Mounting research evidence suggests that interpersonal relationships at work are essential for the efficient and effective functioning of today’s organizations (Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002; Nahum-Shani, Henderson, Lim, & Vinokur, Reference Nahum-Shani, Henderson, Lim and Vinokur2014; Eissa & Wyland, Reference Eissa and Wyland2016). Particularly, research has long supported the notion that the supervisor–subordinate relationship is critical in explaining and determining how subordinates behave in organizations. Such relationship is likely to impact subordinates’ work behaviors either positively or negatively, depending on the nature of the relationship (viz., supportive vs. undermining, Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002; Nahum-Shani et al., Reference Nahum-Shani, Henderson, Lim and Vinokur2014). Notably, research is quite clear on the outcomes of supervisory supportive behaviors. For example, supportive supervisors are likely to positively influence subordinates’ job satisfaction and stress levels (Babin & Boles, Reference Babin and Boles1996), turnover (Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhoades, Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002), as well as in-role and extra role performance (Shanock & Eisenberger, Reference Shanock and Eisenberger2006). Though, when it comes to supervisor social undermining behaviors, we still know very little as to how these negative forms of supervisory behaviors influence subordinates’ behaviors in the workplace. Specifically, while we know that supervisor social undermining may adversely impact positive employee outcomes such as employee health and well-being and organizational commitment (Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002; Nahum-Shani et al., Reference Nahum-Shani, Henderson, Lim and Vinokur2014), limited research has linked supervisory undermining behaviors to negative forms of employee behavioral outcomes. This line of inquiry is particularly critical given that research has often suggested that negative workplace outcomes may be the result of various negative social interactions among employees (e.g., Andersson & Pearson, Reference Andersson and Pearson1999).

To address this research limitation, we follow recent research theorizing by investigating a negative form of organizational leadership (viz., supervisor social undermining) as a link in a chain of negative workplace social interactions (e.g., Aryee, Chen, Sun, & Debrah, Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007; Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne, & Marinova, Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012). Indeed, research has focused on building and testing theoretical models that largely link the attitudes and behaviors of lower level employees to those of their superiors – a link that builds on a system of workplace mutual relationships (Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador, Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012). In keeping with this emerging research, our study explores supervisor social undermining as a critical workplace event by testing a trickle-down model of social undermining – defined as ‘… behavior intended to hinder, over time, the ability to establish and maintain positive interpersonal relationships, work-related success, and favorable reputation’ (Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002: 332).

Particularly, the main purpose of the current study is to investigate why supervisor social undermining may be associated with coworker social undermining in the workplace. Examples of supervisor (coworker) social undermining behaviors include insulting subordinates (coworkers), spreading rumors about subordinates (coworkers), making subordinates (coworkers) feel incompetent, and belittling subordinates’ (coworkers’) work efforts (see Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002). Our study is consistent with the developing literature examining trickle-down models that link supervisor–subordinate attitudes and behaviors to their social interactions (e.g., Aryee et al., Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012). We argue that there is a positive relationship between supervisor social undermining and coworker social undermining. In doing so, we draw on social cognitive theory (SCT) (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986), which suggests that individuals typically learn certain behaviors by observing and emulating the behaviors of powerful and credible role models (e.g., leaders).

Nevertheless, as prior research suggests, subordinates will typically avoid directing negative behaviors toward their immediate supervisors. This is because supervisors normally possess formal power over their subordinates and, thus, engaging in negative behavior that targets supervisors might put employees at risk of disciplinary action, counterretaliation, or the possibility of losing rewards (e.g., Aquino, Tripp, & Bies, Reference Aquino, Tripp and Bies2006; Tepper, Carr, Breaux, Geider, Hu, & Hua, Reference Tepper, Carr, Breaux, Geider, Hu and Hua2009). Therefore, we argue that easier and less threatening targets of social undermining behaviors are immediate coworkers. In other words, subordinates who are victims of supervisory undermining behaviors are more likely to emulate supervisors’ social undermining behaviors by usually directing them toward coworkers, who are less powerful targets.

Another key purpose of the study is to investigate under what conditions supervisor social undermining is more or less likely to lead to coworker social undermining. Hence, we suggest that whether subordinates engage in undermining behaviors toward their coworkers depends on their levels of bottom-line mentality (BLM) and self-efficacy. Specifically, we argue that both BLM and self-efficacy likely influence the strength of the positive supervisor–coworker social undermining relationship in two different ways. First, employees with high BLM have a ‘one-dimensional frame of mind that revolves around bottom-line outcomes’ and approach work situations ‘with a high level of competiveness’ (Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012: 343). Coupled with supervisor social undermining, these employees are more likely to undermine coworkers by hindering their success to secure the bottom line. Accordingly, we expect high levels of employee BLM to strengthen the positive supervisor–coworker social undermining relationship. Second, individuals with high self-efficacy believe that they have control and choice over outcomes (e.g., Bandura, Reference Bandura1997, Reference Bandura2012), which allows them to feel secure and confident about their job performance (Stajkovic & Luthans, Reference Stajkovic and Luthans1998). Specifically, these individuals are likely to feel self-assured about their competence to perform well and often feel certain about mastering goals (e.g., Bandura & Locke, Reference Bandura and Locke2003). Those with high self-efficacy related to their job performance also feel they have a high sense of autonomy and, thus, are less likely to engage in counterproductive work behaviors. Under conditions of supervisor social undermining, employees with high self-efficacy are less likely to mimic their supervisor social undermining behaviors as they hold more control and autonomy and see little value in hindering the success of their coworkers and, thus, are less likely to socially undermine them. Accordingly, we expect high levels of employee self-efficacy to weaken the positive supervisor–coworker social undermining relationship.

Based on the discussion above, the current study makes multiple contributions to the management and organization literature. First, we contribute to the emerging research on the trickle-down effect of leadership by providing empirical evidence of the positive supervisor–coworker social undermining relationship. Little research has examined the trickle-down effect from a ‘bad’ leadership perspective (see Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012 for an example); therefore, such examination is warranted. To examine this relationship, we draw on SCT (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986) to suggest that subordinates observe and learn from the behaviors of their superiors. Since supervisors are often viewed as credible role models (e.g., Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005), subordinates are likely to emulate their supervisors’ behaviors because they are thought of as acceptable. In this way, our study also extends research on supervisor social undermining by exploring a possible outcome, namely coworker social undermining – a research limitation that has not been explored yet.

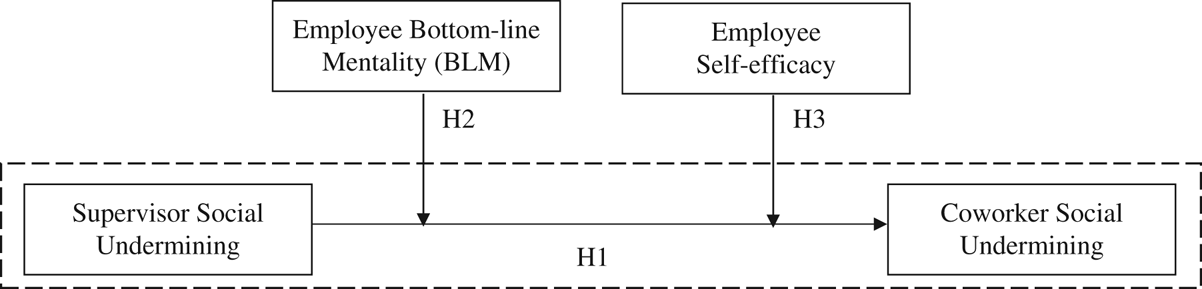

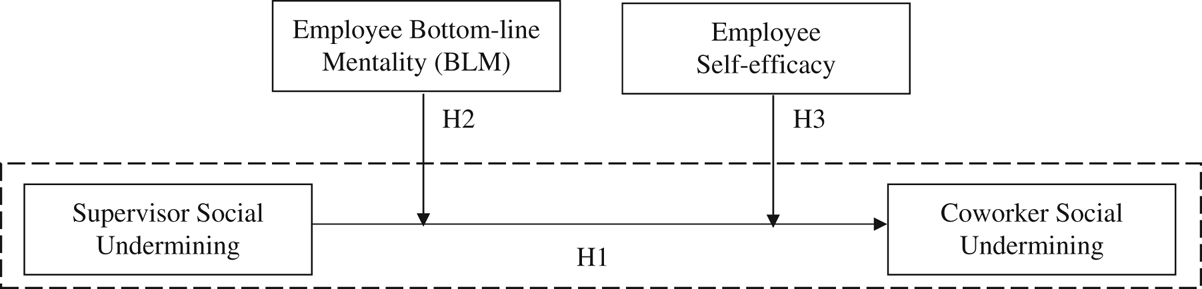

Second, whereas the research on coworker social undermining has been growing (e.g., Dunn & Schweitzer, Reference Dunn and Schweitzer2006; Duffy, Scott, Shaw, Tepper, & Aquino, Reference Duffy, Scott, Shaw, Tepper and Aquino2012; Eissa & Wyland, Reference Eissa and Wyland2016), empirical research that explores sources of coworker social undermining is still in its infancy. Research on coworker social undermining has consistently called for further research that examines antecedents of such costly workplace behaviors (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). Our study contributes to such research by exploring one possible antecedent, namely supervisor social undermining. In this vein, the second contribution of this study is to support and extend the work of Greenbaum, Mawritz, and Eissa (Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012) by providing a new perspective on social undermining behaviors by exploring an antecedent. Third, our study attempts to contribute to the limited research examining ‘moderators’ of trickle-down effects related to counterproductive work behaviors (Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012). To address this research limitation, we argue that the positive supervisor–coworker social undermining relationship depends on two moderators previously linked to social undermining behaviors, namely employee BLM and self-efficacy (Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). Overall, we incorporate our variables in a theoretical model (Figure 1) and test and present our results using field data from a number of information technology and mid-level financial organizations in India.

Figure 1 Hypothesized model

THEORETICAL OVERVIEW AND HYPOTHESES

Supervisor to coworker social undermining

SCT (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986) serves as the theoretical foundation upon which we develop our hypotheses. SCT contends that people learn behavior by observing and modeling the behavior of others. Behaviors that are emulated are generally those exhibited by role models who are deemed as influential and/or credible. In the workplace, supervisors are in a position of power and are often viewed as credible role models for appropriate behaviors (Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012). Indeed, research shows that employees notice and attend to their supervisors’ attitudes and behaviors (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). Consequently, the desirable (and undesirable) attitudes and behaviors of supervisors are often emulated and replicated by lower-levels employees because such attitudes and behaviors are often thought of as acceptable.

Previous research has drawn on SCT to investigate trickle-down models of attitudes and behaviors from supervisors to lower-level employees (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012). Yet, most studies using SCT have focused on the transfer of desirable or positive behaviors within the workplace. For example, Mayer et al. (Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009) provided empirical support for the notion that supervisors demonstrate ethical behaviors when their managers exhibit similar ethical behaviors. In addition to the transfer of desirable and positive behaviors, SCT has also been recently used to explain the transfer of undesirable and negative behaviors at work. For example, Mawritz et al. (Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012) conducted one of the first studies that has applied the underpinnings of this argument and similar contentions (e.g., Tepper, Duffy, Henle, & Lambert, Reference Tepper, Duffy, Henle and Lambert2006; Aryee et al., Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007). They provided support to the notion that abusive manager behaviors were positively associated with abusive supervisor behaviors, which, in turn, trickled down to impact negative behaviors within lower levels of the organization. Mawritz et al. (Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012) argued that subordinates are likely to notice their supervisors’ behaviors because subordinates are in regular contact with them and, therefore, they have ample opportunities to observe, remember, and replicate the supervisors’ behaviors, even negative ones.

While Mawritz et al. (Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012) applied this argument to abusive supervision; a similar argument is likely to hold for more covert forms of dysfunctional workplace social interactions such as social undermining. In the context of our study and in accordance with SCT, we argue that, given their assigned formal roles as bosses, when supervisors engage in social undermining, subordinates are more likely to perceive these behaviors as acceptable. Yet, given the potential for adverse outcomes, subordinates might not want to ‘get even’ or react by engaging in similar social undermining behaviors toward their supervisors. Previous researchers (e.g., Aquino, Tripp, & Bies, Reference Aquino, Tripp and Bies2006; Tepper et al., Reference Tepper, Carr, Breaux, Geider, Hu and Hua2009) have noted that supervisors have control over employee resources (e.g., incentives, promotions) and performance evaluations. Thus, it is not always in the best interest of the employee to engage in negative behaviors that target the supervisor. Instead, employees usually look elsewhere to emulate social undermining behaviors, making coworkers more realistic targets. Notably, coworkers serve as an easier target since employees spend much of their time interacting with them.

In sum, supervisors are deemed as powerful and credible role models in the workplace. As supervisors engage in social undermining behaviors toward their employees, they send cues implying such behaviors are allowed. In turn, social undermining behaviors become a means by which employees interact with each other. Given that coworkers are less threatening targets to subordinates, we contend that, based on SCT (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986), subordinates are likely to mimic the social undermining behaviors of their supervisors, but engage in social undermining toward coworkers instead. Thus, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 1: Supervisor social undermining is positively related to coworker social undermining in the workplace.

The role of employee BLM

As previously discussed, and in accordance with SCT (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986), supervisor social undermining is likely linked to coworker social undermining. Yet, the extent to which employees engage in social undermining toward coworkers is likely to vary depending on employees’ levels of BLM. According to Greenbaum, Mawritz, and Eissa, employees with a BLM adopt a ‘one-dimensional thinking that revolves around securing bottom-line outcomes’ (Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012: 344). Adopting a bottom-line approach – when combined with other factors – may certainly provide various benefits to the organization; however, there are notable caveats for using one-dimensional thinking (e.g., Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1988; Barsky, Reference Barsky2008; Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). Particularly, individuals with a BLM are more likely to believe that the bottom line is the only important outcome; therefore, they are more prone to ignore other equally important workplace outcomes and priorities such as treating others with respect and dignity (Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). Furthermore, those with a BLM are more likely to embrace a competitive stance and view their own bottom line as a game with a winner and loser (see Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1988; Callahan, Reference Callahan2004). In this way, in order to be the winner, an individual becomes so engrossed in the outcome of the bottom-line that the consequences of their own behaviors are likely overlooked. Consequently, employees with a high BLM are expected to strain social and interpersonal relationships within the workplace (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012).

We argue that, coupled with supervisor social undermining, employees who have a high BLM may be more likely to engage in social undermining toward coworkers. As suggested by Greenbaum, Mawritz, and Eissa (Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012), employees with a BLM may see coworkers’ success as threatening and view workplace social and interpersonal interactions as a game to be won. In turn, coworker social undermining may be used as a means to look better at the expense of coworkers. For example, an employee with a high BLM who is also a victim of supervisor social undermining may perceive undermining coworkers an adequate way to win the game by improving their own reputation. That is, an easy way to be a winner is to hinder the success of coworkers, belittle their efforts, or slow them down to make them look bad.

In accordance with SCT (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986), when supervisors engage in social undermining behaviors, they signal that undermining behaviors are acceptable within the organization. In this way, employees who have a high BLM are more likely to seek and identify ways to use these acceptable social undermining behaviors in a competitive way as a means to win. Employees with a high BLM may, perhaps, try to secure their own bottom line by making a public promise to help a coworker, but then rescind the offer at the last minute or delay the promised help in order to make their coworker look less productive. Additionally, they could use more subtle forms of undermining behaviors such as providing incomplete or misleading information that might impact the coworker’s job. In this vein, because supervisor social undermining may pose a threat to securing one’s own bottom line, but is deemed as appropriate behavior, employees with a high BLM are likely to take advantage of these acceptable behaviors to ensure their own bottom-line outcomes.

In contrast, with the preceding argument in mind, employees with low levels of BLM would be less likely to approach social and interpersonal work relationships with a win/lose mindset (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1988; Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). As such, they would be less likely to look for ways to use negative but acceptable workplace behaviors as a way to win within their social interactions. Hence, even in the presence of supervisor social undermining, employees with a low BLM would be less willing to strain their own social and interpersonal relationships and would be less likely to role model the social undermining behaviors of their supervisors. Thus, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 2: Employee BLM moderates the relationship between supervisor social undermining and coworker social undermining such that this relationship is stronger when employee BLM is high as opposed to low.

The role of employee self-efficacy

We also argue that the trickle-down effect of supervisor to coworker social undermining may vary based on employees’ perception of their own levels of self-efficacy about job performance. Self-efficacy influences an individual’s perception of their own effectiveness when performing a task or success at accomplishing a goal (e.g., Bandura, Reference Bandura1997, Reference Bandura2012; Bandura & Locke, Reference Bandura and Locke2003). Indeed, Bandura (Reference Bandura2012) suggested that self-efficacy plays an important role in individuals’ functioning and behaviors. For example, within various organizational settings, research has suggested that high levels of employee self-efficacy are strongly related to being successful at work (e.g., Stajkovic & Luthans, Reference Stajkovic and Luthans1998).

Also, as suggested by Stajkovic, employees with high levels of self-efficacy and confidence may ‘feel certain they can handle what they desire to do or needs to be done’ (Reference Stajkovic2006: 1209). Indeed, when individuals believe they have a high sense of autonomy or control over consequences, they generally believe they can face life’s challenges and reach success on their own merit (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). Notably, research also shows that employees’ perception of their own levels of self-efficacy may be associated with their levels of self-esteem, locus of control, and emotional stability (Judge, Erez, Bono, & Thoresen, Reference Judge, Erez, Bono and Thoresen2003). Self-efficacy, however, generally relates to ‘one’s estimate of one’s fundamental ability to cope, perform, and be successful’ (Judge & Bono, Reference Judge and Bono2001: 80).

We argue that employees with high levels of self-efficacy are less likely to damage or spoil the image and success of their coworkers by allowing their supervisor’s social undermining behaviors to influence their own work behaviors. Indeed, individuals with high self-efficacy are better able to cope with work-related adversities and more likely to persist as they encounter hardships (Gist & Mitchell, Reference Gist and Mitchell1992). Research has also suggested that as employees encounter aggressive leadership behaviors, those who view themselves and their abilities more positively are more able to shield themselves from the negative impact of leadership aggression (e.g., Zhang, Kwan, Zhang, & Wu, Reference Zhang, Kwan, Zhang and Wu2014). These individuals are also likely to believe that others within the organization view them in a favorable light and, thus, even when supervisors engage in social undermining toward them, they would see little value in making coworkers look bad. Moreover, employees who view themselves positively attempt to maintain a positive workplace environment because it is consistent with their positive self-image (e.g., Chang, Ferris, Johnson, Rosen, & Tan, Reference Chang, Ferris, Johnson, Rosen and Tan2012). This research is also consistent with the idea that those with a higher self-image tend to focus more on the bright side of their job and cope better with negative feedback from supervisors (Harris, Harvey, & Kacmar, Reference Harris, Harvey and Kacmar2009; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Kwan, Zhang and Wu2014). Recently, research has also alluded to the notion that employees who are better performers, believe in their own abilities and competence, and have a higher self-image are less likely to resort to aggressive or social undermining behaviors (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012; Eissa & Wyland, Reference Eissa and Wyland2016). These research findings support our contention that employees with higher levels of self-efficacy are less likely to be impacted by supervisor social undermining and are less likely to feel the need to undermine their coworkers by modeling the behaviors of their supervisors.

In contrast, those with low self-efficacy may not have autonomy or a sense of control in relation to their job performance that allows them to believe they can manage difficult situations (Bandura, Reference Bandura2012). Therefore, they are more likely to seek other avenues for achieving valued outcomes. Coworker social undermining may be a viable option because it could help elevate their own standing in the organization by making others look bad (Eissa & Wyland, Reference Eissa and Wyland2016). By belittling coworkers’ ideas or undermining their effort to be successful, perpetrators of social undermining may be viewed more favorably in the organization. This is especially likely to occur when supervisors are already communicating that these behaviors are acceptable by exhibiting similar behaviors. In this vein, when coupled with supervisor social undermining, individuals with low self-efficacy may be more likely to resort to undermining coworkers because they have less assurance in their competence to attain successful outcomes on their own, believing that their supervisors endorse such behaviors. Thus, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 3: Employee self-efficacy moderates the relationship between supervisor social undermining and coworker social undermining such that this relationship is weaker when employee self-efficacy is high as opposed to low.

METHOD

Sample and procedure

To test our hypothesized theoretical model, we invited ~500 employees in various large information technology and mid-level financial organizations in India to participate in the current study. These organizations were from various cities including Delhi, Bangalore, Kolkata, Pune, Mumbai, and Hyderabad. All of the data were collected via the internet through a secured website. Targeted emails containing a link to an online survey were sent to all participants whose names appeared on the rolls of a database maintained by a large Indian Business School. Whereas participation was entirely voluntary, upon accessing the survey, participants were assured that all responses were anonymous and confidential and that the study was being conducted for research purposes only. Finally, all original English scales were used in the survey. All participants were part of a workforce where English is the first language for the work being carried out and were proficient in the English language. A total of 350 responses were received from the participants; however, due to missing data only 331 responses were used for further data analysis. The final sample size generated a response rate of 66.2%. Employees were 69.3% male, 97.3% were employed full-time, had an average age of 28.64 years (SD=8.24) ranging from 20 to 63 years, and had an average organizational tenure of 4.43 years (SD=5.99). The vast majority of participates were Indians, reflecting an Indian ethnic composition.

Measures

Supervisor social undermining

Supervisor social undermining was measured using the 13 items from Duffy, Ganster, and Pagon (Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002) scale of supervisor social undermining. Participants were asked to rate how frequently their immediate supervisors had engaged in a number of behaviors. Sample items included ‘Hurt your feelings,’ and ‘Belittled you or your ideas’ (1=‘never,’ to 7=‘always’) (α=0.95). This scale has displayed adequate reliability (Cronbach’s α above 0.7) in previous studies (e.g., Duffy, Ganster, Shaw, Johnson, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster, Shaw, Johnson and Pagon2006).

BLM

BLM was measured using the four items from Greenbaum, Mawritz, and Eissa (Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012) scale of employee BLM. Participants were asked to rate their own BLM by specifying how strongly they agreed with a number of statements. Sample items included ‘I treat the bottom line as more important than anything else,’ and ‘I only care about the business’ (1=‘strongly disagree,’ to 7=‘strongly agree’) (α=0.75). This scale has displayed adequate reliability in previous studies (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012).

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was measured using the three items from Spreitzer’s (Reference Spreitzer1995) scale of employee self-efficacy (viz., competence). Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed to a number of statements. Sample items included ‘I am confident about my ability to do my job,’ and ‘I have mastered the skills necessary for my job competence’ (1=‘strongly disagree,’ to 7=‘strongly agree’) (α=0.86). This scale has displayed adequate reliability in previous studies (e.g., Spell, Eby, & Vandenberg, Reference Spell, Eby and Vandenberg2014).

Coworker social undermining

Coworker social undermining was measured using the same 13 items that were used for supervisor social undermining. The items originated from Duffy, Ganster, and Pagon (Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002). Participants were asked to rate how frequently they engaged in a number of behaviors toward their coworkers. Sample items included ‘Spread rumors about them,’ and ‘Delayed work to make them look bad or slow them down’ (1=‘never,’ to 7=‘always,’) (α=0.97). This scale has displayed adequate reliability in previous studies (e.g., Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002).

Control variables

We wanted to rule out other alternative explanations for our model by specifically controlling for variables that might have an impact on coworker social undermining. For example, we accounted for the organizational culture of justice. Prior research has shown that justice plays a key role in employees’ engagement in counterproductive work behavior (e.g., Ambrose & Schminke, Reference Ambrose and Schminke2009). Hence, we controlled for perceived overall justice (POJ). This is also in line with extant research that controlled for justice in testing social undermining models (e.g., Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002). POJ was measured with six items from Ambrose and Schminke’s (Reference Ambrose and Schminke2009) scale of POJ. Sample items include ‘Overall, I’m treated fairly by my organization,’ and ‘In general, I can count on this organization to be fair’ (1=‘strongly disagree,’ 7=‘strongly agree’) (α=0.78). Furthermore, in line with research on social undermining, we wanted to account for employee personality as it may impact their engagement in counterproductive work behavior as well. Thus, in line with Greenbaum, Mawritz, and Eissa (Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012) we also controlled for employee agreeableness to rule out this possibility. We measured agreeableness using one item taken from Gosling, Rentfrow, and Swann’s (Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swan2003) brief measure of the Big Five personality traits that captures agreeableness (i.e., ‘I see myself as sympathetic, warm,’ 1=‘strongly disagree,’ 7=‘strongly agree’). Lastly, employee age, gender (0=female, 1=male), and organizational tenure were used as control variables; however, our results have not been influenced by including them, so they were removed from our analyses.

RESULTS

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to examine the distinctiveness of the variables of the study. The measurement model consisted of five factors including supervisor social undermining, coworker social undermining, BLM, self-efficacy, and POJ. We compared the proposed five-factor model with models containing four factors (combining scale items of the moderators), three factors (combining scale items of the moderators and POJ), two factors (combining scale items of the moderators, POJ, and coworker social undermining), and one factor (where all scale items loaded on one factor). The results for the five-factor model provided a good fit (χ2(692)=1,843.86, p<.01; comparative fit index (CFI)= 0.89; root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA)=0.07). Moreover, the five-factor model had a better fit compared to the model with four factors (χ2(696)=2,137.02, p<.01; CFI=0.86; RMSEA=0.08), three factors (χ2(699)=2,588.35, p<.01; CFI=0.82; RMSEA=0.09), two factors (χ2(701)=3,539.20, p<.01; CFI=0.73; RMSEA=0.11), and one factor (χ 2 (702)=5,860.53, p<.01; CFI=0.51; RMSEA=0.15). A change in χ2 test also showed that the five-factor model had a significant improvement in χ2 over the four-factor model (Δχ2(4)=293.16, p<.01), three-factor model (Δχ2(7)=744.49, p<.01), two-factor model (Δχ2(9)=1,695.34, p<.01), and single-factor model (Δχ2(10)=4,016.67, p<.01). There results provide evidence for the distinctiveness of the variables in our study (e.g., Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003).

Analytical strategy and descriptive statistics

To test our full moderated model, we followed a method suggested by Hayes (Reference Hayes2013). We specifically utilized the SPSS macro developed by Hayes (Reference Hayes2013) for running various analyses. First, we ran our model two times by including each of the moderators separately (BLM, self-efficacy). We then ran our full model by including both moderators concurrently in the same regression equation to provide a more parsimonious test for our theoretical model. Lastly, all continuous variables were centered before hypotheses testing (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991). The means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the study variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and study variable intercorrelations

Note. N=331.

**p<.01.

Hypotheses testing

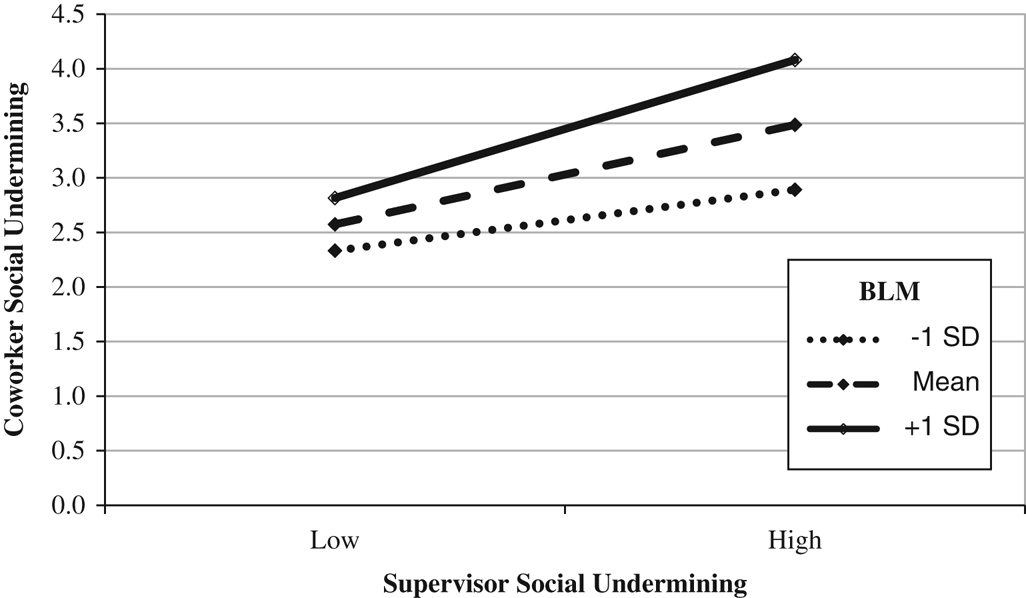

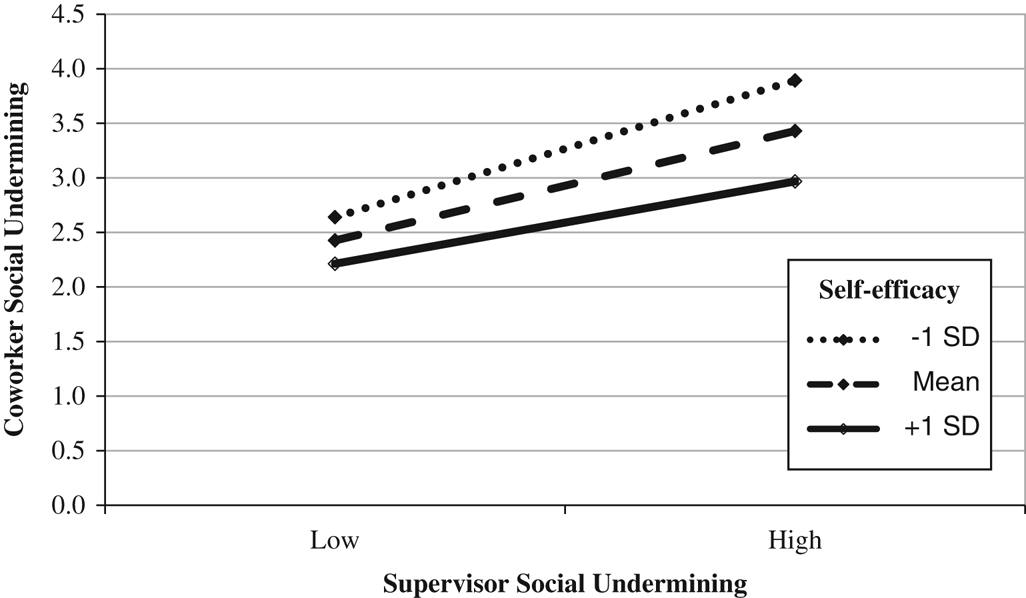

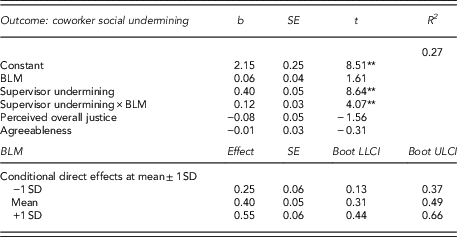

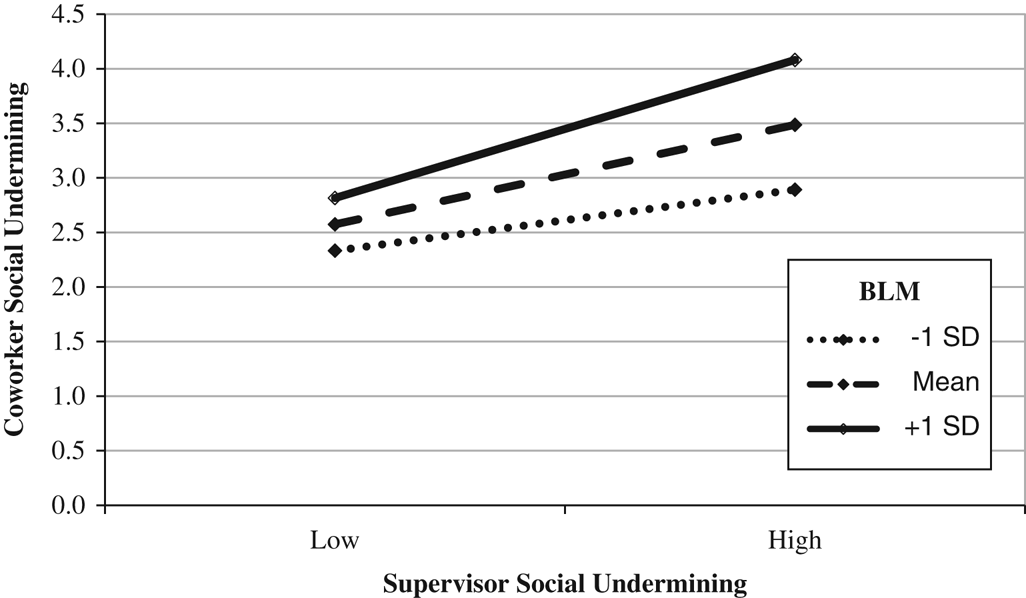

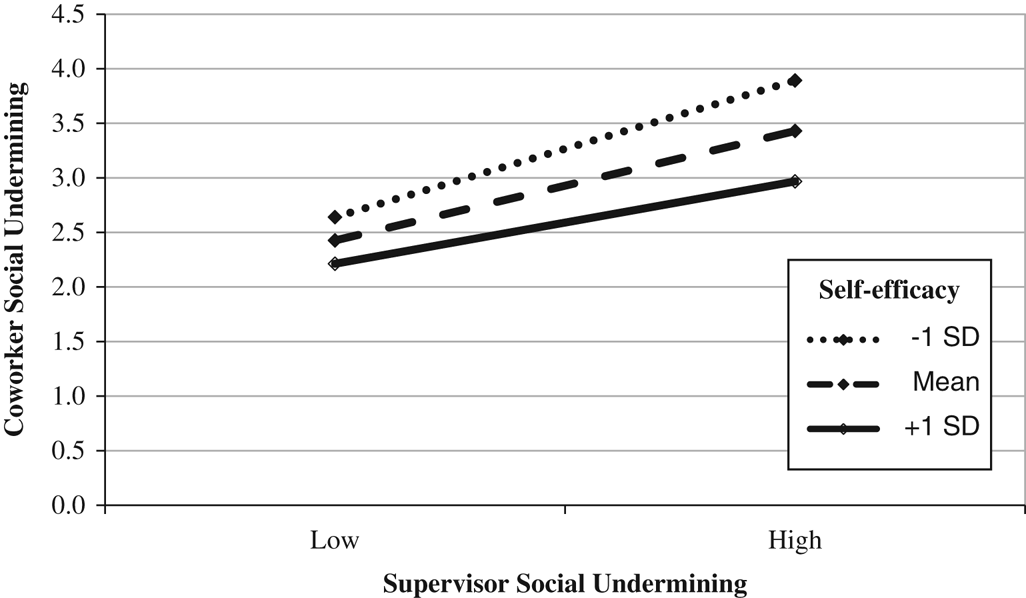

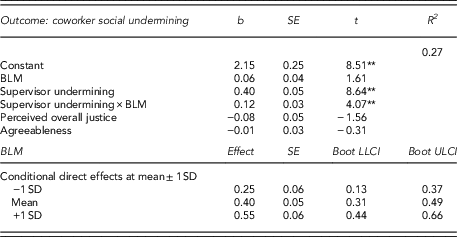

Results shown in Tables 2a and 2b demonstrate that supervisor social undermining was positively related to coworker social undermining for the models with employee BLM (b=0.40, t=8.64, p<.01) and employee self-efficacy (b=0.44, t=9.24, p<.01). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Tables 2a and 2b also provide results for the moderation hypotheses. As indicated in Table 2a, employee BLM moderated the relationship between supervisor social undermining and coworker social undermining (b=0.12, t=4.07, p<.01). This relationship was stronger when BLM was higher. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. Similarly, results from Table 2b show that employee self-efficacy moderated the relationship between supervisor social undermining and coworker social undermining (b=−0.10, t=−2.30, p<.05). This relationship was weaker when self-efficacy was higher. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported. We also plotted the simple slopes (Figures 2 and 3) for employee BLM and self-efficacy at three different levels of the moderators (1 SD above the mean, at the mean, and 1 SD below the mean). As shown in these figures, the slope for the supervisor–coworker social undermining relationship was stronger for employees with a high BLM (t=9.85, p<.01), but weaker for those with a low BLM (t=4.04, p<.01). Conversely, the slope for the supervisor–coworker social undermining relationship was stronger for employees with low self-efficacy (t=7.68, p<.01), but weaker for those with high self-efficacy (t=5.37, p<.01). We also examined the conditional direct effects of supervisor social undermining on coworker social undermining at 1 SD above the mean, at the mean, and 1 SD below the mean as shown in Hayes’ (Reference Hayes2013) macro. The results indicate that these effects were significantly different from 0 at all three levels but became stronger at 1 SD above the mean for BLM (Table 2a) and at 1 SD below the mean for self-efficacy (Table 2b). These results provide stronger support for the moderating patterns as proposed in Hypotheses 2 and 3.

Figure 2 Interaction of supervisor social undermining and bottom-line mentality (BLM) on coworker social undermining

Figure 3 Interaction of supervisor social undermining and self-efficacy on coworker social undermining

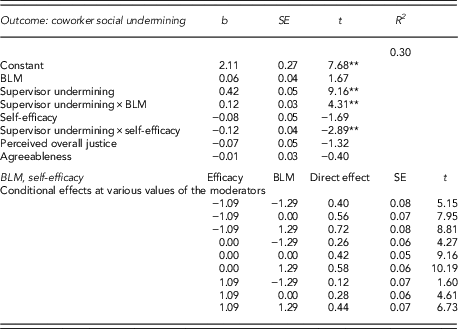

Table 2a Bottom-line mentality (BLM): regression results for testing moderation

Note. N=331. Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Bootstrap sample size=5,000.

CI=confidence interval; LL=lower limit; UL=upper limit.

**p<.01.

Table 2b Self-efficacy: regression results for testing moderation

Note. N=331. Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Bootstrap sample size=5,000.

CI=confidence interval; LL=lower limit; UL=upper limit.

*p<.05, **p<.01.

We ran the entire hypothesized model by including both of the moderators concurrently in the same regression equation as indicated in Table 3. In line with Hypothesis 1, supervisor social undermining was positively related to coworker social undermining (b=0.42, t=9.16, p<.01). Likewise, both BLM (b=0.12, t=4.31, p<.01) and self-efficacy (b=−0.12, t=−2.89, p<.01) moderated the direct relationship between supervisor social undermining and coworker social undermining in the expected direction, thus providing further support for Hypotheses 2 and 3. Table 3 also reveals the conditional direct effect of supervisor social undermining on coworker social undermining at various levels of these moderators combined. As predicted, the supervisor–coworker social undermining relationship was strongest at higher levels of BLM and at lower levels of self-efficacy simultaneously (direct effect=0.72, t=8.81, p<.001). These results provide further support to our full hypothesized model as depicted in Figure 1.

Table 3 Bottom-line mentality (BLM) and self-efficacy: regression results for overall model

Note. N=331. Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Bootstrap sample size=5,000.

CI=confidence interval; LL=lower limit; UL=upper limit.

**p<.01.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first theoretical research effort to present and test a trickle-down effect model of supervisor social undermining to coworker social undermining. We drew from SCT (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986, Reference Bandura2012) and the literature pertaining to social undermining (Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002), BLM (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1988; Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012) and self-efficacy (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986, Reference Bandura1997, Reference Bandura2012; Stajkovic & Luthans, Reference Stajkovic and Luthans1998; Bandura & Locke, Reference Bandura and Locke2003) to explain the circumstances under which supervisor social undermining encourages employees to engage in similar undermining behaviors toward coworkers. Our findings fully support our contentions. We predicted that the social undermining behaviors of supervisors are likely to be emulated by their subordinates and, thus, found a positive effect of supervisor social undermining on coworker social undermining. Moreover, we predicted that certain situations are likely to either enhance or diminish this relationship. Our findings suggest that a high BLM strengthened the positive effect of the supervisor–coworker social undermining relationship, whereas high self-efficacy buffered this relationship. Therefore, our results support a trickle-down effect of social undermining as well as provide support for the roles of both BLM and self-efficacy in impacting the strength of our trickle-down model.

Theoretical implications

Our research makes a number of vital contributions to the management and organization literature. First, in line with recent research on the trickle-down effects, our study examines a model that explains why employees may react to supervisor social undermining by targeting coworkers as recipients of similar social undermining behaviors. We argued that, in addition to seeking guidance from supervisors about acceptable behaviors, employees may actually align their behaviors to match the behaviors of their supervisors (e.g., Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Mawritz, et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012). Employees often view supervisors as credible role models because of their assigned organizational position (Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005; Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). As a result, supervisors who engage in social undermining signal to employees that these behaviors are acceptable. In response, employees may engage in similar social undermining behaviors. Yet, employees often choose to avoid reacting against supervisors for fear of punishment or loss of rewards. Therefore, coworkers become more viable targets for social undermining. Research pertaining to SCT provided the theoretical foundation for our trickle-down model (e.g., Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986, Reference Bandura2012; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). In this way, our research contributes to the limited research on trickle-down effects of negative forms of leadership – which also answers a research call for an examination of such effects as a link of social interactions (e.g., Andersson & Pearson, Reference Andersson and Pearson1999).

Second, while previous research provides support for the notion that coworker social undermining is detrimental to interpersonal relationships and the organizational environment (Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002), research exploring antecedents of coworker social undermining is still limited, yet regularly requested by researchers (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). Thus, our study provides insight into the coworker social undermining literature by exploring a potential antecedent. In particular, and in accordance with SCT (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986), our trickle-down model allowed us to examine the notion that employees typically look to credible role models at work, for examples, of behaviors that are deemed appropriate and, thus, we identified supervisor social undermining as an antecedent of coworker social undermining. In this way, we contribute to the growing research on coworker social undermining by providing arguments and empirical support for a specific theoretically plausible antecedent.

Additionally, our study contributes to the limited research examining moderators of the negative behaviors related to trickle-down effects (e.g., Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012). We supported our contention that employee BLM and self-efficacy moderated the relationship between supervisor social undermining and coworker social undermining. When employees believed they were socially undermined by their supervisors, those with higher levels of BLM were more inclined to turn around and socially undermine their coworkers as well. On the other hand, those with higher levels of self-efficacy were less inclined than those with low self-efficacy to socially undermine coworkers. Thus, we not only explain why but also when the relationship between supervisor and coworker social undermining is likely enhanced or diminished.

Practical implications

The results from this research also provide implications for practice. Social undermining is costly and is associated with several negative consequences within the workplace (e.g., Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002). To remain successful, organizations must take serious steps to prevent such behaviors. Our findings suggests that organizations need to pay particular attention to workplace social and interpersonal relationships that may encourage employees to engage in social undermining. The results from this study suggest that organizations need to be aware that employees may emulate supervisors’ social undermining behaviors. Given the positive association between supervisor social undermining and coworker social undermining, interventions and efforts to reduce supervisor social undermining should be fruitful. For example, organizations could make efforts to assist and train supervisors for appropriate workplace behaviors while further communicating clear expectations and policies pertaining to social undermining. Duffy, Ganster, and Pagon (Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002) suggested that organizational leaders must communicate the costs associated with these negative workplace behaviors and develop zero-tolerance policies for mistreatment. The findings from our study provide further support for these types of policies.

This research also has managerial implications for reducing counterproductive work behaviors. Results suggest that high levels of employee BLM increase the effect of supervisor social undermining on coworker social undermining. These findings help support calls from previous researchers (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012) for initiatives that discourage a unidimensional focus on the bottom line and, rather, encourage a multidimensional perspective for social, environmental, and financial performance (known as triple-line mentality; Waddock, Bodwell, & Graves, Reference Waddock, Bodwell and Graves2002). Organizational selection and on-boarding processes could be designed to attract candidates and employees who have a multidimensional mentality. Thus, organizations could clearly communicate their priorities during the recruitment, selection, and on-boarding stages to discourage BLM.

Furthermore, this research has practical implications for organizational leaders who are developing training initiatives. Given that our findings indicate that employee high self-efficacy buffered the trickle-down effect of supervisor social undermining on coworker social undermining, organizations could focus selection and hiring procedures on employing candidates who possess high self-efficacy. Research suggests that resources beget future resources (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1988, Reference Hobfoll1989). Therefore, organizations could provide social-support resources and training initiatives that focus on both increasing and maintaining employees’ confidence and overall competence in the workplace. Our findings regarding self-efficacy are also consistent with research suggesting that a positive image of one’s self and ability not only contributes to a successful job performance (e.g., Stajkovic & Luthans, Reference Stajkovic and Luthans1998), but is also likely to deter individuals from engaging in dysfunctional and counterproductive work behaviors including social undermining (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012).

Limitations and future research

Social undermining research is still in the early stages of development. The current study provides a number of notable insights into this emerging literature. Yet, our study has a number of limitations and also raises a number of opportunities for future research. First, our study has utilized self-reported measures, which may raise concerns of common method bias. Yet, we were quite careful to address this limitation. We followed various recommendations presented by Podsakoff et al. (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003) to minimize such concern. First, we conducted the Harman’s single-factor test (viz., confirmatory factor analysis), which supported the distinctiveness of our measures and showed evidence that common method bias may not present an issue in our data. Second, we ensured all participants’ anonymity and confidentiality in completing the surveys. Finally, the questions in our survey did not contain answers that were deemed ‘right’ or ‘wrong.’ These precautionary steps make us believe that common method bias and social desirability may not pose a concern (see Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Relatedly, although the use of multisource data helps reduce common method bias, the use of self-reported measures is consistent with existing research examining similar patterns of leader–subordinate aggressive behaviors (see Mitchell & Ambrose, Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2007). Specifically, research recommends that counterproductive work behaviors directed at coworkers might not be visible to supervisors. Therefore, ‘employees would be a better judge …’ (Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012: 350). In following this recommendation, our study includes a self-report measure of coworker social undermining. However, counter to previous recommendations, our measure of supervisor social undermining was assessed by subordinates and not by supervisors, which is a limitation of our study. Therefore, although it is difficult to execute, we believe it would be beneficial for future research to examine our model by using self-report measures from supervisors. Overall, it is worth noting that common method bias may not present a significant concern (see Spector, Reference Spector1987, Reference Spector2006; Doty & Glick, Reference Doty and Glick1998), especially when research utilizes well-designed measures such as ours. However, we are unable to conclusively rule out concerns related to self-reported measures that must be addressed by future research.

Second, consistent with previous research on trickle-down models (e.g., Aryee et al., Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012), our well-documented theoretical foundation leads us to propose a trickle-down effect of supervisor to coworker social undermining. Yet, due to the cross-sectional nature of our data, we are only able to present a plausible direction for this relationship, rather than confirm the directionality of the relationship. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility of a different pattern of relationships, whereby employees’ social undermining behaviors influence supervisors’ social undermining behaviors. As argued by Greenbaum, Mawritz, and Eissa (Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012), this pattern of variables is less likely due to organizational positions and formal power. Specifically, supervisors have control over rewards and punishments (e.g., Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012) and, thus, it may be risky for employees to target social undermining behaviors toward supervisors. Nonetheless, we cannot entirely eliminate the notion that an ‘upward’ flow of behavior exists, whereby behavior displayed by lower level employees influences behavior displayed by employees at higher levels in the organization (e.g., Yukl & Falbe, Reference Yukl and Falbe1990, Reference Yukl and Falbe1991). Therefore, to support the direction of our model, future researchers could collect longitudinal data, explore experimental designs, and examine the possibility that employees may direct their social undermining behaviors toward other targets (e.g., spouses).

Third, to develop our model, we followed previous SCT researchers (Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012), who relied on the theoretical assumption of SCT theory, which posits that employees are likely to look to others as role models of appropriate behaviors (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986). Therefore, our hypotheses were also founded on the assumption that role modeling is the process through which supervisor social undermining relates to coworker social undermining. Nonetheless, we did not operationalize and measure these role modeling processes in order to confirm this process. In fact, as shown in Table 1, we found a moderate correlation in the supervisor–coworker social undermining relationship (r=0.48), indicating that there may be potential mediators that further explain this association. Future research may benefit from directly measuring role modeling and other potential mediating mechanisms through which supervisor social undermining may be related to coworker social undermining. A potential mechanism that may also explain the proposed trickle-down effect is ‘relationship conflict.’ The social exchange literature (e.g., Blau, Reference Blau1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, Reference Cropanzano and Mitchell2005) and principles of reciprocity (Gouldner, Reference Gouldner1960) suggest that people may behave negatively toward each other when they do not maintain positive interpersonal relationships. Previous researchers have included relationship conflict as a mediator in the mistreatment literature (e.g., Eissa & Wyland, Reference Eissa and Wyland2016). Hence, an examination of various mechanisms, such as role modeling or relationship conflict, may provide valuable insight into the trickle-down effects such as ours. In this fashion, our current study serves as an outset for examining trickle-down models of social undermining.

While we also uncovered two boundary conditions of the supervisor to coworker social undermining relationship, there are other possible moderating variables that may influence this association. We selected variables (BLM and self-efficacy) that are relevant to the perpetrator (subordinate) who engaged in social undermining behaviors. Research has suggested that both of these variables may be connected to social undermining (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012). However, a logical avenue of future research is to examine other moderating variables, especially those that are relevant to ‘organizational culture,’ as it can largely influence employees’ attitudes and behaviors within organizations – depending on the specific type of the culture. For example, one question that our findings prompt is whether BLM infused within organizational norms and practices may actually influence the transfer of social undermining behaviors within the organization, which could further explain our model. On the other hand, when employees are immersed in an ethical organizational culture, they may be less likely to emulate a supervisor’s negative behaviors because such behaviors may not be commonplace in the organization. Other examples include a culture of hostility, which prompts employees to engage in counterproductive work behaviors, including coworker social undermining. To explain the influence of culture in relation to our model, as well as provide alternative theoretical explanations to our model, research could draw from theories such as attraction–selection–Attrition (Schneider, Reference Schneider1987; Schneider, Goldstein, & Smith, Reference Schneider, Goldstein and Smith1995) or social information processes (Salancik & Pfeffer, Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978). These theories explain that behavior is shaped by the behavior of others as well as by existing norms. Specifically, social information processes suggests that people look for cues in their work environment about appropriate behavior. Similarly, attraction–selection–attrition suggests that organizations attract and retain employees that fit or match the behavior and norms of existing employees. Future research could then examine these alternative theoretical explanations when examining our model, while also accounting for the role of culture.

In addition to the possible influence of organizational culture, future research should also investigate the role of personality in further examining our model. Personality may be important in predicting counterproductive work behaviors, including social undermining. For example, narcissism may strengthen the relationships proposed in our model. Individuals high on narcissism are self-absorbed, arrogant, and feel entitled (Michel & Bowling, Reference Michel and Bowling2013); therefore, they may be less empathetic toward coworkers and more likely to engage in social undermining behaviors. Indeed, previous scholars supported a relationship between the narcissism personality trait (Michel & Bowling, Reference Michel and Bowling2013) and counterproductive work behaviors. Ultimately, while it is expected that both culture and personality play key roles in explaining our proposed model, as noted above, we controlled for an organizational culture of justice as well as agreeableness to rule out the possible influence of these variables on the hypothesized relationships. Still, future research should thoroughly explore these variables in order to offer a different perspective in explaining our model.

It should be noted that the current study was also constrained by the limited number of research studies examining similar variables such as those presented in the proposed model. While this condition provides us with a theoretical strength, as being one of the first studies to examine the proposed relationships, our data have revealed some intriguing results that are worth mentioning. For example, in comparison to other research exploring BLM and social undermining (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012), we found no correlation between BLM and coworker social undermining (Table 1). This leads us to believe that social undermining, when assessed by different sources, could yield different results in relation to BLM. Future research would benefit from examining other theories and constructs measured by various sources to truly capture, understand, and extend the nomological network of BLM and social undermining. Moreover, while BLM and self-efficacy were positively and weakly correlated in our study, both moderators worked in different directions. As noted by Greenbaum, Mawritz, and Eissa (Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012), the BLM research arena is in its infancy and, hence, we are unable to make definitive conclusions regarding this relationship, particularly since we do not formally explore this relationship in the current study. Yet, we believe that future research investigating the relationship between BLM and several constructs (including self-efficacy) is merited.

Lastly, as previously mentioned, we applied SCT (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986) as a foundation for our hypotheses as presented in our trickle-down model of social undermining. However, SCT was developed in a Western context, whereas our data were originated in India. There is no compelling reason to assume that SCT would not likely be generalized to workplaces in India. However, an avenue for future research is to examine cross-cultural studies by replicating our findings using a sample population from various national cultures or perhaps use qualitative research studies to help develop theories specific to workplaces in India.

Conclusion

The current study suggests that employees differ in their behavioral reactions to supervisor social undermining. Given the emphasis for strong workplace social and interpersonal relationships, researchers and practitioners are increasingly concerned with these social undermining behaviors. The findings from this study support previous research assertions that employees often look to supervisors as role models for appropriate workplace attitudes and behaviors. This study also suggests that characteristics of the employees (e.g., BLM and self-efficacy) are also likely to shape whether they target their coworkers by emulating the supervisors’ social undermining behaviors. Based on these findings, future research examining ways to reduce BLM, increase self-efficacy, and reduce social undermining behaviors is necessary.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank three anonymous reviewers and the managing editor for their constructive comments on this manuscrip.