The dimensionality of the political space in Europe has long been a focus of debate amongst scholars. While some authors are convinced that the left-right dimension remains the principal dimension that defines politics in Europe (Bartolini and Mair Reference Bartolini and Mair1990), others suggest a two-dimensional space that is framed by an economic dimension of free-market capitalism versus state regulation and a social dimension that pits libertarians against authoritarians (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kitschelt and McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995; Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006), or even a three-dimensional space that also incorporates a dimension relating either to EU integration (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) or to issues of group identity (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2013). While most studies into the dimensionality of the political space focus on the supply side of politics (i.e. political parties) (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012; Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006), the focus of this article is on the demand side, i.e. the orientations of ordinary voters.

The starting point will be the series of studies that draw from the Chapel Hill expert survey of political parties based at the University of North Carolina. This group of scholars first proposed two dimensions to describe the European political space: one economic (left-right) dimension and one cultural (TAN/GAL) dimension (Hooghe, Marks and Wilson Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006). Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) went on to propose a third dimension relating to European integration. While these models may adequately describe the supply side of politics, they have yet to be tested comprehensively on the demand side. With this end in mind, we test them on the political orientations of over half a million EU citizens who completed a survey administered via an online tool called a Voting Advice Application (VAA). We first attempt to replicate the findings of Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) on these data using their own predefined dimensions, before adopting a more inductive approach in order to identify the models (and dimensions) that best fit the data in each country.

We find that while certain key features of the political space that are identified in the supply-side studies are also revealed in demand-side studies, on the demand side there is greater heterogeneity between countries than supply-side studies suggest. While supply-side studies suggest that a single overarching dimensional model provides a ‘best fit’ solution in all countries, our own study suggests that on the demand side the dimensionality of the political space can only be generalized to relatively small clusters of countries. We also find that European issues do not, in most cases, form an independent dimension of their own, but may instead either cluster together with the cultural dimension or (more rarely) form a part of the economic dimension. Finally, we show that the issues that the Chapel Hill group of scholars label as TAN/GAL do not form a coherent scale in any European country if we base our analysis on demand-side data. In many cases the cultural dimension draws from ‘identity’ issues involving immigration and EU integration.

The rest of article will proceed as follows. The next two sections provide an overview of the literature relating to the dimensionality of the political space and set out the overall approach and aims of the article. The subsequent section describes the data source and methods used to identify latent ideological dimensions. Next, the results of the analysis are outlined and the extent to which the patterns observed confirm or contradict the expectations of supply-side studies are explained. The article ends with a discussion of the broader relevance of the findings and a brief conclusion.

The Dimensionality of the Political Space

In terms of the number of dimensions needed to define (or approximate a definition of) the European political space, the simplest model is a one-dimensional model defined by a single left-right dimension. In the twentieth century, left and right were used above all as a label for rival economic ideologies with the left favouring a state-directed economy and redistribution of wealth from the rich to the poor, and the right preferring a free-market economy unfettered by state control. With the emergence of the so-called ‘new politics’ in the late 1960s and 1970s, non-economic, ‘post-materialist’ values such as environmentalism, minority rights and freedom of lifestyle choices also became the object of political contestation (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1984). Some authors saw these values transforming the left-right dimension into ‘an amorphous vessel whose meaning varies in systematic ways with the underlying political and economic conditions in a given society’ (Huber and Inglehart Reference Huber and Inglehart1995, 90). Others, however, proposed that they constitute a separate ideological dimension.

Advocates of a two-dimensional political space hold that ‘new politics’ issues form a separate cultural dimension. Kitschelt refers to this second dimension as a libertarian-authoritarian dimension (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kitschelt and McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995), while Marks et al. admit that it ‘summarizes several non-economic issues – ecological, lifestyle, and communal – and is correspondingly more diverse than the Left/Right dimension’ (Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006, 157). Accordingly they assign it a rather complex label, TAN/GAL (an acronym for traditional-authoritarian-nationalist versus green-alternative-libertarian). According to this schema, which is used to define the positions of European political parties in the oft-cited Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES), the cultural dimension embraces issues involving personal lifestyle (such as gay marriage, abortion, euthanasia), law and order, the role of religion, immigration, multiculturalism and environmentalism (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Anna Vachudova2015). It exists alongside an economic dimension that embraces traditional left-right issues such as the role of the state in the economy, government spending, deregulation and redistribution of wealth.

There remains the question of how issues relating to EU integration fit into this dimensional structure. Drawing from CHES expert codings on the positions of all significant EU political parties on a range of issues in 2006, Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) use confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to show how the European political space – as defined by the supply side, i.e. the positions of political parties – best conforms to a three-dimensional model defined by an (economic) left-right dimension and a (cultural) TAN/GAL dimension, with EU issues forming a separate dimension sui generis. Costello et al., who also use a CFA model, find that a three-dimensional model works best when analysing policy congruence between voters and representatives in the European policy space. Specifically, they find ‘an economic left/right dimension, a cultural dimension (and) a dimension capturing attitudes towards the EU’ (Costello, Thomassen, and Rosema Reference Costello, Thomassen and Rosema2012, 1245).

While Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) suggest that a three-dimensional model best fits the data in all EU countries, they also show that these dimensions correlate strongly with one another in different directions in different countries. They find that in most Western European countries, the economic left-right dimension and the TAN/GAL dimension correlate in such a way that economically left-wing parties tend to be GAL, while economically right-wing parties tend to be TAN. In most (but not all) of post-communist Europe, however, a reverse correlation applies whereby economically left parties are more likely to be TAN and economically right parties GAL, partially confirming an earlier finding of Marks et al. (Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006). At the same time, Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) observe some heterogeneity amongst post-communist countries, with Hungary demonstrating the strongest associations between left and TAN on the one hand and right and GAL on the other, but with Estonia, Latvia and, most notably, Slovenia exhibiting the same pattern that is observed in (most) western European countries. Rovny suggests that this is because former communist parties in countries that had previously belonged to communist federations (the USSR and Yugoslavia) tend to represent ethnic minorities and are therefore more multiculturalist or ‘GAL’ in their orientation (Rovny Reference Rovny2014).

Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) also show that in most EU countries, economically right-wing parties tend to be more pro-EU than left-wing parties, although the correlation is weak in the original EU-6 and runs in the reverse direction in the UK, where economically right-wing parties tend to be more Eurosceptic than left wing-parties. Finally, they find that TAN parties tend to be more Eurosceptic and GAL parties more pro-EU, but this tendency does not apply in Estonia, Germany, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Sweden, where a reverse correlation seems to apply (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012).

The work of Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) draws from the 2006 CHES party codings and therefore their findings refer to Europe prior to the European debt crisis. According to Hooghe and Marks (Reference Hooghe and Marks2018), this crisis increased the salience of European integration as an issue and led to a rift between northern creditor countries and southern debtor countries in terms of political competition. While in the north culturally right-wing, Eurosceptic TAN parties have benefited, in the south resentment against austerity has led to a rise in radical (economic) left parties. In a similar vein, Otjes and Katsanidou (Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017) argue that after the European sovereign debt crisis ‘in the Southern European debtor states economic and European issues are merging as a result of a strong European interference in their economic policy’ (Otjes and Katsanidou Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017, 301), but that in Northern European countries issues of EU integration are associated with immigration and the cultural dimension of political competition.

Table 1 replicates Bakker et al.‘s correlations between economic left versus right, social left versus right (or TAN/GAL) and the European integration dimension in all EU member states using the 2014 CHES data.Footnote 1 Once again we observe that TAN parties tend to be more Eurosceptic in most countries, but this time we observe a rather clearer picture than that reported in Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) with strong correlations in this direction both for most northern European creditor countries and for post-communist countries with the exception of Slovenia. In the so-called ‘bail-out’ countries of Cyprus, Ireland, Portugal and Spain (so labelled because they were forced to accept a bail-out by international financial organizations in return for sharp cuts in government spending) – as well as in Slovenia, which imposed its own harsh austerity package in response to the debt crisis – GAL parties were generally less favourable to European integration than TAN parties. This would appear to support the above-mentioned arguments of Otjes and Katsanidou (Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017) and Hooghe and Marks (Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). Greece is the only bail-out country that appears to buck this trend, with the correlation running in the opposite direction. In terms of the correlations between the economic left-right dimension and the TAN/GAL dimension we still see the aforementioned divide between Western Europe and post-communist Europe, although by 2014 Poland, as well as Slovenia, corresponded more to a ‘Western’ model in which GAL is associated with the economic left and TAN with the economic right.

Table 1 Updated CHES correlations, 2014

But do these tendencies still hold if we shift our focus from the supply side (i.e. parties) to the demand side (i.e. potential voters)? Cleavage theory suggests that the dimensions that define the policy space correspond to fundamental divides in society that emerged as a result of the formation of modern nation states in Europe and subsequent systemic changes such as industrialization. Lipset and Rokkan propose that four societal cleavages – centre versus periphery, state versus church, land versus industry and owner versus worker – have been shaping patterns of political contestation in Europe since the nineteenth century (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). While the industrial revolution and the associated cleavage between owner and worker have meant that most European countries share a common economic left-right dimension, cleavage theory would suggest that the relevance and possibly the number of other dimensions will vary according to the different cleavage structures that engendered them.

Recent events have led to a revived interest in cleavage theory. Kriesi et al. contend that a new cleavage – that between ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of globalization – has, over recent years, transformed the political space in Europe, leading to the strategic repositioning of existing political parties and even the emergence of new ones (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). In a similar vein, Hooghe and Marks identify what they refer to as a ‘trasnational cleavage, which has as its core a political reaction against European integration and immigration’ (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, 109). The thrust of Hooghe and Marks’ argument is that cleavage structures continue to drive party system change today and identify the breakthrough of a radical right party in Germany as one of the most stunning consequences of the new cleavage (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, 110). If indeed it is demand that creates supply, we would expect that changes in the way ideological dimensions are configured on the demand side (i.e. at mass level) will drive any corresponding changes on the supply side (i.e. at the level of parties). This justifies the focus on this article on the former, rather than the latter.

If the proposed new cleavage does indeed represent a new and growing divide in European societies, we would expect the ideological divide that corresponds to it to encompass issues relating to the role of the nation state in response to globalization and Europeanization. Hooghe and Marks suggest that it is highly correlated with TAN/GAL (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, 123), but not all issues that are encapsulated in TAN/GAL are necessarily part of it. While nationalism is clearly its defining hallmark, green issues would only be relevant insofar as they relate to global regulation over environmental policy (such as the Paris Agreement on global warming), and issues of authority or law and order are not logically connected to this new divide. Kriesi et al. talk of a ‘transformation of the cultural dimension’ (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006, 950) through the incorporation into it of issues such as immigration and EU integration, and suggest the alternative label of (cultural) ‘demarcation’ versus ‘integration’ for this dimension. Since the decision of the United Kingdom to leave the European Union and the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States in 2016, journalists and political commentators have sometimes referred to this identity-based dimension as ‘open’ versus ‘closed’Footnote 2 or ‘people from somewhere’ versus ‘people from anywhere’ (Goodhart Reference Goodhart2017). Kitschelt distinguishes it from the libertarian-authoritarian aspects of TAN/GAL, proposing an alternative three-dimensional model that includes one economic left-right dimension, one libertarian-authoritarian dimension and one identity-based dimension that draws on issues of ethnicity, immigration and European integration (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2013).

It is quite possible that the new ‘transnational’ cleavage, like some of Lipset and Rokkan’s earlier cleavages, will manifest itself in different ways in different countries, especially in terms of the ideological conflicts it engenders. In particular, it is likely that the varying legacies of past policy choices, the relative strengths of different socio-economic groups in society and the state’s (differential) capacity for intervention mean that European policy makers are destined to respond to the systemic challenges of globalization and financial crisis in different ways (Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015a, Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann and Kriesi2015). The strategies they adopt will inevitably generate new political conflicts that will play out in different ways in different countries. The issue of European integration (see above), as well as mass and elite reactions to it, is perhaps a case in point here. As Otjes and Katsanidou (Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017) suggest, globalization and Europeanization may be seen through an economic lens in Southern European debtor countries, where externally imposed austerity policies bite hardest. In Northern European creditor countries, on the other hand, the new cleavage may be more likely to manifest itself as a cultural divide between ‘open’ and ‘closed’. The question we must address is therefore: Can we talk about a single European policy space when we look at the demand side of politics, or must we instead consider different European policy spaces?

Aims and Approach

To explain our aims in this article it is important to first outline existing approaches to the study of political dimensionality. De Vries and Marks (Reference De Vries and Marks2012) identify two approaches for theorizing dimensionality. The first is a strategic approach that considers the policy space and the latent dimensions that define it to be the result of a strategic struggle between political parties. Parties shape the policy space by determining whether or not a particular issue is salient (De Vries and Marks Reference De Vries and Marks2012, 187–8). This ‘top-down’ approach for identifying dimensions has variously involved analysing party manifestos (Stoll Reference Stoll2010), using expert surveys to position parties on certain broad issue areas (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012; Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006) or drawing from roll-call votes at the European Parliament (Hix, Noury, and Roland Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2006). The second approach identified is a sociological or ‘bottom-up’ one that assumes that political competition is based on historically embedded conflicts within society, an approach that goes back to Lipset and Rokkan’s (Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967) study of societal cleavages (De Vries and Marks Reference De Vries and Marks2012, 187). This approach typically draws on opinion surveys; an example is Henjak’s analysis of European Value Survey (EVS) and World Value Survey (WVS) opinion data to explore the effect of certain value orientations on party choice (Henjak Reference Henjak2010). Essentially this is a difference between supply-side and demand-side approaches. Given our interest in the possible emergence of a new cleavage that relates to transnationalism and globalization (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006) and the likelihood that this cleavage is bringing about a change in patterns of political competition, it is this second approach that we adopt in this article.

Both demand-side and supply-side approaches have their advantages and disadvantages. The supply-side approach and the use of expert codes to determine party positions is by far the best established method for exploring dimensionality and has delivered real and meaningful insights into the similarities and differences in patterns of party competition in Europe (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012; Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006). Its main disadvantage is that the relatively small number of observations (parties) makes it difficult to test the validity of specific models at country level and there is the added issue of whether relatively small and insignificant parties should be considered equal to large and well-established parties when testing these models.Footnote 3 Demand-side data such as those presented in this article have the advantage of allowing us to infer dimensions from a large number of observations (respondents). The challenge, however, is one of making our data representative of potential voters; surveys are costly, hard to administer and still often fail to be representative across all relevant variables, while data from self-selected questionnaires such as a VAA require complex methodological treatment to make them representative (see below).

De Vries and Marks also identify two distinct approaches for estimating dimensionality. The first, the a priori approach, is a deductive approach that uses existing theory to define the most salient dimensions ex ante and subsequently fit the data to these dimensions. The second is the a posteriori approach that infers the dimensions as latent constructs from existing data on voter opinions or party positions (De Vries and Marks Reference De Vries and Marks2012, 186). Benoit and Laver (Reference Benoit and Laver2012) argue that an a posteriori or inductive approach to extracting dimensions often produces incomprehensible results. This is partly because such an approach assumes no prior knowledge as to which variables (issues) are relevant and partly because it proves difficult to estimate the number of relevant dimensions if inductive methods such as exploratory factor analysis or multi-dimensional scaling are used without any prior knowledge of what these dimensions may be. At the same time, the a priori approach to dimensionality, using as it does ‘a tried and tested conceptual language that has evolved over generations’ (Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2012, 199), may lead us to miss significant and rapid shifts in the structuring of political preferences, such as the emergence of new cleavages. As such it is a conservative approach that assumes that the fundamental dimensions of political contestation change only incrementally over the generations.

This article uses both a priori and a posteriori approaches. Our main aim is to explore whether the model of dimensionality proposed by Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) is the most appropriate one when we look at the demand side of politics, i.e. ordinary voters. Thus, we test whether the three dimensions used by Bakker et al. (one economic left-right dimension, one cultural TAN/GAL dimension and one European dimension) also fit data that consist of the policy orientations of the electorate. As a preliminary step, we assume the validity of these a priori defined dimensions and test first whether or not the correlations between them observed on the supply side (see Table 1) also pertain to the demand side, and second whether these dimensions do indeed ‘fit’ the data as well as they do on the supply side. We then go on to use a more inductive or a posteriori approach to identify the most relevant dimensions from the data for twenty EU member states and see whether these better explain the policy space than the Bakker et al. model.

Beyond this principal aim, three specific features of the European policy space are of interest to us, as they correspond to ongoing debates between scholars. The first is about the relationship between the economic dimension and the cultural dimension. Can we talk about a single ‘left-right’ dimension that aggregates both economic and cultural issues (Huber and Inglehart Reference Huber and Inglehart1995), or do economic and cultural issues form clearly distinct dimensions? If they exist as separate entities, do these two dimensions correlate in opposite ways in western and post-communist Europe (Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006)? The second is about the nature of the cultural dimension (if such a dimension exists). Specifically, does it relate to ‘post-materialist’ (TAN/GAL) issues as one group of scholars hold (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012; Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006) or does it instead draw from ‘transnational’ issues of ‘integration’ versus ‘demarcation’ (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006)? This relates to a third debate about whether issues of European integration form a separate dimension of their own (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012), form part of a cultural dimension (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006) or integrate with the cultural dimension in Northern creditor countries and with the economic dimension in Southern debtor countries (Otjes and Katsanidou Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017). While the work of Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) provides some insights into these three points from a supply-side perspective, the aim of this article is to see whether the same patterns apply when we draw from the demand side.

Of course, we would not necessarily expect the demand side to correspond to the supply side. Voters ‘think much less ideologically’ (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2002) and their opinions are therefore a lot less coherent (and often more contradictory) than party positions, which are designed to be (more or less) ideologically consistent. It is therefore quite possible that the policy space as defined by voters will not correspond, or will correspond only poorly, with that defined by parties. Nevertheless, because we believe that it is the evolving preferences of voters that ultimately drive party strategies, we also hold that understanding the policy space from the demand side is critical to understanding the changing face of politics in Europe.

Data and Methods

The Data

The data consist of responses to policy statements from users of an online platform called EUvox (Mendez and Manavopoulos Reference Mendez and Manavopoulos2018), a Voting Advice Application that was deployed in all EU member states prior to the elections to the European Parliament (EP) in May 2014. VAAs are online questionnaires that enable users to compare their policy preferences with those of political parties (or election candidates) during an election campaign (for a recent, comprehensive overview of how they work and are used in political science see Garzia and Marschall Reference Garzia and Marschall2014). They provide users with a set of policy or issue statements to which they respond with varying degrees of agreement or disagreement. The EUvox VAA matched user responses with party positions that had been determined by expert coders and displayed these matches visually. Supplementary questions on variables of interest to political scientists such as socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, education) and political behaviour (interest in politics, party affiliation and vote intention both at the EP elections and in subsequent national elections) were also included in the questionnaire.Footnote 4

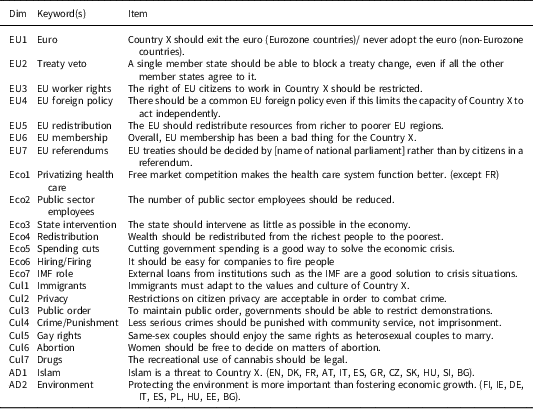

Turning to the subject of our study, political dimensionality, the great advantage of VAAs as a data source is that they can provide a huge volume of opinion data on a large number of diverse political issues. EUvox presented its respondents in all EU member states with thirty issue statements, of which twenty-one were common to all country questionnaires, except for France, which shared twenty of these. These items were selected to cover the issues identified by the Chapel Hill Survey data and used by Bakker et al. to define their three-dimensional space (economic left/right, social left/right or TAN/GAL, and EU) (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Anna Vachudova2015; Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012). Seven issues were about the powers of the EU, seven were about economic issues and seven were on cultural issues. These items are shown in Table 2 and are marked by the prefixes EU, Eco and Cul respectively. In addition, a further two items were shared by many, but not all, country versions of the VAA: one on the role of Islam (shared by twelve versions and identified as AD1 in Table 2) and one on the relative merits of environmental protection and economic growth (shared by nine and identified as AD2). The remaining items were specific to each country and will not be considered further in this analysis. The range of possible responses to items formed a Likert-type scale consisting of ‘completely agree’, ‘agree’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘completely disagree’ with a sixth response – ‘no opinion’ – treated as a missing value. In the case of the United Kingdom, different versions of the VAA were provided to English, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish voters. The England dataset is used for the UK as it was accessed by a far larger number of respondents than the other three.

Table 2 Common policy statements

For the purposes of the analysis, which involves several resampling iterations, we consider as valid datasets those with an N > 2,500 after cleaning and that are sufficiently balanced in terms of age, gender, education, political interest and vote intention to generate data that is representative of the voting population with respect to these variables after pre-processing. For details of how this is done, see below and refer to the online Appendix. Data from six small states (Belgium, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Malta) failed to satisfy these criteria and in two other states (the Netherlands and Sweden) separate VAAs were run with different questionnaires. This left us with valid data from twenty member states. The raw number of entries from each country (representing completed VAA questionnaires), the number of entries remaining after cleaning (to weed out users who answered the VAA with undue haste and potential repeat users) and after pre-processing (see below) are shown in Table 1 of the online Appendix.

Methods

As mentioned above, this article uses both a priori and a posteriori approaches. We will now expand on the methodological aspects of how we test these two approaches. The first stage of the analysis replicates the correlational analysis used in Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) on our demand-side data. To that end we first use the a priori defined dimensional model of Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) in which the policy space consists of one economic left-right dimension, one TAN/GAL (or social left/right) dimension and one EU integration dimension. As mentioned above, Eco, Cul and EU issue statements in EUvox were designed to correspond to these three dimensions. By drawing on user responses to these statements we can calculate the demand-side correlations between the three dimensions and compare them with the supply-side correlations calculated using the methodology of Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012). We do this by summing users’ positions on Eco, Cul and EU issues respectively to create a summated rating scale for each dimension, which is normalized to a 0–1 value.Footnote 5 However, we omit two of these statements: EU7 and Eco7 (see Table 2). We omit EU7 (on EU referendums) because it is more about the issue of direct democracy than about European integration and we omit Eco7 as it is also involves an issue of national sovereignty (the power of a transnational organization to guide domestic policy).Footnote 6 Having assigned users their scores we can then calculate the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between each dimension for each national-level dataset (just as Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) do for party positions).

The correlational analysis is the starting point of our empirical analysis. For the core analysis we draw on psychometric scaling methods that are derived from Item Response Theory (IRT) and apply these in two ways. First, we do so in a confirmatory mode to test the validity of a priori defined dimensions, that is, the three-dimensional model that Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) found best fit the CHES data. Second, we apply these methods in what has been referred to above as an a posteriori manner to identify political dimensions. This second approach is particularly useful when a priori defined dimensions turn out to be deficient. The objective in both cases is to identify reliable, unidimensional scales from the item bank of policy statements. The unidimensionality criterion is particularly important since the aim is to ensure that all items in a scale measure one, and only one, latent trait.

The IRT-derived psychometric method we employ draws on Mokken’s (Reference Mokken1971) monotone homogeneity model, often referred to as Mokken scale analysis (MSA). As with factor analysis, MSA can be used both as a confirmatory and exploratory method. However, when analysing Likert items Mokken scaling has a number of advantages. Both van Schuur and Kiers and van der Eijk and Rose provide quite convincing evidence that using factor analysis on ordered categorical survey items (so-called Likert items) often leads to over-dimensionalization (Van der Eijk and Rose Reference Van der Eijk and Rose2015; Van Schuur and Kiers Reference Van Schuur and Kiers1994). Furthermore, unlike factor analysis, MSA does not make rigid distributional assumptions (Van Schuur Reference Van Schuur2003). No doubt because of these attractive properties, MSA has already been used in other studies to identify latent political dimensions from VAA-generated data (Germann et al. Reference Germann, Mendez, Wheatley and Serdült2015; Katsanidou and Otjes Reference Katsanidou and Otjes2016; Mendez and Wheatley Reference Mendez and Wheatley2014; Wheatley Reference Wheatley2016; Wheatley et al. Reference Wheatley, Carman, Mendez and Mitchell2014).

In terms of the unidimensionality assessment, MSA generates a value H (also known as Loevinger’s H) that is a measure of the consistency of the responses to a group of items, as well as values H j that measure the normed covariance between each item score and the rest score from other items in the group. A group of items are said to form a scale (or dimension) if all H j of each item satisfy H j ≥ c, where c ≥ 0.3, and if all the items in the scale satisfy the monotone homogeneity model, the principle that if an item score changes there is a corresponding change in the latent trait (for more details, see the online Appendix). Items that belong to more than one scale are not included in any scale. A scale is considered weak if Loevinger’s H ≥ 0.3, of medium strength if H ≥ 0.4, and strong if H ≥ 0.5 (Mokken Reference Mokken1971).

Unlike the a priori approach, in which we use MSA as a confirmatory method to test the validity of the three-dimensional model, the a posteriori analysis, and our implementation of it, is a data-driven exercise in which we do not place any restrictions on the composition and/or number of unidimensional scales identified. In this second, exploratory mode, a scaling algorithm searches the item bank for the longest feasible unidimensional scales (for details, see the online Appendix). Taking into account Benoit and Laver’s (Reference Benoit and Laver2012) criticisms of the a posteriori approach, we should point out that this approach is not purely inductive since the focus on three themes – economy, culture and the EU – in the questionnaire draws explicitly from the existing literature as to which variables are relevant. Gemenis describes this technique as ‘quasi-inductive’ because it can be distinguished from a purely inductive exercise insofar as the policy items used in the analysis are inevitably pre-selected (Gemenis Reference Gemenis2013). Thus, the inductive component refers to the method of analysis we use to extract latent dimensions from user responses to a relatively large battery of pre-selected policy items. What such a method does not predetermine, however, are the issues that belong to each dimension or, indeed, whether issues belong to any relevant dimension at all.

We do recognize, however, that, as Benoit and Laver point out, ‘the attribution of spatial characteristics to policy differences is essentially a metaphor’ (Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2012, 195) and there is no ‘correct’ number of dimensions to extract. This is also illustrated by Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012), who find that, while a three-dimensional solution is the optimal model for describing party policy positions in all EU countries, in some cases (such as the United Kingdom) it is only a marginally better fit than lower dimensional solutions. Similarly, in our analysis we must acknowledge that setting 0.3 as a minimum threshold for H and

![]() $$H_{j} $$

, a convention established by Mokken and now widely used, is rather arbitrary and could generate different solutions if altered.

$$H_{j} $$

, a convention established by Mokken and now widely used, is rather arbitrary and could generate different solutions if altered.

MSA in its confirmatory mode is therefore applied in each dataset to the a priori defined dimensions, that is, it is applied separately to the same groups of Cul, Eco and EU items (minus Eco7 and EU7) that we used to calculate the correlations.Footnote 7 This allows us to test the explanatory power of the a priori model in describing the European political spaces. In the a posteriori approach to extracting dimensions MSA is applied to all twenty-one common (Eco, Cul and EU) items for each national level dataset. Items that are found to belong to more than one scale are not considered. We then carry out a second round of MSA on most datasets, this time including the additional items on Islam and the environment (AD1 and AD2) that are shared by some, but not all, country versions. This is done to check whether the dimensions we extract are stable if other possibly relevant items are added. In both rounds a set of items is deemed to form a scale only if it numbers at least three items.

Pre-processing

We conclude this section with a short note on a final, crucial step that we undertake before carrying out the analysis described above. This is pre-processing. As mentioned above, the main drawback of using the responses of VAA users to map the dimensionality of the policy space is that these users form a self-selected, rather than a representative sample. Not only are the political affiliations of VAA users often systematically skewed, but users tend to be disproportionately young, well-educated and interested in politics (Marschall Reference Marschall2014). Fortunately, there are a variety of ways in which VAA data can be made more representative using post-stratification weighting techniques. One such approach that is popular among survey researchers is raking.Footnote 8 Raking uses the marginal distributions of each variable in an iterative process that assigns weights until the weighted survey distributions approximate the distributions of the target population.

While deriving post-stratification weights is fairly straightforward, one immediate problem that arises is that MSA cannot be performed on weighted data. This is not only an issue related to our choice of method for conducting dimensionality analysis. The problem would remain if we were using factor analysis when the data consists of ordered survey items.Footnote 9 To overcome this problem we used a post-survey calibration approach that works in similar ways to raking.

The first step in this pre-processing phase is to identify the target population. In our case it is ‘voters’, rather than the general population. This is an important distinction since VAA-generated data are more likely to be representative of voters than non-voters. As with raking, the next step is to select the core calibration variables and derive reliable estimates of the target population parameters. We chose four such variables: (1) age by education (joint distribution), (2) gender, (3) political interest and (4) voting intention. For the first three parameters we derived estimates of the distribution among the ‘voting population’ from the European Social Survey. For the voting intention variable we simply used the party vote share from the EP elections in each country. The calibration algorithm then works like raking but instead of generating a vector of weights per respondent, it returns a resampled, non-weighted dataset (Djouvas and Mendez Reference Djouvas and Mendez2018). Herein lies one advantage of using VAA data where it is possible to retain – at least for some cases – a reasonably large dataset of observations that is calibrated on core variables of interest without using weights. This was the case for more than half the EUvox datasets.

For eight of the country cases it was not possible to achieve satisfactory convergence in terms of the number of observations retained. For these specific countries we used a two-step procedure. We first used raking to derive truncated replication weights, ensuring that in no case the maximum weight was greater than 8. The fractional weights were then rounded to the nearest integer to generate a new dataset with replicates (note that this is how some popular statistical packages, such as SPSS, perform weighted analysis). In step two we applied the calibration algorithm to the raked dataset to return a new resampled dataset on which the MSA could be performed. A detailed description of the pre-processing stage is included in the first section of the online Appendix.

Results

Our results are presented in the two sections below. We first deal with the correlation analysis and the comparison of supply-side and demand-side results before moving on to the core of our empirical analysis, the Mokken Scale Analysis.

Correlational Analysis

Applying the preliminary stage of analysis to the national level EUvox datasets and calculating the correlations between the a priori defined dimensions, we find that rather similar trends pertain on the demand side as Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) and Marks et al. (Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006) observe on the supply side. The demand-side correlations are shown in Table 3. First of all, economic left-right and social left-right (TAN/GAL) correlate positively in all western European countries and negatively in all post-communist countries except Slovenia (strongly) and Estonia (marginally). In most post-communist countries these negative correlations are mainly rather small, except in the case of Hungary. It is worth noting that the findings with respect to Hungary and Slovenia (a strong negative correlation in the case of the former and a strong positive correlation in the case of the latter) are precisely the same trends as those identified by Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012, 229). In Spain and, to a somewhat lesser extent, Austria, England and France, the negative correlations are particularly strong, a trend that can also be seen in Table 1.

Table 3 EUvox correlations, 2014

Looking now at the correlations between the EU dimension and the social left-right dimension for the EUvox datasets, we find that these two dimensions appear to be more or less orthogonal in Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Slovenia. In all other countries a negative correlation is observed (meaning that TAN respondents tend to be more Eurosceptic), which is particularly marked in England, Finland, France and Hungary – a trend observed also in Table 1 except in the case of France. In Spain, only a weak negative correlation is observed. While Table 1 suggests a positive correlation on the supply side for all so-called ‘bail-out’ countries except Greece, Table 3 suggests that in these cases (with the partial exception of Spain) the two dimensions are more or less independent. Table 3 also groups Greece together with other bail-out countries (unlike Table 1). As in Table 1, these countries are set apart as they do not share the same rather strong negative correlations observed in non bail-out countries. Once again, generally speaking, the demand-side correlations correspond well with the supply-side correlations.

Finally, the correlations between the EU dimension and the economic left-right dimension shown in Table 3 provide a mixed bag, just as they do in Table 1. While two Southern debtor countries, Cyprus and Greece (as well as Hungary), exhibit a strong positive correlation, with the economic right associated with pro-EU positions and the economic left with Eurosceptic positions, the opposite trend prevails in Austria, Germany and, most notably, England. These countries exhibit similar trends in Table 1, although with different intensities.

To sum up, while the coefficients in Tables 1 and 3 are very different – and we would expect them to be different given the fact that, as mentioned above, political parties (unlike voters) need to express a clear and consistent political standpoint – groups of countries often express very similar tendencies when viewed from a demand perspective as they do from the supply perspective. This applies above all to the correlations between economic left-right and social left-right (TAN/GAL) but also holds for some correlations involving the EU dimension.

Scaling Analysis

Correlational analysis can only take us so far in our endeavour to analyse dimensionality. We now move on to a more robust form of analysis, namely the application of MSA. This analysis first involves ‘validating’ the a priori defined dimensions. To what extent do these constitute reliable and unidimensional scales? Applying MSA in its confirmatory mode will allow us to answer this questions. If we apply it to the pre-defined groups of Eco, Cul and EU items (excluding Eco7 and EU7) we find that these dimensions are rarely scalable. Table 2 in the online appendix gives the H coefficients when MSA is applied to the items of the a priori defined dimensions, as well as (in brackets) the number of items that satisfy the condition

![]() $$H_{j} \geq 0.3$$

. It is extremely rare that all items in any dimension fulfil this condition and in most cases the scale as a whole fails to satisfy the overall

$$H_{j} \geq 0.3$$

. It is extremely rare that all items in any dimension fulfil this condition and in most cases the scale as a whole fails to satisfy the overall

![]() $$H\geq 0.3$$

condition. Not only that, but many items that do satisfy

$$H\geq 0.3$$

condition. Not only that, but many items that do satisfy

![]() $$H_{j} \geq 0.3$$

would also form a scale if combined with items from another a priori defined dimension. This applies particularly, but not exclusively, to the Cul and EU scales. Overall Cul (TAN/GAL) items scale particularly poorly when MSA is applied as the consistently low values of H suggest.

$$H_{j} \geq 0.3$$

would also form a scale if combined with items from another a priori defined dimension. This applies particularly, but not exclusively, to the Cul and EU scales. Overall Cul (TAN/GAL) items scale particularly poorly when MSA is applied as the consistently low values of H suggest.

Since a validation of the a priori defined dimensions using MSA yielded deficient scales we now apply MSA in its exploratory mode to identify unidimensional scales. This a posteriori part of the analysis involved multiple iterations of MSA for each of the twenty country samples. The relevant MSA coefficients both for the twenty-one common items alone and for these items plus items AD1 and AD2 (in cases in which they are present) are provided in Tables 3–31 of the online Appendix.

In order to summarize this complex analysis rather more briefly we shall rely on the heat map visualization shown in Figure 1 to represent the results of the scaling analysis for nineteen of the twenty datasets. Romania is not included as no unidimensional scales could be identified when MSA was applied. The columns in the heat maps represent each unidimensional scale that satisfies the Mokken scalability criteria (see above). Non-scalable items are depicted by empty white cells in the heat maps.Footnote 10 We use colour shading, as shown in the legends, to indicate an item’s scalability and, in the last row of each column, to show the overall strength of a scale as measured by Loevinger’s H. The heat maps refer to analysis of the twenty-one common items only, but reference will be made in the subsequent paragraphs to any relevant changes in the dimensional structure that result from including AD1 and/or AD2.

Figure 1 Heatmaps depicting results of Mokken Scaling Analysis. (a) Two-dimensional solutions (group 1). (b) Two-dimensional solutions (group 2). (c) One-dimensional solutions.

As can be seen from the heat maps in Figure 1, a number of broad patterns emerge if we apply MSA to each of the national level datasets, although these mask considerable heterogeneity. None of the cases adheres to a three-dimensional model with separate economic, cultural and EU dimensions. First, we find a group of seven countries in which politics is defined by two dimensions – one cultural/EU dimension and one economic dimension. The heat maps for this group are shown in Figure 1a. England is something of a special case here; a one-dimensional solution defined by a single left-right dimension that includes economic, cultural and EU issues is also possible (see Table 10 in the online Appendix), but the two dimensions separate when the minimum threshold c for H j is raised to 0.45. In all seven cases the cultural/EU dimension embraces a variegated mix of issues including immigration (in six cases), gay rights (in four cases), abortion (in one case) and a variety of EU integration issues (in all cases). Although in the case of Denmark it appears that this dimension exclusively refers to EU items, if we include AD1 (on Islam) into the analysis (AD2 was not used in the VAA questionnaire), we find that not only does this item load onto the same dimension as the EU items, but its inclusion also brings Cul1 (immigrants) into this dimension (see Table 9 in the online appendix). In the cases of Austria and Italy too, at first glance the cultural/EU dimension seems to be dominated by EU items with only one cultural item (Cul1) present. However, in both cases AD1 can be aggregated into this dimension and in the case of Italy its inclusion brings Cul5 (gay rights) into the scale as well (see Table 24 of the online Appendix). For the group as a whole, the economic dimension embraces a number of classical left-right issues on privatization, state intervention and spending cuts, but in most of these cases it is the cultural/EU dimension that is the dominant of the two, embracing more issues and/or exhibiting stronger covariance as evidenced by higher values of H. Overall this group of countries consists of relatively economically stable, mainly northern European countries.

The remaining countries are far more heterogeneous in terms of the dimensional structure identified. Cyprus and Slovenia exhibit a two-dimensional structure with one economic and one cultural dimension, but, unlike the first group of countries, most EU issues belong to the economic dimension, not the cultural dimension (see Figure 1b). In both cases at least two items (on the euro and on EU membership) form a part of the economic dimension, as does one cultural item (on public order) in the case of Cyprus. Despite its apparent one-dimensional structure, Greece can also be said to belong to this small group of countries as the defining dimension incorporates a mix of EU and economic items (see Figure 1c). Moreover, if AD1 is included, a second (cultural) dimension emerges incorporating three issues: EU3 (on EU worker rights), Cul5 (gay rights) and AD1 (Islam). For more details, see Table 20 of the online Appendix. Note that in the Greek case, as in the case of Cyprus, the item on public order (Cul3) aggregates onto the economic/EU dimension, despite it being ostensibly a cultural issue. It is also worthy of note that one EU item (on EU worker rights) integrates into the cultural dimension in the cases of both Greece and Cyprus. In all three cases the economic dimension is dominant and in the case of Greece it is the only dimension to emerge if twenty-one items are used.

Two other cases worthy of mention are the cases of Spain (Figure 1b) and Hungary (Figure 1c). Spain exhibits a two-dimensional structure with one EU dimension that includes just three items and one broad left-right dimension that aggregates four economic items and six cultural items, and distinguishes an economic right TAN position from an economic left GAL position. Hungary exhibits a reverse pattern with a single dimension that aggregates not only economic and cultural issues but also EU issues, and, unlike Spain, separates economically left-wing, Eurosceptic social conservatives from economically right-wing Europhile social liberals.

As for the remaining two-dimensional cases shown in Figure 1b, all scales are relatively small (never aggregating more than four items) and are mainly restricted to a single category (EU, Eco or Cul). In the Irish case we observe an EU dimension that also includes an item on the role of another transnational organization (the IMF, Eco7) and a small cultural dimension that aggregates lifestyle issues (Cul5, Cul6 and Cul7). In Slovakia and Portugal the analysis reveals distinct economic and cultural dimensions, but EU issues neither aggregate onto these nor form a separate dimension of their own. Finally, in the Czech Republic an EU dimension and an economic dimension emerge, but cultural items do not aggregate onto any scale.

In addition to Greece and Hungary, there are three other cases in which we can identity only one dimension (see Figure 1c). These are Poland, Bulgaria and Estonia. The defining dimension in Poland aggregates three EU issues with two cultural items (on gay rights and abortion), with a pro-EU position associated with a more tolerant attitude towards both cultural issues. Bulgaria and Estonia are characterized by a single dimension that only aggregates EU issues.

It is worth noting that in none of the cases in which AD2 (the environment) was included in the VAA did these issues load onto the cultural dimension, as one would expect if the cultural dimension corresponded to the TAN/GAL model. Indeed AD2 loaded onto neither dimension in any of the nine cases in which it was used. AD1 (Islam), on the other hand, tended to integrate into the cultural dimension, especially in the first group of seven countries (for more details see the relevant Tables in the online Appendix).

Discussion

The first point that is worthy of note is that in terms of the correlations between the a priori defined dimensions, some common patterns can be observed between the demand side (EUvox users) and the supply side (CHES 2014 party positions). This applies particularly to the correlations between the economic left-right and social left-right (TAN/GAL) dimensions and lends added weight to the original hypothesis of Marks et al. (Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006) that these two dimensions correlate in opposite directions in West European and post-communist countries (compare Table 1 and Table 3). Some credence should also be given to Rovny’s (Reference Rovny2014) hypothesis that countries that had previously belonged to communist federations tend to buck this trend insofar as in these countries the two dimensions tend to correlate in the same way as they do in Western Europe. Both successor states to communist-era federations that we analyse (Slovenia and Estonia) appear to confirm Rovny’s hypothesis. Another common feature that the demand side and the supply side seem to share is that in most so-called ‘bail-out’ countries, as well as in Slovenia, the close association between TAN values and Euroscepticism (and between GAL values and pro-EU positions) that is observed in other countries does not seem to pertain. Finally, the strong correlations observed in the extreme or deviant examples of Spain, England, Hungary and Slovenia are observed in the demand side just as in the supply side (see Tables 1 and 3) (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012).

A significant feature of the demand-side analysis of EUvox data, however, is that those issues that the Chapel Hill group of scholars propose form the TAN/GAL dimension (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Anna Vachudova2015; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006; Rovny Reference Rovny2014) fail to form a scale when we apply MSA. This first becomes evident when we apply MSA to the three a priori defined Eco, Cul and EU dimensions. We find that not only do these groups of items overall fail to constitute scales as defined by Mokken (Reference Mokken1971), but the TAN/GAL items scale particularly badly (see Table 2 of the online appendix).

The reasons for this become clearer when we look at the dimensions that emerge when we perform MSA a posteriori. In the first group of seven mainly Northern European countries Cul1 (immigrants) and Cul 5 (gay rights) tend to scale with EU items, while the other Cul items generally do not form part of any scale at all. In other cases Cul5, Cul6 (abortion) and Cul7 (drugs) sometimes form a mini scale of their own. Issue AD2 on the environment does not appear to integrate into this dimension at all, as the label ‘TAN/GAL’ would imply. Similarly, in no case did items involving law and order or civil liberties (Cul2, Cul3 and Cul4) form a common dimension with other TAN/GAL issues, nor did they form a libertarian-authoritarian dimension of their own as Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt2013) suggests. In the cases of Greece and Cyprus, Cul 3 (on whether governments should restrict demonstrations) instead integrated with the economic dimension, perhaps because this issue was linked in the public mind with the right to protest against austerity.

In the first group of seven countries, the cultural dimension relates far more to identity-related issues of universalism versus particularism (Beramendi Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015b, Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann and Kriesi2015) (‘open’ versus ‘closed’) than to archetypal TAN/GAL issues; as well as immigration and gay rights, this dimension embraces EU-related issues and the role of Islam. This group of countries consists of relatively wealthy Northern European countries, which would appear to corroborate Otjes and Katsanidou’s (Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017) hypothesis that in Northern European countries issues of EU integration are associated with the cultural dimension of political competition.

However, this pattern is not shared by all countries; in Greece, Cyprus and Slovenia, it is the economic dimension that encompasses issues of EU integration. It is worthy of note that Greece and Cyprus both received a bail-out under the condition of slashing public spending, while Slovenia only avoided this by imposing equally harsh austerity measures of its own. Thus, the hypothesis of Otjes and Katsanidou (Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017) that issues of EU integration would aggregate onto the economic dimension in the Southern European debtor states seems to be supported in these cases. This can perhaps be explained by the fact that, in these countries, many of the ‘losers’ of recent economic transformations are relatively well-educated young people, who are less likely to be convinced by culturally exclusive ‘right-wing’ narratives and instead direct their anger at economic austerity. As Hooghe and Marks point out, in these debtor countries – which include Spain, Ireland and Portugal as well – ‘austerity and currency inflexibility produced economic misery and resentment which was mobilized chiefly by the radical left’ (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, 9). It is interesting to note that none of these countries, except for Greece, have a significant radical (culturally) right-wing party, but instead have relatively large radical left-wing parties (SYRIZA in Greece, Podemos in Spain, the Left Bloc in Portugal, Sinn Fein in Ireland and the United Left in Slovenia). In Greece, the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn, while significant, garners far fewer votes than SYRIZA, which won two general elections in 2015. At the same time we must recognize that while our a posteriori application of MSA seems to reveal a strong association between certain EU and certain economic issues in three countries, that it does not do so in the cases of Portugal, Spain and Ireland suggests that Otjes and Katsanidou’s hypothesis provides only a partial explanation.

Despite the fact that the patterns emerging from our demand side a posteriori approach are rather different from those that Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) identify from the supply side, certain common features can still be discerned from the two sets of patterns. If we look at the relationship between the economic and cultural dimensions, two rather opposite and exceptional cases that emerge from Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012) also emerge as distinct cases from our own findings. These are Spain on the one hand, and Hungary on the other, which respectively exhibit very strong positive and negative correlations between the economic left-right dimension and the social left-right dimension when we look at party positions as derived from CHES (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012, 229). These two cases also appear exceptional when we derive dimensions a posteriori from EUvox data; in both cases economic left-right and TAN/GAL issues aggregate onto a single dimension. However, in Spain this dimension runs from economic left/GAL to economic right/TAN, while in Hungary it runs from economic left/TAN to economic right/GAL. This fully corroborates the findings of the supply-side study.

Another common feature that can be discerned, albeit less clearly, is the relationship between cultural TAN/GAL and EU issues. Generally speaking, the supply-side data both from the 2006 CHES and from the 2014 CHES (see Table 1) suggest that in most countries, with the exception of most so-called ‘bail-out’ countries, there is a strong association between TAN and Euroscepticism amongst European political parties (and, by implication, between GAL and pro-EU positions). Our demand-side studies on Northern Europe suggest that, at least from the perspective of the electorate, EU issues actually form part of the same dimension as some of the so-called TAN/GAL issues and this may go some way towards explaining the association between these groups of issues. Here, however, we must express the caveat that the trends that emerge from the supply-side data are not particularly consistent; this could be, as suggested above, because the weight given to relatively insignificant parties may buck the trend.

Conclusion

A comparison of the results of demand- and supply-side studies into the dimensionality of the political space in Europe reveals both a number of similarities and some stark differences. It remains for us to close with a few brief comments on both the nature of these similarities and differences and on the methodological strengths and weaknesses of the two very different approaches.

We use the term ‘dimension’ to refer to a bundle of issues that are deemed to be associated with one another in such a way that to know the position of a party or voter on one issue allows a reasonable degree of confidence in predicting her/his/its position on another issue from the same bundle. This study has shown that there is some correspondence between the sorts of correlations that are observed between the same bundles on the supply side (party data from the CHES) on the one hand, and on the demand side (EUvox data) on the other. A key similarity here is the way the bundle of issues that are commonly seen as economic left-right issues correlates with the bundle of issues that are described as TAN/GAL (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012; Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006). From both sets of data we observe a tendency for these two bundles to correlate in one direction in Western European countries and in the opposite direction in most (but not all) post-communist countries.

Where the two approaches differ, however, is that the bundles of issues that are said to constitute dimensions on the supply side do not seem to do so on the demand side. This applies first and foremost to the so-called TAN/GAL dimension; issues associated with TAN/GAL appear to be associated only very weakly with one another when viewed from the demand side. If we look at the demand-side data from EUvox we find that issues involving civil liberties, law and order and environmentalism do not form a part of the cultural dimension and in some countries (Cyprus, Greece) issues of civil liberties and law and order even form a part of the economic dimension. This leaves the cultural dimension either restricted to a few moral-cultural issues (such as gay rights, abortion, drug use) or forming a broader identity-based dimension that also incorporates EU issues.

This leads to another major difference between the two sets of findings. While supply-side studies suggest that a three-dimensional model best fits the data, our demand-side study suggests that it does not and that different bundles of issues group together and form dimensions in different ways in different countries. This particularly applies to the cultural dimension of political competition. In a group of Northern European countries, issues of EU integration aggregate with issues of immigration, gay rights and perception of Islam to form a broader identity-based dimension based on a divide between universalism and particularism or ‘open versus closed’. In other countries, however, EU issues either aggregate with an economic left-right dimension, form a separate dimension of their own or do not aggregate into any dimension at all.

That we observe differences should not surprise us. We are, after all, comparing two very different types of study. On the one hand we have a study that defines dimensions a priori and uses as its theoretical starting point the positions of parties, the supply side, while on the other we have a study that defines dimensions a posteriori and draws from the position of the electorate on the demand side. We also use different statistical methods for extracting dimensions: factor analysis on the one hand and Mokken Scale Analysis on the other.

We must be aware that no single methodology provides a ‘correct’ account of dimensionality. Fundamentally, of course, the supply-side and demand-side approaches are measuring different things: in one we are trying to understand patterns of competition between parties; in the other we are interested in the political orientations of voters. One strength of the approach of this article is that identifying political dimensions from a demand-side perspective allows us to infer the underlying cleavages that divide our societies from the dimensions we identify. As an example, this article presents evidence that the cultural dimension in many Northern European countries corresponds more closely to ‘closed’ vs ‘open’ than to TAN versus GAL. This in turn implies that in these countries the patterns of political competition that we observe today on the demand side may be linked to the new cleavage between ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of globalization (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008), also referred to as the ‘transnational cleavage’ (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). Indeed, cleavage theory suggests that demand-side dynamics go on to determine supply-side dynamics. Kriesi et al. suggest that parties reposition themselves strategically to accommodate the political demand engendered by the new cleavage (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006, 923), while Hooghe and Marks (Reference Hooghe and Marks2018) hold that this new demand-side pressure may bring about a radical break in the party system and the formation of new parties. It is therefore possible that demand-side dimensionality is a harbinger of supply-side dimensionality in the future. However, this hypothesis is highly speculative and should be left to future researchers.

Supplementary Material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1B1MXY and the online appendix can be found at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000571

Acknowledgements

We thank Vasilis Manavopoulos (Cyprus University of Technology), Costas Djouvas (Cyprus University of Technology), Kostas Gemenis (Max Planck Institute, Cologne) and all the reviewers for their helpful comments.