based on first-hand fieldwork carried out by the author with a nomadic group of Maniq speakers in the Manang district, Satun province (Thailand). The translation questionnaire task was conducted in August 2012 and the picture-naming task in February 2014.

3. Semantics of motion verbs in Maniq

Maniq has a wide repertoire of motion verbs (as do other Aslian languages, e.g. Burenhult Reference Burenhult2008, Kruspe Reference Kruspe2010). This section focuses on a general delineation of the distinctions lexicalized in motion verbs. In particular, it provides an inventory of the commonly encoded semantic components of motion events and lists the types of motion paths encoded in verbs. The data presented here are based on non-elicited use as well as stimulus-based elicitation with ‘Motion verb stimulus’ clips (Levinson Reference Levinson, Levinson and Enfield2001).

Based on the criterion of path encoding, Maniq can be classified as a verb-framed language, since it lexicalizes path of motion in independent verbs (Talmy Reference Talmy1991). Consider examples (3) and (4) below with monomorphemic path-encoding verbs cɛn ‘to move along the top of an object’, ciday ‘to move uphill’ and sa ‘to descend’.

Manner information is frequently omitted in descriptions of these kinds, as is typical of verb-framed languages. When mentioned, manner is most typically lexicalized in independent verbs, occurring either in separate clauses or within multi-verb constructions (with the manner verb following the path verb, as in (5), or preceding it).

This example suggests Maniq could be classified as a ‘complex verb-framed language’ (otherwise called equipollently-framed), characterized by the encoding of path and manner in two grammatically equivalent verbs (Slobin & Hoiting Reference Slobin and Hoiting1994, Slobin Reference Slobin, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004). However, a systematic investigation of motion events is needed to identify the predominant patterns and provide a nuanced typological characterization (see Slobin Reference Slobin, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004, Levinson & Wilkins Reference Levinson and Wilkins2006). The relevant fact for now is that path of motion is routinely lexicalized in verbs.

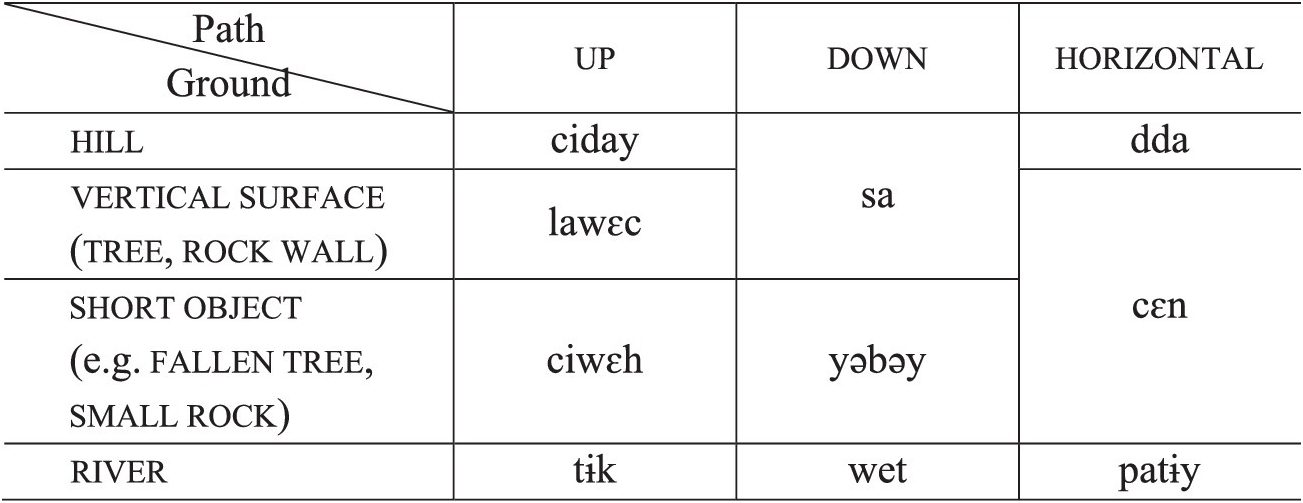

Aside from path and the fact of motion itself, some of the basic motion verbs in Maniq also lexicalize the component of ground (e.g. Jahai; Burenhult Reference Burenhult2008), e.g. wet ‘to move downstream’. Such verbs are among the most semantically heavy items in the lexicon carrying multiple semantic components. Table 1 shows the motion verbs applying to different types of path and ground. All listed verbs lexicalize change of location, and none encode manner.

Table 1 Motion verbs for various types of ground and path.

Note that among the categories in the table, some verbs lexicalize a specific type of ground (e.g. wet ‘to move downriver’), while others are more general (e.g. sa ‘to descend (general)’). Depending on the type of ground, the ‘horizontal’ category corresponds to across, e.g. patɨy ‘to go across a river’, or along, e.g. cɛn ‘to move along the top of an object’. In addition to the distinctions given in the table, some categories, notably the arboreal motion verbs, also lexicalize manner, e.g. tanbɔn ‘to climb a tree with a “walking” style’.Footnote 3

Aside from up, down and across/along, the following object-anchored paths have been found to be encoded in verbs:

The list is most likely not exhaustive since the domain of motion has not been fully explored, but irrespective of the actual number of existing verbs, the crucial observation is that object-anchored paths of motion are frequently lexicalized in verb roots.

Beyond verbs of motion, spatial figure–ground relations can also be expressed in other types of verbs, e.g. verbs of stative location expressing ‘place’ (see Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Cinque and Rizzi2010) such as tul ‘to be inside a contained space’. Spatial relations are further coded in locative prepositions expressing source (nataŋ ‘from’) and location/goal (daʔ/kiʔ ‘on, in, at’, nɨŋ ‘in, on’), as well as in relational nouns (e.g. kapin ‘upper side’, kayɔm ‘lower side’, kaʔɔʔ ‘back’) (Kruspe, Burenhult & Wnuk Reference Kruspe, Burenhult, Wnuk, Sidwell and Jenny2015, Wnuk Reference Wnuk2016a). These elements combine within clauses in multiple ways. Relational nouns may occur on their own or with an optional preposition, e.g. (daʔ) kapin ‘on top’ (on upper.side). Similarly, verbs encoding spatial relations may be used on their own or with optional prepositions/relational nouns, e.g. ʔanciʔ ʔɛʔ tul (nɨŋ) cɔ̃ŋ ‘tubers are in the basket’ (tuber 3 be.inside (in) basket). Finally, in some cases it is also possible to leave the central spatial relation to be inferred from context, e.g. ʔɛʔ cɨh hɔʔ mahɨm ‘it’s (in) the coconut shell, the blood’ (3 be.placed shell blood).

4. Semantics of Maniq verbs of looking

Having outlined the general distinctions relevant for the motion domain and the ways of expressing spatial relations in Maniq, I now turn to the domain of vision. Of major interest to this investigation is the question of path-encoding. What path distinctions are encoded in verbs of looking? And how do verbs of looking compare to verbs of motion and verbs in other semantic fields?

In order to survey the visual perception domain, two tasks were carried out with Maniq speakers: a translation questionnaire and picture naming. The translation questionnaire provided a first general indication of the available distinctions lexicalized in verbs of looking. Picture naming explored them further by establishing the exact extensional range of the verbs and testing which spatial frames of reference they are associated with.

4.1 Study 1: Translation questionnaire

4.1.1 Method

The initial probing of the distinctions encoded in verbs of looking was carried out with the use of a translation questionnaire. Two male speakers of Maniq aged approximatelyFootnote 4 35 and 45 took part in the task.

The questionnaire was composed of 59 sentences in Thai containing simple descriptions of looking events. The sentences examined a broad selection of visual paths as judged by gaze direction.

It included paths which are known to be relevant for verbs of motion (Section 3), as well as several other paths expressing spatial distinctions of high salience in the Maniq community (e.g. east, west). Note that some spatial distinctions are ambiguous with respect to the spatial coordinate system (‘frame of reference’) they typically associate with (i.e. egocentric vs. absolute). This could not be explored systematically in this task, but the issue is treated more extensively in Section 4.2. Example sentences are provided in (7). The full questionnaire (in English and Thai) is included in Appendix A.

In addition to the selected types of paths, the stimulus set varied parameters such as the type of ground object (e.g. tree, stream), the type of viewed object, i.e. endpoint of visual path (e.g. person, animal, thing), identity of the experiencer (human, animal), position of the body (e.g. standing, sitting, lying), and position of the eyes (neutral, up, down, sideways). The purpose of this broad selection of stimuli was to identify the relevant parameters lexicalized in the Maniq verbs of looking and to eliminate irrelevant ones.

The first half of the questionnaire was administered to both participants interviewed together in a single session. The second half was administered on another day to the older participant (due to the unavailability of the younger participant). The focus of the elicitation was not an exact translation of the entire scenario described in the sentence, but only of the target descriptions of looking events and visual paths. In addition to providing translations, the participants answered questions and judged the acceptability of alternative descriptions provided by the researcher. This information was used as additional evidence supplementing the results from translation. The Thai sentences were read out by a native speaker of Southern Thai, while the additional probing was carried out in Maniq by the researcher. The section below contains a summary report of the main results.

4.1.2 Results

The translations yielded a total of eight verbs used as independent descriptors of the looking actions, as illustrated in (8).

Seven of them encoded specific horizontal and vertical gaze directions, and one – dɛŋ – was a direction-neutral general looking verb. All listed verbs are monomorphemic, except for wwɛ, which contains an imperfective affix. In addition, ciyɛ̃k and cikiey – though synchronically non-analyzable – appear to share a fossilized prefix *c- and the causative infix <i>.

The elicitation revealed further that distinctions such as absolute directions (east-west), type of ground (e.g. tree, stream), and type of viewed object (e.g. liquid-solid) were not lexicalized in verb roots but were expressed by other lexical means. Object-anchored paths (e.g. to look under something) were also not associated with dedicated verbs but were either unexpressed or expressed periphrastically. The identity of the experiencer was not lexicalized in the verb. There were some indications that parameters such as body posture and position of the eyes had a meaningful influence on the verb choice, but – given that no clear generalizations emerge – the issue was explored further in the picture-naming task.

There is no evidence to suggest responses may have been influenced by the way looking events are expressed in Thai. Most of the looking event descriptions in Thai were made up of the general looking verb mong ‘to look’ followed by one of the path-encoding elements such as a motion verb (e.g. khâo ‘to enter’), a preposition (e.g. tâi ‘under’), or an adverb (e.g. khâng lâng ‘below, down’). There were no word-for-word translations or consistent correspondences between Thai and Maniq, suggesting the Thai patterns did not shape the responses provided.

The most semantically general looking verb was dɛŋ. Rather than being associated with one specific type of path, it was employed with a variety of paths. Dɛŋ was in most cases attested in a bare root form, as in (9). Translated sentences from Appendix A are referenced by numbers in parentheses.

Only in one case, did it surface in the imperfective form dŋdɛŋ. The imperfective – signalling the ongoingness of the action – was used to express ‘looking around’, see (10).

Balay was used to express looking up. It was attested both with simple up paths as in (11),Footnote 5 as well as complex ones, e.g. up into, and with paths with a specific ground such as uphill.

Another verb expressing the meaning of looking up was pəntɛw. Example (12) was elicited with a sentence involving a woman looking out from a house.

In this case, the participants presupposed the house was on a slope and explicitly stated pəntɛw would be appropriate if the woman was looking upwards (while looking downwards would require the verb yɔp, see below). Pəntɛw refers to looking up, but it seems to differ from balay since the two verbs occurred in different contexts. This difference is examined further in the picture-naming task (Section 4.2). Additional probing revealed pəntɛw is also associated with looking straight ahead. This suggests the verb covers a range of gaze directions encompassing straight level and upward paths.

The verbs ciyɛ̃k and cikiey were both employed to express looking sideways, e.g. ciyɛ̃k in (13).

Cikiey was additionally employed with back, as in (14).

Two other verbs – wwɛ and pədɛp – seen in (15) and (16), respectively, were used to express looking around.

Wwɛ – like dŋdɛŋ mentioned above – is an imperfective form (derived from wɛ ‘to walk around looking for food’) and indicates an ongoing looking activity. Pədɛp also expresses the activity of looking around, but it additionally denotes a manner of looking involving sudden jerky movements characteristic of birds.

Yɔp was used to express looking down. It was employed in translations of sentences explicitly specifying a downward gaze trajectory, as well as those where it was presupposed based on sentential context, e.g. looking into a basket, as in (17), or under a bed.

To summarize, ‘looking’ was translated into a number of specific verbs encoding visual path and – in a few cases – other semantic detail. This preliminary evidence suggests these verbs mark directions such as up, up/straight, sideways/back, and around without accompanying spatial expressions external to the verb. The path distinctions identified in the core set of verbs are explored further in a systematic investigation carried out with a picture-naming task.

4.2 Study 2: A picture-naming task

Picture naming involved descriptions of a selection of looking scenes. It focused on distinctions which were difficult to test with verbal stimuli, but were relatively easy to depict using visual representations, e.g. small variation in angle of gaze, presence/absence of an endpoint object, varying body posture, and position of the eyes. This was done to establish the exact extensional range of the verbs and identify their distinctive features (especially since some of them seemed to overlap in denotation, e.g. balay and pəntɛw). In addition, this task set out to determine what spatial coordinate systems (‘frames of reference’) the looking verbs are associated with. The translation task revealed that, for instance, yɔp refers to looking down and cikiey to looking sideways, but it is unclear whether these directions are determined with respect to the viewer’s body or the environment. Since the issue of frames of reference is of importance to this task, the following section introduces it briefly, situating it in the context of looking events.

4.2.1 Frames of reference in looking events

Frames of reference are coordinate systems applied for computing spatial relationships between objects (Levinson Reference Levinson2003, Majid et al. Reference Majid, Bowerman, Kita, Daniel and Levinson2004). In the context of looking events, different frames of reference are associated with different ways of determining the trajectory of gaze. Two types of frames of reference will be relevant to the ensuing discussion: egocentric (or viewer-centered) and absolute (or environment-centered) (see Carlson-Radvansky & Irwin Reference Carlson-Radvansky and Irwin1993).Footnote 6 The egocentric frame is viewer-centered, i.e. the defining relation is based on the alignment of viewer’s bodily axes with respect to one another. The relation which will be critical here is the angle between the head and the spine resulting from head rotation (turning), and head flexion (bowing). An additional parameter of relevance is the position of the eyes with respect to the face. The absolute frame, in contrast, is environment-centered, i.e. the defining relation is specified by the angle between gaze direction and the absolute vertical axis, determined by gravity and salient environmental features. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the distinction.

Figure 1 The egocentric frame: body axes.

Figure 2 The absolute frame: gaze direction and absolute axes.

Normally, bodily and absolute axes align. So, in canonical instances of various looking acts, there is no need to pick between frames of reference in order to select which verb to use. However, in non-canonical cases – where bodily and absolute axes do not align, e.g. when lying down – the speaker is forced to assume either an egocentric or absolute perspective, as either choice will require the use of a different verb. Misalignment of frames of reference is a common problem in spatial language, since languages typically do not have dedicated strategies for non-canonical cases. For instance, the English preposition above is applied with the absolute or intrinsic (i.e. object-centered) frame of reference, depending on which perceptual cues are used to define the vertical axis (Levelt Reference Levelt, Van Doorn, Van de Grind and Koenderink1984, Carlson-Radvansky & Irwin Reference Carlson-Radvansky and Irwin1993). The picture-naming task tackles this problem directly by introducing experimental manipulations teasing apart egocentric and absolute frames via non-canonical body postures accompanying looking scenes.

4.2.2 Method

Eight participants (four male, four female) in the approximate age range of 27–65 years took part in the picture-naming task. All were native speakers of Maniq. The stimuli were 54 photographs: 50 looking scenes and four closed-eyes scenes (see examples in Figure 3 and the full set of photographs in Appendix B). Because the closed-eyes scenes were added later, they were administered with only four of the eight participants. The remaining 50 scenes were described by all eight participants. Each looking scene involved one person (either male or female) looking in a particular direction. Most photographs were taken indoors against a neutral background to maximize the focus on the looking act and discourage inferential descriptions such as ‘He is searching for animal tracks’.

Figure 3 Example images from the picture-naming task. A: #1 up-non-sharp, B: #11 out-of-room, C: #3 back-and-up-via-right.

The stimuli explored the following four types of visual paths as judged by gaze direction:

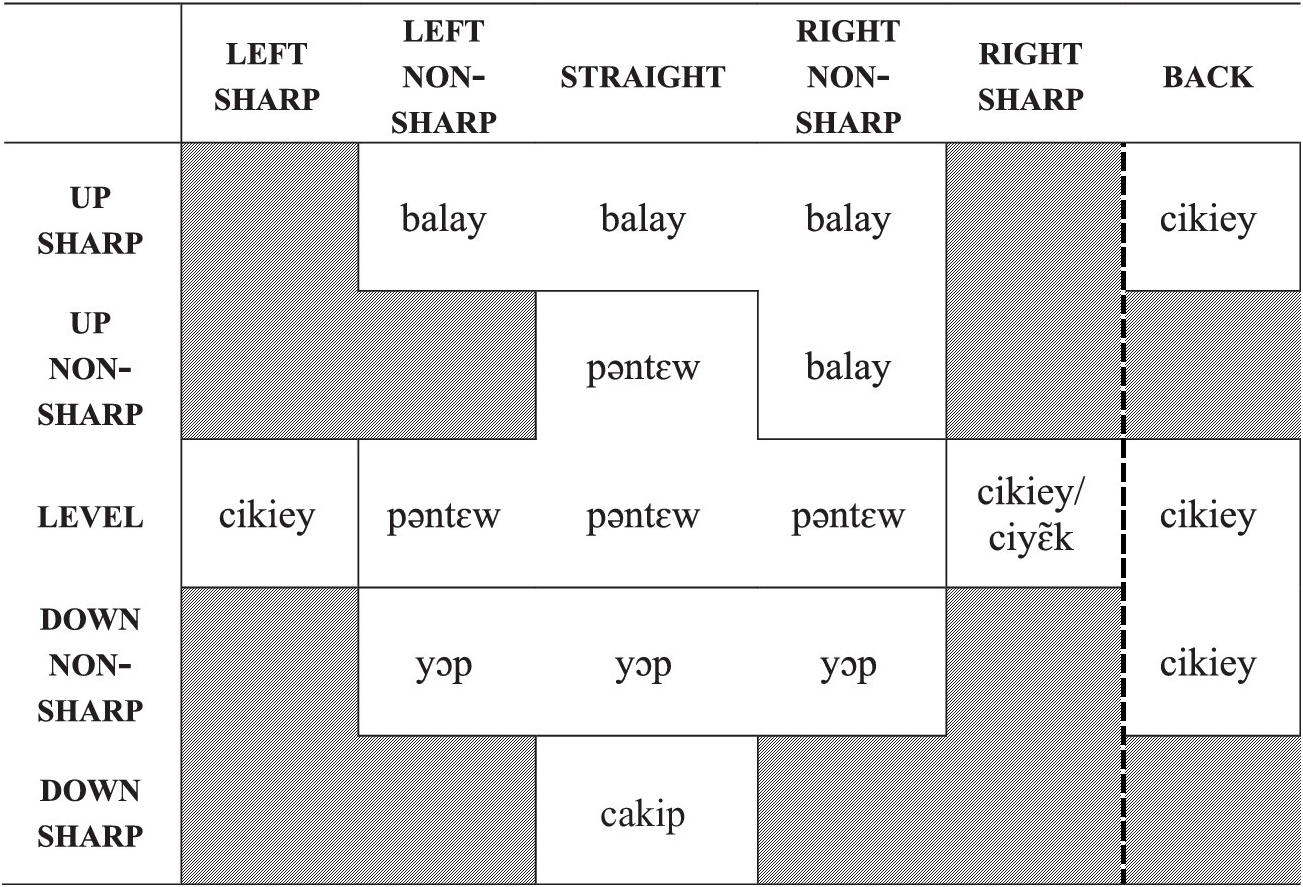

Table 2 presents a visual summary of the combinations of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal paths targeted in the stimuli (the grayed-out area).

Table 2 Horizontal, vertical, and diagonal paths targeted in the stimuli indicated by the dark grayed-out area. Paths marked by stripes were not included; the vertical dashed line separates backward from the remaining looking directions and includes both BACK-via-RIGHT and BACK-via-LEFT paths. ■■■■.

To address the issue of frames of reference, the scenes also varied parameters such as position of the body (e.g. standing, lying on belly/back/side, leaning) and position of the eyes (neutral, up, down, right, left). An additional manipulation consisted of scenes with and without physical endpoints. This was done to examine whether presence of endpoints influenced the choice of verb and if the relevant verbs could surface with direct objects. Some scenes additionally varied type of ground object (e.g. stairs, mound, tree), since some grounds are culturally more salient and might be associated with special strategies. Finally, to probe the scope of the verbs, sharp (~90ᵒ) and non-sharp (~45ᵒ) angle variants of left, right, down and up were included. For practical reasons to keep the stimulus set to a manageable size, only some combinations of these parameters were included (for the full list of stimuli, see Appendix B).

Participants saw photographs one by one in a fixed random order on a 14-inch laptop. The task was to answer the question ʔɛʔ diʔ kaləw ‘What is he/she doing?’ (3 do what) for each image. The length of the response was not restricted so speakers were free to use as many verbs as they wished in their descriptions. If no reference to the looking act was made, the researcher provided descriptions for judgment or asked additional questions. The prompted answers were not included in the main count, but were occasionally used as auxiliary evidence to support the analysis. The whole procedure was carried out in Maniq.

In addition to the picture-naming task, the Maniq verbs of looking were explored by having a few speakers enact them. These re-enactments were done informally on a separate occasion, both by speakers who participated in picture naming as well as those who didn’t. Speakers were asked to enact situations using a simple instruction consisting of a verb in an imperative frame mɔh x, e.g. mɔh balay ‘look up’ (2S look.up), or using the phrase mɔh pi-dɛŋ x, e.g. mɔh pi-dɛŋ balay ‘show look up’ (2S caus-see look.up). Insights from the re-enactments were used as supporting evidence for the interpretation of the results presented below.

4.2.3 Results

The stimuli successfully elicited descriptions of the looking acts from the majority of participants. The provided descriptions were generally short, often consisting of a single clause or several clauses (maximally five). Example responses are given in (18) and (19). Stimuli, referenced by numbers preceded by a hashtag, can be viewed in Appendix B.

Most clauses were brief and typically consisted only of the subject and predicate. Subjects were occasionally omitted, in which case the description was minimal, i.e. consisting of the predicate only. Predicates were either simple and formed by single verbs, or complex and formed by multi-verb constructions, e.g. tmiʔpaʔ mpyɔp in (19). Most verbs were derived with the progressive morpheme (and sometimes also the imperfective), suggesting the looking events were encoded as ongoing (see Wnuk Reference Wnuk2016a).

As in the translation task, in most looking scene descriptions the information about the visual path was encoded solely in verbs. The verb was sometimes accompanied by overt expressions of visual path or goal. These included:

-

i. directional PPs (present in 11% of descriptions), e.g. hwaŋ hayɔl ‘straight ahead’ (towards be.straight)

-

ii. overt nominal locations (present in 12% of descriptions), introduced as PPs in case of relational nouns, e.g. daʔ kayɔm ‘down’ (loc upper.side), and as bare nouns, e.g. ɲahuʔ ‘at the tree’ (tree), or PPs, e.g. nɨŋ hayãʔ ‘in the house’ (in/on house), in case of ordinary nouns, the two options occurring in free variation

-

iii. deictic PPs (present in 7% of descriptions), e.g. daʔ ʔɛn ‘here’ (loc dem.here), daʔ ʔum ‘there’ (loc dem.there)

The majority of the descriptions, however, did not contain overt path or goal expressions. Crucially, the directional verbs of visual perception occurred predominantly without such expressions, consistent with the idea that the path was already encoded in the verb roots. For instance, the verb yɔp, glossed as ‘to look down’, was employed 85 times in total, and only seven times with the locative PP daʔ kayɔm ‘down’, as in (20).

Since daʔ kayɔm ‘down’ expresses the visual goal, already implicit in the path-encoding verb yɔp ‘to look down’, yɔp daʔ kayɔm might be thought of as a pleonastic expression, similar to the motion expressions subir arriba ‘ascend up’ and salir afuera ‘exit out’ described for Spanish (González Fernández Reference Fernández and Jesús1997) or bike mesa ‘she/he entered inside’ for Greek (Selimis & Katis Reference Selimis and Katis2010). The function of directionals in the Spanish case is associated with discourse prominence. Given that in the present data set the phenomenon is rare and not clearly linked with particular scenes, I will not pursue the issue further.

Instead, I turn to the main focus of the task – the path distinctions lexicalized in the verbs. In order to begin to explore them, verb frequency per stimulus was calculated. It was then possible to identify the verbs used most frequently with each scene. Most of the verbs employed in this task were the same as in the translation questionnaire, supporting the validity of the translation questionnaire as a means of identifying the relevant verbs. Only wwe ‘to look around’ and pədɛp ‘to look around jerkily’ from the previous task were not elicited in this task as these actions would require dynamic stimuli. Eight verbs were identified as relevant to the target event, of which six were looking verbs. In addition, four verbs referred to other events which are not directly relevant here, and therefore excluded from further discussion: həɲyaɲ ‘to stand’, tapaʔ ‘to lie on belly’, tiek ‘to lie on back’, and cep ‘to touch/grasp with hand’. Table 3 lists the relevant eight verbs together with glosses, the list of scenes for which they were the dominant response, and the level of participant agreement (the percentage of participants who used the verb with a given scene).Footnote 7

Table 3 Verbs describing looking acts employed as dominant responses.

Most scenes were associated with a single dominant response. The exceptions were scenes #4, #5, #8, #21, #23, #27, and #51, where two or three dominant responses were used an equal number of times. These scenes are listed several times, separately for each relevant verb. The discussion is divided into two sections: ‘Visual perception verbs’ and ‘Other verbs’.

Before proceeding, several general points on visual paths are in order. Although similar to paths of motion in some respects, paths of vision have certain fixed properties determined by the nature of visual perception events. All paths of vision presuppose a perceiver, a point which constitutes the origin of the visual path. Hence, all verbs of vision lexicalize a deictic center, akin to the reference object lexicalized in the directed motion verb go (see Rappaport Hovav Reference Hovav, Malka, Alexiadou, Borer and Schäfer2014). The fictive motion entailed is thus always directed away from the perceiver. Other elements of the path – discussed below separately for each verb – are determined by sentential complements or are recoverable from context.

4.2.3.1 Visual perception verbs

4.2.3.1.1 Dɛŋ ‘to look at, to see’

The verb dɛŋ is a direction-neutral gaze descriptor, as indicated by the fact it was employed with all sampled gaze directions. It was the most frequent verb in the task, used at least once with 47 of the 54 scenes. Dɛŋ is associated primarily with looking at particular objects and featured most often with object-anchored paths: up-into-bag (#32; Figure 4B), down-into-bag (#35; Figure 4C), level-into-bag (#40), at-fingernails (#2; Figure 4A), at-paper (#28). It presupposes a path with an endpoint, though the endpoint itself need not be explicitly mentioned. In this sense, dɛŋ differs from most other verbs featured in the task, which place emphasis on the path itself and lack inherent endpoints.

Figure 4 Scenes described predominantly with the verb dɛŋ. A: #2 at-fingernails, B: #32 up-into-bag, C: #35 down-into-bag.

Note that images similar to those in Figure 4, but without specific physical objects as visual goals, elicited the direction-encoding verbs pəntɛw, yɔp and balay. When visual goals were present, most participants did not encode direction, but focused on the endpoint by employing dɛŋ, suggesting visual perception events might be exhibiting a goal bias similar to the one observed for motion events (see Stefanowitsch & Rohde Reference Stefanowitsch, Rohde, Panther and Radden2004).

Dɛŋ covered both at- and into-type paths without making a distinction between the two. No special expressions were used to mark the crossed boundaryFootnote 8 of into in the two looking-into-bag scenes, consistent with Slobin’s (2009) observation that boundary-crossing in visual perception is not a change-of-state event and – unlike in motion in verb-framed languages – it does not necessitate expression by a separate verb. The endpoint physical objects in both at and into scenes surfaced as direct objects in the sentences.

4.2.3.1.2 Pəntɛw ‘to look ahead (for a general scene overview)’

The verb pəntɛw is associated with looking ahead for a general overview of the scene in front. It is linked to neutral gaze directions (#38; Figure 5A) and incorporates also non-sharp upward (#1; Figure 5B) and sideways angles. Pəntɛw can also be used with looking down from an elevated point such as stairs or mound, but not with the ordinary down scenes, consistent with the idea that it applies with looks aimed at getting a general scene overview. Pəntɛw was attested in scenes with various body-to-head angles (as in #38, #1, and #20; Figure 5A–C), which indicates the up–down gaze orientation is determined with respect to the absolute frame. However, it is also partially dependent on the egocentric frame since it encompasses an area in front projected from the body.

Figure 5 Scenes described predominantly with the verb pəntɛw. A: #38 level_and_straight, B: #1 up-non-sharp, C: #20 up_lying_on_belly.

Looking straight ahead is in a sense neutral, but the delimited distribution of pəntɛw shows the verb is not insensitive to direction like the generic verb dɛŋ, which was used with almost all stimuli. In addition, during the extra probing with task participants (P), pəntɛw was used several times as a self-contained answer to the experimenter’s (E’s) question Where is he looking?, demonstrating sensitivity to a specific gaze trajectory, as seen in (21).

4.2.3.1.3 Cikiey ‘to turn one’s head sideways/back, to look sideways/back’

The verb cikiey is associated with the egocentrically-defined sideways and backwards gaze directions. It was employed to describe the simple sideways/back gaze paths – e.g. the scenes left_sharp (#26; Figure 6A) and back_via_right (#13) – as well as some diagonal paths – e.g. back_and_down_via_right (#46; Figure 6B). Note that back here entails turning the head and twisting the trunk, rather than turning the whole body together with the feet. The verb was not employed with a scene involving looking sideways by moving the eyes only, which suggests the rotated position of the head is a crucial aspect of cikiey.

Figure 6 Scenes described predominantly with the verb cikiey. A: #26 left_sharp, B: #46 back_and_down_via_right.

The image with a sharply turned head and closed eyes (#53) was also described as cikiey, suggesting it might be acceptable to use the verb to refer to posture alone. This stimulus, however, might be depicting a somewhat unnatural situation, so this result should be interpreted with caution (participants may have, for instance, assumed the person was in fact gazing, but the photograph was taken during a blink).

Canonical examples of cikiey, as enacted by Maniq speakers, involve both head rotation and gaze (as in Figure 6A). Gazing is thus presupposed for cikiey. Note also that cikiey can take visual goals as direct objects, e.g. cikiey ɡanaʔ ‘looking back at companions’ (look.back companion) in example (14) attested in the translation task. Finally, cikiey can also occur in a special format, with the noun mɛt ‘eyes’ in the direct object position, to place additional emphasis on gaze, as in (22).

A similar format with the noun hoh ‘neck’ in (23) is available for placing emphasis on the head turn.

4.2.3.1.4 Ciyɛ̃k ‘to look sideways, to move one’s eyes to the side’

The verb ciyɛ̃k is associated with a sideways gaze direction. It was the dominant response for only one scene – looking right by moving the eyes to the side (#6; Figure 7).

Figure 7 The scene described predominantly with the verb ciyɛ̃k: #6 right_just_eyes.

The verb refers specifically to the movement of the eyes and their resultant position. This is especially apparent when it surfaces in the form calyɛ̃k (attested on a separate occasion in the phrase mɛt calyɛ̃k ‘eyes looking sideways’ (eyes look.sideways.mult)). This form contains a multiplicity infix l, encoding distribution of the action over multiple entities (in this case the two eyes) (see Wnuk Reference Wnuk2016a: 87–88). Although the verb was a dominant response only in right_just_eyes scene, it was also applied – albeit less frequently – in scenes with a turned head (always with a lateral eye movement). This is related to the fact that head rotation is usually accompanied by lateral eye movement.

4.2.3.1.5 Balay ‘to look up sharply’

The verb balay is associated with a sharply upward gaze, used with both simple upward paths and diagonal paths (#15, #31, #39; Figure 8A–C). The prototypical example of the verb involves gazing upwards with a sharply tilted head, as in the up_sharp scene (Figure 8A). This is how speakers typically enact balay. However, balay does not require a tilted head (see e.g. Figure 8B), which suggests up is determined on absolute basis rather than egocentrically. The angle between the spinal axis and the vertical head axis is therefore not relevant, but what the verb is sensitive to is the environmentally-defined up. In most everyday situations, up means towards the tree canopy as looking upwards is saliently associated with foraging activities related to trees, e.g. hunting arboreal game, collecting fruit, etc. Non-elicited instances of the verb in my corpus involve predominantly such contexts, i.e. in four of the six recorded sessions featuring balay, it is used either in the context of hunting or collecting fruit (see example (1) above). This is most likely the reason why balay associates with sharp gaze angles much more strongly than with non-sharp ones (see further Section 4.3.1 below). Although in this task balay surfaced mostly on its own, it can take direct objects expressing the visual goal, e.g. balay cey tawɔh ‘look up at gibbon’s bottom’ (look.up bottom gibbon), seen in example (1).

Figure 8 Scenes described predominantly with the verb balay. A: #15 up_sharp, B: #31 up_just_eyes, C: #39 up_and_right.

While the primary sense of balay is ‘to look up sharply’, there is a possibility it could also be applied in an extended sense of ‘to tilt one’s head sharply’, as suggested by the fact it was used with a closed-eyes scene (#52). Note, however, that, as stated for cikiey, the closed-eyes stimulus might have been unnatural from the perspective of Maniq speakers. The unusualness of the scene was also reflected in the explicit qualification of responses by some speakers, who combined balay into a multi-verb construction with lep or ɲup, both meaning ‘to close eyes’.

4.2.3.1.6 Yɔp ‘to look down’

The verb yɔp refers to downward gaze direction. It was employed with most scenes depicting looking downwards. They included looking down in various positions involving different body-to-head angles: while lying on belly (#9; Figure 9B), standing upright (#44, #37; Figure 9A), lying on side, leaning forward, leaning down, crouching (#19; Figure 9C), and lying on back. This indicates yɔp – like balay – is determined with respect to the absolute and not egocentric frame of reference. Yɔp applies also with diagonal paths such as down-and-right (#43) and complex down paths such as down-under (#19; Figure 9C). It was also used for bowing the head without gazing (#54), but as mentioned above, the significance of this pattern is unclear given the unnaturalness of this action and the fact that it’s easy to mistake it for a gazing situation since the eyelids are down in both situations. In actual everyday use, yɔp typically features in the context of foraging, e.g. tuber-digging, or is used with reference to people, monkeys and various tree animals looking down to the ground. For instance, in my Maniq corpus the verb occurs in such contexts in three out of the four recorded sessions in which non-elicited examples of yɔp were attested (see example (2) above).

Figure 9 Scenes described predominantly with the verb yɔp. A: #44 down_into_bin_upright, B: #9 down_lying_on_belly, C: #19 down_under_chair.

4.2.3.2 Other verbs

4.2.3.2.1 Cakip ‘to bow one’s head sharply’

The verb cakip is associated with bowing one’s head sharply (#30; Figure 10). Its primary reference is posture so it does not refer specifically to gazing, but it is discussed here because of its strong implication of a downward visual path. Given that the activity of bowing one’s head sharply prototypically co-occurs with looking down, gazing is usually presupposed when cakip is used. Hence, while the downward gaze path is associated mainly with the verb yɔp, cakip is confined to cases involving bowing one’s head sharply. Occasionally, however, speakers form complex predicates combining it with yɔp and making the information about gaze explicit, as in (24).

Figure 10 The scene described predominantly with the verb cakip: #30 down_sharp.

Unlike the other vertical-path verbs – balay and yɔp, cakip is defined egocentrically, i.e. it is dependent on the angle between the spinal and head axes, resulting from head flexion (bowing). Cakip is also associated with the default body posture and motion of some terrestrial animals, e.g. turtles and frogs, and is additionally employed in the sense of an existential verb with those animals, e.g. baliw hɨc cakip ‘there are no frogs’ (frog neg bow.head).

4.2.3.2.2 Piwɛ ‘to lurk, to look sneakily, e.g. from a hiding place’

The verb piwɛ refers to looking sneakily, often from a hiding place. It was the dominant response for the scene depicting looking out of a room (#11; Figure 11A). It was also occasionally elicited by its mirror image – looking into a room – as well as looking under a chair while crouching. All situations were to some extent reminiscent of a canonical example of piwɛ, acted out by a Maniq speaker in Figure 11B.

Figure 11 Examples of piwɛ. A: scene #11 out_of_room, B: canonical instance of piwɛ acted out by a Maniq speaker.

Formally, piwɛ is a causative of wɛ ‘to walk around looking for food’ (usually attested in the imperfective form wwɛ – recall Section 4.1.2 above). However, its meaning appears to be more specific than that associated with a regular causative derivation (Wnuk Reference Wnuk2016a: 77–79), suggesting a degree of idiomaticity. Because of its strong link to the foraging context, its semantics is likely richer than this task was able to uncover. While visual path information is certainly present in the prototypical uses of the verb, it is not clear to what extent it is part of the core lexical meaning.Footnote 9 Based on speaker’s enactments – which always involve looking from behind a specific physical object – the verb might encode an object-anchored path from behind, but its occurrence with other types of paths suggests it is only loosely associated with a prototypical path and is better conceived of as a manner verb relating to looking sneakily.

4.3 Summary and discussion

The evidence from both the translation questionnaire and picture-naming task revealed a core set of looking verbs incorporating information about visual path. These include verbs used with vertical, horizontal, and diagonal paths – pəntɛw, cikiey, ciyɛ̃k, balay, yɔp, wwɛ, and pədɛp (Section 4.3.1) – and verbs used with object-anchored paths – dɛŋ (Section 4.3.2).

4.3.1 Vertical, horizontal, and diagonal paths

Table 4 provides a summary of the distinctions made by verbs referring to vertical, horizontal and diagonal paths, based on the dominant responses in the canonical scenes from the picture-naming task (‘canonical’ here refers to scenes with neutral posture, in which change of gaze trajectory is accompanied by head movement). The only exception is the verb ciyɛ̃k ‘to look/move eyes sideways’, which is associated more closely with the position of the eyes rather than the head and is added here based on dominant responses to a non-canonical scene (#6).

Table 4 Dominant responses describing different gaze directions in canonical scenes (neutral standing posture, change of gaze trajectory accompanied by head movement). Paths marked by stripes were not included; the vertical dashed line separates backward from the remaining looking directions and includes both BACK-via-RIGHT and BACK-via-LEFT paths ■■■■.

Pəntɛw covers the most neutral straight-and-level gaze direction as well as slight (~45ᵒ) upward and sideways gaze angles. The three main verbs covering non-neutral directions are balay, yɔp and cikiey. Balay is associated with up, yɔp with down, and cikiey with sideways/back. Despite having largely corresponding denotations, these verbs differ in subtle semantic detail. While yɔp is used with a relatively slight downward angle of gaze, balay and cikiey require more pronounced up and sideways angles. Balay has the broadest application and includes various examples of looking up and tilting one’s head back. Cikiey, on the other hand, covers all instances of gazing sideways and back as long as they are accompanied by head turns. Yɔp refers to gazing downwards, but if the action involves bowing the head sharply, cakip is preferred.

Not included in Table 4 are two other verbs: wwɛ ‘to look around’ and pədɛp ‘to look around jerkily’, which featured in translations but not in picture-naming. Based on the attested uses of these verbs, they are tentatively analysed here as path-encoding looking verbs expressing the notion of around, with pədɛp additionally expressing manner. However, given that only a few instances of these verbs were attested, further investigation is needed to confirm if indeed they encode visual path. The issue is of particular relevance not only to the typology of perception verbs, but also more broadly, especially in the case of pədɛp, in that it can speak to the debate in verb semantics literature regarding whether both manner and directed path (result) meanings can be lexicalized together (see Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1985, Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Hovav, Malka, Levin, Hovav, Doron and Sichel2010, Beavers & Koontz-Garboden Reference Beavers and Koontz-Garboden2012).

Note that left, right and back, as encoded in the verbs above, are egocentric, i.e. derived from bodily axes of the perceiver, while up, down and level are absolute, i.e. determined with reference to gravity and environmental features. Only cakip, despite implicating a downward visual path, is tied to bodily axes. It differs from the other verbs in this set since it is primarily related to body posture rather than gaze.Footnote 10

Since the egocentrically-defined verbs – i.e. cikiey, cakip, ciyɛ̃k – are associated with specific body postures (and in the case of ciyɛ̃k, position of the eyes), the partitioning of visual paths is partially dictated by bodily mechanics. For instance, the fact that cikiey encompasses the lateral and backward directions can be explained by the perceptual similarity of the head movement involved in these two gaze trajectories.

Apart from the body, an important factor shaping the semantics of verbs in this set is earth-based verticality and environmental features. The fact that vertical verbal categories exist is linked to our bipedalism and ultimately accounted for by gravity (Miller & Johnson-Laird Reference Miller and Johnson-Laird1976, Lyons Reference Lyons1977, Brown & Levinson Reference Brown and Levinson1993). It is not immediately obvious, however, why the Maniq verbs of looking partition gaze directions the way they do. To recall briefly, balay denoting an upward gaze path refers only to sharp (~90º) gaze angles, yɔp denoting a downward gaze path refers both to mild and sharp angles (~45–90º), and pəntɛw covers all that is in between, i.e. level and mildly upward (~45º) paths. To understand this division, one needs to take into account culture-specific factors since local functional considerations can shed light on the semantic structuring of spatial categories in languages (see Coventry, Carmichael & Garrod Reference Coventry, Carmichael and Garrod1994, Levinson, Meira & The Language and Cognition Group 2003, Feist Reference Feist2008).

Looking high up (balay) into the tree canopy is a salient activity accompanying many of the daily foraging practices (e.g. hunting arboreal game, collecting honey, fruit, bamboo for blowpipes, etc.). Since the forest is often dense and most of the desired objects are situated high in the canopy, one is typically forced to gaze up at a sharp angle.

Looking sharply up (balay) is functionally distinct from slightly up (pəntɛw), which is usually combined with looking into the distance and not tied to the foraging context specifically. In this sense, a slightly upward gaze path is more similar to a horizontal gaze path than to a sharply upward turned one. In contrast, gazing down as marked by the verb yɔp begins already with a slightly downward visual path and also includes sharper gaze trajectories. There is no boundary between sharp and non-sharp for down as these gaze angles are not earmarked for different activities. For instance, foraging activities on the ground such as hunting for terrestrial animals or tuber digging often involve both sharp and non-sharp gaze angles. One reason for that is that the path to the ground is short so the gaze angle can be changed relatively easily (unlike in the case of a longer path). From a functional point of view, then, gazing slightly downwards and sharply down are similar. Note that even cases involving a sharply bowed head – although associated primarily with cakip – can be described with yɔp. The reason why cakip is usually preferred for scenes with a sharply bowed head is linked to the high salience of this body posture. Yɔp itself is not sensitive to body posture but refers to down defined in absolute terms. Occasionally, speakers employ yɔp as well as cakip within a single description, but since there is a strong implication regarding the visual path in cakip, it normally occurs on its own.

Summing up, the encoding of paths of vision in Maniq is shaped by multiple pressures. The locus of the main distinctions is provided by the two main spatial coordinates underlying our three-dimensional world – the horizontal and vertical planes. How this space is carved into specific categories is influenced by, on the one hand, universal constraints dictated by gravity and the mechanics of the human body, and, on the other hand, culture-specific considerations that render certain discontinuities more salient than others. It is important to point out that such fine-tuning of spatial distinctions to the parameters relevant for visual perception is possible largely because of the verbal lexicalization strategy. The sole fact that Maniq lexicalizes visual paths in verbs rather than simply applying the general spatial expressions (‘satellites’) to mark them, means the semantics of verbs of looking can be defined independently of satellites. Thus, unlike in English or Spanish, where visual paths are dictated by spatial prepositions, the partitioning of visual paths in Maniq is not constrained by satellites. I return to this again in Section 7.

4.3.2 Object-anchored paths

Object-anchored paths were generally not encoded in verbs expressing specific spatial relations such as ‘look into’, ‘look across’, ‘look under’, etc. The stimuli probing for these distinctions revealed many such paths are associated with the verb dɛŋ ‘to look at, to see’. This verb emerges as the main descriptor applied with visual paths which include an endpoint object.

Dɛŋ is semantically general and applicable in various contexts. It was the most frequent verb in both tasks. It collapses the distinction between the activity and experience (as in see vs. look, see Viberg Reference Viberg1984), covering all predicates with perceiver as the grammatical subject. Depending on context, it is thus best glossed as ‘to see, to look at’. The current data show further that dɛŋ is unspecified with respect to direction. In the context of direction-encoding verbs of looking discussed here, the question arises whether it could be considered a superordinate term forming a hyponymic relation with these verbs. In other words, is there a hierarchy in the vision verb lexicon?

The available evidence does not suggest a straightforward answer, though some preliminary observations can be made. If we consider dɛŋ in its basic underived form, hyponymy is unlikely since dɛŋ and directional verbs differ with lexical aspect. Hyponyms form a ‘type–token’ relationship with their superordinate terms; hence, they are expected to have all of their superordinate’s features (e.g. Murphy Reference Murphy2003).Footnote 11 The aspectual mismatch between dɛŋ and the other verbs would therefore rule out hyponymy (see Gisborne Reference Gisborne2010: 154 for a similar observation for English). In its default reading, dɛŋ marks an accomplishment, since it refers to a telic situation, i.e. it has an inherent endpoint and is spatially bounded (although the action can extend in time). This is in line with the fact that whenever dɛŋ was used in the picture-naming or the translation task, it usually involved scenes which presupposed an endpoint object. Similarly, it was consistently employed for all translations of the verb see in another translation questionnaire ‘Grammar of perception’ (Norcliffe et al. Reference Norcliffe, Enfield, Majid, Levinson, Norcliffe and Enfield2010) carried out independently on a separate occasion. Dɛŋ also combines with the causative to derive the meaning of ‘show, cause someone to see’: pi-dɛŋ (caus see). The direction-encoding verbs like balay, yɔp etc., on the other hand, seem to place more emphasis on the path itself and lack inherent endpoints. This is reflected in the frequency of overt goals with different verbs. For instance, in the picture-naming task, goals were overtly expressed with dɛŋ more often than with any other verb (twenty-two times, compared to seven times for pəntɛw, two times for balay, and once for cikiey and piwɛ). In addition, dɛŋ was sometimes employed with a specific function of introducing an endpoint, as in (25), elicited for the down-into-bag scene.

In this example the verb yɔp specifies the downward path, while dɛŋ introduces the visual endpoint, which in this context can be interpreted as the inside of the object.

While dɛŋ in its root form seems to contrast with other verbs in telicity, this distinction can be manipulated with derivational morphology. When derived with the imperfective, the verb becomes atelic (dŋ-dɛŋ ‘to be looking (around)’ (ipfv-look)) since the imperfective morpheme removes spatio-temporal boundaries from the event structure (see Wnuk Reference Wnuk2016a: 79–82).Footnote 12 The imperfective form might therefore be a more appropriate candidate for a superordinate ‘looking’ term, though it would be unusual for a morphologically complex form. Further investigation targeting this issue directly is needed to explore this in depth.

5. Visual perception vs. motion events

One of the central questions pursued in this article is whether the distinctions encoded across distinct sets of verbs in Maniq follow the same underlying semantic principle. The focus of the investigation, more specifically, is the encoding of path: Are visual paths and motion paths similar in Maniq? Slobin (Reference Slobin and Mueller-Gathercole2009) proposed that physical and visual paths are universally conceptually equated in the use of the same types of spatial expressions. This is supported by the fact that Maniq employs the same PPs with expressions of motion and vision, e.g. daʔ kapin ‘up’, hwaŋ hayɔl ‘straight ahead’, etc., as in (26) and (27).

However, path-encoding verbs – the main path-encoding strategy for both motion and vision – are not shared across the two domains. Motion verbs do not express visual paths (e.g. sa expresses downward motion but not downward gaze), and vice versa, vision verbs do not express paths of motion (e.g. yɔp expresses downward gaze but not downward motion). Although the verbal forms are not shared, it is still possible the spatial distinctions underlying the verbs are, since languages often display common lexicalization patterns across distinct lexical sets (Gentner Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982). The question then is: Are the path distinctions encoded in verbs of vision and verbs of motion similar?

The basic paths mapped onto vision verbs – up, down, straight-and-level, sideways/back – are reminiscent of the basic paths mapped onto motion verbs – up, down, horizontal (see Table 1). Among these, the vertical directions up and down are in both cases established in the same way (i.e. by use of an absolute frame), while the horizontal directions are determined differently (i.e. relative to the absolute frame for motion, and to the egocentric frame for vision). This difference is due to the fact that motion verbs lexicalize ground objects, while the verbs of horizontal gaze lexicalize the position of the experiencer’s body/eyes. An additional point of difference is the place where the boundaries between specific categories are drawn. For instance, sideways and back are encoded in two distinct verbs of motion (kapoŋ ‘to turn sideways, to change direction of motion’ vs. paliŋ ‘to turn back, to change direction of motion’), but they constitute a single category expressed with one verb of looking (cikiey ‘to look sideways/back’).Footnote 13 Despite such differences, at the global level the vertical and horizontal paths are similar.

When it comes to object-anchored paths, however, motion and vision differ significantly. In motion, there is a set of verbs encoding specific figure–ground configurations such as into/under/through, out, over, e.g. hok ‘to enter/go under’, yɛs ‘to exit’, laŋkah ‘to go over an obstacle’ (see Section 3 above). In contrast, in vision we find a general endpoint-encoding verb dɛŋ. Aside from this case, no other specific verbs marking object-anchored paths of vision were found, though piwɛ seemed to be loosely associated with looking from behind an object. Even explicit naming of these types of paths in external phrases was rare. In addition, contrary to other languages with multi-verb predicates (notably the surrounding Thai; see Takahashi Reference Takahashi2000, Slobin Reference Slobin and Mueller-Gathercole2009), Maniq does not express object-anchored gaze paths with motion verbs like ‘exit’, ‘enter’, etc. These differences are most likely due to the different nature of physical and fictive motion events, as fleshed out in Section 1 (see Slobin Reference Slobin and Mueller-Gathercole2009). For instance, the lack of ‘exit’-type verbs for vision and the sporadic expression of boundary crossing can be explained by the differing dynamics of visual perception and motion events.

To conclude, paths encoded across the two verb sets differ in a number of ways, but they also converge on a number of distinctions. They are anchored in the same spatial coordinates underlying three-dimensionality – the vertical and horizontal planes (Miller & Johnson-Laird Reference Miller and Johnson-Laird1976, Lyons Reference Lyons1977). In the rest of this article, I will draw on extensive lexical evidence from the Maniq lexicon and demonstrate these spatial planes do not only underlie vision and motion, but in fact provide an organizational principle pervading several areas of the Maniq lexicon.

6. Recurrence of semantic structure in the lexicon

The lexicalization of spatial notions in verbs of motion and verbs of looking follows a general semantic principle organizing these two domains. Its essential aspect is a systematic recurrence of semantic structure across domains. To take an example of down, the previous sections established that the downward path is lexicalized in two motion verbs – sa ‘to descend’ and wet ‘to go downstream’ – and the looking verb yɔp ‘to look down’. down is thus a recurring semantic notion found independently across two distinct lexical sets: verbs of motion and visual perception. While recurrence of semantic structure is also characteristic of derived expressions (e.g. the English phrasal verbs go down and look down), here the recurring semantic material is not overtly marked (i.e. sa, wet and yɔp do not exhibit formal similarity). Aside from verbs of motion and verbs of looking, two additional verb sets can be added to this list: positional verbs and verbs related to yam digging (digging and disposing of soil). Like verbs of motion and visual perception, these verbs lexicalize spatial notions. For instance, down is encoded in the positional verb cibɛl ‘to be upside down’ and the digging verb bay ‘to dig down’. Together with the motion and vision verbs, these verbs constitute a grouping of formally unrelated items sharing a common semantic notion. As I will show below, further examples of such shared patterns connecting multiple verbs from unrelated sets involve the notions up and horizontal.

The systematic recurrence of semantic structure in these lexical sets is reminiscent of the lexico-semantic concept of semplates (Levinson & Burenhult Reference Levinson and Burenhult2009). A semplate (a blend of ‘semantic template’) is a term referring to configurations consisting of ‘an abstract structure or template, which is recurrently instantiated in a number of lexical sets, typically of different form classes’ (Levinson & Burenhult Reference Levinson and Burenhult2009: 153). Semplates normally involve multiple lexical subsets structuring a single well-defined domain, e.g. landscape or subsistence. For example, Levinson & Burenhult (Reference Levinson and Burenhult2009: 159–161) describe the ‘landscape semplate’ in Jahai (spoken in Malaysia), in which the same set of spatial oppositions is mapped onto different lexical sets within the landscape domain: motion verbs, locative verbs, place names, and metaphorical nouns denoting landscape features. The notion of a semplate is special in that it captures both the geometric structure of the semantic oppositions within lexical sets as well as the higher-order analogical relations between lexical sets.

The configuration of spatial oppositions in Maniq is semplate-like, in the sense that it is associated with an abstract semantic structure. However, since it is not restricted to one well-defined domain, but associated with several unrelated domains (motion, vision, etc.), it departs from prototypical semplates. Irrespective of this, there is a striking similarity between semplates and this configuration as both rely on the same general idea, i.e. they provide a semantic organizational principle structuring multiple lexical sets.

The Maniq semplate-like structure encodes the spatial notions of up, down, and horizontal. Figure 12 provides a summary of the relevant verbal subsets. Depending on the verb, the horizontal category can be associated with horizontality in general (as in tiek ‘to lie (be positioned horizontally)’) or express a specific type of horizontal category relevant for a particular domain (as in cɛn ‘to move along the top of an object’ for the domain of motion on trees, or small obstacles). All but two items in the semplate-like structure are monomorphemic and formally unrelatable, which is a common feature of categories making up semplates but not an absolute rule since lexically overt multimorphemic forms are also attested in semplates (see Levinson & Burenhult Reference Levinson and Burenhult2009). The two exceptions include the complex predicates: kac huyuʔ ‘to dispose of soil by throwing it up’ and kac sɛy ‘to dispose of soil by throwing it to the side’, where the shared verb kac indicates the activity of scooping up soil while the second verb determines the direction (though neither *huyuʔ nor *sɛy seem to ever occur on their own and speakers reject such forms).

Figure 12 Verb sets participating in the spatial semplate-like structure represented as vectors.

While the spatial coordinates underlying this structure are common for all lexical sets, the exact category boundaries are domain-specific. For instance, up and down are somewhat different for motion verbs from different sets, e.g. milder for ‘ascend-hill’ verb and steeper for ‘ascend-tree’ verb. Similarly, horizontal is defined with respect to different reference points depending on the verb set, i.e. landscape features for motion verbs, body for vision and locative verbs, and tuber anatomy for yam-digging verbs.

Semplates are typically manifest across different form classes. There is some preliminary evidence the spatial semplate-like structure in Maniq also extends into other form classes, which would suggest the pattern is not restricted to verbs, but applies more generally. For instance, horizontality and verticality is mapped onto nouns indicating different tuber parts, i.e. jalieʔ ‘main tuber (growing vertically)’, lapieh ‘side tuber (growing horizontally)’. However, since the present focus is on verbs, other form classes are not explored further here.

7. Conclusions

The evidence reviewed in this article demonstrates visual paths are encoded in verb roots in Maniq. This is noteworthy since it has been observed before that visual paths are resistant to being lexicalized in verbs (e.g. Slobin Reference Slobin and Mueller-Gathercole2009). This article is the first extensive report of the verb-framing strategy for looking events. Although detailed accounts of similar systems are missing, we know this strategy is not exclusive to Maniq as there are some previous reports of languages with looking verbs marked for direction, e.g. Toba, spoken in Argentina (Klein Reference Klein1981), and Kayardild, spoken in Australia (Evans & Wilkins Reference Evans and Wilkins2000). Together with these earlier sources, the Maniq data show languages need not lose their verb-framed nature in descriptions of visual perception events. The Maniq case is thus testimony to the fact visual paths are not generally barred from being encoded in verbal roots. This has important implications for the typology of vision verbs, as it suggests the ‘typological split’ experienced by the verb-framed languages such as Spanish is not a universal phenomenon. In addition to these theoretical implications, the study makes a methodological contribution by identifying relevant semantic parameters and offering example methods for investigating such verbs.

The present findings suggest visual paths may be coded in verbs, but this is not true of all types of visual paths in Maniq. For example, no special verbs exist for paths with boundary-crossing such as into and out of. This might reflect a common trend since among the infrequent mentions of path-encoding verbs of looking in the literature, paths without inherent boundaries dominate, e.g. walmurrija ‘look up in the sky’, warayija ‘look back’, rimarutha ‘look eastwards at’ in Kayardild (Evans & Wilkins Reference Evans and Wilkins2000: 554), sa:t ‘to look up (at something moving)’, la ‘look ahead (in direction of something nearby)’ in Toba (Klein Reference Klein1981: 234). However, examples which involve boundary-crossing are not absent, e.g. ĩe ‘look outward’, wa ‘look for, search (look inward)’ (also in Toba). Based on this rather small sample, it appears verbs with boundary-crossing paths might indeed be rare, but far more attention needs to be devoted to documentation of verbs of looking cross-linguistically before it becomes clear how robust this tendency is.

The specific types of looking events lexicalized in Maniq verbs are culturally salient activities implying specific scenarios. The cultural salience as well as Maniq’s consistent preference for lexicalizing spatial notions in verb roots are the key factors in the existence of these verbs in Maniq. What the Maniq data show most clearly is that the lexicalization of visual paths in verbs rather than satellites has a non-trivial impact on their semantics. As elucidated in the previous sections, the lexicalization patterns within paths of vision reflect a complex interplay of pressures – vision verbs are synchronized with universal constraints and tailored to culture-specific requirements (see Evans & Levinson Reference Evans and Levinson2009, Majid Reference Majid and Taylor2015). The exact meanings of verbs of looking are thus shaped by earth-based verticality, bodily mechanics, the environment, and cultural scenarios of which looking is a salient part. This vision-specific fine-tuning of the spatial notions relevant for paths would not have been possible if the preferred strategy was to encode path in satellites. In such a scenario, it is probable the meaning of the visual paths would be dictated by the general meaning of the satellites. What the verb-encoding strategy affords a language is a freedom to adjust the fine semantic details of its spatial categories according to a domain-specific logic.

Different domains encoding spatial information in verbs display fine-level differences as to how spatial distinctions are defined (e.g. horizontal locked to body vs. landscape vs. tuber axes). At the global level, however, spatial notions are similar across domains. This is illustrated by the spatial semplate-like structure, where similar spatial notions are lexicalized in at least four otherwise unrelated semantic fields. With striking systematicity, Maniq organizes its verbs of looking, verbs of motion, positionals, and verbs related to yam digging around the same spatial notions of up, down and horizontal. Thanks to domain-specific fine-tuning of these notions, spatial information in verbs is more precise than, for instance, spatial information encoded in prepositions, which have a more general range of applicability. This implies that knowing how to use these verbs correctly requires from the speaker not just general spatial knowledge, but the specific organization of spatial knowledge in a particular domain. The semantic fields which partake in the Maniq spatial semplate-like structure relate to culturally salient notions with the relevant domains, often linked to the indigenous expertise of the speakers, and central in their way of life. This in fact seems to be a characteristic of semplates found in other languages too, e.g. Tzeltal (Mexico), Yélî Dnye (Papua New Guinea), and Jahai (Malaysia).

Vision verbs and other lexical sets making up this semantic configuration are most notable because they illustrate systematicity in the organization of information. In general, verbs are believed to have considerable freedom in what event aspects they lexicalize (Gentner Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982, Talmy Reference Talmy and Shopen1985). This is reflected in substantial cross-linguistic variation of verb meaning (e.g. Bowerman et al. Reference Bowerman, Gullberg, Majid, Narasimhan and Majid2004, Levinson & Wilkins Reference Levinson and Wilkins2006, Majid et al. Reference Majid, Boster and Bowerman2008, Malt et al. Reference Malt, Ameel, Imai, Gennari, Saji and Majid2014). When compared to concrete nouns, verbs show a ‘more variable mapping from concepts to words’ (Gentner Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982: 47), and have been hypothesized as ‘likely … the most cross-linguistically variable part of a language’s vocabulary in terms of denotation’ (Evans Reference Evans and Thieberger2011: 189, though see Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Roberts and Lupyan2020 for observations on similarly high variability in conjunctions and prepositions). Within a particular language, however, there is less variability since the packaging of information within verbs may be ordered according to an underlying pattern. As the Maniq data show, these patterns need not be overt, but can be encoded in non-transparent verb forms. Thus, even though the various verbs are not formally related to one another, the meanings encoded by them show correspondences. This kind of systematicity is less noticeable, yet – similar to the overt forms of systematicity (Dingemanse et al. Reference Dingemanse, Blasi, Lupyan, Christiansen and Monaghan2015) – it is of high significance, playing a supporting role in language acquisition (Gentner Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982, Choi & Bowerman Reference Choi and Bowerman1991, Brown Reference Brown2001, Slobin Reference Slobin2001) and acting as a shaping force in lexicalization.

APPENDIX A

Translation questionnaire

APPENDIX B

Picture naming: Task stimuli