Tempers ran high at Meru local native council (LNC) meetings in early 1948. The councilors were considering assertions by their counterparts in the densely populated Kiambu District that the Meru should allow landless Kikuyu to settle amongst them on the grounds that all of the agrarian communities of the Kenyan highlands were members of the same ‘tribe’. These were tense times. The would-be migrants had been turned off settler farms and out of the over-crowded Kikuyu heartland. Having reserved the most fertile regions of the highlands for European settlers, the Kenyan government struggled to find room for an expanding, highly entrepreneurial, Kikuyu population that had outgrown its ‘native reserves’. Although colonial administrators had little idea that within three years their tribally-based constrictive land policies would provoke the ‘Mau Mau Emergency’, a revolt by landless young Kikuyu, they recognized that the security of British rule depended on finding space for the tens of thousands of desperate Kikuyu who did not fit within the imperial geography of Kenya. Consequently, district officers were ready to encourage Kikuyu settlement in less crowded reserves even though the Kiambu district commissioner acknowledged that other communities feared that people from his district were ‘trying to set up Kikuyu colonies on their land’.Footnote 1

The Meru LNC recoiled at the Kiambu councilors' assertion that the Meru were really just Kikuyu who had been cut off from the Kikuyu heartland. Stressing their cultural distinctiveness, the council complained that Kikuyu interlopers seized high quality land and rejected the authority of Meru tribunals. Yet the councilors also carefully divided the migrants into two distinct categories. Reverend Cornelio M'Mukira explained that the Meru had a longstanding practice of accepting any outsider willing to be adopted into a Meru clan as ‘muchiarwa’. In his eyes, the problem was the Kikuyu ‘murombi’ who farmed a piece of land on a limited basis. The former term was most likely derived from guchiarwa, meaning ‘to be born’, which referred to the fictive blood relationships that developed between Meru families and clans. A murombi, conversely, was a stranger and a beggar. These assimilative practices were not unique, and the Kikuyu themselves also accepted outsiders into their mbari (lineages) as aciarua. Detailed evidence about the adoption process is scant, but it appears that the Meru absorbed significant numbers, probably totaling in the thousands, of Kikuyu and other outsiders as guchiarwa during the colonial era. Indeed, the Meru district commissioner noted that there were plenty of people from other tribes in his district, some from as far away as Tanganyika, who had become ‘perfectly good Meru’.Footnote 2

Assimilation into a new community entailed a loss of wealth and status, but it appears that many landless Kikuyu accepted this burden as the price of gaining access to land. One could move from one ‘tribe’ to another if the adoptee and prospective hosts were sufficiently willing. This was possible because there were indeed significant cultural and linguistic continuities among the various agrarian communities of the highlands. These included patrilineal reckoning of descent, patrilocal marriage practices, and the organization of society around age sets.Footnote 3 While shifting or redefining ethnic identity is never easy, the tense exchanges between the Kiambu and Meru LNCs were born of a much larger controversy in British-ruled Kenya that linked identity with physical space, land tenure, economic accumulation, and social status.

RETHINKING TRIBALISM AND IDENTITY

Ethnicity is a seductively useful frame, which groups people into coherent and bounded categories based on a shared set of characteristics. East African colonial governments in particular sought to shift conquered populations, whose statelessness seemed chaotic and confusing, into understandable and manageable administrative units. Conveniently, they assumed that tribes were less advanced than nations, and thus the British version of the new imperialism was moral and defensible because primitive tribesmen could not govern themselves. By official imperial thinking, these ‘tribes’ had a common language, uniform social institutions, and rigid customary laws based on the perception of kinship. In practice, colonial categories of identity were largely innovative and imprecise. Their artificiality and ‘weakness’ led John Iliffe to make the now famous observation that ‘the British wrongly believed that Tanganyikans belonged to tribes; Tanganyikans created tribes to function within the colonial framework.’Footnote 4 Iliffe's epigrammatic summary helped launch a historiographical reconsideration of ethnicity that treated colonial-era ethnic identities as the recent, if not explicitly invented, products of human agency, and that, over time, argued for the importance of African influence as well as colonial imagination.Footnote 5 The older men who successfully claimed the status of chiefs, thereby earning the right to speak for their tribes, and the patriots who embraced tribal identities to assert control over women and younger men were equally invested in promoting these collectivist identities.Footnote 6

These constructivist and instrumentalist perspectives help to explain why and how contemporary Kenyan supra-tribes like the Mijikenda, Kalenjin, and Luhya emerged in the twentieth century.Footnote 7 Moreover, this scholarship usefully punctures colonial-era stereotypes of ahistorical African tribalism. It risks, however, overstating the capacity of both African cultural brokers and imperial administrators to entirely create new ethnic identities. Thomas Spear argues persuasively that instrumentalist and constructivist analyses miss key continuities between the pre-conquest and colonial eras and cannot explain either the power or the content of contemporary tribalism.Footnote 8

The case of the Kikuyu migrants in Meru brings some clarity to this debate by paying greater attention to how individuals defined themselves in relation to their position in the tribal geography of colonial Kenya, for individual perspectives and ambitions are often lost in the theoretical literature on ethnicity in colonial Africa. This study therefore moves beyond literate culture brokers whose accessible and legible output may too easily dominate analysis by focusing on the decisions of ordinary people not simply in a world of affect and cultural continuity, but in immediate concerns over their own personal status and their strategies for accumulation. Studying these debates over people who crossed ethnic boundaries offers a way to understand something of the dynamics of choice and constraint which shaped ethnic identity at an individual level.

The migrants who militantly insisted on declaring themselves to be Kikuyu demonstrated that colonial tribal identities could express an entrepreneurial individualism that was defiantly at odds with state-sponsored tribal collectivism. The individualistic commercial farmers who rejected adoption into the Meru tribe did so on the grounds that they were Kikuyu, but their interpretation of what it meant to be Kikuyu was sufficiently adaptive and innovative to accommodate new economic practices and social norms even as it invoked pre-conquest traditions to assert their difference and individuality. Far from being an anachronistic vestige of a pre-conquest tribal age, militant Kikuyuness in a foreign native reserve meant that a person refused to allow the imperial regime to define them as a tribesman with no individual rights to political representation or economic advancement. Being Kikuyu asserted an aspiration to own land, produce for the market, and define oneself as a fully formed person on par with European settlers. This conception of being Kikuyu, which had its roots in nineteenth-century traditions of pioneering agriculture, allowed for a much greater degree of individualism than the tribal collectiveness and moral ethnicity of the native reserve system could accommodate.Footnote 9 Conversely, the hundreds, if not thousands, of migrants who agreed to become Meru were willing to renounce their Kikuyuness (at least overtly) because they saw adoption as a means of gaining personal security and access to land. Being Kikuyu meant different things to different individuals, depending on their circumstances and position in colonial society.Footnote 10

Equally important, the colonial government's perception of what it meant to be Meru or Kikuyu evolved over time. It was largely impossible to turn state-sponsored tribal ethnographies and romantic essentialised notions of tribal culture into viable administrative policies. Consequently, the very colonial officials who spoke passionately about their obligation to protect fragile tribal cultures developed policies that promoted a far more flexible and pragmatic notion of colonial tribalism. By the time of the showdown between the Meru and Kiambu LNCs in the late 1940s, the Kenya government was urging Meru elders to accept anyone willing to bow to their authority as Meru. While the imperial regime's native reserve system dictated that questions of belonging and identity had to be phrased in tribal terms, the disruptive individuals who insisted on remaining Kikuyu in Meru demonstrated that ordinary people had the capacity to undermine this tribal geography.

THE NATIVE RESERVES IN THEORY AND PRACTICE

Linking physical space to ethnic identity, the reserve system made no allowance for individuality. Under colonial law, reserve land was collective tribal property and could not be owned or developed by individuals or sold to outsiders. More pragmatically, the reserves were manageable administrative units and served as reservoirs of cheap labor for European employers: they fulfilled the humanitarian promise of Frederick Lugard's dual mandate, promoting economic development and safeguarding ‘native interests’.Footnote 11

In practice, the reserves were never as rational or coherent as they appeared in London or Nairobi. This was particularly true in the central highlands where the ‘Kikuyu Land Unit’ was the official settlement area for the Kikuyu and the culturally-related ‘Kikuyu sub-tribes’. Covering roughly 6,100 square miles and divided into separate tribal enclaves that roughly corresponded to the administrative districts in Central Province, it had an approximate population of 1·2 million people in 1948. The Fort Hall (Murang'a) and Nyeri Kikuyu reserves were overcrowded, but it was in the Kiambu reserve, where the Kikuyu population density was 331 people per square mile in 1945, that the irrationality of the reserve system came into sharp focus.Footnote 12 Here the explosive combination of European land expropriation, privatization of reserve land for commercial agriculture, and rapid population growth raised tensions and led kinsmen to turn on each other for the same piece of land. Consequently, Kiambu hemorrhaged people throughout the colonial era.

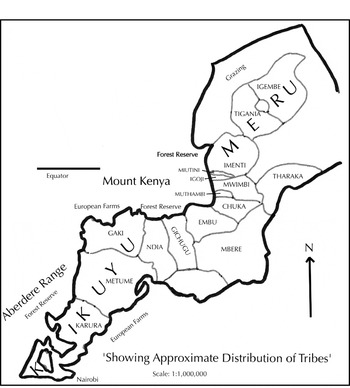

The Embu and Meru reserves, which occupied the western most portion of the Kikuyu Land Unit, were much emptier and far less tense. While the arid and tsetse fly-ridden western lowlands of Embu and Meru districts were barely usable, in the 1930s and 1940s there was still unclaimed land in the optimal eastern zone that fell between 4,200 and 5,500 feet above sea level (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the higher forested parts of the Meru reserve beckoned to enterprising farmers willing to defy forestry laws by clearing them.Footnote 13

Fig. 1. Lambert's ‘Sketch Map of the Kikuyu Land Unit’.Footnote 14

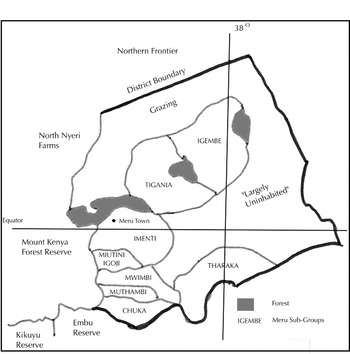

Although the native reserves appeared as clearly demarcated spaces on official maps, they never were coherent tribal homelands, because their British designers could not standardize or simplify the complex mosaic of highland identities. In the pre-conquest era, highland peoples often assumed new identities through migration, commerce, enslavement, intermarriage, and adoption.Footnote 15 The Kenya government recognized five closely related subgroups (Igoji, Miutini, Imenti, Tigania, and Igembe) plus four slightly more distinct communities (Muthambi, Mwimbi, Chuka, and Tharaka) as ‘Meru’, but even these subcategories were largely abstractions (Fig. 2). In the nineteenth century, the ridge top was the most significant factor in shaping collective identity in what became the Meru reserve.Footnote 16 The neighboring Embu reserve was equally diverse. Under British rule, it included a variety of peoples who identified themselves as Mbeere, Chuka, Gichugu, and Ndia (colonial authorities often counted the latter two groups as Kikuyu) in addition to the Embu themselves. Similarly, the imperial-era Kikuyu began as a diverse collection of pioneer immigrants who most likely started to clear the highland forests for farming in the late seventeenth century. In this sense ‘Kikuyu’ was more an expression of agricultural expertise than a coherent or bounded ethnic group. These diverse agricultural communities also shared oral traditions that their ancestors migrated into the highlands several, if not many, centuries earlier.Footnote 18

Fig. 2. The colonial geography of the Meru ‘Sub-Tribes’.Footnote 17

Most district officers were aware of these realities. The pioneer administrator Granville St. John Orde-Browne acknowledged the inherent ambiguity of the native reserve system when he characterized the region between the Meru and Embu heartlands as a ‘debatable’ space ‘inhabited by a group of small tribes possessing many of the characteristics of their neighbors, but also retaining numerous local peculiarities’.Footnote 19 In Nairobi, however, the colonial government held fast to the notion that Africans lived in precisely bounded tribal societies because tribal stereotypes served specific political and administrative purposes. Under the 1902 Village Headman Ordinance, the regime's African allies were simply ‘executive agents of the administration’, but tribal romanticism turned them into usefully autocratic chiefs.Footnote 20

It did not matter that highland peoples did not have chiefs in pre-conquest times, for the Kenya administration gave colonial identities meaning by making the tribe the basic unit of government, education, labor, law, and most importantly land tenure. At some point, modernizing British rule would transform tribesmen into individuals, but in the near term the Kenya government held that tribal land was community property and could not be sold or transferred to individuals, African or otherwise. Indeed, the Kenya Supreme Court dismissed Kikuyu land claims by ruling that all ‘lands occupied by the native tribes of the Protectorate’ was Crown Land, which meant that individual tribesmen only had rights to the land they were actively farming.Footnote 21

This ‘trusteeship’ was a fig leaf obscuring the real purpose of the reserve system, which was protecting the exclusive land claims of the Kenyan settler community. Through a series of laws and ordinances the Kenya government appropriated territory for European settlement and commercial development on the dubious legal grounds that specific tracts of land were either unclaimed or that Africans did not make sufficiently productive use of them. By 1914, roughly 1,000 settlers controlled some 17,000 square miles of the highlands on 99 year leases, but they actually only had about 10 to 12 per cent of it in production. Speculators held most of the rest.Footnote 22 The Crown Lands Ordinance of 1915 contained a provision for setting aside reserves for the exclusive use of particular tribes, but in defining where Africans could reside the legislation's real purpose was to mark out the spaces where they could not.

The legislation did not explicitly grant Africans formal title to the reserves, and the authorities dragged their heels in demarcating their actual boundaries. This was largely because senior officials agreed with the settlers' assertion that African lands should not be closed off to future economic development, and it took pressure from missionaries and the metropolitan humanitarian lobby to force the government to enact the Native Lands Trust Ordinance, which established that the reserves were ‘for the benefit of the natives tribes for ever’.Footnote 23

Yet these reserves could not accommodate a growing Kikuyu population. Home to over 400,000 people in the early 1930s, the three Kikuyu reserves had a population density of 283 people per square mile and were never sufficient to contain a community that was increasing by 2·5 per cent annually.Footnote 24 Speaking of only Nyeri and Fort Hall, the agricultural officer Colin Maher observed: ‘one may stand and see more than a thousand acres at a stretch with scarcely an acre uncultivated’.Footnote 25 The situation was even tenser in Kiambu where British conquest blocked Kikuyu farmers from opening up new lands and where the government seized existing farms for mission stations and white settlement. Moreover, its proximity to Nairobi and European settled areas accelerated a shift to individual land holding by providing markets for agricultural produce and cash crops. This wealth made productive land even dearer as senior men turned away tenants and junior relatives. As farmland grew scarce, social tensions in Kiambu inevitably increased, and district officers noted a rise in ‘inter-family squabbles’ born of a pernicious individualism.Footnote 26

Consequently many Kikuyu, Kiambu people in particular, had to either become squatters on settler estates or seek their fortunes in less crowded reserves. This slow and not entirely visible population shift began before the First World War and increased in the interwar decades. By the early 1930s, 110,000 Kikuyu were living outside their home reserves.Footnote 27 Far from secure in their privileged position in the highlands, the settlers fretted constantly about the risks of living precariously amongst a sea of Kikuyu squatters.

The long term viability of the white highland thus meant resettling these surplus people in more sparsely inhabited reserves. Yet the Native Lands Trust Ordinance (NLTO) stood in the way. Seeking to circumvent this legal impediment, in 1931 the metropolitan government appointed the Kenya Land Commission (KLC) to re-examine the terms of the NLTO and define the regions where Europeans had exclusive land rights. Not surprisingly, the commissioners found that the Kikuyu reserves were of adequate size and endorsed the settler community's land claims. While the commissioners acknowledged that some of the Kiambu people who would have to be moved (thereby joining the ranks of the landless) to create more rational boundaries for the white highlands had legal claim to their land, they advised the imperial authorities to pay compensation to the entire Kikuyu community through the office of tribal chiefs instead of to displaced individuals on the grounds that reserve land was collective property. The KLC's report also provided the legal basis for the colonial government to formally delineate the racial boundaries of the highlands through a revised and more flexible NLTO, which empowered district officers to evict Africans trespassing in foreign reserves.Footnote 28

This was easier said than done, for the humanitarian rhetoric of colonial tribalism made it extremely difficult to tinker with the native reserve system. Depicting Africans as tribesmen legitimized British rule, but it also obligated the authorities to act as trustees for supposedly fragile tribal communities. Some district officers took these obligations quite seriously during the heyday of indirect rule. For H. E. Lambert, the tribe was almost an organic institution in its own right and needed protection from the destructive forces of Christianity and western culture. Arguing that the ‘conservation of the soul of an African tribe is as essential as the conservation of its soil’, he rebutted missionary criticism that tribal culture was immoral. ‘Individualism’, which Lambert compared to ‘sheet erosion’, was the greatest threat to the collective ‘tribal soul’. Pushing the analogy further, he viewed a cash economy, taxation, and Christian conversion as detribalizing corrosive forces that ‘[dug] deep and [left] scars on the body politic of the tribe’.Footnote 29

On paper, the KLC's rules appeared to strengthen the inherent tribalism of the native reserve system, but in reality even the commissioners had to acknowledge that the government's rigid ethnic geography was unworkable. Humanitarian interests in Britain agreed with Lambert that the tribal soul in East Africa needed state protection and were therefore unwilling to accept drastic changes to Kenya's tribal geography. The KLC criticized the original NLTO's tribal boundaries as too inflexible to allow for ‘peaceful interpenetration’ between the reserves, but these political realities forced it to acknowledge the rights of ‘occupant tribes’ by making interpenetration contingent upon the consent of host communities.Footnote 30 If this could be achieved, the Kikuyu problem would disappear because their surplus population would assimilate into tribes with less congested reserves.

Yet the KLC failed to spell out how this feat of tribal engineering might be accomplished. While agricultural specialists like Colin Maher agreed that ‘the most beneficial line of development of the Kikuyu tribe is likely to be by the intermingling in marriage of the various peoples and by inter-settlement and the sinking of local differences’, district officers like Lambert, who fancied themselves experts in native custom, were more concerned with protecting tribal culture.Footnote 31 Moreover, they worried that unregulated movement throughout the reserves would create administrative chaos by promoting individualism and accelerating detribalization. Administrators therefore sought to protect the viability of the tribally-based reserve system by establishing that migrants would be adopted into new tribes. Thinking optimistically, they made ‘artificial (ritual) birth’ the ‘necessary condition of any stable inter-penetration’.Footnote 32 Those who successfully completed these rituals to the extent that host communities accepted them were legal interpenetrators, while those who refused and provoked a local backlash were ‘infiltrators’ who remained subject to expulsion under NLTO.

While thousands, if not tens of thousands, of landless people accepted some form of assimilation as the condition for settlement in a new reserve, colonial authorities were deluding themselves. First, many Kikuyu, particularly those from the most radical segments of Kiambu society, defiantly refused adoption. Bowing to tribal authority, particularly in regards to land use, restricted opportunities for commercial agriculture and entailed a loss of property and possible exploitation by foreign chiefs. Equally significant, it was personally demeaning, and in 1936 Senior Chief Koinange told the Fort Hall LNC that Kiambu people rejected the administration's doctrine of ‘blood brotherhood’ because they ‘did not wish to lose their identity this way’.Footnote 33 And the Meru LNC's complaints about ungovernable Kikuyu infiltrators demonstrated that other communities were not always ready to welcome migrants with open arms.

Far from solving the squatter problem, the KLC failed to realize the government would have to relocate roughly 100,000 people to achieve its main goal of making the European sections of the highlands uniformly white. Nevertheless, district officers began the eviction process even though there was nowhere to put the displaced population. Facing settler harassment and prosecution for trespassing if they remained, many Kiambu people set off on their own to find unused land in both nearby and distant reserves. The Masai Extra-Provincial District, which covered over 11,000 square miles of inviting agricultural and grazing land but held less than 50,000 people, was the most obvious destination. When pro-Maasai district officers tried to send the interlopers back to the Kikuyu reserves their counterparts in Kiambu touched off a bitter inter-administrative squabble by refusing to accept the evicted infiltrators on the grounds that the Kikuyu reserves were already filled to capacity.Footnote 34 Additionally, the Kisii reserve in western Kenya's Southern Kavirondo District attracted significant numbers of displaced Kiambu people. And to further complicate matters, district officers also had to take action against illegal settlements of Luhya, Kalenjin, Kamba, and Luo peoples in foreign reserves as the decade drew to a close.Footnote 35

THE DIFFERENT WAYS TO BE KIKUYU IN MERU

The close cultural ties between the Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru peoples made the much closer and less crowded non-Kikuyu reserves comprising the Kikuyu Land Unit logical destinations for ambitious or desperate Kikuyu migrants. Its debatable ethnic spaces provided useful openings for mobile highland peoples to fit themselves into local communities. While the authorities tried to rationalize the reserve system by imagining that tribesmen had exclusive and bounded identities, many migrants saw no contradiction in invoking multiple identities that blurred tribal boundaries. This explains how Kakuthi wa Ithogora and Karigi wa Kubutha could tell the KLC: ‘I am an Embu and also a Kikuyu’, and Kombo wa Munyiri could similarly declare: ‘I belong to the Mbere tribe, i.e. the Mbere section of the Kikuyu tribe.’Footnote 36

In Meru, the first people who explicitly identified themselves as Kikuyu in the colonial sense apparently arrived as mission teachers during the First World War. Nicknamed kamuchunku (‘little whites’) by their would-be flock, they won few converts and relied on Meru chiefs for protection. The first Kikuyu settlers turned up in the 1920s, and most appear to have been accepted as temporary tenants or adopted Embu and Meru. According to Jeffrey Fadiman's informants, in pre-conquest times the latter process would have entailed mingling blood with the adoptees empowering their patrons by assuming the explicit role of social juniors. A small group of newcomers, many of whom were literate Kikuyu who had acquired a substantial amount of cash through the colonial economy, refused to play this role and instead bought land from Meru elders. District officers deemed this illegal under native law, but the new Kikuyu landowners avoided eviction by posing as Meru clients. Meru elders had more success in slowing the sales by refusing to recognize the migrants' land claims. With no security of tenure, land was a much riskier investment.Footnote 37

As in the rest of Kenya, the status of migrants in Embu and Meru became more controversial in the 1930s. While there was a general surplus of land in both reserves that lasted into the 1950s, population growth and the government's promotion of coffee and cotton production during the depression made both communities less willing to allow outsiders to claim prime agricultural land.Footnote 38 The details are hard to come by, but it appears that the mass evictions from Kiambu District spurred increased migration westward, with the displaced Kikuyu settling first in Chuka on the Embu – Meru border and then moving northward to farm on the still open forest margins. Embu District annual reports made little mention of them until 1936 when district officers suddenly noticed that Kikuyu settlement in the reserve had jumped to 5,116 people (an 11 per cent increase).Footnote 39 Fadiman's informants termed these highly entrepreneurial settlers ‘tree eaters’, and their activities led Lambert to worry that the breakdown in tribal sanctions against felling communally owned trees would destroy the forests on Mount Kenya.Footnote 40

Maher's 1938 report on land use in the Meru reserve included pictures of farmers from a new mixed Meru/Kikuyu settlement cutting trees and cultivating steep slopes on the forest border at a place called Punishment Hill. Noting that the region had been an unsafe border zone in pre-conquest times, he perceptively made the connection between its settlement and the events in Kiambu: ‘The people whom I saw had the somewhat sulky and suspicious demeanor of natives who are not certain of their rights to their land, or who expect their rights to be challenged, an expression, in fact, similar to that with which one is familiar amongst natives in the Kiambu Reserve.’Footnote 41

The situation at Punishment Hill was far from unique, and Maher uncovered similar Kikuyu settlements in the Embu reserve. His brief survey of the inhabitants at Njukini found that many were former squatters or plantation workers from Kiambu. The most prosperous farmers employed local people as laborers even though they claimed to be junior members of Embu clans. As part of the agricultural department rather than the field administration, Maher was more concerned with soil conservation than tribal trespassing. He therefore approvingly noted that many of the migrants used ‘progressive’ farming methods. The agricultural officer was particularly impressed with an eighty-acre farm near Embu town where a self-described Kikuyu adoptee grew corn, onions, and wheat and sold an ample bean crop through the Kenya Farmer's Association. The man's family was well fed and lived in a large square house, and ‘as befitted a yeoman of substance, this Kikuyu was polite and well dressed while his feet were shod in gum boots’.Footnote 42

These were just the kind of industrious farmers that could have generated export revenues for the government during the depression. But commercial agriculture was barely feasible in tribally-organized reserves where the imperial regime assumed that land was collective property. While acknowledging that Kikuyu farmers brought innovative agricultural methods to their Embu and Meru neighbors and patrons, Maher worried that ‘Kikuyu ideas’ about private land tenure and intensive agriculture would promote ecologically damaging farming practices. But he also conceded that the displaced Kikuyu would have more incentive to invest in sustainable agriculture if they had secure title to their land.

Maher's main concern was that the most commercially-oriented Kikuyu farmers, who probably represented a relatively small segment of the migrant community, were unfairly appropriating the agricultural patrimony of other tribes by skimming off ‘the cream of the fertility of the soil’ in a quest for quick profits.Footnote 43 Tellingly, he noted that the people who became adopted Meru or Embu rarely behaved so selfishly. This most likely explains why some displaced Kikuyu defiantly insisted on remaining Kikuyu even if it entailed the risk of expulsion and prosecution for tribal trespassing.Footnote 44 Deferring to tribal chiefs and elders would have placed too many restrictions on how they used and profited from the land. Moreover, it appears that a few of the more commercially ambitious migrants actually retained some land in the Kiambu reserve.Footnote 45

There is no way to know precisely how many displaced Kikuyu became respectable Meru or Embu for in most cases the Kenyan authorities only noticed migrants who openly, if not recklessly, refused adoption. This generally occurred when chiefs and elders, who often played a double game by taking money from the new arrivals, complained about trespassing foreigners who rejected tribal authority by cutting down trees, plowing up communal land, and founding local branches of the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) and the Kikuyu Independent Schools Association (KISA). While most highland communities shared the general political goals of the KCA and agreed that Africans should have schools free of mission control, many people in the Embu and Meru reserves worried that these explicitly Kikuyu associations had their own colonizing agendas.

In the late 1930s, officials took action against the most obvious trespassers who openly declared their Kikuyuness. Invoking first the Native Authority Ordinance and then the revised NLTO, they directed accused infiltrators to cease farming and return to the Kikuyu reserves. Mwangi wa Nguriga received such a quit order in 1937 on that grounds that he had violated Meru custom by stealing sheep, using a plow, and refusing adoption into a Meru clan.Footnote 46 Gradually recognizing the scope of Kikuyu movement into the western highland reserves, district officers undertook a systematic survey of the migrants in a vain attempt to determine who was a legitimate interpenetrator and who was an expellable infiltrator.Footnote 47

Two years later, Meru officials ambitiously tried to evict an entire Kikuyu settlement at Chuka. As previously noted, the Chuka were a highland ‘subgroup’ that the colonial regime counted as Meru for administrative purposes. Led by a trader and farmer named Mukua Kagembe (‘Muruakagembe’ to the authorities), this industrious Kikuyu community of some thirty families drew the ire of the Chuka chiefs by clearing forested land, monopolizing springs in public grazing areas, starting KISA schools, and challenging local authority by granting cultivation rights to new Kikuyu immigrants. Sitting in council, Chuka elders charged Mukua with bribing chiefs by plowing their fields and using witchcraft to intimidate potential critics. They also complained that the Kikuyu behaved like ‘European farmers – making money from their shambas and sending it out of the district’.Footnote 48 Mukua and his people expressed surprise at the charges and claimed that they had never given their hosts any problems, while another member of the settlement, Thagana Chege, also asserted his right to settle in Meru because the government had taken his land in Kiambu.Footnote 49

The migrants won temporary protection from Chuka and government reprisals by convincing the Indian councilor Shamsud Deen, who often defended African interests on the Kenya Legislative Council, to take up their case. Specifically invoking the NLTO, Shamsud Deen reminded the imperial administration that it could only expel an infiltrator if the governor could affirm that ‘sufficient land for the accommodation of the African and his family [was] available’. The councilor further pointed out that the NLTO also blocked expulsions until farmers harvested their crops, and he added a religious dimension to the controversy by maintaining that the Chuka Kikuyu could not undergo a ‘pagan’ adoption ceremony because they were Christians. Similarly, Harry Thuku, whose Kikuyu Provincial Association was less radical than the KCA, tried to mediate the dispute by promising that he would answer for Mukua's people if the government allowed them to stay under the authority of a separate Kikuyu chief. Somewhat contradictorily, Thuku's Vice-President Hezekiah Mundia further claimed that Kikuyu and Meru (Chuka) chiefs had met in 1930 and declared that both communities belonged to the same tribe.Footnote 50

These interventions bought the Chuka Kikuyu some time, but in early 1940 the government sent them back to Kiambu on the grounds that they had ignored a legal eviction notice. Meru administrators told Shamsud Deen that the community were subversive followers of a banned Kikuyu religious sect known as the Watu wa Mungu (‘people of God’), and they alleged that Chuka leaders had complained that Mukua's KISA school ‘appeared to be trying to turn young men against Government’. The Meru district commissioner also warned his counterpart in Kiambu to pay no attention to the evictees' claims of destitution because they left Chuka with oxcarts full of food and a great many goats.Footnote 51

While the Chuka case is unusual in that Mukua was particularly successful in attracting influential patrons, variations on this drama took place throughout the Meru reserve in 1939 and the first half of 1940. Further north on the boundary of the Ngala forest in Igembe, Meru elders dealt with a similarly intransigent Kikuyu enclave by taking it upon themselves to harvest the millet crop the ‘tree-eaters’ had secretly planted in an attempt to use the NLTO rules to delay their expulsion. By reconfiguring the Njuri Nceke (a pre-conquest council of elders that mediated social disputes) into a quasi-administrative body, Lambert and his colleagues gave cooperative Meru elders the legal means to check Kikuyu expansion by ruling that land sales to unassimilated outsiders violated Meru custom.Footnote 52

These successful evictions might have created the impression that colonial authorities and their chiefly allies had solved the problem of Kikuyu infiltration. However, the expulsion of defiantly unassimilated people like Mukua Kagembe and his followers took place against the backdrop of the imperial regime's failing efforts to resolve the larger problem of displaced Kikuyu. Legal wrangling over mass expulsions in the Kiambu heartland delayed implementation of the KLC's recommendations, and in 1939 government efforts to evict large numbers of Kikuyu from newly declared European zones ground to halt as the Colonial Office realized that mass deportations were politically indefensible in light of the Nazi atrocities in Europe. Indeed, the KCA cleverly highlighted these similarities in a flood of letters and petitions.Footnote 53 Moreover, it still made little sense to continue the ‘whitening’ of Kiambu District when there was no politically acceptable place to put the surplus people, particularly when tribalistic district officers in the Masai Extra-Provincial District continued to expel Kikuyu infiltrators.

Meeting in 1941, administrators therefore set out to turn the abstract doctrine of tribal interpenetration into a workable set of policy guidelines. Their resolve quickly dissipated as the government became distracted with pressing wartime matters. Consequently, the steady movement of people from Kiambu to the Meru and Embu reserves continued largely unabated.Footnote 54 In March 1940, administrators in Embu District arrested Gitau wa Nyumbu, one of the original Chuka Kikuyu, on his way back to Meru, and Meru community leaders were soon complaining that most of the unassimilated migrants whom they expelled just a few months earlier had returned.Footnote 55 The civil authorities did not pay much attention, but military recruiters in the district uncovered cases of Kikuyu infiltrators, who sought the superior pay and benefits that came with service in combat units, falsely listing themselves as ‘Meru’ to fit within the East Africa Command's mandated tribal recruiting quotas.Footnote 56

By the close of the war, the problem of unassimilated Kikuyu once again became too pronounced to ignore. As in the late 1930s, Meru elders led the call for mass evictions. Adoptable and compliant clients were acceptable, but aggressively entrepreneurial individualists were another matter. The elders' specific complaints against the trespassers included illegal beer brewing, shirking communal (tribal) labor obligations, and refusing to follow the colonial government's new soil conservation rules. Conversely, it also appears that several of the more opportunistic chiefs and LNC members may have secretly taken payments from the Kikuyu migrants.Footnote 57 Therefore, Macharia wa Maina and Gachengiri wa Matu, who received quit notices in late 1944, may have been telling the truth when they claimed that Chief M'Imathio, who was conveniently dead, had given them permission to farm in the reserve. Demonstrating a working knowledge of the NLTO, they also asked for time to harvest their crops.Footnote 58

By this time, news that there was open land in the Meru reserve had begun to attract land-hungry people from all over East Africa. The diverse list of evictees included Raja bin Ramathan (formerly Kirya Katuessia), who was apparently a Chagga (and thus a Tanganyikan) convert to Islam. The details are sketchy, but he appears to have tried and failed to use marriage to a Meru woman, instead of formal adoption into a Meru clan, as his claim to permanent residence in the reserve. Conversely, hundreds of Kiambu refugees similarly found refuge in Tanganyika as forest squatters and farm laborers.Footnote 59

This ongoing and technically illegal cross-reserve and cross-border migration demonstrates that there was very little that the imperial regime could do to limit African mobility. The Tanganyikan authorities actually tolerated some trespassing from Kenya because they faced a labor shortage in the post-Second World War era. But this was not the solution to the pernicious overcrowding problem in the three Kikuyu reserves. In fact, the wartime economic boom made the situation worse by giving the settlers the resources to mechanize their farms, thereby dispensing with the need for Kikuyu labor. Consequently, district councils in the white highlands enacted restrictive regulations that cut the remaining squatter population from 202,944 to 181,803 between 1945 and 1948. To make matters worse, the rising profitability of commercial farming in the Kikuyu reserves as a result of the war gave rich Kikuyu even greater resources to evict tenants and dispossess small landholders.Footnote 60

Recognizing that it was imperative to find a way to fold these surplus people into other tribes, the governor directed field administrators to draft a workable interpenetration policy. The actual assignment fell to H. E. Lambert, the former Meru district commissioner who had now adopted a far more pragmatic view of tribal culture. Taking the KLC report and NLTO as his starting point, Lambert defined infiltration as ‘settlement among a different people but retention by the infiltrator of his original tribality [to coin a word on the analogy of ‘nationality’]’. Conversely, legitimate interpenetration was ‘settlement involving a change of tribe on the part of the interpenetrator, who becomes a member of the tribe of the people among whom he settles, and relinquishes rights that into which he was born’.Footnote 61

Having become less worried about the fate of the ‘tribal soul’, Lambert took his colleagues in the field administration to task for becoming tribal partisans and placing too many obstacles in the way of legal interpenetration. He therefore proposed to make harvesting a single crop without incurring objections from the host community the sole criteria for distinguishing between an illegal infiltrator and an acceptable interpenetrator. Protests by ‘nativist’ district commissioners that this would reward trespassers who managed to remain undetected for a single year forced Lambert to expand the probationary period to two years and three crops of uncontroversial residence in a foreign reserve as the criteria for legal settlement. The government spelled out these new interpenetration rules in a pair of administrative circulars that went to every district in the colony. The circulars further defined an expellable infiltrator as a person who committed an offense against local custom by refusing to take part in an adoption ceremony, forming separate native associations, demanding higher bride prices, bringing in more unauthorized immigrants, or violating local conservation laws.Footnote 62 In Lambert's eyes, tribal identity meant little more than acceptance of chiefly authority and the enforced communalism of the reserve system.

The new guidelines seemed clear on paper, but Lambert's more precise but flexible interpenetration regulations did virtually nothing to make assimilation more appealing. In fact, the rate of illegal migration between the reserves actually increased after the war with members of the Luo, Logoli, Kamba, and Kipsigis communities joining the ranks of the illegal infiltrators. Even more troubling, it appears that a much larger percentage of Kikuyu migrants openly and militantly refused to undergo ritual adoption. This was the case in the Gusii highlands in Nyanza Province where a small enclave of angry displaced Kiambu people flouted the interpenetration rules by demanding KISA schools, Kikuyu representatives on the LNC, and freedom to engage in unrestricted trading and commercial agriculture.Footnote 63

The situation was much the same in the Embu and Meru reserves where the radicalization of a large segment of the Kikuyu community made migrants far less willing to undergo the expense and potential humiliation of adoption. The Embu LNC still considered most Kikuyu migrants reasonable and acceptable, but the councilors complained about a militant faction led by Kiore wa Kinyanjui (reportedly the son of an influential former chief) who committed offenses against Embu custom by running a commercial bus service to Nairobi, vandalizing a salt lick, closing off communal grazing land, and insulting local elders. Other infiltrators demanded Kikuyu representation on the LNC, attacked tribal policemen, and held ‘immoral European type dances’.Footnote 64 Threatened with eviction by district officers under the interpenetration regulations, Kiore and his followers convinced Eliud Mathu, the sole African representative on the Legislative Council, to intervene on their behalf.Footnote 65

To the west, similar dramas played out in the Meru reserve. After more than a decade of struggling with defiant Kikuyu infiltrators, frustrated Meru chiefs and councilors once again pushed the Kenyan authorities to deal conclusively with the problem. The district commissioner began eviction proceedings in May 1947, but problems arose when he tried to send them back to Kiambu. Recognizing that it had become politically explosive to forcibly return people to the crowded and tense Kikuyu reserves, the Central Province provincial commissioner refused to sign eviction notices for the first twenty families and instead pressed the Meru authorities to make the interpenetration process work.Footnote 66

When news of the events in Meru reached the Kiambu LNC, the Kikuyu councilors responded with the inflammatory statements about Kikuyu settlement rights in Meru that provoked testy exchanges with their Meru counterparts. This included the debate over the difference between adopted Meru muchiarwa and murombi strangers that opened this article. In addition to asserting there were significant differences between Meru and Kikuyu, the Meru councilors declared that displaced Kikuyu should seek compensation for lost land in Europe, not in the Meru reserve.Footnote 67 In early 1948, they brought the controversy to a head by presenting the authorities with a list of 1,800 people who refused to be adopted. The Meru district commissioner subsequently gave all non-Meru migrants in the district three months to find sponsors or face eviction.Footnote 68

These events coincided with similar prosecutions of illegal settlers in the Maasai and Gusii reserves. Acting on reports of hut burnings, crop confiscations, and mass arrests, Eliud Mathu tried to mediate between the accused infiltrators and their hosts. He also offered a resolution in the Legislative Council that called on the government to create district interpenetration committees to promote adoption and give migrants more time to adapt to their host communities. Similarly, the Kiambu authorities sought to defuse the tensions by convening a joint session of the Meru, Embu, Kiambu, Nyeri, and Fort Hall LNCs. The chief native commissioner spoke in support of Mathu's resolution in the Legislative Council and affirmed that the government sought ‘maximum fluidity with security’, but he also reminded Mathu that most of the migration problems stemmed from infiltrators who refused to undergo adoption.Footnote 69

It is hardly surprising that the government's overly ambitious interpenetration policies proved unworkable given that they rested on the assumption that all Africans were undifferentiated tribesmen. The notions of tribal collectivity embedded in the native reserve system, the KLC report, and the NLTO made no provision for private land tenure, commercial agriculture, or free enterprise. It was understandable that ambitious or politically-inclined people would view tribal adoption as an attempt to curtail, if not entirely suppress, their individual rights, particularly for those angry over the loss of their land in Kiambu.

Interpenetration was thus an unrealistic solution to an intractable problem, and it was only a matter of time before Kenya's discriminatory ethnic geography led to violence. Forced to scratch out an existence in the overcrowded Kikuyu heartland, unwelcoming foreign reserves, restrictive settler farms, or the Nairobi slums, a generation of desperate young Kikuyu concluded that they had nothing to lose in taking up arms. The British labeled the insurrection that engulfed central Kenya in the first half of the 1950s the Mau Mau Emergency, but the rebels referred to themselves as the Kenya Land Freedom Army. In attacking the Kikuyu chiefs, mission converts, and other prosperous members of their own community in addition to the privileged settler class, they mounted an armed challenge to the native reserve system.

At first, the draconian measures that the Kenya government used to defeat the guerillas appeared to finally resolve the infiltration problem. Empowered to act summarily under the terms of a State of Emergency (martial law), the security forces evicted and incarcerated defiant members of Kikuyu enclaves in Tanganyika, the Gusii highlands, the Masai Extra-Provincial District, and the Meru and Embu reserves.Footnote 70 In 1954, they similarly rounded up most of the Kikuyu in Nairobi during Operation Anvil. Eventually, almost the entire Kikuyu population of Kenya was either in detention or under close supervision in fortified strategic villages.Footnote 71 Yet it is also likely that many former Kikuyu escaped the dragnet by virtue of their adoption into other tribes. Against the backdrop of the violence and civil chaos of the Mau Mau war, accepting junior status under the interpenetration rules finally seemed a reasonable trade-off for protection from the security forces and their Kikuyu Home Guard proxies.

Furthermore, although a great many young people from non-Kikuyu highland communities joined or sympathized with the Mau Mau fighters, imperial repression created strong incentives for Meru and Embu leaders to again affirm that they were not members of a ‘Kikuyu sub-tribe’.Footnote 72 Panicked by their inability to ascertain friend from foe during the revolt, the imperial regime and the settler community viewed all Kikuyu as tainted. In 1956, the district commission for Nairobi deemed only 1 per cent of the Kikuyu population ‘reliable’.Footnote 73

By extension this made all residents of the highlands suspect by virtue of their Kikuyu-like cultural institutions, which explains why Meru and Embu politicians went to great lengths to distance their communities from their Kikuyu cousins.Footnote 74 Paradoxically, it took the Emergency to give the tribal fiction of the native reserve system a measure of reality by making the reserves more coherent tribal units. In 1956, the authorities split off the Meru reserve from the greater Kikuyu Land Unit, and the mass incarceration of Kikuyu suspects without trial gave the region a temporary and artificial appearance of homogeneity.Footnote 75 Equally ironic, the government's attempt to create a sympathetic class of yeoman farmers through the land consolidation schemes laid out in the Swynnerton plan went a long way to legitimizing the individualistic conception of Kikuyuness that made earlier generations of infiltrators so vulnerable and inassimilable.Footnote 76

CONCLUSION

These realities of ethnic interpenetration and infiltration in the Meru and Embu reserves during the imperial era offer a fine-grained perspective on the origins and nature of tribal identity in the twentieth century. There was no single coherent Meru community before the British conquest of the highlands, but there were a series of groups that shared enough linguistic and cultural institutions to allow imperial administrators to group them together as ‘Meru’. Yet these shared markers of identity were also sufficiently flexible to absorb Kikuyu migrants and other outsiders. Similarly, one of the main reasons that the Meru council of elders (the Njuri Ncheke) was so effective in limiting Kikuyu attempts to claim land on an individual basis was that it had strong precolonial precedents. But this reworked body was a product of the colonial era in that Lambert and the other nativist district commissioners created new initiation rituals that were compatible with Christianity and gave the council new and unprecedented authority to enforce decisions with fines and other coercive measures.Footnote 77 Lambert's interpenetration rules worked the same way in invoking pre-conquest systems of adoption and ‘blood brotherhood’ as precedents for creating new social and political categories.

The diverse meanings of being a Kikuyu in Meru fit neither strict primordial nor constructivist conceptions of African identity formation. As with all people, Britain's Kenyan subjects had a variety of options in deciding how to identify themselves and could assume different political and social roles by invoking one or more of them at a time and in specific circumstances. As Floya Anthias suggests in her theoretical discussion of collective identity and translocational positionality, the question is not ‘who are you?’ but ‘what and how have you’ become who you are?Footnote 78 The native reserve system's linkage of tribal identity with land rights created powerful incentives for landless or marginal people to accept adoption into a new tribe. Some probably took this naturalization process as seriously as Lambert intended. For others, like the militant Kikuyu enclaves that insisted on defiantly remaining Kikuyu, foreign tribal identities were an unacceptable infringement on their commercial aspirations and rights as individuals. The colonial attempt to link identity with tribal space through the native reserves simply set the scene for ethnic identity formation. By framing political and social discourse in tribal terms, colonial authorities forced Africans to speak in tribal terms. They could not, however, dictate what these terms meant, nor could they dictate the nature or direction of the conversation. And we should not underestimate the capacity of defiant individuals to act out in anger when confronted with authoritarian limits on their personal freedom. Ultimately, ordinary people had more influence than H. E. Lambert and other nativist administrators in deciding what it meant to be Kikuyu, Embu, or Meru.