Introduction

The ritualisation of bodies of water through the subaquatic deposition of elaborate and often valuable offerings was a widespread practice in the past. Methodological developments in underwater archaeology have advanced the description, explanation and preservation of this fascinating heritage (Goggin Reference Goggin1960; Westerdahl Reference Westerdahl2005). In Europe, for example, many rivers, streams, underwater caves and kettle bogs have yielded evidence of the ritual deposition of pottery vessels, wooden objects, metal weapons, coins and even human sacrifices (e.g. Gaspari Reference Gaspari2003; Van der Sanden Reference Van der Sanden, Menotti and O'Sullivan2013; Billaud Reference Billaud and Campbell2017; Delaere & Warmenbol Reference Delaere, Warmenbol, Büster, Warmenbol and Mlekuž2019). In ancient Mesoamerica, offerings ranging from precious ornaments and ceremonial vessels to human remains have been frequently recovered from volcano lakes, cenotes (natural sinkholes) and artificially constructed reservoirs (e.g. Andrews & Corletta Reference Andrews and Corletta1995; Martínez-Carrillo et al. Reference Martínez-Carrillo, Solís, Bautista, Sánchez, Rodríguez-Ceja, Ortiz and Chávez-Lomelí2017). In this article, we address the significance of underwater offerings of precious artefacts made by the Inca in Lake Titicaca in the Andes.

The Inca Empire expanded rapidly throughout the Andes during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries AD (Rowe Reference Rowe and Steward1946; Moseley Reference Moseley2001; Stanish Reference Stanish2003; Yaeger & López Reference Yaeger, López, Alconini and Covey2018). One of its central places was Lake Titicaca, in a region not only important for its rich natural resources, high population densities and strategic location between two cordilleras (mountain chains), but also its sacred, cosmological significance (Bouysse-Cassagne Reference Bouysse-Cassagne1992; Albarracin-Jordan Reference Albarracin-Jordan1999; Arkush Reference Arkush, Stanish, Cohen and Aldenderfer2006; Tantaleán & Flores Reference Tantaleán, Blanco, Blanco and Tantaleán2012). The Incas claimed Lake Titicaca as their place of origin both symbolically and physically, within a logic of legitimation focused on strengthening the empire's new and expanding power (Bauer & Stanish Reference Bauer and Stanish2001). Although the timing of the Inca expansion is still debated (e.g. Pärssinen & Siiriäinen Reference Pärssinen and Siiriäinen1997; Bray et al. Reference Bray, Farfán, Ticona and Chávez2019), various early Spanish chroniclers, including Pedro Cieza de León, who visited the region in 1548, record two phases of expansion into the Lake Titicaca region (Cieza de León Reference Cieza de León1984 [1553]). The first (c. AD 1400–1440) consisted of the military campaign and territorial conquest led by Inca Viracocha. The second (c. AD 1440–1532) was undertaken by his son, Inca Pachacuti, and featured the consolidation of power by transforming the large Island of the Sun (14.3km2) into a major ceremonial complex through the construction of a series of temples, shrines and roads, and the promotion of ritual pilgrimage (Stanish & Bauer Reference Stanish and Bauer2004). At the core of this complex was the Sacred Rock, the mythical location from which the primordial couple, Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo, and their siblings emerged, and later founded Cuzco, the capital of the Inca Empire (Pärssinen Reference Pärssinen2005).

The ritual activities carried out on the Island of the Sun included underwater offerings (Reinhard Reference Reinhard and Saunders1992). Archaeological evidence attesting to the existence of such remains was first discovered in 1977, when a group of amateur Japanese divers came across a series of submerged offerings near the Khoa reef, located to the north-west of the Island of the Sun. Subsequent investigations of this reef by professional diving expeditions between 1988 and 1992 yielded a wealth of pre-Inca and Inca ritual offerings consisting of stone boxes containing miniature figurines made of gold, silver and Spondylus shell (Ponce Sanginés et al. Reference Ponce Sanginés, Reinhard, Ortiz, Siñanis and Ticlla1992; Reinhard Reference Reinhard and Saunders1992). More recent underwater excavations at this location have confirmed the importance of this reef as a subaquatic ceremonial locus during the expansion of the pre-Inca Tiwanaku State (AD 800–1000) (Delaere Reference Delaere2016; Delaere et al. Reference Delaere, Capriles and Stanish2019). Given the fluctuations of Lake Titicaca's level over time (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Binford, Brenner and Kelts1997; Weide et al. Reference Weide, Fritz, Hastorf, Bruno, Baker, Guedron and Salenbien2017), there must be a wealth of archaeological sites below the current waterline, but, at the time of the Khoa expeditions, the Khoa reef was the only known underwater offering site.

The K'akaya reef and the underwater context of an Inca offering

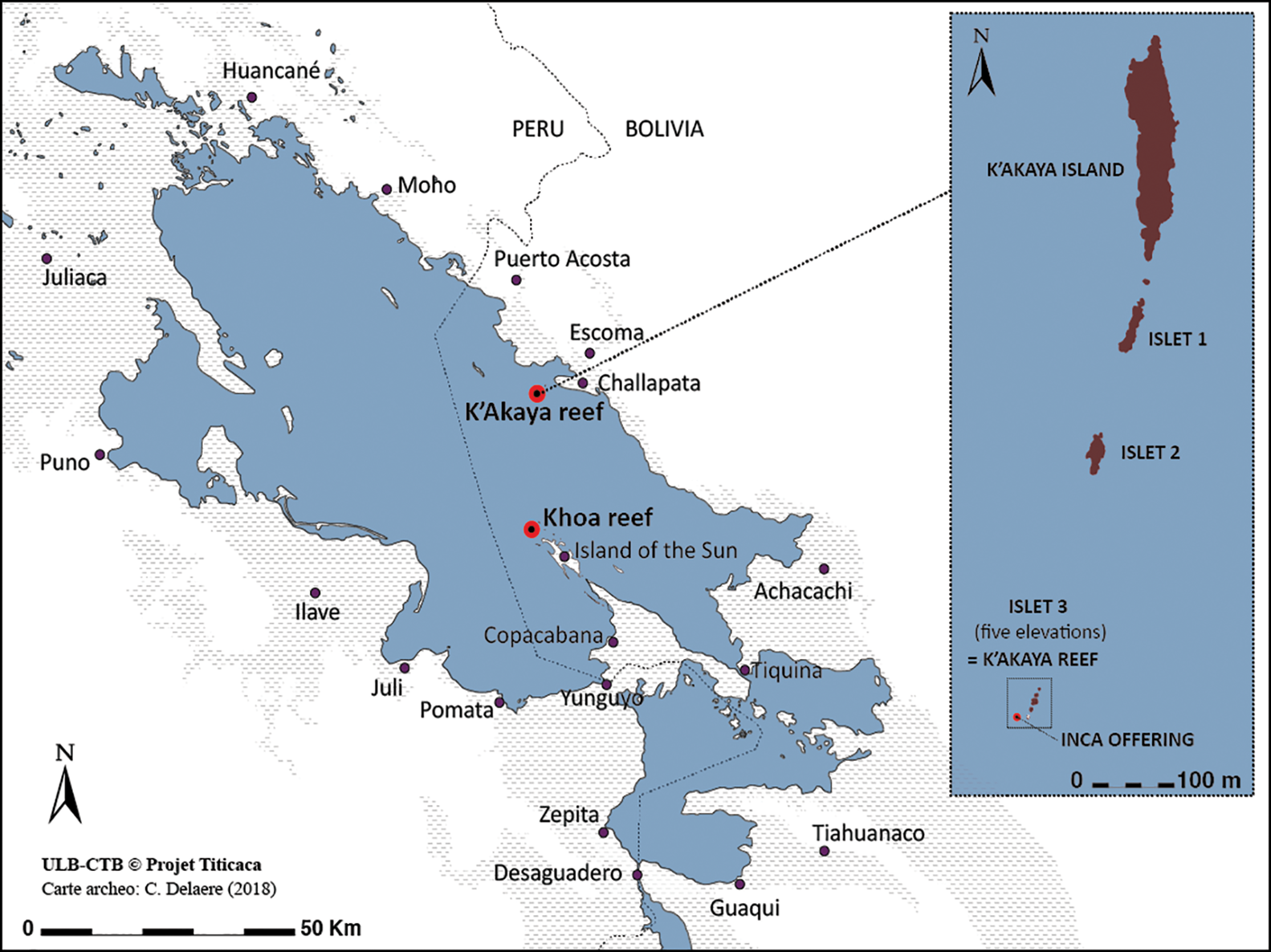

Since 2012, the Université libre de Bruxelles has conducted a research programme that aims to locate and document the underwater heritage of Lake Titicaca and to characterise and study this rich heritage. As part of this work, our team has surveyed systematically around the islands and reefs on the Bolivian (southern and eastern) side of Lake Titicaca, including the K'akaya archipelago in 2014. K'akaya (also known as Kakata or Kakawy) is located to the west of Lake Titicaca's Escoma Bay, and comprises a main island to the north (K'akaya Island) and three small islets to the south (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study area showing Lake Titicaca, including the K'hoa and the K'akaya reefs (figure by C. Delaere).

The K'akaya reef is the last of the three small islets; it has an inclination of 35° to the west, and is composed of different rocky reddish sandstone peaks jutting between 0.50 and 2m above the current lake level (3810m asl). The islet's peaks are covered in the white excrement of cormorants, gulls and various aquatic birds that find refuge and nest there. Sandstone reefs outcrop through the sandy fluvial sediments of the Challapata fan deposited by the Suches and the Yanariku Rivers. Historically, the reef has only been visited by Aymara and Uru fishermen who leave their gill nets overnight to capture killifishes and silversides, and who sometimes collect the guano for use as fertiliser (Portugal Loayza Reference Portugal Loayza2000).

The southernmost outcrop of the K'akaya reef lies entirely beneath the surface of the lake and is covered by aquatic vegetation. Here, our underwater surveys discovered an offering consisting of a large, isolated stone box placed on lake sediment to the south-west of the reef at a depth of 5.50–5.80m below lake level (Figure 2). Although the stone box was not buried in the sediment, a slight concretion of its lowest few centimetres suggests that it had not moved since its deposition. The surrounding sedimentary plateau was carefully surveyed, measuring 60 × 10m, beyond which it sloped to a depth of more than 8m. The only artefacts found were remains of recent (e.g. gill nets and stone anchors) and probably older (e.g. ballast stones) fishing activities. A small 1m2 sondage (unit 1), cut to verify the nature of the substratum, yielded no artefacts or cultural layers associated with the stone box (Figure 3).

Figure 2. View of the K'akaya reef and position of the offering (A) and location with respect to K'akaya Island (B); the offering in situ (C–D) (photographs by C. Delaere).

Figure 3. Schematic profile of the K'akaya reef, showing the location of the underwater offering in relation to the lake's surface (horizontal scale in metres, vertical scale in centimetres from the surface; figure by C. Delaere).

Before removing the box, we made a full photogrammetric record of the offering in situ. We then secured its cap with a gauze band and placed the stone box on a large plastic container for transport. Although the stone box was intact, its west-facing side was severely eroded, possibly due to exposure to the westward lake current during the dry season; its other faces were well preserved. We opened the stone box in our field laboratory in the presence of various municipal and local Indigenous community authorities.

The box was sculpted and polished from an andesite block measuring 0.36 × 0.27 × 0.17m (Figure 4). It had two ~30mm perforations and grooves on each of its short sides, which probably held ropes to lower the box from a boat or raft. A circular cavity, 100mm in diameter, located in the centre of its upper face was capped with a 70mm-thick andesite plug with a convex top. Although the cover was tightly sealed, it was not watertight, as approximately 60mm of compacted dark grey clayey-sandy lacustrine sediment, including a few small fish bones (post-offering), was found on the base of the cavity. Systematic removal and collection of the sediment for archival purposes revealed, at approximately 15–20mm from the bottom of the cavity, a cylindrical gold foil resting against a small camelid figurine made of shell. The rolled cylindrical gold sheet (25 × 13mm) included two small perforations. The camelid figurine (28 × 40 × 4mm) is made of Spondylus shell (mullu) (Figure 5). The figurine was placed flat with its outer (pink) side facing upwards, and the gold foil lay slightly above the figurine's front legs.

Figure 4. The stone box, its cap and contents, comprising a camelid figurine made of shell and a rolled gold foil (scale in centimetres; photograph by T. Seguin, Université libre de Bruxelles).

Figure 5. Camelid figurine made of Spondylus shell (28mm long) and rolled gold sheet (25mm long) (photograph by T. Seguin, Université libre de Bruxelles).

Discussion

The K'akaya offering strongly suggests an Inca affiliation and is remarkably similar to offerings made in the Khoa reef, as well as to artefacts recovered on other archaeologically documented Inca-affiliated ritual sites. At least 28 cylindrical, cube-shaped and composite stone boxes have been discovered in Khoa by various diving expeditions, but only four had partially preserved or intact contents (Ponce Sanginés et al. Reference Ponce Sanginés, Reinhard, Ortiz, Siñanis and Ticlla1992; Reinhard Reference Reinhard and Saunders1992; Delaere Reference Delaere2016, Reference Delaerein press). These four boxes contained miniature male, female and camelid figurines made of gold, silver and Spondylus shell. The figurines were probably fully clothed with elaborate polychrome textiles and featherwork, as suggested by the presence of metallic tupu pins and diadems in at least two boxes, and by their similarity to Inca ritual assemblages documented elsewhere in the Andes (e.g. Dransart Reference Dransart1995; Sagárnaga Reference Sagárnaga1997; Reinhard Reference Reinhard2005; Bray Reference Bray2009; Reinhard & Ceruti Reference Reinhard and Ceruti2010; King Reference King2012; Besom Reference Besom2013).

The K'akaya box seems to belong to the same manufacturing tradition as those found in Khoa. Macroscopic observation suggests that the fine cut and polish of the stone is comparable, and, although geochemical sourcing is pending, the andesite used to manufacture the boxes is identical. Nevertheless, unlike the Khoa cube-shaped boxes that tend to be tall with quadrangular caps, the K'akaya box is rectangular, with a circular plug.

The two miniature offerings are also in typical Inca style. Figurines made from Spondylus shell, including at least one other camelid figurine, have also been recovered from the Khoa reef (Ponce Sanginés et al. Reference Ponce Sanginés, Reinhard, Ortiz, Siñanis and Ticlla1992). The rolled gold foil could represent a miniature version of a chipana—a bracelet usually worn by Inca noblemen on their right forearms (Besom Reference Besom2013: 269). Comparable miniature gold bracelets have been found in the Cuzco Valley in association with fragments of rolled gold and silver sheets (Andrushko et al. Reference Andrushko, Buzon, Gibaja, McEwan, Simonetti and Creaser2011: 328), as well as accompanying various Inca burials elsewhere (Reinhard & Ceruti Reference Reinhard and Ceruti2010; Besom Reference Besom2013).

The association of miniature camelid figurines with gold foil is also found in the Aconcagua and Llullaillaco mountain sanctuaries in the Argentinian-Chilean Andes, where other miniature figurines formed part of offerings associated with human immolations (Schobinger Reference Schobinger1999; Reinhard & Ceruti Reference Reinhard and Ceruti2010). These sacrifices represent clear archaeological evidence for the capacocha, an Inca ceremony involving the ritual immolation of children to significant huacas or deities to recognise, glorify and appease them (Ceruti Reference Ceruti2004; Reinhard Reference Reinhard2005; Mignone Reference Mignone2009; Besom Reference Besom2013). The best preserved and documented capacocha have been identified near the peaks of high mountains, although others have also been found on mountain slopes and lake shores and in caves (e.g. Reinhard Reference Reinhard2005; Mignone Reference Mignone2009; Besom Reference Besom2010). Inca child burials suggestive of capacocha rites, for instance, have been found in the Pumapunku pyramid of Tiwanaku, near the southern shore of Lake Titicaca (Yaeger & López Reference Yaeger, López, Alconini and Covey2018).

The worship attested in Khoa connects directly to the pilgrimage ceremonies associated with the Inca birthplace at the Island of the Sun. The seventeenth-century Augustinian cleric Alonso Ramos Gavilán (Reference Ramos Gavilán1860 [1621]: 43–44), for example, reports in his extensive monograph about the Inca rituals at Lake Titicaca that, near Apingüela Island, the blood of children and animals was placed in stone boxes and lowered from rafts into the lake with the aid of ropes. The lake water would turn red, as reflected in the term vilacota (from the Aymara language: wila red or blood, quta lake), presumably as the blood rose to the surface. It is certainly possible that blood was included in the stone boxes, and future residue analyses may verify this possibility.

Adolph Bandelier, who conducted extensive research on the Island of the Sun in the late nineteenth century, argued that:

the Island of Apingüila, on which Inca remains are said to exist, and its neighbour, Pampiti, where, it is alleged, Huayna Capac, the last of the Inca head chiefs, previous to Atahualpa and Huascar, performed fearful human sacrifices, are seen from Sicuyu in a line with the longitudinal axis of Titicaca [i.e. Island of the Sun] (Bandelier Reference Bandelier1910: 228–29).

The link between Ramos Gavilán's and Bandelier's accounts and the underwater archaeological discoveries made in the Khoa reef is strong. Nevertheless, the actual location of Apingüela and Vilacota may correspond to different places within the lake (Ponce Sanginés et al. Reference Ponce Sanginés, Reinhard, Ortiz, Siñanis and Ticlla1992). The use of these toponyms in two nineteenth-century maps, for instance, suggests that the current location of the K'akaya archipelago corresponds to an island near Apingüela called ‘Quitacota’ (Neveu-Lemaire Reference Neveu-Lemaire1906: 31 [1877]) or ‘Guilacota’ (Neveu-Lemaire Reference Neveu-Lemaire1906: 39 [1892]). Similarly, Bandelier (Reference Bandelier1910: 251) indicates that “Ramos […] only applies the name ‘Vilacota’ to portions of the lake around the two islands”, suggesting that Vilacota might not be a specific location but a place covered in blood or even a ceremony that featured the offering of blood to the lake.

The stone box offering at K'akaya illustrates a practice comparable to that observed in Khoa. Our careful survey of the entire reef confirms that the stone box represents a single, isolated event. The contents of the offering also suggest a more modest variant of the practice of underwater sacrifice. The gold cylinder could have served as a substitute for an actual anthropomorphic male figurine to complement a human-camelid dyad. References to attributes of power, such as a bracelet made of laminated gold foil, could ascribe the same symbolic value as do more elaborate figurines. Such sacrificial replacements have also been reported as part of underwater offerings made by present-day Aymara ritual specialists, who are known to make dolls and offer them to Lake Titicaca as sacrifices in times of poor weather (Vellard Reference Vellard1954).

Underwater excavations at Puncu on the southern shore of the Island of the Sun indicate that the lake level during the Inca period (after AD 1440) was the same as in 2014 (Delaere Reference Delaere2017). The present-day natural landscape was therefore comparable to that encountered by the Inca religious specialists during the offering ceremony. As at Khoa, the geomorphology of the K'akaya reef suggests that the Inca not only had to transport the offering to the site by boat or raft, but also that the ceremony itself was carried out from the vessel. The presence of two perforations on the lateral ends of the stone box suggests that it was lowered to the bottom of the lake using ropes, which either decomposed over time or were removed once the offering had been made. As the offering was on the western side of the reef, we speculate that during the offering ceremony, the person(s) who handled the vessel had to protect themselves from the wind and the prevailing currents from the east, which are characteristic of the summer, or rainy season (November to March) (Roche et al. Reference Roche, Bourges, Cortes, Mattos, Dejoux and Iltis1992; Ronchail et al. Reference Ronchail, Espinoza, Callède, Lavado, Pouilly, Lazzaro, Point and Aguirre2014).

The location and orientation of the K'akaya's offering seem deliberate. The K'akaya reef is almost directly north of Khoa, suggesting a strong spatial link between the two sites. To the east, the reef faces the snow-capped peaks of the Illampu and Janq'uma Mountains, both of which are visible from the lake. These are the tallest peaks in the Eastern Cordillera and were the most revered mountains of the Carabaya/Larecaja gold-rich area (Bouysse-Cassagne Reference Bouysse-Cassagne2017). It is not implausible that the gold cylinder could have been mounted on the camelid figurine as a representation of a llama caravan and its precious cargo, in commemoration of the incorporation of this gold-rich region in the Inca Empire (see Sillar Reference Sillar2009). We may further speculate that, given the resemblance of the reef to one of these peaks and the fact that rainfall originates in the Eastern Andes, the offering could have referred to the successful reproduction of the Inca and their herds by linking Lake Titicaca with the mountains of this productive region.

Conclusions

Lake Titicaca and its islands and reefs had privileged status within the Inca cultural and ritual landscape. The lake basin was under the direct political control of Cuzco and a powerful symbolic narrative placed the lake at the centre of the Inca founding myths. The Inca incorporation of Lake Titicaca and its consecration involved the construction of a ceremonial pilgrimage complex centred on the Island of the Sun, as well as the deposition of valuable underwater offerings. The stone boxes previously recovered from the Khoa reef suggest that these offerings once contained clothed miniature figurines made of precious materials, along with human blood (possibly). The Inca stone box newly discovered on the K'akaya reef—away from the Island of the Sun—enriches the discussion about the meaning and role that these offerings had for the expanding empire. The K'akaya offering supports the hypothesis that the entire lake was revered as a sacred huaca or deity. The ceremonial offerings made to the lake were both symbolic and political acts intended to legitimise the power of the Inca occupation of this sacred space by way of ritual. By symbolically and physically reclaiming these ritually charged places through ceremonies, such as the capacocha and vilacota, the Inca increased their prestige and legitimacy as divine sovereigns, while maintaining control over the cosmic order of the world.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Bolivian Ministry of Cultures and Tourism, as well as the municipality of Escoma and the Challapata and K'akaya community authorities. We would also like to thank everyone who has worked on the research project, especially our diving archaeologists and scientific collaborators: Marcial Medina Huanca (Co-Director of the Archaeological Research Project, Universidad Mayor de San Andrés), Peter Eeckhout (Université libre de Bruxelles), Stéphane Guédron (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Institut des Sciences de la Terre), Maria Filomena Guerra (CNRS, UMR 8096, Université Paris 1-Panthéon-Sorbonne), Bérenger Debrand Bonapetit, Fabrice Laurent, Laurent Masselin (cartographer), Pascal Laforest, Giorgio Spada, Teddy Seguin, Marie-Julie Declerck, Aline Huybrecht (Université libre de Bruxelles), Ruth Fontenla (Universidad Mayor de San Andrés), Eliana Flores Bedregal, Victor Plaza, Jean Triboulet (Laboratoire d'Informatique, de Robotique et de Microélectronique de Montpellier, UMR 5506), Julien Dez (Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives), Charles Stanish (University of South Florida) and the Wiener-Anspach Foundation.